Abstract

Setting: Tuberculosis (TB) morbidity in penitentiary sectors is one of the major barriers to ending TB in the World Health Organization (WHO) European Region. Objectives and design: a comparative analysis of TB notification rates during 2014–2018 and of treatment outcomes in the civilian and penitentiary sectors in the WHO European Region, with an assessment of risks of developing TB among people experience incarceration. Results: in the WHO European Region, incident TB rates in inmates were 4–24 times higher than in the civilian population. In 12 eastern Europe and central Asia (EECA) countries, inmates compared to civilians had higher relative risks of developing TB (RR = 25) than in the rest of the region (RR = 11), with the highest rates reported in inmates in Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Republic of Moldova, Russian Federation, and Ukraine. The average annual change in TB notification rates between 2014 and 2018 was −7.0% in the civilian sector and −10.9% in the penitentiary sector. A total of 15 countries achieved treatment success rates of over 85% for new penitentiary sector TB patients, the target for the WHO European Region. In 10 countries, there were no significant differences in treatment outcomes between civilian and penitentiary sectors. Conclusion: 42 out of 53 (79%) WHO European Region countries reported TB data for the selected time periods. Most countries in the region achieved a substantial decline in TB burden in prisons, which indicates the effectiveness of recent interventions in correctional institutions. Nevertheless, people who experience incarceration remain an at-risk population for acquiring infection, developing active disease and unfavourable treatment outcomes. Therefore, TB prevention and care practices in inmates need to be improved.

Keywords: tuberculosis, prisons, notification, outcomes, WHO European Region

1. Introduction

In 2019 in the world, 10 million people developed TB disease, and 1.4 million died from TB. Although WHO European Region carries only 3% of the global burden of tuberculosis (TB), it has one of the highest proportions of multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB). In 2019, an estimated 246,000 incident TB cases occurred in countries of the WHO European Region, equivalent to an average incidence of 26 cases per 100,000 population [1].

Over the last century, global control efforts have reduced the worldwide burden of tuberculosis (TB) [1]. Nevertheless, TB morbidity in the penitentiary sector (The term “penitentiary sector” includes jails, remand/detention/pre-trial centres and prisons) remain a significant barrier to ending TB in the World Health Organization (WHO) European Region by 2030 [1,2]. Worldwide, more than 10 million people are inmates, with around half located in Brazil, China, the Russian Federation and the United States of America [3,4]. According to the United Nations’ estimates of national population levels, the known prison population of the world increased by 3.7% between 2015 and 2018. In the WHO European Region, the most substantial increases in prison populations were observed in Turkey (an increase of 31%), Belarus (19%) and Italy (14%). However, prison populations decreased in Romania (a decrease of 22%), Ukraine (19%) and the Russian Federation (10%) during the same period [5].

TB prevention and care services in prisons are described as often being inadequate and poorly integrated with civilian services, and prison inmates consistently have higher risks of developing active TB and dying from TB than the general population, owing to poor conditions in prisons, such as overcrowding, inadequate ventilation, malnutrition, poor hygiene and poor health care [6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. Additionally, inmates often come from communities, which are at an increased risk of TB or HIV infections [2,8,13].

The objectives of this study were to describe the diversity of notification of incident TB cases (notification rate of incident TB cases—number of new and relapse tuberculosis cases registered and reported per 100,000 population [1]) and their trends in the civilian and penitentiary sectors between 2014 and 2018; the treatment outcomes in the penitentiary versus the civilian sectors, and to estimate the relative risks of developing active TB for prison inmates (inmates—includes people experience incarceration, detainees and convicts) in comparison to civilian population in the WHO European Region.

2. Methods and Materials

This is a retrospective descriptive study analysing magnitude and time-series trends in the notification of new and relapse TB cases and TB treatment outcomes in the civilian and penitentiary sectors in the WHO European Region, based on data reported by WHO European Region Member States to The WHO global TB data collection system [14] between 2012 and 2018, inclusively.

2.1. Setting

The WHO European Region consists of 53 Member States covering a vast geographical region from the Atlantic to the Pacific oceans and from the Mediterranean to the Baltic Sea [15]. Our study focused on comparative analyses of TB indicators in eastern Europe and central Asia (EECA) countries as well as of those from the rest of the region. The EECA region is made up of 12 of the 15 countries, which were formerly part of the Soviet Union, excluding the Baltics, and which are located in the east of the WHO European Region.

2.2. Study Population and Design

Data were collected for new and relapse TB cases and their outcomes from the civilian and penitentiary sectors reported in WHO European Region countries. Three selection criteria were applied: (1) countries that provided at least one report on new and relapse TB cases in both the civilian and penitentiary sectors between 2014 and 2018; (2) countries that provided at least two data points on new and relapse TB cases in both civilian and penitentiary sectors between 2014 and 2019 for enabling analysis of the trend; (3) countries that reported outcomes for TB cases on first-line drug (FLD) treatment schemes in both the civilian and penitentiary sectors for at least one cohort between 2012 and 2016.

2.3. Data Variables and Sources

Data were obtained from 3 sources: (1) The WHO global TB data collection system [14] has an extended set of indicators for TB in European Region prisons, and data were extracted on: prison populations, the numbers of new and relapse TB cases in the civilian and penitentiary sectors for 2014 to 2018, and treatment outcomes for patients on FLD treatment schemes in the civilian and penitentiary sectors for 2012 to 2016; (2) total population estimates were extracted from World Population Prospects [16]; and (3) prison population estimates were taken from the World Prison Brief [17] for countries whose prison population data were missing from The WHO global TB data collection system.

2.4. Analysis and Statistics

For each country, we calculated annual notification rates per 100,000 population of new and relapse tuberculosis cases in civilian and penitentiary sectors separately. The Average Annual Percent Change (AAPC) was calculated by fitting a least-squares regression line to the natural logarithm of the rates, using the calendar year as a regressor variable.

As a measure of the effect of exposure to a prison setting on the risk of development of TB we computed the Relative Risk of TB in prison in reference to the civilian population and the corresponding confidence interval. Results were considered significant if the confidence interval did not include 1. The statistical analysis was performed using the online calculator VassarStats [18]. TB patients who were successfully treated or completed TB treatment were considered to have a favourable outcome; those who failed to complete treatment, were lost to follow-up or who died during the TB treatment were considered to have an unfavourable outcome, as per WHO standard definitions [19]. TB cases with no reported treatment outcomes were excluded from the analysis. We analysed the notification rate of incident TB cases and TB treatment outcomes (unfavourable versus favourable) for the civilian and penitentiary sectors.

3. Results

3.1. Notification Rate of Incident TB Cases and Relative Risks of Developing TB Disease in the Penitentiary Sector Compared with the Civilian Sector

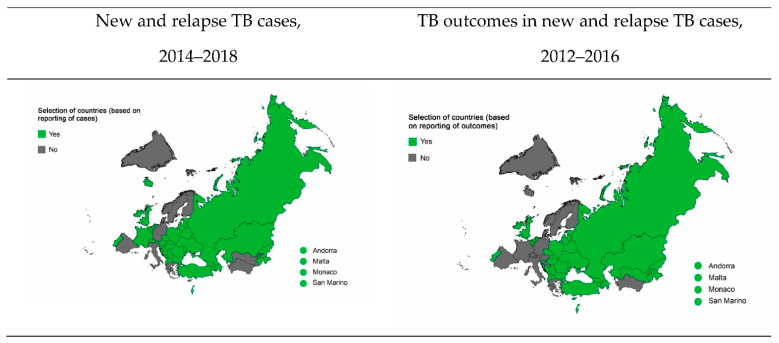

Out of the 53 countries of the WHO European Region, 42, including 10 from the EECA region, reported the number of new and relapse TB cases in the civilian and penitentiary sectors at least once in the five-year period between 2014 and 2018. During this time, 11 (21%) countries did not provide any reports on TB in prisons (Table 1 and Figure 1).

Table 1.

Completeness of TB reporting for civilian and penitentiary sectors via The WHO global TB data collection system, WHO European Region countries.

| a. Number of New and Relapse TB Cases, 2014–2018 | |||||||||||

| Country | Civilian Sector | Penitentiary Sector | Status | ||||||||

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | ||

| Albania | 404 | 415 | 412 | 495 | 437 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 8 | 3 | Y |

| Andorra | 6 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y |

| Armenia a | 1303 | 1151 | 1018 | 825 | 720 | 26 | 20 | 9 | 16 | 14 | Y |

| Austria | − | − | 619 | − | − | − | − | 0 | − | − | Y |

| Azerbaijan a | 5490 | 5228 | 4905 | 4975 | 4822 | 298 | 228 | 254 | 256 | 216 | Y |

| Belarus a | − | 3658 | 3090 | 2684 | 2253 | − | 107 | 121 | 97 | 106 | Y |

| Belgium | 851 | 916 | 967 | 896 | − | 35 | 12 | 19 | 20 | − | Y |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 1194 | 1091 | − | − | 666 | 2 | 4 | − | − | 0 | Y |

| Bulgaria | 1774 | 1599 | 1503 | 1392 | 1307 | 51 | 20 | 22 | 16 | 16 | Y |

| Croatia | 491 | − | 449 | − | − | 5 | − | 0 | − | − | Y |

| Cyprus | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | N |

| Czechia | 458 | 489 | 497 | 474 | − | 16 | 19 | 14 | 25 | 22 | Y |

| Denmark | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | N |

| Estonia | 230 | 197 | 180 | 168 | 140 | 6 | 9 | 8 | 3 | 5 | Y |

| Finland | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | N |

| France | − | 4433 | 4610 | 4774 | − | − | 61 | 65 | 65 | − | Y |

| Georgia a | 3099 | 3070 | 2926 | 2539 | 2272 | 101 | 82 | 57 | 58 | 43 | Y |

| Germany | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | N |

| Greece | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | N |

| Greenland | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | N |

| Hungary | 789 | − | 728 | − | − | 10 | − | 9 | − | − | Y |

| Iceland | 8 | − | − | − | − | 0 | − | − | − | − | Y |

| Ireland | 292 | 295 | 293 | 301 | 294 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y |

| Israel | 356 | 278 | − | − | − | 5 | 2 | − | − | − | Y |

| Italy | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | N |

| Kazakhstan a | 14,282 | 13,423 | 11,838 | 12,063 | 12,479 | 962 | 583 | 484 | 386 | 353 | Y |

| Kyrgyzstan a | 6233 | 6779 | 6810 | 6488 | 6198 | 157 | 248 | 216 | 199 | 140 | Y |

| Latvia | 685 | 664 | 609 | 522 | − | 53 | 33 | 32 | 21 | − | Y |

| Lithuania | 1424 | 1354 | 1312 | 1214 | − | 57 | 41 | 35 | 54 | − | Y |

| Luxembourg | 37 | 30 | 29 | 32 | 42 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y |

| Malta | 45 | 32 | 50 | 42 | − | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | − | Y |

| Monaco | 0 | 0 | − | − | − | 0 | 0 | − | − | − | Y |

| Montenegro | 112 | 79 | − | − | − | 1 | 1 | − | − | − | Y |

| Netherlands | 798 | 845 | 863 | 757 | 784 | 16 | 5 | 14 | 19 | 7 | Y |

| North Macedonia | 280 | 278 | 260 | 206 | 214 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 10 | 3 | Y |

| Norway | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | N |

| Poland | 6387 | 6065 | 5927 | 5365 | 5025 | 152 | 172 | 216 | 170 | 171 | Y |

| Portugal | 2198 | 2053 | 1833 | 1728 | 1812 | 53 | 61 | 39 | 32 | 44 | Y |

| Republic of Moldova a | 3937 | 3484 | 3398 | 3259 | 2933 | 121 | 124 | 173 | 99 | 89 | Y |

| Romania | 14,652 | 14,064 | 12,633 | 12,205 | 11,472 | 209 | 161 | 157 | 105 | 114 | Y |

| Russian Federation a | 91,025 | 89,218 | 82,797 | 76,344 | 70,967 | 11,315 | 10,372 | 9610 | 8166 | 7291 | Y |

| San Marino | − | − | 0 | 0 | 0 | − | − | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y |

| Serbia | 969 | 864 | 744 | 730 | 637 | 15 | 15 | 11 | 8 | 4 | Y |

| Slovakia | 299 | 291 | 264 | 210 | − | 21 | 17 | 17 | 18 | − | Y |

| Slovenia | 142 | 129 | 118 | − | − | 0 | 0 | 0 | − | − | Y |

| Spain | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | N |

| Sweden | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | N |

| Switzerland | − | 527 | − | − | − | − | − | 4 | − | − | Y |

| Tajikistan a | 5677 | 5804 | 5866 | 5794 | 5605 | 130 | 90 | 99 | 101 | 121 | Y |

| Turkey | 12,966 | 12,413 | 12,035 | 11,696 | 11,421 | 142 | 137 | 151 | 125 | 155 | Y |

| Turkmenistan a | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | N |

| Ukraine a | 30,245 | 28,974 | 28,133 | 26,485 | 25,745 | 1456 | 1177 | 919 | 744 | 767 | Y |

| United Kingdom | 6581 | 5821 | 5766 | 5226 | − | 43 | 33 | 27 | 22 | − | Y |

| Uzbekistan a | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | N |

| b. Number of TB Patients Who Started on One of the FLD Treatment Schemes, 2012–2016 | |||||||||||

| Country | Civilian Sector | Penitentiary Sector | Status | ||||||||

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | ||

| Albania | 405 | 470 | 402 | 409 | 406 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 3 | Y |

| Andorra | 9 | 0 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y |

| Armenia a | 1341 | 1228 | 1202 | 896 | 861 | 9 | 23 | 26 | 14 | 8 | Y |

| Austria | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | N |

| Azerbaijan a | 4341 | 3973 | 1389 | 1292 | 1270 | 275 | 321 | 234 | 183 | 194 | Y |

| Belarus a | 3298 | 2935 | 2648 | 2458 | 2076 | 127 | 99 | 58 | 67 | 47 | Y |

| Belgium | 855 | 856 | 833 | 895 | 955 | 30 | 22 | 34 | 10 | 18 | Y |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | − | 1257 | 1194 | 1091 | 907 | − | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | Y |

| Bulgaria | 2136 | 1878 | 1744 | 1578 | 1488 | 44 | 25 | 45 | 20 | 22 | Y |

| Croatia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | N |

| Cyprus | − | − | − | − | 55 | − | − | − | − | 1 | Y |

| Czechia | 536 | 452 | 453 | 481 | 492 | 20 | 16 | 14 | 18 | 13 | Y |

| Denmark | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | N |

| Estonia | 218 | 210 | 189 | 163 | 158 | 4 | 16 | 5 | 9 | 8 | Y |

| Finland | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | N |

| France | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | N |

| Georgia a | 3245 | 2994 | 2781 | 2780 | 2666 | 393 | 104 | 81 | 61 | 49 | Y |

| Germany | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | N |

| Greece | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | N |

| Greenland | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | N |

| Hungary | 1161 | 1016 | − | 847 | − | 11 | 14 | − | 4 | − | Y |

| Iceland | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | N |

| Ireland | 336 | 345 | 283 | 265 | 286 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | Y |

| Israel | 506 | 295 | 317 | 261 | − | 3 | 10 | 5 | 2 | − | Y |

| Italy | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | N |

| Kazakhstan a | 15,514 | 13,400 | 11,791 | 13,372 | − | 761 | 1056 | 682 | 634 | − | Y |

| Kyrgyzstan a | − | 5533 | 5610 | 5969 | 5910 | − | 125 | 121 | 170 | 162 | Y |

| Latvia | 823 | 764 | 631 | 609 | 560 | 49 | 40 | 44 | 33 | 32 | Y |

| Lithuania | 1428 | 1347 | 1238 | 1183 | 1126 | 31 | 45 | 44 | 36 | 26 | Y |

| Luxembourg | − | − | 37 | − | − | − | 1 | − | − | Y | |

| Malta | 41 | 49 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y |

| Monaco | − | 3 | 0 | − | − | − | 0 | 0 | − | − | Y |

| Montenegro | 107 | 119 | 112 | 79 | − | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | − | Y |

| Netherlands | 906 | 796 | 782 | 833 | 850 | 18 | 20 | 14 | 4 | 14 | Y |

| North Macedonia | 345 | 309 | 277 | 278 | 260 | 1 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 3 | Y |

| Norway | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | N |

| Poland | 7057 | 6791 | 6369 | 6054 | 5904 | 204 | 220 | 131 | 142 | 195 | Y |

| Portugal | 2493 | 2336 | 2198 | 2053 | 1833 | 46 | − | − | 61 | 39 | Y |

| Republic of Moldova a | 4073 | 3747 | 3358 | 2903 | 2909 | 130 | 142 | 101 | 89 | 139 | Y |

| Romania | 16,313 | 15,048 | 14,321 | 13,747 | 12,304 | 112 | 140 | 204 | 161 | 155 | Y |

| Russian Federation a | 80,594 | 71,674 | 67,146 | 71,317 | 64,591 | 9072 | 11,627 | 9990 | 9107 | 8546 | Y |

| San Marino | − | − | − | 0 | − | − | − | − | 0 | − | Y |

| Serbia | 1171 | 1163 | 1032 | 868 | 722 | 26 | 21 | 13 | 14 | 11 | Y |

| Slovakia | 323 | 368 | 298 | 288 | 262 | 20 | 27 | 20 | 17 | 17 | Y |

| Slovenia | 138 | 139 | 142 | 129 | − | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | − | Y |

| Spain | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | N |

| Sweden | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | N |

| Switzerland | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | N |

| Tajikistan a | 5664 | 5151 | 5047 | 5222 | 5254 | 147 | 112 | 102 | 76 | 70 | Y |

| Turkey | 13,409 | 13,047 | 12,791 | 12,219 | 11,851 | 126 | 123 | 142 | 143 | 166 | Y |

| Turkmenistan a | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | N |

| Ukraine a | 29,346 | 28,016 | 21,270 | 23,015 | 21,618 | 1582 | 1710 | 1024 | 877 | 997 | Y |

| United Kingdom | 8106 | 7260 | 6469 | 5773 | 5649 | 35 | 33 | 43 | 29 | 26 | Y |

| Uzbekistan a | 13,783 | − | − | − | − | 349 | − | − | − | − | Y |

−: not reported; EECA: east European central Asia; N: excluded from the analysis; TB: tuberculosis; Y: included in the analysis; WHO: World Health Organization a EECA country.

Figure 1.

Countries/states selected for case analysis based on the availability of TB reporting forms. TB: tuberculosis; WHO: World Health Organization.

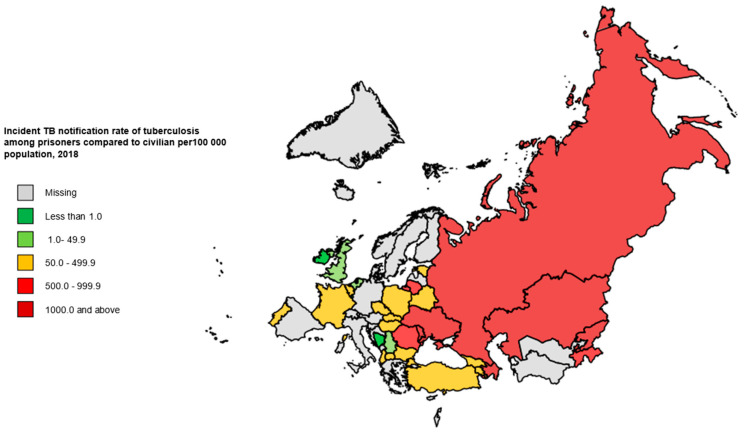

Table 2 shows the notification rate of incident TB cases (The notification rate of incident TB cases is the number of new and relapse tuberculosis cases reported per 100,000 population [1]) and percentage annual changes in notification rate of incident TB cases in the civilian and penitentiary sectors during 2014–2018 for the countries included in this study. In the penitentiary sectors of seven countries, all of which are in the EECA region, incident TB rates of more than 1000 per 100,000 population were reported: Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, the Republic of Moldova, the Russian Federation, Tajikistan and Ukraine (Table 2 and Figure 2).

Table 2.

Notification rate of incident TB cases and year-to-year percentage changes in TB notification rates, WHO European Region, 2014–2018.

| a. Civilian Sector | ||||||||||

| Country | Notification Rate of Incident TB Cases per 100,000 Population | Annual Change in Notification Rate of Incident TB Cases (%) | ||||||||

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2014–2015 | 2015–2016 | 2016–2017 | 2017–2018 | Average | |

| Albania | 13.9 | 14.2 | 14.1 | 16.9 | 15.2 | 2.6 | −0.8 | 18.2 | −10.8 | 2.3 |

| Andorra | 7.6 | 5.1 | 5.2 | 1.3 | 2.6 | −39.0 | 0.9 | −138.2 | 69.3 | −23.5 |

| Armenia a | 44.9 | 39.5 | 34.9 | 28.2 | 24.4 | −12.8 | −12.5 | −21.2 | −14.4 | −14.1 |

| Azerbaijan a | 57.9 | 54.5 | 50.5 | 50.7 | 48.6 | −6.1 | −7.5 | 0.4 | −4.4 | −4.3 |

| Belarus a | 38.7 | 32.7 | 28.5 | 23.9 | −16.8 | −14.0 | −17.3 | −14.8 | ||

| Belgium | 7.6 | 8.1 | 8.5 | 7.8 | 7.8 | 6.7 | 4.8 | −8.3 | −0.5 | 0.7 |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 33.5 | 30.8 | 20.1 | −8.4 | −12.0 | |||||

| Bulgaria | 24.6 | 22.3 | 21.1 | 19.7 | 18.1 | −9.8 | −5.5 | −7.0 | −8.4 | −7.4 |

| Croatia | 11.5 | 10.7 | −3.9 | |||||||

| Czech Republic | 4.3 | 4.6 | 4.7 | 4.5 | 3.9 | 6.5 | 1.6 | −4.8 | −14.2 | −2.7 |

| Estonia | 17.5 | 15.0 | 13.7 | 12.9 | 10.6 | −15.3 | −8.8 | −6.7 | −19.3 | −11.8 |

| France | 6.9 | 7.1 | 7.4 | 7.3 | 3.5 | 3.1 | −1.3 | 1.8 | ||

| Georgia a | 77.8 | 77.9 | 74.7 | 65.1 | 56.9 | 0.1 | −4.1 | −13.8 | −13.4 | −7.5 |

| Hungary | 8.1 | 7.5 | 6.1 | −6.9 | ||||||

| Ireland | 6.2 | 6.3 | 6.2 | 6.3 | 6.1 | 0.7 | −1.3 | 1.8 | −3.6 | −0.6 |

| Israel | 4.5 | 3.5 | −26.3 | −26.3 | ||||||

| Kazakhstan a | 81.9 | 75.8 | 66.0 | 66.4 | 68.2 | −7.7 | −13.9 | 0.6 | 2.8 | −4.5 |

| Kyrgyzstan a | 108.1 | 115.7 | 114.5 | 107.5 | 120.8 | 6.8 | −1.1 | −6.3 | 11.7 | 2.8 |

| Latvia | 34.1 | 33.4 | 31.0 | 26.8 | −2.0 | −7.5 | −14.4 | −7.7 | ||

| Lithuania | 48.2 | 46.3 | 45.2 | 42.1 | 36.4 | −4.1 | −2.4 | −7.2 | −14.6 | −6.8 |

| Luxembourg | 6.7 | 5.3 | 5.0 | 5.5 | 7.0 | −22.8 | −5.0 | 8.5 | 23.7 | 1.1 |

| Malta | 10.6 | 7.5 | 11.7 | 9.8 | 12.5 | −34.6 | 44.2 | −17.8 | 25.0 | 4.3 |

| Monaco | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||||||

| Montenegro | 17.9 | 12.6 | −35.0 | −35.0 | ||||||

| Netherlands | 4.7 | 5.0 | 5.1 | 4.5 | 4.6 | 5.4 | 1.8 | −13.4 | 3.4 | −0.7 |

| North Macedonia | 13.5 | 13.4 | 12.5 | 9.9 | 10.3 | −0.8 | −6.8 | −23.4 | 3.8 | −6.6 |

| Poland | 16.7 | 15.9 | 15.5 | 14.1 | 13.3 | −5.1 | −2.2 | −9.8 | −5.9 | −5.6 |

| Portugal | 20.5 | 19.7 | 17.7 | 16.8 | 17.7 | −3.8 | −10.8 | −5.7 | 5.5 | −3.6 |

| Republic of Moldova a | 96.9 | 85.8 | 83.9 | 80.6 | 72.5 | −12.1 | −2.3 | −4.0 | −10.6 | −7.0 |

| Romania | 73.5 | 70.9 | 64.0 | 62.1 | 58.9 | −3.6 | −10.2 | −3.0 | −5.3 | −5.4 |

| Russian Federation a | 63.6 | 62.3 | 57.8 | 53.2 | 48.9 | −2.1 | −7.5 | −8.2 | −8.5 | −6.4 |

| San Marino | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||||

| Serbia | 10.9 | 9.8 | 8.4 | 8.3 | 7.2 | −11.1 | −14.6 | −1.6 | −13.8 | −9.7 |

| Slovakia | 5.5 | 5.4 | 4.9 | 3.9 | 4.7 | −2.8 | −9.8 | −22.9 | 20.1 | −3.8 |

| Slovenia | 6.9 | 6.2 | 5.7 | −9.8 | −9.1 | −9.0 | ||||

| Tajikistan a | 68.0 | 68.0 | 67.2 | 65.0 | 61.7 | 0.0 | −1.1 | −3.3 | −5.3 | −2.4 |

| Turkey | 16.9 | 15.9 | 15.2 | 14.5 | 13.9 | −5.9 | −4.6 | −4.4 | −4.3 | −4.7 |

| Ukraine a | 67.5 | 65.0 | 63.4 | 60.0 | 58.3 | −3.8 | −2.4 | −5.6 | −2.9 | −3.6 |

| United Kingdom | 10.1 | 8.9 | 8.8 | 7.9 | 7.1 | −12.9 | −1.5 | −10.4 | −11.0 | −8.6 |

| EECA | 67.2 | 64.3 | 60.2 | 56.4 | 53.1 | −4.4 | −6.6 | −6.6 | −6.0 | −5.7 |

| Non-EECA | 17.2 | 14.9 | 14.0 | 13.6 | 12.7 | −14.6 | −5.8 | −3.4 | −6.8 | −7.4 |

| All Countries | 38.8 | 34.9 | 32.6 | 31.2 | 29.1 | −10.6 | −6.7 | −4.4 | −7.2 | −7.0 |

| b. Penitentiary Sector | ||||||||||

| Country | Notification Rate of Incident TB Cases per 100,000 Population | Annual Change in Notification Rate of Incident TB Cases (%) | ||||||||

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2014–2015 | 2015–2016 | 2016–2017 | 2017–2018 | Average | |

| Albania | 76.9 | 0.0 | 49.2 | 147.7 | 56.8 | −100.0 | 109.9 | −95.5 | −7.3 | |

| Andorra | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Armenia a | 662.8 | 509.8 | 184.7 | 328.3 | 395.9 | −26.2 | −101.5 | 57.5 | 18.7 | −12.1 |

| Azerbaijan a | 1580.0 | 1115.8 | 1217.6 | 1266.5 | 1117.9 | −34.8 | 8.7 | 3.9 | −12.5 | −8.3 |

| Belarus a | 359.3 | 344.1 | 275.8 | 301.4 | −4.4 | −22.1 | 8.9 | −5.7 | ||

| Belgium | 297.4 | 109.3 | 161.4 | 188.3 | 160.1 | −100.1 | 39.0 | 15.4 | −16.3 | −14.3 |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 65.7 | 119.2 | 0.0 | 59.5 | −100.0 | |||||

| Bulgaria | 597.9 | 261.8 | 277.7 | 220.3 | 229.3 | −82.6 | 5.9 | −23.2 | 4.0 | −21.3 |

| Croatia | 114.9 | 0.0 | −100.0 | |||||||

| Czech Republic | 85.8 | 91.1 | 62.3 | 112.8 | 102.0 | 6.0 | −38.0 | 59.4 | −10.1 | 4.4 |

| Estonia | 181.8 | 296.6 | 281.6 | 107.1 | 200.0 | 49.0 | −5.2 | −96.6 | 62.4 | 2.4 |

| France | 91.3 | 97.8 | 95.2 | 96.7 | 6.9 | −2.7 | 1.6 | 1.9 | ||

| Georgia a | 973.8 | 844.0 | 610.7 | 625.0 | 473.4 | −14.3 | −32.4 | 2.3 | −27.8 | −16.5 |

| Hungary | 47.6 | 47.4 | 92.0 | 17.9 | ||||||

| Ireland | 37.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −100.0 | |

| Israel | 24.1 | 9.9 | −89.0 | −89.0 | ||||||

| Kazakhstan a | 1857.4 | 1164.9 | 967.1 | 1102.9 | 1002.3 | −46.7 | −18.6 | 13.1 | −9.6 | −14.3 |

| Kyrgyzstan a | 2081.1 | 3038.5 | 2602.4 | 2238.7 | 1623.4 | 37.8 | −15.5 | −15.1 | −32.1 | −6.0 |

| Latvia | 1031.3 | 748.5 | 754.2 | 557.8 | −32.1 | 0.8 | −30.2 | −18.5 | ||

| Lithuania | 660.0 | 557.4 | 513.6 | 818.3 | 718.8 | −16.9 | −8.2 | 46.6 | −13.0 | 2.2 |

| Luxembourg | 152.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −100.0 | |

| Malta | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Monaco | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||||||

| Montenegro | 64.2 | 74.6 | 15.0 | 15.0 | ||||||

| Netherlands | 37.2 | 11.6 | 37.7 | 68.0 | 24.0 | −116.3 | 117.5 | 59.0 | −104.0 | −10.4 |

| Poland | 192.4 | 218.2 | 302.3 | 230.3 | 230.8 | 12.6 | 32.6 | −27.2 | 0.2 | 4.7 |

| Portugal | 378.5 | 421.9 | 261.3 | 237.7 | 348.9 | 10.9 | −47.9 | −9.5 | 38.4 | −2.0 |

| Republic of Moldova a | 1765.7 | 1809.4 | 2228.8 | 1275.4 | 1165.7 | 2.4 | 20.8 | −55.8 | −9.0 | −9.9 |

| Romania | 699.0 | 567.8 | 579.0 | 466.0 | 553.3 | −20.8 | 2.0 | −21.7 | 17.2 | −5.7 |

| Russian Federation a | 1683.6 | 1543.3 | 1503.8 | 1335.9 | 1259.7 | −8.7 | −2.6 | −11.8 | −5.9 | −7.0 |

| San Marino | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||||

| Serbia | 145.8 | 145.8 | 103.1 | 75.0 | 37.0 | 0.0 | −34.7 | −31.8 | −70.6 | −29.0 |

| Slovakia | 284.3 | 209.7 | 211.9 | 219.2 | 204.0 | −30.4 | 1.0 | 3.4 | −7.2 | −8.0 |

| Slovenia | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||||

| Tajikistan a | 1300.0 | 900.0 | 990.0 | 748.1 | 806.7 | −36.8 | 9.5 | −28.0 | 7.5 | −11.2 |

| North Macedonia | 153.8 | 148.1 | 111.1 | 323.9 | 100.0 | −3.8 | −28.8 | 107.0 | −117.5 | −10.2 |

| Turkey | 89.4 | 76.9 | 75.3 | 53.8 | 55.3 | −15.0 | −2.2 | −33.5 | 2.6 | −11.3 |

| Ukraine a | 1982.8 | 1875.7 | 1405.2 | 1222.2 | 1424.2 | −5.6 | −28.9 | −14.0 | 15.3 | −7.9 |

| United Kingdom | 43.2 | 35.1 | 29.0 | 23.8 | 28.3 | −20.7 | −19.1 | −19.8 | 17.4 | −10.0 |

| EECA | 1703.9 | 1491.4 | 1403.6 | 1254.5 | 1192.8 | −13.3 | −6.1 | −11.2 | −5.0 | −8.5 |

| Non-EECA | 158.2 | 128.1 | 132.5 | 116.3 | 107.4 | −21.1 | 3.4 | −13.1 | −7.9 | −9.2 |

| All Countries | 1084.6 | 920.7 | 861.3 | 759.9 | 682.2 | −16.4 | −6.7 | −12.5 | −10.8 | −10.9 |

EECA: east European central Asia; WHO: World Health Organization. Note: TB notification rate: number of new and relapse tuberculosis cases registered and reported per 100,000 population. a EECA country; in bold are the countries groups averages

Figure 2.

Notification rate of incident TB cases in the penitentiary sector per 100,000 population, WHO European Region, 2018. TB: tuberculosis; WHO: World Health Organization.

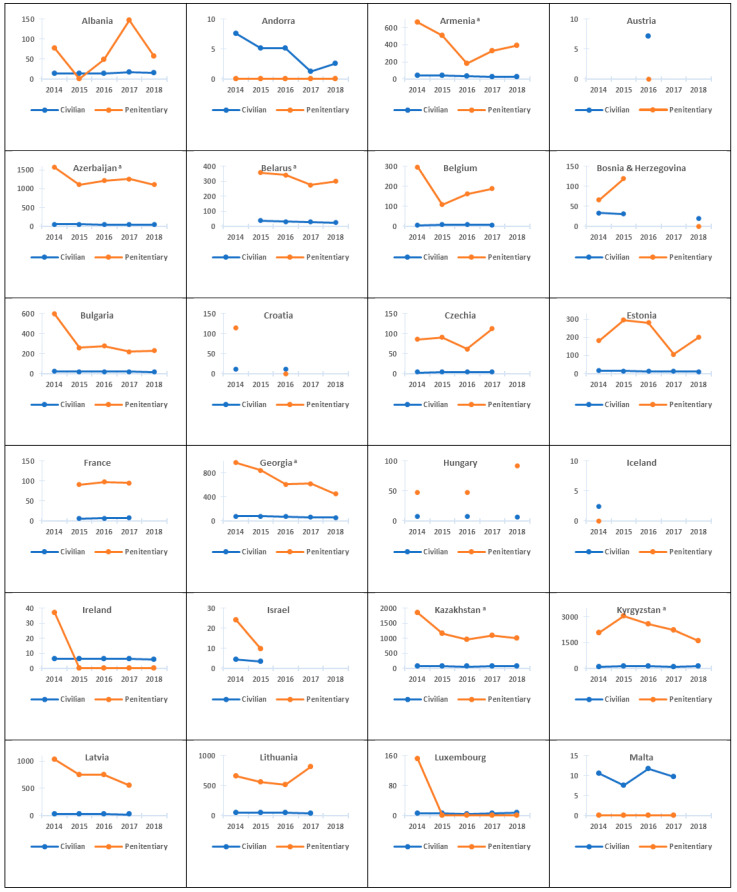

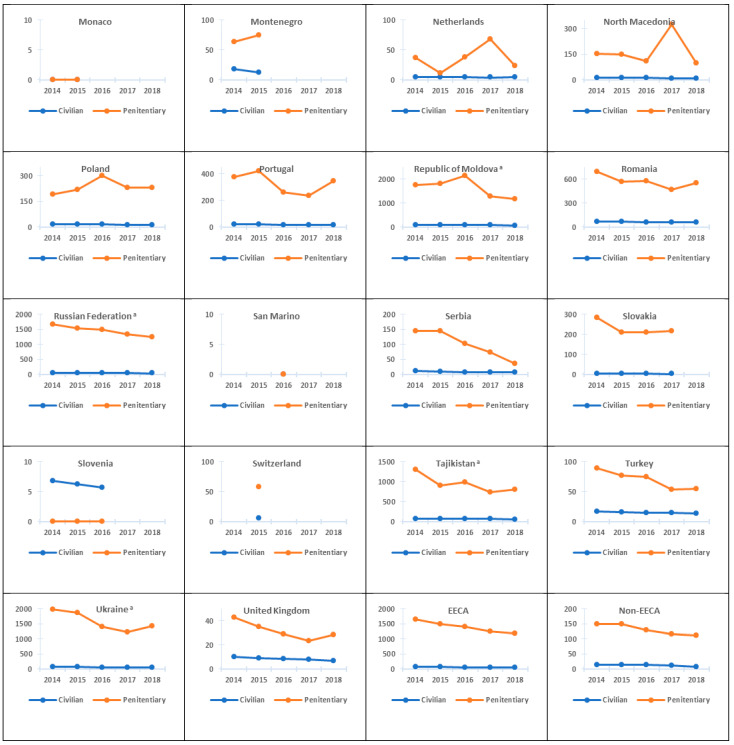

There was observed a decreasing trend in the notification of new TB cases and relapses both in the penitentiary and in the civil sector in 2014–2018 (Table 2 and Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Trends in TB notification rates in the civilian and penitentiary sectors, WHO European Region, 2014–2018. TB: tuberculosis; WHO: World Health Organization. a EECA country. Note: TB notification rate: number of new and relapse tuberculosis cases registered and reported per 100,000 population.

In the 42 countries analysed, the average annual change in incident TB rates during the study period was −7.0% in the civilian sector and −10.9% in the penitentiary sector. The decline in incident TB rates among inmates in the nine EECA countries included in this study should be noted (from −6.0% in Kyrgyzstan to −16.5% in Georgia) (Table 2).

TB cases registered in prison’s inmates accounted for approximately 7% for all notified new and relapse TB patients in EECA countries, with the highest level in the Russian Federation (10%); in comparison, in the other countries in the region the proportion was 1.5%, with the highest level in Slovakia (6.3%) in 2014–2018.

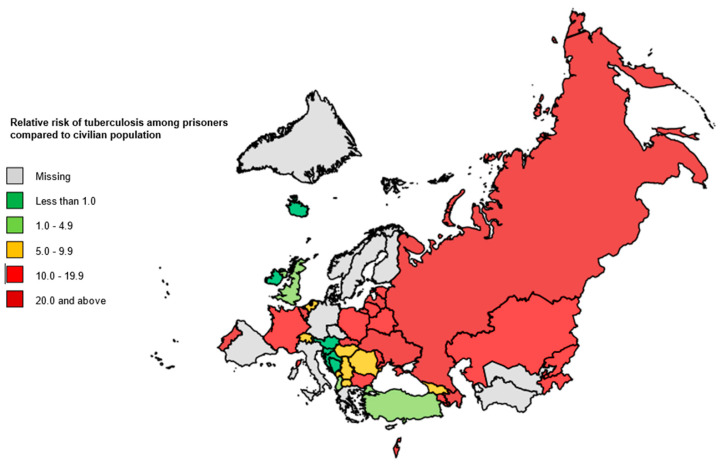

Prison’s inmates in the Russian Federation and Slovakia had the highest risks of developing an active TB disease compared with their respective civilian populations (RR = 25, confidence interval CI: 25–26, and RR = 57 (CI: 35–92)), respectively, in the last reported year. (Table 3 and Figure 4).

Table 3.

Notifications of new and relapse TB cases in the civilian and penitentiary sectors and relative risks (RR) of developing TB for inmates in relation to the civilian population, WHO European Region, 2014–2018.

| Country | N&R Notified, n | N&R Notified, Civilian Sector, n a | N&R Notified, Penitentiary Sector, n | RR (95% CI) | Reported Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albania | 440 | 437 | 3 | 3.74 (1.20–11.64) | 2018 |

| Andorra | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2018 |

| Armenia b | 734 | 720 | 14 | 16.15 (9.53–27.38) | 2018 |

| Austria | 619 | 619 | 0 | 0 | 2016 |

| Azerbaijan b | 5038 | 4822 | 216 | 22.78 (19.89–26.09) | 2018 |

| Belarus b | 2359 | 2253 | 106 | 12.56 (10.34–15.26) | 2018 |

| Belgium | 916 | 896 | 20 | 23.96 (15.39–37.30) | 2017 |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 666 | 666 | 0 | 0 | 2018 |

| Bulgaria | 1323 | 1307 | 16 | 12.33 (7.54–20.18) | 2018 |

| Croatia | 449 | 449 | 0 | 0 | 2016 |

| Czechia | 499 | 474 | 25 | 25.19 (16.85–37.66) | 2017 |

| Estonia | 145 | 140 | 5 | 18.83 (7.72–45.90) | 2018 |

| France | 4839 | 4774 | 65 | 12.93 (10.12–16.51) | 2017 |

| Georgia b | 2315 | 2272 | 43 | 7.86 (5.82–10.62) | 2018 |

| Hungary | 737 | 728 | 9 | 6.33 (3.28–12.21) | 2016 |

| Iceland | 8 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 2014 |

| Ireland | 294 | 294 | 0 | 0 | 2018 |

| Israel | 280 | 278 | 2 | 10.19 (2.50–41.45) | 2015 |

| Kazakhstan b | 1283 | 12,479 | 353 | 14.55 (13.10–16.17) | 2018 |

| Kyrgyzstan b | 6338 | 6198 | 140 | 13.24 (11.21–15.63) | 2018 |

| Latvia | 543 | 522 | 21 | 20.68 (13.39–31.95) | 2017 |

| Lithuania | 1268 | 1214 | 54 | 19.29 (14.70–25.30) | 2017 |

| Luxembourg | 42 | 42 | 0 | 0 | 2018 |

| Malta | 42 | 42 | 0 | 0 | 2017 |

| Monaco | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2015 |

| Montenegro | 80 | 79 | 1 | 5.92 (0.82–42.50) | 2015 |

| Netherlands | 791 | 784 | 7 | 5.22 (2.48–10.97) | 2018 |

| North Macedonia | 217 | 214 | 3 | 9.71 (3.11–30.33) | 2018 |

| Poland | 5196 | 5025 | 171 | 17.35 (14.90–20.20) | 2018 |

| Portugal | 1856 | 1812 | 44 | 21.38 (15.86–28.83) | 2018 |

| Republic of Moldova b | 3022 | 2933 | 89 | 16.16 (13.1–19.93) | 2018 |

| Romania | 15,586 | 11,472 | 114 | 9.35 (7.78–11.24) | 2018 |

| Russian Federation b | 78,258 | 70,967 | 7291 | 25.46 (24.85–26.07) | 2018 |

| San Marino | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2018 |

| Serbia | 641 | 637 | 4 | 5.11 (1.91–13.65) | 2018 |

| Slovakia | 228 | 210 | 18 | 56.66 (35.03–91.64) | 2017 |

| Slovenia | 118 | 118 | 0 | 0 | 2016 |

| Switzerland | 531 | 527 | 4 | 9.16 (3.43–24.49) | 2015 |

| Tajikistan b | 5726 | 5605 | 121 | 12.98 (10.85–15.53) | 2018 |

| Turkey | 11,576 | 11,421 | 155 | 3.97 (3.39–4.65) | 2018 |

| Ukraine b | 26,512 | 25,745 | 767 | 24.12 (22.46–25.90) | 2018 |

| United Kingdom | 5248 | 5226 | 22 | 3.0 (1.98–4.57) | 2017 |

CI: confidence interval; EECA: east European central Asia; N&R: new and relapse TB cases; RR: relative risks; TB: tuberculosis; WHO: World Health Organization. a Reference data for risk comparison. b EECA country.

Figure 4.

Relative risks of developing TB among prisons’ inmates compared to civilian population, WHO European Region, 2014–2018. TB: tuberculosis; WHO: World Health Organization.

3.2. Treatment Outcomes in TB Patients on First-Line Drug (FLD) Treatment Schemes

A total of 39 (74%) countries in the WHO European Region reported treatment outcomes for at least one cohort of TB patients, both civilians and inmates, who started on one of the FLD treatment schemes between 2012 and 2016 (Table 1 and Figure 1). Table 4 shows both the favourable and unfavourable treatment outcomes for civilians and inmates in these 39 countries.

Table 4.

Favourable and unfavourable TB treatment outcomes for civilians and inmates on first-line drug treatment schemes, 2012–2016 cohorts, WHO European Region.

| a. Civilian Sector | |||||||

| Country | Overall, n | Favourable Outcome, n (%) | Unfavourable Outcome | Not Evaluated, n (%) | Last Reported Cohort | ||

| Failure, n (%) | Died, n (%) | LTFU, n (%) | |||||

| Albania | 406 | 355 (87.4) | 3 (0.7) | 10 (2.5) | 20 (4.9) | 18 (4.4) | 2016 |

| Andorra | 4 | 3 (75.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (25.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2016 |

| Armenia a | 861 | 695 (80.7) | 18 (2.1) | 48 (5.6) | 99 (11.5) | 1 (0.1) | 2016 |

| Azerbaijan a | 1270 | 1048 (82.5) | 71 (5.6) | 16 (1.3) | 113 (8.9) | 22 (1.7) | 2016 |

| Belarus a | 2076 | 1849 (89.1) | 44 (2.1) | 111 (5.3) | 68 (3.3) | 4 (0.2) | 2016 |

| Belgium | 955 | 782 (81.9) | 0 (0.0) | 58 (6.1) | 63 (6.6) | 52 (5.4) | 2016 |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 907 | 505 (55.7) | 13 (1.4) | 64 (7.1) | 3 (0.3) | 322 (35.5) | 2016 |

| Bulgaria | 1488 | 1270 (85.3) | 15 (1.0) | 122 (8.2) | 81 (5.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2016 |

| Cyprus | 55 | 37 (67.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 18 (32.7) | 2016 |

| Czechia | 492 | 335 (68.1) | 1 (0.2) | 82 (16.7) | 54 (11.0) | 20 (4.1) | 2016 |

| Estonia | 158 | 125 (79.1) | 3 (1.9) | 26 (16.5) | 2 (1.3) | 2 (1.3) | 2016 |

| Georgia a | 2666 | 2226 (83.5) | 52 (2.0) | 112 (4.2) | 232 (8.7) | 44 (1.7) | 2016 |

| Hungary | 847 | 598 (70.6) | 18 (2.1) | 101 (11.9) | 78 (9.2) | 52 (6.1) | 2015 |

| Ireland | 286 | 103 (36.0) | 0 (0.0) | 16 (5.6) | 2 (0.7) | 165 (57.7) | 2016 |

| Israel | 261 | 216 (82.8) | 1 (0.4) | 19 (7.3) | 8 (3.1) | 17 (6.5) | 2015 |

| Kazakhstan a | 13,372 | 12,188 (91.1) | 396 (3.0) | 666 (5.0) | 122 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 2015 |

| Kyrgyzstan a | 5910 | 4838 (81.9) | 108 (1.8) | 351 (5.9) | 591 (10.0) | 22 (0.4) | 2016 |

| Latvia | 560 | 477 (85.2) | 0 (0.0) | 52 (9.3) | 28 (5.0) | 3(0.5) | 2016 |

| Lithuania | 1126 | 949 (84.3) | 12 (1.1) | 109 (9.7) | 51 (4.5) | 5 (0.4) | 2016 |

| Luxembourg | 37 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | 36 (97.3) | 2014 |

| Malta | 49 | 37 (75.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.0) | 3 (6.1) | 8 (16.3) | 2013 |

| Monaco | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2014 |

| Montenegro | 79 | 73 (92.4) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.8) | 3 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | 2015 |

| Netherlands | 850 | 741 (87.2) | 0 (0.0) | 30 (3.5) | 33 (3.9) | 46 (5.4) | 2016 |

| North Macedonia | 260 | 230 (88.5) | 1 (0.4) | 18 (6.9) | 10 (3.8) | 1 (0.4) | 2016 |

| Poland | 5904 | 3187 (54.0) | 3 (0.1) | 578 (9.8) | 361(6.1) | 1775 (30.1) | 2016 |

| Portugal | 1833 | 1298 (70.8) | 0 (0.0) | 131 (7.1) | 60 (3.3) | 344 (18.8) | 2016 |

| Republic of Moldova a | 2909 | 2398 (82.4) | 70 (2.4) | 292 (10.0) | 114 (3.9) | 35 (1.2) | 2016 |

| Romania | 12,304 | 10,578 (86.0) | 193 (1.6) | 996 (8.1) | 518 (4.2) | 19 (0.2) | 2016 |

| Russian Federation a | 64,591 | 47,524 (73.6) | 3761 (5.8) | 7098 (11.0) | 3213 (5.0) | 2995 (4.6) | 2016 |

| San Marino | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2015 |

| Serbia | 722 | 583 (80.7) | 6 (0.8) | 64 (8.9) | 26 (3.6) | 43 (6.0) | 2016 |

| Slovakia | 262 | 224 (85.5) | 0 (0.0) | 27 (10.3) | 2 (0.8) | 9 (3.4) | 2016 |

| Slovenia | 129 | 105 (81.4) | 0 (0.0) | 21 (16.3) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.3) | 2015 |

| Tajikistan a | 5254 | 4690 (89.3) | 103 (2.0) | 223 (4.2) | 195 (3.7) | 43 (0.8) | 2016 |

| Turkey | 11,851 | 10,323 (87.1) | 31 (0.3) | 698 (5.9) | 311 (2.6) | 488 (4.1) | 2016 |

| Ukraine a | 21,618 | 16,756 (77.5) | 1326 (6.1) | 2112 (9.8) | 1339 (6.2) | 85 (0.4) | 2016 |

| United Kingdom | 5649 | 4554 (80.6) | 0 (0.0) | 315 (5.6) | 262 (4.6) | 518 (9.2) | 2016 |

| Uzbekistan a | 13,783 | 11,667 (84.6) | 272 (2.0) | 615 (4.5) | 677 (4.9) | 552 (4.0) | 2012 |

| b. Penitentiary sector | |||||||

| Country | Overall, n | Favourable Outcome, n (%) | Unfavourable Outcome | Not Evaluated, n (%) | Last Reported Cohort | ||

| Failure, n (%) | Died, n (%) | LTFU, n (%) | |||||

| Albania | 3 | 2 (66.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (33.3) | 2016 |

| Andorra | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2016 |

| Armenia a | 8 | 8 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2016 |

| Azerbaijan a | 194 | 177 (91.2) | 2 (1.0) | 10 (5.2) | 5 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 2016 |

| Belarus a | 47 | 45 (95.7) | 1 (2.1) | 1 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2016 |

| Belgium | 18 | 11 (61.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (22.2) | 3 (16.7) | 2016 |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2016 |

| Bulgaria | 22 | 21 (95.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2016 |

| Cyprus | 1 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2016 |

| Czechia | 13 | 11 (84.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) | 2016 |

| Estonia | 8 | 8 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2016 |

| Georgia a | 49 | 37 (75.5) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.0) | 3 (6.1) | 7 (14.3) | 2016 |

| Hungary | 4 | 2 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2015 |

| Ireland | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2016 |

| Israel | 2 | 2 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2015 |

| Kazakhstan a | 634 | 503 (79.3) | 44 (6.9) | 8 (1.3) | 79 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2015 |

| Kyrgyzstan a | 162 | 130 (80.2) | 4 (2.5) | 9 (5.6) | 18 (11.1) | 1 (0.6) | 2016 |

| Latvia | 32 | 28 (87.5) | 1 (3.1) | 1 (3.1) | 1 (3.1) | 1 (3.1) | 2016 |

| Lithuania | 26 | 18 (69.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (7.7) | 6 (23.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2016 |

| Luxembourg | 1 | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2014 |

| Malta | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2013 |

| Monaco | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2014 |

| Montenegro | 1 | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2015 |

| Netherlands | 14 | 6 (42.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (28.6) | 4 (28.6) | 2016 |

| North Macedonia | 3 | 2 (66.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2016 |

| Poland | 195 | 113 (57.9) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (2.1) | 3 (1.5) | 75 (38.5) | 2016 |

| Portugal | 39 | 18 (46.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 20 (51.3) | 2016 |

| Republic of Moldova a | 139 | 117 (84.2) | 7 (5.0) | 2 (1.4) | 9 (6.5) | 4 (2.9) | 2016 |

| Romania | 155 | 145 (93.5) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (3.9) | 4 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 2016 |

| Russian Federation a | 8546 | 4811 (56.3) | 841 (9.8) | 325 (3.8) | 328 (3.8) | 2241 (26.2) | 2016 |

| San Marino | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2015 |

| Serbia | 11 | 7 (63.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (9.1) | 3 (27.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2016 |

| Slovakia | 17 | 17 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2016 |

| Slovenia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2015 |

| Tajikistan a | 70 | 61 (87.1) | 1 (1.4) | 5 (7.1) | 3 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2016 |

| Turkey | 166 | 139 (83.7) | 1 (0.6) | 7 (4.2) | 14 (8.4) | 5 (3.0) | 2016 |

| Ukraine a | 997 | 478 (47.9) | 434 (43.5) | 28 (2.8) | 48 (4.8) | 9 (0.9) | 2016 |

| United Kingdom | 26 | 16 (61.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.8) | 2 (7.7) | 7 (26.9) | 2016 |

| Uzbekistan a | 349 | 238 (68.2) | 38 (10.9) | 38 (10.9) | 10 (2.9) | 25 (7.2) | 2012 |

LTFU: lost to follow-up; TB: tuberculosis; WHO: World Health Organization. a EECA country.

Our study highlights a few countries where there were higher levels of unfavourable outcomes for inmates when compared with civilians, for example, Cyprus (100% vs. 0%), the Netherlands (29% vs. 9%) and Kazakhstan (21% vs. 9%). On the other hand, a higher proportion of unfavourable treatment outcomes among civilians than among inmates had been registered in the Czech Republic (28% vs. 8%), Andorra (25% vs. 0%), Estonia (20% vs. 0%), Armenia (19% vs. 0%), and Slovenia (16% vs. 0%).

A total of 12 of the 39 countries achieved TB treatment success rates of over 85% among inmates. In two EECA countries, Belarus and Tajikistan and in five other countries, Bulgaria, Latvia, Montenegro, Romania, Slovakia, the favourable outcomes were more than 85% in both sectors civilian and penitentiary.

4. Discussion

Recent systematic review by Cords et al. revealed a concerning scale of TB burden among people experiencing incarceration in different parts of the world and highlighted the high risk of contracting M tuberculosis infection and developing active disease, compared to the general population [12].

This is the first standardized study on TB morbidity and its treatment outcomes monitoring in the penitentiary sectors of such a scale in the WHO European Region. The main finding of our study is that from 2014 to 2018 the annual incident TB notification rates in prisons across the European Region decreased much faster than in the civilian population, which most likely reflects the decline of true burden in the prison populations. This finding highlights the positive impacts of the TB control interventions carried out by national governments, with the support of international agencies [20,21]. Another finding of our study is that, even though the annual decline of the TB burden in WHO European Region prisons was faster than in the civilian sector, the risk of developing TB disease in prisons is up to 57 times higher compared to the civilian sector. The increased risk of TB for inmates in EECA countries is a known feature of the region and has been previously described in several studies [11,22,23,24]. High prevalence of active TB disease in correctional facilities is fuelled by intra-institutional transmission due to prolonged stays in overcrowded facilities with poor ventilation, along with risk factors, which amplify the risk of TB disease, such as HIV, malnutrition, diabetes, smoking, a history of alcohol and illicit drug consumption, and former TB disease [9,10,25,26]. Theoretically, prison settings offer great opportunities for TB control, and there are practical examples from the region’s prisons in which significant improvements in their TB and rifampicin-resistant-TB burdens have been reported, and WHO-recommended screening, diagnostics, treatment, and linkage to civilian health care is ensured [27,28,29,30]. The high TB morbidity rates in the region’s prisons, of up to 1623 per 100,000 population in 2018, underline the need for substantial improvements in TB control among inmates through wider application of the best practices in the field.

In the majority of EECA countries, treatment success rates for TB in inmates were lower compared with rates in civilian populations, which was not evident for the other countries in the region. This emphasizes the critical need for improvements in the TB services available to inmates. Although the specific reasons for unfavourable treatment outcomes in inmates were not analysed in this study, there is evidence that high drug-resistance rates, insufficient laboratory diagnosis capacities and weak integrations between civilian and prison healthcare services, including ensuring the continuity of TB treatment after release from prison, are major factors leading to poor treatment outcomes in prisons [6,31].

Decarceration and other countries’ justice reforms that lead to it would reduce overcrowding, which is a major environmental factor for tuberculosis transmission, and would significantly reduce TB burden and its rising rates in prisons. Meanwhile, improving the TB situation and treatment outcomes for inmates can only be achieved with governmental commitment, inter-department cooperation for ensuring interventions equivalent to those in the civilian system and in close collaboration with it, and partnerships with civil society organizations. National tuberculosis programmes (NTPs) should develop operational plans and policies that optimize TB control in prisons and for inmates after their release and strengthen the capacities of prison health units for TB case management. Improving treatment outcomes for inmates will also prevent transmission of disease to other inmates, prison staff and community members. The End TB Strategy goals [32] will not be met without the implementation of effective measures in prisons where there are a large number of people who are vulnerable to TB and who engage in behaviours, which also put them at high risk for HIV infection.

One of the limitations of our current study is immediately apparent from the observation of the poor reporting of TB in prisons: in the 5-year study period, there was no available data for 11 WHO European Region countries. In addition, huge fluctuations in the reported annual incident TB rates in prisons reflect uncontrolled epidemics. It is important to note that poor TB reporting affects TB morbidity statistics and, consequently, TB estimates at national and international levels.

This study revealed that some high TB burden countries, such as Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, have not reported any TB cases among inmates. Cooperation between the institutions responsible for health care in penitentiary systems and the ministries of health should further improve to allow proper TB recording and reporting in both the civilian and penitentiary systems of all countries in the WHO European Region.

5. Conclusions

This review provides an overview of active TB in prisons in the WHO European Region. The completeness of TB reporting for prisons by NTPs was 79% (42 out of 53 countries from the WHO European Region). Our analysis highlights the vulnerability of inmates to TB and emphasises the necessity of improving TB prevention and care policies and their practical application in prisons with respect to active TB detection, infection control, TB treatment and continuity of care. Most countries achieved a substantial decline of TB burden in prisons, which indicates the effectiveness of recent interventions in correctional institutions. These results provide the basis for an understanding that TB prevention and care in prisons should be elevated to be a health care priority and should facilitate intersectional collaboration between civilian health authorities and prison administrations to enable ending TB in the WHO European Region.

5.1. Supporting Information Captions

5.1.1. Evidence Available Prior to This Study

TB surveillance data from the WHO European Region were collected annually from countries via The WHO global TB data collection system [14]. The WHO Regional Office for Europe and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) have jointly coordinated the collection and analysis of TB surveillance data in the WHO European Region, aiming to ensure data timeline consistency and comparability, pan-European coverage and avoidance of data duplication [1].

5.1.2. Added Value of the Study

This article provides a full cascade analysis of the TB burden and treatment outcomes at the regional level, designated by countries and subregional groupings.

5.1.3. Implications of All Available Evidence

Further efforts should be made to reduce TB infection transmission, the development of active TB and acquisition of data on treatment outcomes either via WHO data collection or reports from individual countries. In particular, more attention needs to be placed on addressing the known risk factors associated with TB.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the national TB counterparts in the WHO European Region, including the nominated operational contact points for TB surveillance in the Member States of the WHO European Region for providing data for this analysis based on the WHO mandate for surveillance and response monitoring of the End TB Strategy implementation.

Author Contributions

A.D., S.A. and M.D. prepared the study aims. All authors participated in the design, discussion of the results interpretation, read, edited and agreed with the decision to submit the final version of the paper. A.D., A.C., A.H., N.A. and O.K. designed and executed the analysis. A.D. and A.C. led the data collection and reference reviews. A.C. and A.D. wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and A.H., N.A., E.G., S.D., R.M., O.G., S.A. and M.D. provided substantial revisions to the initial version of the manuscript. M.D. provided substantial revisions to the advanced version of the manuscript. A.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This analysis was funded by the United States Agency for International Development via WHO consolidated grant GHA-G-00-09-00003.

Institutional Review Board Statement

We used secondary, aggregated (not case based) data, available on the public domain of WHO. Collection of these data collected is granted by the WHO member states and induced by the resolution EB134.R4 of the 134th session of the World Health Assembly.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available in a publicly accessible repository hosted by WHO https://www.who.int/teams/global-tuberculosis-programme/data. (accessed on 12 June 2021).

Conflicts of Interest

None of the authors have conflict of interest to declare. The views and opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and not necessarily the views and decisions or policies of the World Health Organization, and/or the United States Agency for International Development. The designations used and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WHO and USAID concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, nor concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.WHO Regional Office for Europe/European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control . Tuberculosis Surveillance and Monitoring in Europe 2021—2019 Data. WHO Regional Office for Europe; Copenhagen, Denmark: 2021. [(accessed on 12 June 2021)]. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/communicable-diseases/tuberculosis/publications/2021/tuberculosis-surveillance-and-monitoring-in-europe-2021-2019-data. [Google Scholar]

- 2.USAID . Tuberculosis in Prisons: A Growing Public Health Challenge. United States Agency for International Development; Washington, DC, USA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coyle A., Heard C., Fair H. Detention: Addressing the human cost. Current trends and practices in the use of imprisonment. Int. Rev. Red Cross. 2016;98:761–781. doi: 10.1017/S1816383117000662. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walmsley R. World Prison Population List. 11th ed. Institute for Criminal Policy Research; London, UK: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walmsley R. World Prison Population List. 12th ed. Institute for Criminal Policy Research; London, UK: 2018. [(accessed on 12 June 2021)]. Available online: http://www.prisonstudies.org/sites/default/files/resources/downloads/wppl_12.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dara M., Acosta C.D., Melchers N.V., Al-Darraji H.A., Chorgoliani D., Reyes H. Tuberculosis control in prisons: Current situation and research gaps. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2015;32:111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dara M., Chadha S.S., Melchers N.V., van den Hombergh J., Gurbanova E., Al-Darraji H., Van Der Meer J.B.W. Time to act to prevent and control tuberculosis among inmates. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2013;17:4–5. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.12.0909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baussano I., Williams B.G., Nunn P. Tuberculosis incidence in prisons: A systematic review. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000381. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winetsky D.E., Almukhamedov O., Pulatov D., Vezhnina N., Dooronbekova A., Zhussupov B. Prevalence, risk factors and social context of active pulmonary tuberculosis among prison inmates in Tajikistan. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e86046. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alavi S.M., Bakhtiarinia P., Eghtesad M., Albaji A., Salmanzadeh S. A comparative study on the prevalence and risk factors of tuberculosis among the prisoners in Khuzestan, South-West Iran. Jundishapur J. Microbiol. 2014;7:e18872. doi: 10.5812/jjm.18872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stuckler D., Basu S., McKee M., King L. Mass incarceration can explain population increases in TB and multidrug-resistant TB in European and central Asian countries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:13280–13285. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801200105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cords O., Martinez L., Warren J.L., O’Marr J.M., Walter K.S., Cohen T., Zheng J., Ko A.I., Croda J., Andrews J.R. Incidence and prevalence of tuberculosis in incarcerated populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2021;6:e300–e308. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00025-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aerts A., Hauer B., Wanlin M. Tuberculosis and tuberculosis control in European prisons. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2006;10:1215–1223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.WHO . The WHO Global TB Data Collection System. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2021. [(accessed on 12 June 2021)]. Available online: https://extranet.who.int/tme/ [Google Scholar]

- 15.WHO . Countries. WHO Regional Office for Europe; Copenhagen, Denmark: 2021. [(accessed on 12 June 2021)]. Available online: http://www.euro.who.int/en/countries. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Union Nations DESA/Population Dynamics. World Population Prospects 2019. [(accessed on 12 June 2021)]. Available online: https://population.un.org/wpp/

- 17.World Prison Brief World Prison Brief Data: Europe. [(accessed on 12 June 2021)]. Available online: http://www.prisonstudies.org/map/europe.

- 18.Richard Lowry VassarStats: Website for Statistical computation. [(accessed on 12 June 2021)]. Available online: http://vassarstats.net/index.html.

- 19.WHO . Definitions and Reporting Framework for Tuberculosis—2013 Revision (Updated December 2014) World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 20.WHO . Prisons and Health. WHO Regional Office for Europe; Copenhagen, Denmark: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee D., Lal S.S., Komatsu R., Zumla A., Atun R. Global fund financing of tuberculosis services delivery in prisons. J. Infect Dis. 2012;205((Suppl. S2)):S274–S283. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grady J., Maeurer M., Atun R. Tuberculosis in prisons: Anatomy of global neglect. Eur. Respir. J. 2011;38:752–754. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00041211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruddy M., Balabanova Y., Graham C., Fedorin I., Malomanova N., Elisarova E., Kuznetznov S., Gusarova G., Zakharova S., Melentyev A., et al. Rates of drug resistance and risk factor analysis in civilian and prison patients with tuberculosis in Samara Region, Russia. Thorax. 2005;60:130–135. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.026922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stern V. The House of the Dead Revisited: Prisons, Tuberculosis and Public Health in the Former Soviet Bloc. In: Zumla A., Gandy M., editors. the Return of the White Plague: Global Poverty and the “New” Tuberculosis. Verso; London, UK: 2003. pp. 178–194. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chaves F., Dronda F., Alonso-Sanz M., Gonzalez-Lopez A., Eisenach K. A longitudinal study of transmission of tuberculosis in a large prison population. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1997;155:719–725. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.2.9032218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larouzé B., Ventura M., Sánchez A.R., Diuana V. Tuberculose nos presídios brasileiros: Entre a responsabilização estatal e a dupla penalização dos detentos. Cad. Saúde Pública. 2015;31:1127–1130. doi: 10.1590/0102-311XPE010615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kamarulzaman A., Reid S.E., Schwitters A., Wiessing L., El-Bassel N., Dolan K. Prevention of transmission of HIV, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and tuberculosis in prisoners. Lancet. 2016;388:1115–1126. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30769-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gurbanova E., Mehdiyev R., Blondal K., Altraja A. Rapid tests reduce the burden of tuberculosis in Azerbaijan prisons: Special emphasis on rifampicin-resistance. Rev. Esp. Sanid. Penit. 2018;20:111–120. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gurbanova E., Mehdiyev R., Blondal K., Altraja A. Predictors of cure in rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis in prison settings with low loss to follow-up. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2016;20:645–651. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.15.0545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gegia M., Kalandadze I., Madzgharashvili M., Furin J. Developing a human rights-based program for tuberculosis control in Georgian prisons. Health Hum. Rights. 2011;13:E73–E81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Binswanger I.A., Stern M.F., Deyo R.A., Heagerty P.J., Cheadle A., Elmore J.G., Koepsell T.D. Release from prison—A high risk of death for former inmates. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;356:157–165. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa064115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.WHO . The End TB Strategy: Global Strategy and Targets for Tuberculosis Prevention, Care and Control after 2015. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2014. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data available in a publicly accessible repository hosted by WHO https://www.who.int/teams/global-tuberculosis-programme/data. (accessed on 12 June 2021).