Abstract

Sirtuins are key players for maintaining cellular homeostasis and are often deregulated in different human diseases. SIRT7 is the only member of mammalian sirtuins that principally resides in the nucleolus, a nuclear compartment involved in ribosomal biogenesis, senescence, and cellular stress responses. The ablation of SIRT7 induces global genomic instability, premature ageing, metabolic dysfunctions, and reduced stress tolerance, highlighting its critical role in counteracting ageing-associated processes. In this review, we describe the molecular mechanisms employed by SIRT7 to ensure cellular and organismal integrity with particular emphasis on SIRT7-dependent regulation of nucleolar functions.

Keywords: sirtuins, SIRT7, deacetylation, stress responses, nucleolus

1. Mammalian Sirtuins: General Functions and Activation in Response to Stress

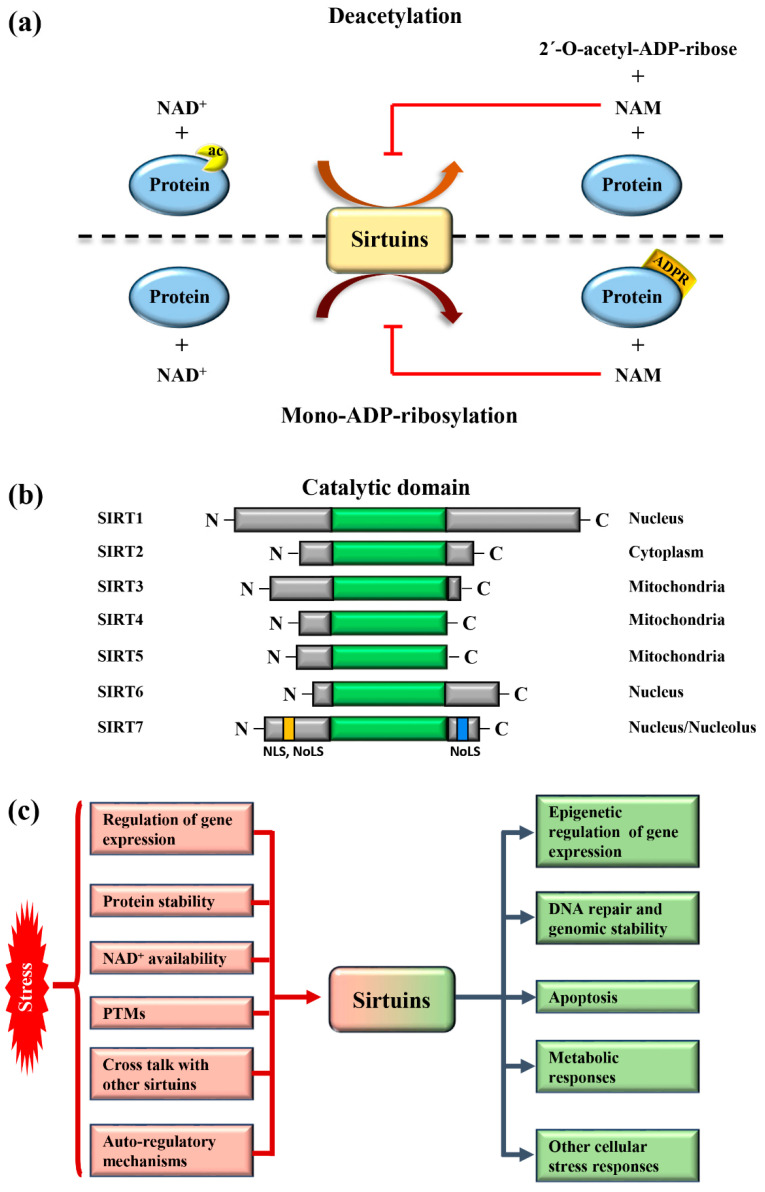

Sirtuins are highly conserved enzymes that principally act as NAD+-dependent histone/protein deacetylases although some members also possess mono-ADP ribosylation and other less characterized activities [1,2,3,4,5,6]. For deacetylation, sirtuins catalyze the transfer of the acetyl group from the substrate to NAD+, concomitant with the release of 2’–O-acetyl-ADP-ribose and nicotinamide (NAM). During mono-ADP ribosylation, the ADP-ribose (ADPR) is transferred from NAD+ to the target protein and NAM is released (Figure 1a). Interestingly, NAM is a potent inhibitor of sirtuins, suggesting the presence of a finely controlled negative auto-regulatory loop, modulating the enzymatic activity (Figure 1a). In mammals, seven sirtuin members (SIRT1–SIRT7) have been described. These molecules share a conserved catalytic domain but differ substantially in their N-terminal and C-terminal sequences, which are fundamental for interactions with specific targets as well as for the specification of subcellular localization. Sirtuins are found in different cellular compartments: SIRT1, SIRT6, and SIRT7 are principally localized in the nucleus while other sirtuins reside in the mitochondria or in the cytoplasm as illustrated in Figure 1b. SIRT7 is the only member of the family that is highly enriched in the nucleolus due to the presence of nuclear and nucleolar localization sequences at the N-terminal and C-terminal regions [7] (Figure 1b). Sirtuins efficiently shuttle between different compartments in response to numerous intracellular and extracellular stimuli to promote the activation of specific signaling pathways. These molecules activate a complex network of cellular responses to stress to maintain cellular homeostasis, including regulation of the transcription of specific target genes, modulation of chromatin structure, activation of mechanisms of DNA repair, metabolic adaptation to stress, and modulation of apoptosis among others [8] (Figure 1c). The ability of sirtuins to control such a broad range of biological functions mainly derives from their capacity to control both chromatin-related and -unrelated targets. Sirtuins act as potent epigenetic silencers by promoting heterochromatin formation through the direct deacetylation of different histone marks or indirectly by controlling the activity of numerous histone modifiers such as methytransferases and acetyltransferases [8,9]. Notwithstanding, sirtuins control the activity and functions of enzymes, transcription factors, and other chromatin unrelated molecules mainly through direct deacetylation, highlighting their complex functions in the regulation of cellular processes [3].

Figure 1.

Mammalian sirtuins: general functions and activation in response to stress (a) Schematic representation of the main enzymatic activities of mammalian sirtuins. Sirtuins catalyze deacetylation of protein targets by transferring the acetyl group to NAD+, concomitant with the release of nicotinamide (NAM) and 2′-O-acetyl-ADP-ribose (upper panel). In the mono-ADP-ribosylation reaction, the ADP-ribose (ADPR) is transferred from NAD+ to the substrate, leading to release of NAM (lower panel). NAM is a potent inhibitor of the enzymatic activity of sirtuins. (b) Schematic representation of the structure and subcellular distribution of mammalian sirtuins. SIRT7 nuclear and nucleolar localization sequences (NLS and NoLS, respectively) are indicated. (c) Scheme depicting the mechanisms involved in sirtuins activation following stress (red) and their main biological functions (green).

Due to their critical role in modulating stress related cellular reactions, sirtuins act as key anti-ageing molecules in low eukaryotes as well as in mammals and are assumed to promote life span extension [6]. Consistently, age-dependent decline in sirtuins expression and/or activity has been associated with the onset of severe aging-associated diseases such as cardiovascular diseases [3,10], diabetes [11], inflammation [12], neurological disorders [13], and cancer [14].

Different mechanisms are employed to promptly activate sirtuins following stress. Stressors modulate sirtuin genes’ expression, protein stability, or control their binding to specific inhibitors [5] (Figure 1c). Moreover, the strict dependency of the catalytic activity of sirtuins on NAD+ allows swift adaption to the metabolic state of cells. Stress conditions such as glucose deprivation or caloric restriction (CR), which increase NAD+ levels due to enhanced mitochondrial respiration and dramatically induce sirtuins expression and/or activity [6] (Figure 1c). CR represents the most prominent intervention to delay ageing and extend life span in different experimental organisms [15]. Different studies demonstrated that the beneficial effects of CR can be attributed to the activation of sirtuins, at least in part [16]. Thus, the activation of sirtuins might improve cellular adaptation to stress, induced by nutrient deprivation.

The acquisition of specific post-translational modifications (PTMs) such as phosphorylation, methylation, and ubiquitination, among others, represents another mechanism to control the activity of sirtuins. PTMs control the interaction of sirtuins with specific targets, their subcellular localization and catalytic activity, in some cases by interfering with the capacity to bind NAD+ [17,18,19]. Intriguingly, recent studies also demonstrated that mammalian sirtuins possess auto-regulatory mechanisms. For instance, SIRT1 is capable of auto-catalytic activation by auto-deacetylation [20] while SIRT7 possesses auto-mono-ADP ribosylation activity [1]. Interestingly, cross-regulation between mammalian sirtuins is also employed to fine-tune their functions. The binding of SIRT7 to SIRT1 inhibits SIRT1 auto-catalytic activation resulting in the stimulation of adipogenesis and destabilization of constitutive heterochromatin [9,20]. In sharp contrast, binding of SIRT1 to SIRT7 is fundamental to promote the formation of ribosomal DNA heterochromatin and to repress E-cadherin expression, thus stimulating cancer metastasis [21,22]. Additionally, a synergistic effect between SIRT1 and SIRT6 has been described. SIRT1-mediated deacetylation of SIRT6 is fundamental for recruitment of SIRT6 to double strand breaks (DSBs), thereby facilitating chromatin remodeling required for efficient DNA repair [23]. These findings illustrate the complexity of the regulation of sirtuins under physiological and pathological conditions. More research is warranted to unveil the molecular mechanisms controlling the regulation of these molecules in stress induced cellular processes, in order to identify novel pathways suitable for therapeutic interventions in diseases characterized by alterations in functions of sirtuins (Figure 1c).

2. SIRT7 Controls Multiple Functions of the Nucleolus

2.1. SIRT7 Stimulates rDNA Transcription and Ribosomes Biogenesis

The nucleolus is the cellular compartment responsible for ribosomal DNA (rDNA) transcription and ribosomes biogenesis. This membrane-less organelle is arranged around actively transcribed rDNA genes as a result of the recruitment of RNA binding proteins, ribosomal proteins, and other molecules involved in ribosome biogenesis with the nascent ribosomal RNA (rRNA) [24]. The assembly of the ribosomes is a highly regulated process that is tightly controlled in response to nutrient availability and other stimuli. The ribosomal rRNA is initially transcribed as a precursor pre-rRNA, which is then cleaved into the mature 28S, 18S, and 5.8S rRNAs. Small nucleolar ribonuclear proteins (snoRNPs) and small nucleolar RNAs together with other enzymes are required for efficient cleavage of the pre-rRNA and/or to catalyze the acquisition of critical post-transcriptional modifications. These events are indispensable for proper folding of rRNAs and their assembly with ribosomal proteins to generate the mature ribosome subunits [25,26].

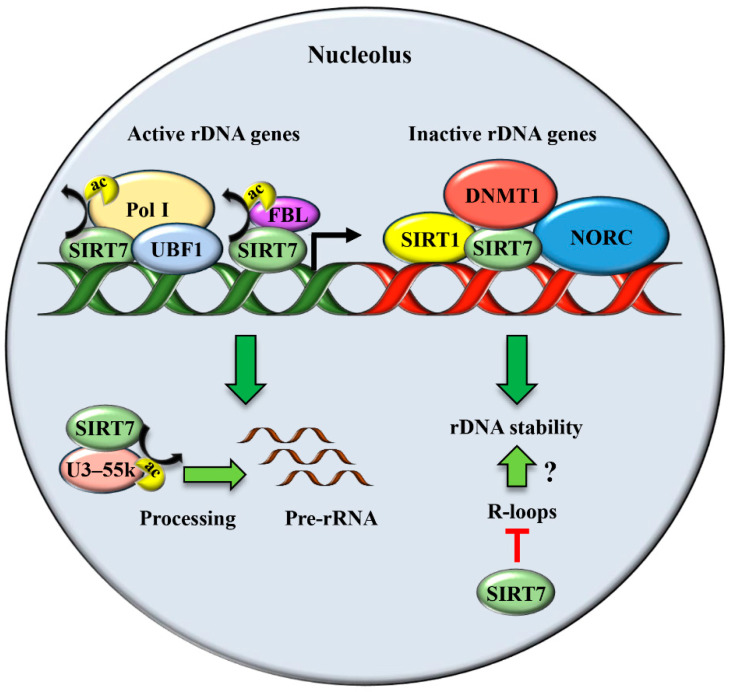

The enriched localization of SIRT7 in the nucleoli prompted different groups to investigate its biological functions in this nuclear compartment. SIRT7 emerged to be a critical factor that promotes rRNA transcription and maturation by acting at different levels. SIRT7 stimulates rDNA transcription by facilitating the recruitment of RNA polymerase I (Pol I) at rDNA genes both through its interaction with the transcription factor UBF1 and deacetylation of the Pol I subunit PAF53 [27,28]. Additionally, SIRT7 deacetylates the nucleolar protein fibrillarin (FBL), facilitating FBL-mediated histone methylation that is essential to activate rDNA transcription during interphase and its resumption at the end of mitosis (Figure 2 and Table 1) [29,30]. Besides stimulating rDNA transcription, SIRT7 facilitates pre-rRNA processing through deacetylation of U3–55k, a core component of the U3 snoRNP complex [31] (Figure 2 and Table 1). In sharp contrast, recent work demonstrated that SIRT7 epigenetically represses expression of specific ribosomal proteins, indicating a highly complex role of this molecule in the maintenance of ribosome homeostasis [32,33]. SIRT7 is also a critical regulator of RNA Pol III mediated transcription and stimulates expression of different tRNAs, suggesting that the capacity of SIRT7 to activate global protein biosynthesis employs additional mechanisms besides promoting ribosome biosynthesis [34].

Figure 2.

SIRT7 has a dual function in the unstressed nucleolus. SIRT7 stimulates rDNA transcription by facilitating recruitment of Pol I both by interacting with UBF1 and through direct deacetylation of the Pol I subunit PAF53. In addition, SIRT7 deacetylates fibrillarin (FBL) and thereby favors FBL-mediated chromatin remodeling required for stimulation of rDNA transcription. SIRT7 also promotes pre-rRNA processing by deacetylating U3–55k, a core component of the U3 snoRNP complex. SIRT7 is a key player for maintaining rDNA stability at inactive rDNA genes by promoting heterochromatin formation through recruitment of SIRT1, DNMT1, and the chromatin remodeling complex (NORC). Moreover, SIRT7 might maintain rDNA stability by facilitating resolution of R-loops.

Table 1.

Table summarizing SIRT7 nucleolar functions under physiological and stress conditions.

| SIRT7 Nucleolar Functions | ||

|---|---|---|

| Function | Cell Type | Condition |

| Stimulation of rDNA transcription and ribosome biogenesis | Cancer cell lines and human embryonic kidney cells | Physiological conditions [27,28,29,30,31]. |

| Maintenance of rDNA repeats integrity | Primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs), mouse liver, human fibroblast-like fetal lung cells | Physiological conditions [22,47]. |

| Resolution of R-loops | Cancer cell lines and human embryonic kidney cells | Physiological conditions [53]. |

| Stabilization of p53 through NPM deacetylation | Cancer cell lines, MEFs, mouse skin | UV irradiation [17] |

| Stabilization of p53 through MDM2 degradation | Cancer cell lines | glucose starvation [59] |

| Inhibition of pre-rRNA transcription following stress | Cancer cell lines and human embryonic kidney cells | Nutrient stress [28,66]. hypertonic stress [31]. |

Sustained ribosomes and protein biosynthesis are required for efficient cellular growth and are prominently enhanced in metabolically active tissues. Consistently, SIRT7 levels are elevated in highly proliferative tissues but are dramatically reduced in post-mitotic cells [27]. SIRT7 acts as a potent oncogene in different malignancies and is upregulated in numerous human cancers [35]. The SIRT7-mediated stimulation of ribosomes biogenesis is considered fundamental for SIRT7-dependent oncogenic functions, although other mechanisms are involved too [32,33,36]. In addition, the ability of SIRT7 to epigenetically suppress the expression of specific ribosomal proteins and the consequent alteration of the translation machinery has been proposed as an additional mechanism utilized by SIRT7 to contribute to oncogenic transformation [32].

2.2. SIRT7 Ensures Genomic Stability by Securing rDNA Repeats Integrity: A Link to Ageing?

Besides its well-characterized role in ribosomes biogenesis, the nucleolus has been recognized as a critical compartment involved in maintaining genomic stability, preventing ageing, and enabling cellular stress responses [37].

To fulfil metabolic requirements, cells possess multiple copies of head-to-tail arranged rDNA repeats that constitute the nucleolar organizer regions (NORs) [38]. However, at a given time, only a subset of rDNA genes is actively transcribed while roughly half of the rDNA repeats in mice are kept in a highly silenced state through formation of compact heterochromatin [39]. Due to their repetitive nature, the maintenance of proper compact heterochromatin at the rDNA repeats is fundamental to prevent homologous recombination. In yeasts, recombination of rDNA repeats and their exclusion from the genome results in the formation of extrachromosomal rDNA circles (ERCs) [40]. The redistribution of excised ERCs repeats throughout the nucleolus promotes the formation of ectopic nucleoli, which gives rise to a typical phenotype often referred to as “fragmented nucleolus”. The accumulation of ERCs and appearance of a fragmented nucleolus is considered to promote premature ageing in yeasts [40]. However, the exact mechanisms by which rDNA instability promotes ageing remains largely unknown. It was proposed that the accumulation of ERCs may bind and neutralized factors involved in the maintenance of a “young” cellular phenotype [41], although further studies demonstrated that rDNA instability per se can cause premature ageing, independently of ERCs accumulation, by promoting activation of the DNA damage response leading to cellular senescence [42,43]. The importance of maintenance of rDNA repeats and nucleolar integrity as a mechanism to prevent cellular senescence has also been proposed in mammals. Loss of rDNA genes occurs in humans during ageing [44,45] and several human diseases associated with genomic instability and signs of premature ageing show alterations or instability of rDNA repeats [37,40,46]. Sirtuins play a critical role in maintaining the stability of rDNA repeats. In yeasts, the sirtuin homologue SIR2 is critical to stabilize the number of rDNA repeats and to prevent the accumulation of ERCs. Consequently, ablation of SIR2 shortens life span while the expression of extra copies of SIR2 delays ageing [40].

Recent studies demonstrated that the function of sirtuins in the maintenance of rDNA stability is conserved in mammals [22,47]. The ablation of SIRT7 expression results in reduction of rDNA heterochromatin, loss of rDNA repeats, fragmentation of the nucleolus both in vitro and in vivo, and enhanced cellular senescence [22,47]. Intriguingly, SIRT7 deficient mice show premature signs of ageing and display enhanced genomic instability, suggesting that SIRT7 counteracts ageing by stabilizing rDNA chromatin [22,48,49]. Mechanistically, SIRT7 facilitates the formation of a condensed heterochromatin structure at rDNA repeats, which prevents homologous recombination, through different mechanisms. SIRT7 recruits SIRT1 at the rDNA genes and promotes SIRT1-dependent histone deacetylation [22]. In addition, SIRT7 enhances heterochromatin formation by facilitating the recruitment of DNA methyltransferase (DNMT1) and the nucleolar remodeling complex (NoRC) to rDNA repeats [22,47] (Figure 2 and Table 1). Furthermore, SIRT7 forms a molecular complex with SUV39H1, a methyltransferase responsible for the deposition of H3K9 methylation and heterochromatin formation [9]. Interestingly, SUV39H1 together with SIRT1, is a component of the energy-dependent nucleolar silencing complex (e-NOSC). E-NOSC contributes to heterochromatin formation and rDNA silencing during nutrient deprivation through SIRT1-dependent histone deacetylation and SUV39H1-mediated histone methylation [50]. The depletion of the SUV39H1 homologue in Drosophila melanogaster results in heterochromatin relaxation, rDNA instability and formation of ERCs, which is associated with the appearance of fragmented nucleoli [51]. Since the association of SUV39H1 to rDNA genes requires recruitment of SIRT1 and ablation of SIRT7 impairs SIRT1 binding at these chromosomal loci [22], it is reasonable to assume that the inactivation of SIRT7 will result in global reduction of e-NOSC recruitment at rDNA genes and subsequent loss of heterochromatin at these loci. However, further studies are required to support this claim. Thus, SIRT7 appears to exert different functions at active and inactive rDNA repeats. At inactive genes, SIRT7 promotes heterochromatin formation, thus maintaining their stability. At active rDNA repeats, SIRT7 stimulates Pol I-mediated rDNA transcription [47]. The simultaneous control of these opposite mechanisms by SIRT7 is surprising, since maintenance of rDNA repeats stability and rDNA transcription appear to be two distinct and unrelated events [52].

In a recent study, it was demonstrated that SIRT7 is involved in resolving R-loops inside and outside the nucleolus to safeguard genomic stability [53]. R-loops are stable hybrids between nascent RNA and DNA that form during replication. If not resolved, R-loops may cause stalling of the RNA polymerase and ultimately lead to formation of double strand breaks (DSBs) [38,53]. The high transcription rate of rDNA genes predisposes these loci to a dramatic accumulation of R-loops. Interestingly, the accumulation of R-loops has been connected with disrupted nucleolar architecture and appearance of a fragmented nucleolus in mammalian cells [54]. Hence, SIRT7 may control rDNA and global genomic stability by reducing R-loops accumulation within the nucleolus (Figure 2 and Table 1).

Taken together, SIRT7 is a critical factor for securing rDNA stability, which may be a crucial mechanism to prevent cellular senescence and extend life span. The pharmacological stimulation of SIRT7 appears promising for development of future anti-ageing therapies, although further research is required to substantiate this claim.

2.3. SIRT7 Triggers the Nucleolar Stress Response to Promote p53 Stabilization in Response to Specific Stress Stimuli

The nucleolus has been recognized as a critical sensor of numerous stressors and is a key player for activation of cellular stress response. Numerous molecules are stored in the nucleolus under physiological conditions. In response to stress, the nucleolus undergoes a profound reorganization leading to a release of these proteins into other cellular compartments, thus allowing their interaction with specific downstream targets and the activation of distinct signaling pathways. This phenomenon is collectively known as the nucleolar stress response (NSR) [55,56]. Compared to the initiation of gene expression, rapid mobilization of nucleolar factors following stress represents a means to promptly activate cellular responses such as cell cycle arrest, DNA repair, modulation of metabolic pathways and apoptosis to ensure cellular homeostasis [57].

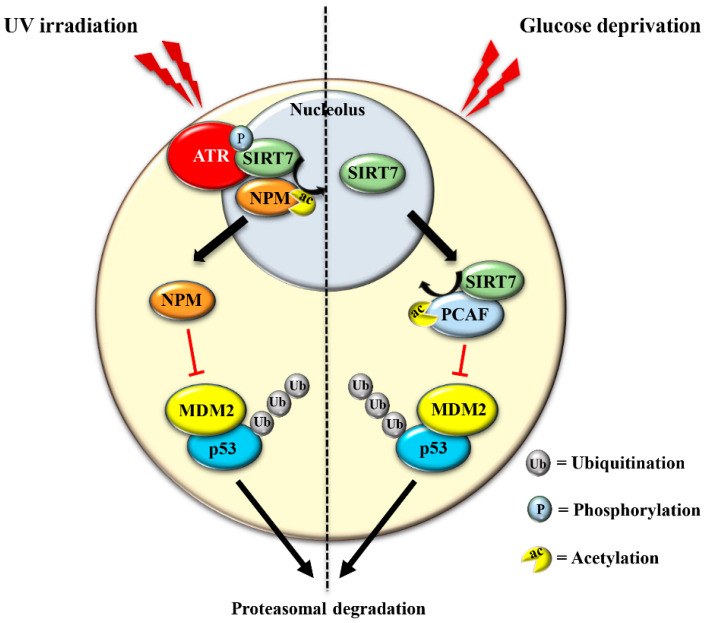

The best-characterized consequence of NSR is the rapid stabilization of the tumor suppressor p53. The induction of p53 levels following genotoxic stress is fundamental to ensure cell cycle inhibition, DNA repair or to induce apoptotic death of highly damaged cells. These mechanisms limit the propagation of cells that have acquired mutations and are thereby prone to oncogenic transformation. Without cellular stress, the tumor suppressor p53 is maintained at low levels, which is mainly achieved by the ubiquitin ligase MDM2 that promotes ubiquitination and the subsequent proteasomal degradation of p53. Induction of the NSR induces release of nucleolar proteins (most prominently nucleophosmin; NPM) as well as ribosomal proteins from maturing ribosomes. These molecules associate to MDM2 and disrupt binding of MDM2 to p53, thus promoting p53 stabilization [58]. Recent studies demonstrated that SIRT7 plays a fundamental role in activating this mechanism under specific stress conditions. In response to ultraviolet (UV)-induced genotoxic stress, SIRT7 enzymatic activity increases as a consequence of phosphorylation by the kinase ATR, a major player in the DNA damage response. Activated SIRT7 efficiently deacetylates its nucleolar target NPM favoring translocation of NPM from nucleoli to the nucleoplasm. Deacetylated, nucleoplasmic NPM binds to MDM2, prevents MDM2-dependent p53 degradation, and thus causes the rapid accumulation of p53 and enhanced p53-dependent cell cycle arrest [17] (Figure 3 and Table 1).

Figure 3.

SIRT7 promotes p53 stabilization in response to distinct stressors. In response to UV-induced stress, SIRT7 is activated by ATR-mediated phosphorylation. Activated SIRT7 efficiently deacetylates its nucleolar target nucleophosmin (NPM), facilitating its exclusion from nucleoli. Deacetylated NPM binds and inhibits the ubiquitin ligase MDM2, thereby preventing MDM2- dependent ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation of p53 (left panel). In response to glucose starvation, SIRT7 translocates from the nucleolus, associates and deacetylates PCAF, which favors PCAF-mediated degradation of MDM2, leading to p53 stabilization (right panel).

The translocation of SIRT7 in response to glucose starvation represents another mechanism to stabilize p53. Nucleoplasmic SIRT7 associates and deacetylates the acetyl transferase p300/CBP-associated factor (PCAF), which increases the binding of PCAF to MDM2 favoring MDM2 degradation, p53 stabilization, and cell cycle inhibition [59] (Figure 3 and Table 1). Apparently, distinct mechanisms are employed by SIRT7 to inhibit MDM2 for promoting p53 stabilization, depending on the type of stress [17,59]. On the other hand, SIRT7 is not always required for p53 stabilization. For example, SIRT7 has no impact on p53 stabilization following inhibition of rDNA transcription [17] and rather promotes p53 stabilization in response to specific stress stimuli although through still poorly characterized mechanisms [60]. The capacity of SIRT7 to directly deacetylate p53 and suppress its transcriptional activity adds another layer of complexity into the mechanisms by which SIRT7 controls the p53 pathway. Although some studies demonstrated that the deacetylation of p53 by SIRT7 suppresses its pro-apoptotic functions and favors cell survival under stress [61,62], other studies failed to identify p53 as a deacetylation target of SIRT7 under particular stress conditions or in vitro [32,59,63]. These apparently contradictory results suggest a highly complex role of SIRT7 in controlling the p53 pathway that warrants further research.

The induction of the NSR has been proposed as a novel target for anti-cancer therapies due to stimulation of p53 activity [64]. Further characterization of the mechanisms employed by SIRT7 to control p53 may be crucial for the development of novel pharmacological approaches to treat cancer.

2.4. Stress Signals Promote Exclusion of SIRT7 from Nucleoli: A Way to Inhibit rDNA Transcription

The exclusion of SIRT7 from nucleoli in response to different stress signals has been amply documented, indicating that exclusion of SIRT7 per se represents a hallmark of the NSR [36,65]. Several lines of evidence suggest a dynamic role of SIRT7 in the stressed nucleolus that might be employed to fine-tune activation of distinct cellular responses. In the early phase of the NSR, SIRT7 activates specific signaling pathways through deacetylation of nucleolar targets such as NPM [17]. The exclusion of SIRT7 from the nucleolus seems to represent a mechanism that prevents hyper-activation of nucleolar SIRT7 targets. Notwithstanding, the exit of SIRT7 from the nucleolus results in the hyperacetylation of other nucleolar proteins and consequent modulation of their functions, which may occur during a late phase of the NSR [36]. Furthermore, relocation of SIRT7 into other cellular compartments is instrumental for rapid activation of extra-nucleolar functions of SIRT7.

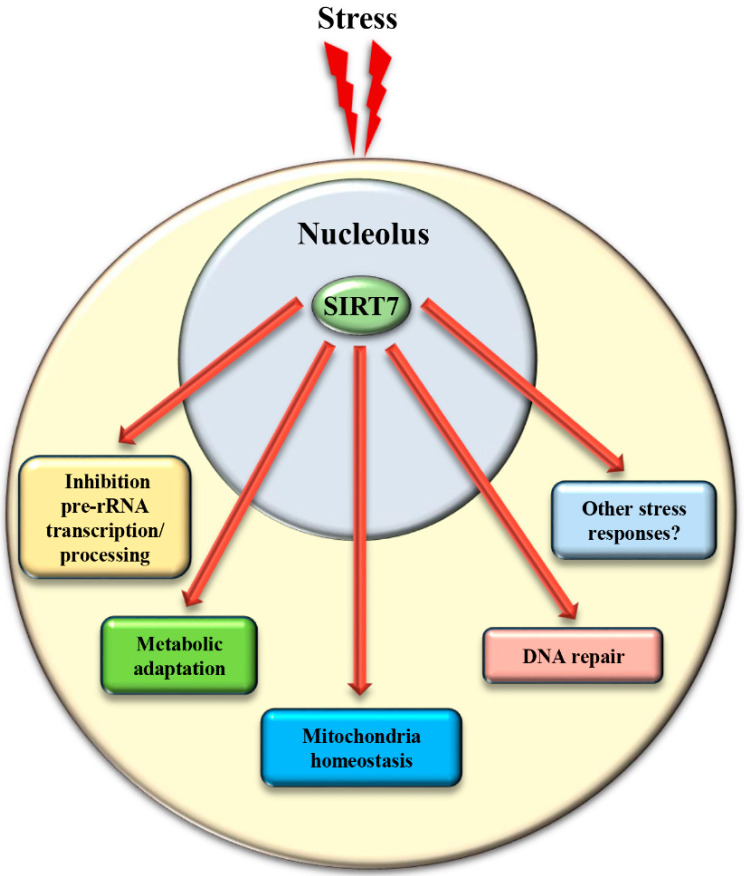

Biosynthesis of ribosomes is the most highly energy-demanding process that takes place in the cell. Thus, adaptation of this process to nutrient availability is fundamental to prevent unnecessary energy expenditure and to ensure maintenance of cellular homeostasis and survival. [50]. The inability to adapt ribosome biogenesis to external cues has been proposed as a critical mechanism that facilitates ageing in different organisms [46]. In lower eukaryotes, sirtuins play a critical role in rDNA silencing following nutrient starvation [46], while the nuclear sirtuins SIRT1 and SIRT7 play opposite roles in this process in mammals. As mentioned above, SIRT1 is a component of the e-NOSC complex: e-NOSC senses elevated NAD+ levels induced by nutrient deprivation through the activation of SIRT1, inducing epigenetic silencing of rDNA genes in a SIRT1- and SUV39H1-dependent manner [50]. In sharp contrast, SIRT7 stimulates rDNA transcription and its exclusion from nucleoli following nutrient starvation is fundamental to ensure the rapid inhibition of rDNA transcription [36]. The exclusion of SIRT7 from the nucleoli favors hyperacetylation of the RNA Polymerase I subunit PAF53 with subsequent reduction of RNA Pol I recruitment at rRNA genes [28]. In addition, the absence of SIRT7 in the nucleolus reduces pre-rRNA processing due to hyperacetylation of U3–55k [31]. Taken together, SIRT7 employs several mechanisms to reduce ribosomes biogenesis in response to nutrient stress [36] (Figure 4 and Table 1).

Figure 4.

Translocation of SIRT7 from the nucleolus following stress is a critical event to activate SIRT7-regulated extra-nucleolar functions. See text for details.

The mechanisms controlling SIRT7 translocation from the nucleoli following stress stimuli remain poorly characterized. Maintenance of SIRT7 in the nucleoli is strictly correlated to rRNA transcription, since its inhibition excludes SIRT7 from this compartment [27]. Several different pathways inhibit rDNA transcription in response to stress. Thus, the reduction of rRNA expression itself may cause exclusion of SIRT7 from nucleoli, which will further reinforce transcriptional inhibition, robustly preventing ribosome biogenesis. Post-translational modifications also control the subcellular localization of SIRT7. The phosphorylation of SIRT7 by AMPK (5’ adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase), a key molecule for restoring cellular energy levels, favors exclusion of SIRT7 from nucleoli, resulting in dramatic downregulation of rDNA transcription and energy saving following glucose starvation [66]. SIRT7 is also phosphorylated by the kinase ATR following genotoxic stress, although the effect of this post-translational modification on the subcellular distribution of SIRT7 and its contribution to rRNA transcription was not determined [17]. The complex network employed to efficiently exclude SIRT7 from the nucleolus has been only partially characterized, despite its paramount importance for inhibiting rDNA transcription and regulating other cellular functions (Figure 4 and Table 1).

3. SIRT7 Controls Extra-Nucleolar Functions to Ensure Cellular Integrity Following Stress

In addition to the control of critical nucleolar functions, SIRT7 is involved in numerous cellular reactions that take place outside this compartment. We assume that the nucleolus acts as a reservoir of SIRT7 and ensures its rapid mobilization following stress to achieve a robust activation of SIRT7-mediated extra-nucleolar functions. For instance, SIRT7 controls the activation of a transcriptional program that facilitates adaptation to starvation. This process requires auto-mono-ADP ribosylation of SIRT7. Auto-modified SIRT7 binds to the histone variant mH2A1.1, which binds mono-ADP-ribose. Thereby, SIRT7 is recruited to intragenic regions where it controls expression of nearby genes by modulating chromatin organization [1]. SIRT7 is also involved in maintaining mitochondria homeostasis. Mitochondria are organelles responsible for cellular energy generation through the biosynthesis of ATP but also control other cellular activities. Dysregulation of mitochondrial homeostasis has been implicated in the development of numerous human diseases including ageing. Moreover, the adaptation of mitochondrial functions in response to nutrient deprivation is imperative for the maintenance of cellular homeostasis and to ensure cell survival [67]. Ablation of SIRT7 in mice correlates with the onset of cellular and organismal alterations associated with mitochondrial dysfunctions such as accelerated ageing, deterioration of hematopoietic stem cells, cardiac and hepatic diseases, and age-associated hearing loss [68,69]. SIRT7 employs different mechanisms to control mitochondrial functions. In particular, SIRT7 acts as a potent epigenetic suppressor of nuclear encoded genes responsible for mitochondria biogenesis [69,70] and represses thereby the mitochondrial protein folding stress response (PFSmt). Inhibition of SIRT7 enzymatic activity under physiological conditions through PRMT6-mediated methylation ensures efficient stimulation of mitochondria biogenesis [70]. Following glucose starvation, binding of SIRT7 to PRMT6 is disrupted via a mechanism requiring AMPK-dependent phosphorylation, which stimulates SIRT7-mediated epigenetic repression of target genes leading to inhibition of de novo biosynthesis of mitochondria [70]. In addition, SIRT7-dependent inhibition of the PFSmt ensures cell survival following nutrient deprivation [69]. On the other hand, SIRT7 stimulates expression of genes controlling mitochondrial functions (such as components of the respiratory chain) by activating the transcription factor GABPβ1 through direct deacetylation [68]. Interestingly, this mechanism has been proposed to play a critical role in mitochondrial homeostasis and metabolic adaptation to nutrient starvation [68]. How the opposing functions of SIRT7 for expression of mitochondrial genes orchestrate the global adaptation of mitochondria to nutrient deprivation remains to be further characterized. A potential explanation for the opposing effects of SIRT7 on mitochondria might be that SIRT7 reduces de novo biosynthesis of mitochondria to prevent energy expenditure in response to stress but at the same time stimulates higher ATP production from the already existing mitochondria, thereby guaranteeing an efficient energy supply (Figure 4). Taken together the available data indicate that translocation of SIRT7 from nucleoli contributes to cellular and organismal homeostasis in response to stress induced by nutrient deprivation not only by inhibiting rDNA transcription but also by controlling other pathways and organelles, such as mitochondria.

Different studies demonstrated that SIRT7 acts as a key player in the maintenance of genomic stability following genotoxic stress [4,49,71]. SIRT7 is recruited to sites of DNA damage where it facilitates DNA repair by modulating the chromatin structure through deacetylation of H3K18 and desuccinylation of H3K122 [4,49]. Moreover, SIRT7 binds more efficiently in response to genotoxic stress to the kinase ATM (Ataxia telangiectasia mutated), a key molecule involved in the DNA damage response. Binding of SIRT7 to ATM promotes ATM deacetylation and deactivation, which is a requisite for efficient DNA repair [72]. The exclusion of SIRT7 from the nucleoli as well as modulation of its catalytic activity following genotoxic stress may be an efficient means to promote rapid activation of DNA repair mechanisms and to attenuate oncogenesis [17,65] (Figure 4). Finally, it is worth to mention that SIRT7 has been implicated in the activation of cellular responses to hypoxia and endoplasmic reticulum stress [73,74]. Thus, the translocation of SIRT7 from the nucleolus orchestrates a broad range of adaptive mechanisms to stress to maintain cellular integrity (Figure 4).

4. Conclusions

SIRT7 remains the least characterized member of mammalian sirtuins. However, new experimental evidence supports a critical role of this molecule in the maintenance of genomic stability and global organismal homeostasis. SIRT7 acts as a key anti-ageing molecule by controlling critical functions of the nucleolus such as the stability of rDNA repeats, activation of the nucleolar stress response, and modulation of rDNA transcription. The nucleolus also represents a prominent storage site for SIRT7, ensuring its rapid availability in response to different stressors. Further identification of molecular targets of SIRT7 as well as the mechanisms governing its translocation from the nucleoli might provide a starting point for the developing a new class of anti-ageing and anti-cancer drugs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: T.B. and A.I.; writing—original draft preparation: P.K., S.T., T.B. and A.I.; writing—review and editing: P.K., S.T., T.B. and A.I.; funding acquisition T.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Max Planck Society, the Excellence Initiative “Cardio-pulmonary Institute”, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Collaborative Re-search Center SFB1213 (TP A02 and B02), Klinische Forschungsgruppe 309TP 08, German Center for Cardiovascular Research and European Research Area Network on Cardiovascular Diseases Project CLARIFY.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Simonet N.G., Thackray J.K., Vazquez B.N., Ianni A., Espinosa-Alcantud M., Morales-Sanfrutos J., Hurtado-Bagès S., Sabidó E., Buschbeck M., Tischfield J., et al. SirT7 auto-ADP-ribosylation regulates glucose starvation response through mH2A1. Sci. Adv. 2020;6:eaaz2590. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaz2590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Du J., Zhou Y., Su X., Yu J.J., Khan S., Jiang H., Kim J., Woo J., Choi B.H., He B., et al. Sirt5 Is a NAD-Dependent Protein Lysine Demalonylase and Desuccinylase. Science. 2011;334:806–809. doi: 10.1126/science.1207861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ianni A., Yuan X., Bober E., Braun T. Sirtuins in the Cardiovascular System: Potential Targets in Pediatric Cardiology. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2018;39:983–992. doi: 10.1007/s00246-018-1848-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li L., Shi L., Yang S., Yan R., Zhang D., Yang J., He L., Li W., Yi X., Sun L., et al. SIRT7 is a histone desuccinylase that functionally links to chromatin compaction and genome stability. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:12235. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feldman J.L., Dittenhafer-Reed K., Denu J.M. Sirtuin Catalysis and Regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:42419–42427. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R112.378877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Imai S.-I., Guarente L. It takes two to tango: NAD+ and sirtuins in aging/longevity control. Npj Aging Mech. Dis. 2016;2:16017. doi: 10.1038/npjamd.2016.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kiran S., Chatterjee N., Singh S., Kaul S., Wadhwa R., Ramakrishna G. Intracellular distribution of human SIRT7 and mapping of the nuclear/nucleolar localization signal. FEBS J. 2013;280:3451–3466. doi: 10.1111/febs.12346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bosch-Presegué L., Vaquero A. Sirtuins in stress response: Guardians of the genome. Oncogene. 2013;33:3764–3775. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumari P., Popescu D., Yue S., Bober E., Ianni A., Braun T. Sirt7 inhibits Sirt1-mediated activation of Suv39h1. Cell Cycle. 2018;17:1403–1412. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2018.1486166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ianni A., Kumari P., Tarighi S., Argento F., Fini E., Emmi G., Bettiol A., Braun T., Prisco D., Fiorillo C., et al. An Insight into Giant Cell Arteritis Pathogenesis: Evidence for Oxidative Stress and SIRT1 Downregulation. Antioxidants. 2021;10:885. doi: 10.3390/antiox10060885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Song J., Yang B., Jia X., Li M., Tan W., Ma S., Shi X., Feng L. Distinctive Roles of Sirtuins on Diabetes, Protective or Detrimental? Front. Endocrinol. 2018;9:724. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gallí M., Van Gool F., Leo O. Sirtuins and inflammation: Friends or foes? Biochem. Pharmacol. 2011;81:569–576. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujita Y., Yamashita T. Sirtuins in Neuroendocrine Regulation and Neurological Diseases. Front. Neurosci. 2018;12:778. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chalkiadaki A., Guarente L. The multifaceted functions of sirtuins in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2015;15:608–624. doi: 10.1038/nrc3985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson R.M., Weindruch R. The caloric restriction paradigm: Implications for healthy human aging. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2012;24:101–106. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.22243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guarente L.P. Calorie restriction and sirtuins revisited. Genes Dev. 2013;27:2072–2085. doi: 10.1101/gad.227439.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ianni A., Kumari P., Tarighi S., Simonet N.G., Popescu D., Guenther S., Hölper S., Schmidt A., Smolka C., Yue S., et al. SIRT7-dependent deacetylation of NPM promotes p53 stabilization following UV-induced genotoxic stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2021;118:e2015339118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2015339118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flick F., Lüscher B. Regulation of Sirtuin Function by Posttranslational Modifications. Front. Pharmacol. 2012;3:29. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2012.00029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalous K.S., Wynia-Smith S., Olp M.D., Smith B.C. Mechanism of Sirt1 NAD+-dependent Protein Deacetylase Inhibition by Cysteine S-Nitrosation. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:25398–25410. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.754655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fang J., Ianni A., Smolka C., Vakhrusheva O., Nolte H., Krüger M., Wietelmann A., Simonet N., Adrian-Segarra J.M., Vaquero A., et al. Sirt7 promotes adipogenesis in the mouse by inhibiting autocatalytic activation of Sirt1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:E8352–E8361. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1706945114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malik S., Villanova L., Tanaka S., Aonuma M., Roy N., Berber E., Pollack J.R., Michishita-Kioi E., Chua K.F. SIRT7 inactivation reverses metastatic phenotypes in epithelial and mesenchymal tumors. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:9841. doi: 10.1038/srep09841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ianni A., Hoelper S., Krueger M., Braun T., Bober E. Sirt7 stabilizes rDNA heterochromatin through recruitment of DNMT1 and Sirt1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017;492:434–440. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.08.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meng F., Qian M., Peng B., Peng L., Wang X., Zheng K., Liu Z., Tang X., Zhang S., Sun S., et al. Synergy between SIRT1 and SIRT6 helps recognize DNA breaks and potentiates the DNA damage response and repair in humans and mice. eLife. 2020;9:e55828. doi: 10.7554/eLife.55828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mélèse T., Xue Z. The nucleolus: An organelle formed by the act of building a ribosome. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1995;7:319–324. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(95)80085-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pelletier J., Thomas G., Volarević S. Ribosome biogenesis in cancer: New players and therapeutic avenues. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2018;18:51–63. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boisvert F.-M., Van Koningsbruggen S., Navascués J., Lamond A. The multifunctional nucleolus. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:574–585. doi: 10.1038/nrm2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ford E., Voit R., Liszt G., Magin C., Grummt I., Guarente L. Mammalian Sir2 homolog SIRT7 is an activator of RNA polymerase I transcription. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1075–1080. doi: 10.1101/gad.1399706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen S., Seiler J., Santiago-Reichelt M., Felbel K., Grummt I., Voit R. Repression of RNA Polymerase I upon Stress Is Caused by Inhibition of RNA-Dependent Deacetylation of PAF53 by SIRT7. Mol. Cell. 2013;52:303–313. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iyer-Bierhoff A., Krogh N., Tessarz P., Ruppert T., Nielsen H., Grummt I. SIRT7-Dependent Deacetylation of Fibrillarin Controls Histone H2A Methylation and rRNA Synthesis during the Cell Cycle. Cell Rep. 2018;25:2946–2954. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grob A., Roussel P., Wright J.E., McStay B., Hernandez-Verdun D., Sirri V. Involvement of SIRT7 in resumption of rDNA transcription at the exit from mitosis. J. Cell Sci. 2009;122:489–498. doi: 10.1242/jcs.042382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen S., Blank M.F., Iyer A., Huang B., Wang L., Grummt I., Voit R. SIRT7-dependent deacetylation of the U3-55k protein controls pre-rRNA processing. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:10734. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barber M., Michishita-Kioi E., Xi Y., Tasselli L., Kioi M., Moqtaderi Z., Tennen R.I., Paredes S., Young N., Chen K., et al. SIRT7 links H3K18 deacetylation to maintenance of oncogenic transformation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012;487:114–118. doi: 10.1038/nature11043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pandey V., Kumar V. Stabilization of SIRT7 deacetylase by viral oncoprotein HBx leads to inhibition of growth restrictive RPS7 gene and facilitates cellular transformation. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:14806. doi: 10.1038/srep14806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsai Y.-C., Greco T., Cristea I.M. Sirtuin 7 Plays a Role in Ribosome Biogenesis and Protein Synthesis. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2014;13:73–83. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.031377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu D., Li Y., Zhu K.S., Wang H., Zhu W.-G. Advances in Cellular Characterization of the Sirtuin Isoform, SIRT7. Front. Endocrinol. 2018;9:652. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blank M.F., Grummt I. The seven faces of SIRT7. Transcription. 2017;8:67–74. doi: 10.1080/21541264.2016.1276658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stochaj U., Weber S.C. Nucleolar Organization and Functions in Health and Disease. Cells. 2020;9:526. doi: 10.3390/cells9030526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lindström M.S., Jurada D., Bursac S., Oršolić I., Bartek J., Volarevic S. Nucleolus as an emerging hub in maintenance of genome stability and cancer pathogenesis. Oncogene. 2018;37:2351–2366. doi: 10.1038/s41388-017-0121-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McStay B., Grummt I. The Epigenetics of rRNA Genes: From Molecular to Chromosome Biology. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2008;24:131–157. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.24.110707.175259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tsekrekou M., Stratigi K., Chatzinikolaou G. The Nucleolus: In Genome Maintenance and Repair. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18:1411. doi: 10.3390/ijms18071411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sinclair D., Guarente L. Extrachromosomal rDNA Circles—A Cause of Aging in Yeast. Cell. 1997;91:1033–1042. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80493-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ganley A., Ide S., Saka K., Kobayashi T. The Effect of Replication Initiation on Gene Amplification in the rDNA and Its Relationship to Aging. Mol. Cell. 2009;35:683–693. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ide S., Miyazaki T., Maki H., Kobayashi T. Abundance of Ribosomal RNA Gene Copies Maintains Genome Integrity. Science. 2010;327:693–696. doi: 10.1126/science.1179044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zafiropoulos A., Tsentelierou E., Linardakis M., Kafatos A., Spandidos D. Preferential loss of 5S and 28S rDNA genes in human adipose tissue during ageing. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2005;37:409–415. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ren R., Deng L., Xue Y., Suzuki K., Zhang W., Yu Y., Wu J., Sun L., Gong X., Luan H., et al. Visualization of aging-associated chromatin alterations with an engineered TALE system. Cell Res. 2017;27:483–504. doi: 10.1038/cr.2017.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tiku V., Antebi A. Nucleolar Function in Lifespan Regulation. Trends Cell Biol. 2018;28:662–672. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2018.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Paredes S., Angulo-Ibanez M., Tasselli L., Carlson S.M., Zheng W., Li T.-M., Chua K.F. The epigenetic regulator SIRT7 guards against mammalian cellular senescence induced by ribosomal DNA instability. J. Biol. Chem. 2018;293:11242–11250. doi: 10.1074/jbc.AC118.003325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vakhrusheva O., Smolka C., Gajawada P., Kostin S., Boettger T., Kubin T., Braun T., Bober E. Sirt7 Increases Stress Resistance of Cardiomyocytes and Prevents Apoptosis and Inflammatory Cardiomyopathy in Mice. Circ. Res. 2008;102:703–710. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.164558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vazquez B.N., Thackray J., Simonet N., Kane-Goldsmith N., Martinez-Redondo P., Nguyen T., Bunting S., Vaquero A., Tischfield J., Serrano L. SIRT7 promotes genome integrity and modulates non-homologous end joining DNA repair. EMBO J. 2016;35:1488–1503. doi: 10.15252/embj.201593499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Murayama A., Ohmori K., Fujimura A., Minami H., Yasuzawa-Tanaka K., Kuroda T., Oie S., Daitoku H., Okuwaki M., Nagata K., et al. Epigenetic Control of rDNA Loci in Response to Intracellular Energy Status. Cell. 2008;133:627–639. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Peng J., Karpen G.H. H3K9 methylation and RNA interference regulate nucleolar organization and repeated DNA stability. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006;9:25–35. doi: 10.1038/ncb1514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Riesen M., Morgan A. Calorie restriction reduces rDNA recombination independently of rDNA silencing. Aging Cell. 2009;8:624–632. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00514.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Song C., Hotz-Wagenblatt A., Voit R., Grummt I. SIRT7 and the DEAD-box helicase DDX21 cooperate to resolve genomic R loops and safeguard genome stability. Genes Dev. 2017;31:1370–1381. doi: 10.1101/gad.300624.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhou H., Li L., Wang Q., Hu Y., Zhao W., Gautam M., Li L. H3K9 Demethylation-Induced R-Loop Accumulation Is Linked to Disorganized Nucleoli. Front. Genet. 2020;11:43. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2020.00043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pfister A.S. Emerging Role of the Nucleolar Stress Response in Autophagy. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2019;13:156. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2019.00156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang K., Yang J., Yi J. Nucleolar Stress: Hallmarks, sensing mechanism and diseases. Cell Stress. 2018;2:125–140. doi: 10.15698/cst2018.06.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.James A., Wang Y., Raje H., Rosby R., DiMario P. Nucleolar stress with and without p53. Nucleus. 2014;5:402–426. doi: 10.4161/nucl.32235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Boulon S., Westman B.J., Hutten S., Boisvert F.-M., Lamond A.I. The Nucleolus under Stress. Mol. Cell. 2010;40:216–227. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lu Y.-F., Xu X.-P., Zhu Q., Liu G., Bao Y.-T., Wen H., Li Y.-L., Gu W., Zhu W.-G. SIRT7 activates p53 by enhancing PCAF-mediated MDM2 degradation to arrest the cell cycle. Oncogene. 2020;39:4650–4665. doi: 10.1038/s41388-020-1305-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kumari P., Tarighi S., Braun T., Ianni A. The complex role of SIRT7 in p53 stabilization: Nucleophosmin joins the debate. Mol. Cell. Oncol. 2021;8:1896349. doi: 10.1080/23723556.2021.1896349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sun M., Zhai M., Zhang N., Wang R., Liang H., Han Q., Jia Y., Jiao L. MicroRNA-148b-3p is involved in regulating hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced injury of cardiomyocytes in vitro through modulating SIRT7/p53 signaling. Chem. Interact. 2018;296:211–219. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2018.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhao J., Wozniak A., Adams A., Cox J., Vittal A., Voss J., Bridges B., Weinman S.A., Li Z. SIRT7 regulates hepatocellular carcinoma response to therapy by altering the p53-dependent cell death pathway. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019;38:252. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1246-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Michishita E., Park J.Y., Burneskis J.M., Barrett J.C., Horikawa I. Evolutionarily Conserved and Nonconserved Cellular Localizations and Functions of Human SIRT Proteins. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2005;16:4623–4635. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e05-01-0033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Carotenuto P., Pecoraro A., Palma G., Russo G., Russo A. Therapeutic Approaches Targeting Nucleolus in Cancer. Cells. 2019;8:1090. doi: 10.3390/cells8091090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kiran S., Oddi V., Ramakrishna G. Sirtuin 7 promotes cellular survival following genomic stress by attenuation of DNA damage, SAPK activation and p53 response. Exp. Cell Res. 2015;331:123–141. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sun L., Fan G., Shan P., Qiu X., Dong S., Liao L., Yu C., Wang T., Gu X., Li Q., et al. Regulation of energy homeostasis by the ubiquitin-independent REGγ proteasome. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:12497. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liesa M., Shirihai O.S. Mitochondrial Dynamics in the Regulation of Nutrient Utilization and Energy Expenditure. Cell Metab. 2013;17:491–506. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ryu D., Jo Y.S., Lo Sasso G., Stein S., Zhang H., Perino A., Lee J.U., Zeviani M., Romand R., Hottiger M.O., et al. A SIRT7-Dependent Acetylation Switch of GABPβ1 Controls Mitochondrial Function. Cell Metab. 2014;20:856–869. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mohrin M., Shin J., Liu Y., Brown K., Luo H., Xi Y., Haynes C.M., Chen D. A mitochondrial UPR-mediated metabolic checkpoint regulates hematopoietic stem cell aging. Science. 2015;347:1374–1377. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa2361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yan W.-W., Liang Y.-L., Zhang Q.-X., Wang D., Lei M.-Z., Qu J., He X.-H., Lei Q.-Y., Wang Y.-P. Arginine methylation of SIRT7 couples glucose sensing with mitochondria biogenesis. EMBO Rep. 2018;19:e46377. doi: 10.15252/embr.201846377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mao Z., Hine C., Tian X., Van Meter M., Au M., Vaidya A., Seluanov A., Gorbunova V. SIRT6 Promotes DNA Repair Under Stress by Activating PARP1. Science. 2011;332:1443–1446. doi: 10.1126/science.1202723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tang M., Li Z., Zhang C., Lu X., Tu B., Cao Z., Li Y., Chen Y., Jiang L., Wang H., et al. SIRT7-mediated ATM deacetylation is essential for its deactivation and DNA damage repair. Sci. Adv. 2019;5:eaav1118. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aav1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hubbi M., Hu H., Kshitiz, Gilkes D.M., Semenza G.L. Sirtuin-7 Inhibits the Activity of Hypoxia-inducible Factors. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:20768–20775. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.476903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shin J., He M., Liu Y., Paredes S., Villanova L., Brown K., Qiu X., Nabavi N., Mohrin M., Wojnoonski K., et al. SIRT7 Represses Myc Activity to Suppress ER Stress and Prevent Fatty Liver Disease. Cell Rep. 2013;5:654–665. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]