Abstract

The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of fecal ESBL-producing Escherichia coli (E. coli) in pigs on large and small farms in Latvia, to characterize beta-lactamase genes and establish an antimicrobial resistance profile. Fecal samples (n = 615) were collected from 4-week, 5-week, 6-week, 8-week, 12-week and 20-week-old piglets, pigs and sows on four large farms (L1, L2, L3, L4) and three small farms (S1, S2, S3) in Latvia. ChromArt ESBL agar and combination disc tests were used for the screening and confirmation of ESBL-producing E. coli. The antimicrobial resistance was determined by the disc diffusion method and ESBL genes were determined by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Subsequently, ESBL-producing E. coli was confirmed on three large farms, L1 (64.3%), L2 (29.9%), L3 (10.7%) and one small farm, S1 (47.5%); n = 144 (23.4%). The prevalence of ESBL-producing E. coli differed considerably between the large and small farm groups (26.9% vs. 12.7%). Of ESBL E. coli isolates, 96% were multidrug-resistant (MDR), demonstrating there were more extensive MDR phenotypes on large farms. The distribution of ESBL genes was blaTEM (94%), blaCTX-M (86%) and blaSHV (48%). On the small farm, blaSHV dominated, thus demonstrating a positive association with resistance to amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, ceftazidime and cefixime, while on the large farms, blaCTX-M with a positive association to cephalexin and several non-beta lactam antibiotics dominated. The results indicated the prevalence of a broad variety of ESBL-producing E. coli among the small and large farms, putting the larger farms at a higher risk. Individual monitoring of ESBL and their antimicrobial resistance could be an important step in revealing hazardous MDR ESBL-producing E. coli strains and reviewing the management of antibiotic use.

Keywords: ESBL, pig farming, multidrug-resistant, CTX-M, SHV, TEM

1. Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance is one of the major global public health concerns currently facing humanity. The alarming situation has been exacerbated by the fact that the “pipeline of new antibiotics is dry”. In Europe, an estimated 70% of antibiotics are used in the animal sector, thus increasing the interest in antibiotic consumption in this sector [1]. According to global trends in antibiotic use for food animals, the highest consumption of antimicrobials per kilogram of an animal is in pigs, compared to chickens and cattle [2]. In high-income countries, intensive pig production dominates and pigs are generally kept in indoor systems in which there is limited space, few opportunities to express natural behaviors, and many stressors such as weaning, moving, mixing, surgical procedures, and environmental conditions that increase the risk of production diseases and infections. Digestive problems in early-weaned piglets is the main reason why piglets receive antibiotics around weaning and post-weaning periods [3]. Most of the antibiotics used in pigs are the same or belong to the same classes as those used in human medicine [4]. According to a report from the European Medicines Agency, tetracycline and beta-lactam antibiotics are the most sold antibiotics for food-producing animals in European countries [5,6]. Moreover, extended-spectrum penicillin accounts for the major proportion of penicillin subclasses [5]. The intensive use and misuse of beta-lactam antibiotics, which are critically important in human medicine, has resulted in the spread of extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing bacteria in pigs. ESBLs are able to confer resistance to penicillin, first-, second-, and third-generation cephalosporin, and monobactam. Most ESBL genes are located in the mobile genetic elements; therefore, horizontal gene transfer has promoted the spread of antibiotic resistance genes among strains and species [7]. In addition, ESBL-producing Escherichia coli (E. coli) has often been found to be co-resistant to other antibiotic classes [8]. According to WHO, ESBL-producing bacteria are one of the most serious and critical global threats of the 21st century [9].

On the one hand, programs for routine monitoring of antimicrobial resistance have disclosed a low prevalence of ESBL producers among indicator E. coli from pigs in Europe, including Latvia; on the other hand, specific monitoring programs have used selective media and disclosed a highly varying prevalence of presumptive ESBL producers—from very low to extremely high, depending on the reporting country [4,10,11]. In Latvia, the prevalence of ESBL-producing E. coli has been reported as high, which is also the European average level [4]. This alarming level for the prevalence of ESBL producers calls for further examination of the situation. Large farms with high numbers of pigs may have a higher probability of infection and production diseases, which can lead to an increase in antibiotic treatment [12]. Furthermore, the availability and administration of antimicrobials can differ depending on the farm size and this may have an impact on the development of resistance genes [13]. To limit the spread of ESBL-producing E. coli, it is important to determine the presence of ESBL in large and small farms, and to consider the prevalence level in pigs at different ages. There is a lack of information on differences in resistant genes and phenotypic resistance in large and small farms in Latvia. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of fecal ESBL-producing E. coli in pigs on large and small farms; to determine the distribution of the CTX-M, TEM, and SHV genotype in ESBL-producing E. coli isolates, and to characterize the antimicrobial resistance profile in pigs from Latvia.

2. Results

2.1. Prevalence of ESBL-Producing E. coli

Out of seven pig farms, the presence of fecal ESBL-producing E. coli was confirmed on four farms (L1, L2, L3 and S1; n = 144 (23.4%)). Among the large farms, the highest prevalence of ESBL-producing E. coli was observed on Farm L1 (64.3%), while among the small farms the prevalence on Farm S1 was 47.5%. The prevalence of ESBL-producing E. coli differed significantly between the large and small farm groups (26.9% vs. 12.7%, p = 0.029). Moreover, a notable difference (p < 0.05) was found between the large and small farms (Table 1).

Table 1.

Prevalence of ESBL-producing E. coli on pig farms.

| Site | Positive | |

|---|---|---|

| Presence of ESBL-producing E. coli on large and small pig farms, (%) | ||

| Large farms (n = 465) |

L1 (n = 115) | 74 (64.3) c |

| L2 (n = 127) | 38 (29.9) b | |

| L3 (n = 121) | 13 (10.7) a | |

| L4 (n = 102) | 0 | |

| Small farms (n = 150) |

S1 (n = 40) | 19 (47.5) c |

| S3 (n = 41) | 0 | |

| S2 (n = 69) | 0 | |

| Presence of ESBL-producing E. coli in pigs of different age, (%) | ||

| Weeks of age (n = 538) |

4 (n = 110) | 31 (28.2) b |

| 6 (n = 151) | 53 (35.1) b | |

| 8 (n = 105) | 11 (10.5) a | |

| 12 (n = 87) | 10 (11.5) a | |

| 20 (n = 85) | 7 (8.2) a | |

| Sows (n = 77) | 32 (41.6) b | |

a,b,c—mean values in the same column with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05).

Comparing the prevalence of fecal ESBL-producing E. coli in pigs of different ages, the presence of ESBL-producing E. coli was significantly higher in 4-week and 6-week-old piglets (28.2% and 35.1%, respectively) and in sows (41.6%), while the lowest prevalence of ESBL-producing E. coli was observed in pigs at 20 weeks (8.2%) (Table 1).

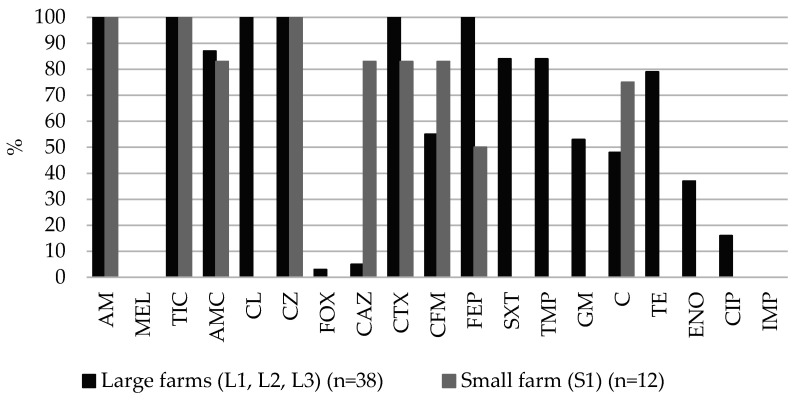

2.2. Resistance of ESBL-Producing E. coli Isolates Tested

On both the large and small farms, all of the ESBL-producing E. coli isolates (n = 50) were resistant to ampicillin, ticarcillin and cefazolin. On the large farms, the highest resistance of ESBL-producing E. coli was to cefalexin (100%), cefotaxime (100%), cefepime (100%), followed by amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (87%), trimethoprim (84%), sulfametaxazole-trimethoprim (84%), tetracycline (79%) and gentamicin (53%). On the small farm (S1), ESBL-producing E. coli was highly resistant to ceftazidime (83%), cefotaxime (83%), cefixime (83%), followed by chloramphenicol (75%) and cefepime (50%) (Figure 1). A statistically significant difference (p < 0.05) was found between the prevalence of resistance percentages of the large and small farms. On the large farms, there was higher (p < 0.05) resistance to cefalexin, cefepime, trimethoprim, sulfametaxazole-trimetoprim, gentamicin, tetracycline and enrofloxacin, while on the small farm (S1) there was higher resistance to ceftazidime. None of the tested ESBL-producing E. coli isolates were resistant to mecillinam and imipenem.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of resistance in fecal ESBL-producing E. coli isolates from pigs on large and small farms. AM–ampicillin, MEL–mecillinam, TIC–ticarcillin, AMC–amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, CL–cefalexin, CZ–cefazolin, FOX–cefoxitin, CAZ–ceftazidime, CTX–cefotaxime, CFM–cefixime, FEP–cefepime, SXT–sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, TMP–trimethoprim, GM–gentamicin, C–chloramphenicol, TE–tetracycline, ENO–enrofloxacin, CIP–ciprofloxacin, IMP–imipenem.

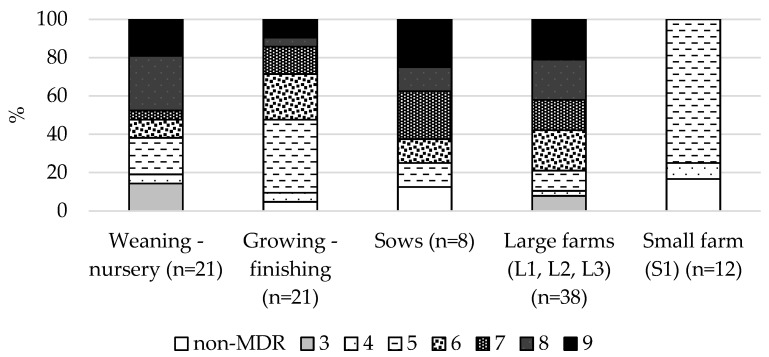

Forty-eight of 50 (96%) fecal ESBL-producing E. coli isolates were classified as MDR according to Magiorakos et al., [14]. In a large proportion of the weaning-nursery piglets (47.6%) and sows (37.5%), ESBL-producing E. coli isolates were resistant to eight or more different antimicrobial categories, while there were less in the growing-finishing pigs (14.2%). ESBL-producing E. coli isolates from the large farms demonstrated more extensive MDR phenotypes; 79.0% of isolates were resistant to six or more antimicrobials. However, on the small farm (S1), 75.0% of ESBL-producing E. coli isolates were classified as MDR5, at the same time, none of them were resistant to six or more antimicrobials. Furthermore, 16.7% of ESBL-producing E. coli isolates were classified as non-MRD (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Proportion of different levels of MRD in 50 ESBL-producing E. coli isolates from pigs of different age stages and farms of different sizes.

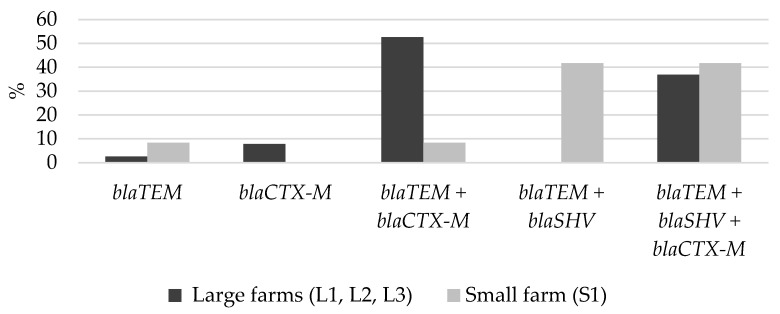

2.3. Distribution of Beta-Lactamase Gene(s) in ESBL-Producing E. coli

All the phenotypic confirmed fecal ESBL-producing E. coli isolates were confirmed genetically, and at least one ESBL gene was detected. The most frequently detected beta-lactamase gene in ESBL-producing E. coli isolates was blaTEM (94%, n = 47), followed by blaCTX-M (86%, n = 43) and blaSHV (48%, n = 24). In the pig population, the most prevalent beta-lactamase genes were blaTEM + blaCTX-M in combination (42%, n = 21), followed by the combination of all three genes: blaTEM + blaSHV + blaCTX-M (38%, n = 19).

The distribution of beta-lactamase gene(s) on the large and small farms was different. On the small farm (S1), the blaSHV combination with other beta-lactamase genes was detected considerably more frequently compared to the large farms (83.3% vs. 36.8%, p = 0.007), while blaCTX-M alone, or in combination with other beta-lactamase genes, was more frequently detected on the large farms compared to the small one (97.4% vs. 50.0%, p < 0.001). On the large farms, the most prevalent beta-lactamase genes were blaTEM + blaCTX-M (52.6%, n = 20), compared to blaTEM + blaSHV (41.7%, n= 5) on the small farm (S1) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Distribution of beta-lactamase gene(s) on the large and small farms.

2.4. Associations of Beta-Lactamase Gene(s) to Phenotypic Antimicrobial

The phenotype of AM-TIC-AMC-CL-CZ-CTX-CFM-FEP was the most commonly observed pattern of resistance to beta-lactams on the large farms (Table 2). This pattern most often contained all three beta-lactamase genes blaTEM + blaSHV + blaCTX-M (52.9%, n = 9) or the combination of blaTEM + blaCTX-M (35, 3%, n = 6). The next most common phenotype that was observed was similar to the one above, but without resistance to cefixime. The phenotypes of AM-TIC-AMC-CZ-CAZ-CTX-CFM-FEP and AM-TIC-AMC-CZ-CAZ-CTX-CFM were the most commonly observed patterns on the small farm (S1). Interestingly, the phenotype AM-TIC-CZ was observed in two cases, one of these contained the blaTEM gene, while the other contained blaTEM + blaSHV + blaCTX-M.

Table 2.

Occurrence of pattern for resistance to beta lactams antibiotics and beta-lactamase gene(s) detected in ESBL-producing E. coli. Note: AM–ampicillin, TIC–ticarcillin, AMC–amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, CL–cefalexin, CZ–cefazolin, FOX–cefoxitin, CAZ–ceftazidime, CTX–cefotaxime, CFM–cefixime, FEP–cefepime.

| Patterns of Resistance to Beta-lactams | Number of Beta-lactamase Gene(s) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| bla CTX-M | bla SHV | bla TEM | blaTEM+ blaSHV |

bla

TEM+

bla CTX-M |

blaTEM+ blaSHV+ blaCTX-M | Total | |

| Large farms (L1, L2, L3) | |||||||

| AM-TIC-AMC-CL-CZ-CAZ-CTX-CFM-FEP | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| AM-TIC-AMC-CL-CZ-CTX-CFM-FEP | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 9 | 17 |

| AM-TIC-AMC-CL-CZ-CTX-FEP | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 4 | 13 |

| AM-TIC-AMC-CL-CZ-FOX-CTX-CFM-FEP | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| AM-TIC-CL-CZ-CTX-CFM-FEP | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| AM-TIC-CL-CZ-CTX-FEP | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Small farm (S1) | |||||||

| AM-TIC-AMC-CZ-CAZ-CTX-CFM | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 4 |

| AM-TIC-AMC-CZ-CAZ-CTX-CFM-FEP | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| AM-TIC-CZ | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 3 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 21 | 19 | 50 |

The presence of blaSHV demonstrated a positive association with resistance to amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (OR = 6.79, 95% CI 1.39–66.10, p = 0.0083), ceftazidime (OR = 8.38, 95% CI 2.47–37.17; p = 0.0001) and cefixime (OR = 4.36, 95% CI 1.70–12.00; p = 0.0009). The presence of blaCTX-M was positively associated with resistance to cefalexin (OR = 34.86, 95% CI 6.63–357.80; p = 0.0001). Furthermore, the presence of blaCTX-M was positively associated (p < 0.05) with resistance to non-beta-lactam antibiotics—sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, trimethoprim, gentamicin, tetracycline and enrofloxacin (Table 3). No statistically significant association between the presence of blaTEM and resistance to the antibiotics was observed.

Table 3.

Statistically significant associations between β-lactamase gene and antimicrobial resistance in ESBL-producing E. coli isolates.

| Selected Beta-Lactamase Gene | Antibiotic | OR | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| bla SHV | AMC | 6.79 | 1.39–66.10 | 0.0083 |

| CL | 0.12 | 0.03–0.41 | 0.0001 | |

| CAZ | 8.38 | 2.47–37.17 | 0.0001 | |

| CFM | 4.36 | 1.70–12.00 | 0.0009 | |

| FEP | 0.15 | 0.01–0.79 | 0.0124 | |

| SXT | 0.30 | 0.12–0.77 | 0.0067 | |

| TMP | 0.30 | 0.12–0.77 | 0.0067 | |

| bla CTX-M | CL | 34.86 | 6.63–357.80 | 0.0001 |

| CTX | 6.77 | 0.45–101.68 | 0.0931 | |

| CAZ | 0.08 | 0.01–0.33 | 0.0001 | |

| SXT | 15.03 | 3.02–148.12 | 0.0001 | |

| TMP | 15.03 | 3.02–148.12 | 0.0001 | |

| GM | inf | 2.90–inf | 0.0003 | |

| TE | 12.11 | 2.45–118.82 | 0.0003 | |

| ENO | inf | 1.46–inf | 0.0093 |

3. Discussion

According to the program set up to monitor AMR in the EU Member states, the prevalence of the ESBL indicator E. coli was reported to be low (1.4%) in fecal samples from fattening pigs at slaughter. However, the specific monitoring program with supplementary testing discovered a high prevalence of presumptive ESBL-producing E. coli in the samples of fattening pigs (34.3%). It should be noted that the level of prevalence varies greatly (0.3–80.3%) among the EU countries [4]. In our study, the prevalence of ESBL-producing E. coli in pigs decreased during the period of growing and fattening. The highest amount of ESBL-producing E. coli was present in sows (41.6%), followed by weaned piglets (35.1%), and was much lower in fattening pigs (8.2%). It was previously reported that ESBL-producing E. coli carriage considerably decreases over the production cycle of pigs [15,16]. Interestingly, in the above study by the monitoring program of the EU, a much higher prevalence of ESBL-producing E. coli in fattening pigs was reported in Latvia, where the prevalence was 42.3% [4] in comparison with our results. One of the reasons could be the differences in the ESBL screening method. The method employed by us did not include a non-selective pre-enrichment step, which could affect the sensitivity of the method. A research study from Germany has shown that by including the enrichment procedure, ESBL-producing E. coli could be isolated twice as often [17]. In addition, a German study reported that during the transportation and the waiting period at the slaughterhouse, the probability of transmission of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriacae among pigs increased to nearly 30% [18]. In our study, samples were obtained on farms; thus, the testing method could result in a higher prevalence of ESBL-producing E. coli.

Our results demonstrated that farm size could be one of the risk factors for an increased occurrence of ESBL-producing E. coli. At the same time, this conclusion should be treated with caution, because farms with the highest prevalence represented both sizes: large (L1) and small (S1). It is more important to highlight the considerable differences observed on farms in general. Several studies on the risk factors of increased prevalence of ESBL-producing E. coli on pig farms have been carried out. The use of private water sources for pigs, lack of well-organized biosecurity (entrance hygiene, pest control, presence of pets, etc.) and hygiene (disinfection, detergent use), the high use of antibiotics in pig production, and in particular, the recent use of cephalosporins [19,20] are serious risk factors. Although our study did not include a detailed evaluation of risk factors for the spread of ESBL-producing E. coli due to the limited number of the farms available for our study, a causal relationship was observed between the increased occurrence of diarrhea and the wide use and misuse of beta-lactam antibiotics in pigs, resulting in an increased prevalence of ESBL. Based on the survey data, on farms L1 and S1, diarrhea in piglets of different ages has been a common problem for a long time; moreover, overuse of amoxicillin and enrofloxacin could be responsible for the selection of ESBL-producing bacteria. Amoxicillin is usually added to feed, but as it has low absorption and bioavailability [21], it creates high selective pressure on gut microbiota, which can promote antibiotic resistance [22]. A correlation between the use of beta-lactam antibiotics (amoxicillin) and the high prevalence rate of ESBL producers was also reported in another study [23]. In contrast, on the sampled two small farms (S2 and S3) and on one large farm (Farm L4), diarrhea was rarely observed. On Farms S2 and S3, antibiotics, and non-beta lactam antibiotics, were used rarely; a similar situation was observed on Farm L4, where antibiotics from the broad-spectrum penicillin group were only used sporadically. The role of fluoroquinolone in increasing the spread of ESBL has also been confirmed [24].

The phenotypic detection of antimicrobial resistance in ESBL-producing E. coli revealed significant differences in resistance between isolates from the large and small farms. With regard to beta-lactam antibiotics, the resistance to cephalexin, cefotaxime and cefepime was more commonly observed in pigs from the large farms, while resistance to ceftazidime was found in pigs from the small farm. Furthermore, resistance to the non-beta lactam antibiotics: trimethoprim, sulfametaxazole-trimetoprim, gentamicin, tetracycline, enrofloxacin was observed only in isolates obtained from the large farms. Phenotypic differences in resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics were discovered by the presence of different beta-lactamases coding genes. As known, ESBL-producing bacteria produce ESBLs enzymes that hydrolyze most third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins, thus explaining the observation of the high prevalence of resistance to cefotaxime (100%) and cefepime (100%). At the same time, a high prevalence of resistance to amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (87%) was observed in fecal ESBL-producing E. coli isolates. One of reasons for this phenomenon could be the production of OXA-1 beta lactamase [25]. Further investigations are needed to confirm this; in addition, this could also be due to the hyperproduction of target beta-lactamases or relative permeability [26]. Extended-spectrum SHV and TEM beta-lactamases show higher levels of hydrolytic activity for ceftazidime than cefotaxime [27], while a large number of CTX-M beta lactamases show only cefotaxime activity [28]. The co-existence of beta-lactamase genes, especially blaCTX-M, with other genes, was explained by MDR phenotypes [29]. Resistance to mecillinam and imipenem was not observed in our study. Sporadic cases of ESBL-producing E. coli resistance to imipenem (carbapenems) obtained from pigs or pork in the EU have been reported in Germany [4] and Belgium [30]. Mecillinam belongs to the group of broad-spectrum penicillins and historically it has not been widely used in veterinary medicine, possibly due to its poor oral absorption; however, some authors believe that mecillinam has potential in veterinary medicine if administered parenterally [31]. No data are available on the ESBL-producing E. coli resistance to mecillinam in pigs, but several authors have reported the high susceptibility of ESBL-producing E. coli (96.9.2%) and MRD E. coli (96.5%) to mecillinam in humans [32]; therefore, since 2019, mecillinam has been included in category A, which is not authorized for use in veterinary medicine [33].

In contrast to ESBL-producing E. coli on the small farm, all of the ESBL-producing E. coli isolates from pigs on the large farms were classified as MDR; moreover, there were more extensive MDR phenotypes. This is in accordance with another study where these results were positively associated with the farm size, and a higher rate of MDR in E. coli on pig farms was reported [13]. No detailed information on the treatment management on the pig farms was available, but the higher usage of antibiotics in feed or water on the large farms in comparison to parenteral treatment on the small farm could be a credible explanation for higher and more extensive MDR isolates on the large farms. Moreover, the inclusion of zinc oxide as a feed additive could be an important factor in increasing extensive MDR phenotypes. High levels of zinc oxide supplementation may promote antimicrobial resistance and MDR in the pig’s gut [34,35]. In our study, the group of growing-finishing pigs showed a tendency to dominate over narrower phenotypes of MDR. Indeed, narrower phenotypes of MDR in growing-finishing pigs were associated with a decrease in external selection pressure due to considerably reduced or completely discontinued antibiotic use during the fattening period. Several studies have reported a significant reduction in MDR E. coli in finishing pigs than in weaned or suckling pigs [36,37]. A higher prevalence of MDR in weaned piglets is usually explained by the wider use of antibiotics for treatment and prophylaxis because younger animals have an increased risk of enteric infections, especially when stressed by weaning and mixing litters [36]. Sows received antibiotics more often by parenteral administration [38], which would be a positive factor for the spread of resistance, but, at the same time, different types of active ingredients of antimicrobials were chosen more often [39], which could contribute to the high prevalence of MRD bacteria.

Among ESBL-producing E. coli isolates, blaTEM was found to be the most predominant, although it was only 8% more present than blaCTX-M. The distribution of ESBL genes in isolates from food-production animals in Europe has been reported by Silva et al. [6]. In pigs, the most frequently observed blaCTX-M genes were blaCTX-M-1 and blaCTX-M-15 from blaCTX-M-group1. The genes blaCTX-M-group4 and blaCTX-M-group2 were relatively less common with 5% (blaCTX-M-14) and 3% (blaCTX-M-2), respectively [6]. As blaCTX-M-group2 and blaCTX-M-group4 were not identified in our study, the prevalence of the blaCTX–M genes could be slightly higher. A high prevalence of blaCTX-M-group1 and blaTEM in pigs was reported by other authors from diverse European countries, and similarly to our results, the genes blaTEM and blaCTX-M were most commonly observed in combination [40,41,42].

Our results demonstrated the differences in the distribution of beta-lactamase genes on the large and small farms. The gene of blaCTX-M in combination with other beta-lactamase genes were observed considerably more frequently on the large farms, while the gene of blaSHV in combination with other beta lactamase genes was dominant on the small farm. The main reason for the higher prevalence of blaCTX-M on the large farms could be the zinc oxide added to the feed. A recent study showed that the addition of zinc to fecal suspension in vitro increased the proportion of a plasmid-encoded blaCTX-M-1 E. coli compared with the total microbiota. In addition, zinc may induce the expression of resistance genes in the E. coli strains [43]. On the large farms, zinc was probably responsible for the spread of plasmid-encoded ESBL strains and inducing the expression of the blaCTX-M gene. This may explain the characteristic phenotype of blaCTX-M against several beta lactam antibiotics—cefazolin, cephalexin, cefotaxime and cefepime.

We observed a positive association between the gene blaSHV and the resistance of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, ceftazidime and cefixime. However, the gene blaCTX-M had a positive association with the resistance of cephalexin and several non-beta-lactam antibiotics—enrofloxacin, tetracycline, gentamicin, trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim. Some TEM and SHV mutants have a single amino acid change at the amber position, therefore they overtake the first generation (e.g., clavulanic acid) of beta-lactamase inhibitors [44,45]. Other authors have reported the positive association of SHV with resistance to ceftazidime due to the higher hydrolytic activity of SHV against ceftazidime than against cefotaxime, which is attributed to the Glu240 Lys substitution [27]. It has not been clearly defined whether the presence of blaSHV specifically causes resistance to cefixime. Moreover, Naziri at al. [46] have reported a high resistance to cefixime equally often in both isolates that contain blaCTX-M or blaSHV. It should be noted that Livermore at al. [47] reported that the level of resistance to the oral cephalosporin (cefixime) depends on the specific enzyme variant. A high degree of resistance was observed in SHV-4, SHV-5, CTX-M-15, but low resistance was observed in SHV-2 and CTX-M-9. This suggests the presence of specific SHV enzymes with an increased activity against cefixime; further in-depth studies would be required for confirmation. In our study, resistance to cephalexin showed a positive association with blaCTX-M, but a negative association with blaSHV. Broad spectrum beta-lactamases are usually especially active against the first-generation cephalosporins [48], which explained the positive association with the resistance of cephalexin. Interestingly, our results showed that cephalexin was effective against SHV. Similarly, Bedenic at al. [49] have reported good activity of cephalexin against SHV-2. Observation of the positive association of blaCTX-M with several non-beta lactam antibiotics could indicate the prevalence of specific MDR ESBL clones. Although all of ESBL genes may be located on the mobile genetic elements and are often associated with co-resistance phenotypes with aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole, tetracycline and other antibiotics [50,51], blaCTX-M is most commonly associated with broad MDR strains [29]. Clonal dispersion and the co-selection processes of CTX-M clones promote their spread globally as they are easily transmitted among family members in a colonization [52]. In recent years, there has been concern about the coexistence of blaCTX-M and plasmid-mediated-quinolone-resistance (PMQR), therefore non-discriminatory use of fluoroquinolone may result in the selection and rapid dissemination of MDR ESBLs in commensal E. coli [24]. Furthermore, a strong association of PMQR and blaCTX-Mgroup1 (especially blaCTX-M-15) was observed among ESBL-producing E. coli [53,54]. Dietary zinc for weaned piglets also promotes the abundance of MDR and might promote the selective growth and expression of plasmid-encoded ESBL-producing E. coli [43]. The above factors were responsible for the spread of MDR CTX-M strains on the large farms.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Sample Collection and Characterization of Farms

Fecal samples (n = 615) were collected from 4-week, 5-week, 6-week, 8-week, 12-week and 20-week-old piglets, pigs and sows from four large (L1, L2, L3, L4) and three small (S1, S2, S3) farrow-to-finish pig farms in Latvia. On farms L1, L2, L3, L4, S1, S2 and S3, the total number of the sows was 2100, 700, 1700, 1000, 15, 40, 20, respectively. A more detailed characterization of the farms is given in Table 4. Two of four randomly selected fecal samples were collected in sterile Whirl-Pack bags in each pig pen, depending on the circumstances: immediately after defecation or choosing as recently obtained fecal masses as possible. The samples were transported and stored at 2–8 °C, and the bacteriological examination was started within 24 h.

Table 4.

Characteristics of farms, prophylaxis and antimicrobial policy. AMX–amoxicillin, AMC–amoxicillin + clavulanic acid, CFT–ceftiofur, CFQ–cefquinome, CS–colistin, ENO–enrofloxacin, GM–gentamicin, OT–oxytetracycline, P–penicillin, MAR–marbofloxacin, TM–tiamulin, TY–tylosin, TMP + S–trimethoprim + sulfadiazine, ZnO–Zinc oxide.

| Farm | Total Number of Sows | Time to Weaning (Days) | Diarrhea/Critical Periods | Feed Additives | Antibiotics Used | Immunisation against E. coli b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Penicillin/Board-Spectrum Penicillins | Cephalo-Sporins | Non-Beta Lactams | ||||||

| L1 | 2100 | 28 | common/ 1–3 days; 4–6 weeks; 7–8 weeks |

ZnO–150 mg kg−1 | AMX | CFT | CS, ENO, MAR, OT, SXT a | yes |

| L2 | 700 | 33 | common/ 2–3 weeks; 5–6 weeks |

ZnO–150 mg kg−1; during weaning–zinc and electrolyte agent c |

P, AMX | no | GM, OT, TMP + S, | yes |

| L3 | 1700 | 28 | sporadically | ZnO–150 mg kg−1; starter phase (2–3 weeks after weaning)–ZnO 2500 mg kg−1; water acidification d |

no | CFT, CFQ | CS, ENO, GM, OT, TMP + S, | yes |

| L4 | 1000 | 28 | sporadically | ZnO–150 mg kg−1; | P, AMC | no | OT TMP + S, | no |

| S1 | 15 | 28 | common/ 5–6 weeks |

- | P, AMX | no | ENO, OT, TMP + S | yes |

| S2 | 40 | 28–42 | rare | - | no | no | TY | no |

| S3 | 20 | 40 | rare | - | no | no | TM | no |

a The antibiotic is changed every three months to ensure the effectiveness of the antimicrobial drugs. b For prevention of different strains of E. coli infections, for the passive immunization of progeny (piglets) by active immunization of sows and gilts, “Porcilis ColiClos” is used (AN Boxmeer, Netherlands), c “Revifit (veromin)” (Agro-strefa, Poland), d “Baracid”, (Fermo, Poland).

4.2. Screening of Extended-Spectrum-Beta-Lactamase-Producing E. coli

The screening of ESBL-producing E. coli was performed according to the following method: a directly inoculated sample was placed on the selected media [55,56] Briefly, using a sterile cotton swab, the fecal specimen was gently spread onto the ChromArt ESBL agar (Biolife, Milano, Italy) surface. The plates were incubated at 36 °C for 20–24 h. If the plates were negative, they were re-incubated for an additional 24 h. After the incubation, the large pink colonies were noted and regarded as presumptive ESBL producing E. coli. One typical presumptive ESBL colony was sub-cultured on a Tryptic soy agar (Biolife, IT) and incubated overnight at 36 °C to obtain pure culture for the identification and phenotypic confirmatory test. The oxidase negative, indole positive, urease and citrate negative colonies were considered to be E. coli, and the isolates were confirmed by VITEK MS (bioMerieux SA, Marcy L’Etoile, France) which uses MALDI-TOF technology.

4.3. Phenotypic Confirmatory Test for ESBLs in E. coli

According to EUCAST recommendations [57], the combination disc test (CDT) was chosen for the confirmation of ESBL. The CDT was performed in accordance with the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines [58]. A standardized inoculum (0,5McF) of the presumptive ESBL-producing E. coli isolate was swabbed on the surface of Muller Hinton agar II (Biolife, IT). Cefotaxime 30 μg (CTX-30, BD BBL) and ceftazidime 30 μg (CAZ-30, BD BBL) discs alone and in combination with clavulanic acid 10 μg (CTX CLA and CAZ CLA, Biolife) were placed on the plate. The results were obtained after 18 h incubation at 36 °C. ESBL-producing E. coli was confirmed as positive if there was a ≥5 mm increase in the inhibition zone. This was detected by clavulanic acid around either the cefotaxime or the ceftazidime disc, compared to the diameter around the disc containing cefotaxime or ceftazidime alone. E. coli ATCC 25922 (Bioscience, Botolph Claydon, United Kingdom) was used for the quality control when the ESBL confirmatory test was carried out.

4.4. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

For an in-depth analysis of resistance and molecular studies, 50 fecal ESBL-producing E. coli isolates from 4-week, 5-week, 6-week, 8-week, 12-week, and 20-week-old piglets, pigs and sows were selected by the stratified random sampling method and divided into three large groups: “sows”; 4-week, 5-week and 6-week-old piglets, referred to as “weaning-nursery”; and 8-week, 12-week and 20-week-old pigs, referred to as “growing-finishing”. The antimicrobial susceptibility of ESBL-producing E. coli isolates was determined according to the disc diffusion method [59] using antimicrobial susceptibility test discs (BD BBL Sensi-Disc, ASV) in a total of 18 samples. Eleven of these had beta-lactam group antibiotics: ampicillin (AM, 10 μg), mecillinam (MEL, 10 μg), ticarcillin (TIC, 75 μg), amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (AMC, 20 μg /10 μg), cephalexin (CL, 30 μg), cefazolin (CZ, 30 μg), cefoxitin (FOX, 30 μg), ceftazidime (CAZ, 30 μg), cefotaxime (CTX, 30 μg), cefixime (CFM 5 μg), cefepime (FEP, 30 μg), imipenem (IMP, 10 μg), while the other seven had non-beta-lactam group antibiotics: sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (SXT, 23.75 μg /1.25 μg), trimethoprim (TMP, 5 μg), gentamicin (GM, 10 μg), chloramphenicol (C, 30 μg), tetracycline (TE, 30 μg), enrofloxacin (ENO, 5 μg), ciprofloxacin (CIP, 5 μg). After incubation, the zone (mm) of inhibition was interpreted using the breakpoint tables according to EUCAST (2019) guidelines [60]. Enrofloxacin was not included in the breakpoint table, and therefore it was interpreted according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Based on the directions of Magiorakos et al. [14], ESBL-producing E. coli was defined as MDR if the isolate had non-susceptibility to at least one antimicrobial agent in ≥3 antimicrobial categories [14]. Different levels of MDR were defined according to the ones described before [61]

4.5. Identification of Beta-Lactamase Genes in the Fecal ESBL-Producing E. coli

DNA was extracted using the E.Z.N.A. Bacterial DNA kit (Omega Bio-tek, Norcross, GA, USA) according to the procedure given by the manufacturer [62]. The concentration of DNA was estimated by the ND-1000 Spectrophotometer. The polymerase chain reaction was carried out by HotStarTaq® Plus Master Mix Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) according to the procedure given by the manufacturer.

The identification of the blaTEM gene was conducted with primers TEM forward (5′-AGTGCTGCCATAACCATGAGTG-3′) and TEM reverse (5′-CTGACTCCCCGTCGTGTAGATA-3′). The primers for amplification of the blaSHV gene were SHV forward (5′–GATGAACGCTTTCCCATGATG-3′) and SHV reverse (5′-CGCTGTTATCGCTCATGGTAA-3′), but for the identification of blaCTX-M, gene primers CTX-M-group1 forward (5′–TCCAGAATAAGGAATCCCATGG-3′ and CTX-M-group1 reverse (5′-TGCTTTACCCAGCGTCAGAT-3′) were used.

The amplification reactions were performed in the Applied Biosystems 2720 thermal cycler under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, denaturation at 94 °C for 1 min of 35 cycles, annealing at 55 °C for 1 min for blaTEM, at 53 °C for 1 min for blaCTX-M, at 47 °C for 1 min for blaSHV, then extension at 72 °C for 1 min, followed by the final extension at 72 °C for 10 min.

After the amplification, PCR products were separated by a 2% agarose gel. After electrophoresis, the amplified DNA fragments were visualized by UV transilluminator and the gels were photographed. The amplicon size for blaTEM was 431 bp, for blaSHV it was 214 bp and for blaCTX-M it was 621 bp.

4.6. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was conducted by R Studio software (version 1.1.463). The Chi square test was used to compare the significance of differences in the prevalence of ESBL-producing E. coli between the large and small farms. The pairwise comparisons from the Chi-squared test were used for post hoc identification of significant differences in the prevalence of ESBL-producing E. coli in different farms and in different age groups of pigs. Fifty of ESBL-producing E. coli isolates were selected by the stratified random sampling method for in-depth studies of antimicrobial resistance and beta-lactamase genes. The Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the distribution and proportion of antimicrobial resistance and beta-lactamase genes. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were used to evaluate the associations between beta-lactamase genes and antibiotic resistance. Statistical significance was considered as p < 0.05

5. Conclusions

The prevalence of ESBL-producing E. coli varies widely among farms and although higher prevalence was observed in the large farms, small farms are also of concern. The screening of ESBL-producing E. coli demonstrated a high prevalence of blaCTX-M with extended MDR phenotypes on large farms, but the dominance of blaSHV may also cause trouble due to the high resistance to ceftazidime and cefixime on small farms. Various contributing factors such as piglet diarrhea, the broad use of amoxicillin, fluoroquinolones and zinc included as a feed additive may contribute to a number of hazardous ESBL clones on farms. Individual analysis of the antibiotic resistance situation on small farms could be an important step for revealing hazardous MDR ESBL strains and to review the antimicrobial therapy in use. Large farms are more exposed to the alarming spread of MDR ESBL, which emphasizes the need to limit the use of antimicrobial therapy and the urgency of finding alternative strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.V. and D.G.; sample collection D.G.; methodology (microbiology), D.G.; methodology (molecular biology), A.B.; formal analysis D.G.; investigation, D.G. and A.B.; resources, A.V.; data curation and interpretation, D.G. and A.V.; writing—original draft preparation, D.G.; writing—review and editing, D.G., A.V. and A.B.; visualization, D.G.; supervision, A.V.; project administration, A.V.; funding acquisition, A.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Research Programme AgroBioRes and project European Social Fund No 8.2.2.0/20/I/001.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.EDCD. EFSA. EMA ECDC/EFSA/EMA Second Joint Report on the Integrated Analysis of the Consumption of Antimicrobial Agents and Occurrence of Antimicrobial Resistance in Bacteria from Humans and Food-producing Animals. EFSA J. 2017;15:e04872. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2017.4872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Boeckel T.P., Brower C., Gilbert M., Grenfell B.T., Levin S.A., Robinson T.P., Teillant A., Laxminarayan R. Global Trends in Antimicrobial Use in Food Animals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:5649–5654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1503141112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maes D.G.D., Dewulf J., Piñeiro C., Edwards S., Kyriazakis I. A Critical Reflection on Intensive Pork Production with an Emphasis on Animal Health and Welfare. J. Anim. Sci. 2020;98((Suppl. 1)):S15–S26. doi: 10.1093/jas/skz362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.EFSA. ECDC The European Union Summary Report on Antimicrobial Resistance in Zoonotic and Indicator Bacteria from Humans, Animals and Food in 2017/2018. EFSA J. 2020;18:e06007. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2020.6007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.ESVAC . Sales of Veterinary Antimicrobial Agents in 31 European Countries in 2018. European Medicines Agency; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 2020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silva N., Carvalho I., Currie C., Sousa M., Igrejas G., Poeta P. Extended-Spectrum-β-Lactamase and Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae in Food-Producing Animals in Europe: An impact on public health? In: Capelo-Martinez J.-L., Igrejas G., editors. Antibiotic Drug Resistance. Wiley; Hoboken, NJ, USA: 2019. pp. 261–273. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carvalho I., Cunha R., Martins C., Martínez-Álvarez S., Safia Chenouf N., Pimenta P., Pereira A.R., Ramos S., Sadi M., Martins Â., et al. Antimicrobial Resistance Genes and Diversity of Clones among Faecal ESBL-Producing Escherichia coli Isolated from Healthy and Sick Dogs Living in Portugal. Antibiotics. 2021;10:1013. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10081013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramos S., Silva V., Dapkevicius M.d.L.E., Caniça M., Tejedor-Junco M.T., Igrejas G., Poeta P. Escherichia coli as Commensal and Pathogenic Bacteria among Food-Producing Animals: Health Implications of Extended Spectrum β-Lactamase (ESBL) Production. Animals. 2020;10:2239. doi: 10.3390/ani10122239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHO . Prioritization of Pathogens to Guide Discovery, Research and Development of New Antibiotics for Drug Resistant Bacterial Infections, Including Tuberculosis. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bergšpica I., Kaprou G., Alexa E.A., Prieto M., Alvarez-Ordóñez A. Extended Spectrum β-Lactamase (ESBL) Producing Escherichia coli in Pigs and Pork Meat in the European Union. Antibiotics. 2020;9:678. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9100678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Koster S., Ringenier M., Lammens C., Stegeman A., Tobias T., Velkers F., Vernooij H., Kluytmans-van den Bergh M., Kluytmans J., Dewulf J., et al. ESBL-Producing, Carbapenem- and Ciprofloxacin-Resistant Escherichia coli in Belgian and Dutch Broiler and Pig Farms: A Cross-Sectional and Cross-Border Study. Antibiotics. 2021;10:945. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10080945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Fels-Klerx H.J., Puister-Jansen L.F., van Asselt E.D., Burgers S.L.G.E. Farm Factors Associated with the Use of Antibiotics in Pig Production1. J. Anim. Sci. 2011;89:1922–1929. doi: 10.2527/jas.2010-3046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ström G., Halje M., Karlsson D., Jiwakanon J., Pringle M., Fernström L.-L., Magnusson U. Antimicrobial Use and Antimicrobial Susceptibility in Escherichia coli on Small- and Medium-Scale Pig Farms in North-Eastern Thailand. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2017;6:75. doi: 10.1186/s13756-017-0233-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Magiorakos A.-P., Srinivasan A., Carey R.B., Carmeli Y., Falagas M.E., Giske C.G., Harbarth S., Hindler J.F., Kahlmeter G., Olsson-Liljequist B., et al. Multidrug-Resistant, Extensively Drug-Resistant and Pandrug-Resistant Bacteria: An International Expert Proposal for Interim Standard Definitions for Acquired Resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012;18:268–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dohmen W., Bonten M.J.M., Bos M.E.H., van Marm S., Scharringa J., Wagenaar J.A., Heederik D.J.J. Carriage of Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamases in Pig Farmers Is Associated with Occurrence in Pigs. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2015;21:917–923. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moor J., Aebi S., Rickli S., Mostacci N., Overesch G., Oppliger A., Hilty M. Dynamics of Extended-Spectrum Cephalosporin-Resistant Escherichia coli in Pig Farms: A Longitudinal Study. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2021;48:106382. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2021.106382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmid A., Hörmansdorfer S., Messelhäusser U., Käsbohrer A., Sauter-Louis C., Mansfeld R. Prevalence of Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing Escherichia coli on Bavarian Dairy and Beef Cattle Farms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013;79:3027–3032. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00204-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmithausen R.M., Schulze-Geisthoevel S.V., Stemmer F., El-Jade M., Reif M., Hack S., Meilaender A., Montabauer G., Fimmers R., Parcina M., et al. Analysis of Transmission of MRSA and ESBL-E among Pigs and Farm Personnel. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0138173. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dohmen W., Dorado-García A., Bonten M.J.M., Wagenaar J.A., Mevius D., Heederik D.J.J. Risk Factors for ESBL-Producing Escherichia coli on Pig Farms: A Longitudinal Study in the Context of Reduced Use of Antimicrobials. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0174094. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gay N., Leclaire A., Laval M., Miltgen G., Jégo M., Stéphane R., Jaubert J., Belmonte O., Cardinale E. Risk Factors of Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase Producing Enterobacteriaceae Occurrence in Farms in Reunion, Madagascar and Mayotte Islands, 2016–2017. Vet. Sci. 2018;5:22. doi: 10.3390/vetsci5010022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reyns T., De Boever S., Schauvliege S., Gasthuys F., Meissonnier G., Oswald I., De Backer P., Croubels S. Influence of Administration Route on the Biotransformation of Amoxicillin in the Pig. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009;32:241–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2885.2008.01033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burch D.G.S., Sperling D. Amoxicillin-Current Use in Swine Medicine. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018;41:356–368. doi: 10.1111/jvp.12482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fournier C., Aires-de-Sousa M., Nordmann P., Poirel L. Occurrence of CTX-M-15- and MCR-1-Producing Enterobacterales in Pigs in Portugal: Evidence of Direct Links with Antibiotic Selective Pressure. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2020;55:105802. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2019.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Basu S., Mukherjee M. Incidence and Risk of Co-Transmission of Plasmid-Mediated Quinolone Resistance and Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase Genes in Fluoroquinolone-Resistant Uropathogenic Escherichia coli: A First Study from Kolkata, India. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2018;14:217–223. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2018.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Livermore D.M., Day M., Cleary P., Hopkins K.L., Toleman M.A., Wareham D.W., Wiuff C., Doumith M., Woodford N. OXA-1 β-Lactamase and Non-Susceptibility to Penicillin/β-Lactamase Inhibitor Combinations among ESBL-Producing Escherichia coli. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2019;74:326–333. doi: 10.1093/jac/dky453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rawat D., Nair D. Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamases in Gram Negative Bacteria. J. Glob. Infect. Dis. 2010;2:263–274. doi: 10.4103/0974-777X.68531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liakopoulos A., Mevius D., Ceccarelli D. A Review of SHV Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamases: Neglected Yet Ubiquitous. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:1374. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bonnet R. Growing Group of Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamases: The CTX-M Enzymes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004;48:1–14. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.1.1-14.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zeynudin A., Pritsch M., Schubert S., Messerer M., Liegl G., Hoelscher M., Belachew T., Wieser A. Prevalence and Antibiotic Susceptibility Pattern of CTX-M Type Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamases among Clinical Isolates of Gram-Negative Bacilli in Jimma, Ethiopia. BMC Infect. Dis. 2018;18:524. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3436-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garcia-Graells C., Berbers B., Verhaegen B., Vanneste K., Marchal K., Roosens N.H.C., Botteldoorn N., De Keersmaecker S.C.J. First Detection of a Plasmid Located Carbapenem Resistant BlaVIM-1 Gene in E. coli Isolated from Meat Products at Retail in Belgium in 2015. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020;324:108624. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2020.108624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prescott J.F. Beta-lactam Antibiotics. In: Giguère S., Prescott J.F., Dowling P.M., editors. Antimicrobial Therapy in Veterinary Medicine. John Wiley & Sons; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 2013. pp. 133–152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fuchs F., Hamprecht A. Results from a Prospective In Vitro Study on the Mecillinam (Amdinocillin) Susceptibility of Enterobacterales. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019;63:e02402-18. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02402-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.EMA. CVMP. CHMP . Categorisation of Antibiotics in the European Union. EMA; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hölzel C.S., Müller C., Harms K.S., Mikolajewski S., Schäfer S., Schwaiger K., Bauer J. Heavy Metals in Liquid Pig Manure in Light of Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance. Environ. Res. 2012;113:21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ciesinski L., Guenther S., Pieper R., Kalisch M., Bednorz C., Wieler L.H. High Dietary Zinc Feeding Promotes Persistence of Multi-Resistant E. coli in the Swine Gut. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0191660. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Akwar H.T., Poppe C., Wilson J., Reid-Smith R.J., Dyck M., Waddington J., Shang D., McEwen S.A. Prevalence and Patterns of Antimicrobial Resistance of Fecal Escherichia coli among Pigs on 47 Farrow-to-Finish Farms with Different in-Feed Medication Policies in Ontario and British Columbia. Can. J. Vet. Res. = Rev. Can. Rech. Vet. 2008;72:195–201. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Lucia A., Card R.M., Duggett N., Smith R.P., Davies R., Cawthraw S.A., Anjum M.F., Rambaldi M., Ostanello F., Martelli F. Reduction in Antimicrobial Resistance Prevalence in Escherichia coli from a Pig Farm Following Withdrawal of Group Antimicrobial Treatment. Vet. Microbiol. 2021;258:109125. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2021.109125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jensen V.F., Emborg H.-D., Aarestrup F.M. Indications and Patterns of Therapeutic Use of Antimicrobial Agents in the Danish Pig Production from 2002 to 2008. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012;35:33–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2885.2011.01291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lekagul A., Tangcharoensathien V., Mills A., Rushton J., Yeung S. How Antibiotics Are Used in Pig Farming: A Mixed-Methods Study of Pig Farmers, Feed Mills and Veterinarians in Thailand. BMJ Glob. Health. 2020;5:e001918. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barilli E., Vismarra A., Villa Z., Bonilauri P., Bacci C. ESβL E. coli Isolated in Pig’s Chain: Genetic Analysis Associated to the Phenotype and Biofilm Synthesis Evaluation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019;289:162–167. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2018.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Biasino W., De Zutter L., Garcia-Graells C., Uyttendaele M., Botteldoorn N., Gowda T., Van Damme I. Quantification, Distribution and Diversity of ESBL/AmpC-Producing Escherichia coli on Freshly Slaughtered Pig Carcasses. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2018;281:32–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2018.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Von Salviati C., Friese A., Roschanski N., Laube H., Guerra B., Käsbohrer A., Kreienbrock L., Roesler U. Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamases (ESBL)/AmpC Beta-Lactamases-Producing Escherichia coli in German Fattening Pig Farms: A Longitudinal Study. Berl. Munch. Tierarztl. Wochenschr. 2014;127:412–419. doi: 10.2376/0005-9366-127-412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peng S., Herrero-Fresno A., Olsen J.E., Dalsgaard A. Influence of Zinc on CTX-M-1 β-Lactamase Expression in Escherichia coli. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2020;22:613–619. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2020.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cantón R., Morosini M.I., Martin O., de la Maza S., de la Pedrosa G.E.G. IRT and CMT β-Lactamases and Inhibitor Resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2008;14:53–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bush K., Bradford P.A. Interplay between β-Lactamases and New β-Lactamase Inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019;17:295–306. doi: 10.1038/s41579-019-0159-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Naziri Z., Derakhshandeh A., Soltani Borchaloee A., Poormaleknia M., Azimzadeh N. Treatment Failure in Urinary Tract Infections: A Warning Witness for Virulent Multi-Drug Resistant ESBL- Producing Escherichia coli. Infect. Drug Resist. 2020;13:1839–1850. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S256131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Livermore D.M., Mushtaq S., Nguyen T., Warner M. Strategies to Overcome Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamases (ESBLs) and AmpC β-Lactamases in Shigellae. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2011;37:405–409. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Paterson D.L., Bonomo R.A. Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamases: A Clinical Update. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2005;18:657–686. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.4.657-686.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bedenic B., Vranes J., Suto S., Zagar Z. Bactericidal Activity of Oral β-Lactam Antibiotics in Plasma and Urine versus Isogenic Escherichia coli Strains Producing Broad- and Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamases. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2005;25:479–487. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2005.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ozgumus O.B., Tosun I., Aydin F., Kilic A.O. Horizontol Dissemination of TEM- and SHV-Typr Beta-Lactamase Genes-Carrying Resistance Plasmids amongst Clonical Isolates of Enterobacteriaceae. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2008;39:636–643. doi: 10.1590/S1517-83822008000400007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Balkhed Å.Ö., Tärnberg M., Monstein H.-J., Hällgren A., Hanberger H., Nilsson L.E. High Frequency of Co-Resistance in CTX-M-Producing Escherichia coli to Non-Beta-Lactam Antibiotics, with the Exceptions of Amikacin, Nitrofurantoin, Colistin, Tigecycline, and Fosfomycin, in a County of Sweden. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 2013;45:271–278. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2012.734636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cantón R., González-Alba J.M., Galán J.C. CTX-M Enzymes: Origin and Diffusion. Front. Microbiol. 2012;3:110. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Salah F.D., Soubeiga S.T., Ouattara A.K., Sadji A.Y., Metuor-Dabire A., Obiri-Yeboah D., Banla-Kere A., Karou S., Simpore J. Distribution of Quinolone Resistance Gene (Qnr) in ESBL-Producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp. in Lomé, Togo. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2019;8:104. doi: 10.1186/s13756-019-0552-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim J.O., Yoo I.Y., Yu J.K., Kwon J.A., Kim S.Y., Park Y.-J. Predominance and Clonal Spread of CTX-M-15 in Cefotaxime-Resistant Klebsiella Pneumoniae in Korea and Their Association with Plasmid-Mediated Quinolone Resistance Determinants. J. Infect. Chemother. 2021;27:1186–1192. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2021.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lalak A., Wasyl D., Zając M., Skarżyńska M., Hoszowski A., Samcik I., Woźniakowski G., Szulowski K. Mechanisms of Cephalosporin Resistance in Indicator Escherichia coli Isolated from Food Animals. Vet. Microbiol. 2016;194:69–73. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2016.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Blanc D.S., Poncet F., Grandbastien B., Greub G., Senn L., Nordmann P. Evaluation of the Performance of Rapid Tests for Screening Carriers of Acquired ESBL-Producing Enterobacterales and Their Impact on Turnaround Time. J. Hosp. Infect. 2021;108:19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.EUCAST EUCAST Guidelines for Detection of Resistance Mechanisms and Specific Resistances of Clinical and/or Epidemiological Importance; Version 2.0. 2017. [(accessed on 10 September 2021)]. Available online: https://www.eucast.org/resistance_mechanisms/

- 58.CLSI Performance Standards for Antimicrobial & Antifungal Susceptibility Testing. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, USA, M100 ED28:2018. 2018. [(accessed on 10 September 2021)]. Available online: https://clsi.org/about/about-clsi/about-clsi-antimicrobial-and-antifungal-susceptibility-testing-resources/

- 59.EUCAST EUCAST Disk Diffusion Method for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, Version 6.0. 2017. [(accessed on 10 September 2021)]. Available online: https://kaldur.landspitali.is/focal/gaedahandbaekur/gnhsykla.nsf/5e27f2e5a88c898e00256500003c98c2/795d21eac4c71fdf00257ac30056d723/$FILE/Manual_v_6.0_EUCAST_Disk_Test_final.pdf.

- 60.EUCAST The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters. Version 9.0. 2019. [(accessed on 14 June 2019)]. Available online: http://www.Eucast.org.

- 61.Jahanbakhsh S., Smith M.G., Kohan-Ghadr H.-R., Letellier A., Abraham S., Trott D.J., Fairbrother J.M. Dynamics of Extended-Spectrum Cephalosporin Resistance in Pathogenic Escherichia coli Isolated from Diseased Pigs in Quebec, Canada. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2016;48:194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kaftandzieva A., Trajkovska-Dokic E., Panovski N. Prevalence and Molecular Characterization of Extended Spectrum Beta-Lactamases (ESBLs) Producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella Pneumoniae. Prilozi. 2011;32:129–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.