Abstract

The Src substrate p130Cas is a docking protein containing an SH3 domain, a substrate domain that contains multiple consensus SH2 binding sites, and a Src binding region. We have examined the possibility that Cas plays a role in the transcriptional activation of immediate early genes (IEGs) by v-Src. Transcriptional activation of IEGs by v-Src occurs through distinct transcriptional control elements such as the serum response element (SRE). An SRE transcriptional reporter was used to study the ability of Cas to mediate Src-induced SRE activation. Coexpression of v-Src and Cas led to a threefold increase in SRE-dependent transcription over the level induced by v-Src alone. Cas-dependent activation of the SRE was dependent on the kinase activity of v-Src and the Src binding region of Cas. Signaling to the SRE is promoted by a serine-rich region within Cas and inhibited by the Cas SH3 domain. Cas-dependent SRE activation was accompanied by an increase in the level of active Ras and in the activity of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) Erk2; these changes were blocked by coexpression of dominant-negative mutants of the adapter protein Grb2. SRE activation was abrogated by coexpression of dominant-negative mutants of Ras, MAPK kinase (Mek1), and Grb2. Coexpression of Cas with v-Src enhanced the association of Grb2 with the adapter protein Shc and the protein tyrosine phosphatase Shp-2; coexpression of Shc or Shp-2 mutants significantly reduced SRE activation by Cas and v-Src. Cas-induced Grb2 association with Shp-2 and Shc may account for the Cas-dependent activation of the Ras/Mek/Erk pathway and SRE-dependent transcription. 14-3-3 proteins may also play a role in Cas-mediated signaling to the SRE. Overexpression of Cas was found to modestly enhance epidermal growth factor (EGF)-induced activation of the SRE. A Cas mutant lacking the Src binding region did not potentiate the EGF response, suggesting that Cas enhances EGF signaling by binding to endogenous cellular Src or another Src family member. These observations implicate Cas as a mediator of Src-induced transcriptional activation.

Tyrosine phosphorylation of cellular proteins is important for signaling by c-Src and for transformation by v-Src (20, 50). One of these proteins, p130Cas (Crk-associated substrate), was identified as a tyrosine-phosphorylated protein in v-Crk- and v-Src-transformed cells (40). Cas is a member of a new family of docking proteins that includes HEF1 (23) and Sin (2). The structure of Cas suggests that it plays a role in the formation of multiprotein signaling complexes. Cas contains an SH3 domain, a substrate domain (SD), a serine-rich region, and a Src binding (SB) site. The N-terminal SH3 domain mediates the interaction of Cas with several proteins, including FAK (focal adhesion kinase) (14, 36), a tyrosine kinase that has been implicated in signaling to the Erk mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway (42, 43); the protein tyrosine phosphatases PTP1B (25) and PTP-PEST (12), which have been shown to promote the dephosphorylation of Cas; and the guanine nucleotide exchange factor C3G (22), which may mediate signaling to the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) MAPK pathway (49). The SD contains multiple tyrosine residues which, upon phosphorylation, generate consensus binding sequences for the SH2 domains of other proteins. A glutathione S-transferase (GST)–SD fusion protein has been shown to bind several proteins, including Crk, in lysates from v-Src- and v-Crk-transformed cells (6). The serine-rich region has no known function but is conserved in HEF1. The C-terminal SB region contains binding sites for the SH3 and SH2 domains of Src (33). This region is required for extensive tyrosine phosphorylation of Cas in cells expressing activated c-Src. Its presence, together with other data, implies that Cas is a direct substrate of Src (33, 41, 52).

Although the function of Cas is unclear, it has been suggested that it plays a role in signaling and cellular transformation by Src. Integrin-mediated cell adhesion results in c-Src-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of Cas and induces its association with the SH2 domains of phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase (PI3-kinase), the adapter proteins Crk, Grb2, and Nck, phospholipase Cγ, and the protein tyrosine phosphatase Shp-2 (28, 41, 52). Likewise, v-Src expression stimulates the association of Cas with Crk (33). Formation of such signaling complexes could mediate the activation of multiple signaling cascades. Expression of Cas antisense mRNA results in partial reversion of the morphological phenotype of v-Src-transformed cells (3). More recently, Honda et al. generated cas−/− mice and observed that expression of activated c-Src in cas−/− primary fibroblasts resulted in incomplete transformation: the transformed cells displayed a spindle-like morphology, in contrast to the rounded morphology characteristic of wild-type fibroblasts expressing activated c-Src, and were unable to grow in suspension culture (17).

Various mitogens including epidermal growth factor (EGF), platelet-derived growth factor, and lysophosphatidic acid can also induce tyrosine phosphorylation of Cas (8, 35). Exposure to mitogens and v-Src expression both result in transcriptional activation of immediate-early genes (IEGs). IFGs play a role in mitogenesis and contribute to transformation by v-Src (30, 46, 51). Transcriptional activation of IEGs involves transcriptional control elements (7, 15, 50), one of which, the serum response element (SRE), responds to multiple signaling cascades. Activation of the Erk MAPK or the JNK MAPK pathway can result in SRE-dependent transcription (7). In addition, Qureshi et al. have shown that in 3T3 cells, Erk MAPK pathway components, the small GTPase Ras and the serine-threonine kinase Raf, are required for SRE-dependent gene expression induced by v-Src (37). It has thus been suggested that Cas, through association with other proteins, could signal through the Erk and JNK MAPK pathways (5, 22, 41, 52) to SRES.

Activation of the Erk and JNK MAPK pathways is known to be initiated by small GTPases such as Ras, Rac, and Cdc42, which in turn can be regulated by multiple pathways. Activation of Ras may be mediated by a family of adapter proteins containing SH2 and SH3 domains, such as Grb2. These adapter proteins associate with the Ras GTP exchange factor SOS and can transduce signals from tyrosine kinases to Ras (18, 29, 47). Various stimuli have been shown to induce the association of Grb2 with the adapter protein Shc and the protein tyrosine phosphatase Shp-2 (also known as SHPTP2, Syp, and PTP1D). Formation of Grb2-Shc (39, 44) or Grb2–Shp-2 (24, 34) complexes presumably targets SOS to the plasma membrane, where it can activate Ras. Activation of the JNK MAPK pathway, on the other hand, may involve the GTPases Rac and Cdc42 and the JNK kinase Mkk4 (7).

We have used an SRE reporter assay to examine the role of Cas in Src-induced transcriptional activation. We report here that Cas promotes Src signaling to the SRE through a Grb2/Ras/Erk MAPK pathway. Cas appears to activate the Ras/Erk MAPK pathway by inducing the association of Grb2 with Shc and Shp-2.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

D. Foster (Hunter College, New York, N.Y.) provided the SRE-luciferase reporter construct, pSREtkLuc, in which the luciferase gene is downstream of a thymidine kinase minimal promoter and four SREs (9). pUHD16.1, a lacZ plasmid expressing β-galactosidase, was obtained from M. Gossen (University of California, Berkeley [U.C. Berkeley]). Wild-type and K295M v-Src were subcloned into the murine retroviral vector pBabe-Puro (32). Cas and hemagglutinin epitope (HA)-tagged wild-type Cas (Caswt), CasΔSH3, CasΔSD, and CasΔSB inserted into the mammalian expression vector pSSRα were obtained from H. Hirai (University of Tokyo Hospital, Tokyo, Japan) (33). pSSRα-HA-CasΔSer, lacking bp 1330 to 1669, was constructed by PCR as follows. A PCR product containing Cas bp 1027 to 1330 with a BlpI restriction site inserted at the 3′ end was digested with NdeI and BlpI. This fragment was then subcloned into pSSRα-HA-Caswt from which bp 1027 to 1669 had been removed by digestion with NdeI and BlpI. For construction of Cas point mutants, the megaprimer method was used to perform site-directed mutagenesis (54). Y106, Y751, and Y913 were replaced with phenylalanine residues. The triple-point mutant was constructed by subcloning techniques using the single-point mutants. Constructs were verified by DNA sequencing. For Cas antibody production, a pGEX-1 plasmid containing nucleotides 1403 to 2106 of the p130 cDNA was obtained from H. Hirai (40). H-Ras in the mammalian expression vector pEXV was obtained from D. Aftab (U.C. Berkeley). pcDNA3-N17Ras was previously described (1). An HA-tagged Erk2 plasmid, pLNC-MK-EA, was obtained from M. Weber (University of Virginia). pSRα3-K97M-Mek1, a construct expressing dominant-negative Mek1, was obtained from N. Ahn (University of Colorado). A construct expressing dominant-negative Mkk4, pcDNA3-Mkk4-Ala, was obtained from R. Davis (University of Massachusetts Medical Center). The dominant-negative adapter mutants Grb2K86, Grb2K36,193, NckSH3all, Crk1K170, and Crk2K170, each inserted into the vector pEBB, were obtained from B. Mayer (The Children’s Hospital, Boston, Mass.) (48). pGEX-GNH was previously described (16). pGEX-KG Grb2wt, Grb2K86, and Grb2K36,193 were constructed by subcloning Grb2 DNA from the pEBB constructs into pGEX-KG. pcDNA3 ShcY317F was obtained from T. Pawson (Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada). A construct expressing catalytically inactive Shp-2, pcDNA3 Shp-2 C463S, was obtained from G. S. Feng (Indiana University).

Cell culture and reporter assays.

Human embryonic kidney 293 cells were grown in a mixture of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (1 part) and Ham’s F-10 nutrient mixture (2 parts) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). Cells were plated in 60-mm-diameter dishes 20 to 24 h prior to transfection. Cells were transiently transfected by the calcium phosphate method with 0.1 μg of pSREtkLuc, 0.2 μg of pBabe-Puro v-Src, and 8.0 μg of a Cas expression construct. The total amount of DNA transfected was kept constant by including the appropriate empty vector where needed. Constructs encoding dominant-negative mutants (3.0 μg of DNA) were included in the transfections where indicated. LY294002 and GF109203X (Calbiochem) were added posttransfection to 4.0 and 0.4 μM, respectively; 0.15 μg of pUHD16.1 was included in samples to normalize for the transfection efficiency. Cells were transfected for 6 to 8 h and subsequently cultured for ∼40 h. Cells were lysed, and extracts were assayed for luciferase activity, using a Promega kit, and for β-galactosidase activity. Results are the means and standard deviations of three independent experiments.

For EGF stimulation, transfected (with 20 ng of pSREtkLuc) cells were cultured 20 h posttransfection and then serum starved in DMEM containing 0.5% fetal calf serum for 24 h. Cells were either left unstimulated or stimulated with EGF (10 ng/ml) for 5 h. The statistical significance of data was analyzed with a one-tailed Student’s t test.

Antibodies.

The anti-Cas2 antibody was generated by immunizing rabbits with a GST-Cas fusion protein purified from Escherichia coli (40). Polyclonal anti-GST antiserum was provided by S. H. Kim (U.C. Berkeley). The following antibodies were purchased: anti-HA rat monoclonal (Boehringer Mannheim), anti-Grb2 and anti-14-3-3 β (K-19) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), anti-pan Ras (Ab-2; Oncogene Research Products), antiphosphotyrosine (4G10; Upstate Biotechnology, Inc.), and anti-Shc and anti-Shp-2 (Transduction Laboratories).

Detection of Ras[GTP].

Cells were transfected with the indicated constructs and pEXV-H-Ras and lysed in 0.5 ml of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM MgCl2, 1% Nonidet P-40, protease inhibitors [1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 μM benzamidine, 5 μM phenanthroline, and 0.5 μg each of antipain, leupeptin, pepstatin, aprotinin, and chymostatin per ml]) per 10-cm-diameter dish. Samples were adjusted to equal protein levels (2 mg/ml). GST-RafRBD (GST-GNH) was purified from bacteria expressing pGEX-GNH (encoding the Ras interaction domain of Raf), with glutathione-Sepharose beads. Lysates were incubated with 5 μl of packed beads for 1 h at 4°C with mixing. The beads were then washed four times in lysis buffer, subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) on a 15% acrylamide gel, and blotted onto Immobilon-P transfer membrane (Millipore). Ras was detected by immunoblotting with an anti-pan Ras antibody followed by a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody to mouse immunoglobulin (Pierce). Bands were visualized with Western Blot Chemiluminescence Reagent Plus (NEN).

MAPK assay.

The activity of Erk2 was measured essentially as described previously (1), with the following modifications. Cells were transfected with the indicated constructs and the HA-tagged Erk2 plasmid and lysed in MAPK lysis buffer (1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 50 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM Na3VO4, 50 mM NaF, 40 mM NaP2O7, 5 mM EDTA, 5 mM EGTA, protease inhibitors). Then 400 μg of lysate was precleared with a 30-μl bed volume of protein G-Sepharose beads, and HA-Erk2 was immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibodies. Immunoprecipitates were washed three times with lysis buffer and once with 100 mM NaCl–25 mM Tris (pH 7.5) and then resuspended in 25 μl of kinase buffer (20 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 20 mM MgCl2, 2 mM dithiothreitol) containing 10 μg of myelin basic protein (MBP). Kinase reactions were initiated by the addition of 10 μl of 50 μM [γ-32P]ATP (10 Ci/mmol), allowed to proceed at room temperature for 20 min, and terminated by the addition of 2× SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Samples were resolved on a 12.5% low-bis (0.07%)–15% step-gradient acrylamide gel. The 12.5% low-bis portion of the gel was used for immunoblot analysis of HA-Erk2; the 15% portion of the gel was used to visualize phosphorylated MBP by autoradiography. The radiolabel in the MBP band was quantitated by scanning densitometry with NIH Image software.

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analysis.

Transfected cells were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% SDS, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA, 2 mM Na3VO4, protease inhibitors). Lysates were cleared by centrifugation (14,000 × g for 10 min) and adjusted to equal protein concentrations (1.5 to 2.5 mg/ml). For Grb2 immunoprecipitation, lysates were incubated with agarose-conjugated anti-Grb2 antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Immunoprecipitates were washed three times with radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer, subjected to SDS-PAGE on a 7.5%–15% step-gradient acrylamide gel, and examined by immunoblot analysis. Immunoprecipitated Grb2 was detected by blotting with anti-Grb2 antibody followed by a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated γ-chain-specific secondary antibody to rabbit immunoglobulin G (Sigma). Cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis using 7.5% acrylamide gels and the indicated antibodies.

Overlay assay.

Cas was immunoprecipitated from 200 μg of lysate with anti-Cas2 antibodies, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and blotted onto Immobilon-P transfer membrane. Blots were blocked with 5% milk powder–5% bovine serum albumin in Tris-buffered saline for 1 h and then probed with blocking buffer containing 2 μg of GST, GST-Grb2wt, GST-Grb2K86, or GST-Grb2K36,193 per ml purified from bacteria expressing the corresponding pGEX-KG construct. The blots were subsequently washed with 5% bovine serum albumin in Tris-buffered saline, probed with anti-GST antiserum, and washed three times, and bands were detected as described above.

RESULTS

Cas cooperates with v-Src in SRE-dependent transcriptional activation.

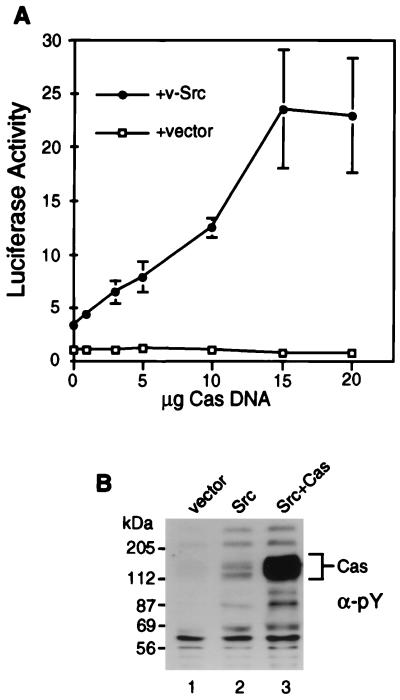

We used a transcriptional reporter assay to determine whether Cas promotes v-Src signaling to the SRE. 293 cells were transiently transfected with increasing amounts of Cas DNA, with or without v-Src DNA, and a luciferase reporter plasmid. The reporter construct contains, upstream of the luciferase gene, a minimal thymidine kinase promoter, plus four SREs from the Egr-1 promoter, which have previously been shown to mediate Egr-1 expression induced by v-Src (38). Because multiple signaling pathways may mediate v-Src-induced SRE activation, a limiting amount of v-Src DNA was used to decrease the contribution of pathways that are not dependent on Cas. In the absence of v-Src, the expression of Cas did not enhance the level of luciferase activity (Fig. 1A). Expression of v-Src alone resulted in a ∼4-fold increase in luciferase activity. Coexpression of Cas with the same amount of v-Src increased the levels of luciferase activity in a dose-dependent manner; the maximum level of stimulation was ∼6-fold above the levels induced by v-Src alone. Overexpression of Cas did not affect total v-Src kinase activity, as judged by immunoblot analysis of cell lysates with antiphosphotyrosine antibody; two phosphotyrosine bands (87 and 100 kDa) were enhanced by cotransfection with Cas, possibly reflecting an alteration in Src substrate specificity or intracellular targeting (Fig. 1B). Therefore, Cas synergizes with v-Src in SRE-dependent transcriptional activation.

FIG. 1.

Src and Cas signaling to the SRE. (A) 293 cells were transiently transfected with the SRE-luciferase reporter construct pSREtkLuc and indicated amounts of Cas DNA (pSSRα-Cas) together with DNA encoding v-Src (pBabe-Puro v-Src; closed circles) or empty vector (pBabe-Puro; open squares). Luciferase activity was measured as described in Materials and Methods and normalized to a vector control set to a value of 1. (B) Immunoblot analysis of cell lysates with antiphosphotyrosine antibody (α-PY). Lysates are of cells transfected with empty vectors (lane 1), 0.2 μg of v-Src DNA (lane 2), or 0.2 μg of v-Src and 8 μg of Cas DNA (lane 3).

Src association and kinase activity are required for Cas-mediated transcriptional activation.

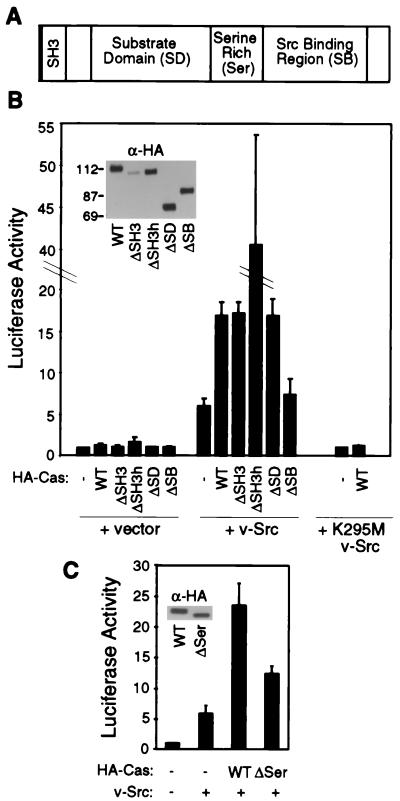

To identify determinants of Cas which are required for this cooperation in signaling to the SRE, reporter assays were carried out with HA-tagged deletion mutants of Cas. Expression of v-Src alone gave a 5-fold increase in luciferase activity, while coexpression of v-Src with Caswt induced a 15-fold response (Fig. 2B). Transfection of equal amounts of CasΔSH3 DNA gave similar levels of luciferase activity in the presence of v-Src. However, immunoblot analysis with either anti-HA (Fig. 2B, inset) or anti-Cas2 (data not shown) antibodies indicated that the level of expression of CasΔSH3 protein was lower than that of Caswt. When a higher amount of CasΔSH3 DNA was transfected (Fig. 2B, ΔSH3h) to give the same level of protein expression as Caswt, a 40-fold increase in luciferase activity was observed, suggesting that the SH3 domain plays a negative regulatory role. Coexpression of v-Src with the substrate domain deletion mutant CasΔSD resulted in levels of luciferase activity equivalent to that induced by Caswt. This implies that proteins bound to Cas via the SD are not responsible for mediating SRE activation. Coexpression of v-Src with the CasΔSB mutant, which lacks a region containing the Src SH2 and SH3 binding sites, elicited levels of luciferase activity similar to those induced by v-Src alone. Caswt and mutants were expressed at similar protein levels and did not induce luciferase activity in the absence of v-Src (Fig. 2B). These data suggest that the association of Cas with Src is required for Cas-dependent SRE activation. However, we cannot rule out the formal possibility that Cas-dependent SRE activation requires the interaction of the Cas SB region with proteins other than Src.

FIG. 2.

Activation of the SRE by Cas and Src mutants. (A) Schematic representation of Cas. (B and C) Luciferase activity in cells cotransfected with pSREtkLuc, pSSRα with insertion of HA-tagged wild-type or mutant Cas, and either empty vector (pBabe-Puro), pBabe-Puro v-Src, or pBabe-Puro K295M v-Src. Transfection conditions were as described in Materials and Methods except that in transfections designated ΔSH3h, 15 μg of HA-CasΔSH3 DNA was used. Relative expression levels of Cas proteins (inset panels) were detected by immunoblot analysis of cell lysates using anti-HA antibody (α-HA).

To determine whether Src kinase activity is required for Cas-mediated signaling, reporter assays were carried out with a catalytically inactive mutant of v-Src, K295M (Fig. 2B). Expression of K295M v-Src in the absence or presence of Caswt failed to induce SRE-dependent transcriptional activation. Therefore, Cas-mediated transcriptional regulation appears to require direct interaction of Cas with catalytically active Src.

A serine-rich region lies between the SD and the SB region (Fig. 2A). Coexpression of v-Src with a Cas mutant lacking the serine-rich region (CasΔSer) induced transcriptional activation to approximately half of the level induced by coexpression of v-Src with Caswt (Fig. 2C). The wild-type and ΔSer forms of Cas protein were expressed at similar levels (Fig. 2C, inset), and coimmunoprecipitation experiments revealed that v-Src associates with CasΔSer to the same extent as with Caswt (data not shown). These findings indicate that the serine-rich region of Cas promotes Cas-dependent SRE activation. The serine-rich region contains a putative 14-3-3 binding sequence, RSXSXP, but in coimmunoprecipitation experiments we could not detect any association of Cas with 14-3-3 proteins (data not shown). However, our inability to detect an association between the two proteins could be due to the sensitivity of the assay. Indeed, it has recently been shown that Cas associates with 14-3-3 proteins in 293 cells (11). The role of this serine-rich region in signaling remains unclear: it is possible that deletion of this region in some way affects the overall charge and conformation of Cas; alternatively, this segment may contain binding sites for a 14-3-3 protein or some other signaling protein.

The Ras/Mek pathway is required for Cas-dependent activation of the SRE.

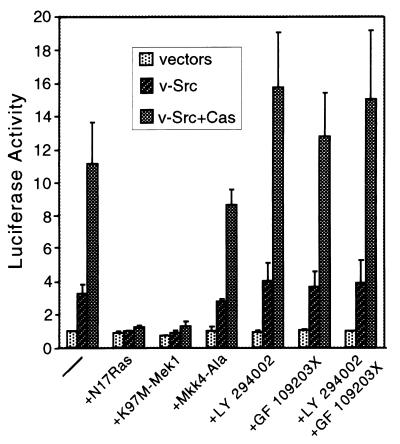

Activation of the Erk or JNK MAPK pathways by various stimuli results in SRE-dependent transcription (7). Activation of the Erk MAPK pathway may be mediated by Ras, PI3-kinase, or protein kinase C (PKC), while activation of the JNK MAPK pathway may be mediated by the Rho family members Rac and Cdc42 (7, 13). To identify the signaling cascade transducing Cas-mediated SRE activation, dominant-negative mutants or pharmacological inhibitors of various signaling molecules were incorporated into the reporter assay. When either dominant-negative Ras, N17Ras, or dominant-negative Erk MAPK kinase (Mek1), K97M-Mek1, was coexpressed with v-Src and Cas, SRE-dependent transcriptional activation was abolished (Fig. 3). On the other hand, when Mkk4-Ala, a dominant-negative form of the JNK MAPK kinase (Mkk4), was coexpressed with v-Src and Cas, the level of luciferase activity was not significantly decreased. Transcriptional activation was not blocked when cells coexpressing v-Src and Cas were treated with LY294002 (an inhibitor of PI3-kinase), with GF109203X (an inhibitor of PKC), or both. Therefore, the Ras/Mek/Erk pathway is required for Src/Cas-dependent signaling to the SRE, while PI3-kinase, PKC, and the JNK MAPK pathway do not appear to be involved.

FIG. 3.

Effects of dominant-negative mutants of signaling proteins or pharmacological inhibitors on Src- and Cas-dependent SRE activation. Luciferase activity was determined in cells transfected with either empty vectors, pBabe-Puro v-Src, or pBabe-Puro v-Src and pSSRα-HA-Cas. Where indicated, the cells were also cotransfected with dominant-negative mutant constructs or treated with LY294002, GF109203X, or both.

Grb2 is necessary for Src and Cas signaling to the SRE.

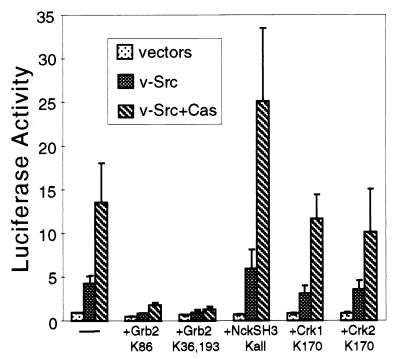

The adapter proteins Grb2, Nck, CrkI, and CrkII, which contain SH2 and SH3 domains but no catalytic domain, are known to mediate Ras/MAPK activation. This activation occurs by association of the adapter protein with the Ras guanine nucleotide exchange factor SOS. To determine if one or more of these adapter proteins plays a role in Cas-dependent Ras activation, we used dominant-negative mutants containing point mutations that render the SH3 and SH2 domains nonfunctional (48). Coexpression of either SH3 (Grb2K36,193) or SH2 (Grb2K86) point mutants of Grb2 abrogated Src- and Cas-dependent SRE activation (Fig. 4). Coexpression of Nck, CrkI, or CrkII SH3 mutants with v-Src and Cas did not significantly decrease the levels of luciferase activity. Similarly, SH2 point mutants of Nck, CrkI, or CrkII did not suppress luciferase activity (data not shown). The suppression of Cas/Src-dependent SRE activation by the Grb2 point mutants was reversed by coexpression of wild-type Grb2, suggesting that the Grb2 mutants were acting as specific Grb2 dominant-negative forms rather than titrating some other required signaling component (data not shown). Thus, functional Grb2 is necessary for Src- and Cas-dependent signaling to the SRE.

FIG. 4.

Effects of dominant-negative mutants of the adapter proteins Grb2, Nck, and Crk on Src- and Cas-dependent SRE activation. The reporter assay was performed on cells transfected with empty vectors, pBabe-Puro v-Src, or pBabe-Puro v-Src and pSSRα-HA-Cas. Where indicated, the cells were also cotransfected with dominant-negative adapter proteins.

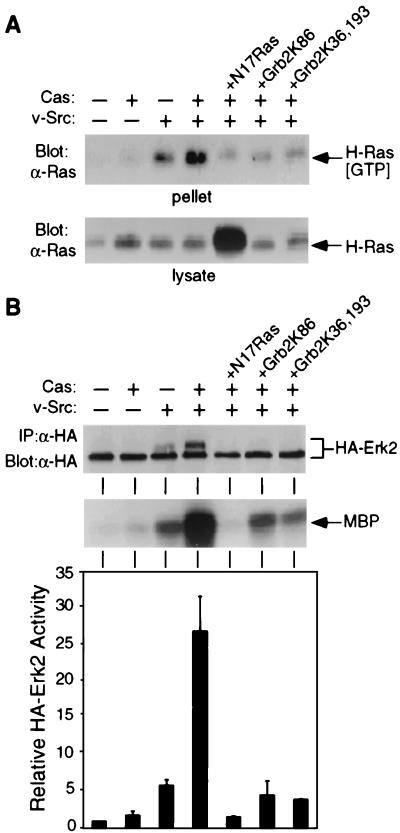

Src induces Ras and Erk2 activation through Cas and Grb2.

The findings described above indicate that Grb2, Ras, and Erk MAPK are required for Cas/Src-dependent activation of the SRE. These observations suggest that Grb2 could mediate Cas-dependent activation of the Ras/MAPK pathway. Alternatively, the Grb2/Ras/MAPK pathway might represent a parallel pathway required for Cas/Src signaling to the SRE. To distinguish between these models, we examined the effects of Cas and dominant-negative mutants of Grb2 on the activation of the Ras/Erk MAPK pathway by v-Src. GTP-bound Ras was selectively precipitated with a GST-RafRBD fusion protein containing the Ras binding domain of Raf and quantitated by immunoblot analysis of the GST-RafRBD precipitates (16). Cells were transfected with DNA encoding H-Ras in the presence or absence of cotransfected v-Src and Cas. Overexpression of Cas alone did not increase the level of Ras-GTP, while expression of Src alone resulted in a moderate increase over the vector control (Fig. 5A, upper panel). Cotransfection of v-Src and Cas DNA increased the level of Ras-GTP over the level observed following transfection with v-Src alone. The level of H-Ras expression was not affected by coexpression of Src and Cas, separately or in combination (Fig. 5B, lower panel). As expected, coexpression of dominant-negative Ras, N17Ras, dramatically decreased the level of Ras-GTP. Coexpression of a Grb2 dominant-negative mutant, either Grb2K86 or Grb2K36,193, similarly abrogated the cooperative activation of Ras by v-Src and Cas.

FIG. 5.

Cas and Grb2 regulation of Ras and Erk2 activation by v-Src. (A) Activation of Ras in cells cotransfected with DNA encoding H-Ras and the indicated proteins. GST-RafRBD bound to glutathione-Sepharose beads was incubated with cell lysates and precipitated. Coprecipitated Ras[GTP] was detected by immunoblot analysis with anti-Ras antibody (α-Ras) (upper panel). The lower panel shows immunoblot detection of Ras protein in cell lysates. (B) Activation of Erk2 in cells cotransfected with DNAs encoding HA-Erk2 and the indicated proteins. HA-Erk2 was immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-HA antibody (α-HA) and was used in an immune complex kinase assay with MBP as a substrate. The samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-HA antibody (upper panel); autoradiography was performed to detect phosphorylated MBP (middle panel). MBP phosphorylation was quantitated by scanning densitometry of autoradiograms (lower panel). Results are the means and standard deviations of three independent experiments.

Erk2 activation was measured by immune complex kinase assays using immunoprecipitated HA-Erk2 and MBP as a substrate (Fig. 5B, middle panel). Activated Erk2 was also detected as an electrophoretically retarded species in anti-HA immunoprecipitates immunoblotted with the same anti-HA antibody (Fig. 5B, upper panel). Overexpression of Cas resulted in a very slight increase in the activation of Erk2, while v-Src alone stimulated activation ∼6-fold relative to a vector control (Fig. 5B, middle and lower panels). Coexpression of v-Src and Cas resulted in a ∼25-fold stimulation of Erk2 activity. Coexpression of N17Ras, Grb2K86, or Grb2K36,193 reduced this stimulation to ∼1- to 4-fold. Therefore, Cas requires Grb2 to mediate Ras-dependent Erk2 activation induced by v-Src.

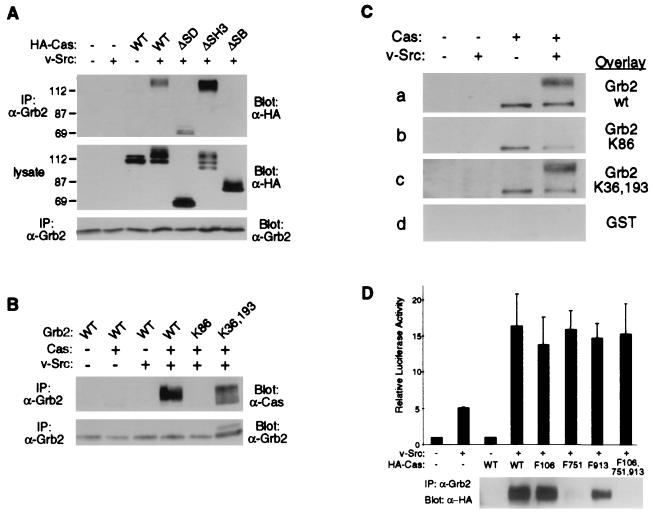

Grb2 directly associates with Cas, but this association is not responsible for signaling to the SRE.

Upon integrin stimulation, Grb2 can associate with Cas in vitro through its SH2 domain (52). Direct association between Grb2 and Cas might be responsible for SRE activation. Coimmunoprecipitation experiments were therefore carried out to define the association between Grb2 and Cas in vivo. Lysates of cells overexpressing Grb2, HA-Cas, and/or v-Src were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-Grb2 antibody, and the immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-Grb2 and anti-HA antibodies (Fig. 6A, upper and lower panels). HA-Cas was found to coprecipitate with Grb2 when coexpressed with v-Src (Fig. 6A, upper panel). To identify the region of Cas required for its association with Grb2, we cotransfected HA-tagged Cas mutants with Grb2 and v-Src DNAs and performed coimmunoprecipitation experiments. The level of CasΔSD coprecipitated with Grb2 was comparable to that observed with Caswt (Fig. 6A, upper panel), indicating that the substrate domain is not necessary for association. We found a higher level of CasΔSH3 associated with Grb2 than with Caswt (Fig. 6A, upper panel), despite the lower expression level observed in cell lysates (Fig. 6A, middle panel). This indicates that the association of Grb2 with Cas is not mediated by proteins, such as FAK, which bind Cas through the SH3 domain. CasΔSB did not coprecipitate with Grb2, suggesting that the association of Src with Cas is required for the coprecipitation and/or that Grb2 binds within this region. To identify the domain of Grb2 which mediates its association with Cas, coimmunoprecipitation experiments were performed with Grb2 SH2 and SH3 domain point mutants. In the presence of coexpressed v-Src, Cas did not coprecipitate with Grb2K86, suggesting that a functional Grb2 SH2 domain is required for the association with Cas (Fig. 6B, upper panel). Cas was able to associate with Grb2K36,193, although to a lesser degree than Grb2wt.

FIG. 6.

Grb2 association with Cas. (A) Coprecipitation of wild-type and mutant forms of HA-Cas with Grb2wt. Lysates were prepared from cells transfected with DNA constructs expressing Grb2 in the presence or absence of coexpressed v-Src, plus the wild-type or mutant forms of HA-Cas. Lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-Grb2 antibody (α-Grb2) and the immunoprecipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-HA antibody (upper panel). The expression of HA-Cas mutants was monitored by immunoblot analysis of cell lysates with anti-HA antibody (α-HA) (middle panel). Immunoprecipitated Grb2 proteins were detected by immunoblotting with anti-Grb2 antibody (lower panel). Sizes are indicated in kilodaltons. (B) Coprecipitation of Caswt with wild-type and mutant forms of Grb2. Lysates were prepared from cells transfected with DNA constructs expressing Caswt, in the presence or absence of coexpressed v-Src, plus the indicated forms of Grb2. Lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-Grb2 antibody, and the immunoprecipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Cas2 antibody (upper panel) or anti-Grb2 antibody (lower panel). (C) Association between Cas and Grb2 in vitro. Cas was immunoprecipitated with anti-Cas2 antibody from lysates of cells transfected with DNAs expressing Cas and/or v-Src. Samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to an Immobilon-P membrane, and probed with GST fusion proteins containing wild-type or mutant forms of Grb2. Bound GST-Grb2 was detected with anti-GST antibody. (D) Effects of Y→F mutations on SRE activation by Cas and the association of Cas with Grb2. Upper panel, cells were cotransfected with the SRE reporter construct pSREtkLuc and DNA constructs expressing HA-Cas point mutants and v-Src as indicated. Luciferase activity was analyzed as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Lower panel, cells were cotransfected with DNA constructs expressing Grb2wt, v-Src, and the Cas point mutants as indicated. Grb2 was immunoprecipitated and coprecipitating Cas detected by immunoblotting with anti-HA antibody.

To determine whether Cas and Grb2 can associate directly, Cas immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and blotted onto a transfer membrane which was then incubated with GST fusions of wild-type or mutant forms of Grb2; bound fusion proteins were detected by immunoblot analysis using anti-GST antibody. GST-Grb2 and GST-Grb2K36,193 both bound to electrophoretically retarded (tyrosine-phosphorylated) Cas from lysates of cells coexpressing Src (Fig. 6C, panels a and c). Such binding was not detected when Cas was immunoprecipitated from cells not coexpressing Src. The GST-Grb2 proteins also bound, probably nonspecifically, to the unshifted (non-tyrosine-phosphorylated) form of Cas. GST-Grb2K86 and GST were unable to bind the shifted form of Cas (Fig. 6C, panels b and d). Thus, Grb2 appears to directly associate with tyrosine-phosphorylated Cas through its SH2 domain.

Three consensus Grb2 SH2 domain binding sites containing a YXNX motif (45) are present in Cas at tyrosine residues 106, 751, and 913 (YDNV, YENS, and YSNL, respectively). To determine which of these sites mediate direct association between Grb2 and Cas and whether this association is important for signaling to the SRE, we generated HA-tagged Cas constructs with phenylalanine in place of one or all three of these tyrosine residues. Coimmunoprecipitation experiments were carried out to determine the effects of these mutations on the association between Grb2 and Cas. Cells coexpressing v-Src, Grb2, and wild-type or mutant forms of Cas were lysed, and immunoprecipitates were prepared with anti-Grb2 antibody; the immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and subjected to immunoblotting with anti-HA antibody to detect coprecipitating HA-Cas. Neither the F751 nor the triple-point mutant (F106,751,913) of Cas coprecipitated with Grb2 (Fig. 6D, lower panel). The SH2 domain of Grb2 therefore associates with Cas through Y751. However, in the reporter assay, coexpression of v-Src with Cas F751 or the Cas triple-point mutant induced similar levels of luciferase activity as Caswt (Fig. 6D). Taken together, these data imply that the direct association between Cas and Grb2 is not responsible for Cas-mediated signaling to the SRE. Thus, Cas-dependent signaling to the SRE is likely be mediated by another Cas/Grb2 pathway.

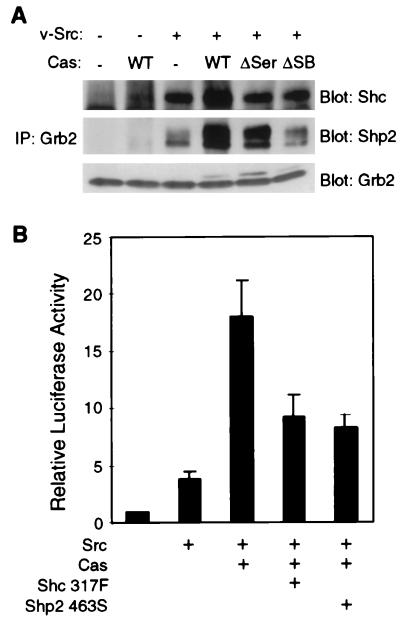

Shc and Shp-2 promote Cas-mediated signaling to the SRE.

The association of Grb2 with Shc or the tyrosine phosphatase Shp-2 has been implicated in activation of the Ras/Erk MAPK pathway (24, 34, 39, 44). We therefore carried out coimmunoprecipitation experiments to examine the effect of Cas and v-Src expression on the association of Grb2 with Shc and Shp-2. Grb2 immunoprecipitates were prepared from lysates of cells cotransfected with Grb2, v-Src, and Cas DNAs. The levels of coprecipitating Shc and Shp-2 were determined by immunoblot analysis. v-Src expression induced the association of Grb2 with both Shp-2 and the 52-kDa form of Shc, whereas the expression of Cas alone did not (Fig. 7A). Coexpression of Cas with v-Src enhanced the amount of coprecipitating Shp-2 and Shc. To determine if the formation of these complexes correlated with SRE activation, we coexpressed v-Src with CasΔSer and CasΔSB and assessed the association of Grb2 with Shc and Shp-2 by coimmunoprecipitation. Coexpression of either Cas mutant with v-Src did not enhance the association between Shc and Grb2 over the level observed upon expression of v-Src alone. Coprecipitation of Shp-2 was somewhat reduced by the ΔSer mutation. CasΔSB expression did not enhance the level of coprecipitating Shp-2 over the level observed upon expression of Src alone. Thus, the formation of Grb2-Shc and Grb2–Shp-2 complexes appears to parallel SRE activation. We could not detect any association of Cas with either Shc or Shp-2 by coimmunoprecipitation experiments (data not shown), suggesting that Grb2 does not form a ternary complex with both Cas and Shc or Shp-2. Since the serine-rich region of Cas contains a putative 14-3-3 binding motif and affects Grb2 association with Shc and Shp-2, we carried out coimmunoprecipitation experiments to determine whether 14-3-3 proteins associate with Grb2, which we observed also contains putative 14-3-3 binding motifs. These coimmunoprecipitation assays revealed that Grb2 associates with 14-3-3 proteins in vivo (data not shown). 14-3-3 proteins may therefore play a role in signaling from Cas to Grb2. These data suggest that coexpression of Cas and Src induces the association of Grb2 with Shc and Shp-2 by some indirect mechanism. To determine if Shc and Shp-2 play a role in Cas-mediated SRE activation, dominant-negative mutants of each protein were incorporated into the reporter assay. Src and Cas were coexpressed with either Shc 317F, in which a Y→F mutation blocks binding of the Grb2 SH2 domain, or Shp-2 463S, in which a C→S mutation renders Shp-2 catalytically inactive. Coexpression of either mutant significantly reduced the levels of SRE activation by Src and Cas (Fig. 7B).

FIG. 7.

Shc and Shp-2 promote Cas-mediated signaling to the SRE. (A) Grb2 was immunoprecipitated (IP) from lysates of cells transfected with DNA constructs expressing Grb2, v-Src, and wild-type or mutant (ΔSer or ΔSB) forms of Cas. Coimmunoprecipitating Shc (upper panel) and Shp-2 (middle panel) were detected by immunoblot analysis using anti-Shc and anti-Shp-2 antibodies. The immunoprecipitated Grb2 was detected by immunoblot analysis with anti-Grb2 antibody (lower panel). (B) The reporter assay was performed on cells cotransfected with constructs encoding v-Src, Cas, and mutants of Shc (Y317F) or Shp-2 (C463S) as indicated.

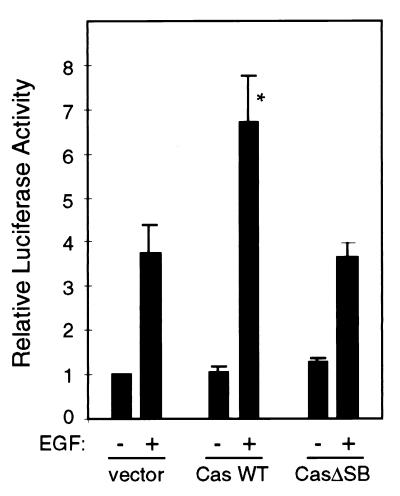

Cas enhances EGF-stimulated activation of the SRE.

Various mitogens such as EGF induce immediate-early responses and phosphorylation of Cas. We tested the ability of Cas to mediate EGF-induced SRE activation. Cells were cotransfected with the SRE-luciferase reporter construct and either an empty vector, Caswt, or CasΔSB DNA. After serum starvation, cells remained unstimulated or were stimulated with EGF. Overexpression of Caswt enhanced EGF-induced SRE activation (Fig. 8). Expression of CasΔSB did not enhance SRE activation, suggesting that association of Cas with Src is required for this enhancement. The modest level of SRE activation upon overexpression of Cas may reflect the ability of endogenous Cas to support Cas-dependent signaling or the fact that multiple signaling pathways mediate the EGF response (4, 31, 53).

FIG. 8.

Role of Cas in EGF-induced SRE activation. Cells were cotransfected with pSREtkLuc and either vector DNA (pSSRα) or constructs expressing Caswt or CasΔSB. Twenty hours after transfection, the cells were serum starved for 24 h. Cells were either left unstimulated or stimulated with EGF (10 ng/ml) for 5 h. The cells were lysed and luciferase activity determined. ∗, P = 0.01.

DISCUSSION

Mitogenic stimuli and v-Src expression both result in transcriptional activation of IEGs through specific transcriptional control elements. Both stimuli also enhance the tyrosine phosphorylation of Cas, a docking protein that interacts with multiple signaling molecules. We hypothesized that Cas may mediate signaling to the transcriptional control elements that regulate the expression of IEGs. The findings reported here demonstrate that Cas cooperates with Src in inducing SRE-dependent transcriptional activation and that this activation occurs via a Grb2/Ras/Mek/MAPK pathway. The cooperation between Cas and Src required the SB region of Cas and the kinase activity of Src, indicating that signaling requires the association of Cas with catalytically active Src.

Surprisingly, deletion of the SD did not affect SRE activation. However, deletion of the serine-rich region in Cas did not affect the association of Cas with Src but significantly decreased signaling to the SRE. The function of this region remains unclear. It has previously been shown that Cas becomes serine phosphorylated in cells expressing v-Src (21). Phosphorylation of the serine residues may create a binding site for other proteins or modulate the charge and conformation of Cas. This region contains a motif which upon serine phosphorylation would form a binding site for 14-3-3 proteins. 14-3-3 proteins form homo- and heterodimeric complexes and are implicated in mediating interactions between a wide array of signaling molecules (19). Recently Cas was also shown to associate with 14-3-3 proteins (11), although we could not detect such an association, possibly due to the limited sensitivity of our assay. We did identify putative 14-3-3 binding motifs in Grb2 and have demonstrated that the two proteins are associated in vivo. These observations suggest a role for 14-3-3 proteins in Cas-dependent signaling to the SRE, perhaps in mediating signaling from Cas to Grb2. We are currently studying the possible requirements for 14-3-3 proteins in signaling by Cas.

Another segment of Cas that appears to be involved in signaling to the SRE is the SH3 domain. When CasΔSH3 was expressed with v-Src, it signaled to the SRE almost three times as strongly as Caswt. The SH3 domain of Cas mediates its association with the tyrosine phosphatases PTP1B and PTP-PEST, which both dephosphorylate Cas (12, 25). Thus, one function of the SH3 domain may be to downregulate signaling by mediating the association of Cas with tyrosine phosphatases. Consistent with this, we noticed that in the presence of v-Src, CasΔSH3 was more hyperphosphorylated than Caswt. Interestingly, coexpression of PTP1B inhibited the transformation of 3Y1 fibroblasts by v-Src and reduced the tyrosine phosphorylation of Cas; this inhibition did not occur upon coexpression of a PTP1B mutant defective in Cas association (26). Thus, the serine-rich region of Cas promotes signaling, while the SH3 domain downregulates it.

A possible mechanism of signaling to the SRE by Cas is through FAK. Cas is known to be associated with FAK, and FAK has been implicated in the activation of the Erk MAPK pathway via a direct association with Grb2 (42, 43). These observations raise the possibility that association of Cas with FAK may somehow facilitate Erk activation. One mode of association between Cas and FAK is direct binding mediated by the Cas SH3 domain to a proline-rich region in FAK. However, expression of a Cas mutant lacking the SH3 domain did not decrease signaling to the SRE, suggesting that direct binding of Cas to FAK is not required for signaling. An alternative mode of interaction between Cas and FAK has been suggested by the observation that in Src-deficient cells Cas-FAK association is enhanced by overexpression of c-Src or a truncated form of Src lacking the kinase domain. Schlaepfer et al. have proposed that Src may bridge these two proteins by binding FAK through its SH2 domain and Cas through its SH3 domain (41). Yet, this mode of association does not appear to be responsible for SRE activation, since coimmunoprecipitation experiments did not reveal an increase in Cas-FAK association when v-Src was expressed (13a). Furthermore, the kinase-dead mutant of v-Src, which would mimic the truncated form of c-Src, did not signal to the SRE. These data imply that Cas-mediated signaling to the SRE is FAK independent.

Cas-mediated signaling to the SRE is transduced by the Ras/Mek/Erk pathway. Cas enhanced Ras and Erk activation induced by v-Src, while dominant-negative mutants of Ras and Mek1 abrogated Cas-dependent signaling to the SRE. These data are in agreement with the finding of Qureshi et al. that v-Src-induced activation of the SRE requires Ras and Raf (37). Dominant-negative Grb2 mutants blocked Cas-dependent activation of Ras and Erk2 and signaling to the SRE, indicating that signaling from Cas to the Ras/MAPK pathway is transmitted by Grb2. In cells coexpressing v-Src, Grb2 was found to directly associate with Cas via an interaction between the SH2 domain of Grb2 and Cas pY751. However, a Y751F mutation in Cas blocked the association of Cas with Grb2 but had no detectable effects on SRE activation. The role of this Cas-Grb2 complex remains unclear, although it might contribute to activation of the SRE at quantitatively insignificant levels. Overexpression of Cas did, however, enhance the association of Grb2 with two signaling molecules, Shc and Shp-2. Binding of Grb2 to these proteins has been implicated in the activation of the Ras/Erk MAPK pathway (24, 34, 39, 44). We could not detect association of Cas with either Shc or Shp-2, implying that the effect on Grb2 complex formation is indirect. Expression of Shc and Shp-2 mutants significantly reduced Cas-mediated SRE activation, indicating that they are involved in the signaling pathway. These data suggest that Grb2 is downstream of Cas and transmits signaling to Ras.

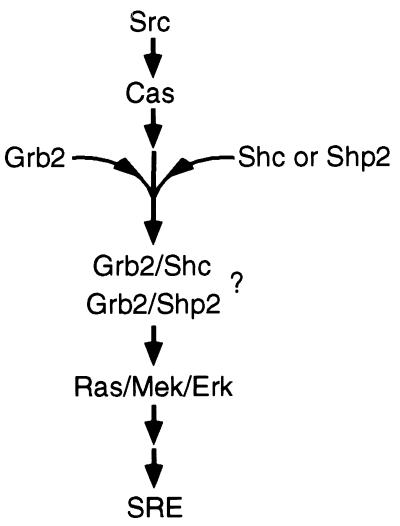

We propose a model in which Cas mediates a pathway that results in SRE-dependent transcriptional activation induced by Src (Fig. 9). Cas first associates with Src. The kinase-active Src may then phosphorylate Cas and/or a proximal substrate. This initiates a yet unidentified signal leading to the association of Grb2 with Shc and Shp-2. Formation of either complex may lead to activation of Ras and the Erk MAPK cascade, which in turn signals to the SRE. The Cas-dependent signaling pathway activated in cells expressing v-Src may also be activated upon mitogen stimulation. Several mitogenic stimuli have been shown to signal to the SRE and enhance the level of tyrosine phosphorylation of Cas. Src may itself participate in the EGF response (27, 55). We did observe a modest increase in EGF-induced SRE activation in cells overexpressing Caswt but not in cells expressing a CasΔSB mutant. Cas may, therefore, mediate Src-dependent transcriptional regulation in response to various stimuli.

FIG. 9.

Model for Cas-mediated activation of the SRE. Kinase-active Src directly binds to Cas. This association leads to the coupling of Grb2 with Shc and Shp-2 by yet undetermined means. The induced association of Grb2 with Shc and/or Shp-2 may signal to the Ras/Mek/Erk pathway. Activation of the Erk MAPK pathway can then lead to SRE-dependent transcriptional activation. Other Src-dependent signaling pathways that are not shown may also result in activation of Ras and signaling to SREs.

Several studies have suggested that transcriptional activation is required for complete transformation of cells by v-Src (10, 30, 46, 51). Honda et al. demonstrated that Cas-deficient mouse embryo fibroblasts are not fully transformed by v-Src (17), while Auvinen et al. have shown that expression of antisense Cas partially reverts the morphological transformation of rat fibroblasts by v-Src (3). Thus, one can speculate that Cas-mediated transcriptional activation of certain genes may contribute to transformation by v-Src. However, it is likely that Cas has additional biochemical functions which are important for oncogenic transformation or mitogenic responses. Moreover, many other proteins have been implicated in activation of the Ras/MAPK pathway. The complex signaling network which converges on Ras remains to be fully elucidated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank H. Hirai, D. Foster, B. Mayer, M. Weber, N. Ahn, G. S. Feng, T. Pawson, and R. Davis for constructs and reagents. We also thank F. Hofer, M. Gossen, and members of the Martin lab for helpful discussions and Y. Hsu for technical assistance.

This work was supported by NIH grant CA17542 and by the facilities of the University of California Cancer Research Laboratory.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aftab D T, Kwan J, Martin G S. Ras-independent transformation by v-Src. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3028–3033. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexandropoulos K, Baltimore D. Coordinate activation of c-Src by SH3- and SH2-binding sites on a novel p130Cas-related protein, Sin. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1341–1355. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.11.1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Auvinen M, Paasinen-Sohns A, Hirai H, Andersson L C, Hölttä E. Ornithine decarboxylase- and Ras-induced cell transformations: reversal by protein tyrosine kinase inhibitors and role of pp130CAS. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:6513–6525. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.12.6513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bennett A M, Hausdorff S F, O’Reilly A M, Freeman R M, Neel B G. Multiple requirements for SHPTP2 in epidermal growth factor-mediated cell cycle progression. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:1189–1202. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.3.1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brugge J S. Casting light on focal adhesions. Nat Genet. 1998;19:309–311. doi: 10.1038/1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burnham M R, Harte M T, Richardson A, Parsons J T, Bouton A H. The identification of p130cas-binding proteins and their role in cellular transformation. Oncogene. 1996;12:2467–2472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cahill M A, Janknecht R, Nordheim A. Signalling pathways: jack of all cascades. Curr Biol. 1996;6:16–19. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00410-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casamassima A, Rozengurt E. Tyrosine phosphorylation of p130(cas) by bombesin, lysophosphatidic acid, phorbol esters, and platelet-derived growth factor. Signaling pathways and formation of a p130(cas)-Crk complex. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:9363–9370. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.14.9363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curto M, Carrero A, Frankel P, Foster D A. Activation of gene expression by a non-transforming unmyristylated-SH3-deleted mutant of Src is dependent upon Tyr-527. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;239:681–687. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frame M C, Simpson K, Fincham V J, Crouch D H. Separation of v-Src-induced mitogenesis and morphological transformation by inhibition of AP-1. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;5:1177–1184. doi: 10.1091/mbc.5.11.1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garcia-Guzman M, Dolfi F, Russello M, Vuori K. Cell adhesion regulates the interaction between the docking protein p130(Cas) and the 14-3-3 proteins. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:5762–5768. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.9.5762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garton A J, Burnham M R, Bouton A H, Tonks N K. Association of PTP-PEST with the SH3 domain of p130cas; a novel mechanism of protein tyrosine phosphatase substrate recognition. Oncogene. 1997;15:877–885. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grammer T C, Blenis J. Evidence for MEK-independent pathways regulating the prolonged activation of the ERK-MAP kinases. Oncogene. 1997;14:1635–1642. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13a.Hakak, Y., and G. S. Martin. Unpublished results.

- 14.Harte M T, Hildebrand J D, Burnham M R, Bouton A H, Parsons J T. p130Cas, a substrate associated with v-Src and v-Crk, localizes to focal adhesions and binds to focal adhesion kinase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:13649–13655. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.23.13649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herschman H R. Primary response genes induced by growth factors and tumor promoters. Annu Rev Biochem. 1991;60:281–319. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.60.070191.001433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hofer F, Berdeaux R, Martin G S. Ras-independent activation of Ral by a Ca(2+)-dependent pathway. Curr Biol. 1998;8:839–842. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70327-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Honda H, Oda H, Nakamoto T, Honda Z, Sakai R, Suzuki T, Saito T, Nakamura K, Nakao K, Ishikawa T, Katsuki M, Yazaki Y, Hirai H. Cardiovascular anomaly, impaired actin bundling and resistance to Src-induced transformation in mice lacking p130(Cas) Nat Genet. 1998;19:361–365. doi: 10.1038/1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu Q, Milfay D, Williams L T. Binding of NCK to SOS and activation of ras-dependent gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:1169–1174. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.3.1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones D H, Ley S, Aitken A. Isoforms of 14-3-3 protein can form homo- and heterodimers in vivo and in vitro: implications for function as adapter proteins. FEBS Lett. 1995;368:55–58. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00598-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jove R, Hanafusa H. Cell transformation by the viral src oncogene. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1987;3:31–56. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.03.110187.000335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kanner S B, Reynolds A B, Wang H C, Vines R R, Parsons J T. The SH2 and SH3 domains of pp60src direct stable association with tyrosine phosphorylated proteins p130 and p110. EMBO J. 1991;10:1689–1698. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07693.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kirsch K H, Georgescu M M, Hanafusa H. Direct binding of p130(Cas) to the guanine nucleotide exchange factor C3G. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:25673–25679. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.40.25673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Law S F, Estojak J, Wang B, Mysliwiec T, Kruh G, Golemis E A. Human enhancer of filamentation 1, a novel p130cas-like docking protein, associates with focal adhesion kinase and induces pseudohyphal growth in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:3327–3337. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.7.3327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li W, Nishimura R, Kashishian A, Batzer A G, Kim W J, Cooper J A, Schlessinger J. A new function for a phosphotyrosine phosphatase: linking GRB2-Sos to a receptor tyrosine kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:509–517. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.1.509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu F, Hill D E, Chernoff J. Direct binding of the proline-rich region of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B to the Src homology 3 domain of p130(Cas) J Biol Chem. 1996;271:31290–31299. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.49.31290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu F, Sells M A, Chernoff J. Transformation suppression by protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B requires a functional SH3 ligand. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:250–259. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.1.250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luttrell D K, Luttrell L M, Parsons S J. Augmented mitogenic responsiveness to epidermal growth factor in murine fibroblasts that overexpress pp60c-src. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:497–501. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.1.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manié S N, Astier A, Haghayeghi N, Canty T, Druker B J, Hirai H, Freedman A S. Regulation of integrin-mediated p130(Cas) tyrosine phosphorylation in human B cells. A role for p59(Fyn) and SHP2. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:15636–15641. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.25.15636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsuda M, Hashimoto Y, Muroya K, Hasegawa H, Kurata T, Tanaka S, Nakamura S, Hattori S. CRK protein binds to two guanine nucleotide-releasing proteins for the Ras family and modulates nerve growth factor-induced activation of Ras in PC12 cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:5495–5500. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.8.5495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meijne A M, Ruuls-Van Stalle L, Feltkamp C A, McCarthy J B, Roos E. v-src-induced cell shape changes in rat fibroblasts require new gene transcription and precede loss of focal adhesions. Exp Cell Res. 1997;234:477–485. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Migliaccio E, Mele S, Salcini A E, Pelicci G, Lai K M, Superti-Furga G, Pawson T, Di Fiore P P, Lanfrancone L, Pelicci P G. Opposite effects of the p52shc/p46shc and p66shc splicing isoforms on the EGF receptor-MAP kinase-fos signalling pathway. EMBO J. 1997;16:706–736. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.4.706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morgenstern J P, Land H. Advanced mammalian gene transfer: high titre retroviral vectors with multiple drug selection markers and a complementary helper-free packaging cell line. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:3587–3596. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.12.3587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakamoto T, Sakai R, Ozawa K, Yazaki Y, Hirai H. Direct binding of C-terminal region of p130Cas to SH2 and SH3 domains of Src kinase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:8959–8965. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.15.8959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Noguchi T, Matozaki T, Horita K, Fujioka Y, Kasuga M. Role of SH-PTP2, a protein-tyrosine phosphatase with Src homology 2 domains, in insulin-stimulated Ras activation. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:6674–6682. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.10.6674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ojaniemi M, Vuori K. Epidermal growth factor modulates tyrosine phosphorylation of p130Cas. Involvement of phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase and actin cytoskeleton. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:25993–25998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Polte T R, Hanks S K. Interaction between focal adhesion kinase and Crk-associated tyrosine kinase substrate p130Cas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:10678–10682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qureshi S A, Alexandropoulos K, Rim M, Joseph C K, Bruder J T, Rapp U R, Foster D A. Evidence that Ha-Ras mediates two distinguishable intracellular signals activated by v-Src. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:17635–17639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qureshi S A, Cao X M, Sukhatme V P, Foster D A. v-Src activates mitogen-responsive transcription factor Egr-1 via serum response elements. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:10802–10806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rozakis-Adcock M, McGlade J, Mbamalu G, Pelicci G, Daly R, Li W, Batzer A, Thomas S, Brugge J, Pelicci P G, et al. Association of the Shc and Grb2/Sem5 SH2-containing proteins is implicated in activation of the Ras pathway by tyrosine kinases. Nature. 1992;360:689–692. doi: 10.1038/360689a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sakai R, Iwamatsu A, Hirano N, Ogawa S, Tanaka T, Mano H, Yazaki Y, Hirai H. A novel signaling molecule, p130, forms stable complexes in vivo with v-Crk and v-Src in a tyrosine phosphorylation-dependent manner. EMBO J. 1994;13:3748–3756. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06684.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schlaepfer D D, Broome M A, Hunter T. Fibronectin-stimulated signaling from a focal adhesion kinase–c-Src complex: involvement of the Grb2, p130cas, and Nck adaptor proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1702–1713. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.3.1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schlaepfer D D, Hanks S K, Hunter T, van der Geer P. Integrin-mediated signal transduction linked to Ras pathway by GRB2 binding to focal adhesion kinase. Nature. 1994;372:786–791. doi: 10.1038/372786a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schlaepfer D D, Jones K C, Hunter T. Multiple Grb2-mediated integrin-stimulated signaling pathways to ERK2/mitogen-activated protein kinase: summation of both c-Src- and focal adhesion kinase-initiated tyrosine phosphorylation events. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2571–2585. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.5.2571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Skolnik E Y, Batzer A, Li N, Lee C H, Lowenstein E, Mohammadi M, Margolis B, Schlessinger J. The function of GRB2 in linking the insulin receptor to Ras signaling pathways. Science. 1993;260:1953–1955. doi: 10.1126/science.8316835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Songyang Z, Shoelson S E, McGlade J, Olivier P, Pawson T, Bustelo X R, Barbacid M, Sabe H, Hanafusa H, Yi T, Ren R, Baltimore D, Ratnofsky S, Feldman R A, Cantley L C. Specific motifs recognized by the SH2 domains of Csk, 3BP2, fps/fes, GRB-2, HCP, SHC, Syk, and Vav. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:2777–2785. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.4.2777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Suzuki T, Murakami M, Onai N, Fukuda E, Hashimoto Y, Sonobe M H, Kameda T, Ichinose M, Miki K, Iba H. Analysis of AP-1 function in cellular transformation pathways. J Virol. 1994;68:3527–3535. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.6.3527-3535.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takenawa T, Miki H, Matuoka K. Signaling through Grb2/Ash-control of the Ras pathway and cytoskeleton. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1998;228:325–342. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-80481-6_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tanaka M, Gupta R, Mayer B J. Differential inhibition of signaling pathways by dominant-negative SH2/SH3 adapter proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:6829–6837. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.12.6829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tanaka S, Ouchi T, Hanafusa H. Downstream of Crk adaptor signaling pathway: activation of Jun kinase by v-Crk through the guanine nucleotide exchange protein C3G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:2356–2361. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thomas S M, Brugge J S. Cellular functions regulated by Src family kinases. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1997;13:513–609. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Turkson J, Bowman T, Garcia R, Caldenhoven E, De Groot R P, Jove R. Stat3 activation by Src induces specific gene regulation and is required for cell transformation. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2545–2552. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.5.2545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vuori K, Hirai H, Aizawa S, Ruoslahti E. Induction of p130cas signaling complex formation upon integrin-mediated cell adhesion: a role for Src family kinases. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:2606–2613. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.6.2606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang Z, Glück S, Zhang L, Moran M F. Requirement for phospholipase C-γ1 enzymatic activity in growth factor-induced mitogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:590–597. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.1.590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.White B A. PCR protocols: current methods and applications. Totowa, N.J: Humana Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wilson L K, Luttrell D K, Parsons J T, Parsons S J. pp60c-src tyrosine kinase, myristylation, and modulatory domains are required for enhanced mitogenic responsiveness to epidermal growth factor seen in cells overexpressing c-src. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:1536–1544. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.4.1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]