Abstract

Pitx2 is a newly described bicoid-like homeodomain transcription factor that is defective in Rieger syndrome and shows a striking leftward developmental asymmetry. We have previously shown that Pitx2 (also called Ptx2 and RIEG) transactivates a reporter gene containing a bicoid enhancer and synergistically transactivates the prolactin promoter in the presence of the POU homeodomain protein Pit-1. In this report, we focused on the C-terminal region which is mutated in some Rieger patients and contains a highly conserved 14-amino-acid element. Deletion analysis of Pitx2 revealed that the C-terminal 39-amino-acid tail represses DNA binding activity and is required for Pitx2-Pit-1 interaction and Pit-1 synergism. Pit-1 interaction with the Pitx2 C terminus masks the inhibitory effect and promotes increased DNA binding activity. Interestingly, cotransfection of an expression vector encoding the C-terminal 39 amino acids of Pitx2 specifically inhibits Pitx2 transactivation activity. In contrast, the C-terminal 39-amino-acid peptide interacts with Pitx2 to increase its DNA binding activity. These data suggest that the C-terminal tail intrinsically inhibits the Pitx2 protein and that this inhibition can be overcome by interaction with other transcription factors to allow activation during development.

Human Pitx2 (also called Ptx2 and RIEG) is a member of the bicoid-like homeobox transcription factor family (30). The homeobox gene family has been extensively studied, and the members play fundamental roles in the genetic control of development, including pattern formation and determination of cell fate (for reviews, see references 11, 18, and 23). The homeodomain of Pitx2 has a high degree of homology to another Bicoid-like homeodomain protein, P-OTX/Ptx1/Pitx1 (19, 36), and to Pitx3 (31) and, to a lesser extent, unc-30, Otx-1, Otx-2, otd, and goosecoid (30). The homeobox proteins contain a 60-amino-acid homeodomain that binds DNA. Pitx2 contains a lysine at position 50 in the third helix of the homeodomain that is characteristic of the Bicoid-related proteins (14, 17, 33). This lysine residue selectively recognizes the 3′CC dinucleotide adjacent to the TAAT core (11, 40). Consistent with this phylogenetic relationship, we have demonstrated that Pitx2 can bind the DNA sequence 5′TAATCC3′ (2), which is also recognized by the Bicoid protein (8).

The Pitx2 gene has point mutations in Rieger syndrome patients (30). Rieger syndrome was first defined as a genetic disorder in 1935 (27). It is an autosomal dominant human disorder characterized by dental hypoplasia, mild craniofacial dysmorphism, ocular anterior chamber anomalies causing glaucoma, and umbilical stump abnormalities. The dental hypoplasia is manifested as missing, small, and/or malformed teeth (30). Other features associated with Rieger syndrome include abnormal cardiac, limb, and anterior pituitary development. We have recently reported that point mutations in the homeodomain of Pitx2 associated with Rieger syndrome affect DNA binding and transactivation activities (2). Another interesting feature of Pitx2 is that it displays left-right asymmetric expression during early embryogenesis (1, 21, 26, 28, 41). Pitx2 is unique because it has a function in developmental left-right asymmetry and is not simply a marker of leftward organ development. In the chick embryo, asymmetric expression of Pitx2 was detected at stage 7 and restricted to the left-sided lateral mesoderm, the left-sided precardiac mesoderm, and the left half epimyocardium of the primitive heart (1). Pitx2 is also expressed in the left heart and gut of mouse and Xenopus embryos (28). Recently, several investigators have shown that Pitx2 is involved in a Lefty signaling pathway and is transcriptionally responsive to sonic hedgehog and nodal (21, 26, 28, 41).

Pitx2 expression in Rathke’s pouch suggests that this new family also plays an important role in anterior pituitary gland development. Mouse Pitx2 was independently cloned and shown to be a potential regulator of anterior structure formation (10). Both Pitx2 and the related P-OTX protein were shown to interact with the POU homeodomain protein Pit-1 (2, 36). Pit-1 is an important transcription factor that regulates pituitary cell differentiation and expression of the thyroid-stimulating hormone, the growth hormone, and prolactin (34). The C terminus of P-OTX was further shown to bind the family of LIM domain-associated cofactors, P-Lim and CLIM 1a (3). These results suggest that protein-protein interactions may also occur in the corresponding region of Pitx2. While most of the C-terminal sequences of P-OTX and Pitx2 are divergent, Pitx2 has a 14-amino-acid conserved sequence found in P-OTX. This sequence was identified in other homeodomain proteins and speculated to be involved in protein-protein interactions (30).

The C-terminal tails of homeodomain proteins have been shown to be involved in autoregulation (7, 9, 15, 35). Interestingly, in some Rieger syndrome patients, Pitx2 has a truncated C-terminal tail. Thus, we wanted to determine the function of the Pitx2 C-terminal tail. We report that Pitx2 activity is regulated by its C-terminal tail. In this study, we have identified a small region of Pitx2 that inhibits DNA binding and is involved in protein-protein interactions. Protein binding to this region stimulates Pitx2 DNA binding and transcriptional activation, presumably by masking the inhibitory domain. This repression is relieved when the Pit-1 transcription factor binds to the Pitx2 C terminus. We propose a novel mechanism for the regulation of Pitx2 during development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression and purification of GST-Pitx2 fusion proteins.

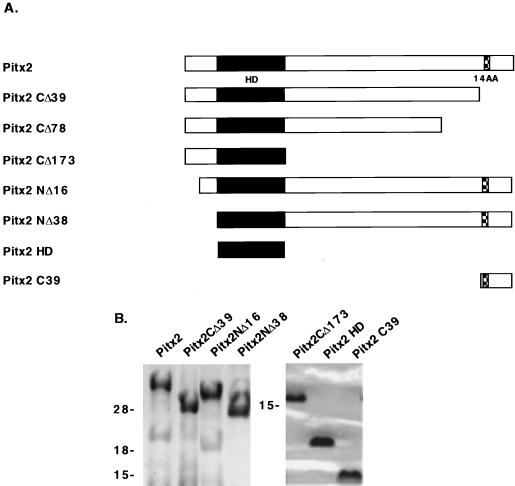

The human Pitx2 and deletion constructs were PCR amplified from a cDNA clone provided by Elena Semina and Jeffery Murray (Department of Pediatrics, University of Iowa) as previously described (2). A schematic of the wild-type Pitx2 and the different truncations are shown in Fig. 1. To make plasmid pGST-Pitx2CΔ39, which has the C-terminal 39 amino acids deleted, an antisense primer (nucleotides 1280 to 1262) with a unique NotI site (5′GTACTGCAGATGCGGCCGCGTTACACGTGTCCCTATA3′) was used with the previous 5′ sense primer (2). For plasmid pGST-Pitx2CΔ78, a C-terminal truncation with the last 78 amino acids deleted, an antisense primer (nucleotides 1163 to 1145) with a NotI site (5′GTACTGCAGATGCGGCCGCGAGACTGGAGCCCGGGAC3′) was used with the previous 5′ sense primer to make the truncated DNA product. For plasmid pGST-Pitx2CΔ173, which has the C-terminal 173 amino acids deleted, an antisense primer (nucleotides 881 to 863) with a unique NotI site (5′GTACTGCAGATGCGGCCGCGCGCTCCCTCTTTCTCCA3′) was used with the previous 5′ sense primer. For plasmid pGST-Pitx2NΔ16, which has the N-terminal 16 amino acids deleted, the sense primer (nucleotides 632 to 650) with a unique SalI site (5′CGTCGTCGACTAAAGATAAAAGCCAGCAG3′) and the previous antisense primer used to make pGST-Pitx2 (2) were used. pGST-Pitx2NΔ38 was made by using the sense primer (nucleotides 699 to 720) containing a unique SalI site (5′GCGGGATCCCGAACGGGGAAATGCAAAGGCGGCAGCGGACTCAC3′) and the antisense primer for pGST-Pitx2. To make pGST-Pitx2HD, the pGST-Pitx2NΔ38 sense primer and the pGST-Pitx2CΔ173 antisense primers were used. The plasmids pGST-Pitx2C39, pGST-Pitx2C78, and pGST-Pitx2C173 were made by using the above-mentioned wild-type antisense primer and the sense primers starting at nucleotides 1280, 1163, and 881, respectively, with a unique SalI site 5′ of the Pitx2 sequence. The PCR profile consisted of 94°C for 2 min, 60°C for 2 min, and 72°C for 3 min for 30 cycles with Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene). The PCR products were digested with SalI and NotI, cloned into pGex6P-2 (Pharmacia Biotech), and confirmed by DNA sequencing. The plasmids were transformed into BL21 cells. Protein was isolated as previously described (2). Pitx2 proteins were cleaved from the glutathione S-transferase (GST) moiety by using 80 U of PreScission protease (Pharmacia Biotech) per ml of glutathione Sepharose. Purified proteins used in the binding assays are shown in Fig. 1B. The Sepharose beads were spun down, and the supernatant was aliquoted and stored at −80°C in 10% glycerol. The cleaved proteins were analyzed on sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gels and quantitated by the Bradford protein assay (Bio-Rad).

FIG. 1.

Schematic of Pitx2 constructs. (A) Proteins used in this study with the homeodomain (HD) and the conserved 14-amino-acid (14AA) C-terminal element. (B) The proteins were expressed in bacteria as GST fusions, and the GST moiety was cleaved from the Pitx2 proteins with PreScission protease. Equal molar amounts of each protein (∼5 μg) were resolved on an SDS–12.5% polyacrylamide glycine gel (left panel) or an SDS–10% polyacrylamide tricine gel (right panel). Proteins were visualized by Coomassie blue staining. Molecular mass markers (in kilodaltons) are shown to the left of each panel.

EMSA.

Complementary oligonucleotides containing a Drosophila bicoid site (8) with flanking partial BamHI ends were annealed and filled with Klenow polymerase to generate 32P-labeled probes for electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs), as previously described (39). For standard binding assays, the oligonucleotide (1.0 pmol) was incubated in a 20-μl reaction mixture containing binding buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 5% glycerol, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 1 mM dithiothreitol), 0.1 μg of poly(dI-dC), 80 to 160 ng of Pitx2, and Pitx2 truncated proteins on ice for 15 min. For competition assays, unlabeled double-stranded end-filled oligonucleotides were preincubated with the protein for 15 min on ice prior to addition of the probe. Sequences of the bicoid probe and competitor oligonucleotides, all with flanking partial BamHI ends, have been previously described (2). Pit-1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) (200 ng) was added to the EMSA experiments prior to addition of the probe. The samples were electrophoresed for 2 h at 250 V on an 8% polyacrylamide gel with 0.25× TBE (22.5 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.5], 28 mM boric acid, 0.7 mM EDTA) at 4°C following preelectrophoresis of the gels for 1 h at 200 V. The dried gels were visualized by exposure to autoradiographic film. For quantitative analyses to establish binding constants and relative competitions, the amounts of bound and free radioactive probes were measured from dried gels with an InstantImager (Packard). For determination of the amount of binding competition, the ratio of bound to free probes was normalized to the absence of competitor DNA.

In vitro Pit-1 binding and Western blot analyses.

Immobilized GST fusion proteins were prepared as described above and suspended in binding buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 5% glycerol, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1% milk, and 400 μg of ethidium bromide per ml). Pit-1 (Santa Cruz) (40 ng) was added to 10 μg of immobilized GST fusion proteins or GST in a total volume of 100 μl and incubated for 30 min at 4°C. The beads were pelleted and washed four times with 200 μl of binding buffer. The bound Pit-1 was eluted by boiling in SDS sample buffer and was separated on an SDS–12.5% polyacrylamide gel. Following SDS gel electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride filters (Millipore), immunoblotted, and detected by using Pit-1 antibody (Santa Cruz) and enhanced chemiluminescence reagents from Amersham.

Expression and reporter constructs.

Expression plasmids containing the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter linked to the Pitx2 and Pitx2 truncated DNA were constructed in pcDNA 3.1 MycHisC (Invitrogen). The c-myc epitope is in frame with the C terminus of Pitx2, allowing detection of the expressed protein by the c-myc antibody. The N-terminally deleted plasmids contain the Pitx2 translation initiation sequences. The bicoid-thymidine kinase (TK)-luc reporter plasmid has bicoid elements (underlined) (5′gatccGCACGGCCCATCTAATCCCGTGg3′ annealed to 5′gatccCACGGGATTAGATGGGCCGTGCg3′) ligated into the unique BamHI site (lowercased) upstream of the TK promoter in the TK-luc plasmid (39). Bicoid-TK-luc contains four inserts, three in the sense orientation and one in the antisense orientation (+, +, −, and +). Prolactin-luc contains 2,500 bases of the rat prolactin enhancer-promoter linked to the luciferase gene (22). The Pit-1 expression vector contains full-length rat Pit-1 cDNA with the Rous sarcoma virus promoter or enhancer (16). A CMV β-galactosidase reporter plasmid (Clontech) was cotransfected in all experiments as a control for transfection efficiency.

Cell culture, transient transfections, luciferase, and β-galactosidase assays.

COS-7 cells were cultured as previously described (20) in 60-mm dishes and were transfected by a modification of the calcium phosphate method (12). The cells were fed 2 h prior to transfection. Plasmid DNA (5 μg each of expression and reporter vectors) in 1 ml of 1× HBS (140 mM NaCl, 0.8 mM Na2HPO4, 25 mM HEPES [pH 7.1]) and 125 mM calcium chloride were added to the medium and allowed to precipitate overnight; fresh medium was added for 4 h prior to harvest. Cells were incubated for 24 h and then lysed and assayed for reporter activities and protein content by the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad). Luciferase activity was measured by using reagents from Promega. β-Galactosidase activity was measured by using Galacto-Light Plus reagents (Tropix Inc.). All luciferase activities were normalized to β-galactosidase activity. Pitx2 proteins transiently expressed in COS-7 cells were detected by immunoblotting with a c-myc monoclonal antibody (9E10; Santa Cruz), as described above.

RESULTS

The C terminus of Pitx2 represses DNA binding activity.

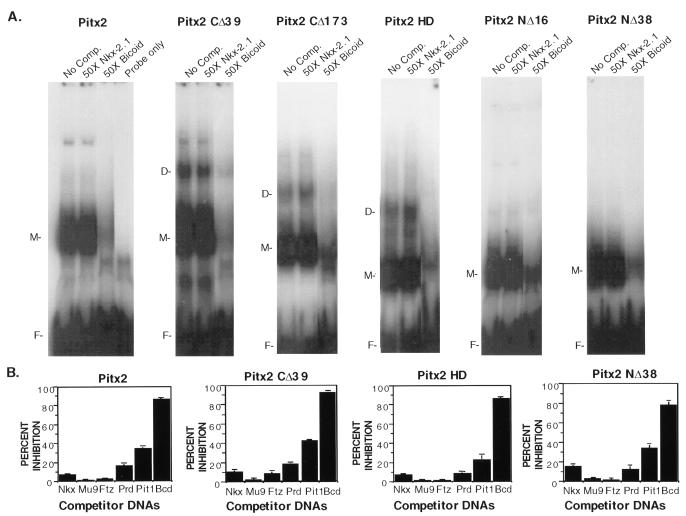

Since the 14-amino-acid sequence in the C-terminal end of Pitx2 is highly conserved among this family of homeobox proteins, we asked if it affected DNA binding. A 39-amino-acid deletion was engineered to remove the conserved 14 amino acids and flanking residues from Pitx2 (Pitx2CΔ39) (Fig. 1). EMSAs with Pitx2 and the Pitx2CΔ39 truncated protein demonstrated a two- to threefold increase in binding of Pitx2CΔ39 to the bicoid element (Fig. 2A and C). Deletion of the C-terminal 39 residues also allowed formation of homodimers. A competition analysis with oligonucleotides containing the Nkx class (5′CAAGTG3′), ftz class (5′TAATGG3′), prd class (5′TTTGACGT3′), Mu9 (5′TAATAT3′), and other homeodomain binding sites revealed comparable binding specificity for Pitx2 and Pitx2CΔ39 to the bicoid probe (Fig. 2). Thus, deletion of the C-terminal 39 residues did not affect the binding specificity of Pitx2 but did increase binding of monomers and dimer formation.

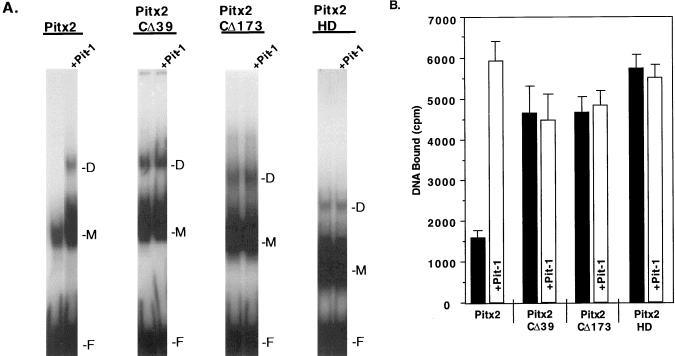

FIG. 2.

The C terminus of Pitx2 inhibits DNA binding activity. (A) Pitx2 proteins (∼160 ng) (40 ng of Pitx2HD) were incubated with the bicoid consensus sequence as the radioactive probe in the absence (No Comp.) or presence of 50-fold molar excess unlabeled oligonucleotides as competitor DNA. Approximately 160 ng of Pitx2CΔ173 was used in the EMSA that would reflect a twofold increase in the molar amount of Pitx2CΔ173 compared to that of Pitx2CΔ39. Similar results were seen using 80 ng of Pitx2CΔ173 (not shown). The EMSA experiments were analyzed on native 8% polyacrylamide gels. The free probe and bound complexes are indicated: D, dimer; M, monomer; and F, free. (B) Quantitation of the DNA binding of Pitx2 and truncated Pitx2 proteins from the EMSA experiments. The free and bound DNA radioactivity was measured, and the inhibition of the bound complex from the 50-fold excess of each competitor DNA was determined. The values were normalized to 100% binding without competitor DNA, with means and standard errors of the means from 5 to 10 independent experiments. (C) Quantitation of bound DNA (monomer and dimer forms) from EMSA experiments with Pitx2 and Pitx2 truncated proteins. The radioactive bound DNA was measured from 5 to 10 independent experiments, and the error bars are standard errors of the means.

We have previously shown by Scatchard plots that the apparent KD for Pitx2 binding to the bicoid element is 50 nM (2). We determined that the apparent KD of Pitx2CΔ39 binding to the bicoid sequence is similar, 58 nM, with a twofold increase in the Bmax (data not shown). Interestingly, when we measured the binding affinities of these two proteins as GST fusions, an astonishingly 750-fold increase in the binding capacity of GST-Pitx2CΔ39 over GST-Pitx2 was observed (data not shown). While the basis for this is not known, the GST moiety appears to enhance the effect of the C-terminal deletion.

Deletion of the entire C terminus, Pitx2CΔ173, did not further increase the binding compared to that of Pitx2CΔ39 (Fig. 2C). Pitx2CΔ173 also bound to the bicoid element as a dimer without a loss in specificity (Fig. 2 and data not shown). We next asked if the homeodomain by itself would bind the bicoid site with the same increase in DNA binding activity. We used a molar amount of Pitx2HD equal to that of the wild type in our EMSA experiments. Pitx2HD bound the bicoid site with the same specificity as Pitx2 and Pitx2CΔ39 (Fig. 2). The binding of Pitx2HD similarly resulted in the formation of homodimers, suggesting that dimerization occurs through the homeodomain of Pitx2.

We further wanted to determine if the N terminus had an effect on Pitx2 DNA binding activity. Removal of the entire N-terminal region, Pitx2NΔ38, revealed an approximately twofold increase in binding to the bicoid probe compared to that of the wild type (Fig. 2A and C). Thus, deletion of either the N or C terminus flanking the homeodomain increases Pitx2 DNA binding activity. These deletions did not significantly affect the specificity of binding, as revealed by competition assays with a panel of competitor DNA (Fig. 2B).

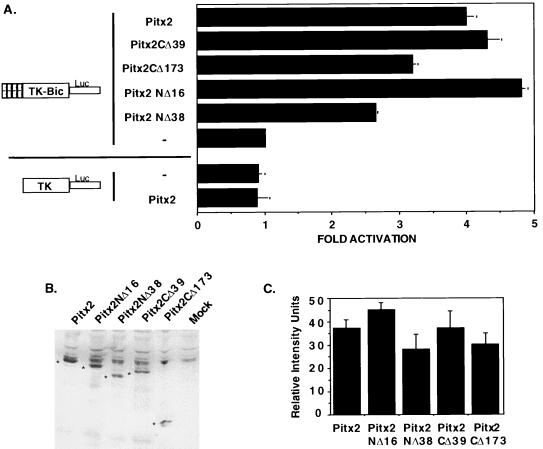

Deletion of either the N or C terminus affects Pitx2 transactivation of the bicoid promoter.

We have investigated the transactivation potential of Pitx2 with a TK-luciferase reporter containing four bicoid sites upstream of the TK promoter. We have previously shown that this reporter is activated by Pitx2 (2). Cotransfection of a wild-type Pitx2 expression vector yielded a fourfold activation of the bicoid reporter in COS-7 cells (Fig. 3A). As a control, Pitx2 did not transactivate the parental TK-luciferase reporter plasmid or the CMV β-galactosidase reporter gene used to normalize for transfection efficiency (Fig. 3A). HeLa transfections yielded similar results (data not shown). Since Pitx2CΔ39 had increased DNA binding, we expected that this protein might also have increased transactivation activity. Instead, the C-terminal truncation, Pitx2CΔ39, transactivated this reporter in a manner comparable to that of the wild type (Fig. 3A). Thus, other factors present in COS and HeLa cells may interact with the C terminus of wild-type Pitx2 to reduce the inhibitory binding effect and allow for basal transcription. Pitx2CΔ173 demonstrated a modest decrease in transactivation of the bicoid reporter (Fig. 3A). Pitx2NΔ16 transactivated this reporter at a slightly higher level than the wild type, whereas Pitx2NΔ38 demonstrated a decrease in activity similar to that of Pitx2CΔ173 (Fig. 3A). Transient transfection of the homeodomain alone, Pitx2HD, did not transactivate the reporter (data not shown). However, we were unable to detect Pitx2HD protein in transfected cells, indicating that this truncated protein may be unstable. We confirmed expression of all other transfected proteins by Western blot analysis (Fig. 3B). A representative blot is shown in Fig. 3B, and data from 6 to 10 independent experiments were quantitated and are shown in Fig. 3C. Thus, Pitx2 and Pitx2 truncated proteins were all expressed at similar levels. These data suggest that the N- and C-terminal regions contain transcriptional activity.

FIG. 3.

Transcriptional activation of a TK-bicoid-luciferase reporter by Pitx2 and Pitx2 truncations in COS-7 cells. (A) COS-7 cells were transfected with either the TK-bicoid-luciferase reporter gene containing four copies of the Pitx2 binding site (dashed boxes) or the parental TK-luciferase reporter without the bicoid sites. The cells were cotransfected with either the CMV Pitx2, Pitx2CΔ39, Pitx2CΔ173, Pitx2NΔ16, or Pitx2NΔ38 expression plasmid or the CMV plasmid without Pitx2 (−). To control for transfection efficiency, all transfections included the CMV β-galactosidase reporter. Cells were incubated for 24 h and then were assayed for luciferase and β-galactosidase activities. The activities are shown as mean fold activations compared to that of TK-bicoid-luciferase without Pitx2 expression (± standard errors of the means from four independent experiments). The mean TK-bicoid-luciferase activity with Pitx2 expression was about 15,000 light units per 15 μg of protein, and the β-galactosidase activity was about 100,000 light units per 15 μg of protein. (B) Proteins were expressed in mammalian cells with a C-terminal myc epitope and detected by using a c-myc monoclonal antibody (9E10; Santa Cruz). Specific protein bands are denoted with an asterisk. (C) Quantitation of 6 to 10 independent Western blot experiments. Error bars are standard errors of the mean. Specific band intensities from the Western blots were measured by using NIH Image, with the bundled macros provided for gel analysis to measure band densities relative to the average background. Measurements are reported as relative intensity units.

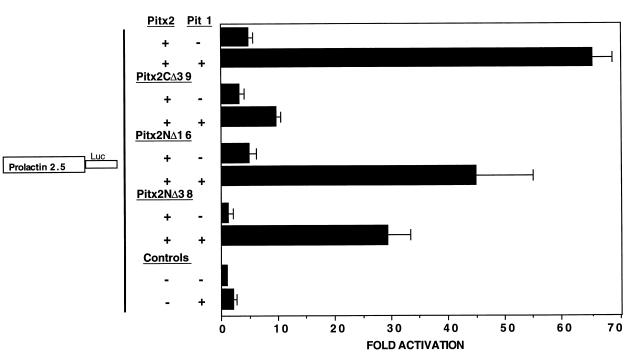

C-terminal Pitx2 truncations reduce synergistic transactivation of the prolactin promoter.

To determine if the Pitx2 C terminus was required for synergistic transactivation, we tested our C-terminal truncations in cotransfection experiments with the prolactin promoter reporter. We have previously shown that Pitx2 transactivates this promoter in a synergistic manner with Pit-1 (2). Transient transfection of the prolactin promoter luciferase reporter with Pitx2 in HeLa (data not shown) and COS-7 cells resulted in a fivefold increase in luciferase activity (Fig. 4). Similarly, Pitx2CΔ39 transactivated the prolactin promoter threefold (Fig. 4). Transfection of Pit-1 demonstrated a modest two- to threefold activation (Fig. 4). Cotransfection of Pitx2 and Pit-1 resulted in a 65-fold synergistic activation of the prolactin promoter (Fig. 4). However, cotransfection of Pitx2CΔ39 and Pit-1 yielded only a 10-fold activation (Fig. 4). These data indicate that the Pitx2 C-terminal 39 residues are required for maximal synergistic transactivation of the prolactin promoter by Pit-1. Transfection of Pitx2NΔ16, with and without Pit-1, yielded activation similar to that of wild-type Pitx2 (Fig. 4). In contrast, Pitx2NΔ38 transactivated only the prolactin promoter ∼2-fold, similar to the decreased activity seen with the TK-bicoid promoter (Fig. 4). Cotransfection of Pitx2NΔ38 with Pit-1 also resulted in decreased synergistic transactivation (Fig. 4). Similar to the transactivation data with the TK-bicoid reporter (Fig. 3), removal of either N- or C-terminal Pitx2 residues reduced Pitx2 activity. Most importantly, these data demonstrate that the C-terminal 39 residues are required for synergism between Pitx2 and Pit-1.

FIG. 4.

Pitx2 C-terminal truncations reduce the Pit-1 synergistic transactivation of the prolactin promoter. COS-7 cells were transfected with the prolactin 2.5-luciferase reporter gene and cotransfected with either the CMV Pitx2, Pitx2CΔ39, Pitx2NΔ16, Pitx2NΔ38, and Pitx2HD expression plasmids (+) or the CMV plasmid without Pitx2 (−). Pit-1 was cotransfected with the expression plasmids. To control for transfection efficiency, all transfections included the CMV β-galactosidase reporter. Cells were incubated for 24 h and then assayed for luciferase and β-galactosidase activities. The activities are shown as mean fold activations compared to activation of prolactin 2.5-luciferase without Pitx2 expression (± standard errors of the means from three independent experiments).

Pit-1 interacts with the Pitx2 C terminus to increase its DNA binding capacity.

To determine the region of Pitx2 required for Pit-1-enhanced Pitx2 binding, we assayed several N-terminal and C-terminal truncations by EMSA. Addition of Pit-1 to the binding reaction increased the amount of Pitx2 DNA-bound complex approximately fourfold (Fig. 5A and B). We have previously shown that Pit-1 is not in this Pitx2 DNA- bound complex (2). Pit-1 had little or no effect on the binding activity of the C-terminal mutants Pitx2CΔ39 and Pitx2CΔ173 or Pitx2HD (Fig. 5). Since Pitx2CΔ39 and Pitx2CΔ173 binding was unaffected by Pit-1, these data suggest that the C-terminal 39 amino acids of Pitx2 interact with Pit-1 to facilitate binding to DNA. The binding of the wild type in the presence of Pit-1 is quantitatively similar to the binding of Pitx2CΔ39 without Pit-1 (Fig. 5). Hence, Pit-1 reduces the inhibitory effect of the C-terminal tail on Pitx2 binding to DNA.

FIG. 5.

Pit-1 increases the binding capacity of Pitx2 in vitro. (A) Pitx2 DNA binding activity in the presence of Pit-1 protein was measured by EMSA. The labeled probe was the bicoid oligonucleotide. Totals of 80 ng of Pitx2, Pitx2CΔ39, and Pitx2CΔ173 and 40 ng of Pitx2HD proteins were incubated with Pit-1 before addition of the probe. D, dimer; M, monomer; F, free probe. (B) Quantitation of bound DNA (monomer and dimer forms) from EMSA experiments with Pitx2 and Pitx2 truncated proteins in the presence or absence of Pit-1. The radioactive bound DNA was measured from three to five independent experiments, and the error bars are standard errors of the mean.

The C-terminal 39 amino acids of Pitx2 are required and sufficient for binding Pit-1.

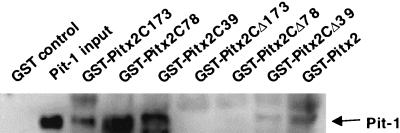

To determine whether the C-terminal tail of Pitx2 is required to bind Pit-1, we performed in vitro solution binding assays with immobilized GST-Pitx2 and GST-Pitx2 truncated proteins. After incubating the immobilized proteins with Pit-1, we measured Pit-1 binding by Western blot analysis using a Pit-1 antibody. Pit-1 bound to wild-type GST-Pitx2 but not to the GST control (Fig. 6). For comparison, the same amount of Pit-1 used in the binding assay was immunoblotted (Fig. 6). The C-terminally deleted GST fusion proteins, GST-Pitx2CΔ173, and −Pitx2CΔ78 did not bind Pit-1, and GST-Pitx2CΔ39 bound only a small amount of Pit-1 (Fig. 6). To test whether these residues were sufficient for Pit-1 binding, we made GST fusion proteins of the C-terminal 173, 78, and 39 residues. All of the C-terminal GST fusion proteins bound Pit-1 at levels comparable to that of the full-length Pitx2 protein (Fig. 6). Thus, Pit-1 physically interacts with the C-terminal 39 amino acids of Pitx2.

FIG. 6.

The C-terminal 39 amino acids of Pitx2 contain a protein-protein interaction domain. Immobilized GST-Pitx2, GST-Pitx2CΔ39, GST-Pitx2CΔ78, GST-Pitx2CΔ173, GST-Pitx2C39, GST-Pitx2C78, and GST-Pitx2C173 or GST proteins were incubated with 40 ng of Pit-1, washed, and analyzed for their interaction with Pit-1. The immobilized proteins were run out on an SDS–12.5% polyacrylamide gel, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, and immunoblotted with Pit-1 polyclonal antibody. A total of 40 ng of Pit-1 was loaded directly on the gel as a positive control (Pit-1 input).

Pitx2 C-terminal 39 amino acids inhibit Pitx2 transactivation.

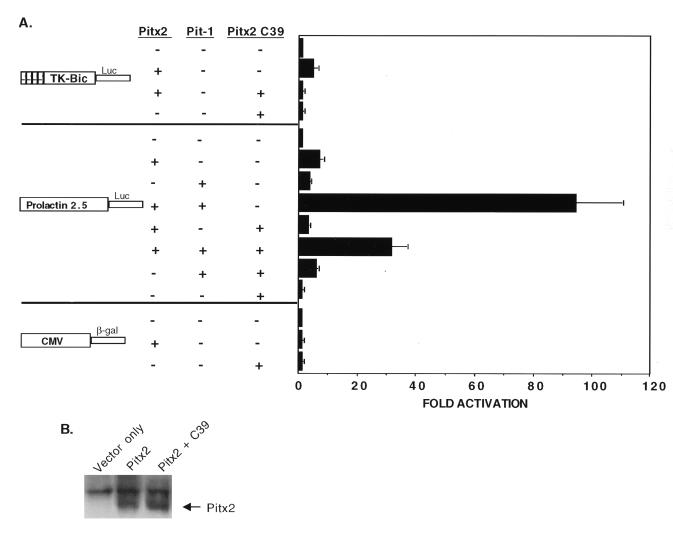

Having shown that the C-terminal tail alone was capable of binding Pit-1 in vitro, we then asked whether it could act in trans to regulate Pitx2 activity. We reasoned that since it is a site for protein-protein interaction it might bind and sequester essential transcription cofactors required for Pitx2 transactivation. We found that cotransfection of an expression vector encoding the C-terminal 39 amino acids did indeed inhibit Pitx2 transactivation of the bicoid reporter to basal levels (Fig. 7A). The C39 peptide also decreased Pitx2 transactivation of the prolactin promoter and decreased synergistic transactivation by Pitx2 and Pit-1 (Fig. 7A). As a control, we determined that C39 had no effect on the bicoid or prolactin promoters in the absence of Pitx2. Furthermore, the C39 peptide did not repress Pit-1 activation of the prolactin promoter. Finally, the C39 peptide had no effect on the CMV β-galactosidase reporter used to normalize for transfection efficiency (Fig. 7A). To rule out the possibility that this inhibition was due to reduced Pitx2 levels, we measured Pitx2 expression in transfected cell lysates (Fig. 7B). Using an antibody that recognizes the c-myc epitope on the expressed Pitx2 proteins, we demonstrated that the C39 peptide had no effect on Pitx2 expression (Fig. 7B). Since the C-terminal 39 residues contain a protein-protein interaction site that is required for Pit-1 binding, we speculate that these residues may also bind other factors. However, the C39 peptide did not affect CMV β-galactosidase, bicoid, or prolactin reporter luciferase activity, suggesting that it was not binding a general transcription factor. Thus, the C39 peptide might be interacting with Pitx2 to inhibit transactivation.

FIG. 7.

The Pitx2 C39 peptide inhibits Pitx2 transactivation of the bicoid and prolactin promoters. (A) Transient transfection of COS-7 cells was done as described in the legends for Fig. 3 and 4. Equal amounts (3 μg) of the CMV Pitx2C39 expression plasmid and the CMV Pitx2 plasmid were cotransfected with the indicated reporter plasmid. Pit-1 was cotransfected as described in the legend to Fig. 4. The activities are shown as mean fold activations compared to those of TK-bicoid-luciferase and prolactin 2.5-luciferase without Pitx2 expression (± standard errors of the means from four independent experiments). (B) Western blot of transfected cell lysates with the c-myc antibody that recognizes the myc epitope fused to the expressed Pitx2 protein.

Pitx2 N terminus is required for the inhibition of transactivation by the C39 peptide.

To determine the mechanism of the C39 peptide repression of Pitx2 transactivation, we transiently cotransfected the Pitx2 deletion plasmids with the C39 expression vector in COS-7 cells. The C39 peptide inhibited the wild type, Pitx2NΔ16, and all of the C-terminal deletion constructs (Fig. 8 and data not shown). In contrast, C39 peptide did not affect Pitx2NΔ38 transactivation of the bicoid reporter (Fig. 8). This indicates that N-terminal residues 16 to 38 are required for inhibition by the C39 peptide. These results suggest that the C-terminal 39 amino acids may interact with the N terminus to attenuate Pitx2 transcription activity.

FIG. 8.

The Pitx2 N-terminal amino acids 16 to 38 are required for the C39 peptide inhibition of Pitx2 transactivation activity. Transient transfection of COS-7 cells was performed as previously described in the legend for Fig. 3 for the CMV Pitx2 expression plasmids (+), the bicoid reporter, and the CMV Pitx2C39 expression vector. The activities are shown as mean fold activations compared to that of TK-bicoid-luciferase without Pitx2 expression (± standard errors of the means from three independent experiments).

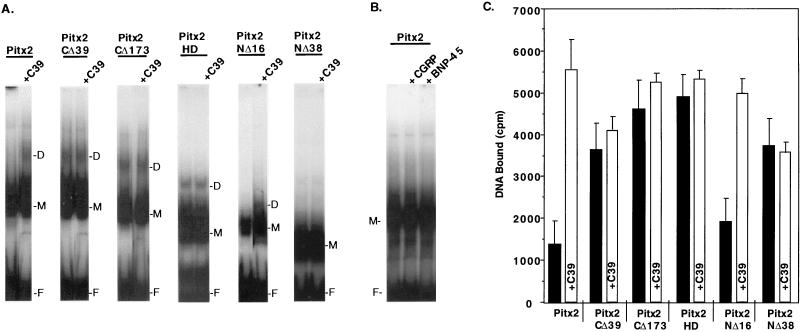

C39 peptide increases the DNA binding of Pitx2.

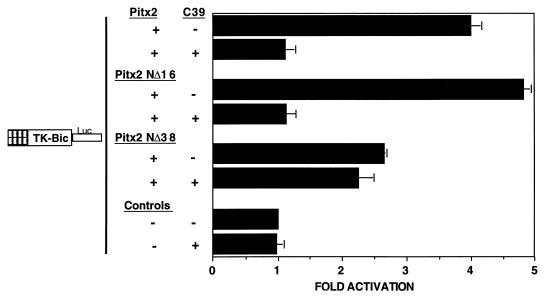

Since the C39 peptide had no effect on Pitx2NΔ38 transactivation, these results suggested that the C39 peptide binds to the N terminus of Pitx2. Similar to our studies with Pit-1 binding, we used EMSA to demonstrate a functional interaction of the C39 peptide with Pitx2. The addition of 160 ng of C39 peptide to the EMSA binding reaction increased the level of Pitx2 binding approximately threefold, compared to Pitx2 binding without C39, and resulted in homodimer formation (Fig. 9A and C). The C39 peptide had no effect on the binding activities of Pitx2CΔ39, Pitx2CΔ173, or Pitx2HD (Fig. 9A and C). Although transactivation of the C-terminal truncations were repressed by the C39 peptide, the DNA binding activities were not affected. This would be expected since the C-terminal truncated proteins have the inhibitory domain deleted, resulting in maximal levels of DNA binding activity. Furthermore, the C39 peptide had no effect on the DNA binding of the N-terminal truncated protein Pitx2NΔ38; however, the C39 peptide increased the binding of Pitx2NΔ16 and facilitated the formation of homodimers (Fig. 9A and C). Since Pitx2NΔ38 does not form dimers by itself (Fig. 2 and 9), we cannot rule out the possibility that the C terminus of Pitx2 may also be interacting with part of the homeodomain. However, our data indicate that the Pitx2 C terminus does not interact with residues C terminal to the homeodomain. The C39 peptide did not bind the bicoid DNA element by itself (data not shown). We tested two other peptides on their ability to stimulate Pitx2 binding. The calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP; 37 amino acids) and brain natriuretic peptide-45 (BNP-45; 45 amino acids) had no effect on Pitx2 DNA binding (Fig. 9B). The BNP-45 peptide is very similar in amino acid composition to the C39 peptide. Taken together with the transfection data, these results suggest that the C39 peptide binds to N-terminal amino acids 16 to 38 to allow increased DNA binding in vitro.

FIG. 9.

The C39 peptide facilitates Pitx2 binding to DNA. (A) EMSAs were done essentially as described in the legend for Fig. 5 with the addition of ∼160 ng of Pitx2C39 peptide and ∼160 ng of Pitx2 proteins (40 ng of Pitx2HD). Shown are the results of EMSA experiments with the C-terminally deleted and N-terminally deleted proteins and the homeodomain alone with and without the C39 peptide. For this experiment, we show a less exposed autoradiograph than that in Fig. 2. This was done to more clearly visualize the dimers in the presence of the C39 peptide. D, dimer; M, monomer; F, free probe. (B) As a control, molar amounts of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP; ∼160 ng; Sigma) or BNP-45 (∼184 ng; Sigma) equal to that of the C39 peptide were added to Pitx2 in an EMSA experiment. (C) Quantitation of bound DNA (monomer and dimer forms) from EMSA experiments with Pitx2 and Pitx2 truncated proteins in the presence or absence of the C39 peptide. The radioactive bound DNA was measured from three to five independent experiments, and the error bars are standard errors of the means.

DISCUSSION

This study has described a novel mechanism for the regulation of a homeodomain protein expressed during embryogenesis. Deletion of the C-terminal 39 residues increases binding of the monomer form of Pitx2 and allows the formation of homodimers. Our data are consistent with this region containing a DNA binding inhibitory element. There is precedence for intrinsic regulation among homeodomain proteins. For example, the Nkx2.5 homeobox protein also contains a C-terminal DNA binding inhibitory element that inhibits transactivation (6, 9). Deletion of 115 residues in the C terminus of Nkx2.5 increased DNA binding activity, similar to our finding with Pitx2 (32). However, Pitx2 differs from Nkx2.5 in that the Pitx2 C-terminal region is also the site of interaction with other transcription factors. In the Pax family of proteins, an inhibitory element is also in the C terminus, although it is not known if it acts at the level of DNA binding (7). In contrast to Nkx2.5 and the Pax proteins, deletion of the Pitx2 C-terminal inhibitory domain does not result in a stimulation of transcriptional activity. This is consistent with our proposal that this region is also the site for protein-protein interactions required for optimal transcriptional activity. In support of this prediction, we demonstrated that Pit-1 binds the C-terminal 39 amino acids and that there was little or no synergism with Pit-1 in the absence of the C-terminal domain.

A recurring theme among homeodomain proteins is the important role of protein-protein interactions in modulating activity. Some of these interactions can stimulate transcriptional activity (3, 4, 9, 38), while others act to inhibit it (5, 15, 35, 37, 43). A mechanism for regulating the transcriptional actions of Pitx2 is its interaction with other transcription factors. We have shown that the C-terminal region of Pitx2 can directly bind the POU homeodomain protein, Pit-1. Pit-1 is well-known for its regulation of pituitary cell differentiation and expression of pituitary hormones, including prolactin (29). At least one manifestation of this interaction is increased Pitx2 DNA binding in vitro. There is precedence for protein interactions yielding increased DNA binding activity (13, 35, 42). For example, Pbx can increase the DNA binding of Hox proteins and the engrailed homeodomain protein (24, 25). Likewise, Prospero (Pros) has been shown to increase the DNA binding of Deformed (Dfd) and Hoxa-5 (15). Interestingly, Pros is not part of the Dfd-DNA complex (15), similar to our finding with Pit-1 and Pitx2 (2). Pit-1 binding to Pitx2 also results in a synergistic activation of the prolactin promoter. Thus, the C-terminal protein-protein interaction domain of Pitx2 regulates DNA binding and transcriptional activities in response to specific factors, such as Pit-1.

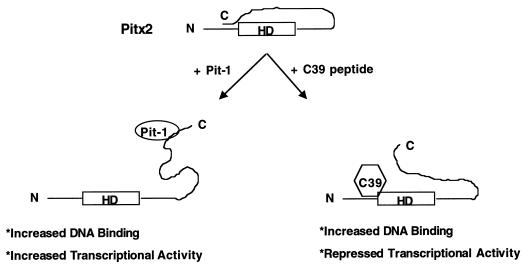

We propose that intramolecular folding of the full-length Pitx2 protein brings the C-terminal tail in direct contact with the N-terminal domain (Fig. 10). This folding would interfere with DNA binding by the homeodomain. However, after Pitx2 binds DNA, this disrupts the C-terminal tail interaction with the N terminus. We have shown that the C39 peptide inhibits transactivation by wild-type Pitx2 but not by Pitx2NΔ38. This indicates that the C39 peptide interacts with Pitx2 through N-terminal residues 16 to 38. We used a GST-Pitx2C39 and -Pitx2C78 peptide pull-down assay to bind Pitx2 and the C-terminal truncations, demonstrating that the C-terminal tail interacts with the N terminus of Pitx2 (data not shown). From these data, we speculate that in the absence of a cofactor, the C-terminal 39 residues interact with a domain in the N terminus of Pitx2 to modulate the DNA binding and transcriptional activities of Pitx2. When a specific cofactor such as Pit-1 binds to the C terminus, it relieves this inhibition. Pit-1 binding to Pitx2 may cause a conformational change in the C-terminal tail that unmasks the homeodomain and a potential transactivation domain. Our model predicts that Pitx2 may not be fully activated until expression of the appropriate cofactors.

FIG. 10.

Model for the multifunctional role of the Pitx2 C-terminal tail. The Pitx2 protein is shown as an intramolecular folded species. The folding interferes with DNA binding of Pitx2. Pit-1 binds to the C-terminal tail of Pitx2 and disrupts the inhibitory function of the C terminus. This allows for a more efficient homeodomain interaction with the target DNA and transactivation. The Pitx2 C39 peptide interaction with the N terminus of Pitx2 displaces the C-terminal tail and increases its binding activity. However, the C39 peptide masks an N-terminal transactivation domain that results in repressed transcriptional transactivation. N, N-terminal end; C, C-terminal end; HD, homeodomain.

In Rieger syndrome, a C-terminal truncation at amino acid 133 causes several developmental defects. Thus, in addition to its expression in the pituitary, Pitx2 is also required for eye and tooth development, suggesting that Pitx2 is regulated in multiple tissues by a combination of interacting factors (30). The ability of Pitx2 to be activated during development could be a function of factors interacting with its C terminus to increase DNA binding and transcriptional activity. The C-terminal tail contains a 14-amino-acid stretch that is conserved among the Pitx family members and several other homeodomain proteins (30). Many of these proteins, such as prx1, prx2, Cart1, aristaless, chx10, otp, and Pitx1, are expressed at high levels in the craniofacial region, suggesting an important role for this multifunctional C-terminal regulatory mechanism in craniofacial development.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J. Murray and E. Semina for providing the Pitx2 cDNA and helpful discussions.

National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant DE09170 to A.F.R., with tissue culture support from DK25295, and NIH Postdoctoral Training Fellowship DK07018 to B.A.A. supported this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amand T R S, Ra J, Zhang Y, Hu Y, Baber S I, Qiu M, Chen Y P. Cloning and expression pattern of chicken Pitx2: a new component in the SHH signaling pathway controlling embryonic heart looping. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;247:100–105. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amendt B A, Sutherland L B, Semina E, Russo A F. The molecular basis of Rieger syndrome: analysis of Pitx2 homeodomain protein activities. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:20066–20072. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.32.20066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bach I, Carriere C, Ostendorff H P, Andersen B, Rosenfeld M G. A family of LIM domain-associated cofactors confer transcriptional synergism between LIM and Otx homeodomain proteins. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1370–1380. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.11.1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradford A P, Wasylyk C, Wasylyk B, Gutierrez-Hartmann A. Interaction of Ets-1 and the POU-homeodomain protein GHF-1/Pit-1 reconstitutes pituitary-specific gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1065–1074. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.3.1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Budhram-Mahadeo V, Parker M, Latchman D S. POU transcription factors Brn-3a and Brn-3b interact with the estrogen receptor and differentially regulate transcriptional activity via an estrogen response element. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:1029–1041. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.2.1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen C, Schwartz R J. Identification of novel binding targets and regulatory domains of a murine tinman homeodomain factor, nkx-2.5. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:15628–15633. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.26.15628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dorfler P, Busslinger M. C-terminal activating and inhibitory domains determine the transactivation potential of BSAP (Pax-5), Pax-2 and Pax-8. EMBO J. 1996;15:1971–1982. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Driever W, Nusslein-Volhard C. The bicoid protein is a positive regulator of hunchback transcription in the early Drosophila embryo. Nature. 1989;337:138–143. doi: 10.1038/337138a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Durocher D, Charron F, Warren R, Schwartz R J, Nemer M. The cardiac transcription factors Nkx2-5 and GATA-4 are mutual cofactors. EMBO J. 1997;16:5687–5696. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.18.5687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gage P J, Camper S A. Pituitary homeobox 2, a novel member of the bicoid-related family of homeobox genes, is a potential regulator of anterior structure formation. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:457–464. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.3.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gehring W J, Qian Y Q, Billeter M, Tokunaga K F, Schier A F, Perez D R, Affolter M, Otting G, Wuthrich K. Homeodomain-DNA recognition. Cell. 1994;78:211–223. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90292-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graham F J, Van der Eb A J. A new technique for the assay of infectivity of human adenovirus 5 DNA. Virology. 1973;52:456–460. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(73)90341-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guichet A, Copeland J W R, Erdelyl M, Hlousek D, Zavorszky P, Ho J, Brown S, Percival-Smith A, Krause H M, Ephrussi A. The nuclear receptor homologue Ftz-F1 and the homeodomain protein Ftz are mutually dependent cofactors. Nature. 1997;385:548–552. doi: 10.1038/385548a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanes S D, Brent R. DNA specificity of the bicoid activator protein is determined by homeodomain recognition helix residue 9. Cell. 1989;57:1275–1283. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hassan B, Li L, Bremer K A, Chang W, Pinsonneault J, Vaessin H. Prospero is a panneural transcription factor that modulates homeodomain protein activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10991–10996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iverson R A, Day K H, d’Emden M, Day R N, Maurer R A. Clustered point mutation analysis of the rat prolactin promoter. Mol Endocrinol. 1990;4:1564–1571. doi: 10.1210/mend-4-10-1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jin Y, Hoskins R, Horvitz H R. Control of type-D GABAergic neuron differentiation by C. elegans UNC-30 homeodomain protein. Nature. 1994;372:780–783. doi: 10.1038/372780a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumar J, Moses K. Transcription factors in eye development: a gorgeous mosaic? Genes Dev. 1997;11:2023–2028. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.16.2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lamonerie T, Tremblay J J, Lanctot C, Therrien M, Gauthier Y, Drouin J. Ptx1, a bicoid-related homeo box transcription factor involved in transcription of the pro-opiomelanocortin gene. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1284–1295. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.10.1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lanigan T M, Russo A F. Binding of upstream stimulatory factor and a cell-specific activator to the calcitonin gene-related peptide enhancer. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:18316–18324. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.29.18316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Logan M, Pagan-Westphal S M, Smith D M, Paganessi L, Tabin C J. The transcription factor Pitx2 mediates situs-specific morphogenesis in response to left-right asymmetric signals. Cell. 1998;94:307–317. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81474-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maurer R A, Notides A C. Identification of an estrogen-responsive element from the 5′-flanking region of the rat prolactin gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:4247–4254. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.12.4247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McGinnis W, Krumlauf R. Homeobox genes and axial patterning. Cell. 1992;68:283–302. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90471-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neuteboom S T C, Murre C. Pbx raises the DNA binding specificity but not the selectivity of antennapedia Hox proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4696–4706. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.8.4696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peltenburg L T C, Murre C. Specific residues in the Pbx homeodomain differentially modulate the DNA-binding activity of Hox and Engrailed proteins. Development. 1997;124:1089–1098. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.5.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Piedra M E, Icardo J M, Albajar M, Rodriguez-Rey J C, Ros M A. Pitx2 participates in the late phase of the pathway controlling left-right asymmetry. Cell. 1998;94:319–324. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81475-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rieger H. Dysgenesis mesodermalis coreneal et iridis. Z Augenheilk. 1935;86:333. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ryan A K, Blumberg B, Rodriguez-Esteban C, Yonei-Tamura S, Tamura K, Tsukui T, de la Pena J, Sabbagh W, Greenwald J, Choe S, Norris D P, Robertson E J, Evans R M, Rosenfeld M G, Belmonte J C I. Pitx2 determines left-right asymmetry of internal organs in vertebrates. Nature. 1998;394:545–551. doi: 10.1038/29004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ryan A K, Rosenfeld M G. POU domain family values: flexibility, partnerships, and developmental codes. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1207–1225. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.10.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Semina E V, Reiter R, Leysens N J, Alward L M, Small K W, Datson N A, Siegel-Bartelt J, Bierke-Nelson D, Bitoun P, Zabel B U, Carey J C, Murray J C. Cloning and characterization of a novel bicoid-related homeobox transcription factor gene, RIEG, involved in Rieger syndrome. Nat Genet. 1996;14:392–399. doi: 10.1038/ng1296-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Semina E V, Reiter R S, Murray J C. Isolation of a new homeobox gene belonging to the Pitx/Rieg family: expression during lens development and mapping to the aphakia region on mouse chromosome 19. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:2109–2116. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.12.2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sepulveda J L, Belaguli N, Nigam V, Chen C, Nemer M, Schwartz R J. GATA-4 and Nkx-2.5 coactivate Nkx-2 DNA binding targets: role for regulating early cardiac gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3405–3415. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.6.3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simeone A, Acampora D, Mallamaci A, Stornaiuolo A, D’Apice M R, Nigro V, Boncinelli E. A vertebrate gene related to orthodenticle contains a homeodomain of the bicoid class and demarcates anterior neurectoderm in the gastrulating mouse embryo. EMBO J. 1993;12:2735–2747. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05935.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simmons D M, Voss J W, Ingraham H A, Holloway J M, Broide R S, Rosenfeld M G, Swanson L W. Pituitary cell phenotypes involve cell-specific Pit-1 mRNA translation and synergistic interactions with other classes of transcription factors. Genes Dev. 1990;4:695–711. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.5.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stark M R, Johnson A D. Interaction between two homeodomain proteins is specified by a short C-terminal tail. Nature. 1994;371:429–432. doi: 10.1038/371429a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Szeto D P, Ryan A K, O’Connell S M, Rosenfeld M G. P-OTX: a PIT-1-interacting homeodomain factor expressed during anterior pituitary gland development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7706–7710. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tolkunova E N, Fujioka M, Kobayashi M, Deka D, Jaynes J B. Two distinct types of repression domain in engrailed: one interacts with the groucho corepressor and is preferentially active on integrated target genes. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2804–2814. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.5.2804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tremblay J J, Lanctot C, Drouin J. The pan-pituitary activator of transcription, Ptx1 (pituitary homeobox 1), acts in synergy with SF-1 and Pit1 and is an upstream regulator of the Lim-homeodomain gene Lim3/Lhx3. Mol Endocrinol. 1998;12:428–441. doi: 10.1210/mend.12.3.0073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tverberg L A, Russo A F. Regulation of the calcitonin/calcitonin gene-related peptide gene by cell-specific synergy between helix-loop-helix and octamer-binding transcription factors. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:15965–15973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilson D S, Sheng G, Jun S, Desplan C. Conservation and diversification in homeodomain-DNA interactions: a comparative genetic analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6886–6891. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.6886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yoshioka H, Meno C, Koshiba K, Sugihara M, Itoh H, Ishimaru Y, Inoue T, Ohuchi H, Semina E V, Murray J C, Hamada H, Noji S. Pitx2, a bicoid-type homeobox gene, is involved in a lefty-signaling pathway in determination of left-right asymmetry. Cell. 1998;94:299–305. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81473-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yu Y, Li W, Su K, Yussa M, Han W, Perrimon N, Pick L. The nuclear hormone receptor Ftz-F1 is a cofactor for the Drosophila homeodomain protein Ftz. Nature. 1997;385:552–555. doi: 10.1038/385552a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang H, Hu G, Wang H, Sciavolino P, Iler N, Shen M M, Abate-Shen C. Heterodimerization of Msx and Dlx homeoproteins results in functional antagonism. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2920–2932. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.5.2920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]