Abstract

Recently, a novel efflux pump gene cluster called tmexCD1-toprJ1 and its variants have been identified, which undermine the antibacterial activity of tigecycline, one of the last remaining options effective against multidrug-resistant (MDR) Gram-negative bacteria. Herein, we report the potent synergistic effect of the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug benzydamine in combination with tigecycline at sub-inhibitory concentrations against various temxCD-toprJ-positive Gram-negative pathogens. The combination of benzydamine and tigecycline killed all drug-resistant pathogens during 24 h of incubation. In addition, the evolution of tigecycline resistance was significantly suppressed in the presence of benzydamine. Studies on the mechanisms of synergism showed that benzydamine disrupted the bacterial proton motive force and the functionality of this kind of novel plasmid-encoded resistance-nodulation-division efflux pump, thereby promoting the intracellular accumulation of tigecycline. Most importantly, the combination therapy of benzydamine and tigecycline effectively improved the survival of Galleria mellonella larvae compared to tigecycline monotherapy. Our findings provide a promising drug combination therapeutic strategy for combating superbugs carrying the tmexCD-toprJ gene.

Keywords: tigecycline resistance, efflux pump, tmexCD-toprJ, benzydamine, Gram-negative bacteria

1. Introduction

Antibiotic resistance mediated by chromosome mutation or horizontal gene transfer constitutes a global threat to public health [1,2]. Alarmingly, the emergence of carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae (CRE) and MCR-producing enterobacterales (MCRPE) has aggravated the resistance crisis and leaves clinicians few choices from the existing antibiotic pipeline [3,4]. Tigecycline (TIG), a semisynthetic parenteral glycylcycline, was discovered in 1993 and introduced into clinical use in 2005 [5]. Notably, TIG has been considered as an extremely important treatment option for serious infections caused by multidrug-resistant (MDR) Gram-negative pathogens, including CRE and MCRPE [6]. However, the identification and prevalence of plasmid-mediated tet(X3/X4) [7] and the RND (resistance-nodulation-division) efflux pump gene cluster, tmexCD1-toprJ1 [8,9], in clinically important pathogens are undermining the efficacy of TIG in clinical practice.

Generally, the mechanisms of tetracycline resistance in bacteria are commonly associated with tetracycline-specific efflux pumps, ribosomal protection, tetracycline-inactivating enzymes and multidrug-resistant efflux pumps [10]. Tet(X) and its orthologs are 388 amino acid flavin-dependent monooxygenases that can hydroxylate C11a of the tetracycline scaffold [11]. The tet(X3/X4) gene-encoded tetracycline-inactivating enzymes can confer high levels of TIG resistance to bacteria and are even able to inactivate all tetracyclines [12]. Furthermore, the RND family exporters, as a representative of MDR pumps, also made an important contribution to tigecycline resistance. In subcellular organization, the chromosomally encoded tripartite complex of RND efflux pumps are located in the inner membrane (IM) but contacted with the membrane fusion protein (MFP) and outer membrane (OM) channel [13], such as AcrAB-TolC in E. coli and MexAB-OprM in P. aeruginosa. Because the chromosomes of most Gram-negative bacteria are able to meet the requirement of RND superfamily efflux genes, the RND-type efflux pumps rarely appear on mobile genetic elements such as plasmids [14]. Unfortunately, the first identification of a plasmid-borne RND family multidrug efflux pump gene, tmexCD1-toprJ1, which confers transferable tigecycline resistance in K. pneumoniae challenges this notion; other mobile variants, including tmexCD2-toprJ2 in Raoultella ornithinolytica and tmexCD3-toprJ3 in Proteus mirabilis, were also subsequently reported [15,16]. Considering that conjugative plasmids play an important role in the spread of antimicrobial resistance, novel therapeutic strategies are urgently required to confront these tigecycline-resistant pathogens carrying the mobile RND-type pumps gene cluster.

Accordingly, repurposing approved drugs as potential antibiotic adjuvants offers a time and cost-effective means to combat MDR Gram-negative pathogens [17,18]. For example, our previous study indicated that metformin, an oral diabetes medicine, restored tetracycline activity against MDR bacteria by promoting intracellular accumulation of antibiotics and boosting immune response [19]. In addition, we found that the anti-HIV agent azidothymidine decreased Tet(X3/X4)-mediated bacterial resistance to tigecycline in E. coli by specifically inhibiting DNA synthesis and suppressing resistance enzyme activity [20]. However, the combination of azidothymidine and TIG displayed no direct synergistic activity against tmexCD-toprJ-positive Gram-negative bacteria. Benzydamine (BEN) is a locally acting non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug and widely used pain-relieving and anti-inflammatory treatment for inflammatory conditions of the mouth and throat [21]. Recently, BEN has come to be considered a new drug for the treatment of bone disease due to its abilities to strengthen osteoblast differentiation and prevent bone loss [22]. However, its synergistic activity with antibiotics, particularly with tigecycline, is still not fully understood.

In this study, we reported that BEN markedly potentiated the antibacterial activity of tigecycline in the fight against tmexCD-toprJ-bearing bacteria, both in vitro and in the Galleria mellonella infection model. Furthermore, the combined use of benzydamine with tigecycline displayed potent bactericidal activity against tmexCD-toprJ-positive bacteria and suppressed the evolution of tigecycline resistance. The potentiation of BEN to TIG is attributed to the disruption of bacterial PMF and the dysfunction of the tmexCD-toprJ-mediated efflux pump. Our data demonstrate that the non-antibiotic agent benzydamine is a novel and potent antibiotic adjuvant in conjunction with tigecycline for the treatment of infection caused by tmexCD-toprJ-positive pathogens.

2. Results

2.1. Synergistic Activity between Benzydamine and Tigecycline against TMexCD-TOprJ-Positive Bacteria

To test the synergistic activity of BEN and TIG against TMexCD-TOprJ-positive pathogens, a collection of 12 clinical isolates of K. pneumoniae carrying a tmexCD1-toprJ1-bearing plasmid and two isolates of P. mirabilis carrying the chromosomal tmexCD3-toprJ3 gene cluster, isolated from swine fecal samples taken in Jiangsu Province, were utilized [16]. Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of four classes of antibiotics, including meropenem, ciprofloxacin, colistin and tetracyclines, were determined using the standard broth micro-dilution method, with E. coli ATCC 25922 as control. The results showed that the MICs for BEN were 500 μg/mL in K. pneumoniae and 2000 μg/mL in P. mirabilis (Table 1). All TMexCD-TOprJ-positive Gram-negative bacteria exhibited high resistance to all tetracycline antibiotics and ciprofloxacin, but were susceptible to meropenem and colistin. Nevertheless, it was previously found that some pathogens harboring tmexCD1-toprJ1 showed resistance to multiple antibiotics, including meropenem [23] and colistin [9,24]. With regard to TIG, the MIC values ranged from 16 to 32 μg/mL for these strains. Surprisingly, in the presence of one quarter of the MIC for BEN, the MIC values of TIG were significantly decreased, from by 4- to 256-fold, suggesting that the antibacterial activity of TIG was greatly potentiated in all test strains (Table 1). Notably, the potentiation of BEN to TIG was highly superior to the traditional efflux pump inhibitor 1-(1-naphthylmethyl)-piperazine (NMP) [15]. Meanwhile, it is plausible that the use of BEN would significantly reduce the administration dose of TIG, which may help alleviate potential side effects of TIG in the clinical setting.

Table 1.

Susceptibility profiles of Gram-negative bacteria harboring tmexCD-toprJ and potentiation of benzydamine to tigecycline.

| Strains | MIC (μg/mL) a | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tetracyclines | ||||||||||

| MEM | CIP | CL | MIN | OXY | DOX | TET | TIG | TIG b | BEN | |

| K. pneumoniae | ||||||||||

| RGB 7-1 | ≤0.25 | 16 | ≤0.25 | 128 | >256 | 64 | >256 | 32 | 0.125 (256) | 500 |

| RGF 85-1 | ≤0.25 | 8 | ≤0.25 | 64 | >128 | 64 | >128 | 32 | 4 (8) | 500 |

| RGF 105-1 | ≤0.25 | 8 | ≤0.25 | 256 | >256 | 64 | >256 | 32 | 0.125 (256) | 500 |

| RGF 140-1 | ≤0.25 | 8 | ≤0.25 | 128 | >128 | 128 | >128 | 32 | 8 (4) | 500 |

| RGF 172-1 | ≤0.25 | 32 | ≤0.25 | 256 | >256 | 256 | >256 | 32 | 8 (4) | 500 |

| RGT 5-2 | ≤0.25 | 4 | ≤0.25 | 64 | >128 | 64 | >128 | 32 | 0.25 (128) | 500 |

| RGT 31-2 | ≤0.25 | 4 | 0.5 | 128 | >256 | 128 | >256 | 32 | 0.125 (256) | 500 |

| RGT 34-2 | ≤0.25 | 2 | ≤0.25 | 64 | >256 | 256 | >256 | 32 | 4 (8) | 500 |

| RGW 5-1 | ≤0.25 | 16 | ≤0.25 | 64 | >256 | 128 | >256 | 32 | 0.25 (256) | 500 |

| SZP 4-3-1 | 0.5 | 64 | ≤0.25 | >256 | >256 | 256 | >256 | 32 | 16 (2) | 500 |

| TF 18-2 | ≤0.25 | >128 | ≤0.25 | >256 | >128 | 128 | >128 | 32 | 0.5 (64) | 500 |

| TF 44-1 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.25 | >256 | >128 | 64 | >128 | 32 | 0.5 (64) | 500 |

| P. mirabilis | ||||||||||

| RGF 11-2 | ≤0.25 | 64 | >128 | >256 | >256 | 256 | 256 | 16 | 4 (4) | 2000 |

| RGF 134-1 | ≤0.25 | 64 | >128 | 128 | >256 | 128 | 128 | 32 | 4 (8) | 2000 |

a MEM, meropenem; CIP, Ciprofloxacin; CL, colistin; MIN, minocycline; OXY, oxytetracycline; DOX, doxycycline; TET, tetracycline; TIG, tigecycline; BEN, benzydamine. b MIC of tigecycline in the presence of 125 μg/mL (K. pneumoniae) or 500 μg/mL (P. mirabilis).

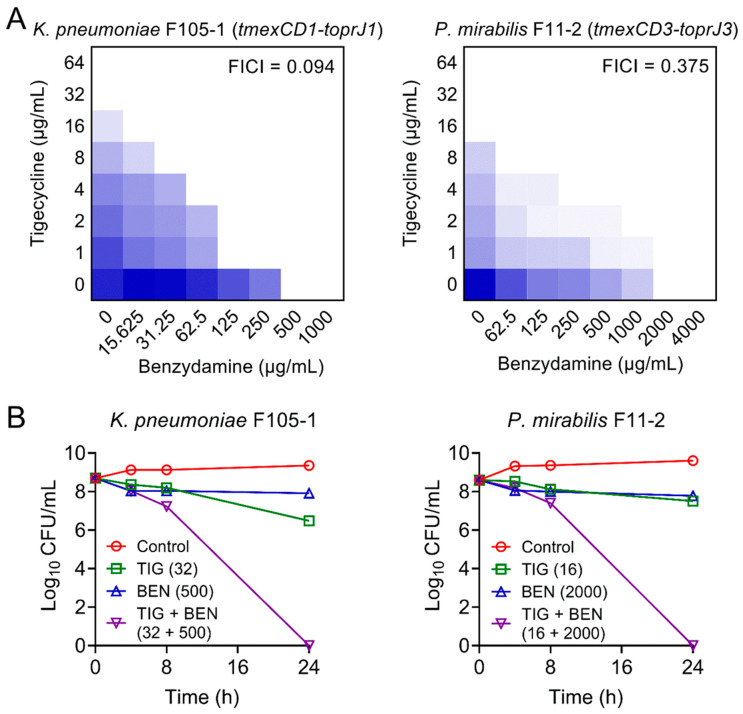

Furthermore, checkerboard assays were used to evaluate the synergism between BEN and TIG. This combination showed obvious synergistic activity with a fractional inhibitory concentration index (FICI) at 0.094 in K. pneumoniae F105-1 and 0.375 in P. mirabilis F11-2 (Figure 1A), suggesting a robust potentiation of BEN to TIG against plasmid-encoded TMexCD1-TOprJ1-expressing K. pneumoniae and intrinsic chromosomally-encoded TMexCD3-TOprJ3-positive P. mirabilis.

Figure 1.

Synergistic activity of tigecycline and benzydamine against temxCD-toprJ-bearing Gram-negative bacteria. (A) Benzydamine effectively synergized with tigecycline against temxCD1-toprJ1-positive and temxCD3-toprJ3-positive pathogens by checkerboard assays. Dark blue regions represent higher cell density. Data represent the mean OD (600 nm) of three biological replicates. Synergy is defined as an FIC index of ≤0.5. (B) Killing activity of TIG plus BEN in LB media against K. pneumoniae F105-1 harboring temxCD1-toprJ1 and P. mirabilis F11-2 harboring temxCD3-toprJ3. Data are representative of three biological replicates and presented as mean ± SD.

Next, we performed time-kill experiments to further investigate their synergistic bactericidal activity. Excitingly, the BEN plus TIG combination killed all pathogens with a dramatic reduction of bacterial loads by approximately 9-log10 after 24 h of incubation (Figure 1B). These results indicate that the combination of BEN and TIG displays potent bactericidal activity against various TMexCD-TOprJ-expressing Gram-negative bacteria.

2.2. BEN Prevents the Evolution of Tigecycline Resistance

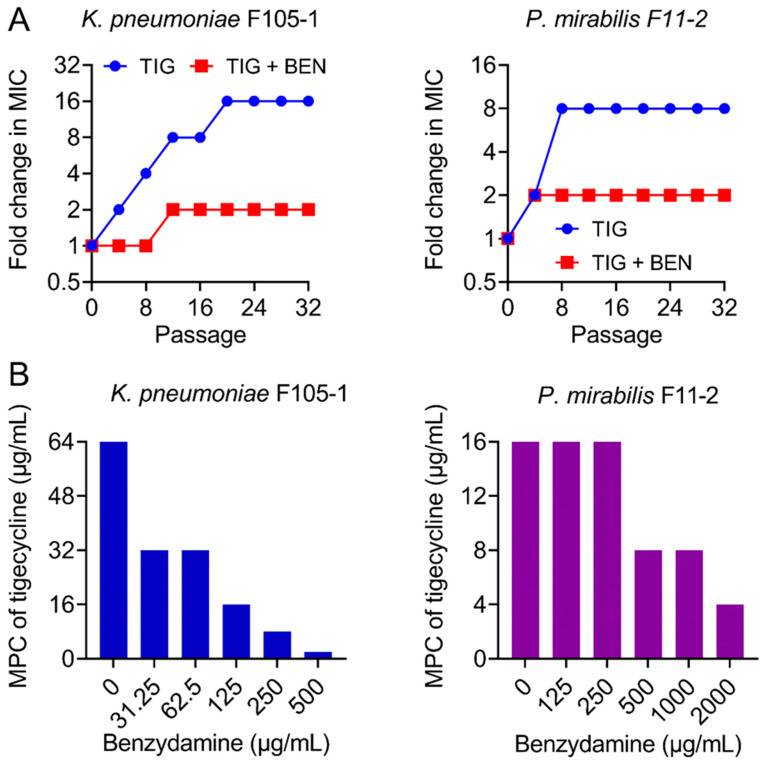

The ideal antibiotic adjuvant should also meet some additional criteria, including the suppression of resistance development [25]. Hence, after discovering the strong synergism of BEN and TIG, we next explored whether BEN could prevent the evolution of TIG resistance. We performed serial passages of two TMexCD-TOprJ-positive bacteria with sub-MICs of TIG in the presence or absence of BEN (one quarter of MIC). TIG resistance levels were greatly elevated upon exposure to TIG, as its MIC values increased by 16-fold (K. pneumoniae F105-1) and 8-fold (P. mirabilis F11-2) over a period of 32 serial passages (Figure 2A). By contrast, the resistance level increased by only 2-fold in the combination treatment. In addition, mutant prevention concentrations (MPCs) of TIG in the presence of increasing concentrations of BEN were determined, which is an important factor for characterizing the capacity of bacteria to generate drug-resistant mutants [26]. Interestingly, the MPCs of TIG were significantly reduced from 64 to 2 μg/mL in K. pneumoniae F105-1 and from 16 to 4 μg/mL in P. mirabilis F11-2 (Figure 2B), indicating narrower mutation selection windows in the presence of BEN. These data clearly demonstrate that BEN restricts resistance evolution in TMexCD-TOprJ-positive bacteria.

Figure 2.

Benzydamine prevents the evolution of tigecycline resistance. (A) TIG resistance acquisition curves in the presence of sub-inhibitory concentration of TIG or a combination of BEN and TIG against novel temxCD-toprJ-harboring Gram-negative bacteria during 32 serial passages. (B) Mutant prevention concentrations (MPCs) of TIG in the presence of increasing concentrations of BEN against temxCD-toprJ-positive Gram-negative bacteria. Data are representative of three biological replicates.

2.3. BEN Deprives the Function of Efflux Pump by Dissipating Proton Motive Force

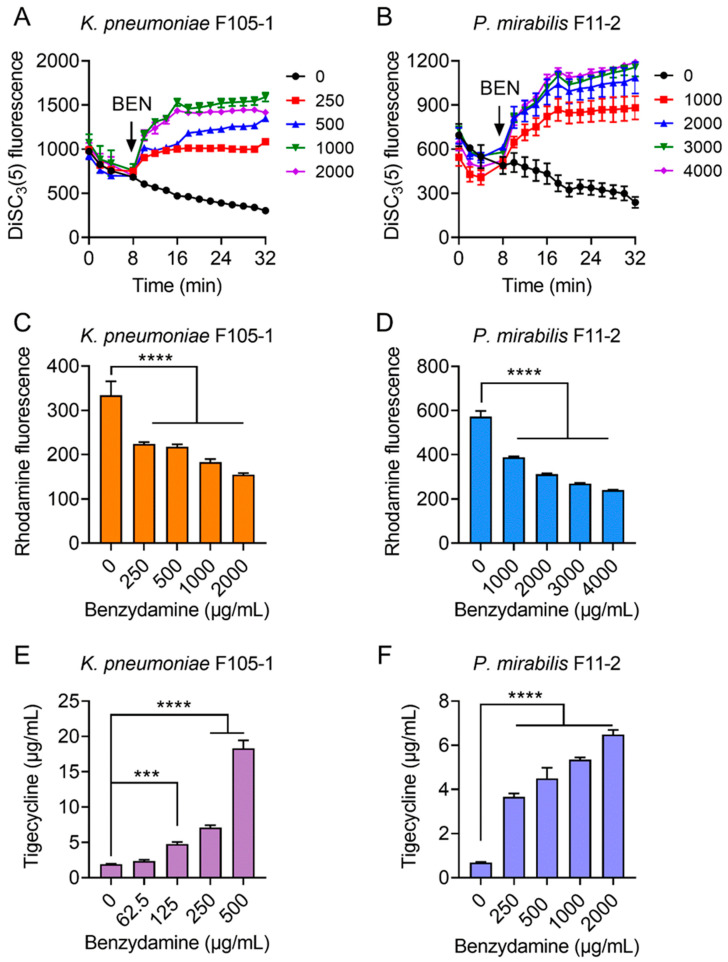

Considering that ATP synthesis is necessary for RND-type efflux pumps and that proton motive force (PMF) is the driving force for ATP production; thus, we hypothesized that BEN may dissipate bacterial PMF and thereby antagonize the efflux of TIG in TMexCD-TOprJ-positive bacteria. To test this hypothesis, we determined the PMF in bacteria after exposure to increasing concentrations of BEN by monitoring the fluorescence changes of DiSC3(5) [27]. PMF is composed of Δψ (the electrical potential) and ΔpH (the transmembrane difference) [28]. When the Δψ component of PMF is disrupted, DiSC3(5) is released from the cytoplasmic membrane to the extracellular milieu and fluorescence increases. Here, stationary-phase bacteria were stained with DiSC3(5) to measure fluorescence change and then cells were introduced to varying concentrations of BEN (0–2000 μg/mL for K. pneumoniae F105-1, 0–4000 μg/mL for P. mirabilis F11-2) (Figure 3A,B). Interestingly, the addition of BEN to probed cells caused increased fluorescence in a dose-dependent manner immediately, whereas the TIG alone showed no effect on the fluorescence, suggesting that BEN selectively disrupted the Δψ component of bacterial PMF.

Figure 3.

Tigecycline-benzydamine combination exerts synergy by dissipating bacterial proton motive force. (A,B) Membrane potential changes of in K. pneumoniae F105-1 (A) and P. mirabilis F11-2 (B) upon exposure to benzydamine, probed by potentiometric fluorophore DiSC3(5). (C,D) Function of efflux pump of K. pneumoniae F105-1 (C) and P. mirabilis F11-2 (D) carrying temxCD1-toprJ1 and temxCD3-toprJ3, respectively, after exposure to varying concentrations of benzydamine, measured by the fluorescence dye Rhodamine. (E,F) Intracellular accumulation of tigecycline in cells treated with benzydamine determined by LC-MS/MS analysis. Initial concentration of tigecycline was 32 μg/mL in K. pneumoniae F105-1 (E) and and 16 μg/mL in P. mirabilis F11-2 (F). All data are expressed as mean ± SD from three biological replicates and P values were determined by non-parametric one-way ANOVA (*** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001).

It is suggested that PMF is essential for energy synthesis and material transportation [29,30]; thus, we next tested whether the damage to bacterial PMF will affect the efflux function of TMexCD-TOprJ and promote the intracellular accumulation of TIG. A rhodamine-based assay was used to assess the capability of this new RND-type efflux pump in pathogens after treatment with different concentrations of BEN (Figure 3C,D). As expected, dose-dependent reduced effluxes of rhodamine in K. pneumoniae F105-1 and P. mirabilis F11-2 were observed, as in the presence of BEN. Furthermore, we measured the intracellular concentration of TIG in bacteria after treatment with BEN by LC-MS/MS analysis. The results indicated that TIG had notably accumulated in cells under the actions of BEN (Figure 3E,F). In the absence of BEN, low levels of TIG in bacteria were detected. By contrast, the intracellular concentrations of TIG were markedly increased, by nearly 20-fold in K. pneumoniae F105-1 and 6-fold in P. mirabilis F11-2 when incubated with BEN at 1× MIC. Together, these results demonstrate that the potentiating mechanisms of BEN to TIG in TMexCD-TOprJ-positive bacteria can be attributed to the destruction of bacterial PMF, which inhibits the functions of tmexCD-toprJ-encoded efflux pumps and promotes intracellular accumulation of TIG.

2.4. BEN Restores In Vivo Efficacy of Tigecycline

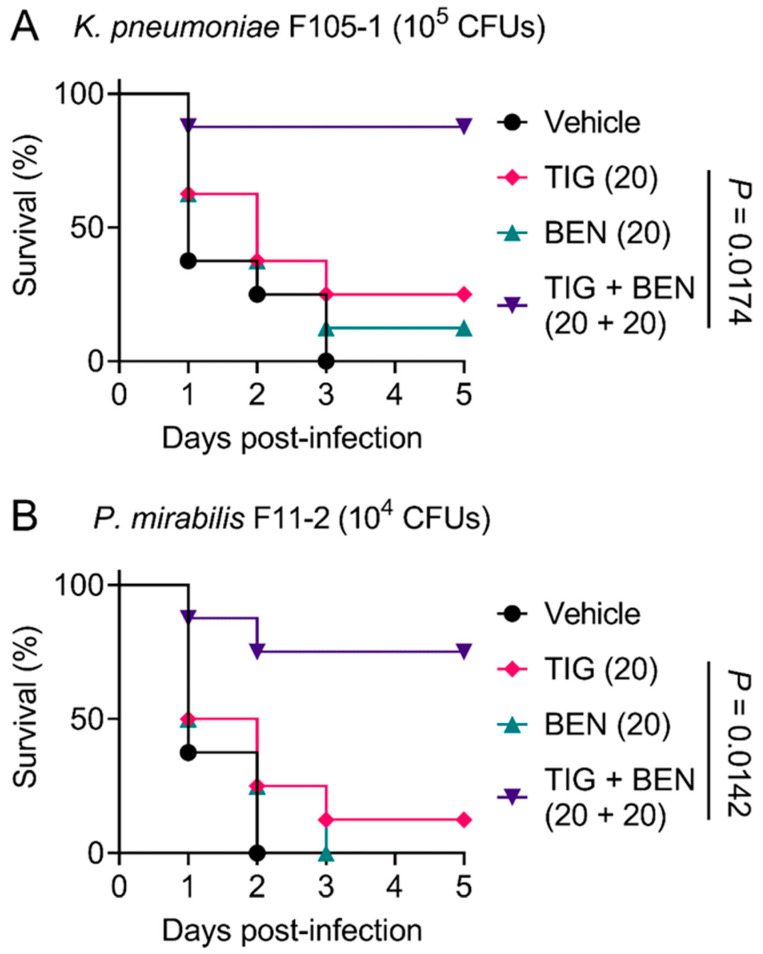

In view of the robust synergistic effect of TIG and BEN in the fight against TMexCD-TOprJ-positive pathogens in vitro, we further explored the therapeutic potential of this drug combination therapy using a Galleria mellonella infection model. Galleria mellonella larvae were infected with a lethal dose of K. pneumoniae F105-1 (105 CFUs) or P. mirabilis F11-2 (104 CFUs). The infected larvae were then treated with a vehicle (PBS) control, BEN or TIG monotherapy, or a combination of BEN and TIG. For the vehicle control, all larvae died within three days. With regard to monotherapy, BEN and TIG treatment both led to a larvae survival rate of less than 25%. In contrast, a single dose of BEN plus TIG (20 + 20 mg/kg) significantly increased the survival rate of larvae compared to TIG monotherapy (p = 0.0174 or 0.0142, respectively) at five days post-infection (Figure 4A,B). Given that K. pneumoniae is the main cause of pneumonia, pyogenic liver abscess, endophthalmitis and other metastatic infections [31], the combination of BEN and TIG may provide an alternative regimen for K. pneumoniae-elicited infections. These data strongly confirm the in vivo efficacy of this drug combination in combating infections caused by TMexCD-TOprJ-positive pathogenic bacteria.

Figure 4.

Benzydamine effectively improves tigecycline efficacy in Galleria mellonella infection model. Survival rates of Galleria mellonella larvae (n = 8 per group) infected by K. pneumoniae F105-1 (A) and P. mirabilis F11-2 (B) after treatment with PBS as vehicle, a single dose of benzydamine (BEN, 20 mg/kg), tigecycline (TIG, 20 mg/kg), or their combination. p values were determined by log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test.

3. Discussion

As a result of bacterial resistance to carbapenems and colistin, TIG is recognized as the last antibiotic of choice for the treatment of complicated infections caused by MDR Gram-negative pathogens [32,33]. However, the identification of the mobile genetic element tet(X3/X4) and tmexCD1-toprJ1 in clinically relevant pathogens from human and animal sources confers high levels of TIG resistance [8]. Notably, these novel TIG resistance genes are frequently located on the conjugative plasmids, which can transfer across intra- and inter-species, thus greatly accelerating the epidemic of antimicrobial resistance among various pathogens and posing a serious threat to public healthcare [34,35]. Alarmingly, there have been essentially no new classes of antibiotics or alternatives clinically approved in recent years. Thus, repurposing non-antibiotic agents as antibiotic adjuvants offers a promising strategy for addressing this troubling situation [36].

In this study, we found that the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug BEN reversed tmexCD-toprJ-mediated TIG resistance and remarkably potentiated the antibacterial activity of TIG against drug-resistant K. pneumoniae and P. mirabilis. Interestingly, although TIG is a bacteriostatic antibiotic, the combined use of BEN and TIG displayed potent bactericidal activity against TMexCD-TOprJ-positive bacteria in a time-dependent manner, highlighting the potency of this drug combination. The development and evolution of bacterial resistance to novel therapeutic strategies such as new antibiotics has been a huge challenge. Several previous studies reported that potent antibiotic adjuvants not only enhance antibiotic activity but also thwart the development of drug resistance [37,38]. Using similar assays, we demonstrated that the use of BEN substantially prevented the evolution of TIG resistance in TMexCD-TOprJ-positive bacteria and inhibited the enrichment of mutant subpopulations. Notably, the synergism potency of this drug combination has been verified in a Galleria mellonella infection model, which has been widely used to assess the therapeutic effectiveness of new antimicrobial agents owing to its various advantages, including convenience, low cost and a lack of ethical issues [39,40].

Investigations into the modes of action of BEN revealed that this compound dissipated the ΔΨ component of bacterial PMF and subsequently deprived the function of TMexCD-TOprJ-mediated novel RND-type efflux pumps, resulting in the intracellular accumulation of TIG. It is well known that TIG exhibits antibacterial activity by binding to the 30S ribosomal subunit and, finally, inhibiting protein synthesis [41]. Therefore, sufficient accumulation of TIG in cells is necessary for its actions. Interestingly, our findings showed BEN damaged the function of TMexCD-TOprJ efflux pumps by targeting bacterial PMF. Bacterial PMF play a crucial role in ATP synthesis, which in turn supports the energy source of efflux pumps [42]. Therefore, dissipating bacterial PMF contributes to combating efflux-mediated antibiotic resistance. Consistently, our previous study reported that metformin enhanced the antibacterial activity of doxycycline against tet(A)-positive pathogens by destroying the PMF in E. coli and promoting the intracellular uptake of doxycycline [19]. These findings strongly suggest that bacterial PMF may serve as a promising target for the identification of novel efflux pump inhibitors.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) Assays

MICs of all drugs were determined by the standard broth micro-dilution method in accordance with CLSI 2018 guidelines [43], using E. coli ATCC 25922 as the control. Generally, bacteria were cultured in LB broth overnight at 37 °C with 250 rpm sharking. All compounds were two-fold diluted in a 96-well microtiter plate (Corning, New York, NY, USA) containing 100 μL Mueller-Hinton broth (MHB, Qingdao Hope Bio-technology, Qingdao, China), followed by the addition of a prepared overnight bacteria culture (108 CFUs/mL). After incubation at 37 °C for 18 h, the MIC value was defined as the lowest concentration of drugs with no visible growth of bacteria. Wells with MHB were only used as negative controls and wells with no drugs were used as positive controls. Experiments were performed with two biological replicates.

4.2. Checkerboard Assays

To verify the synergistic activity between TIG and BEN, the checkerboard assays were conducted [12]. First, 100 μL MHB was dispensed into a 96-well microtiter plate, and then the BEN and TIG were serially diluted at eight concentrations to establish an 8 × 8 matrix. Then, 100 μL stationary-phase bacterial suspensions of K. pneumoniae F105-1 or P. mirabilis F11-2 were added. The cultures were incubated at 37 °C for 18 h, and then the optical density of bacteria at 600 nm was measured by Microplate reader (Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland). FIC index (FICI) was calculated according to the following formula: FICI = FICA + FICB = MICAB/MICA +MICBA/MICB; FICA and FICB are the FIC index of drug A and B, respectively; MICA and MICB are the MIC of drug A and B, respectively; MICAB and MICBA are the MIC of one drug in combination with another. Synergism is defined with an FICI of ≤0.5. Experiments were conducted with biological replicates.

4.3. Time-Dependent Killing Studies

Overnight K. pneumoniae F105-1 and P. mirabilis F11-2 cells were diluted 1/1000 into LB broth at 37 °C for 5 h. Cells were then treated with BEN or TIG alone or their combination for 24 h. Aliquots of bacterial culture were removed at 0, 4, 8 and 24 h of incubations and resuspended in sterile phosphate buffer saline (PBS, 0.01 M, pH = 7.4). Finally, suspensions were plated on Luria–Bertani (LB) medium and incubated overnight at 37 °C. Bacterial numbers were calculated. The concentrations of the drugs used were 32 μg/mL TIG and 500 μg/mL BEN for K. pneumoniae F105-1 assay and 16 μg/mL TIG and 2000 μg/mL BEN for P. mirabilis F11-2 assay. LB broth with no drugs were used as a control. Experiments were performed with three biological replicates.

4.4. Resistance Development Assessment

The resistance development study was performed according to a previous study [44]. Briefly, overnight cultures of bacteria (K. pneumoniae F105-1 or P. mirabilis F11-2) were diluted 1/1000 into LB broth containing 0.25 × MIC of TIG or in combination with 0.25 × MIC of BEN. After incubation at 37 °C for 12 h, the MIC of the cultures was determined. Meanwhile, a 1/1000 dilution of the bacteria culture was performed into fresh medium supplemented with 0.25 × MIC of drugs for the next passages. This experiment was performed for 32 passages and the MIC increase of tigecycline was calculated.

4.5. Mutant Prevention Concentration (MPC) Determination

The MPC assay was performed by a method described previously [45]. Bacteria (K. pneumoniae F105-1 or P. mirabilis F11-2) at 1010 CFUs were plated onto LB agar plates containing TIG alone or in combination with BEN at varying concentrations. Next, the plates were cultured in a 37 °C incubator for 72 h. The lowest concentration that restricted the growth of bacteria was defined as MPC. Experiments were performed with three biological replicates.

4.6. Proton Motive Force Assay

The proton motive force of K. pneumoniae F105-1 or P. mirabilis F11-2 treated by BEN was measured with fluorescence probe 3,3′-dipropylthiadicarbocyanine iodide (DiSC3(5)) [46]. Bacteria grown to stationary-phase were inoculated into 5 mL LB broth at 37 °C with 200 rpm shaking for 8 h. Cultures were washed three times with PBS and then the DiSC3(5) was added at a final concentration of 2 μM. Bacterial suspension was incubated with 200 rpm at 37 °C for 30 min, 180 μL samples were transferred in a black-walled plate and fluorescence was measured immediately in an Infinite M200 Microplate reader (Tecan) with an excitation wavelength of 622 nm and emission wavelength of 670 nm. DiSC3(5) measurement was obtained at every 2 min for 32 min and the different concentration of BEN was added at the 8th minute.

4.7. Efflux Pump Assay

The fluorescence dye Rhodamine B [47] was used to evaluate the effect of BEN on the function of tmexCD-toprJ-mediated efflux pumps. Stationary-phase K. pneumoniae F105-1 and P. mirabilis F11-2 were washed three times with PBS and a final concentration of Rhodamine B (5 μM for K. pneumoniae F105-1 and 20 μM for P. mirabilis F11-2) was added. Next, cultures were placed in an incubator with 200 rpm at 37 °C for 30 min. After washing with PBS three times, the bacterial suspension was centrifuged (4000× g, 5 min) and resuspended in PBS containing 1% glucose. A different concentration of the BEN solution was then added and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Finally, the bacteria were centrifuged at 4000× g for 10 min and then 200 μL was taken to determine the fluorescence intensity using Infinite M200 Microplate reader (excitation at 622 nm, emission at 670 nm).

4.8. Tigecycline Accumulation Analysis

The accumulation of TIG in K. pneumoniae F105-1 and P. mirabilis F11-2 was determined by LC-MS/MS analysis according to a previous report [48]. Firstly, overnight cultures of bacteria were inoculated in fresh LB broth and grown at 37 °C under continuous shaking at 200 rpm for 8 h to an optical density (OD600) of 0.5, then cells were pelleted by centrifuging at 12,000× g for 10 min and diluted into 1010 CFUs per mL by PBS; the suspension was aliquoted into 1.5 mL tubes. Next, TIG at the MIC concentration together with varying concentrations of BEN were added and bacteria were cultured at 37 °C with shaking at 200 rpm.

After 15 min, cultures were centrifuged at 12,000× g for 3 min. To lyse the samples, 300 µL water was mixed with each pellet and then placed in liquid nitrogen followed by heating in a water bath at 55 °C for three freeze-thaw cycles. To collect the supernatants, the lysates were pelted at 12,000× g for 3 min. Next, in order to completely lyse the bacteria, the residual debris were re-suspended in 100 µL of acetonitrile and pelleted. A 0.22 µm filter membrane was used to filter all supernatants. Finally, all supernatants were detected by an Agilent 1260 Infinity HPLC system combined with AB SCIEX QTRAP 6500 mass spectrometer (ABSciex, Foster City, CA, USA). The mobile phase contained 0.2% formic acid in water (A) and acetonitrile (B). The separation was experimented on a C18 column and the flow rate was 0.4 mL/min. The linear gradient was as follows: 0.1–0.5 min, 80% A; 0.5–0.55 min, 80–10% A; 0.55–4.0 min, 10% A; 4.0–4.5 min, 10–80% A; 4.5–6.0 min, 80% A. The quantification detection of TIG accumulation was analyzed by multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) with positive electrospray ionization using the m/z 586.4→513.3 transition.

4.9. Galleria mellonella Infection Model

Galleria mellonella larvae (purchased from Huiyude Biotech Company, Tianjin, China) were divided into serial groups (n = 8 per group). All larvae were infected with 105 CFUs K. pneumoniae F105-1 or 104 CFUs P. mirabilis F11-2 suspension. At 1 h post-infection, infected larvae were treated with PBS, TIG (20 mg/kg), BEN (20 mg/kg), or the combination of TIG with BEN (20 + 20 mg/kg). Survival rates of Galleria mellonella larvae were recorded for 5 days.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, we find that BEN greatly restores the TIG activity against TMexCD-TOprJ-positive pathogens both in vitro and in animal models of infection. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of a new TIG adjuvant in the fight against TMexCD-TOprJ-expressing microorganisms. Meanwhile, the addition of BEN also effectively thwarts the evolution of TIG resistance. These data suggest that BEN is a promising antibiotic adjuvant for combating novel RND efflux pump-conferred TIG resistance together with tigecycline. More preclinical studies are warranted to comprehensively explore the therapeutic potential of this drug combination.

Author Contributions

Y.L. and Z.W. conceived and designed the project; Z.T., T.X., T.D. and J.S. performed all experiments; Y.L. and Z.T. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32172907, 32002331 and 31872526), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province of China (BK20190893), Agricultural Science and Technology Independent Innovation Fund of Jiangsu Province (CX (20)3091 and CX(21)2010), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation funded project (2019M651984 and 2021T140579) and A Project Funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Yelin I., Kishony R. Antibiotic resistance. Cell. 2018;172:1136.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu Y., Tong Z., Shi J., Jia Y., Yang K., Wang Z. Correlation between exogenous compounds and the horizontal transfer of plasmid-borne antibiotic resistance genes. Microorganisms. 2020;8:1211. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8081211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Partridge S.R., Di Pilato V., Doi Y., Feldgarden M., Haft D.H., Klimke W., Kumar-Singh S., Liu J.-H., Malhotra-Kumar S., Prasad A., et al. Proposal for assignment of allele numbers for mobile colistin resistance (mcr) genes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018;73:2625–2630. doi: 10.1093/jac/dky262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tzouvelekis L.S., Markogiannakis A., Psichogiou M., Tassios P.T., Daikos G.L. Carbapenemases in Klebsiella pneumoniae and other enterobacteriaceae: An evolving crisis of global dimensions. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2012;25:682–707. doi: 10.1128/CMR.05035-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pankey G.A. Tigecycline. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2005;56:470–480. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sheu C.-C., Chang Y.-T., Lin S.-Y., Chen Y.-H., Hsueh P.-R. Infections caused by carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae: An update on therapeutic options. Front. Microbiol. 2019;10:80. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.He T., Wang R., Liu D., Walsh T., Zhang R., Lv Y., Ke Y., Ji Q., Wei R., Liu Z., et al. Emergence of plasmid-mediated high-level tigecycline resistance genes in animals and humans. Nat. Microbiol. 2019;4:1450–1456. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0445-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lv L.C., Wan M., Wang C.Z., Gao X., Yang Q.W., Partridge S.R., Wang Y., Zong Z.Y., Doi Y.H., Shen J.Z., et al. Emergence of a plasmid-encoded resistance-nodulation-division efflux pump conferring resistance to multiple drugs, including tigecycline, in Klebsiella pneumoniae. mBio. 2020;11:e02930-19. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02930-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun S., Gao H., Liu Y., Jin L., Wang R., Wang X., Wang Q., Yin Y., Zhang Y., Wang H. Co-existence of a novel plasmid-mediated efflux pump with colistin resistance gene mcr in one plasmid confers transferable multidrug resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020;9:1102–1113. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1768805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fang L., Chen C., Cui C., Li X., Zhang Y., Liao X., Sun J., Liu Y. Emerging high-level tigecycline resistance: Novel tetracycline destructases spread via the mobile tet(X) BioEssays. 2020;42:e2000014. doi: 10.1002/bies.202000014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park J., Gasparrini A.J., Reck M.R., Symister C.T., Elliott J.L., Vogel J.P., Wencewicz T.A., Dantas G., Tolia N.H. Plasticity, dynamics, and inhibition of emerging tetracycline resistance enzymes. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017;13:730–736. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Macnair C.R., Stokes J.M., Carfrae L.A., Fiebig-Comyn A.A., Coombes B.K., Mulvey M.R., Brown E.D. Overcoming mcr-1 mediated colistin resistance with colistin in combination with other antibiotics. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-02875-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li X.-Z., Plésiat P., Nikaido H. The challenge of efflux-mediated antibiotic resistance in Gram-negative bacteria. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2015;28:337–418. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00117-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Du D., Wang-Kan X., Neuberger A., Van Veen H.W., Pos K.M., Piddock L.J.V., Luisi B.F. Multidrug efflux pumps: Structure, function and regulation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018;16:523–539. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0048-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang C.-Z., Gao X., Yang Q.-W., Lv L.-C., Wan M., Yang J., Cai Z.-P., Liu J.-H. A novel transferable resistance-nodulation-division pump gene cluster, tmexCD2-toprJ2, confers tigecycline resistance in Raoultella ornithinolytica. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021;65:e02229-20. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02229-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Q., Peng K., Liu Y., Xiao X., Wang Z., Li R. Characterization of TMexCD3-TOprJ3, an RND-type efflux system conferring resistance to tigecycline in Proteus mirabilis, and its associated integrative conjugative element. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021;65 doi: 10.1128/AAC.02712-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tyers M., Wright G.D. Drug combinations: A strategy to extend the life of antibiotics in the 21st century. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019;17:141–155. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0141-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Y., Li R., Xiao X., Wang Z. Antibiotic adjuvants: An alternative approach to overcome multi-drug resistant Gram-negative bacteria. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2019;45:301–314. doi: 10.1080/1040841X.2019.1599813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Y., Jia Y., Yang K., Li R., Xiao X., Zhu K., Wang Z. Metformin restores tetracyclines susceptibility against multidrug resistant bacteria. Adv. Sci. 2020;7:1902227. doi: 10.1002/advs.201902227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Y., Jia Y., Yang K., Li R., Xiao X., Wang Z. Anti-HIV agent azidothymidine decreases Tet(X)-mediated bacterial resistance to tigecycline in Escherichia coli. Commun. Biol. 2020;3:1–10. doi: 10.1038/s42003-020-0877-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuriyama A., Aga M., Maeda H. Topical benzydamine hydrochloride for prevention of postoperative sore throat in adults undergoing tracheal intubation for elective surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Anaesthesia. 2018;73:889–900. doi: 10.1111/anae.14224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Son H.S., Lee J., Lee H.I., Kim N., Jo Y.-J., Lee G.-R., Hong S.-E., Kwon M., Kim N.Y., Kim H.J., et al. Benzydamine inhibits osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption via down-regulation of interleukin-1 expression. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 2020;10:462–474. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2019.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang X., Ye L., Chan E.W.-C., Zhang R., Chen S. Characterization of an IncFIB/IncHI1B plasmid encoding efflux pump TMexCD1-TOprJ1 in a clinical tigecycline- and carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae strain. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021;65 doi: 10.1128/AAC.02340-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wan M., Gao X., Lv L., Cai Z., Liu J.-H. IS 26 mediates the acquisition of tigecycline resistance gene cluster tmexCD1-toprJ1 by IncHI1B-FIB plasmids in Klebsiella pneumoniae and Klebsiella quasipneumoniae from food market sewage. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021;65 doi: 10.1128/AAC.02178-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Y., Tong Z., Shi J., Li R., Upton M., Wang Z. Drug repurposing for next-generation combination therapies against multidrug-resistant bacteria. Theranostics. 2021;11:4910–4928. doi: 10.7150/thno.56205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gianvecchio C., Lozano N.A., Henderson C., Kalhori P., Bullivant A., Valencia A., Su L., Bello G., Wong M., Cook E., et al. Variation in mutant prevention concentrations. Front. Microbiol. 2019;10:42. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu M., Maier E., Benz R., Hancock R. Mechanism of interaction of different classes of cationic antimicrobial peptides with planar bilayers and with the cytoplasmic membrane of Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1999;38:7235–7242. doi: 10.1021/bi9826299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stokes J.M., Yang K., Swanson K., Jin W., Cubillos-Ruiz A., Donghia N.M., Macnair C.R., French S., Carfrae L.A., Bloom-Ackermann Z., et al. A deep learning approach to antibiotic discovery. Cell. 2020;180:688–702. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Domenech A., Brochado A.R., Sender V., Hentrich K., Henriques-Normark B., Typas A., Veening J.-W. Proton motive force disruptors block bacterial competence and horizontal gene transfer. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;27:544–555.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Farha M.A., Verschoor C.P., Bowdish D., Brown E.D. Collapsing the proton motive force to identify synergistic combinations against Staphylococcus aureus. Chem. Biol. 2013;20:1168–1178. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lederman E.R., Crum N.F. Pyogenic liver abscess with a focus on Klebsiella pneumoniae as a primary pathogen: An emerging disease with unique clinical characteristics. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2005;100:322–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumarasamy K.K., Toleman M.A., Walsh T.R., Bagaria J., Butt F., Balakrishnan R., Chaudhary U., Doumith M., Giske C.G., Irfan S., et al. Emergence of a new antibiotic resistance mechanism in India, Pakistan, and the UK: A molecular, biological, and epidemiological study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2010;10:597–602. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70143-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu Y.-Y., Wang Y., Walsh T., Yi L.-X., Zhang R., Spencer J., Doi Y., Tian G., Dong B., Huang X., et al. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: A microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016;16:161–168. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00424-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomas C.M., Nielsen K.M. Mechanisms of, and barriers to, horizontal gene transfer between bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2005;3:711–721. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carattoli A. Plasmids and the spread of resistance. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2013;303:298–304. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pieren M., Tigges M. Adjuvant strategies for potentiation of antibiotics to overcome antimicrobial resistance. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2012;12:551–555. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Domalaon R., De Silva P.M., Kumar A., Zhanel G.G., Schweizer F. The Anthelmintic Drug Niclosamide synergizes with colistin and reverses colistin resistance in Gram-negative bacilli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019;63:e02574-18. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02574-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maisuria V.B., Okshevsky M., Déziel E., Tufenkji N. Proanthocyanidin interferes with intrinsic antibiotic resistance mechanisms of Gram-negative bacteria. Adv. Sci. 2019;6:1802333. doi: 10.1002/advs.201802333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Minrovic B.M., Jung D., Melander R.J., Melander C. New class of adjuvants enables lower dosing of colistin against Acinetobacter baumannii. ACS Infect. Dis. 2018;4:1368–1376. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.8b00103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hubble V.B., Hubbard B.A., Minrovic B.M., Melander R.J., Melander C. Using small-molecule adjuvants to repurpose azithromycin for use against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. ACS Infect. Dis. 2019;5:141–151. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.8b00288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chopra I., Roberts M. Tetracycline antibiotics: Mode of action, applications, molecular biology, and epidemiology of bacterial resistance. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2001;65:232–260. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.65.2.232-260.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mitchell P. Chemiosmotic coupling in oxidative and photosynthetic phosphorylation. Biol. Rev. 1966;41:445–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.1966.tb01501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute . Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. CLSI; Wayne, PA, USA: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Song M., Liu Y., Li T., Liu X., Hao Z., Ding S., Panichayupakaranant P., Zhu K., Shen J. Plant natural flavonoids against multidrug resistant pathogens. Adv. Sci. 2021;8:2100749. doi: 10.1002/advs.202100749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun H., Zhang Q., Wang R., Wang H., Wong Y.-T., Wang M., Hao Q., Yan A., Kao R.Y.-T., Ho P.-L., et al. Resensitizing carbapenem- and colistin-resistant bacteria to antibiotics using auranofin. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18939-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taber H.W., Mueller J.P., Miller P.F., Arrow A.S. Bacterial uptake of aminoglycoside antibiotics. Microbiol. Rev. 1987;51:439–457. doi: 10.1128/mr.51.4.439-457.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Forster S., Thumser A.E., Hood S.R., Plant N. Characterization of Rhodamine-123 as a tracer dye for use in in vitro drug transport assays. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e33253. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xie J., Wang T., Wang X., Cheng X., Dong H., Wang Y., Zheng X., Zhou L., Xing J., Dong Y. Quantitative analysis and pharmacokinetics study of tigecycline in human serum using a validated sensitive liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry method. J. Sep. Sci. 2014;37:1396–1403. doi: 10.1002/jssc.201400152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.