Abstract

Three novel fungal species, Talaromyces gwangjuensis, T. koreana, and T. teleomorpha were found in Korea during an investigation of fungi in freshwater. The new species are described here using morphological characters, a multi-gene phylogenetic analysis of the ITS, BenA, CaM, RPB2 regions, and extrolite data. Talaromyces gwangjuensis is characterized by restricted growth on CYA, YES, monoverticillate and biverticillate conidiophores, and globose smooth-walled conidia. Talaromyces koreana is characterized by fast growth on MEA, biverticillate conidiophores, or sometimes with additional branches and the production of acid on CREA. Talaromyces teleomorpha is characterized by producing creamish-white or yellow ascomata on OA and MEA, restricted growth on CREA, and no asexual morph observed in the culture. A phylogenetic analysis of the ITS, BenA, CaM, and RPB2 sequences showed that the three new taxa form distinct monophyletic clades. Detailed descriptions, illustrations, and phylogenetic trees are provided.

Keywords: three new taxa, Trichocomaceae, morphology, phylogeny, taxonomy

1. Introduction

The genus Talaromyces was established by Benjamin (1955) [1] for a teleomorph of Penicillium with Talaromyces vermiculatus (=T. flavus) as the type species. These species are characterized by cleistothecial or gymnothecial ascomata, unitunicate eight-spored asci, and unicellular ascospores with or without equatorial crests. The anamorphs have predominantly biverticillate or rarely terverticillate conidiophores with acerose phialides and narrow collulum [2,3]. In 2011, Samson et al. [2] transferred all accepted species of Penicillium subgen. Biverticillium to Talaromyces on the basis of a two-gene phylogeny. Subsequently, Yilmaz et al. [3] studied the taxonomy of Talaromyces in detail using the polyphasic species concept. On the basis of multigene phylogeny, morphology, and physiology, Yilmaz et al. [3] placed 88 accepted species in seven well-defined sections, namely, Bacillispori, Helici, Islandici, Purpurei, Subinflati, Talaromyces, and Trachyspermi. However, the lists are rapidly increasing with many new Talaromyces species recently described from all over the world and added to sections Helici, Islandici, Purpurei, Subinflati, Talaromyces, and Trachyspermi [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. To date, 171 species have been reported in the genus Talaromyces [27], of which only three species: Talaromyces angelicae, Talaromyces cnidii, and Talaromyces halophytorum were reported from Korea [28,29]. Recently, a new section Tenues was proposed [26]. Talaromyces contains species that play an important role in agriculture and biotechnology. Talaromyces rugulosus (Basionym: Penicillum rugulosum) produces β-rutinosidase and phosphatase [30,31], T. pinophilus (Basionym: Penicillium pinophilum) produces endoglucanase and cellulase [32], and T. funiculosus (Basionym: Penicillium funiculosum) produces cellulases [33]. Talaromyces purpureogenus can produce extracellular enzymes and red pigment and also produces mycotoxin such as rubratoxin A and B and luteoskyrin [34]. Additionally, red pigments produced in large amounts by T. atroroseus can be used as colorants in the food industry [35]. Furthermore, the ability to produce various important compounds makes them candidates for the biocontrol of soilborne fungal pathogens such as an antagonists of T. flavus against Verticillium spp., Rhizoctonia solani, and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum [36,37,38,39,40]. In addition, some species are medically important, such as T. wortmannii, which can produce compound C that was found to be an effective antimicrobial against Propionibacterium acnes and had anti-inflammatory properties and, thus, represents alternative treatments for antibiotic or anti-inflammatory therapy for acne [41]. Talaromyces marneffei (Basionym: Penicillium marneffei) causes a fatal mycosis in immunocompromised individuals [42,43].

Section Helici was proposed by Yilmaz et al. [3] with seven Talaromyces species divided into two clades: a main clade containing T. helicus, T. boninensis, and T. varians and a second clade containing T. cinnabarinus, T. aerugineus, T. bohemicus, and T. ryukyuensis. The Talaromyces species included in this section are characterized by producing biverticillate conidiophores occasionally consisting of solitary phialides with stipes generally pigmented, yellowish-brown, or dark green reversed on CYA; grown at 37 °C, and the absence of acid production on CREA [3]. Section Helici currently includes 13 species [27].

Section Purpurei was proposed by Stolk and Samson [44] to accommodate species that produce synnemata after two to three weeks of incubation, with the exception of T. rademirici, T. purpureus, and T. ptychoconidium. The species in this section generally do not grow or grow poorly on creatine sucrose agar (CREA), and grow restrictedly on Czapek yeast extract agar (CYA) and yeast extract sucrose agar (YES) and slightly faster on malt extract agar (MEA) [3]. Ten species were accepted in the section Purpurei: T. cecidicola, T. chloroloma, T. coalescens, T. dendriticus, T. pseudostromaticus, T. pittii, T. purpureus, T. ptychoconidium, T. rademirici, and T. ramulosus [3], but it currently contains 12 species [27].

Freshwater fungi are an ubiquitous and diverse group of organisms and play an important role in ecological systems [45]. Hawksworth [46] estimated that there are approximately 1.5 million fungal species on Earth. However, an updated estimate of the number of fungal species is between 2.2 and 3.8 million [47]. Of the ca. 150,000 known sepecies, only around 3000 have been reported from aquatic habitats [48], with more than 600 species of ascomycetes reported in freshwater [49]. Thus, a large number of species are still waiting to be discovered and described in freshwater habitats.

Up to now, only a few freshwater fungi, especially genus Talaromyces, have been reported in Korea. The purpose of this study was to expand the present knowledge of these fungal taxa in Korea. Here, we describe and illustrate three new Talaromyces species from freshwater habitats in Korea.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling and Isolation

In January and May 2017, freshwater samples were collected from the Wonhyo Valley located at Mudeung Mt., Gwangju, and Jukrim Reservoir located in Yeosu, Korea. These samples were transported to the laboratory in sterile 50-mL conical tubes and stored at 4 °C pending examination. Before culture preparation, all samples were diluted with sterile distilled water to reduce the density and improve strain recovery. Briefly, each sample was shaken for 15 min at room temperature, and a 100-μL aliquot of each sample was mixed with 9 mL of sterile distilled water. Then, serial dilutions of the mixture (from 10−1 to 10−4) were made. A 100-μL aliquot of each dilution was spread on potato dextrose agar (PDA: 39 g of potato dextrose agar in 1 L of deionized water; Becton, Dickinson, and Co., Sparks, MD, USA) supplemented with the antibiotic streptomycin (final concentration, 50 ppm; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The petri plates were incubated at 25 °C for 5–10 days. Pure isolates were obtained by selecting individual colonies of varied morphologies, transferring them to PDA plates, and subculturing until pure cultures were obtained. Ex-type living cultures were deposited in the Environmental Microbiology Laboratory Fungarium, Chonnam National University (CNUFC), Gwangju, Korea. Dried cultures were deposited in the Herbarium Chonnam National University, Gwangju, Korea.

2.2. Morphology

The strains were three-point inoculated onto Czapek yeast autolysate agar (CYA), malt extract agar (MEA), yeast extract sucrose agar (YES), oatmeal agar (OA), dichloran 18% glycerol (DG18) agar, CYA supplemented with 5% NaCl (CYAS), and creatine sucrose agar (CREA). All petri dishes were incubated at 20, 25, 30, 35, 37, and 40 °C for 7 days. Medium preparation and inoculation were performed according to the methods reported by Yilmaz et al. [3]. Colony characters were recorded after 7 days. Lactic acid (60%) was used as the mount fluid, and 96% ethanol was used to remove excess conidia. The Olympus BX51 microscope with differential interference contrast optics (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was used to obtain digital images. For scanning electron microscopy (SEM), the samples were performed as described previously by Nguyen et al. [50].

2.3. DNA Extraction, PCR, and Sequencing

The fungal isolates were cultured on PDA overlaid with cellophane at 25 °C for 5–7 days. Genomic DNA was extracted using the SolgTM Genomic DNA Preparation Kit (Solgent Co. Ltd., Daejeon, Korea). The ITS region was amplified using the primer pairs ITS 1 and ITS 4 [51]. The beta-tubulin (BenA) was amplified using the primer pairs T10 and Bt2b [52]. The calmodulin (CaM) gene was amplified using the primer pairs CMD5/CMD6 and CF1/CF4 [53,54]. To amplify the RPB2 gene region, the primer pairs RPB2-5F and RPB2-7cR were used [55]. PCR amplification was performed according to the conditions described by Yilmaz et al. [3] and Houbraken and Samson [56]. The PCR products were purified with the Accuprep PCR Purification Kit (Bioneer Corp., Daejeon, Korea). Sequencing was performed using the same PCR primers and run on the ABI PRISM 3730XL Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

2.4. Molecular Analysis

Each generated sequence was checked for the presence of ambiguous bases and assembled using the Lasergene SeqMan program from DNASTAR, Inc. (Madison, WI, USA). Edited sequences were blasted against the NCBI GenBank nucleotide database (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi; 2 January 2021) to search for the closest relatives. The sequences of all the accepted Talaromyces species were retrieved from GenBank. The sequences were aligned using MAFFT (https://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server; 9 March 2021) [57], and the resulting alignment was trimmed using trimAl [58] and subsequently combined with MEGA 7 [59]. The data were converted from a FASTA format to nexus and phylip formats using the online tool Alignment Transformation Environment (https://sing.ei.uvigo.es/ALTER/; 9 March 2021) [60]. Phylogenetic reconstructions by maximum likelihood (ML) were carried out using RAxML-HPC2 on XSEDE on the online CIPRES Portal (https://www.phylo.org/portal2; 9 March 2021) with 1000 bootstrap replicates and the GTRGAMMA model of nucleotide substitution. A Bayesian inference analysis was performed with MrBayes 3.2.2 [61] using a Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm. The sample frequency was set to 100, and the first 25% of trees were removed as burn-in. The trees were visualized using FigTree v. 1.3.1 [62]. Support values were provided at the branches (ML bootstrap support (BS) and BI posterior probability (PP)). Talaromyces tenuis CBS 141840 was chosen as the outgroup in the sections Helici and Purpurei phylogenies. Trichocoma paradoxa CBS 788.83 was the outgroup for the combined phylogeny of the species from Talaromyces. The newly obtained sequences were deposited in the GenBank database under the accession numbers provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Accession numbers for the fungal strains used for the phylogenetic analysis.

| Taxon Name | Strain No. | GenBank Accession No. | References | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | BenA | CaM | RPB2 | |||

| T. aerugineus | CBS 350.66 T | AY753346 | KJ865736 | KJ885285 | JN121502 | [3] |

| T. apiculatus | CBS 312.59 T | JN899375 | KF741916 | KF741950 | KM023287 | [3] |

| T. atricola | CBS 255.31 T | KF984859 | KF984566 | KF984719 | KF984948 | [3] |

| T. atroroseus | CBS 133442 T | KF114747 | KF114789 | KJ775418 | KM023288 | [3] |

| T. austrocalifornicus | CBS 644.95 T | JN899357 | KJ865732 | KJ885261 | MN969147 | [3,27] |

| T. bacillisporus | CBS 296.48 T | KM066182 | AY753368 | KJ885262 | JF417425 | [3] |

| T. bohemicus | CBS 545.86 T | JN899400 | KJ865719 | KJ885286 | JN121532 | [3] |

| T. boninensis | CBS 650.95 T | JN899356 | KJ865721 | KJ885263 | KM023276 | [3] |

| T. borbonicus | CBS 141340 T | MG827091 | MG855687 | MG855688 | MG855689 | [20] |

| T. brunneosporus | FMR 16566 T | LT962487 | LT962483 | LT962488 | LT962485 | [24] |

| T. cecidicola | CBS 101419 T | AY787844 | FJ753295 | KJ885287 | KM023309 | [3] |

| T. cinnabarinus | CBS 267.72 T | JN899376 | AY753377 | KJ885256 | JN121477 | [3] |

| T. cinnabarinus | CBS 357.72 | – | KM066134 | – | – | [3] |

| T. chlamydosporus | CBS 140635 T | KU866648 | KU866836 | KU866732 | KU866992 | [5] |

| T. chlorolomus | DAOM 241016 T | FJ160273 | GU385736 | KJ885265 | KM023304 | [3,27] |

| T. chlorolomus | DTO 180-F4 | – | FJ753294 | – | – | [3] |

| T. chlorolomus | DTO 182-A5 | – | JX091597 | – | – | [3] |

| T. cnidii | KACC 46617 T | KF183639 | KF183641 | KJ885266 | KM023299 | [3,28] |

| T. cinnabarinus | CBS 267.72 T | JN899376 | AY753377 | KJ885256 | JN121477 | [3] |

| T. cinnabarinus | CBS 357.72 | – | KM066134 | – | – | [3] |

| T. coalescens | CBS 103.83 T | JN899366 | JX091390 | KJ885267 | KM023277 | [3] |

| T. columbinus | NRRL 58811 T | KJ865739 | KF196843 | KJ885288 | KM023270 | [3] |

| T. dendriticus | CBS 660.80 T | JN899339 | JX091391 | KF741965 | KM023286 | [3] |

| T. dendriticus | DAOM 226674 | – | FJ753293 | – | – | [3] |

| T. dendriticus | DAOM 233861 | – | FJ753294 | – | – | [3] |

| T. derxii | CBS 412.89 T | JN899327 | JX494306 | KF741959 | KM023282 | [3,27] |

| T. diversiformis | CBS 141931 T | KX961215 | KX961216 | KX961259 | KX961274 | [11] |

| T. diversus | CBS 320.48 T | KJ865740 | KJ865723 | KJ885268 | KM023285 | [3] |

| T. duclauxii | CBS 322.48 T | JN899342 | JX091384 | KF741955 | JN121491 | [3] |

| T. emodensis | CBS 100536 T | JN899337 | KJ865724 | KJ885269 | JF417445 | [27] |

| T. erythromellis | CBS 644.80 T | JN899383 | HQ156945 | KJ885270 | KM023290 | [3] |

| T. euchlorocarpius | DTO 176-I3 T | AB176617 | KJ865733 | KJ885271 | KM023303 | [3] |

| T. flavus | CBS 310.38 T | JN899360 | JX494302 | KF741949 | JF417426 | [3] |

| T. fusiformis | CBS 140637 T | KU866656 | KU866843 | KU866740 | KU867000 | [5] |

| T. georgiensis | DI16-145 T | LT558967 | LT559084 | – | LT795606 | [12] |

| T. gwangjuensis | CNUFC WT19-1 T | MK766233 | MZ318448 | – | MK912174 | This study |

| T. gwangjuensis | CNUFC WT19-2 | MK766234 | MZ318449 | – | MK912175 | This study |

| T. helicus | CBS 335.48 T | JN899359 | KJ865725 | KJ885289 | KM023273 | [3] |

| T. helicus | CBS 134.67 | – | KM066133 | – | – | [3] |

| T. iowaense | NRRL 66822 T | MH281565 | MH282578 | MH282579 | MH282577 | [17] |

| T. islandicus | CBS 338.48 T | KF984885 | KF984655 | KF984780 | KF985018 | [3] |

| T. korena | CNUFC YJW2-13 T | MZ315100 | MZ318450 | MZ332529 | MZ332533 | This study |

| T. korena | CNUFC YJW2-14 | MZ315101 | MZ318451 | MZ332530 | MZ332534 | This study |

| T. mimosinus | CBS 659.80 T | JN899338 | KJ865726 | KJ885272 | MN969149 | [3,27] |

| T. minioluteus | CBS 642.68 T | JN899346 | MN969409 | KJ885273 | JF417443 | [3] |

| T. palmae | CBS 442.88 T | JN899396 | HQ156947 | KJ885291 | KM023300 | [3] |

| T. piceus | CBS 361.48 T | KF984792 | KF984668 | KF984680 | KF984899 | [3] |

| T. pigmentosus | CBS 142805 T | MF278330 | LT855562 | LT855565 | LT855568 | [15] |

| T. pittii | CBS 139.84 T | JN899325 | KJ865728 | KJ885275 | KM023297 | [3] |

| T. proteolyticus | CBS 303.67 T | JN899387 | KJ865729 | KJ885276 | KM023301 | [3] |

| T. pseudostromaticus | CBS 470.70 T | JN899371 | HQ156950 | KJ885277 | KM023298 | [3] |

| T. ptychoconidius | DAOM 241017 T | FJ160266 | GU385733 | JX140701 | KM023278 | [3,27] |

| T. ptychoconidius | DTO 180-E9 | – | GU385734 | – | – | [3] |

| T. ptychoconidius | DTO 180-F1 | – | GU385735 | – | – | [3] |

| T. purpureogenus | CBS 286.36 T | JN899372 | JX315639 | KF741947 | JX315709 | [3,27] |

| T. purpureus | CBS 475.71 T | JN899328 | GU385739 | KJ885292 | JN121522 | [3] |

| T. rademirici | CBS 140.84 T | JN899386 | KJ865734 | KM023302 | [3] | |

| T. radicus | CBS 100489 T | KF984878 | KF984599 | KF984773 | KF985013 | [3] |

| T. ramulosus | DAOM 241660 T | EU795706 | FJ753290 | JX140711 | KM023281 | [3] |

| T. ramulosus | DTO 182-A6 | – | JX091631 | – | – | [3] |

| T. ramulosus | DTO 181-E3 | – | JX091626 | – | – | [3] |

| T. ramulosus | DTO 182-A3 | – | JX091630 | – | – | [3] |

| T. reverso-olivaceus | CBS 140672 T | KU866646 | KU866834 | KU866730 | KU866990 | [5] |

| T. rotundus | CBS 369.48 T | JN899353 | KJ865730 | KJ885278 | KM023275 | [3] |

| T. rugulosus | CBS 371.48 T | KF984834 | KF984575 | KF984702 | KF984925 | [3] |

| T. ryukyuensis | NHL 2917 T | AB176628 | – | – | – | [3] |

| T. stipitatus | CBS 375.48 T | JN899348 | KM111288 | KF741957 | KM023280 | [3] |

| T. subinflatus | CBS 652.95 T | JN899397 | MK450890 | KJ885280 | KM023308 | [3,27] |

| T. tabacinus | NRRL 66727 T | MG182613 | MG182627 | MG182606 | MG182620 | [17] |

| T. tardifaciens | CBS 250.94 T | JN899361 | KF984560 | KF984682 | KF984908 | [27] |

| T. teleomorpha | CNUFC YJW2-5 T | MZ315102 | MZ318452 | MZ332531 | MZ332535 | This study |

| T. teleomorpha | CNUFC YJW2-6 | MZ315103 | MZ318453 | MZ332532 | MZ332536 | This study |

| T. tenuis | CBS 141840 T | MN864275 | MN863344 | MN863321 | MN863333 | [26] |

| T. trachyspermus | CBS 373.48 T | JN899354 | KF114803 | KJ885281 | JF417432 | [3] |

| T. tratensis | CBS 133146 T | KF984891 | KF984559 | KF984690 | KF984911 | [3] |

| T. ucrainicus | CBS 162.67 T | JN899394 | KF114771 | KJ885282 | KM023289 | [3] |

| T. unicus | CBS 100535 T | JN899336 | KJ865735 | KJ885283 | MN969150 | [27] |

| T. varians | CBS 386.48 T | JN899368 | KJ865731 | KJ885284 | KM023274 | [3] |

| T. verruculosus | NRRL 1050 T | KF741994 | KF741928 | KF741944 | KM023306 | [27] |

| T. viridulus | CBS 252.87 T | JN899314 | JX091385 | KF741943 | JF417422 | [3] |

| Trichocoma paradoxa | CBS 788.83 T | JN899398 | KF984556 | KF984670 | JN121550 | [3] |

CBS: Culture collection of the Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute, The Netherlands. CNUFC: Chonnam National University Fungal Collection, Gwangju, South Korea; DAOM: Agriculture Canada and Agri-Food Canada Culture Collection, Ottawa, ON, Canada; DTO: Internal Culture Collection of the CBS-Fungal Biodiversity Centre; FMR: Facultat de Medicina i Ciencies de la Salut, Reus, Spain; KACC: Korean Agricultural Culture Collection, Republic of Korea; NRRL: Agricultural Research Service Culture Collection, Peoria, IL, USA; T: ex-type strain.

2.5. Extrolite Analysis

Extrolites were extracted from Talaromyces strains after growing on CYA, YES, and MEA for 7–10 days at 25 °C. The extracts were prepared and analyzed as previously described by Frisvad and Thrane [63], Nielsen et al. [64], and Houbraken et al. [65].

3. Results

3.1. Phylogenetic Analysis

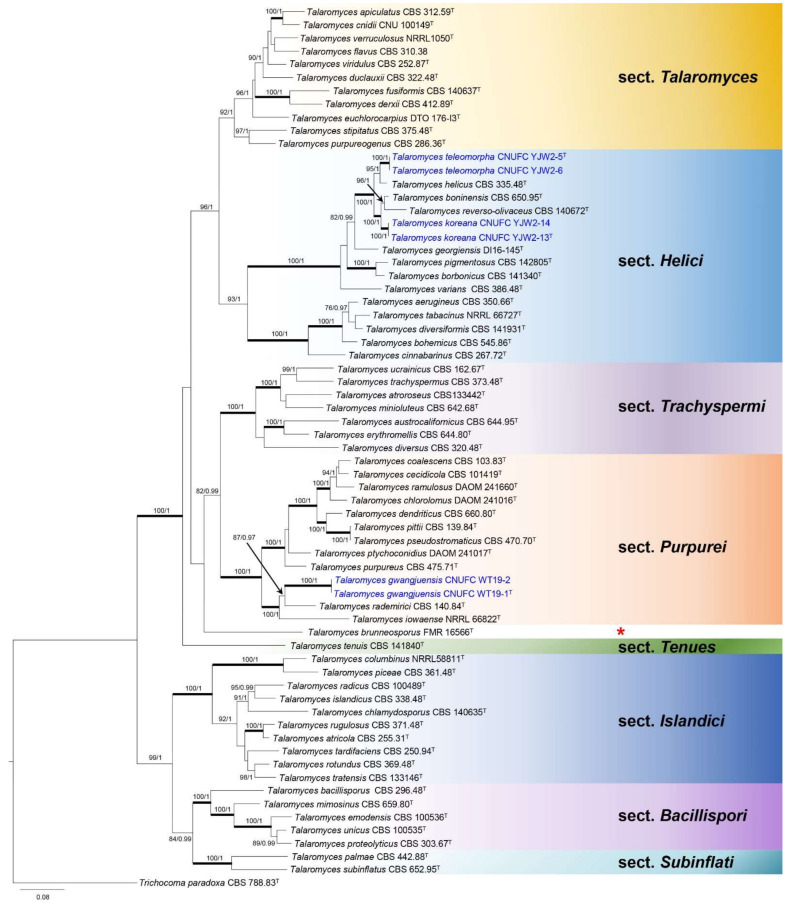

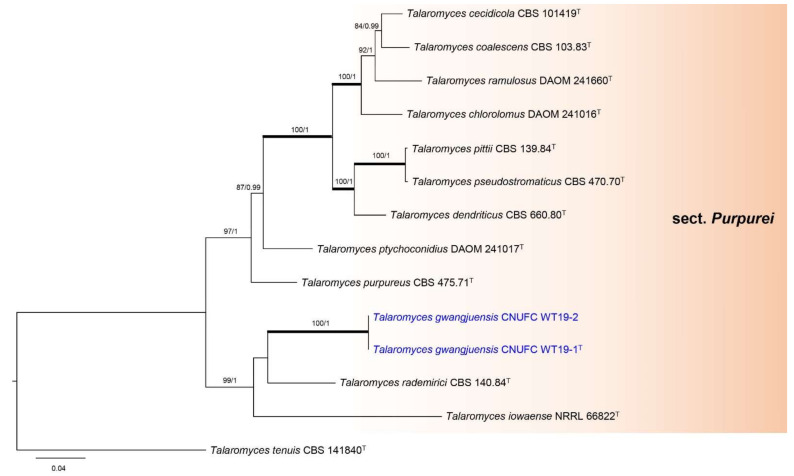

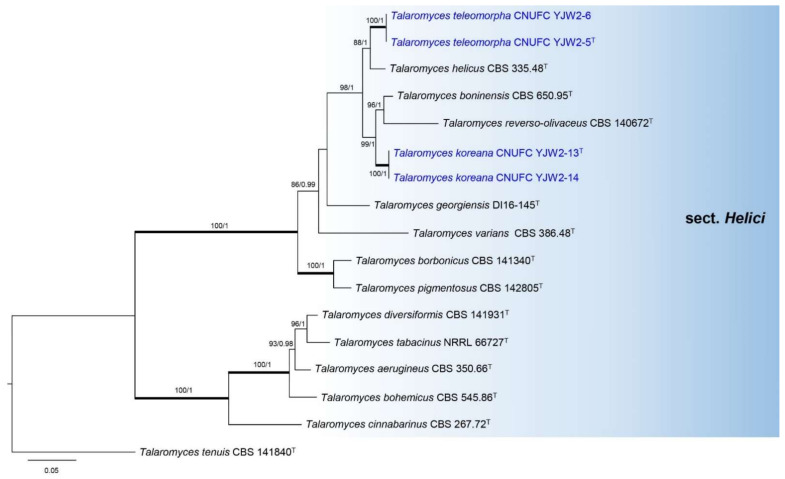

Phylogenetic relationships within Talaromyces were studied using a concatenated dataset of four loci (ITS, BenA, CaM, and RPB2) (Figure 1). The multigene analysis contained 67 taxa, including Trichocoma paradoxa CBS 788.83 as the outgroup taxon. The concatenated alignment consisted of 2407 characters (including alignment gaps): 425, 443, 687, and 852 characters used in the ITS, BenA, CaM, and RPB2, respectively. Eight main lineages are present within Talaromyces, which agrees with the sectional classification by Yilmaz et al. [3] and Sun et al. [26]. In the phylogenetic analysis, a small clade containing T. brunneosporus highlighted by asterisk could not be assigned to any known sections (Figure 1). Talaromyces gwangjuensis, T. koreana, and T. teleomorpha belong to sections Purpurei and Helici, according to our multigene analysis (Figure 1). In section Purpurei, T. gwangjuensis clustered close to but separated from T. rademirici in the single (BenA, RPB2, and ITS) and combined phylogenies (Figure 2 and Figures S1–S3). Talaromyces teleomorpha is close to T. helicus in BenA, ITS, and combined phylogenies (Figure 3, Figures S4 and S5) but placed among T. helicus, T. koreana, T. reverso-olivaceus, and T. boninensis in the CaM and RPB2 phylogenies (Figures S6 and S7). Talaromyces koreana was found to be related to T. reverso-olivaceus and T. boninensis in BenA, CaM, RPB2, and the combined phylogenies (Figure 3, Figures S4, S6, and S7). In the ITS phylogenetic analysis, T. koreana was close to only T. boninensis (Figure S5).

Figure 1.

Phylogram generated from the Maximum Likelihood (RAxML) analysis based on the combined ITS, BenA, CaM, and RPB2 sequences data of Talaromyces. The red asterisk represents a separate lineage which is not assigned yet. The branches with values = 100% ML BS and 1 PP are highlighted by thickened branches. The branches with values ≥70% ML BS and ≥0.95 PP indicated above or below branches. Trichocoma paradoxa CBS 788.83 was the group was used as the outgroup. The newly generated sequences are indicated in blue. T = ex-type.

Figure 2.

Phylogram generated from the Maximum Likelihood (RAxML) analysis based on the combined ITS, BenA, CaM, and RPB2 sequences data for species classified in Talaromyces section Purpurei. The branches with values = 100% ML BS and 1 PP are highlighted by thickened branches. The branches with values ≥70% ML BS and ≥0.95 PP indicated above or below branches. Talaromyces tenuis CBS 141840 was used as the outgroup. The newly generated sequences are indicated in blue. T = ex-type.

Figure 3.

Phylogram generated from the Maximum Likelihood (RAxML) analysis based on combined the ITS, BenA, CaM, and RPB2 sequence data for the species classified in Talaromyces section Helici. The branches with values = 100% ML BS and 1 PP are highlighted by thickened branches. The branches with values ≥70% ML BS and ≥0.95 PP indicated above or below branches. Talaromyces tenuis CBS 141840 was used as the outgroup. The newly generated sequences are indicated in blue. T = ex-type.

3.2. Taxonomy

Talaromycesgwangjuensis Hyang B. Lee & T.T.T. Nguyen sp. nov.

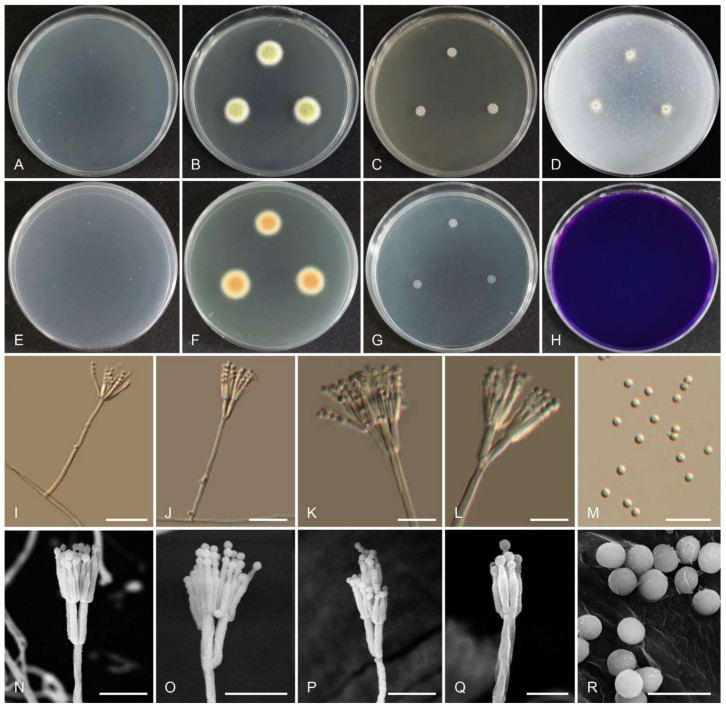

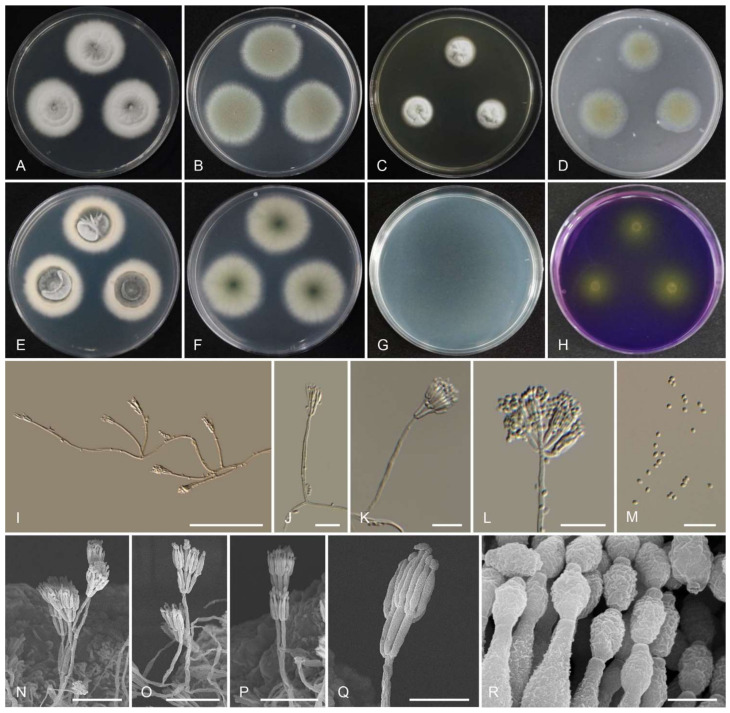

Index Fungorum: IF554801 (Figure 4 and Table 2).

Figure 4.

Morphology of Talaromyces gwangjuensis CNUFC WT19-1. (A,E) Colonies on Czapeck yeast autolysate agar (CYA). (B,F) Malt extract agar (MEA). (C) Yeast extract sucrose agar (YES). (D) Oatmeal agar (OA). (G) Dichloran 18% glycerol agar (DG 18). (H) Creatine sucrose agar (CREA). ((A–D,G,H) Obverse view and (E,F) reverse view). (I–L,N–Q) Conidiophores. (M,R) Conidia. ((I–M) LM and (N–R) SEM). Scale bars: (I–M) = 20 μm, (N–Q) = 10 μm, and (R) = 5 μm.

Table 2.

Morphological characteristics of Talaromyces gwangjuensis CNUFC WT19-1 compared with those of the reference strain Talaromyces rademirici.

| Characteristics | CNUFC WT19-1 Isolated in This Study | Talaromyces rademirici a |

|---|---|---|

| Size after 7 days at 25 °C (diameter) | <1 mm on CYA | 5–6 mm on CYA |

| 3–5 mm on YES | 5–6 mm on YES | |

| 13–15 mm on MEA | 14–16 mm on MEA | |

| 6–7 mm on OA | 9–10 mm on OA | |

| No growth on CREA | No growth on CREA | |

| Size after 7 days at 37 °C on CYA (diameter) | No growth | 3 mm |

| Conidiophores | Biverticillate and monoverticillate, 39–174 × 1.5–3 µm | Biverticillate and monoverticillate; stipes smooth-walled, 25–95 × 1.5–2.5 μm; branches 10–15 μm |

| Metulae | Two to six, 6–10 × 1.5–2.5 µm | Two to five, divergent, 7–11 × 2–2.5 μm |

| Phialides | Acerose, three to eight per metula, 5.5–10 × 1.5–2 µm | Acerose, two to six per metula, 7.5–11.5 × 1.5–3 μm |

| Conidia | Globose, 1.5–2.0 µm, smooth-walled | Ellipsoidal, 2.5–4 × 1.5–2.5 μm, smooth |

| Ascomata | Absent | Absent |

a From the description by Yilmaz et al. [3].

Etymology: Referring to the name of the site where freshwater sample was obtained.

Type specimen: REPUBLIC OF KOREA, Jeonnam Province, Wonhyo Valley located at Mudeung Mt., Gwangju (35°9′1.18″ N, 126°59′24.62″ E) from a freshwater sample, 3 January 2017, H.B. Lee (holotype CNUFC HT19191; ex-type culture CNUFC WT19-1).

Colony diam, 7 d (mm): CYA 25 °C < 1 mm, CYA 20 °C no growth; CYA 30 °C no growth; CYA 37 °C no growth; MEA 25 °C 13–15; YES 25 °C 3–5; OA 25 °C 6–7; CREA 25 °C no growth; CYAS 25 °C no growth; DG18 25 °C 2–4.

Colony characters: CYA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies low, plane; margins low, entire (<1 mm); mycelia white; sporulation absent; soluble pigments absent; exudates absent; reverse white. MEA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies strong raised at the center; sporulating central area is dull green, yellow towards the edge; exudate absent; soluble pigments absent; reverse brown-orange center, light yellow near margin. YES 25 °C, 7 d: Sporulation absent, mycelium white; exudate absent; soluble pigments absent; reverse white. OA 25 °C, 7 d: Colony surface velutinous; dull green when sporulating; reverse white; soluble pigments absent; exudates absent. CREA 25 °C, 7 d: No growth. DG18 25 °C, 7 d: No sporulation, mycelium white.

Micromorphology: Sclerotia absent. Conidiophores 39–174 × 1.5–3 µm, biverticillate and monoverticillate. Metulae 2–6, 6–10 × 1.5–2.5 µm. Phialides acerose-shaped, 3–8 per metula, 5.5–10 × 1.5–2 µm. Conidia globose, 1.5–2.0 µm, smooth-walled, conidial chains. Ascomata not observed.

Extrolites: T. gwangjuensis (the ex-type strain) produced austin, austinol (and other austins), mitorubrin, mitorubrinol, mitorubrinol acetate, mitorubrinic acid, and a purpactin.

Notes: Talaromyces gwangjuensis nested together with T. rademirici. However, T. gwangjuensis differs morphologically from T. rademirici, as it forms smaller colonies on Czapek yeast autolysate agar and yeast extract sucrose agar at 25 °C, and the number of phialides per metula and metulae are larger than those of T. rademirici. Furthermore, T. gwangjuensis produces globose conidia in contrast with the ellipsoid conidia of T. rademirici. Talaromyces rademirici grew at 37 °C, whereas T. gwangjuensis did not.

Additional material examined: REPUBLIC OF KOREA, Jeonnam Province, Wonhyo Valley located at Mudeung Mt., Gwangju (35°9′1.18″ N, 126°59′24.62″ E) from a freshwater sample, 4 January 2017, H.B. Lee (culture CNUFC WT19-2).

Talaromyces koreana Hyang B. Lee sp. nov.

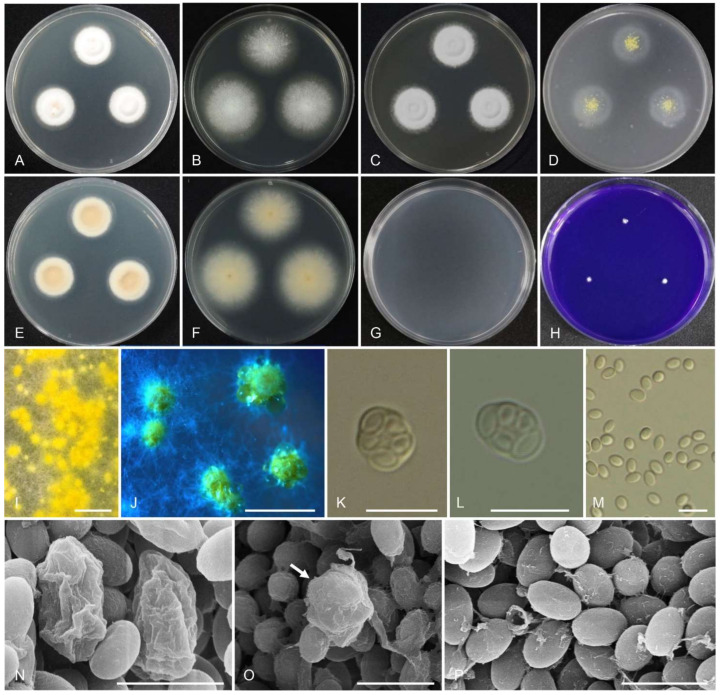

Index Fungorum: IF554802 (Figure 5 and Table 3).

Figure 5.

Morphology of Talaromyces koreana CNUFC YJW2-13. (A,E) Colonies on Czapek yeast autolysate agar (CYA). (B,F) Malt extract agar (MEA). (C) Yeast extract sucrose agar (YES). (D) Oatmeal agar (OA). (G) Dichloran 18% glycerol agar (DG18). (H) Creatine sucrose agar (CREA). ((A–D,G,H) Obverse view and (E,F) reverse view). (I–L,N–Q) Conidiophores. (M,R) Conidia. ((I–M) LM and (N–R) SEM). Scale bars: (I) = 100 µm, (J–L) = 20 µm, (M,Q) = 10 µm, (N–P) = 25 µm, and (R) = 2 µm.

Table 3.

Morphological characteristics of Talaromyces koreana CNUFC YJW2-13 compared with those of the reference strains Talaromyces boninensis and Talaromyces reverso-olivaceus.

| Characteristics | CNUFC YJW2-13 Isolated in This Study | Talaromyces boninensis a | Talaromyces reverso-olivaceus b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size after 7 days at 25 °C (diameter) | 25–28 mm on CYA | 28 mm on CYA | 19–23 mm on CYA |

| 21–24 mm on YES | NI | 25–26 mm on YES | |

| 41–45 mm on MEA | 30 mm on MEA | 34–37 mm on MEA | |

| 36–39 mm on OA | 32 mm on OA | 33–36 mm on OA | |

| 15–18 mm CREA | NI | No growth on CREA | |

| Size after 7 days at 37 °C | 17–19 mm on CYA | NI | 18–20 mm on CYA |

| Conidiophores | Biverticillate, sometimes with additional branches, stipes smooth, 15–194 × 2–4 μm, branches 6–17 × 2–3 μm | Biverticillate; stipes finely rough, 25–260 × 2.5–4 μm | Biverticillate, sometimes with extra subterminal branches; stipes smooth, 50–100 × 2.5–4 μm, branches 12–15 × 2–3 μm |

| Metulae | Two to seven, 7.5–16 × 2–3 μm | Four to ten, 10–16(–20) × 2.5–3(–3.5) μm | Three to five, 10–13 × 3–4 μm |

| Phialides | Acerose, two to seven per metula, 5.5–15 × 2–3 μm | Acerose, two to six per metula, 10–15 × 2–3.5 μm | Acerose, three to five per metula, 10–12(–14) × 2.5–3 μm |

| Conidia | Ellipsoidal to fusiform, finely roughed, 2–3.5 × 1.5–2.5 μm | Ellipsoidal to fusiform, sometimes globose, smooth, 2–4 × 1.5–2.5 μm | Ellipsoidal to fusiform, finely roughed, 2.5–4.5 × 2.5–3 μm |

| Ascomata | Absent | Grayish green, globose to subglobose, 280–550 × 240–480 μm | Absent |

Etymology: Referring to the country from which the species was first isolated (Korea).

Type specimen: REPUBLIC OF KOREA, Jeonnam Province, Jukrim reservoir located in Yeosu (34°45′37.72″ N, 127°37′43.46″ E) from a freshwater sample, 26 May 2017, H.B. Lee (CNUFC HT19213 holotype; ex-type culture CNUFC YJW2-13).

Colony diam, 7 d (mm): CYA 25 °C 25–28, CYA 20 °C 15–16, CYA 30 °C 28–31; CYA 37 °C 17–19; MEA 25 °C 41–45; YES 25 °C 21–24; OA 25 °C 36–39; CREA 25 °C 15–18; CYAS 25 °C no growth; DG18 25 °C no growth.

Colony characters: CYA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies sulcate, raised at the center; margins entire, mycelia slightly murky white; texture floccose; reverse greyish green at the center fading into ivory. MEA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies low, plane; mycelia white; reverse beige. YES 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies irregularly deep sulcate, raised at the center; margins low, plane, entire (2.5–3 mm); mycelia white; texture floccose; reverse deep olive green. OA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies low, plane; margins plane, entire (2.5–3 mm); mycelia white; texture velvety; reverse ivory to white. CREA 25 °C, 7 d: Acid production.

Micromorphology: Sclerotia absent. Conidiophores biverticillate, sometimes with additional branches; stipes smooth, 15–194 × 2–4 μm, branches 6–17 × 2–3 μm. Metulae acerose, two to seven, 7.5–16 × 2–3 μm. Phialides acerose, two to seven per metula, 5.5–15 × 2–3 μm. Conidia ellipsoidal to fusiform, finely roughed, 2–3.5 × 1.5–2.5 μm. Ascomata not observed.

Extrolites: Cycloleucomelone, gregatin A, and purpactin A were detected in the ex-type strain of T. koreana.

Notes: Talaromyces koreana belongs to section Helici and is phylogenetically related to T. boninensis and T. reverso-olivaceus. Talaromyces koreana differs from T. boninensis and T. reverso-olivaceus by having a higher number of phialides per metula. Talaromyces koreana produces smaller conidia than those of T. boninensis and T. reverso-olivaceus. The maximum colony diameter reported for the species of T. boninensis and T. reverso-olivaceus are 30 and 34–37 mm when cultivated on MEA at 25 °C in 7 days, while T. koreana is 41–45 mm.

Material examined: REPUBLIC OF KOREA, Jeonnam Province, Jukrim reservoir located in Yeosu (34°45′37.72″ N, 127°37′43.46″ E) from a freshwater sample, 27 May 2017, H.B. Lee (culture CNUFC YJW2-14).

Talaromyces teleomorpha Hyang B. Lee, Frisvad, P.M. Kirk, H.J. Lim & T.T.T. Nguyen sp. nov.

Index Fungorum: IF554803 (Figure 6 and Table 4).

Figure 6.

Morphology of Talaromyces teleomorpha CNUFC YJW2-5. (A,E) Colonies on Czapek yeast autolysate agar (CYA). (B,F) Malt extract agar (MEA). (C) Yeast extract sucrose agar (YES). (D) Oatmeal agar (OA). (G) Dichloran 18% glycerol agar (DG18). (H) Creatine sucrose agar (CREA). ((A–D,G,H) Obverse view and (E,F) reverse view). (I,J) Ascomata. (K–P) Asci and ascospores. ((I,J) Stereomicroscope, (K–M) LM and (N–P) SEM). Scale bars: (I,J) = 1 mm, (K–M) = 10 µm, and (N–P) = 5 µm.

Table 4.

Morphological characteristics of Talaromyces teleomorpha CNUFC YJW2-5 compared with those of the reference strain Talaromyces helicus.

| Characteristics | CNUFC YJW2-5 Isolated in This Study | Talaromyces helicus a |

|---|---|---|

| Size after 7 days at 25 °C (diameter) | 26–29 mm on CYA | 13–23 mm on CYA |

| 29–33 mm on YES | 14–22 mm on YES | |

| 45–48 mm on MEA | 25–33 mm on MEA | |

| 32–34 mm on OA | 23–35 mm on OA | |

| 1–3 on CREA | No growth on CREA | |

| Size after 7 days at 37 °C (diameter) | 15–20 mm on CYA | 10–18 mm on CYA |

| Conidiophores | Not observed | Mono- to biverticillate, stipes smooth walled, 30–60(–80) × 2–2.5 μm |

| Metulae | Not observed | Two to five, 12–15 × 2–2.5 μm |

| Phialides | Not observed | Acerose, two to four per metula, 8.5–12(–16) × 2.5–3 μm |

| Conidia | Not observed | Globose to subglobose, smooth, 2.5–3.5(–4.5) × 2.2–3.5 μm |

| Ascomata | Creamish-white to yellow to reddish, globose to subglobose, 200–800 μm | Yellow, pastel yellow and creamish-white, globose to subglobose, 100–300 μm |

| Asci | Ellipsoidal, globose to subglobose, (5.5–)6.5–9 × (4.5–)6–7 μm | 6–9 × 4.5–6 μm |

| Ascospores | Ellipsoidal, smooth, 3–4 × 2–3 μm | Ellipsoidal, smooth (some with minute spines), 2.5–4 × 2–3 μm |

a From the description by Yilmaz et al. [3].

Etymology: Referring to the teleomorphic stage.

Type specimen: REPUBLIC OF KOREA, Jeonnam Province, Jukrim reservoir located in Yeosu (34°45′37.72″ N, 127°37′43.46″ E) from a freshwater sample, 26 May 2017, H.B. Lee (CNUFC HT19251 holotype; ex-type culture: CNUFC YJW2-5).

Colony diam, 7 d (mm): CYA 25 °C 26–29; CYA 20 °C 15–16; CYA 30 °C 34–36; CYA 37 °C 15–20; MEA 25 °C 45–48; YES 25 °C 29–33; OA 25 °C 32–34; CREA 25 °C 1–3; CYAS 25 °C no growth; DG18 25 °C no growth.

Colony characters: CYA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies raised at the center, slightly sulcate; margins low, plane, entire (3 mm); mycelia white to light yellow; reverse ivory to light yellow, slightly sunken at the center. MEA 25 °C, 7 d: colonies low, plane; mycelia white to light yellow, hyaline; reverse light orange at the center. YES 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies raised at the center, sulcate; margins low; mycelia white; reverse pale orange. OA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies low, plane; mycelia white to light yellow, hyaline, smooth or rough, studded. CREA 25 °C, 7 d: Acid production absent.

Micromorphology: Ascomata maturing within 1 week on OA and MEA at 20–35 °C, abundant, creamish-white to yellow to reddish after long time, usually globose to subglobose, 200–800 μm. Asci ellipsoidal, globose to subglobose, (5.5–)6.5–9 × (4.5–)6–7 μm. Ascospores ellipsoidal, smooth, 3–4 × 2–3 μm.

Notes: Talaromyces teleomorpha can be distinguished easily from the closely related species T. helicus by growing rapidly on CYA, YES, and MEA at 25 °C in 7 days. Ascomata size of T. helicus are smaller than in T. teleomorpha. Talaromyces helicus does not grow on CREA, whereas T. teleomorpha can grow on this medium. In addition, T. teleomorpha does not produce the asexual morph, which is present in T. helicus.

Extrolites: Talaromyces teleomorpha produced helicusins formerly found in Talaromyces helicus.

Material examined: REPUBLIC OF KOREA, Jeonnam Province, Jukrim reservoir located in Yeosu (34°45′37.72″ N, 127°37′43.46″ E) from a freshwater sample, 27 May 2017, H.B. Lee (Culture CNUFC YJW2-6).

4. Discussion

During a survey of fungi from a freshwater niche in Korea, three novel species were identified, namely Talaromyces gwangjuensis, T. koreana, and T. teleomorpha.

In our phylogenetic analysis, Talaromyces gwangjuensis was classified in section Purpurei. This species is closely related to T. rademirici, which also has both monoverticillate and biverticillate conidiophores and do not grow on CREA. However, Talaromyces gwangjuensis has more restricted colonies on YES and CYA and larger numbers of metulae and phialides. Growth on CYA at 37 °C and the conidial shape and size on MEA at 25 °C can be easily used to distinguish between T. gwangjuensis and T. rademirici. Talaromyces rademirici grows faster on CYA at all temperatures (CYA at 25 °C, 5–6; CYA at 30 °C, 5–7; CYA at 37 °C, 3), whereas Talaromyces gwangjuensis was unable to grow on CYA at 37 °C. Some species in this section have been reported to not grow on CYA at 37 °C, including T. pittii and T. purpureus [3]; however, T. pittii and T. purpureus produce ellipsoidal and subglobose to ellipsoidal conidia compared with T. gwangjuensis that produces globose conidia.

Talaromyces koreana and T. teleomorpha belong to the section Helici, which was established by Yilmaz et al. [3]. The species in the section was not found to produce acid on CREA medium [3]. However, recent studies showed that T. georgiensis and T. borbonicus could produce acid on the medium [12,20]. In the present study, T. koreana was also found to produce acid on the medium. The results suggest that the ability to produce acid on CREA may not usually a key character to distinguish this section. It is a common character for the species in the section Helici to be able to grow at 37 °C [3]. Our results are the same as previous studies [3]. Interestingly, we found that T. koreana could grow at 40 °C on MEA media (10–13 mm after 7 days), while not on other media. Our findings showed that the medium composition might influence the maximum growth of fungi.

Talaromyces teleomorpha is closely related to T. helicus. However, T. helicus produces both asexual and sexual morphs, whereas the asexual morph is not observed in T. teleomorpha [3]. Especially, T. teleomorpha can grow on CREA, while T. helicus is unable to grow on this medium [3].

Although ITS is the barcoding marker for fungi [66], this locus is not sufficient to differentiate all Talaromyces species. Yilmaz et al. [3] proposed using BenA as a secondary molecular marker. In this study, T. gwangjuensis, T. koreana, and T. teleomorpha could be separated via each single gene phylogram. Recently, T. brunneosporus was described as a new species discovered from honey in Spain [24]. It was assigned to section Purpurei using the ITS, BenA, CaM, and RPB2 concatenated dataset. The comparison of ITS, BenA, CaM, and RPB2 sequences deposited in GenBank indicated that this species could not be assigned to any known section based on our phylogenetic analyses (Figure 1). In each single gene phylogeny (ITS, BenA, CaM, and RPB2), T. brunneosporus also formed a separate lineage (data not shown). More strains are essential to confirm the taxonomic position of T. brunneosporus.

Some members from the genus Talaromyces are of great interest to the biotechnology industry in medial and food mycology because of their ability to produce a wide range of metabolites [3]. The species of section Purpurei produce various extrolite profiles. For example, T. cecidicola produces apiculides, pentacecilides, and thailandolides. Talaromyces coalescens, T. dendriticus, and T. purpurogenus share productions of penicillides, purpactins, and vermixocins. On the other hand, T. purpurogenus and T. pseudostromaticus produce the extrolite mitorubin. Some Talaromyces species produce mycotoxins such as botryodiplodin by T. coalescens, rugulovasine and luteoskyrin by T. purpurogenus, rubratoxins by T. purpurogenus and T. dendriticus, and secalonic acids D and F by T. pseudostromaticus. Talaromyces gwangjuensis, described in this study, produces austin, austinol, mitorubrin, mitorubrinol, mitorubrinol acetate, mitorubrinic acid, and a purpactin without any production of mycotoxins. Some secondary metabolites were found in the section Helici, such as alternariol, bacillisporin, and helicusins produced by T. helicus [3,67]. Talaromyces reverso-olivaceus produced rugulovasine A [5], while talaroderxines is produced by T. boninensis [3]. In this study, T. koreana produced cycloleucomelone, gregatin A, and purpactin A. Talaromyces teleomorpha also produced helicusins, as described by Yoshida et al. [67].

Talaromyces species are geographically distributed in many kinds of substrates. The species of section Helici have been reported to be isolated from soil, cotton yarn, debris, clinical sources, indoor environments, and biomass of Arundo donax [3,5,12,15,20]. The species of section Purpurei have been reported to be isolated from the air, wasp insect galls, Eucalyptus, Protea repens infructescence, and other substrates such as apples [3,17,68,69,70,71]. In this study, we isolated three novel species from freshwater. As far as we know, only species belonging to section Talaromyces were reported from water [22,72,73,74]. It is interesting to note that Talaromyces gwangjuensis, T. koreana, and T. teleomorpha were the first species in the sections Purpurei and Helici isolated from freshwater. Our studies expanded our knowledge on the substrates where Talaromyces species can occur. Further studies are needed for a better understanding of the ecological roles of these species.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jof7090722/s1: Figure S1: Phylogram generated from the Maximum Likelihood (RAxML) analysis based on the BenA sequence data for species classified in Talaromyces section Purpurei. The branches with values = 100% ML BS and 1 PP are highlighted by thickened branches. The branches with values ≥ 70% ML BS and ≥ 0.95 PP indicated above or below branches. Talaromyces tenuis CBS 141840 was used as the outgroup. The newly generated sequences are indicated in blue. T = ex-type. Figure S2: Phylogram generated from the Maximum Likelihood (RAxML) analysis based on the RPB2 sequence data for species classified in Talaromyces section Purpurei. The branches with values = 100% ML BS and 1 PP are highlighted by thickened branches. The branches with values ≥ 70% ML BS and ≥ 0.95 PP indicated above or below branches. Talaromyces tenuis CBS 141840 was used as the outgroup. The newly generated sequences are indicated in blue. T = ex-type. Figure S3: Phylogram generated from the Maximum Likelihood (RAxML) analysis based on the ITS sequence data for species classified in Talaromyces section Purpurei. The branches with values = 100% ML BS and 1 PP are highlighted by thickened branches. The branches with values ≥ 70% ML BS and ≥ 0.95 PP indicated above or below branches. Talaromyces tenuis CBS 141840 was used as the outgroup. The newly generated sequences are indicated in blue. T = ex-type. Figure S4: Phylogram generated from the Maximum Likelihood (RAxML) analysis based on the BenA sequences data for species classified in Talaromyces section Helici. The branches with values = 100% ML BS and 1 PP are highlighted by thickened branches. The branches with values ≥ 70% ML BS and ≥ 0.95 PP indicated above or below branches. Talaromyces tenuis CBS 141840 was used as the outgroup. The newly generated sequences are indicated in blue. T = ex-type. Figure S5: Phylogram generated from the Maximum Likelihood (RAxML) analysis based on the ITS sequences data for species classified in Talaromyces section Helici. The branches with values = 100% ML BS and 1 PP are highlighted by thickened branches. The branches with values ≥ 70% ML BS and ≥ 0.95 PP indicated above or below branches. Talaromyces tenuis CBS 141840 was used as the outgroup. The newly generated sequences are indicated in blue. T = ex-type. Figure S6: Phylogram generated from the Maximum Likelihood (RAxML) analysis based on the CaM sequence data for species classified in Talaromyces section Helici. The branches with values = 100% ML BS and 1 PP are highlighted by thickened branches. The branches with values ≥ 70% ML BS and ≥ 0.95 PP indicated above or below branches. Talaromyces tenuis CBS 141840 was used as the outgroup. The newly generated sequences are indicated in blue. T = ex-type. Figure S7: Phylogram generated from the Maximum Likelihood (RAxML) analysis based on the RPB2 sequence data for species classified in Talaromyces section Helici. The branches with values = 100% ML BS and 1 PP are highlighted by thickened branches. The branches with values ≥ 70% ML BS and ≥ 0.95 PP indicated above or below branches. Talaromyces tenuis CBS 141840 was used as the outgroup. The newly generated sequences are indicated in blue. T = ex-type.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: H.B.L. and T.T.T.N.; Methodology: T.T.T.N., J.C.F. and H.B.L.; Software: T.T.T.N.; Validation: H.B.L.; Formal Analysis: T.T.T.N., J.C.F. and H.B.L.; Investigation: T.T.T.N. and H.B.L.; Resources: H.B.L.; Writing—Original Draft: T.T.T.N. and H.B.L.; Writing—Review and Editing: T.T.T.N., J.C.F., P.M.K., H.J.L. and H.B.L.; Supervision: H.B.L.; Funding Acquisition: H.B.L.; and Project Administration: H.B.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was in part financially supported by Chonnam National University (grant number: 2017-2827). This work was supported by the project on Discovery of Fungi from Freshwater funded by NNIBR of the Ministry of Environment (MOE), Korea.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All sequences generated in this study were submitted to GenBank.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Benjamin C.R. Ascocarps of Aspergillus and Penicillium. Mycologia. 1995;47:669–687. doi: 10.1080/00275514.1955.12024485. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Samson R.A., Yilmaz N., Houbraken J., Spierenburg H., Seifert K.A., Peterson S.W., Varga J., Frisvad J.C. Phylogeny and nomenclature of the genus Talaromyces and taxa accommodated in Penicillium subgenus Biverticillium. Stud. Mycol. 2011;70:159–184. doi: 10.3114/sim.2011.70.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yilmaz N., Visagie C.M., Houbraken J., Frisvad J.C., Samson R.A. Polyphasic taxonomy of the genus Talaromyces. Stud. Mycol. 2014;78:175–341. doi: 10.1016/j.simyco.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Visagie C.M., Yilmaz N., Frisvad J.C., Houbraken J., Seifert K.A., Samson R.A., Jacobs K. Five new Talaromyces species with ampulliform-like phialides and globose rough walled conidia resembling T. verruculosus. Mycoscience. 2015;56:486–502. doi: 10.1016/j.myc.2015.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen A.J., Sun B.D., Houbraken J., Frisvad J.C., Yilmaz N., Zhou Y.G., Samson R.A. New Talaromyces species from indoor environments in China. Stud. Mycol. 2016;84:119–144. doi: 10.1016/j.simyco.2016.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luo Y., Lu X., Bi W., Liu F., Gao W. Talaromyces rubrifaciens, a new species discovered from heating, ventilation and air conditioning systems in China. Mycologia. 2016;108:773–779. doi: 10.3852/15-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Romero S.M., Romero A.I., Barrera V., Comerio R. Talaromyces systylus, a new synnematous species from Argentinean semiarid soil. Nova Hedwigia. 2016;102:241–256. doi: 10.1127/nova_hedwigia/2015/0306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang X.C., Chen K., Xia Y.W., Wang L., Li T., Zhuang W.Y. A new species of Talaromyces (Trichocomaceae) from the Xisha Islands, Hainan, China. Phytotaxa. 2016;267:187–200. doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.267.3.2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yilmaz N., López-Quintero C.A., Vasco-Palacios A.M., Frisvad J.C., Theelen B., Boekhout T., Samson R.A., Houbraken J. Four novel Talaromyces species isolated from leaf litter from Colombian Amazon rain forests. Mycol. Prog. 2016;15:1041–1056. doi: 10.1007/s11557-016-1227-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yilmaz N., Visagie C.M., Frisvad J.C., Houbraken J., Jacobs K., Samson R.A. Taxonomic re-evaluation of species in Talaromyces section Islandici, using a polyphasic approach. Persoonia. 2016;36:37–56. doi: 10.3767/003158516X688270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crous P.W., Wingfield M.J., Burgess T.I., Carnegie A.J., Hardy G.S., Smith D., Summerell B.A., Cano-Lira J.F., Guarro J., Houbraken J., et al. Fungal Planet description sheets 625–715. Persoonia. 2017;39:460–461. doi: 10.3767/persoonia.2017.39.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guevara-Suarez M., Sutton D.A., Gené J., García D., Wiederhold N., Guarro J., Cano-Lira J.F. Four new species of Talaromyces from clinical sources. Mycoses. 2017;60:651–662. doi: 10.1111/myc.12640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peterson S.W., Jurjević Ž. New species of Talaromyces isolated from maize, indoor air, and other substrates. Mycologia. 2017;109:537–556. doi: 10.1080/00275514.2017.1369339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang X.C., Chen K., Qin W.T., Zhuang W.Y. Talaromyces heiheensis and T.mangshanicus, two new species from China. Mycol. Prog. 2017;16:73–81. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barbosa R.N., Bezerra J.D., Souza-Motta C.M., Frisvad J.C., Samson R.A., Oliveira N.T., Houbraken J. New Penicillium and Talaromyces species from honey, pollen and nests of stingless bees. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 2018;13:1883–1912. doi: 10.1007/s10482-018-1081-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crous P.W., Wingfield M.J., Burgess T.I., Hardy G.S., Gené J., Guarro J., Baseia I.G., García D., Gusmão L.F., Souza-Motta C.M., et al. Fungal Planet description sheets: 716–784. Persoonia. 2018;40:239–392. doi: 10.3767/persoonia.2018.40.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crous P.W., Luangsa-Ard J.J., Wingfield M.J., Carnegie A.J., Hernández-Restrepo M., Lombard L., Roux J., Barreto R.W., Baseia I.G., Cano-Lira J.F., et al. Fungal Planet description sheets: 785–867. Persoonia. 2018;41:238–417. doi: 10.3767/persoonia.2018.41.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang X.Z., Yu Z.D., Ruan Y.M., Wang L. Three new species of Talaromyces sect. Talaromyces discovered from soil in China. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:4932. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-23370-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Su L., Niu Y.C. Multilocus phylogenetic analysis of Talaromyces species isolated from curcurbit plants in China and description of two new species, T. curcurbitiradicus and T. endophyticus. Mycologia. 2018;110:375–386. doi: 10.1080/00275514.2018.1432221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Varriale S., Houbraken J., Granchi Z., Pepe O., Cerullo G., Ventorino V., Chin-A-Woeng T., Meijer M., Riley R., Grigoriev I.V., et al. Talaromyces borbonicus sp. nov., a novel fungus from biodegraded Arundo donax with potential abilities in lignocellulose conversion. Mycologia. 2018;110:316–324. doi: 10.1080/00275514.2018.1456835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rajeshkumar K.C., Yilmaz N., Marathe S.D., Seifert K.A. Morphology and multigene phylogeny of Talaromyces amyrossmaniae, a new synnematous species belonging to the section Trachyspermi from India. Mycokeys. 2019;45:41–56. doi: 10.3897/mycokeys.45.32549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peterson S.W., Jurjevic Z. The Talaromyces pinophilus species complex. Fungal Biol. 2019;123:745–762. doi: 10.1016/j.funbio.2019.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doilom M., Guo J.W., Phookamsak R., Mortimer P.E., Karunarathna S.C., Dong W., Liao C.F., Yan K., Pem D., Suwannarach N., et al. Screening of phosphate-solubilizing fungi from air and soil in Yunnan, China: Four novel species in Aspergillus, Gongronella, Penicillium, and Talaromyces. Front. Microbiol. 2020;11:585215. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.585215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodríguez-Andrade E., Stchigel A.M., Terrab A., Guarro J., Cano-Lira J.F. Diversity of xerotolerant and xerophilic fungi in honey. IMA Fungus. 2019;10:20. doi: 10.1186/s43008-019-0021-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crous P.W., Cowan D.A., Maggs-Kölling G., Yilmaz N., Larsson E., Angelini C., Brandrud T.E., Dearnaley J.D., Dima B., Dovana F., et al. Fungal Planet description sheets: 1112–1181. Persoonia. 2020;45:251–409. doi: 10.3767/persoonia.2020.45.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun B.D., Chen A.J., Houbraken J., Frisvad J.C., Wu W.P., Wei H.L., Zhou Y.G., Jiang X.Z., Samson R.A. New section and species in Talaromyces. Mycokeys. 2020;68:75–113. doi: 10.3897/mycokeys.68.52092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Houbraken J., Kocsubé S., Visagie C.M., Yilmaz N., Wang X.C., Meijer M., Kraak B., Hubka V., Bensch K., Samson R.A., et al. Classification of Aspergillus, Penicillium, Talaromyces and related genera (Eurotiales): An overview of families, genera, subgenera, sections, series and species. Stud. Mycol. 2020;95:5–169. doi: 10.1016/j.simyco.2020.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sang H., An T., Kim C.S., Shin G., Sung G., Yu S.H. Two novel Talaromyces species isolated from medicinal crops in Korea. J. Microbiol. 2013;51:704–708. doi: 10.1007/s12275-013-3361-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.You Y.H., Aktaruzzaman M., Heo I., Park J.M., Hong J.W., Hong S.B. Talaromyces halophytorum sp. nov. isolated from roots of Limonium tetragonum in Korea. Mycobiology. 2020;48:133–138. doi: 10.1080/12298093.2020.1723389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reyes I., Bernier L., Simard R.R. Characteristics of phosphate solubilization by an isolate of a tropical Penicillium rugulosum and two UV-induced mutants. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 1999;28:291–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.1999.tb00584.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Narikawa T., Shinoyama H., Fujii T. A β-rutinosidase from Penicillum rugulosum IFO 7242 that is a peculiar flavonoid glycosidase. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2000;64:1317–1319. doi: 10.1271/bbb.64.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pol D., Laxman R.S., Rao M. Purification and biochemical characterization of endoglucanase from Penicillium pinophilum MS 20. Indian J. Biochem. Biophys. 2012;49:189–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maeda R.N., Barcelos C.A., Anna L.M.M.S. Cellulase production by Penicillium funiculosum and its application in the hydrolysis of sugar cane bagasse for second generation ethanol production by fed batch operation. J. Biotechnol. 2013;163:38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2012.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yilmaz N., Houbraken J., Hoekstra E.S., Frisvad J.C., Visagie C.M., Samson R.A. Delimitation and characterisation of Talaromyces purpurogenus and related species. Persoonia. 2012;29:39–54. doi: 10.3767/003158512X659500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frisvad J.C., Yilmaz N., Thrane U., Rasmussen K.B., Houbraken J., Samson R.A. Talaromyces atroroseus, a new species efficiently producing industrially relevant red pigments. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e84102. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kakvan N., Heydari A., Zamanizadeh H.R., Rezaee S., Naraghi L. Development of new bioformulations using Trichoderma and Talaromyces fungal antagonists for biological control of sugar beet damping-off disease. Crop Prot. 2013;53:80–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2013.06.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marois J.J., Fravel D.R., Papavizas G.C. Ability of Talaromyces flavus to occupy the rhizosphere. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1984;16:387–390. doi: 10.1016/0038-0717(84)90038-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fravel D.R., Davis J.R., Sorenson L.H. Effect of Talaromyces flavus and metham on verticillium wilt incidence and potato yield 1984–1985. Biol. Cult. Tests. 1986;1:17. [Google Scholar]

- 39.McLaren D.L., Huang H.C., Kozub G.C., Rimmer S.R. Biological control of sclerotinia wilt of sunflower with Talaromyces flavus and Coniothyrium minitans. Plant Dis. 1994;78:231–235. doi: 10.1094/PD-78-0231. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Naraghi L., Heydari A., Rezaee S., Razavi M., Jahanifar H. Study on antagonistic effects of Talaromyces flavus on Verticillium albo-atrum, the causal agent of potato wilt disease. Crop Prot. 2010;29:658–662. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2010.01.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pretsch A., Nag M., Schwendinger K., Kreiseder B., Wiederstein M., Pretsch D., Genov M., Hollaus R., Zinssmeister D., Debbab A., et al. Antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory activities of endophytic fungi Talaromyces wortmannii extracts against acne-inducing bacteria. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e97929. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Deng Z.L., Ribas J.L., Gibson D.W., Connor D.H. Infections caused by Penicillium marneffei in China and Southeast Asia. Review of eighteen cases and report of four more Chinese cases. Rev. Infec. Dis. 1988;10:640–652. doi: 10.1093/clinids/10.3.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hien T.V., Loc P.P., Hoa N.T.T. First case of disseminated Penicilliosis marneffei infection among patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in Vietnam. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2001;32:78–80. doi: 10.1086/318703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stolk A.C., Samson R.A. Studies on Talaromyces and related genera II. The genus Talaromyces. Stud. Mycol. 1972;2:1221. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goh T.K., Hyde K.D. Biodiversity of freshwater fungi. J. Ind. Microbiol. 1996;17:328–345. doi: 10.1007/BF01574764. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hawksworth D.L. The fungal dimension of biodiversity: Magnitude, significance, and conservation. Mycol. Res. 1991;95:641–655. doi: 10.1016/S0953-7562(09)80810-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hawksworth D.L., Lücking R. Fungal diversity revisited 2.2 to 3.8 million species. Microbiol Spectr. 2017;5:FUNK-0052-2016. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.FUNK-0052-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shearer C.A., Descals E., Kohlmeyer B., Kohlmeyer J., Marvanová L., Padgett D., Porter D., Raja H.A., Schmit J.P., Thorton H.A., et al. Fungal biodiversity in aquatic habitats. Biodivers. Conserv. 2017;16:49–67. doi: 10.1007/s10531-006-9120-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jones E.B.G., Hyde K.D., Pang K.L. Freshwater Fungi and Fungal-Like Organisms. De Gruyter; Boston, MA, USA: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nguyen T.T.T., Paul N.C., Lee H.B. Characterization of Paecilomyces variotii and Talaromyces amestolkiae in Korea based on the morphological characteristics and multigene phylogenetic analyses. Mycobiology. 2016;44:248–259. doi: 10.5941/MYCO.2016.44.4.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.White T.J., Bruns T., Lee S., Taylor J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: Innis M.A., Gelfand D.H., Sninsky J.J., White T.J., editors. PCR Protocols. Academic Press; Cambridge, MA, USA: 1990. pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Glass N.L., Donaldson G.C. Development of primer sets designed for use with the PCR to amplify conserved genes from filamentous ascomycetes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995;6:1323–1330. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.4.1323-1330.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peterson S.W., Vega F., Posada F., Nagai C. Penicillium coffeae, a new endophytic species isolated from a coffee plant and its phylogenetic relationship to P. fellutanum, P. thiersii and P. brocae based on parsimony analysis of multilocus DNA sequences. Mycologia. 2005;97:659–666. doi: 10.1080/15572536.2006.11832796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hong S.B., Cho H.S., Shin H.D., Frisvad J.C., Samson R.A. Novel Neosartorya species isolated from soil in Korea. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2006;56:477–486. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63980-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu Y.J., Whelen S., Hall B.D. Phylogenetic relationships among ascomycetes: Evidence from an RNA polymerase II subunit. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1999;16:1799–1808. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Houbraken J., Samson R.A. Phylogeny of Penicillium and the segregation of Trichocomaceae into three families. Stud. Mycol. 2011;70:1–51. doi: 10.3114/sim.2011.70.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Katoh K., Rozewicki J., Yamada K.D. MAFFT online service: Multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Brief. Bioinform. 2019;20:1160–1166. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbx108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Capella-Gutiérrez S., Silla-Martínez J.M., Gabaldón T. TrimAl: A tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1972–1973. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kumar S., Stecher G., Tamura K. MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Glez-Peña D., Gómez-Blanco D., Reboiro-Jato M., Fdez-Riverola F., Posada D. ALTER: Program–oriented format conversion of DNA and protein alignments. Nucleic Acids. Res. 2010;38:14–18. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ronquist F., Teslenko M., van der Mark P., Ayres D.L., Darling A., Höhna S., Larget B., Liu L., Suchard M.A., Huelsenbeck J.P. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 2012;61:539–542. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rambaut A. FigTree, Version 1.3. 1. Computer Program Distributed by the Author. 2009. [(accessed on 4 January 2011)]. Available online: http://www.treebioedacuk/software/fgtree.

- 63.Frisvad J.C., Thrane U. Standardized high performance liquid chromatography of 182 mycotoxins and other fungal metabolites based on alkylphenone indices and UV VIS spectra (diode array detection) J. Chromatogr. 1987;404:195–214. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9673(01)86850-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nielsen K.F., Månsson M., Rank C., Frisvad J.C., Larsen T.O. Dereplication of microbial natural products by LC-DAD-TOFMS. J. Nat. Prod. 2011;74:2338–2348. doi: 10.1021/np200254t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Houbraken J., Wang L., Lee H.B., Frisvad J.C. New sections in Penicillium containing novel species producing patulin, pyripyropens or other bioactive compounds. Persoonia. 2016;36:299–314. doi: 10.3767/003158516X692040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schoch C.L., Seifert K.A., Huhndorf S., Robert V., Spouge J.L., Levesque C.A., Chen W., Bolchacova E., Voigt K., Crous P.W., et al. Nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region as a universal DNA barcode marker for Fungi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:6241–6246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117018109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yoshida E., Fujimoto H., Baba M., Yamazaki M. 4 new chlorinated azaphilones, helicusins A-D, closely related to 7-epi-sclerotiorin, from an ascomycetous fungus, Talaromcyes helicus. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1995;43:1307–1310. doi: 10.1248/cpb.43.1307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Seifert K.A., Hoekstra E.S., Frisvad J.C., Louis-Seize G. Penicillium cecidicola, a new species on cynipid insect galls on Quercus pacifica in the western United States. Stud. Mycol. 2004;50:517–523. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Visagie C.M., Roets F., Jacobs K. A new species of Penicillium, P. ramulosum sp. nov., from the natural environment. Mycologia. 2009;101:888–895. doi: 10.3852/08-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Van der Walt L., Spotts R.A., Visagie C.M., Jacobs K., Smit F.J., McLeod A. Penicillium species associated with preharvest wet core rot in South Africa and their pathogenicity on apple. Plant Dis. 2010;94:666–675. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-94-6-0666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Visagie C.M., Jacobs K. Three new additions to the genus Talaromyces isolated from Atlantis sandveld fynbos soils. Persoonia. 2012;28:14–24. doi: 10.3767/003158512X632455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Heo I., Hong K., Yang H., Lee H.B., Choi Y.-J., Hong S.-B. Diversity of Aspergillus, Penicillium, and Talaromyces species isolated from freshwater environments in Korea. Mycobiology. 2019;47:12–19. doi: 10.1080/12298093.2019.1572262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pangging M., Nguyen T.T.T., Lee H.B. New records of four species belonging to Eurotiales from soil and freshwater in Korea. Mycobiology. 2019;47:154–164. doi: 10.1080/12298093.2018.1554777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Visagie C.M., Houbraken J. Updating the taxonomy of Aspergillus in South Africa. Stud. Mycol. 2020;95:253–292. doi: 10.1016/j.simyco.2020.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All sequences generated in this study were submitted to GenBank.