Abstract

Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) is a conserved eukaryotic signaling factor that mediates various signals, cumulating in the activation of transcription factors. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), a MAPK, is activated through phosphorylation by the kinase MAPK/ERK kinase (MEK). To elucidate the extent of the involvement of ERK in various aspects of animal development, we searched for a Drosophila mutant which responds to elevated MEK activity and herein identified a lace mutant. Mutants with mild lace alleles grow to become adults with multiple aberrant morphologies in the appendages, compound eye, and bristles. These aberrations were suppressed by elevated MEK activity. Structural and transgenic analyses of the lace cDNA have revealed that the lace gene product is a membrane protein similar to the yeast protein LCB2, a subunit of serine palmitoyltransferase (SPT), which catalyzes the first step of sphingolipid biosynthesis. In fact, SPT activity in the fly expressing epitope-tagged Lace was absorbed by epitope-specific antibody. The number of dead cells in various imaginal discs of a lace hypomorph was considerably increased, thereby ectopically activating c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), another MAPK. These results account for the adult phenotypes of the lace mutant and suppression of the phenotypes by elevated MEK activity: we hypothesize that mutation of lace causes decreased de novo synthesis of sphingolipid metabolites, some of which are signaling molecules, and one or more of these changes activates JNK to elicit apoptosis. The ERK pathway may be antagonistic to the JNK pathway in the control of cell survival.

Many studies of intracellular signals that regulate cell growth, differentiation, and the stress response have focused on mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) (12, 22, 53, 71). These kinases are activated through phosphorylation by MAPK kinases (MAPKKs) and mediate various signaling inputs into transcription factors. Three subgroups of the MAPK superfamily have been identified: extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) or stress-activated protein kinase, and p38 (or Mpk2). The ERK cascade plays a central role in the transduction of mitogenic signals. JNK and p38 are activated in response to a variety of stresses and inflammatory cytokines and are apparently distinct in function from ERK. Through these studies, many kinds of signaling cues have been shown to culminate in the activation of MAPK.

Drosophila melanogaster expresses all three subgroups of MAPKs: Rl (Rolled; ERK homolog [11, 17]), DJNK (Drosophila homolog of JNK [78, 85]), and D-p38a and D-p38b (Drosophila homologs of p38 [33, 34]). In contrast to the pleiotropic roles of mammalian MAPKs, the known functions of Drosophila MAPKs are somewhat restricted to particular developmental aspects. For example, Rl has been characterized only as a downstream factor for receptor tyrosine kinases (11, 17, 27, 28). It is also antagonistic to the apoptotic signal by repressing the apoptotic protein Hid (Head involution defective, also known as W [Wrinkled] [8, 52]). DJNK has been characterized as a mediator of cell morphogenesis and cell polarity signaling, as well as a stress-signaling transducer (14, 29–31, 45, 46, 61, 72, 78–80, 85, 88). Furthermore, it is known to transduce apoptotic signal in response to distortion of the proximodistal information in the wing disc (3). D-p38b has been reported to modulate signal transduction from a transforming growth factor β superfamily ligand, Dpp, during wing development (2). D-p38 proteins are also known to inhibit antimicrobial peptide production and to transduce stress signals (33, 34).

To elucidate the role that Rl plays in various aspects of Drosophila development, we searched for a mutant which responds to hyperactive MAPK/ERK kinase (MEK), a MAPKK specific for ERK. Dsor1 (Downstream suppressor of Raf-1) is the Drosophila homolog of MEK. Its dominant mutation, Dsor1Su1, is known to genetically interact with mutations of various upstream and downstream components (55, 58, 94). Thus, a mutant which responds to Dsor1Su1 may reflect the various functions of Rl. In this study, we analyzed one such mutant previously known as the lace mutant. Unexpectedly, apoptosis in the imaginal discs of lace mutants was caused by ectopic activation of DJNK. Hence, Rl was interpreted to function as a survival factor antagonistic to the apoptotic DJNK pathway. The lace gene encodes a homolog of the LCB2 subunit of serine palmitoyltransferase (SPT) (EC 2.3.1.50), an enzyme which catalyzes the first step in the biosynthesis of sphingolipids (63, 68). This also demonstrates sphingolipid-mediated MAPK regulation in Drosophila development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fly strains.

P-lacW is a derivative of the transposon P element of Drosophila. A P-lacW-inserted lace allele, l(2)k05305 (also known as 53/5), was originally isolated by I. Kiss (9, 87, 93). All the lace alleles and deficient strains were kindly provided by J. Roote and M. Ashburner at the Department of Genetics, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom. Df(2L)TE35D-GW1 is also known as Df(2L)TE35D-1 (49) and Df(2L)TE116(R)GW1 (6).

Plasmids.

The plasmid clone containing the full-length lace cDNA isolated from the pNB40 imaginal disc cDNA library (16) was named pNBlace. pNBlace has an inverted T7 promoter just downstream of its cloning site. A single NotI site is present between the cloning site and the inverted T7 promoter. A derivative of expression vector pCDM8 (26, 84) carries the XbaI, SalI, and NotI restriction sites in that order. The hemagglutinin (HA) tag (51) coding region is also present between the XbaI and SalI sites.

Construction of transgenic flies expressing HA-tagged Lace.

A segment of the lace cDNA was amplified from the pNBlace plasmid by PCR with the commercially available T7 primer and the synthesized primer 5′-CTTGTCGACAATGGGCAATTTCGACGGC-3′. PCR was performed with the LA PCR kit, version 2, provided by Takara (Otsu, Japan). The PCR mixture consisted of LA PCR buffer II, 400 μM (each) deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 0.2 μM (each) primer, 2.5 U of Takara LA Taq DNA polymerase, and 1 ng of pNBlace plasmid DNA as a template, in a total volume of 50 μl. The thermal profile involved 30 cycles of 20 s at 98°C and 15 min at 68°C. The resulting PCR product contained the entire lace coding region flanked on the 5′ end by SalI and on the 3′ end by the NotI unique restriction site. The PCR product digested by SalI/NotI was cloned in the above-mentioned expression vector (a derivative of pCDM8 [26]) to connect the HA tag (YPYDVPDYA) at the N-terminal end of Lace. This plasmid was cut by XbaI and treated with T4 polymerase to make a 5′ blunt end and then further cut by NotI. The resulting blunt end-XbaI/NotI fragment was cloned in the blunt end-EcoRI/NotI site of pUAST, a P-element vector containing the upstream activation sequence (UAS) (15). This construct encodes HA-tagged Lace (HAlace) driven by the UAS. There are five additional amino acid residues (SLPGS) between the N-terminal HA tag and the amino acid sequence of Lace. Additionally, two amino acid residues (MG) are present at the N-terminal end. Thus, the molecular mass of the native and HAlace proteins was calculated to be 66 and 68 kDa, respectively. Germ line transformation was carried out as previously described (5).

Assay of SPT activity.

The membrane fraction was prepared as described by Becker and Lester (7) and Mandon et al. (59). The level of enzymatic activity was determined by the procedures described by Mandon et al. (59) and Pinto et al. (76). A mixture of 0- to 3-day-old pupae (1 g) of a HAlace producer (UAS-HAlace2/actin-GAL4) was collected and homogenized in an ice-cold solution of 2.7 ml of 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 0.32 M sucrose, 5 mM EDTA, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride in a mortar for 10 min. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was ultracentrifuged at 105,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C to collect the membrane fraction. The pellet was resuspended in 2 ml of 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.4)–5 mM EDTA–1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and this was ultracentrifuged at 105,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C. The pellet was resuspended in the suspension buffer (200 μl of 50 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 5 mM EDTA, 25% glycerol, 5 mM dithiothreitol, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) and stored at −70°C until use.

Anti-HA antibody (1 μg/5 μl; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, Calif.) was added to 300 μg of protein of the above-mentioned fly membrane fraction, and this was incubated for 3 h at 4°C. Then, protein G-agarose (12.5 μg/5 μl; Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) was mixed into each solution with gentle rotation for 2 h at 4°C. The mixture was centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 5 min at 4°C, and the pellet was gently washed with 200 μl of the ice-cold suspension buffer three times.

Each reaction mixture contained the following components in a volume of 0.15 ml: 0.1 M HEPES (pH 7.4), 5 mM dithiothreitol, 10 mM EDTA, 1 mM serine, 50 μM pyridoxal phosphate, and the above pellet fraction derived from 300 μg of total membrane protein after treatment with protein G-agarose. l-[U-14C]serine (5.5 GBq/mmol; Amersham, Uppsala, Sweden) was diluted with nonradioactive serine to a final specific activity of 0.55 GBq/mmol. The reaction was initiated with the addition of palmitoyl coenzyme A (CoA) (0.15 mM). The control reaction was carried out without palmitoyl-CoA. After incubation at 30°C for 1 h, the reaction was terminated by adding 130 μl of 1.5 N NH4OH and 40 μl of 100 mM cold l-serine. The labeled product was extracted by addition of 400 μl of CHCl3-CH3OH (5/3 ratio) and 50 μl of 1-mg/ml dihydrosphingosine (as carrier), followed by vigorous mixing. The mixture was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, and the lower organic phase was washed six times with several volumes of water. After drying under a stream of nitrogen, the dried material was redissolved in 100 μl of CHCl3-CH3OH (5/3 ratio), and the radioactivity was measured with a liquid scintillation counter.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The DDBJ (DNA Data Bank of Japan) accession number of the lace cDNA sequence is AB017359.

RESULTS

lace mutant as a responder to Dsor1Su1.

Although flies with Dsor1Su1, a gain-of-function allele of Dsor1, have a slightly higher number of R7-like photoreceptor cells than the wild type (55), most of the adult external organs can develop normally, and their viability is not less than that of the wild type. Dsor1Su1 was thus introduced into various known mutants, and the influence on their phenotypes was examined. We found that introduction of Dsor1Su1 to hypomorphic lace mutants suppressed the lace phenotypes. The lace gene is essential for Drosophila development, since homozygotes of the null allele died during the first instar larval stage with low feeding and locomotive activity (1). Mutants with weak alleles of the lace gene grew into adults with abnormalities in various adult external organs (Fig. 1B to I): the margin was frequently incised, and the ectopic crossvein was present in the wing; in the compound eye, the hexagonal array of ommatidia was disrupted, especially along the equatorial plane; in the notum, the small bristles, microchaetae, lacked pigment and were occasionally absent, while the number of large bristles, macrochaetae, varied; in the leg and antenna, bifurcation of the distal portion was rarely observed. These findings indicate that the lace gene is required for the development of various imaginal discs. The occurrence of all of these phenotypes was considerably suppressed by elevated Dsor1 activity (Fig. 2). This suggests that the function of Lace is related to Dsor1 function in multiple aspects of morphogenesis during pupal-adult metamorphosis.

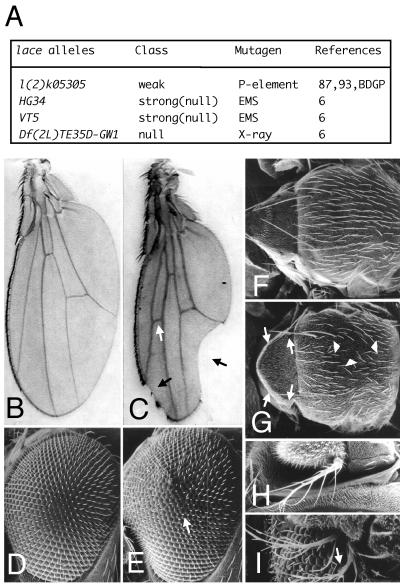

FIG. 1.

lace alleles and the adult phenotypes. (A) The lace alleles used in this study. Homozygotes of the P element-inserted allele l(2)k05305 and all of the heteroallelic combinations with l(2)k05305 partially grew to the adult stage with similar aberrant morphologies. The Df(2L)TE35D-GW1 allele lacks three loci (lace and the adjacent two loci, sna and cycE) (Fig. 3A). All flies with genotypes which had a strong lace allele either inter se or when heterozygous with deletion died just after hatching. EMS, ethyl methanesulfonate. (B to I) Adult lace phenotypes in a lace mutant and wild type. (B, D, F, and H) Wild-type Canton-S. (C, E, G, and I) Transheterozygote lacel(2)k05305/laceHG34. (B and C) Wing. Anterior area is to the left. In the lace mutant, incision of the wing margin and the ectopic crossvein are marked by the filled and open arrows, respectively. The laced vein pattern, a previously identified lace phenotype, is thought to be allele specific or caused by a mutation of a different gene that is linked with lace on the same chromosome. (D and E) Compound eye. Anterior area is to the left, and dorsal area is to the top. In the lace mutant, the hexagonal array of ommatidia is disordered along the equatorial plane (arrow). The deep pseudopupil pattern is normal (1). (F and G) Nota. Dorsal view. Anterior area is to the right. In the lace mutant, microchaetae (arrowheads) and macrochaetae (arrows) were frequently missing. (H and I) Aristae, distal portion of antennae. Anterior area is to the bottom, and dorsal area is to the right. The secondary projection of arista (arrow) was rarely present in the lace mutant.

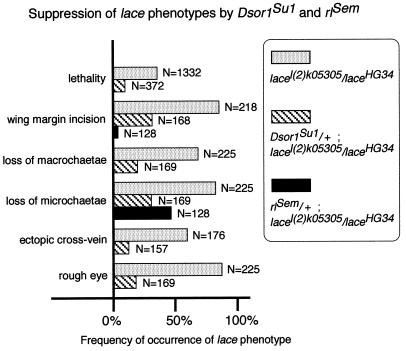

FIG. 2.

Suppression of lacel(2)k05305/laceHG34 adult phenotypes by Dsor1Su1 and rlSem. The frequency of occurrence of each lace phenotype in the indicated number of individuals, N, is shown. The genotypes are indicated in the box. The frequency of occurrence of all of the lace phenotypes was decreased by single-copy introduction of Dsor1Su1. Since more evident restoration was found when Dsor1Su1 was introduced in the male hemizygously [Dsor1Su1/Y; lacel(2)k05305/laceHG34 [1]), suppression occurs in a manner dependent on Dsor1-Rl activity. The rlSem fly itself shows dominant phenotypes of rough eye and an increased number of veins (17). Thus, the lace mutant fly heterozygous for rlSem stably showed these phenotypes. However, the other lace phenotypes such as loss of microchaetae and incision of wing margin were markedly restored by introduction of rlSem.

Multiple components of the same pathway should regulate the same process. Dsor1, a MAPKK, activates the MAPK Rl. Thus, we also tested the effect of introducing rlSem, a gain-of-function allele of rl (17), into the same lace mutants. The rlSem fly itself displays rough eye and an increased number of veins. Thus, it was not clear whether introduction of rlSem into lace mutants affected the lace mutant phenotypes in these organs. However, the lace mutant phenotypes of wing margin incision and loss of microchaetae were clearly suppressed in the lace mutants with rlSem (Fig. 2).

Cloning and structural analysis of lace cDNA.

lacel(2)k05305 contains a single copy of P-lacW (10), a derivative of the P element (73). To test whether the phenotypes of lacel(2)k05305 are caused by insertion of P-lacW, P-lacW was excised by being crossed with PΔ2-3 (82), a transposase supplier strain. Six excised strains were independently established based on the absence of the w+ marker of P-lacW. Five of the six excised strains clearly complemented the parental allele, l(2)k05305, and another lace allele, HG34, demonstrating that lacel(2)k05305 was actually caused by insertion of P-lacW. The remaining strain did not complement the various lace alleles. This is probably due to imprecise excision of the P element, which is known to occur at low frequency.

Thus, the genomic fragment around the P-lacW insertion site in lacel(2)k05305 was cloned by the plasmid rescue technique (21) with the sequences of ori and Ampr of Escherichia coli, both of which are contained in the sequence of P-lacW. Using the obtained genomic fragment as a hybridization probe, we further isolated the longer genomic region from the wild-type Drosophila genomic library constructed in the λEMBL3 vector (25). The approximately 12-kb genomic fragment obtained was used as the probe to screen the imaginal disc cDNA library (16). This probe covered the region 8 kb upstream and 4 kb downstream of the P-lacW insertion site. As a result, a single cDNA clone, pNBlace, was isolated. Comparison of the entire cDNA sequence of pNBlace and the partial genomic sequence encompassing the P-lacW insertion site revealed that P-lacW is inserted 8 to 10 bp upstream from the site corresponding to the 5′ end of the cDNA of pNBlace (Fig. 3A). This strongly suggests that P-lacW insertion interferes with lace gene function and that the cloned cDNA is actually derived from lace mRNA, which will be proven by the transgenic analysis below.

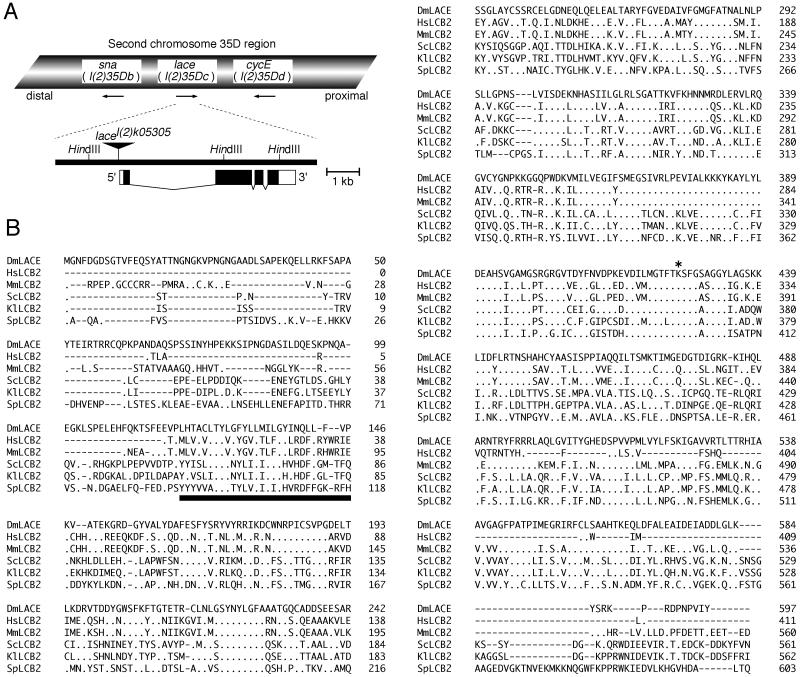

FIG. 3.

Structural organization of the lace gene and alignment of amino acid sequences of Lace and its homologs in other organisms. (A) Schematic representation of the lace gene. The 35D region of the second chromosome is shown on the top, and the approximately 10-kb region of DNA containing the lace gene is shown on the bottom. The arrows below the chromosome denote the transcriptional direction of each gene. The positions of the coding exons and noncoding introns (filled and open boxes, respectively) of the lace gene are indicated in the lower diagram. The P-lacW insertion site in the lacel(2)k05305 allele is indicated by the inverted triangle. The HindIII restriction sites are also indicated. (B) The primary amino acid sequence of Lace in Drosophila was compared with its homologs in other organisms by the Higgins method (DNASIS program; Hitachi Software Engineering Co., Ltd., Yokohama, Japan). DmLACE indicates the amino acid sequence of the lace gene product. HsLCB2, MmLCB2, ScLCB2, KlLCB2, and SpLCB2 represent the amino acid sequences of the LCB2 homologs in humans (Homo sapiens), mice (Mus musculus), budding yeast (S. cerevisiae), another budding yeast (Kluyveromyces lactis), and fission yeast (Schizosaccharomyces pombe), respectively. Gaps were introduced into the sequences to optimize the alignment. Identical residues are indicated with periods. The underlined segment denotes the putative transmembrane helices predicted by Nagiec et al. (68). The N-terminal signal peptide present in many types of membrane proteins is absent in this family of proteins. The asterisk denotes the lysine residue conserved in many members of the aminolevulinate synthase (pyridoxal phosphate-containing acyltransferase) superfamily. The lysine residue forms a Schiff base with pyridoxal phosphate, thereby making up a part of the catalytic site (69). The Asp-86 residue in DmLACE is replaced with His in the sequence presented in the Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project database. It seems to be a polymorphism.

A BLAST search (4) of the entire cDNA sequence of lacel(2)k05305 revealed a match with the long DNA sequences in the Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project database. Comparison of the sequences also indicated that the lace gene consists of four exons (Fig. 3A).

The lace gene encodes a homolog of LCB2, a subunit of SPT. Based on the presence of an upstream in-frame stop codon in the sequence of pNBlace, the cDNA is considered to cover the entire coding region. It encodes a protein composed of 597 amino acid residues showing highest similarity to the murine homolog of LCB2 (57% identity [36, 69, 97]) (Fig. 3B). The LCB2 gene (also known as SCS1 [104]) (SCS stands for suppressor of Ca2+ sensitivity) was originally discovered in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (68) and encodes a subunit of SPT (3-ketosphinganine synthetase [EC 2.3.1.50]) which catalyzes the first step of sphingolipid synthesis, that is, the condensation of serine and palmitoyl-CoA to yield 3-ketosphinganine (63). Sphingolipids are abundant in the plasma membranes of all known eukaryotic cells, and some sphingolipids such as ceramide and sphingosine are second messengers controlling cell proliferation and apoptosis (24, 37, 38, 50, 57, 64). The SPT step has been hypothesized to be the rate-limiting step in the de novo synthesis of sphingolipids (59, 63, 95). SPT is presumed to be localized on the cellular membrane (60, 76), and its apoenzyme is considered to consist of both the LCB1 and LCB2 subunits (19, 36, 68). SPT is essential for the survival of yeast and Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells, unless exogenous sphingosine is added to the culture medium (19, 35). lace gene expression was detected in most tissues of Drosophila (Fig. 4), which is consistent with previous knowledge of the ubiquitous distribution of sphingolipids.

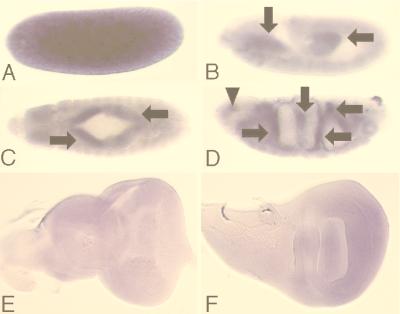

FIG. 4.

Expression of lace during development of normal Drosophila. In situ hybridization with the digoxigenin-labeled antisense RNA probe was performed as previously described (5). (A through D) Embryos. (A) Stage 3. (B) Stage 10. (C) Stage 13. (D) Stage 16. Anterior area is to the left. (A, B, and D) Lateral view; dorsal area is to the top. (C) Dorsal view. lace expression was observed in most of the examined cells. Stronger hybridization signals were detected in the embryonic midgut (arrows) and the head sensory organs (arrowhead). (E) Eye-antennal disc. (F) Wing disc. Expression of lace was observed ubiquitously in these tissues. Control hybridization with the sense lace RNA probe showed no apparent staining.

Lace has SPT activity.

To examine whether Lace has SPT activity in the fly, we first measured the SPT activity in various fly developmental stages. But the SPT activities in both the total cell extract and membrane fraction were very low or not detectable. These observations suggest that a substance(s) which interferes with endogenous SPT activity is present in the fly extract. Therefore, an epitope-tagged version of the lace+ transgenic fly (UAS-HAlace) was established to immunopurify SPT from the fly membrane fraction. When the membrane fraction of the HAlace producer was treated with anti-HA antibody, the SPT activity was absorbed by anti-HA antibody. The activity of the pupal SPT was calculated to be 30 pmol of product/h/mg of membrane protein (Table 1). On the other hand, when the membrane fraction from the nontransgenic (wild-type) fly was similarly treated, no significant activity was absorbed by anti-HA antibody. Therefore, it was concluded that the Lace protein is a component of SPT. Interestingly, in an SPT-deficient CHO cell mutant (35) and in CTLL-2 cells treated with the SPT inhibitor ISP-1 (70), the reduced SPT activity resulted in cell lethality; however, cell growth was restored by addition of exogenous sphingosine. Thus, we tested whether the viability of the Drosophila lace mutant was improved by exogenous addition of sphingosine to the diet (Fig. 5). Similar to the cases in the above mammalian cells, the lethality of a hypomorphic lace mutant was clearly rescued by feeding with sphingosine. Various adult lace mutant phenotypes were also rescued simultaneously. On the other hand, the adult lace mutant phenotypes could not be rescued by exogenous sphingomyelin or ceramide, as in the case of CTLL-2 cells treated with ISP-1 (70). This result also supports the idea that the lethality of the hypomorphic lace mutant is caused by a decreased level of sphingolipid metabolites and that the product of the lace gene has a feature similar to yeast LCB2.

TABLE 1.

Assay of SPT in the membrane preparation from HAlace-producing fly pupae

| Pupa type | Measured value (cpm)a | Actual value (cpm)b | SPT activity (pmol/h/mg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| HAlace producer | |||

| + palmitoyl-CoA (expt 1) | 206.7 | 120.4 | 30.1 |

| − palmitoyl-CoA (expt 1) | 86.3 | ||

| + palmitoyl-CoA (expt 2) | 202.3 | 122.0 | 30.5 |

| − palmitoyl-CoA (expt 2) | 80.3 | ||

| Non-HAlace producer (wild type) | |||

| + palmitoyl-CoA | 78.1 | 0 | 0 |

| − palmitoyl-CoA | 86.6 |

Incorporation of l-[14C]serine into the organic phase was monitored (see Materials and Methods).

Reactions without palmitoyl-CoA were used as controls. Nonenzymatic incorporation of l-[14C]serine with palmitoyl-CoA was negligible (1).

FIG. 5.

Rescue of lace mutant by feeding with sphingosine. Female lacel(2)k05305 heterozygotes [lacel(2)k05305/CyO] were crossed with male laceHG34 heterozygotes (laceHG34/CyO), and progeny were reared on diets containing various concentrations of sphingosine. The number of surviving adult fly progeny of each genotype was counted. The genotype CyO/CyO is lethal. In all cases, the number of lacel(2)k05305 heterozygote progeny was standardized as 1.0. In these experiments, a low-nutrient diet (2% dry yeast [Asahi Beer Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan], 2% standard agar, and 0 μM sphingosine) was used to reduce the supply of sphingolipids from the diet. This led to decreased viability of the hypomorphic lace mutant in comparison with the viability of mutants fed the standard diet (Fig. 2). When d-erythrosphingosine was added to the diet, the viability of the lace mutant was strikingly restored. Various adult phenotypes were also suppressed (1). Viability values over 1.0 were derived from the toxicity of a higher concentration of sphingosine in the lacel(2)k05305 heterozygote. The degree of sphingosine toxicity appears to vary among genotypes. The heterozygote of the mild lace allele, lacel(2)k05305, was the most sensitive to sphingosine toxicity; the heterozygote of a strong lace mutant allele (laceHG34), was less sensitive; and a hypomorphic lace mutant, lacel(2)k05305/laceHG34, was most resistant. The toxicity of sphingosine to wild-type cells has also been documented (70).

Lace has the ability to localize on the membrane.

The lace+ transgenic fly (UAS-HAlace) can clearly rescue the wing (Fig. 6A) by using a wing GAL4 driver, 69B-GAL4, and all other (1) adult phenotypes of the lace hypomorph by using a constitutive GAL4 driver, actin-GAL4. Lethality just after hatching which is associated with the strong lace mutant (laceVT5/laceHG34) can be rescued by actin-GAL4 with UAS-HAlace (1). Approximately 50% of these strong lace mutant flies with the lace+ transgene grew to the adult stage with no aberration. Therefore, together with the result that SPT activity was dependent on this lace+ transgene, it was concluded that all of the lace phenotypes are caused by loss of this gene function. Furthermore, this transgenic fly produced the tagged protein HAlace of the expected size (Fig. 6B). Thus, it was assumed that the subcellular localization of HAlace is identical to that of the native Lace protein. Expression of HAlace in a wild-type background did not result in any visible phenotypes, as in the case of yeast LCB2 (68). The HAlace protein was localized on the plasma membrane of polyploid cells in the salivary gland (Fig. 6C) and diploid cells in the wing imaginal disc of the HAlace producer (Fig. 6D). Most of the sphingolipids in yeasts and mammals are present in the plasma membrane (63, 74). Thus, our immunohistochemical results are consistent with these findings. However, SPT activity in mouse liver cells was reported to be concentrated in the membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum also (60).

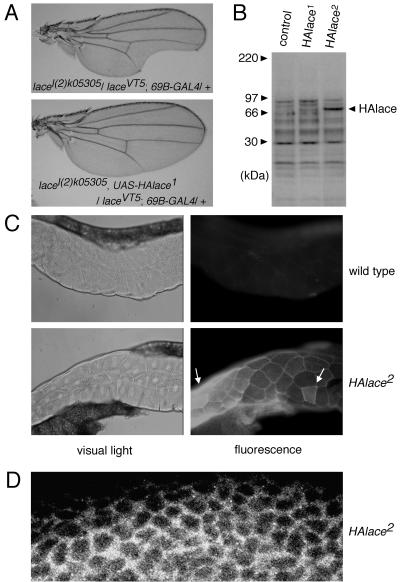

FIG. 6.

Rescue ability, expression, and subcellular localization of HA-tagged Lace protein (HAlace). (A) The wing phenotype of lace was rescued by expression of HAlace. (Upper panel) A wing from lacel(2)k05305/laceVT5 carrying 69B-GAL4, as a control. Incision of the wing margin was not rescued by 69B-GAL4 alone. (Lower panel) A wing from lacel(2)k05305/laceVT5 expressing UAS-HAlace1 by 69B-GAL4. In 90% of the adults, incision of the wing margin was completely restored. By using a stronger UAS line (UAS-HAlace2 [see also panel B]) and other GAL4 drivers, all of the lace phenotypes could be rescued. (B) Detection of HAlace protein expressed in the adult fly by Western blot analysis. The genotype is UAS-HAlace/+; hs (heat shock)-GAL4/+; flies were reared at 25°C without heat shock. The basal activity of the heat shock promoter was sufficient to achieve constitutive expression of GAL4; thus, HAlace was induced even in the absence of heat treatment. The UAS-HAlace1 and UAS-HAlace2 lines expressed the HAlace protein (expected size, 68 kDa, recognized by anti-HA antibody) at a low and a high level, respectively. The HAlace protein was absent in the control fly, which has only hs-GAL4 (control). The chemiluminescent image shown was overexposed to visualize the low expression of HAlace1. In a weaker exposed image, bands other than HAlace were not seen in the strain HAlace2 (1). (C) Subcellular localization of HAlace protein in the polyploid cells of the salivary gland of a HAlace producer, visualized by indirect immunofluorescent cytochemistry. The method was as described elsewhere (5). Left panels are photomicrographs of the salivary gland with visible light. The polyploid nuclei of the salivary gland cells can be seen as white spots. The dark areas along the edge of the salivary gland are the fat bodies. The image on the right is a fluorescent image of that on the left. (Upper panels) A salivary gland from wild-type Canton-S (negative control). Faint staining can be seen at the boundaries between polyploid cells and in the fat bodies. (Lower panels) A salivary gland from a HAlace producer (UAS-HAlace2/+; hs-GAL4/+). Flies were reared as described for panel B. Cells of the salivary gland expressed various levels of HAlace. In cells which expressed lower levels of HAlace, staining was concentrated in the plasma membrane. In cells which expressed higher levels of HAlace (arrows), staining was also seen throughout the cytoplasm. (D) Laser confocal microscopy (laser scanning microscope LSM510; Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) showing subcellular localization of HAlace protein in the diploid cells of the wing imaginal disc from a HAlace producer (same as above). Also, in the diploid cells of the imaginal discs, staining was concentrated in the plasma membrane.

Cell death is induced in the imaginal discs of the lace mutant.

De novo synthesis of sphingolipids is known to be important for regulating the concentration of intracellular ceramide, which elicits cell death as a second messenger in the apoptotic signal (13, 38). Thus, we anticipated that the various aberrant morphologies found as lace phenotypes were caused by deregulation of the apoptotic process. As expected, the wing, leg, and eye-antennal discs of the lace mutant contained a considerably high number of dead cells visualized by acridine orange staining (62) (Fig. 7A). The wing disc contained an especially large number of dead cells, and severe malformation of the primordial wing blade was seen. Also, this apoptosis occurs in a cell-autonomous manner (Fig. 7C). These are consistent with the wing margin incision phenotype. Similar phenotypes found in Drosophila Serrate, vestigial, and scalloped mutants have been reported to be a consequence of increased apoptosis (48, 92, 99). Rare bifurcation of the distal leg and antenna was also thought to be due to increased cell death. Restoration of the lost part of a tissue is occasionally accompanied by secondary projection of the proximodistal axis (18, 86). The rough eye phenotype is also considered to be due, at least in part, to excess apoptosis, because the rough eye phenotype was partially suppressed by forced expression of DIAP1 (Drosophila inhibitor of apoptosis protein [40]) (1). Observation of the apical surface of the developing pupal eye of the lace mutant revealed that the loss of cells occurred among all cell types (Fig. 7B), that is, cone cells, primary pigment cells, secondary pigment cells, tertiary pigment cells, and interommatidial bristles. This suggests that de novo synthesis of sphingolipids is required for the survival of each cell type on the apical surface of the developing eye.

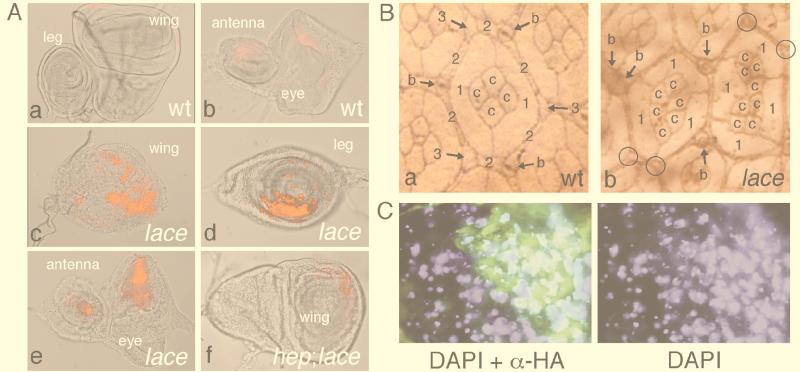

FIG. 7.

Cell death was induced in various imaginal discs of the lace mutant. (A) Imaginal discs stained with acridine orange. The method was as described elsewhere (62). (a and b) Wild type (wt) Canton-S. (c, d, and e) lace mutant [lacel(2)k05305/laceVT5]. (f) lace mutant in a hep-null background [hepr75/Y; lacel(2)k05305/laceVT5]. (a) A leg disc (left) and a wing disc (right). (b and e) An eye-antennal disc. (c and f) A wing disc. (d) A leg disc. In panels a, b, and e, anterior area is to the left. In panels c, d, and f, dorsal area is to the left. In the wing, leg, and antenna discs of the wild type, a few dead cells were seen sporadically. In the eye disc of the wild type, a weak halo caused by naturally occurring cell death was observed in the posterior portion. In the lace mutant, clusters of dead cells were observed in various discs. The wing disc was severely malformed, possibly due to massive cell death. Cell death in the wing and other discs of the lace mutant was suppressed in a hep-null background (f) (1). However, the fact that cell death was not completely suppressed indicates that Hep is not absolutely necessary for induction of apoptosis in the lace mutant. A different MAPKK can also regulate DJNK activity (34, 43, 78). (B) Pupal eye-antennal discs stained with cobalt sulfide. (a) Wild-type Canton-S. c, cone cells; 1, primary pigment cells; 2, secondary pigment cells; 3, tertiary pigment cells; b, bristles. (b) A hypomorphic mutant, lacel(2)k05305/laceVT5. Loss of cells of each type was occasionally observed. Each large ommatidium was generated by fusion of two normal ommatidia. This is presumed to be caused by loss of the secondary and tertiary pigment cells and bristle cells. The fused ommatidium found at left also shows a reduced number of cone cells and primary pigment cells. Absence (circles) and duplication of the bristles are often observed. Small ommatidia with a reduced number of cells are also observed (1). The method of cobalt staining was described elsewhere (101). (C) Apoptosis caused by the lace mutation occurs in a cell-autonomous manner. (Left) A lace mutant wing disc in which the dpp domain expresses the HAlace transgene was double stained with both 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; blue) and anti-HA antibody (green). DAPI stained nuclei, and anti-HA antibody stained the cells rescued by HAlace. The wing dpp domain lies in a narrow belt just anterior to the anteroposterior boundary. The genotype is lacel(2)k05305/laceVT5, UAS-HAlace2; blk-GAL4/+. blk-GAL4 is a GAL4 transgene driven by one of the dpp gene enhancers (67). (Right) DAPI-alone image of that on the left. Small nuclei fragmented by apoptosis (arrows) are extensively seen in areas outside the HAlace-expressing domain. The methods of staining with DAPI and antibody were described elsewhere (5).

Induction of apoptosis in the lace mutant is mediated by activation of the DJNK pathway.

In mammals, the induction of apoptosis by sphingolipid is mediated by activation of JNK (96). Sphingolipid is also involved in regulating cell death in Drosophila (77). To examine the relationship between Lace and the DJNK cascade in controlling apoptosis, the level of DJNK activation was assessed by the level of expression of the puc-lacZ reporter gene in the lace mutant and in the wild type. Puc (Puckered) is a dual-specificity phosphatase that is induced by the DJNK signal and inactivates active DJNK during embryonic dorsal closure (61, 81). At the late third instar larval stage, puc expression in most tissues except for the central nervous system was dependent on the presence of Hep (Hemipterous [29]), a MAPKK specific for DJNK (1, 3). In addition, puc expression was ectopically induced when a constitutively active mutant protein of Hep (HepCA) was expressed in the wing disc (3). Both results indicate that the level of puc expression is a good indicator of JNK activity in the imaginal discs.

In the wing disc of the wild type, puc expression was observed only in the scutellum anlage and in several cells on the peripodial membrane (Fig. 8Aa). Although puc was not expressed in the wing blade primordium of the wild type, there was strong ectopic expression in the wing blade primordium of the lace hypomorph (Fig. 8Ba) in a cell-autonomous manner (Fig. 8D). Similar ectopic expression of puc was also observed in various other imaginal discs of the lace mutant (Fig. 8Bb and Bc). In addition, there was elevated expression of puc in the salivary gland, a larval tissue which begins to undergo apoptosis at the late larval stage, of the lace mutant (Fig. 8Bd). Because ectopic puc expression was not seen in a hep-null background (Fig. 8Ca through Cc) except in the polyploid cells of the salivary gland (Fig. 8Cd), puc expression in most tissues requires Hep, and Hep is activated in these tissues in the lace mutant. Interestingly, activation of DJNK was required for inducing apoptosis. Introduction of the null mutation of hep into the lace mutant resulted in suppression of both cell death induction and the wing disc malformation (Fig. 7Af and 8Ca). Reducing the gene dosage of hep by half resulted in significant suppression of the hypomorphic lace phenotypes (1); this also supports a link between Lace and the DJNK cascade. Thus, the two phenomena induced in the lace mutant, apoptosis and DJNK activation, are tightly linked events rather than parallel results. However, the location of cells expressing puc and the location of cells that were stained with acridine orange, which indicates dying cells, did not precisely coincide. This might indicate that activation of DJNK does not directly induce cell death. However, this discordance is possibly due to another reason, that is, that the distribution of DJNK-active cells varies among individuals (see legend to Fig. 8). Also, acridine orange does not stain all dying cells but rather stains cells in the early stage of the apoptotic process. In mammalian cultured cells, apoptosis induced either by activating JNK (46) or by interfering with SPT via ISP-1 (70) is an event which occurs in a single cell and is not thought to require secondary intercellular interaction. In our experiments with Drosophila, DJNK activation and apoptosis by lace mutation occur cell autonomously (Fig. 7C and 8D). Furthermore, forced expression of HepCA in the wing induces apoptosis (3). We thus postulate that induction of massive apoptosis in the lace mutant requires activation of the DJNK pathway.

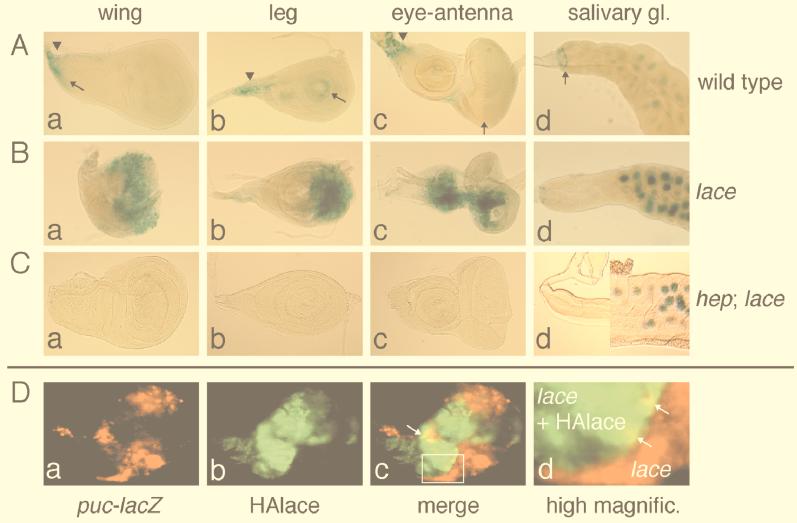

FIG. 8.

puc is ectopically expressed in various tissues of the lace mutant in a cell-autonomous manner. All tissues were dissected from late third instar larvae. (A) X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) staining of puc-lacZ reporter gene product in a wild-type background (pucE69/+). Normal expression in peripodial membrane cells is marked by the arrowheads. (B) X-Gal staining of puc-lacZ reporter gene product in a lace mutant [lacel(2)k05305/laceVT5; pucE69/+]. Strong ectopic expression of puc can be seen in various disc cells. Although a lacZ reporter gene is present in the P-lacW transposon (8) of the lacel(2)k05305 allele, it is not expressed in the imaginal discs of the wild type or in the imaginal discs of lace mutant flies (1). Therefore, the lacZ expression observed here is solely derived from pucE69. (C) X-Gal staining of puc-lacZ reporter gene product in a lace mutant in a hep-null background [hepr75/Y; lacel(2)k05305/laceVT5; pucE69/+]. Both endogenous and ectopic puc expression in all puc-expressing imaginal discs were greatly reduced. (Aa, Ba, and Ca) Wing disc. Anterior area is to the top, and dorsal area is to the right. Normal expression of puc in the scutellum primordium is indicated by the arrow. (Ab, Bb, and Cb) Leg disc. Anterior area is to the top, and dorsal area is to the right. Weak expression of puc is present in a ring surrounding the primordial distal part in the wild type (arrow). In the lace mutants, the location of the ectopic puc-expressing region varied among individuals. Whereas this example shows a wide region of puc expression on the ventral surface, other samples showed a wide region of the expression on the dorsal surface (1). (Ac, Bc, and Cc) Eye-antennal disc. Anterior area is to the left. The normal weak expression of puc in the eye can be observed posterior to the morphogenetic furrow (arrow). (Ad, Bd, and Cd) Salivary gland. Proximal area is to the left. In the wild type, strong expression of puc can be seen in several cells just distal to the imaginal ring (arrow), and weak expression of puc is seen in the polyploid salivary gland cells. The puc promoter-driven lacZ expression showed localization of E. coli β-galactosidase to polyploid nuclei. Expression of puc-lacZ found in the polyploid nuclei is increased in a lace mutant background but is independent of hep, which is different from the case in the imaginal discs. (D) A wing disc from a lace mutant with puc-lacZ reporter in which the dpp domain expresses the HAlace transgene was double stained by both anti-β-galactosidase and anti-HA antibodies. The genotype is lacel(2)k05305/laceVT5, UAS-HAlace2; pucE69/blk-GAL4. (a) Staining with anti-β-galactosidase antibody (red), indicating expression of puc-lacZ reporter. (b) Staining with anti-HA antibody (green), indicating the forced expression of UAS-HAlace driven by blk-GAL4. blk-GAL4 is a GAL4 transgene driven by one of the dpp gene enhancers (67) and is expressed in a narrow belt just anterior to the anteroposterior boundary. (c) Superimposed image of panels a and b. (d) High-magnification view of the boxed area around the anteroposterior boundary in panel c. In the wing primordium, the majority of the ectopic puc induction by the lace mutation was lost within the dpp domain where HAlace was expressed. The puc-expressing domain tends to separate from the HAlace-expressing domain, although both domains overlap in the small regions (yellow; arrows in panels c and d). This nonautonomous induction of puc is probably due to the incomplete rescue by the HAlace transgene.

DISCUSSION

The ERK pathway may serve as a survival signal antagonistic to the apoptotic JNK signal.

We have found that the lace mutant responds to Dsor1Su1. The hyper-ERK signal may suppress the lace phenotype by being antagonistic to the apoptotic DJNK pathway (Fig. 9). It is known that the small eye phenotype caused by forced expression of Hid (32), a Drosophila protein which induces apoptosis, is suppressed by a hyperactivated Dsor1-Rl signal (83). This suppression is mediated by down-regulation of hid gene expression (52) and inactivation of Hid protein through phosphorylation by Rl (8). The DER (Drosophila homolog of epidermal growth factor receptor) signal also prevents cell death in the eye through the Dsor1-Rl cascade (65). Similar results have also been obtained with mammals: nerve growth factor promotes cell survival through the ERK pathway in PC12 cells (102). Mice lacking B-raf, an upstream activator of the ERK pathway, had an increased level of apoptosis of vascular endothelial cells (100). Thus, there is strong evidence that hyperactivation of Dsor1-Rl signaling suppresses the apoptotic lace phenotype.

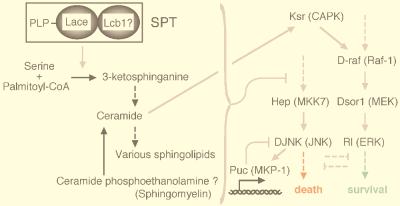

FIG. 9.

Proposed relationship between the Lace and MAPK cascades in the imaginal disc cells. The black and gray arrows indicate metabolic conversions and enzymatic actions, respectively. The solid and broken arrows indicate direct and indirect conversions and/or actions, respectively. It is predicted that the Lace protein associates with an LCB1 subunit to form an apoenzyme of SPT, based on knowledge of the budding yeast and CHO cells (19, 36, 68). Pyridoxal phosphate (PLP) is thought to bind to Lace as a coenzyme. SPT catalyzes the first step of sphingolipid biosynthesis, that is, condensation of serine and palmitoyl-CoA to yield 3-ketosphinganine. 3-Ketosphinganine is metabolically converted to ceramide and various other sphingolipids. Ceramide is also produced through the sphingomyelin pathway, which is initiated by hydrolysis of sphingomyelin. In dipteran insects, ceramide phosphoethanolamine, instead of sphingomyelin, is presumed to be hydrolyzed. A decrease in the rate of de novo sphingolipid synthesis via SPT removes repression of the DJNK cascade and elicits apoptosis. The Rl cascade is antagonistic to the apoptotic DJNK pathway. Ksr (CAPK) is known to be activated by ceramide (103). The mammalian homologs are indicated in parentheses.

It has recently been reported that a protein kinase activated by ceramide (ceramide-activated protein kinase [CAPK]) activates Raf-1 to provoke apoptosis in response to tumor necrosis factor alpha (103). Raf-1 is a MAPKK kinase which phosphorylates and activates MEK, which, in turn, activates ERK (Fig. 9). CAPK has also been referred to as kinase suppressor of ras (Ksr) (90, 91); Ksr is essential for various aspects of Drosophila development regulated by the Dsor1-Rl signaling pathway. Thus, it is also possible that the regulation of cell survival by Lace is mediated by Ksr. At present, however, our preliminary experiments do not show any genetic interaction between lace and ksr. We suspect that the MAPK cascade controlled by Lace and that controlled by Ksr serve different functions in Drosophila development. In fact, the eye, wing, and embryonic phenotypes of the ksr mutant are similar to those of the Dsor1 and rl mutants, while the lace mutant does not show such phenotypes.

De novo synthesis of sphingolipid is essential for cell survival control in Drosophila development.

SPT encoded by the LCB2/lace gene catalyzes the first step in the biosynthesis of sphingolipids. De novo synthesis of sphingolipid through SPT activity is important for cell survival in mammalian cultured cells and yeast cells. Treating an interleukin-2-dependent cytotoxic T-cell line, CTLL-2, with the sphingosine-like immunosuppressant ISP-1 (66), which inhibits SPT, elicited apoptosis (70). This apoptosis was suppressed by the addition of sphingosine. It has also been shown elsewhere that the yeast mutant lcb2 and a CHO cell mutant lacking SPT activity cannot survive unless exogenous long-chain base is added to the culture medium (35, 75). Our present study demonstrated that the LCB2 homolog lace is also required for proper development of Drosophila through repression of apoptosis. Apoptosis caused by the lace mutation occurred in a cell-autonomous fashion (Fig. 7C). However, we have not yet determined which particular species of sphingolipid is responsible for the deregulation of cell death observed in the lace mutant. Although the primary cause of this apoptosis lies in the mutation of the lace gene, it remains unclear whether the increased or decreased amount of sphingolipid provoked apoptosis, since the in vivo proportions of various sphingolipid molecules seem to be balanced. A decreased level of a particular sphingolipid species results in an increase in other sphingolipid species (20, 42, 54, 89, 104). It is presumed to be very difficult to biochemically identify the molecule responsible for apoptosis, since an immense amount of wing disc from lace mutants would be required. Alternatively, screening for modifier mutants against a lace hypomorph might lead to identification of the enzymes regulating sphingolipid metabolism downstream of Lace.

Sensitivity to loss of Lace activity varies among tissues.

It is noteworthy that the degree of DJNK activation and the degree of cell death induction varied in different tissues of the lace mutant. Only a limited group of growing tissues including the wing, leg, and eye-antennal imaginal discs were found to be sensitive to the lace mutation. The majority of larval tissues were insensitive to the lace mutation.

The tissue most sensitive to the lace mutation was the wing imaginal disc, which showed a greatly increased number of dead cells and severe malformation (Fig. 7Ac). In contrast, the leg and antenna discs showed a moderately increased number of dead cells. These discs were not malformed, and emergence of the adult phenotype was also rare. These differences among tissues are often observed with genes which regulate the morphogenesis of multiple organs. For example, although DER is known to regulate the entire cuticle pattern of the adult fly (23), a hypomorph of this gene, torpedo, displays a defect in only the wing vein among the many adult external organs (56). While Lace is also considered to regulate the development of many adult organs, the degree of its requirement varies among tissues.

The tissue most insensitive to the lace mutation was the larval epidermis, which showed neither an increase in the number of dead cells nor an increase in DJNK activity. Its morphology was also indistinguishable from that of the wild type (1). Although the larval salivary gland cells of the lace mutant had elevated DJNK activity (Fig. 8Bd), the effect of the mutant on apoptosis induction was unclear. Therefore, it is thought that Lace activity is not important for maintenance of the polyploid cells of most larval tissues.

A difference in the sensitivity of different cell types to reduced SPT activity has also been reported for mammalian cells. While CTLL-2 cells undergo apoptosis after treatment with ISP-1 (70), F7 cells subjected to the same treatment do not undergo apoptosis.

The de novo synthetic pathway of sphingolipid, in addition to the sphingomyelin hydrolytic pathway, regulates JNK activity.

It has now unequivocally been established that ceramide is produced via several biochemical pathways in mammalian cells (38): one major pathway is initiated by hydrolysis of sphingomyelin, and the second pathway is de novo synthesis through the activity of SPT and ceramide synthase. Both pathways induce apoptosis (38), and the first pathway is known to activate JNK (96). Our genetic results from Drosophila indicate that the de novo synthesis pathway can also regulate JNK activity cell autonomously (Fig. 8D), although we do not demonstrate whether ceramide acts in this process.

It has been reported that ceramide induces apoptosis in Drosophila cells (77). However, sphingomyelin is not present in dipteran insects (41, 44, 47). Nevertheless, this does not indicate the absence of a hydrolytic pathway that produces ceramide. An alternative sphingolipid species with a structure similar to sphingomyelin (i.e., ceramide phosphoethanolamine) may take the place of sphingomyelin in ceramide synthesis by hydrolytic degradation. It is thus inferred that both the hydrolytic and de novo synthetic pathways regulate cell survival by controlling the DJNK cascade.

Another possible hypothesis is that a mutation in hep does not suppress apoptosis directly; that is, the morphological defect exhibited by lace mutants induces apoptosis, and the hep mutation suppresses the morphological defect caused by a lace mutation. As a result, it would seem that the hep mutation suppresses apoptosis. In this case, Hep does not regulate apoptosis directly. We cannot rule out this possibility at present. However, when a restricted wing zone in a hypomorphic lace mutant was rescued by the lace+ transgene, cells in this zone did not die, although the whole wing still showed a severe morphological defect. Thus, the apoptosis caused by the lace mutation does not lie in the process of restoration of an entire tissue. In fact, when an antiapoptotic baculoviral protein, p35 (39), was expressed in a lace mutant, malformation of the wing disc was suppressed without a visible morphological defect (1). Furthermore, the mammalian cultured cell line CTLL-2, which does not constitute a tissue, underwent apoptosis in response to a reduction in SPT activity (70). Also, activation of the Hep-DJNK cascade in the Drosophila wing (3), as well as activation of the JNK cascade in mammalian cells (46), is sufficient for induction of apoptosis. Thus, we currently prefer the former hypothesis that Lace represses the Hep-DJNK cascade which induces apoptosis.

The Drosophila death domain protein Rpr (Reaper) (98) elicits apoptosis by causing an elevation in ceramide level. For example, the number of cells in the compound eye was drastically reduced by massive apoptosis in response to the forced expression of Rpr driven by an eye-specific artificial promoter, GMR (Glass Multimer Reporter; genotype is GMR-rpr/+) (40). However, it is not known which ceramide synthetic pathway is involved in this process. When a lace mutation was introduced in this Rpr overproducer [genotype, lacel(2)k05305/laceHG34; GMR-rpr/+), the eye phenotype was not influenced (1). This result suggests that the Rpr-induced elevation of ceramide level is not mediated by de novo synthesis through SPT. The sphingolipids produced by de novo synthesis may be distinct from the sphingolipids produced via the hydrolytic pathway, and they probably play distinct roles in the control of cell survival, which will be elucidated in future studies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Michael Ashburner, Bruce A. Hay, Yoshihiro H. Inoue, István Kiss, Enrique Martín-Blanco, Alfonso Martinez-Arias, Makoto Nakamura, Stéphane Noselli, John Roote, Gerald M. Rubin, Kuniaki Takahashi, Yoshihiro Takatsu, and Daisuke Yamamoto for providing fly stocks and Nicholas H. Brown, Kazuhiro Furukawa, and Norbert Perrimon for providing plasmid DNAs. We are also grateful to Keiko Tamiya-Koizumi, M. Marek Nagiec, Robert L. Lester, Toshiro Okazaki, Mutsumi Sugita, and Etsuji Wakisaka for valuable information; Kana Dohmoto and Tomiko Tsuboi for technical assistance; and Michael B. O’Connor for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the Tokai Scholarship Foundation to T.A.-Y.; the Kurata Foundation to T.A.-Y.; the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan to T.A.-Y. and Y.N.; and the Japan Society of Promotion of Science to M.T.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adachi-Yamada, T. Unpublished data.

- 2.Adachi-Yamada T, Nakamura M, Irie K, Tomoyasu Y, Sano Y, Mori E, Goto S, Ueno N, Nishida Y, Matsumoto K. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase can be involved in transforming growth factor β superfamily signal transduction in Drosophila wing morphogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:2322–2329. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.3.2322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adachi-Yamada T, Fujimura-Kamada K, Nishida Y, Matsumoto K. Distortion of proximodistal information causes JNK-dependent apoptosis in Drosophila wing. Nature. 1999;400:166–169. doi: 10.1038/22112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ashburner M. Drosophila, a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ashburner M, Thompson P, Roote J, Lasko P F, Grau Y, Messal M E, Roth S, Simpson P. The genetics of a small autosomal region of Drosophila melanogaster containing the structural gene for alcohol dehydrogenase. VII. Characterization of the region around the snail and cactus loci. Genetics. 1990;126:679–694. doi: 10.1093/genetics/126.3.679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Becker G W, Lester R L. Biosynthesis of phosphoinositol-containing sphingolipids from phosphatidylinositol by a membrane preparation from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol. 1980;142:747–754. doi: 10.1128/jb.142.3.747-754.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bergmann A, Agapite J, McCall K, Steller H. The Drosophila gene hid is a direct molecular target of Ras-dependent survival signaling. Cell. 1998;95:331–341. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81765-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project. 19 May 1999. [Online.] http://www.fruitfly.org. [17 August 1999, last date accessed.]

- 10.Bier E, Vaessin H, Shepherd S, Lee K, MacCall K, Barbel S, Ackerman L, Carretto R, Uemura T, Grell E, Jan L Y, Jan Y N. Searching for pattern and mutation in the Drosophila genome with a P-lacZ vector. Genes Dev. 1989;3:1273–1287. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.9.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biggs W H, III, Zavitz K H, Dickson B, van der Straten A, Brunner D, Hafen E, Zipursky S L. The Drosophila rolled locus encodes a MAP kinase required in the sevenless signal transduction pathway. EMBO J. 1994;13:1628–1636. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06426.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blumer K J, Johnson G L. Diversity in function and regulation of MAP kinase pathways. Trends Biochem Sci. 1994;19:236–240. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90147-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bose R, Verheij M, Haimovitz-Friedman A, Scotto K, Fuks Z, Kolesnick R. Ceramide synthase mediates daunorubicin-induced apoptosis: an alternative mechanism for generating death signals. Cell. 1995;82:405–414. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90429-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boutros M, Paricio N, Strutt D I, Mlodzik M. Dishevelled activates JNK and discriminates between JNK pathways in planar polarity and wingless signaling. Cell. 1998;94:109–118. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81226-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brand A H, Perrimon N. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotype. Development. 1993;118:401–415. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown N H, Kafatos F C. Functional cDNA libraries from Drosophila embryo. J Mol Biol. 1988;203:425–437. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brunner D, Oellers N, Szabad J, Biggs III W H, Zipursky S L, Hafen E. A gain-of-function mutation in Drosophila MAP kinase activates multiple receptor tyrosine kinase signaling pathway. Cell. 1994;76:875–888. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90362-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bryant P J. Localized cell death caused by mutations in a Drosophila gene coding for a transforming growth factor-β homolog. Dev Biol. 1988;128:386–395. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(88)90300-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buede R, Rinker-Schaffer C, Pinto W J, Lester R L, Dickson R C. Cloning and characterization of LCB1, a Saccharomyces gene required for biosynthesis of the long-chain base component of sphingolipids. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4325–4332. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.14.4325-4332.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coetzee T, Fujita N, Dupree J, Shi R, Blight A, Suzuki K, Suzuki K, Popko B. Myelination in the absence of galactocerebroside and sulfatide: normal structure with abnormal function and regional instability. Cell. 1996;86:209–219. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cooley L, Kelley R, Spradling A. Insertional mutagenesis of the Drosophila genome with single P elements. Science. 1988;239:1121–1128. doi: 10.1126/science.2830671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davis R J. MAPKs: new JNK expands the group. Trends Biochem Sci. 1994;19:470–473. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90132-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diaz-Benjumea F J, Hafen E. The sevenless signalling cassette mediates Drosophila EGF receptor function during epidermal development. Development. 1994;120:569–578. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.3.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Divecha N, Irvine R F. Phospholipid signaling. Cell. 1995;80:269–278. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90409-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frischauf A M, Lehrach H, Poustka A, Murray N. Lambda replacement vectors carrying polylinker sequences. J Mol Biol. 1983;170:827–842. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80190-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Furukawa K, Hotta Y. cDNA cloning of a germ cell specific lamin B3 from mouse spermatocytes and analysis of its function by ectopic expression in somatic cells. EMBO J. 1993;12:97–106. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05635.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gabay L, Seger R, Shilo B-Z. In situ activation pattern of Drosophila EGF receptor pathway during development. Science. 1997;277:1103–1106. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5329.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gabay L, Seger R, Shilo B-Z. MAP kinase in situ activation atlas during Drosophila embryogenesis. Development. 1997;124:3535–3541. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.18.3535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glise B, Bourbon H, Noselli S. hemipterous encodes a novel Drosophila MAP kinase kinase, required for epithelial cell sheet movement. Cell. 1995;83:451–461. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90123-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glise B, Noselli S. Coupling of Jun amino-terminal kinase and Decapentaplegic signaling pathways in Drosophila morphogenesis. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1738–1747. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.13.1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goberdohan D C I, Wilson C. JNK, cytoskeletal regulator and stress response kinase? A Drosophila perspective. Bioessays. 1998;20:1009–1019. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199812)20:12<1009::AID-BIES7>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grether M E, Abraham J M, Agapite J, White K, Steller H. The head involution defective gene of Drosophila melanogaster functions in programmed cell death. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1694–1708. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.14.1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Han S-J, Choi K-Y, Brey P T, Lee W-J. Molecular cloning and characterization of a Drosophila p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 1998;279:369–374. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.1.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Han Z S, Enslen H, Hu X, Meng X, Wu I-H, Barrett T, Davis R J, Ip Y T. A conserved p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway regulates Drosophila immunity gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3527–3539. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.6.3527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hanada K, Nishijima M, Kiso M, Hasegawa A, Fujita S, Ogawa T, Akamatsu Y. Sphingolipids are essential for the growth of Chinese hamster ovary cells. Restoration of the growth of a mutant defective in sphingoid base biosynthesis by exogenous sphingolipids. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:23527–23533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hanada K, Hara T, Nishijima M, Kuge O, Dickson R C, Nagiec M M. A mammalian homolog of yeast LCB1 encodes a component of serine palmitoyltransferase, the enzyme catalyzing the first step in sphingolipid synthesis. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:32108–32114. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.32108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hannun Y A. The sphingomyelin cycle and the second messenger function of ceramide. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:3125–3128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hannun Y A. Functions of ceramide in coordinating cellular responses to stress. Science. 1996;274:1855–1859. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5294.1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hay B A, Wolff T, Rubin G M. Expression of baculovirus P35 prevents cell death in Drosophila. Development. 1994;120:2121–2129. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.8.2121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hay B A, Wassarman D A, Rubin G M. Drosophila homologs of baculovirus inhibitor of apoptosis proteins function to block cell death. Cell. 1995;83:1253–1262. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90150-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Helling F, Dennis R D, Weske B, Nores G, Peter-Katalinic J, Dabrowski U, Egge H, Wiegandt H. Glycolipids in insects. The amphoteric moiety, N-acetylglucosamine-linked phosphoethanolamine, distinguishes a group of ceramide oligosaccharides from the pupae of Calliphora vicina (Insecta: Diptera) Eur J Biochem. 1991;200:409–421. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hidari K I-P J, Ichikawa S, Fujita T, Sakiyama H, Hirabayashi Y. Complete removal of sphingolipids from the plasma membrane disrupts cell to substratum adhesion of mouse melanoma cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:14636–14641. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.24.14636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Holland P M, Suzanne M, Campbell J S, Noselli S, Cooper J A. MKK7 is a stress-activated mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase functionally related to hemipterous. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:24994–24998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.40.24994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hori T, Itasaka O, Sugita M, Arakawa I. Isolation of sphingoethanolamine from pupae of the green-bottle fly, Lucilia caesar. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1968;64:123–124. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a128857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hou X S, Goldstein E S, Perrimon N. Drosophila Jun relays the Jun amino-terminal kinase signal transduction pathway to the Decapentaplegic signal transduction pathway in regulating epithelial cell sheet movement. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1728–1737. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.13.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ip Y T, Davis R J. Signal transduction by the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK)—from inflammation to development. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:205–219. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Itonori S, Nishizawa M, Suzuki M, Inagaki F, Hori T, Sugita M. Polar glycosphingolipids in insect: chemical structures of glycosphingolipid series containing 2′-aminoethylphosphoryl-(→6)-N-acetylglucosamine as a polar group from larvae of the green-bottle fly, Lucilia caesar. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1991;110:479–485. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a123607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.James A A, Bryant P J. Mutations causing pattern deficiencies and duplications in the imaginal wing disk of Drosophila melanogaster. Dev Biol. 1981;85:39–54. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(81)90234-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Knoblich J A, Sauer K, Jones L, Richardson H, Saint R, Lehner C F. Cyclin E controls S phase progression and its down-regulation during Drosophila embryogenesis is required for the arrest of cell proliferation. Cell. 1994;77:107–120. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90239-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kolesnick R, Golde D W. The sphingomyelin pathway in tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-1 signaling. Cell. 1994;77:325–328. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90147-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kolodziej P, Young R A. RNA polymerase II subunit RPB3 is an essential component of the mRNA transcription apparatus. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:5387–5394. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.12.5387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kurada P, White K. Ras promotes cell survival in Drosophila by downregulating hid expression. Cell. 1998;95:319–329. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81764-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kyriakis J M, Avruch J. Protein kinase cascades activated by stress and inflammatory cytokines. Bioessays. 1996;18:567–577. doi: 10.1002/bies.950180708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lester R L, Wells G B, Oxford G, Dickson R C. Mutant strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae lacking sphingolipids synthesize novel inositol glycerophospholipids that mimic sphingolipid structure. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:845–856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lim Y-M, Tsuda L, Inoue Y H, Irie K, Adachi-Yamada T, Hata M, Nishi Y, Matsumoto K, Nishida Y. Dominant mutations of Drosophila MAP kinase kinase and their activities in Drosophila and yeast MAP kinase cascades. Genetics. 1997;146:263–273. doi: 10.1093/genetics/146.1.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lindsley D L, Zimm G G. The genome of Drosophila melanogaster. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press, Inc.; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liscovitch M, Cantley L C. Lipid second messengers. Cell. 1994;77:329–334. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90148-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lu X, Melnick M B, Hsu J C, Perrimon N. Genetic and molecular analyses of mutations involved in Drosophila raf signal transduction. EMBO J. 1994;13:2592–2599. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06549.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mandon E C, van Echten G, Birk R, Schmidt R R, Sandhoff K. Sphingolipid biosynthesis in cultured neurons. Eur J Biochem. 1991;198:667–674. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mandon E C, Ehses I, Rother J, van Echten G, Sandhoff K. Subcellular localization and membrane topology of serine palmitoyltransferase, 3-dehydrosphinganine reductase, and sphinganine N-acyltransferase in mouse liver. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:11144–11148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Martín-Blunco E, Gampel A, Ring J, Virdee K, Kirov N, Tolkovsky A M, Martinez-Arías A. puckered encodes a phosphatase that mediates a feedback loop regulating JNK activity during dorsal closure in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 1998;12:557–570. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.4.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Masucci J D, Miltenberger R J, Hoffmann F M. Pattern-specific expression of the Drosophila decapentaplegic gene in imaginal disks is regulated by 3′ cis-regulatory elements. Genes Dev. 1990;4:2011–2023. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.11.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Merrill A H, Jr, Jones D D. An update of the enzymology and regulation of sphingomyelin metabolism. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990;1044:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(90)90211-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Merrill A H, Jr, Liotta D C, Riley R T. Fumonisins: fungal toxins that shed light on sphingolipid function. Trends Cell Biol. 1996;6:218–223. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(96)10021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Miller D T, Cagan R L. Local induction of patterning and programmed cell death in the developing Drosophila retina. Development. 1998;125:2327–2335. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.12.2327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Miyake Y, Kozutsumi Y, Nakamura S, Fujita T, Kawasaki T. Serine palmitoyltransferase is the primary target of a sphingosine-like immunosuppressant, ISP-1/myriocin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;211:396–403. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Morimura S, Maves L, Chen Y, Hoffmann F M. decapentaplegic overexpression affects Drosophila wing and leg imaginal disc development and wingless expression. Dev Biol. 1996;177:136–151. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nagiec M M, Baltisberger J A, Wells G B, Lester R L, Dickson R C. The LCB2 gene of Saccharomyces and the related LCB1 gene encode subunits of serine palmitoyltransferase, the initial enzyme in sphingolipid synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:7899–7902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.17.7899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nagiec M M, Lester R L, Dickson R C. Sphingolipid synthesis: identification and characterization of mammalian cDNAs encoding the Lcb2 subunit of serine palmitoyltransferase. Gene. 1996;177:237–241. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00309-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nakamura S, Kozutsumi Y, Sun Y, Miyake Y, Fujita T, Kawasaki T. Dual roles of sphingolipids in signaling of the escape from and onset of apoptosis in a mouse cytotoxic T-cell line, CTLL-2. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:1255–1257. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.3.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nishida E, Gotoh Y. The MAP kinase cascade is essential for diverse signal transduction pathways. Trends Biochem Sci. 1993;18:128–131. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(93)90019-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Noselli S. JNK signalings and morphogenesis in Drosophila. Trends Genet. 1998;14:33–38. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(97)01320-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.O’Hare K, Rubin G M. Structures of P transposable elements and their sites of insertion and excision in the Drosophila melanogaster genome. Cell. 1983;34:25–35. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Patton J L, Lester R L. The phosphoinositol sphingolipids of Saccharomyces cerevisiae are highly localized in the plasma membrane. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:3101–3108. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.10.3101-3108.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pinto W J, Srinivasan B, Shepherd S, Schmidt A, Dickson R C, Lester R L. Sphingolipid long-chain-base auxotrophs of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: genetics, physiology, and a method for their selection. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:2565–2574. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.8.2565-2574.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pinto W J, Wells G W, Lester R L. Characterization of enzymatic synthesis of sphingolipid long-chain bases in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: mutant strains exhibiting long-chain-base auxotrophy are deficient in serine palmitoyltransferase activity. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:2575–2581. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.8.2575-2581.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pronk G J, Ramer K, Amiri P, Williams L T. Requirement of an ICE-like protease for induction of apoptosis and ceramide generation by REAPER. Science. 1996;271:808–810. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5250.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Riesgo-Escovar J R, Jenni M, Fritz A, Hafen E. The Drosophila Jun-N-terminal kinase is required for cell morphogenesis but not for Djun-dependent cell fate specification in the eye. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2759–2768. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.21.2759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Riesgo-Escovar J R, Hafen E. Drosophila Jun kinase regulates expression of decapentaplegic via the ETS-domain protein Aop and the AP-1 transcription factor Djun during dorsal closure. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1717–1727. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.13.1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Riesgo-Escovar J R, Hafen E. Common and distinct roles of Dfos and Djun during Drosophila development. Science. 1997;278:669–672. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5338.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ring J M, Martinez-Arías A. puckered, a gene involved in position-specific cell differentiation in the dorsal epidermis of the Drosophila larva. Development. 1993;121(Suppl.):251–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Robertson H M, Preston C R, Phillis R W, Johnson-Schlitz D M, Benz W K, Engels W R. A stable source of P-element transposase in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1988;118:461–470. doi: 10.1093/genetics/118.3.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sawamoto K, Taguchi A, Hirota Y, Yamada C, Jin M-H, Okano H. Argos induces programmed cell death in the developing Drosophila eye by inhibition of the Ras pathway. Cell Death Differ. 1998;5:262–270. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Seed B. An LFA-3 cDNA encodes a phospholipid-linked membrane protein homologous to its receptor CD2. Nature. 1987;329:840–842. doi: 10.1038/329840a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sluss H K, Han Z, Barrett T, Davis R J, Ip Y T. A JNK signal transduction pathway that mediates morphogenesis and an immune response in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2745–2758. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.21.2745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Spencer F A, Hoffman F M, Gelbart W M. Decapentaplegic: a gene complex affecting morphogenesis in Drosophila melanogaster. Cell. 1982;28:451–461. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90199-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Spradling A C, Stern D M, Kiss I, Roote J, Laverty T, Rubin G M. Gene disruptions using P transposable elements: an integral component of the Drosophila genome project. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:10824–10830. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.10824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Strutt D I, Weber U, Mlodzik M. The role of RhoA in tissue polarity and Frizzled signalling. Nature. 1997;387:292–295. doi: 10.1038/387292a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Takamiya K, Yamamoto A, Furukawa K, Yamashiro S, Shin M, Okada M, Fukumoto S, Haraguchi M, Takeda N, Fujimura K, Sakae M, Kishikawa M, Shiku H, Furukawa K, Aizawa S. Mice with disrupted GM2/GD2 synthase gene lack complex gangliosides but exhibit only subtle defects in their nervous system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:10662–10667. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.10662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Therrien M, Chang H C, Solomon N M, Karim F D, Wassarman D A, Rubin G M. KSR, a novel protein kinase required for RAS signal transduction. Cell. 1995;83:879–888. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90204-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Therrien M, Michaud N R, Rubin G M, Morrison D K. KSR modulates signal propagation within the MAPK cascade. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2684–2695. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.21.2684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Thomas U, Jönsson F, Speicher S A, Knust E. Phenotypic and molecular characterization of SerD, a dominant allele of the Drosophila gene Serrate. Genetics. 1995;139:203–213. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.1.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Török T, Tick G, Alvarado M, Kiss I. P-lacW insertional mutagenesis on the second chromosome of Drosophila melanogaster: isolation of lethals with different overgrowth phenotypes. Genetics. 1993;135:71–80. doi: 10.1093/genetics/135.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tsuda L, Inoue Y H, Yoo M-A, Mizuno M, Hata M, Lim Y-M, Adachi-Yamada T, Ryo H, Masamune Y, Nishida Y. A protein kinase similar to MAP kinase activator acts downstream of the raf kinase in Drosophila. Cell. 1993;72:407–414. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90117-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.van Echten-Deckert G, Zschoche A, Bar T, Schmidt R R, Raths A, Heinemann T, Sandhoff K. cis-4-Methylsphingosine decreases sphingolipid biosynthesis by specifically interfering with serine palmitoyltransferase activity in primary cultured neurons. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:15825–15833. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.25.15825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Verheij M, Bose R, Lin X H, Yao B, Jarvis W D, Grant S, Birrer M J, Szabo E, Zon L I, Kyriakis J M, Haimovitz-Friedman A, Fuks Z, Kolesnick R N. Requirement for ceramide-initiated SAPK/JNK signalling in stress-induced apoptosis. Nature. 1996;380:75–79. doi: 10.1038/380075a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Weiss B, Stoffel W. Human and murine serine-palmitoyl-CoA transferase—cloning, expression and characterization of the key enzyme in sphingolipid synthesis. Eur J Biochem. 1997;249:239–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.White K, Grether M E, Abraham J M, Young L, Farrell K, Steller H. Genetic control of programmed cell death in Drosophila. Science. 1994;264:677–683. doi: 10.1126/science.8171319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Williams J A, Paddock S W, Carroll S B. Pattern formation in a secondary field: a hierarchy of regulatory genes subdivides the developing Drosophila wing disc into discrete subregions. Development. 1993;117:571–584. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.2.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wojnowski L, Zimmer A M, Beck T W, Hahn H, Bernal R, Rapp U R, Zimmer A. Endothelial apoptosis in Braf-deficient mice. Nat Genet. 1997;16:293–297. doi: 10.1038/ng0797-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wolff T, Ready D F. Cell death in normal and rough eye mutants of Drosophila. Development. 1991;113:825–839. doi: 10.1242/dev.113.3.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]