Abstract

Artificial intelligence and machine learning in orthopaedic surgery has gained mass interest over the last decade or so. In prior studies, researchers have demonstrated that machine learning in orthopaedics can be used for different applications such as fracture detection, bone tumor diagnosis, detecting hip implant mechanical loosening, and grading osteoarthritis. As time goes on, the utility of artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms, such as deep learning, continues to grow and expand in orthopaedic surgery. The purpose of this review is to provide an understanding of the concepts of machine learning and a background of current and future orthopaedic applications of machine learning in risk assessment, outcomes assessment, imaging, and basic science fields. In most cases, machine learning has proven to be just as effective, if not more effective, than prior methods such as logistic regression in assessment and prediction. With the help of deep learning algorithms, such as artificial neural networks and convolutional neural networks, artificial intelligence in orthopaedics has been able to improve diagnostic accuracy and speed, flag the most critical and urgent patients for immediate attention, reduce the amount of human error, reduce the strain on medical professionals, and improve care. Because machine learning has shown diagnostic and prognostic uses in orthopaedic surgery, physicians should continue to research these techniques and be trained to use these methods effectively in order to improve orthopaedic treatment.

Keywords: Artificial intelligence, Machine learning, Supervised learning, Unsupervised learning, Deep learning, Orthopaedic surgery

Core Tip: With the mass interest artificial intelligence and machine learning have garnered in orthopaedic surgery, a literature review of recent studies is necessary. By demonstrating the utility of various machine learning algorithms across various subspecialties of orthopaedic surgery, researchers should encourage physicians to understand the benefits of machine learning techniques and learn how to effectively incorporate these elements into their own practice to improve patient care. This clinical review outlines the concepts of machine learning and summarizes current and future orthopaedic applications of machine learning in risk assessment, outcomes assessment, imaging, and basic science fields.

INTRODUCTION

The application of artificial intelligence (AI) has taken our world by storm. AI has been used in many aspects of modern life such as recommendation systems used by Netflix, YouTube, and Spotify, search engines like Google, and social-media feeds like Facebook and Twitter[1]. Additionally, AI has entered the realm of medicine. For example, there is substantial evidence that AI performs on par or better than humans in various tasks such as analyzing medical images as well as correlating symptoms and biomarkers from electronic medical records with the characterization and prognosis of disease[2]. Specifically in orthopaedic surgery, certain subfields of AI have been successfully implemented to improve clinical decision making and patient care[3].

To better understand the utility of AI in orthopaedic surgery, some terms must first be defined. AI started as a theory that computers could eventually learn to perform tasks through pattern recognition with minimal to no human involvement[1,4]. Today, the definition has been adapted to include the application of algorithms that provide machines the ability to solve problems that traditionally required human intelligence[1,5]. AI, which is often used as an umbrella term, encompasses subfields such as machine learning (ML), which is defined as a series of mathematical algorithms that enable the machine to “learn” the relationship between the input and output data without being explicitly told how to do so[3]. Furthermore, machine learning contains the subfield of deep learning (DL) which can be used to find correlations without labelling, that are too complex to render using previous machine learning algorithms, by processing input data through artificial neural networks[6,7].

In the field of orthopaedic surgery, ML has been used for different applications such as fracture detection, bone tumor diagnosis, detecting hip implant mechanical loosening, and grading osteoarthritis (OA)[3]. As time goes on, the utility of AI and ML in orthopaedic surgery continues to grow and expand. The purpose of this review is to provide an understanding of the concepts of ML and a background of current and future orthopaedic applications of ML in risk assessment, outcomes assessment, imaging, and basic science fields.

WHAT IS ML?

ML focuses on developing automated computer systems that predict outputs through algorithms and mathematics[8,9]. Classic or conventional ML algorithms that are meant to extract knowledge from more tabulated data sets include decision trees, random forests, nearest neighbors, linear regression, support vector machine (SVM), and k-means clustering[3,10]. On the other hand, more recently developed DL algorithms and artificial neural networks (ANN) are used to extract knowledge from imaging data sets. Regardless of which algorithms are used, ML requires software to “learn” patterns or relationships from sets of empirical data. This “learning” can be achieved through three different means: supervised learning, unsupervised learning, and reinforcement learning[11-13].

Types of ML

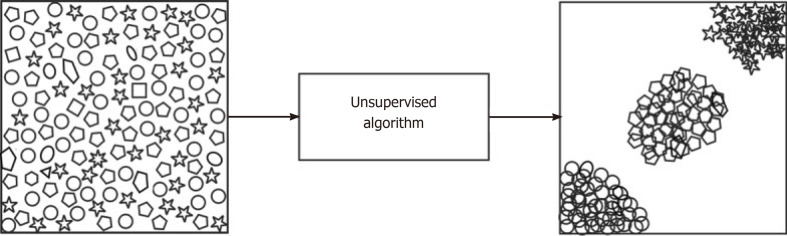

Supervised learning, also termed inductive learning, is the most prevalent type of ML and occurs when data is labeled to tell the machine exactly what patterns it should look for[14]. For example, if an ML algorithm is used to detect arthritis on a knee radiograph, the arthritic features must be manually identified and labeled by a human along with the label of whether the radiograph is an example of an arthritic or normal knee[1]. On the other hand, unsupervised learning, also termed deductive or analytic learning, occurs when the data is not labeled and the machine looks for patterns[14] (Figure 1). In continuing with the last example, the arthritic features in unsupervised learning would not be labeled and therefore the algorithm relies on self-organization[1]. Lastly, reinforcement learning acts more like a reward or punishment system. Unlike supervised learning which makes data available at the beginning of the task, reinforcement learning uses feedback about the correctness after the task has been completed[15]. Usually, supervised learning is used because it requires the least amount of data and thus the least amount of time to learn.

Figure 1.

A visual illustration of an unsupervised algorithm[11]. Reused with permission. Citation: Sidey-Gibbons JAM, Sidey-Gibbons CJ. Machine learning in medicine: a practical introduction. BMC Med Res Methodol 2019; 19: 64.

DL and ANN

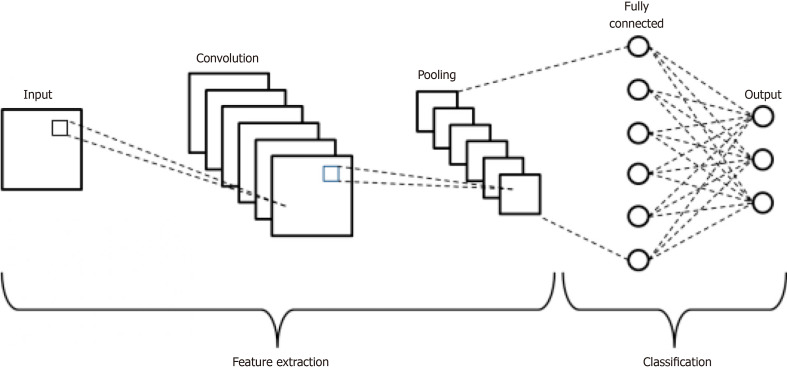

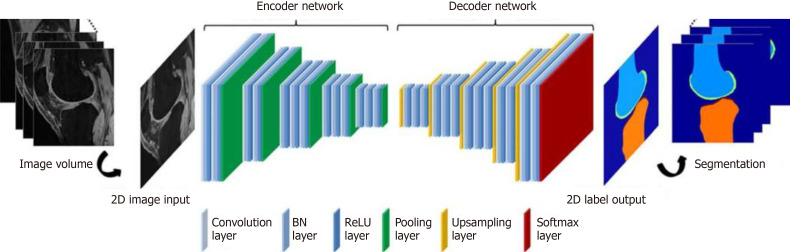

DL is modeled after the human brain’s neural connections via complex and layered algorithms termed ANN[1,14]. The complex layering allows the algorithm to learn more complex and subtle patterns compared to more simple one or two layer networks[5,16,17]. Two known models of deep learning within the ANN include convolutional neural network (CNN) and recurrent neural network. The main type, CNN, has two main functions: (1) to extract features from imaging; and (2) classification[3]. The CNN extraction feature relies on the idea that filters learned on a small subset of a larger image to detect certain features can also be applied to other parts of the larger image in order to detect the same feature at different locations[3]. The CNN starts by searching for simple features in an image and then pools these simple features together to extract more complicated high-level features[3,18] (Figure 2). For the classification feature, the CNN acts as a classic neural network that combines all the high-level feature maps (generated from the aforementioned filters) from the deepest convolution layer and uses them to output a classification score[3]. During training, the CNN is presented with a series of images that have known classifications; the CNN must make a classification decision for each image and then calculate the classification error by comparing its classification decision with the known classification of the image. Through this training process, the CNN is able to update its learnable parameters and make classification decisions on images never before seen[3].

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of a basic convolutional neural network architecture[18]. Reused with permission. Citation: Phung VH, Rhee EJ. A High-Accuracy Model Average Ensemble of Convolutional Neural Networks for Classification of Cloud Image Patches on Small Datasets. App Sci 2019; 9: 4500.

DL algorithms have been successfully applied to complex problems to improve diagnostic accuracy and speed, flag the most critical and urgent patients for immediate attention, reduce the amount of human error, reduce the strain on medical professionals, and improve orthopaedic care[3]. Specifically in orthopaedic surgery, the greatest application of DL is in image classification.

RISK ASSESSMENT

While ML has traditionally been used in medicine for rule-based approaches such as safe drug prescription, recent use of ML and DL in orthopaedic surgery has focused on clinical decision support such as risk assessment[14,19]. Currently, logistic regression is one of the most commonly used methods for identifying risk factors predictive of developing complications; however, in comparison, ANN allows for the identification of nonlinear patterns that make predictions more accurate[20-22].

Throughout orthopaedic literature, the application of ML and DL in risk assessment for various complications has been studied extensively (Table 1). For example, in Kim et al[23], ML models were used to predict mortality, venous thromboembolism, cardiac complications, and wound complications following posterior lumbar fusion. The ML models outperformed the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) scores proving that ML can be more effective at predicting complications. Similarly, in Harris et al[24], ML was used to predict 30 day mortality and morbidity after total joint arthroplasty. While the ML model was found to be more accurate than standard models for cardiac complications and mortality, it was less effective for rarer complications such as re-operation and deep infection. More recently, Gowd et al[25] used supervised ML models to predict postoperative outcomes following total shoulder arthroplasty. ML algorithms outperformed the standard model for predicting adverse events, transfusion, extended length of stay, surgical site infection, return to the operating room, and readmission. Furthermore, in risk assessment related to orthopaedic trauma, Bevevino et al[26] used a DL model to predict the likelihood of amputation based on 155 combat-related open calcaneal fractures and compared it to a standard logistical regression model. Twenty-six features with a proven or theoretical association with successful or unsuccessful limb salvage were analyzed; some of the features included were various patient demographics, mechanism of injury, wound size and location, and fracture type. Once again, the DL method was 30% more accurate and better suited to clinical use than the standard logistical regression model.

Table 1.

Summary of machine learning for orthopaedic surgery risk assessment

|

Ref.

|

Conclusion

|

| Bevevino et al[26] | ANN capable of accurately estimating the likelihood of amputation |

| Gowd et al[25] | Supervised ML outperformed ASA classification models in predicting adverse events, transfusion, extended length of stay, surgical site infection, return to operating room, and readmission |

| Harris et al[24] | ML was moderately accurate in predicting 30-d mortality and cardiac complications after elective primary TJA |

| Kim et al[23] | ANN more accurate than ASA in predicting mortality, VTE, cardiac and wound complications following posterior lumbar spine fusion |

ML: Machine learning; ANN: Artificial neural network; ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; TJA: Total joint arthroplasty; VTE: Venous thromboembolism.

The orthopaedic literature shows that ML continuously outperforms more traditional legacy risk-stratification measures such as ASA classification, Charlson Comorbidity Index, and modified 5-item frailty index, in predicting complications following a variety of orthopaedic procedures as well as identifying safe candidates for specific orthopaedic procedures like anterior cervical fusion and discectomy[25,27-29]. In all of the studies outlined above, the ML and DL algorithms outperformed the standard models indicating a higher level of accuracy for risk assessment[23-26]. Furthermore, comorbidity indices have previously been used to gauge perioperative risk, evaluate the need for postoperative admission, and determine prophylactic treatments[30-32]. With continued validation, ML algorithms may replace this paradigm. Whereas logistical regression models have typically been used for many years to predict risk, survival, mortality, and morbidity, the application of ML and DL, particularly in predicting the risk of complications following spine surgeries, joint surgeries, and orthopaedic trauma, shows much promise[14].

OUTCOMES ASSESSMENT

Over the last twenty years or so, the ability to predict outcomes has positively impacted medicine and patient care. From risk scores that guide anticoagulation (CHADS2) to the use of cholesterol medications (ASCVD), data-driven clinical predictions have become routine in medical practice[33]. Because ML has the ability to analyze large data sets, the accuracy of prediction significantly improves[33]. Specifically in orthopaedic surgery, recent literature has shown the utility of ML algorithms in outcomes assessment for orthopaedic oncology survival, patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), hospital length of stay, and cost (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of machine learning for orthopaedic surgery outcomes assessment

|

Ref.

|

Conclusion

|

| Bongers et al[40] | ML algorithm overestimated ability to predict 5-year survival in patients with chondrosarcoma |

| Fontana et al[41] | Used ML to demonstrate fair-to-good ability in predicting 2-year postsurgical MCID following TJA |

| Greenstein et al[51] | Used EMR-integrated ANN to predict discharge disposition after TJA on small data set |

| Janssen et al[38] | Boosting ML algorithm far superior in training data sets to classic scoring system and nomogram in predicting survival in patients with long bone metastases at 30 days, 90 days, and 1 year |

| Karnuta et al[50] | Bayes ML algorithm demonstrated excellent accuracy in prediction of length of stay and cost of an episode of care for hip fracture |

| Menendez et al[44] | Used ML on patient-narrative analysis to show patient satisfaction after TSA is linked to hospital environment, nontechnical skills, and delays |

| Navarro et al[46] | Created a valid ML algorithm that predicted length of stay and costs before primary TKA |

| Pereira et al[55] | Boosting ML algorithm comparable to nomogram in its ability to predict survival in metastatic spine disease with testing data sets |

| Ramkumar et al[45] | Created a valid and reliable ML algorithm that predicted length of stay and payment prior to primary THA |

| Ramkumar et al[47] | Developed several ML based models for primary LEA that preoperatively predict cost, length of stay, and discharge disposition |

| Thio et al[39] | Created a high performing ML algorithm that could predict 5-year survival in patients with chondrosarcoma |

ML: Machine learning; MCID: Minimally clinically important difference; TJA: Total joint arthroplasty; EMR: Electronic medical record; ANN: Artificial neural network; TSA: Total shoulder arthroplasty; TKA: Total knee arthroplasty; THA: Total hip arthroplasty; LEA: Lower extremity arthroplasty.

When compared to ML algorithms, current prognostication models for survival following metastatic spinal disease are not built for estimation of short-term survival (30 to 90 d) and some studies even suggest a lack of accuracy in classic models[34-37]. In Janssen et al[38], authors compared a boosting ML algorithm to a classic scoring system and nomogram at 30 d, 90 d, and 1 year to study survival estimates in patients with long bone metastases. In all training data sets, the boosting ML algorithm was found to be far superior at each time point[38]. Paulino Pereira et al[37] conducted a similar study where they compared the boosting ML algorithm, nomogram, and the classic scoring system to predict survival in metastatic spine disease. In this study, the boosting ML algorithm was comparable to nomogram in its predictive ability for testing data sets. Thio et al[39] and Bongers et al[40] used ML methods on patient demographics, tumor characteristics, treatment, and outcome data to create an ML algorithm that could predict 5 year survival rate in patients with chondrosarcoma[39,40]. In the latter study, the authors found that the ML algorithm overestimated the survival rate in their data set, but when applied to a smaller data set, it overestimated survival to a lesser extent.

Within the last ten years, the concept of PROMs has gained rapid support in orthopaedic surgery as a way to measure healthcare quality and value[41]. The minimally clinically important difference (MCID) or the minimum change in PROM scores that patients perceive as clinically meaningful offers a threshold of score that portends clinical relevance[41-43]. Using predictive models to identify patients at risk of not achieving MCID is important for resource allocation as well as better monitoring especially for presurgical decision support[41]. Fontana et al[41] used three ML models to predict which patients would not achieve a MCID in four PROMs two years following total joint arthroplasty (TJA). When applied to presurgical registry data, the three ML models predicted 2-year postsurgical MCIDs with fair-to-good ability showing that ML has good predictive power in MCID following TJA. In another study, Menendez et al[44] used ML to understand sentiment by exploring the content of negative patient-experience comments after total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA). Through a ML based approach, they found that patient satisfaction was highly correlated to hospital environment, nontechnical skills, and delays. Menendez et al[44] showed the potential utility of AI and ML models to analyze post-surgical PROM surveys to determine quality and satisfaction after TSA.

A newer trend in orthopaedic surgery is using ML concepts to predict hospital length of stay as well as cost[45-47]. Today, ML models can be used to predict how long or how much a patient’s surgery will cost prior to the elective procedure[48,49]. Ramkumar et al[45,47] and Navarro et al[46] used ML techniques on preoperative big data to predict length of stay and patient-specific payments following total hip arthroplasty (THA) and total knee arthroplasty (TKA), respectively[45-47]. In both studies, the ML techniques showed excellent predictability in length of stay. As complexity of the case increased, accuracy for predicting payment decreased proportionately in THA. On the other hand, as complexity of the case increased in TKA, accuracy for predicting costs increased by 3%, 10%, and 15% for moderate, severe, and extreme risk populations[46]. Similarly, Karnuta et al[50] used an ML algorithm on preoperative patient data to predict length of stay and cost after hip fracture; they found their ML algorithm to be 76.5% accurate for predicting length of stay and 79% accurate for predicting cost. Furthermore, Greenstein et al[51] used ML to preoperatively predict the likelihood a patient will be discharged to a skilled nursing facility after TJA. This study served as proof of concept that ML could be used as a prediction tool not only for big data sets, but also for small data sets. Using ML techniques to predict length of stay and cost has led to monumental improvements in establishing value-based care in orthopaedic surgery.

In orthopaedic surgery, AI and ML based techniques have demonstrated utility in predicting outcomes related to orthopaedic oncology, PROMs, length of stay, and cost. While ML techniques for survival in orthopaedic oncology have not yet been perfected, ML has proven to be effective with PROMs as well as predicting length of stay and cost. By using ML methods to make better outcome predictions, orthopaedic surgeons can improve their decision-making ability, which not only leads to better patient care, but also more efficient utilization of healthcare resources[52].

IMAGING

Since orthopaedic surgery diagnosis and treatment heavily rely on radiologic modalities [e.g., computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and conventional radiographs], the vast majority of AI and ML based research has been applied to imaging. Recent advances in AI and ML have shown remarkable results with a few studies showing computers surpassing human test subjects at certain image interpretation tasks[53,54]. Within musculoskeletal medicine, DL has been shown to be useful for both text and image analysis[55-57]. ML and DL based techniques have the potential to assess earlier disease status and are currently the focus of significant orthopaedic research, particularly in the following subspecialties: Spine, joints/ arthritis, trauma, and oncology (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of machine learning for orthopaedic surgery imaging applications

|

Ref.

|

Subspecialty

|

Conclusion

|

| Al-Helo et al[66] | Spine | Neural network (93.2% accurate) and k-means approach (98% accurate) used on CT scans for segmentation and prediction of lumbar wedge fractures |

| Forsberg et al[62] | Spine | Annotated MRIs with information labels for each spine vertebrae used to accurately detect (99.8%) and label (97%) cervical and lumbar vertebrae |

| Hetherington et al[64] | Spine | CNN successfully identified lumbar vertebral levels on ultrasound images of the sacrum |

| Jamaludin et al[65] | Spine | CNN model achieved 95.6% accuracy comparable to experienced radiologists in disc detection and labeling of T2 weighted sagittal lumbar MRIs |

| Pesteie et al[63] | Spine | Used ML system to detect laminae and facet joints in ultrasound images to assist in epidural steroid injection and facet joint injection administration |

| Ashinsky et al[71] | Joints/arthritis | ML algorithm predicted clinically symptomatic OA on T2 weighted maps of central medial femoral condyle with 75% accuracy |

| Liu et al[72] | Joints/arthritis | CNN performed rapid and accurate cartilage and bone segmentation within the knee joint |

| Shah et al[73] | Joints/arthritis | CNN used to automate the segmentation and measurement of cartilage thickness based on MRIs of healthy knees |

| Xue et al[70] | Joints/arthritis | CNN model trained to diagnose hip OA comparable to an attending physician with 10 years of experience in diagnosing hip OA |

| Kruse et al[75] | Trauma | ML improved hip fracture detection beyond logistic regression using dual x-ray absorptiometry |

| Olczak et al[74] | Trauma | DL networks identified fracture, laterality, body part, and exam view on orthopaedic trauma radiographs of the hand, wrist, and ankle |

| Oh et al[78] | Oncology | ML showed superior predictive accuracy in predicting pathological femoral fractures in metastatic lung cancer |

ML: Machine learning; CNN: Convolutional neural network; OA: Osteoarthritis.

Spine

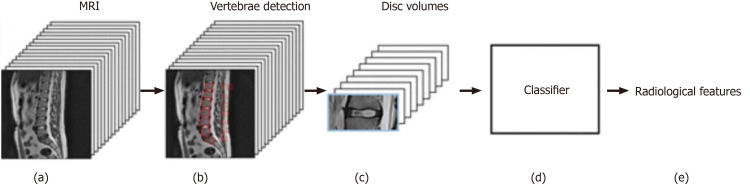

In spine surgery, technology has risen with the use of computer assisted navigation, robotic surgery, and augmented reality, all of which require reconstructions of the spinal column from CT or MRI scans[58-61]. This can only be achieved via ANNs and DL through automated segmentation and detection of vertebrae. Numerous studies in the orthopaedic spine literature have analyzed the accuracy of DL techniques, especially for labeling and detection. For example, in Forsberg et al[62], annotated MRIs with information labels for each spine vertebrae were used to detect and label cervical and lumbar vertebrae. The highest performance showed an accuracy of 99.8% for detection and 97% for labeling. Furthermore, Pesteie et al[63] and Hetherington et al[64] used ANNs trained with ultrasound images to automatically detect optimal vertebra level and injection plane for percutaneous spinal needle injections; Pesteie et al[63] showed highest accuracy to be 95% and maximum precision to be 97%. ML and DL techniques have been shown to be useful in diagnosis as well. Jamaludin et al[65] used DL techniques to read T2 weighted sagittal lumbar MRI images, automate the identification of disc spaces, grade the degenerative changes such as spondylolisthesis and central canal stenosis, and compare them to what experienced radiologists would do (Figure 3). The DL model performed almost as well as experienced radiologists on test data with a best accuracy rate of 95% for the prediction of spondylolisthesis. Because this model did not require labeling and feature description, authors believe the model will gain more accuracy and reliability with the addition of coronal and axial views. Al-Helo et al[66] used ML techniques, specifically neural network and k-means approach, to learn lumbar wedge fracture diagnoses from CT image labeling for segmentation and prediction. The neural network showed an accuracy of 93.2% for lumbar fracture detection, while the k-means clustering approach attained an accuracy of 98%. These studies prove that the automation of radiologic grading is now on par with human performance; this can be incredibly beneficial in aiding clinical diagnoses in terms of grading and speed of analysis.

Figure 3.

Input processing pipeline of T2 sagittal magnetic resonance imaging and output predictions of radiological features[65]. Reused with permission. Citation: Jamaludin A, Lootus M, Kadir T, Zisserman A, Urban J, Battié MC, Fairbank J, McCall I; Genodisc Consortium. ISSLS PRIZE IN BIOENGINEERING SCIENCE 2017: Automation of reading of radiological features from magnetic resonance images (MRIs) of the lumbar spine without human intervention is comparable with an expert radiologist. Eur Spine J 2017; 26: 1374-1383.

Joints/arthritis

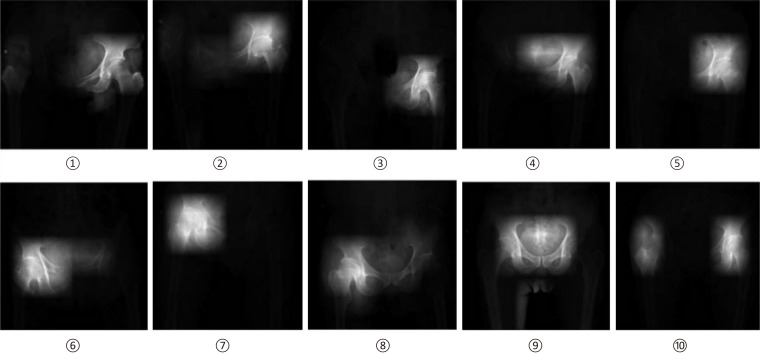

OA, a highly prevalent disease associated with articular cartilage degeneration, can be effectively diagnosed in a cost-effective manner with X-ray imaging and in a more sensitive manner with MRI which can detect subtle morphologic changes in articular cartilage[67-69]. Throughout orthopaedic literature, DL has been used for hip and knee diagnostic purposes based on medical images. For the hip, Xue et al[70] trained a CNN with 420 hip X-ray images to highlight saliency regions. These saliency regions allow the deep learning model to extract the necessary information in order to diagnose hip OA (Figure 4). The CNN model was able to achieve an accuracy of 92.8%, comparable to an attending physician with ten years of experience in diagnosing hip OA. For the knee, Ashinsky et al[71] used a ML algorithm on T2 weighted maps of the central medial femoral condyle in order to predict progression to clinically symptomatic OA; the ML algorithm was able to predict the onset of OA with 75% accuracy. Liu et al[72] applied a CNN to a knee image data set for bone and cartilage segmentation and labeling (Figure 5). Authors reported a performance accuracy of 75.3% for femoral cartilage labeling and 78.1% for patellar cartilage labeling. Similar to Liu et al[72], Shah et al[73] used a CNN to successfully automate cartilage segmentation methods and measurement of articular cartilage thickness. This study showed that ML can be used to analyze cartilage thickness in an automated and efficient manner. The results of the studies summarized above indicate that DL has promising potential in the field of intelligent medical image diagnosis practice, especially for hip and knee OA.

Figure 4.

Saliency images from left hip joint (1-5), right hip joint (6-8), and both hip joints (9,10)[70]. Reused with permission. Citation: Xue Y, Zhang R, Deng Y, Chen K, Jiang T. A preliminary examination of the diagnostic value of deep learning in hip osteoarthritis. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0178992.

Figure 5.

Convolutional neural network depiction of a knee image data set for bone and cartilage segmentation and labeling[72]. Reused with permission. Citation: Liu F, Zhou Z, Jang H, Samsonov A, Zhao G, Kijowski R. Deep convolutional neural network and 3D deformable approach for tissue segmentation in musculoskeletal magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Med 2018; 79: 2379-2391.

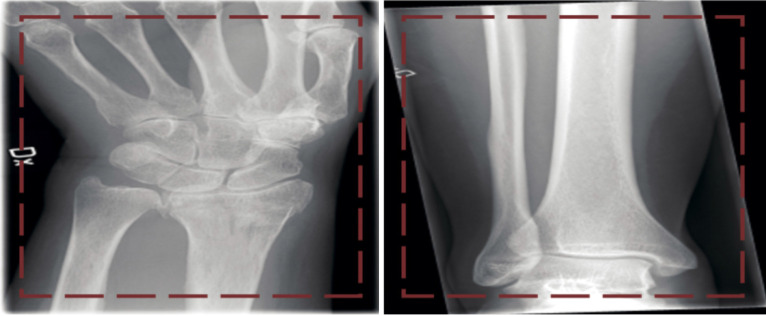

Trauma

For orthopaedic trauma, ML derived tools can be used on imaging techniques to assist in diagnostic ability, particularly for detection of fractures. Olczak et al[74] applied ML to 256000 orthopaedic trauma radiographs with good results compared to radiologists. In this study, a database of hand, wrist, and ankle radiographs were used and four outcomes - laterality, exam view, fracture, and body part - were identified (Figure 6). Five DL networks were used and reached 99% accuracy when identifying body part, 90% on laterality, 95% on exam view, and 83% on detecting fractures[74]. Furthermore, Kruse et al[75] used ML to predict hip fractures from dual x-ray absorptiometry; they found that ML could improve hip fracture prediction beyond logistic regression. In orthopaedic trauma, ML based techniques have immense utility in predicting fractures. AI and ML based methods could be beneficial in the future of orthopaedic trauma as they may enhance workflow in the emergency department[76].

Figure 6.

Two images (left, wrist fracture; right, no fracture) from the dataset presented to the network[74]. Reused with permission. Citation: Olczak J, Fahlberg N, Maki A, Razavian AS, Jilert A, Stark A, Sköldenberg O, Gordon M. Artificial intelligence for analyzing orthopedic trauma radiographs. Acta Orthop 2017; 88: 581-586.

Oncology

In orthopaedic oncology, management of metastatic bone disease is a major focus, especially with respect to fracture and impending fracture care[77]. Oh et al[78] used ML on CT imaging and clinical features to extract radiologic features and derive predictions for pathological femoral fractures in metastatic lung cancer and compared the ML model with one that used CT features alone. The ML model, which included clinical features, showed superior predictive accuracy compared to the model that used CT features alone. By using AI and ML to accurately predict impending skeletal-related events, such as pathologic fracture, orthopaedic surgeons can prophylactically treat patients and thus improve patient outcomes[77].

BASIC SCIENCE APPLICATIONS

In the past, ML has been applied to basic science topics in medicine to predict chemical properties of drugs and proteins, predict vaccine immunogenicity, and identify promising drug targets[79-82]. In orthopaedic surgery, AI and ML has been applied to more translational basic science concepts such as kinetics and gait analysis, wearable technology, and implant design[83-86] (Table 4).

Table 4.

Summary of machine learning for orthopaedic surgery basic science applications

|

Ref.

|

Application

|

Conclusion

|

| Begg et al[83] | Gait analysis | Used SVM to automate recognition of gait changes due to aging |

| Joyseeree et al[84] | Gait analysis | Used random forest, boosting, and SVM to identify disease on gait analysis data |

| Sikka et al[85] | Wearable technology | Utilized ML analytics via wearable technology to improve sports performance and identify risk factors for injury in sports |

| Cilla et al[86] | Implant design | ML techniques used to optimize short stem hip prosthesis to reduce stress shielding effects and achieve better short-stemmed implant performance |

ML: Machine learning; SVM: Support vector machine.

It is well established in orthopaedic literature that aging influences various gait measures, such as gait velocity, stride length, and stance and swing phase times[87]. By applying ML to automate recognition of gait pattern changes, researchers can identify key variables of gait degeneration that might be predictors of falling behavior. Begg et al[83] used SVM, a specific ML approach, to automate recognition of gait changes due to aging using three types of gait measures: basic temporal/spatial, kinetic, and kinematic. When comparing gaits of twelve young participants to twelve elderly participants, the ML technique showed an overall accuracy of 91.7%. Furthermore, gait recognition improved when features were selected from different gait data types with an effective potential of 100% accuracy. Similarly, Joyseeree et al[84] applied ML algorithms, specifically random forest, boosting, and SVM, to gait analysis data for disease identification. Following a training and testing period, random forest and SVM had an accuracy of 100%, while boosting had an accuracy of 96.4%.

Another basic science application where ML has shown great promise is wearable technology. With the increase in wearable and portable technology, the general public as well as professional athletes have the power to monitor basic human physical and physiologic function that can combine with health records for analysis. Sikka et al used ML analytics via wearable technology such as camera-based monitoring systems, heart rate monitoring devices, radio-frequency identification tracking systems, and accelerometers, to improve sports performance[85]. Additionally, the data collected can be used to identify risk factors for injury in sports and therefore can proactively prevent injuries and direct injury prevention programs[85]. In the future, healthcare providers could utilize this information not only to develop optimal training programs for elite athletes while minimizing risk of injury and loss of play time, but also to create more cost-efficient care that is individually tailored for the average patient.

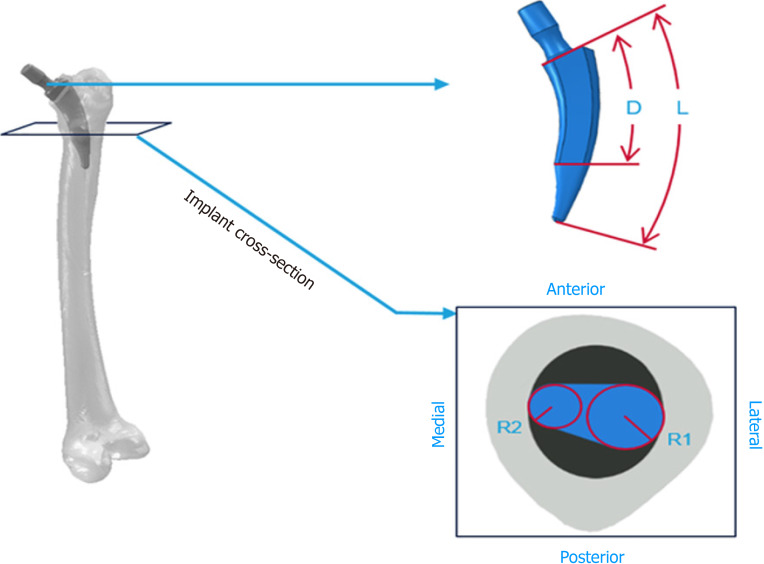

While shape optimization algorithms, which are different from ML, have previously been used to assess stem performance, the potential to further optimize short stem implants using ML has only recently been addressed[88-91]. For example, Cilla et al[86] used ANNs and SVMs to analyze four parameters with the end goal being to optimize short stem implant design, specifically for THA, to produce optimal performance, lack of bone resorption, and reduced stress shielding (Figure 7). They found that implants should be designed with a small stem length and a reduced length of the surface in contact with the bone to reduce stress shielding. The optimization approach using ML techniques can offer new and innovative possibilities in the design of hip implants and more. These analyses can be used to design new prostheses as well as aid orthopaedic surgeons in decision-making when choosing the most adequate implant.

Figure 7.

Graphic representation of the four parameters (L, total stem length; R1, radial circumference in the lateral side; R2, radial circumference in the medial; D, distance between the implant neck and the central stem surface)[86]. Reused with permission. Citation: Cilla M, Borgiani E, Martínez J, Duda GN, Checa S. Machine learning techniques for the optimization of joint replacements: Application to a short-stem hip implant. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0183755.

CONCLUSION

In recent years, ML has garnered interest across various medical specialties and has proven its utility in orthopaedic surgery. Some studies even show that developed and validated ML models are capable of outperforming human specialists. Similarly, in orthopaedic surgery, ML has been incredibly useful in spine pathology detection, prosthesis control, gait classification, OA detection, and fracture detection. These results corroborate the information that computers can outperform physicians in numerous tasks, even in orthopaedics. By and large, ML has diagnostic and prognostic uses that with continued research can offer more implications regarding orthopaedic treatment. With its surging trend of interest, AI and ML is expected to see an increase in use with risk assessment, outcomes assessment, imaging, and basic science applications in orthopaedics. Furthermore, because ML provides physicians the unique opportunity to understand their patients better, physicians should be trained to use these methods effectively in order to improve orthopaedic patient care.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: All authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Peer-review started: March 17, 2021

First decision: May 3, 2021

Article in press: August 5, 2021

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Anysz H S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xing YX

Contributor Information

Simon P Lalehzarian, The Chicago Medical School, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, North Chicago, IL 60064, United States.

Anirudh K Gowd, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center, Winston-Salem, NC 27157, United States.

Joseph N Liu, USC Epstein Family Center for Sports Medicine, Keck Medicine of USC, Los Angeles, CA 90033, United States. joseph.liu@med.usc.edu.

References

- 1.Myers TG, Ramkumar PN, Ricciardi BF, Urish KL, Kipper J, Ketonis C. Artificial Intelligence and Orthopaedics: An Introduction for Clinicians. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2020;102:830–840. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.19.01128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller DD, Brown EW. Artificial Intelligence in Medical Practice: The Question to the Answer? Am J Med. 2018;131:129–133. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borjali A, Chen AF, Muratoglu OK, Morid MA, Varadarajan KM. Deep Learning in Orthopedics: How Do We Build Trust in the Machine? Healthcare Transformat . 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Topol E. Deep Medicine: How Artificial Intelligence Can Make Healthcare Human Again. Basic Books, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hashimoto DA, Rosman G, Rus D, Meireles OR. Artificial Intelligence in Surgery: Promises and Perils. Ann Surg. 2018;268:70–76. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park CW, Seo SW, Kang N, Ko B, Choi BW, Park CM, Chang DK, Kim H, Lee H, Jang J, Ye JC, Jeon JH, Seo JB, Kim KJ, Jung KH, Kim N, Paek S, Shin SY, Yoo S, Choi YS, Kim Y, Yoon HJ. Artificial Intelligence in Health Care: Current Applications and Issues. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35:e379. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bohr A, Memarzadeh K. Chapter 2: The rise of artificial intelligence in healthcare applications. In: Bohr A, Memarzadeh K, editors. Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare. Academic Press, 2020: 25-60. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jordan MI, Mitchell TM. Machine learning: Trends, perspectives, and prospects. Science. 2015;349:255–260. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa8415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang M, Canseco JA, Nicholson KJ, Patel N, Vaccaro AR. The Role of Machine Learning in Spine Surgery: The Future Is Now. Front Surg. 2020;7:54. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2020.00054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cabitza F, Locoro A, Banfi G. Machine Learning in Orthopedics: A Literature Review. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2018;6:75. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2018.00075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sidey-Gibbons JAM, Sidey-Gibbons CJ. Machine learning in medicine: a practical introduction. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019;19:64. doi: 10.1186/s12874-019-0681-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hao K. What is machine learning? MIT Technology Review. November 17, 2018. Available from: https://www.technologyreview.com/2018/11/17/103781/what-is-machine-learning-we-drew-you-another-flowchart/

- 13.Brownlee J. Basic Concepts in Machine Learning. Machine Learning Mastery. December 15, 2015. Available from: https://machinelearningmastery.com/basic-concepts-in-machine-learning/

- 14.Poduval M, Ghose A, Manchanda S, Bagaria V, Sinha A. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning: A New Disruptive Force in Orthopaedics. Indian J Orthop. 2020;54:109–122. doi: 10.1007/s43465-019-00023-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galbusera F, Casaroli G, Bassani T. Artificial intelligence and machine learning in spine research. JOR Spine. 2019;2:e1044. doi: 10.1002/jsp2.1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shi L, Wang XC, Wang YS. Artificial neural network models for predicting 1-year mortality in elderly patients with intertrochanteric fractures in China. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2013;46:993–999. doi: 10.1590/1414-431X20132948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramkumar PN, Karnuta JM, Navarro SM, Haeberle HS, Iorio R, Mont MA, Patterson BM, Krebs VE. Preoperative Prediction of Value Metrics and a Patient-Specific Payment Model for Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty: Development and Validation of a Deep Learning Model. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34:2228–2234.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2019.04.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phung VH, Rhee EJ. A High-Accuracy Model Average Ensemble of Convolutional Neural Networks for Classification of Cloud Image Patches on Small Datasets. App Sci . 2019;9:4500. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Challen R, Denny J, Pitt M, Gompels L, Edwards T, Tsaneva-Atanasova K. Artificial intelligence, bias and clinical safety. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019;28:231–237. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2018-008370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Di Capua J, Somani S, Kim JS, Phan K, Lee NJ, Kothari P, Cho SK. Analysis of Risk Factors for Major Complications Following Elective Posterior Lumbar Fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2017;42:1347–1354. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000002090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee NJ, Kothari P, Phan K, Shin JI, Cutler HS, Lakomkin N, Leven DM, Guzman JZ, Cho SK. Incidence and Risk Factors for 30-Day Unplanned Readmissions After Elective Posterior Lumbar Fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2018;43:41–48. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dreiseitl S, Ohno-Machado L. Logistic regression and artificial neural network classification models: a methodology review. J Biomed Inform. 2002;35:352–359. doi: 10.1016/s1532-0464(03)00034-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim JS, Merrill RK, Arvind V, Kaji D, Pasik SD, Nwachukwu CC, Vargas L, Osman NS, Oermann EK, Caridi JM, Cho SK. Examining the Ability of Artificial Neural Networks Machine Learning Models to Accurately Predict Complications Following Posterior Lumbar Spine Fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2018;43:853–860. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000002442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris AHS, Kuo AC, Weng Y, Trickey AW, Bowe T, Giori NJ. Can Machine Learning Methods Produce Accurate and Easy-to-use Prediction Models of 30-day Complications and Mortality After Knee or Hip Arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2019;477:452–460. doi: 10.1097/CORR.0000000000000601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gowd AK, Agarwalla A, Amin NH, Romeo AA, Nicholson GP, Verma NN, Liu JN. Construct validation of machine learning in the prediction of short-term postoperative complications following total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2019;28:e410–e421. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2019.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bevevino AJ, Dickens JF, Potter BK, Dworak T, Gordon W, Forsberg JA. A model to predict limb salvage in severe combat-related open calcaneus fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:3002–3009. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3382-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kunze KN, Polce EM, Nwachukwu BU, Chahla J, Nho SJ. Development and Internal Validation of Supervised Machine Learning Algorithms for Predicting Clinically Significant Functional Improvement in a Mixed Population of Primary Hip Arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 2021;37:1488–1497. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2021.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kunze KN, Polce EM, Rasio J, Nho SJ. Machine Learning Algorithms Predict Clinically Significant Improvements in Satisfaction After Hip Arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 2021;37:1143–1151. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2020.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang KY, Suresh KV, Puvanesarajah V, Raad M, Margalit A, Jain A. Using Predictive Modeling and Machine Learning to Identify Patients Appropriate for Outpatient Anterior Cervical Fusion and Discectomy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2021;46:665–670. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000003865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marya SK, Amit P, Singh C. Impact of Charlson indices and comorbid conditions on complication risk in bilateral simultaneous total knee arthroplasty. Knee. 2016;23:955–959. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2016.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keener JD, Callaghan JJ, Goetz DD, Pederson DR, Sullivan PM, Johnston RC. Twenty-five-year results after Charnley total hip arthroplasty in patients less than fifty years old: a concise follow-up of a previous report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:1066–1072. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200306000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Voskuijl T, Hageman M, Ring D. Higher Charlson Comorbidity Index Scores are associated with readmission after orthopaedic surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:1638–1644. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3394-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen JH, Asch SM. Machine Learning and Prediction in Medicine - Beyond the Peak of Inflated Expectations. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:2507–2509. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1702071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leithner A, Radl R, Gruber G, Hochegger M, Leithner K, Welkerling H, Rehak P, Windhager R. Predictive value of seven preoperative prognostic scoring systems for spinal metastases. Eur Spine J. 2008;17:1488–1495. doi: 10.1007/s00586-008-0763-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zoccali C, Skoch J, Walter CM, Torabi M, Borgstrom M, Baaj AA. The Tokuhashi score: effectiveness and pitfalls. Eur Spine J. 2016;25:673–678. doi: 10.1007/s00586-015-4339-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van der Linden YM, Dijkstra SP, Vonk EJ, Marijnen CA, Leer JW Dutch Bone Metastasis Study Group. Prediction of survival in patients with metastases in the spinal column: results based on a randomized trial of radiotherapy. Cancer. 2005;103:320–328. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paulino Pereira NR, Janssen SJ, van Dijk E, Harris MB, Hornicek FJ, Ferrone ML, Schwab JH. Development of a Prognostic Survival Algorithm for Patients with Metastatic Spine Disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98:1767–1776. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.15.00975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Janssen SJ, van der Heijden AS, van Dijke M, Ready JE, Raskin KA, Ferrone ML, Hornicek FJ, Schwab JH. 2015 Marshall Urist Young Investigator Award: Prognostication in Patients With Long Bone Metastases: Does a Boosting Algorithm Improve Survival Estimates? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:3112–3121. doi: 10.1007/s11999-015-4446-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thio QCBS, Karhade AV, Ogink PT, Raskin KA, De Amorim Bernstein K, Lozano Calderon SA, Schwab JH. Can Machine-learning Techniques Be Used for 5-year Survival Prediction of Patients With Chondrosarcoma? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2018;476:2040–2048. doi: 10.1097/CORR.0000000000000433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bongers MER, Thio QCBS, Karhade AV, Stor ML, Raskin KA, Lozano Calderon SA, DeLaney TF, Ferrone ML, Schwab JH. Does the SORG Algorithm Predict 5-year Survival in Patients with Chondrosarcoma? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2019;477:2296–2303. doi: 10.1097/CORR.0000000000000748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fontana MA, Lyman S, Sarker GK, Padgett DE, MacLean CH. Can Machine Learning Algorithms Predict Which Patients Will Achieve Minimally Clinically Important Differences From Total Joint Arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2019;477:1267–1279. doi: 10.1097/CORR.0000000000000687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beard DJ, Harris K, Dawson J, Doll H, Murray DW, Carr AJ, Price AJ. Meaningful changes for the Oxford hip and knee scores after joint replacement surgery. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Keurentjes JC, Van Tol FR, Fiocco M, Schoones JW, Nelissen RG. Minimal clinically important differences in health-related quality of life after total hip or knee replacement: A systematic review. Bone Joint Res. 2012;1:71–77. doi: 10.1302/2046-3758.15.2000065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Menendez ME, Shaker J, Lawler SM, Ring D, Jawa A. Negative Patient-Experience Comments After Total Shoulder Arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2019;101:330–337. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.18.00695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ramkumar PN, Navarro SM, Haeberle HS, Karnuta JM, Mont MA, Iannotti JP, Patterson BM, Krebs VE. Development and Validation of a Machine Learning Algorithm After Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty: Applications to Length of Stay and Payment Models. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34:632–637. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2018.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Navarro SM, Wang EY, Haeberle HS, Mont MA, Krebs VE, Patterson BM, Ramkumar PN. Machine Learning and Primary Total Knee Arthroplasty: Patient Forecasting for a Patient-Specific Payment Model. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:3617–3623. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2018.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ramkumar PN, Haeberle HS, Bloomfield MR, Schaffer JL, Kamath AF, Patterson BM, Krebs VE. Artificial Intelligence and Arthroplasty at a Single Institution: Real-World Applications of Machine Learning to Big Data, Value-Based Care, Mobile Health, and Remote Patient Monitoring. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34:2204–2209. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2019.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ramkumar PN, Muschler GF, Spindler KP, Harris JD, McCulloch PC, Mont MA. Open mHealth Architecture: A Primer for Tomorrow's Orthopedic Surgeon and Introduction to Its Use in Lower Extremity Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32:1058–1062. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ravi D, Wong C, Deligianni F, Berthelot M, Andreu-Perez J, Lo B, Yang GZ. Deep Learning for Health Informatics. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2017;21:4–21. doi: 10.1109/JBHI.2016.2636665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Karnuta JM, Navarro SM, Haeberle HS, Billow DG, Krebs VE, Ramkumar PN. Bundled Care for Hip Fractures: A Machine-Learning Approach to an Untenable Patient-Specific Payment Model. J Orthop Trauma. 2019;33:324–330. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000001454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Greenstein AS, Teitel J, Mitten DJ, Ricciardi BF, Myers TG. An Electronic Medical Record-Based Discharge Disposition Tool Gets Bundle Busted: Decaying Relevance of Clinical Data Accuracy in Machine Learning. Arthroplast Today. 2020;6:850–855. doi: 10.1016/j.artd.2020.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Visweswaran S, Cooper GF. Patient-specific models for predicting the outcomes of patients with community acquired pneumonia. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2005:759–763. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Delving Deep into Rectifiers: Surpassing Human-Level Performance on ImageNet Classification. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2015 Dec 7-13; Santiago, Chile. IEEE, 2016: 1026-1034. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Russakovsky O, Deng J, Su H, Krause J, Satheesh S, Ma S, Huang Z, Karpathy A, Khosla A, Bernstein M, Berg AC, Fei-Fei L. ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge. Int J Comput Vis. 2015;115:211–252. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pereira S, Pinto A, Alves V, Silva CA. Brain Tumor Segmentation Using Convolutional Neural Networks in MRI Images. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2016;35:1240–1251. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2016.2538465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Setio AA, Ciompi F, Litjens G, Gerke P, Jacobs C, van Riel SJ, Wille MM, Naqibullah M, Sanchez CI, van Ginneken B. Pulmonary Nodule Detection in CT Images: False Positive Reduction Using Multi-View Convolutional Networks. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2016;35:1160–1169. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2016.2536809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhennan Yan, Yiqiang Zhan, Zhigang Peng, Shu Liao, Shinagawa Y, Shaoting Zhang, Metaxas DN, Xiang Sean Zhou. Multi-Instance Deep Learning: Discover Discriminative Local Anatomies for Bodypart Recognition. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2016;35:1332–1343. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2016.2524985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lessmann N, van Ginneken B, de Jong PA, Išgum I. Iterative fully convolutional neural networks for automatic vertebra segmentation and identification. Med Image Anal. 2019;53:142–155. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2019.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim YJ, Ganbold B, Kim KG. Web-Based Spine Segmentation Using Deep Learning in Computed Tomography Images. Healthc Inform Res. 2020;26:61–67. doi: 10.4258/hir.2020.26.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zawy Alsofy S, Stroop R, Fusek I, Welzel Saravia H, Sakellaropoulou I, Yavuz M, Ewelt C, Nakamura M, Fortmann T. Virtual Reality-Based Evaluation of Surgical Planning and Outcome of Monosegmental, Unilateral Cervical Foraminal Stenosis. World Neurosurg. 2019;129:e857–e865. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zawy Alsofy S, Nakamura M, Ewelt C, Kafchitsas K, Fortmann T, Schipmann S, Suero Molina E, Welzel Saravia H, Stroop R. Comparison of stand-alone cage and cage-with-plate for monosegmental cervical fusion and impact of virtual reality in evaluating surgical results. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2020;191:105685. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2020.105685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Forsberg D, Sjöblom E, Sunshine JL. Detection and Labeling of Vertebrae in MR Images Using Deep Learning with Clinical Annotations as Training Data. J Digit Imaging. 2017;30:406–412. doi: 10.1007/s10278-017-9945-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pesteie M, Abolmaesumi P, Ashab HA, Lessoway VA, Massey S, Gunka V, Rohling RN. Real-time ultrasound image classification for spine anesthesia using local directional Hadamard features. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg. 2015;10:901–912. doi: 10.1007/s11548-015-1202-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hetherington J, Lessoway V, Gunka V, Abolmaesumi P, Rohling R. SLIDE: automatic spine level identification system using a deep convolutional neural network. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg. 2017;12:1189–1198. doi: 10.1007/s11548-017-1575-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jamaludin A, Lootus M, Kadir T, Zisserman A, Urban J, Battié MC, Fairbank J, McCall I Genodisc Consortium. ISSLS PRIZE IN BIOENGINEERING SCIENCE 2017: Automation of reading of radiological features from magnetic resonance images (MRIs) of the lumbar spine without human intervention is comparable with an expert radiologist. Eur Spine J. 2017;26:1374–1383. doi: 10.1007/s00586-017-4956-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Al-Helo S, Alomari RS, Ghosh S, Chaudhary V, Dhillon G, Al-Zoubi MB, Hiary H, Hamtini TM. Compression fracture diagnosis in lumbar: a clinical CAD system. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg. 2013;8:461–469. doi: 10.1007/s11548-012-0796-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Swedberg JA, Steinbauer JR. Osteoarthritis. Am Fam Physician. 1992;45:557–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Braun HJ, Gold GE. Advanced MRI of articular cartilage. Imaging Med. 2011;3:541–555. doi: 10.2217/iim.11.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Braun HJ, Gold GE. Diagnosis of osteoarthritis: imaging. Bone. 2012;51:278–288. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Xue Y, Zhang R, Deng Y, Chen K, Jiang T. A preliminary examination of the diagnostic value of deep learning in hip osteoarthritis. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0178992. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0178992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ashinsky BG, Bouhrara M, Coletta CE, Lehallier B, Urish KL, Lin PC, Goldberg IG, Spencer RG. Predicting early symptomatic osteoarthritis in the human knee using machine learning classification of magnetic resonance images from the osteoarthritis initiative. J Orthop Res. 2017;35:2243–2250. doi: 10.1002/jor.23519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liu F, Zhou Z, Jang H, Samsonov A, Zhao G, Kijowski R. Deep convolutional neural network and 3D deformable approach for tissue segmentation in musculoskeletal magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2018;79:2379–2391. doi: 10.1002/mrm.26841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shah RF, Martinez AM, Pedoia V, Majumdar S, Vail TP, Bini SA. Variation in the Thickness of Knee Cartilage. The Use of a Novel Machine Learning Algorithm for Cartilage Segmentation of Magnetic Resonance Images. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34:2210–2215. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2019.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Olczak J, Fahlberg N, Maki A, Razavian AS, Jilert A, Stark A, Sköldenberg O, Gordon M. Artificial intelligence for analyzing orthopedic trauma radiographs. Acta Orthop. 2017;88:581–586. doi: 10.1080/17453674.2017.1344459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kruse C, Eiken P, Vestergaard P. Machine Learning Principles Can Improve Hip Fracture Prediction. Calcif Tissue Int. 2017;100:348–360. doi: 10.1007/s00223-017-0238-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Oosterhoff JHF, Doornberg JN Machine Learning Consortium. Artificial intelligence in orthopaedics: false hope or not? EFORT Open Rev. 2020;5:593–603. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.5.190092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Damron TA, Mann KA. Fracture risk assessment and clinical decision making for patients with metastatic bone disease. J Orthop Res. 2020;38:1175–1190. doi: 10.1002/jor.24660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Oh E, Seo SW, Yoon YC, Kim DW, Kwon S, Yoon S. Prediction of pathologic femoral fractures in patients with lung cancer using machine learning algorithms: Comparison of computed tomography-based radiological features with clinical features vs without clinical features. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2017;25:2309499017716243. doi: 10.1177/2309499017716243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Baker N, Alexander F, Bremer T, Hagberg A, Kevrekidis Y, Najm H, Parashar M, Patra A, Sethian J, Wild S, Willcox K, Lee S. Workshop Report on Basic Research Needs for Scientific Machine Learning: Core Technologies for Artificial Intelligence. Washington: U.S. Department of Energy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gonzalez-Dias P, Lee EK, Sorgi S, de Lima DS, Urbanski AH, Silveira EL, Nakaya HI. Methods for predicting vaccine immunogenicity and reactogenicity. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16:269–276. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2019.1697110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhang W, Lin W, Zhang D, Wang S, Shi J, Niu Y. Recent Advances in the Machine Learning-Based Drug-Target Interaction Prediction. Curr Drug Metab. 2019;20:194–202. doi: 10.2174/1389200219666180821094047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bini SA, Schilling PL, Patel SP, Kalore NV, Ast MP, Maratt JD, Schuett DJ, Lawrie CM, Chung CC, Steele GD. Digital Orthopaedics: A Glimpse Into the Future in the Midst of a Pandemic. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35:S68–S73. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2020.04.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Begg R, Kamruzzaman J. A machine learning approach for automated recognition of movement patterns using basic, kinetic and kinematic gait data. J Biomech. 2005;38:401–408. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Joyseeree R, Abou Sabha R, Mueller H. Applying machine learning to gait analysis data for disease identification. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2015;210:850–854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sikka RS, Baer M, Raja A, Stuart M, Tompkins M. Analytics in Sports Medicine: Implications and Responsibilities That Accompany the Era of Big Data. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2019;101:276–283. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.17.01601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cilla M, Borgiani E, Martínez J, Duda GN, Checa S. Machine learning techniques for the optimization of joint replacements: Application to a short-stem hip implant. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0183755. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Begg RK, Sparrow WA. Gait characteristics of young and older individuals negotiating a raised surface: implications for the prevention of falls. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:M147–M154. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.3.m147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Katoozian H, Davy DT. Effects of loading conditions and objective function on three-dimensional shape optimization of femoral components of hip endoprostheses. Med Eng Phys. 2000;22:243–251. doi: 10.1016/s1350-4533(00)00030-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chang PB, Williams BJ, Bhalla KS, Belknap TW, Santner TJ, Notz WI, Bartel DL. Design and analysis of robust total joint replacements: finite element model experiments with environmental variables. J Biomech Eng. 2001;123:239–246. doi: 10.1115/1.1372701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kowalczyk P. Design optimization of cementless femoral hip prostheses using finite element analysis. J Biomech Eng. 2001;123:396–402. doi: 10.1115/1.1392311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Fernandes PR, Folgado J, Ruben RB. Shape optimization of a cementless hip stem for a minimum of interface stress and displacement. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Engin. 2004;7:51–61. doi: 10.1080/10255840410001661637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]