Abstract

Cysteine is a conditionally essential amino acid that contributes to the synthesis of proteins and many important intracellular metabolites. Cysteine depletion can trigger iron-dependent non-apoptotic cell death–ferroptosis. Despite this, cysteine itself is normally maintained at relatively low levels within the cell, and many mechanisms that could act to buffer cysteine depletion do not appear to be especially effective or active, at least in cancer cells. How do we reconcile these seemingly paradoxical features? Here we describe the regulation of cysteine and contribution to ferroptosis and speculate about how the levels of this amino acid are controlled to govern non-apoptotic cell death.

Keywords: Ferroptosis, Metabolism, Cysteine, Glutathione, Iron

Introduction

Ferroptosis is an iron-dependent cell death process that is distinct from apoptosis and other non-apoptotic cell death processes described over the past twenty years [1, 2]. Ferroptosis is activated in a variety of pathophysiological settings, including ischemia/reperfusion injury, drug-induced toxicity, and chronic degenerative disease [3]. It may also be possible to induce ferroptotic cell death in tumors in vivo using small molecules or other interventions [4]. Thus, ferroptosis evidently holds much translational potential. This, in turn, has helped motivate a desire to better understand the basic biochemical regulation of this process.

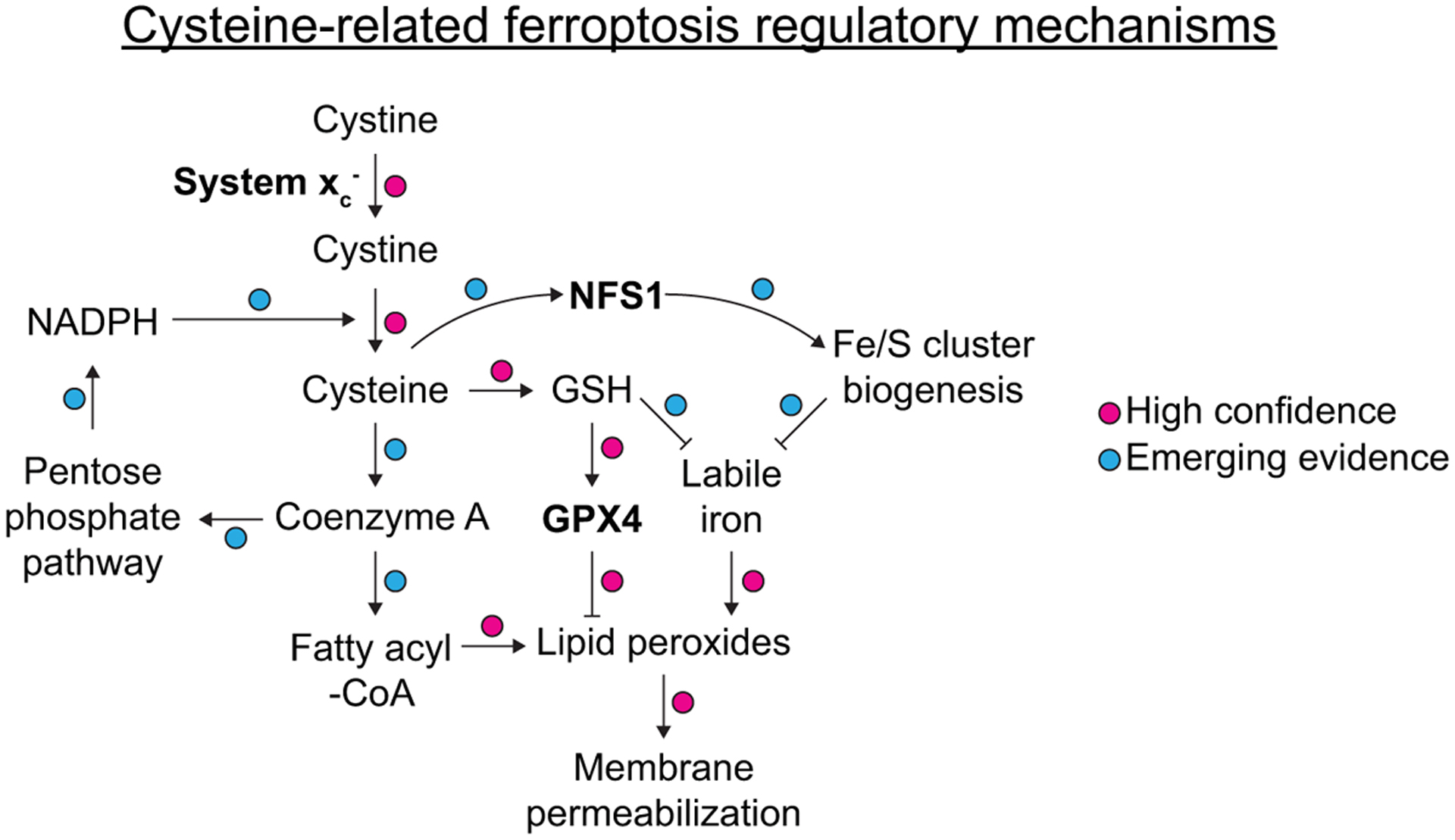

At the biochemical level, ferroptosis is triggered when the systems that normally protect membrane phospholipids from peroxidation are impaired [5] (Figure 1). Impaired lipid peroxidation defense allows for one or more (it remains controversial) iron-dependent lipid peroxidation reactions to run out of control, ultimately leading to plasma membrane permeabilization [6–8]. This lethal process does not appear to require a dedicated set of pro-death proteins (e.g., akin to apoptotic caspases), but rather emerges spontaneously when lipid peroxidation defenses are shut down. For this reason, ferroptosis has aptly been described as a form of cell self-sabotage, rather than organized cell suicide [9]. Despite progress, we still do not have a complete understanding of the ferroptosis mechanism, or how best to most effectively engage this mechanism therapeutically. Here, we focus on the role of a single amino acid, cysteine, to illustrate important examples of progress and paradox in the current investigation of ferroptosis.

Figure 1.

Overview of major elements of the ferroptosis pathway, with emphasis on the role of cysteine. Specific connections are annotated in the context of the existing literature on cysteine and ferroptosis as high confidence or as having emerging evidence. Note: for simplicity, transport and enzymatic reactions are not depicted in full, and not all known regulatory connections impacting cysteine metabolism are indicated.

Cysteine: the triple threat ferroptosis inhibitor

Cysteine is a thiol (-SH) containing amino acid long known to be essential to prevent the death and promote the proliferation of cells in culture [10, 11]. We now understand that cysteine uptake is specifically required by many cells to prevent the onset of ferroptosis [12, 13]. There is some evidence for direct cellular uptake of cysteine from the environment, perhaps via SLC1A4/5 (ASCT1/2) amino acid transporters [14, 15]. However, in the oxidizing environment found outside the cell, free cysteine is mostly thought to be present as the disulfide cystine [16]. Cystine can be imported into the cell via system xc−, a heterodimer of solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11, xCT) and solute carrier family 3 member 2 (SLC3A2, 4F2hc) [17]. Synthetic small molecules from the erastin family are potent inhibitors of system xc− function, capable of inducing ferroptosis in diverse cancer cell lines and models in vitro and in vivo [12, 13, 18]. Genetic disruption of Slc7a11 can also limit the ability of human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) cells to form xenografts and reduce the metastatic potential of mouse syngeneic BB16F10 melanoma cells [17, 19]. In a genetically engineered mouse model of PDAC, tumor growth is attenuated by deletion of Slc7a11, consistent with the induction of ferroptosis [20]. Direct cystine deprivation, or enzymatic degradation of extracellular cysteine/cystine, using an engineered enzyme, cyst(e)inase, can also induce ferroptosis in vitro, and attenuate tumor growth in vivo alone and in combination with other treatments, albeit not always with clear evidence for induction of cell death per se [20–25]. Having established by these examples that cysteine is required to prevent ferroptosis, we may ask: how does cysteine contribute to the suppression of ferroptosis?

What makes cysteine such a potent anti-ferroptotic molecule?

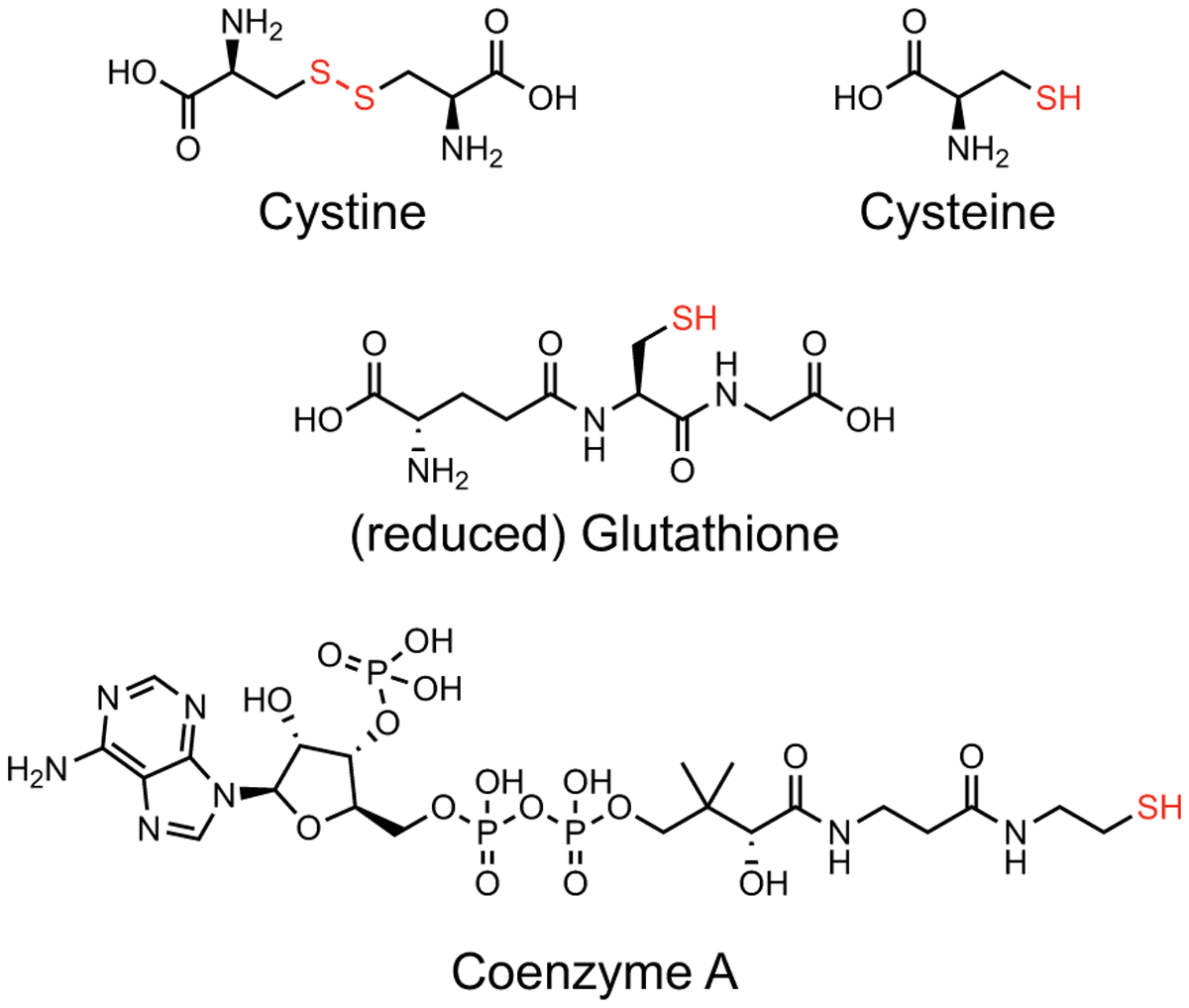

First, cysteine is the rate-limiting precursor for the synthesis of the non-ribosomal tripeptide glutathione (γ-L-glutamyl-L-cysteinylglycine) (Figures 1,2). Compared to glutamate and glycine, the two other constituent amino acids, cysteine is found in much lower abundance within the cell [26]. Once synthesized, the ability of glutathione to cycle between reduced (GSH) and oxidized (GSSG) forms makes this metabolite an essential cofactor for many enzymes involved in reactive oxygen species (ROS) defense. Most importantly for ferroptosis, GSH can be used by the lipid hydroperoxidase glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4). Genetic or pharmacological disruption of GPX4 activity results in accumulation of lipid peroxides and induction of ferroptosis in diverse models and contexts [27–30]. A minor mystery exists insofar as direct inhibition of GSH synthesis enzymes, or enhanced glutathione export, does not typically appear to be sufficient to induce ferroptosis [19, 20, 23, 31–33]. One possibility is that under conditions of extreme GSH limitation GPX4 employs alternative reducing agents - possibly other low molecular weight thiols or protein thiols - to maintain activity [34, 35].

Figure 2.

Structure of cysteine-containing metabolites. The disulfide or free thiol of each molecule is highlighted in red.

Second, cysteine also supplies sulfur for the synthesis of a second sulfur-containing molecule, coenzyme A (CoA) (Figure 1,2). Imported cysteine fluxes rapidly into CoA pools, and CoA has a potent yet poorly defined role in preventing ferroptosis, independent of GSH/GPX4, as shown by experiments where CoA synthesis is blocked by direct inhibition of the pantothenate pathway [20, 36, 37]. CoA can directly modify protein thiols via CoAlation [38]. CoAlation of glycolytic enzymes and/or the transcription factor p53 may enhance NADPH synthesis via the pentose phosphate pathway, generating a redox environment more conducive to the suppression of ferroptosis [37]. CoA is also used to ‘activate’ free fatty acids, prior to incorporation into membrane phospholipids by acyl-CoA synthetase long chain family member (ACSL) enzymes [39–42]. CoA depletion may therefore alter the ongoing activation and membrane incorporation of mono- and poly-unsaturated fatty acids into lyso-phospholipids, potentially resulting in a net increase in ferroptosis sensitivity. Finally, the potent pro-ferroptotic effect of cysteine deprivation versus GSH deprivation could be explained if CoA can be used as a direct reducing substrate by GPX4 when GSH pools become limited.

Third, in addition to effects on low molecular weight thiols, cysteine directly impacts ferroptosis by impinging on the regulation of iron metabolism (Figure 1). Cysteine is the source of the key sulfur atom used in the biogenesis of iron/sulfur (Fe/S) clusters essential for the activity of dozens of enzymes. Genetic disruption of NFS1 cysteine desulfurase, the enzyme responsible for extracting sulfur from cysteine for use in Fe/S cluster biogenesis, sensitizes to ferroptosis inducers in vitro and in vivo. The supposition is that cysteine depletion, leading to decreased Fe/S cluster biosynthesis, induces an iron starvation response which leads to greater iron import, which in turn enhances ferroptosis [24].

In addition to its effect on Fe/S cluster biosynthesis, cysteine may also influence iron handling within the cell via GSH. Mammalian cells have a pool of loosely coordinated ‘labile’ iron within the cytosol, which is presumed to contribute directly to the induction of ferroptosis. GSH is one important ligand for labile Fe(II) [43]. System xc− inhibition leads to an apparent rise in intracellular labile iron levels, as detected using fluorescent probes, possibly reflecting the loss of GSH [44]. Increased labile intracellular iron could directly enhance Fenton chemistry that generates radicals which initiate ferroptosis. Notably, GSH is also an essential cofactor of glutaredoxin proteins, where the thiol group of GSH helps coordinate Fe/S clusters during their biogenesis and transfer to substrate apoproteins [45]. System xc− inhibition provokes an apparent iron starvation response in cancer cells [24, 46], and one component of this response could be direct disruption to glutaredoxin-dependent Fe/S cluster biosynthesis. Thus, loss of GSH, downstream of cysteine depletion, would therefore tend to promote ferroptosis by increasing unliganded Fe(II) levels, which activates an iron starvation response and leads to increased iron uptake.

These considerations suggest that loss of intracellular cysteine may contribute to the induction of ferroptosis in at least three different ways: (i) inhibition of GSH-dependent enzymes, (ii) loss of CoA, and (iii) enhanced intracellular free iron (Figure 1). While co-depletion of GSH and CoA appears to be essential to inactivate GPX4 and induce ferroptosis, increased intracellular iron levels likely further amplify ferroptotic lipid peroxidation. Cysteine deprivation may also promote ferroptosis by causing a direct inhibition of protein synthesis and loss of GPX4 protein expression [47], although this appears to be a highly cell-type-specific rather than universal effect of cysteine deprivation [33, 48]. Cysteine may also contribute to ferroptosis suppression via metabolism to sulfane sulfur species [49], but this has not specifically been examined. Regardless, the ability of a single metabolite to contribute to ferroptosis regulation in multiple ways may explain why reduced cysteine levels can potently induce ferroptosis in such diverse contexts, as noted above. Knowing this, however, a number of paradoxes emerge connected to the question of why cancer cells do not do a better job maintaining intracellular cysteine and thereby preventing the induction of ferroptosis.

Paradoxes

1. Cysteine: why so low?

Cysteine is clearly essential to ward off ferroptosis through diverse mechanisms. Within the cell, cysteine must flux into protein synthesis, and is an essential precursor for the synthesis of numerous other molecules, including GSH, CoA, Fe/S clusters, and others [16]. From this perspective, one might assume that the cell would endeavor to maintain a large pool of intracellular cysteine to guard against potential shortfalls. On the contrary, cysteine appears to be one of the least abundant amino acids in the cell (< 100 μM), 10-to-100-fold less abundant than glutathione, as well as other amino acids like glutamine, serine, valine [26]. A significantly higher local concentration of cystine is found within the lysosome, where this amino acid is specifically concentrated through the action of the major facilitator superfamily domain containing 12 (MFSD12) transporter [50]. Of note, intracellular cysteine/cystine measurement can be challenging due to the need for careful derivatization of these redox active species [51], a step not employed in all studies. However, the preponderance of evidence is consistent with cysteine being a low abundance cytosolic amino acid.

The paradox is: why are levels of cysteine generally maintained at such low overall levels, and compartmentalized away in the lysosome, despite being so important to ward off ferroptosis? One explanation is that cysteine itself can be toxic, when present at high levels. In the bacterium E. coli, elevated levels of intracellular cysteine can lead to reduction of Fe(III) to Fe(II), thereby promoting Fenton chemistry that results in lethal oxidative DNA damage [52, 53]. By contrast, GSH is much less able to promote this reaction, possibly explaining why GSH is able to safely accumulate to millimolar concentrations within the eukaryotic cell cytosol [52]. In the budding yeast S. cerevisiae, disruption of vacuolar/lysosomal function can lead to excess cytosolic cysteine accumulation, which interferes with iron handling, leading to ROS accumulation, impaired mitochondrial function, and reduced replicative lifespan [54]. Whether these mechanisms are active in mammalian cells is unclear, but if so, could explain why cysteine does not accumulate to high intracellular levels.

In mammalian cell lines specifically, cysteine toxicity is linked to several mechanisms. Within the cell, cysteine can be metabolized in a number of ways, including to cysteine sulfinic acid (CSA) by cysteine dioxygenase 1 (CDO1). CDO1-dependent cysteine metabolism to CSA and sulfite (SO32-) may ultimately limit cell proliferation by feeding back to disrupt the import of cystine itself, to the extent that cancer cells frequently silence CDO1 expression epigenetically [51]. High levels of cysteine may also induce protein misfolding and endoplasmic reticulum stress [55, 56], possibly by directly interfering with protein structure [57]. Taken together, these observations suggest that minimizing the effects of cysteine toxicity may explain the overall low levels found within the cell and the need to sequester most cysteine within the lysosome/vacuole.

As noted above, the system xc− cystine/glutamate antiporter is the major cystine transporter in most cancer cells. High levels of system xc−-mediated cystine import are specifically unfavorable for maximal cell proliferation. Ongoing system xc− activity, especially when heightened by oncogenic mutations that enhance nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 (NFE2L2/NRF2) pathway activity, stresses the intracellular glutamate pool, requiring import of glutamine (a glutamate precursor) to compensate, thereby in turn sensitizing cells to limitations this and other nutrients [58–62]. Furthermore, once imported, cystine itself must be reduced to cysteine. This process consumes NADPH, limiting the use of this key reducing metabolite in other anabolic reactions [51, 63]. Thus, limiting basal system xc−-mediated cystine import and maintaining low intracellular cysteine levels appear essential for survival and proliferation. The downside of this situation is that cells appear poised to run out of cysteine quickly if acutely deprived of this metabolite.

2. Why is cysteine even essential?

Cysteine is clearly essential for cancer cell survival, at least in vitro. Cysteine is one of two sulfur-containing amino acids, the other being methionine. Compared to cysteine, methionine is present at ~10-fold higher intracellular concentrations [26]. The transsulfuration pathway can synthesize cysteine using methionine as a precursor [64, 65]. Thus, a mammalian cell theoretically has available to it a pathway capable of compensating for the loss of cysteine.

Paradoxically, however, this mechanism evidently is not especially widespread or effective, as ferroptosis is readily induced in dozens of different cell lines in response to acute administration of system xc− inhibition [18, 27, 66]. Indeed, where this has been examined carefully by metabolic tracing, the transsulfuration pathway does not appear to be especially active in many cancer cells basally, and at best normally contributes only marginally to the ability of cancer cells to prevent ferroptosis in response to acute cysteine deprivation [67–69]. This may be related to limited expression of glycine N-methyltransferase (GNMT) or other methyltransferases that support the conversion of S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) to S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH), an essential step in the methionine cycle required for the subsequent synthesis of homocysteine and ultimately cysteine [70]. This may also relate to the fact that in vivo transsulfuration is most active in liver, and cells derived from other tissues that are cultured outside the body remain unaccustomed to the need for high levels of basal transsulfuration pathway activity [65]. In any event, low transsulfuration pathway activity in a given cell could be viewed as a ‘missed opportunity’ to provide redundant protection against the effects of acute cysteine deprivation.

The cell may have other sources of cysteine to make up for shortfalls when the extracellular environment is depleted of this metabolite. Reduced glutathione is typically present at much higher intracellular concentrations than cysteine and, given the toxicity of free cysteine, may represent the preferred ‘safe’ storage form of cysteine within the cell [52, 71]. To obtain this cysteine, GSH must be catabolized. GSH export and extracellular catabolism via the gamma-glutamyl cycle does contribute to intracellular cysteine pools [72], and disruption of the key enzyme gamma glutamyl transpeptidase 1 (GGT1) may be sufficient to induce ferroptosis [73]. However, this is likely to be only useful in the short-term. Long-term cysteine deprivation, coupled with GSH export and GGT1-mediated GSH catabolism may transiently help maintain CoA pools, but would simultaneously hasten the inactivation of GPX4 by depriving it of its key co-substrate.

3. mTOR, ATF4, and (the lack of) compensatory responses

The above discussion suggests that, basally, cancer cells are not well prepared to manage acute cysteine depletion. Again, this is clearly evidenced by the fact that so many cancer cells are highly susceptible to ferroptosis upon cysteine deprivation. This is especially surprising because the cell has several potent mechanisms to respond to amino acid scarcity (or ROS stress) and restore homeostasis. Paradoxically, these mechanisms do not appear sufficient to prevent ferroptosis.

Cells invest much energy in coupling amino acids levels to anabolic processes, most notably protein synthesis. The mTOR pathway can sense the levels of key amino acid and couple this information to the stimulation of anabolism (including protein synthesis) and the suppression of catabolism (including lysosome biogenesis, autophagy, and proteasome biogenesis) [74]. Some evidence suggests that SLC7A11 disruption or cysteine deprivation can lead to inhibition of mTOR signaling [19, 47, 75]. However, cysteine has not generally been described as a core amino acid input to mTOR and, unlike for example leucine and arginine, no specialized cysteine sensing mechanisms have been described that would directly impinge on mTOR function [76]. Thus, any inhibition of mTOR signaling following cysteine deprivation may take too long to be relevant to modulation of ferroptosis; some cells maintain full mTOR pathway activity following cysteine starvation at least up to the point of ferroptosis induction [33]. Indeed, ongoing mTOR activity in the face of cysteine deprivation could actually drive a cell towards ferroptosis by promoting the continuous flux of cysteine into de novo protein synthesis and away from GSH synthesis and by limiting autophagy, proteasome biogenesis, and other catabolic processes that could generate cysteine from whole protein [33]. mTOR may also directly limit SLC7A11-dependent cystine uptake, providing another mechanism whereby active mTOR may itself promote ferroptosis [77].

We may speculate that one reason why mTOR does not respond rapidly to reduced cysteine levels is that another cellular system is primarily responsible for this function: the GCN2/ATF4 pathway. Uncharged tRNAs that arise upon amino acid deprivation activate the kinase eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 alpha kinase 4 (EIF2AK4, more commonly known as GCN2). Phosphorylation by GCN2 of the transcription factor ATF4 upregulates its activity to increase the expression of many genes related to cysteine import and the transsulfuration pathway, including SLC7A11 and cystathionine beta-synthase (CBS) [70, 78–80]. Unlike the equivocal data concerning acute inhibition of mTOR following cysteine deprivation, the GCN2/ATF4 pathway is clearly activated following acute cysteine deprivation [12, 18]. However, there are at least three reasons why this ATF4-driven response may fail to prevent ferroptosis. First, compared to a post-translational mechanism centered on a kinase like mTOR, a transcriptional response centered on ATF4 is going to be much slower and may not be sufficiently engaged in time for a fully protective transcription response to be mounted. Second, a transcriptional response that leads to import of additional cysteine via system xc− is destined to fail if no cystine is present in the first place or if pharmacological transport inhibitors are present. Third, ATF4 also increases expression of the gene CHAC1, which encodes an enzyme that catalyzes the cleavage of the γ-glutamyl bond of GSH, facilitating the liberation of cysteine, but destroying this key GPX4 co-substrate [81, 82]. Indeed, CHAC1 is highly upregulated in response to system xc− inhibition, and CHAC1-mediated GSH catabolism can enhance ferroptosis in some contexts [12, 83]. Under conditions of acute cysteine starvation, it may be that in the effort to quickly liberate cysteine from GSH, CHAC1-catalyzed intracellular GSH destruction contributes to a feedforward loop that accelerates the loss of GPX4 function. While as discussed above GSH depletion alone does not appear to be sufficient to induce ferroptosis, the destruction of GSH would certainly favor the inhibition of GPX4 and the execution of ferroptosis. CHAC1-mediated GSH catabolism may counterbalance any protective advantages of transsulfuration pathway activation in response to acute cysteine deprivation.

A modest proposal

The above evidence suggests an intriguing hypothesis: that at least some cancer cells are wired in a way that maximizes the chances that acute cysteine depletion will induce ferroptosis. If so, we might expect natural mechanisms that specifically inhibit cysteine metabolism to induce or sensitize to ferroptosis. Emerging evidence suggests that this may be the case.

The tumor suppressor p53 can reduce expression of SLC7A11 and limit cysteine import [67, 84]. Mechanistically, this may involve direct binding to the SLC7A11 genomic locus by p53 [84], or modulation of histone H2B monoubiquitination in the vicinity of the SLC7A11 locus by USP7, which can be recruited to the nucleus by p53 [85]. The ability of p53 to limit SLC7A11 expression may contribute to the ability of this protein to suppress tumor formation [84]. BAP1 is another tumor suppressor whose function in vivo appears, at least partially, to depend on repression of SLC7A11 expression, reduced cystine import, and the induction of ferroptosis. Mechanistically, BAP1, a nuclear deubiquitinase, removes ubiquitin from lysine 119 of histone H2A; when this occurs at the SLC7A11 promoter, transcription is repressed [86, 87]. Thus, the modulation of histone ubiquitination in the vicinity of the SLC7A11 locus emerges from multiple studies as a key inducer of ferroptosis. The tumor suppressor ARF may also function, in part, by limiting SLC7A11 expression and promoting ferroptosis [88]. Together, these results indicate that tumor suppressors may function in part by limiting cysteine uptake and promoting ferroptosis.

The beneficial effects of immunotherapy may likewise involve sensitization to ferroptosis. Immunotherapy-activated CD8+ T cells can release interferon gamma (IFNγ), which via the JAK/STAT1 pathway causes transcriptional downregulation of SLC7A11 expression in target cancer cells, reducing cysteine import, and promoting ferroptosis [25]. This repressive effect may be augmented by radiotherapy that activates the DNA damage sensor kinase ATM, which itself further contributes to repression of SLC7A11 expression in response to ionizing radiation [89]. These examples illustrate the possibility that organisms may have evolved means to cause ferroptosis specifically by targeting the vulnerable cysteine metabolic network.

Caveats of the proposal

1. Slow adaptation

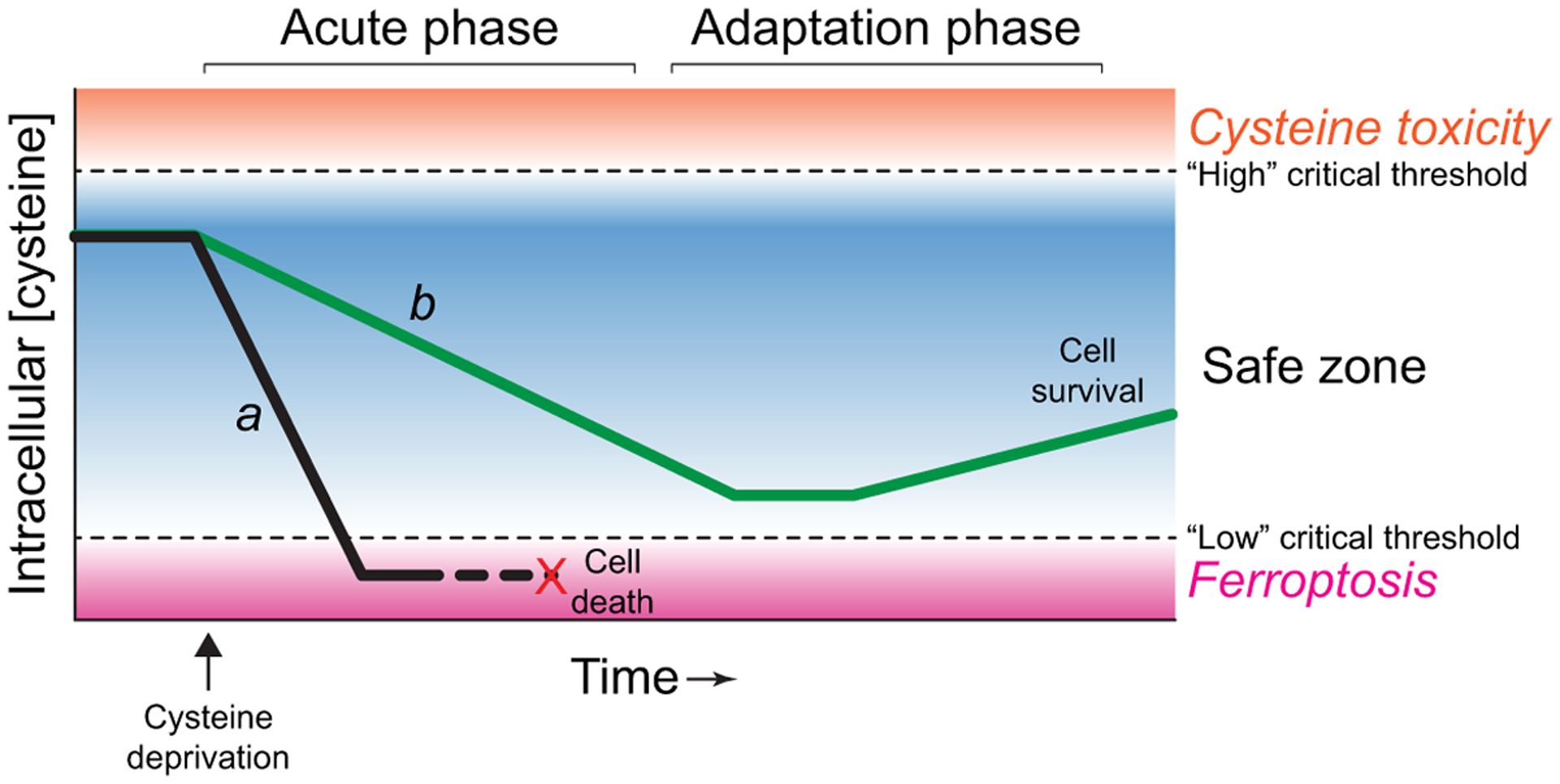

Acute cysteine deprivation is a potent inducer of ferroptosis. However, what about when cysteine starvation occurs more slowly or is incomplete? Notwithstanding what was mentioned above about basal transsulfuration pathway activity, this metabolic pathway is upregulated in some cancer cells under conditions of cysteine deprivation in a GCN2/ATF4-dependent manner, with CBS and a second gene in this pathway, cystathionine gamma-lyase (CTH), being direct transcriptional targets of ATF4, and that this is sufficient to promote tumor growth in low-cysteine environments [70]. Genetic disruption of cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase 1 (CARS1, or more commonly CARS) results in a compensatory ATF4-dependent upregulation of these same transsulfuration pathway genes, conferring resistance to system xc− inhibitor-induced ferroptosis [90]. The transsulfuration pathway can also be upregulated by activation of the NRF2 pathway in response to prolonged, low-level system xc− inhibition over several days; cells that survive the initial challenge increase the expression of CBS and this appears important for acquired tolerance of system xc− inhibition-induced ferroptosis [91]. Other evidence is consistent with the notion that activated ATF4 can suppress ferroptosis in through transcriptional upregulation of one or more targets [80, 92, 93], an effect that evidently overcomes any ATF4-driven, ChaC glutathione specific gamma-glutamylcyclotransferase 1 (CHAC1)-mediated GSH catabolism. These results indicate that prolonged incomplete cysteine deprivation could induce an adaptive response that helps protect cells from further cysteine depletion and ferroptosis. Perhaps if cysteine depletion occurs slowly and/or up to a point just before irreversible commitment to ferroptosis, the cell may be able to effectively upregulate such a protective response (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

A timing-based model of how cysteine depletion impacts cell fate. Cell a (black line) experiences rapid cysteine depletion and undergoes ferroptosis, while cell b (green line) experiences slow cysteine depletion and is able to adapt via the upregulation of compensatory processes (e.g., ATF4 pathway activity).

2. Cysteine monitoring: a team effort?

Other considerations may explain why cysteine levels per se are not closely monitored, despite the importance of this amino acid to prevent ferroptosis. Gene expression profiling demonstrates that depletion of non-sulfur-containing amino acids (e.g. leucine) triggers the GCN2/ATF4-dependent upregulation of genes involved in cysteine metabolism (e.g. SLC7A11, CARS, CTH) [78]. Thus, any amino acid deprivation condition that triggers GCN2 activation and ATF4 induction may be sufficient to induce a protective response that enhances cysteine metabolism in parallel, even if the initiating stimulus is not cysteine deprivation per se [94]. Thus, cells may be able to maintain rather low levels of intracellular cysteine, despite the core importance of this metabolite for survival, because the GCN2/ATF4 pathway monitors the levels of many amino acids and always induces a protective response that enhances cysteine metabolism. This implies that what might not have been anticipated evolutionarily is the selective depletion of cysteine along with the maintenance of other amino acid levels, and it is this gap that tumor suppressors, the immune system, and synthetic small molecules try to exploit to unleash ferroptosis.

3. Cysteine: the ultimate loner?

In support of the above model, depletion of other amino acids together with cysteine can have a profound effect on cell death. The lethality of system xc− blockade is prevented when glutamine uptake and metabolism is simultaneously disrupted [13, 95]. It is proposed that glutamine is needed to promote tricarboxylic cycle activity and mitochondrial ROS production that drive ferroptosis [95]. Methionine restriction can also inhibit ferroptosis through a distinct mechanism, by limiting polyamine metabolism and ROS accumulation [68]. However, other more generalizable features could explain the ability to different amino acids to protect form ferroptosis. Recently, it was shown that individual depletion of arginine, methionine, glutamine, lysine or valine from the growth medium inhibited ferroptosis in response to cysteine withdrawal or pharmacological system xc− inhibition [33]. Suppression of ferroptosis was not clearly explained by inhibition of mTOR activity or, notwithstanding what was just mentioned above, by induction of ATF4. Rather, suppression of ferroptosis correlated with inhibition of cell proliferation. Arrested proliferation may allow for better conservation of existing intracellular glutathione pools. Individual amino acid depletions may also directly attenuate mRNA translation, independent of the mTOR and GCN2/ATF4 pathways, possibly though a mechanism involving the kinase GCN1 activator of EIF2AK4 (GCN1) [96–98].

Regardless of the specific mechanism in play, these new results indicate that cysteine depletion may need to occur in isolation of other amino acid depletions for ferroptosis to be induced most effectively. This might be difficult to achieve, especially in vivo. In tumor regions, many amino acids are present at low levels compared to surrounding non-tumorous tissue [99, 100]. This could limit the ability of cancer cells to undergo ferroptosis in response to cysteine deprivation, and possibly accounting for the somewhat unimpressive effects of the engineered cysteine-degrading enzyme cyst(e)inase on tumor regression in vivo [20–25].

Conclusions

Cysteine is a potent regulator of ferroptosis. Cysteine levels indirectly govern cellular susceptibility to ferroptosis through effects on the synthesis of GSH, CoA, and potentially other metabolites. These metabolites are required for the ongoing function of the antioxidant network that prevents ferroptosis, and to manage the intracellular distribution of iron, the key ferroptotic catalyst. We propose that the low basal abundance of cysteine, together with the apparent ‘blindness’ of different mechanisms to acute cysteine deprivation renders cells highly susceptible to ferroptosis. It appears that this sensitivity is exploited by natural stimuli including tumor suppressor proteins and the immune system to induce or sensitize to ferroptosis. By contrast, it is also notable that certain cancer cell lineages and specific oncogenic mutations appear to specifically enhance SLC7A11 stability and/or cysteine import and metabolism [51, 80, 101, 102]. While increased cysteine uptake is not a universal response to oncogene activation (e.g. [103, 104]), high levels of cysteine import may be an adaptive feature of at least some cancer cells to ward off ferroptosis or other forms of oxidative stress in vivo. Collectively, we propose that low basal cysteine levels, and inadequate mechanisms to cope with acute cysteine deprivation, may leave the door unexpectedly open to ferroptosis in many contexts where selective cysteine deprivation can be achieved.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank D. Armenta, G. Forcina, and L. Magtanong for comments. S.J.D. is supported by the NIH (1R01GM122923).

Abbreviations:

- ATF4

activating transcription factor 4

- NRF2

nuclear factor, erythroid 2 like 2

- PDAC

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- CoA

coenzyme A

- ACSL

acyl-CoA synthetase long chain family member

- GSH

(reduced) glutathione

- Fe/S

iron/sulfur

- CSA

cysteine sulfinic acid

- NADPH

(reduced) nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: S.J.D. is a member of the scientific advisory board of Ferro Therapeutics, has consulted for AbbVie and Toray Industries, and holds patents related to ferroptosis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Koren E & Fuchs Y (2021) Modes of Regulated Cell Death in Cancer, Cancer Discov. 11, 245–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jiang X, Stockwell BR & Conrad M (2021) Ferroptosis: mechanisms, biology and role in disease, Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stockwell BR, Jiang X & Gu W (2020) Emerging Mechanisms and Disease Relevance of Ferroptosis, Trends Cell Biol. 30, 478–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dixon SJ S. BR (2019) The hallmarks of ferroptosis, Annual Review of Cancer Biology. 3, 35–54. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cao JY & Dixon SJ (2016) Mechanisms of ferroptosis, Cell Mol Life Sci. 73, 2195–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conrad M & Pratt DA (2019) The chemical basis of ferroptosis, Nat Chem Biol. 15, 1137–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yan B, Ai Y, Sun Q, Ma Y, Cao Y, Wang J, Zhang Z & Wang X (2020) Membrane Damage during Ferroptosis Is Caused by Oxidation of Phospholipids Catalyzed by the Oxidoreductases POR and CYB5R1, Mol Cell. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zou Y, Li H, Graham ET, Deik AA, Eaton JK, Wang W, Sandoval-Gomez G, Clish CB, Doench JG & Schreiber SL (2020) Cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase contributes to phospholipid peroxidation in ferroptosis, Nat Chem Biol. 16, 302–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Green DR (2019) The Coming Decade of Cell Death Research: Five Riddles, Cell. 177, 1094–1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bannai S, Tsukeda H & Okumura H (1977) Effect of antioxidants on cultured human diploid fibroblasts exposed to cystine-free medium, Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 74, 1582–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morgan JF & Morton HJ (1955) Studies on the sulfur metabolism of tissues cultivated in vitro. I. A critical requirement for L-cystine, J Biol Chem. 215, 539–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dixon SJ, Patel DN, Welsch M, Skouta R, Lee ED, Hayano M, Thomas AG, Gleason CE, Tatonetti NP, Slusher BS & Stockwell BR (2014) Pharmacological inhibition of cystine-glutamate exchange induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and ferroptosis, Elife. 3, e02523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, Patel DN, Bauer AJ, Cantley AM, Yang WS, Morrison B 3rd & Stockwell BR (2012) Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death, Cell. 149, 1060–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang W, Trachootham D, Liu J, Chen G, Pelicano H, Garcia-Prieto C, Lu W, Burger JA, Croce CM, Plunkett W, Keating MJ & Huang P (2012) Stromal control of cystine metabolism promotes cancer cell survival in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, Nat Cell Biol. 14, 276–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freidman N, Chen I, Wu Q, Briot C, Holst J, Font J, Vandenberg R & Ryan R (2020) Amino Acid Transporters and Exchangers from the SLC1A Family: Structure, Mechanism and Roles in Physiology and Cancer, Neurochem Res. 45, 1268–1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonifacio VDB, Pereira SA, Serpa J & Vicente JB (2021) Cysteine metabolic circuitries: druggable targets in cancer, Br J Cancer. 124, 862–879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sato M, Onuma K, Domon M, Hasegawa S, Suzuki A, Kusumi R, Hino R, Kakihara N, Kanda Y, Osaki M, Hamada J, Bannai S, Feederle R, Buday K, Angeli JPF, Proneth B, Conrad M, Okada F & Sato H (2020) Loss of the cystine/glutamate antiporter in melanoma abrogates tumor metastasis and markedly increases survival rates of mice, Int J Cancer. 147, 3224–3235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Y, Tan H, Daniels JD, Zandkarimi F, Liu H, Brown LM, Uchida K, O’Connor OA & Stockwell BR (2019) Imidazole Ketone Erastin Induces Ferroptosis and Slows Tumor Growth in a Mouse Lymphoma Model, Cell Chem Biol. 26, 623–633 e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daher B, Parks SK, Durivault J, Cormerais Y, Baidarjad H, Tambutte E, Pouyssegur J & Vucetic M (2019) Genetic Ablation of the Cystine Transporter xCT in PDAC Cells Inhibits mTORC1, Growth, Survival, and Tumor Formation via Nutrient and Oxidative Stresses, Cancer Res. 79, 3877–3890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Badgley MA, Kremer DM, Maurer HC, DelGiorno KE, Lee HJ, Purohit V, Sagalovskiy IR, Ma A, Kapilian J, Firl CEM, Decker AR, Sastra SA, Palermo CF, Andrade LR, Sajjakulnukit P, Zhang L, Tolstyka ZP, Hirschhorn T, Lamb C, Liu T, Gu W, Seeley ES, Stone E, Georgiou G, Manor U, Iuga A, Wahl GM, Stockwell BR, Lyssiotis CA & Olive KP (2020) Cysteine depletion induces pancreatic tumor ferroptosis in mice, Science. 368, 85–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cramer SL, Saha A, Liu J, Tadi S, Tiziani S, Yan W, Triplett K, Lamb C, Alters SE, Rowlinson S, Zhang YJ, Keating MJ, Huang P, DiGiovanni J, Georgiou G & Stone E (2017) Systemic depletion of L-cyst(e)ine with cyst(e)inase increases reactive oxygen species and suppresses tumor growth, Nat Med. 23, 120–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poursaitidis I, Wang X, Crighton T, Labuschagne C, Mason D, Cramer SL, Triplett K, Roy R, Pardo OE, Seckl MJ, Rowlinson SW, Stone E & Lamb RF (2017) Oncogene-Selective Sensitivity to Synchronous Cell Death following Modulation of the Amino Acid Nutrient Cystine, Cell Rep. 18, 2547–2556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cao JY, Poddar A, Magtanong L, Lumb JH, Mileur TR, Reid MA, Dovey CM, Wang J, Locasale JW, Stone E, Cole SPC, Carette JE & Dixon SJ (2019) A Genome-wide Haploid Genetic Screen Identifies Regulators of Glutathione Abundance and Ferroptosis Sensitivity, Cell Rep. 26, 1544–1556 e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alvarez SW, Sviderskiy VO, Terzi EM, Papagiannakopoulos T, Moreira AL, Adams S, Sabatini DM, Birsoy K & Possemato R (2017) NFS1 undergoes positive selection in lung tumours and protects cells from ferroptosis, Nature. 551, 639–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang W, Green M, Choi JE, Gijon M, Kennedy PD, Johnson JK, Liao P, Lang X, Kryczek I, Sell A, Xia H, Zhou J, Li G, Li J, Li W, Wei S, Vatan L, Zhang H, Szeliga W, Gu W, Liu R, Lawrence TS, Lamb C, Tanno Y, Cieslik M, Stone E, Georgiou G, Chan TA, Chinnaiyan A & Zou W (2019) CD8(+) T cells regulate tumour ferroptosis during cancer immunotherapy, Nature. 569, 270–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abu-Remaileh M, Wyant GA, Kim C, Laqtom NN, Abbasi M, Chan SH, Freinkman E & Sabatini DM (2017) Lysosomal metabolomics reveals V-ATPase- and mTOR-dependent regulation of amino acid efflux from lysosomes, Science. 358, 807–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang WS, SriRamaratnam R, Welsch ME, Shimada K, Skouta R, Viswanathan VS, Cheah JH, Clemons PA, Shamji AF, Clish CB, Brown LM, Girotti AW, Cornish VW, Schreiber SL & Stockwell BR (2014) Regulation of ferroptotic cancer cell death by GPX4, Cell. 156, 317–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Friedmann Angeli JP, Schneider M, Proneth B, Tyurina YY, Tyurin VA, Hammond VJ, Herbach N, Aichler M, Walch A, Eggenhofer E, Basavarajappa D, Radmark O, Kobayashi S, Seibt T, Beck H, Neff F, Esposito I, Wanke R, Forster H, Yefremova O, Heinrichmeyer M, Bornkamm GW, Geissler EK, Thomas SB, Stockwell BR, O’Donnell VB, Kagan VE, Schick JA & Conrad M (2014) Inactivation of the ferroptosis regulator Gpx4 triggers acute renal failure in mice, Nat Cell Biol. 16, 1180–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ingold I, Berndt C, Schmitt S, Doll S, Poschmann G, Buday K, Roveri A, Peng X, Porto Freitas F, Seibt T, Mehr L, Aichler M, Walch A, Lamp D, Jastroch M, Miyamoto S, Wurst W, Ursini F, Arner ESJ, Fradejas-Villar N, Schweizer U, Zischka H, Friedmann Angeli JP & Conrad M (2018) Selenium Utilization by GPX4 Is Required to Prevent Hydroperoxide-Induced Ferroptosis, Cell. 172, 409–422 e21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shimada K, Skouta R, Kaplan A, Yang WS, Hayano M, Dixon SJ, Brown LM, Valenzuela CA, Wolpaw AJ & Stockwell BR (2016) Global survey of cell death mechanisms reveals metabolic regulation of ferroptosis, Nat Chem Biol. 12, 497–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harris IS, Endress JE, Coloff JL, Selfors LM, McBrayer SK, Rosenbluth JM, Takahashi N, Dhakal S, Koduri V, Oser MG, Schauer NJ, Doherty LM, Hong AL, Kang YP, Younger ST, Doench JG, Hahn WC, Buhrlage SJ, DeNicola GM, Kaelin WG Jr. & Brugge JS (2019) Deubiquitinases Maintain Protein Homeostasis and Survival of Cancer Cells upon Glutathione Depletion, Cell Metab. 29, 1166–1181 e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harris IS, Treloar AE, Inoue S, Sasaki M, Gorrini C, Lee KC, Yung KY, Brenner D, Knobbe-Thomsen CB, Cox MA, Elia A, Berger T, Cescon DW, Adeoye A, Brustle A, Molyneux SD, Mason JM, Li WY, Yamamoto K, Wakeham A, Berman HK, Khokha R, Done SJ, Kavanagh TJ, Lam CW & Mak TW (2015) Glutathione and thioredoxin antioxidant pathways synergize to drive cancer initiation and progression, Cancer Cell. 27, 211–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Conlon M, Poltorack CD, Forcina GC, Armenta DA, Mallais M, Perez MA, Wells A, Kahanu A, Magtanong L, Watts JL, Pratt DA & Dixon SJ (2021) A compendium of kinetic modulatory profiles identifies ferroptosis regulators, Nat Chem Biol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roveri A, Maiorino M, Nisii C & Ursini F (1994) Purification and characterization of phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase from rat testis mitochondrial membranes, Biochim Biophys Acta. 1208, 211–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Godeas C, Tramer F, Micali F, Roveri A, Maiorino M, Nisii C, Sandri G & Panfili E (1996) Phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase (PHGPx) in rat testis nuclei is bound to chromatin, Biochem Mol Med. 59, 118–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leu JI, Murphy ME & George DL (2019) Mechanistic basis for impaired ferroptosis in cells expressing the African-centric S47 variant of p53, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 116, 8390–8396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leu JI, Murphy ME & George DL (2020) Functional interplay among thiol-based redox signaling, metabolism, and ferroptosis unveiled by a genetic variant of TP53, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 117, 26804–26811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gout I (2018) Coenzyme A, protein CoAlation and redox regulation in mammalian cells, Biochem Soc Trans. 46, 721–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dixon SJ, Winter GE, Musavi LS, Lee ED, Snijder B, Rebsamen M, Superti-Furga G & Stockwell BR (2015) Human Haploid Cell Genetics Reveals Roles for Lipid Metabolism Genes in Nonapoptotic Cell Death, ACS Chem Biol. 10, 1604–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kagan VE, Mao G, Qu F, Angeli JP, Doll S, Croix CS, Dar HH, Liu B, Tyurin VA, Ritov VB, Kapralov AA, Amoscato AA, Jiang J, Anthonymuthu T, Mohammadyani D, Yang Q, Proneth B, Klein-Seetharaman J, Watkins S, Bahar I, Greenberger J, Mallampalli RK, Stockwell BR, Tyurina YY, Conrad M & Bayir H (2017) Oxidized arachidonic and adrenic PEs navigate cells to ferroptosis, Nat Chem Biol. 13, 81–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Doll S, Proneth B, Tyurina YY, Panzilius E, Kobayashi S, Ingold I, Irmler M, Beckers J, Aichler M, Walch A, Prokisch H, Trumbach D, Mao G, Qu F, Bayir H, Fullekrug J, Scheel CH, Wurst W, Schick JA, Kagan VE, Angeli JP & Conrad M (2017) ACSL4 dictates ferroptosis sensitivity by shaping cellular lipid composition, Nat Chem Biol. 13, 91–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Magtanong L, Ko PJ, To M, Cao JY, Forcina GC, Tarangelo A, Ward CC, Cho K, Patti GJ, Nomura DK, Olzmann JA & Dixon SJ (2019) Exogenous Monounsaturated Fatty Acids Promote a Ferroptosis-Resistant Cell State, Cell Chem Biol. 26, 420–432 e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hider RC & Kong XL (2011) Glutathione: a key component of the cytoplasmic labile iron pool, Biometals. 24, 1179–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aron AT, Loehr MO, Bogena J & Chang CJ (2016) An Endoperoxide Reactivity-Based FRET Probe for Ratiometric Fluorescence Imaging of Labile Iron Pools in Living Cells, J Am Chem Soc. 138, 14338–14346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Muhlenhoff U, Braymer JJ, Christ S, Rietzschel N, Uzarska MA, Weiler BD & Lill R (2020) Glutaredoxins and iron-sulfur protein biogenesis at the interface of redox biology and iron metabolism, Biol Chem. 401, 1407–1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang S, Chang W, Wu H, Wang YH, Gong YW, Zhao YL, Liu SH, Wang HZ, Svatek RS, Rodriguez R & Wang ZP (2020) Pan-cancer analysis of iron metabolic landscape across the Cancer Genome Atlas, J Cell Physiol. 235, 1013–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang Y, Swanda RV, Nie L, Liu X, Wang C, Lee H, Lei G, Mao C, Koppula P, Cheng W, Zhang J, Xiao Z, Zhuang L, Fang B, Chen J, Qian SB & Gan B (2021) mTORC1 couples cyst(e)ine availability with GPX4 protein synthesis and ferroptosis regulation, Nat Commun. 12, 1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li J, Liu J, Xu Y, Wu R, Chen X, Song X, Zeh H, Kang R, Klionsky DJ, Wang X & Tang D (2021) Tumor heterogeneity in autophagy-dependent ferroptosis, Autophagy, 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ezerina D, Takano Y, Hanaoka K, Urano Y & Dick TP (2018) N-Acetyl Cysteine Functions as a Fast-Acting Antioxidant by Triggering Intracellular H2S and Sulfane Sulfur Production, Cell Chem Biol. 25, 447–459 e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Adelmann CH, Traunbauer AK, Chen B, Condon KJ, Chan SH, Kunchok T, Lewis CA & Sabatini DM (2020) MFSD12 mediates the import of cysteine into melanosomes and lysosomes, Nature. 588, 699–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kang YP, Torrente L, Falzone A, Elkins CM, Liu M, Asara JM, Dibble CC & DeNicola GM (2019) Cysteine dioxygenase 1 is a metabolic liability for non-small cell lung cancer, Elife. 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Park S & Imlay JA (2003) High levels of intracellular cysteine promote oxidative DNA damage by driving the fenton reaction, J Bacteriol. 185, 1942–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chonoles Imlay KR, Korshunov S & Imlay JA (2015) Physiological Roles and Adverse Effects of the Two Cystine Importers of Escherichia coli, J Bacteriol. 197, 3629–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hughes CE, Coody TK, Jeong MY, Berg JA, Winge DR & Hughes AL (2020) Cysteine Toxicity Drives Age-Related Mitochondrial Decline by Altering Iron Homeostasis, Cell. 180, 296–310 e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ji Y, Wu Z, Dai Z, Sun K, Zhang Q & Wu G (2016) Excessive L-cysteine induces vacuole-like cell death by activating endoplasmic reticulum stress and mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in intestinal porcine epithelial cells, Amino Acids. 48, 149–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shibui Y, Sakai R, Manabe Y & Masuyama T (2017) Comparisons of l-cysteine and d-cysteine toxicity in 4-week repeated-dose toxicity studies of rats receiving daily oral administration, J Toxicol Pathol. 30, 217–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Singh VK, Rahman MN, Munro K, Uversky VN, Smith SP & Jia Z (2012) Free cysteine modulates the conformation of human C/EBP homologous protein, PLoS One. 7, e34680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Muir A, Danai LV, Gui DY, Waingarten CY, Lewis CA & Vander Heiden MG (2017) Environmental cystine drives glutamine anaplerosis and sensitizes cancer cells to glutaminase inhibition, Elife. 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shin CS, Mishra P, Watrous JD, Carelli V, D’Aurelio M, Jain M & Chan DC (2017) The glutamate/cystine xCT antiporter antagonizes glutamine metabolism and reduces nutrient flexibility, Nat Commun. 8, 15074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Koppula P, Zhang Y, Shi J, Li W & Gan B (2017) The glutamate/cystine antiporter SLC7A11/xCT enhances cancer cell dependency on glucose by exporting glutamate, J Biol Chem. 292, 14240–14249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sayin VI, LeBoeuf SE, Singh SX, Davidson SM, Biancur D, Guzelhan BS, Alvarez SW, Wu WL, Karakousi TR, Zavitsanou AM, Ubriaco J, Muir A, Karagiannis D, Morris PJ, Thomas CJ, Possemato R, Vander Heiden MG & Papagiannakopoulos T (2017) Activation of the NRF2 antioxidant program generates an imbalance in central carbon metabolism in cancer, Elife. 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.LeBoeuf SE, Wu WL, Karakousi TR, Karadal B, Jackson SR, Davidson SM, Wong KK, Koralov SB, Sayin VI & Papagiannakopoulos T (2020) Activation of Oxidative Stress Response in Cancer Generates a Druggable Dependency on Exogenous Non-essential Amino Acids, Cell Metab. 31, 339–350 e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pader I, Sengupta R, Cebula M, Xu J, Lundberg JO, Holmgren A, Johansson K & Arner ES (2014) Thioredoxin-related protein of 14 kDa is an efficient L-cystine reductase and S-denitrosylase, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 111, 6964–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Reeds PJ (2000) Dispensable and indispensable amino acids for humans, J Nutr. 130, 1835S–40S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stipanuk MH (2020) Metabolism of Sulfur-Containing Amino Acids: How the Body Copes with Excess Methionine, Cysteine, and Sulfide, J Nutr. 150, 2494S–2505S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rees MG, Seashore-Ludlow B, Cheah JH, Adams DJ, Price EV, Gill S, Javaid S, Coletti ME, Jones VL, Bodycombe NE, Soule CK, Alexander B, Li A, Montgomery P, Kotz JD, Hon CS, Munoz B, Liefeld T, Dancik V, Haber DA, Clish CB, Bittker JA, Palmer M, Wagner BK, Clemons PA, Shamji AF & Schreiber SL (2016) Correlating chemical sensitivity and basal gene expression reveals mechanism of action, Nat Chem Biol. 12, 109–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tarangelo A, Magtanong L, Bieging-Rolett KT, Li Y, Ye J, Attardi LD & Dixon SJ (2018) p53 Suppresses Metabolic Stress-Induced Ferroptosis in Cancer Cells, Cell Rep. 22, 569–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang T, Bauer C, Newman AC, Uribe AH, Athineos D, Blyth K & Maddocks ODK (2020) Polyamine pathway activity promotes cysteine essentiality in cancer cells, Nat Metab. 2, 1062–1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cao J, Chen X, Jiang L, Lu B, Yuan M, Zhu D, Zhu H, He Q, Yang B & Ying M (2020) DJ-1 suppresses ferroptosis through preserving the activity of S-adenosyl homocysteine hydrolase, Nat Commun. 11, 1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhu J, Berisa M, Schworer S, Qin W, Cross JR & Thompson CB (2019) Transsulfuration Activity Can Support Cell Growth upon Extracellular Cysteine Limitation, Cell Metab. 30, 865–876 e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lu SC (2000) Regulation of glutathione synthesis, Curr Top Cell Regul. 36, 95–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lieberman MW, Wiseman AL, Shi ZZ, Carter BZ, Barrios R, Ou CN, Chevez-Barrios P, Wang Y, Habib GM, Goodman JC, Huang SL, Lebovitz RM & Matzuk MM (1996) Growth retardation and cysteine deficiency in gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase-deficient mice, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 93, 7923–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang J, Wang N, Zhou Y, Wang K, Sun Y, Yan H, Han W, Wang X, Wei B, Ke Y & Xu X (2021) Oridonin induces ferroptosis by inhibiting gamma-glutamyl cycle in TE1 cells, Phytother Res. 35, 494–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Saxton RA & Sabatini DM (2017) mTOR Signaling in Growth, Metabolism, and Disease, Cell. 168, 960–976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yu X & Long YC (2016) Crosstalk between cystine and glutathione is critical for the regulation of amino acid signaling pathways and ferroptosis, Sci Rep. 6, 30033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wolfson RL & Sabatini DM (2017) The Dawn of the Age of Amino Acid Sensors for the mTORC1 Pathway, Cell Metab. 26, 301–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gu Y, Albuquerque CP, Braas D, Zhang W, Villa GR, Bi J, Ikegami S, Masui K, Gini B, Yang H, Gahman TC, Shiau AK, Cloughesy TF, Christofk HR, Zhou H, Guan KL & Mischel PS (2017) mTORC2 Regulates Amino Acid Metabolism in Cancer by Phosphorylation of the Cystine-Glutamate Antiporter xCT, Mol Cell. 67, 128–138 e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sikalidis AK, Lee JI & Stipanuk MH (2011) Gene expression and integrated stress response in HepG2/C3A cells cultured in amino acid deficient medium, Amino Acids. 41, 159–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Harding HP, Zhang Y, Zeng H, Novoa I, Lu PD, Calfon M, Sadri N, Yun C, Popko B, Paules R, Stojdl DF, Bell JC, Hettmann T, Leiden JM & Ron D (2003) An integrated stress response regulates amino acid metabolism and resistance to oxidative stress, Mol Cell. 11, 619–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lim JKM, Delaidelli A, Minaker SW, Zhang HF, Colovic M, Yang H, Negri GL, von Karstedt S, Lockwood WW, Schaffer P, Leprivier G & Sorensen PH (2019) Cystine/glutamate antiporter xCT (SLC7A11) facilitates oncogenic RAS transformation by preserving intracellular redox balance, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 116, 9433–9442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kumar A, Tikoo S, Maity S, Sengupta S, Sengupta S, Kaur A & Bachhawat AK (2012) Mammalian proapoptotic factor ChaC1 and its homologues function as gamma-glutamyl cyclotransferases acting specifically on glutathione, EMBO Rep. 13, 1095–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Crawford RR, Prescott ET, Sylvester CF, Higdon AN, Shan J, Kilberg MS & Mungrue IN (2015) Human CHAC1 Protein Degrades Glutathione, and mRNA Induction Is Regulated by the Transcription Factors ATF4 and ATF3 and a Bipartite ATF/CRE Regulatory Element, J Biol Chem. 290, 15878–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chen MS, Wang SF, Hsu CY, Yin PH, Yeh TS, Lee HC & Tseng LM (2017) CHAC1 degradation of glutathione enhances cystine-starvation-induced necroptosis and ferroptosis in human triple negative breast cancer cells via the GCN2-eIF2alpha-ATF4 pathway, Oncotarget. 8, 114588–114602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jiang L, Kon N, Li T, Wang SJ, Su T, Hibshoosh H, Baer R & Gu W (2015) Ferroptosis as a p53-mediated activity during tumour suppression, Nature. 520, 57–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wang Y, Yang L, Zhang X, Cui W, Liu Y, Sun QR, He Q, Zhao S, Zhang GA, Wang Y & Chen S (2019) Epigenetic regulation of ferroptosis by H2B monoubiquitination and p53, EMBO Rep. 20, e47563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhang Y, Shi J, Liu X, Feng L, Gong Z, Koppula P, Sirohi K, Li X, Wei Y, Lee H, Zhuang L, Chen G, Xiao ZD, Hung MC, Chen J, Huang P, Li W & Gan B (2018) BAP1 links metabolic regulation of ferroptosis to tumour suppression, Nat Cell Biol. 20, 1181–1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhang Y, Koppula P & Gan B (2019) Regulation of H2A ubiquitination and SLC7A11 expression by BAP1 and PRC1, Cell Cycle. 18, 773–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chen D, Tavana O, Chu B, Erber L, Chen Y, Baer R & Gu W (2017) NRF2 Is a Major Target of ARF in p53-Independent Tumor Suppression, Mol Cell. 68, 224–232 e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lang X, Green MD, Wang W, Yu J, Choi JE, Jiang L, Liao P, Zhou J, Zhang Q, Dow A, Saripalli AL, Kryczek I, Wei S, Szeliga W, Vatan L, Stone EM, Georgiou G, Cieslik M, Wahl DR, Morgan MA, Chinnaiyan AM, Lawrence TS & Zou W (2019) Radiotherapy and Immunotherapy Promote Tumoral Lipid Oxidation and Ferroptosis via Synergistic Repression of SLC7A11, Cancer Discov. 9, 1673–1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hayano M, Yang WS, Corn CK, Pagano NC & Stockwell BR (2016) Loss of cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase (CARS) induces the transsulfuration pathway and inhibits ferroptosis induced by cystine deprivation, Cell Death Differ. 23, 270–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Liu N, Lin X & Huang C (2020) Activation of the reverse transsulfuration pathway through NRF2/CBS confers erastin-induced ferroptosis resistance, Br J Cancer. 122, 279–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Chen D, Fan Z, Rauh M, Buchfelder M, Eyupoglu IY & Savaskan N (2017) ATF4 promotes angiogenesis and neuronal cell death and confers ferroptosis in a xCT-dependent manner, Oncogene. 36, 5593–5608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chen Y, Mi Y, Zhang X, Ma Q, Song Y, Zhang L, Wang D, Xing J, Hou B, Li H, Jin H, Du W & Zou Z (2019) Dihydroartemisinin-induced unfolded protein response feedback attenuates ferroptosis via PERK/ATF4/HSPA5 pathway in glioma cells, J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 38, 402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Suraweera A, Munch C, Hanssum A & Bertolotti A (2012) Failure of amino acid homeostasis causes cell death following proteasome inhibition, Mol Cell. 48, 242–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gao M, Yi J, Zhu J, Minikes AM, Monian P, Thompson CB & Jiang X (2019) Role of Mitochondria in Ferroptosis, Mol Cell. 73, 354–363 e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kim Y, Sundrud MS, Zhou C, Edenius M, Zocco D, Powers K, Zhang M, Mazitschek R, Rao A, Yeo CY, Noss EH, Brenner MB, Whitman M & Keller TL (2020) Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase inhibition activates a pathway that branches from the canonical amino acid response in mammalian cells, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 117, 8900–8911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.De Vito A, Lazzaro M, Palmisano I, Cittaro D, Riba M, Lazarevic D, Bannai M, Gabellini D & Schiaffino MV (2018) Amino acid deprivation triggers a novel GCN2-independent response leading to the transcriptional reactivation of non-native DNA sequences, PLoS One. 13, e0200783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mazor KM, Dong L, Mao Y, Swanda RV, Qian SB & Stipanuk MH (2018) Effects of single amino acid deficiency on mRNA translation are markedly different for methionine versus leucine, Sci Rep. 8, 8076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kamphorst JJ, Nofal M, Commisso C, Hackett SR, Lu W, Grabocka E, Vander Heiden MG, Miller G, Drebin JA, Bar-Sagi D, Thompson CB & Rabinowitz JD (2015) Human pancreatic cancer tumors are nutrient poor and tumor cells actively scavenge extracellular protein, Cancer Res. 75, 544–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pan M, Reid MA, Lowman XH, Kulkarni RP, Tran TQ, Liu X, Yang Y, Hernandez-Davies JE, Rosales KK, Li H, Hugo W, Song C, Xu X, Schones DE, Ann DK, Gradinaru V, Lo RS, Locasale JW & Kong M (2016) Regional glutamine deficiency in tumours promotes dedifferentiation through inhibition of histone demethylation, Nat Cell Biol. 18, 1090–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ishimoto T, Nagano O, Yae T, Tamada M, Motohara T, Oshima H, Oshima M, Ikeda T, Asaba R, Yagi H, Masuko T, Shimizu T, Ishikawa T, Kai K, Takahashi E, Imamura Y, Baba Y, Ohmura M, Suematsu M, Baba H & Saya H (2011) CD44 variant regulates redox status in cancer cells by stabilizing the xCT subunit of system xc(−) and thereby promotes tumor growth, Cancer Cell. 19, 387–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Liu T, Jiang L, Tavana O & Gu W (2019) The Deubiquitylase OTUB1 Mediates Ferroptosis via Stabilization of SLC7A11, Cancer Res. 79, 1913–1924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lien EC, Ghisolfi L, Geck RC, Asara JM & Toker A (2017) Oncogenic PI3K promotes methionine dependency in breast cancer cells through the cystine-glutamate antiporter xCT, Sci Signal. 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ogiwara H, Takahashi K, Sasaki M, Kuroda T, Yoshida H, Watanabe R, Maruyama A, Makinoshima H, Chiwaki F, Sasaki H, Kato T, Okamoto A & Kohno T (2019) Targeting the Vulnerability of Glutathione Metabolism in ARID1A-Deficient Cancers, Cancer Cell. 35, 177–190 e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]