Abstract

Background

Vaccine refusal is highly polarizing in Australia, producing a challenging social landscape for non-vaccinating parents. We sought to understand the lived experience of non-vaccinating parents in contemporary Australia.

Methods

We recruited a national sample of non-vaccinating parents of children <18 yrs, advertising on national radio, in playgrounds in low vaccination areas, and using snowballing. Grounded Theory methodology guided data collection (via semi-structured interviews). Inductive analysis identified stigmatization as a central concept; stigma theory was adopted as an analytical lens.

Results

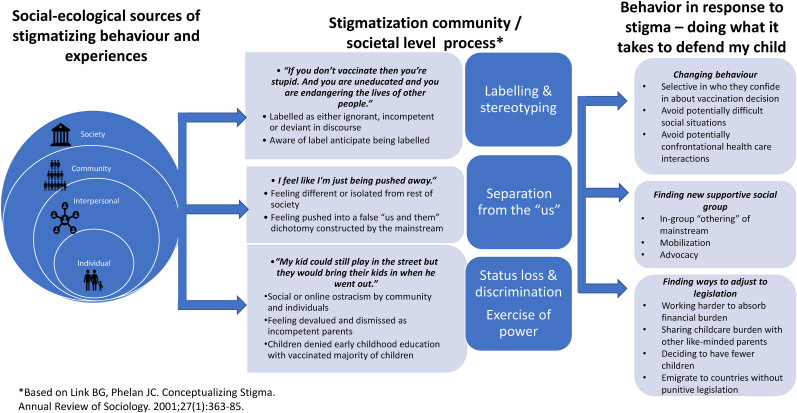

Twenty-one parents from regional and urban locations in five states were interviewed. Parent's described experiences point to systematic stigmatization which can be characterized using Link & Phelan's five-step process. Parents experienced (1) labelling and (2) stereotyping, with many not identifying with the “anti-vaxxers” portrayed in the media and describing frustration at being labelled as such, believing they were defending their child from harm. Participants described (3) social “othering”, leading to relationship loss and social isolation, and (4) status loss and discrimination, feeling “brushed off” as incompetent parents and discriminated against by medical professionals and other parents. Finally, (5) legislative changes exerted power over their circumstances, rendering them unable to provide their children with the same financial and educational opportunities as vaccinated children, often increasing their steadfastness in refusing vaccination.

Conclusion

Non-vaccinating Australian parents feel stigmatized for defending their child from perceived risk of harm, reporting a range of social and psychological effects, as well as financial effects from policies which disadvantaged their children through differential financial treatment, and diminished early childhood educational opportunities. While it might be argued that social stigma and exclusionary policies directed a small minority for the greater good are justified, other more nuanced approaches based on better understandings of vaccine rejection could achieve comparable public health outcomes without the detrimental effect on unvaccinated families.

Keywords: Australia, Immunization, Childhood vaccination, Vaccine refusal, Public health, Qualitative research, Stigma

Highlights

-

•

Australian non-vaccinating parents describe suffering stigma due to their choices.

-

•

Non-vaccinating parents' experiences align with Link & Phelan's stigma theory.

-

•

Non-vaccinating parents use various strategies to manage stigma.

-

•

Some families report detrimental effects of mandatory vaccine policy.

-

•

Mandatory vaccine policy made some more steadfast in their stance.

1. Introduction

Immunisation is a foundational element of a successful public health program, averting an estimated 2.5 million deaths yearly (Berkley et al., 2013). Despite this, some parents refuse vaccines for their children. Parents' journeys to vaccine refusal are a combination of personal experience, social influences, health beliefs and continuous risk assessment, all underpinned by a desire to protect their child (Díaz Crescitelli et al., 2020; Jennifer A. Reich, 2016; Sobo, 2015;Ward, Attwell, Meyer, & Rokkas, 2017, Wiley et al., 2020). However, public discourse constructs a simplistic “pro-” versus “anti-” vaccination dichotomy, with politicians and media commentators often disparagingly labelling vaccine refusers (Chambers, 2015; Harvey, 2015a, 2015b; Morris, 2015). Complicating the discourse is the broad and often inaccurate use of the word “hesitancy” to describe the spectrum of vaccination behaviours. “Hesitancy” is an internal psychological state that encompasses indecision but not necessarily vaccine rejection behaviour (Bedford et al., 2018). For the purposes of this study we use “non-vaccinator” to describe people who have firmly chosen to refuse vaccines for their child. The broader community often regard non-vaccinators as defective and dangerous (Rozbroj, Lyons, & Lucke, 2019), effectively “othering” vaccine refusing parents. In Australia, this combination of negative discourse, high public support for vaccination, and political will underpinned recent policy change. At both State and Federal levels, philosophical exemptions from vaccination were removed, and medical exemptions tightened. As a result, families of unvaccinated children can no longer access federal financial assistance of up to AUD$26,000 per year (Omer, Betsch, & Leask, 2019), and in some states, unvaccinated children can no longer attend early childhood education (Leask & Danchin, 2017, Stephenson et al., 2018). Nationally, Australia enjoys high and stable childhood vaccination coverage, with 95% of all five year old's fully vaccinated (Australian Government Department of Health, 2021), while around 2–3% of children remain undervaccination due to conscious vaccine rejection (Beard, Hull, Leask, Dey, & McIntyre, 2016).

A decision to not vaccinate brings both health and social risks for individuals, their children, and the community. Those who transgress social expectations regarding contagion can be subject to intense forms of stigmatization. In his seminal work Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity, Goffman describes stigma as “an attribute that is deeply discrediting”. In Goffman's terms, to be stigmatized is to live with and manage a “spoilt” social identity (Goffman, 1986).

The discrimination experienced by the stigmatized generally takes three forms: Direct (e.g. avoiding a person due to their race), structural (e.g. meeting in places that the stigmatized group cannot access to prevent them participating), and a form of modified labelling where people see that a negative label has been applied to them by others and anticipate that they will be viewed by others as somehow deviant or defective, modifying their social behaviour as a result (e.g. stigmatized people avoiding social contact with “normals”) (Link & Phelan, 2006). It is recognised that stigmatized groups form social networks of their own, often advocating for their stigmatized group (Courtwright, 2013; Goffman, 1986).

Previous research about stigmatization of non-vaccinating families is limited. Reich analyses the stigmatizing experiences of non-vaccinating mothers in Colorado, USA and examines the role of social capital in how they deal with it (Reich, 2018). Previous Australian research has touched on discrimination against non-vaccinating parents (Ward, Attwell, Meyer, Rokkas, & Leask, 2017). This paper is part of a broader study which aims to understand the lived experience of non-vaccinating Australian parents. Here we seek to explain the process by which vaccine-rejecting parents come to feel or be stigmatized and how this stigma fits into the broader lived experience of vaccine rejecting parents and their families.

Epistemically, we approach the research with a public health orientation accepting the overwhelming evidence that the benefits of vaccination far outweigh the risks. However, we also assume there is value in understanding the lifeworld of non-vaccinating parents, and that these parents should be afforded respect as citizens as well as research participants. Further, we will show that promotion of vaccination in ways that create social harms can entrench marginal positions of non-vaccinators, and so become self-undermining.

2. Methods

2.1. Sampling

We used qualitative semi-structured interviews and a grounded theory analytical approach (Charmaz, 2014) to explore the social process of childhood vaccine refusal, as expressed by parents. Described in detail elsewhere (Wiley et al., 2020), a semi-structured interview guide was developed and iteratively modified (Charmaz, 2014). Interviews were conducted via telephone, zoom or face to face, were audio-recorded, transcribed and de-identified using pseudonyms. The interview centred around three key lines of inquiry: ‘Tell me what's important to you as a parent’, ‘Tell me how you got here’ (with respect to vaccine refusal), and ‘What was influential in helping you come to your current position on vaccination?’.

We took a three-tier national-local-personal approach to recruitment, advertising nationally on radio and Facebook parenting groups; Locally in areas with known higher rates of vaccine rejection via parenting groups, libraries, playgrounds, Steiner schools and homeschooling groups; and at a personal level by passive snowballing (Atkinson & Flint, 2001).

Eligible participants were parents and carers of children under 18 years old (and are therefore subject to Federal mandatory vaccination policy), who had intentionally delayed or refused some or all the vaccines funded under the Australian National Immunisation Programme.

2.2. Coding development and data analysis

Initially, a team of six researchers independently openly coded the first three interviews, and then met to discuss and agree on initial codes. In this inductive phase, we quickly observed descriptions of stigmatization in parental accounts. Thus, for this analysis we interrogated the social science literature on stigmatization and specifically used Link and Phelan’s (2001) five-step process described below. Further inductive analysis identified that parent's experiences related to different levels of society. We similarly used the social ecological model to help orient their described experiences in their social world (White Hughto, Reisner, & Pachankis, 2015). A second coding triangulation exercise was undertaken by the research team after the next seven interviews, to ensure methodological rigour, and the remaining cycles of data collection and analysis were undertaken by a single researcher (KW). Throughout the entire research process detailed researcher memos were kept, enabling continuous critical reflection of the researcher's own positions in relation to the subject, ensuring reflexivity in the analysis and interpretation of the data. We set out to employ theoretical sampling, however non-vaccinating parents are a small population in Australia and recruitment was challenging due to issues of trust. We therefore interviewed every parent recruited resulting in a purposive, rather than theoretical sample, the analysis of which was guided by Charmaz (Charmaz, 2014).

2.3. Theoretical underpinning of abductive/inductive analysis

The iteration between inductively derived concepts and existing theory is consistent with abductive analytic processes described in grounded theory methodology (Reichertz, 2007). Here we describe the theory that underpinned the analytical process.

2.3.1. The components of stigma

Building on Goffman's work, Link & Phelan conceptualise stigma as arising from five interrelated components. The first components are labelling and stereotyping. Labelling involves allocation to socially selected categories that signify a salient difference to the social majority (for example, race or HIV status), while stereotyping occurs when the labelled person is associated with undesirable characteristics. (Link & Phelan, 2001). The next component in Link and Phelan's stigma process is separation: when the social majority who apply the undesirable labels “other” the stigmatized group, setting them apart from the majority. Status loss occurs when those who are labelled and othered are devalued in the social hierarchy, and ultimately suffer discrimination as a result. Finally, The exercise of power is when the social majority, as a result of the preceding processes, have power1 over the “othered” group (Link & Phelan, 2001, 2006).

Following the initial inductive open coding that identified descriptions of stigmatization, codes were grouped according to the components of stigma described by Link and Phelan.

2.3.2. Responding to stigmatization

Goffman's essays on stigma cover how the stigmatized manage its effects by controlling the information that marks them as different by not disclosing discrediting information, or “passing”. Those with a stigmatizing attribute that is not visible may choose not to divulge this information to others, pretending to be a member of the dominant non-stigmatized group. Similarly, they may change their behaviour to avoid detection or minimise possibly uncomfortable interactions. Goffman also discusses group alignment; the tendency to form in-groups with others who share the same stigma and suffer the same inequalities (Goffman, 1986).

This theoretical concept of stigma management was also used to organise the codes inductively identified from the data.

2.3.3. The sources of stigmatizing experiences

The experiences and actions described by parents were complex and covered a range of interactions with different aspects of society. The social ecological model (McLeroy, Bibeau, Steckler, & Glanz, 1988) offered a salient way of categorizing the sources of these experiences according to the individual, interpersonal/social, community and society spheres of the model, and was previously used to characterize stigma according to how it is experienced by transgender people (White Hughto et al., 2015).Thus, we used a combination Link & Phelan's five step process and the Social Ecological Model as analytical tools to develop a mid-range theory describing how Australian non-vaccinating parents experience stigmatization.

3. Ethical approval

This study was approved by the University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee, approval number 2017/500. Written informed consent to participate was obtained from all participants following receipt of transparent and standardized information about the study aims and procedures.

4. Results

Twenty-two interviews were conducted with parents from five of Australia's eight states and territories between September 11th, 2017 and February 20th, 2019. One participant later withdrew, leaving twenty-one interviews included in the analysis. Participants were mainly mothers (there was one father and one parent who did not want their gender identified). Parents' ages ranged from mid- 30s to mid-50s, and they had between one and six children, ranging in age from 9 months to 33 years old. All had at least one child 18 years old or younger at time of interview. Interviews lasted between 37 min, and 2 h 7 min.

4.1. Overview

All of the parents in our study shared their lived experience as non-vaccinating caregivers in Australia, and all spoke about processes of stigmatization and how they managed this. In summary, consistent with Link and Phelan's theorisation, parents described being labelled and stereotyped, which facilitated their separation from the ‘mainstream’, leading to loss of status and discrimination. Parents described engaging a set of behaviours and social processes to defend their child and themselves against this stigmatization and its effects. Below, we present analysis and evidence to illustrate each component of this complex social process.

4.2. Labelling and stereotyping: “I'm not really anti-vaxx”

All participants had experienced labelling and stereotyping in line with the first steps in Link and Phelan's process. There was, however, an additional complication for many of these parents. A number of participants made a strong distinction between themselves and ‘anti-vaxxers’ and felt that they had been mislabelled as such. For these parents, the ‘anti-vaxx’ label was associated with a range of stereotypical attributes which included ‘alternative lifestyle choices’ such as home schooling and dressing and eating differently. Some parents were at pains to distance themselves from these attributes:

“It's not like … I'm a hippie …. I don't know any of these people that live in Byron Bay, and they just go “no” because it's a chemical and [they] eat organic food. And I don't know any of those people. They're not in my circle.”

Sally

Stereotypical anti-vaccinators were associated with blameworthy behaviours or character traits, including being irresponsible or dangerous, and these parents were keenly aware of the stereotypical labels their vaccination decisions would attract:

“I feel I know that they're just going to say I'm a terrible parent and I'm killing babies.”

Jenny

Matilda was “bothered by the fact that people have been labelled as conspiracy terrorists …. ”, and Sally felt that others “make out that anyone that doesn't vaccinate is mean and nasty and is wanting to cause havoc on the world.”

While some framed their position by rejecting alignment with a stigmatized group, others framed their position as their desire for health, rather than in opposition to vaccine. They wanted agency to take responsibility for their child's health and safety in the way they saw fit. Matilda described herself as “more pro-choice”, a term commonly used by non-vaccinators to convey the reason for their position, while some parents like Josephine accepted some aspects of the stereotypical label:

“If the two sides are pro-vaxx and anti-vaxx, I probably sit a little bit more on the anti-vaxx side, if you like. But I'm not anti it, it's just more, I want to be able to choose what and when.”

Josephine

In keeping with modified labelling theory, parents described anticipating how they would be labelled and treated by the vaccinating majority, especially in a healthcare setting, with some modifying their behaviour accordingly. Claire described being “a bit fearful that they might refuse to treat us or something like that”, while Emma related how vaccination made attending to her daughter's broken arm more stressful as she feared being asked about it at the hospital and then being pressured to vaccinate. Anne spoke of people just avoiding medical encounters altogether as a result of the anticipated threat:

“You don't want to go there, because you know you're going to get a lecture about immunisation, so you don't go and get the help that might actually be helpful for you. And I know this is the case for a number of other families, because they just don't want to have that conversation again. They've made their decision. They don't want to go down that role of being told that they're a bad mother”

Anne

4.3. Separation from the “mainstream”: feeling different, isolated or outcast because of their choices

Most parents in this study felt they were not accepted as part of mainstream society because of their choice. Matilda felt as though she was “looked at as weird and dangerous even”. Some felt exclusion: “I don't fit in with any group anywhere” (Nichola), and others, like Elizabeth described feeling alienated: “[I feel] excluded from society, and an outcast, basically … …The more society outcasts me for my decision, the more I find it hard to come to their point of view. So I feel like I'm just being pushed away.”

Elizabeth also spoke of this separation from the mainstream collective as being experienced by her children. She related her son's experience with a school-based vaccination program, “When the school did the rubella vaccinating, and I opted out of that obviously, and [her son's] teachers rolled their eyes at him. So it's not fair to be branded with a scarlet letter.”

On a broader level, some parents spoke of the mainstream discourse as unyielding and polarising, describing feeling pushed into a false dichotomy, either categorizing them as a deviant danger to society, or “normal”, when in fact they experienced themselves as negotiating a spectrum which was not recognised.

“[P]eople make an assumption that …. “You're an anti-vaxxer” or “You're a pro-vaxxer.” Like, you've got to be one camp or the other … I actually think that that there might be some hard-core anti-people out there - I haven't met them - but I think a lot of us are actually in this middle ground”

Eloise

4.4. Status loss and discrimination at an interpersonal level

On an inter-personal level, parents described status loss in terms of their perceived mental and parental competence. This led to a perceived diminished validity of their concerns and opinions, and removal of their right to question vaccines, particularly in a medical setting. Elizabeth described vaccine-rejecting parents as “being brushed off and being dismissed and being treated like they're crazy”. This sentiment was echoed by a number of participants like Nichola, who spoke of a “big shutting down of even asking a simple question” because “they brush it off …. they treat unvaccinated children – their parents like they're stupid.” Parents like Anne described being made to feel that their concerns are not valid as a result

“To me the sense of not being listened to in the first place, that your views or your concerns are not valid in any way”

Anne

Many parents described feeling this loss of status as a competent parent most keenly in interactions with medical professionals. The word “judgement” was used by many parents. Julie said, “[i]t is judgement. It's, you know, you did this to your child”, when describing having to take her unwell unvaccinated child for medical attention. Sally spoke of negative experiences with different medical professionals, saying “I find that the most discrimination comes from your GP when you raise it with them.” Even when deciding to delay vaccines, parents describe having to negotiate perceived differential treatment from healthcare providers. Eloise described feeling the need to placate immunisation nurses so that her son would be treated normally “I've had to kind of charm them into being kind to my son.” – Eloise.

Some parents like Jessica sought new health care providers following negative encounters:

“[W]e had some very negative experiences with aggressive and patronising, and almost harassing, doctors”

Jessica

For many, status loss and moral judgement extended beyond uncomfortable interactions, to outright ostracism. Parents described exclusion from parent and friend groups, as well as from family. Jay experienced overt exclusion by family:

“I lost contact with family members because of it …. . I got harassed by a bunch of cousins …. and I found out that a whole bunch of them had started a group, a secret group, and were bitching about me.”

Jay

Matilda related how after her daughter's vaccination status became known in a parent group, she watched her daughter become “ostracized afterwards, because it's almost like she was already sick or something, and you can see how all of a sudden parents get very cautious about if their children play with her”. Emma and her son experienced social exclusion because of her decision

“The mothers in our street had a meeting and they decided that they didn't want their kids to play with him because he wasn't vaccinated …. I wasn't really prepared for them all to come to my doorstep, so I was upset … My kid could still play in the street, but what would happen is that they would bring their kids in when he went out.”

Emma

4.5. Status loss and discrimination at a systemic level

Parent's described experiences showed that the micro-level interactions that point to status loss and discrimination at an interpersonal level are reinforced by similar patterns at a macro-level. They perceived the labelling and status loss expressed in discourse as symptomatic of a kind of sanctioned large-scale bullying. Some saw this discourse as being driven by the government, the media, or both. Elizabeth felt that non-vaccinating parents were afforded treatment that wouldn't be tolerated for any other group. “All of that government, politicians, the way they speak about people that don't vaccinate– there's no other population group is allowed to be bashed that much.”

Nichola expressed similar sentiments:

“[W]hen I see headlines …. “Pig Headed Parents Who Refuse to Vaccinate.” That's okay to print, but can you imagine if they put … “Pig Headed Fat People Who Refuse to Lose Weight,”? There would be an uproar. But because it's parents who don't vaccinate, it's suddenly deemed okay”

Nichola

In these parents’ accounts, systemic status loss was experienced as differential treatment of their families, through policies excluding unvaccinated children from early childhood education and federal financial assistance. Some of the parents described suffering financially under the federal “No Jab No Pay” policy, combined in some states with the loss of access to childcare services.

Some parents explicitly said they felt the policies are unethical and discriminatory, pointing to perceived social injustices. Sally said she “would really like [her child] to be able to go to a childcare centre where she's with other children, but [she] can't do that …. It is discriminatory.” Eloise felt that the policies affected people with lower incomes differently: “if you're wealthy, you can make these decisions yourself, but if you're not wealthy, you have no choice”.

4.6. Responding to stigmatization: doing what it takes to defend my child

The parents in this study described several stigma management strategies that connect to Goffman's work, including changing their behaviour or their health care practitioner to avoid negative interactions and finding like-minded families, thus accessing reinforcement and social support for their decision. Finally, they described the practical ways they were able to counter the negative effects of Australia's mandatory vaccination policies, such that they could continue what they felt was the right course of action when it came to vaccine refusal for their children.

Having experienced judgement or discrimination, and/or fearing the ramifications of being “outed” as a non-vaccinator, parents spoke of adjusting their approach to inter-personal engagement about vaccination, being very careful about who they tell about their decision, and in some circumstances undertaking a form of Goffman's “passing” by not divulging this information at all. Elizabeth said she doesn't talk about vaccination “outside my safe circles”, and Josephine “wouldn't dare open my mouth to discuss how we've approached things … ….it's not the kind of topic you can talk about openly without someone tearing you to shreds.” Similarly for Jessica,

“This is not a table conversation we have … I'm much more careful about who I would talk to about things. I'm much more cautious about what I share.”

In some cases, avoidance of the topic in certain company extended to avoiding certain social interactions altogether. Nichola avoided friends and cousins who she believed would not let her unvaccinated child near them, “I'm thinking … none of us are vaccinated, so we'll just stay away”.

4.7. Finding new supportive social groups

Some parents sought new, supportive social contacts, as Elizabeth described, “safe circles” of “people that won't instantly change the way they speak to you if you question vaccines.”

New peers who were supportive or accepting of their choices in a few cases helped activate and mobilise parents to be more proactive in their non-vaccinating stance. Jane spoke of aligning herself with a new group of friends who “just have the same values” because she felt she was not accepted as part of mainstream society,

“I feel that in all of the like-minded people that I associate with now, it feels as though we have to form our own little groups, because it feels like we're not even welcome in society.”

Jane

Jane then went on to say that she felt forcing people “underground into their own little communities” was “dangerous” because it meant they inhabited an “echo chamber,” limiting exposure to perspectives different from their own.

Relatedly, some participants described reacting to the more stringent government policies by doubling down on their resolve and becoming more vocal and engaged with like-minded people. In these instances, rather than seeking to ‘pass’ and avoid stigma, parents became more public about their vaccine rejection.

“After they [the government] came in and they were pushing No Jab No Play …. .I've become a lot more active. I post stuff on Facebook and I try and convince people …. Before No Jab No Pay, I didn't know anyone else that chose not to vaccinate, not one person.”

Jay

Aligning with other research findings (Helps, Leask, & Barclay, 2018), many parents in this study preferred to work harder to cover the costs borne under Australia's new mandatory vaccination policies, rather than go against their better judgement about vaccinating. Several described considering longer-term scenarios: Jane considered finding other non-vaccinating parents for home schooling, while Jay reconsidered having more children due to the financial hardship from full childcare fees. Nichola went so far as to consider moving overseas to avoid her children being denied early childhood education.

Other participants were less affected by the policy changes, either because their incomes were beyond what qualifies for financial assistance, or because they lived in states that still permitted enrolment in childcare for unvaccinated (“I pay all the fees, but that's fine” – Jessica). A small number said that the policies ultimately convinced them to vaccinate against their better judgement.

“I had to [vaccinate her child]. It's not my choice. I have no family down here that I can get to help me out.”

Josephine

4.8. Drawing it all together: the lived experience of a non-vaccinating parent as a process of stigmatization

The self-described experiences of non-vaccinating parents in the current Australian context carry the hallmarks of a process of stigmatization as described by Link & Phelan.

Parents described a process of being labelled and stereotyped as “anti-vaxxers”, with some explicitly distancing themselves from the stereotypical “hippie” non-vaccinating parent. Public depictions of non-vaccinating parents are often derogatory, conveying negative characteristics linked to known stereotypes.

Stigma theory would suggest the linking of labels to undesirable attributes becomes the rationale for the mainstream to “other” non-vaccinating parents (Link & Phelan, 2001). Consistent with this, parents described separation from the “mainstream”, using words like “excluded”, “alienation”, “outcast” and “ostracized”.

Furthermore, parents described feeling that their opinions and questions were brushed off and dismissed as not valid. These experiences combined with experiences of ostracism demonstrate the status loss and discrimination steps of the stigmatization process. On a broader community and societal level, parents experienced denial of access to early childhood education with the vaccinated majority, and denial of federal government financial assistance as macro-level expression and reinforcement of this “othering”.

Applying the social ecological model (McLeroy et al., 1988) to the parent's described experiences highlights that the stigma experienced by non-vaccinating parents occurs systemically, cross-cutting all levels of society, and that their responses mirror these. On an interpersonal level, parents described negative attitudes from family or friends, uncomfortable interactions with health professionals, and exclusion from friend and family groups. In keeping with Link & Phelan's proposal that the stigmatized recognize that they've been labelled and anticipate the stereotype (Link & Phelan, 2006), participants adjusted their behavior accordingly by limiting who they divulged their vaccination decision to, and in some cases completely avoiding social situations where they felt the issue might cause difficulties. At the community level, parents described online and social ostracism by community groups such as play groups and neighborhood gatherings. Some parents reported joining or forming their own groups, an in-grouping that led in some cases to more vocal advocacy for their position. At the societal level, parents spoke of the disparaging attitudes toward non-vaccinating parents in the media and general discourse, and legislation and policy that excludes them from benefits and services available to the vaccinating majority. Their reaction to this was to look for ways to work around the legislation, or to simply endure it (see Fig. 1.).

Fig. 1.

Emergent Theory of stigmatization of non-vaccinating parents.

5. Discussion

The findings of this study suggest that non-vaccinating Australian parents experience a social process of stigmatization, the origins of which crosscut all levels of society. From very early in the data collection and analysis process the experiences parents described echoed the observations of Goffman (Goffman, 1986). As analysis progressed we made connections to the process set out by Link & Phelan (Link & Phelan, 2001) eventually developing a mid-range theory of the social process of stigmatization experienced by non-vaccinating parents in contemporary Australia. The crosscutting origins of the stigmatizing experiences suggest that such stigma has both emerged from and contributed to media framings and policy interventions.

Our findings also align with Carpiano & Fitz, 2017 study of attitudes of the broader public toward childhood undervaccination (Carpiano & Fitz, 2017). They tested 1469 people's responses to randomly assigned vignettes describing mothers who did and did not vaccinate their children. They found that participants negatively evaluated mothers who do not vaccinate, not wanting to be friends, and sanctioning legal and social discrimination, including restrictive mandatory policies. Crucially, Carpiano and Fitz's participants directed stronger social distancing toward the unvaccinated child than their mother, and those who imposed harsher judgement on mothers supported more punitive government policies. In light of Carpiano and Fitz's findings, the harsh judgement afforded to non-vaccinating parents in the Australian context may explain the apparent strong public support for more punitive policies (Maiden, 2015). Early findings the public health benefits of Australian mandatory vaccination policy suggest a marginal overall increase in vaccination rates (Hull, Beard, Hendry, Dey, & Macartney, 2020), but these need to be carefully assessed against other social consequences such as children being denied early childhood education and families suffering financial burden.

Our findings demonstrate that many Australian non-vaccinating parents found ways to prevail, despite tightened restrictions and overt social pressure, as have non-vaccinating parents in other countries with mandatory vaccine policies (Tomljenovic, Bubic, & Hren, 2020) In some cases, their experiences of stigmatization made them more steadfast in their position, a finding supported by previous Australian studies (Helps, Leask, & Barclay, 2018, Ward, Attwell, Meyer, & Rokkas, 2017) and consistent with broader research on psychological reactance (Betsch & Böhm, 2015). Also, this study's non-vaccinating parents sought out likeminded parents, joining or forming social groups with shared values, norms and identity. In some cases they avoided attending healthcare, and – if available – sought less stigmatizing health professionals. Others have demonstrated that non-vaccinating parents use in-person and online social networks to create social capital (Attwell, Meyer, & Ward, 2018), which they use to manage stigma (Attwell, Smith, & Ward, 2018, Reich, 2018).

Why should we care that a small number of people feel stigmatized when protecting society's most vulnerable from a preventable disease? Denormalization has historically been used in public health, including in tobacco control and vaccination communications (Bayer, 2008). A simple utilitarian perspective might consider this as permissible to maximize the health of many through vaccination, even at the expense of the choice or even wellbeing of a few (Courtwright, 2013). This most certainly appears to be the manifest argument justifying the legislative changes brought about in Australia.

Our findings on the combined impact of social stigma and restrictive mandatory policies on children are particularly important. The parents in our study describe vaccine refusal-related stigma being borne by their children, some of whom are shunned by peers at the direction of their parents and who's families are excluded from social circles with vaccinating families. They are subject to policies which deny them access to early childhood education, and those who are eligible are denied access to the financial support that vaccinated children enjoy. These potential harms of stigmatizing and excluding non-vaccinating families take us to Bayer's proposed questions to evaluate the justifiability of the use of stigma in public health policy: what is the evidence for the negative effects of the behavior concerned, what is the evidence that stigma will change that behavior, what is the severity and duration of the suffering of the stigmatized, and what is the distribution of that suffering (Bayer, 2008)? With respect to harms caused by vaccine refusal, there is a risk that vaccine preventable diseases will increase if fewer people vaccinate. However, in answer to Bayer's second question, regarding the evidence that stigma and exclusion will increase vaccination: our study adds to a growing body of evidence that while social stigma and punitive policy forces some to vaccinate, for many parents it will not. Data from California and Australia suggests many will find policy workarounds, and that refusal may become more entrenched (Delamater et al., 2019, Helps, Leask, & Barclay, 2018, Omer, Betsch, & Leask, 2019, Wiley et al., 2020). Where impacts are seen, they are likely to come from less punitive elements of vaccination requirements. Data on changes to vaccination coverage following the introduction of No Jab No Pay legislation in Australia show increases in the third doses of diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccine but a drop in primary dose of measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine (Hull et al., 2020). Hence, families who were late for vaccinations were more sensitive to the policy than those who had not commenced MMR. This suggests the effective policy lever was more likely to be a more frequent application of the existing requirements for up-to- date vaccination, rather than a removal of objector exemptions. Furthermore, this coverage increase was larger in children of lowest socio-economic status that higher status (29.1% v 7.6%) showing socioeconomic disparities in how the policy affected families.

Deliberately non-vaccinated children make up 1–2% of the total population in Australia. In areas without concentrations of non-vaccinating parents, this proportion is marginal to the success of herd immunity for most vaccinations, and thus even if all these families were successfully forced to vaccinate under punitive policy, there may be limited resulting benefit. In areas where non-vaccinating parents are concentrated, further entrenching a non-vaccinating identity has the potential for significant unintended negative consequences. Third, we found clear evidence of the detrimental social effects suffered by unvaccinated children because of the stigmatization of they experienced, and fourth, we have cited evidence that these harms are stronger for children themselves (who do not choose) than their parents (who do). While we acknowledge that the punitive policies in Australia are not themselves explicitly tools of stigma, they were implemented into a setting of active social stigmatization of unvaccinated children and their families, and by their exclusionary nature they participate in creating the stigmatic environment experienced by unvaccinated children. This raises questions about whether the current use of exclusion as an Australian public health policy tool in an already stigmatizing social environment meets Bayer's specific criteria for justification.

So, what can be done to encourage vaccination at a population level without it being at the expense of the wellbeing of a small minority of children? A closer look at their parent's motivations for refusing vaccination reveals a wide variation in how and why they arrived at their current position, (Wiley et al., 2020) and a high degree of responsibilization, evidenced by parents carefully researching and navigating risks (Díaz Crescitelli et al., 2020, Ward, Attwell, Meyer, Rokkas, & Leask, 2017). The current polarized social climate around vaccination in Australia and the resulting legislative changes essentially mean that these parents find themselves in an adversarial position. They feel compelled to defend their children from being forced into vaccination, because they believe it would be detrimental to their child's health. Is it possible to consider different public health approaches that don't rely on exclusion?

The Social Ecological Model (McLeroy et al., 1988) may assist with a solution. At the interpersonal and community levels, efforts are being made to help clinicians approach vaccine refusal with new tools that facilitate respectful encounters for both parent and provider (Berry et al., 2018). If this work succeeds, it should directly address some of the behaviours described in the current study (for example being stereotyped by, and thus avoiding, healthcare services). To complement this, additional tools may be required to foster a better understanding of non-vaccination at a community level. The aim here would be to provide and promote an alternative to the current dichotomous discourse based on stereotypes, and to help facilitate respectful and less stressful social interactions between vaccinating and non-vaccinating friends and family members. At a community level, such tools could be used to foster better understanding among public figures, politicians and media in how to handle non-vaccination more constructively in the public sphere, for example guidance for public communicators on how to talk about the issue of non-vaccination. Guidance could also be developed for vaccinating and non-vaccinating members of the community alike to facilitate respectful interactions, both online and in person.

There are some limitations to our study. We experienced censorship of our recruitment materials online, and our physical recruitment posters were defaced with profane pro-vaccine messages, photographs of which were then shared online. This may have discouraged some non-vaccinating parents from participating. Furthermore, we became aware that our recruitment material had been shared online among some of the more active anti-vaccine groups with advice not to participate for fear that we would use their information to find ways to force them to vaccinate their children. Many of the parents who did participate did not share demographic information for fear of being publicly identified. Therefore, while we were able to interrogate a range of views and experiences to saturation, it is possible that other groups who may have had slightly different views were not captured because they were discouraged from participating. Our recruitment challenges could inform the design of future studies and should draw on broader research with other hard to reach populations (Ellard-Gray, Jeffrey, Choubak, & Crann, 2015).

Analytical quality was ensured through our use of multiple coding triangulation exercises and reflexive analysis. We received affirming comments from participants and other non-vaccinating parents upon sharing a summary of our findings, confirming their resonance and authenticity.

6. Conclusion

The self-described lived experience of non-vaccinating parents in Australia demonstrates a process of stigmatization that is felt from all levels of society. This stigmatization strengthened the resolve of many of the parents in our study, to maintain their position and seek social networks that are supportive of their vaccine decisions. It generally did not make these parents change their minds, and their children were thus disadvantaged due to differential social treatment, while exclusionary policies meant they also suffered differential financial treatment, and diminished early childhood educational opportunities. While it could be argued that stigmatizing and excluding a very small minority to protect the greater public from preventable diseases is justified, other more nuanced approaches based on better understandings of vaccine rejection could achieve the same public health outcomes without the detrimental effect on unvaccinated children. The methods to achieve high vaccination rates should not excessively compete with the ultimate goal that vaccinating children seeks to serve - of health and wellbeing.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee, approval number 2017/500. Written informed consent to participate was obtained from all participants.

Funding

This study was supported by the Australian Health and Medical Research Council, Grant number APP1126543. The funding body had no role in the conduct of the research, analysis or reporting of the results.

Author statement

Kerrie E Wiley: Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Project administration. Julie Leask: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Katie Attwell: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. Catherine Helps: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. Lesley Barclay: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Paul R Ward: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition Stacy M Carter: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have no interests to declare.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Dr Chris Degeling for his advice and support during the execution of this project and Dr Penelope Robinson for her support with recruitment and project management.

Footnotes

Here we use Major et al.'s definition as “a relational ability to obtain desired ends against resistance from others ”(Major et al., 2018).

References

- Atkinson R., Flint J. Accessing hidden and hard-to-reach populations: Snowball research strategies. Social Research Update. 2001;33(1):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Attwell K., Meyer S.B., Ward P.R. The social basis of vaccine questioning and refusal: A qualitative study employing Bourdieu’s concepts of “capitals” and ‘habitus. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2018;15(5):1044. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15051044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attwell K., Smith D.T., Ward P.R. The Unhealthy Other’: How vaccine rejecting parents construct the vaccinating mainstream. Vaccine. 2018;36(12):1621–1626. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.01.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Australian Government Department of Health Childhood immunisation coverage. 2021. https://www.health.gov.au/health-topics/immunisation/childhood-immunisation-coverage Retrieved from.

- Bayer R. Stigma and the ethics of public health: Not can we but should we. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67(3):463–472. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beard F.H., Hull B.P., Leask J., Dey A., McIntyre P.B. Trends and patterns in vaccination objection, Australia, 2002–2013. Medical Journal of Australia. 2016;204(7) doi: 10.5694/mja15.01226. 275–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedford H., Attwell K., Danchin M., Marshall H., Corben P., Leask J. Vaccine hesitancy, refusal and access barriers: The need for clarity in terminology. Vaccine. 2018;36(44):6556–6558. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkley S., Chan M., Elias C., Fauci A., Lake A., Phumaphi J. Global vaccine action plan 2011-2020. 2013. https://www.who.int/immunization/global_vaccine_action_plan/GVAP_doc_2011_2020/en/ Retrieved from. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Berry N.J., Danchin M., Trevena L., Witteman H.O., Kinnersley P., Snelling T., Leask J. Sharing knowledge about immunisation (SKAI): an exploration of parents’ communication needs to inform development of a clinical communication support intervention. Vaccine. 2018;36(44):6480–6490. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.10.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betsch C., Böhm R. Detrimental effects of introducing partial compulsory vaccination: Experimental evidence. The European Journal of Public Health. 2015;26(3):378–381. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckv154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpiano R.M., Fitz N.S. Public attitudes toward child undervaccination: A randomized experiment on evaluations, stigmatizing orientations, and support for policies. Social Science & Medicine. 2017;185:127–136. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers G. Risky hippie hotbeds of anti-jab agitation: Steiner schools promote choice of parents to vaccinate children. Daily Telegraph. 2015 https://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/news/nsw/risky-hippie-hotbeds-of-antijab-agitation-steiner-schools-promote-choice-of-parents-to-vaccinate-children/news-story/025a07b06fb7bcb30cef7c48a46f299b 13 April 2015. Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. 2nd ed. sage; 2014. Constructing grounded theory. [Google Scholar]

- Courtwright A. Stigmatization and public health ethics. Bioethics. 2013;27(2):74–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8519.2011.01904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delamater P.L., Pingali S.C., Buttenheim A.M., Salmon D.A., Klein N.P., Omer S.B. Elimination of nonmedical immunization exemptions in California and school-entry vaccine status. Pediatrics. 2019;143(6) doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz Crescitelli M.E., Ghirotto L., Sisson H., Sarli L., Artioli G., Bassi M.C.…Hayter M. A meta-synthesis study of the key elements involved in childhood vaccine hesitancy. Public Health. 2020;180:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2019.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellard-Gray A., Jeffrey N.K., Choubak M., Crann S.E. Finding the hidden participant:solutions for recruiting hidden, hard-to-reach, and vulnerable populations. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 2015;14(5) doi: 10.1177/1609406915621420. 1609406915621420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. First Touchstone edition. Simon & Schuster Inc; New York, New York: 1986. Stigma : Notes on the management of spoiled identity. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey C. Claire Harvey: Anti-vaxers, you are baby killers. Daily Telegraph. 2015 https://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/news/opinion/claire-harvey-antivaxers-you-are-baby-killers/news-story/fcf1059249cca36d52a4104f2b7a880a 21 March 2015. Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey C. Claire Harvey: The Sunday Telegraph has scored a massive victory in our vaccination campaign. Daily Telegraph. 2015 https://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/news/opinion/claire-harvey-the-sunday-telegraph-has-scored-a-massive-victory-in-our-vaccination-campaign/news-story/86152843bbd1f3cd4f3428183e6c8516 11 April 2015. Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Helps C., Leask J., Barclay L. It just forces hardship”: impacts of government financial penalties on non-vaccinating parents. Journal of Public Health Policy. 2018 doi: 10.1057/s41271-017-0116-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull B.P., Beard F.H., Hendry A.J., Dey A., Macartney K. “No jab, no pay”: Catch‐up vaccination activity during its first two years. Medical Journal of Australia. 2020;213(8):364–369. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leask J., Danchin M. Imposing penalties for vaccine rejection requires strong scrutiny. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 2017;53(5):439–444. doi: 10.1111/jpc.13472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link B.G., Phelan J.C. Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology. 2001;27(1):363–385. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.363. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Link B.G., Phelan J.C. Stigma and its public health implications. The Lancet. 2006;367(9509):528–529. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68184-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiden S. Galaxy poll: 86 per cent of Australians want childhood vaccination to be compulsory. The Sunday Telegraph. 2015 https://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/news/nsw/galaxy-poll-86-per-cent-of-australians-want-childhood-vaccination-to-be-compulsory/news-story/f2e28cb872079e11969f2599b491bebd Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Major B., Dovidio J.F., Link B.G., Lucas J., Ho H.-Y., Kerns K. In: The Oxford handbook of stigma, discrimination, and health. Major B., Dovidio J.F., Link B., editors. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2018. Power, status, and stigma: Their implications for health. [Google Scholar]

- McLeroy K.R., Bibeau D., Steckler A., Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education Quarterly. 1988;15(4):351–377. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris F. Tony Abbott announces 'no jab, no pay' policy. Australian Financial Review. 2015 https://www.afr.com/politics/federal/tony-abbott-announces-no-jab-no-pay-policy-20150412-1mjc4f 13 April 2015. Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Omer S., Betsch C., Leask J. Mandate vaccination with care. Nature. 2019;571:469–472. doi: 10.1038/d41586-019-02232-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich J.A. Of natural bodies and antibodies: Parents' vaccine refusal and the dichotomies of natural and artificial. Social Science & Medicine. 2016;157:103–110. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich J.A. “We are fierce, independent thinkers and intelligent”: Social capital and stigma management among mothers who refuse vaccines. Social Science & Medicine. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichertz J. In: The SAGE handbook of grounded theory. Bryant A., Charmaz K., editors. SAGE Publications; London: 2007. Abduction: The logic of discovery in grounded theory; pp. 214–228. [Google Scholar]

- Rozbroj T., Lyons A., Lucke J. The mad leading the blind: Perceptions of the vaccine-refusal movement among Australians who support vaccination. Vaccine. 2019;37(40):5986–5993. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobo E.J. Social cultivation of vaccine refusal and delay among Waldorf (steiner) school parents. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 2015;29(3):381–399. doi: 10.1111/maq.12214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson N., Chaukra S., Katz I., Heywood A. Newspaper coverage of childhood immunisation in Australia: A lens into conflicts within public health. Critical Public Health. 2018;28(4):472–483. [Google Scholar]

- Tomljenovic H., Bubic A., Hren D. Decision making processes underlying avoidance of mandatory child vaccination in Croatia – a qualitative study. Current Psychology. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s12144-020-01110-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward PR, Attwell K, Meyer SB, Rokkas P. Understanding the perceived logic of care by vaccine-hesitant and vaccine-refusing parents: A qualitative study in Australia. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0185955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward P.R., Attwell K., Meyer S.B., Rokkas P., Leask J. Risk, responsibility and negative responses: a qualitative study of parental trust in childhood vaccinations. Journal of Risk Research. 2017:1–14. doi: 10.1080/13669877.2017.1391318. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- White Hughto J.M., Reisner S.L., Pachankis J.E. Transgender stigma and health: A critical review of stigma determinants, mechanisms, and interventions. Social Science & Medicine. 2015;147:222–231. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley K.E., Leask J., Attwell K., Helps C., Degeling C., Ward P., Carter S.M. Parenting and the vaccine refusal process: a new explanation of the relationship between lifestyle and vaccination trajectories. Social Science and Medicine. 2020;263:113259. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]