Abstract

Objectives:

To evaluate the diagnostic accuracy using sodium iodide (NaI) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as contrast agent in cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) scanning, and compare this with micro-CT.

Methods:

18 teeth were cracked artificially by soaking them cyclically in liquid nitrogen and hot water. After pre-treatment with artificial saliva, the teeth were scanned in four modes: CBCT routine scanning without contrast agent (RS); CBCT with meglumine diatrizoate (MD) as contrast agent (ES1); CBCT with NaI + DMSO as contrast agent (ES2); and micro-CT (mCT). The number of crack lines was evaluated in all four modes. Depth of crack lines and number of cracks presented from the occlusal surface to the pulp cavity (Np) in ES2 and micro-CT images were evaluated.

Results:

There were 63 crack lines in all 18 teeth. 45 crack lines were visible on ES2 images as against four on the RS and ES1 images (p<0.05) and 37 on micro-CT images (p>0.05). Further, 34 crack lines could be observed on both ES2 and micro-CT images, and the average depth presented on ES2 images was 4.56 ± 0.88 mm and 3.89 ± 1.08 mm on micro-CT images (p<0.05). More crack lines could be detected from the occlusal surface to the pulp cavity on ES2 images than on micro-CT images (22 vs 11).

Conclusion:

CBCT with NaI +DMSO as the contrast agent was equivalent to micro-CT for number of crack lines and better for depth of crack lines. NaI + DMSO could be a potential CBCT contrast agent to improve diagnostic accuracy for cracked tooth.

Keywords: Cracked tooth, Cone-beam CT, Micro-CT, Sodium iodide, Dimethyl sulfoxide

Introduction

Teeth crack is the third largest cause of tooth loss after dental caries and periodontal disease.1 There are five types of cracked teeth and cracked tooth is the third type according to the American Association of Endodontists’ classification.2 Cracked tooth refers to the incomplete fracture of a vital posterior tooth that involves the dentine and sometimes extends into the pulp.3 Early diagnosis is important, as restorative intervention can limit propagation of the crack, subsequent microleakage, and involvement of the pulpal or periodontal tissues. The signs and symptoms of cracked tooth can be quite variable and unpredictable; and the crack lines could be quite narrow(about tens of microns), this always made the diagnosis and treatment an extremely perplexing entity.4

The diagnosis of cracked tooth may be verified through a succession of in vivo procedures or tests performed by the clinician, such as visual inspection, transillumination, staining,5–7 percussion, biting, thermal pulp tests,5,8,9 CBCT,10,11 and microscopy.12 Micro-CT,13,14 ultrasound,15 optical coherence tomography16,17 and quantitative light-induced fluorescence18 are explored to detect cracks experimentally; however, none of these techniques have been used in the clinic so far. Moreover, most of these techniques are used to determine if there is a crack or not, they could not be used to determine the direction and depth of the cracked lines.

The periapical radiographs could not detect almost all the cracks due to its two-dimensional nature. Most cracks are mesiodistal while X-ray beam is faciolingual. In addition, most cracks especially initial cracks are too tiny to be detected with periapical radiographs.1,19 Cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT), which provides precise three-dimensional images with high spatial resolution (the smallest voxel size could be 75 μm11), is widely used in dental radiology in recent years. Although CBCT is widely used for diagnosis of vertical root fractures (the fifth type of cracked teeth), it still has much limitation in the diagnosis of crack lines10 and is not suggested for cracked tooth diagnosis.20 In our previous study, we found that CBCT scanning using meglumine diatrizoate (MD) as contrast agent significantly increased the detection rate of cracked tooth in vitro.21 However, attributing to the complexity of cracks and the difficulties in carrying out this technique in vivo (e.g. salivary secretion, limitation of vision), a contrast agent with better permeability and fluidity is needed.

Sodium iodide (NaI) is an inorganic compound and can be used for treatment of respiratory diseases, thyroid disease, and granulomatous lesions. Moreover, it is the first generation X-ray contrast medium.22 Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) is a very efficient solvent for water-insoluble compounds and is a hydrogen-bond disrupter. Owing to these physicochemical properties, it is widely used in the biological and medical fields. In medicine, DMSO is frequently used as a solvent in biological studies and as a vehicle for drug therapy.23 In this study, a compound contrast agent composed of NaI and DMSO was used as the CBCT contrast agent. The new contrast agent utilized the radiopacity and osmotic pressure of NaI and the permeability and hydrophilia of DMSO. The aims of this study are: (1) to evaluate the permeability and fluidity of this new contrast agent (NaI +DMSO) in artificial cracked tooth with artificial saliva pre-treated, (2) to compare the diagnostic accuracy (the number of cracks and the depth of cracks) between this new contrast-enhanced CBCT and micro-CT.

Methods and materials

Tooth collection

In this study, teeth were extracted and collected due to periodontal or orthodontic purposes. In order to exclude the possibility of an intraoperative crack of the tooth, excessive rotational forces were avoided and all teeth were immersed in saline solution (0.9% isotonic NaCl) immediately after extraction. 18 intact teeth were finally included according to the following criteria: no dental caries, root resorption, severe abrasion, wedge-shaped defects, and no visual evidence of external cracks, craze lines, or fracture lines after extraction. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of our University [2019NL-043(KS)].

Establishment of an artificial simulation cracked tooth model

The roots of the teeth from 2 mm below the enamel–dentine junction to the root apex were embedded using general purpose acrylic resin (Unifast Trad, GC Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). After the acrylic resin was completely solidified, the teeth were then soaked in liquid nitrogen (−196 ˚C) for 30 sec and quickly transferred in boiling water at 100 ˚C for 30 sec. This procedure was repeated several times until one or more crack lines were observed on the surface of crown of the teeth using transillumination. The number and position of crack lines on the buccal, palatal, mesial, and distal side of the crown were recorded.

Micro-CT scanning

The artificial cracked teeth were then scanned using micro-CT (Hiscan Information Technology Inc., China) with the following parameters: voxel size of 0.025 mm, 90 kVp, 100 μA, 0.3 mm Al filter, and acquisition time of 3 min. The images were reconstructed and analyzed with Hiscan software (Hiscan Information Technology Inc., China).

Contrast-enhanced CBCT scanning

Preparation of contrast agent

Two contrast agents were used in this study: MD and NaI + DMSO. MD was a purchased clinical used contrast agent (Xi’an Lipont Enterprise Union Management Co., Ltd., China). For NaI + DMSO, 8 g NaI (99%, Jiodine Chemical Co., Ltd., Qingdao, China) was dissolved in 10 ml purified water; this NaI aqueous solution (45 wt.%) was slowly mixed well with 15 ml DMSO (99 wt.%, Aladdin Bio-Chem Technology Co. LTD., Shanghai, China). The prepared solution is 23 wt.% NaI and 50 wt.% DMSO aqueous solution.

Pre-treatment of teeth with artificial saliva

Artificial saliva was prepared by dissolving 0.75 g of sorbic acid, 0.62 g of potassium chloride, 0.84 g of sodium chloride, 0.05 g of magnesium chloride, 0.34 g of dipotassium hydrogen phosphate, and 8 g of hypromellose in 1000 ml of 40 ˚C purified water.24 All of these chemical materials were purchased (Xilong Scientific Co., Ltd., Guangdong, China). The viscosity of the solution was 18.56 mm²/s measured with a viscosimeter (IKA Werke GmbH & CO. KG, Germany). Then, all the artificially cracked teeth were immersed in artificial saliva for 24 h.

Contrast-enhanced CBCT scanning

One routine scanning (RS) mode and two enhanced scanning (ES) modes were performed in this study. For the RS mode, the cracked teeth were scanned without a contrast agent. ES1 and ES2 modes were enhanced scanning mode using MD and NaI + DMSO, respectively, as the contrast agents. All these three modes used a NewTom VG scanner (QR SRL, Verona, Italy) according to the manufacturer’s recommended protocol with the following parameters: voxel size of 0.125 mm, 110 kV, 3.6–3.7mA, field of view of 12 × 8 cm and acquisition time of 5.4 s.

For the ES mode, the contrast agent was applied to the cracked teeth in the following steps: (i) The surface of the tooth was briefly dried with compressed air. (ii) Contrast agent was painted on the surface of all the cracks of each tooth using a disposable fiber-tip sterile applicator (TPC, Dongguan, China) twice. (iii) After painting, each tooth was left undisturbed on a small shelf for 10 min to ensure that all the cracks had been thoroughly infiltrated by the contrast agent.

Evaluation crack lines on micro-CT and CBCT images

The number and depth of crack lines were evaluated. For the number of crack lines, if a hypodense line were presented on at least two consecutive axial images, it was recorded as positive. For the depth of a crack line, the regions of interest were reconstructed along the long axis of the tooth. The number of cracks presented from the occlusal surface to the pulp cavity (Np) on CBCT ES2 and micro-CT images was evaluated. Then, the depth of a crack line presented on both micro-CT images and CBCT ES2 images were calculated. Depth equals the number of slices presented of crack lines times the thickness of axial images (DepthCBCT = Number of slices*0.125 mm, DepthMicro-CT = Number of slices*0.025 mm).

The micro-CT images were reconstructed and analyzed with Hiscan software (Hiscan Information Technology Inc., China). The CBCT images were reconstructed and analyzed with inbuilt software NNT 9.0 (QR SRL, Verona, Italy).

For number of crack lines, two observers (an oral radiologist with 5 years of working experiences (observer A) and an oral radiology postgraduate student (observer B)) independently evaluated the micro-CT, CBCT RS, ES1, and ES2 images; in case of disagreement, a senior radiologist with more than 10 years of working experience (observer C) was consulted. After 1 month, observers A and B reassessed the micro-CT, CBCT RS, ES1, and ES2 images to analyze intraexaminer agreement. For the depth of crack lines, observer A evaluated the micro-CT and CBCT ES2 images. After 1 month, observer A reassessed the micro-CT and CBCT ES2, and intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was analyzed. For the number of cracks presented from the occlusal surface to the pulp cavity (Np), observer A and B independently evaluated the micro-CT and CBCT ES2 images; in case of disagreement, observer C was consulted. After 1 month, observers A and B reassessed the micro-CT and CBCT ES2 images to analyze intraexaminer agreement.

Before evaluation, calibration, including unified training on diagnostic standards of a crack line and the calculation of depth of crack lines was performed.

Statistical analysis

Differences of number of detected crack lines between CBCT ES2 with micro-CT, CBCT RS, and CBCT ES1 were analyzed using McNemar’s test. The depth of cracks between micro-CT and CBCT ES2 was analyzed using paired t-test. κ and intraclass correlation coefficient analysis was used to assess inter- and intraexaminer agreement. Statistical analysis was conducted using the SPSS 23.0 software (IBM SPSS Statistics Base Integrated Edition 23, Armonk, NY).

Results

Crack lines observed in different groups

In all, there were 63 crack lines observed on the 18 cracked teeth using transillumination. The accuracy of detection of crack lines of micro-CT, CBCT RS, ES1, and ES2 and the differences were shown in Table 1. Significant differences were found between ES2 and RS, ES2 and ES1; however, no significant difference was found between ES2 and micro-CT.

Table 1.

Crack lines observed in different scanning modes

| RS | ES1 | ES2 | mCT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of crack lines | 4 | 4 | 45 | 37 |

| Accuracy | 6% | 6% | 71% | 59% |

| p(RS and ES2) | 0 | |||

| p(ES1 and ES2) | 0 | |||

| p (mCT and ES2) | 0.057 | |||

ES1, CBCT scanning with MD ascontrast agent; ES2, CBCT scanning with NaI+DMSO as contrast agent; RS, Routine CBCT scanning without contrast agent; mCT, Micro-CT scanning.

Depth of crack lines

There were 34 crack lines that could be both observed on CBCT ES2 and micro-CT images. The average depth presented on CBCT ES2 images and micro-CT images are shown in Table 2, significant difference was found between CBCT ES2 and micro-CT (p = 0.001). Some cracks were showed deeper on CBCT ES2 images than on micro-CT images (Figure 1). Of these 34 crack lines, there were 22 crack lines presented from the occlusal surface to the pulp cavity on CBCT ES2 images against 11 crack lines on micro-CT images (Table 2, p = 0.013). Some cracks were presented from the occlusal surface to the pulp cavity on CBCT ES2 images but not on micro-CT images (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Crack depth on CBCT ES2 and micro-CT images

| Depth | Np | |

|---|---|---|

| ES2 | 4.56 ± 0.88 mm | 22 |

| mCT | 3.89 ± 1.08 mm | 11 |

| p | 0.001 | 0.013 |

ES2, CBCT scanning with NaI+DMSO as contrast agent; Np, number of cracks detected from the occlusal surface to the pulp cavity; mCT, Micro-CT scanning.

Figure 1.

Comparison of axial images of CBCT ES2 with NaI + DMSO as contrast agents and micro-CT. A and B show the position of the axial images in the tooth (red lines); A is close to occlusal side; B is near the enamel–dentine junction; A1 and B1 were axial images scanned using micro-CT; four crack lines are seen on A1 and none of crack line is seen on B1. A2 and B2 are the axial images scanned in ES2. Four enhanced hyperdense crack lines are seen on A2 and B2. Cracks are marked as C1, C2, C3, and C4 on the images. CBCT, cone beam CT; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; NaI, sodium iodide.

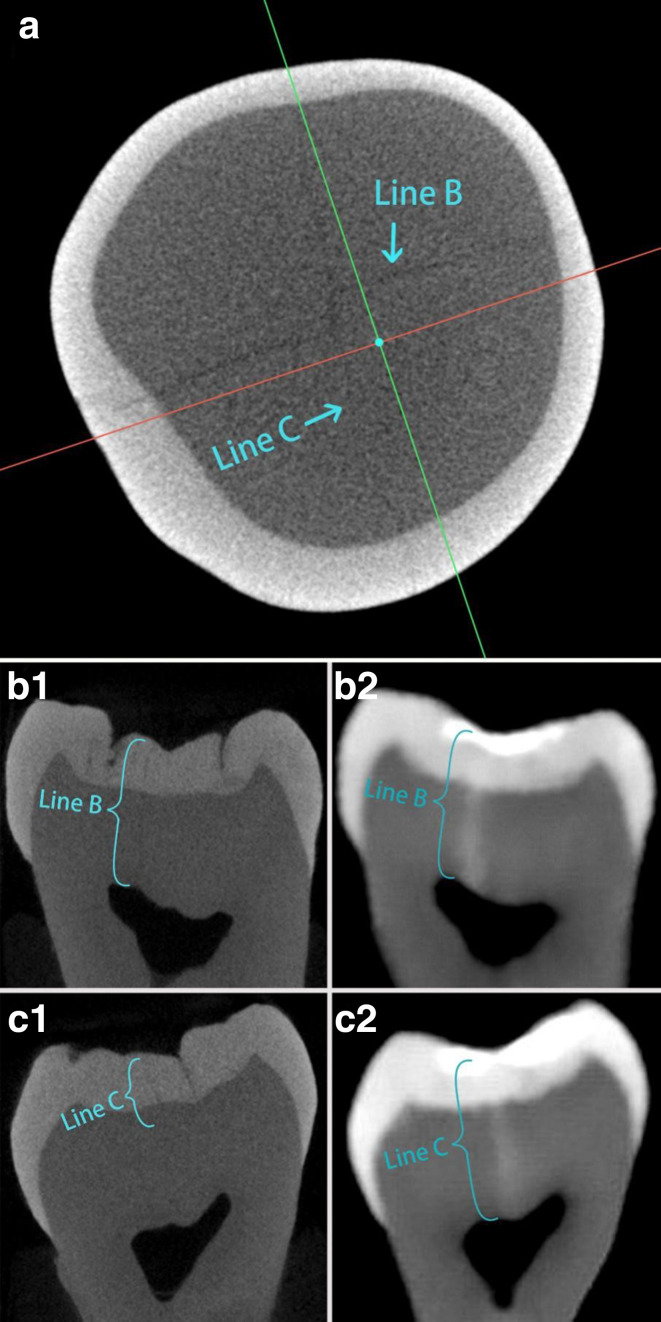

Figure 2.

Comparison of CBCT ES2 images with NaI + DMSO as contrast agents and micro-CT images for depth of cracks. a was the axial image; Crack Line B is reconstructed along the direction of the green line; Crack Line C is reconstructed along the direction of the red line. b1 is the reconstructed micro-CT image of crack Line B; b2 is the reconstructed CBCT ES2 image of crack Line B. Both of micro-CT and CBCT ES2 images presented crack Line B from the occlusal surface to the pulp cavity. c1 is the reconstructed micro-CT image of crack Line C; c2 is the reconstructed CBCT ES2 image of crack Line C. Micro-CT image presents crack Line C from the occlusal surface to the superficial layer of dentin, CBCT ES2 image presents crack Line C from the occlusal surface to the pulp cavity. CBCT, cone beam CT; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; NaI, sodium iodide.

Inter and intraexaminer agreement

Inter and intraexaminer reproducibility (κ value) in terms of the number of cracks and the number of crack lines presented from the occlusal surface to the pulp cavity was shown in Table 3. The inter- and intraexaminer agreement was almost perfect. The intraclass correlation coefficient for the depth of crack lines is also shown in Table 3, and it was excellent.

Table 3.

Repeatability analysis of number and depth of cracks in different scanning modes

| Number of cracks | Depth of cracks | Np | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RS | ES1 | ES2 | mCT | ES2 | mCT | ES2 | mCT | |

| Interexaminer agreement | 1 | 1 | 0.889 | 0.967 | 0.810 | 0.931 | ||

| Intraexaminer agreement | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.871 | 1 | ||

| Intraexaminer agreement | 0.849 | 1 | 0.963 | 0.935 | 0.875 | 0.931 | ||

| ICC | 0.891 | 0.997 | ||||||

ES1, CBCT scanning with MD ascontrast agent; ES2, CBCT scanning with NaI+DMSO as contrast agent; Np, Number of cracks detected from the occlusal surface to thepulp cavity; RS, routine CBCT scanning without contrast agent; mCT, Micro-CT scanning.

Discussion

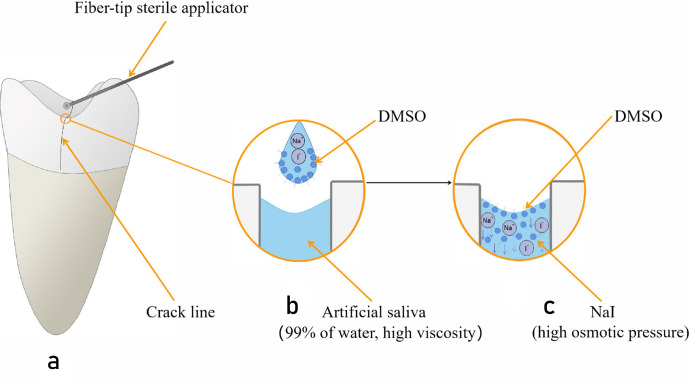

Cracked tooth always presents diagnostic challenges. Although many techniques have been studied to improve the diagnosis of cracked tooth, there has been no simple and effective technique used in the clinic so far, especially for the early cracked tooth. CBCT, which is widely used in the diagnosis of vertical root fracture, however is not widely recommended for diagnosis of cracked teeth.20 The width of early cracks is way narrower than current CBCT could identify.11 In our previous study, we found that CBCT scanning with MD as contrast agent significantly improved the detection of cracked tooth than routine scanning in vitro. However, carrying out this technique in vivo (e.g. salivary secretion, limitation of vision, early and much narrower cracks) could be much more difficult than an experimental study. A contrast agent with better permeability and fluidity is needed for further use. In this study, we developed a new contrast agent—a combination of NaI (the X-ray contrast agent) and DMSO (the solubilizer and penetrant). It’s known that NaI has much higher osmotic pressure than MD in the same concentration, and DMSO has excellent hydrophilia, therefore, much better permeability and fluidity could be expected. Different from vascular contrast agents, higher osmotic pressure is needed for better penetrating into the cracks (Figure 3). And, due to our contrast agent was only used on the surface of tooth, the increased risk of cell toxicity due to higher osmotic pressure is minimal. In this study, the CBCT scanning with this new contrast agent was compared with micro-CT regarding the detection rate and detection depth of crack lines.

Figure 3.

(a) shows how NaI + DMSO is used for diagnosis of a crack line; a disposable fiber-tip sterile applicator is used for painting the contrast agent on the surface of the crack. (b) and (c) show how NaI +DMSO infiltrated into the crack. The crack is filled with artificial saliva, which mainly consists of water and has high viscosity. For the contrast agent NaI + DMSO, DMSO is at the surface of liquid drop; DMSO increases hydrophilia of the contrast agent and helps the contrast agent dissolve into the artificial saliva; and the high osmotic pressure of NaI makes the contrast agent reaches deeply. CBCT, cone beam CT; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; NaI, sodium iodide.

One important factor that influenced the contrast agent infiltrating into the cracks is the saliva. According to relevant research, the viscosity of saliva is 23 mm²/s to 0.2 mm²/s (11.3 to 450 s−1 of shear rate, 37 ˚C),25 which is inversely proportional to velocity of flow. Because saliva is almost static in cracks, the viscosity of saliva in crack lines is significantly higher than that of water (0.7 mm²/s, 37 ˚C).26 In this study, artificial saliva pre-treatment was used before scanning to stimulate the interference of saliva in clinic practice. The detection rate of crack lines was significantly reduced with artificial saliva pre-treatment than our previous study which used MD as contrast agent. The detection rate was only 6% on both RS mode and CBCT ES1 mode (MD as contrast agent). Although the surface of interest was briefly air blown with compressed air before contrast agent was smeared on the crack lines, the inner saliva in the crack lines could hardly be removed in clinical practice. We speculate that viscous saliva obstructs the pathway when contrast agent is infiltrating to the crack lines. Thus, a contrast agent with better permeability and fluidity in saliva is needed.

It is known that the voxel size is an important factor of cracks diagnosis. Theoretically, the smaller the voxel size is, the higher the detection rate is. In this study, the voxel size was 0.125 mm for CBCT and 0.025 mm for micro-CT. Without the contrast agent, there were only four crack lines presented on CBCT images. In this study, we modified the method of establishing artificial cracked tooth models, and the much narrower crack lines were obtained than our previous study (6% observable in RS as compared to 32% observable in our pervious study) by decreasing time of soaking them cyclically in liquid nitrogen and hot water. However, with NaI + DMSO as the contrast agent in this study, crack lines detected on CBCT images increased to 45, which was higher than on the micro-CT images. Moreover, for the depth of crack lines, the CBCT ES2 has a higher diagnostic efficiency. The crack lines detected on CBCT ES2 images was deeper than on micro-CT images (p = 0.001). More cracks reaching into the pulp cavity were observed on CBCT ES2 images than on micro-CT images (p = 0.013). It is known that accurate evaluation of depth of crack lines is quite important in treatment planning, especially whether the cracks have reached into the pulp cavity. When the crack extends into or is in close proximity to the pulp, ingress of bacteria and their by-products may cause pulpitis, pulp necrosis and subsequent apical periodontitis, and a root canal treatment is needed in these situations.27

Moreover, according to research about the microcracking process of human detin, dentinal tubules were the nucleation sites for microcracks. Furthermore, propagation of microcracks follows the general direction of the tubules, parallel to the main fracture and frequently deflected to adjacent tubules.28 The tubules are a few microns in diameter and occupy about 10% or less by volume of the bulk dentin.29 Therefore, we speculated that the early cracks could be about tens of microns. A research about vertical root fracture also showed that the narrowest crack lines recorded in that study in vivo was 10 μm.30 The voxel size of the micro-CT in this study is 25 μm. So only some cracks were observable on micro-CT images. A deeper depth demonstrated than micro-CT means CBCT ES2 could detect early cracks narrower than 25 μm and the contrast agent is able to reach the front of the microcrack. Moreover, we also observed an interesting phenomenon, wherein the images of cracks with the contrast agent were more diffuse and unclear in the deeper cracks than in the superficial cracks (Figure 1). It matches the propagation mode of cracks (following the direction of major crack in a spreading way).28 We also considered that deep cracks are narrower and the contrast agent in them is relatively lower than in superficial cracks.

Regarding these two materials, DMSO is generally safe when using in small dose.,31 and NaI also has no adverse reactions reported when used in small doses.22,32 Considering the quite low dose used and it was painted on the surface of teeth, there should be no obvious toxicity for this contrast agent. However, systemic animal studies such as acute toxicity of the contrast agent to the mucosa, the allergic reactions in accidental contact with the skin and gastrointestinal effects in an accidental ingestion should be designed and performed in future for further in vivo usage.

When CBCT is used in vivo, the movement of muscles and the limitation of vision will increase the difficulties of carrying out this technique, and hence the infiltrated contrast medium in crack lines may be lower than in vitro. At the same time, some cracks are located under the caries or filling materials in vivo. The substances in the caries holes such as food debris and corroded dental tissue may affect the penetration effect of the contrast agent. Therefore, this contrast agent needs to be further improved for future clinical application.

Conclusion

CBCT with NaI + DMSO as the contrast agent significantly improved the detection of cracked tooth: equivalent to micro-CT for number of crack lines and better than micro-CT for depth of crack lines. NaI + DMSO could be a potential CBCT contrast agent for more accurate diagnosis of cracked tooth.

Footnotes

Acknowledgments: This work was supported by the Second Level Fund for the Young Talents in the Health Field of Nanjing City (QRX17079), the Medical Science and Technology Development Foundation (YKK19090), the Jiangsu Province Medical Association Roentgen Imaging Research Funds (SYH-3201150-0007(2021002)). The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article. All experimental protocols were approved by the guidelines in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH publication No. 85-23, revised 1985) and was approved by the Ethics Review Board for Animal Studies of Nanjing Stomatological Hospital, Medical School of Nanjing University.

The authors LeiYing Miao and ZiTong Lin contributed equally to the work.

Contributors: ZiYang Hu contributed to writing of this manuscript and data analysis. TieMei Wang contributed to data curation, interpretation of the results. Xiao Pan and JiaHao Liang contributed to CBCT and micro-CT image evaluation. DanTong Cao contributed to establishment of cracked tooth models. AnTian Gao contributed to animal study. Xie Xin and Shi Xu contributed to study design. LeiYing Miao contributed to collection of materials and study design. ZiTong Lin contributed to Conceptualization, CBCT and micro-CT image consultation, review & editing of this manuscript, and funding acquisition. All authors gave final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

ZiYang Hu and TieMei Wang have contributed equally to this study and should be considered as co-first authors.

Contributor Information

ZiYang Hu, Email: pyx112233@163.com.

TieMei Wang, Email: tiemie106@263.net.

Xiao Pan, Email: duierjiabenpx@163.com.

DanTong Cao, Email: 896999194@qq.com.

JiaHao Liang, Email: 948977297@qq.com.

AnTian Gao, Email: gaoantian_1995@163.com.

Xin Xie, Email: 526784748@qq.com.

Shi Xu, Email: 842650592@qq.com.

LeiYing Miao, Email: miaoleiying80@163.com.

ZiTong Lin, Email: linzitong_710@163.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Geurtsen W, Schwarze T, Günay H, Diagnosis GH. Diagnosis, therapy, and prevention of the cracked tooth syndrome. Quintessence Int 2003; 34: 409–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim J-M, Kang S-R, Yi W-J. Automatic detection of tooth cracks in optical coherence tomography images. J Periodontal Implant Sci 2017; 47: 41–50. doi: 10.5051/jpis.2017.47.1.41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen M, Fu K, Qiao F, Zhang X, Fan Y, Wang L, et al. Predicting extension of cracks to the root from the dimensions in the crown: A preliminary in vitro study. J Am Dent Assoc 2017; 148: 737–42. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2017.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berman LH, Kuttler S. Fracture necrosis: diagnosis, prognosis assessment, and treatment recommendations. J Endod 2010; 36: 442–6. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis R, Overton JD. Efficacy of bonded and nonbonded Amalgam in the treatment of teeth with incomplete fractures. J Am Dent Assoc 2000; 131: 469–78. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2000.0203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ailor JE. Managing incomplete tooth fractures. J Am Dent Assoc 2000; 131: 1168–74. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2000.0351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wright HM, Loushine RJ, Weller RN, Kimbrough WF, Waller J, Pashley DH. Identification of resected root-end dentinal cracks: a comparative study of transillumination and dyes. J Endod 2004; 30: 712–5. doi: 10.1097/01.DON.0000125876.26495.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Türp JC, Gobetti JP. The cracked tooth syndrome: an elusive diagnosis. J Am Dent Assoc 1996; 127: 1502–7. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1996.0060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lynch CD, McConnell RJ. The cracked tooth syndrome. J Can Dent Assoc 2002; 68: 470–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chavda R, Mannocci F, Andiappan M, Patel S. Comparing the in vivo diagnostic accuracy of digital periapical radiography with cone-beam computed tomography for the detection of vertical root fracture. J Endod 2014; 40: 1524–9. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2014.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brady E, Mannocci F, Brown J, Wilson R, Patel S. A comparison of cone beam computed tomography and periapical radiography for the detection of vertical root fractures in nonendodontically treated teeth. Int Endod J 2014; 47: 735–46. doi: 10.1111/iej.12209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clark DJ, Sheets CG, Paquette JM. Definitive diagnosis of early enamel and dentin cracks based on microscopic evaluation. J Esthet Restor Dent 2003; 15: 391–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8240.2003.tb00963.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aboud LRdeL, Santos BCD, Lopes RT, Viana LAC, Scelza MFZ. Effect of aging on dentinal crack formation after treatment and retreatment procedures: a micro-CT study. Braz Dent J 2018; 29: 530–5. doi: 10.1590/0103-6440201802134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim M-J, Jang H-S, Kim D-K, Kim B-O. Analysis of vertical root fracture in endodontically versus nonendodontically treated teeth on patients with periodontitis. J Korean Acad Periodontol 2005; 35: 413–25. doi: 10.5051/jkape.2005.35.2.413 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Culjat MO, Singh RS, Brown ER, Neurgaonkar RR, Yoon DC, White SN. Ultrasound crack detection in a simulated human tooth. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2005; 34: 80–5. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/12901010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Imai K, Shimada Y, Sadr A, Sumi Y, Tagami J. Noninvasive cross-sectional visualization of enamel cracks by optical coherence tomography in vitro. J Endod 2012; 38: 1269–74. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2012.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee S-H, Lee J-J, Chung H-J, Park J-T, Kim H-J. Dental optical coherence tomography: new potential diagnostic system for cracked-tooth syndrome. Surg Radiol Anat 2016; 38: 49–54. doi: 10.1007/s00276-015-1514-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jun M-K, Ku H-M, Kim E, Kim H-E, Kwon H-K, Kim B-I. Detection and analysis of enamel cracks by quantitative light-induced fluorescence technology. J Endod 2016; 42: 500–4. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2015.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Talwar S, Utneja S, Nawal RR, Kaushik A, Srivastava D, Oberoy SS. Role of cone-beam computed tomography in diagnosis of vertical root fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Endod 2016; 42: 12–24. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2015.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patel S, Brown J, Semper M, Abella F, Mannocci F. European Society of Endodontology position statement: use of cone beam computed tomography in Endodontics: European Society of Endodontology (ESE) developed by. Int Endod J 2019; 52: 1675–8. doi: 10.1111/iej.13187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yuan M, Gao AT, Wang TM, Liang JH, Aihemati GB, Cao Y, et al. Using meglumine diatrizoate to improve the accuracy of diagnosis of cracked teeth on cone-beam CT images. Int Endod J 2020; 53: 709–14. doi: 10.1111/iej.13270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brunton LL, Lazo JS, Parker KL. Goodman and Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. The 11th edition. United States: The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2006. . 1531–5. doi: 10.1036/0071422803 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiong X, Luo S, Wu B, Wang J. Comparative developmental toxicity and stress protein responses of dimethyl sulfoxide to rare minnow and zebrafish embryos/larvae. Zebrafish 2017; 14: 60–8. doi: 10.1089/zeb.2016.1287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amal ASS, Hussain S, Jalaluddin MA. Preparation of artificial saliva formulation. Int Conf ICB Pharma II 2015; A002: 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rantonen PJ, Meurman JH. Viscosity of whole saliva. Acta Odontol Scand 1998; 56: 210–4. doi: 10.1080/00016359850142817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Korson L, Drost-Hansen W, Millero FJ. Viscosity of water at various temperatures. J Phys Chem 1969; 73: 34–9. doi: 10.1021/j100721a006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu S, Lew HP, Chen NN. Incidence of pulpal complications after diagnosis of vital cracked teeth. J Endod 2019; 45: 521–5. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2019.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eltit F, Ebacher V, Wang R. Inelastic deformation and microcracking process in human dentin. J Struct Biol 2013; 183: 141–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2013.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nanci A. Ten Cate’s oral histology: development, structure, and function. New York: Mosby; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang C-C, Chang Y-C, Chuang M-C, Lin H-J, Tsai Y-L, Chang S-H, et al. Analysis of the width of vertical root fracture in endodontically treated teeth by 2 micro-computed tomography systems. J Endod 2014; 40: 698–702. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2013.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kollerup Madsen B, Hilscher M, Zetner D, Rosenberg J. Adverse reactions of dimethyl sulfoxide in humans: a systematic review. F1000Res 2018; 7: 7. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.16642.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wright WW. Remington’s Pharmaceutical Sciences (Fourteenth Edition. J AOAC Int 1971; 54: 747–8. doi: 10.1093/jaoac/54.3.747 [DOI] [Google Scholar]