Abstract

Background

Decades of effectiveness research has established the benefits of using patient decision aids (PtDAs), yet broad clinical implementation has not yet occurred. Evidence to date is mainly derived from highly controlled settings; if clinicians and health care organizations are expected to embed PtDAs as a means to support person-centered care, we need to better understand what this might look like outside of a research setting.

Aim

This review was conducted in response to the IPDAS Collaboration’s evidence update process, which informs their published standards for PtDA quality and effectiveness. The aim was to develop context-specific program theories that explain why and how PtDAs are successfully implemented in routine healthcare settings.

Methods

Rapid realist review methodology was used to identify articles that could contribute to theory development. We engaged key experts and stakeholders to identify key sources; this was supplemented by electronic database (Medline and CINAHL), gray literature, and forward/backward search strategies. Initial theories were refined to develop realist context-mechanism-outcome configurations, and these were mapped to the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research.

Results

We developed 8 refined theories, using data from 23 implementation studies (29 articles), to describe the mechanisms by which PtDAs become successfully implemented into routine clinical settings. Recommended implementation strategies derived from the program theory include 1) co-production of PtDA content and processes (or local adaptation), 2) training the entire team, 3) preparing and prompting patients to engage, 4) senior-level buy-in, and 5) measuring to improve.

Conclusions

We recommend key strategies that organizations and individuals intending to embed PtDAs routinely can use as a practical guide. Further work is needed to understand the importance of context in the success of different implementation studies.

Keywords: implementation, patient decision aids, rapid realist review, realist methods, shared decision making

Decades of effectiveness research has firmly established the patient-level benefits of using patient decision aids (PtDAs).1,2 More work is needed to assess the true impact of routine PtDA implementation on health care users and providers, but the promising benefits and lack of harms identified by controlled studies has led to strong international policy support for more person-centered health care systems underpinned, in part, by increasing implementation of PtDAs.3–9 However, broad clinical implementation has not yet occurred, and there is a notable intention-behavior gap when PtDAs are used outside experimental studies in routine clinical settings.10

PtDAs support patients’ participation in shared decision making (SDM) with health care professionals by making options explicit, providing evidence-based information about the associated benefits/harms, and helping patients to consider what matters most to them in relation to the possible outcomes.1 Formats vary (e.g., paper based, DVD, website), and distribution methods can be tailored to the condition and setting, with PtDAs being delivered either as part of the clinical pathway (e.g., made available to patients before or during consultation) or via direct-to-consumer approaches (e.g., for population-level cancer screening programs, access provided via screening invitations). Various studies have examined and described key factors that influence successful implementation of SDM more broadly.11–15 Interventions studied include PtDAs and other approaches that encourage SDM behaviors, including patient activation materials and clinician SDM skills training.

The International Patient Decision Aid Standards (IPDAS) Collaboration review published in 201316 explored the success levels of different implementation strategies and included findings from controlled trial settings. Key barriers identified in the 2013 review included health care professionals’ (HCPs) attitudes toward SDM, lack of understanding in how to use PtDAs and undertake SDM, HCPs’ lack of trust in PtDA content, lack of clarity among HCPs regarding the purpose of PtDAs in relation to other information available for patients, HCPs believing that patients do not want decisional responsibility, competing clinical demands, and the time it would take to distribute and use the PtDA. Key facilitators included system-level approaches (e.g., systematic identification of patients ahead of appointments via electronic health records and distribution methods that did not rely on HCPs to initiate access), SDM and/or PtDA training and skills development, and dedicated clinical leadership (e.g., clinical champion).

Despite their benefits and various policies mandating their dissemination and use,3–9 widespread adoption of PtDAs has not occurred, and significant gaps exist in understanding factors contributing to adoption, implementation, and sustainability of these interventions in routine clinical settings. Strong foundational research has examined the implementation of SDM in health care, typically through large-scale demonstration projects (e.g., Informed Medical Decisions Foundation/Healthwise),17,18 and excellent examples of local adoption also exist (e.g., Dartmouth Hitchcok Medical Center, Lebanon, NH, USA).19 The literature listing barriers and facilitators of PtDA dissemination and implementation, as perceived by HCPs and patients, is also well established.16 However, despite the valuable learning, much of it is derived from highly controlled settings, which might not be representative of day-to-day processes and resources (human or financial) in routine clinical settings. Further, although lists of barriers and facilitators are useful markers to guide efforts to embed PtDAs, they provide less insight into why and how these factors influence implementation and can overlook the relations between different factors.20 PtDAs are not “magic bullets” that will always deliver the intended benefits to patients; their usefulness will ultimately depend on context and implementation.21 If clinical teams and organizations are being encouraged or mandated (e.g., clinical guidelines) by national health agencies to embed PtDA as a means to support person-centered care, we need to better understand what this might look like outside of a research setting, which contexts are likely to be more successful, and which might face additional challenges.

This current review was conducted in response to the IPDAS Collaboration’s evidence update process, which informs their published standards for PtDA quality and effectiveness.22–24 It updates the theory and evidence provided in the 2013 review16,25 through the sole inclusion of real-world data, exclusion of data from highly controlled settings, an understanding of the contexts that enable or hinder implementation, and the mechanisms (i.e., changes in people’s reasonings and actions) through which implementation is achieved. The main aim of this current review is to develop context-specific program theories that explain why and how PtDAs are successfully implemented in routine health care settings, providing a framework that will be useful to various stakeholders committed to embedding these tools routinely.

Method

We used rapid realist review (RRR) methodology26 and the RAMESES publication standards for realist reviews.27 RRR methodology moves beyond traditional reviews by allowing researchers to answer questions about why interventions in complex social contexts, such as routine health care, work or do not work.28 We chose this method as it allowed us to look beyond the overall success of a PtDA intervention to generate explanations about what works for whom, in what contexts, to what extent, and, most importantly, how and why?28

The resulting knowledge synthesis highlighted possible interventions (I) that could be implemented in a specific context (C) that in turn interact with various mechanisms (M) and produce outcomes (O) of interest,28 in this case, implementation of PtDAs in routine health care settings (see Box 1 for definitions of specific terminology). Two reviewers (N.J.-W. and T.v.d.W.) conducted a scoping exercise of existing literature examining barriers and facilitators to implementing PtDAs and SDM9,11–13,16,25,29,30 to agree on the review questions and scope and to generate initial theories. The a priori proposal was reviewed and approved by the IPDAS Steering Committee and registered with PROSPERO (CRD42019153334).

Box 1.

Glossary of Key Terms and Abbreviations

| Context (C) | Preexisting conditions outside the control of the intervention developers which influence the success or failure of the intervention (ref Pawson and Tiley 200831) |

| Mechanism (M) | Peoples’ reaction(s) to the implementation of the intervention; how does it change their reasoning and actions? (ref Pawson and Tiley 200831) |

| Outcome (O) | Intended and unintended consequences of the intervention as a result of a mechanism operating within a context (ref Pawson and Tiley 200831) |

| Intervention (I) | Features of the intervention resource (ref Pawson and Tiley 200831) |

| Implementation | The constellation of processes intended to get an intervention into use within an organization |

| Patient decision aid (PtDA) | Interventions that support patients to make decisions, by making decisions explicit, providing information about options and associated benefits/harms, and helping clarify congruence between decisions and personal values (ref Stacey 20171) |

We followed the key stages of an RRR: identifying scope/research questions, identifying literature for inclusion, quality appraisal, data extraction, and data synthesis.26 Our specific foci were to engage key experts and stakeholders to streamline the review process, produce useful results for those planning to implement PtDAs, and to create a set of recommendations for the IPDAS Collaboration’s updated evidence document for PtDA implementation. We convened a review team (named co-authors, led by N.J.-W. and T.v.d.W.) identified via the IPDAS Collaboration’s call for evidence update chapter authors to support the review process in the areas of literature identification, data extraction, and theory development. Typically, RRRs involve consultation with a broader expert panel to identify literature and corroborate theory development; however, as the review team consisted of a number of key international experts in the field of PtDA development, evaluation, and implementation, representing a range of disciplines and backgrounds, the review team also fulfilled this role.

Identifying and Selecting Literature for Inclusion

The review team identified an initial list of potential articles that could contribute to theory development and a list of known organizations and individuals involved in the implementation of PtDAs. The lead authors (N.J.-W./T.v.d.W.) screened articles to determine if they could likely contribute to understanding what facilitates and/or hinders PtDA implementation in routine clinical settings. Articles were included if the study reported implementation of a PtDA (as defined by the IPDAS Collaboration)1 in a routine health care setting (defined as daily situations without significant additional resources, in which clinicians and/or providers had been encouraged to integrate the PtDA into usual care routines) and if PtDA and dissemination/implementation strategies were described. Articles were excluded if the study used an intervention not classified as a PtDA1 (e.g., education resource, information leaflet), if the PtDA supported decisions about health insurance/provider options, or if the PtDA was implemented in highly controlled settings, such as randomized controlled trials or process evaluations conducted as a sibling study assessing implementation in a controlled research setting. Although secondary analysis of experimental studies has its relevance, we chose to exclude sibling studies associated with experimental studies that focus on measuring the efficacy or effectiveness of PtDAs. These studies likely bypassed routine clinical procedures to enlarge the effect of the PtDA, thus being less representative of everyday clinical settings, and would have limited bearing on our program theory. Studies exploring routine implementation of SDM outside controlled settings are relatively new, and our aim was to build on the 2013 review; thus, articles were restricted to a 10-y period (2009–2019). There were no restrictions regarding PtDA format (e.g., web based, paper based), type of decision, healthcare settings, or population/participants.

Using the initial set of articles, a combination of free-text and MeSH headings related to “decision aids,”“shared decision making,” and “implementation” were used to develop a Medline search strategy, which was adapted for use in CINAHL (see Supplementary File 1 for the Medline search strategy). Relevant websites (e.g., databases of funders who support PtDA implementation programs), policy documents, and known individuals and organizations were consulted to determine whether any unpublished works relating to the review questions were available. Citations were exported to EndNote; titles and abstracts of all papers identified via electronic searches were screened (by T.v.d.W.) to determine if they could answer the review question. Potentially relevant articles were obtained, and full texts were screened (N.J.-W. and T.v.d.W.) against our inclusion/exclusion criteria (noted above). Reference lists of included studies were consulted for forward and backward searching, and a clear audit trail of all data sources was maintained.

Data Extraction

A data extraction team was convened from members of the broader review team, and a data extraction template was developed, piloted, and streamlined to increase emphasis on context-mechanism-outcome (CMO) configurations. In the final version, qualitative, quantitative, and contextual data that could answer our review questions were extracted under the following broad categories: study/participant characteristics, PtDA characteristics, dissemination and implementation, implementation evaluation data (e.g., reach, dose, feasibility), and data supporting emerging theories about what works, how, and in what circumstances, for implementation of PtDAs (if-then statements). N.J.-W. coordinated extractions completed by the data extraction team members, checked the accuracy and consistency of data extracted, and consulted with individuals when necessary to clarify information or resolve discrepancies.

Data Synthesis

Explanatory data in the results sections of included studies relating to “what works in implementing PtDAs?” were initially extracted as “if-then” statements that described links between elements of contexts, mechanisms, and outcomes. As the synthesis progressed, comparable if-then statements were grouped by N.J.-W., while ensuring linkage to the original data and source of the individual if-then statements. We applied Pawson’s reasoning processes31 to generate refined CMO configurations based on the grouped if-then statements (see Supplementary File 2 for example process of theory development). Realist reviewers typically make use of existing theories to make sense of the evidence generated during their review. We chose the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR)32 to help us interpret the findings emerging from the data, as it is designed to guide systematic assessment of multilevel implementation contexts to identify factors that might influence intervention implementation and effectiveness. It is composed of 5 major domains, each made up of several constructs (see Box 2 for domain descriptions). The initial draft of CMOs was presented back to the review team, who were asked to assess validity, relevance to the research questions, and importance of the inferences made. Feedback from the review team was used to refine the program theory (3 iterations), exclude theories viewed as less important and relevant, and inform further data searches for elements that were perceived as missing, based on prior knowledge and experience.

Results

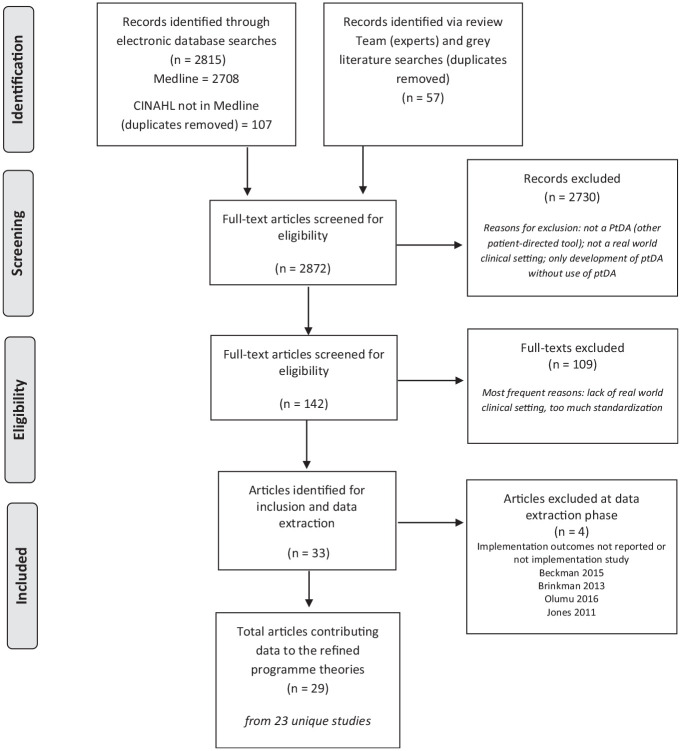

A total of 29 articles from 23 distinct studies contributed data to the developing theories. Figure 1 outlines the review process, including data sources and exclusions, and Table 1 presents the key characteristics of included studies. Most studies were from the United States (n = 14/23) and used a mixed-methods approach (n = 19/23). Seven studies specifically stated that they were underpinned by quality improvement methodology. PtDA delivery varied between the studies, including distribution to patients before the decision-making consultation (n = 11), use during the decision-making consultation (n = 6), or distribution to providers (n = 6). A variety of PtDA formats was used (e.g., video, web based, paper based) across a range of health and behavioral contexts (e.g., cancer, mental health, maternity, family planning, orthopedics) for a range of treatment or management decisions (see Supplementary File 3 for details) in various different settings (e.g., community based, primary care, secondary/specialist care). Implementation strategies differed across the studies, ranging from motivated clinicians embedding PtDAs into their clinics with limited additional support and resources to structured implementation programs using quality improvement methodology with direct and continuous support from implementation teams with expertise in these methods. Full details of study type, setting, PtDA characteristics, and implementation strategy can be found in Table 1. The review team consisted of 18 international SDM experts representing 9 countries: United States (n = 5), Canada (n = 4), United Kingdom (n = 3), Australia (n = 1), Chile (n = 1), Denmark (n = 1), France (n = 1), Germany (n = 1), The Netherlands (n = 1). The team represents a range of professional backgrounds: health services research (n = 7), medical (n = 4), psychology (n = 2), nursing (n = 2), epidemiology (n = 1), public health (n = 1), allied health professions (n = 1). Data extraction was conducted by 15 members of the review team and 2 additional researchers linked with review team members. All members contributed to theory development and refinement.

Figure 1.

Data searches and sources of included articles.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Included Studies (n = 23 from 29 Articles), Grouped according to the Method of PtDA Distribution

| Author, Year, Country, Linked Studies | Study Aim(s), Study Type, Setting | PtDA Characteristics, Intended Distribution and Use | Implementation Strategy and Duration | Process Outcome Data | Supports Theory Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PtDAs First Distributed to Patients before Decision-Making Consultation | |||||

| Belkora et al., 2012, United States33 | To examine the reach and impact of 5 PtDAs routinely distributed

to breast cancer patients as part of a SDM demonstration

project. Case series (quantitative). Large multidisciplinary breast cancer center. |

Five video-based breast cancer PtDAs covering different decision points (ductal carcinoma in situ; early-stage surgery; breast reconstruction; adjuvant therapy; metastatic cancer). Decision Services personnel calls patient prior to appointment offering decision support materials/services, including appropriate PtDA. If required, PtDA mailed to patient within 24 h. Accompanied by before-and-after knowledge survey. | Decision Services already integrated into the Breast Cancer

Centre and oversaw routine distribution of the suite of PtDAs as

part of routine care, while measuring process and outcome

data. Thirty-six month implementation phase. |

A total of 61% (1098/1800) of new breast cancer patients received PtDA at home address, after call for consent. Reach attained 70% in the final year of implementation. | 7 |

| Berry et al., 2019, United States34 | To assess various implementation strategies for the Personal

Patient Profile–Prostate decision aid (P3P), by measuring

referral and access rates to P3P and analyzing feedback from

clinical staff and providers. Hybrid type 1 effectiveness-implementation trial (mixed methods). Secondary care (urology and multidisciplinary clinics in large hospitals). |

Personalized web-based PtDA for localized prostate cancer. Distribution methods varied depending on clinic (e.g., independent tool or integrated into existing educational resources), but all involved distributing link to the PtDA after disclosure of positive biopsy but before full options review visit. Patient has option to print and take PtDA report to decision-making consultation or email to clinic to be used during the consultation. iPads provided at each site before consultation for those men without internet access. | Conducted as part of hybrid type 1 effectiveness-implementation

trial. Six largest-volume urology and multidisciplinary clinics

participated in prior randomized effectiveness study selected.

Planning session convened at each site to develop workflow for

implementation. Physician staff received presentation about

study aims/publications; face-to-face nurse/staff meetings

reflected on current practice, considered various approaches

that would fit best; web trainings conducted with clinic staff

(including coordinators and nurses); staff provided with

instruction sheets and flyers for PtDA

referrals. Approximately 6-mo implementation phase. |

A total of 51% (252/495) of patients were informed about PtDA;

43% (107/252) accessed the PtDA. Invitation via personal e-mail/telephone contact resulted in 82%–87% PtDA access rates. Written invitations resulted in only 0% to 14% access rates. |

3a, 3b, 3c, 4a, 5a, 7 |

| Brackett and Kearing, 2015, United States35 | To facilitate SDM during preventative visits by using a

web-based survey system to offer colorectal cancer and prostate

cancer screening decision aids to appropriately identified

patients prior to the visit. Observational (quantitative). Academic general medical practice. |

PtDA (content not the same, different developers). Eligibility to receive PtDA determined prior to appointment. Patients offered choice of video or print version. If accepted, mailed to patient before appointment. Also completed knowledge and personal value questions. Knowledge provided in written report for patient; this report and a preference report fed forward to clinician available at decision-making consultation. | One academic general medical practice. Limited information

provided about implementation strategy. Thirty-eight month implementation phase (January 2008–March 2011). |

A total of 15% (552/3587) of patients that had not previously received a PtDA requested the PtDA after digital invitation. Patients could choose between video or written PtDA; 74% choose the written format. The most common reason to decline PtDA was the patient’s belief that they already knew enough to make the decision. | 1, 7 |

| Dharod et al., 2019, United States36 | Determine the feasibility of a digital health strategy for lung

cancer screening delivered via a patient

portal. Single-arm pragmatic trial. Large academic health care system (4 hospitals and 70+ community-based clinics). |

Interactive website with personalized risk-benefit information (mPATH-Lung). Electronic health record algorithm developed to identify eligible patients. Invitation to view PtDA sent via patient portal. After viewing PtDA, patients who note “yes” or “maybe” to the question “would you like to receive screening?” scheduled follow-up in-person SDM visit with nurse practitioner. | Conducted as part of a single-arm pragmatic trial in large

academic health system, including 4 hospitals and 70

community-based clinics. Informed consent waived by review board

as embedded as part of routine care. Limited information about

implementation strategy. Four-month implementation phase (November 2016–February 2017). |

A total of 40% (400/1000) of current or former smokers visited the web-based PtDA after digital message sent via patient portal. Median number of days between reading the message and PtDA = 0.4 (range 0–75). | 5a, 7 |

| Dontje et al., 2013, United States37 Holmes-Rovner et al., 201138 |

To develop and evaluate the feasibility of multifaceted SDM

interventions to prompt SDM in primary care about angiography in

stable coronary artery disease. Pilot cohort study (quantitative and qualitative). Academic clinics (family and internal medicine). |

Paper-based and DVD PtDA (“Treatment Choices for Coronary Artery Disease”). Eligible patients mailed PtDA and asked to review before they attended a 90-min group educational visit (where they then completed a 1-page treatment encounter planning guide). Patient instructed to take the PtDA and completed treatment encounter planning guide to their appointment (SDM discussion). | Two academic clinics. Unclear why clinics were selected.

Provider training included 1) clinical content in grand rounds,

2) provider training in communication skills and clinical

evidence review in the form of a 90-min workshop that could be

delivered as continuing medical or nursing education or as a

noon-time conference. Recruitment 3 mo. Implementation phase not reported. |

A total of 17% (43/247) patients were invited to review a PtDA. PtDA sent following signed consent. Actual use of the PtDA was not reported. Self-selection of participants, who were the more engaged and motivated in their care, seems to have occurred. | 1 |

| Krist et al., 2017, United States39 | To examine whether patients and clinicians will use a novel

health information technology (decision module) and its impact

on care across 3 cancer screening

decisions. Observational cohort study (quantitative). Twelve primary care practices (breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer). |

Three online PtDAs, informed decision-making modules for the following decisions: when to start breast cancer screening, how to be screened for colorectal cancer, and not being screened for prostate cancer. Guides patients through 7 steps 1) sent to patient via patient portal prior to consultation; 2) assesses personal preferences, knowledge, and needs and patients’ readiness to make a decision; 3) provides personalized education material tailored to preferences and decision stage; 4) allows patients to share their preferences and decision needs with their clinician; 5) provides prompt to patient and HCP to use the information to make a decision; 6) guides patients to make a choice, which can include deferring the decision; and 7) invites patients and clinicians to provide input after the encounter. | Twelve primary care practices that used electronic health

records. PtDA delivery integrated into central patient portal

(MyPreventiveCare). No further information provided regarding

selection of primary care practices. Eight-month implementation phase (January–August 2015). |

At the time of the study, 55,453 patients (34.5% of practice population) had a portal account; 23,546 used the portal during the study period (some evidence that users were more likely to be older or have comorbidities and were less likely to be Hispanic or African American). | 5a, 7 |

| Lin et al., 2013, United States40 | To explore processes for distributing PtDAs to patients in

clinical settings and to identify barriers and facilitators to

implementation. Qualitative and quantitative data sources (collected as part of a prior implementation project). Primary care practices. |

Clinics could choose from choice of 16 PtDAs (could choose multiple topics). Fourteen of 16 were booklet and DVD; 2 of 16 were booklet only. PtDA delivery was adapted by each clinic depending on needs/clinic workflow (i.e., distributed by physician/medical assistants in person, solicitation of patient interest at point of care, direct mailing). Designed for use inside and outside the consultation. | Physician and staff champion established in 5 primary care

clinics. Physician champion provided information about project

to each clinic’s leadership team. Both champions responsible for

promoting the program. Project team members who collaborated

with clinics to agree on PtDA topics tailor decision aid

distribution methods to clinic workflow. Project team attended

bimonthly meetings with project team and engaged in social

marketing efforts. January 2010 to June 2012 (29-month implementation phase) |

Overall rate of distribution of PtDA was 10%. The longitudinal data show a decrease in distribution of PtDA instead of a sustainable increase. | 3a, 3b, 3c, 4a, 4b, 6, 7 |

| Savelberg et al., 2019a, The Netherlands41 Savelberg-Pasmans, 2019b42 |

To explore experiences (including perceived barriers and

facilitators), issues, and concerns of early-adopter

professionals with regard to SDM, and the specific lessons on

implementation of a breast cancer PtDA within an oncological

clinical pathway. Observational prospective process evaluation (mixed-methods). Secondary care (hospital setting). |

Personalized web-based PtDA for early-stage breast cancer decisions (curative surgery, chemotherapy, reconstructive surgery). Patient receives personalized written prescription from clinician during diagnostic consultation (with relevant decision points and log-in code); patient views PtDA at home before decision-making consultation. | Seven breast cancer teams (consisting of at least 1 surgeon and

1 nurse) with positive attitudes toward SDM and willingness to

improve SDM process were recruited. Meeting arranged with each

team (all team members) prior to implementation with focus on

tailoring implementation, covering 1) recommendations on how to

present PtDA to patient, 2) minor adjustments to pathway, and 3)

watching 10-min lecture and 5-min motivational video on SDM

(skills/role modeling). Twenty-four month implementation phase (June 2015–June 2017). |

A total of 91% (77/85) of patients received access to the PtDA at first consultation; 73% (56/77) of patients logged on to web based PtDA. PtDA delivery started in tumor board: tumor board letter reported 2 treatment options 58% (50/85) and indication for PtDA 34% (29/85). | 3b, 4a, 4b, 5b, 6, 8 |

| Sepucha et al., 2017, United States43 Mangla et al., 201844 |

Sepucha et al. 2017: evaluation of the impact of a quality

improvement project to increase use of orthopedic PtDAs and

examine whether PtDAs increase SDM in routine

care. Quality improvement methodology. Tertiary referral center. Mangla et al. 2018: to use quality improvement methodology to test methods of PtDA delivery to increase use of 4 orthopedic PtDAs (as listed above). Quality improvement methodology. Secondary care (large orthopedic hospital department) and 18 primary care practices. |

Four PtDAs for orthopedic treatment/management options: 1) Treatment Choices for Knee Osteoarthritis (42-min DVD; 38-page booklet); 2) Treatment Choices for Hip Osteoarthritis (44-min DVD; 40-page booklet); Treatment Choices for Herniated Disk (44-min DVD; 40-page booklet); 4) Treatment Choices for Spinal Stenosis (44-min DVD; 40-page booklet). Sent to patient ahead of the consultation if feasible. Process of determining eligibility for PtDA and subsequent distribution process differed depending on condition (e.g., automated via electronic medical system and sent before consultation or by specialist and handed to patient during consultation). | Single academic hospital serving a tertiary referral center.

Clinicians and staff at this site were already aware of and able

to order PtDAs via the electronic medical record, which were

delivered after the consultation. This quality improvement

program aimed to increase the use of the PtDA by working with

primary care clinicians, specialists, and clinic staff to design

a more reliable process to identify eligible patients and to

send them the PtDA in advance of the visit (e.g., at the time of

referral from a primary care physician or at the time of

scheduling a visit for new patients. When a PtDA is ordered, it

automatically placed a note in the medical record documenting

that it was sent. Process could be adapted if needed (e.g.,

process for arthroplasty and spine services differed). One-time

bonus for targets reached (viewing/ordering PtDA). Integrated

into quality improvement programs with dedicated lead and

clinical champions. Eighteen-month implementation phase (2013–2014). |

A total of 65% (303/469) of patients were identified by surgeons as eligible to be sent home with PtDA, indicated by automatic not in patient record; 62% (188/303) of these patients reported reading the entire PtDA. | 6, 7 |

| Stacey et al., 2015, Canada45 | Evaluate a sustainable approach for implementing a PtDA for

adults with cystic fibrosis (CF) considering referral for lung

transplantation. Prospective pragmatic observational study. Eighteen adult CF clinics within 8 different provincial health care systems in Canada. |

Printed copies and web-based version of the PtDA. Sent to patients ahead of consultation to discuss possible referral. Patient asked to complete PtDA on their own, which produces a 1-page summary report. This is shared and discussed with the clinician during the appointment and also filed in the patient’s medical records. | Health care professionals involved in the care of adults with CF

invited to participate in implementation study. Of 23 CF

clinics, 18 participated. Various implementation interventions,

including 1) a 5-h knowledge/skills workshop (participants

received monetary honorarium), 2) Ottawa Decision Support

Tutorial (online) offered to those who could not attend

workshop, 3) access to the PtDA (paper and online), and 4)

conference calls every 3 mo in the first year, then twice a year

(reinforce learning and provide support). Guided by the

“Knowledge to Action” framework. Project duration: 24 mo. |

Across 15 clinics, 18 of 62 CF patients used PtDA (29%) at baseline. After initiating implementation interventions, 15 clinics reported that PtDA was used by 58 of 68 patients (85%) in year 1 and 54 of 59 (92%) in year 2. | 7 |

| Stacey et al., 2018, Canada46 | Compare 2 strategies for implementing PtDAs in clinical pathways

for men with localized prostate cancer. Comparative case study (mixed methods). Secondary care, 2 academic teaching hospitals. |

Case 1: Video and booklet version of PtDA containing information

about prostate cancer treatment (including benefits and harms),

values clarification exercise, and video patient testimonials.

Also given decision quality and SURE questionnaire. Handed to

patient during initial appointment (biopsy result); urologist

met patient and instructed nurse to provide the PtDA to the

patient for the next in-person appointment; clinician also

received results of decision quality and SURE questionnaire

(also put on file). Nurse (some trained in decision coaching)

available by phone and next appointment. Case 2A: PtDA similar to version used in case 1 but adapted into a PowerPoint presentation and sent via email (did not include video patient testimonials). Patient called by nurse with biopsy results and then sent PtDA via email (or mailed version used in case 1 if they did not have email access). Asked to review ahead of in-person appointment. Trained nurse reviewed PtDA with patient and answered any questions; appointment then scheduled with urologist if patient’s preferences was to discuss options. |

Guided by the “Knowledge to Action” Framework. Nurses offered 3.5-h workshop using Interprofessional Shared Decision Making Model. Open to all health care professionals, but only nurses, social workers, and policy makers attended. Case 1: 24 mo (January 2011–December 2012) Case 2: 24 mo (January 2014–December 2015) |

Case 1: 158/688 men (23%) received the PtDA. Consistent pattern

of PtDA use over a 2-y period. Case 2A: 265/270 men (98%) received PtDA. Consistent pattern of use over 2 y, but decline in volume used over time. |

7 |

| PtDA first used during decision-making consultation | |||||

| Bonfils et al., 2018, United States (47) | To explore the implementation process of an SDM intervention,

CommonGround, which uses peer specialists and a computerized

decision support center to promote

SDM. Mixed-methods. Four treatment teams in a large community mental health center. |

Computer-based program for people with mental illness housed in the Decision Support Center: access facilitated by “peer specialists” (coaching). Completed prior to decision-making consultation with psychiatric provider. Provider can view “health report” that is produced and can updated with agreed treatment plan. | Four teams chosen due to previous successful implementation

program with different intervention. Target programs agreed with

the teams. Visits to established implementation sites arranged.

Implementation coach (fully trained in CommonGround) assigned to

team, monthly conference calls during early implementation. All

staff trained and new sessions provided for new

staff/refreshers. Implementation overseen by leadership team,

including 3 fidelity visits. Twenty-two month implementation phase (May 2013–March 2015). |

A total of 64% (107/167) of clients used the PtDA at least once by filling in preconsultation appointment goals. Completion was 74% for ACT team clients and 56% for outpatient clients. After 2 y, the center ceased using the PtDA. | 1, 2, 3c, 4a, 7 |

| Brinkman et al., 2017, United States48 | Develop and reliably implement a decision aid to facilitate SDM

between clinicians, patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis,

and their families around medication choices for treatment of

inflammatory arthritis. Quality improvement methodology. Primary care sites (rheumatology). |

Paper-based medication choice cards for juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Distributed to patient (and family member) during medication change discussion consultations. | Overseen by the project improvement team (quality improvement

consultant, clinician researchers). Train-the-trainer workshop

was held to train key clinician champions on the use of the

medication decision cards so that they could train other

clinicians at their sites on correct use. A supporting video was

also developed and shared with the sites. Each site developed

process maps to identify how the DA would fit their process.

Teams also did iterative plan-do study-act cycles to identify

implementation processes. Six-month implementation phase (March–August 2014). |

In 35% of visits in which drug use was discussed, the PtDA (medication choice cards) was used. The PtDA was used as intended (parent was asked to pick the first card to discuss) in 68% of visits where the PtDA cards were used. | 4b |

| Dahl Steffensen et al., 2018, Denmark14 | To report key lessons on the setup of a Center for Shared

Decision-Making at the Patient’s Cancer Hospital in Vejle

(Denmark). Case study report. Specialized cancer center in large public hospital. |

Generic PtDA developed by clinicians and School of Design. The PtDA template was developed to adhere to the certification and quality criteria set by IPDAS. Various paper-based versions tested for the following settings (using generic PtDA framework): adjuvant breast cancer, diagnostic setting of suspicion of lung cancer, genetic testing, ovarian cancer, colorectal cancer, and herniated disc. Generic preparation sheet viewed by patients before the clinical encounter and PtDA introduced during encounter. | Two-day training program in SDM offered to all clinicians by

department leaders. Supported by strong leadership, commitment

from hospital CEO and CMO. PtDA platform offered in web-based

system; health care providers log in and use platform to build

and develop PtDAs tailored to their specific needs, based on the

adjustable template (“build your own PtDA”). Duration of first implementation phase: 3 y. |

No data on actual use. The Center has moved into the next phase and started a systematic SDM implementation program across all hospitals in the region of Southern Denmark (2019). |

3a, 3c, 4a, 5a, 5b, 6 |

| Johnson et al., 2010, Indonesia/Mexico/Nicaragua49 | To describe the development and testing of a family planning

counseling tool and to discuss challenges and requisites for

shifting to SDM from the extremes of decision making dominated

by the provider, on one hand, or unaided by the provider, on the

other hand. Mixed-methods (pre and post design). Various contexts within health care settings where family planning is discussed (e.g., maternity hospitals, primary/public health clinics). |

Dual-purpose PtDA (patient facing) and “job aid” (clinician facing). Double-sided flip chart presenting contraception options, used during a counseling session between client and provider. Adapted to local language. | Implemented in 3 family-planning teams: Indonesia, Mexico,

Nicaragua. Two- to 4-day training workshop delivered to

providers ahead of implementation in routine

care. Implementation phase: 4 mo in Nicaragua, 1 mo in both Mexico and Indonesia. |

No clear data reported on actual use of the 2-sided flipchart PtDA. A total of 357 videotaped consultations showed total consultation time 550 s. Mean number of seconds of eye contact on PtDA: patient = 187, provider = 170. | 5b, 6 |

| Joseph-Williams et al., 2017, United Kingdom13 Lloyd et al., 201350 THF 2013 |

To understand what works and what does not work in implementing

SDM in routine NHS settings. Quality improvement methodology (mixed methods). Eight primary care practices and 7 secondary care hospital teams (head and neck cancer, pediatric ENT, renal, maternity, urology, and 2 breast cancer teams). Across 2 large university local health boards/trusts in the United Kingdom. |

Various paper-based brief PtDAs (1–4 pages) across a range of conditions, distributed to and used with patients during consultations. Patient given PtDA to use after consultation (when decision was not being made in the same consultation). | Implementation overseen by university-based team. Four dedicated

facilitators supported teams to develop their own

interventions/measures/implementation strategies and conduct

PDSA cycles. Key organizational leaders (e.g., medical

director), clinical champions, and patients part of leadership

team. Eighteen-month implementation program (August 2010–February 2012). All teams designed tools/interventions to use with PtDA as part of the program, and actual implementation phases varied across the teams. All teams attended SDM training as part of the program. |

No data on actual use. | 1, 2, 3a, 3b, 3c, 4a, 4b, 5a, 5b, 6, 7, 8 |

| Munro et al., 2019, United States51 | To explore the feasibility and acceptability of 2 interventions

for facilitating SDM about contraceptive methods with a

particular focus on factors that influenced their implementation

by clinical and administrative staff. Qualitative study (embedded within a 2 × 2 factorial cluster randomized controlled trial). Twelve clinics in which contraceptive counseling takes place. |

Two types of intervention designed to support female

contraceptive options: Patient targeted: “activation” materials delivered in the clinic, before appointment (video on tablet computer and paper-based card reinforcing questions to ask during consultation). Provider-targeted: set of 7 one-page paper-based PtDAs on contraceptive methods (tear pads). Used by HCP during patient visit. Short SDM/PtDA training video and written guidance. Not all groups received PtDAs. |

Twelve intervention arm clinics (patient targeted; provider

targeted; both) of a total 16 total clinics in trial. Each

clinic identified a senior staff member to liaise with research

team and facilitate implementation. The research team provided a

group orientation on the trial. After randomization, an

orientation on the intervention was provided, during which the

teams worked collaboratively to develop their own implementation

strategy, considering patient workflow and routinely used

patient/counseling materials. Short SDM/PtDA training video and

written guidance on how to use PtDAs provided prior to

implementation in 8 of 12 intervention arms. Duration not reported. |

No data on actual use. | 3a, 3b, 4a, 4b, 5a, 5b, 6, 8 |

| PtDA distributed to providers | |||||

| Feibelmann et al., 2011, United States52 | To trial a structured approach to disseminating breast cancer

PtDAs to community breast cancer sites and to explore the

factors associated with successful, sustained implementation of

PtDAs by the providers at these sites. Longitudinal study data examined, and cross-sectional mail/telephone survey. Cancer centers, hospitals, private practices, and patient resource centers. |

Videos/DVDs and accompanying booklet for 5 different breast cancer decisions (ductal carcinoma in situ, early-stage surgery, breast reconstruction, adjuvant therapy, metastatic cancer). Designed to be handed out by provider during consultation, for patient to watch/read following consultation. Limited further information on distribution/intended use. | Sites contacted to ascertain interest; 93 of 195 signed

agreements to distribute, 57 of 93 distributed PtDA to at least

1 patient. Sites identified 1 contact person. Limited further

information regarding implementation planning, adaption into

clinic workflows, etc. Duration not reported. |

A total of 61% (57/93) of US hospitals/practices that signed agreements to adopt PtDAs reported distribution of PtDA to at least 1 patient; 49% (46/93) reported still using the PtDA 1 y later. | 3b, 3c, 4a, 4b, 5a, 8 |

| Giguere et al., 2014, Canada53 | To measure the value and intention to use decision boxes

(Dboxes) in practice and to describe barriers and facilitators

of their use. Observational quality improvement study (mixed methods with sequential explanatory design). Six primary care practices. |

Eight different Dboxes (written in French and English) covering the following health care decisions: 1) cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs) to reduce the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease, 2) acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease, 3) fecal occult blood test (FOBT) to screen for colorectal cancer; 4) serum integrated test to screen women for fetal trisomy 21 (prenatal), 5) statins for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (statins), 6) BRCA1/2 gene mutation test to evaluate the risks of breast and ovarian cancer (BRCA), 7) bisphosphonates to prevent osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women (osteo), and 8) prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test to screen men for prostate cancer. Delivered to clinician via email before consultation to help clinician recognize equipoise and the need to share decision with patient and to support provision of information about risks and benefits of options. | Eight different Dboxes were distributed to clinicians (1 each week for 8 wk of the implementation study). Limited information regarding agreed implementation. | No data on actual use. PtDA (Dboxes on tests or drugs) were intended to be reviewed by clinicians before consultation. Forty percent (190/472) of clinicians reported intention to use the PtDA. | 3c, 4b, 5b, 7 |

| Hsu et al., 2013, United States54 Hsu et al. 201655 |

Hsu 2013: To identify factors that promote and impede

integrating PtDAs into clinical practice in a large health care

delivery system. Qualitative case study methodology. Speciality care: orthopedics, cardiology, urology, women’s health, general surgery, neurosurgery. Hsu 2016: build on Hsu 2013 to understand how differences in provider attitudes across specialities may affect PtDA implementation and how provider attitudes shift after PtDA implementation. Qualitative case study methodology. Speciality care: orthopedics and cardiology. |

DVD and booklet format. Patient could also view PtDA via patient

portal. Hsu 2013: 12 PtDAs (35–55 min) for several elective surgery procedures: orthopedics (hip osteoarthritis, knee osteoarthritis), cardiology (coronary heart disease), urology (benign prostatic hyperplasia, prostate cancer), women’s health (uterine fibroids, uterine bleeding), general surgery (early stage breast cancer, breast reconstruction, ductal carcinoma in situ), and neurosurgery (spinal stenosis, herniated disk). Hsu 2016: Three PtDAs for the following elective surgical procedures: orthopedics (hip osteoarthritis, knee osteoarthritis), cardiology (coronary heart disease). Designed for patient to view/read before consultation with specialist (some exceptions because of the nature of the condition, e.g., abnormal uterine bleeding). |

System-wide implementation across Group Health’s Western

Washington Group Practice Division (serving 366,000 members)

across 6 speciality service lines. Implementation evaluation

conducted by Group Health Research Institute, nonproprietary,

public interest arm of Group Health. PtDAs provided free of charge for first 2 y of demonstration project. Twenty-four-month implementation phase. |

In the 24-mo implementation period, 9827 PtDAs were distributed to patients, via US mail, free of charge. The PtDAs could be ordered via electronic health record or patient portal. | 2, 6 |

| MacDonald-Wilson, 2017, United States56 | To investigate the implementation of decision support practices

by community mental health centers and the impact of decision

support on organizational- and individual-level

outcomes. Quality improvement methodology (mixed methods). Fifty-two community mental health centers. |

Total number of PtDA topics unclear, but sites asked to choose 1 PtDA to implement from a range of topics (e.g., residential rehabilitation, psychiatric rehabilitation, outpatient drug and alcohol services program). Limited further information on format/intended use but appears to be an online library of PtDAs that include decisional balance worksheets. Access given by provider. | Implementation at 52 community mental health centers within

network of parent organization, who volunteered to take part in

initiative. Each site asked to select their own intervention and

develop own implementation plans using PDSA cycles. Learning

collaborative approach established. Parent organization

supported all aspects of implementation (staff training,

implementation of intervention, information gathering/analysis).

Quality improvement team established at each site, including 1

member of senior leadership, a quality clinician, direct service

worker, and person in recovery. Trained learning collaborative

facilitators provided support throughout. Twelve-month implementation phase. |

During the 12-mo implementation period, 52% (27/53) of agencies reached the milestone that 80% of the staff used a PtDA with at least 1 patient each month. | 3c, 8 |

| Scalia et al., 2017, United States57 | To use normalization process theory to explore how and why 2

separate health care organizations in the United States had

spontaneously adopted Option Grid™ PtDAs (for total of 8 health

care issues) in routine clinical practice and investigate

factors that facilitated routine use. Case study (semistructured interviews). Two large sites (1 New York, 1 Minneapolis), offering a range of medical and dental services, including family practice, internal medicine, pediatrics, obstetrics and gynecology, and nurse midwifery. |

Option Grid decision aids (paper based, 1 page) for patients considering the following issues: hypercholesterolemia, antibiotics for pharyngitis, sciatica, knee pain, PSA test, Dupuytren’s contracture, carpal tunnel syndrome, trigger finger. Designed for use in consultation; clinician hands PtDA to patient, and patient takes home. | Included sites were chosen as they independently identified and

chose to embed the PtDAs into existing workflows and had been

and routinely implementing Option Grids for at least a 1-y

period beforehand. CapitalCare site in New York (primary care

organization with 65 physicians across 10 sites) used a total of

5 Option Grid PtDAs and collected quantitative data via the

electronic health record. HealthPartners Speciality Center in

Minnesota (speciality center providing orthopedic care with more

than 600 physicians), used 3 Option Grids (Dupuytren’s disease,

carpal tunnel syndrome, and trigger finger); the lead hand

surgeon had been an editor for these Option Grids that were used

during routine implementation. Unclear how many of the

clinicians at each site were involved in routine implementation,

but 23 interviews conducted with nurses, physicians, hospital

staff, and stakeholders across both sites. Not implementation study per se. But both sites had been routinely using relevant Option Grids for at least 1 y before the study. |

Number of sites using Option Grid (total number of times

decision aid given to patients). Capital Care (10 sites): High cholesterol: 6 (887) Pharyngitis: 2 (163) Sciatica: 3 (80) Knee pain: 1 (41) PSA: 1 (32) HealthPartners: Dupuytren’s contracture: 2 (100) Carpal tunnel: 2 (200) Trigger finger: 2 (200) estimated |

3c, 4a, 4b, 6, 7 |

| Scalia et al., 2018, Poland58 | To study the use of Option Grid PtDAs in a sample of clinics in

Warsaw, Poland, and measure their impact on SDM. Mixed methods (pre and post design). Three large private health care clinics (patients with heartburn, osteoarthritis of the knee, or considering statins). |

Option Grid decision aids (paper based, 1 page) for patients who had heartburn, osteoarthritis of the knee, or were considering statins. Designed for use in consultation. Clinician hands patient PtDA, and patient takes home. Translated from English to Polish. | Clinicians employed at 3 large private clinics were invited by

medical director to participate (selected on basis of high

patient volume). Thirteen clinicians participated across 3 sites

(5 gastroenterologists, 3 orthopedic surgeons, 3 family doctors,

and 2 cardiologists). Pre–post design; following baseline, all

clinicians underwent 1-h training intervention (to increase

understanding of SDM skills/model, familiarize clinicians with

Option Grids and CollaboRATE measurement instrument, and

increase confidence in skills to use Option Grid with patients)

and were given access to relevant Option Grids. Duration not reported. |

Approximately 700 physicians were involved in 2 settings. Total number of PtDAs given to patients in 2 years = 1700. In one setting, 6 of 10 sites used PtDA; 4 sites did not. Physicians reported being selective in their use of the Option Grid, making judgments based on patient characteristics. | 6 |

PtDA, patient decision aids; IPDAS, International Patient Decision Aid Standards; CEO, chief executive officer; CMO, chief medical officer; SDM, shared decision making; NHS, National Health Service; ENT, ear, nose, and throat; HCP, health care professional.

Program Theories: What Works in Implementing PtDAs into Routine Clinical Settings?

A total of 124 explanatory if-then statements were extracted from the included articles. Using the CFIR32 to help understand factors that might influence intervention implementation and effectiveness, these statements were refined into 8 program theories (CMO configurations). The program theories are described below, organized under relevant domains of the CFIR,32 and are summarized in Table 2 with supporting data (“I” is used in the results to denote features of the implementation strategy, e.g., skills training session, automated electronic delivery of PtDA). None of our theories mapped to domain II of the CFIR. Domains are not mutually exclusive, and some CMO configurations could map to more than 1 of the CFIR domains; however, for brevity and clarity, we mapped the 8 program theories to the most relevant domain. Because of the limited number of included studies, CMOs have been presented generically, with limited contextual reference to specific diseases or decisions, with the exception of theory 2, which is specific to crisis-driven and life-threatening situations.

Table 2.

Implementing PtDAs in Routine Clinical Settings Program Theories: Context-Mechanism-Outcome Configurations Identified from 29 Articles (23 Studies)

| Context (C)–Mechanism (M)–Outcome (O) Configurations (I = Intervention) | Source Article |

|---|---|

| I – Intervention characteristics | |

| Theory 1: PtDA complexity: simple tools for busy settings | |

| PtDAs are being implemented in busy health care systems with established processes/interventions (clinical and nonclinical) (C). When more complex PtDAs are selected (e.g., increased number of additional PtDA-related tasks; technical knowledge/support required; potential for technical/access issues; increased length of PtDA; unable to easily view PtDA without additional resources, e.g., computer program), HCPs feel that the PtDA competes with existing practice and is more difficult to integrate into their existing system (M), making them less likely to use the PtDA (O). | Bonfils 2018; Brackett 2015; Dontje 2013; Lloyd 2013; THF 2013 |

| III – Inner setting | |

| Theory 2: Crisis-driven and life-threatening situations: urgent care needs prioritized over decision support needs | |

| If the PtDA is implemented in a setting that is crisis driven or deals with life-threatening issues and diagnoses, which sometimes evoke a strong emotional response from the patient (C), HCPs believed that the immediate and urgent needs of the patient are more important (e.g., safety/reassurance/emotional support) than decision-making needs (M), and they were less likely to use the PtDA as prescribed (O). | Bonfils 2018; Hsu 2013; Hsu 2016; Lloyd 2013; THF 2013 |

| Theory 3: Bringing the whole team on board: establishing a common goal, senior-level buy-in, and distributing PtDA tasks appropriately | |

| 3a: Making sure administrative staff also understand PtDA purpose and intended use | |

| When PtDAs were delivered in settings in which the entire health care team (including all administrative and clinical staff) have been introduced to the PtDA (C), via staff briefing sessions or training (I), administrative staff understood the purpose and intent of the PtDA (M), which meant that they were more supportive and motivated to take part in PtDA coordination/distribution tasks (O). | Berry 2019; Dahl Steffensen 2018; Lin 2013; Munro 2019; Stacey 2018; THF 2013 |

| 3b: Distributing PtDA tasks to appropriate team members | |

| PtDAs are typically implemented in multidisciplinary teams that include various clinical, support, and administrative staff (C). When appropriate PtDA tasks are distributed and delegated to the appropriate individuals across the whole team (I), greater coherence exists among the team about the PtDA purpose and intent; individuals are motivated by the distribution of tasks (e.g., “I’m not in this by myself”), particularly when senior clinical staff engage; they understand how their task fits with the broader process; and they take ownership over their task (M), making the PtDA more likely to be distributed and used as planned (O). | Berry 2019; Feilbelman 2012; Munro 2019; Lin 2013; Mangla 2017; Savelberg 2019; Stacey 2018; THF 2013 |

| 3c: Dedicated and ongoing clinical leadership | |

| HCPs work in ways that align with the expectations and priorities set by the clinical leadership (C). A consistent clinical leader, “champion(s),” or leadership team) (I) plays an important role in continued buy-in through ongoing training for new staff, promoting positive attitudes toward the approach, presenting feedback on PtDA outcomes, supporting reflection and refinement of PtDA processes, and ensuring the approach aligns with key priorities of the health care organization (M). Lack of continued clinical leadership, or staff turnover of the clinical champion leading the work, can be detrimental to motivation and the skill set needed to use the PtDA (M) and lead to discontinued use (O). | Berry 2019; Bonfils 2018; Dahl Steffensen 2018; Feibelman 2017; Giguere 2014; Joseph-Williams 2017; Lin 2013; Lloyd 2013; MacDonald-Wilson 2017; Scalia 2017; Stacey 2018; THF 2013 |

| IV: Characteristics of individuals | |

| Theory 4: Activating and supporting HCPs to deliver PtDAs: HCPs aware, trained, and motivated to change practice | |

| 4a: Raising awareness of PtDA purpose and intended use | |

| When PtDAs are implemented in teams that do not understand the purpose of the PtDA or its intended use (C), they are less likely to use the PtDA as intended (O), because they do not understand the benefits for patients nor the PtDA role in supporting patient decision making (M). Introductory training sessions were provided to all team members about the purpose of the PtDA and its benefits (for patients and HCPs [I], helps teams decide how to integrate PtDAs into existing work practices [M], which in turn makes it more likely that the PtDA will be adopted in routine care [O]). | Berry 2019; Bonfils 2018; Dahl Steffensen 2018; Feibelman 2017; Lin 2013; Lloyd 2013; Munro 2019; Savelberg 2019; Scalia 2017; THF 2013 |

| 4b: Supporting SDM skills development | |

| When HCPs lack knowledge of SDM skills (C), they will be less likely to use the PtDA (O), as they do not have confidence in their SDM/PtDA delivery skills and/or they do understand how SDM differs from usual practice and therefore do not understand why the PtDA needs to be used (M). SDM skills workshops delivered prior to PtDA implementation (I) provided opportunity for HCPs to practice and develop confidence in SDM/PtDA delivery skills, helping HCPs to understand how SDM differs from current practice and thus the importance of PtDAs (M), which results in increased use and proficiency in using PtDAs with patients (O). | Brinkman 2017; Feibelman 2017; Giguere 2014; Joseph-Williams 2017; Lin 2013; Lloyd 2013; Mangla 2018; Munro 2019; Savelberg 2019; Scalia 2017; Stacey 2015; THF 2013 |

| Theory 5: Preparing and encouraging patients to use PtDAs: explicit invitations from clinical team to use PtDA before and during decision-making consultations | |

| 5a: Explicit invitations to use PtDA before decision-making consultations | |

| Many patients have no experience receiving or using a PtDA (C). When the clinical team sends explicit invitations (explaining the purpose/process of using PtDA and encouraging patients to engage with PtDA before the decision-making consultation [I]), patients better understand the relevance and purpose of the PtDA, they perceive that their role in the decision-making process is valid and desired, and they are reminded to use the PtDA (M), thus making them more likely to actively engage with the PtDA and use it to help inform their decision with a HCP (O). | Berry 2019; Dahl Steffensen 2018; Dharod 2019; Feibelman 2017; Joseph-Williams 2017; Krist 2017; Munro 2019; THF 2013 |

| 5b: Explicit invitations to use PtDA during decision-making consultations | |

| Significant power imbalances exist in some consultations, with many patients believing they cannot participate in SDM (C). When HCPs provide an explicit invitation during the decision-making consultation to further discuss the PtDA, preferably accompanied by handover of the PtDA (or duplicate copy, if delivered before consultation), (I) patients will feel that their contribution is valued and sought by the HCP and understand the relevance of the PtDA in the decision-making discussion (M), thus making them more likely to share their preferences, ask questions, and engage in decision making (thus using the PtDA for its intended purpose) (O). | Dahl Steffensen 2018; Giguere 2014; Johnson 2010; Joseph-Williams 2017; Munro 2019; Savelberg 2019 |

| V: Process | |

| Theory 6: Collaborative PtDA development and implementation planning: early and meaningful involvement of clinical teams and providers | |

| HCPs and providers have preexisting approaches/processes to communicate options to patients (C). Early involvement of (or ideally, initiation by) clinical teams/providers in the development of the PtDA content/implementation planning (I) creates a sense of ownership, increases buy-in, helps to legitimize content, and ensures the PtDA (content and delivery) is consistent with current practice (M), making it more likely to be integrated into routine care (O). | Dahl Steffensen 2018; Hsu 2016; Hsu 2013; Johnson 2010; Joseph-Williams 2017; Lin 2013; Lloyd 2013; Munro 2019; Savelberg 2019; Scalia 2017; Scalia 2018; Sepucha 2017; THF 2013 |

| Theory 7: Earlier distribution of PtDAs: systematizing delivery of PtDAs to all eligible patients before decision-making consultations | |

| In clinical environments with limited staff resources, short appointment times, or short time frames between diagnosis and decision discussion (C), preidentifying eligible patients and systematizing (ideally via IT systems) the timely delivery, completion, and return of the PtDA to clinicians prior to decision-making consultations (I) decreases clinicians’ concerns about time to coordinate and do SDM and prompts PtDA/SDM use during consultations (M), improving reach and integration of the PtDA (O). | Belkora 2012; Berry 2019; Bonfils 2018; Brackett 2015; Dharod 2019; Giguere 2014; Krist 2017; Lin 2013; Mangla 2018; Scalia 2017; Sepucha 2017; Stacey 2015; Stacey 2018; THF 2013 |

| Theory 8: Linking with “learning health care systems”: using measurement to show how PtDA outcomes link with and improve key organizational priorities | |

| When organizational priorities align with PtDA outcomes and a “learning health care system” (e.g., quality improvement practices/teams) exists within an organization (C), PtDAs should be implemented alongside routinely collected measures that the organization values (I). These measures demonstrate the improvements that result from using PtDAs and also demonstrate to clinical teams that the use of PtDAs is valued by the organization, which makes PtDAs more likely to be integrated into routine care (O). | Feibelman 2017; Joseph-Williams 2017; Lloyd 2013; MacDonald-Wilson 2017; Munro 2019; Savelberg 2019; THF 2013 |

PtDA, patient decision aids; HCP, health care professional; SDM, shared decision making; IT, information technology.

I. Intervention Characteristics

Theory 1: PtDA complexity: simple tools for busy settings

PtDAs are being implemented in busy health care systems with established processes/interventions (clinical and nonclinical) (C). When more complex PtDAs are selected (I; see Table 2 for examples), HCPs feel that the PtDA competes with existing practice and is more difficult to integrate into their existing system (M), making them less likely to use the PtDA (O).

Box 2.

Definitions of the 5 Major Domains of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research32

| I: Intervention Characteristics |

|---|

| Features of an intervention that might influence implementation; 8 constructs: intervention source, evidence strength/quality, relative advantage, adaptability, triability, complexity, design quality, cost |

| II: Outer Setting |

| Features of the external context that might influence implementation (economic, political and social context within which the organization resides); 4 constructs: patient needs and resources, cosmopolitanism, peer pressure, external policies and incentives |

| III: Inner Setting |

| Features of the implementing organization that might influence implementation (e.g., structural, political, cultural contexts through which implementation will proceed); 12 constructs: structural, networks/communications, culture, tension for change, compatibility, relative priority, organizational incentives and rewards, goals and feedback, learning climate, leadership engagement, available resources, access to information/ knowledge |

| IV: Characteristics of Individuals |

| Characteristics of individuals involved in implementation that might influence implementation; 5 constructs: knowledge and beliefs about intervention, self-efficacy, individual stage of change, individual identification with organization |

| V: Process |

| Strategies or tactics that might influence implementation; 4 constructs: planning, engaging, executing, reflecting and evaluating |

Five articles contribute data to the theory that less complex tools are more likely to be integrated into routine care.35,37,47,50,59 When PtDAs were perceived as more complex by the clinical team, especially those PtDAs that required technical knowledge and support, and required an increased number of PtDA-related tasks and personnel time, the teams felt that they competed with existing practice, were too resource intensive, and were more difficult to embed.35,37,47 Some HCPs reported that the shorter and less complex tools (e.g., brief in-consultation paper-based tools) were preferable as they fit better with existing practices and required limited additional resources.35,59,50

III: Inner Setting

Theory 2: Crisis-driven and life-threatening situations—urgent care needs prioritized over decision support needs

If the PtDA is implemented in a setting that is crisis driven or deals with life-threatening issues diagnoses, which sometimes evoke a strong emotional response from the patient (C), HCPs believed that the immediate and urgent needs of the patient are more important (e.g., safety/reassurance/emotional support) than decision-making needs (M), and they were less likely to use the PtDA as prescribed (O).

Five articles support the theory that PtDAs are less likely to be embedded by HCPs in teams that are typically crisis driven or deal with life-threatening issues.47,54,55,59,50 When exploring implementation of a PtDA within a community mental health setting, Bonfils et al.47 found that staff would often need to prioritize immediate patient needs over PtDA distribution; for example, “we’re a crisis-driven clinic and you could use this [resource], and you could use that [resource], but then they’re like ‘well they don’t have a house,’ so some of that stuff gets in the way.” Life-threatening situations54 also present challenging contexts to embed PtDAs, where HCPs tend to prioritize supporting the immediate health care needs, and sometimes the more emotional needs, of the patient.

Theory 3: Bringing the whole team on board: establishing a common goal, senior-level buy-in, and distributing PtDA tasks appropriately

3a: Making sure administrative staff also understand the PtDA purpose and intended use

When PtDAs were delivered in settings where the entire health care team (including all administrative and clinical staff) have been introduced to the PtDA (C), via staff briefing sessions or training (I), administrative staff understood the purpose and intent of the PtDA (M), which meant that they were more supportive and motivated to take part in PtDA coordination/distribution tasks (O).

Six articles provide data for this theory.14,34,40,46,51,59 Various studies reported that PtDA integration was more successful when all members of the clinical team had been introduced to the PtDA and not only the HCPs who would be using the tool. When administrative staff understood the purpose of the PtDA and how it fit into the patient pathway, they were more supportive of its use and motivated to support the distribution processes as part of their administrative role. Joseph-Williams et al.13 reported the “shared understanding” that emerged when all team members were involved and how reception staff played a key role in introducing the concept of choice at the very start of the patient journey as well as in distributing materials. Other studies also found that administrative staff played a critical role in integrating the PtDA into workflows40,51; they were responsible for 73% of PtDA distribution in the study by Lin et al.40 Berry et al.34 further highlighted the importance of “coherence” about purpose and use across the entire team (clinical and administrative); when the administrative staff members knew very little about why a PtDA was important or being used, this acted as a barrier to implementation.

3b: Distributing PtDA tasks to appropriate team members

PtDAs are typically implemented in interprofessional teams that include various clinical, support, and administrative staff (C). When appropriate PtDA tasks are distributed and delegated to the appropriate individuals across the whole team (I), greater coherence exists among the team about the PtDA purpose and intent, individuals are motivated by the distribution of tasks (e.g., “I’m not in this by myself”), particularly when senior clinical staff engage, they understand how their task fits with the broader process, and they take ownership over their task (M), making the PtDA more likely to be distributed and used as planned (O).

Eight articles support the theory that distributing PtDA tasks among a multidisciplinary team (clinical and nonclinical) is more likely to lead to the PtDA being distributed and used as planned.34,40,41,44,46,51,52,59 Lin et al.40 reported how a “team-based practice model,” in which clinic staff were empowered to distribute PtDAs, was more successful than a model that relied on physicians alone; however, they also noted that this model can only support, not substitute, HCP involvement in patient engagement. Whole-team involvement, particularly senior clinical staff, led to perceptions such as “I’m not in this by myself” and “this won’t be seen as my ‘little’ project,”13 which motivated individual team members to continue use of PtDAs. Conversely, Fiebleman et al.52 showed that when service physicians were not supportive of the PtDA, the remaining staff were less likely to use it. Omission of certain team members from the process (e.g., nurses not involved after use of PtDA)41 or inappropriate allocation of PtDA tasks to the wrong team member (e.g., reliance on physicians to order PtDAs)44 can lead to reduced fidelity in the way the PtDA is used and the subsequent SDM discussion and reduced distribution.

3c: Dedicated and ongoing clinical leadership

HCPs work in ways that align with the expectations and priorities set by the clinical leadership (C). A consistent clinical leader (“champion” or leadership team) (I) plays an important role in continued buy-in through ongoing training for new staff, promoting positive attitudes toward the approach, presenting feedback on PtDA outcomes, supporting reflection and refinement of PtDA processes, and ensuring the approach aligns with key priorities of the health care organization (M). Lack of continued clinical leadership or staff turnover of the clinical champion leading the work can be detrimental to motivation and the skill set needed to use the PtDA (M) and lead to discontinued use (O).

Twelve articles support this theory.13,14,34,40,46,47,50,52,53,56,57,59 Leadership from senior clinicians and managers plays an important role in determining whether teams use and continue to use the PtDA. Several studies found that a clinical lead, or “champion” played a significant role in making training available, prioritizing and keeping SDM and the use of the PtDA high on the agenda, conveying seriousness of intent, and ensuring evaluation data were being fed back to the team13,14,46,56—all which results in greater motivation and an improved skill set among the team, making it more likely that the PtDA use will be sustained. As one member of the obstetrics team said in the study by Joseph-Williams et al13: “once you use the big names, the well-respected consultants, people sit up and listen . . . that’s needed.” Scalia et al.58 reported how a champion orthopedic surgeon influenced colleagues by playing a significant role in PtDA development and demonstrating the benefit of using the tool. On the other hand, Berry et al.34 found that even when a designated lead was appointed, the absence of a clinical lead who is physically present in the clinic and seeing patients acted as a barrier to PtDA use.

IV: Characteristics of Individuals

Theory 4: Activating and supporting HCPs to deliver PtDAs: HCPs aware, trained, and motivated to change practice

4a: Awareness of PtDA purpose and intended use

When PtDAs are implemented in teams that do not understand the purpose of the PtDA or its intended use (C), they are less likely to use the PtDA as intended (O), because they do not understand the benefits for patients nor the PtDA role in supporting patient decision making (M). Introductory training sessions provided to all team members about the purpose of the PtDA and its benefits (for patients and HCPs [I]), helps teams decide how to integrate PtDAs into existing work practices (M), which in turn makes it more likely that the PtDA will be adopted in routine care (O).

Ten articles contributed data to support this theory.14,34,40,41,47,51,50,52,57,59 Implementation is unlikely to occur when teams are not familiar with PtDAs or lack awareness of the PtDA’s purpose and intended use. This was an important barrier to routine implementation. For example, one staff member in the study by Bonfils et al.47 of a mental health PtDA noted, “I think it’s underutilized because people don’t understand the richness of it . . . I don’t think they realize how much is on there [the PtDA].” When team members lack knowledge on why or how the PtDA should be used, they do not understand the benefits for patients or the role it plays in the decision-making process, which results in the PtDA being underused or misused.40,41,47 Conversely, when they are clear about the purpose and intended use, PtDA adoption is higher.50–52,59

4b: Supporting SDM skills development