Abstract

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related morbidity and mortality in the People’s Republic of China. Targeted therapies for patients with lung cancer, which depend on accurate identification of actionable genomic alteration, have improved survival compared with previously available treatments. However, data on the types of molecular testing often used in the People’s Republic of China, and how they have changed over time, are scarce. We explored the overall landscape of molecular testing of lung cancer in mainland People’s Republic of China in the past decade.

Methods

We distributed a stratified random sampling survey of molecular testing to 49 hospitals from members of the Molecular Pathology Collaboration Group of Chinese Anti-Cancer Association which was weighted by the numbers of lung cancer cases in seven different geographic regions in mainland People’s Republic of China from 2010 to 2019. The questionnaire contained four parts for all respondents. The questionnaire ascertained the use of approved in vitro diagnostic (IVD) devices published by the Center for Medical Device Evaluation, National Medical Products Administration of the People’s Republic of China.

Results

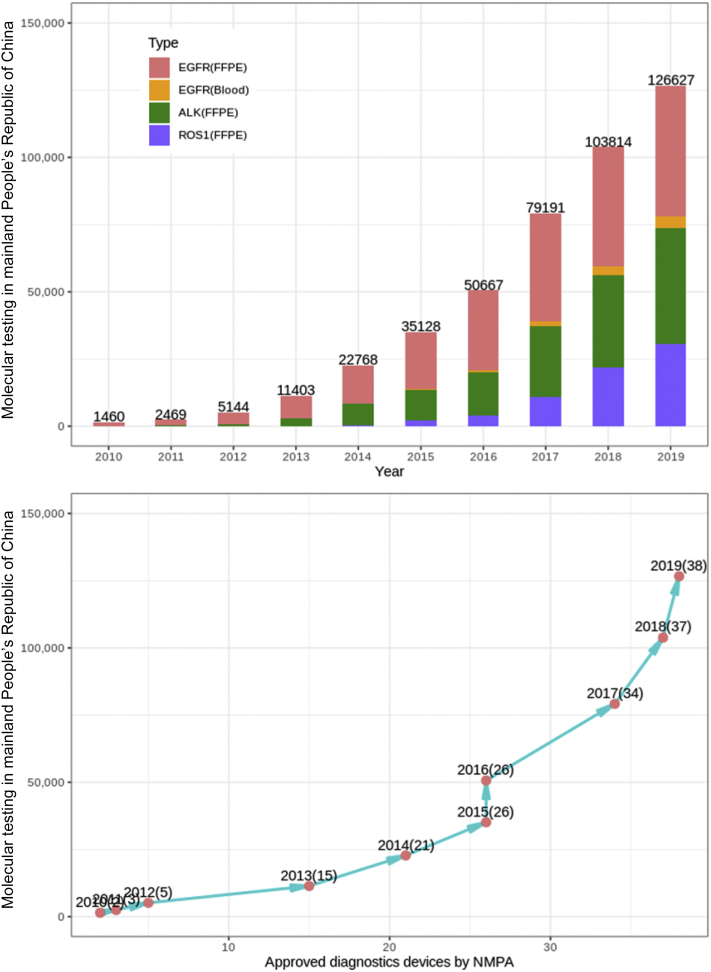

A total of 226,227 NSCLC specimens were tested from 2010 to 2019 in the selected hospitals. The annual number of initiated molecular tests increased over time (p < 0.0001), with an average annual growth rate of 31.8%. A notable increase in the number of molecular tests occurred during 2014 and 2016, which coincided with the approval of the National Medical Products Administration to IVD devices. For the diagnosis of molecular subtypes, EGFR mutation testing was first conducted in year 2007, followed by ALK translocation testing in 2010 and ROS1 in 2011. For other rare genetic variations in NSCLC, BRAF mutation testing was first launched in 2012, MET exon 14 skipping mutation in 2014, HER2 exon 20 mutations in 2017, and RET translocation in 2015. A markedly uneven distribution was also observed in the geography of leading units with the largest number of leading units located in east People’s Republic of China (34.7%, 17 of 49) and the smallest number located in northwest People’s Republic of China (6.1%, 3 of 49). The growth trends we observed illustrate the progress and increasing capability of molecular testing of lung cancer achieved in mainland People’s Republic of China in the decade from 2010.

Conclusions

In the decade 2010 to 2019, progress and increased capability of molecular testing of lung cancer were achieved in mainland People’s Republic of China. Further efforts should address the clinical application of next-generation sequencing technology, rare genomic aberrations, and the balance between novel genomic testing techniques and the approval of IVD products.

Keywords: Lung cancer, Molecular testing, Trends, NMPA, China

Introduction

In 2018, a total of 2.09 million new cases and 1.80 million cancer-related deaths of lung cancer occurred globally, ranking first among all cancer types.1 Annual lung cancer cases and deaths have been increasing in the People’s Republic of China since 2000, and it is estimated that lung cancer mortality in the People’s Republic of China may increase by approximately 40% between 2015 and 2030.2 NSCLC is the major pathologic subtype of lung cancer and application of novel targeted therapies for patients with advanced NSCLC with specific genetic alterations (driver mutations) has dramatically improved response rate and survival compared with chemotherapy.3, 4, 5 Targeted therapies for patients with EGFR activating mutations (EGFR), ALK and ROS1 rearrangements, have been approved in many parts of the world, and patient selection for molecular targeted therapies depends on accurate and timely identification of actionable genomic alterations.10, 6, 7, 8, 9 In addition, targeted therapies are available in clinical trials or in certain parts of the world as standard of care for patients with rare genetic variations, such as BRAF V600E, HER2, KRAS, MET exon 14 skipping mutations, or RET fusions, which need to be identified using next-generation sequencing (NGS).11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16

Improving outcomes for patients with NSCLC by encouraging genomic-guided targeted therapy, and through timely delivery of effective and affordable genetic testing, should be government priorities, including in the People’s Republic of China.17, 18, 19, 20 In 2010, the first EGFR mutation testing in vitro diagnostic (IVD) devices were approved by the China Food and Drug Administration (CFDA).21 In the past decade, particularly since 2014, a series of measures have been taken to promote the development of IVD and strengthen medical innovations, influencing the rapid growth of approved IVD products and promoting genetic sequencing of patients with NSCLC in hospitals.22

Data on the types of molecular testing used in the People’s Republic of China, and how their use has changed over time, are scarce. Importantly, the national authoritative database for IVD products, the National Medical Products Administration (NMPA, former name of the CFDA) Medical Devices Unique Identification Database, launched in 2019, has made analysis of longitudinal data possible.23 Therefore, we did a national investigation including 49 hospitals to analyze trends over time in routine clinical testing of NSCLC in mainland People’s Republic of China from 2010 to 2019. We aimed to provide insight on the effectiveness of genetic sequencing and identify specific strategies to implement molecular testing for policy makers.

Materials and Methods

Sampling Method

We conducted a stratified random sampling survey for the molecular testing of lung cancer in hospitals in the mainland People’s Republic of China. First, the country was divided into the following seven geographic regions: east, north, south, central, northeast, northwest, and southwest. To have a representative sample of the People’s Republic of China, we determined the sample size of hospitals in each geographic region weighted by numbers of lung cancer cases identified by the “China Cancer Registry Annual report.” We present the distribution of the population and lung cancer cases by geographic region in cancer registration areas of the People’s Republic of China in 2015 in Supplementary Table 1.

Questionnaire Survey

We conducted a questionnaire survey of the staff who conducted molecular testing for patients with lung cancer in the Department of Pathology or the Central Laboratory from the member hospitals of the Molecular Pathology Collaboration Group of Chinese Anti-Cancer Association (CACA) across the seven geographic regions. A total of 76 member hospitals were investigated, and 49 (64.5%, 49 of 76) member hospitals returned the questionnaire. The distribution of the questionnaire hospitals was tabulated in Supplementary Table 2.

We collected information on the molecular testing of lung cancer cases from 2010 to 2019 in the responded hospitals. Specifically, we collected detailed information on the initial year that each type of mutation testing was used in the hospital, the histologic subtype of lung cancer cases, sample type, the cost, mutation rate, and the brand name of the testing kit. We selected December 31, 2019, as the administrative end date of the survey that traced back to the launched year of the molecular testing in each hospital.

Quality control was conducted by the data management center in the National Cancer Center for the logic, effectiveness, and complement check of the survey data and the analysis of the data set.

The study protocol was approved by the Institute Review Board of the Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Beijing, People’s Republic of China. The methods were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines. Each participant signed an Institutional Review Board–approved informed consent in accordance with the current guidelines.

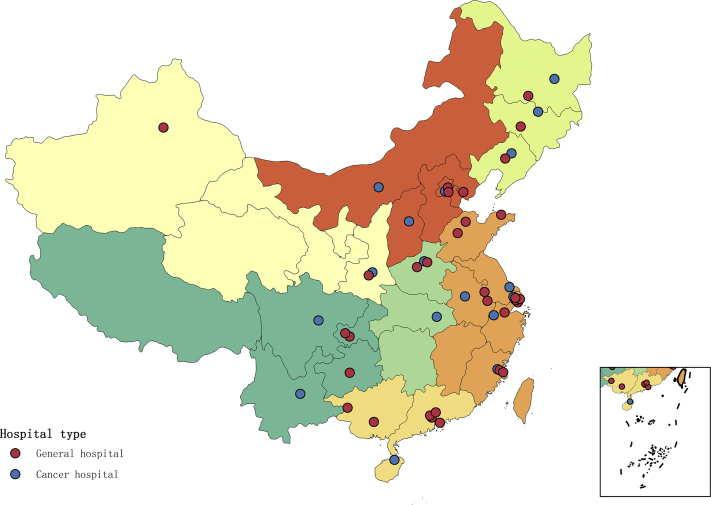

Statistical Analysis

We tabulated the number distribution of the selected hospitals in Supplementary Table 1. The location of the selected hospitals was visualized using ArcGIS. We summarized the launch years for the different molecular tests and the annual and total number of lung cancer cases which had molecular sequencing testing. We also calculated the median cost and geometric mean of the mutation rate for each molecular test. Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). All p values are two-sided, and p values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Geographic Distribution and Changes Over Time of Molecular Testing in NSCLC

We analyzed molecular testing of 49 hospitals sampled from seven geographic regions of the People’s Republic of China weighted by numbers of lung cancer cases. The largest numbers of leading molecular testing units were located in east People’s Republic of China (17 of 49, 34.7%), followed by north (7 of 49, 14.3%), and south (7 of 49, 14.3%) (Supplementary Table 3). In east People’s Republic of China, 17 hospitals conducted molecular testing and are the largest subareas in the People’s Republic of China, which is more than five times compared with that of northwest People’s Republic of China. The geographic distribution of the selected hospitals is found in Figure 1. A total of 226,227 NSCLC specimens were tested from 2010 to 2019 in these 49 hospitals. The annual number of initiated molecular tests increased over time (p < 0.0001), with an average annual growth rate of 31.8%. A notable increase in the number of molecular tests occurred during 2014 and 2016, with more than 70,000 cases tested, corresponding to an average increase of 50% in these years (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Geographic distribution of the 49 surveyed hospitals in mainland People’s Republic of China. The red dots represent the general hospital and the blue dots represent the cancer hospital.

Table 1.

Geographic Distribution of Molecular Testing of NSCLC in Selected Hospitals During 2010 to 2019 in People’s Republic of China

| Geographic Region | Cases/Year |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

| Total | N = 1372 | N = 2177 | N = 5034 | N = 9414 | N = 15,621 | N = 22,718 | N = 30,719 | N = 39,251 | N = 46,514 | N = 53,407 |

| North People’s Republic of China | 377 | 528 | 1111 | 2096 | 2988 | 5139 | 6884 | 8453 | 10,039 | 11,821 |

| Northeast | — | — | 133 | 649 | 1132 | 1334 | 2931 | 4465 | 4822 | 4655 |

| East People’s Republic of China | 336 | 425 | 1253 | 2552 | 4773 | 7764 | 10,033 | 12,200 | 15,966 | 19,492 |

| Central People’s Republic of China | 659 | 1022 | 1273 | 1830 | 3040 | 4180 | 5237 | 6921 | 9354 | 9723 |

| South People’s Republic of China | — | — | 678 | 1254 | 1510 | 1502 | 2101 | 3297 | 2717 | 2430 |

| Southwest | — | 124 | 265 | 672 | 1431 | 1932 | 2506 | 2895 | 2693 | 4235 |

| Northwest | — | 78 | 321 | 361 | 747 | 867 | 1027 | 1020 | 923 | 1051 |

Time Trends of Molecular Testing and IVD Approval

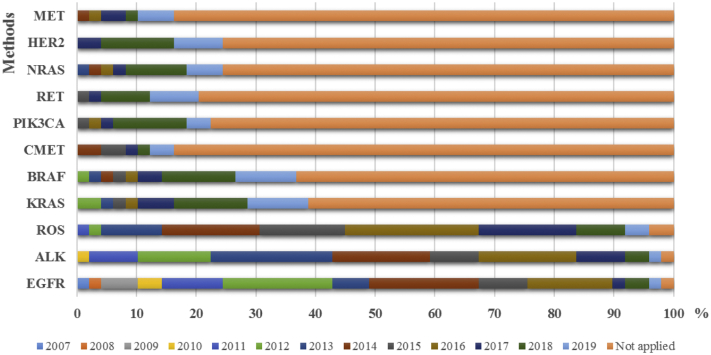

For the molecular diagnosis of specific lung cancer subtypes, EGFR mutation testing was first conducted in year 2007, followed by ALK translocation testing in 2010 and ROS1 in 2011. For other rare genetic variations in NSCLC, BRAF mutation testing was first launched in 2012, MET exon 14 skipping mutation in 2014, HER2 exon 20 mutations in 2017, and RET translocation in 2015. The proportion of hospitals conducting molecular testing gradually increased from 2012 to 2016, with nine hospitals (18.3%) initiating EGFR testing in 2012 and 44 total hospitals (89.8%) with EGFR testing available by 2016 (Fig. 2). For ALK translocation detection, 10 hospitals (20.4%) started in 2013 and a total of 41 hospitals (83.7%) conducted this testing by 2016. The proportion of hospitals testing for ROS1 translocation also gradually increased from 2014 to 2017, with eight hospitals (16.3%) starting in 2014 and a total of 41 (83.7%) by 2017. For other rare genetic variations in NSCLC, the time of molecular testing was initiated from 2014 and flourished in 2018; however, more than half of the hospitals still do not perform NGS.

Figure 2.

The proportion of launched time of molecular testing in mainland People’s Republic of China from 2007 to 2019.

We further explored the annual release of NMPA-approved IVD devices and observed an average annual growth rate of 59% (Fig. 3). A surge in IVD devices was identified beginning in 2014, with 21 newly added IVD devices from 2014 to 2016, representing half of all approved devices. There was also a high correlation between time trends for molecular testing and NMPA approval. The approved IVD devices during 2014 to 2016 accounted for the largest proportion (21/50%), with the equivalent largest EGFR (40.8%), ALK (40.8%), and ROS1 (53.1%) testing launched time, respectively. After the four NGS devices approved by the NMPA in 2018, there was an increase in molecular testing of rare variations of NSCLC.

Figure 3.

Trends in molecular testing of NSCLC and timeline of IVD devices approved by NMPA from 2010 to 2019. FFPE, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded; IVD, in vitro diagnostic; NMPA, National Medical Products Administration.

Time Trends for EGFR Mutation Testing

Temporal trends in EGFR mutation testing were calculated from 2010 to 2019. The annual number of EGFR mutation tests increased over time (p < 0.0001), with an average annual growth rate of 42.3% (Table 2). Among them, 188,249 formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumor tissues were tested with quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) methods, whereas 23,761 specimens with NGS methods. The proportion of EGFR mutation tests using qRT-PCR gradually increased in 2012 to 2017, with a smooth growth tendency after year 2017. The proportion of EGFR mutation testing using NGS sharply increased in 2015 to 2019, with an annual growth rate of 245%. A total of 3780 and 6640 circulating free tumor DNA from plasma samples were conducted with EGFR mutation testing using NGS and superamplification refractory mutation system PCR methods, respectively, with a percentage of 4.2% in all testing specimens.

Table 2.

Trends in Molecular Testing of NSCLC in Selected Hospitals During 2010 to 2019 in Mainland People’s Republic of China

| Driver Gene | Sample Type | Methods | 2010 | 2011 | No. and Proportion of Molecular Testing of the Total NSCLC Cases, by Year |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |||||

| Total cases | N = 1372 | N = 2177 | N = 5034 | N = 9414 | N = 15,621 | N = 22,718 | N = 30,719 | N = 39,251 | N = 46,514 | N = 53,407 | ||

| EGFR | FFPE | qRT-PCR | 659 (48.0) | 1461 (67.1) | 4582 (91) | 8565 (90.9) | 14,490 (92.7) | 21,280 (93.6) | 28,991 (94.4) | 37,131 (94.6) | 36,292 (78.0) | 36,918 (69.1) |

| NGS | — | — | — | — | — | 132 (0.6) | 754 (2.5) | 2870 (7.3) | 8222 (17.7) | 11,783 (22.1) | ||

| Sanger sequencing | 713 (51.9) | 672 (30.8) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| EGFR | Blood | Super-ARMS | — | — | — | — | 46 (0.3) | 282 (1.2) | 836 (2.7) | 1276 (3.3) | 1770 (3.8) | 2430 (4.5) |

| NGS | — | — | — | — | — | — | 47 (0.2) | 683 (1.7) | 1260 (2.7) | 1790 (3.4) | ||

| ALK | FFPE | qRT-PCR | — | — | 23 (0.5) | 317 (3.4) | 787 (5.0) | 1845 (8.1) | 2996 (9.8) | 4999 (12.7) | 9973 (21.4) | 16,384 (30.7) |

| FISH | 88 (6.4) | 336 (15.4) | 537 (10.7) | 1879 (20.0) | 2932 (18.8) | 4796 (21.1) | 5095 (17.6) | 6502 (16.6) | 6874 (14.8) | 5726 (10.7) | ||

| Vetana-D5F3 IHC | — | — | — | 502 (5.3) | 4110 (26.3) | 4574 (20.1) | 8313 (27.1) | 12,063 (30.7) | 7525 (16.2) | 10,753 (20.1) | ||

| NGS | — | — | — | — | — | 132 (0.6) | 759 (2.5) | 2610 (6.6) | 8145 (17.5) | 10,346 (19.4) | ||

| ROS1 | FFPE | qRT-PCR | — | — | 2 (0.0) | 140 (1.5) | 177 (1.1) | 502 (2.2) | 1330 (4.3) | 4562 (11.6) | 9581 (20.6) | 15,847 (29.7) |

| FISH | — | — | — | — | 226 (1.4) | 1394 (6.1) | 1792 (5.8) | 3890 (9.9) | 4644 (10.0) | 4311 (8.1) | ||

| NGS | — | — | — | — | — | 191 (0.8) | 754 (2.5) | 2605 (6.6) | 7528 (16.2) | 10,339 (19.4) | ||

Note: Values are given in n (%).

FFPE, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; IHC, immunohistochemistry; NGS, next-generation sequencing; qRT-PCR, quantitative reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction; Super-AMRS, superamplification-amplification refractory mutation system.

We further investigated the rate of activating mutations using qRT-PCR, including EGFR exon 19 deletion and exon 21 L858R mutations, and noticed an average mutation rate of 42.4% from 2012 to 2019 (Table 3). In comparison, the positive rate of activating mutations using NGS was 41.0% from 2015 to 2019. Regarding circulating tumor DNA detection, the positive rate of T790M mutation was 21.7% and 23.2% using NGS and superamplification refractory mutation system PCR methods, respectively. Quantitative real-time PCR and NGS panel tests cost in the range of $460 to $1240, and the prices remained stable from 2012 to now.

Table 3.

Changes in Positive Rates of NSCLC in Selected Hospitals During 2010 to 2019 in Mainland People’s Republic of China

| Driver Gene | Sample Type | Methods | 2010 | 2011 | Positive Rates of Driver Genes by Year |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |||||

| EGFR | FFPE | qPCR | 39.0 | 39.1 | 38.7 | 40.4 | 40.6 | 43.5 | 44.5 | 43.7 | 43.3 | 44.1 |

| NGS | — | — | — | 36.3 | 39.7 | 42.7 | 44.6 | 41.9 | ||||

| Sanger sequencing | 34.2 | 31.9 | ||||||||||

| EGFR | Blood | Super-ARMS | — | — | — | — | 22.9 | 23.8 | 22.4 | 23.5 | ||

| NGS | — | — | — | — | — | 21.7 | 22.0 | 21.4 | ||||

| ALK | FFPE | qRT-PCR | 5.9 | 6.2 | 6.6 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 6.9 | 6.1 | 6.1 | ||

| FISH | 6.8 | 7.2 | 6.6 | 10.5 | 11.9 | 13.5 | 12.2 | 13.7 | 10.1 | 13.2 | ||

| Vetana-D5F3 IHC | — | 7.2 | 6.6 | 6.4 | 6.4 | 7.0 | 7.2 | 6.9 | ||||

| NGS | — | — | — | 3.1 | 3.8 | 4.1 | 5.5 | 5.1 | ||||

| ROS1 | FFPE | qRT-PCR | — | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 1.8 | ||

| FISH | — | — | 4.2 | 3.5 | 4.3 | 4.2 | 4.6 | 4.1 | ||||

| NGS | — | — | — | — | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.2 | ||||

Note: Values are given in %.

FFPE, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; IHC, immunohistochemistry; NGS, next-generation sequencing; qPCR, quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction; qRT-PCR, quantitative reverse-transcript polymerase chain reaction; Super-AMRS, superamplification refractory mutation system.

Time Trends of Fusion Gene Testing

Ventana-D5F3 immunohistochemistry (IHC), fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), RT-PCR, and NGS can all be used to detect ALK gene fusions. A total of 37,324 specimens were tested with qRT-PCR, 35,341 specimens with FISH, 47,840 specimens with IHC, and 21,992 specimens with NGS (Table 2). Among these approved methods, the annual number of RT-PCR and IHC detection specimens increased over time (p < 0.0001), with an average annual growth rate of 97% and 144%, respectively. NGS was conducted from 2015, with a growth rate of 240% in the past 4 years. The use of FISH gradually increased from 2012 to 2018, but with a decrease in 2019 of 35.5%. We further investigated the positive rate of ALK gene fusions using the different detection methods and calculated an average fusion rate of 6.59% for RT-PCR, 6.82% for IHC, 11.46% for FISH, and 4.33% for NGS (Table 3). The costs for qRT-PCR, FISH, and IHC were $400, $327, and $60, respectively.

qRT-PCR and NGS are used to detect ROS1 gene fusions, and 32,141 specimens were tested with qRT-PCR and 21,417 specimens with NGS (Table 2). qRT-PCR for ROS1 was first approved in the People’s Republic of China, and the proportion of ROS1 testing with qRT-PCR gradually increased from 2012 to 2019, with an average annual growth rate of 132%. NGS has been conducted since 2015, with growth rate of 192% in the past 4 years. We further investigated the positive rate of ROS1 fusion using these two methods and observed an average fusion rate of 1.62% for RT-PCR and 1.38% for NGS (Table 3).

Discussion

This stratified random sampling survey provided substantial information on the landscape of molecular testing of lung cancer in mainland People’s Republic of China. Important increases in the numbers of molecular tests conducted, approved IVD products, recommended genetic variants to test, and molecular testing hospitals illustrate the progress made in the decade 2010 to 2019. These growth patterns are also evidence of the evolving effectiveness of the IVD industry in the People’s Republic of China and can act as an important guide for directing future molecular testing and development. Importantly, the relatively low number of rare variants currently tested and the uneven geographic distribution of leading molecular testing hospitals can provide potential targets for improvement in future polices and strategies.

From 2010 to 2019, the number of molecular tests conducted in mainland People’s Republic of China revealed remarkable growth, with an average annual growth rate of 31.8%. This suggests that Chinese hospitals are able to provide precision therapy for lung cancer. This growth in the number of molecular tests is also likely to be associated with the identification of new driver genes and also the important efforts supported by the Chinese government. Since 2010, the NMPA (formerly the CFDA) has regularly approved a list of in vitro companion diagnostic devices for use in multiple targeted drugs in NSCLC (Table 4).24 To cultivate a more innovation-friendly molecular testing research and development environment in mainland People’s Republic of China, the NMPA has implemented new priority regulations for IVD reagent registration since 2014, which emphasized approval based on clinical value.22 In addition, the requirement for consistent quality, efficacy, and risk evaluation for oncology testing panels has been put forward by the NMPA since 2017. Increases were found in the number of molecular tests conducted, both EGFR mutation testing and ALK/ROS1 fusion detection since 2014. The first EGFR mutation testing IVD companion device was approved in 2010, which is based on quantitative real-time PCR.25 Since then, a series of 29 domestic EGFR mutation testing devices have been made available, including qRT-PCR, NGS oncopanel, Sanger sequencing, fluorescent PCR-capillary electrophoresis, and denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography. This increased competition resulted in a large discount in patient expenditure (currently $460 for EGFR mutation testing in mainland People’s Republic of China) compared with that for the Food and Drug Administration–approved EGFR testing device, and the price is only approximately one-third of that in the United States.

Table 4.

Timeline of Milestones in Molecular Testing of NSCLC in Mainland People’s Republic of China

| Year | Key Milestones in Release of Guidelines or Expert Consensus, NMPA Approval of IVD and CDx Devices in Molecular Testing of Lung Cancer in Mainland People’s Republic of China |

|---|---|

| 2010 | First EGFR mutation testing in vitro diagnostics device approval by CFDA |

| 2011 | Consensus on epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutation detection in NSCLC |

| 2013 | The diagnosis and treatment guideline of Chinese patients with EGFR mutation and ALK fusion gene-positive NSCLC (2013 version) |

| 2014 | The diagnosis and treatment guideline of Chinese patients with EGFR gene active mutation and ALK fusion gene-positive NSCLC (2014 version) |

| 2015 | The guideline for diagnosis and treatment of Chinese patients with sensitizing EGFR mutation or ALK fusion gene-positive NSCLC (2015 version) |

| 2015 | Guideline of construction of molecular pathological laboratory |

| 2015 | Screen of ALK-positive NSCLC by routine immunohistochemistry: an expert consensus |

| 2015 | Consensus on epidermal growth factor receptor cell-free DNA mutation detection in NSCLC |

| 2016 | Updated consensus on epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutation detection in NSCLC |

| 2017 | Expert consensus on next-generation gene sequencing detection in clinical molecular pathological laboratory |

| 2018 | Expert consensus on diagnosis of ROS1 gene fusion-positive NSCLC |

| 2018 | Four NGS in vitro diagnostics devices for lung cancer mutation detection approval by NMPA |

| 2019 | Expert consensus on clinical practice of ALK fusion detection in NSCLC in China |

CDx, companion diagnostic; CFDA, China Food and Drug Administration; IVD, in vitro diagnostic; NGS, next-generation sequencing; NMPA, National Medical Products Administration.

In addition to government-provided guidance, experts from professional societies including the CACA, Chinese Medical Association, and Chinese Society of Clinical Oncology have formulated several guidelines and recommendations for molecular testing of NSCLC in mainland People’s Republic of China in the past decade. The first public expert recommendations for EGFR mutation testing of NSCLC were presented in 2011.26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33 Since then, a total of 10 guidelines and expert recommendations on EGFR circulating tumor DNA mutation testing, ALK/ROS1 fusion detection, expert consensus on NGS have been released, and these guide molecular testing and targeted therapy in mainland People’s Republic of China. These consensus recommendations have standardized molecular testing and promoted the development of targeted therapies for lung cancer in mainland People’s Republic of China. To our knowledge, these guidelines are concordant with those of the College of American Pathologists/International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer/Association for Molecular Pathology with slight modifications according to Chinese molecular testing practices and are updated at an accelerated pace to maintain compatibility with partners in the United States.34,35

On the basis of clinical practice for molecular testing in mainland People’s Republic of China, great efforts have been made to maximize the appropriate practice strategies and minimize the inappropriate practice variations. For example, several new ALK companion diagnostic devices have been developed and applied in clinical practice.36,37 To maximize the benefit for patients, accurate testing results can be obtained by first selecting the appropriate testing method and then formulating, optimizing, and complying with the standardized testing process in accordance with the testing population and specimen type. When optimizing ALK testing strategies, it is highly recommended that Ventana-D5F3 IHC should be performed first, as it has high sensitivity and specificity, and requires a relatively small tissue sample.33 Our results identified an average fusion rate of 6.82% for Ventana-D5F3 IHC with a low patient expenditure compared with FISH. The higher positive rate of ALK FISH across four detecting methods was largely because of the selection of FISH methods to verify the results of IHC or qRT-PCR. With molecular testing available as the standard of care for most patients with lung cancer, the affordability of testing expenses should be a critical area of focus moving forward.

In addition to single-gene testing, current guidelines recommend testing for multiple genetic variations, with testing of ROS1, HER2, MET, BRAF, KRAS, NTRK, and RET as a possibility in laboratories using NGS panels.35 Increased use of these NGS panels can aid physicians in selecting therapies, especially with the rapid development of additional targeted agents. NGS panels have priority for evaluation and approval by the NMPA. As a result, in 2018, four Chinese innovative NGS panel devices were approved by the NMPA in mainland People's Republic of China, all of which were tested for lung cancer (Burning Rock Dx, Novogene, Geneseeq, and AmoyDx) and one for both lung cancer and colorectal cancer (AmoyDx). This action stimulated the market and promoted molecular testing in clinical practice, which was revealed by a surge in molecular testing of rare variations of NSCLC since 2018. By the end of 2019, 11 molecular pathologic centers had conducted NGS testing of lung cancer panels directly in hospitals, accounting for 22.4% of all 49 surveyed hospitals. Furthermore, the increased use and availability of NGS panels and liquid biopsy are primed to enhance the need for up-to-date guidelines and recommendations.38 In some clinical settings in which tissue biopsy material is unavailable or insufficient and tissue rebiopsy is not feasible, a circulating free DNA assay for an activating EGFR mutation may be conducted as an alternative molecular diagnostic procedure. Circulating free DNA analysis for EGFR T790M has intermediate sensitivity and high specificity, and using our data, we calculated an average of 20% positive rate of T790M mutation in patients with tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistance.

Our study further revealed a markedly uneven geographic distribution of molecular testing centers across mainland People’s Republic of China, with the largest numbers of leading molecular testing units in eastern People’s Republic of China and the lowest numbers in western areas. Therefore, we believe that, instead of uneven population or patient distribution, this geographic disparity is the direct manifestation of the uneven distribution of medical resources for clinical care across the People’s Republic of China, which needs to be addressed by the government. It is also likely to be due to the government’s demand for Chinese associations of molecular testing to fully play the leading role of major hospitals, with resource priority given to the exemplary role of top leaders. Therefore, the Chinese Medical Association and CACA developed educational and training initiatives aimed to improve technical knowledge and awareness of guidelines with increased education in most areas of mainland People’s Republic of China.39 Furthermore, initiatives such as awareness campaigns and educational efforts (multimodal methods of delivery, hands-on training, online interactive content, conferences, etc.) are promoting molecular testing for all patients with lung cancer in mainland People’s Republic of China.

On the basis of a stratified random sampling survey of molecular testing in mainland People’s Republic of China, our study elucidated the overall landscape of molecular testing of lung cancer, and its contribution to clinical practice for the decade 2010 to 2019. However, our study has some limitations. Although this is the largest and most comprehensive evaluation of molecular testing in lung cancer on the basis of a random sampling survey in mainland People’s Republic of China, regional oversampling and undersampling suggest that our estimates may not be fully representative of the entire country. We have worked to address this limitation by evaluating results by region, to understand how the regional patterns might influence the overall findings. Substantial representation from seven different geographic regions may also improve our generalizability. In addition, all results presented are based on self-reported perceptions, which may not accurately represent the true state of molecular testing. However, the data were provided by front-line practitioners who are fully informed on molecular testing in lung cancer. So, we believe that this study is useful for identifying and understanding the general landscape of molecular testing of lung cancer in mainland People’s Republic of China. Third, when we evaluated the rates of molecular testing, the question asked on patients with lung cancer in general, not specifically for patients with advanced stage adenocarcinoma. The stage and histologic distribution may influence molecular testing rates, which limited our ability to quantify the specific proportion of guideline recommended testing on the basis of pathologic subtypes.

In conclusion, in the decade 2010 to 2019, progress in the molecular testing of lung cancer was achieved in mainland People’s Republic of China. The Chinese NMPA regulation of innovative medical devices seems to have effectively addressed the huge unmet medical needs of patients with lung cancer, with effective IVD and companion diagnostic devices now available for molecular testing. Furthermore, the departments of Center for Medical Devices Evaluation and Center for Drug Evaluation of NMPA are now striving to establish a collaborative review process with companion diagnostic reagents and related antineoplastic drugs, which emphasizes diagnostic reagents approval on the basis of clinical value. Given the large patient pool, the rising capability of clinical development, and substantial support from the government, we believe that the People’s Republic of China has become an advanced location for molecular testing research and development and seems prepared to contribute to the global clinical practices. The landscape of molecular testing is complex and rapidly evolving, highlighting the need for more efforts to expert recommendations and guidelines. Continuous education and training on molecular testing in lung cancer should be intensified on national levels to ensure that patients receive optimal treatment.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Project (2017YFC1311005), the Beijing Hope Run Special Fund of Cancer Foundation of the People’s Republic of China (LC2019L04), Beijing Municipal Health Commission (2018-TG-58), and Beijing Nova Program of Science and Technology (Z191100001119095). The authors thank all study participants of the 49 hospitals from the members of the Molecular Pathology Collaboration Group of Tumor Pathology Committee of Chinese Anti-Cancer Association, including Lei Guo, Tian Qiu, Weihua Li, and Yan Li from the National Cancer Center, Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College; Nanying Che from Beijing Chest Hospital, Capital Medical University; Xuefeng Bai from Baotou Cancer Hospital; Yanfeng Xi from Shanxi Cancer Hospital; Yanping Hu from Luhe Hospital, Capital Medical University; Liping Liu from Beijing Shunyi Hospital; Xuemei Li from TangShan Gongren Hospital; Shujun Zhang from the Fourth Hospital, Harbin Medical University; Hongxue Meng from Cancer Hospital, Harbin Medical University; Xiumei Duan from the First Bethune Hospital of Jilin University; Yan Wu from Jilin Cancer Hospital; Lian He from Liaoning Cancer Hospital & Institute; Nan Liu from the First Affiliated Hospital, People’s Republic of China Medical University; Jie He from Anhui Province Cancer Hospital; Hong Li from Binzhou Medical University Hospital; Zhihui Yang from General Hospital of Eastern Theater Command; Jie Lin from Fujian Provincial Hospital; Yi Shi from Fujian Cancer Hospital; Xiaoyan Li and Meihong Yao from Fujian Medical University Union Hospital; Qianming Bai from Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center; Ling Xie from Jiangsu Province Hospital of Chinese Medicine; Xinghua Zhu from Nantong Tumor Hospital; Aiyan Xing from Qilu Hospital of Shandong University; Zebing Liu from Renji Hospital, Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine; Lei Dong from Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine; Wentao Huang from Shanghai Sixth People’s Hospital, Shanghai Jiaotong University; Jie Huang from Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University; Guohua Yu from Yantai Yuhuangding Hospital; Xiaotong Hu from Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine; Dan Su from Cancer Hospital of the University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Zhejiang Cancer Hospital; Bing Wei from Henan Cancer Hospital; Fang Guo from Hubei Cancer Hospital; Ziguang Xu from Henan Provincial People’s Hospital; Guozhong Jiang from the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University; Qian Cui from Guangdong People’s Hospital; Jia Li from the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University; Xianhua Xu from Hainan Cancer Hospital; Juan Jiao from the Second People’s Hospital of Shenzhen; Xinhui Fu from the Sixth Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University; Nengtai Ouyang and Xiaojuan Li from Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University; Xiaoying Zhu from Affiliated Hospital of Youjiang Medical University for Nationalities; Yanjie Liu from the Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University; Qiushi Wang from Daping Hospital, Army Medical University; Qiong Liao and Zhuo Zuo from Sichuan Cancer Hospital and Institute; Tao Luo from the First Hospital Affiliated to Army Medical University; Chenggang Yang from Yunnan Cancer Hospital; Xiaoming Wang from Shanxi Provincial Cancer Hospital; Xi Liu from First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University; and Wenli Cui from First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University. This manuscript was reviewed and commented on by all authors. The corresponding author had full access to the study data and takes full responsibility for the final decision to submit the manuscript.

Footnotes

Drs. Li and Lyu contributed equally to this work.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Cite this article as: Li W, Lyu Y, Wang S, et al.Trends in molecular testing of lung cancer in Mainland People’s Republic of China over the decade 2010 to 2019. JTO Clin Res Rep. 2021;2:100163.

Note: To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of the JTO Clinical and Research Reports at www.jtocrr.org/ and at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtocrr.2021.100163.

Contributor Information

Jianming Ying, Email: jmying@cicams.ac.cn.

Experts from the Molecular Pathology Collaboration Group of Tumor Pathology Committee of Chinese Anti-Cancer Association:

Lei Guo, Tian Qiu, Weihua Li, Yan Li, Nanying Che, Xuefeng Bai, Yanfeng Xi, Yanping Hu, Liping Liu, Xuemei Li, Shujun Zhang, Hongxue Meng, Xiumei Duan, Yan Wu, Lian He, Nan Liu, Jie He, Hong Li, Zhihui Yang, Jie Lin, Yi Shi, Xiaoyan Li, Meihong Yao, Qianming Bai, Ling Xie, Xinghua Zhu, Aiyan Xing, Zebing Liu, Lei Dong, Wentao Huang, Jie Huang, Guohua Yu, Xiaotong Hu, Dan Su, Bing Wei, Fang Guo, Ziguang Xu, Guozhong Jiang, Qian Cui, Jia Li, Xianhua Xu, Juan Jiao, Xinhui Fu, Nengtai Ouyang, Xiaojuan Li, Xiaoying Zhu, Yanjie Liu, Qiushi Wang, Qiong Liao, Zhuo Zuo, Tao Luo, Chenggang Yang, Xiaoming Wang, Xi Liu, and Wenli Cui

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Zhang S.W., Sun K.X., Zheng R.S. Cancer incidence and mortality in China. Journal of the National Cancer Center. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jncc.2020.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen W., Zheng R., Baade P.D. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:115–132. doi: 10.3322/caac.21338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramalingam S.S., Vansteenkiste J., Planchard D. Overall survival with osimertinib in untreated, EGFR-mutated advanced NSCLC. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:41–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1913662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Solomon B.J., Kim D.W., Wu Y.L. Final overall survival analysis from a study comparing first-line crizotinib versus chemotherapy in ALK-mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:2251–2258. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.77.4794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaw A.T., Riely G.J., Bang Y.J. Crizotinib in ROS1-rearranged advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): updated results, including overall survival, from PROFILE 1001. Ann Oncol. 2019;30:1121–1126. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao Y., Liu J., Cai X. Efficacy and safety of first line treatments for patients with advanced epidermal growth factor receptor mutated, non-small cell lung cancer: systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2019;367:l5460. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l5460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pacheco J.M., Gao D., Smith D. Natural history and factors associated with overall survival in stage IV ALK-rearranged non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14:691–700. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hida T., Nokihara H., Kondo M. Alectinib versus crizotinib in patients with ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (J-ALEX): an open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;390:29–39. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30565-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou C., Kim S.W., Reungwetwattana T. Alectinib versus crizotinib in untreated Asian patients with anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (ALESIA): a randomised phase 3 study. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7:437–446. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30053-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shaw A.T., Solomon B.J., Chiari R. Lorlatinib in advanced ROS1-positive non-small-cell lung cancer: a multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 1–2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:1691–1701. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30655-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Planchard D., Smit E.F., Groen H.J.M. Dabrafenib plus trametinib in patients with previously untreated BRAF(V600E)-mutant metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: an open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:1307–1316. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30679-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baraibar I., Mezquita L., Gil-Bazo I., Planchard D. Novel drugs targeting EGFR and HER2 exon 20 mutations in metastatic NSCLC. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2020;148:102906. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2020.102906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Molina-Arcas M., Moore C., Rana S. Development of combination therapies to maximize the impact of KRAS-G12C inhibitors in lung cancer. Sci Transl Med. 2019;11 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaw7999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujino T., Kobayashi Y., Suda K. Sensitivity and resistance of MET exon 14 mutations in lung cancer to eight MET tyrosine kinase inhibitors in vitro. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14:1753–1765. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Subbiah V., Yang D., Velcheti V., Drilon A., Meric-Bernstam F. State-of-the-art strategies for targeting RET-dependent cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:1209–1221. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trédan O., Wang Q., Pissaloux D. Molecular screening program to select molecular-based recommended therapies for metastatic cancer patients: analysis from the ProfiLER trial. Ann Oncol. 2019;30:757–765. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.AACR Project GENIE: powering precision medicine through an International Consortium. Cancer Discov. 2017;7:818–831. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-0151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Z., Cheng Y., An T. Detection of EGFR mutations in plasma circulating tumour DNA as a selection criterion for first-line gefitinib treatment in patients with advanced lung adenocarcinoma (BENEFIT): a phase 2, single-arm, multicentre clinical trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6:681–690. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30264-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smeltzer M.P., Wynes M.W., Lantuejoul S. The International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer global survey on molecular testing in lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2020;15:1434–1448. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gao S., Li N., Wang S. Lung cancer in People’s Republic of China. J Thorac Oncol. 2020;15:1567–1576. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu C., Huang J., An J., Deng G. Resolved problems of EGFR mutation detection reagent registration application. Zhongguo Yi Liao Qi Xie Za Zhi. 2017;41:289–291. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1671-7104.2017.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu W., Shi X., Lu Z., Wang L., Zhang K., Zhang X. Review and approval of medical devices in China: changes and reform. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2018;106:2093–2100. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.34031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu H., Zheng J., Lan Y., Wang H., Yu X. Discussion on information-based management of medical device standard. Zhongguo Yi Liao Qi Xie Za Zhi. 2019;43:300–302. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1671-7104.2019.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Min Y., Lan W., Liu B. Discussion on administrative innovation of medical device in China and U.S. Zhongguo Yi Liao Qi Xie Za Zhi. 2018;42:206–209. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1671-7104.2018.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang L.S., Zhang Y., Lu X.J. Detection of epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutations in non-small cell lung cancer using bi-loop probe specific primer quantitative PCR. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2011;40:667–670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chinese Association of Oncologists Chinese Society for Clinical Cancer Chemotherapy The diagnosis and treatment guideline of Chinese patients with EGFR mutation and ALK fusion gene-positive non-small cell lung cancer (2013 version) Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2013;35:478–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chinese Association of Oncologists; Chinese Society for Clinical Cancer Chemotherapy; Chinese Association of Oncologists, et al. The diagnosis and treatment guideline of Chinese patients with EGFR gene active mutation and ALK fusion gene-positive non-small cell lung cancer (2014 version) Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2014;36:555–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chinese Society of Pathology, Chinese Pathologist Association, Committee of Oncopathology of Chinese Anticancer Association, et al. Guideline of construction of molecular pathology laboratory. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2015;44:369–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chinese Association of Oncologists, Chinese Society for Clinical Cancer Chemotherapy; Chinese Association of Oncologists Chinese Society for Clinical Cancer Chemotherapy The guideline for diagnosis and treatment of Chinese patients with sensitizing EGFR mutation or ALK fusion gene-positive non-small cell lung cancer (2015version) Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2015;37:796–799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Consensus Group for screen of ALK-positive non-small cell lung cancer by routine immunohistochemistry Screen of ALK-positive non-small cell lung cancer by routine immunohistochemistry: an expert consensus. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2015;44:476–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chinese Expert Group for Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Gene Mutation Detection in Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinoma Consensus on epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutation detection in non-small cell lung carcinoma. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2016;45:217–220. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0529-5807.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lung Cancer Professional Group of Chinses Anti-Cancer Association Pathology Specialized Committee Expert consensus on diagnosis of Ros1 gene fusion-positive non-small cell lung cancer. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2018;47:248–251. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0529-5807.2018.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Experts from the RATICAL study (ALK testing in Chinese advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients: a national-wide multicenter prospective real world data study), Molecular Pathology Committee of Chinese Society of Pathology Expert consensus on clinical practice of ALK fusion detection in non-small cell lung cancer in China. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2019;48:913–920. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0529-5807.2019.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lindeman N.I., Cagle P.T., Beasley M.B. Molecular testing guideline for selection of lung cancer patients for EGFR and ALK tyrosine kinase inhibitors: guideline from the College of American Pathologists, International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, and Association for Molecular Pathology. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8:823–859. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318290868f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindeman N.I., Cagle P.T., Aisner D.L. Updated molecular testing guideline for the selection of lung cancer patients for treatment with targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors: guideline from the College of American Pathologists, the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, and the Association for Molecular Pathology. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13:323–358. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2017.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ying J., Guo L., Qiu T. Diagnostic value of a novel fully automated immunochemistry assay for detection of ALK rearrangement in primary lung adenocarcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:2589–2593. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rogers T.M., Russell P.A., Wright G. Comparison of methods in the detection of ALK and ROS1 rearrangements in lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10:611–618. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li B.T., Janku F., Jung B. Ultra-deep next-generation sequencing of plasma cell-free DNA in patients with advanced lung cancers: results from the Actionable Genome Consortium. Ann Oncol. 2019;30:597–603. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang E., Zhu M., Bu H. Consensus of Chinese experts on detection of related drive genes in target therapy of non-small cell lung cancer. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2016;45:73–77. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0529-5807.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.