Abstract

Introduction

We retrospectively evaluated outcomes in patients with programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1)–positive non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) to determine whether baseline (i.e., at study enrollment) brain metastases were associated with the efficacy of pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy.

Methods

We pooled data for patients with previously treated or untreated PD-L1‒positive (tumor proportion score [TPS], ≥1%) advanced or metastatic NSCLC in KEYNOTE-001 (NCT01295827), KEYNOTE-010 (NCT01905657), KEYNOTE-024 (NCT02142738), and KEYNOTE-042 (NCT02220894). Patients received pembrolizumab (2 mg/kg, 10 mg/kg, or 200 mg every 3 wk or 10 mg/kg every 2 wk); chemotherapy was a comparator in all studies except KEYNOTE-001. All studies included patients with previously treated, stable brain metastases.

Results

A total of 3170 patients were included, 293 (9.2%) with and 2877 (90.8%) without baseline brain metastases; median (range) follow-up at data cutoff was 12.9 (0.1‒43.7) months. Pembrolizumab improved overall survival versus chemotherapy in patients with or without baseline brain metastases: benefit was seen in patients with PD-L1 TPS ≥50% (0.67 [95% confidence intervals (CI): 0.44‒1.02] and 0.66 [95% CI: 0.58‒0.76], respectively) and PD-L1 TPS ≥1% (0.83 [95% CI: 0.62‒1.10] and 0.78 [95% CI: 0.71‒0.85], respectively). Progression-free survival was improved, objective response rates were higher, and duration of response was longer with pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy regardless of brain metastasis status. The incidence of treatment-related adverse events with pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy was 66.3% versus 84.4% in patients with brain metastases and 67.2% versus 88.3% in those without.

Conclusions

Pembrolizumab monotherapy improved outcomes and was associated with fewer adverse events than chemotherapy in patients with treatment-naive and previously treated PD-L1‒positive advanced/metastatic NSCLC regardless of the presence of baseline treated, stable brain metastases.

Keywords: Pembrolizumab, Brain metastases, Chemotherapy, Non‒small-cell lung cancer, PD-L1

Introduction

Brain metastases, which occur in approximately one-third of patients with advanced non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) are associated with poorer outcomes compared with other sites of metastasis.1 Despite these findings, patients with advanced NSCLC and active brain metastases are often underrepresented in, or excluded from, clinical trials.2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Recent studies have shown fewer tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and T-cell clones and less programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression in brain metastases than in paired primary lung cancers,7,8 suggesting the potential for differential response to immunotherapy among patients with and without brain metastases. However, recent evidence from patients with NSCLC receiving programmed death 1 (PD-1) or PD-L1 inhibitor monotherapy suggests that the presence of brain metastases was not associated with poorer survival on the basis of multivariate analysis.9

The efficacy of monotherapy with the anti–PD-1 monoclonal antibody pembrolizumab has been reported in patients with advanced NSCLC, including a phase 1 study of previously treated and untreated disease (KEYNOTE-001),10 a phase 2/3 study (KEYNOTE-010) in the second-line or later setting,11 and two phase 3 studies in the first-line setting (KEYNOTE-024 and -042).12,13 In the three randomized studies (KEYNOTE-010, -024, and -042), overall survival (OS) was significantly longer with pembrolizumab than chemotherapy. Each of the four studies permitted enrollment of patients with previously treated brain metastases provided the patients were clinically stable.

We sought to better characterize outcomes in this population of patients with historically poor prognoses. In this pooled analysis, we retrospectively evaluated outcomes in patients with PD-L1–positive NSCLC, with or without known baseline brain metastases, who were treated with pembrolizumab monotherapy in KEYNOTE-001 and either pembrolizumab monotherapy or chemotherapy in KEYNOTE-010, -024, and -042.

Materials and Methods

Patients

Patients from KEYNOTE-001 (NCT01295827),10 KEYNOTE-010 (NCT01905657),11 KEYNOTE-024 (NCT02142738),12 and KEYNOTE-042 (NCT02220894)13 were included in this post hoc pooled analysis. Methods for each study were described previously and are briefly summarized here. The study protocols were approved by institutional review boards or ethics committees at each site. Patients provided written informed consent.

In all studies, eligible patients were at least 18 years of age with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0 or 1, adequate organ function, life expectancy of at least 3 months, a histologically or cytologically confirmed diagnosis of NSCLC, and at least 1 measurable lesion per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1 (RECIST v1.1).14 In KEYNOTE-001, patients had previously treated or untreated locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC and could have had any PD-L1 tumor proportion score (TPS), although, for this pooled analysis, only patients with PD-L1–positive tumors (i.e., PD-L1 TPS ≥1%) were included. In KEYNOTE-010, patients had previously treated advanced NSCLC and PD-L1 TPS ≥1%. Both KEYNOTE-001 and -010 allowed EGFR-mutant or ALK-translocated tumors that had failed tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy. In KEYNOTE-024, patients had treatment-naive advanced NSCLC with no sensitizing EGFR or ALK genomic tumor aberrations and PD-L1 TPS ≥50%. In KEYNOTE-042, patients had treatment-naive advanced NSCLC with no sensitizing EGFR or ALK genomic tumor aberrations and PD-L1 TPS ≥1%. Patients with known active central nervous system (CNS) metastases and/or carcinomatous meningitis were excluded from each study. Patients with previously treated brain metastases were eligible provided they were clinically stable for at least 4 weeks before study entry, showed no evidence of new or enlarging brain metastases, and completed corticosteroid treatment for brain metastases greater than or equal to 3 days (KEYNOTE-010, -024, -042) or at least 7 days (KEYNOTE-001) before study treatment.

Study Design and Treatment

Patients in KEYNOTE-001 received intravenous pembrolizumab 2 mg/kg or 10 mg/kg every 3 weeks or 10 mg/kg every 2 weeks. Patients in KEYNOTE-010 were randomized 1:1:1 to receive intravenous pembrolizumab 2 mg/kg, 10 mg/kg, or docetaxel 75 mg/m2 every 3 weeks for up to 35 cycles; randomization was stratified by ECOG performance status (0 versus 1), region (East Asia versus non–East Asia), and PD-L1 TPS (≥50% versus 1%–49%). Patients in KEYNOTE-024 were randomized 1-to-1 to receive intravenous pembrolizumab 200 mg every 3 weeks for up to 35 cycles or platinum-based chemotherapy for four to six cycles with optional pemetrexed maintenance for nonsquamous histologies; randomization was stratified by histology (squamous versus nonsquamous), ECOG performance status (0 versus 1), and region (East Asia versus non–East Asia). Patients in KEYNOTE-042 were randomized 1-to-1 to receive intravenous pembrolizumab 200 mg every 3 weeks for up to 35 cycles or platinum-based chemotherapy for four to six cycles with optional pemetrexed maintenance for nonsquamous histologies; randomization was stratified by ECOG performance status (0 versus 1), histology (squamous versus nonsquamous), region (East Asia versus non–East Asia), and PD-L1 TPS (≥50% versus 1%–49%).

Assessments

Radiographic imaging with computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for non-CNS assessment was done within 30 days of enrollment (baseline) and every 9 weeks thereafter. For KEYNOTE-042, imaging was performed every 9 weeks for the first 45 weeks and then every 12 weeks thereafter. In all studies, the response was assessed per RECIST v1.1 by blinded, independent central review.14 All patients in KEYNOTE-024 had CNS imaging at screening, including patients with no previous history of brain metastases; in the other studies, patients with previously treated brain metastases had to exhibit no evidence of new or enlarging brain metastases for at least 4 weeks after treatment of the brain metastases. In all studies, regular CNS imaging was not required at subsequent imaging assessments. Adverse events (AEs) were monitored during and for 30 days after treatment and graded per National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.0. Serious AEs were monitored for 90 days after treatment. PD-L1 expression status was determined by a central laboratory in formalin-fixed tumor samples collected at the time of metastatic disease diagnosis. All studies used a 22C3 antibody‒based assay to evaluate PD-L1 TPS.

End points

End points evaluated were OS, progression-free survival (PFS), objective response rate (ORR), duration of response (DOR), and incidence of AEs. OS was defined as the time from randomization (first dose of study treatment in KEYNOTE-001) to death from any cause. PFS was defined as the time from randomization (first dose of study treatment in KEYNOTE-001) to progression, defined by RECIST v1.1, or death from any cause. ORR was defined as the proportion of patients with radiologically confirmed complete or partial responses. DOR, determined for patients with a complete or partial response, was defined as the time from first documented evidence of response until disease progression.

Statistical Analysis

This pooled analysis included individual patient data from patients with PD-L1 TPS ≥1% enrolled in KEYNOTE-001 and all patients from the intent-to-treat populations enrolled in KEYNOTE-010, -024, and -042. One patient in KEYNOTE-010 was excluded from efficacy analyses because their prebaseline scans were not compliant with the protocol, preventing an adequate assessment of tumor response. Efficacy was evaluated in the pooled intent-to-treat population (PD-L1 TPS ≥1%) and PD-L1 TPS ≥50% population; safety was evaluated in the pooled population of patients who received at least one dose of study treatment. All analyses were descriptive and not controlled for multiplicity.

The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate OS, PFS, and DOR. For OS and PFS, hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the treatment differences were based on the Cox proportional hazards regression model with treatment as a covariate.

Results

Patient Disposition

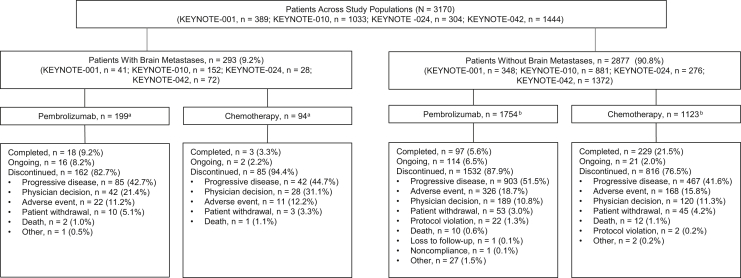

Of the 3170 patients included in this pooled analysis, 293 (9.2%) had baseline brain metastases and 2877 (90.8%) had no known baseline brain metastases. Of the patients with brain metastases, 199 (67.9%) were assigned to pembrolizumab and 94 (32.1%) to chemotherapy. Of the patients without known brain metastases, 1754 (61.0%) and 1123 patients (39.0%) were assigned to pembrolizumab and chemotherapy, respectively (Fig. 1). Data cutoff dates were November 5, 2018 (KEYNOTE-001), March 16, 2018 (KEYNOTE-010), July 10, 2017 (KEYNOTE-024), and September 4, 2018 (KEYNOTE-042). Median (range) duration of follow-up was 12.9 (0.1−43.7) months overall, 18.4 (0.5–43.7) for patients with brain metastases, and 12.6 (0.1–42.5) months for patients without brain metastases.

Figure 1.

Patient disposition of pooled analysis. We included patients from the KEYNOTE-042 China extension study in this analysis; therefore, the number of enrolled patients is higher than previously reported.13aThree patients allocated to pembrolizumab and four to chemotherapy did not receive study treatment. bA total of 11 patients allocated to pembrolizumab and 57 to chemotherapy did not receive study treatment.

Baseline characteristics were generally similar between patients with and without brain metastases (Table 1), although the brain metastases group had a lower percentage of men (51.9% versus 66.9%), a higher percentage of patients with nonsquamous histology (86.0% versus 65.7%) and EGFR (11.3% versus 3.6%) genetic aberrations, and a lower percentage of treatment-naive patients (34.5% versus 59.4%). Approximately half of the patients with (54.6%) and without (50.1%) brain metastases had PD-L1 TPS ≥50% at baseline.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics in Patients With and Without Brain Metastases (Pooled Intent-to-Treat Population)

| Characteristics | With Brain Metastases |

Without Brain Metastases |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pembrolizumab (n = 199) | Chemotherapy (n = 94) | Pembrolizumab (n = 1754) | Chemotherapy (n = 1123) | |

| Male | 99 (49.7) | 53 (56.4) | 1146 (65.3) | 778 (69.3) |

| Age, median (range), y | 59.0 (31–88) | 60.0 (31–81) | 64.0 (20–93) | 64.0 (32–90) |

| ECOG | ||||

| 0 | 59 (29.6) | 29 (30.9) | 580 (33.1) | 348 (31.0) |

| 1 | 139 (69.8) | 65 (69.1) | 1167 (66.5) | 772 (68.7) |

| 2 or 3a | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 5 (0.3) | 2 (0.2) |

| Unknown or missing | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) |

| Smoking history | ||||

| Current or former | 159 (79.9) | 77 (81.9) | 1407 (80.2) | 888 (79.1) |

| Never | 39 (19.6) | 15 (16.0) | 346 (19.7) | 230 (20.5) |

| Missing | 1 (0.5) | 2 (2.1) | 1 (0.1) | 5 (0.4) |

| Histology | ||||

| Nonsquamous | 173 (86.9) | 79 (84.0) | 1181 (67.3) | 709 (63.1) |

| Squamous | 21 (10.6) | 8 (8.5) | 523 (29.8) | 384 (34.2) |

| Other or unknown | 5 (2.5) | 7 (7.4) | 50 (2.9) | 30 (2.7) |

| EGFR mutationb | 27 (13.6) | 6 (6.4) | 82 (4.7) | 21 (1.9) |

| ALK translocationb | 2 (1.0) | 0 | 13 (0.7) | 2 (0.2) |

| Previous systemic therapiesc | ||||

| 0 | 55 (27.6) | 46 (48.9) | 886 (50.5) | 822 (73.2) |

| 1 | 61 (30.7) | 29 (30.9) | 509 (29.0) | 215 (19.1) |

| ≥2 | 83 (41.7) | 19 (20.2) | 359 (20.5) | 86 (7.7) |

| PD-L1 TPS | ||||

| ≥50% | 112 (56.3) | 48 (51.1) | 842 (48.0) | 598 (53.3) |

| 1%–49% | 87 (43.7) | 46 (48.9) | 912 (52.0) | 525 (46.7) |

Note: Values are n (%) of patients unless indicated otherwise.

ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; PD-L1, programmed death-ligand-1; TPS, tumor proportion score.

Most patients with an ECOG performance status of 2 or 3 during screening improved to 1 by the time the patients were randomized.

Patients with EGFR or ALK genomic tumor aberrations were not excluded from enrollment in KEYNOTE-001 or KEYNOTE-010.

Includes adjuvant and neoadjuvant therapies.

Overall Survival

At data cutoff, among patients with baseline brain metastases, 139 of 199 patients (69.8%) in the pembrolizumab group and 70 of 94 (74.5%) in the chemotherapy group had died. Among patients without baseline brain metastases, 1245 of 1754 patients (71.0%) in the pembrolizumab group and 846 of 1123 (75.3%) in the chemotherapy group had died.

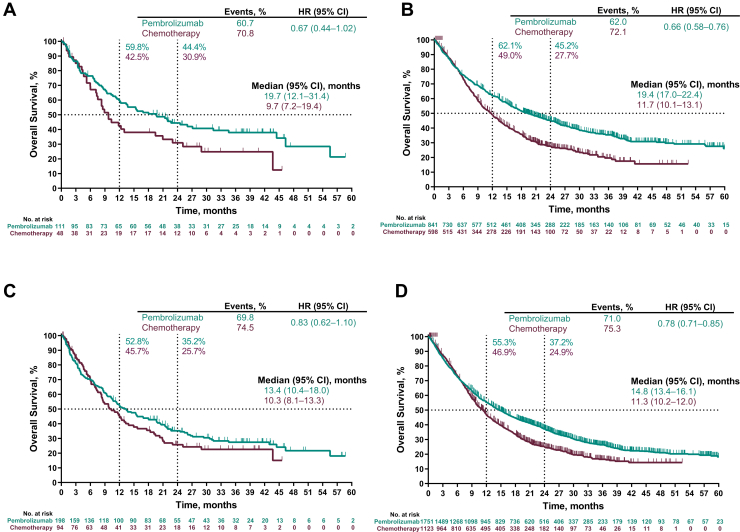

Among patients with PD-L1 TPS ≥50% with brain metastases at baseline, the HR for OS (pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy) was 0.67 (95% CI: 0.44–1.02); median OS was 19.7 (95% CI: 12.1–31.4) and 9.7 (95% CI: 7.2–19.4) months, respectively (Fig. 2A). Among patients with PD-L1 TPS ≥50% without brain metastases, the HR for OS was 0.66 (95% CI: 0.58–0.76); median OS was 19.4 (95% CI: 17.0–22.4) and 11.7 (95% CI: 10.1–13.1) months, respectively (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Overall survival in patients with a PD-L1 TPS of ≥50% in patients (A) with and (B) without baseline brain metastases and in patients with a PD-L1 TPS of ≥1% in patients (C) with and (D) without baseline brain metastases. Four patients in the pooled intent-to-treat population had missing overall survival data. CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1; TPS, tumor proportion score.

OS also favored the pembrolizumab group among patients with PD-L1 TPS ≥1%. Among patients with brain metastases, the HR for OS was 0.83 (95% CI: 0.62–1.10); median OS was 13.4 (95% CI: 10.4–18.0) and 10.3 (95% CI: 8.1–13.3) months, respectively (Fig. 2C). For patients without brain metastases, the HR for OS was 0.78 (95% CI: 0.71–0.85); median OS was 14.8 (95% CI: 13.4–16.1) and 11.3 (95% CI: 10.2–12.0) months, respectively (Fig. 2D).

Progression-Free Survival

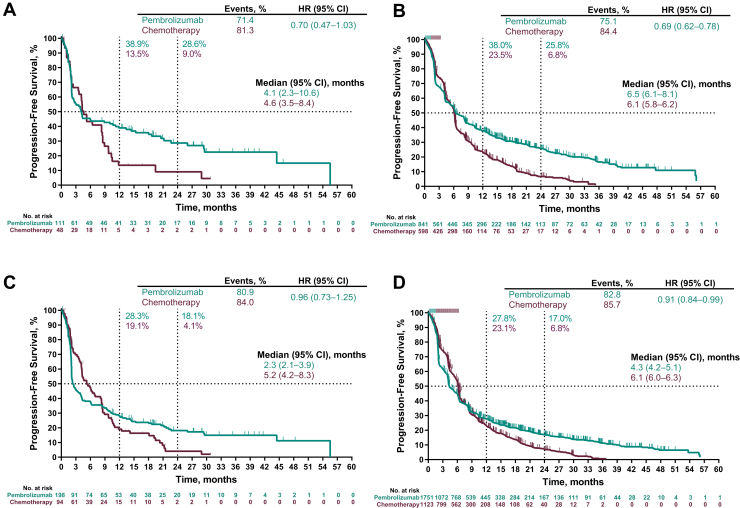

At data cutoff, among patients with baseline brain metastases, 161 of 199 patients (80.9%) in the pembrolizumab group and 79 of 94 (84.0%) in the chemotherapy group had disease progression or died. Among patients without baseline brain metastases, 1452 of 1754 patients (82.8%) in the pembrolizumab group and 962 of 1123 (85.7%) in the chemotherapy group had disease progression or died. Among patients with PD-L1 TPS ≥50%, the HR for PFS (pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy) was 0.70 (95% CI: 0.47–1.03) in patients with baseline brain metastases (Fig. 3A) and 0.69 (95% CI: 0.62–0.78) in patients without (Fig. 3B). Among patients with PD-L1 TPS ≥1%, the HR for PFS was 0.96 (95% CI: 0.73–1.25) in patients with brain metastases (Fig. 3C) and 0.91 (95% CI: 0.84–0.99) in patients without (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

Progression-free survival in patients with a PD-L1 TPS of ≥50% in patients (A) with and (B) without baseline brain metastases and in patients with a PD-L1 TPS of ≥1% in patients (C) with and (D) without baseline brain metastases. The response was assessed per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1 by blinded, independent central review. Four patients in the pooled intent-to-treat population had missing progression-free survival data. CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1; TPS, tumor proportion score.

Systemic ORR

ORR was higher among patients assigned to pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy irrespective of baseline brain metastasis status (Table 2). Among patients with PD-L1 TPS ≥50%, ORR with pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy was 33.9% versus 14.6% in patients with brain metastases and 38.1% versus 26.1% in patients without. Among patients with PD-L1 TPS ≥1%, ORR with pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy was 26.1% versus 18.1% in patients with brain metastases and 25.8% versus 22.2% in patients without.

Table 2.

ORR in Patients With and Without Brain Metastases by PD-L1 TPS (Pooled Intent-to-Treat Population)

| Outcome | With Brain Metastases |

Without Brain Metastases |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pembrolizumab | Chemotherapy | Pembrolizumab | Chemotherapy | |

| PD-L1 TPS, ≥50%, n | 112 | 48 | 842 | 598 |

| ORR, n (%) [95% CI] | 38 (33.9) [25.3–43.5] | 7 (14.6) [6.1–27.8] | 321 (38.1) [34.8–41.5] | 156 (26.1) [22.6–29.8] |

| Response, n (%) | ||||

| Complete response | 3 (2.7) | 0 | 22 (2.6) | 2 (0.3) |

| Partial response | 35 (31.3) | 7 (14.6) | 299 (35.5) | 154 (25.8) |

| Stable disease | 24 (21.4) | 19 (39.6) | 233 (27.7) | 246 (41.1) |

| Progressive disease | 36 (32.1) | 11 (22.9) | 190 (22.6) | 97 (16.2) |

| Not evaluable | 3 (2.7) | 2 (4.2) | 18 (2.1) | 11 (1.8) |

| No assessment | 9 (8.0) | 9 (18.8) | 75 (8.9) | 88 (14.7) |

| Response duration, median (range), mo | NR (4.0+ to 41.7+) | 7.6 (2.9+ to 28.6+) | 33.9 (1.4+ to 49.3+) | 8.2 (1.6+ to 30.4+) |

| PD-L1 TPS ≥1%, n | 199 | 94 | 1754 | 1123 |

| ORR, n (%) [95% CI] | 52 (26.1) [20.2–32.8] | 17 (18.1) [10.9–27.4] | 452 (25.8) [23.7–27.9] | 249 (22.2) [19.8–24.7] |

| Response, n (%) | ||||

| Complete response | 3 (1.5) | 1 (1.1) | 29 (1.7) | 3 (0.3) |

| Partial response | 49 (24.6) | 16 (17.0) | 423 (24.1) | 246 (21.9) |

| Stable disease | 37 (18.6) | 41 (43.6) | 604 (34.4) | 517 (46.0) |

| Progressive disease | 80 (40.2) | 18 (19.1) | 474 (27.0) | 174 (15.5) |

| Not evaluable | 7 (3.5) | 4 (4.3) | 38 (2.2) | 23 (2.0) |

| No assessment | 21 (10.6) | 14 (14.9) | 169 (9.6) | 160 (14.2) |

| Response duration, median (range), mo | NR (3.3 to 46.2+) | 8.3 (2.0+ to 28.6+) | 30.4 (1.4+ to 49.3+) | 8.1 (1.1+ to 30.4+) |

Note: Responses were based on blinded, independent central review assessment per RECIST version 1.1.

CI, confidence interval; NR, not reached; ORR, objective response rate; PD-L1, programmed death ligand-1; RECIST, Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors; TPS, tumor proportion score.

DOR was longer among patients who received pembrolizumab. Among patients with PD-L1 TPS ≥50%, median (range) DOR was not reached (4.0+ to 41.7+ mo) in the pembrolizumab group and was 7.6 (2.9+ to 28.6+) months in the chemotherapy group among patients with brain metastases and was 33.9 (1.4+ to 49.3+) and 8.2 (1.6+ to 30.4+) months, respectively, among patients without brain metastases (+ indicates no progressive disease at the time of last disease assessment). Among patients with PD-L1 TPS ≥1%, median (range) DOR was not reached (3.3 to 46.2+ mo) in the pembrolizumab group and was 8.3 (2.0+ to 28.6+) months in the chemotherapy group among patients with brain metastases and was 30.4 (1.4+ to 49.3+) and 8.1 (1.1+ to 30.4+) months, respectively, among patients without.

Safety

The median (range) treatment duration for patients with baseline brain metastases given pembrolizumab or chemotherapy was 2.8 (0.03–39.6) and 2.9 (0.03–29.5) months, respectively. In this population, treatment-related AEs of any grade occurred in 130 of 196 patients (66.3%) in the pembrolizumab group and 76 of 90 (84.4%) in the chemotherapy group (Table 3). Treatment-related AEs of greater than or equal to grade 3 occurred in 29 patients (14.8%) and 41 patients (45.6%), respectively. Treatment-related AEs resulted in the discontinuation of study treatment for 12 patients (6.1%) in the pembrolizumab group and 9 (10.0%) in the chemotherapy group; three (1.5%) and three patients (3.3%), respectively, died of treatment-related AEs. A total of 19 patients (9.7%) had at least one treatment-related AE affecting the nervous system in the pembrolizumab group compared with 24 (26.7%) in the chemotherapy group; the most common are detailed in Table 3. Immune-mediated AEs and infusion reactions, regardless of relationship to study treatment, occurred in 41 patients (20.9%) and eight patients (8.9%) in the pembrolizumab and chemotherapy groups, respectively.

Table 3.

Treatment-Related AEs in Patients With and Without Brain Metastases (Pooled Safety Population)

| Treatment-Related AEs | With Brain Metastases |

Without Brain Metastases |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pembrolizumab (n = 196) | Chemotherapy (n = 90) | Pembrolizumab (n = 1743) | Chemotherapy (n = 1066) | |

| Any | 130 (66.3) | 76 (84.4) | 1172 (67.2) | 941 (88.3) |

| Grade ≥3 | 29 (14.8) | 41 (45.6) | 311 (17.8) | 460 (43.2) |

| Led to discontinuation of study treatment | 12 (6.1) | 9 (10.0) | 144 (8.3) | 117 (11.0) |

| Led to death | 3 (1.5) | 3 (3.3) | 22 (1.3) | 21 (2.0) |

| Affected the nervous system | 19 (9.7) | 24 (26.7) | 122 (7.0) | 283 (26.5) |

| Most common (≥2% in any group) | ||||

| Neuropathy peripheral | 1 (0.5) | 7 (7.8) | 9 (0.5) | 83 (7.8) |

| Dysgeusia | 3 (1.5) | 8 (8.9) | 23 (1.3) | 45 (4.2) |

| Peripheral sensory neuropathy | 1 (0.5) | 3 (3.3) | 12 (0.7) | 58 (5.4) |

| Paresthesia | 1 (0.5) | 5 (5.6) | 12 (0.7) | 34 (3.2) |

| Headache | 7 (3.6) | 3 (3.3) | 24 (1.4) | 11 (1.0) |

| Hypesthesia | 0 | 1 (1.1) | 3 (0.2) | 25 (2.3) |

| Immune-mediated AEs and infusion reactionsa | 41 (20.9) | 8 (8.9) | 440 (25.2) | 80 (7.5) |

| Grade 3−5 | 10 (5.1) | 1 (1.1) | 129 (7.4) | 17 (1.6) |

Note: AEs were graded on the basis of National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.03. Values are n (%) of patients.

AEs, adverse events.

Immune-mediated AEs were classified on the basis of a list of preferred terms identified by the sponsor as having an immune etiology. All immune-mediated AEs and infusion reactions are included, regardless of relationship to study drug.

Safety results in patients without brain metastases (Table 3) were consistent with those in patients with brain metastases. The median (range) treatment duration for patients without brain metastases given pembrolizumab and chemotherapy was 4.7 (0.03–76.0) and 3.5 (0.03–34.8) months, respectively.

Discussion

In this pooled analysis, pembrolizumab monotherapy improved clinical outcomes versus chemotherapy in patients with PD-L1–positive advanced or metastatic NSCLC, irrespective of the presence of treated, stable brain metastases at baseline. The OS and PFS benefits of pembrolizumab in patients with brain metastases were similar to that reported in patients without known brain metastases. ORRs were higher with pembrolizumab than with chemotherapy, and median DOR was not reached in the pembrolizumab group. Consistent with the individual study results, this pooled analysis showed a greater magnitude of benefit in patients with PD-L1 TPS ≥50% versus PD-L1 TPS ≥1%. Pembrolizumab had a manageable safety profile both in patients with and without baseline brain metastases.

A phase 2 study provided evidence that pembrolizumab had activity in the CNS comparable with that in systemic disease.15,16 The updated analysis included 42 patients with NSCLC and untreated or progressive brain metastases on the basis of brain MRI.16 The brain metastasis response rate (primary end point) was 30% in the PD-L1−positive NSCLC cohort with measurable disease, with no responses in the PD-L1−negative cohort. CNS responses were durable (DOR = 5.7 mo), with 10 of 11 patients still responding at the time of the last on-study MRI.16 The mechanism by which immunotherapy might be effective within the CNS is an area of ongoing investigation. Brain metastases disrupt the integrity of the blood-brain barrier and blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier, with several studies now reporting the presence of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in brain metastases of several primary cancers, including NSCLC.17

Our results are consistent with those of previous trials in which monotherapy with other PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors has shown benefit in patients with advanced NSCLC with and without brain metastases,18,19 lending further support of a role for immunotherapy in these patients. Our pooled population comprised a large sample size, but the proportions of patients with treated and stable brain metastases were similar in our analysis (10.2%) and the previous studies (9.5%−14.5%).18,19 In our analysis, median OS was 19.7 and 13.4 months in patients receiving pembrolizumab with brain metastases and PD-L1 TPS ≥50% and PD-L1 TPS ≥1%, respectively, which was greater than the median OS in the chemotherapy arm (9.7 and 10.3 mo, respectively); HRs for OS were 0.67 (95% CI: 0.44‒1.02) and 0.83 (95% CI: 0.62‒1.10), respectively. A similar pattern was observed in the phase 3 study of atezolizumab in which median OS was 16.0 months with atezolizumab versus 11.9 months with docetaxel. Real-world evidence in patients with advanced NSCLC treated with first-line or later pembrolizumab, with or without chemotherapy, or second-line or later nivolumab parallels the clinical trial experience reporting similar benefits in patients presenting with and without brain metastases.20, 21, 22

No new safety signals were identified in our analysis. The safety profile of pembrolizumab monotherapy was similar in patients with and without baseline brain metastases and was more favorable than that of chemotherapy. The incidences of treatment-related AEs, treatment-related AEs of grade ≥3, and those leading to death, discontinuation of study treatment, or affecting the nervous system were all lower with pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy. The presence of brain metastases was not associated with an increased incidence of nervous system events in either treatment group. Our results are generally consistent with those of other PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors.19,22 In contrast to our findings with pembrolizumab, one randomized controlled trial reported less-favorable safety in a relatively small sample of patients with advanced NSCLC with brain metastases (n = 60) compared with those without brain metastases (n = 362).18 In that trial, among patients treated with atezolizumab, those with brain metastases experienced more treatment-related AEs, including events that were grade ≥3, serious, or neurologic.18

Our results parallel those of first-line combination therapy with pembrolizumab plus platinum-based chemotherapy versus platinum-based chemotherapy alone in patients with advanced NSCLC with and without baseline brain metastases.23 In that analysis, which pooled results from three clinical trials (KEYNOTE-021, -189, and -407), combination therapy was associated with improved outcomes, regardless of the presence of brain metastases, and a manageable safety profile.

A strength of our analysis is that we evaluated outcomes by pooling data across four individual trials, allowing for a robust assessment in this clinically important group. Limitations include the fact that no adjustments were made for multiplicity and outcomes were retrospectively evaluated. However, exploratory subgroup analyses among patients with brain metastases were prespecified in all studies. Another limitation is that patients with untreated or active brain metastases were not enrolled in any of the trials. Moreover, CNS imaging was not uniformly collected at every individual time point for response assessment in any of the studies, and intracranial responses were not specifically collected; the central reader was not asked to evaluate intracranial responses nor specify the site of progressive disease. Thus, whether there was any benefit of pembrolizumab on intracranial response, intracranial disease progression, and brain-related DOR and PFS could not be assessed. Details on prior local therapy for brain metastases were not captured appropriately, and hence, not analyzed. Characteristics of the studies pooled may also have influenced the outcome. For example, KEYNOTE-001 enrolled predominantly previously treated patients and lacked a control arm. Thus, in the pooled analysis, the chemotherapy arm had a greater percentage of treatment-naive patients, which may have introduced bias in favor of chemotherapy for end points such as OS. Despite this potential bias, the between-treatment group differences in OS favored pembrolizumab. In addition, KEYNOTE-024 included only patients with PD-L1 TPS ≥50%, and thus the PD-L1 TPS ≥1% group in our analysis may be enriched for PD-L1 TPS ≥50% patients. However, given the relatively small number of patients in KEYNOTE-024 (N = 305) compared with the total population in this pooled analysis, this is unlikely to have a substantial impact on the overall findings.

In conclusion, pembrolizumab monotherapy improved clinical outcomes with fewer AEs than chemotherapy in patients with treatment-naive and previously treated PD-L1‒positive, advanced or metastatic NSCLC, including those with treated, stable brain metastases. Clinical outcomes associated with pembrolizumab were similar in patients with and without brain metastases. Pembrolizumab monotherapy is a standard-of-care therapy in the population studied.

CRediT Authorship Contribution Statement

Aaron S. Mansfield: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing.

Roy S. Herbst: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing–review and editing.

Gilberto de Castro Jr., Rina Hui, Martin Reck: Investigation, Formal Analysis, Writing–review and editing, Resources.

Nir Peled, Silvia Novello, Andrew G. Robinson, Ayman Samkari: Investigation, Writing–review and editing.

Dong-Wan Kim: Investigation, Writing–review and editing, Resources

Miyako Satouchi, Yi-Long Wu, Edward B. Garon, Victoria Ebiana: Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing–review and editing.

Bilal Piperdi: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Data Curation, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition.

Jianxin Lin: Software, Validation, Formal Analysis, Data Curation, Writing–review and editing, Visualization, Funding Acquisition.

Tony S. K. Mok: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing, Resources.

Data Sharing Statement

Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, New Jersey (Merck Sharp & Dohme) is committed to providing qualified scientific researchers access to anonymized data and clinical study reports from the company’s clinical trials for the purpose of conducting legitimate scientific research. Merck Sharp & Dohme is also obligated to protect the rights and privacy of trial participants and, as such, has a procedure in place for evaluating and fulfilling requests for sharing company clinical trial data with qualified external scientific researchers. The Merck Sharp & Dohme data sharing website (available at: http://engagezone.msd.com/ds_documentation.php) outlines the process and requirements for submitting a data request. Applications will be promptly assessed for completeness and policy compliance. Feasible requests will be reviewed by a committee of Merck Sharp & Dohme subject matter experts to assess the scientific validity of the request and the qualifications of the requestors. In line with data privacy legislation, submitters of approved requests must enter into a standard data sharing agreement with Merck Sharp & Dohme before data access is granted. Data will be made available for request after product approval in the United States and European Union or after product development is discontinued. There are circumstances that may prevent Merck Sharp & Dohme from sharing requested data, including country or region-specific regulations. If the request is declined, it will be communicated to the investigator. Access to genetic or exploratory biomarker data requires a detailed, hypothesis-driven statistical analysis plan that is collaboratively developed by the requestor and Merck Sharp & Dohme subject matter experts; after approval of the statistical analysis plan and execution of a data-sharing agreement, Merck Sharp & Dohme will either perform the proposed analyses and share the results with the requestor or will construct biomarker covariates and add them to a file with clinical data that is uploaded to an analysis portal so that the requestor can perform the proposed analyses.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this research was provided by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, New Jersey. Representatives of the funder participated in study design, analysis, and interpretation of the data and supported the decision to submit the article for publication. Medical writing and editorial assistance were provided by Jennifer L. Venzie of ICON plc (North Wales, PA), funded by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, New Jersey.

Footnotes

Disclosure: Dr. Mansfield reports receiving honorarium on behalf of his institution from AstraZeneca, AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Genentech; research funding from National Institutes of Health, Novartis, and Verily; medical society/research group/foundation leadership that were not remunerated; and is a Mesothelioma Applied Research Foundation board member. Dr. Herbst reports receiving commercial research grants from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, and Merck; is a consultant/advisory board member for AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Biodesix, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, EMD Serono, Genentech/Roche, Heat Biologics, Infinity Pharmaceuticals, Loxo Oncology, Merck, Nektar Therapeutics, Neon Therapeutics, NextCure, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi, Seattle Genetics, Shire, Spectrum Pharmaceuticals, Symphogen, Tesaro, ARMO BioSciences, Genmab, and Tocagen; and is a board member (nonexecutive/independent) for Junshi Biosciences. Dr. Castro, Jr. reports receiving honoraria from Merck Sharp & Dohme, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche, Bayer, Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, and Pfizer; has an advisory/consultancy role for AstraZeneca, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche, Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, Bayer, Merck Serono, and Yuhan; provides speakers bureau/expert testimony for Merck Sharp & Dohme, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Roche, Bayer, and TEVA; receives research grant/funding on behalf of his institution from Merck Sharp & Dohme, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche, Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, and Merck Serono; and receives personal fees for travel/accommodation/expenses from Merck Sharp & Dohme, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche, Bayer, Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, and Pfizer. Dr. Hui reports receiving personal fees for advisory boards for Merck Sharp & Dohme, AstraZeneca, Novartis, Roche, and Bristol-Myers Squibb; and speaker honoraria from Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Peled reports receiving grants, personal fees, and honoraria for serving as an advisor for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, NovellusDx, FMI, and Guardant360. Dr. Kim reports receiving research funding on behalf of his institution from Alpha Biopharma, AstraZeneca/Medimmune, Hanmi, Janssen, Merus, Mirati Therapeutics, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Ono Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Roche/Genentech, Takeda, TP Therapeutics, Xcovery, and Yuhan. Dr. Novello reports being a member of the speakers’ bureau/advisor for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Takeda, Roche, and Merck Sharp & Dohme. Dr. Satouchi reports receiving honoraria from Merck Sharp & Dohme, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Ono Pharmaceutical, Bristol-Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca, Taiho Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Novartis, Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim; and grants from Merck Sharp & Dohme, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Ono Pharmaceutical, Bristol-Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim, AbbVie, Takeda, and Eli Lilly. Dr. Wu reports receiving honoraria from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Roche, Pierre Fabre, Pfizer, and Sanofi; consulting or advisory role with AstraZeneca, Roche, Merck, and Boehringer Ingelheim; and research funding to the institution from Boehringer Ingelheim and Roche. Dr. Garon reports serving as advisory/consultancy role for Dracen, EMD Serono, and Merck; and receiving research funding on behalf of his institution from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Genentech, Neon Therapeutics, Iovance Biotherapeutics, Dynavax, and Mirati Therapeutics. Dr. Reck reports receiving honoraria for consulting and lectures for Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Merck, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, AbbVie, Roche, and Novartis; speakers bureau and advisory board member for Amgen, AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche; and receiving research grant to his institution from Merck Sharp & Dohme, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc. Dr. Robinson reports receiving grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Roche, and AstraZeneca. Drs. Samkari and Lin are employees of Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, New Jersey. Dr. Piperdi is an employee of Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, New Jersey and owns stock in Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, New Jersey. Dr. Ebiana was a former employee of Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, New Jersey. Dr. Mok reports receiving grants or research support from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Clovis Oncology, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, SFJ Pharmaceuticals, and Xcovery; speakers fees from AstraZeneca, Roche/Genentech, Pfizer, Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Taiho, and Takeda Oncology; honoraria from AstraZeneca, Roche/Genentech, Pfizer, Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Merck Serono, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, SFJ Pharmaceuticals, ACEA Biosciences, Inc., Vertex Pharmaceuticals, Bristol-Myers Squibb, OncoGenex Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Celgene, Ignyta, Inc., Fishawack Facilitate Ltd., Takeda Oncology, and Janssen; is a major stockholder in Sanomics Ltd.; and is an advisory board member for AstraZeneca, Roche/Genentech, Pfizer, Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Clovis Oncology, Merck Serono, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, SFJ Pharmaceuticals, ACEA Biosciences, Inc., Vertex Pharmaceuticals, Bristol-Myers Squibb, geneDecode Co., Ltd., OncoGenex Technologies Inc., Celgene, Ignyta, Inc., Cirina, Fishawack Facilitate Ltd., Janssen, Takeda, and ChiMed.

References

- 1.Gibson A.J.W., Li H., D’Silva A. Impact of number versus location of metastases on survival in stage IV M1b non-small cell lung cancer. Med Oncol. 2018;35:117. doi: 10.1007/s12032-018-1182-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borghaei H., Paz-Ares L., Horn L. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1627–1639. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carbone D.P., Reck M., Paz-Ares L. First-line nivolumab in stage IV or recurrent non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:2415–2426. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1613493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brahmer J., Reckamp K.L., Baas P. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:123–135. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Govindan R., Szczesna A., Ahn M.J. Phase III trial of ipilimumab combined with paclitaxel and carboplatin in advanced squamous non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:3449–3457. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.71.7629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rittmeyer A., Barlesi F., Waterkamp D. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (OAK): a phase 3, open-label, multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389:255–265. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32517-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mansfield A.S., Aubry M.C., Moser J.C. Temporal and spatial discordance of programmed cell death-ligand 1 expression and lymphocyte tumor infiltration between paired primary lesions and brain metastases in lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1953–1958. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mansfield A.S., Ren H., Sutor S. Contraction of T cell richness in lung cancer brain metastases. Sci Rep. 2018;8:2171. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-20622-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hendriks L.E.L., Henon C., Auclin E. Outcome of patients with non-small cell lung cancer and brain metastases treated with checkpoint inhibitors. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14:1244–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garon E.B., Rizvi N.A., Hui R. Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2018–2028. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1501824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herbst R.S., Baas P., Kim D.W. Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non–small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387:1540–1550. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01281-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reck M., Rodriguez-Abreu D., Robinson A.G. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1823–1833. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mok T.S., Wu Y., Kudaba I. Final analysis of the phase 3 KEYNOTE-042 study: pembrolizumab (pembro) versus platinum-based chemotherapy (chemo) as first-line therapy for patients (pts) with PD-L1-positive locally advanced/metastatic NSCLC. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(suppl 2):ii38–ii68. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eisenhauer E.A., Therasse P., Bogaerts J. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldberg S.B., Gettinger S.N., Mahajan A. Pembrolizumab for patients with melanoma or non-small-cell lung cancer and untreated brain metastases: early analysis of a non-randomised, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:976–983. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30053-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldberg S.B., Schalper K.A., Gettinger S.N. Pembrolizumab for management of patients with NSCLC and brain metastases: long-term results and biomarker analysis from a non-randomised, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:655–663. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30111-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schulz M., Salamero-Boix A., Niesel K., Alekseeva T., Sevenich L. Microenvironmental regulation of tumor progression and therapeutic response in brain metastasis. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1713. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gadgeel S.M., Lukas R.V., Goldschmidt J. Atezolizumab in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer and history of asymptomatic, treated brain metastases: exploratory analyses of the phase III OAK study. Lung Cancer. 2019;128:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2018.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spigel D.R., Chaft J.E., Gettinger S. FIR: efficacy, safety, and biomarker analysis of a phase II open-label study of atezolizumab in PD-L1-selected patients with NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13:1733–1742. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun L., Davis C.W., Hwang W.T. Outcomes in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer with brain metastases treated with Pembrolizumab-based therapy. Clin Lung Cancer. 2021;22:58–66.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2020.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang G., Cheng R., Wang H. Comparable outcomes of nivolumab in patients with advanced NSCLC presenting with or without brain metastases: a retrospective cohort study. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2020;69:399–405. doi: 10.1007/s00262-019-02462-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crinò L., Bronte G., Bidoli P. Nivolumab and brain metastases in patients with advanced non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2019;129:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2018.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Powell S.F., Rodriguez Abreu D., Langer C.J. Pembrolizumab (pembro) plus platinum-based chemotherapy (chemo) in NSCLC with brain metastases: pooled analysis of KEYNOTE-021, 189, and 407. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(suppl 5):v606–v607. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2021.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]