Abstract

Objectives

To determine the optimal number of examined lymph nodes (ELNs) and examined node stations (ENSs) in patients with radiologically pure-solid NSCLC and to investigate the impact of ELNs and ENSs on accurate staging and long-term survival.

Methods

Data from six institutions in the People’s Republic of China on resected c-stage Ⅰ to Ⅱ NSCLCs presenting as pure-solid tumors were analyzed for the impact of ELNs and ENSs on nodal upstaging, stage migration, recurrence-free survival, and overall survival by using multivariate models. The correlations between different end points and ELNs or ENSs were fitted with a smoother (using Locally Weighted Scatterplot Smoothing tool), and the structural break points were determined by the Chow test.

Results

Both ELNs and ENSs were identified as prognostic factors for overall survival (ENS: hazard ratio [HR], 0.697; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.590–0.824; p < 0.001; ELN: HR, 0.945; 95% CI: 0.909–0.983; p = 0.005) and recurrence-free survival (ENS: HR, 0.863; 95% CI: 0.791–0.941; p = 0.001; ELN: HR, 0.960; 95% CI: 0.938–0.981; p < 0.001). Intraoperative ELNs and ENSs were found to be associated with postoperative nodal upstaging. Cut point analysis revealed an optimal cutoff of 16 LNs and five node stations for patients with c-stage Ⅰ to Ⅱ pure-solid NSCLCs, which were examined in our multi-institutional cohort.

Conclusions

Both ELNs and ENSs are associated with more accurate node staging and better long-term survival. We recommend 16 LNs and five stations as the cut point for evaluating the quality of LN examination for c-stage Ⅰ to Ⅱ patients with radiologically pure-solid NSCLCs.

Keywords: Lymph node dissection, Optimal number, Prognosis, Nodal staging

Introduction

With the introduction of computed tomography (CT) screening for lung cancer and the extensive use of low-dose CT, the detection rate of early stage NSCLC has increased remarkably.1,2 Early stage NSCLCs can manifest as either subsolid or solid tumors on CT scans. Notably, lymph node (LN) involvement is much more frequently observed in radiologically solid tumors than subsolid tumors.3, 4, 5 Therefore, a proposal for LN management of radiologically solid NSCLCs is urgently needed.

LN status plays an important role in determining staging and predicting the long-term survival of patients with resected early stage NSCLCs.6, 7, 8 In recent years, more and more researchers have been interested in the determination of an optimal number of examined LNs (ELNs).7,9,10 Liang et al.9 recommended 16 ELNs as the cut point for evaluating the quality of LN examination or postoperative prognostic stratification for patients with declared node-negative disease through analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database and a Chinese multi-institutional registry. Another study, using the National Cancer Database, reported that eight to 11 nodes should be examined in patients with stage I NSCLCs for accurate staging and favorable outcomes.10 Similar results were observed in other studies in which removal of at least 10 nodes was found to be associated with better survival.11,12 Regrettably, neither the radiologic features of primary tumors nor the examined node stations (ENSs) were detailed in these studies.

For early stage resectable NSCLCs, sampling of a minimum of three N2 stations or a systematic LN dissection (SLND) should be performed according to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines.13 At present, ipsilateral systematic lymphadenectomy in hilar and mediastinal stations, with three groups of N1 and N2 nodes examined respectively, remains the overall standard.6,14 In addition, the LN map proposed by the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) recommends that one or more nodes should be sampled from all mediastinal stations, which, for right-sided tumor-bearing lobes, are 2R, 4R, 7, 8, and 9 and for the left side are 4L, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9.15 Similarly, Darling et al.,16 who launched a randomized trial (ACOSOG Z0030 trial), performed a sampling of 2R, 4R, 7, and 10R for right-sided tumors and 5, 6, 7, and 10L for left-sided tumors. Another point of view, based on the results of several studies, is that lobe-specific LN dissection (LSD) is equivalent to SLND in early stage NSCLCs.14,17,18 Therefore, for radiologically pure-solid NSCLCs that are at risk of occult nodal involvement and pathologic upstaging, the minimum number of ELNs and ENSs has not yet been clarified.

To address these two unresolved issues, we performed analyses of the data collected from six institutions in the People’s Republic of China. By including the information on both ELNs and ENSs, we assessed the relationships between the extent of LN dissection and long-term survival and pathologic upstaging. Advanced statistical methods were applied to determine the optimal threshold for both ELNs and ENSs in patients with pure-solid c-stage I to II NSCLCs.

Materials and Methods

Patient Selection

Ethical approval was obtained from the six participating institutions through their respective institutional review boards. For cases in which individual patient consent was not identified, the chairperson of the ethics committee waived the need for patient consent. Patients with pure-solid cT1a-2bN0-1M0 NSCLCs who underwent R0 pulmonary resection at six medical centers in the People’s Republic of China from January 2012 to December 2014 were reviewed.

In this study, a radiologic pure-solid tumor was defined as a lung tumor that only revealed consolidation without a ground-glass opacity (GGO) component on thin-section CT.19 The definitions of the solid component and GGO component were in line with that of a previous study.19 The largest axial diameter of an area having increased opacification that completely obscured bronchial and vascular structures on the lung window setting (level, −500 Hounsfield unit; width, 1350 Hounsfield unit) was taken as the tumor size. The technical scanning characteristics of the six hospitals are available in Supplementary Table 1. Clinical TNM stages were diagnosed according to the eighth edition of the TNM staging system for lung cancer.20 Clinical N1 stage was defined as having LNs with a short-axis diameter greater than 1 cm on CT scan or fludeoxyglucose uptake higher than that of surrounding normal structures on positron emission tomography (PET) in stations 10, 11, 12, and 13.14 There were four main exclusion criteria: (1) patients with multiple NSCLCs; (2) patients having mediastinal LNs with a short-axis diameter greater than 1 cm on CT scan or fludeoxyglucose uptake higher than that of surrounding normal structures on PET; (3) patients whose lesions were pathologically diagnosed as adenocarcinoma in situ, minimally invasive adenocarcinoma, or benign disease; and (4) patients who required pneumonectomy, sleeve resection, or bilobectomy. Preoperative biopsy and PET-CT were not mandatory. For all the included patients, the findings of preoperative CT were reviewed by the authors (C.D., M.Y., and W.J.). If disagreement occurred, a discussion was held until a consensus was reached. The postoperative follow-ups lasted until March 2019. A total of 1077 patients were included in our study.

Information on Harvested LNs and Nodal Status

LNs were harvested during surgical resection of NSCLC, and the tissue was examined postoperatively by pathologists. Lobar and interlobar (N1) nodes were dissected as part of lung resection. Both the number and the status of harvested LNs and node stations were collected in each patient. ELN was defined as the total number of LNs examined intraoperatively, whereas ENS was defined as the total number of node stations examined overall. A heatmap approach was applied to exhibit the nodal metastasis pattern according to the tumor locations, which reflected the cumulative number of patients with positive LNs in each node station.

Recurrence and Overall Survival as End Points

All patients were followed up from the date of surgery after resection. In the first 2 years, follow-up procedures included chest radiograph and blood examination including measurements of tumor markers every 3 months and chest CT plus or minus contrast scans every 6 months. Subsequent chest radiographs were performed every 6 months, and chest CT plus or minus contrast scans were performed every year. Further examinations, including brain magnetic resonance imaging and bone scintigraphy, were performed when any sign or symptom of tumor recurrence was detected. Locoregional recurrence was defined as tumor recurrence in the ipsilateral hemithorax, including the resection margin, ipsilateral lung, pleura of the hilum, and mediastinal LNs. Distant metastasis was defined as tumor recurrence in the contralateral hemithorax or extrathoracic organs. Recurrence-free survival (RFS) was defined as the time from surgery until local or distant recurrence. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from surgery until all-cause death.

Statistical Analysis

Multivariable Regression Analyses

Theoretically, ELNs and ENSs are highly correlated with the number of positive LNs and the status of node stations, which in turn are highly correlated with the N stage. To address the redundancy and multicollinearity among the variables in an overfitting model, we first performed least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression analysis21 to screen and shrink the data as described in our previous studies22,23 to achieve variant reduction and selection through a tuning parameter (λ). Pearson’s chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables, and an independent sample t test was used to compare the continuous variables among different groups.

Log-rank test and Cox proportional hazards regression model were used to determine the effect of ELNs and ENSs on OS and RFS to visualize the survival curves, which were adjusted for other significant prognostic factors.9 To verify our assumption that more ELNs and ENSs present a greater opportunity to identify positive LNs, we performed logistic regression analysis to detect the predictors associated with postoperative nodal upstaging. In addition, stage migration was assessed by correlating the ELNs and ENSs and the proportion of each nodal stage category (node-negative versus node-positive) by using a binary logistic regression model after adjusting for other potential confounders associated with examined nodes or nodal stage before or during surgery.9

Accuracy of the Number of Involved LNs and Node Stations

To evaluate the accuracy of involved LNs and node stations, we created mathematical models of the number of nodes and stations examined by using hypergeometric distribution and Bayes’ theorem in accordance with previous studies.9,24 In addition, sensitivity analyses were conducted to evaluate whether the association between ELN and OS and RFS was affected by outliers (probably caused by fragmented LNs).10

Fitting of Curves and Determination of Structural Break Points

The curves of odds ratios (ORs) (stage migration) and hazard ratios (HRs) (OS) of each ELN and ENS compared with one ELN or ENS (as a reference) and the curves of mean positive number and probability of undetected positive LNs were fitted by using a smoother (Locally Weighted Scatterplot Smoothing tool) with a bandwidth of 2/3 (default).9 Structural break points were then determined through use of the Chow test, and the break points were considered as the threshold of clinical impact.9 In addition, to assess whether the number of LNs needed to optimize survival was consistent with the number needed to optimize accurate nodal staging, we plotted the frequency of patients with at least one positive LN for each LN count using locally weighted least squares smoothing.25 All clinical data are either revealed as mean plus or minus SD or number (percent values). A two-sided p value less than 0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

All the statistical analyses were performed using R software, version 3.5.3 (http://www.R-project.org) and SPSS for Windows, version 25.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY). The heatmap and survival curves were drawn with GraphPad Prism 7.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Results

Patient Characteristics and Distribution of ELNs and ENSs

Overall, 1077 patients with cT1a-2bN0-1M0 NSCLCs manifesting as radiologic pure-solid tumors who underwent lobectomy (n = 1004), segmentectomy (n = 56), or wedge resection (n = 17) from six hospitals were recruited. The median follow-up time was 62 months. The baseline characteristics of the patient cohort are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Patient Cohort

| Characteristics | No. of patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Total | 1077 (100) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 625 (58.03) |

| Female | 452 (41.97) |

| Age, y | |

| ≤ 60 | 545 (50.60) |

| > 60 | 532 (49.40) |

| Smoking history | |

| Yes | 400 (37.14) |

| No | 677 (62.86) |

| Operated side | |

| Left | 491 (45.59) |

| Right | 586 (54.41) |

| Tumor location | |

| Upper lobe | 646 (59.98) |

| Middle lobe | 69 (6.41) |

| Lower lobe | 362 (33.61) |

| PET scan | |

| Yes | 162 (15.04) |

| No | 915 (84.96) |

| cT | |

| T1 | 608 (56.46) |

| T2 | 469 (43.54) |

| cN | |

| N0 | 998 (92.66) |

| N1 | 79 (7.34) |

| pT | |

| T1 | 547 (50.79) |

| T2 | 516 (47.91) |

| T3 | 10 (0.93) |

| T4 | 4 (0.37) |

| pN | |

| N0 | 837 (77.72) |

| N1 | 104 (9.65) |

| N2 | 136 (12.63) |

| pTNM | |

| Ia | 446 (41.41) |

| Ib | 358 (33.24) |

| IIa | 60 (5.57) |

| IIb | 69 (6.41) |

| IIIa | 141 (13.09) |

| IIIb | 1 (0.095) |

| IV | 2 (0.19) |

| Histologic type | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 188 (17.46) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 796 (73.91) |

| Adenosquamous carcinoma | 35 (3.25) |

| Large cell carcinoma | 32 (2.97) |

| Others | 26 (2.41) |

| Grade of differentiation | |

| Well-differentiated | 75 (6.96) |

| Moderately differentiated | 653 (60.63) |

| Poorly differentiated | 196 (18.20) |

| Not determined | 153 (14.21) |

| Visceral pleural involvement | |

| Yes | 381 (35.38) |

| No | 696 (64.62) |

| Surgical approach | |

| VATS | 965 (89.60) |

| Thoracotomy | 112 (10.40) |

| Types of resection | |

| Lobectomy | 1004 (93.22) |

| Segmentectomy | 56 (5.20) |

| Wedge resection | 17 (1.58) |

| Lymph node dissection | |

| Yes | 1050 (97.49) |

| No | 27 (2.51) |

| Number of N1 stations | |

| 0 | 80 (7.43) |

| 1–4 | 997 (92.57) |

| Number of N1 nodes examined | |

| ≤ 4 | 632 (58.68) |

| > 4 | 445 (41.32) |

| Positive N1 nodes | |

| Yes | 179 (16.62) |

| No | 898 (83.38) |

| Number of N2 stations | |

| 0 | 40 (3.71) |

| 1–7 | 1037 (96.29) |

| Number of N2 nodes examined | |

| ≤ 7 | 629 (58.40) |

| > 7 | 448 (41.60) |

| Positive N2 nodes | |

| Yes | 136 (12.63) |

| No | 941 (87.37) |

| Total number of examined nodes | |

| ≤ 11 | 569 (52.83) |

| > 11 | 508 (47.17) |

| Positive lymph nodes | |

| Yes | 241 (22.38) |

| No | 836 (77.62) |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | |

| Yes | 502 (46.61) |

| No | 477 (44.3) |

| Unknown | 98 (9.1) |

| Adjuvant radiotherapy | |

| Yes | 46 (4.27) |

| No | 900 (83.57) |

| Unknown | 131 (12.16) |

| Locoregional recurrence | |

| Yes | 218 (20.24) |

| No | 859 (79.76) |

| Distant metastasis | |

| Yes | 147 (13.65) |

| No | 930 (86.35) |

| cN/pN upstaging | |

| Yes | 254 (23.58) |

| No | 823 (76.42) |

PET, positron emission tomography; VATS, video-assisted surgery.

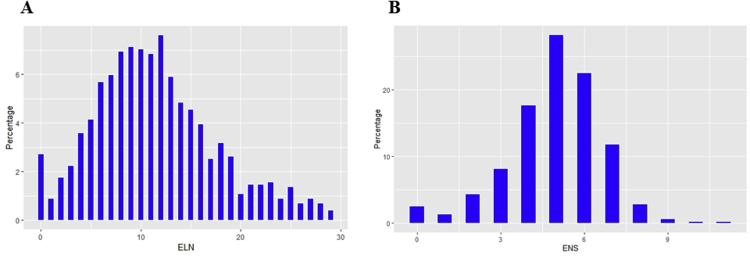

The distribution of ELNs and ENSs in our cohort is shown in Supplementary Figure 1. According to our data, LN dissection was performed on most of the included patients with about four to seven stations examined and six to 13 nodes harvested. As shown in Supplementary Figure 2, we used a heatmap to assess whether nodal metastasis is lobe-specific in pure-solid NSCLCs. Our results revealed that tumor location is not a predictor of nodal metastasis pattern, which highlights that each zone can be involved and should not be neglected.

Identification of ELNs and ENSs as Prognostic Factors

From many clinicopathologic variables with mutual collinearity, both ELNs and ENSs were initially identified as potential survival-related factors by LASSO regression analysis (Supplementary Fig. 3 and Table 2). The variants included in the LASSO regression model are listed in Supplementary Table 2. Multivariate Cox analysis was performed to further confirm ENSs and ELNs as prognostic factors for both OS (ENS: HR, 0.697; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.590–0.824; p < 0.001; ELN: HR, 0.945; 95% CI: 0.909–0.983; p = 0.005) and RFS (ENS: HR, 0.863; 95% CI: 0.791–0.941; p = 0.001; ELN: HR, 0.960; 95% CI: 0.938–0.981; p < 0.001), respectively. To eliminate the potential bias from the count of LN fragments, a sensitivity analysis was performed by limiting the ELNs to fewer than 20, and the ELN number remained statistically significant for both OS (HR, 0.931; 95% CI: 0.891–0.965; p = 0.005) and RFS (HR, 0.951; 95% CI: 0.917–0.968; p < 0.001).

Table 2.

LASSO-Cox Regression Analysis of ELNs and ENSs for Overall Survival and Recurrence-Free Survival

| Characteristics | Overall Survival |

Recurrence-Free Survival |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sig | HR | LL | UL | pa | Sig | HR | LL | UL | pa | |

| ENS (as a continuous variable) | < 0.001 | 0.697 | 0.590 | 0.824 | 0.001 | 0.863 | 0.791 | 0.941 | ||

| ELN (as a continuous variable) | 0.005 | 0.945 | 0.909 | 0.983 | < 0.001 | 0.960 | 0.938 | 0.981 | ||

| LNR | 0.047 | 3.562 | 1.015 | 12.499 | 0.028 | 2.355 | 1.097 | 5.053 | ||

| Lymph node dissection (yes vs. no) | 0.013 | 1.734 | 1.123 | 2.678 | 0.013 | 1.734 | 1.123 | 2.678 | ||

| Operated side (left vs. right) | 0.216 | 1.300 | 0.858 | 1.967 | 0.694 | 1.050 | 0.822 | 1.341 | ||

| Tumor location (lower and middle vs. upper) | 0.262 | 0.279 | ||||||||

| Middle lobe vs. upper lobe | 0.881 | 1.064 | 0.470 | 2.413 | 0.136 | 0.701 | 0.440 | 1.118 | ||

| Lower lobe vs. upper lobe | 0.110 | 0.681 | 0.425 | 1.091 | 0.427 | 0.904 | 0.705 | 1.159 | ||

| pT | 0.039 | 0.082 | ||||||||

| T2 vs. T1 | 0.006 | 1.849 | 1.191 | 2.871 | 0.370 | 1.114 | 0.880 | 1.409 | ||

| T3 vs. T1 | 0.954 | 1.061 | 0.140 | 8.046 | 0.260 | 1.710 | 0.673 | 4.348 | ||

| T4 vs. T1 | 0.184 | 4.049 | 0.514 | 31.900 | 0.020 | 4.003 | 1.239 | 12.934 | ||

| pN | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| N1 vs. N0 | < 0.001 | 4.530 | 2.407 | 8.528 | < 0.001 | 3.417 | 2.351 | 4.967 | ||

| N2 vs. N0 | < 0.001 | 4.150 | 1.970 | 8.742 | < 0.001 | 5.665 | 3.769 | 8.515 | ||

| pM (M1 vs. M0) | < 0.001 | 56.814 | 12.309 | 262.229 | < 0.001 | 24.034 | 5.808 | 99.457 | ||

| Histology ([others, LCC, ASC, ADC] vs. SCC) | 0.428 | 0.209 | ||||||||

| ADC vs. SCC | 0.752 | 0.912 | 0.513 | 1.619 | 0.032 | 1.496 | 1.035 | 2.163 | ||

| ASC vs. SCC | 0.180 | 1.952 | 0.734 | 5.193 | 0.075 | 2.000 | 0.932 | 4.294 | ||

| LCC vs. SCC | 0.472 | 1.475 | 0.512 | 4.249 | 0.457 | 1.373 | 0.595 | 3.167 | ||

| Others vs. SCC | 0.844 | 1.163 | 0.258 | 5.241 | 0.607 | 1.295 | 0.483 | 3.472 | ||

| Surgical approach (thoracotomy vs. VATS) | 0.112 | 0.598 | 0.317 | 1.128 | ||||||

| Grade of Differentiation ([others, poor, moderate] vs. well) | 0.370 | |||||||||

| Moderate vs. well | 0.180 | 1.557 | 0.815 | 2.976 | ||||||

| Poor vs. well | 0.088 | 1.820 | 0.914 | 3.625 | ||||||

| Others vs. well | 0.183 | 1.678 | 0.783 | 3.593 | ||||||

| Types of resection ([wedge resection, segmentectomy] vs. lobectomy) | 0.462 | |||||||||

| Segmentectomy vs. lobectomy | 0.214 | 0.446 | 0.125 | 1.595 | ||||||

| Wedge resection vs. lobectomy | 0.964 | 0.683 | 0.129 | 2.367 | ||||||

| Adjuvant chemotherapy (yes vs. no) | 0.666 | 1.122 | 0.664 | 1.896 | 0.749 | 1.048 | 0.786 | 1.397 | ||

| Adjuvant radiotherapy (yes vs. no) | 0.332 | 1.389 | 0.715 | 2.696 | 0.666 | 0.915 | 0.611 | 1.370 | ||

ADC, adenocarcinoma; ASC, adenosquamous carcinoma; CI, confidence interval; ELN, examined lymph node; ENS, examined node station; HR, hazard ratio; LASSO, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator; LCC, large cell carcinoma; LL, lower limit of 95% CI; LNR, lymph node ratio (the ratio of metastatic lymph nodes to a total number of lymph nodes examined); SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; Sig, significance; UL, upper limit of 95% CI; VATS, video-assisted thoracic surgery

Interaction test p value.

Association of ELNs and ENSs With Nodal Upstaging and Stage Migration

The mean ELN and ENS differed significantly within subgroups of T staging, N staging, histology, tumor location, and types of resection in our cohort (data not shown). As a number of confounding factors are associated with occult mediastinal LN metastasis, we established a multivariate logistic regression model after performing a LASSO regression analysis (Supplementary Fig. 4). The variants included in the LASSO regression model are listed in Supplementary Table 3. As shown in Table 3, both intraoperative ELNs and ENSs were found to be independent predictors of postoperative cN/pN upstaging in radiologic pure-solid NSCLCs.

Table 3.

Multivariate Logistic Regression for Postoperative Nodal Upstaging

| Characteristics | Nodal Upstaging |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sig | OR | LL | UL | pa | |

| ENS (as a continuous variable) | < 0.001 | 1.062 | 1.030 | 1.096 | |

| ELN (as a continuous variable) | 0.023 | 0.964 | 0.919 | 0.996 | |

| Lymph node dissection (yes vs. no) | 0.998 | 1.334 | 0.658 | 3.125 | |

| Sex (male vs. female) | 0.483 | 0.887 | 0.635 | 1.239 | |

| Operated side (left vs. right) | 0.001 | 1.777 | 1.283 | 2.462 | |

| Tumor location (lower and middle vs. upper) | 0.001 | ||||

| Middle lobe vs. upper lobe | 0.006 | 2.386 | 1.286 | 4.426 | |

| Lower lobe vs. upper lobe | 0.048 | 0.702 | 0.493 | 0.998 | |

| pT | 0.007 | ||||

| T2 vs. T1 | 0.002 | 1.676 | 1.215 | 2.313 | |

| T3 vs. T1 | 0.350 | 2.104 | 0.442 | 10.010 | |

| T4 vs. T1 | 0.098 | 5.591 | 0.729 | 42.904 | |

| Histology ([others, LCC, ASC, ADC] vs. SCC) | 0.001 | ||||

| ADC vs. SCC | 0.137 | 0.349 | 0.087 | 1.395 | |

| ASC vs. SCC | 0.980 | 1.017 | 0.277 | 3.724 | |

| LCC vs. SCC | 0.972 | 0.975 | 0.235 | 4.038 | |

| Others vs. SCC | 0.308 | 2.062 | 0.513 | 8.285 | |

| Grade of differentiation ([others, poor, moderate] vs. well) | 0.001 | ||||

| Moderate vs. well | 0.007 | 4.221 | 1.487 | 11.985 | |

| Poor vs. well | < 0.001 | 7.323 | 2.455 | 21.842 | |

| Others vs. well | 0.035 | 3.622 | 1.094 | 11.988 | |

| Surgical approach (thoracotomy vs. VATS) | < 0.001 | 2.472 | 1.557 | 3.927 | |

| Types of resection ([wedge resection, segmentectomy] vs. lobectomy) | 0.765 | ||||

| Segmentectomy vs. lobectomy | 0.465 | 0.709 | 0.282 | 1.782 | |

| Wedge resection vs. lobectomy | 0.998 | 0.895 | 0.195 | 2.785 | |

ADC, adenocarcinoma; ASC, adenosquamous carcinoma; CI, confidence interval; ELN, examined lymph node; ENS, examined node station; LCC, large cell carcinoma; LL, lower limit of 95% CI; LNR, lymph node ratio (the ratio of metastatic lymph nodes to the total number of lymph nodes examined); OR, odds ratio; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; Sig, significance; UL, upper limit of 95% CI; VATS, video-assisted thoracic surgery.

Interaction test p value.

In addition, the patient cohort was also used to estimate the empirical distributions of the number of positive LNs; these results were then used to calculate the probabilities of having more positive nodes than observed (Supplementary Tables 4–7). As expected, a greater number of harvested LNs and node stations correlated with higher accuracy of nodal staging (Supplementary Tables 4–5) and a lower probability of stage migration (Supplementary Tables 6–7).

Cut Point Analysis for Optimal ELNs and ENSs

Figures 1 and 2 exhibit the fitting curves (Fig. 1A and B; Fig. 2A and B) and corresponding structural break points (Fig. 1C and D; Fig. 2C and D) for both the HRs of OS and RFS in radiologic pure-solid NSCLCs. Our data revealed that the cut points of ELNs (Figs. 1C and 2C) and ENSs (Figs. 1D and 2D) for OS and RFS are almost in agreement.

Figure 1.

LOWESS smoother fitting curves of overall survival (A–B) and determination of structural break points (C–D) with the use of the Chow test. The fitting bandwidth was 2/3. Overall survival was estimated by using the Cox proportional hazards regression model after LASSO regression analysis. ELN, examined lymph node; ENS, examined node station; LASSO, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator; LOWESS, Locally Weighted Scatterplot Smoothing tool.

Figure 2.

LOWESS smoother fitting curves of recurrence-free survival (A–B) and determination of structural break points (C–D) with the use of the Chow test. The fitting bandwidth was 2/3. Recurrence-free survival was estimated by using the Cox proportional hazards regression model after the LASSO regression analysis. ELN, examined lymph node; ENS, examined node station; LASSO, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator; LOWESS, Locally Weighted Scatterplot Smoothing tool.

To determine the cut points of ELNs and ENSs for stage migration, we plotted the fitting curves (Fig .3A and B) and corresponding structural break points (Fig. 3C and D) for the OR of stage migration (Fig. 3). As shown in Figure 3, the probability of stage migration reaches a cut point at 20 LNs (Fig. 3C) and five node stations examined (Fig. 3D). We also plotted the probability of finding at least one positive LN by the ELN and ENS, respectively, using locally weighted least squares smoothing (Supplementary Fig. 5). The probability of finding a positive LN reached a cut point at five node stations examined and 16 harvested LNs (Supplementary Figure 5A and B), which indicated that higher LN and stations yield did not improve the accuracy of nodal staging. The structural break points of the estimated probabilities of having positive nodes or stations in patients with node-negative disease were also determined (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Figure 3.

LOWESS smoother fitting curves of stage migration (A–B) and determination of structural break points (C–D) with the use of the Chow test. The fitting bandwidth was 2/3. Stage migration was estimated by using the Cox proportional hazards regression model after the LASSO regression analysis. ELN, examined lymph node; ENS, examined node station; LASSO, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator; LOWESS, Locally Weighted Scatterplot Smoothing tool.

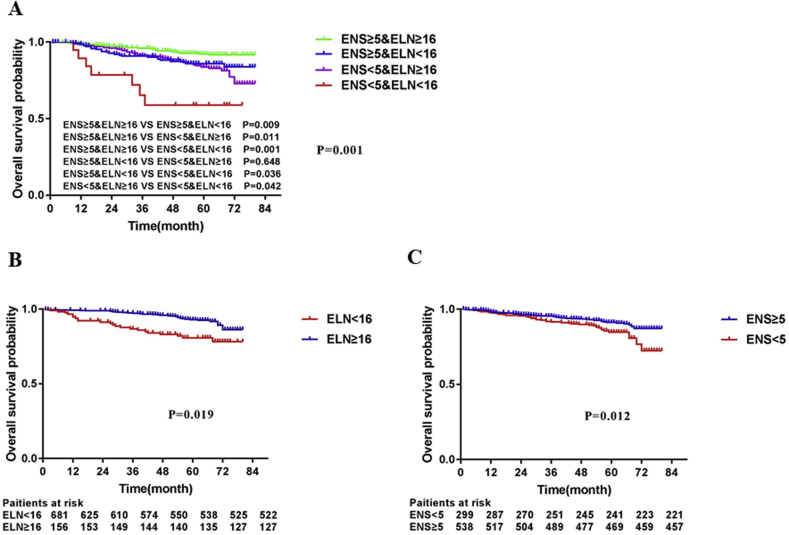

Because OS is the most important issue, we selected the structural break point of OS as the cut point. We used cutoff values of 16 LNs and five stations as the optimal ELN and ENS number for patients with radiologic pure-solid NSCLCs.

The cut point was then examined in our multicenter cohort. Survival analysis revealed that all-cause mortality of patients was significantly reduced with at least 16 LNs (HR, 1.873; 95% CI: 1.132–3.099; p = 0.032) or five node stations (HR, 1.904; 95% CI: 1.294–2.802; p = 0.004) (Supplementary Fig. 7A and B). Similar results were observed in RFS, which was stratified either by 16 LNs (HR, 1.395; 95% CI: 1.069–2.023; p = 0.043) or five node stations (HR, 1.366; 95% CI: 1.018–1.934; p = 0.044) (Supplementary Fig. 7C and D). Subgroup analysis further confirmed that more harvested LNs and examined stations are associated with a better prognosis in patients with pure-solid tumors (Supplementary Fig. 8A), which was also validated in patients with declared node-negative disease (Supplementary Fig. 8B and C).

Discussion

For NSCLCs, the current NCCN guidelines only recommend that LN stations should be counted without providing a minimum number of nodes to be examined, which might be because of the fragile structure of the LN capsule and the surrounding sheath.6 However, the current NCCN guidelines also declare that patients should have a minimum of three N2 stations sampled,13 although no direct supporting evidence is available. Therefore, the minimum number of examined stations and LNs for early stage NSCLCs remains undefined.

The heterogeneity in the examined stations and the number of LNs counted at each station could be derived from a series of factors, including the surgeon’s skills and preferences,6 the individual variations among patients’ LN maps, the location of LNs, the radiologic features of the lesion, and the performance of en bloc resection. Notably, an increasing use of LSD has been witnessed in recent years in which stations 2R and 4R for right upper-lobe tumors; 4L, 5, and 6 for left upper-lobe tumors; and 7, 8, and 9 for lower-lobe tumors on both sides were dissected routinely.26 In 2018, a randomized phase III trial (JCOG1413) further confirmed the noninferiority of LSD compared with SLND.26 The results provided by the studies on LSD14,17,18,26 may partly support the minimum of three N2 stations in early stage NSCLCs. Nevertheless, these studies14,17,18,26 detailed neither the proportion of the included patients with NSCLCs manifesting as GGO nor the number of harvested LNs of the included patients. Undeniably, the biological behaviors of radiologic pure-solid NSCLCs are much more aggressive than those of GGO tumors27, 28, 29 that have been found to reveal the smaller invasive size and lower N stage and more favorable prognosis in our previous study.30 Therefore, our study investigated both the optimal ELN and ENS number in radiologically pure-solid NSCLCs, which has important practical implications.

Our study included many clinicopathologic characteristics, especially cN, pN, and LN status at each station. Interestingly, our initial findings revealed that a considerable part of involved LNs could be detected beyond the lobe-specific zone of the primary tumor location (Supplementary Fig. 2), which is similar to the observed results in other studies.31, 32, 33 The nodal metastasis patterns shown by the heatmap (Supplementary Fig. 2) also highlight the irreplaceable role of SLND for operable pure-solid NSCLCs. By using LASSO regression analysis and multivariate logistic regression analysis, we identified both ELNs and ENSs as independent prognostic factors and risk factors for stage migration. Using the mathematical model based on Bayes’ theorem, the association between a larger number of ELNs or stations and a higher proportion of more advanced N stage was confirmed by the trend of the mean number of positive LNs and involved stations and the probability of accuracy of negative LNs and uninvolved stations (Supplementary Tables 4–7). As illustrated, a more extensive examination of LNs and stations can reduce the risk of undetected positive LNs and involved stations (Supplementary Tables 4–7), which may result in a more thorough elimination of remnants and proper delivery of adjuvant therapy to improve long-term survival.9 Moreover, we identified an optimal cutoff of 16 LNs and five node stations for cT1a-2bN0-1M0 pure-solid NSCLCs (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3).

Interestingly, the optimal number of harvested LNs according to Liang et al.9 precisely agreed with that of our study. Furthermore, our study not only confirmed the prognostic impact of ELNs in patients with declared N0 disease (Supplementary Fig. 8B), which had been found by Liang et al.,9 but also highlighted that of ENSs that merited surgeons’ attention (Supplementary Fig. 8C). Another study of complete hilar and mediastinal lymphadenectomy claimed that the mean total number of harvested LNs was 17.4 plus or minus 7.3,34 which also supports the cut point we found. Notably, a recent study conducted by Adachi et al.14 found that LSD with three node stations dissected is an alternative to SLND in cT1a-2bN0-1M0 NSCLCs, which seemingly conflicted with the optimal number of ENSs. Nevertheless, the final answer remains in suspense because of undetailed radiologic features of primary tumors and a limited number of patients in the Adachi et al.14 study. From our data, the threshold of ELNs could be considered one of the reference indexes for defining inadequate LN sampling, and that of ENSs could serve as supportive evidence for performing SLND in pure-solid NSCLCs.

To our knowledge, this study is the first and the largest one on intraoperative lymphadenectomy in pure-solid NSCLCs using multi-institutional, real-world data sets with robust statistics. We sought to emphasize two major points. First, both ELNs and ENSs are associated with clinical outcomes and stage migration in pure-solid NSCLCs; therefore, a more extensive lymphadenectomy should be performed for patients with pure-solid NSCLCs in case of occult positive LNs. Second, surgeons and pathologists should establish criteria for evaluating the completeness of intraoperative LN management for pure-solid NSCLCs in which the minimal number of harvested LNs and that of stations examined should be included.

We also acknowledge some limitations of our study. First, the retrospective nature of our multicenter study may lead to selection and performance bias. Second, because the fragmentation of nodal tissues was inevitable during the removal of LNs, unavoidable overestimation of ELNs probably had an interference effect on our analysis, even though sensitivity analysis was used to mitigate the bias. To be specific, some of the patients in our cohort had 20 or more LNs examined, which is uncommon in a standard resection for cN0-1 NSCLC. Lastly, the high price of PET-CT limited its extensive use in our patient cohort, which potentially resulted in an underestimation of the cN stage in a subset of patients with pure-solid NSCLCs. Further prospective studies are necessary to address these issues.

In conclusion, both ELNs and ENSs are associated with more accurate node staging and better long-term survival of radiologic pure-solid NSCLC. We recommend 16 LNs and five stations as the cut point for evaluating the quality of LN examination for patients with c-stage I to II NSCLC with radiologic pure-solid tumors.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the projects from Shanghai Hospital Development Center (SHDC12015116), the National Natural Science Foundation of People’s Republic of China (NSFC81770091), Clinical Research Foundation of Shanghai Pulmonary Hospital (FK1943, FK1936, FK1942, and FK1941), Shanghai Municipal Health Commission (2018ZHYL0102, 2019SY072, and 201940018), Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (15411968400 and 14411962600), Suzhou Key Laboratory of Thoracic Oncology (SZS201907), Suzhou Key Discipline for Medicine (SZXK201803), and Municipal Program of People's Livelihood Science and Technology in Suzhou (SS2019061). The authors thank Yiting Zhou (postgraduate student of Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, Medical College of Soochow University) and Yueping Shen (Professor, and Director of Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, Medical College of Soochow University) for providing statistical support.

Footnotes

Drs. Chen and Mao contributed equally to this work.

Drs. Wen, Y. Chen, and C. Chen are listed as co-senior authors.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Note: To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of the Journal of Thoracic Oncology Clinical and Research Reports at www.jtocrr.org and at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtocrr.2020.100035.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary Figure 1.

Supplementary Figure 2.

Supplementary Figure 3.

Supplementary Figure 4.

Supplementary Figure 5.

Supplementary Figure 6.

Supplementary Figure 7.

Supplementary Figure 8.

References

- 1.Dai C., Shen J., Ren Y. Choice of surgical procedure for patients with non-small-cell lung cancer ≤ 1 cm or > 1 to 2 cm among lobectomy, segmentectomy, and wedge resection: a population-based study. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:3175–3182. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.6729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Aberle D.R., Adams A.M., Berg C.D. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:395–409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang L., Jiang W., Zhan C. Lymph node metastasis in clinical stage IA peripheral lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2015;90:41–46. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hattori A., Suzuki K., Matsunaga T. Is limited resection appropriate for radiologically “solid” tumors in small lung cancers? Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;94:212–215. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cho S., Song I.H., Yang H.C., Kim K., Jheon S. Predictive factors for node metastasis in patients with clinical stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96:239–245. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhong W.Z., Liu S.Y., Wu Y.L. Numbers or stations: from systematic sampling to individualized lymph node dissection in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:1143–1145. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.71.8544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.David E.A., Cooke D.T., Chen Y., Nijar K., Canter R.J., Cress R.D. Does lymph node count influence survival in surgically resected non-small cell lung cancer? Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103:226–235. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Osarogiagbon R.U., Decker P.A., Ballman K., Wigle D., Allen M.S., Darling G.E. Survival implications of variation in the thoroughness of pathologic lymph node examination in American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z0030 (Alliance) Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;102:363–369. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.03.095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liang W., He J., Shen Y. Impact of examined lymph node count on precise staging and long-term survival of resected non-small-cell lung cancer: a population study of the US SEER Database and a Chinese multi-institutional registry. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:1162–1170. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.5140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dai J., Liu M., Yang Y. Optimal lymph nodes examination and adjuvant chemotherapy for Stage I lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14:1277–1285. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Samayoa A.X., Pezzi T.A., Pezzi C.M. Rationale for a minimum number of lymph nodes removed with non-small cell lung cancer resection: correlating the number of nodes removed with survival in 98,970 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(suppl 5):1005–1011. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5509-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bosch D.E., Farjah F., Wood D.E., Schmidt R.A. Regional lymph node sampling in lung carcinoma: a single institutional and national database comparison. Hum Pathol. 2018;75:55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2018.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ettinger D.S., Wood D.E., Aisner D.L. Non-small cell lung cancer, version 5.2017, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15:504–535. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2017.0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adachi H., Sakamaki K., Nishii T. Lobe-specific lymph node dissection as a standard procedure in surgery for non-small cell lung cancer: a propensity score matching study. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.08.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rusch V.W., Asamura H., Watanabe H. The IASLC lung cancer staging project: a proposal for a new international lymph node map in the forthcoming seventh edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:568–577. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181a0d82e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Darling G.E., Allen M.S., Decker P.A. Randomized trial of mediastinal lymph node sampling versus complete lymphadenectomy during pulmonary resection in the patient with N0 or N1 (less than hilar) non-small cell carcinoma: results of the American College of Surgery Oncology Group Z0030 Trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;141:662–670. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hishida T., Miyaoka E., Yokoi K. Lobe-specific nodal dissection for clinical stage I and II NSCLC: Japanese multi-institutional retrospective study using a propensity score analysis. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11:1529–1537. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shapiro M., Kadakia S., Lim J. Lobe-specific mediastinal nodal dissection is sufficient during lobectomy by video-assisted thoracic surgery or thoracotomy for early-stage lung cancer. Chest. 2013;144:1615–1621. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-3069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hattori A., Suzuki K., Maeyashiki T. The presence of air bronchogram is a novel predictor of negative nodal involvement in radiologically pure-solid lung cancer. Eur J Cardio Thorac Surg. 2014;45:699–702. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezt467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldstraw P., Chansky K., Crowley J. The IASLC lung cancer staging project: proposals for revision of the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (eighth) edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11:39–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2015.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li B., Cui Y., Diehn M., Li R. Development and validation of an individualized immune prognostic signature in early-stage nonsquamous non-small cell lung cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1529–1537. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen D., Song Y., Zhang F. Genome-wide analysis of lung adenocarcinoma identifies novel prognostic factors and a prognostic score. Front Genet. 2019;10:493. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.00493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Song Y., Chen D., Zhang X., Luo Y., Li S. Integrating genetic mutations and expression profiles for survival prediction of lung adenocarcinoma. Thorac Cancer. 2019;10:1220–1228. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.13072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iyer R.V., Hanlon A., Fowble B. Accuracy of the extent of axillary nodal positivity related to primary tumor size, number of involved nodes, and number of nodes examined. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;47:1177–1183. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)00574-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Groth S.S., Virnig B.A., Whitson B.A. Determination of the minimum number of lymph nodes to examine to maximize survival in patients with esophageal carcinoma: data from the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results database. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139:612–620. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hishida T., Saji H., Watanabe S.I. A randomized Phase III trial of lobe-specific vs. systematic nodal dissection for clinical Stage I–II non-small cell lung cancer (JCOG1413) Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2018;48:190–194. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyx170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hattori A., Matsunaga T., Takamochi K., Oh S., Suzuki K. Importance of ground glass opacity component in clinical stage IA radiologic invasive lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;104:313–320. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2017.01.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hattori A., Hirayama S., Matsunaga T. Distinct clinicopathologic characteristics and prognosis based on the presence of ground glass opacity component in clinical stage IA lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14:265–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aokage K., Miyoshi T., Ishii G. Influence of ground glass opacity and the corresponding pathological findings on survival in patients with clinical Stage I non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13:533–542. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2017.11.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mao R., She Y., Zhu E. A proposal for restaging of invasive lung adenocarcinoma manifesting as pure ground glass opacity. Ann Thorac Surg. 2019;107:1523–1531. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2018.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zheng H., Wang L.M., Bao F. Re-appraisal of N2 disease by lymphatic drainage pattern for non-small-cell lung cancers: by terms of nodal stations, zones, chains, and a composite. Lung Cancer. 2011;74:497–503. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Riquet M., Rivera C., Pricopi C. Is the lymphatic drainage of lung cancer lobe-specific? A surgical appraisal. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2015;47:543–549. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezu226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liang R.B., Yang J., Zeng T.S. Incidence and distribution of lobe-specific mediastinal lymph node metastasis in non-small cell lung cancer: data from 4511 resected cases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25:3300–3307. doi: 10.1245/s10434-018-6394-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Riquet M., Legras A., Mordant P. Number of mediastinal lymph nodes in non-small cell lung cancer: a Gaussian curve, not a prognostic factor. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;98:224–231. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.