Abstract

Background

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is associated with abnormal tau and amyloid-β accumulation in the brain, leading to neurofibrillary tangles, neuropil threads and extracellular amyloid-β plaques. Treatment is limited to symptom management, a disease-modifying therapy is not available. To advance search of therapy approaches, there is a continued need to identify targets for disease intervention both by confirming existing hypotheses and generating new hypotheses.

Methods

We conducted a mRNA-seq study to identify genes associated with AD in post-mortem brain samples from the superior temporal gyrus (STG, n = 76), and inferior frontal gyrus (IFG, n = 65) brain regions. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified correcting for gender and surrogate variables to capture hidden variation not accounted for by pre-planned covariates. The results from this study were compared with the transcriptome studies from the Accelerated Medicine Partnership – Alzheimer’s Disease (AMP-AD) initiative. Over-representation and gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was used to identify disease-associated pathways. Protein-protein interaction (PPI) and weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) analyses were carried out and co-expressed gene modules and their hub genes were identified and associated with additional phenotypic traits of interest.

Results

Several hundred mRNAs were differentially expressed between AD cases and cognitively normal controls in the STG, while no and few transcripts met the same criteria (adjusted p less than 0.05 and fold change greater than 1.2) in the IFG. The findings were consistent at the gene set level with two out of three cohorts from AMP-AD. PPI analysis suggested that the DEGs were enriched in protein-protein interactions than expected by random chance. Over-representation and GSEA analysis suggested genes playing roles in neuroinflammation, amyloid-β, autophagy and trafficking being important for the AD disease process. At the gene level, 10 genes from the STG that were consistently differentially expressed in this study and in the MSBB study (one of the three cohorts within the AMP-AD initiative) were enriched in microglial genes (TREM2, C3AR1, ITGAX, OLR1, CD74, and HLA-DRA), but also included genes with a broader cell type expression pattern such as CDK2AP1. Among the DEGs with supporting evidence from an independent study, CDK2AP1 (most abundantly expressed in astrocyte) was the transcript with strongest association with antemortem cognitive measure (last Mini-Mental State Examination score) and neurofibril tangle burden but also associated with amyloid plaque burden, while OLR1 was the transcript with strongest association with amyloid plaque burden. GSEA and over-representation analyses revealed gene sets related to immune processes including neutrophil degranulation, interleukin 10 signaling, and interferon gamma signaling, complement and coagulation cascades, phosphatidylinositol signaling system, phagosome and neurotransmitter receptors and postsynaptic signal transmission were enriched from this study and replicated in an independent study.

Conclusion

This study identified differential gene sets, common with two out of three AMP-AD cohorts (ROSMAP and MSBB) and highlights microglia and astrocyte as the key cell-types with DGEs associated with AD clinical diagnosis, and/or antemortem cognitive measure as well as neuropathological indices. Future meta-analysis and causal inferential analysis will be helpful in pinpointing the most relevant pathways and genes to intervene.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Differentially expressed gene (DEG), STG, IFG

Highlights

-

•

Ten DEGs from the STG were consistent with the findings in the same brain region from the MSBB cohort.

-

•

Six of these 10 genes are specially expressed in microglia and OLR1 is the gene with strongest association with amyloid burden.

-

•

CDK2AP is the gene with strongest association with tau pathology, neurocognitive measurement, and amyloid burden.

-

•

CDK2AP association with AD is a novel finding.

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the leading cause of dementia yet many AD clinical programs failed in late stage clinical studies. Clear disease targets/pathways for therapeutic intervention at the appropriate stage of the disease trajectory to achieve optimal therapeutic benefit should be re-visited. Finding new targets to intervene the disease early is a top priority to combat AD.

Amyloid plaques and tau paired helical filaments (PHFs) are two pathological hallmarks of AD. Aβ aggregates can be generated following the processing of amyloid precursor protein (APP) by the beta-site APP-cleaving enzyme (BACE1) (Blennow et al., 2006), while tau PHFs are composed of aggregated and hyperphosphorylated tau, observed as neurofibrillary tangles and neuropil threads. The Aβ and tau pathology has elicited tremendous drug development efforts aimed at mitigating pathological Aβ and tau proteins. Other mechanisms including neuronal support and modulation of neuroinflammation are being pursued.

Whole transcriptome profiling is an unbiased approach of surveying tissue or cell-type gene expression levels and has been a key component of target discovery efforts in Accelerating Medicines Partnership: Alzheimer’s Disease (AMP-AD) (Hodes and Buckholtz, 2016). Together with other genetic studies such as genome wide association studies (GWAS) (Jansen et al., 2019; Kunkle et al., 2019; Lambert et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2017; Marioni et al., 2018; Wightman et al., 2020) and epigenome wide association studies (EWAS) (De Jager et al., 2014; Li et al., 2020; Lunnon et al., 2014; Smith et al., 2018, 2020), these approaches have the promise of confirming existing hypotheses and generating new hypotheses.

In this study, we report the results of transcriptome profiling of two post-mortem brain regions, the superior temporal gyrus (STG) and inferior frontal gyrus (IFG), using samples acquired from the Banner Sun Health Research Institute (Beach et al., 2008). Several magnetic resonance imaging studies (Jernigan et al., 2001; Resnick et al., 2003; Sowell et al., 2003) have reported a consistent pattern of age-related grey matter volumetric reductions in the human neocortex including the STG. The STG is a region showing consistent atrophy and epigenetic changes specifically in AD (Gao et al., 2018; Lunnon et al., 2014; Smith et al., 2018; Watson et al., 2016), while the IFG is a region in which atrophy is predominantly related to the aging process (Bakkour et al., 2013), without appreciable additional atrophy in AD, and tau pathology. The results from this study were compared with those from the AMP-AD Knowledge Portal of the STG post-mortem brain RNA-Seq datasets from Mount Sinai VA Medical Center Brain Bank (MSBB), Mayo Clinic, and Religious Orders Study (ROS) or the Rush Memory and Aging Project (MAP) (collectively known as ROSMAP) cohort, respectively (Allen et al., 2016; De Jager et al., 2018; Hodes and Buckholtz, 2016; Wang et al., 2018).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Post-mortem brain tissue mRNA-Seq

Post-mortem brain tissue samples from the STG (Brodmann area (BA) 22) and IFG (BA 44) of subjects with AD, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), or cognitively normal controls were acquired from the Banner Sun Health Research Institute under its brain donation program (Beach et al., 2008, 2015). Selected samples were prioritized for those with short post-mortem interval (PMI) (average PMI: 3.15 h) and BAs within the frontal and temporal cortex with largest number of samples were chosen to ensure the homogeneity of samples for group-wise comparison in the study. Overlapping subjects from this study were also used in a recent epigenome wide association study (Li et al., 2020).

Genomic DNA and total RNA, including miRNA were simultaneously purified from the brain tissue samples using AllPrep DNA/RNA/miRNA Universal Kit (QIAGEN Inc., Germantown, MD, USA) following the manufacturer’s guidelines. Approximately 20–30 mg of tissue was used for each sample. RNA quantity and quality assessment were performed according to established laboratory procedures: RNA quantity was assessed by NanoDrop™ 2000 spectrophotometers (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and RNA total mass and integrity was evaluated using Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer system and the Agilent RNA 6000 Nano Kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) at the site of RNA extraction and again at sequencing facility. A total of 166 RNA samples with RNA integrity number (RIN) greater than 6 were included in the library construction step for mRNA-Seq data generation. Libraries were constructed using TruSeq® Stranded mRNA Library Prep (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) according to manufacturer’s protocol using 200 ng of input RNA. Briefly, poly-A-containing mRNAs were captured using poly-T oligonucleotide-attached magnetic beads. Following purification, the mRNA was fragmented using divalent cations under elevated temperature. The cleaved RNA fragments were copied into first strand cDNA using reverse transcriptase and random primers. Strand specificity was achieved by replacing dTTP with dUTP in the Second Strand Marking Mix, followed by second-strand cDNA synthesis using DNA Polymerase I and RNase H. These cDNA fragments were then followed by A-tailing and adapter ligation reactions. The products were purified and enriched with PCR to create the final cDNA library. All libraries were quantified by Caliper and real-time qPCR and amplified on cBot to generate the clusters on the flowcell, and sequenced using HiSeq4000 (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) using paired end (100bp x2) sequencing to a sequencing depth of 40M reads (or 8G data). Sequencing data was generated over two batches (batch 1 86 samples and batch 2 80 samples, which include 22 additional samples from middle temporal gyrus and 1 additional sample from superior frontal gyrus that were excluded from the analysis in this report. All data generation was conducted by laboratory personnel blinded to the clinical phenotype.

2.2. Data analysis

Data were processed per sample using cutadapt (v1.13) (Martin, 2011), STAR (v2.5.3a) (Dobin et al., 2013). Transcript quantification was performed using RSEM (v1.3.0) (Li and Dewey, 2011) against all 26,000 genes in NCBI RefSeq database (version date; 2015-07-17). Surrogate variables are covariates constructed directly from high-dimensional mRNA-Seq data that could be used in subsequent analyses to adjust for unknown, unmodeled, or latent sources of noise. (Leek and Storey, 2007, 2008) We used the R package sva (v3.30.1) (Leek et al., 2019; Leek et al., 2012) to detect and estimate surrogate variables for unknown sources of variation to remove artifacts in the high-throughput experiments. Removing batch effects and using surrogate variables in differential expression analysis have been shown to reduce dependence, stabilize error rate estimates, and improve reproducibility (Leek et al., 2010). Differential gene expression analysis was performed using limma (Ritchie et al., 2015). The statistical model corrected the top five surrogate variables, gender, and diagnosis in a linear regression model to identify differentially expressed genes between AD cases and cognitively normal controls. Genes implicated in AD were sourced from DisGeNET (Pinero et al., 2017) (http://www.disgenet.org), one of the largest collections of genes and variants involved in human diseases that is based on data from expert curated repositories, GWAS catalogues, animal models and the scientific literature. Pre-generated differentially expressed genes from the ROSMAP (De Jager et al., 2018), MSBB (Wang et al., 2018) and Mayo Clinic (Allen et al., 2016) cohorts were downloaded from the AMP-AD Knowledge Portal and used for comparison of overlap at the gene set level via GSEA analysis first and then at the gene level to identified overlapped differentially expressed genes from this study and others from AMP-AD with a particular interest in the overlapping STG region from the MSBB study.

Among the transcripts consistently differentially expressed in the same brain region between this study and MSBB study, additional association with antemortem cognitive measure (last Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score) as well as neuropathological indices (both amyloid and neurofibril tangle burdens). For these models, samples from different brain regions were pooled and the statistical model corrected for the brain region in addition to the top five surrogate variables, gender using a linear regression model, while the main effect of interest was coded as a quantitative variable. Multiple testing was applied for the number of transcripts tested but not for the multiple phenotypes as the phenotypes were correlated.

2.3. Functional enrichment analysis

Differentially expressed genes (up- and down-regulated subsets) from the three AMP-AD studies were used to construct custom gene sets and used in a similar way as the c2.cp (a superset of c2.cp.biocarta, c2.cp.kegg, and c2.cp.reactome plus a few other data sources) (v7.0) subsets of MSigDB (Liberzon et al., 2011) or KEGG database for over-representation analysis (Boyle et al., 2004) and GSEA (Subramanian et al., 2005) using R package clusterProfiler (v 3.10.1) (Yu et al., 2012). Gene set enrichment analysis has the advantage of utilizing the entire distribution of genes tested in the differential gene expression analysis (in this study genes are ranked by t statistics for GSEA analysis), while over-representation tests enrichment using hypergeometric test and requires prefiltering for DEGs using preset thresholds (i.e. adjusted p < 0.05 and fold change≥1.2 or only requiring p < 0.05). Additionally, over-representation analysis was also performed using https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb/compute_overlaps.jsp which has a broader background gene set assumption and test over-representation at higher levels of the ontology hierarchy. Functional enrichment analyses were also performed for the downloaded DEGs from the STG in MSBB cohort using the same approach as above and the enriched gene sets from the STG in this study were compared with the enriched gene sets from the MSBB STG analysis.

2.4. Protein-protein interaction (PPI) network

The STRING database (Szklarczyk et al., 2015) (http://string-db.org) that provides a critical assessment and integration of protein-protein interactions, including both direct physical and indirect functional associations is used to assess a list of proteins encoded by genes (such as differentially expressed genes) have more interactions among themselves than what would be expected by chance for a random set of proteins of similar size, drawn from the genome. Such an enrichment indicates that the proteins are at least partially biologically connected and represents a meaningful set of proteins for a given biological contrast.

2.5. Tissue specificity enrichment analysis (TSEA)

Specificity index (SI) was used to identify and quantify tissue-specific and enriched mRNA across multiple tissues (Dougherty et al., 2010). Tissue specificity enrichment analysis was performed using the TSEA tool (http://genetics.wustl.edu/jdlab/tsea/).

2.6. Weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) analysis

For WGCNA analysis, a subset of genes with cpm > 10 in all samples was used. Consensus co-expressed gene modules were constructed across three brain regions using weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) (Langfelder and Horvath, 2008). The resulting gene modules were associated with multiple clinical phenotypes (such as Braak stage (Braak and Braak, 1991), plaque density, etc.) and genotype (APOE ε4). The hub gene, the gene in each module with the highest connectivity and may be functionally most critical within each module, was identified using choose TopHub In Each Module using WGCNA R package. Over-representation analysis for member genes within each module was performed in the same way as for the full dataset.

A schematic diagram illustrating the overall experiment and analytic approach is shown in Supplemental Fig. 1.

3. Results

3.1. Sample characteristics

A total of 143 samples from two BAs were analyzed in the mRNA-Seq experiment. Each frozen sample was labelled with brain region, clinical diagnosis status, and with the linked donor identifier. Two samples with discrepant phenotype linked to the subject ID were excluded from the analysis. The age at death, gender, PMI, and APOE genotype and additional clinical characteristics are described in Table 1. Overlapping donors for remaining 141 samples is also available in Supplemental Fig. 2. The clinical diagnosis status was used as the case status phenotype for this study, which was largely consistent with Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) score (Mirra et al., 1991), a semiquantitative measure of neuritic plaques where a neuropathologic diagnosis was made of not AD, possible AD, probable AD, or definite AD based on semi quantitative estimates of neuritic plaque density as recommended by the CERAD. A CERAD neuropathologic diagnosis of AD required moderate (probable AD) or frequent neuritic plaques (definite AD) in one or more neocortical regions. The case status was also consistent with the National Institute on Aging and the Reagan Institute (NIA-Regan) AD criteria (Hyman and Trojanowski, 1997).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the samples used in the mRNA-Seq assay.

| Brain region |

STG |

IFG |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical diagnosis |

Cognitively Normal |

Mild Cognitive Impairment |

Alzheimer’s Disease |

Cognitively Normal |

Mild Cognitive Impairment |

Alzheimer’s Disease |

| Sample size | N = 38 | N = 14 | N = 24 | N = 23 | N = 9 | N = 33 |

| Age at death, Mean (standard deviation) | 79.97 (7.26) | 84.79 (5.67) | 86.79 (6.53) | 80.52 (7.46) | 83.67 (6.38) | 85.58 (6.93) |

| Gender, Female n (%) | 11 (28.9) | 7 (50) | 11 (45.8) | 6 (26.1) | 4 (44.4) | 21 (63.6) |

| PMI | 3.28 (2.43) | 3.09 (0.80) | 3.38 (2.42) | 3.14 (1.75) | 3.22 (0.92) | 3.06 (2.00) |

| Plaque Totala | 4.61 (5.29) | 5.14 (5.97) | 12.37 (2.74) | 5.52 (5.70) | 6.61 (5.95) | 12.66 (2.69) |

| Tangle Totalb | 3.63 (2.60) | 5.16 (2.80) | 9.93 (4.03) | 3.73 (2.27) | 5.17 (2.95) | 10.13 (4.02) |

| Last MMSE test score | 28.19 (1.54) | 26.92 (2.02) | 17.57 (7.26) | 28.14 (1.10) | 27.00 (2.00) | 16.85 (6.69) |

| NIA-Reagan criteria (Hyman and Trojanowski, 1997), n | ||||||

| Criteria not met | 37 | 12 | 23 | 8 | ||

| Not AD | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Low | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Intermediate | 1 | 11 | 17 | |||

| High | 12 | 15 | ||||

| Semiquantitative measure of neuritic plaques CERAD score (Mirra et al., 1991), n | ||||||

| Criteria not met | 5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Not AD | 24 | 5 | 13 | 4 | ||

| Possible AD | 9 | 6 | 8 | 4 | 1 | |

| Probable AD | 7 | 7 | ||||

| Definite AD | 17 | 25 | ||||

| Plaque densityc | ||||||

| Zero | 17 | 7 | 9 | 3 | ||

| Sparse | 11 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 1 | |

| Moderate | 5 | 1 | 7 | 5 | 0 | 7 |

| Frequent | 5 | 5 | 17 | 4 | 4 | 25 |

| Braak staged | ||||||

| I | 9 | 2 | 4 | 1 | ||

| II | 9 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 2 | 1 |

| III | 13 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| IV | 7 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 13 |

| V | 8 | 8 | ||||

| VI | 4 | 7 | ||||

| APOE genotype, n | ||||||

| ε2/ε2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| ε2/ε3 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| ε3/ε3 | 23 | 7 | 9 | 13 | 4 | 18 |

| ε3/ε4 | 9 | 3 | 8 | 6 | 3 | 9 |

| ε2/ε4 | 1 | 0 | 3 | |||

| ε4/ε4 | 0 | 0 | 3 | |||

STG: superior temporal gyrus (BA22); IFG: inferior frontal gyrus (BA44); MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination; CERAD (Mirra et al., 1991): Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease.

Plaque F, T, P, H and E for senile plaque density score in standard regions of the frontal, temporal and parietal lobes, hippocampal CA1 region and entorhinal/trans-entorhinal region was obtained. All plaque types (neuritic, cored, diffuse) were included. Plaque total is the arithmetic sum of scores from Plaque F, T, P, H and E above.

Tangle F, T, P, H and E is for neurofibrillary tangle density score in standard regions of the frontal, temporal and parietal lobes, hippocampal CA1 region and entorhinal/trans-entorhinal region. Tangle total is the arithmetic sum of scores from Tangle F, T, P, H and E above.

Plaque density is the CERAD neuritic and/or cored plaque density (Mirra et al., 1991) defined using the CERAD templates as none, sparse, moderate and frequent. The value listed represents the highest density score seen in any of the three evaluated cerebral neocortex regions (frontal, temporal and parietal). However, if frequent neuritic or cored plaques are a rare finding, the score may be adjusted downwards to reflect this.

Braak stage is the Braak neurofibrillary stage (0-VI) as defined originally by Braak and Braak (1991). Thick 40–80 μm sections stained with Gallyas, Campbell-Switzer and thioflavine S stains are used to obtain this.

3.2. Identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs)

Among the 26,000 genes quantified, 16,636 genes had count per million reads (cpm) greater than 0.25 in at least 50% of the samples and were carried forward for differential gene expression analysis. The number of DEGs for each comparison is listed in Supplemental Table 1 whereas AD vs. CN is the main comparison and MCI vs. CN is a secondary comparison as the study sample sizes for MCI condition are limited, which limits the power of DEG identification for the MCI vs CN contrast. Several hundred mRNAs were differentially expressed between AD cases and cognitively normal controls in the STG, while no and few transcripts met the same criteria (adjusted p less than 0.05 and fold change greater than 1.2) in the IFG, consistent with the limited atrophy and pathology observed in this brain area in AD patients. The full list of DEGs with adjusted p-value less than 0.05 and fold change greater than 1.2 is listed in Supplemental Table 2.

3.3. Functional enrichment analysis

Among the 115 KEGG gene sets (Supplemental Table 3) with enrichment q-value less than 0.05 in the GSEA analysis using the STG differential gene expression analysis results (AD vs. CN), a dozen of them were immune-related gene sets including antigen processing and presentation (p = 0.002, q-value = 0.01), chemokine signaling pathway (p = 0.003, q-value = 0.01), and complement and coagulation cascades (p = 0.004, q-value = 0.01). Other gene sets of interest include mTOR signaling pathway (p = 0.001, q-value = 0.01), autophagy (p = 0.001, q-value = 0.01), proteasome (p = 0.002, q-value = 0.01), oxidative phosphorylation (p = 0.003, q-value = 0.01), Wnt signaling pathway (p = 0.003, q-value = 0.01), and cholinergic synapse (p = 0.003, q-value = 0.01). No gene sets passed this threshold from the IFG analysis.

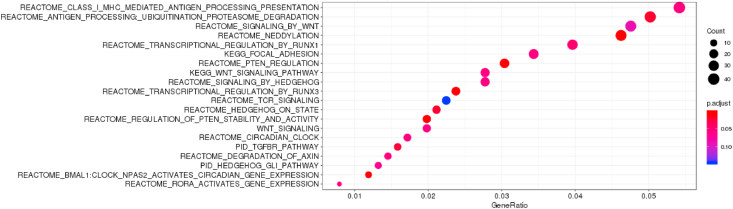

Over-representation analysis on the other hand identified over-representation of PTEN regulation (p = 2.22 × 10−5, q-value = 0.003) and regulation of PTEN stability and activity (p = 2.52 × 10−5, q-value = 0.01), Wnt signaling pathway (p = 0.0006, q-value = 0.05) among the genes differentially expressed between AD vs. CN (with adjusted p≤0.05) in the STG (Supplemental Table 4, Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Over-representation analysis for DEGs in the STG (adjusted p < 0.05). GeneRatio is k/n where k (also known as count) is the size of the overlap of the list of genes differentially expressed in AD compared to CN in the STG with adjusted p < 0.05′ with the specific gene set (e.g. REACTOME_SIGNALING_BY_WNT). In another word, k is the number of genes within that list n, which are annotated to the term. n is the size of the overlap of ‘a vector of input gene ID’ with all the members of the collection of gene sets (e.g. the C2 canonical pathway collection of MSigDB) and is the size of the list of genes of interest. Only unique genes are counted in both cases. The dots are color coded by adjusted p-value and size by count. This analysis corresponded to the table in the Supplemental Table 4A. Over-representation analysis was performed using the R package clusterProfiler. The top 20 enriched terms are plotted. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

3.4. PPI enrichment

PPI network construction using differentially expressed genes with adjusted p≤0.05 and fold change≥1.2 suggested that both PPI networks have significantly more interactions than expected (PPI enrichment p-values of 4.21 × 10−7, Supplemental Fig. 3 for the STG), suggesting the DEG analysis identified a biologically meaningful subsets of genes (from the genome).

3.5. Tissue-specific expression analysis

TSEA suggested that at least a subset of differentially expressed genes in the STG (adjusted p≤0.05 and fold change≥1.2) exhibited relative brain (Fisher’s Exact p-value = 0.002, Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) corrected p-value = 0.038) or nerve (Fisher’s Exact p-value = 0.003, BH corrected p-value = 0.038) specificity (Supplemental Fig. 4). Genes with brain-specificity (at pSI threshold 0.05) include APOC1, TREM2, OLR1, CXXC4, and WNT7A, while the full list is available as a footnote in Supplemental Fig. 4.

3.6. WGCNA analysis

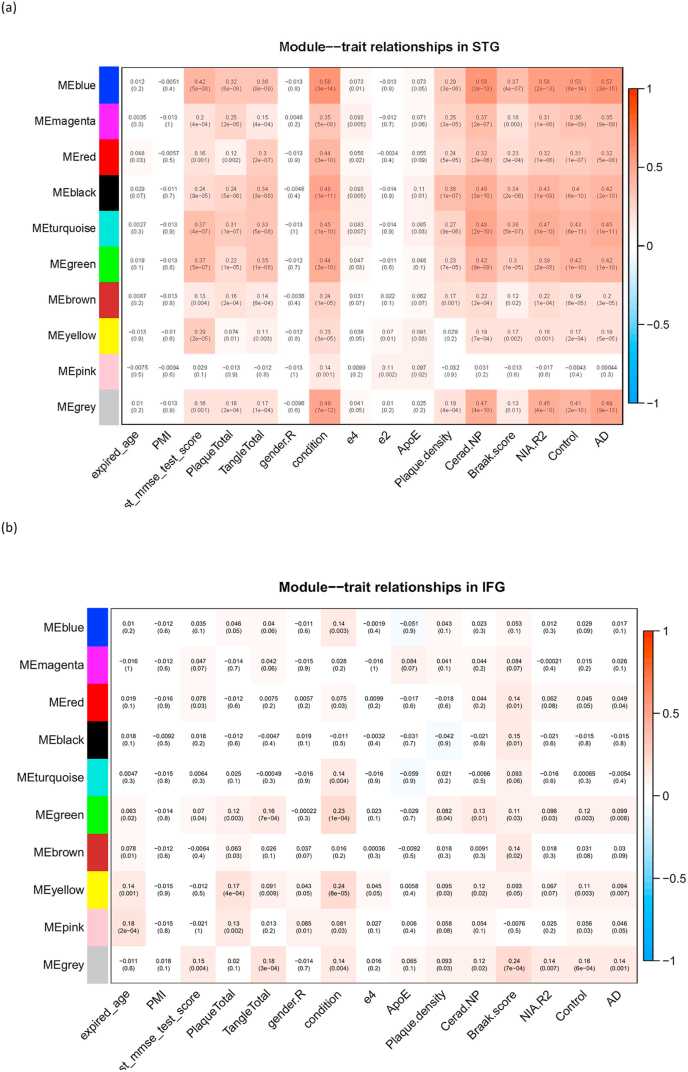

A total of 5772 genes were used in WGCNA analysis. Nine consensus modules were constructed based on the expression data from the two BAs. Many of these modules (represented by eigengenes) were associated with additional traits of interest to AD, such as amyloid plaque and neurofibril tangle density, and last MMSE score (prior to death) (Fig. 2). The association between co-expression modules and traits of interest in the STG is stronger than association in the IFG (with comparable sample size). The hub genes identified for the STG are FYTTD1 for the black module, lysine acetyltransferase 8 (KAT8) for the blue module, KIFC2 for the brown module, PTP4A1 for the green module, CDK5RAP3 for the magenta module (Supplemental Fig. 5A), ARHGDIA for the pink module, SRP9 for the red module, F-box and WD repeat domain containing 11 (FBXW11) for the turquoise module, and synaptotagmin like 2 (SYTL2) for the yellow module (Supplemental Fig. 5B), respectively. Among these hub genes, FBXW11 (p = 2.95 × 10−5, adjusted p-value = 0.003), CDK5RAP3 (p = 0.0002, adjusted p-value = 0.01), KAT8 (p = 0.0008, adjusted p-value = 0.02), and SYTL2 (p = 0.001, adjusted p-value = 0.03) were differentially expressed between AD and cognitively normal controls. Members of the magenta module were enriched in negative regulation of autophagy (gene set enrichment p = 0.03) as driven by SCFD1 (p = 0.02 comparing AD vs. controls) and WDR6 (p = 0.07). Members of the turquoise module were enriched with genes involved in Golgi vesicle transport (p = 0.0007) and blood vessel morphogenesis (p = 2.36 × 10−5). The red module was also enriched with genes involved in regulation of protein ubiquitination (p = 0.001). Eigengenes of the magenta, turquoise, and red modules were associated with a quantitative measurement of total plaque and total tangle load (Fig. 2). The hub gene for the blue module KAT8 encodes a member of the MYST histone acetylase protein family and was recently implicated as a genome wide association significant locus in UK Biobank cohort using parental history of Alzheimer’s dementia as a surrogate (Marioni et al., 2018). Members of the blue module were enriched for genes involved in mitochondria function and oxidative phosphorylation (p = 3.45 × 10−6 for gene set enrichment in oxidative phosphorylation). The members of the yellow module were enriched in genes playing a role in synaptic signaling (p = 0.0001), while members of the brown module were enriched in genes playing a role in regulation of synaptic plasticity (p = 9.38 × 10−11).

Fig. 2.

WGCNA module-trait relationship in the (a) STG (b) IFG. The eigengene of the respective co-expression module was associated with an array of AD phenotypes and clinical factors. Correlation coefficient (with p-value inside parenthesis) was displayed in each square, where the eigengene of a given co-expression module is defined as the first principal component of the standardized expression profiles.

3.7. Overlap with findings from AMP-AD

For the up- and down-regulated genes in the AMP-AD initiative, eight out of twelve gene sets derived from AMP-AD analyses were enriched (q-value < 0.1) in the STG differential gene expression analysis results with consistent direction (e.g. a positive NES is associated with an up-regulated gene list from AMP-AD analysis) except three sets from the Mayo Clinic cohort and one from MSBB cohort (Table 2), suggesting that there is largely consistent finding at the gene list level between this study and the AMP-AD studies despite different brain regions that were used. Similar observation was noted for the IFG differential gene expression analysis results especially with respect the enrichment of gene sets up and down-regulated in the DLPFC from ROSMAP, up-/down-regulated in the IFG, up-regulated in the STG, down-regulated in the FP from MSBB cohort.

Table 2.

Gene set enrichment analysis of differential gene expression analysis results against gene sets derived from AMP-AD.

| Description | Set Size | Enrichment Score | NES | pvalue | p.adjust | Q values | rank | leading_edge | core_enrichment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STG | |||||||||

| AMP-AD_CTX_up | 1507 | −0.24 | −1.35 | 1.19E-03 | 8.01E-03 | 3.01E-03 | 3537 | tags = 29%, list = 25%, signal = 24% | AQP1/ZNF366/VANGL1/OSMR/CACHD1/CLIC4/LPP/TRIM14/MDFIC/KDM1B/PAPOLA/RNF144B/FAM129A/SLC7A2/PPP1R3C/CP/GAS2L1/GIMAP1/MRVI1/TBL1X/IL4R/CD302/SYNM/MYO10/BIRC3/AMOT/P2RY2/ATP1A2/STAT3/ABHD15/ITPR2/WEE1/INHBB/PHKA1/DKK3/ITPKB/PERP/CDH5/FGFR1/ARHGEF26/MTSS1L/RASSF8/SLC7A11/GPR4/ARL6IP6/FREM2/ZIC3/PLEC/LRP1B/GRAMD1C/SRGAP1/ID4/MAPRE1/VSTM4/RRAS/PLXNB1/HIST1H2AC/CR1/ANGPT2/LATS2/BMPR1B/CLDN5/SOX6/PLIN2/UHRF1/DLC1/CBX2/FOXO1/P2RY14/CDH20/LAMC1/SOX2/EMCN/GRTP1/OMD/CERS1/TIMP3/RANBP3L/SLC25A20/TMBIM1/KCNN3/ARHGAP42/ERBB2/DTNA/ENG/ADH1B/TLCD2/GPRC5B/SNX7/FAM167B/LONRF3/EMP2/LEPR/HERC2P3/CTGF/PALLD/CFH/CD81/CHST3/IGSF11/GNG5/PDGFC/MTM1/SMAD9/SULT1C4/PTBP1/TMED10/GPR146/FZD1/ADAM12/C2orf40/RYR3/EGFR/PGM2/SLC1A3/IL17RB/TBX2/FLT4/CD59/KCTD12/PRKG1/PGF/HEYL/SHE/SLC39A11/CHDH/MYO1C/MT3/SLC9A9/BCL2/CASZ1/TLN1/AHCYL2/IFITM3/PARP14/PRDM5/SPON1/LPIN3/ADRB2/KLF6/ABHD4/FAM84B/HRH1/MID1IP1/PLIN1/PPP1R13L/ANPEP/TMED5/TPD52L1/SDC4/PDE4B/PDLIM5/SOX9/IL18R1/ITGB1/PTPN13/ZIC1/GJB2/AZGP1/SOX17/TRIP6/SUN2/FGD6/ZBTB33/KCNE3/ITPR3/ABCA1/ITGAV/ZIC5/DCAF12/PITPNC1/UNG/TLE1/NHSL1/GNA12/GPT2/SEC14L1/ACVRL1/ZC3H12C/FKBP5/TRAM1/SNX33/RHOJ/FGD5/CD109/RAB23/BCAR3/KIF26A/TBX3/ERLIN2/ALDH1L1/ABCG2/LPAR3/MKLN1/FAM107A/ADCY2/SLC2A4/FAT4/ABCC9/EDNRB/PREX1/STARD8/ST6GALNAC3/SALL1/NBPF10/GABRG1/STK32A/PLSCR4/MFHAS1/MATN3/FAT1/TRPM3/MKNK2/HHEX/DDR2/ALPL/GPC5/NOTCH4/LAMA5/PBXIP1/IGFBP7/SP1/ZNRF3/CLEC14A/HEPH/S100A8/CYBRD1/CGNL1/PODN/PTH1R/GPR75/GNA13/FZD9/DGKG/CDC42EP4/CD34/FLNA/KRT19/ACSBG1/ZNF516/PLEKHA7/PIK3CA/NOTCH2/IRAK3/CTDSPL/NTRK2/GYG1/TLR4/HEG1/AHCYL1/CALCRL/LGR4/MYBPC1/EHHADH/MAGT1/USP53/SLC19A3/ZC3HAV1/NID1/ZBED6/VEZF1/RAB31/EMX2OS/CPNE3/FERMT2/ITGA6/LEF1/SH3GLB1/CTDSP2/MGST1/LRP5/PRKD3/RREB1/APPL2/YES1/CREB3L2/KANK3/LIX1L/PAPLN/METTL7A/CYYR1/ABLIM1/FYCO1/GMNN/ATP13A4/B3GAT2/LRRC8A/PRDM16/ARHGAP29/ACSS3/CDC14A/MERTK/S100A9/TMEM204/GPAM/KDELC2/PON2/FUT9/SOD3/GJA1/SOX5/TEP1/SFT2D2/PAPSS2/RBMS2/SALL3/ECE1/CLEC4E/HSDL2/PODXL/PRKCA/PEX11A/TP53BP2/FAM198B/STOM/SMAD6/SLC2A1/HEPACAM/PEAR1/GJB6/STAG2/ADD3/IMPA2/ELOVL7/CALD1/CPT1A/KLF3/EPHX1/TIE1/NOTCH3/UTRN/QKI/TMOD3/ACSL5/SASH1/AQP9/DOCK6/GPRC5C/GPM6B/CDA/MLEC/REST/ATOH8/OPHN1/SMAD5/ITGB4/PLIN3/EDA/TAB2/MR1/NACC2/EPHB4/CRYBG3/GLI3/APCDD1/KIF5B/ASPH/YAP1/NQO1/PTAR1/AK3/AKAP13/KLF15/ARHGAP5/GGT5/TGFBR3/HIF3A/TRPS1/PTPRB/ADIPOR2/FIGN/MFAP3/ARHGAP31/LIFR/TCF12/SLC40A1/MECOM/MEGF10/SLC30A1/HVCN1/DAG1/PRKX/GATA2/PLEKHG1/ZNF81/ROCK1/RHOBTB3/ARAP2/AFF1/SAMHD1/TINAGL1/RXRA/FAM129B/DCHS1/TBC1D14/BCAM/EPS8/MAOA/HMBOX1/TXNIP/TEAD1/PPARA/THSD4/LRP10/OGFRL1/GABRB1/ITGB8/PARD3/TMTC1/HEATR5A/VWF/ATP10A/ITGA1/LRP4/AHNAK/PDK4/EIF4EBP2/IKZF2/FNDC3B/ZIC2/SLC14A1/HSPG2/KANK1/ZFHX3/TNS1/PREX2/EPAS1/WASF2/NEO1 |

| AMP-AD_CBE_up | 849 | −0.24 | −1.33 | 1.28E-03 | 8.01E-03 | 3.01E-03 | 3518 | tags = 29%, list = 25%, signal = 23% | OSMR/ZNF670/CLIC4/PANK1/SYT14/GLUD2/AOC2/SSTR2/AMIGO2/CP/SOS1-IT1/POLR2A/IL4R/FSTL5/RNF169/SLC12A2/BIRC3/PGM2L1/DDX21/KCNK2/PHF3/HSPA8/ARHGAP20/CLVS2/HECA/OPCML/SORT1/NOMO3/FBXO11/GPR4/TCAP/UPF2/MCM8/HIST1H2AC/ANGPT2/SMC4/LATS2/ECT2/RRAGD/FAN1/F2R/HSP90AB1/HSPA1L/REL/ZNF510/GAP43/CALN1/RANBP3L/KIAA1109/NELL1/ARHGAP42/CLPB/EDIL3/FAM167B/LONRF3/SMAP1/C1orf115/CTGF/CFH/PARVA/HIST2H2BF/GUSBP4/CHST3/CDH18/CCDC144A/RAP1GAP2/FUT10/HIST2H2BE/ERV3-1/ATF6/DNAJB4/MED1/LCA5/ACTR8/TBX2/ZNF550/SPHKAP/KCTD12/FRMPD2/DNAJC6/SH3BP5/SERINC1/SHPRH/OLFML2B/IFITM3/KCNH7/SPON1/ASAP2/ADRB2/KIF3C/HRH1/MID1IP1/UHRF1BP1L/DPY19L2P2/ANPEP/TMED5/OTUD1/ANKRD6/SYNE1/ENGASE/CNTNAP5/HYOU1/PRKCE/ZBTB33/KCNE3/ITPR3/GLRA2/PTPN4/APC/NFAT5/ACVRL1/KCND3/NAA35/CRISPLD2/FKBP5/FGD5/RAB23/MKLN1/EPHA5/DNAJA1/COL19A1/RASA1/PPP1R15B/ZBTB11/STARD8/LTN1/MAFG/HSPA13/RANBP6/PIK3CD/IGFBP7/CLEC14A/UBE4A/S100A8/SYTL5/ADCY7/PLCL2/ZNF845/SV2B/FLNA/NRIP1/PIK3CA/UNC13C/NPTX2/TMEM56/TLR4/RBM12B/ZNF138/DOK6/ZBED6/USP32/ZNF12/ZDBF2/ZNF721/RPL23AP7/TCF20/RAB3C/GALNT2/OXR1/NUAK1/IL1RAPL1/FILIP1L/ZNF420/LONRF2/NPTXR/S100A9/TXNRD1/GTF2I/FUT9/RBBP5/RGS7BP/KCNB1/TCP11L1/HTR1A/PURA/AKAP9/ZNF318/ZHX1/C1QL3/CRNKL1/SMAD6/GOLGB1/CNOT1/GNL3L/CENPF/PEAR1/CANT1/IMPA2/C9orf129/TBC1D9/ZRANB1/ACSL5/AKAP12/AQP9/WDR86/CDA/ZNF503/KLHL11/BMPR2/ATRX/EPHB4/CRYBG3/FBXL14/PTAR1/TRAPPC10/OLFM3/ALG11/TGFBR3/FAM169A/MFAP3/PPM1L/AIDA/ZNF808/ZNF354C/HSPA4/FOXO3B/INCENP/ZXDA/GTF3C4/PSAP/KLF11/ZNF483/KCNJ12/ZNF81/TINAGL1/TBC1D14/PDZD8/CCDC144B/CYP7B1/SLC2A12/EXOC8/DIXDC1/KLHL9/RNF111/GABRB1/TMTC1/KIF2A/TRIM23/SSTR1/TMCC1/HSPG2/SMCR8/ZBTB16/PLEKHM3 |

| AMP-AD_IFG_up | 24 | 0.70 | 2.37 | 2.10E-03 | 8.01E-03 | 3.01E-03 | 2617 | tags = 67%, list = 18%, signal = 55% | OLR1/CDK2AP1/ADAMTS2/HOMER3/KLHL6/NWD1/SLC15A3/COL27A1/CD84/HPSE/PSD2/MMP2/APLN/SYTL3/SLC6A12/NES |

| AMP-AD_DLPFC_up | 70 | 0.58 | 2.48 | 2.29E-03 | 8.01E-03 | 3.01E-03 | 2189 | tags = 46%, list = 15%, signal = 39% | COL5A3/PFKP/ADAMTS2/S100A4/NRIP2/SPP1/SLC4A11/LSP1/RRAD/CXCR4/HSD11B2/EMP3/AQP6/CA2/NEFH/NPNT/NWD1/COL27A1/SLC5A11/QDPR/GIPR/SLC6A9/UGT8/SFRP2/PHYHD1/APLN/ISYNA1/FANCC/HSPA2/HIC1/CLCA4/MT1F |

| AMP-AD_IFG_down | 35 | −0.51 | −1.84 | 3.66E-03 | 8.74E-03 | 3.29E-03 | 5500 | tags = 83%, list = 39%, signal = 51% | SPRED3/BDNF/WNT10B/SH2D5/SCN5A/SPON2/TCERG1L/SST/GRASP/ADCYAP1/MLIP/CCBE1/GUSBP5/PPEF1/VGF/RNF165/WISP2/OTOGL/ZDHHC23/IL12RB2/NPTX2/LY86-AS1/IQGAP3/SLIT1/NPTXR/CYP26B1/C2CD4C/MEIS3 |

| AMP-AD_CBE_down | 621 | 0.31 | 1.76 | 3.75E-03 | 8.74E-03 | 3.29E-03 | 3775 | tags = 35%, list = 27%, signal = 27% | CEP95/INO80C/THBS3/U2AF1/SNRNP35/LMF1/DPY19L2/NASP/CRYGS/KLKB1/CCDC57/IFT43/ZNF133/CCDC84/CDK5RAP3/OSGEP/COMMD3/AMY2B/TTC31/SPAG8/ABHD11/MSTO1/LUC7L/PCBP4/ADAMTS2/SLC38A6/OXA1L/CCDC58/SCNN1D/SCLT1/COL11A2/ENO3/COQ3/TTC21A/CRIP3/C1orf123/GPT/FER1L4/FUS/HKR1/THOC1/LPXN/AGAP6/IL11RA/TEKT3/LY6G5B/UPP1/ITPA/BEAN1/AMT/ZCWPW1/TNNI3K/CLEC2D/LRRC20/SLC35A1/SLC10A4/ZNF691/MYO19/MPV17/GSTA4/DGKA/COL28A1/RIN1/PIGZ/TPCN2/PMF1/WDR78/TRIM7/POLR3G/NME5/LAMA4/SH2D6/NSMAF/TRANK1/DNM1P35/PDZD7/DYNC2LI1/SEMA5B/QTRT1/PNMA3/MTBP/UBXN11/PDE7A/MYH3/TIMM9/IFT122/COQ4/EZH2/SNHG1/ADPGK/THPO/DPY19L2P1/TTC17/ADAMTS14/PLA2G5/WDR54/SLC25A29/NMRAL1/FCHSD1/GLYCTK/NIPAL4/USP43/KCNIP1/TARBP1/TRPT1/PMFBP1/ADCK1/FREM1/EGR4/DNAH2/CCS/LXN/ICA1/ANAPC7/CBY1/BZW2/LAMB1/CA3/N4BP2L1/CERCAM/LRRC37A3/MEI1/COMMD4/FBXO15/CARNS1/AK8/SYCP2L/EPN3/SRP19/TAF7L/LRRFIP2/RCOR2/DYNLRB2/NEAT1/TRMT11/CEP164/KIAA0895L/NT5M/ANKRD13A/MIAT/FAM76A/HGSNAT/C4orf33/CRIPAK/SLC25A13/CSDC2/ARTN/EXD3/FARSB/WSB1/PARP2/TMC7/CATSPER2/TDG/BTBD17/SAMD10/RNFT1/GSTZ1/C16orf74/ECHDC2/LINGO2/MORN3/SFI1/PLEKHH1/SCMH1/ALG6/RYR1/DBF4B/GOLGA8B/MED4/ABHD14B/KLHDC9/CKMT1B/CPNE6/PARD6B/BCL2L15/ZNF300/CTDSP1/PRCD/HR/C12orf45/EFNA5/KCNH8/HFM1/DCLK1/ABCA10/ZNF18/TMEM175/ANKDD1A/GLIPR2/SNX22/GRK4/RFESD/IFITM10/NEK3/METTL23/NRSN2/ST3GAL3/CLK4/ADSSL1/SCRT1/ACP2/MAGEL2/AGBL4/SLC38A7/GSS/SLC25A45/RASSF7/MAEL/FAM86B1/ALOX12P2/INHA/ELMO1/DCAF8/CBWD3/HPN/TMEM151A/STAC2 |

| AMP-AD_PHG_up | 838 | −0.23 | −1.28 | 5.15E-03 | 1.03E-02 | 3.87E-03 | 3576 | tags = 30%, list = 25%, signal = 24% | GNG12/ID3/AQP1/ZNF366/VANGL1/OSMR/FMNL2/CLIC4/LPP/MDFIC/SLC7A2/CASP10/MRVI1/TBL1X/PMP22/MYO10/TSC22D4/AMOT/CDKN2B/TULP3/ATP1A2/STAT3/WEE1/DAAM2/PLEKHB1/INHBB/PHKA1/C10orf105/VANGL2/PI16/DOCK1/STAT5A/ITPKB/ARHGEF26/ACSM5/MTSS1L/RASSF8/SLC7A11/ARL6IP6/NFATC1/TCAP/PLEC/EYA1/ID4/AGTRAP/PLXNB1/CR1/LATS2/BMPR1B/MTUS1/FOXO1/SPATA13/CDH20/SOX2/CERS1/TIMP3/RANBP3L/TMBIM1/ARHGAP42/ERBB2/DTNA/TLCD2/GPRC5B/KDR/FGF1/LONRF3/EMP2/PALLD/CHST3/PLA2G16/SMAD9/SULT1C4/CBFB/PHF21B/HIST2H2BE/RYR3/VRK2/IL17RB/BCYRN1/TBX2/FRMPD2/ABCA8/ARL17A/KIF1C/PGF/AASS/CHDH/SLC9A9/PAQR8/TLN1/LLGL1/PARP14/ADRB2/S100B/ABHD4/FAM84B/MID1IP1/PLIN1/PPP1R13L/TPD52L1/SDC4/PDLIM5/SOX9/ITGB1/PTPN13/ZIC1/TRIP6/KCNE3/ZHX2/ABCA1/ZIC5/ARHGEF37/NHSL1/JUP/GNA12/GPT2/ZC3H12C/COL18A1/SNX33/CD109/BCAR3/ALDH1L1/MAN2A1/FAM107A/SERINC5/FAT4/ABCC9/PREX1/HEY2/SALL1/GABRG1/STK32A/PLSCR4/FAT1/DDR2/PBXIP1/IGFBP7/FAM114A1/HEPH/CYBRD1/CGNL1/PODN/GPR75/DST/LTBP3/MYOM1/CDC42EP4/FLNA/PLEKHA7/ARRDC4/NOTCH2/ZBTB20/TLR4/HEG1/AHCYL1/HIP1/ZC3HAV1/ZBED6/VEZF1/EMX2OS/RDX/ITGA6/LEF1/CTDSP2/SCRIB/MGST1/LRP5/RREB1/ZCCHC24/YES1/RPL23AP7/TANC1/LIX1L/PAPLN/METTL7A/CYYR1/ABLIM1/FYCO1/SMAD4/ZIC4/ACSS3/CDC14A/ACACB/GJA1/TEP1/SFT2D2/TP53INP1/EML3/PDCD4/PEX11A/KCNJ2/STOM/HEPACAM/PEAR1/ADD3/KAT2B/KLF3/EPHX1/UTRN/QKI/SASH1/REST/ATOH8/HIPK2/ITGB4/PLIN3/NACC2/CRYBG3/KIF5B/YAP1/KLF15/TGFBR3/HIF3A/TRPS1/ARHGAP31/TCF12/SLC40A1/NET1/MEGF10/SLC30A1/ANKRD40/HVCN1/DOCK5/NPAS3/PRKX/GATA2/SLC44A2/STON2/OTUD7B/RXRA/FAM129B/EPS8/HMBOX1/TXNIP/TEAD1/PPARA/LRP10/OGFRL1/BBX/ITGB8/PARD3/LRP4/AHNAK/PDK4/NDRG1/ZIC2/SLC14A1/NOTCH1/ZFHX3/TNS1/WASF2/ZFHX4/NEO1/TRIM56 |

| AMP-AD_FP_down | 24 | −0.51 | −1.65 | 9.52E-03 | 1.67E-02 | 6.27E-03 | 2849 | tags = 42%, list = 20%, signal = 33% | VGF/HBB/ALDH1A1/HES4/NPTX2/SMAD6/HBA2/LPL/MEIS3 |

| AMP-AD_STG_up | 141 | 0.28 | 1.36 | 3.57E-02 | 5.56E-02 | 2.09E-02 | 3363 | tags = 30%, list = 24%, signal = 24% | CD74/OLR1/ITGAX/TREM2/CDK2AP1/HLA-DRA/C3AR1/GEM/CD86/ANGPT1/AEBP1/TYROBP/TP53I3/KLHL6/NPNT/NWD1/SLC15A3/FCGR2A/LGALS9/CD84/HPSE/ITGB2/ITGAL/IL10RA/ARHGAP15/ZNF580/SIRPB2/FXYD5/MS4A7/SYTL3/RASSF3/PIK3R5/IFIH1/SAMSN1/NES/CD4/CD37/SELPLG/CYBB/LIPG/GFAP/GPSM3/LAPTM5 |

| AMP-AD_DLPFC_down | 55 | −0.34 | −1.33 | 7.24E-02 | 1.01E-01 | 3.81E-02 | 4297 | tags = 44%, list = 30%, signal = 31% | ADCYAP1/TRIM45/FREM3/CHML/PRSS35/HMGN2/PPEF1/VGF/PRTN3/ALDH1A1/FRMPD2/PALMD/MPO/PNMA5/ZNF334/MATN3/MDK/SLC30A3/IQGAP3/WDR86/PPDPF/MEIS3/TET1 |

| AMP-AD_PHG_down | 479 | −0.22 | −1.15 | 1.10E-01 | 1.41E-01 | 5.29E-02 | 3629 | tags = 27%, list = 25%, signal = 21% | NRSN1/INSM2/NEUROD6/RXFP1/DIRAS1/TMEM155/MACROD2/GLUD2/NKD2/MLIP/STX1A/CYP4X1/BMPER/KIF12/SORCS1/CPLX1/CDK5R2/KCNJ4/FAM19A1/CYP2C8/MAL2/VWA5B2/DNAL4/CCKBR/MPPED1/C2orf16/GAP43/CARTPT/NELL1/SLC6A17/DOC2A/GPR158/ITFG1/PPEF1/TRPC5/VGF/RPH3A/SLC45A1/DACH2/NRN1/RNF165/KCNK10/SPHKAP/DRD5/HECW1/CYP26A1/GPRASP2/ORC6/KIF17/SCG3/MPPED2/PRKCE/KCNB2/RTBDN/TRHDE/SYT1/EPHA5/RAB3B/KCNF1/RASL11B/COL19A1/GABRG3/OTOGL/UNC13A/ETV1/ELAVL4/SVOP/FAM102B/OSBPL10/RBP4/ST6GALNAC5/HES4/GABRA1/HOPX/KRT17/FRMPD4/SV2B/ZDHHC23/IL12RB2/UNC13C/NPTX2/DLGAP1/WNT7B/SLC30A3/HTR2A/LY86-AS1/IQGAP3/RAPGEF4/CHST8/CREB3L1/KCNV1/FBXW7/DIRAS2/FAM162B/PTK2B/UNC5D/NUAK1/ANO3/RGS4/TPX2/CCDC68/CYP26B1/SLC22A18/KCNB1/PLCB1/C1QL3/SLC39A10/RAB27B/GDA/CTXN3/LSM11/GRM8/FXYD7/OLFM3/RPLP0P2/LPL/HUNK/DGKI/SYTL2/KCNQ3/MEIS3/IPCEF1/CCDC144B/CREG2/TRIM36/PART1/MUM1L1 |

| AMP-AD_FP_up | 15 | 0.44 | 1.31 | 1.41E-01 | 1.65E-01 | 6.19E-02 | 4648 | tags = 53%, list = 33%, signal = 36% | ADAMTS2/NRIP2/CALB2/IGFBP5/PRELP/MRPS6/ELK1/ZDHHC22 |

| AMP-AD_CTX_down | 968 | −0.16 | −0.86 | 9.54E-01 | 9.81E-01 | 3.69E-01 | 2987 | tags = 20%, list = 21%, signal = 17% | GAP43/CALN1/TRPC1/KCNAB1/NELL1/SLC6A17/DOC2A/GPR158/CNGB1/ITFG1/PPEF1/MSC/GNB5/RBM26-AS1/VGF/CAMK1D/CDH18/KSR2/HTR7P1/EFR3B/YWHAG/CCDC144A/TSNAX/A1BG/RASGRF2/RPH3A/PHF7/TOMM20/SYCE1/NRN1/RNF165/ACSL4/SPHKAP/FRMPD2/HECW1/DNAJC6/GPRASP2/DMXL2/TNFRSF11A/SLITRK3/STMN2/GNG4/ORC6/EPHA4/SPNS1/KIF17/KLHL35/ZNF169/BAIAP2L2/DPY19L2P2/ACADSB/NTSR1/STOX2/GPR137C/SCN8A/MPO/ATOH7/CNTNAP5/MPPED2/PRKCE/COL9A3/MAP3K9/FGF13/NEU3/NEGR1/GLRA2/ASPHD1/KIAA1324L/GRM7/KCNB2/NAPB/PPM1H/INSM1/SLX4/RTBDN/TRHDE/SYT1/EPHA5/TMEM169/RAB3B/KCNF1/DLEU2/ZNF418/COL19A1/OTOGL/EIF4E/GDAP1/KCNC2/UNC13A/ELAVL4/GOLT1A/SVOP/GREB1L/FAM102B/NOVA1/NMNAT2/OSBPL10/LINGO3/ST6GALNAC5/HDAC9/HES4/CACNA2D1/GABRA1/FRMPD4/SV2B/ZDHHC23/DNM3/SYCE1L/EID2B/NKAIN2/ERC2/DLGAP1/WNT7B/TDRKH/SLC30A3/ANKHD1/MFSD6/ZNF138/HTR2A/ICAM5/SLC16A8/LY86-AS1/IQGAP3/MYO16/CNR1/SUSD4/ZDBF2/CREB3L1/SLC4A10/KCNV1/NTN5/RAB3C/FBXW7/UNC5D/SVEP1/DLGAP2/GPR12/NUAK1/ANO3/RGS4/LONRF2/TMEM17/NPTXR/XKR4/SYN3/SCN2B/SLC22A18/PAK3/RGS7BP/PLCB1/ATP8A2/PMS2/SLC16A14/HBA2/RAB27B/CDT1/SCN2A/CENPF/DOCK3/CDH8/GDA/PPM1E/TBC1D9/GPRASP1/RNF150/SGIP1/CDKL5/LSM11/PAIP2B/RIMS1/GRM8/OLFM3/PEG3/PPP2R2C/RGS17/RPLP0P2/GAS7/FAM126B/SAMD14/CSRNP3/ENPP5/HBA1/HUNK/DGKI/CECR2/G3BP2/MEIS3/IPCEF1/HECW2/PCLO/CREG2/SAMD12/TET1/TRIM36/DCAF16/PART1 |

| AMP-AD_STG_down | 90 | −0.15 | −0.65 | 9.81E-01 | 9.81E-01 | 3.69E-01 | 3104 | tags = 21%, list = 22%, signal = 17% | C2orf16/SLC6A17/PPEF1/VGF/RPH3A/NRN1/RNF165/GPRASP2/KIF17/KCNF1/OTOGL/ETV1/SVOP/EID2B/IQGAP3/KCNV1/RGS4/MEIS3 |

| IFG | |||||||||

| AMP-AD_IFG_down | 35 | −0.76 | −2.80 | 1.94E-03 | 3.09E-03 | 6.97E-04 | 2553 | tags = 71%, list = 18%, signal = 59% | CYP26B1/LY86-AS1/SPON2/CCBE1/SST/MLIP/WNT10B/TCERG1L/IL12RB2/GRASP/C2CD4C/SH2D5/RND3/SPRED3/VGF/OTOGL/IQGAP3/NPTXR/WISP2/MEIS3/ADCYAP1/ZDHHC23/NPTX2/BDNF |

| AMP-AD_STG_up | 141 | 0.34 | 1.61 | 1.95E-03 | 3.09E-03 | 6.97E-04 | 3164 | tags = 33%, list = 22%, signal = 26% | CDK2AP1/PRELP/NWD1/OLR1/AHNAK/ANGPT1/ARHGAP15/SLFN11/FOXJ1/SAMSN1/FMO2/CEBPA/CGNL1/C3AR1/SELPLG/TCEA3/SPN/LIPG/ITGAX/NHSL1/TP53I3/RANBP3L/GAL3ST4/FXYD5/PIK3R5/TMEM119/SYDE1/SLC5A3/IFIH1/SLC15A3/TLR3/HPSE/CYBB/SLC39A12/RASSF3/CD74/DOCK2/DDIT4L/HLA-DRA/SYK/SAMD9/MS4A7/CD84/TLR7/CD4/APBB1IP |

| AMP-AD_FP_down | 24 | −0.69 | −2.32 | 1.96E-03 | 3.09E-03 | 6.97E-04 | 1918 | tags = 67%, list = 13%, signal = 58% | MYL5/SST/SMAD6/ALDH1A1/PDE10A/GRASP/DUSP4/RND3/SPRED3/VGF/MEIS3/LPL/NPTX2/BDNF/HES4 |

| AMP-AD_STG_down | 90 | −0.50 | −2.25 | 1.99E-03 | 3.09E-03 | 6.97E-04 | 2763 | tags = 43%, list = 19%, signal = 35% | SLC16A6/PPEF1/C17orf102/GAD1/FBLN7/VWA5B2/ZBBX/RPH3A/VWC2/NCALD/PCYOX1L/SST/TNNI3K/SYP/DHRS11/PDE10A/KCNV1/INSM2/PCSK1/TAC1/GRASP/BEND5/SVOP/SLC6A17/SH2D5/SPRED3/TRIM54/VGF/OTOGL/IQGAP3/HSPB3/PRMT8/NRN1/RGS4/KCNF1/EID2B/MEIS3/ADCYAP1 |

| AMP-AD_IFG_up | 24 | 0.71 | 2.35 | 2.03E-03 | 3.09E-03 | 6.97E-04 | 2978 | tags = 75%, list = 21%, signal = 59% | ADAMTS2/CDK2AP1/PSD2/NWD1/OLR1/A2ML1/HOMER3/COL27A1/FOXJ1/POU3F2/SELPLG/SPN/APLN/MMP2/SLC15A3/HPSE/CD84/SLC6A12 |

| AMP-AD_DLPFC_up | 70 | 0.63 | 2.65 | 2.04E-03 | 3.09E-03 | 6.97E-04 | 1637 | tags = 49%, list = 11%, signal = 43% | NRIP2/ADAMTS2/PRELP/HSD11B2/ISYNA1/SFRP2/S100A4/FANCC/SLC4A11/NWD1/ST6GALNAC2/PHYHD1/SLC6A9/KCNJ10/ELK1/A2ML1/NEFH/HSPA2/CCDC69/PFKP/LSP1/COL27A1/KCNJ16/TMCC2/AQP6/ANLN/SLC5A11/MT1F/RBPMS2/FOXO4/CCDC102A/COL5A3/SPN/APLN |

| AMP-AD_DLPFC_down | 55 | −0.65 | −2.59 | 2.09E-03 | 3.09E-03 | 6.97E-04 | 2836 | tags = 58%, list = 20%, signal = 47% | SLC16A6/PPEF1/C17orf102/SPDEF/ALOX12B/ZBBX/SPON2/TNFRSF18/PCYOX1L/SST/PNMA5/PRSS35/ZNF334/MATN3/ALDH1A1/SDSL/RBM3/PRTN3/WDR86/FRMPD2/VGF/MDK/IQGAP3/ANKRD30B/TET1/MEIS3/ADCYAP1/SLC30A3/MPO/HMGN2/BDNF |

| AMP-AD_PHG_down | 479 | −0.34 | −1.93 | 2.13E-03 | 3.09E-03 | 6.97E-04 | 2614 | tags = 30%, list = 18%, signal = 25% | PKD2L1/CPNE9/PPEF1/KCNB2/C17orf102/ORC6/CYP26B1/HAR1A/RGS7/LDHA/PARM1/STYK1/MPPED2/RPRML/GAD1/STX1A/FBLN7/NKD2/SUSD5/NRXN3/SLC39A10/UNC13C/RFK/KCNQ3/DOC2A/ENC1/CAMKK2/RASL11B/VWA5B2/GLUD2/DNAL4/SYT1/SLC22A18/ZBBX/CDK5R2/FAM3C/LY86-AS1/TBR1/GPR22/RPH3A/SPON2/CCKBR/VWC2/FAM81A/TRO/CGREF1/CYP26A1/MOAP1/NCALD/LOXHD1/KCNK10/PCYOX1L/SST/TUBB2A/SORCS3/CCDC144B/SLC17A7/HPCA/EPHA3/LGI2/CITED1/MLIP/WNT10B/SYP/OLFM3/JAK3/HOPX/DRP2/DHRS11/NECAP1/PLK2/SYT5/SORCS1/ITFG1/TRPV6/GAP43/PDE10A/KCNV1/TCERG1L/KIF12/CTHRC1/MUM1L1/UNC13A/INSM2/DNAJC5G/NRSN1/IL12RB2/PPP1R14C/PCSK1/PCDHAC2/TAC1/GRASP/PAK1/AP1S3/FAM153B/RAPGEF4/DUSP4/PART1/QPCT/HS3ST2/BEND5/SLC22A9/NELL1/CREG2/VIPR1/CYP2C8/FAM153A/ABCC12/SVOP/SLC6A17/SH2D5/RAB3B/KCNJ4/SPRED3/GDA/TRIM54/VGF/OTOGL/CREB3L1/IQGAP3/SYTL2/FAM163B/RPLP0P2/HSPB3/PRMT8/NRN1/RGS4/KCNF1/MAL2/HUNK/MEIS3/ADCYAP1/SLC30A3/RXFP1/ZDHHC23/C1QL3/LPL/NPTX2/BDNF/ELAVL4/HES4 |

| AMP-AD_CBE_up | 849 | −0.25 | −1.47 | 2.17E-03 | 3.09E-03 | 6.97E-04 | 2986 | tags = 28%, list = 21%, signal = 23% | CMTM1/CEBPD/CHST2/SERPINE1/ADRA1D/EPHB4/DOK6/NUAK1/GIMAP2/POC1A/PHF3/DPF1/RELL1/RAP1GAP2/IL1RAPL1/HSP90AB1/GABRE/ANKRD12/AMIGO2/CAMK1/ZXDA/SRGN/CLEC2B/INCENP/VAV1/NUDT17/GOLGA4/FKBP4/TNFRSF12A/C1QA/PSMC1/GABRB1/TBC1D9/POLR2A/ZDHHC2/RPL23AP82/CLEC18B/GPR6/STYK1/EIF3L/CDC25A/ITPR3/SLC12A2/TCP11L1/RGS16/CD163/ZNF17/MAP3K8/GMFG/PDK3/SHISA3/SLC2A12/HSP90AA1/S100A11/UNC13C/ZNRF2/TNNT2/GLUD2/DNAJB1/DDX21/TRMT12/GTF2I/DUSP3/FBXL14/SOCS3/GPR4/SOS1-IT1/MMRN1/SMAP1/HECA/NAGS/TRIM5/RNF169/KCNH7/HGF/MFSD9/GRK5/GNL3L/ZBTB16/PTAR1/GPR22/KLHL9/SERTAD1/SPON2/CCT4/BTN2A2/KLHL11/CLVS2/IMPA2/ZDBF2/TMED5/HSPB1/CLIC1/SSTR2/PCDHGC4/DEK/BTN2A1/SLCO2A1/ZCCHC12/PJA1/PGM2L1/ITGA10/LIMK2/LCP1/ITPRIP/EDIL3/DNAJA1/N4BP2/OLFML2B/PCDHGB5/HSPA8/TMEM183A/MAFG/HSPG2/P4HA2/CCDC144B/BGN/ACTR8/USP32/SSTR1/HIST1H2AC/SGPP2/ZNF808/IFITM1/ZNF420/STAB1/SYTL5/GJA4/SPP1/OLFM3/IL4R/ATP11B/F12/SLC32A1/LHFPL1/C1orf115/VAMP8/SUCLA2/KCNG2/TNFRSF10D/ZNF675/ADAT3/FPR1/ARHGAP20/SMAD6/PNP/BIRC3/GLRA2/SNHG10/LCA5/RECQL4/CRNKL1/GAP43/GTF3C4/PDIA6/CDKN1A/WDR86/RAB20/TMCC1/ZNF550/SERPINA1/FAM50B/AKAP9/ZNF256/PSMC3IP/CFH/TACR2/SOX4/PCDHGA9/TSKU/ZNF845/LONRF2/CHGB/C1QB/BAG3/PCDHA3/PCDHAC2/TAC1/IFITM2/ATF6/IGFBP7/PEAR1/ADAMTS1/HIST2H2BE/PECAM1/ACSL5/ANGPT2/ZNF813/PLS3/ICAM1/OSMR/NELL1/TUBA1C/HIST1H2BK/GADD45A/DOCK11/FLNA/DTX3L/TAGLN2/FRMPD2/MAFF/CHST3/CEBPZ/CP/PTGS2/ZNF483/S100A9/PPP1R15B/RRAGD/TCAP/NPTXR/RELB/NEMF/RNF19B/PRPF18/CRISPLD2/EMP1/BST2/S100A8/ENGASE/HIST2H2BF/FAS/RPL23AP7/CHI3L1/PPP1R12A/PRMT5/SERPINA5/TXNRD1/PCDHA4/C1QL3/CLIC4/GPN3/NPTX2/IFITM3 |

| AMP-AD_CTX_down | 968 | −0.27 | −1.57 | 2.21E-03 | 3.09E-03 | 6.97E-04 | 3484 | tags = 31%, list = 24%, signal = 25% | HBA2/PKMYT1/CAMK4/ACADSB/ESR1/PCLO/SUB1/NRG4/SCN3B/TECTA/PLAGL1/DHDH/REM2/TOX3/KCNS2/SFTPA2/MADCAM1/TMEM151B/CHRM3/LINGO3/SYCE1L/ICOSLG/RASAL1/GRM8/AKAP5/PTPRR/PRKCE/UQCRHL/PPP2R2C/NEUROD6/HECW1/HTR2A/L3MBTL1/ASB2/PPM1E/UBE2V2/MLLT11/MTF2/NECAB2/PHF7/ELMOD1/FANCA/GALNTL6/C1QTNF4/JAZF1/CHCHD7/ADRA1D/GSTO2/GRIN2B/CCDC122/RGS17/BEX1/NUAK1/HAS1/CLDN4/WDR66/RIMBP2/YPEL4/SUSD4/GABPB1/PTRH1/CRYM/GRIPAP1/PRKCD/FGFBP3/SPNS1/CENPE/C9orf139/SLC16A6/CLUL1/CRIPAK/WNT11/ACP2/LIAS/WASH5P/PPP1R3E/EFR3B/SRSF12/ANKRD36/PNCK/PPEF1/CACNG8/KCNB2/TBC1D9/CECR2/C17orf102/PIWIL2/HBA1/ORC6/SPATA7/HAR1A/GABRD/RGS7/PARM1/GLYCTK/MPPED2/GRM7/GAD1/PRRG3/NTSR1/FBLN7/NKD2/NRXN3/GREM2/GRB7/CHAF1A/DNM3/HDAC9/FTCD/G3BP2/C5orf34/ATOH7/ITGA2B/DOC2A/ADSSL1/VWA5B2/STAG3L3/CRHBP/A1BG/SCG2/SYT1/SLC22A18/SGIP1/GOLGA8A/HOOK1/PCDHA1/CES3/GPRASP1/ZBBX/CFP/TSNAX/FAM126B/LY86-AS1/RPH3A/SPON2/CCKBR/VWC2/FAM81A/PIGL/PAAF1/ZDBF2/TLE6/ENPP5/STAG3L2/CGREF1/PCDHGC4/LCN15/ZCCHC12/NCALD/PGM2L1/MYL5/EXOC3L1/DLGAP2/ZNF449/ZNF418/SLC4A10/ASPHD1/PCYOX1L/EIF4E/DTD1/GABRA3/TRAPPC2L/SST/DBIL5P/ERC2/SORCS3/SAMD14/GLDN/NMNAT2/TAF1D/LGI2/PLAG1/USP44/TNNI3K/LYPD6B/MLIP/WNT10B/TMSB4X/OLFM3/FAM122C/SUGT1P3/SLC32A1/DRP2/BRD9/DHRS11/CES2/KCNG2/MAGEC3/RNF128/FGF13/ARHGAP20/PLK2/SYT5/ZNF226/GLRA2/ITFG1/PTPRO/PLK4/TRPV6/KEL/TMEFF2/ARSG/RBM3/DPP6/GAP43/TIMM23B/PDE10A/KCNV1/TCERG1L/CDH7/COL7A1/TACR2/ANKRD19P/GOLT1A/HECW2/UNC13A/INSM2/INSM1/LONRF2/DNAJC5G/KIAA1324L/TCHH/NRSN1/CHGB/PPP1R14C/PCSK1/RIMS1/TAC1/TMEM17/GPR68/PAK1/AP1S3/PCDHA7/GNG4/ARMCX4/C19orf48/DUSP4/PART1/FBXL22/BEND5/SLC22A9/NELL1/CIRBP/CES4A/CREG2/TYRP1/ACTA1/PMS2P4/GABRG2/RCAN3/ABCC12/SVOP/SLC6A17/ARL17B/SH2D5/FRMPD2/HMGB3/RAB3B/SPRED3/GDA/TRIM54/VGF/OTOGL/HACL1/ANKHD1/CREB3L1/IQGAP3/NPTXR/CCT6B/ICAM5/BAIAP2L2/RPLP0P2/NAPB/HSPB3/PRMT8/NRN1/RGS4/C17orf107/TET1/KCNF1/EID2B/MAL2/ALOXE3/HUNK/MEIS3/ADCYAP1/SLC30A3/RXFP1/DCAF16/MPO/ZDHHC23/DRD4/SLN/SLC16A8/BDNF/ELAVL4/DCST2/RRN3P1/HES4 |

| AMP-AD_FP_up | 15 | 0.75 | 2.18 | 3.98E-03 | 5.07E-03 | 1.14E-03 | 2201 | tags = 53%, list = 15%, signal = 45% | NRIP2/ADAMTS2/PRELP/IGFBP5/ELK1/TCEA3/SYT6/SLC5A3 |

| AMP-AD_PHG_up | 838 | 0.19 | 1.12 | 1.09E-01 | 1.27E-01 | 2.87E-02 | 3103 | tags = 25%, list = 22%, signal = 21% | ADAMTS2/LCAT/CDK2AP1/PRELP/CNGA3/S100A4/SLC4A11/STEAP3/COL21A1/TNS3/ELN/PSD2/TGIF2/RBM38/NWD1/MDGA1/ANTXR2/ST6GALNAC2/PHYHD1/MYO10/SLC6A9/IGFBP5/STK33/ARMC3/AR/SPARC/KCNJ10/DLEC1/MTSS1L/ELK1/OLR1/ADCYAP1R1/ADAM33/A2ML1/ANTXR1/MTTP/AHNAK/RND2/TSPAN6/SYNDIG1L/ARHGEF6/HSPA2/ECM2/BNC2/COL8A2/NDNF/HOMER3/ANGPT1/MFAP4/CDC14A/PLCE1/SSC5D/ZDHHC11B/COL27A1/PLEC/ARHGAP15/IQGAP2/TMEM47/GYPC/SMO/WDR49/FZD7/PHLPP1/SLFN11/FOXJ1/CARD6/IGDCC4/PLTP/NEBL/PLIN4/PILRA/ANLN/FRZB/SAMSN1/SASH1/BBOX1/CARD11/IGF2/ARL6IP6/EYA1/MT1F/SSPN/SMAD9/CEBPA/C10orf105/NCF2/ENPP6/SLC25A43/CGNL1/BMP7/C3AR1/SYNE2/RFX2/BTN3A1/PHKG1/COL1A1/TOB1/RASSF8/ANKRD45/SELPLG/GTF2H2/TCEA3/KIF6/LRRIQ1/MDFIC/COL15A1/TEAD2/BOC/RHOQ/SPN/LIPG/PELI2/ITGAX/NHSL1/ACSM5/PPARA/EMX2/MAML2/PAQR8/APLN/SWAP70/NACC2/PLXNB2/SHROOM1/INPPL1/HLA-DPA1/RANBP3L/MMP2/HLA-DMA/PARD3B/KANK2/HEG1/PLCB3/FMNL2/FXYD5/FAM167A/LRP5/C4orf19/LTF/PIK3R5/NFATC4/SYDE1/MYL3/VCAN/IFIH1/ABLIM1/UTRN/KIF13B/TLN1/BTK/TRIL/HLA-DPB1/TCF7L2/SLC15A3/HLA-DRB1/SIGLEC8/SRPX2/TLR3/ITGB5/IL20RA/TLR4/HPSE/SLC45A3/CYBRD1/EZR/CYBB/ADD3/SLC39A12/SLC17A9/HLA-DOA/STON2/EYA2/ZDHHC11/LFNG/GMPR/CXCR4/GPC4/MLC1/CD74/DOCK2/DDIT4L/RXRA/ANKRD40/ADRB2/DBX2/HLA-DRA/ST18/SYK/MSRB3/SLC2A9/MS4A7/CD84/DDR2/SLC6A12/TBL1X/CLEC7A/SASH3/DAAM2/ACACB/CHADL/NFIA/KAT2B/TLR7/TBXAS1/CHST14/PDCD4/SMAD4/FAM181B/PSAT1/CD22 |

| AMP-AD_CTX_up | 1507 | −0.17 | −1.02 | 3.51E-01 | 3.78E-01 | 8.53E-02 | 3464 | tags = 27%, list = 24%, signal = 23% | NOS3/PAPLN/PRRX1/COL4A4/ITGA5/C1QC/ELOVL7/IKZF2/TBX2/MT2A/CALD1/CD34/SDF2L1/LAPTM4A/EPHA2/ITPKC/VSIG4/TCN2/AQP9/C4B/HLA-B/LYN/EMILIN2/KCNJ5/ST5/OTX1/RNF144B/ACTL6A/TNS1/IL13RA1/STK38/LAMP2/RNASE6/SIGLEC9/APOL4/DCHS1/TNFAIP8/FAH/PLSCR1/SLC39A11/MKNK2/HLA-C/IL6R/ALOX5AP/SLC7A2/FOXF1/HEPACAM/RHPN2/GPM6B/CPNE3/APOE/INPP5D/HSD3B7/ADAMTS7/MYCT1/PDLIM4/ATP1B2/LRRC3/SLC30A1/DAD1/MMP14/CD93/RFX4/CEBPD/WFIKKN2/NOTCH4/PCOLCE2/NLRC5/SERPINE1/LRP4/SLC9A3R1/PCDHGB6/EHD4/GPNMB/EPHB4/ECE1/PARP10/PTH1R/NMB/GIMAP2/PON2/MLKL/PTP4A3/NXN/ATOH8/RELL1/TRIM47/VCL/SCIN/GSN/TEP1/CERS1/SDC4/RAB34/VASN/GABRE/CMAHP/IFI16/PTCHD1/SRGN/CLEC2B/TP53BP2/RDH10/P2RY2/ADORA2B/MAOB/SLC14A1/QKI/CAT/ZNF366/TNFRSF12A/FGF2/HEPH/EHHADH/GABRB1/LIX1L/TSPO/ZDHHC2/NPC2/CR1/VWF/CLEC18B/TNFRSF1A/MPZL1/ITPR3/CLDN5/SUCLG2/EMP3/KLF6/REST/IFI44/CD163/MAP3K8/ZIC2/MFAP3L/ZFP36/PARP14/SHISA3/PCDHGB1/CDH5/S100A11/TAB2/WWTR1/LIMS1/IRAK3/TXNIP/ATP10A/PGF/LPP/MTM1/KDELC2/SOCS3/DDX60/GPR4/C1QTNF1/MMRN1/NAGS/TRIM5/XBP1/TMEM45A/SULT1C4/MECOM/RAB13/EPHX1/HGF/PLOD2/EIF4EBP1/MT1X/PKN3/ADAM12/MANEA/TRPC4/PTAR1/SHE/RARRES3/SLC9A9/MR1/DNAJC1/SERTAD1/ITGA7/FGFR1/P4HA1/PREX2/IMPA2/NMI/TMED5/MTHFD2/HSPB1/CLIC1/TNFRSF1B/APOL6/STK40/CBX2/IQGAP1/SOAT1/RGL3/RAB27A/BCL6/BTG2/ITGA10/LIMK2/FKBP10/ITPRIP/MT3/ORAI1/TCP11L2/MSN/PLEKHG2/HSPG2/ARHGEF10/COL4A1/BGN/CD44/PCDHB7/C11orf96/EPAS1/DOCK6/IFI35/HIST1H2AC/IFITM1/ABHD4/PCDHGA11/PMP2/SLC2A1/STAB1/GJA4/SPP1/PDK4/IL4R/CASZ1/CHI3L2/PALLD/PIM3/ZIC1/LHFPL1/VWA5A/FAM84B/IRF1/HK3/ITGB1/MATN3/TMED10/NAMPT/FNDC3B/VAMP8/TIMELESS/TP53/APPL2/BAMBI/TNFRSF10D/ATP6V0E1/TIPARP/RAB32/MYD88/CCNG1/NID1/FPR1/SMAD6/PNP/IL18R1/SAMHD1/SLC22A3/BIRC3/ELF1/NFKB2/AXL/TEAD4/SLC7A7/ANXA5/PRICKLE3/SESN2/PODXL/ADH1B/WEE1/LRP10/PDIA6/CDKN1A/ELOVL5/AZGP1/NEK6/RAB20/GTF3C6/PARP9/SERPINA1/SOD3/SLC39A1/TGIF1/CNN3/CFH/ANXA2/PLEKHA4/TMEM176A/ARHGAP29/TFPI/RHOC/ADAMTS9/BATF2/MAP7D3/KANK3/PITPNC1/C1QB/BAG3/LGALS3/BAZ1A/PGM2/CRYAB/ARHGEF19/SERPINH1/CYP4F11/IFITM2/MAPKAPK2/CLEC4E/GBP1/IGFBP7/PEAR1/SLC19A3/IL1R1/ELF4/ADAMTS1/TMEM176B/KIAA0040/ITGA1/PECAM1/S100A10/TBX3/ACSL5/ITGB4/TTC38/TUBB6/TAP1/PCDHGB7/ANGPT2/MCL1/IRAK2/ICAM1/OSMR/HMOX1/DNAH11/SLC2A4/AHCYL1/HAP1/TUBA1C/GGT5/PRKX/SH3BP2/HIST1H2BK/GMNN/LAP3/STOM/FLNA/AK3/GBP2/CDK2/SLC44A3/SFT2D2/DTX3L/PTBP1/TAGLN2/C1R/MAFF/CHST3/PLIN3/CP/ADIPOR2/PLP2/FERMT3/HEYL/NQO1/S100A9/PYGL/S100A16/TIMP1/C1S/EMP1/MAGT1/VAMP5/BST2/LAMA5/TNFAIP3/S100A8/WASF2/FERMT2/RELA/ROM1/NUAK2/THSD4/SMAD1/PDE4B/ANGPTL4/PLIN2/PYCR1/CHSY1/FAS/CHI3L1/CREB3L2/NGFR/SERPINA5/TCIRG1/DYNLT1/CD55/CAV1/MGST1/CLIC4/ALDH1L1/TMBIM1/GNG5/IFITM3/ZC3HAV1/SERPINB1 |

| AMP-AD_CBE_down | 621 | 0.15 | 0.86 | 9.51E-01 | 9.51E-01 | 2.15E-01 | 3980 | tags = 29%, list = 28%, signal = 22% | ADAMTS2/LYNX1/PDZD7/C16orf74/NT5M/TMEM69/PAQR7/ELK1/SLC35A1/WDR78/CYGB/IFITM10/MAEL/SLC25A45/BTBD17/HFM1/RYR1/SNRNP35/GPT/C1orf123/STRADB/IFT43/LIMK1/NMRAL1/TBCK/RSPH4A/ABCA9/POLR3G/MYO5C/ANKDD1A/ASAH2B/ANAPC7/DBF4B/TTC31/GEMIN8/NOS2/NME5/SH2D6/MYO7B/ENHO/C2orf81/ENO3/BEAN1/MMD2/KIF6/ISPD/TTC17/GLMN/BCL11B/DCC/IFT122/SCRT1/PCYT2/BBS5/FBF1/ABCA11P/DHRS12/SLC25A10/COQ3/KLHDC9/SIDT1/NHSL1/SLC38A6/C5/EEFSEC/E2F1/LRRC20/FREM1/EPHA10/MTFMT/HIRA/INO80C/SEMA3A/CYS1/DNAJC4/FER1L4/PCBP4/CBWD5/CEND1/SLC10A4/HGSNAT/DYNLRB2/TEKT3/SEMA5B/LGR6/SLC9A8/WDR54/CPS1/SCMH1/ZNF268/SLC25A29/U2AF1/TRPT1/PLA2G5/USH1C/LMF1/PQLC2/LAMA4/C4orf33/ZMYND12/ZNF596/HKR1/MPV17/LXN/GRIK3/SPAG8/TARBP1/TTC8/CERCAM/PSKH1/RCOR2/NAALADL2/VSIG10/ZFYVE16/CPEB1/UBXN11/GPR37L1/TAB1/MFN1/LPXN/MPV17L/FUS/RAPGEF6/FAM47E/SH3GLB2/TPK1/TRIM45/KLKB1/MEI1/COL11A2/MORN3/TMEM151A/BDH1/RNFT1/ZNF706/ETV5/SDK2/DHX35/OXA1L/PLEKHH1/CATSPER2/TOM1L2/NUPL2/ADAT2/RBM45/PURG/FAM189A1/CARNS1/IFT27/FBXO15/ADAMTS17/SAMD10/TAF7L/TTC21A/TRANK1/ABCA10/UNC5C/EFNA5/UPP1/DCAF8/FMO4/EPN3/HOGA1/MPPED1/SLC25A13/ZNF133/ELMO1/SLC12A4/SLC16A9/COL28A1/SHISA7/SULT1A1/UPP2/AMT/ZMAT1/FBN1/SCNN1D/NRSN2/TCTA/NOXA1/CDH23/C2orf40 |

The overlap at the gene level between the DEGs (using the same criteria, i.e. adjusted p to be less than 0.05 and fold change to be greater than 1.2) from this study and AMP-AD studies (MSBB and ROSMAP cohorts) was also shown in Supplemental Fig. 6. 9 genes and 1 gene were identified to be consistently up- or down-regulated, respectively, in AD compared to CN between this study and the STG region from MSBB study (Table 3). DEGs with consistent direction from other brain regions in AMP-AD studies are also shown in Table 3. Among which, complement C3a receptor 1 (C3AR1), triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2), CD74 molecule (CD74), CD86 molecule (CD86), integrin subunit alpha X (ITGAX, alias CD11C), major histocompatibility complex (MHC), class II, DR alpha (HLA-DRA), and oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor 1 (OLR1) were already described in DisGeNET and six of these genes (TREM2, C3AR1, ITGAX, OLR1, CD74, and HLA-DRA) were specially expressed in microglia, while CDK2AP1 was more abundant in astrocyte than in microglia (Supplemental Fig. 7) (Zhang et al., 2014, 2016). Among the DEGs with supporting evidence in the same brain region from the MSBB study, CDK2AP1 was the transcript with strongest association with antemortem cognitive measure (last MMSE score) and neurofibril tangle burden, while OLR1 was the transcript with strongest association with amyloid plaque burden (Table 4).

Table 3.

Overlapping differentially expressed genes between this study and the MSBB STG cohort. Corroborating evidence from other brain regions from MSBB and ROSMAP cohorts are also listed.

| Gene | Description | This study (STG) |

AMP-AD |

Associated with AD in DisGeNET? | Reference | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| logFC | AveExpr | p | adj.P.Val | logFC | AveExpr | p | adj.P.Val | Sex | Study | Model | Tissue | ||||

| Association with clinical diagnosis | |||||||||||||||

| ATG16L2 | autophagy related 16 like 2 | 0.33 | 4.47 | 1.12145999628934E-05 | 0.002 | 0.34 | 4.16 | 2.58E-05 | 0.04 | MALE | MSSM | Diagnosis.Sex | STG | ||

| C3AR1 | complement C3a receptor 1 | 0.54 | 2.51 | 0.001018063861604 | 0.023 | 0.49 | 3.99 | 7.85E-04 | 0.03 | ALL | MSSM | Diagnosis | STG | Yes | Lian et al. (2016) |

| 0.52 | 3.99 | 3.02E-04 | 0.00 | ALL | MSSM | Diagnosis | PHG | ||||||||

| CD74 | CD74 molecule | 0.67 | 8.17 | 1.44346484450377E-05 | 0.002 | 0.54 | 7.99 | 2.92E-04 | 0.02 | ALL | MSSM | Diagnosis | STG | Yes | Kiyota et al. (2015); Bryan et al. (2008); Matsuda et al. (2009) |

| 0.47 | 7.99 | 1.41E-03 | 0.01 | ALL | MSSM | Diagnosis | PHG | ||||||||

| CDK2AP1 | cyclin dependent kinase 2 associated protein 1 | 0.31 | 7.18 | 0.000568032270072 | 0.017 | 0.27 | 6.31 | 4.00E-04 | 0.02 | ALL | MSSM | Diagnosis | STG | ||

| 0.29 | 6.31 | 6.63E-05 | 0.02 | ALL | MSSM | Diagnosis | IFG | ||||||||

| 0.34 | 6.31 | 4.43E-06 | 0.00 | ALL | MSSM | Diagnosis | PHG | ||||||||

| 0.33 | 6.31 | 7.88E-04 | 0.01 | FEMALE | MSSM | Diagnosis.Sex | PHG | ||||||||

| 0.29 | 3.79 | 6.51E-05 | 0.01 | FEMALE | ROSMAP | Diagnosis.Sex | DLPFC | ||||||||

| GEM | GTP binding protein overexpressed in skeletal muscle | 0.55 | 2.59 | 0.002161800841942 | 0.036 | 0.49 | 4.89 | 2.25E-03 | 0.05 | ALL | MSSM | Diagnosis | STG | ||

| 0.68 | 4.89 | 1.72E-05 | 0.00 | ALL | MSSM | Diagnosis | PHG | ||||||||

| 0.71 | 4.89 | 6.45E-04 | 0.01 | FEMALE | MSSM | Diagnosis.Sex | PHG | ||||||||

| HLA-DRA | major histocompatibility complex, class II, DR alpha | 0.59 | 5.97 | 0.00069359016855 | 0.019 | 0.60 | 7.75 | 9.17E-04 | 0.03 | ALL | MSSM | Diagnosis | STG | Yes | Tan et al. (2016) |

| 0.52 | 7.75 | 4.19E-03 | 0.02 | ALL | MSSM | Diagnosis | PHG | ||||||||

| ITGAX | integrin subunit alpha X (alias CD11C) | 0.72 | 3.41 | 5.6729723651341E-05 | 0.005 | 0.46 | 3.58 | 1.64E-04 | 0.02 | ALL | MSSM | Diagnosis | STG | Yes | Kan et al. (2015) |

| MEIS3 | Meis homeobox 3 | −0.52 | 6.34 | 0.00071790964867 | 0.019 | −0.30 | 6.12 | 3.59E-04 | 0.02 | ALL | MSSM | Diagnosis | STG | ||

| −0.66 | 6.12 | 2.61E-09 | 0.00 | FEMALE | MSSM | Diagnosis.Sex | IFG | ||||||||

| −0.49 | 6.12 | 5.73E-09 | 0.00 | ALL | MSSM | Diagnosis | IFG | ||||||||

| −0.45 | 6.12 | 9.55E-10 | 0.00 | ALL | MSSM | Diagnosis | FP | ||||||||

| −0.50 | 6.12 | 2.38E-07 | 0.00 | FEMALE | MSSM | Diagnosis.Sex | FP | ||||||||

| −0.36 | 6.12 | 1.11E-03 | 0.01 | FEMALE | MSSM | Diagnosis.Sex | PHG | ||||||||

| −0.28 | 6.12 | 1.06E-03 | 0.01 | ALL | MSSM | Diagnosis | PHG | ||||||||

| −0.35 | 4.19 | 4.89E-08 | 0.00 | ALL | ROSMAP | Diagnosis.Sex | DLPFC | ||||||||

| −0.35 | 4.19 | 1.23E-08 | 0.00 | ALL | ROSMAP | Diagnosis | DLPFC | ||||||||

| −0.35 | 4.19 | 8.15E-06 | 0.00 | FEMALE | ROSMAP | Diagnosis.Sex | DLPFC | ||||||||

| −0.35 | 4.19 | 2.84E-04 | 0.02 | MALE | ROSMAP | Diagnosis.Sex | DLPFC | ||||||||

| OLR1 | oxidized low density lipoprotein receptor 1 | 0.75 | 2.45 | 1.47791575793266E-05 | 0.002 | 0.52 | 4.68 | 1.71E-04 | 0.02 | ALL | MSSM | Diagnosis | STG | Yes | D’Introno et al. (2005); Lambert et al. (2003); Luedecking-Zimmer et al. (2002); Serpente et al. (2011); Shi et al. (2006) |

| 0.59 | 4.68 | 1.15E-05 | 0.01 | ALL | MSSM | Diagnosis | IFG | ||||||||

| 0.60 | 4.68 | 1.10E-05 | 0.00 | ALL | MSSM | Diagnosis | PHG | ||||||||

| 0.54 | 4.68 | 2.51E-03 | 0.02 | FEMALE | MSSM | Diagnosis.Sex | PHG | ||||||||

| TREM2 | triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 | 0.62 | 3.84 | 0.000125024800527 | 0.007 | 0.59 | 5.41 | 1.07E-04 | 0.01 | ALL | MSSM | Diagnosis | STG | Yes | Guerreiro et al. (2013); Jonsson et al. (2013); Ulrich et al. (2017) |

| 0.50 | 5.41 | 9.30E-04 | 0.01 | ALL | MSSM | Diagnosis | PHG | ||||||||

Table 4.

Association with antemortem cognitive measures as well as neuropathological indices for transcripts that were consistently differentially expressed in this study and in the same brain region from the MSSB study. Samples from different brain regions were pooled and the statistical model corrected for the brain region in addition to the top five surrogate variables and gender using a linear regression model, while the main effect of interest was coded as a quantitative variable.

| genes | beta | AveExpr | T | P.Value∗ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Association with last MMSE score | ||||

| CDK2AP1 | −0.02 | 7.20 | −5.06 | 1.89E-06 |

| GEM | −0.03 | 2.55 | −3.21 | 1.77E-03 |

| CD74 | −0.02 | 8.21 | −2.61 | 1.04E-02 |

| ATG16L2 | −0.01 | 4.54 | −2.36 | 2.01E-02 |

| HLA-DRA | −0.02 | 5.97 | −2.19 | 3.08E-02 |

| MEIS3 | 0.01 | 6.38 | 1.86 | 6.58E-02 |

| OLR1 | −0.02 | 2.45 | −2.03 | 4.54E-02 |

| ITGAX | −0.01 | 3.42 | −1.03 | 3.06E-01 |

| TREM2 | 0.00 | 3.85 | −0.57 | 5.69E-01 |

| C3AR1 | 0.00 | 2.46 | −0.07 | 9.41E-01 |

| Association with Braak scorea | ||||

| CDK2AP1 | 0.12 | 7.18 | 4.97 | 1.88E-06 |

| MEIS3 | −0.10 | 6.34 | −2.54 | 1.23E-02 |

| OLR1 | 0.10 | 2.45 | 2.39 | 1.80E-02 |

| GEM | 0.11 | 2.59 | 2.28 | 2.41E-02 |

| HLA-DRA | 0.07 | 5.97 | 1.80 | 7.46E-02 |

| ATG16L2 | 0.03 | 4.47 | 1.79 | 7.62E-02 |

| CD74 | 0.04 | 8.17 | 1.11 | 2.71E-01 |

| C3AR1 | 0.06 | 2.51 | 1.40 | 1.63E-01 |

| ITGAX | 0.05 | 3.41 | 1.17 | 2.43E-01 |

| TREM2 | 0.02 | 3.84 | 0.46 | 6.45E-01 |

| Association with tangle total | ||||

| CDK2AP1 | 0.05 | 7.18 | 4.93 | 2.26E-06 |

| GEM | 0.06 | 2.59 | 3.66 | 3.52E-04 |

| OLR1 | 0.04 | 2.47 | 2.84 | 5.25E-03 |

| ATG16L2 | 0.02 | 4.46 | 2.45 | 1.55E-02 |

| MEIS3 | −0.04 | 6.33 | −2.09 | 3.88E-02 |

| HLA-DRA | 0.02 | 5.98 | 1.50 | 1.36E-01 |

| C3AR1 | 0.02 | 2.52 | 1.36 | 1.75E-01 |

| CD74 | 0.01 | 8.18 | 0.62 | 5.36E-01 |

| TREM2 | 0.01 | 3.86 | 0.57 | 5.68E-01 |

| ITGAX | 0.01 | 3.43 | 0.42 | 6.74E-01 |

| Association with plaque total | ||||

| OLR1 | 0.04 | 2.47 | 3.93 | 1.32E-04 |

| GEM | 0.04 | 2.59 | 3.58 | 4.68E-04 |

| MEIS3 | −0.04 | 6.33 | −3.28 | 1.32E-03 |

| CDK2AP1 | 0.02 | 7.18 | 2.47 | 1.47E-02 |

| HLA-DRA | 0.02 | 5.98 | 2.13 | 3.50E-02 |

| TREM2 | 0.02 | 3.86 | 2.05 | 4.21E-02 |

| ATG16L2 | 0.01 | 4.46 | 1.68 | 9.52E-02 |

| CD74 | 0.02 | 8.18 | 1.37 | 1.73E-01 |

| C3AR1 | 0.02 | 2.52 | 1.74 | 8.34E-02 |

| ITGAX | 0.00 | 3.43 | −0.17 | 8.63E-01 |

| Association with plaque densityb | ||||

| OLR1 | 0.17 | 2.45 | 3.87 | 1.64E-04 |

| MEIS3 | −0.16 | 6.34 | −3.28 | 1.31E-03 |

| CDK2AP1 | 0.08 | 7.18 | 2.98 | 3.34E-03 |

| TREM2 | 0.14 | 3.84 | 2.90 | 4.38E-03 |

| GEM | 0.15 | 2.59 | 2.90 | 4.39E-03 |

| HLA-DRA | 0.11 | 5.97 | 2.35 | 2.04E-02 |

| CD74 | 0.09 | 8.17 | 1.92 | 5.73E-02 |

| C3AR1 | 0.09 | 2.51 | 1.99 | 4.85E-02 |

| ATG16L2 | 0.03 | 4.47 | 1.60 | 1.12E-01 |

| ITGAX | 0.07 | 3.41 | 1.46 | 1.45E-01 |

p-value less than 0.05/10 = 0.005 is deemed significant.

Braak score is the Braak neurofibrillary stage (0-VI) as defined originally by Braak and Braak (1991). Thick 40–80 μm sections stained with Gallyas, Campbell-Switzer and thioflavine S stains are used to obtain this. These scores were converted to numerals (0–6) for statistical purposes.

Plaque density is the CERAD neuritic and/or cored plaque density (Mirra et al., 1991) defined using the CERAD templates as none, sparse, moderate and frequent. The value listed represents the highest density score seen in any of the three evaluated cerebral neocortex regions (frontal, temporal and parietal). However, if frequent neuritic or cored plaques are a rare finding, the score may be adjusted downwards to reflect this. These scores were converted to numerals (1–4) for statistical purposes.

Notably, in the constructed PPI network (Supplemental Fig. 2), CD33, a gene previously implicated to be an AD susceptibility by GWAS meta-analysis (Lambert et al., 2013), and C3AR1 are directly connected as they are both classified as exocytosis of specific granule membrane proteins in REACTOME, while CD33 and OLR1 are directly connected as they are both classified as exocytosis of tertiary granule membrane proteins. CD33 was identified as a differentially expressed in the STG region in this study (p = 0.001, adjusted p-value = 0.03) with no corroborating evidence from AMP-AD. The overlap for the DEGs from the STG and other brain regions from AMP-AD studies is listed in Supplemental Table 5.

GSEA and over-representation analysis were performed on the DEG results from the MSBB STG brain region (Supplemental Tables 6 and 7). Gene sets related to immune processes including neutrophil degranulation, interleukin 10 signaling, and interferon gamma signaling, complement and coagulation cascades, phosphatidylinositol signaling system, phagosome and neurotransmitter receptors and postsynaptic signal transmission were enriched from this study (q-value < 0.05) and also consistently observed in the MSBB study (p-value < 0.05) (Supplemental Table 8).

4. Discussion

This hypothesis free study identified immune-related processes and pathways, autophagy/protein degradation, oxidative stress pathways important for AD Aβ and tau pathology, confirming existing hypotheses (e.g. TREM2) and highlights novel important genes such as CDK2AP1 that is consistent between this study and the literature and is also associated with antemortem cognitive measures as well as neuropathological indices including both tau and amyloid pathology.

Several of the identified DEGs merit comments. Firstly, the differential gene expression finding of the genes from this study were consistently observed in the MSBB cohort. Secondly, remarkably, most of the identified DEGs are specifically or predominantly expressed by microglia in the brain, an observation in line with most risk genes for AD which are also highly, and many selectively, expressed in microglia. Thirdly, many have additional supporting experimental evidence. On a genetic level both TREM2 and OLR1 have been linked to AD, although the evidence for OLR1 is much less consistent and it has not made it to genome wide significant association even with the latest GWAS meta-analysis (D’Introno et al., 2005; Guerreiro et al., 2013; Jonsson et al., 2013; Lambert et al., 2003; Luedecking-Zimmer et al., 2002; Serpente et al., 2011; Shi et al., 2006; Ulrich et al., 2017). Several rare variants in TREM2 have been identified that significantly increase LOAD risk by 2- to 4- fold. TREM2 encodes a transmembrane receptor that binds polyanionic molecules and modulates microglial activity and survival. Further, TREM2 determines microglial functions associated with amyloid-β plaques and tau tangles (Lee et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2016; Yuan et al., 2016). In mice, the Trem2 signaling pathway is associated with the presence of disease-associated microglial, a subset microglia and infiltrating macrophages found at sites of neurodegeneration, thought to play a protective role (Deczkowska et al., 2018). OLR1 encodes an oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor that binds, internalizes and degrades oxidized low-density lipoprotein.

It has been hypothesized that oxidation of Aβ binding lipoproteins such as ApoE may modify their ability to transport Aβ and disrupt clearance (Ladu et al., 2000). In a very small genetic study, it was shown that patients carrying two copies of C alleles of +1073 C/T polymorphism in the 3′-UTR of OLR1 exhibited increased Aβ deposition as cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) but only among APOE ε4 non-carriers (Shi et al., 2006), suggesting CC genotype subjects may adversely affect the clearance of Aβ across the blood-brain barrier favoring its diversion towards perivascular drainage channels and ultimate deposition of Aβ as CAA, consistent with the hypothesis of Weller (Preston et al., 2003; Weller et al., 2000). Our association of the OLR1 transcript level with amyloid burden is consistent with the Aβ clearance hypothesis although the exact mechanism will still need to be studied, but it is foreseeable that the increase of oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor means the level of ligands is increased as well.

CDK2AP1 was not as widely studied as other microglia genes and was not readily linked to AD prior to this study, it is interesting to observe that CDK2AP1, the transcript with supporting evidence from the MSSB study, is the transcript with the strongest association with tau pathology and antemortem cognitive measurement, but also associated with amyloid burden (Table 4). It is a member of the blue module from WGCNA analysis with KAT8 being the hub gene. KAT8 encodes a member of the MYST histone acetylase protein family and was recently implicated as a genome wide association significant locus in UK Biobank cohort using parental history of Alzheimer’s dementia as a surrogate (Marioni et al., 2018). CDK2AP1 was shown to interact with nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase (NuRD) complex II and play a role in cell cycle and epigenetic regulations as well as differentiation (Bode et al., 2016; Deshpande et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2009; Spruijt et al., 2010; Wong et al., 2012).

While C3aR1 expression has been shown to correlate with cognitive decline and Braak staging (Litvinchuk et al., 2018), these findings were not supported by this study although C3AR1 was up-regulated in the STG in AD patients in this study. The complement pathway is a critical regulator of the innate immunity. Cleavage of the central complement factor C3 to C3a and C3b is the central hub of the complement pathway. C3a and C3b function through binding to their receptors C3aR and CR3, respectively. In an animal model of tauopathy, genetic deletion of C3ar1 attenuated gliosis and neuroinflammation. This was accompanied by a reduction in tau pathology, rescue of synapse and neuronal loss and a restoration of behavioral symptoms. Furthermore, a C3aR-dependent immune network was described which was conserved between mouse models and human AD (Litvinchuk et al., 2018). Next to modulation of tau pathology, a C3aR1-dependent neuron-immune interaction has been reported to influence Aβ pathology (Lian et al., 2016). Interestingly, the immune system and nervous system make different use of some of the same molecular machinery. C3 and the complement system are also implicated in synaptic remodeling (Fourgeaud and Boulanger, 2007).

CD11C/ITGAX, also called the complement receptor 4 (CR4), is an integrin membrane protein and combines with the beta 2 chain (ITGB2) to form receptor 4 (CR4), a receptor for inactivated C3b (iC3b). In a CVN-AD mouse model (Colton et al., 2008), AD pathology was demonstrated to be driven by local immune suppression as areas of hippocampal neuronal death are associated with the presence of immunosuppressive CD11c + microglia and extracellular arginase, which resulted in arginine catabolism and reduced levels of total arginine level in brain (Kan et al., 2015). In the APP/PS1 model, amyloid plaques-associated CD11c-positive microglia are believed to counteract amyloid deposition via increased Aβ-uptake and lysosomal degradation (Kamphuis et al., 2016). Furthermore, pharmacologic disruption of the arginine utilization pathway using eflornithine, an inhibitor of arginase and ornithine decarboxylase, protected the mice from AD-like pathology and significantly decreased CD11c expression. Inhibiting C3AR1 and CD11C-mediated processes could potentially be useful therapeutic targets.

Imbalance in production and clearance of amyloid beta (Aβ) is hypothesized to cause the deposition of Aβ in AD (Baranello et al., 2015). Autophagy is one of the important mechanisms for clearance of both intracellular and extracellular Aβ. Wani et al. reported that autophagy induced by alborixin, an ionophore, substantially cleared Aβ in microglia and primary neuronal cells was accompanied by up regulation of autophagy proteins autophagy related 5 (ATG5), autophagy related 7 (ATG7), and increased lysosomal activities, while PTEN knockdown or constitutive activation of AKT inhibited alborixin-induced autophagy and consequent clearance of Aβ, suggesting alborixin as a potential anti-Alzheimer therapeutic agent(Wani et al., 2019). In our study, we observed a down-regulation of AKT serine/threonine kinase 3 (AKT3) (p = 0.0003, adjusted p = 0.01) in the STG. Our over-representation analysis identified over-representation of PTEN regulation (p = 3.43 × 10−8, q-value = 4.2 × 10−6) and regulation of PTEN stability and activity (p = 1.63 × 10−5, q-value = 6.78 × 10−4) among the genes differentially expressed between AD vs. CN (with adjusted p≤0.05) in the STG, supporting this therapeutic strategy. From the WGCNA analysis, both the turquoise and magenta modules are related to autophagy and protein degradation. CDK5RAP3, the hub gene for the magenta module (Supplemental Fig. 5A) in the STG, was shown to participate in autophagy regulation in renal cancer (Li et al., 2019). Impairment of the ubiquitin-proteasome system is associated with the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases including AD (Jucker and Walker, 2013). FBXW11, the hub gene for the turquoise module in the STG, encodes a member of the F-box protein family which is characterized by the F-box, an approximately 40 amino acid motif. The F-box proteins constitute one of the four subunits of ubiquitin protein ligase complex called SCFs (SKP1-cullin-F-box), an E3 ubiquitin protein ligase complex which mediates the ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation of target proteins. FBXW11 binds to the amino-terminal extensions of PTEN α/β, and ubiquitinates lysines 235 and 239 in PTEN α to regulate PTEN α/β stability in cancer (Shen et al., 2019) and was also previously shown as a hub gene in prefrontal cortex analysis comparing AD to controls (Yang et al., 2020). Taken together, we provide evidence from this study to corroborate the literature reports on the role of autophagy in the AD disease process.

In the CNS, CD74, also known as HLA-DR gamma chain, is the invariant chain of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) Class II, similar to HLA-DR alpha chain subunit. CD74 is a microglial chaperone protein involved in proper antigen presentation for immune response. Immunohistochemistry revealed a significant microglial increase in CD74 primarily associated with neurofibrillary tangles and Aβ plaques (Bryan et al., 2008). CD74 has been suggested to interact with APP and to suppress the production of Aβ by derailing the normal trafficking of APP (Matsuda et al., 2009). Recombinant adeno-associated virus (AAV) delivery of CD74 could reduce Aβ production and improve learning and memory in a mouse model of AD (Kiyota et al., 2015).

Several limitations of this study are worth mentioning. Firstly, it is important to distinguish changes with normal aging from those specific to AD. For example, the expression of HLA-DR, CD80, and CD86 by monocytes increased with age, however, there was no statistically significant difference between AD patients with age-matched healthy controls (Busse et al., 2015). In this study, the AD and MCI samples are slightly older than cognitively normal controls, although the eigengenes of various co-expression modules were not associated with age at death. We also capture the variation of gene expression changes due to age via surrogate variables in the statistical model. Secondly, the downloaded AMP-AD DEG results may have been identified using a somewhat different statistical model (i.e. how the nuisance factors were adjusted) and there may also be differences in phenotype definition. In addition, the AMP-AD reprocessed RNA-Seq was aligned to GRCh38 with GenCode24 gene models using STAR/2.5.1b and quantified against GenCode 24 gene models using STAR, while this study was aligned GRCh37 with RefSeq gene models also using STAR but followed up with RSEM for quantification. The difference caused by these upstream steps shall be minimal. The statistical models used between the two analyses might be different. Therefore, some of the difference in the DEG results could be attributed to methodology difference and not entirely cohort difference. Thirdly, there is no easy way of differentiating whether a differentially expressed gene is causal to the disease process or as a result of the disease process. Fourthly, even though the contrast between AD and CN is the primary contrast in this study due to the limitation in statistical power for the MCI group. It shall be recognized that the contrast between MCI and CN is more clinically interesting especially when we move earlier in the disease process to reverse or stall the pathological disease process and the MCI contrast could shed light towards potential pathways for early intervention, whereas AD changes might be nonspecific consequence to the advanced neurodegeneration process. Lastly, this study is a bulk RNA-Seq study, and cell type specific gene dysregulation could have been missed with the tissue derived RNA samples. Further meta-analysis, causal inferential analysis (Beckmann et al., 2020; McKenzie et al., 2017), larger scale single cell RNA-Seq experiment will be helpful in pinpointing the most relevant pathway and genes to intervene in the disease process.

5. Conclusions

Together with substantial genetic studies and many mechanistic findings, the high number of microglial DEGs in this study provide additional evidence for a central role of microglia in AD pathogenesis but also highlight the role of astrocyte gene CDK2AP1 via its association with antemortem cognitive measure as well as neuropathological indices. The strong link at multiple levels of microglia with AD development hints at the immune system playing a key part in the etiology. Despite the prior failed immunomodulatory approaches (Chantran et al., 2019; Jaturapatporn et al., 2012; Jordan et al., 2020; Relkin et al., 2017), Alternative immunomodulatory strategies shall be investigated with a focus on earlier disease intervention.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All subjects signed an Institutional Review Board-approved informed consent, allowing both clinical assessments during life and several options for brain and bodily organ donation after death.

Consent for publication

All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The study was funded by Janssen Research & Development, LLC.

Author contributions

QSL designed the study, generated the data, analyzed and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed critical scientific editing to and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

Drs. Li and De Muynck are employees of Janssen Research & Development, LLC and may own stock/stock options in the company.

Acknowledgments