Abstract

Background

Understanding SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence among health care personnel is important to explore risk factors for transmission, develop elimination strategies and form a view on the necessity and frequency of surveillance in the future.

Methods

We enrolled 4927 health care personnel working in pediatric units at 32 hospitals from 7 different regions of Turkey in a study to determine SARS Co-V-2 seroprevalence after the first peak of the COVID-19 pandemic. A point of care serologic lateral flow rapid test kit for immunoglobulin (Ig)M/IgG was used. Seroprevalence and its association with demographic characteristics and possible risk factors were analyzed.

Results

SARS-CoV-2 seropositivity prevalence in health care personnel tested was 6.1%. Seropositivity was more common among those who did not universally wear protective masks (10.6% vs 6.1%). Having a COVID-19-positive co-worker increased the likelihood of infection. The least and the most experienced personnel were more likely to be infected. Most of the seropositive health care personnel (68.0%) did not suspect that they had previously had COVID-19.

Conclusions

Health surveillance for health care personnel involving routine point-of-care nucleic acid testing and monitoring personal protective equipment adherence are suggested as important strategies to protect health care personnel from COVID-19 and reduce nosocomial SARS-CoV-2 transmission.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, health care personnel, serology, COVID-19, personnel protective equipment use

Introduction

SARS-CoV-2 has had a huge impact on people's lives across the world since December 2019. The burden experienced by health care personnel has been particularly heavy. Apart from working against a new pathogen and trying to save lives, they have also had to protect themselves from the virus in order to continue to work and not spread the virus to their patients, colleagues, friends and families. Working on the front line, many health care personnel have lost their lives (Zhan et al., 2020). As of 1 May 2020, there were 12 526 COVID-19 related deaths among residents in care homes and hospitals of England and Wales and, as of 20 April 2020, 106 deaths among their health care personnel. In Italy, as of 1 June 2020, 27 952 health care personnel were officially recognized as COVID-19-infected by the Italian National Health Institute, and 167 physicians and 40 nurses had died (Chirico, Nucera, 2020).

It is suggested that repeated exposure to the virus during the care of COVID-19 patients increases infection risk (Chou et al., 2021, Ran et al., 2020). Studies have argued that it is essential to determine the risk factors for health care personnel in order to take precautions to minimize that risk (Zhan et al., 2020; Abou-Abbas et al., 2020). Furthermore, COVID-19 has been proposed as an occupational injury and is already accepted as such in Italy (Chirico and Magnavita, 2020a). Since the beginning of the pandemic, detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA has been the standard approach for COVID-19 diagnosis (CDC a 2020). Unlike nucleic acid tests designed to detect SARS-CoV-2 genetic material during acute infection, serological assays measure antibodies that remain detectable after acute infection, thus providing a useful method to detect cases that were not identified during the acute infectious phase (Li, 2020). Numerous point of care serological tests have been developed since the beginning of the pandemic with variable sensitivity and specificity.

With this multicenter study, we aimed to determine seropositivity early in the pandemic to explore potential risk factors for transmission among health care personnel, develop elimination strategies and form a view on the necessity and frequency of surveillance for future pandemic periods. We conducted the study solely on health care personnel working with children. Since the beginning of the pandemic, children are considered to be mildly affected (Abbasi et al. 2020; CDC b 2020; Dong et al., 2020) compared with adults for reasons that are still obscure, and they are less likely to transmit the infection (Wu, McGoogan, 2020).

Consensus agreements were obtained from all 32 centers, and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and the Ethics Committee of Hacettepe University (approval number 2020/11-57)

Material and method

Design and setting

We conducted a cross-sectional seroprevalence study for antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 among health care personnel working in pediatric units at 32 hospitals from 7 different regions of Turkey. Study participants were enrolled between 25 May and 10 June 2020. The first confirmed case of COVID-19 was reported on 11 March 2020 in Turkey in Marmara Region, and at the time of the study, the total number of cases was 173 958; April was the peak month, with newly diagnosed cases exceeding 5000 per day.

Population: Health care personnel at each study hospital were eligible to be enrolled in the study if they regularly had direct or indirect contact with pediatric patients with COVID-19, who were cared for in the emergency department, intensive care unit, or outpatient COVID-19 units or COVID-19 wards. Physicians from professors to residents, nurses, radiology technicians and other medical staff were enrolled. Participants were informed about the study through staff meetings. Health care personnel volunteered to participate by presenting to the assigned person for each center. They were screened for inclusion criteria, gave written informed consent for volunteer participation, completed a brief survey, and underwent a prick test. Survey data included demographics, medical history, occupation, years in occupation, workplace (clean or contaminated area), working hours per week, dates and results of prior nucleic acid and serologic tests, personal protective equipment (PPE) and face shield wearing practices, adoption of social distancing, COVID-19 diagnosis in colleagues or family, and whether they believed or suspected they had previously had COVID-19. In addition, participants were asked if they had symptoms such as fever, runny nose, cough, myalgia, loss of taste and smell in the last 3 months and any contact history with a COVID-19 patient without wearing a mask.

Emergency departments, intensive care units, outpatient clinics and wards reserved for potential or confirmed COVID-19 patients were considered ‘contaminated areas’ while ‘clean areas’ were administrative areas and wards where patients who had tested negative for COVID-19 by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) were accepted.

Universal mask usage—masks worn by personnel throughout their shift and by patients >2 years old and with no contraindications where breathing would be compromised—was mandatory nationwide. The health care personnel from each center had similar working days and working hours per week (mean 24 hours/week) since 6 April 2020; physicians and nurses had the longest working hours.

Point of care testing was carried out for all participants by the same assigned person at each center.

Ecotest CE rapid test for IgM/IgG Assure Tech. Co. Ltd was used for serologic tests. The test manufacturer reports relative sensitivity and specificity for immunoglobulin (Ig)M to be 93.7% and 99%, respectively, and 98.8% and 98.7% for IgG. Tests were applied and interpreted according to the manufacturer's instructions. IgM, IgG or both IgM and IgG positivity was considered to be a positive result.

Data analysis

All participants’ data were collected and analyzed using SPSS IBM version 26. We compared groups using Fisher's Exact Test for categorical variables and Wilcoxon Cox for continuous variables to identify potential factors associated with positive serology.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of health care personnel by profession

| Occupation | Number (%) | Age Mean Years (Range) | Sex F/M | Years In Profession Mean Years (Range) | Comorbidities |

Serology |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | HT | DM | Isupp Tx | Cancer | ESRD | Asthma | Other | Positive (N) (%) Positive (no) (%) | Negative(N) (%) | |||||

| Prof. Dr. | 149 (3.1) | 52.7 (42-67) | 81/65 | 28.44 (15-44) | 92 | 6 | 26 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 14 | 2(1.4) | 146 (98.6) |

| Assoc. Prof. Dr. | 188 (3.9) | 44.17 (36-64) | 134/50 | 20.32 (9-40) | 140 | 10 | 12 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 7 | 13 | 13(6.9) | 173 (93.1) |

| Asst. Prof. Dr. | 149 (3.1) | 36.01 (25-59) | 108/41 | 10.64 (1-37) | 116 | 4 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 13 | 14(10.1) | 134 (89.9) |

| Consult. Dr. | 654 (13.4) | 38.64 (25-67) | 395/222 | 13.87 (1-44) | 521 | 20 | 30 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 26 | 45 | 41(6.9) | 593 (93.1) |

| Resident | 983 (20) | 28.25 (20-34) | 654/280 | 3.57 (0-32) | 861 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 22 | 84 | 39(13.1) | 982 (20.7) |

| Nurse | 1702 (34.5) | 32.38 (19-62) | 1460/211 | 10.37 (1-42) | 1377 | 34 | 36 | 11 | 9 | 1 | 68 | 157 | 122(7.3) | 1677 (92.7) |

| Others | 1079 (22) | 37.77 (19-64) | 622/42 | 10.88 (0-39) | 841 | 40 | 34 | 6 | 8 | 0 | 50 | 87 | 61(5.7) | 994 (93.4) |

F: Female

M: Male

HT: Hypertension

DM: Diabetes mellitus

Isupp tx: Immunosuppressive treatment

ESRD: End-stage renal disease

Results

We enrolled 4927 health care personnel, all working in pediatric units, including 2123 (43.1%) physicians, 1702 (34.5%) nurses and 1079 (21.9%) other health care personnel, from 32 hospitals in 20 cities, across 7 regions throughout Turkey. The median number of participants was 171 (34–289) from each center. The study was carried out at the end of the third month and the beginning of the fourth month of the pandemic, just after national cases had reached peak numbers. Most personnel were young adults (median age 32 years; range 19–67 years, mean age 34.4) without chronic illness; 80.3% (n=3958) had no comorbidities. Among enrolled personnel, 2854 (57.9%) worked primarily in contaminated areas and 1720 (34.9%) in clean areas. A total of 299 (6.1%) tested seropositive for SARS-CoV-2, of whom the most affected group was nurses (41.4%), followed by physicians (38.0%). The brief survey results in Table 2 show that seropositive and negative participants were similar in age, sex, working areas, and comorbidities, except for diabetes mellitus (n = 21), which was more frequent in the seronegative group (n = 18, 3.1%). Seropositive participants worked a median 4 days per week while seronegative participants worked 6; however, working hours were similar (mean 24 hours/week). Seropositivity was more common among participants who did not universally wear protective masks, surgical masks or other (n = 180, 10.4%) versus those who did (n = 4697, 6.1%) (P = 0.036). Seropositivity was lower among those who wore face shields (n=2597) than those who did not (n = 2046, 5.2% vs 7.7%, P = 0.001).

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of health care personnel by seroconversion

| Characteristics of personnel (n=4927) | Serology+ n (%) = 299 (6.1) | Serology – n (%) = 4584 (93.9) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (median) (range 9-67 years) | 32 | 32 | |

| F/M | 229/70 | 3316/1268 | 0.1 |

| Chronic medical conditions n (%) | |||

| None | 248 (82.9) | 3757 (82) | |

| HT | 8 (2.8) | 105 (2.3) | |

| DM | 4 (1.4)) | 137 (3) | |

| Immune suppressive treatment | 3 (1) | 18 (0.4) | |

| Cancer | 1 (0.3) | 22 (0.5) | |

| ESRD | 0 (0) | 1(0) | |

| Asthma | 10 (3.3) | 172(3.8) | |

| Other | 25(8.4) | 372(8) | |

| Primary location of clinical work, n (%) | |||

| Contaminated Areas (ER ICU COVID Wards) | 176 (60.5) | 2750 (63.2) | 0.35 |

| Clean Area | 115 (39.5) | 1601 (36.8) | |

| Clinical role, n (%) 4710 | |||

| Physician, 2025 (43) | 105 (36.8) | 1920 (43.4)) | |

| Nurse 1671(35.5) | 123 (43.2) | 1548 (35) | 0.018 |

| Other 1014 (21.5) | 57 (20) | 957 (21.6) | |

| Typical number of clinical work- days/week (median) | 4 | 6 | |

| Typical number of clinical work hours /week (mean+SD) | 25.74±31.7 | 23.88±29.41 | |

| Did not universally use a surgical mask, N-95 respirator, or PAPR during all clinical encounters, n (%) | 18 (10.2) | 279 (6.4) | 0.036 |

| Did not use face shield, n (%) | 153 (52.3) | 1833 (42.3) | 0.001 |

| Did use face shield n (%) | 138 (47.4) | 2496 (57.7) | |

| Social distancing | |||

| Yes | 277 (93.3) | 4135 (93.7) | 0.7 |

| No | 20 (6.7) | 277 (6.3) | |

| Participant's belief he/she had COVID-19 | |||

| Yes | 114 (38.1) | 999 (22.7) | |

| No | 183 (6) | 3405 (77.3) | |

| SARS Co-V-2 + co-worker contact | 132 (44.4) | 1669 (37.8) | |

| SARS Co-V-2 + household contact | 37 (12.5) | 105 (2.4) | |

| Previous SARS Co-V-2 PCR | |||

| positive | 69 (23.2) | 120 (2.7) | |

| negative | 74 (24.9) | 1264 (28.7) | |

| not done | 154 (51.9) | 3027 (68.6) | |

| Geographic distribution | |||

| Middle Anatolia region | 31 (4.4) | 668 (95.6) | |

| Marmara region | 133 (6.9) | 1806 (93.1) | |

| Aegean region | 25 (3) | 820 (97) | |

| East Anatolia region | 13 (5.2) | 236 (94.8) | |

| South-east Anatolian region | 68 (12) | 500 (88) | |

| Black Sea region | 13 (6.4) | 190 (93.6) | |

| Mediterranean region | 3 (1.5) | 202 (98.5) | |

| Years in profession | |||

| 1-5 years | 124 (42.9) | 1834 (42.4) | |

| 5-10 years | 61 (21.1) | 855 (19.7) | |

| 10-20 years | 61 (21.1) | 1057 (24.4) | |

| >20 years | 43 (14.9) | 585 (13.5) |

n: Number

HT: Hypertension

DM: Diabetes mellitus

Isupp tx: Immunsuppresive treatment

ESRD: End-stage renal disease

A history of a SARS-CoV-2-positive co-worker (n = 132 (44.4%)) appears to increase the likelihood of seropositivity more than a household COVID-19 contact (n= 37, 12.5%). Only 38.4% of seropositive participants stated that they had previously had COVID-19. The total number of participants whose prior PCR test status could be retrived was 4751of whom 1572 (32.4%) had a prior PCR test and 189 (4.0%) were tested positive. Sixty-nine (23.2%) also tested positive for SARS- CoV-2 antibodies. Of those with a negative PCR result 74 (5.5%) tested positive for SAES-CoV=2 antibodies.

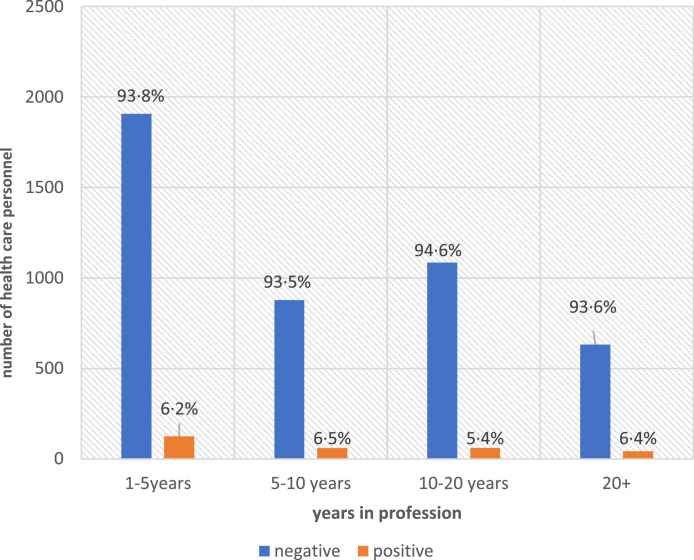

Being the least or the most experienced in the profession seemed to influence seroconversion. Participants with 1–10 years in the profession had the highest positivity rate (6.5%) for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, followed by participants with >20 years in the profession (6.2%). Seropositivity for those in their first 1–5 years of the profession was high (6.2%), only decreasing at the 10–20 year interval (5.4%) (Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

Health care personnel serology results by years in profession

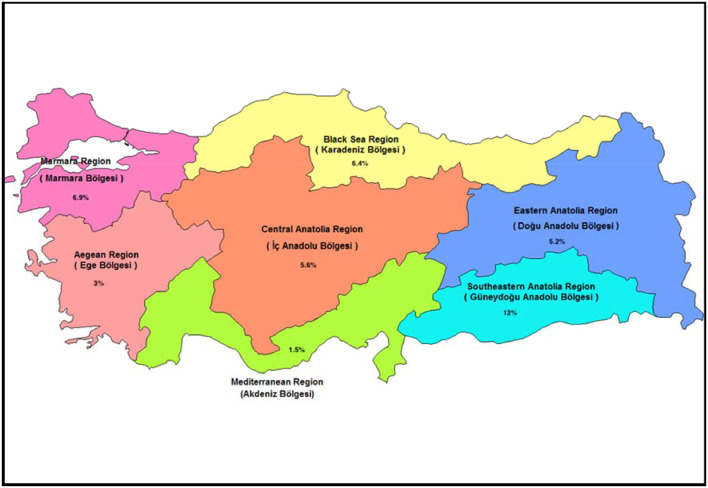

Seropositivity also varied by region of the country. The highest seropositivity prevalence was in South East Anatolia, followed by Marmara region; the Aegean and Mediterranean regions had the lowest prevalence (Figure 2 ).

Figure 2.

Distribution of seroprevalence of health care personnel by region

Discussion

Among 4927 health care personnel from 32 centers distributed throughout 7 regions in Turkey with mild to moderate local SARS-CoV-2 activity, 299 (6.1%) tested seropositive for SARS-CoV-2 69 days after the first national COVID-19 case was reported and 30 days after the peak of the first wave in Turkey at 5234 new cases per day (Figure 2).

Only 38.0% of the healthcare personnel who had antibodies detected reported any symptoms consistent with SARS-CoV-2 or believed they had previously had COVID-19. The percentage of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infected people is estimated to be approximately 40%–45% (Oran and AM, 2020; CDC c, 2020). Our study revealed a higher percentage of asymptomatic cases; potentially, healthcare personnel might have underestimated mild symptoms or attributed them to tiredness.

Only 1527 (31%) healthcare personnel had prior PCR testing for SARS-CoV-2; all were either symptomatic or with an unprotected close contact history with a confirmed COVID-19 case. Only 23.2% of participants with PCR-positive tests had antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. Among participants who tested PCR-negative, 5.5% were seropositive. It has been suggested that health care providers should undertake regular serological testing and symptom monitoring to protect health care personnel from the disease and prevent nosocomial transmission (Chirico et al., 2021).

Our study showed that health care personnel with 5–10 years of experience and >20 years of experience had similar seropositivity for SARS-CoV-2, with a tendency towards seropositivity among inexperienced personnel. Although working hours are the same but inexperienced personnel usually do most of the work had more patient contact, potentially impacting seropositivity. High seropositivity among health care personnel with >20 years of experience might be due to overconfidence leading to laxity in self-protection. In our study, work location (clean or contaminated area) or number of working days were not associated with seropositivity. Hence, inexperience and over-experience seemed to be independent risk factors. Therefore, we should develop strategies to educate less experienced personnel and warn the most experienced about self-protection. Widespread health surveillance of health care personnel should also be considered as a strategy to protect health care workers and prevent transmission. Conducting health surveillance programs with the intervention of occupational health professionals in the hospital setting could prevent both workers and patients from getting sick (Chirico, Magnavita, 2020b).

Although not statistically significant (P=0.024), personnel who did not universally wear a mask, surgical mask or PPE tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies more frequently. In addition, those who did not wear face shields tested positive more often than those who did.

Colleagues rather than household contacts led to infection more frequently among those who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies.

One of the study's limitations is that we did not ask for the prior PCR test timing. Most health care personnel with PCR positivity were seronegative. Either these people did not develop antibodies at all, or the antibodies declined to levels that could not be measured with the test kit we used (Patel et al., 2020). In our study 6.1% of health care personnel had SARS-CoV-2 antibodies within 3–4 months of COVID-19 being reported nationally. The majority with positive serology tests did not suspect that they had been infected nor had been tested for SARS-CoV-2 with PCR. In conclusion, our study results suggest that developing health surveillance strategies for health care personnel involving routine point-of-care nucleic acid testing and monitoring PPE adherence would be important to protect health care personnel from COVID-19 and reduce nosocomial SARS-CoV-2 transmission.

Conflict of interest

All contributing authors declare no conflict of interest.

The study is not funded by any organization.

The study is approved by Hacettepe University Ethics Committee (Approval No: 2020/11-57).

References

- Abbasi J. The promise and peril of antibody testing for COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323(19):1881–1883. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6170. May 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abou-Abbas Linda, Nasser Zeina, Fares Youssef, et al. Knowledge and practice of physicians during COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study in Lebanon. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1474. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09585-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/planning-scenarios.htmlcdc. (Last accessed November 13, 2020).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines for testing. July 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019cov2/hcp/testing-overview.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19 Response Team. Coronavirus disease 2019 in children - United States, February 12–April 2, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(14):422–426. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6914e4. accessed 13 November 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chirico F, Magnavita N. Covid-19 infection in Italy: An occupational injury. S Afr Med J. 2020;110(6):12944. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.2020.v110i6.14855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chirico F, Nucera G. Tribute to healthcare operators threatened by COVID-19 pandemic. J Health Soc Sci. 2020;5(2):165–168. doi: 10.19204/2020/trbt1(b). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chirico F, Nucera G, Magnavita N. Hospital infection and COVID-19: Do not put all your eggs on the "swab" tests. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology. 2021;42:372–373. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chirico F, Magnavita N. The Crucial Role of Occupational Health Surveillance for Health-care Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Workplace Health & Safety. 2021;69(1):5–6. doi: 10.1177/2165079920950161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou R, Dana T, Buckley DI, et al. Epidemiology of and risk factors for coronavirus infection in health care workers. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(7):W63–W64. doi: 10.7326/L21-0302. JulEpub 2021 Jun 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y, Mo X, Hu Y, et al. Epidemiology of COVID-19 among children in China. Pediatrics. 2020;145(6) doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0702. JunEpub 2020 Mar 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1199–1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oran DP, EJ Topol AM. Prevalence of Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:362–367. doi: 10.7326/M20-3012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel MM, Thornburg NJ, Stubblefield WB, et al. Change in Antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 Over 60 Days Among Health Care Personnel in Nashville. Tennessee DJAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.18796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ran L, Chen X, Wang Y, et al. Risk factors of healthcare workers with corona virus disease 2019: a retrospective cohort study in a designated hospital of Wuhan in China. Clin Infect Dis. 2020:ciaa287. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa287. Mar 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1239–1242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan M, Qin Y, Xue X, et al. Death from Covid-19 of 23 Health Care Workers in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2267–2268. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2005696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]