Abstract

Background

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) results in high out‐of‐pocket healthcare expenditures predisposing to food insecurity. However, the burden and determinants of food insecurity in this population are unknown.

Methods and Results

Using 2013 to 2018 National Health Interview Survey data, we evaluated the prevalence and sociodemographic determinants of food insecurity among adults with ASCVD in the United States. ASCVD was defined as self‐reported diagnosis of coronary heart disease or stroke. Food security was measured using the 10‐item US Adult Food Security Survey Module. Of the 190 113 study participants aged 18 years or older, 18 442 (adjusted prevalence 8.2%) had ASCVD, representing ≈20 million US adults annually. Among adults with ASCVD, 2968 or 14.6% (weighted ≈2.9 million US adults annually) reported food insecurity compared with 9.1% among those without ASCVD (P<0.001). Individuals with ASCVD who were younger (odds ratio [OR], 4.0 [95% CI, 2.8–5.8]), women (OR, 1.2 [1.0–1.3]), non‐Hispanic Black (OR, 2.3 [1.9–2.8]), or Hispanic (OR, 1.6 [1.2–2.0]), had private (OR, 1.8 [1.4–2.3]) or no insurance (OR, 2.3 [1.7–3.1]), were divorced/widowed/separated (OR, 1.2 [1.0–1.4]), and had low family income (OR, 4.7 [4.0–5.6]) were more likely to be food insecure. Among those with ASCVD and 6 of these high‐risk characteristics, 53.7% reported food insecurity and they had 36‐times (OR, 36.2 [22.6–57.9]) higher odds of being food insecure compared with those with ≤1 high‐risk characteristic.

Conclusion

About 1 in 7 US adults with ASCVD experience food insecurity, with more than 1 in 2 adults reporting food insecurity among the most vulnerable sociodemographic subgroups. There is an urgent need to address the barriers related to food security in this population.

Keywords: atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, disparities, food insecurity, social determinants of health

Subject Categories: Health Services, Epidemiology, Cardiovascular Disease

Food insecurity represents disruptions in food intake or eating patterns because of a lack of money and resources. In 2018, nearly 11% or 14.3 million households in United States were food insecure at least some time during the year.1 Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in the United States,2 can result in high out‐of‐pocket healthcare expenditures, which may potentially expose these individuals to food insecurity.2 Previous studies have shown that patients with ASCVD frequently report financial hardship from medical bills and experience the significant burden of medical debt.3, 4 However, few studies have examined the prevalence and the sociodemographic factors associated with food insecurity in this population.

Food insecurity has been associated with poor health status, worse cardiovascular risk factor profile, poor mental health, and unhealthy behaviors and diets,5 all of which contribute to poor health outcomes among individuals with ASCVD. Food insecurity has also been shown to be associated with higher cost‐related medication nonadherence,6 which can be further detrimental to individuals' health and lead to poorer health outcomes. As such, understanding the burden and predictors of food insecurity among adults with ASCVD, particularly among socioeconomically disadvantaged communities, may inform interventions that can minimize this issue and thereby improve clinical outcomes in these patients. Accordingly, we evaluated the prevalence and determinants of food insecurity among adults with ASCVD in the United States using a nationally representative sample.

Methods

We used data from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), a nationally representative annual cross‐sectional survey of the noninstitutionalized population in the United States, for years 2013 to 2018 and included participants aged ≥18 years. The data used in this study are publicly available from the NHIS website7 and the statistical code for the results can be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. This study was exempt from review by the Houston Methodist Institutional Review Board committee because NHIS data are deidentified and publicly available. Individuals were identified as having ASCVD if they reported having prior coronary artery disease or stroke.

Food security was measured using a validated 10‐item US Adult Food Security Survey Module, which assesses the frequency with which each household/adult reported food insecurity in the past 30 days. Each survey question was scored as “1” if reported to be “yes” and were then summed to a potential maximum of 10. Based on the aggregate score, the respondents were categorized into 2 groups: food secure (high and marginal food security with scores of 0 and 1–2, respectively) and food insecure (low and very low food security with scores of 3–5 and 6–10, respectively). The following variables were assessed as potential determinants of food insecurity: age (18–39, 40–64, and ≥65 years), sex (men and women), race/ethnicity (non‐Hispanic White, non‐Hispanic Black, non‐Hispanic Asian, and Hispanic), family income (high/middle‐income, and poor/low‐income), insurance status (private insurance, public insurance, and uninsured), education level (some college or more and high school or less), immigration status (US‐born and non‐US‐born), marital status (married/living with partner, unmarried, and divorced/widowed/separated), usual source of care (yes/no), and sexual minority (yes/no). Sexual minority included individuals who selected “gay,” “lesbian,” “bisexual,” “something else,” or “do not know” when asked about their sexual orientation by using the question “which of the following best represents how you think of yourself?".

We assessed the national survey–weighted proportion of adults with food insecurity among individuals with ASCVD and compared them with those without ASCVD using Rao‐Scott χ2 analysis. Then, we assessed the prevalence of food insecurity specifically among adults with ASCVD across different sociodemographic subgroups, both as a dichotomous variable (ie, food security versus food insecurity) and an ordinal categorical variable (ie, high, marginal, low, and very low food security). We also assessed the prevalence of each question of the 10‐item questionnaire separately. Next, we examined the association between food insecurity and the sociodemographic characteristics by using multivariable survey‐specific logistic regression models adjusted for the abovementioned sociodemographic variables, cardiovascular risk factors, comorbidities, and geographic region among individuals with and without ASCVD separately.

Next, we created a composite score of the sociodemographic characteristics that were significantly associated with food insecurity to study their cumulative association with food insecurity among individuals with ASCVD. We also created a composite score of the sociodemographic characteristics that were significantly associated with food insecurity among individuals without ASCVD to study their cumulative association with food insecurity in this population and compared it with the ASCVD population. Finally, we created a composite score using all of the potential determinants of food insecurity mentioned above and studied their cumulative association with food insecurity among individuals with ASCVD as a sensitivity analysis.

All analyses were performed using Stata SE version 16.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) and accounted for the complex survey design of the NHIS, including appropriate sampling weights and sampling units, to ensure that our results were nationally representative. We considered 2‐sided P<0.05 to be statistically significant.

Results

Our final study population included 190 113 adults, 81.6% of whom were aged <65 years, and 51.8% were women. Overall, 18 442 (adjusted prevalence 8.2%) individuals, representing 19.9 million US adults annually, had ASCVD, and of these 43.6% individuals were <65 years old and 43.4% were women. Among adults with ASCVD, 2968 (14.6%) individuals, representing 2.9 million US adults annually, reported food insecurity compared with 9.1% among those without ASCVD (P<0.001). Additionally, adults with ASCVD had 1.24 higher odds (95% CI, 1.14–1.35) of reporting food insecurity compared with those without ASCVD. The general characteristics of individuals with ASCVD by food security status are described in the Table.

Table .

Characteristics of Study Population Among Individuals With ASCVD, by Food Security Status

| Total, n | Food Secure, n (weighted %, 95% CI) | Food Insecure, n (weighted %, 95% CI) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 18 442 | 15 474 (83.9) | 2968 (16.1) | |

| Weighted sample size | 19 855 958 | 16 963 396 (85.4%, 84.7–86.1) | 2 892 562 (14.6%, 13.9–15.3) | |

| Age category, y | <0.001 | |||

| ≥65 | 11 378 | 10 336 (60.8%, 59.7–61.9) | 1042 (30.3%, 28.1–32.5) | |

| 40–64 | 6281 | 4569 (34.5%, 33.4–35.5) | 1712 (60.0%, 57.5–62.4) | |

| 18–39 | 783 | 569 (4.7%, 4.2–5.3) | 214 (9.7%, 8.1–11.7) | |

| Sex | <0.001 | |||

| Men | 9667 | 8372 (58.1%, 57.1–59.1) | 1295 (47.5%, 44.9–50.0) | |

| Women | 8775 | 7102 (41.9%, 40.9–42.9) | 1673 (52.5%, 50.0–55.1) | |

| Race/ethnicity | <0.001 | |||

| Non‐Hispanic White | 13 332 | 11 750 (77.8%, 76.6–78.9) | 1582 (55.5%, 52.7–58.2) | |

| Non‐Hispanic Black | 2567 | 1798 (9.8%, 9.1–10.6) | 769 (25.3%, 23.1–27.7) | |

| Non‐Hispanic Asian | 528 | 459 (3.3%, 2.9–3.7) | 69 (2.5%, 1.9–3.4) | |

| Hispanic | 1748 | 1290 (9.1%, 8.3–10.0) | 458 (16.6%, 14.4–19.2) | |

| Family income | <0.001 | |||

| Middle/high‐income | 9052 | 8621 (67.1%, 66.0–68.2) | 431 (19.4%, 17.4–21.6) | |

| Poor/low‐income | 7857 | 5427 (32.9%, 31.8–34.0) | 2430 (80.6%, 78.4–82.6) | |

| Insurance status | <0.001 | |||

| Public | 2929 | 2663 (21.5%, 20.6–22.5) | 266 (11.3%, 9.7–13.1) | |

| Private | 14 620 | 12 234 (74.6%, 73.6–75.5) | 2386 (75.8%, 73.4–78.1) | |

| Uninsured | 856 | 543 (3.9%, 3.5–4.4) | 313 (12.9%, 11.2–14.9) | |

| Education | <0.001 | |||

| ≥Some college | 8908 | 7822 (52.6%, 51.4–53.7) | 1086 (35.8%, 33.5–38.2) | |

| ≤High school | 9425 | 7561 (47.4%, 46.3–48.6) | 1864 (64.2%, 61.8–66.5) | |

| Usual source of care | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 17 538 | 14 811 (95.9%, 95.5–96.4) | 2727 (90.4%, 88.3–92.1) | |

| No | 775 | 560 (4.1%, 3.6–4.5) | 215 (9.6%, 7.9–11.7) | |

| Immigration status | <0.001 | |||

| Nonimmigrant | 16 574 | 14 002 (88.6%, 87.7–89.4) | 2572 (85.4% 83.5–87.2) | |

| Immigrant | 1860 | 1464 (11.4%, 10.6–12.3) | 396 (14.6%, 12.8–16.5) | |

| Marital status | <0.001 | |||

| Married/living with partner | 7973 | 7120 (59.7%, 58.7–60.7) | 853 (42.7%, 40.2–45.2) | |

| Unmarried | 1832 | 1360 (7.8%, 7.3–8.4) | 472 (14.8%, 13.3–16.5) | |

| Divorced/widowed/separated | 8602 | 6965 (32.5%, 31.6–33.4) | 1637 (42.5%, 40.1–44.8) | |

| Sexual minority* | <0.001 | |||

| No | 17 383 | 14 652 (97.3%, 96.9–97.6) | 2731 (95.7%, 94.6–96.5) | |

| Yes | 566 | 428 (2.7%, 2.4–3.1) | 138 (4.3%, 3.5–5.4) | |

| Region | <0.001 | |||

| Northeast | 3045 | 2603 (17.5%, 16.4–18.6) | 442 (14.5%, 12.6–16.6) | |

| Midwest | 4234 | 3658 (24.6%, 23.4–25.9) | 576 (21.1%, 19.0–23.4) | |

| South | 7260 | 5885 (39.0%, 37.6–40.5) | 1375 (48.2%, 45.4–51.1) | |

| West | 3903 | 3328 (18.9%, 17.7–20.1) | 575 (16.2%, 14.2–18.4) | |

| Number of high‐risk characteristics† | <0.001 | |||

| ≤1 | 3558 | 3476 (28.4%, 27.4–29.4) | 82 (3.7%, 2.8–4.9) | |

| 2 | 4416 | 4143 (28.9%, 28.0–29.8) | 273 (11.9%, 10.3–13.8) | |

| 3 | 4590 | 3957 (22.7%, 21.9–23.6) | 633 (24.9%, 22.7–27.2) | |

| 4 | 3718 | 2710 (14.1%, 13.4–14.9) | 1008 (32.2%, 30.0–34.5) | |

| 5 | 1832 | 1034 (5.2%, 4.8–5.7) | 798 (22.8%, 21.0–24.8) | |

| 6 | 328 | 154 (0.7%, 0.5–0.8) | 174 (4.5%, 3.6–5.5) |

ASCVD indicates atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

Sexual minority include gay, lesbian, bisexual, other, and unknown sexual orientation.

High‐risk characteristics include: 18 to 64 years of age, female sex, non‐Hispanic Black and Hispanic race/ethnicity, poor/low income, divorced/widowed/separated marital status, and private or lack of insurance.

Among adults with ASCVD, the prevalence of food insecurity was significantly higher among younger individuals (25.9% and 22.9% among individuals aged 18–39 and 40–64 years, respectively, versus 7.8% among those aged ≥65 years), women (17.6% versus 12.2% among men), non‐Hispanic Black and Hispanic individuals (30.1% and 23.4%, respectively, versus 10.7% among non‐Hispanic White respondents), those with poor/low family income (30.8% versus 5.0% among high/middle‐income), individuals who had private or no insurance (14.8% and 36.1%, respectively, versus 8.2% among those with public insurance), and those who were divorced/widowed/separated (18.2% versus 10.9% among married or living with a partner) (Figure 1). The details of the responses to each of the 10 questions included in the Food Security Survey Module and the distribution of food security among individuals with ASCVD are shown in Tables S1 and S2, respectively. Of note, 18.5% of individuals reported being worried about running out of food before they had money to buy more, 17.1% reported that they ran out of food before they had money to get more, and 15.5% reported that they could not afford balanced meals among individuals with ASCVD.

Figure 1. Prevalence and odds of food insecurity among individuals with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease by sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.

The % food insecure represents weighted proportions. *Adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, family income, insurance status, education, immigration status, usual source of care, marital status, sexual minorities, geographic region, cardiovascular risk factors, and comorbidities. Sexual minority include gay, lesbian, bisexual, other, and unknown sexual orientation. Cardiovascular risk factors include hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, current smoking, obesity, and insufficient physical activity. Comorbidities include chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, ulcer disease, cancer, arthritis, chronic kidney disease, hepatitis, and liver disease. OR indicates odds ratio.

In multivariable‐adjusted analyses among individuals with ASCVD, we found that those with the following characteristics had significantly higher odds of reporting food insecurity: <65 years of age (18–39 years odds ratio [OR], 4.04; 95% CI, 2.83–5.76] and 40–64 years [OR, 3.08; 95% CI 2.59–3.66]), women (OR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.01–1.33), non‐Hispanic Black or Hispanic race/ethnicity (OR, 2.32; 95% CI, 1.93–2.78 and OR, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.23–2.03; respectively), private or no insurance (OR, 1.78; 95% CI, 1.37–2.30; and OR, 2.27; 95% CI, 1.66–3.11), divorced/widowed/separated (OR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.01–1.36), and poor/low family income (OR, 4.74; 95% CI, 4.00–5.61) when compared with individuals who were aged ≥65 years, men, non‐Hispanic White, had public insurance, were married/living with partner, and had high/middle family income, respectively (Figure 1). In addition to these characteristics, those who were less than high school educated, did not have usual source of care, were US‐born, and were a sexual minority also had higher odds of having food insecurity among individuals without ASCVD (Table S3). Additionally, non‐Hispanic Asians and non‐US‐born individuals were found to have lower odds of food insecurity among individuals without ASCVD.

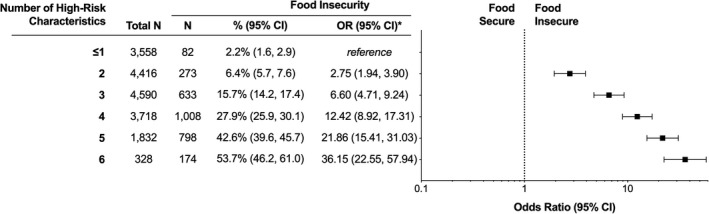

On assessment of the cumulative effect of the 6 observed high‐risk characteristics (ie, age <65 years, female sex, non‐Hispanic Black or Hispanic race/ethnicity, poor/low income, divorced/widowed/separated marital status, and private or no health insurance) that were individually associated with greater food insecurity among individuals with ASCVD, we found that among individuals with ≤1 of these characteristics, 2.2% of individuals were food insecure compared with 6.4%, 15.7%, 27.9%, 42.6%, and 53.7% among those with 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 high‐risk characteristics, respectively (Figure 2). In multivariable‐adjusted analyses, individuals with ASCVD and 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 high‐risk characteristics were found to have nearly 3‐fold (OR, 2.75; 95% CI, 1.94–3.90), 7‐fold (OR, 6.60; 95% CI, 4.71–9.24), 12‐fold (OR, 12.42; 95% CI, 8.91–17.31), 22‐fold (OR, 21.86; 95% CI, 15.41–31.03), and 36‐fold (OR, 36.15; 95% CI, 22.55–57.94) higher odds of being food insecure compared with those with ≤1 high‐risk characteristic. Similarly, on assessment of the cumulative association of all 10 potential high‐risk characteristics with food insecurity, there was a stepwise increase in the likelihood of being food insecure as the number of high‐risk characteristics increased among individuals with ASCVD (Table S4). Individuals without ASCVD also had a stepwise increase in the likelihood of being food insecure as the number of high‐risk characteristics increased (Table S5); however, the magnitude of this increase was less than in the ASCVD population (Figure S1).

Figure 2. Prevalence and odds of food insecurity among individuals with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease by number of high‐risk characteristics.

Note 1: The % food insecure represents weighted proportions. Note 2: High‐risk characteristics include 18 to 64 years age, female sex, non‐Hispanic Black or Hispanic race/ethnicity, poor/low income, divorced/widowed/separated marital status, and private or lack of insurance. *Adjusted for education, immigration status, usual source of care, sexual minorities, geographic region, cardiovascular risk factors, and comorbidities. OR for high‐risk characteristics were adjusted for the abovementioned variables except those included in the composite score of high‐risk characteristics. Sexual minority include gay, lesbian, bisexual, other, and unknown sexual orientation. Cardiovascular risk factors include hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, current smoking, obesity, and insufficient physical activity. Comorbidities include chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, ulcer disease, cancer, arthritis, chronic kidney disease, hepatitis, and liver disease. OR indicates odds ratio.

Discussion

In this nationally representative study, we found that nearly 1 in 7 adults with ASCVD reported food insecurity, representing nearly 3 million individuals with ASCVD in the United States annually. Food insecurity was substantially higher for individuals who were younger, female, non‐Hispanic Black or Hispanic, divorced/widowed/separated, had poor/low income, and had private or no health insurance. Additionally, among individuals with ASCVD and all 6 of these high‐risk characteristics, more than half of the individuals reported food insecurity and they were 36 times more likely to report food insecurity when compared with those with ≤1 high‐risk characteristic.

Our study contributes to the existing literature on food insecurity in several ways. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to provide detailed information on the prevalence of food insecurity among individuals with ASCVD in the United States at a nationally representative level. Additionally, we described food insecurity across diverse sociodemographic subgroups and examined the cumulative association of potentially higher‐risk characteristics with food insecurity to identify the most vulnerable subgroups and demonstrated that the prevalence of food insecurity increased progressively as the number of these high‐risk characteristics increased.

Previous studies have evaluated the burden of food insecurity among individuals with chronic illnesses and shown that individuals with cancer, lung disease, and cardiovascular disease have higher odds of being food insecure.8 Similarly, prior studies have assessed the association of food insecurity with cardiometabolic risk factors such as obesity, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension and shown that food insecurity was significantly more common in those with, versus without, cardiometabolic conditions.9, 10, 11 We evaluated the association between ASCVD and food insecurity and showed that those with ASCVD had a 60% greater (weighted prevalence 14.6% versus 9.1%) prevalence of food insecurity than those without ASCVD. Given the large burden of ASCVD in the United States, and the associated financial toxicity from medical bills and other health expenditures, our study highlights that a large number of these individuals may routinely face trade‐offs between affording food, medications, and other basic needs.

On assessment of the predictors of food insecurity among the ASCVD population, we found that those who were younger, female, identified as a minority racial/ethnic group, were divorced/widowed/separated, had low income, or had private or no health insurance had a higher prevalence of food insecurity, which was in accordance with previous studies.9, 10 Notably, in addition to uninsured individuals, even those with private insurance had substantially higher odds of food insecurity as compared with individuals with public insurance, which was consistent with previous reports showing that insurance coverage may not fully provide sufficient financial protection in this population.4 Though these specific characteristics were associated with food insecurity among individuals without ASCVD as well, on assessment of the cumulative effect of these high‐risk characteristics on food insecurity we found that individuals with ASCVD had a greater increase in the odds of food insecurity as the number of high‐risk characteristics increased compared with those without ASCVD, which underscores the urgent need to combat food insecurity among the ASCVD population.

Our findings have important public health implications. Food insecurity has been associated with multiple health behaviors and risk factors that contribute to suboptimal cardiovascular health,12 poor health outcomes,5 and increased healthcare costs.13 Moreover, food insecurity is associated with higher likelihood of cost‐related medication underutilization and nonadherence,6, 14 which can be further detrimental to the health of individuals with ASCVD and lead to poorer health outcomes. Considering that adherence to optimal diet and medications is especially critical in this population, assessing for the presence food insecurity in patients with ASCVD and supporting access to healthy food through federal nutrition programs for individuals who are food insecure can have significant implications for their clinical care. Moreover, previous studies have shown that even after adjustment for sociodemographic, dietary, and lifestyle factors, participants with food insecurity have a higher risk of all‐cause and cardiovascular disease mortality compared with those with no food insecurity.15 As such, interventions aimed at improving food security, or its root causes, in this population, might potentially influence their health outcomes.

Our study has some limitations. NHIS data consist of self‐reported information on food insecurity and ASCVD, and therefore is subject to recall bias and social desirability bias, which may underestimate the burden of food insecurity in this population. However, the questionnaire used in the NHIS is a validated instrument delivered by trained interviewers to minimize bias. Additionally, we were unable to assess the rural versus urban divide in food insecurity in this population.

In conclusion, nearly 1 in 7 individuals with ASCVD in the United States report food insecurity, with more than 1 in 2 adults with ASCVD being food insecure among the most vulnerable sociodemographic subgroups. Given the potential impact of food insecurity on long‐term risk of adverse health outcomes among patients with ASCVD, there is an urgent need to address the barriers related to food security in this population.

Sources of Funding

None.

Disclosures

Dr Nasir is on the advisory board of Amgen, Novartis, Medicine Company, and his research is partly supported by the Jerold B. Katz Academy of Translational Research. Dr Virani reports grant funding from the US Department of Veterans Affairs, World Heart Federation, and Tahir and Jooma Family; and honoraria from American College of Cardiology. The remaining authors have no disclosures to report.

Supporting information

Tables S1–S5

Figure S1

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10:e020028. DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.120.020028.)

Supplementary Material for this article is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/JAHA.120.020028

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 7.

REFERENCES

- 1.Coleman‐Jensen A, Rabbitt M, Gregory C, Singh A. 2019. Household food security in the United States in 2018, ERR‐270, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Available at: https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/94849/err‐270.pdf?v=125.9. Accessed January 15, 2021.

- 2.Virani SS, Alonso A, Benjamin EJ, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, Delling FN, American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee , et al.; Heart disease and stroke statistics‐2020 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;141:e139–e596. DOI: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valero‐Elizondo J, Khera R, Saxena A, Grandhi GR, Virani SS, Butler J, Samad Z, Desai NR, Krumholz HM, Nasir K. Financial hardship from medical bills among nonelderly U.S. adults with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:727–732. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khera R, Valero‐Elizondo J, Okunrintemi V, Saxena A, Das SR, de Lemos JA, Krumholz HM, Nasir K. Association of out‐of‐pocket annual health expenditures with financial hardship in low‐income adults with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in the United States. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3:729–738. DOI: 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gundersen C, Ziliak JP. Food insecurity and health outcomes. Health Aff. 2015;34:1830–1839. DOI: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herman D, Afulani P, Coleman‐Jensen A, Harrison GG. Food insecurity and cost‐related medication underuse among nonelderly adults in a nationally representative sample. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:e48–e59. DOI: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics . About the National Health Interview Survey. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/about_nhis.htm. Accessed January 15, 2021.

- 8.Charkhchi P, Fazeli Dehkordy S, Carlos RC. Housing and food insecurity, care access, and health status among the chronically ill: an analysis of the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:644–650. DOI: 10.1007/s11606-017-4255-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Myers CA, Mire EF, Katzmarzyk PT. Trends in adiposity and food insecurity among US adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2012767. DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.12767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gucciardi E, Vogt JA, DeMelo M, Stewart DE. Exploration of the relationship between household food insecurity and diabetes in Canada. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:2218–2224. DOI: 10.2337/dc09-0823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berkowitz SA, Berkowitz TSZ, Meigs JB, Wexler DJ. Trends in food insecurity for adults with cardiometabolic disease in the United States: 2005–2012. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0179172. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ford ES. Food security and cardiovascular disease risk among adults in the United States: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003–2008. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E202. DOI: 10.5888/pcd10.130244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berkowitz SA, Basu S, Meigs JB, Seligman HK. Food insecurity and health care expenditures in the United States, 2011–2013. Health Serv Res. 2018;53:1600–1620. DOI: 10.1111/1475-6773.12730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berkowitz SA, Seligman HK, Choudhry NK. Treat or eat: food insecurity, cost‐related medication underuse, and unmet needs. Am J Med. 2014;127:303–310.e3. DOI: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun Y, Liu B, Rong S, Du Y, Xu G, Snetselaar LG, Wallace RB, Bao W. Food insecurity is associated with cardiovascular and all‐cause mortality among adults in the United States. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e014629. DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.119.014629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Tables S1–S5

Figure S1