ABSTRACT

Background: The prevalence of mental disorders among asylum seekers and refugees is elevated compared to the general population. The importance of post-migration living difficulties (PMLDs), stressors faced after displacement, has recently been recognized due to research demonstrating their moderating role of on mental health outcomes. Traditionally, PMLDs were investigated as count variables or latent variables, disregarding plausible interrelationships among them.

Objectives: To use network analysis to investigate the associations among PMLDs.

Methods: Based on a cross-sectional measurement of seventeen PMLDs in a clinical sample of traumatized asylum seekers and refugees (N = 151), a partial correlation network was estimated, and its characteristics assessed.

Results: The network consisted of 71 of the 120 possible edges. The strongest edge was found between ‘Communication difficulties’ and ‘Discrimination’. ‘Loneliness, boredom, or isolation’ had highest predictability.

Conclusion: Our finding of an association between communication difficulties and discrimination has been documented before and is of importance given the known negative impact of discrimination on mental and physical health outcomes. The high predictability of isolation is indicative of multiple associations with other PMLDs and highlights its importance among the investigated population. Our results are limited by the cross-sectional nature of our study and the relatively modest sample size.

KEYWORDS: Network analaysis, PMLD, postmigration living difficulties, refugee

HIGHLIGHTS

This study network analytic study explored interrelations among postmigration living difficulties in refugees and asylum seekers.

Dense interrelations among PMLDs were unveiled with the edge between ‘Communication difficulties’ and ‘Discrimination’ being the strongest.

Abstract

Antecedentes: la prevalencia de trastornos mentales entre los solicitantes de asilo y los refugiados es elevada en comparación con la población general. La importancia de las dificultades de vida, posteriores a la migración (PMLD, por sus siglas en inglés), factores estresantes que se enfrentan después del desplazamiento, ha sido reconocida recientemente debido a investigaciones que demuestran su papel moderador en los resultados de salud mental. Tradicionalmente, los PMLD se investigaban como variables de recuento o variables latentes, sin tener en cuenta las posibles interrelaciones entre ellas.

Objetivos: Utilizar el análisis de redes para investigar las asociaciones entre PMLD.

Métodos: a partir de una medición transversal de diecisiete PMLDs en una muestra clínica de solicitantes de asilo y refugiados traumatizados (N = 151), se estimó una red de correlación parcial y se evaluaron sus características.

Resultados: La red constaba de 71 de las 120 posibles aristas. La arista más fuerte se encontró entre ‘Dificultades de comunicación’ y ‘Discriminación’. ‘La soledad, el aburrimiento o el aislamiento’ tenían la máxima predictibilidad.

Conclusión: Nuestro hallazgo de una asociación entre las dificultades de comunicación y la discriminación ha sido documentado anteriormente y es de importancia dado el conocido impacto negativo de la discriminación en los resultados de salud física y mental. La alta predictibilidad del aislamiento es indicativa de múltiples asociaciones con otros PMLDs y destaca su importancia entre la población investigada. Nuestros resultados están limitados por la naturaleza transversal de nuestro estudio y el tamaño de muestra relativamente modesto.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Análisis de redes, PMLD, dificultades de vida después de la inmigración, refugiado

Abstract

背景: 与一般人群相比, 寻求庇护者和难民中精神障碍的患病率较高。由于研究证明了移民后生活困难 (PMLD), 即移民后面临的应激源, 其对心理健康结果的调节作用, 最近得到了认可。传统上, 将 PMLD 作为计数变量或潜变量进行研究, 而忽略它们之间可能的相互关系。

目的: 使用网络分析来研究 PMLD 之间的关联。

方法: 基于对一个遭受创伤的151名寻求庇护者和难民 (N = 151) 临床样本中 17 个 PMLD 的横断面测量, 估计了偏相关网络, 并评估了其特征。

结果: 网络包括了 120 条可能的边中的 71 条。在‘沟通困难’和‘歧视’之间发现了最强的边。‘孤独, 无聊或隔离’具有最高的可预测性。

结论: 我们发现沟通困难与歧视之间的关联之前已有记录, 鉴于歧视对身心健康结果的已知负面影响, 我们的发现具有重要意义。隔离的高度可预测性表明与其他 PMLD 的多重关联, 并突出了其在被调查人群中的重要性。我们的结果受到我们研究的横截面性质和相对适中样本量的限制。

关键词: 网络分析, PMLD, 移民后生活困难, 难民

1. Background

Prevalence rates of mental disorders among refugees and asylum seekers are well-known to be elevated compared to the general population (Blackmore et al., 2020). While associations between mental disorders and trauma exposure have been extensively demonstrated (Steel et al., 2009), the impact of stressors occurring after displacement on mental health has been studied less intensively. Such stressors, also termed postmigration living difficulties (PMLD), include a variety of problems, for example, socioeconomic, social, and interpersonal factors, as well as factors relating to the asylum process and immigration policy (Li, Liddell, & Nickerson, 2016). Importantly, a meta-analysis demonstrated that multiple PMLDs moderate mental health outcomes of refugees (Porter & Haslam, 2005). For example, a lack of economic opportunities, non-permanent accommodation and isolation were all associated with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression (Porter & Haslam, 2005; Steel et al., 2006).

Traditionally, research has treated PMLDs as one or several latent variables, or as a count variable (Stuart & Nowosad, 2020). The count model focuses on cumulative effects and does not investigate how PMLDs are related to each other (Nickerson et al., 2021). In the latent variable model, individual PMLDs are assumed to be independent from each other. It seems rather plausible, however, that PMLDs do influence each other. For example, an insecure visa status will likely negatively affect the possibility to obtain a permanent accommodation. Such interactions between variables are accounted by the network approach. This approach conceptualizes disorders and related phenomena as the result of a network of causal interactions (edges in a network) among individual symptoms or factors (nodes in the network). Thus, the network approach provides a more plausible framework for understanding PMLDs than the latent variable approach (Borsboom, 2017). In addition, the network models allow investigating how PMLDs relate to each other, which cannot be accomplished by assessing PMLDs as a cumulative count.

Regarding war affected populations, the network approach has been used to study the association between psychopathology and exposure to war (De Schryver, Vindevogel, Rasmussen, & Cramer, 2015), stressful life problems (Jayawickreme et al., 2017), and displacement stressor (Mootoo, Fountain, & Rasmussen, 2019). However, no study used a network approach to study postmigration living difficulties in refugees resettled in a high-income country yet. Notably, refugees and asylum seekers in high-income countries face at least partially different postmigration challenges compared to the populations studied in the studies outlined above (e.g. populations in a conflict-affected setting). Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the interactions of PMLDs in a population of asylum seekers and refugees in a high-income, western-European country.

2. Methods

The participants were recruited from a patient population seeking or undergoing treatment at the time of the assessment at two outpatients’ clinics for victims of torture and war in Zurich and Bern, Switzerland. Individuals speaking one of the study languages (Turkish, Arabic, Farsi, Tamil, German, or English), being at least 18 years old and neither experiencing acute suicidality, nor current psychotic or severe dissociative symptoms were eligible to participate in this study. All participants were assessed by a psychiatrist, clinical psychologist, or a masters-level student of clinical psychology. Participants were reimbursed with CHF 40 (approx. $USD 40). The study was approved by the Ethics Committees of the Cantons of Zurich (KEK ZH-Nr. 2011-0495) and Bern (EK BE 152/12) Switzerland and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Participants’ exposure to trauma was assessed using 23 items derived from the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (Mollica et al., 1992), and symptoms of PTSD were measured with the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale (Foa, Cashman, Jaycox, & Perry, 1997). Post migration living difficulties in the last 12-months were assessed using the adapted 17-item Post-Migration Living Difficulties Checklist (Silove, Sinnerbrink, Field, Manicavasagar, & Steel, 1997) (PMLDC). Each of the 17 PMLDC items addresses a specific difficulty which is rated on a five-point scale ranging from 0 = not a problem to 4 = very serious problem. The items are summed to a total score with a range of 0–68 points. The PMLD scale has consistently been identified as a predictor of mental health among displaced populations (Schick et al., 2016) and showed good internal consistency in this study (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.87).

The network analysis followed current recommendations (Epskamp & Fried, 2018). First, items sharing a lot of variance can bias the results. Thus, highly correlated items are usually combined for the network analysis (Burger et al., 2020). However, no formal cut-off for when items should be combined exists. We obtained zero-order correlations between all items of the PMLDC and found that two items, namely ‘Difficulties obtaining financial assistance’ and ‘Not enough money to buy food, pay rent or buy necessary clothes’ were highly correlated with each other (Spearman’s ρ = 0.68). The strength of the correlation of all other items pairs was below ρ = 0.6. Therefore, we combined both items by calculating their mean into a new variable ‘Financial problems’. Second, we estimated a Gaussian Graphical Model, in which each PMLD is represented by a node and edges correspond to partial correlations between two nodes. The parameters of the network were estimated using a regularization procedure based on the glasso. Due to the exploratory nature of our analysis, the tuning parameter (lambda) was set to 0.25. Furthermore, we assessed predictability of each node. Predictability represents the upper bound of shared variance, measured in R2 of a node, assuming that all connections from other nodes are directed towards the node in question (Haslbeck & Waldorp, 2018). Third, we carried out robustness and accuracy assessments using a bootstrapping procedure implemented in the bootnet package (Epskamp, Borsboom, & Fried, 2018). A total of 0.9% of the data was missing and was handled using pairwise deletion for the network estimation and listwise deletion for the calculation of predictability. The network analysis was carried out in the R statistical environment.

3. Results

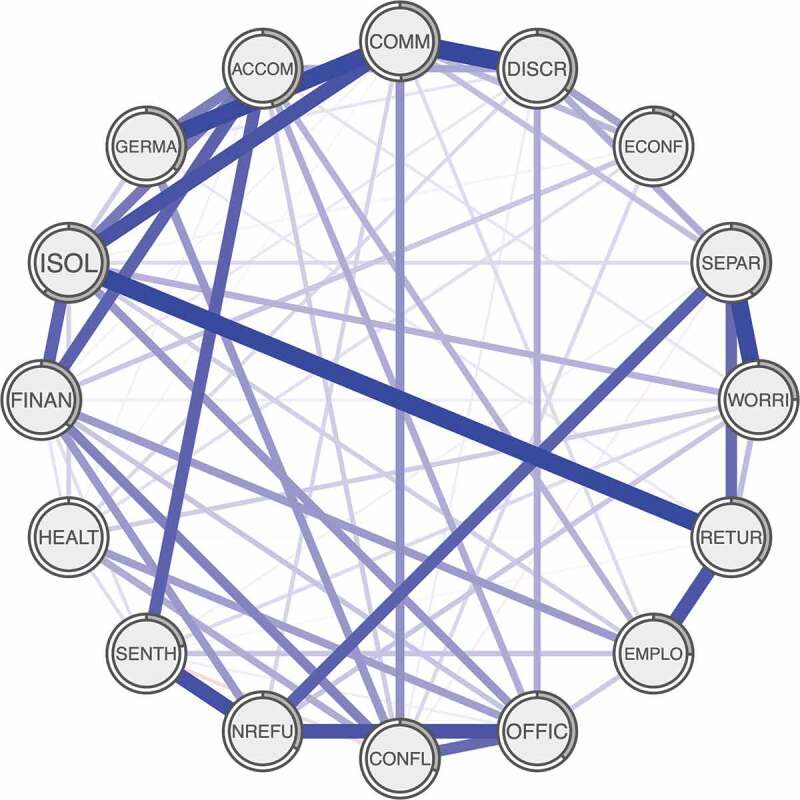

A total of 151 participants were included in the final analysis. A summary of their demographic data is presented in Table 1. The type of the experienced trauma is reported in Table S1. Of all PMLDs, ‘Being unable to return to your home country in an emergency’ was the most endorsed PMLD with a mean endorsement of 3.82 (SD = 1.49) on a one to four scale, closely followed by ‘Loneliness, boredom, or isolation’ (3.79, SD = 1.16; see Table 2). Of the 120 possible edges, 71 were estimated to be non-zero. The resulting network is depicted in Figure 1. The bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals of the edge weights were mostly overlapping and are shown in Figure S1. Correspondingly, only the edge weight between ‘Communication difficulties’ and ‘Discrimination’ was significantly stronger than at least half of the other edges (also see Figure S2). Average predictability was 0.326, and with 0.609 ‘Isolation’ had the highest predictability (also see Table 2).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| Male gender: n (%) | 106 (70.2) |

| Age, years: mean (SD) | 41.9 (9.8) |

| Nationality: n (%) Turkey (with n = 48 being Kurdish) Iran Sri Lanka Bosnia Afghanistan Others |

81 (53.6) 13 (8.6) 13 (8.6) 6 (3.9) 7 (4.6) 31 (20.5) |

| Level of Education: n (%) Not completed primary school Completed primary school Attended high school Completed high school Went to technical school Completed bachelor’s degree or equivalent Completed postgraduate degree |

21 (13.9) 21 (13.9) 27 (17.9) 29 (19.2) 17 (11.3) 15 (9.9) 10 (6.6) |

| Employment status: n (%) Full-time Part-time Unemployed Retired/homemaker Marital status: n (%) Single In a relationship/married Divorced/widowed Visa status: n (%) Awaiting asylum decision Other insecure visa status Secure visa status or naturalized Swiss citizens |

16 (10.6) 21 (13.9) 88 (58.3) 23 (15.2) 47 (31.1) 88 (58.3) 16 (10.6) 32 (21.2) 26 (17.2) 91 (60.2) |

| Duration of stay in Switzerland: years (SD) | 9.0 (6.6) |

| Average time in therapy in months | 28.8 (27.9) |

| Number of experienced trauma types: mean (SD) | 14.7 (4.1) |

SD = standard deviation.

Table 2.

Mean endorsements and predictability of postmigration living difficulties

| Variable | Mean | SD | Predictability |

|---|---|---|---|

| WORRI | 3.77 | 1.27 | 0.248 |

| SEPER | 3.44 | 1.46 | 0.405 |

| SENTH | 3.24 | 1.70 | 0.217 |

| RETUR | 3.82 | 1.49 | 0.358 |

| NREFU | 2.36 | 1.72 | 0.325 |

| ISOL | 3.79 | 1.16 | 0.609 |

| HEALT | 2.49 | 1.44 | 0.000 |

| GERMA | 3.26 | 1.31 | 0.356 |

| FASSI | 2.83 | 1.41 | NA |

| MONEY | 2.80 | 1.41 | NA |

| FINAN* | 2.82 | 1.29 | 0.370 |

| OFFIC | 2.47 | 1.51 | 0.374 |

| EMPLO | 3.26 | 1.44 | 0.253 |

| ECONF | 1.93 | 1.09 | 0.091 |

| DISCR | 2.37 | 1.42 | 0.351 |

| CONFL | 2.38 | 1.41 | 0.301 |

| COMM | 2.95 | 1.44 | 0.495 |

| ACCOM | 2.97 | 1.49 | 0.457 |

SD = standard deviation. Total range for each postmigration living difficulties: 0–4.

Figure 1.

The estimated network of 16 postmigration living difficulties

Each postmigration living difficulty is represented by a node. Edges represent partial correlations between the postmigration living difficulties. In the rings, the grey area represents predictability, with a full ring indicating R2 of 1. A cut value of 0 was used for the visualization.

4. Discussion

Among all PMLDs, ‘Loneliness, boredom, or isolation’ had the highest predictability and the second highest mean endorsement, making it a significant problem in the daily life of the participants in our sample. This finding stands in contrast to prior studies investigating PTSD and daily stressors in post conflict population in low-income countries, which found problems concerning basic needs to be most important to the network structure (De Schryver et al., 2015; Jayawickreme et al., 2017). This could reflect the different settings of the studies’ populations with our participants currently living in a high-income country where basic needs and safety are generally provided. Accordingly, mean endorsement of ‘not having enough money for necessities’ was low in our analysis (see Table 2). However, our finding is in accordance with several studies reporting high level of loneliness and isolation in refugees and asylum seekers, e.g. (Strijk, van Meijel, & Gamel, 2011). The high predictability of isolation and loneliness indicates that it might be a consequence of other PMLDs. Indeed, it seems likely that having communication difficulties and being separated from one’s family, with both being related to isolation in our analysis, can lead to perceived loneliness.

The edge between ‘Communication difficulties’ and ‘Discrimination’ was the strongest indicating that these two PMLDs were strongly related, even after controlling for the influence of all other PMLDs. This is in line with a systematic review demonstrating that language barriers are associated with perceived discrimination in refugee women during perinatal care (Small et al., 2014). Importantly, discrimination is associated with worse mental and physical health outcomes (Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009). Thus, language and cultural interpreters might help to reduce discrimination perceived by refugees and could also lead to better health care outcomes.

Our study is subject to several limitations. First and most importantly, the sample size was relatively small for the number of nodes included in the network, leading to limited generalizability and validity of our results. Second, PMLDs are known to be related to mental disorders and additional factors. Thus, by only including PMLDs in the network analysis we were not able to investigate how these contextual factors impact the associations between different PMLDs. Due to these limitations and the exploratory purpose of this study, we see multiple avenues for future research. First, our preliminary findings should be replicated in studies with bigger sample sizes and in populations stemming from different settings. Second, future research should include factors known to be related with PMLDs (e.g. psychopathology) in the network analysis to broaden the understanding of the context in which PMLDs arise. Third, based on our findings suggesting that communication difficulties and perceived discrimination are uniquely associated with each other, future research could investigate derived hypotheses, for example, whether this relationship is mediated by religion or ethnicity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We want to thank all the participating patients, interpreters, assessors, and research assistants.

Funding Statement

This study was partially supported by the Parrotia Foundation, the Swiss Foundation for the Promotion of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, the State Secretariat for Migration (3a-12-0495), and the Swiss Federal Office for Health (12.005187). TRS was supported by an Early. Postdoc Mobility Fellowship of the Swiss National Science Foundation, grant no. [P2ZHP3_195191].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Declarations

Ethics approval, accordance and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committees of the Cantons of Zurich (KEK ZH-Nr. 2011-0495) and Bern (EK BE 152/12) Switzerland. Before the assessment, a study team member explained the purpose of the study to each participant and written informed consent was obtained, written informed consent was obtained. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publications

A study team member explained the purpose of the study to each participant and written informed consent for the publication of any associated data was obtained.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, NM. The data are not publicly available to protect the privacy of the research participants with an increased need for privacy protection.

Authors’ contributions

NM collected the data. NM, BW and TS wrote the first draft of the article. NM, MS, US, RB, and AN conceptualized and designed the study. TS and BW conducted the analyses. All authors revised the draft, read, and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

References

- Blackmore, R., Boyle, J. A., Fazel, M., Ranasinha, S., Gray, K. M., Fitzgerald, G., & Spiegel, P. (2020). The prevalence of mental illness in refugees and asylum seekers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS Medicine, 17, e1003337. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsboom, D. (2017). A network theory of mental disorders. World Psychiatry, 16, 5–6. doi: 10.1002/wps.20375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger, J., Stroebe, M. S., Perrig-Chiello, P., Schut, H. A., Spahni, S., Eisma, M. C., & Fried, E. I. (2020). Bereavement or breakup: Differences in networks of depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 267, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.01.157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Schryver, M., Vindevogel, S., Rasmussen, A. E., & Cramer, A. O. J. (2015). Unpacking constructs: A network approach for studying war exposure, daily stressors and post-traumatic stress disorder. Frontiers in Psychology, 6. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epskamp, S., Borsboom, D., & Fried, E. I. (2018). Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: A tutorial paper. Behavior Research Methods, 50, 195–212. doi: 10.3758/s13428-017-0862-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epskamp, S., & Fried, E. I. (2018). A tutorial on regularized partial correlation networks. Psychological Methods, 23, 617–634. doi: 10.1037/met0000167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa, E. B., Cashman, L., Jaycox, L., & Perry, K. (1997). The validation of a self-report measure of posttraumatic stress disorder: The Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale. Psychological Assessment, 9, 445. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.9.4.445 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haslbeck, J. M. B., & Waldorp, L. J. (2018). How well do network models predict observations? On the importance of predictability in network models. Behavior Research Methods, 50, 853–861. doi: 10.3758/s13428-017-0910-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayawickreme, N., Mootoo, C., Fountain, C., Rasmussen, A., Jayawickreme, E., & Bertuccio, R. F. (2017). Post-conflict struggles as networks of problems: A network analysis of trauma, daily stressors and psychological distress among Sri Lankan war survivors. Social Science & Medicine, 190, 119–132. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.08.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, S. S. Y., Liddell, B. J., & Nickerson, A. (2016). The relationship between post-migration stress and psychological disorders in refugees and asylum seekers. Current Psychiatry Reports, 18, 82. doi: 10.1007/s11920-016-0723-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollica, R. F., Caspi-Yavin, Y., Bollini, P., Truong, T., Tor, S., & Lavelle, J. (1992). The harvard trauma questionnaire: Validating a cross-cultural instrument for measuring torture, trauma, and posttraumatic stress disorder in indochinese refugees. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 180, 111–116. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199202000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mootoo, C., Fountain, C., & Rasmussen, A. (2019). Formative psychosocial evaluation using dynamic networks: Trauma, stressors, and distress among Darfur refugees living in Chad. Conflict and Health, 13, 30. doi: 10.1186/s13031-019-0212-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson, A., Byrow, Y., Rasmussen, A., O’Donnell, M., Bryant, R., Murphy, S., … Liddell, B. (2021). Profiles of exposure to potentially traumatic events in refugees living in Australia. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 30, e18. doi: 10.1017/S2045796021000068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe, E. A., & Smart Richman, L. (2009). Perceived discrimination and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 531–554. doi: 10.1037/a0016059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M., & Haslam, N. (2005). Predisplacement and postdisplacement factors associated with mental health of refugees and internally displaced persons: A meta-analysis. JAMA, 294, 602. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.5.602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schick, M., Zumwald, A., Knöpfli, B., Nickerson, A., Bryant, R. A., Schnyder, U., … Morina, N. (2016). Challenging future, challenging past: The relationship of social integration and psychological impairment in traumatized refugees. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 7, 28057. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v7.28057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silove, D., Sinnerbrink, I., Field, A., Manicavasagar, V., & Steel, Z. (1997). Anxiety, depression and PTSD in asylum-seekers: Assocations with pre-migration trauma and post-migration stressors. British Journal of Psychiatry, 170, 351–357. doi: 10.1192/bjp.170.4.351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small, R., Roth, C., Raval, M., Shafiei, T., Korfker, D., Heaman, M., … Gagnon, A. (2014). Immigrant and non-immigrant women’s experiences of maternity care: A systematic and comparative review of studies in five countries. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 14, 152. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steel, Z., Chey, T., Silove, D., Marnane, C., Bryant, R. A., & Van Ommeren, M. (2009). Association of torture and other potentially traumatic events with mental health outcomes among populations exposed to mass conflict and displacement: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA, 302, 537–549. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steel, Z., Silove, D., Brooks, R., Momartin, S., Alzuhairi, B., & Susljik, I. (2006). Impact of immigration detention and temporary protection on the mental health of refugees. British Journal of Psychiatry, 188, 58–64. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.104.007864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strijk, P. J. M., van Meijel, B., & Gamel, C. J. (2011). Health and social needs of traumatized refugees and asylum seekers: An exploratory study: Health and social needs of traumatized refugees and asylum seekers: An exploratory study. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 47, 48–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6163.2010.00270.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart, J., & Nowosad, J. (2020). The influence of premigration trauma exposure and early postmigration stressors on changes in mental health over time among refugees in Australia. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 33, 917–927. doi: 10.1002/jts.22586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, NM. The data are not publicly available to protect the privacy of the research participants with an increased need for privacy protection.