Abstract

Context

Higher levels of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) are associated with increased risk of cancers and higher mortality. Therapies that reduce IGF-1 have considerable appeal as means to prevent recurrence.

Design

Randomized, 3-parallel-arm controlled clinical trial.

Interventions and Outcomes

Cancer survivors with overweight or obesity were randomized to (1) self-directed weight loss (comparison), (2) coach-directed weight loss, or (3) metformin treatment. Main outcomes were changes in IGF-1 and IGF-1:IGFBP3 molar ratio at 6 months. The trial duration was 12 months.

Results

Of the 121 randomized participants, 79% were women, 46% were African Americans, and the mean age was 60 years. At baseline, the average body mass index was 35 kg/m2; mean IGF-1 was 72.9 (SD, 21.7) ng/mL; and mean IGF1:IGFBP3 molar ratio was 0.17 (SD, 0.05). At 6 months, weight changes were -1.0% (P = 0.07), -4.2% (P < 0.0001), and -2.8% (P < 0.0001) in self-directed, coach-directed, and metformin groups, respectively. Compared with the self-directed group, participants in metformin had significant decreases on IGF-1 (mean difference in change: -5.50 ng/mL, P = 0.02) and IGF1:IGFBP3 molar ratio (mean difference in change: -0.0119, P = 0.011) at 3 months. The significant decrease of IGF-1 remained in participants with obesity at 6 months (mean difference in change: -7.2 ng/mL; 95% CI: -13.3 to -1.1), but not in participants with overweight (P for interaction = 0.045). There were no significant differences in changes between the coach-directed and self-directed groups. There were no differences in outcomes at 12 months.

Conclusions

In cancer survivors with obesity, metformin may have a short-term effect on IGF-1 reduction that wanes over time.

Keywords: behavioral weight loss, metformin, insulin-like growth factors, IGF-1, IGFBP3, weight

The ability to diagnose and treat cancer at early stages has led to an increased number of cancer survivors, and this has prompted the study of behavioral and pharmacologic interventions for improving survival and quality of life in cancer survivors. IGF-1 is a biomarker of considerable interest because of its potential role in the pathogenesis of solid tumors, particularly those related to excess weight (1). IGF-1 has been associated with increased risks of several common cancers including breast, colorectal, and prostate cancers (2). Moreover, some studies suggest that among patients with breast cancer, higher IGF-1 levels are associated with higher mortality (3). In the circulation, IGF-1 binds mainly to the major IGF-binding protein, IGF-binding protein 3 (IGFBP3), which is pivotal for circulating IGF bioactivity (2). The increase in molar ratio between IGF-1 and IGFBP3 reflects an increase in free, biologically active IGF-1; therefore, therapies that reduce IGF-1 or IGF1:IGFBP3 molar ratio have considerable appeal as means to prevent cancer in persons without cancer and cancer recurrence among cancer survivors.

Metformin has been associated with a reduced risk of several types of cancer in patients with diabetes (4-6). In addition to its effects on lowering glucose and improving insulin sensitivity (7), preliminary evidence suggests that metformin may decrease circulating levels of IGF-1 and other growth factors (8).

In animal models, high-fat diet feeding induces elevated IGF-1 and decreased IGFBP3 (9) and calorie restriction decreases serum IGF-1 concentrations (6, 7) but the relationship of IGF-1 with adiposity is inconsistent in humans (10-13). Although some trials of weight loss and IGFs have been conducted in young or obese noncancer adults (14-16), data are lacking in patients with history of cancer.

Both metformin and behavioral weight loss are appealing interventions for their beneficial effects in treating other conditions, their widespread use, and their well-documented safety profiles. In this context, we conducted a phase 2, randomized, 3-parallel-arm trial, named SPIRIT, to evaluate the effects of coach-directed behavioral weight loss and metformin treatment, each compared with a self-directed weight loss arm, on cancer-related biomarkers, with primary outcomes of IGF-1 and the IGF-1 to IGFBP3 (IGF1:IGFBP3) molar ratio. By including a behavioral weight loss intervention, our design allowed us to assess the effects of metformin on IGF-1 that are independent from weight loss.

Methods

The SPIRIT trial was reviewed and approved by an institutional review board at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. All participants provided written, informed consent. The trial is registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02431676).

Study population

Participants were cancer survivors with overweight or obesity (ie, body mass index [BMI] ≥ 25 kg/m2). The main inclusion criteria were a self-reported malignant solid tumor diagnosis; completion of required surgical, and/or chemotherapy, and/or radiation curative intent therapy at least 3 months before enrollment; anticipated treatment-free life span of 12 months or longer; and ages 18 years and older. Chemoprophylaxis with tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors for breast cancer in women and anti-LH-releasing hormone (LHRH) therapy for prostate cancer in men was not an exclusion. Participants were required to have regular access to a computer with a reliable internet connection based on self-report. The major exclusion criteria were medication-treated diabetes; nonfasting blood glucose ≥ 200 mg/dL, or glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) ≥ 7%; current or prior regular use of metformin within the past 3 months; and significant renal disease or dysfunction defined as estimated glomerular filtration rate <45 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Participants were recruited from the Baltimore metropolitan area between August 2015 and December 2016 through mass mailing, placement of brochures in physician offices, distribution of flyers in various community settings (eg, health fairs), direct referral from study physicians, word of mouth, advertisement in local newspapers, and online advertising (17).

Randomization and masking

Randomization assignments were computer-generated and stratified according to baseline BMI category (BMI < 30; BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) and race (Black, non-Black) because of potential difference on IGFs by BMI (18) and race (19). Assignments were generated with equal allocation to the 3 study arms within randomly selected block sizes of 3 and 6 using a computerized program by the study statistician. Intervention assignment was not blinded to the trial participants, nor the intervention staff. However, study staff involved in follow-up data collection and laboratory staff involved in laboratory measures were masked to the randomization assignments.

Study groups

The coach-directed behavioral weight loss intervention was remotely delivered by a health coach and based on the remotely delivered intervention in the POWER trial at Johns Hopkins (20). Participants were encouraged to lose 5% of their baseline weight within 6 months and with weight maintenance until the end of the study. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends 5% to 10% of weight loss to produce health benefits, such as improvements in blood pressure, cholesterols, and glucose levels (21). Weight loss as low as 5% is achievable and has been shown to improve many of the adverse effects caused by obesity (22, 23). The participants in this study received weekly telephonic coaching during the first 3 months and monthly for the rest of the study. The coach-directed behavioral weight loss intervention was based on a social-cognitive theoretical framework that drew upon the strengths of various approaches including Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory (24, 25). Specific strategies that were encouraged among the participants included increased physical activity, caloric restriction, self-monitoring (diet, exercise, and weight), goal setting, and problem-solving. Healthways Inc, a disease management company, provided the remote weight loss platform, whereas the trial provided the coaches.

Participants in the metformin arm took up to 2000 mg per day of metformin, which was provided by the study (26). Participants in this arm received medication-related education and counseling from a study staff member immediately following randomization. Dosing was flexible, 2 or 3 times per day with meals for 12 months. Titration of metformin in an open-label fashion occurred as follows, largely based on tolerance at each dose level: (1) start with 500 mg by mouth once daily with breakfast for 7 days or longer if needed; (2) increase metformin to 500 mg by mouth twice daily with breakfast and dinner for 7 days or longer if needed; (3) increase metformin to 1000 mg in the morning and 500 mg in the evening; and (4) increase metformin to 1000 mg twice daily.

Participants in the comparison arm were assigned to self-directed weight loss. These participants met briefly with a weight-loss coach at the time of randomization and, if desired, after the final data collection visit, at 12 months. They also received brochures and a list of recommended Web sites that promoted weight loss.

Data collection

Eligibility, baseline, and follow-up data were collected by telephone and through in-person visits. The enrollment process involved a telephone contact, an in-person visit during which baseline data were collected, and a second in-person visit during which participants were notified of their assigned group. Trained research staff performed the standardized measurements. They measured height once at study entry and measured weights at baseline and 3 follow-up time points (3, 6, and 12 months) using a high-quality, calibrated digital scale, with the participant wearing light, indoor clothes, and no shoes. Blood pressure and fasting blood were collected at baseline and 3 follow-up time points.

Blood samples, frozen and stored at -70°C, were transported to the University of Maryland School of Medicine Pathology Laboratory, where the assays were performed. Plasma IGF-1, IGFBP3, and IL-6 were measured using ELISA (Quantikine; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Fasting lipids, glucose, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), and HbA1c, were measured using Dimension Vista System (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Inc, Newark, DE). Fasting plasma insulin was measured using ADVIA Centaur Insulin assay (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Inc). IGF1 and IGFBP3 were measured at baseline and all 3 follow-ups. Other biomarkers were measured at baseline, 6-month, and 12-month follow-ups as specified in the protocol.

Self-reported baseline data included age, sex, race/ethnicity, education level, and comorbid conditions (eg, diabetes and hypertension). Information on the solid tumor malignancies was also self-reported and included organ of origin, stage of disease at diagnosis if known, and date of completion of treatment(s). Serious adverse events were obtained during in-person follow-up visits. All baseline data were collected before randomization.

Power and sample size

The required sample size for the study was powered for comparing change in IGF-1 at 6 months from baseline between: (1) coach-directed weight loss intervention and self-directed arm and (2) metformin and self-directed arm, respectively, each with 80% power using a 2-sided z-test with α of 0.025. The comparison between the coach-directed and metformin arms was exploratory and not included in sample size and power considerations. Assuming common SD at baseline and 6-month visit of 60 ng/mL (27) and a correlation of 0.90 between IGF-1 measures at baseline and 6 months (28), a total sample of 120 individuals in equal allocation (ie, N = 40 per arm) was deemed sufficient to detect a difference of 17.4 ng/mL or greater in change of IGF-1 over this period for each between arm comparison at the α = 0.025 level.

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome of this trial was the 6-month change in the level of IGF-1. The 2 primary testing contrasts compared the outcomes of coach-directed weight loss arm vs self-directed arm, and the metformin arm vs self-directed arm. The IGF1:IGFBP3 molar ratio was calculated as [IGF1 (ng/mL) × 0.13] / [IGFBP3 (ng/mL) × 0.035]. The 6-month timepoint as the primary outcome assessment was chosen to maximize data collection at the time of the greatest anticipated weight loss and to minimizing a decrease in sample size resulting from censoring of data from potential recurrent cancer or missing data from dropouts. Intervention effects were analyzed using an intention-to-treat approach. Each active intervention arm was compared with the comparison arm using likelihood based mixed effects linear regression models using all available data from all 4 time points (ie, baseline and 3, 6, and 12 months), jointly with the following model specifications.

For the primary analysis model, the mean model for the mixed effects regression was structured to include 2 binary intervention arm indicators (for coach-directed weight loss arm and metformin arm), 3 binary follow-up time indicators (for 3-, 6-, and 12-month follow-up), and the cross-product interaction terms between the group and time indicators (6 interaction terms). The covariance model used a 4 × 4 unstructured covariance matrix to allow different outcome variances and to account for the intra-individual outcome correlations over time. Race and baseline BMI levels, the variables used for stratifying the randomization, were included in the mean model as prespecified except the models for the secondary outcome of BMI where baseline BMI was part of the longitudinal dependent variables. For outcomes such as fasting insulin, HbA1c, IL-6, and hs-CRP, where data were not available at the 3-month visit, the analysis models did not include any independent variables terms related to that visit, and the covariance model used a 3 × 3 unstructured covariance matrix.

Under this model specification, the beta coefficient for an intervention by 6-month visit interaction term estimates the difference of 6-month changes from baseline in mean outcome between that intervention arm and the control arm. For the outcomes of IGF-1 and IGF1:IGFBP3 molar ratio, each of these 2 beta coefficients from the corresponding outcome specific modeling results were evaluated at 2-sided alpha level of 0.025 for statistical significance. For all other analyses, the statistical significance level was set at the conventional level of 2-sided alpha level of 0.05.

We also conducted subgroup analyses to explore for potential differential intervention effects across prespecified subgroups, including sex, race, baseline BMI groups, and baseline IGF-1 level. Statistical significance of these subgroup analyses was evaluated though incorporating appropriate subgroup by intervention by visit interaction terms in the mean model. To explore for intervention effects not mediated through weight change over time, analyses were repeated with additional time dependent weight adjustment in mixed-effects regression analyses.

To evaluate the association between metformin dosing level and the trial outcomes, post hoc exploratory analyses were conducted using actual dosing data within the metformin arm. Race and baseline BMI levels were included as prespecified covariates, and additional analyses with inclusion of time-dependent weight as covariate were conducted to explore association of metformin with the outcomes independent of weight change during the trial period.

The trial emphasized the approach of prevention being far superior to any statistical approaches in addressing missing data, and made every possible effort to keep the occurrences of missing data to the lowest degree possible. To address the missing values, likelihood-based, repeated measures mixed-effects modeling analyses accounting for identified predictors for probability of missing outcome values under the missing at random (MAR) assumption and incorporating within person outcome correlations over time were conducted to form statistical inferences. Sensitivity analysis through multiple imputation based on sensible missing not at random scenarios was conducted to evaluate the robustness of the finding under MAR assumption.

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Study participants

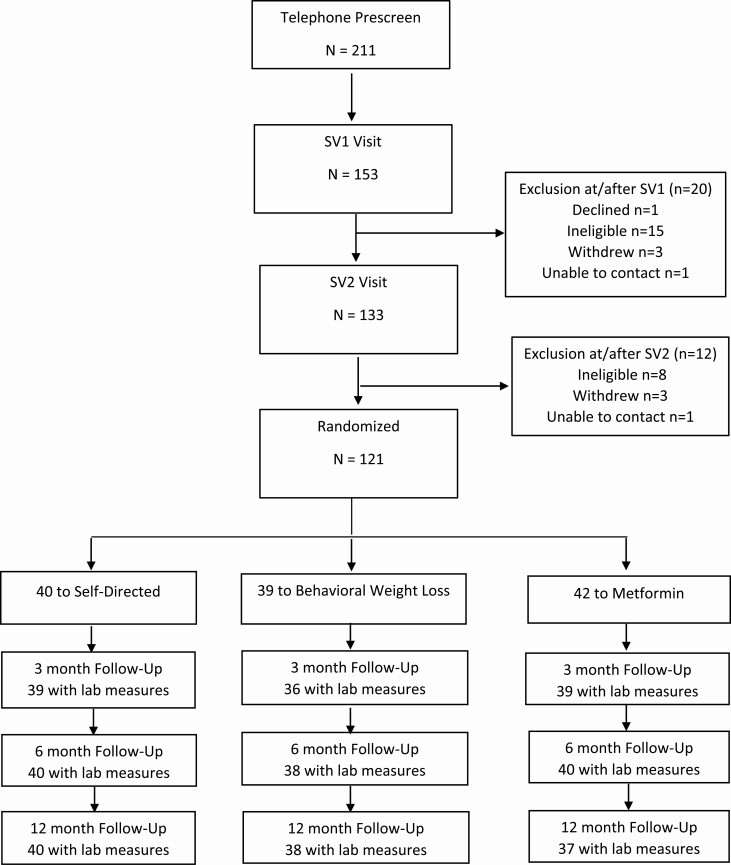

A total of 211 persons expressed interest in the trial; 121 underwent randomization. At 6-month primary outcome assessment time point, 3 participants (2.5%) had missing laboratory data; during the entire study period, the retention rate was more than 95% (Fig. 1). Of the 121 randomized participants, the mean age was ~60 years, 79% were women, and 46% were Black. The most common comorbid conditions were hypertension, arthritis, and prediabetes, based on self-report. The majority of the participants had a history of breast cancer (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Study consort diagram.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Self-directed (n = 40) | Coach-directed (n = 39) | Metformin (n = 42) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 58.8 (8.5) | 60.9 (9.7) | 59.5 (9.0) |

| Female, n (%) | 32 (80.0) | 32 (82.1) | 32 (76.2) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 18 (45.0) | 17 (43.6) | 20 (47.6) |

| Non-Hispanic non-Black | 22 (55.0) | 21 (53.8) | 22 (52.4) |

| Hispanic | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (4.8) |

| Education, n (%) | |||

| High school graduate or less | 4 (10.0) | 8 (20.5) | 8 (19.0) |

| Some college | 13 (32.5) | 5 (12.8) | 9 (21.4) |

| College graduate | 23 (57.5) | 26 (66.7) | 25 (59.5) |

| Selected medical conditions, n (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 13 (32.5) | 13 (33.3) | 18 (42.9) |

| Arthritis | 5 (12.5) | 7 (17.9) | 8 (19.0) |

| Prediabetes | 5 (12.5) | 6 (15.4) | 9 (21.4) |

| High blood cholesterol | 8 (20.0) | 6 (15.4) | 5 (11.9) |

| Cancer type, n (%) | |||

| Breast | 22 (55.0) | 19 (48.7) | 27 (64.3) |

| Prostate | 4 (10.0) | 3 (7.7) | 4 (9.5) |

| Colon | 4 (10.0) | 3 (7.7) | 3 (7.1) |

| Thyroid | 4 (10.0) | 3 (7.7) | 2 (4.8) |

| Endometrial | 2 (0.5) | 3 (7.7) | 2 (4.8) |

| Number of cancers, n (%) | |||

| Only 1 | 37 (92.5) | 34 (87.2) | 37 (88.1) |

| More than 1 | 3 (7.5) | 5 (12.8) | 5 (11.9) |

| Fasting insulin (mU/L) | 16.9 (8.5) | 14.2 (6.9) | 16.4(10.8) |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 99.8 (13.5) | 99.0 (13.6) | 102.9(15.4) |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.7 (0.5) | 5.7(0.6) | 5.7(0.5) |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 188.6 (37.1) | 189.3(37.78) | 177.2(41.0) |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 116.2 (34.7) | 107.7(32.0) | 106.8(35.7) |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 48.4 (11.5) | 58.6(18.6) | 55.0(14.0) |

| Triglycerides cholesterol (mg/dL) | 119.9 (54.9) | 114.5(62.2) | 109.1(47.8) |

| hs-CRP (mg/L) | 6.0 (6.8) | 5.2 (7.3) | 4.6(4.1) |

| IL6 (pg/mL) | 4.6 (2.8) | 3.9(3.0) | 3.4(2.1) |

Data are presented as mean (SD), or n (%).

Abbreviations: HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; hs-CRP, high sensitivity C-reactive protein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein.

Intervention adherence

Participants in the coach-directed weight loss arm had a median call completion of 13 of 15 possible calls in the first 6 months, and 7 of 7 possible calls during the past 6 months of the study. There was a similar high participation rate with weekly login to the study Website with a median of 20 weekly logins of the 26 expected logins during the first 6 months, and 19 weekly logins of the 26 expected logins during months 7 to 12. The median number of weeks with weight tracked was 17 in the first 6 months and 14 for the remainder of the trial. Call completion, weekly logins, and number of weight tracking provided insight into the level of interaction participants had with the study materials.

Eleven participants assigned to the metformin group discontinued metformin during the study period because of cancer recurrence or side effects. Among those who completed metformin, the adherence was high—all adhered to prescribed dose with the median daily dose of 1500 mg over the 12-month intervention period.

Weight change

Average BMI at baseline was 35 kg/m2; as shown in Fig. 2A, at 6 months, the magnitude of changes was -4.2% (95% CI, -5.9 to -2.4) in the coach-directed weight loss arm and -2.8% (95% CI, -4.1 to -1.5) in the metformin arm. At 12 months, no further reduction occurred in the coach-directed intervention arm (mean: -3.4%; 95% CI, -5.2 to -1.6), whereas further reduction was seen in the metformin arm (-3.7%; 95% CI, -5.7 to -1.9). Participants in the self-directed arm had a slight weight loss during the study period (-1.00% at 6 months and -0.63% at 12 months.)

Figure 2.

(A) Percent weight change during study period. (B) Kernel estimates of percent weight change (%) at 6 months by study arm.

At 6 months, 15.0%, 38.6%, and 30% of participants achieved at least 5% of weight loss in the self-directed, coach-directed weight loss, and metformin arms, respectively (Fig. 2B). The corresponding proportions at 12 months were 12.5%, 36.8%, and 35.1%.

Compared with the self-directed group, participants in the coach-directed weight loss arm achieved significant, greater net percent weight reductions: 3.2% and 2.8% at 6-month and 12-month visits, respectively. Participants in the metformin treatment group also achieved significantly greater net percent weight reductions compared with the self-directed group: 1.8% at 6-month and 3.1% at 12-month visits (Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline, within-group changes, and model-based estimates of between-group differences in weight, percent weight, BMI, IGF-1, and IGF-1:IGFBP3 molar ratio at 3, 6, and 12 Months

| Self-directed | Coach-directed | Metformin | Difference in change: coach-directed vs self-directed | Difference in change: Metformin vs self-directed | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight, kg | Baseline | 95.7 (14.83) | 93.8 (13.86) | 97.7 (20.71) | -- | -- |

| ∆3 m | -0.76a | -2.95a | -1.63a | -2.19a | -0.88 | |

| (-1.44 to -0.07) | (-3.98 to -1.92) | (-2.52 to -0.75) | (-3.43 to -0.95) | (-1.99 to 0.24) | ||

| ∆6 m | -0.80 | -3.52a | -2.60a | -2.72a | -1.80a | |

| (-1.73 to 0.12) | (-5.08 to -1.97) | (-3.88 to -1.32) | (-4.53 to -0.91) | (-3.38 to -0.22) | ||

| ∆12 m | -0.43 | -2.72a | -3.32a | -2.30a | -2.89a | |

| (-1.64 to 0.79) | (-4.32 to -1.13) | (-5.10 to -1.54) | (-4.30 to -0.29) | (-5.05 to -0.74) | ||

| % Weight change | ∆3 m | -0.88a | -3.45a | -1.75a | -2.57a | -0.87 |

| (-1.61 to -0.15) | (-4.58 to -2.32) | (-2.58 to -0.92) | (-3.91 to -1.23) | (-1.98 to 0.23) | ||

| ∆6 m | -0.99 | -4.16a | -2.80a | -3.17a | -1.80a | |

| (-2.07 to 0.07) | (-5.95 to -2.38) | (-4.10 to -1.49) | (-5.25 to -1.09) | (-3.49 to -0.11) | ||

| ∆12 m | -0.63 | -3.38a | -3.71a | -2.75a | -3.08a | |

| (-1.94 to 0.69) | (-5.18 to -1.57) | (-5.56 to -1.85) | (-4.98 to -0.52) | (-5.36 to -0.81) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | Baseline | 34.7 (4.93) | 35.3 (4.95) | 35.0 (6.32) | -- | -- |

| ∆3 m | -0.27a | -1.11a | -0.53a | -0.84a | -0.27 | |

| (-0.51 to -0.03) | (-1.48 to -0.74) | (-0.86 to -0.21) | (-1.28 to -0.40) | (-0.67 to 0.14) | ||

| ∆6 m | -0.30 | -1.32a | -0.87a | -1.02a | -0.57a | |

| (-0.63 to 0.03) | (-1.87 to -0.77) | (-1.31 to -0.42) | (-1.66 to -0.38) | (-1.12 to -0.01) | ||

| ∆12 m | -0.17 | -1.04a | -1.15a | -0.87a | -0.98a | |

| (-0.63 to 0.29) | (-1.62 to -0.45) | (-1.77 to -0.53) | (-1.61 to -0.13) | (-1.75 to -0.21) | ||

| IGF-1 (ng/mL) | Baseline | 71.0 (20.32) | 73.3 (21.47) | 74.4 (23.57) | -- | -- |

| ∆3 m | 1.07 | 0.42 | -4.42a | -0.65 | -5.50a | |

| (-2.19 to 4.34) | (-3.29 to 4.13) | (-7.76 to -1.09) | (-5.60 to 4.29) | (-10.16 to -0.83) | ||

| ∆6 m | 2.19 | 3.98 | -2.29 | 1.79 | -4.49 | |

| (-1.43 to 5.81) | (-0.01 to 7.98) | (-6.32 to 1.73) | (-3.60 to 7.18) | (-9.90 to 0.93) | ||

| ∆12 m | 2.15 | 3.50 | 3.52 | 1.34 | 1.37 | |

| (-0.72 to 5.03) | (-1.83 to 8.82) | (-0.02 to 7.06) | (-4.71 to 7.40) | (-3.19 to 5.93) | ||

| IGF1:IGFBP3 molar ratio | Baseline | 0.17 (0.04) | 0.17 (0.06) | 0.18 (0.05) | -- | -- |

| ∆3 m | 0.0066a | 0.0061 | -0.0054 | -0.0005 | -0.0119a | |

| (0.0013-0.0118) | (-0.0039 to 0.0160) | (-0.0129 to 0.0021) | (-0.0117 to 0.0108) | (-0.0211 to -0.0027) | ||

| ∆6 m | 0.0077a | 0.0085 | -0.0006 | 0.0008 | -0.0083 | |

| (0.0021-0.0133) | (-0.0003 to 0.0173) | (-0.0097 to 0.0085) | (-0.0097 to 0.0112) | (-0.0189 to 0.0024) | ||

| ∆12 m | 0.0102a | 0.0065 | 0.0077 | -0.0037 | -0.0025 | |

| (0.0038-0.0160) | (-0.0025 to 0.0155) | (-0.0007 to 0.0161) | (-0.0148 to 0.0074) | (-0.0131 to 0.0081) |

Models adjusted for baseline BMI category (overweight; obese) and race as prespecified. Baseline data are presented as mean (SD); changes from baseline are presented as mean (95% CI).

BMI, body mass index; IGFBP3, IGF-binding protein 3.

a P < 0.05.

Primary and secondary outcomes of IGF1 and IGF1:IGFBP3 molar ratio at 6 and 12 months

At baseline, the mean IGF-1 for all participants was 72.9 (SD, 21.7) ng/mL and was similar in all 3 arms. At the 6-month primary outcome assessment time point, the mean change in IGF-1 was 2.19 (95% CI, -1.43 to 5.81) ng/mL in the self-directed, 3.98 (95% CI, -0.01 to 7.98) ng/mL in the coach-directed weight loss, and -2.29 (95% CI, -6.32 to 1.73) ng/mL in the metformin arm (Table 2; Fig. 3A). Compared with the self-directed arm, the 6-month change of IGF-1 was not significantly different in the coach-directed weight loss arm (mean difference between arms: 1.79 ng/mL; 95% CI, -3.60 to 7.18) nor was in the metformin arm (mean difference between arms: -4.49 ng/mL; 95% CI, -9.90 to 0.93) (Table 2).

Figure 3.

(A) Change in IGF-1 during study period. (B) Change in IGF1/IGFBP3 molar ratio during study period.

The mean IGF-1:IGFBP3 molar ratio at baseline for all participants was 0.17 (SD, 0.05). The mean change in the molar ratio at 6 months was 0.0077 (95% CI, 0.0021-0.0133) in the self-directed, 0.0085 (95% CI, -0.0003 to 0.0173) in the coach-directed weight loss, and -0.0006 (95% CI, -0.0097 to 0.0085) in the metformin arm (Fig. 3B). Compared with the self-directed arm, the 6-month change of this molar ratio was not significantly different in the coach-directed weight loss arm (mean difference between arms: 0.0008; 95% CI, -0.0097 to 0.0112) nor was in the metformin arm (mean difference between arms: -0.0083; 95% CI, -0.0189 to 0.0024) (Table 2).

No significant differences in changes between groups were observed for the secondary outcomes of IGF-1 and IGF1:IGFBP3 molar ratios at 12 months (Table 2).

Given the low number of missing outcome values and high within-person correlations among the outcomes over the study period (pairwise within-person correlations ranged 0.83 to 0.89 for IGF-1 and 0.89 to 0.91 for IGF1:IGFBP3), sensitivity analysis results supported the robustness of trial findings derived under the MAR assumption.

Subgroup analyses of main outcomes

In subgroup analyses exploring potential differential intervention effects, we found participants in the metformin group had significantly decreased IGF-1 at 6 months among those who had obesity at baseline (mean difference between arms: -7.2 ng/mL; 95% CI, -13.3 to -1.1), but not in participants with overweight (mean difference between arms: 5.8 ng/mL; 95% CI, -5.2 to 16.9) (P interaction = 0.045) compared with the self-directed group (Fig. 4). Intervention effects did not significantly differ by sex, race, and baseline IGF-1 at 6-month follow-up. We did not find any significant intervention effect modification by sex, race, baseline BMI, or baseline IGF-1 on IGF1:IGFBP3 molar ratio at 6 months.

Figure 4.

Change in IGF-1 at 6 months by subgroup.

Additional analyses of IGF-1 and IGF1:IGFBP3 molar ratio at 3 months

Because prior studies of metformin tended to be short-term, we also analyzed IGF-1 and IGFBP3 levels at 3 months. The mean change in IGF-1 was 1.07 ng/mL (95% CI, -2.19 to 4.34; P = 0.52) in self-directed, 0.42 ng/mL (95% CI, -3.29 to 4.13; P = 0.82) in coach-directed weight loss, and -4.42 ng/mL (95% CI, -7.76 to -1.09; P = 0.01) in metformin arm at 3 months (Fig. 3A; Table 2). Compared with the self-directed arm, the change of IGF-1 in the metformin arm at 3 months was statistically significant (difference in change between arms, mean: -5.50, 95% CI, -10.16 to -0.83; P = 0.02; Table 2). The change of IGF-1 at 3 months in the metformin arm did not appear to be mediated through weight change. The weight-adjusted net change of IGF-1 in the metformin arm compared with the self-directed arm at 3 months was -5.84 ng/mL (95% CI, -10.48 to -1.21; P = 0.01). Differences between the coach-directed weight loss arm and self-directed arm were not statistically different at 3 months.

At 3 months, the mean change in IGF1:IGFBP3 molar ratio was 0.0066 in self-directed, 0.0061 in coach-directed weight loss, and -0.0054 in the metformin arm (Fig. 3B). Compared with the self-directed group, the net change of IGF-1:IGFBP3 molar ratio in the metformin arm at 3 months was statistically significant (difference in change between arms, mean: -0.0119, 95% CI, -0.0211 to -0.0027; P = 0.011; Table 2). Further adjusting for weight change over time did not affect the results. Differences between the coach-directed weight loss arm and the self-directed arm were not statistically different at 3 months.

Furthermore, an analysis among participants in the metformin arm was conducted to explore the dose-response relationship between metformin dosage and changes in IGF-1 and IGF1:IGFBP3 molar ratio. A significant, linear relationship between metformin dose and IGF-1 change was observed at 3 months. In participants who received average metformin dose of 500 mg/d, 1000 mg/d, 1500 mg/d, and 2000 mg/d, IGF-1 levels decreased by -2.61 (95% CI, -4.64 to -0.57), -4.00 (95% CI, -7.34 to -0.65), -5.38 (95% CI, -10.14 to -0.63), and -6.77 (95% CI, -12.98 to -0.56) ng/mL, respectively, from baseline (all P < 0.05). However, there was no association between metformin dosage and IGF1:IGFBP3 molar ratio.

Additional analysis in participants who completed metformin treatment

There were 11 (of 42) participants assigned to the metformin arm discontinued metformin before the end of the study. In 31 participants who completed metformin treatment, the IGF-1 changes were -4.57 ng/mL (P = 0.04) at 3 months, -2.65 ng/mL (P = 0.33) at 6 months, and 4.5 ng/mL (P = 0.04) at 12 months. The IGF-1/IGFBP3 molar ratio changes were -0.0021 (P = 0.62) at 3 months, 0.0001 (P = 0.98) at 6 months, and 0.013 (P = 0.012) at 12 months.

Other outcomes

Other metabolic biomarkers were measured at baseline and 6 and 12 months. Fasting insulin decreased significantly in the self-directed arm at 6 months (mean change, -2.2 mU/L; 95% CI, -3.7 to -0.8 mU/L; P = 0.004), in the coach-directed weight loss arm at 6 months (mean change, -3.7 mU/L; 95% CI, -5.3 to -2.1; P < 0.0001) and at 12 months (mean change: -2.1 mU/L, 95% CI, -4.1 to -0.1; P = 0.04), and in the metformin arm at 12 months (-5.6 mU/L, 95% CI, -8.9 to -2.4; P = 0.0009). Compared with the self-directed arm, the reductions in coach-directed weight loss arm and metformin arm were not statistically significant. There were no significant changes in fasting glucose, HbA1c, blood pressure, lipids, hs-CRP, and IL-6.

Adverse events

There was no serious adverse event that was related to the study. Over follow-up, 22 hospitalizations were reported (5 in the self-directed group, 5 in the coach-directed weight loss group, and 12 in the metformin group). There were 4 cancer recurrences, 2 in the coach-directed group and 2 in the metformin treatment group. There were no deaths or serious hypoglycemic events. No decline in renal function was observed during the study based on laboratory data from clinical visits.

Discussion

In overweight or obese cancer survivors, both coach-directed behavioral weight loss intervention delivered remotely and metformin treatment decreased bodyweight significantly. Participants who received metformin had significant decreases in IGF1 level and IGF1:IGFBP3 molar ratio at 3 months. The significant decrease of IGF-1 remained in participants with obesity at 6 months but returned to baseline at 12 months. Participants receiving coach-directed weight loss intervention did not have significant changes in IGF1 or IGF1:IGFBP3 ratio. There were no significant changes on other biomarkers, except fasting insulin. Fasting insulin decreased significantly in both the coach-directed weight loss group and the metformin treatment group, consistent with the patterns of weight reduction. The interventions had no significant effect on blood pressure, lipids, fasting glucose, HbA1c, hs-CRP, and IL-6.

Metformin has its primary action on glucose homeostasis through LKB1-dependent activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) (29). Outside of effects on glucose levels, activation of AMPK has generally catabolic and antisynthetic effects, including inhibition of fatty acid and protein synthesis; in the setting of tumorigenesis, AMPK may also more directly inhibit the cell cycle (30). Studies of cancer cell lines and mouse models suggest that metformin may decrease levels of IGF-1 (31). Using human pancreatic cancer cell lines, Karnevi et al. demonstrated that treatment with metformin decreased cell proliferation and IGF-1 signaling, through activation of the AMP-activated protein kinase AMPKThr172 and blocking IGF-1 receptor activation and insulin receptor substrate 1 (32).

In humans, metformin treatment has previously been shown to reduced IGF-1 levels in patients with endometrial cancer after 4 weeks of treatment (6, 33), in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (34), and in healthy men (35). Our findings are consistent with these but extend prior work by suggesting that metformin may have a short-term impact on IGF-1 levels that wanes over time.

Previous studies had inconsistent findings regarding the association between adiposity or weight loss and IGF levels. In a clinical trial of dietary weight loss and exercise in ~400 postmenopausal women, no significant changes in IGF-1 or IGFBP3 were detected in any intervention arm compared with control. However, the IGF1:IGFBP3 molar ratio increased significantly in the reduced-calorie dietary modification group and diet plus exercise groups (8). In a study using samples from the Nurses’ Health Study, a positive association was observed between IGFBP3 and BMI, indicating lower biologically active IGF-1 levels (13). In our study, we did not find any significant effect on IGF-1, IGFBP3, and IGF:IGFBP3 molar ratio in the coach-directed weight loss group, suggesting that modified IGF-1 bioavailability is unlikely to be a major mechanism linking caloric restriction or coach-directed weight loss with obesity-associated cancer risk in humans.

Our study did not find any significant changes in lipids, and other biomarkers except fasting insulin. Although we collected data on cardiovascular risk factors, we did not design the trial to reconfirm the well-established relationship between weight reduction and improvements in the lipid profile and glucose levels. Most patients had good control of their cardiovascular risk factors at baseline. Consequently, nonsignificant relationships should be interpreted cautiously.

Strengths of this trial include a diverse population, with 46% Black participants. Few exclusion criteria also increased the generalizability. Retention was high: the primary outcome was collected in nearly all participants. Importantly, this trial was among the few trials that investigated the effects of metformin beyond 3 months. Our study also has limitations. First, the sample size was modest. The trial may be underpowered. Second, there was no run-in period, and 25% of participants did not continue with metformin. Because metformin causes gastrointestinal side effects (36), it is commonplace for ~20% to 25% of persons to discontinue metformin. Nonetheless, adherence to metformin was high in participants who had ever taken metformin. Third, solid tumor diagnosis was based on self-reported information, which may differ by education level and cognitive function. Given the mean age of the participants, a formal cognitive assessment (e.g., Mini-Mental State Examination) may be beneficial. Finally, because of the requirement of internet access, participants had higher education with 60% college graduates.

In conclusion, IGF1 and IGF1:IGFBP3 molar ratio did not change after behavioral weight loss intervention in cancer survivors. Metformin reduced IGF-1 and IGF1:IGFBP3 molar ratio significantly at 3 to 6 months, but levels returned to baseline at 1 year. Additional studies of metformin and behavioral weight loss are warranted to understand their effects on other cancer-related biomarkers and potentially clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participants and ProHealth staff for their contributions to the SPIRIT trial.

Funding: This project was supported by the Maryland Cigarette Restitution Fund and Johns Hopkins Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center. H.-C.Y. and N.K. were also supported in part by the National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Centers Support Grant (5P30CA006973).

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02431676

Conflict of Interest: Healthways, Inc., developed the Website for the original POWER trial in collaboration with Johns Hopkins investigators (L.J.A., A.T.D., G.J.J.). On the basis of POWER trial results, Healthways developed and commercialized a weight-loss intervention program called Innergy. This project used the Innergy Website to deliver the weight loss intervention. Under an agreement with Healthways, Johns Hopkins faculty (L.J.A., A.T.D., G.J.J.) monitored the Innergy program’s content and process (staffing, training, and counseling) and outcomes (engagement and weight loss) to ensure consistency with the original POWER Trial. Johns Hopkins received fees for these services and faculty members (L.J.A., A.T.D., G.J.J.) who participated in the consulting services receive a portion of these fees. Johns Hopkins receives royalty on sales of the Innergy program. After completion of this project, Healthways sold the Innergy platform to Sharecare, which ended the relationship with Johns Hopkins. N.M.M. is co-inventor of virtual diabetes prevention program technology; under a license agreement between Johns Hopkins HealthCare Solutions and the Johns Hopkins University, N.M.M. and the University are entitled to royalty distributions related to this technology. This technology/intervention is not discussed in this publication. This arrangement has been reviewed and approved by the Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AMPK

AMP-activated protein kinase

- BMI

body mass index

- HbA1c

glycated hemoglobin

- hs-CRP

high sensitivity C-reactive protein

- IGF-1

insulin-like growth factors-1

- IGFBP3

IGF-binding protein 3

- LHRH

LH-releasing hormone

- MAR

missing at random.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Renehan AG, Zwahlen M, Egger M. Adiposity and cancer risk: new mechanistic insights from epidemiology. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15(8):484-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Renehan AG, Zwahlen M, Minder C, O’Dwyer ST, Shalet SM, Egger M. Insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I, IGF binding protein-3, and cancer risk: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Lancet. 2004;363(9418):1346-1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Duggan C, Wang CY, Neuhouser ML, et al. Associations of insulin-like growth factor and insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 with mortality in women with breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2013;132(5):1191-1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Decensi A, Puntoni M, Goodwin P, et al. Metformin and cancer risk in diabetic patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2010;3(11):1451-1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Libby G, Donnelly LA, Donnan PT, Alessi DR, Morris AD, Evans JM. New users of metformin are at low risk of incident cancer: a cohort study among people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(9):1620-1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mitsuhashi A, Kiyokawa T, Sato Y, Shozu M. Effects of metformin on endometrial cancer cell growth in vivo: a preoperative prospective trial. Cancer. 2014;120(19):2986-2995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gallagher EJ, LeRoith D. Diabetes, cancer, and metformin: connections of metabolism and cell proliferation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1243:54-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Memmott RM, Mercado JR, Maier CR, Kawabata S, Fox SD, Dennis PA. Metformin prevents tobacco carcinogen–induced lung tumorigenesis. Cancer Prev Res. 2010;3(9):1066-1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Guerra-Cantera S, Frago LM, Jiménez-Hernaiz M, et al. Impact of long-term HFD intake on the peripheral and central IGF system in male and female mice. Metabolites. 2020;10(11):462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lukanova A, Söderberg S, Stattin P, et al. Nonlinear relationship of insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I and IGF-I/IGF-binding protein-3 ratio with indices of adiposity and plasma insulin concentrations (Sweden). Cancer Causes Control. 2002;13(6):509-516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schoen RE, Schragin J, Weissfeld JL, et al. Lack of association between adipose tissue distribution and IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 in men and women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11(6):581-586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Allen NE, Appleby PN, Kaaks R, Rinaldi S, Davey GK, Key TJ. Lifestyle determinants of serum insulin-like growth-factor-I (IGF-I), C-peptide and hormone binding protein levels in British women. Cancer Causes Control. 2003;14(1):65-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Holmes MD, Pollak MN, Hankinson SE. Lifestyle correlates of plasma insulin-like growth factor I and insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3 concentrations. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11(9):862-867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fontana L, Villareal DT, Das SK, et al. ; CALERIE Study Group . Effects of 2-year calorie restriction on circulating levels of IGF-1, IGF-binding proteins and cortisol in nonobese men and women: a randomized clinical trial. Aging Cell. 2016;15(1):22-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mason C, Xiao L, Duggan C, et al. Effects of dietary weight loss and exercise on insulin-like growth factor-I and insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-3 in postmenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22(8):1457-1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Harvie MN, Pegington M, Mattson MP, et al. The effects of intermittent or continuous energy restriction on weight loss and metabolic disease risk markers: a randomized trial in young overweight women. Int J Obes (Lond). 2011;35(5):714-727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Juraschek SP, Plante TB, Charleston J, et al. Use of online recruitment strategies in a randomized trial of cancer survivors. Clin Trials. 2018;15(2):130-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Crowe FL, Key TJ, Allen NE, et al. A cross-sectional analysis of the associations between adult height, BMI and serum concentrations of IGF-I and IGFBP-1 -2 and -3 in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition (EPIC). Ann Hum Biol. 2011;38(2):194-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Berrigan D, Potischman N, Dodd KW, et al. Race/ethnic variation in serum levels of IGF-I and IGFBP-3 in US adults. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2009;19(2):146-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Appel LJ, Clark JM, Yeh HC, et al. Comparative effectiveness of weight-loss interventions in clinical practice. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(21):1959-1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Losing Weight. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published August 17, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/losing_weight/index.html. Accessed March 13, 2021.

- 22. Blackburn G. Effect of degree of weight loss on health benefits. Obes Res. 1995;3 Suppl 2:211s-216s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Donnelly JE, Blair SN, Jakicic JM, Manore MM, Rankin JW, Smith BK; American College of Sports Medicine . American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Appropriate physical activity intervention strategies for weight loss and prevention of weight regain for adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(2):459-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Miller WR, Rollnick S.. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People to Change Addictive Behavior. 1st ed. New York: Guilford Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Physical Activity. Physical Activity | Healthy People 2020. Accessed March 13, 2021. http://healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/overview.aspx?topicid=33. Published October 8, 2020.

- 26. Bristol-Myers Squibb Company. GLUCOPHAGE® (metformin hydrochloride tablets) and GLUCOPHAGE® XR (metformin hydrochloride extended-release tablets). 2017. https://packageinserts.bms.com/pi/pi_glucophage_xr.pdf. Accessed August 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schernhammer ES, Giobbie-Hurder A, Gantman K, et al. A randomized controlled trial of oral melatonin supplementation and breast cancer biomarkers. Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23(4):609-616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rosario PW. Normal values of serum IGF-1 in adults: results from a Brazilian population. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2010;54(5):477-481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shaw RJ, Lamia KA, Vasquez D, et al. The kinase LKB1 mediates glucose homeostasis in liver and therapeutic effects of metformin. Science. 2005;310(5754):1642-1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hardie DG, Ross FA, Hawley SA. AMP-activated protein kinase: a target for drugs both ancient and modern. Chem Biol. 2012;19(10):1222-1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rizos CV, Elisaf MS. Metformin and cancer. Eur J Pharmacol. 2013;705(1-3):96-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Karnevi E, Said K, Andersson R, Rosendahl AH. Metformin-mediated growth inhibition involves suppression of the IGF-I receptor signalling pathway in human pancreatic cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cai D, Sun H, Qi Y, Zhao X, Feng M, Wu X. Insulin-like growth factor 1/mammalian target of rapamycin and AMP-activated protein kinase signaling involved in the effects of metformin in the human endometrial cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2016;26(9):1667-1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Berker B, Emral R, Demirel C, Corapcioglu D, Unlu C, Kose K. Increased insulin-like growth factor-I levels in women with polycystic ovary syndrome, and beneficial effects of metformin therapy. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2004;19(3):125-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fruehwald-Schultes B, Oltmanns KM, Toschek B, et al. Short-term treatment with metformin decreases serum leptin concentration without affecting body weight and body fat content in normal-weight healthy men. Metabolism. 2002;51(4):531-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bouchoucha M, Uzzan B, Cohen R. Metformin and digestive disorders. Diabetes Metab. 2011;37(2):90-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.