Abstract

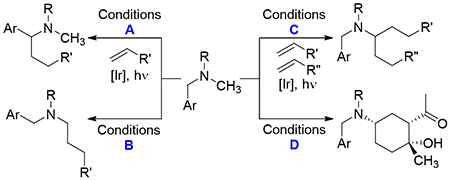

Photocatalytic α-functionalization of amines provides a mild and atom economical means to synthesize α-branched amines. Prior examples featured symmetrical or electronically biased substrates. Here we report a controllable α-functionalization of amines in which regioselectivity can be tuned with minor changes to the reaction conditions.

Graphical Abstract

Carbon-centered radicals react with olefins, halogenating reagents, (hetero)arenes, other radicals, and transition metals.1 Addition reactions involving carbon-centered radicals are often rapid and highly exothermic and therefore of high synthetic value.2 However, controlling the site of radical generation can lack atom economy or flexibility. Here we describe a photocatalytic α-amino functionalization reaction that features precise control of regiochemistry and product distribution through subtle changes to the reaction conditions.

Traditional approaches to generate radicals require homolysis of C-halide or C-O bonds or involve decarboxylation.3 Such methods control the regioselectivity of radical formation but require pre-functionalized reagents. Atom economical approaches to radical generation rely on abstraction of hydrogen atoms. In this setting, selectivity cleaving one of many C-H bonds presents a formidable challenge. Substrate tethering, as in the Hofmann-Löffler-Freytag reaction leverages the propensity of N-centered radicals to participate in 1,5-H atom transfer reactions.4 Alternatively, the photocatalytic fluorination of benzylic positions provides a representative example of abstracting the weakest C-H bond.5 In another approach, polarity matching enables electron deficient aminium radicals to abstract the most electron rich hydrogen atom.6 Notably, these conditions are not generally controllable – i.e., it is not possible to change the site of radical generation by altering reaction conditions, catalysts or reagents.

Photocatalytic strategies provide mild methods to form and functionalize carbon-centered radicals.7 For example, the Pandey and Reiser groups8 and the Yoon group9 independently described the formation of α-ainino radicals 2 derived from tetrahydroisoquinolines in the presence of a Ru(bpy)32+ photocatalyst (Scheme 1A). Similarly, Nicewicz showed that symmetrical carbamates could be alkylated with electron poor olefins10 in the presence of an organic photocatalyst (Scheme 2B).11 Both of these transformations proceed in good yields and with complete selectivity for functionalization adjacent to nitrogen. Nonetheless, existing technology only provides access to single regioisomeric products; the benzylic radical 2 is highly favored relative to the non-benzylic position while the Nicewicz substrates (4) were symmetrical.

Scheme 1.

Photocatalytic α-Functionalization of Amines

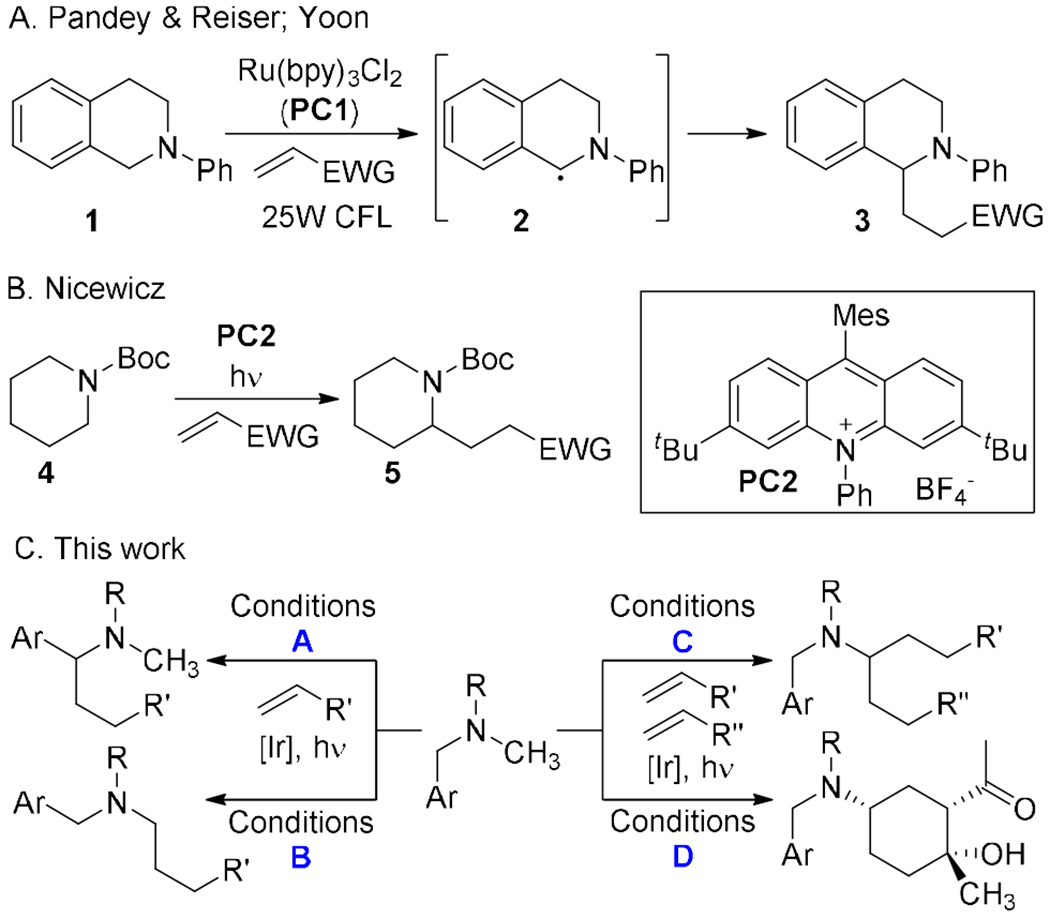

Scheme 2. Proposed reaction mechanism and computational studies.

All energies are in kcal/mol. Gibbs free energies of TS1 and TS2 are with respect to 6Bn• and 6Me•, respectively.

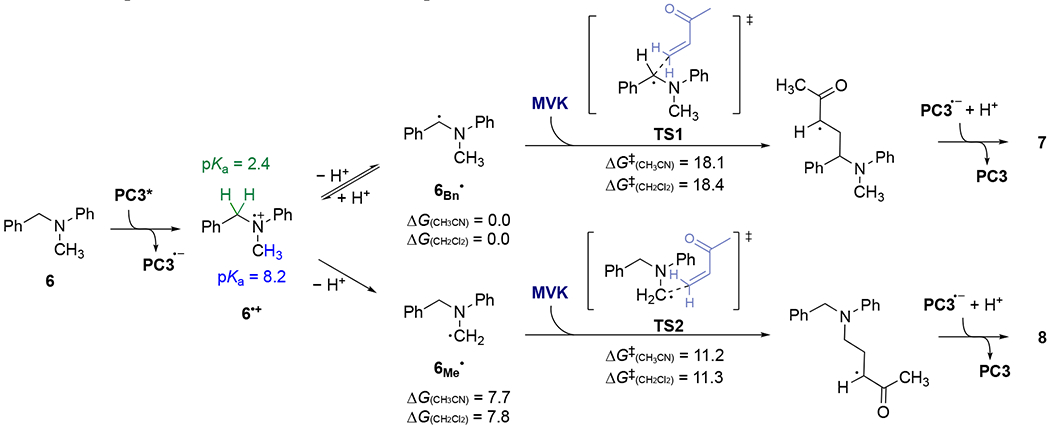

In connection with our recent study on photocatalytic functionalization of indolines,12 we questioned whether it would be possible to control the regioselectivity of α-functionalization of non-symmetrical amines. 13 To address this question, N-benzyl-N-methyl aniline (6) and methyl vinyl ketone (MVK) were irradiated in the presence of several photocatalysts under a variety of reaction conditions. Key findings are highlighted in Table 1, while a more detailed summary is provided in the SI. As expected, the benzyl-functionalized product 7 was obtained cleanly in the presence of iridium photocatalyst PC3. Surprisingly, however, changing the solvent to acetonitrile resulted in a complete switch to the methyl-functionalized product 8 (entry 2). Trifluoroacetic acid switched the selectivity back to the benzylic position (entry 3), whereas DBU promoted functionalization of the methyl group and improved the yield, perhaps due to increased catalyst life-time (entry 4).14 Addition of excess MVK under the DBU conditions provided the double-alkylated product 9 in high selectivity (entry 5). Finally, use of a stronger base, K3PO4, yielded the cyclized aldol product 10 as a single observable diastereomer.

Table 1.

Functionalization of N-Benzyl-N-methyl Aniline.

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | equiv MVK | solv. | add. | isolated yield (%) | |||

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| 1 | 3 | CH2Cl2 | -- | 74 | |||

| 2 | 3 | CH3CN | -- | 70 | |||

| 3 | 3 | CH3CN | TFA | 49 | |||

| 4 | 1.1 | CH3CN | DBU | 84 | |||

| 5 | 3 | CH3CN | DBU | 76 | <5 | ||

| 6 | 3 | CH3CN | K3PO4 | <5 | 70 | ||

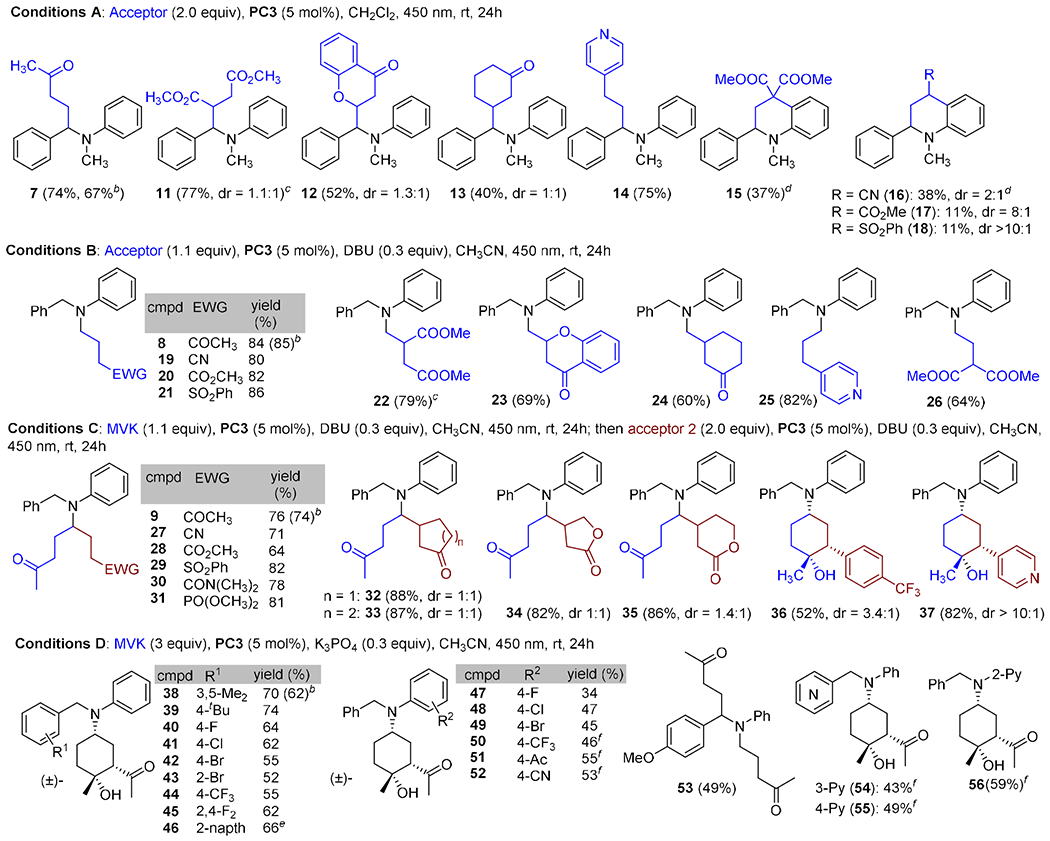

Slight modification of the reaction conditions could controllably give four distinct products in good yield and selectivity. To explore the generality of these addition reactions, we evaluated combinations of several amines and electron-deficient olefins (Table 2). Under Conditions A, which favor benzylic functionalization, dimethyl maleate, chromone and cyclohexanone reacted cleanly (11-13). Additionally, 4-vinyl pyridine added with complete selectivity (14). By contrast, a methylidene malonate and several mono-activated olefins provided the cyclized products 15-18 in modest yield. We attempted to intercept the intermediate radicals with a hydrogen atom donor, but surprisingly, t-BuSH actually increased the yield of cyclized products 15 and 16.

Table 2.

Photochemical α-Functionalization of Aminesa

|

Reaction on a 0.1 mmol scale, 0.05 M.

Reaction on a 2.5 mmol scale. See Supporting Information for details.

From Z-dimethyl maleate.

t-BuSH (1.5 equiv) included in reaction mixture.

2-Naphthylmethyl.

Ir(dF(CF3)ppy)2(dtbbpy)PF6 was used.

Functionalization of the N-methyl group proved to be rather general (Conditions B). The N-methyl group added to olefins activated with a nitrile, ester or sulfone in high yield (19-21). Similarly, dimethyl maleate, cyclic olefins, vinyl pyridine, and a 1,1-diactivated olefins were excellent substrates (22-26). Conditions C were identified to provide difunctionalized products. Rather than forming symmetrical products, the N-methyl group was first mono-functionalized with 1.1 equiv MVK, then irradiated in the presence of 2.0 equiv of a second olefin. In this way, nitrile, ester, sulfone, amide and phosphonate products were formed in good yield (27-31). Addition to cyclic olefins provided adducts 32-35 as mixtures of diastereomers. Under these conditions, additions to vinyl (hetero)arenes formed the cyclic adducts 36 and 37 in moderate to good diastereoselectivity.

Conditions D provided an opportunity to evaluate the impact of substitution on the N-benzyl and N-phenyl rings. The addition/cyclization was generally insensitive to substitution on the benzyl ring. Mono-substitution at all positions was tolerated, as was di-substitution (38-46). Electron-withdrawing groups and mildly electron-releasing groups provided the cyclized products in similar yields as single observed diastereomers. A more strongly electron-donating methoxy group altered the regioselectivity of the reaction such that both the benzylic and methyl positions were functionalized (53). Substitution on the N-phenyl ring favored electron-withdrawing groups, as products 47-52 were formed in good yield. A substrate derived from p-anisidine only provided mono-functionalization. However, heterocycles could be introduced at either position, as illustrated by pyridines 54-56. For each set of conditions (A – D), similar yields were observed on a 20 mg and 500 mg scale.

|

|

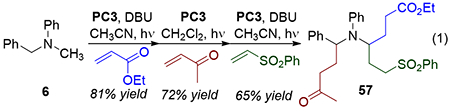

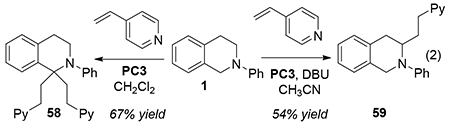

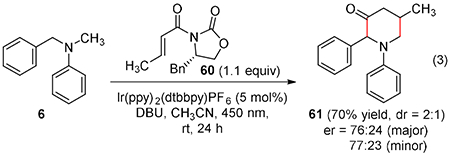

By iteratively alkylating under different conditions, tri-functionalized products could be obtained. For example, substrate 6 could be alkylated at the methyl position with ethyl acrylate, followed by benzyl functionalization with MVK and a final addition of a vinyl sulfone in CH3CN to form the adduct 57 in good overall yield (eq 1). We also returned to tetrahydroisoquinoline 1 and found that Conditions A fully substituted the benzylic position to give 58. By contrast, Conditions B again switched the selectivity to favor addition at the non-stabilized position (59, eq 2).

|

To develop an asymmetric version of the addition reaction, oxazolidinone 60 was irradiated under conditions that favor N-methyl functionalization (eq 3). Remarkably, the [3+3] adduct 61 was isolated in good yield. While the diastereomeric and enantiomeric ratios are modest, the results provide proof-of-concept for asymmetric synthesis. In this condensation, initial 1,4-addition is likely followed by a [1,5]-hydrogen abstraction to form a benzylic radical. Reduction and cyclization with expulsion of the Evans auxiliary would account for the product.

|

|

|

The overall mechanism of α-amino functionalization likely follows the sequence outlined by Pandey, Reiser8 and Yoon9. Irradiation of the Ir catalyst generates an excited state complex that is capable of accepting an electron from the amine substrate to form an ammonium radical cation. Loss of a proton generates a neutral α-amino radical (see 2) that can participate in Giese-type additions to activated olefins.10

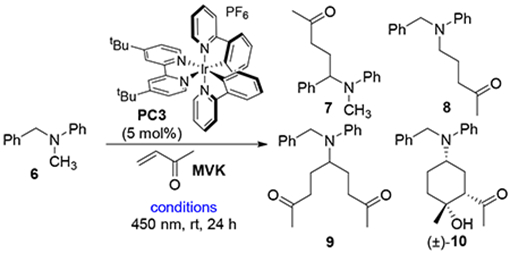

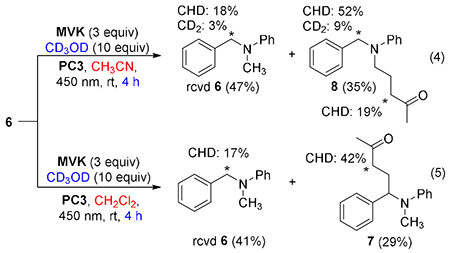

To gain more insight into the impact of solvent on regioselectivity,15 we performed deuterium labeling studies and initial computational evaluation. Addition of CD3OD (10 equiv) to the reaction mixture did not affect yield or selectivity but allowed us to monitor protonation events. Thus, we ran the reaction to partial conversion in acetonitrile (eq 4). Functionalization occurred at the N-methyl position, but the isolated product and recovered starting material showed substantial deuterium incorporation at the benzylic position. In methylene chloride, the recovered starting material showed partial deuteration, while little deuterium incorporation was observed at the benzylic position in the isolated product (eq 5). Control experiments revealed extensive deuterium incorporation in the absence of MVK (see SI). In neither case was deuterium observed at the methyl position. Taken together, the isotope labeling experiments indicate that activation of the benzylic site is reversible whereas activation of the methyl site is irreversible. Related reactions with added D2O revealed similar levels of deuteration, indicating that the label is likely introduced as D+ rather than D radical.

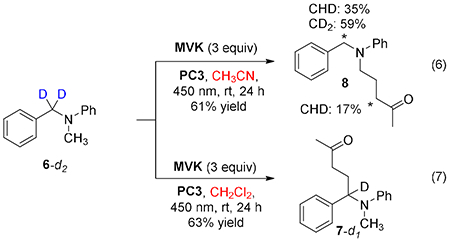

Substrate 6-d2, which is labeled at the benzylic position, reacted in acetonitrile to give the methyl-functionalized product 8, as expected (eq 6). The majority of the deuterium label remained at the benzylic position, while some deuterium label was noted alpha to the ketone, likely a consequence of 1,5-hydrogen atom transfer. In methylene chloride solvent, the expected benzylic functionalization was obtained without loss of deuterium at the benzylic position (eq 7). Deuterium was not observed adjacent to the ketone, which we attribute to exchange with adventitious water (all reactions performed with solvents stored on the benchtop). Critically, in neither case was deuterium observed at the N-methyl position, ruling out equilibration between the benzylic and methyl radicals via intra- or intermolecular H-atom transfer in either solvent.

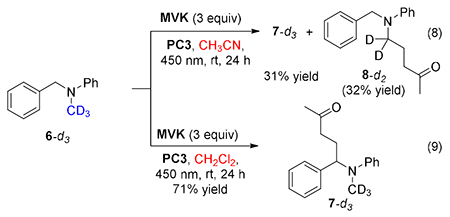

Several insights were obtained from the substrate with a deuterated N-methyl group (6-d3). In acetonitrile, selectivity was erased, such that the benzyl functionalized product 7-d3 and the methyl functionalized product 8-d2 were obtained in equal quantities (eq 8). The change in selectivity is a reflection of a kinetic isotope effect in the methyl-functionalization and indicates that formation of a radical at this position could be rate-limiting. In methylene chloride, clean benzylic functionalization was observed with no loss of the deuterium label (eq 9).

The data support a scenario in which both the benzylic and methyl radicals are formed in acetonitrile, but the methyl radical participates in the Giese addition more rapidly.16 Computation of the reaction energy profile at the M06-2X/6-311++G(d,p), SMD(acetonitrile) // M06-2X/6-31+G(d) level of theory partially supports this interpretation (Scheme 2). The benzylic radical (6Bn•) is more stable than the methyl radical (6Me•) by 7.7 kcal/mol. However, the methyl radical has a lower barrier for addition to MVK than the benzylic radical by 6.9 kcal/mol (11.2 vs 18.1 kcal/mol). The simplest mechanism for reversible activation of the benzylic position involves simple proton transfer (Scheme 2). Protonation of the C-centered radical 6Bn• may appear counterintuitive, but it is simply the microscope reverse of deprotonation of the amine radical cation 6•+. DFT calculations indicate that the pKa of the N-benzyl and N-methyl C–H bonds in 6•+ are 2.4 and 8.2, respectively,17 implying that the more acidic benzylic C–H is susceptible to reversible protonation/deprotonation. This model suggests that in acetonitrile, 1,4-addition of 6Me• to electron-poor olefins is fast relative to reversion to the amine radical cation. In this context, the result in eq 5 provides a tantalizing clue regarding the different outcome in methylene chloride. We observed approximately 20% D incorporation in the recovered starting material, but <5% deuteration at the benzylic position in the product (7). This result indicates that in methylene chloride, the relative energy barriers for 1,4-addition of 6Bn• to olefins vs. protonation back to 6•+ now favor Giese addition. It is surmised that the more polar acetonitrile facilitates proton transfer by stabilizing the charged transition states, because the computed barriers to Giese additions are not substantially different in the different solvents (Scheme 2).18 Ongoing work seeks to understand these effects more completely and probe their generality. In the meantime, the protocols described herein provide convenient and controllable means to access four different product classes from the same starting materials.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Funding from the Welch Foundation (I-1612), NIH (R01 CA216863) and NSF (CHE-1654122, P.L.). DFT calculations were performed at the Center for Research Computing at the University of Pittsburgh and the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE) supported by the National Science Foundation grant number ACI-1548562.

Footnotes

This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.” Complete experimental and computational methods. Characterization data for all new compounds.

The authors declare no competing financial interests. .

REFERENCES

- (1).(a) Rowlands GJ Radicals in organic synthesis. Part 1. Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 8603–8655. [Google Scholar]; (b) Studer A; Curran DP Catalysis of radical reactions: A radical chemistry perspective. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2016, 55, 58–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Yan M; Lo JC; Edwards JT; Baran PS Radicals: Reactive intermediates with translational potential. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 12692–12714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).(a) Romero KJ; Galliher MS; Pratt DA; Stephenson CRJ Radicals in natural product synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev 2018, 47, 7851–7866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Smith JM; Harwood SJ; Baran PS Radical retrosynthesis. Accts. Chem. Res 2018, 51, 1807–1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Pitre SP; Weires NA; Overman LE Forging C(sp3)–C(sp3) bonds with carbon-centered radicals in the synthesis of complex molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 2800–2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).(a) Johnson RG; Ingham RK The degradation of carboxylic acid salts by means of halogen - the Hunsdiecker reaction. Chem. Rev 1956, 56, 219–269. [Google Scholar]; (b) Barton DHR; McCombie SW A new method for the deoxygenation of secondary alcohols. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin 11975, 1574–1585. [Google Scholar]; (c) Gansäuer A; Pierobon M; Bluhm H Catalytic, highly regio- and chemoselective generation of radicals from epoxides: Titanocene dichloride as an electron transfer catalyst in transition metal catalyzed radical reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 1998, 37, 101–103. [Google Scholar]; (d) Zard SZ, Xanthates and related derivatives as radical precursors. In Encyclopedia of radicals in chemistry, biology and materials, Chatgilialoglu C; Studer A, Eds. 2012. [Google Scholar]; (e) Zuo Z; Ahneman DT; Chu L; Terrett JA; Doyle AG; MacMillan DWC Merging photoredox with nickel catalysis: Coupling of α-carboxyl sp3-carbons with aryl halides. Science 2014, 345, 437–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Nawrat CC; Jamison CR; Slutskyy Y; MacMillan DWC; Overman LE Oxalates as activating groups for alcohols in visible light photoredox catalysis: Formation of quaternary centers by redox-neutral fragment coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 11270–11273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Xuan J; Zhang Z-G; Xiao W-J Visible-light-induced decarboxylative functionalization of carboxylic acids and their derivatives. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2015, 54, 15632–15641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Qin T; Cornella J; Li C; Malins LR; Edwards JT; Kawamura S; Maxwell BD; Eastgate MD; Baran PS A general alkyl-alkyl cross-coupling enabled by redox-active esters and alkylzinc reagents. Science 2016, 352, 801–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).(a) Wolff ME Cyclization of N-halogenated amines (the Hofmann-Löffler reaction). Chem. Rev 1963, 63, 55–64; [Google Scholar]; (b) Chen K; Richter JM; Baran PS 1,3-Diol synthesis via controlled, radical-mediated C–H functionalization. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 7247–7249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Xia J-B; Zhu C; Chen C Visible light-promoted metal-free C–H activation: Diarylketone-catalyzed selective benzylic mono- and difluorination. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 17494–17500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Le C; Liang Y; Evans RW; Li X; MacMillan DWC Selective sp3 C–H alkylation via polarity-match-based cross-coupling. Nature 2017, 547, 79–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).(a) Tucker JW; Stephenson CRJ Shining light on photoredox catalysis: Theory and synthetic applications. J. Org. Chem 2012, 77, 1617–1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Prier CK; Rankic DA; MacMillan DWC Visible light photoredox catalysis with transition metal complexes: Applications in organic synthesis. Chem. Rev 2013, 113, 5322–5363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Romero NA; Nicewicz DA Organic photoredox catalysis. Chem. Rev 2016, 116, 10075–10166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Matsui JK; Lang SB; Heitz DR; Molander GA Photoredox-mediated routes to radicals: The value of catalytic radical generation in synthetic methods development. ACS Catalysis 2017, 7, 2563–2575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Kohls P; Jadhav D; Pandey G; Reiser O Visible light photoredox catalysis: Generation and addition of N-aryltetrahydroisoquin-oline-derived α-amino radicals to Michael acceptors. Org. Lett 2012, 14, 672–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Ruiz Espelt L; Wiensch EM; Yoon TP Brønsted acid co-catalysts in photocatalytic radical addition of α-amino C–H bonds across Michael acceptors. J. Org. Chem 2013, 78, 4107–4114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ruiz Espelt L; McPherson IS; Wiensch EM; Yoon TP Enantioselective conjugate additions of α-amino radicals via cooperative photoredox and lewis acid catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 2452–2455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Giese B Formation of CC bonds by addition of free radicals to alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 1983, 22, 753–764. [Google Scholar]

- (11).(a) McManus JB; Onuska NPR; Nicewicz DA Generation and alkylation of α-carbamyl radicals via organic photoredox catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 9056–9060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) McManus JB; Onuska NPR; Jeffreys MS; Goodwin NC; Nicewicz DA Site-selective C–H alkylation of piperazine substrates via organic photoredox catalysis. Org. Lett 2020, 22, 679–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Panda S; Ready JM Tandem allylation/1,2-boronate rearrangement for the asymmetric synthesis of indolines with adjacent quaternary stereocenters. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 13242–13252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Selected α-amino functionalization methods:; (a) Miyake Y; Ashida Y; Nakajima K; Nishibayashi Y Visible-light-mediated addition of α-aminoalkyl radicals generated from α-silylamines to α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds. Chemical Commun. 2012, 48, 6966–6968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hwang JY; Ji AY; Lee SH; Kang EJ Redox-selective iron catalysis for α-amino C–H bond functionalization via aerobic oxidation. Org. Lett 2020, 22, 16–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Joe CL; Doyle AG Direct acylation of C(sp3)–H bonds enabled by nickel and photoredox catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2016, 55, 4040–4043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Ahneman DT; Doyle AG C–H functionalization of amines with aryl halides by nickel-photoredox catalysis. Chem. Sci 2016, 7, 7002–7006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Trowbridge A; Reich D; Gaunt MJ Multicomponent synthesis of tertiary alkylamines by photocatalytic olefin-hydroaminoalkylation. Nature 2018, 561, 522–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Ye J; Kalvet I; Schoenebeck F; Rovis T Direct α-alkylation of primary aliphatic amines enabled by CO2 and electrostatics. Nat. Chem 2018, 10, 1037–1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Ashley MA; Yamauchi C; Chu JCK; Otsuka S; Yorimitsu H; Rovis T Photoredox-catalyzed site-selective α-C(sp3)–H alkylation of primary amine derivatives. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2019, 58, 4002–4006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).(a) Devery Iii JJ; Douglas JJ; Nguyen JD; Cole KP; Flowers Ii RA; Stephenson CRJ: Ligand functionalization as a deactivation pathway in a fac-Ir(ppy)3-mediated radical addition. Chem. Sci 2015, 6, 537–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Föll T; Rehbein J; Reiser O: Ir(ppy)3-catalyzed, visible-light-mediated reaction of α-chloro cinnamates with enol acetates: An apparent halogen paradox. Org. Lett 2018. 20. 5794–5798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).(a) Eberson L; Helgee B Electrolytic substitution reactions. IX. Anodic cyanation of aromatic ethers and amines in emulsions with the aid of phase transfer agents. Acta Chem. Scand., Ser. B 1975. B29. 451–456. [Google Scholar]; (b) Lewis FD; Ho TI; Simpson JT Photochemical addition of tertiary amines to stilbene. Free-radical and electron-transfer mechanisms for amine oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1982. 104. 1924–1929. [Google Scholar]; (c) Sankararaman S; Haney WA; Kochi JK Annihilation of aromatic cation radicals by ion-pair and radical pair collapse. Unusual solvent and salt effects in the competition for aromatic substitution. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1987. 109. 7824–7838. [Google Scholar]

- (16).The Yoon group showed that acids accelerate the 1,4-addition step, which likely renders the C-H cleavage rate-determining (ref 9). Consistent with this proposal, addition of TFA reversed the selectivity in acetonitrile (see Table 1).

- (17).pKa values were calculated using DFT-calculated energies of 6•+, 6Bn•, and 6Me• in water using the SMD implicit solvation model and the free energy of proton in aqueous solution (Gaq(H+) = −270.29 kcal/mol). See:; Thapa B; Schlegel HB. Density Functional Theory Calculation of pKa’s of Thiols in Aqueous Solution Using Explicit Water Molecules and the Polarizable Continuum Model. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2016. 20. 5726–5735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).We attempted to calculate the activation barriers to protonation/deprotonation in the different solvents. However, the computational results were not conclusive (see SI for details). This illustrates the difficulty of capturing solvent effects on proton transfer rates computationally.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.