ABSTRACT

Rabies is a fatal zoonosis that causes encephalitis in mammals, and vaccination is the most effective method to control and eliminate rabies. Virus-like vesicles (VLVs), which are characterized as infectious, self-propagating membrane-enveloped particles composed of only Semliki Forest virus (SFV) replicase and vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein (VSV-G), have been proven safe and efficient as vaccine candidates. However, previous studies showed that VLVs containing rabies virus glycoprotein (RABV-G) grew at relatively low titers in cells, impeding their potential use as a rabies vaccine. In this study, we constructed novel VLVs by transfection of a mutant SFV RNA replicon encoding RABV-G. We found that these VLVs could self-propagate efficiently in cell culture and could evolve to high titers (approximately 108 focus-forming units [FFU]/ml) by extensive passaging 25 times in BHK-21 cells. Furthermore, we found that the evolved amino acid changes in SFV nonstructural protein 1 (nsP1) at positions 470 and 482 was critical for this high-titer phenotype. Remarkably, VLVs could induce robust type I interferon (IFN) expression in BV2 cells and were highly sensitive to IFN-α. We found that direct inoculation of VLVs into the mouse brain caused reduced body weight loss, mortality, and neuroinflammation compared with the RABV vaccine strain. Finally, it could induce increased generation of germinal center (GC) B cells, plasma cells (PCs), and virus-neutralizing antibodies (VNAs), as well as provide protection against virulent RABV challenge in immunized mice. This study demonstrated that VLVs containing RABV-G could proliferate in cells and were highly evolvable, revealing the feasibility of developing an economic, safe, and efficacious rabies vaccine.

IMPORTANCE VLVs have been shown to represent a more versatile and superior vaccine platform. In previous studies, VLVs containing the Semliki Forest virus replicase (SFV nsP1 to nsP4) and rabies virus glycoprotein (RABV-G) grew to relatively low titers in cells. In our study, we not only succeeded in generating VLVs that proliferate in cells and stably express RABV-G, but the VLVs that evolved grew to higher titers, reaching 108 FFU/ml. We also found that nucleic acid changes at positions 470 and 482 in nsP1 were vital for this high-titer phenotype. Moreover, the VLVs that evolved in our studies were highly attenuated in mice, induced potent immunity, and protected mice from lethal RABV infection. Collectively, our study showed that high titers of VLVs containing RABV-G were achieved, demonstrating that these VLVs could be an economical, safe, and efficacious rabies vaccine candidate.

KEYWORDS: virus-like vesicles, Semliki Forest virus, rabies vaccine, glycoprotein

INTRODUCTION

Rabies virus (RABV), which belongs to the genus Lyssavirus in the family Rhabdoviridae, is a neurotropic, enveloped, negative-strand RNA virus. The whole genome of RABV encodes five structural proteins, namely, nucleoprotein (N), phosphoprotein (P), matrix protein (M), glycoprotein (G), and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (L). Glycoprotein is the only antigen protein that induces the production of virus-neutralizing antibodies (VNAs) in individuals exposed to the virus and is responsible for cell attachment and membrane fusion (1–3). RABV infection causes the fatal encephalitis known as rabies in mammals. This disease causes more than 60,000 human deaths worldwide every year (4). Approximately 98% of human rabies occurs in developing countries with large numbers of both stray and domestic dogs (5).

Although rabies is considered a deadly disease, it is preventable through extensive vaccination of domestic dogs and cats along with public health education (6–8). Inactivated vaccines that are commercially approved for humans and pets require multiple doses to elicit ideal immunity protection. In addition, producing large amounts of inactivated vaccines presents a large economic burden in developing countries (9, 10). Live attenuated vaccines (LAVs) are mainly utilized for wild animal vaccination. While LAVs lead to long-term protection, there is a potential risk of those strains reverting to a virulent phenotype (11, 12). Therefore, novel effective, safe, and affordable rabies vaccines are still urgently needed to prevent RABV infection in both humans and pets.

Alphaviruses, including Semliki Forest virus (SFV), Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus (VEEV), and Sindbis virus (SINV), are positive-strand, membrane-enveloped RNA viruses. The genomic RNA of an alphavirus can act directly as mRNA and encodes the viral replicase (nonstructural proteins 1 to 4 [nsP1 to nsP4]). Subgenomic mRNA copied from the antigenomic RNA after replication encodes the alphavirus structural proteins (capsid and the E1 and E2 transmembrane glycoproteins). Alphavirus RNA replicons are derived from the DNA copy of the alphavirus genome from which the genes for the structural proteins are removed (13–15) and have been developed and used for transient expression of foreign proteins in mammalian cells and as experimental vaccine vectors (16–19). Virus-like vesicles (VLVs), which are characterized as infectious, self-propagating, membrane-enveloped particles, were accidentally discovered when the SFV RNA replicon encoding vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein (VSV-G) was transfected into mammalian cell lines (20). These VLVs were proven nonpathogenic in rhesus macaques and mice, had a low risk of genome integration or reversion to pathogenesis, and were immunogenic with no adjuvant added (21–23). Further study indicated that 10 amino acid changes in the SFV replicase of VLVs-VSV-G following 50 passages in BHK-21 cells in vitro, termed p50 mutations, led to the production of high-titer VLV replication in cell culture due to increased efficiency of release (24). This finding further improved the application of VLVs as vaccine candidates. Except for VSV-G, other viral structural proteins that can assemble infectious VLVs have rarely been reported. An early study showed that VLVs generated by transfection of the SFV replicon encoding RABV-G grew at low titers because of the limited spread of these VLVs to surrounding cells (20).

Our recent study showed that a recombinant alphavirus, Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus encoding RABV-G (VEEV-RABV-G), was able to assemble infectious VLVs. However, the relatively low viral titer in cells of VEEV-RABV-G (approximate 106 focus-forming units [FFU]/ml) limited its potential use as a rabies vaccine (25). In this study, we first attempted to generate VLVs by transfection of the SFV replicon encoding RABV-G (VLVs-RVG) and found that these VLVs proliferated poorly in cells. However, when we introduced the p50 mutations in this construct, the generated VLVs (termed rVLVs-RVG) exhibited at least 1,000-fold higher titers. Surprisingly, we found that the titers of rVLVs-RVG could attain approximate 108 FFU/ml by extensive passaging 25 times in BHK-21 cells. Subsequently, we revealed that the evolved VLVs, which we called p25 rVLVs-RVG, were highly attenuated in mice and could induce potent humoral immune response. Mice vaccinated with p25 rVLVs-RVG were protected from lethal RABV challenge even through the intracranial (i.c.) route. These results suggest that SFV-based VLVs containing RABV-G are high-titer evolvable, safe and efficacious, and can be the next generation of rabies vaccine.

RESULTS

Extensive passaging in cells increases virus titers of rVLVs-RVG.

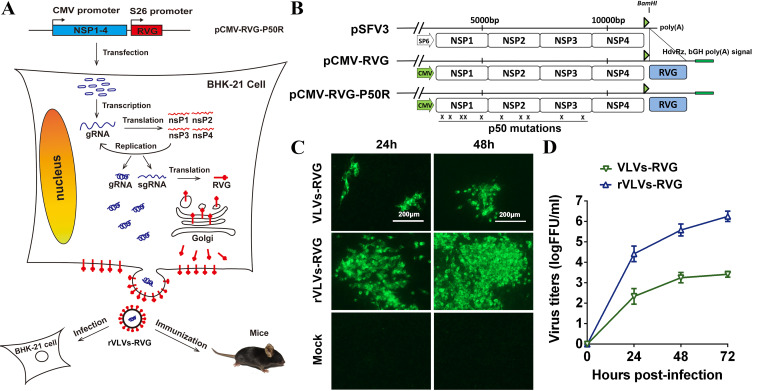

To examine whether the SFV replicon encoding RABV-G could generate infectious VLVs, as well as whether introducing p50 mutations into this construction could increase the titers of VLVs (24), pCMV-RVG or pCMV-RVG-P50R was transfected into BHK-21 cells, and at 72 h posttransfection, the supernatant was moved to new 6-well plates containing BHK-21 cells to generate the first generation of VLVs-RVG or rVLVs-RVG. The expression of RABV-G was confirmed by indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA). As shown in Fig. 1C, time-dependent accumulation of IFA-positive cells was observed in rVLV-RVG-infected cells from 24 to 48 h postinfection (hpi) compared with the relatively poor accumulation in VLV-RVG-infected cells. Further study found that the titers of rVLV-RVG reached nearly 106 FFU/ml, an approximately 1,000-fold increase compared to those of VLV-RVG (Fig. 1D). These results indicated that the expression of RABV-G from the SFV RNA replicon resulted in the release of infectious particles containing RABV-G. Furthermore, introduced p50 mutations could remarkably increase the VLV titers.

FIG 1.

Construction and rescue of rVLVs-RVG. (A) Experimental rationale. The diagram outlines the possible assembly progress of rVLVs-RVG. (B) Diagram of the construction of pCMV-RVG-P50R. The indicated SP6 promoter in pSFV3 was replaced by the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter (large green arrows). HdvRz and bGH poly(A) signals (small green rectangle) were added downstream of poly(A), and rabies virus glycoprotein (RABV-G) (large blue rectangle) was PCR amplified and cloned to the BamHI site to create pCMV-RVG. The plasmid pCMV-RVG-P50R used to derive rVLVs-RVG for passaging was constructed by introducing p50 mutations into pCMV-RVG. The Xs indicate the approximate positions of the p50 mutations. (C) Immunostaining of VLV-RVG- or rVLV-RVG-infected BHK-21 cells with RABV-G antibodies at the indicated times postinfection. (D) Growth kinetics of VLVs-RVG or rVLVs-RVG. The growth curves were conducted at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.01. Three independent experiments were performed in duplicate, and representative data are shown. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

To determine whether rVLVs-RVG could evolve in cultured cells to further improve the titers, we undertook extensive serial passaging studies. Surprisingly, by passaging rVLVs-RVG on BHK-21 cells 25 times, we found that the titers of rVLVs-RVG were increased at least 100-fold, reaching approximately 108 FFU/ml, and were stable during subsequent passaging to 50 generations. To determine a consensus sequence of these evolved VLV (p25 rVLVs-RVG) genomes, we performed reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) to generate overlapping DNA fragments covering the entire genome and sequenced these fragments. The assembled sequence revealed that 9 bp changed in the whole genome—2 of these changed amino acids in nsP1, 1 in nsP2, 1 in RABV-G, and the other 5 changes were silent (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Nucleotide and amino acid changes in p25 rVLVs-RVG

| Nucleotide change | Amino acid changea | Protein affected |

|---|---|---|

| A-5119-G | None | nsP1 |

| A-5160-G | K-470-R(SRIRMLL) | nsP1 |

| A-5197-G | I-482-M(RESMPVL) | nsP1 |

| G-5869-A | None | nsP2 |

| C-5959-A | None | nsP2 |

| A-6375-G | K-875-R(PCNRPII) | nsP2 |

| T-6895-A | None | nsP2 |

| C-7954-T | None | nsP3 |

| C-11271-A | S-61-R(SGFRYME) | RABV-G |

Amino acids are numbered in the SFV nsP1-3 or in RABV-G; no amino acid mutation was found in nsP4. Bold, underlined text indicates the amino acid that was changed.

Growth kinetics of VLVs in BHK-21 cells.

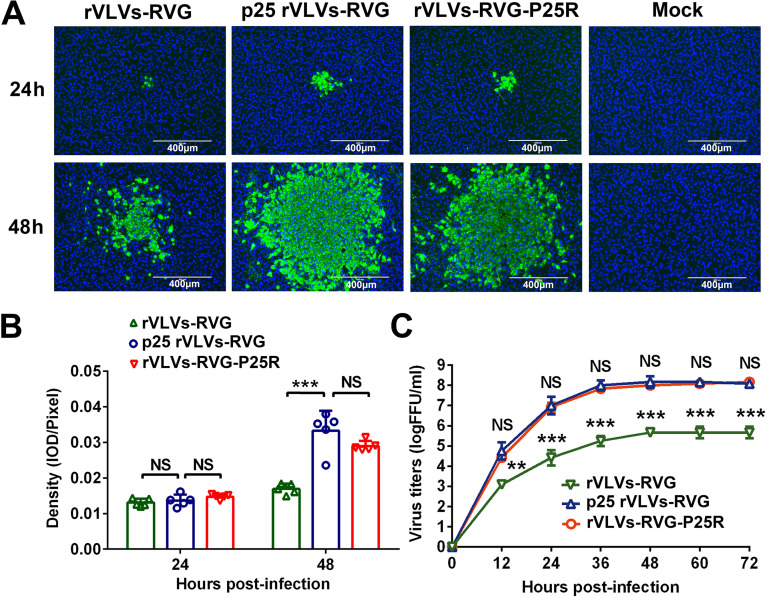

To prove that amino acid changes in p25 VLVs-RVG could increase viral titers, we introduced the mutations R-470-R, I-482-M, K-875-R, and S-61-R into the plasmid pCMV-RVG-P50R to create pCMV-RVG-P50R-P25R. After transfection of this plasmid into BHK-21 cells, VLVs with a high-titer phenotype were obtained and described as rVLVs-RVG-P25R. The spread of rVLVs-RVG, p25 rVLVs-RVG, and rVLVs-RVG-P25R in BHK-21 cells was examined by fluorescent plaque assay at 24 and 48 h postinfection (hpi), and typical fluorescent plaques are displayed in Fig. 2A. Simultaneously, the mean density of five fluorescent plaques in randomly selected images was analyzed using ImageJ software and is indicated as the integrated optical density (IOD)/pixel (Fig. 2B). As we expected, the fluorescent plaques of p25 rVLVs-RVG and rVLVs-RVG-P25R grew more rapidly than those of rVLVs-RVG from 24 to 48 hpi. At 48 hpi, the mean density of rVLVs-RVG was significantly lower than that of p25 rVLVs-RVG; however, no significant difference was found between rVLVs-RVG-P25R and p25 rVLVs-RVG.

FIG 2.

Extensive passaging increased the titers of rVLVs-RVG. (A) Representative images of fluorescent plaques in virus-like vesicle (VLV)-infected cells at a scale of 400 μm. BHK-21 cells were infected with rVLVs-RVG, p25 rVLVs-RVG, or rVLVs-RVG-P25R at an MOI of 0.001. The cultured cells were fixed at 24 or 48 h postinfection (hpi) and stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and goat anti-mouse IgG antibodies conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) after incubation with anti-RABV glycoprotein monoclonal antibody (MAb). (B) Mean densities of five fluorescent plaques in randomly selected images, as analyzed using ImageJ software, are indicated as the integrated optical density/pixel. (C) Comparison of growth kinetics of the indicated VLVs. The growth curves were conducted at an MOI of 0.01. Three independent experiments were performed in duplicate, and representative data are shown. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Asterisks indicate significant differences between the indicated experimental groups. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; NS, no significant difference (one-way analysis of variance [ANOVA]).

To describe the growth kinetics of these VLVs, multiple-step growth curves were examined. As shown in Fig. 2C, no significant difference in VLV growth was observed between rVLVs-RVG-P25R and p25 rVLVs-RVG at the indicated time points, and the maximal titer of p25 rVLVs-RVG was approximately 108 FFU/ml at 36 hpi. However, the titer of rVLVs-RVG was significantly lower than that of p25 rVLVs-RVG at the indicated time points.

Mutations K-470-R and I-482-M in SFV nsP1 are critical for efficient production of p25 rVLVs-RVG.

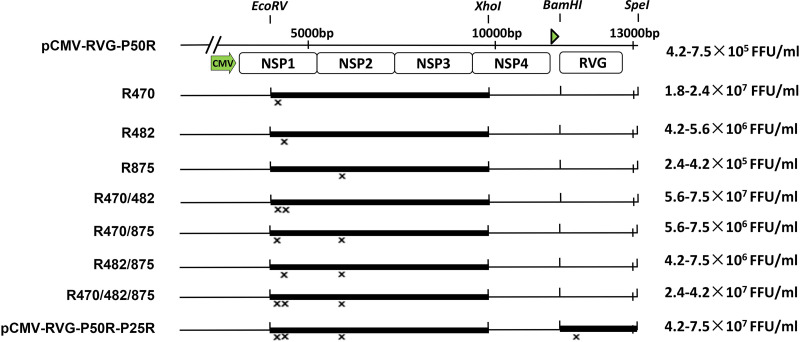

To analyze the critical genomic changes in p25 rVLVs-RVG, we began a stepwise reconstruction. Briefly, we introduced the evolved mutations stepwise into pCMV-RVG-P50R to create a series of reconstruction plasmids. At 48 h posttransfection, these reconstruction plasmids yielded various titers of recombinants in BHK-21 cells (Fig. 3). Interestingly, we found that recombinants containing the evolved mutation of K-470-R in SFV nsP1 generated relatively higher-titer VLVs than those without, and with the evolved mutations of K-470-R and I-482-M together in recombinant R470/482, the high-titer phenotype was basically recovered. These results suggested that the evolved mutations of K-470-R and I-482-M in SFV nsP1 were vital to generate the high-titer phenotype. However, mutations K-875-R in SFV nsP2 and S-61-R in RABV-G were not required.

FIG 3.

K-470-R and I-482-M in Semliki Forest virus (SFV) nsP1 were the key sites for the high-titer phenotype. The diagram illustrates the strategy of reconstruction of the p25 rVLVs-RVG genome sequence into the pCMV-RVG-P50R plasmid used to derive VLVs. The VLV titers obtained at 48 h after transfection of each construct into BHK-21 cells are given on the corresponding line. The range of titers in two experiments is shown.

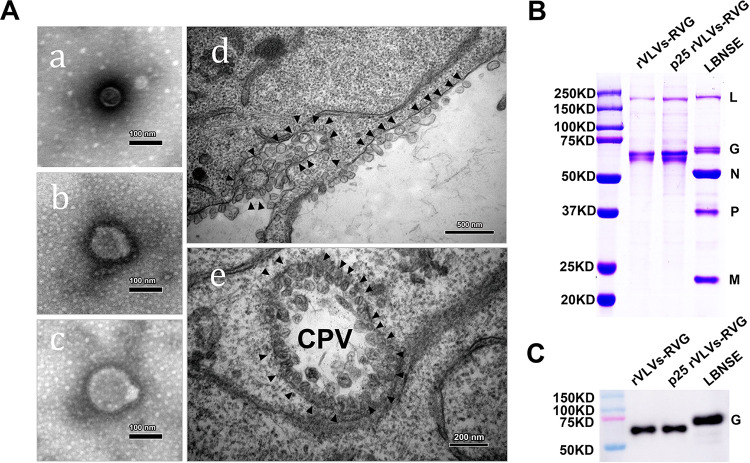

To characterize VLVs, we purified rVLVs-RVG and p25 rVLVs-RVG through ultracentrifugation, and the purified p25 rVLV-RVG virions and morphologies of p25 rVLVs-RVG in BHK-21 cells during viral infection were examined by thin-section transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Different sizes of purified VLVs were observed. The sizes ranged from 52 to 132 nm, with a mean size of 98 nm (Fig. 4A, panels a, b, and c). Furthermore, abundant spherical particles were observed on the surface of p25 rVLV-RVG-infected cells (Fig. 4A, panel d). To analyze the protein compositions of these VLVs by SDS-PAGE, purified RABV vaccine strain LBNSE virions served as a marker (Fig. 4B). As expected, RABV-G was the only viral structural protein found in the VLVs. To ensure the expression of RABV-G, we infected BHK-21 cells with rVLVs-RVG or p25 rVLVs-RVG. Cell lysates were prepared for Western blotting assays, and purified LBNSE virions served as a marker (Fig. 4C). Overall, our results demonstrated that rVLVs-RVG and p25 rVLVs-RVG could assemble infectious VLVs and stably express RABV-G. It is of note that the molecular weight of VLV-encoded RABV-G was slightly lower than that of LBNSE due to an unknown mechanism.

FIG 4.

Characterization of p25 rVLVs-RVG. (A) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of purified p25 rVLV-RVG virions or infected cells. Scale bars for all TEM images are shown. (a, b, and c) TEM images of virions purified with different sizes of fixed and stained VLVs. (d) Thin-section TEM of cells infected with p25 rVLVs-RVG. Spherule-like structures on the surface of cells were observed. (e) A representative cytopathic vacuole (CPV) observed in a cell infected with VLVs. (B) SDS-PAGE analysis of purified VLVs. Purified VLVs or RABV virions were fractionated by 12% SDS-PAGE, and the protein bands were visualized with Coomassie blue staining. The positions and molecular weights of the RABV structural proteins N, P, M, G, and L are indicated. (C) RABV-G expression in infected cells was analyzed by Western blotting.

VLVs induce type I IFN in BV2 cells and are sensitive to type I IFN.

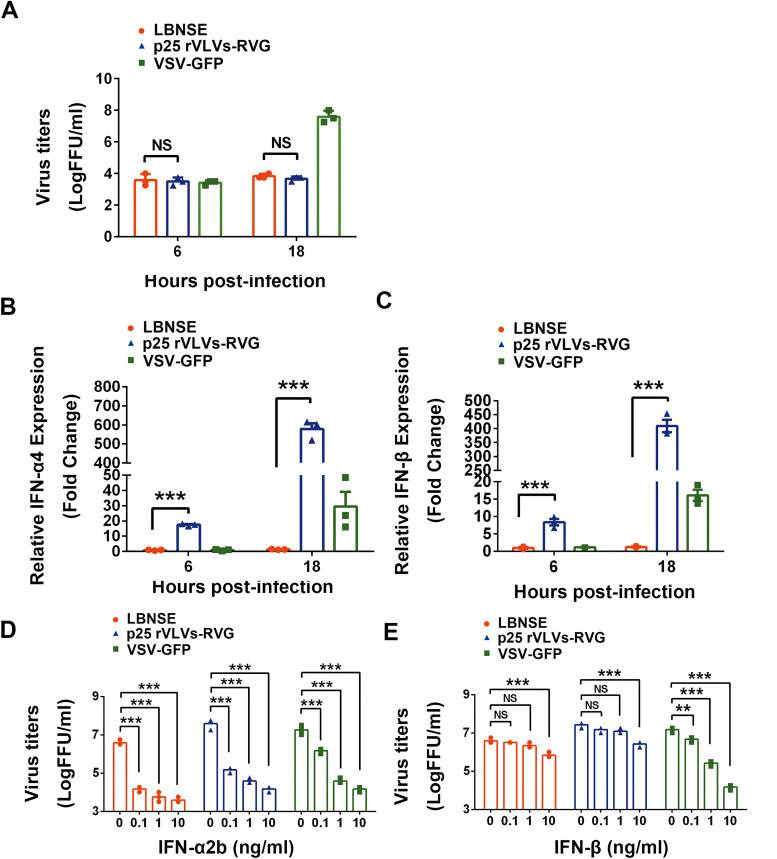

Type I interferons (IFNs), including IFN-α and IFN-β, have a variety of antiviral effects that inhibit viral replication (26, 27). To test the ability of VLVs to activate innate immunity, BV2 cells (mouse microglia immortalized cell line) were infected with LBNSE, p25 rVLVs-RVG, or VSV-green fluorescent protein (GFP) for 6 and 18 h at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.01, and the induction of type I IFN was measured by real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR); simultaneously, the supernatant of infected BV2 cells was harvested and the virus titers were measured. LBNSE and VSV-GFP were introduced in this study for comparison. Infection with VLVs over an 18-h period stimulated significantly higher levels of IFN-α/β mRNA expression than LBNSE when the quantity of infectious virus was similar (Fig. 5A to C). These results suggest that the capability of VLVs to induce type I IFN in BV2 cells was significantly higher than that of LBNSE.

FIG 5.

Interferon (IFN) induction by VLVs and their sensitivity to IFN. (A) Virus titers in supernatant of LBNSE-, p25 VLV-RVG-, or VSV-green fluorescent protein (GFP)-infected BV2 cells. (B and C) Relative expression of IFN-α4 (B) and IFN-β (C) was measured by reverse transcriptase quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) at the indicated time points in LBNSE-, p25 rVLVs-RVG-, and VSV-GFP-infected BV2 cells. (D and E) BHK-21 cells were incubated with IFNs at various doses for 18 h in triplicate, infected with LBNSE, p25 rVLVs-RVG, or VSV-GFP, and harvested at 24 hpi. Viral titers of cells incubated with IFN-α2b (D) or IFN-β (E) are shown. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Asterisks indicate significant differences between the indicated experimental groups. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; NS, no significant difference (one-way ANOVA).

To investigate the sensitivity of VLVs to type I IFN, BHK-21 cells were pretreated with IFN-α2b or IFN-β for 18 h and subsequently infected with LBNSE, p25 rVLVs-RVG, or VSV-GFP. The titers of VLVs, VSV-GFP, and LBNSE were reduced in a dose-dependent manner following IFN-α2b or IFN-β treatment relative to untreated cells (Fig. 5D and E). The titers of VLVs with at least a 100-fold decline achieved IFN-α2b concentrations as low as 0.1 ng/ml. Besides, the titers of VLVs and LBNSE were reduced by approximately 10-fold following IFN-β treatment at a concentration of 10 ng/ml. Collectively, these results show that the sensitivity to type I IFN of VLVs was comparable to that of LBNSE and that they are both sensitive to IFN-α2b pretreatment.

VLVs are highly attenuated in adult and suckling mice.

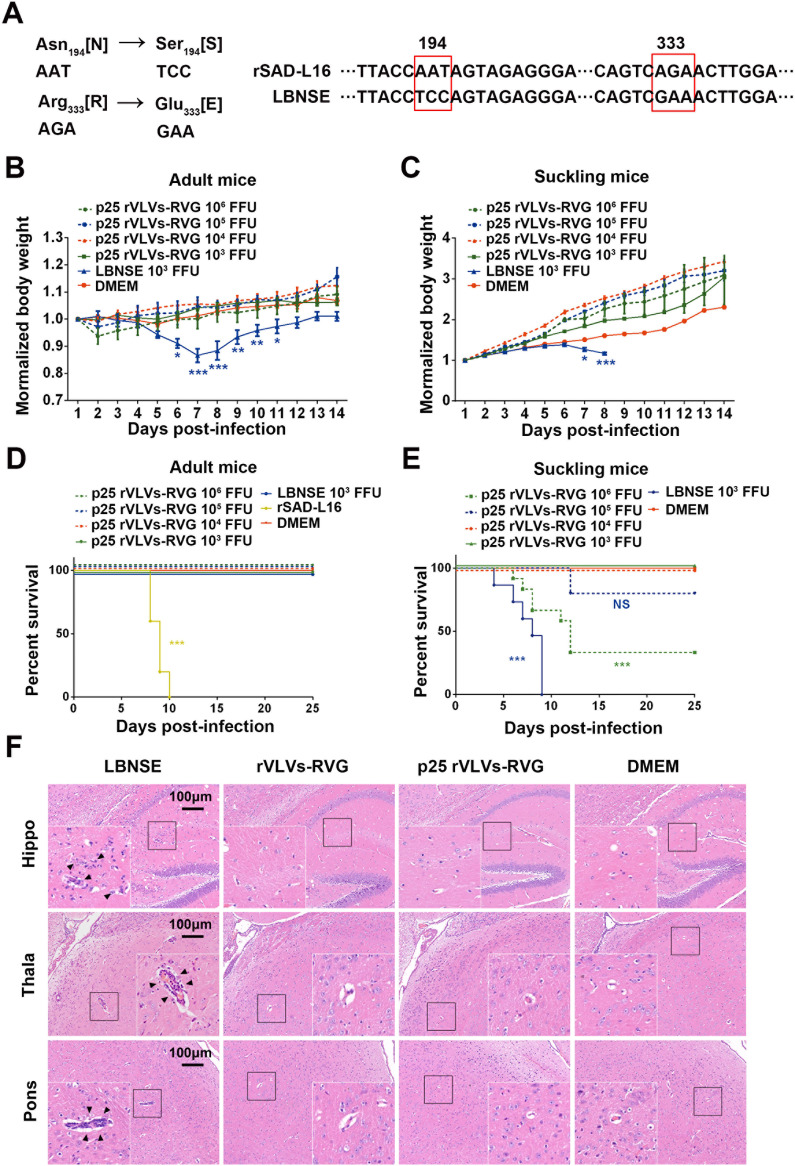

To examine the safety of VLV vaccine candidates, we compared the pathogenicity of p25 rVLVs-RVG with that of the RABV vaccine strains LBNSE or rSAD-L16 in a mouse model. As shown in Fig. 6A, rSAD-L16 is a recombinant strain derived from the RABV vaccine strain SAD-L16 currently used to immunize wildlife in Europe. LBNSE is derived from rSAD-L16 with mutations at amino acid positions 194 and 333 in the G protein, resulting in highly attenuated pathogenicity in the adult mouse brain (28). Groups of adult ICR mice (6 weeks old; n = 10/group) were inoculated i.c. with 103 to 106 FFU p25 rVLVs-RVG, 103 FFU LBNSE, or 103 FFU rSAD-L16 or were mock-infected with Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), and these mice were monitored daily for survival ratio and body weight loss. As shown in Fig. 6B and D, all adult mice infected with LBNSE suffered significant body weight loss by 5 to 7 days postimmunization (dpi), but they ultimately survived the i.c. infection. rSAD-L16 infection led to all adult mice dying within 10 dpi. Surprisingly, no differences in body weight or mortality were observed between p25 rVLVs-RVG-infected and mock-infected mice at the indicated time points.

FIG 6.

Virulence of p25 rVLVs-RVG in adult and suckling mice. (A) Correlation of the two RABV strains we used. LBNSE was derived from the SAD L16 cDNA clone with the Asn194→Ser194 and Arg333→Glu333 mutations, resulting in further attenuation of virulence in adult mouse brains. (B to E) Groups of 6-week-old adult ICR mice (n = 10/group) or 3-day-old suckling KM mice (n = 10 to 15/group) were infected intracranially (i.c.) with 103 to 106 focus-forming units (FFU) p25 rVLVs-RVG, 103 FFU LBNSE, or 103 FFU rSAD-L16 or were mock-infected with Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM). The body weight loss of adult mice (B) and suckling mice (C) was monitored daily for 14 days, and the mortality rates of adult mice (D) and suckling mice (E) were recorded daily for 25 days. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Different colors of asterisks indicate significant differences between the indicated corresponding experimental groups and the DMEM group. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 (one-way ANOVA). (F) Pathological changes in mouse brains infected with p25 VLVs-RVG. Groups of 6-week-old female ICR mice (n = 5/group) were i.c. infected with 103 FFU rVLVs-RVG, 103 FFU p25 rVLVs-RVG, or 103 FFU LBNSE or were mock-infected with 25 μl DMEM. At 6 days postinfection (dpi), sagittal sections of the mouse brain were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) to analyze pathological changes. Representative H&E staining images are presented. Bar, 100 μm. Black triangles indicate pathological changes, including gliosis and/or inflammatory cuffs of blood vessels (perivascular cuffing).

To further examine the safety of VLVs in young animals with incomplete immune systems, groups of suckling mice (2 to 3 days old; n = 10 to 15/group) were i.c. infected with 103 to 106 FFU p25 rVLVs-RVG or 103 FFU LBNSE or were mock-infected with DMEM, and these mice were monitored daily for survival ratio and body weight loss. As shown in Fig. 6C and E, all mice infected with LBNSE showed remarkable body weight loss and finally died within 9 dpi. In comparison, even when infected with the highest dose (106 FFU), there was still a survival rate of approximately 33% (4 of 12 mice survived) in p25 rVLV-RVG-infected mice. In addition, no suckling mice died in the p25 rVLV-RVG-infected group at doses of 103 or 104 FFU.

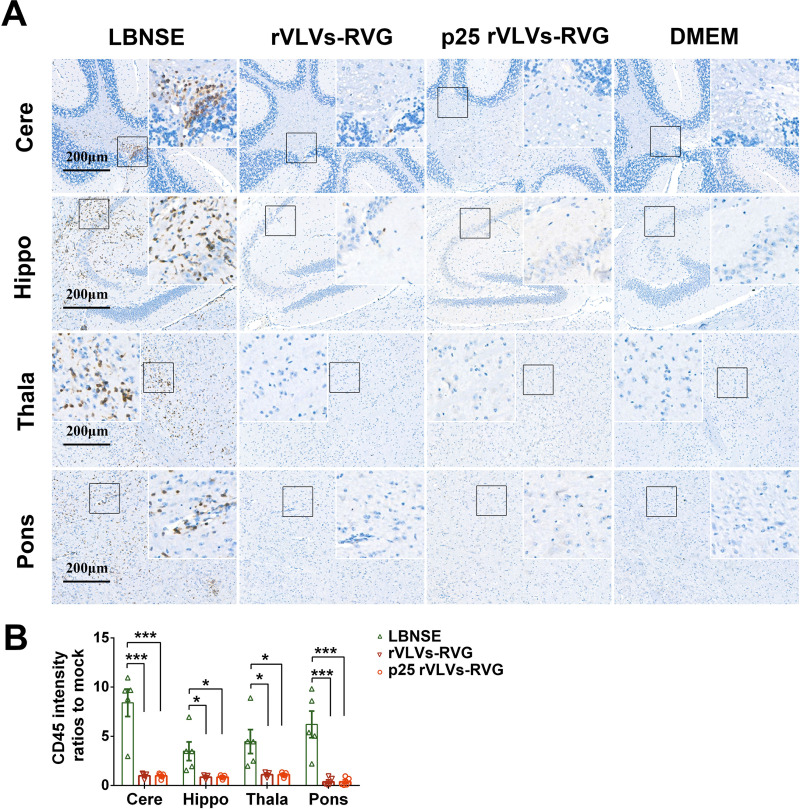

To compare the pathological changes in brains caused by i.c. infection, groups of adult ICR mice (6 weeks old; n = 5/group) were i.c. inoculated with rVLVs-RVG, p25 rVLVs-RVG, or LBNSE at a dose of 103 FFU or were mock-infected with DMEM. The mouse brains were then analyzed by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining at 6 dpi (Fig. 6F). Infiltration of inflammatory cells and perivascular cuffing could be observed in LBNSE-infected brains. In contrast, no obvious pathological changes were observed in the brain samples from rVLV-RVG- or p25 rVLV-RVG-infected mice. To further evaluate neuroinflammation caused by i.c. infection, the brain sections were stained with the panleukocyte marker CD45 (Fig. 7A). Semiquantitative results representing inflammation in brains were statistically analyzed by the IOD of the positive signal (Fig. 7B). As a result, less accumulation of CD45-positive inflammatory cells was observed in the brain samples from rVLV-RVG- or p25 rVLV-RVG-infected mice than in those from LBNSE-infected mice.

FIG 7.

Neurological inflammation induced by p25 rVLVs-RVG. Groups of 6-week-old female ICR mice (n = 5/group) were i.c. infected with 103 FFU rVLVs-RVG, 103 FFU p25 rVLVs-RVG, or 103 FFU LBNSE or were mock-infected with 25 μl DMEM. At 6 dpi, sagittal sections of the mouse brain were stained with CD45 to analyze inflammation. Histopathological analysis of different brain regions, including the pons (Pons), thalamus (Thala), hippocampus (Hippo), and cerebral cortex (Cere), was performed. (A) Representative histological images (bars, 200 μm) in different brain regions. (B) Positive 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) signals (brown) representing CD45 were analyzed by the integrated optical density (IOD) using NIH ImageJ software (IHC Toolbox). Statistical data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Asterisks indicate significant differences between the indicated experimental groups. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001; NS, not significant.

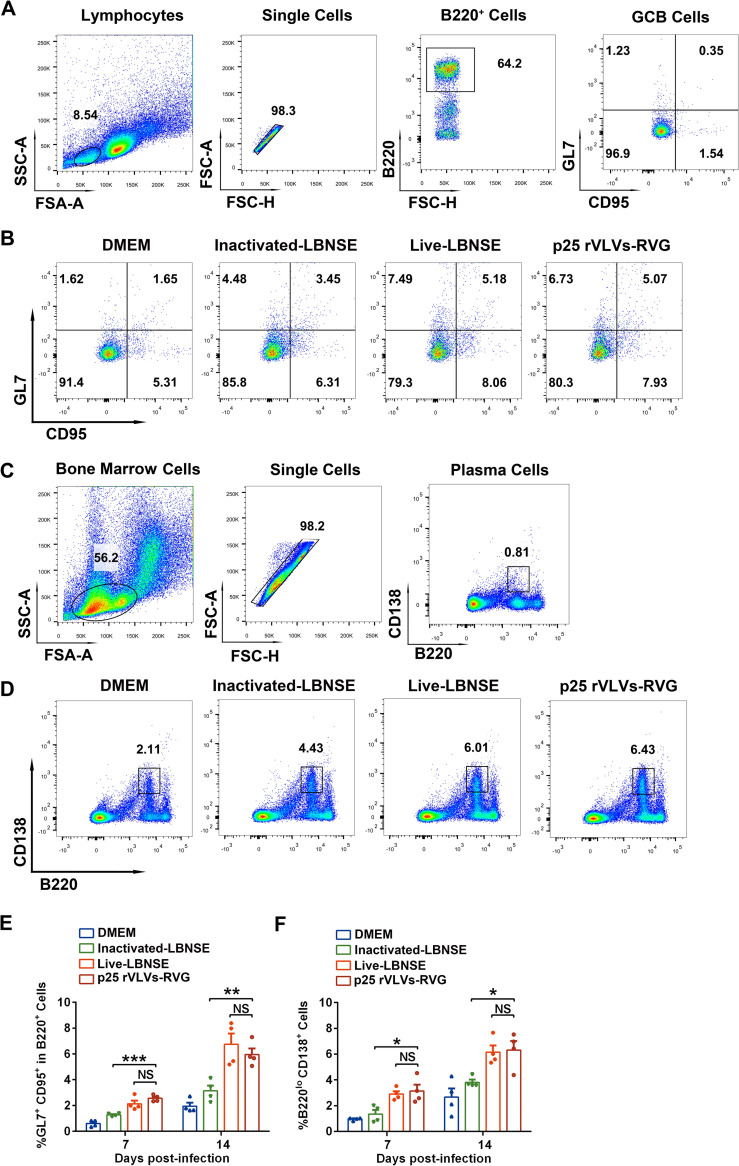

VLVs facilitate the generation of GC B cells and PCs in LNs.

Germinal centers (GCs) in LNs are critical for the production of high-affinity antibodies (29). GC B cells can differentiate into either memory B cells or plasma cells (PCs) that secrete large quantity of antibodies in response to antigens (30, 31). To evaluate the ability of p25 rVLVs-RVG to elicit the generation of GC B cells and plasma cells (PCs), groups of C57BL/6 mice (6 weeks old; n = 4/group) were immunized intramuscularly (i.m.) with p25 rVLVs-RVG, live LBNSE, inactivated LBNSE (inactivated by incubating LBNSE containing 108 FFU/ml virions with 0.025% [vol/vol] formaldehyde at 37°C for 24 h), or DMEM. GC B cells in the inguinal lymph nodes (LNs) or PCs in bone marrow (BM) were collected at 7 and 14 dpi and analyzed by flow cytometry. The gating strategies (Fig. 8A and C) and the representative flow cytometric plot (Fig. 8B and D) for GC B cells (GL7+ CD95+or B220+ B cells) or PCs (B220low CD138+) are displayed. As shown in Fig. 8E and F, mice immunized with p25 rVLVs-RVG generated significantly more GC B cells and PCs at both 7 and 14 dpi than those immunized with inactivated LBNSE. In addition, no significant differences in GC B-cell and PC generation were observed in the p25 rVLV-RVG- and live LBNSE-immunized groups. Together, these results suggested that p25 rVLVs-RVG could induce robust generation of GC B cells and PCs.

FIG 8.

Generation of germinal center (GC) B cells and plasma cells (PCs) postimmunization with p25 rVLVs-RVG. Groups of C57BL/6 mice (n = 4/group) were inoculated intramuscularly (i.m.) with 106 FFU p25 rVLVs-RVG, 106 FFU live LBNSE, inactivated LBNSE, or 100 μl DMEM. The inguinal lymph nodes (LNs) and bone marrow (BM) of mice were collected at 7 and 14 dpi. Single cells of the LNs or BM were prepared, stained, and analyzed for the proportion of B220+ GL7+ CD95+ GC B cells or B220low CD138+ plasma cells by flow cytometry. (A and C) Representative gating strategy for the detection of GC B cells (A) or PCs (C) in LNs or BM, respectively. (B and D) Representative flow cytometric plots of GC B cells (B) or PCs (D) from the four groups. (E and F) Statistical results of GC B cells (E) or PCs (F) among LNs or BM (n = 4/group). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Asterisks indicate significant differences between the indicated experimental groups. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 (one-way ANOVA).

VLVs elicit potent RABV-specific VNA and protect mice from lethal RABV challenge.

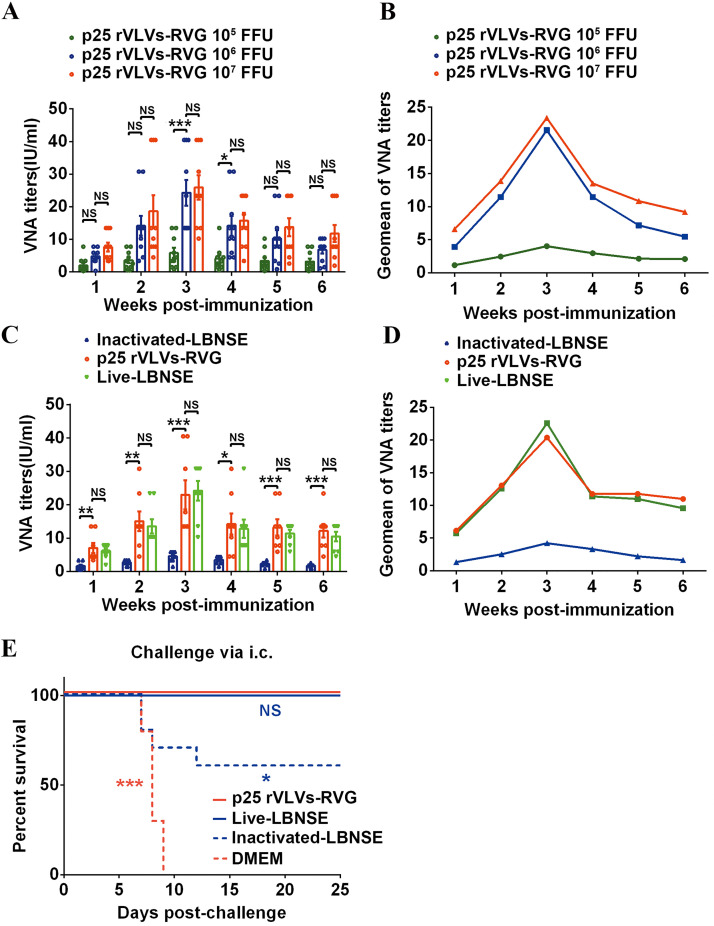

To evaluate the production of RABV-specific VNA elicited by VLVs, groups of ICR mice (6 weeks old; n = 10/group) were immunized with p25 rVLVs-RVG at doses ranging from 105 to 107 FFU, and VNA titers over a continuous 6 weeks postimmunization were determined by the fluorescent antibody virus neutralization (FAVN) method (32). As shown in Fig. 9A and B, dose-dependent increase in VNA titers was observed in immunized mice. The maximum geometric mean (GMT) of VNA titer induced by p25 rVLVs-RVG was observed in 107 FFU-immunized groups at 3 weeks postimmunization, reaching 23.38 IU/ml.

FIG 9.

VLVs induced robust RABV-specific VNA titers and protected mice from lethal RABV challenge. (A and B) Groups of 6-week-old female ICR mice (n = 10/group) were i.m. immunized with p25 rVLVs-RVG doses ranging from 105 to 107 FFU. Serum was collected from peripheral blood samples to quantify virus-neutralizing antibody (VNA) titers (A) and VNA maximum geometric mean (GMT) titers (B) by fluorescent antibody virus neutralization (FAVN) at the indicated time points postimmunization. (C and D) Groups of 6-week-old female ICR mice (n = 10/group) were i.m. immunized with 106 FFU p25 rVLVs-RVG, 106 FFU live LBNSE, or formaldehyde-inactivated LBNSE. Serum was collected from peripheral blood samples to quantify VNA titers (C) and VNA GMT titers (D) by FAVN at the indicated time points postimmunization. (E) Groups of 6-week-old female ICR mice (n = 10/group) were i.m. immunized with 106 FFU p25 rVLVs-RVG, 106 FFU live LBNSE, or formaldehyde-inactivated LBNSE. At 3 weeks postimmunization, all mice were i.c. challenged with 50× the 50% lethal dose (LD50) of the CVS-24 virulent strain. The survival rates in different immunization groups were recorded. Statistical data are presented as the mean ± SEM, and asterisks indicate significant differences between the indicated experimental groups. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; NS, not significant. Brown asterisks represent differences between DMEM and p25 rVLV-RVG groups, blue asterisks represent differences between formaldehyde-inactivated LBNSE and p25 rVLV-RVG groups, and “NS” represents no significant difference between live LBNSE and p25 rVLV-RVG groups. Survival curves were analyzed by the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test, and other data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA.

To compare the production of RABV-specific VNA elicited by VLVs with that of rabies vaccine strain LBNSE, groups of adult ICR mice (6 weeks old; n = 10/group) were immunized intramuscularly (i.m.) with 106 FFU p25 rVLVs-RVG, 106 FFU live LBNSE, inactivated LBNSE (inactivated by incubating LBNSE containing 108 FFU/ml virions with 0.025% [vol/vol] formaldehyde at 37°C for 24 h), or DMEM in a volume of 100 μl. VNA titers over a continuous 6 weeks postimmunization were determined by FAVN. As shown in Fig. 9C and D, the GMT of VNA induced by p25 rVLVs-RVG reached a maximum of 20.38 IU/ml at 3 weeks postimmunization, which was similar to that in live LBNSE-immunized mice (22.59 IU/ml). To compare the protective efficacy, groups of immunized mice (6 weeks old; n = 10/group) were challenged i.c. with 50× the 50% lethal dose (LD50) of the virulent CVS-24 strain at 3 weeks postimmunization. As shown in Fig. 9E, all mock-infected mice succumbed to rabies within 9 days, while 100% of p25 rVLV-RVG- or live LBNSE-immunized mice survived the lethal challenge and only 60% of mice survived in the inactivated LBNSE-immunized group. Together, the above-described results suggest that VLVs can elicit potent VNAs and protect mice from lethal RABV challenge.

DISCUSSION

Alphavirus replicons based on Semliki Forest virus (SFV), Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus (VEEV), and Sindbis virus (SINV) have been widely applied for vaccine development, including self-amplifying RNA (saRNA) vaccines (33–36), recombinant virus replicon particle (VRP) vaccines (37, 38), and layered DNA plasmid vaccines (39, 40). As a result of the self-replicative activity of alphavirus replicons, saRNAs or layered DNA plasmids can be delivered at low concentrations to express large amounts of antigens. Furthermore, the alphavirus replicons could be packaged into VRPs by cotransfection with helper RNA encoding the alphavirus structural proteins to facilitate assembly and budding of infectious particles (41, 42). However, VRPs are typically limited to one round of infection (13, 41, 43, 44). Unlike VRPs, VLVs can self-propagate in cells and are composed of a single exogenous protein, vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein (VSV-G) (13). The benefit to this characteristic is that there is no potential to reconstitute wild-type alphaviruses through recombination. In addition, VLVs replicate and spread without packaging in the capsid protein, which may promote more direct exposure of RNA to pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) and allow more efficient activation of innate immune mechanisms (24).

The mechanism that generates VLVs lacking a capsid protein remains unknown, and it is speculated that VLVs may resemble the primitive viruses that existed before the evolution of protective capsid and nonstructural proteins (24, 45). The light bulb-shaped replication complexes (spherules) that form at the plasma membrane during SFV replication are regarded as precursors involved in the formation of infectious VLVs, these spherules are then rapidly endocytosed and ultimately accumulate in the classic cytopathic vacuoles (CPVs) seen in cells containing SFV replicons (23, 24, 46). It has been proposed that the expression of VSV-G can inhibit endocytosis of spherules (47, 48), resulting in trapping of spherules on the cell surface. These spherules containing SFV RNA and VSV-G can occasionally be released from the cell surface to infect neighboring cells (20). As both RABV and VSV are members of the Rhabdoviridae family, we hypothesized that RABV-G may follow the same mechanism for VLV generation. However, RABV-G is transported slowly and inefficiently to the cell surface compared to VSV-G (49), which might explain the relatively lower titer of VLV-RVG generation.

A previous study indicated that VLVs-VSV-G could evolve to high titers by extensive passaging 50 times in BHK-21 cells (24). The late-domain motifs, which many enveloped viruses use to recruit vesicular budding machinery (endosomal sorting complexes required for transport [ESCRT]) to the budding sites for efficient budding (50–52), evolved near the C terminus of the SFV nsP1 protein in p50 VLVs-VSV-G and were necessary for the high-titer phenotype (24). As VLVs may lack the components required for membrane scission, it is speculated that the evolved late-domain motif in p50 VLVs-VSV-G could result in recruitment of additional components of the ESCRT pathway required for efficient budding (24). In our study, by introducing p50 mutations into VLVs-RVG, the titers increased approximately 1,000-fold, which might follow the same mechanism described above. Furthermore, we succeeded in generating high-titer VLVs-RVG by extensive passaging of these VLVs 25 times and found that four amino acids changed in the p25 rVLV-RVG genome. We demonstrated that the evolved mutations at amino acid positions 470 and 482 in SFV nsP1 were vital for the production of these high-titer VLVs. This evolved mutation might involve other unknown mechanisms that could facilitate the propagation of VLVs and needs future investigation.

In addition to the high titers we describe above, the significant advantage of VLVs as a rabies vaccine is high safety. Compared with the recombinant virus-vectored vaccines expressing RABV-G, including vaccinia virus, Newcastle virus, adenovirus, pox virus, and parainfluenza virus 5, which may cause adverse events, especially in immunocompromised individuals (53–58), VLVs exhibit excellent safety in the mouse model. Our data suggested that all adult mice did not display body weight loss and finally survived VLV infection, even via the i.c. route, at a dose of 106 FFU. For suckling mice with incomplete immune systems, VLV infection caused significantly lower fatality rates than RABV vaccine strain LBNSE. A previous study showed that VLVs-VSV-G were lethal when injected into the brains of mice lacking the type I interferon (IFN) receptor, indicating that activation of innate immunity was important in mediating VLV control and limiting pathogenic effects (59). Another study found that the replication of VLVs-VSV-G activated IFN production and the expression of IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs) in cell culture and was inhibited by IFN (45). Since our data suggested that VLVs-RVG could induce type I IFN mRNA expression in BV2 cells and were highly sensitive to IFN-α2b, we speculated that VLVs-RVG might be inhibited and finally eliminated from the central nervous system (CNS) by resident cells that have the capacity to induce and respond to type I IFN (60–63).

Notably, our recent study indicated that another alphavirus vector based on VEEV was quite efficient in assembling infectious VLVs when encoding RABV-G (25). This finding indicated that the combination of the alphavirus RNA replicon and the glycoproteins of Rhabdoviridae viruses might involve common machinery for the generation of infectious VLVs. Furthermore, p50 VLVs-VSV-G have been engineered to express single or multiple antigen(s) of human hepatitis B virus (HBV), and immunization with these recombinant VLVs induced HBV-specific CD8+ T cells and protected mice against experimental acute HBV infection (22, 64, 65). These findings highlight the versatility and utility of the VLV vaccine system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells, viruses, and animals.

BHK-21 cells, BSR cells (a BHK-21 clone), B7GG cells (a BHK-21 clone expressing T7 RNA polymerase, RABV-G, and histone 2B-tagged GFP) and BV2 cells (mouse microglia immortalized cell line) were cultured in DMEM or RPMI 1640 containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin at 37°C with 5% CO2. The RABV vaccine strain LBNSE was recovered using B7GG cells and was propagated and amplified in BSR cells as described previously (32). LBNSE was derived from the SAD L16 cDNA clone with two mutations in the G protein at amino acid positions 194 and 333 (28). The RABV virulent strain CVS-24 (challenge virus standard strain 24) was applied in the challenge test after vaccination (66). Recombinant VSV expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) was kindly provided by Mingzhou Chen (Wuhan University, China). Female ICR mice and C57/BL6 mice at the age of 6 to 8 weeks, as well as 2- to 3-day-old suckling Chinese Kun Ming (KM) mice, were obtained from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention of Hubei Province, People’s Republic of China. All mice were housed in individually ventilated cages in the Animal Facility at Huazhong Agricultural University (HZAU) located in Wuhan City, Hubei Province, People’s Republic of China.

Antibodies and reagents.

Anti-RABV glycoprotein monoclonal antibody (MAb) (clone no. 2B10) for indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA) and Western blot (WB) assay was prepared and stored in our laboratory. For immunohistochemistry (IHC), anti-mouse CD45 MAb (catalog no. GB11066) was purchased from Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd. Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)- or horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG was purchased from Proteintech Group, Inc. (Chicago, IL). These direct-labeled antibodies against special cell markers were used to analyze immune cells by flow cytometry (32, 67). FITC anti-mouse CD20 antibody (catalog no. 150408), Alexa Fluor 647 anti-mouse GL7 antibody (catalog no. 144605), and phycoerythrin (PE) anti-mouse CD95 antibody (catalog no. 152607) were applied to analyze the numbers of GC B cells. FITC anti-mouse/human CD45R/B220 antibody (catalog no. 103206), APC anti-mouse CD138 (Syndecan-1) antibody (catalog no. 142506), and PE anti-mouse CD38 antibody (catalog no. 102708) were used to analyze the numbers of PCs. All of these antibodies were purchased from BioLegend, Inc. (San Diego, CA), or BD Bioscience, Inc. (Franklin Lakes, NJ). Recombinant human IFN-α2b was purchased from MedChemExpress (USA), and recombinant mouse IFN-β was purchased from Sino Biological (Beijing, People’s Republic of China).

Construction, recovery and in vitro evolution of VLVs containing RABV-G.

To construct an in vivo transcription VLV rescue system, we replaced the SP6 promoter from plasmid pSFV3 (purchased from Addgene) with the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter and inserted the hepatitis delta virus ribozyme (HdvRz) sequence and bGH mRNA poly(A) stop signal downstream of the mRNA poly(A) stop signal to generate plasmid pCMV-SFV3. We then used PCR to generate overlapping DNA fragments spanning the EcoRV-BamHI restriction sites. These fragments containing p50 mutations (24) were then used to replace the corresponding fragments in the pCMV-SFV3 plasmid DNA to generate pCMV-SFV3-P50R. The open reading frame of the RABV vaccine strain (LBNSE) glycoprotein was PCR amplified and cloned into pCMV-SFV3 or pCMV-SFV3-P50R at a unique BamHI site to create pCMV-RVG or pCMV-RVG-P50R, respectively (Fig. 1B). pCMV-RVG or pCMV-RVG-P50R was transfected into BHK-21 cells with SuperFect transfection reagent (catalog no. 301305; Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions to generate VLVs-RVG or rVLVs-RVG, respectively. Supernatants were collected at 2 to 3 days posttransfection and centrifuged briefly to remove cell debris. Aliquots were stored at −80°C for the following experiment. In addition, p25 rVLVs-RVG were generated by extensively serial passaging rVLVs-RVG in BHK-21 cells 25 times.

Reconstruction of the p25 rVLVs-RVG genome into plasmid DNA.

The PrimeScript RT-PCR kit (catalog no. RR036Q; TaKaRa) and 16 DNA primer pairs were used with RNA from p25 rVLVs-RVG to generate overlapping double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) fragments covering the genome. Sequences of the fragments were determined (Tsingke) and assembled using DNAstar software. The assembled sequence revealed 9 base pair changes in the whole genome, namely, two changed amino acids in nsP1, one changed amino acid in nsP2, one changed amino acid in RABV-G, and five other silent changes (Table 1). To reconstruct the sequence of p25 rVLVs-RVG into plasmid DNA, the overlapping DNA fragments spanning the EcoRV-XhoI and BamHI-SpeI restriction sites were PCR amplified, and these 2 fragments containing p25 mutations were used to replace the corresponding fragments in pCMV-RVG-P50R to create pCMV-RVG-P50R-P25R (Fig. 4). rVLVs-RVG-P25R with a high-titer phenotype were generated by transfecting pCMV-RVG-P50R-P25R into BHK-21 cells. Furthermore, p25 mutations were introduced stepwise into pCMV-RVG-P50R. Briefly, the restriction fragments spanning the EcoRV-XhoI restriction sites were PCR amplified, and these fragments containing the indicated p25 mutations were used to replace the corresponding fragments in pCMV-RVG-P50R to create a series of recombinants labeled R470, R482, R875, R470/482, R470/875, R482/875, and R470/482/875 (Fig. 4). These recombinants were used to produce VLVs containing the indicated p25 mutations.

Virus titration and growth curves.

Quantification of VLV titers was performed by serial dilution of BHK-21 cells and indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA) to confirm RABV-G expression. Briefly, monolayer BHK-21 cells in 96-well plates were inoculated with serial 10-fold dilutions of VLVs-RVG, rVLVs-RVG, p25 rVLVs-RVG, or rVLVs-RVG-P25R in quadruplicate and cultured at 37°C for 48 h. Then, the cultured cells were fixed with 80% ice-cold acetone and stained with anti-RABV glycoprotein MAb (clone no. 2B10) for 1 h. The cells were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and further incubated with goat anti-mouse IgG antibodies conjugated with FITC (Proteintech Group, Inc.) at room temperature for 1 h. The green fluorescence antigen-positive focus was calculated under an IX51 fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), and virus titers are presented as FFU/ml. Growth curves of rVLVs-RVG, p25 rVLVs-RVG, or rVLVs-RVG-P25R in BHK-21 cells were generated in 12-well plates at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.01. Cell supernatants were collected at successive 12-h intervals postinfection. Viral titers were then quantitated by serial dilution of BHK-21 cells as described above.

Fluorescent plaque assay.

The spread of rVLVs-RVG, p25 rVLVs-RVG, or rVLVs-RVG-P25R was determined by fluorescent plaque assay on BHK-21 cells. Briefly, BHK-21 cells were seeded into 24-well plates and infected with rVLVs-RVG, p25 rVLVs-RVG, or rVLVs-RVG-P25R at an MOI of 0.001. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 1 h before a layer of 1% methylcellulose in DMEM containing 2% FBS was added. Then, the cultured cells were fixed at the indicated time points with 80% ice-cold acetone and stained with anti-RABV glycoprotein MAb (clone no. 2B10) diluted in PBS (1:200) for 1 h. The cells were washed three times with PBS and incubated with goat anti-mouse IgG antibodies (1:500 dilution in PBS) conjugated with FITC at room temperature for 1 h. Then, the cells were washed three times with PBS and further incubated with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; 1:500 dilution in PBS). Fluorescence images were taken at ×100 magnification with a fluorescence microscope (EVOS FL Auto; Invitrogen). Simultaneously, the mean density of 5 fluorescent plaques in randomly selected images was analyzed using ImageJ software and is indicated as the IOD/pixel.

Western blotting.

BHK-21 cells were infected with LBNSE, rVLVs-RVG, or p25 rVLVs-RVG at an MOI of 0.01. At 48 h postinfection (hpi), the cells were lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (Beyotime, China). Proteins were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and then electrotransferred onto a 0.2-μm polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany), followed by blocking with 5% skim milk in Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (TBST; 50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20 [pH 7.4]) for 1 h at room temperature. The blocked membranes were then incubated with anti-RABV glycoprotein MAb (clone no. 2B10) at room temperature for another 5 h. After washing 3 times with TBST, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary goat anti-mouse IgG antibodies at room temperature for 45 min, followed by washing three times with TBST. The protein bands were visualized with a chemiluminescent HRP-conjugated antibody detection reagent (Merck Millipore).

Purification of p25 rVLVs-RVG virions.

BHK-21 cells were infected with rVLVs-RVG or p25 rVLVs-RVG at an MOI of 0.01 and incubated for 72 h or 48 h at 37°C, respectively. The medium was reclaimed by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C to remove cells and cell debris. The clarified supernatants were concentrated by ultracentrifugation at 30,000 rpm for 3 h at 4°C in a Beckman SW32 rotor. The pellet was gently resuspended in 1 ml PBS, layered onto 10 ml of sucrose on a continuous gradient of 20 to 60%, and centrifuged at 38,000 rpm for 3 h in a Beckman SW41 rotor. VLV virions appeared at concentrations of 30 to 40% and were gently collected. The collected virions were ultracentrifuged at 30,000 rpm for 3 h to remove sucrose, and the purified virions were resuspended in 100 μl of PBS at 4°C overnight and stored at −80°C for the following experiment. LBNSE virions were grown and purified in parallel to provide markers for SDS-PAGE.

Thin-section transmission electron microscopy.

BHK-21 cell monolayers were infected with p25 rVLVs-RVG at an MOI of 0.01. At 48 hpi, infected BHK-21 cells were prefixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde at room temperature for 2 h before scraping and pelleting by centrifugation at 400 × g for 10 min. Following rinsing with 0.1 M PBS, the cells were postfixed with 1% OSO4 for at least 2 h at 4°C. All pellets were dehydrated stepwise in a graded series of ethanol and embedded in Epon-812. Ultrathin sections were cut on an EM UC7 ultramicrotome (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) and double stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. The grids containing ultrathin sections were examined with an H-7650 microscope (Hitachi, Japan) operated at 100 kV.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining and immunohistochemistry.

To study the histological changes in adult mice, groups of adult ICR mice (6 weeks old; n = 5/group) were i.c. infected with LBNSE, rVLVs-RVG, or p25 rVLVs-RVG at a dose of 104 FFU in a volume of 25 μl. At 9 dpi, all infected mice were anaesthetized and perfused with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. Then, the brains were removed and postfixed with the same fixative for 3 days. Fixed brains were embedded in paraffin and then sagittally sectioned at 4-μm thickness on a microtome and mounted on APS coated slides. For hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, sagittal sections were deparaffinized and stained with H&E (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). For CD45 staining, sections were incubated with anti-mouse CD45 MAb (1:3,000) in PBS containing 4% goat serum and 0.2% Triton X-100, followed by incubation with an HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody. The positive cells developed by the 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) reagent were brown-yellow, and nuclei stained with hematoxylin were blue.

Type I IFN expression and the sensitivity of VLVs to type I IFN.

Total RNA of BV2 cells was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) and treated with DNase. The RNA concentration was measured with a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer. Preparation of cDNA was performed with equal amounts of total RNA from each sample using FSQ201 ReverTra Ace (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan). Gene expression was measured using reverse transcriptase quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) normalized to β-actin expression and quantified by the comparative threshold cycle (ΔΔCT) method using a 7300 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). The primer sequences for RT-qPCR using SYBR green reagents were as follows: β-actin, 5′-CTA TGC TCT CCC TCA CGC CAT CC-3′ (sense) and 5′-GTA GCC ACG CTC GGT CAG GAT CT-3′ (antisense); IFN-α4, 5′-AGC CTG TGT GAT GCA GGA A-3′ (sense) and 5′-GGC ACA GAG GCT GTG TTT CT-3′ (antisense); and IFN-β, 5′-AGA TGT CCT CAA CTG CTC TC-3′ (sense) and 5′-AGA TTC ACT ACC AGT CCC AG-3′ (antisense).

To test the sensitivity of VLVs to type I IFN, BHK-21 cells were pretreated with IFN-α2b or IFN-β for 18 h and subsequently infected with LBNSE, p25 rVLVs-RVG, or VSV-GFP at an MOI of 0.1. After 1 h of incubation, the cells were washed three times with PBS, and fresh DMEM containing 2% FBS was added. At 24 hpi, the viral titers of each group were measured by IFA as described above.

Flow cytometry assay.

Immune cells in the inguinal lymph nodes (LNs) and bone marrow (BM) were analyzed by flow cytometry as described previously (25). Briefly, the LNs and BM of mice were collected, and the solid tissues were carefully ground in precooled PBS (pH 7.4). The cells were resuspended in PBS containing 0.2% bovine serum albumin (BSA; wt/vol), transferred into a tube through a 40-mm nylon filter, centrifuged, and washed with PBS containing 0.2% BSA. Red blood cells in BM were removed by lysis buffer (catalog no. 555899; BD Biosciences, Inc., Franklin Lakes, NJ). After washing twice, the single suspended cells in PBS containing 0.2% BSA were counted. In total, 106 cells were stained with fluorescence-labeled antibodies. After incubation for 30 min at 4°C, the cells were washed twice with PBS (containing 0.2% BSA). Finally, stained cells were analyzed using a FACSVerse instrument (BD Biosciences, Inc.).

Titer determination of RABV-specific VNA.

RABV-specific virus-neutralizing antibody (VNA) titers were measured using the fluorescent antibody virus neutralization (FAVN) test as described previously (68). Briefly, the serum of mice was isolated and inactivated for 30 min at 56°C, 100 μl of DMEM was added to 96-well plates, and 50 μl of inactivated serum was added to the first column and serially diluted 3-fold. After dilution, the serum was neutralized with 50 μl of CVS-11 (100 FFU per well) at 37°C for 1 h. After neutralization, 100 μl of BSR cells (2 × 104 cells per well) was added to the neutralized medium in 96-well plates. After incubation for 72 h at 37°C in 5% CO2, BSR cells were fixed with 80% ice-cold acetone at −20°C for 30 min and stained with FITC-conjugated RABV-N MAb at 37°C for 1 h. Fluorescence was observed under an IX51 fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The fluorescence values of the measured serum were compared with those of a reference serum obtained from the National Institute for Biological Standards and Control (Hertfordshire, UK), and the results were normalized and quantified in IU/ml.

Studies of safety, immunization, and protection.

To evaluate the pathogenicity of p25 rVLVs-RVG, adult ICR mice (6 weeks old; n = 10/group) and suckling KM mice (2 to 3 days old; n = 10 to 15/group) were i.c. infected with serial 10-fold dilutions of p25 rVLVs-RVG ranging from 103 to 106 FFU in a volume of 25 μl (for adult mice) or 10 μl (for suckling mice) under isoflurane anesthesia; 103 FFU RABV vaccine strain LBNSE or 103 FFU rSAD-L16 was used for infection in parallel as the control, and another group was mock-infected with DMEM. Mouse body weight loss or survival data were recorded daily for 14 or 25 days after infection. Mice that appeared moribund or that had lost more than 25% of their starting body weight were humanely euthanized with CO2. To evaluate the immunization of p25 rVLVs-RVG, groups of adult ICR mice (6 to 8 weeks old; n = 10/group) were immunized intramuscularly (i.m.) with serial 10-fold dilutions of p25 rVLVs-RVG ranging from 105 to 107 FFU, and sera from the immunized mice were collected at 1-week intervals over 6 weeks. To evaluate the immunization and protection of VLVs compared with those of the RABV vaccine strain LBNSE, groups of adult ICR mice (6 to 8 weeks old; n = 10/group) were immunized i.m. with 106 FFU LBNSE or 106 FFU p25 rVLVs-RVG, inactivated LBNSE (inactivated by incubating LBNSE containing 108 FFU/ml virions with 0.025% [vol/vol] formaldehyde at 37°C for 24 h), or DMEM in a volume of 100 μl. Sera from immunized mice were collected at 1-week intervals over 6 weeks. At 3 weeks postimmunization, the groups of mice (n = 10/group) received an i.c. challenge with 50×LD50 CVS-24 strain. Mice that appeared moribund or had lost more than 25% of their starting body weight were humanely euthanized with CO2, and the survival ratio from the challenge test was recorded daily for 25 days.

Statistical analysis.

We used Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA) to perform the statistical analysis. The results are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). For analyses of survival data, the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test was used. The significance of the differences between groups was evaluated by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). P values of 0.05 (*), 0.01 (**), and 0.001 (***) between different groups were regarded as significant, highly significant, and very highly significant, respectively.

Ethics statement.

All animal experiments performed in this study strictly followed the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China. All animal experiments were approved by the Scientific Ethics Committee of Huazhong Agricultural University (permit HZAUMO-2018-040).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was partially supported by the Guangdong Major Project of Basic and Applied Basic Research (grant 2020B0301030007 to Z.F.F.) and by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 31872451 to L.Z. and 31872452 and 31720103917 to Z.F.F.).

Contributor Information

Ling Zhao, Email: zling604@yahoo.com.

Mark T. Heise, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

REFERENCES

- 1.Thoulouze MI, Lafage M, Schachner M, Hartmann U, Cremer H, Lafon M. 1998. The neural cell adhesion molecule is a receptor for rabies virus. J Virol 72:7181–7190. 10.1128/JVI.72.9.7181-7190.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lentz TL, Burrage TG, Smith AL, Crick J, Tignor GH. 1982. Is the acetylcholine receptor a rabies virus receptor? Science 215:182–184. 10.1126/science.7053569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evans JS, Selden D, Wu G, Wright E, Horton DL, Fooks AR, Banyard AC. 2018. Antigenic site changes in the rabies virus glycoprotein dictates functionality and neutralizing capability against divergent lyssaviruses. J Gen Virol 99:169–180. 10.1099/jgv.0.000998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fooks AR, Banyard AC, Horton DL, Johnson N, McElhinney LM, Jackson AC. 2014. Current status of rabies and prospects for elimination. Lancet 384:1389–1399. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62707-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schneider MC, Belotto A, Ade MP, Hendrickx S, Leanes LF, Rodrigues MJ, Medina G, Correa E. 2007. Current status of human rabies transmitted by dogs in Latin America. Cad Saude Publica 23:2049–2063. 10.1590/s0102-311x2007000900013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soulebot JP, Brun A, Chappuis G, Guillemin F, Tixier G. 1982. Rabies virus pathogenicity and challenge. Influence of the method of preparation, the route of inoculation, and the species. Comparison of the characteristics of the modified, fixed and wild strains. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis 5:71–78. 10.1016/0147-9571(82)90017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balaram D, Taylor LH, Doyle KAS, Davidson E, Nel LH. 2016. World Rabies Day—a decade of raising awareness. Trop Dis Travel Med Vaccines 2:19. 10.1186/s40794-016-0035-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rupprecht CE, Hanlon CA, Hemachudha T. 2002. Rabies re-examined. Lancet Infect Dis 2:327–343. 10.1016/s1473-3099(02)00287-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ertl HC. 2009. Novel vaccines to human rabies. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 3:e515. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knobel DL, Cleaveland S, Coleman PG, Fevre EM, Meltzer MI, Miranda MEG, Shaw A, Zinsstag J, Meslin FX. 2005. Re-evaluating the burden of rabies in Africa and Asia. Bull World Health Organ 83:360–368. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whetstone CA, Bunn TO, Emmons RW, Wiktor TJ. 1984. Use of monoclonal-antibodies to confirm vaccine-induced rabies in 10 dogs, 2 cats, and one fox. J Am Vet Med Assoc 185:285–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Esh JB, Cunningham JG, Wiktor TJ. 1982. Vaccine-induced rabies in four cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 180:1336–1339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liljestrom P, Garoff H. 1991. A new generation of animal cell expression vectors based on the Semliki Forest virus replicon. Biotechnology (N Y) 9:1356–1361. 10.1038/nbt1291-1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiong C, Levis R, Shen P, Schlesinger S, Rice CM, Huang HV. 1989. Sindbis virus: an efficient, broad host range vector for gene expression in animal cells. Science 243:1188–1191. 10.1126/science.2922607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis NL, Willis LV, Smith JF, Johnston RE. 1989. In vitro synthesis of infectious Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus RNA from a cDNA clone: analysis of a viable deletion mutant. Virology 171:189–204. 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90526-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karlsson GB, Liljestrom P. 2004. Delivery and expression of heterologous genes in mammalian cells using self-replicating alphavirus vectors. Methods Mol Biol 246:543–557. 10.1385/1-59259-650-9:543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olkkonen VM, Dupree P, Simons K, Liljestrom P, Garoff H. 1994. Expression of exogenous proteins in mammalian cells with the Semliki Forest virus vector. Methods Cell Biol 43:43–53. 10.1016/S0091-679X(08)60597-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pushko P, Parker M, Ludwig GV, Davis NL, Johnston RE, Smith JF. 1997. Replicon-helper systems from attenuated Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus: expression of heterologous genes in vitro and immunization against heterologous pathogens in vivo. Virology 239:389–401. 10.1006/viro.1997.8878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rice CM. 1996. Alphavirus-based expression systems. Adv Exp Med Biol 397:31–40. 10.1007/978-1-4899-1382-1_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rolls MM, Webster P, Balba NH, Rose JK. 1994. Novel infectious particles generated by expression of the vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein from a self-replicating RNA. Cell 79:497–506. 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90258-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schell JB, Rose NF, Bahl K, Diller K, Buonocore L, Hunter M, Marx PA, Gambhira R, Tang H, Montefiori DC, Johnson WE, Rose JK. 2011. Significant protection against high-dose simian immunodeficiency virus challenge conferred by a new prime-boost vaccine regimen. J Virol 85:5764–5772. 10.1128/JVI.00342-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reynolds TD, Buonocore L, Rose NF, Rose JK, Robek MD. 2015. Virus-like vesicle-based therapeutic vaccine vectors for chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Virol 89:10407–10415. 10.1128/JVI.01184-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rose NF, Publicover J, Chattopadhyay A, Rose JK. 2008. Hybrid alphavirus-rhabdovirus propagating replicon particles are versatile and potent vaccine vectors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:5839–5843. 10.1073/pnas.0800280105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rose NF, Buonocore L, Schell JB, Chattopadhyay A, Bahl K, Liu X, Rose JK. 2014. In vitro evolution of high-titer, virus-like vesicles containing a single structural protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111:16866–16871. 10.1073/pnas.1414991111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang YN, Chen C, Deng CL, Zhang CG, Li N, Wang Z, Zhao L, Zhang B. 2020. A novel rabies vaccine based on infectious propagating particles derived from hybrid VEEV-rabies replicon. EBioMedicine 56:102819. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahmed M, McKenzie MO, Puckett S, Hojnacki M, Poliquin L, Lyles DS. 2003. Ability of the matrix protein of vesicular stomatitis virus to suppress beta interferon gene expression is genetically correlated with the inhibition of host RNA and protein synthesis. J Virol 77:4646–4657. 10.1128/jvi.77.8.4646-4657.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malmgaard L. 2004. Induction and regulation of IFNs during viral infections. J Interferon Cytokine Res 24:439–454. 10.1089/1079990041689665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wen Y, Wang H, Wu H, Yang F, Tripp RA, Hogan RJ, Fu ZF. 2011. Rabies virus expressing dendritic cell-activating molecules enhances the innate and adaptive immune response to vaccination. J Virol 85:1634–1644. 10.1128/JVI.01552-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haberman AM, Gonzalez DG, Wong P, Zhang TT, Kerfoot SM. 2019. Germinal center B cell initiation, GC maturation, and the coevolution of its stromal cell niches. Immunol Rev 288:10–27. 10.1111/imr.12731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith KM, Pottage L, Thomas ER, Leishman AJ, Doig TN, Xu D, Liew FY, Garside P. 2000. Th1 and Th2 CD4+ T cells provide help for B cell clonal expansion and antibody synthesis in a similar manner in vivo. J Immunol 165:3136–3144. 10.4049/jimmunol.165.6.3136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hwang IY, Park C, Harrison K, Kehrl JH. 2009. TLR4 signaling augments B lymphocyte migration and overcomes the restriction that limits access to germinal center dark zones. J Exp Med 206:2641–2657. 10.1084/jem.20091982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao L, Toriumi H, Wang H, Kuang Y, Guo X, Morimoto K, Fu ZF. 2010. Expression of MIP-1α (CCL3) by a recombinant rabies virus enhances its immunogenicity by inducing innate immunity and recruiting dendritic cells and B cells. J Virol 84:9642–9648. 10.1128/JVI.00326-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saxena S, Sonwane AA, Dahiya SS, Patel CL, Saini M, Rai A, Gupta PK. 2009. Induction of immune responses and protection in mice against rabies using a self-replicating RNA vaccine encoding rabies virus glycoprotein. Vet Microbiol 136:36–44. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vogel AB, Lambert L, Kinnear E, Busse D, Erbar S, Reuter KC, Wicke L, Perkovic M, Beissert T, Haas H, Reece ST, Sahin U, Tregoning JS. 2018. Self-amplifying RNA vaccines give equivalent protection against influenza to mRNA vaccines but at much lower doses. Mol Ther 26:446–455. 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ajbani SP, Velhal SM, Kadam RB, Patel VV, Bandivdekar AH. 2015. Immunogenicity of Semliki Forest virus based self-amplifying RNA expressing Indian HIV-1C genes in mice. Int J Biol Macromol 81:794–802. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moyo N, Vogel AB, Buus S, Erbar S, Wee EG, Sahin U, Hanke T. 2019. Efficient induction of T cells against conserved HIV-1 regions by mosaic vaccines delivered as self-amplifying mRNA. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 12:32–46. 10.1016/j.omtm.2018.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perri S, Greer CE, Thudium K, Doe B, Legg H, Liu H, Romero RE, Tang Z, Bin Q, DubenskyTW, Jr, Vajdy M, Otten GR, Polo JM. 2003. An alphavirus replicon particle chimera derived from Venezuelan equine encephalitis and Sindbis viruses is a potent gene-based vaccine delivery vector. J Virol 77:10394–10403. 10.1128/jvi.77.19.10394-10403.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Suarez-Patino SF, Bernardino TC, Nunez EGF, Astray RM, Pereira CA, Soares HR, Coroadinha AS, Jorge SAC. 2019. Semliki Forest virus replicon particles production in serum-free medium BHK-21 cell cultures and their use to express different proteins. Cytotechnology 71:949–962. 10.1007/s10616-019-00337-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gupta PK, Dahiya SS, Kumar P, Rai A, Patel CL, Sonwane AA, Saini M. 2009. Sindbis virus replicon-based DNA vaccine encoding rabies virus glycoprotein elicits specific humoral and cellular immune response in dogs. Acta Virol 53:83–88. 10.4149/av_2009_02_83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saxena S, Dahiya SS, Sonwane AA, Patel CL, Saini M, Rai A, Gupta PK. 2008. A sindbis virus replicon-based DNA vaccine encoding the rabies virus glycoprotein elicits immune responses and complete protection in mice from lethal challenge. Vaccine 26:6592–6601. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.09.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lundstrom K. 2014. Alphavirus-based vaccines. Viruses 6:2392–2415. 10.3390/v6062392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lundstrom K. 2016. Alphavirus-based vaccines. Methods Mol Biol 1404:313–328. 10.1007/978-1-4939-3389-1_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Polo JM, Gardner JP, Ji Y, Belli BA, Driver DA, Sherrill S, Perri S, Liu MA, DubenskyTW, Jr.. 2000. Alphavirus DNA and particle replicons for vaccines and gene therapy. Dev Biol (Basel) 104:181–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lundstrom K. 2019. Plasmid DNA-based alphavirus vaccines. Vaccines (Basel) 7:29. 10.3390/vaccines7010029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marchese AM, Chiale C, Moshkani S, Robek MD. 2020. Mechanisms of innate immune activation by a hybrid alphavirus-rhabdovirus vaccine platform. J Interferon Cytokine Res 40:92–105. 10.1089/jir.2019.0123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spuul P, Balistreri G, Kaariainen L, Ahola T. 2010. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-, actin-, and microtubule-dependent transport of Semliki Forest virus replication complexes from the plasma membrane to modified lysosomes. J Virol 84:7543–7557. 10.1128/JVI.00477-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Whitaker-Dowling P, Youngner JS, Widnell CC, Wilcox DK. 1983. Superinfection exclusion by vesicular stomatitis virus. Virology 131:137–143. 10.1016/0042-6822(83)90540-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilcox DK, Whitaker-Dowling PA, Youngner JS, Widnell CC. 1983. Rapid inhibition of pinocytosis in baby hamster kidney (BHK-21) cells following infection with vesicular stomatitis virus. J Cell Biol 97:1444–1451. 10.1083/jcb.97.5.1444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Whitt MA, Buonocore L, Prehaud C, Rose JK. 1991. Membrane fusion activity, oligomerization, and assembly of the rabies virus glycoprotein. Virology 185:681–688. 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90539-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rossman JS, Lamb RA. 2013. Viral membrane scission. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 29:551–569. 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101011-155838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Votteler J, Sundquist WI. 2013. Virus budding and the ESCRT pathway. Cell Host Microbe 14:232–241. 10.1016/j.chom.2013.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weiss ER, Gottlinger H. 2011. The role of cellular factors in promoting HIV budding. J Mol Biol 410:525–533. 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.04.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kieny MP, Lathe R, Drillien R, Spehner D, Skory S, Schmitt D, Wiktor T, Koprowski H, Lecocq JP. 1984. Expression of rabies virus glycoprotein from a recombinant vaccinia virus. Nature 312:163–166. 10.1038/312163a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ge JY, Wang XJ, Tao LH, Wen ZY, Feng N, Yang ST, Xia XZ, Yang CL, Chen HL, Bu ZG. 2011. Newcastle disease virus-vectored rabies vaccine is safe, highly immunogenic, and provides long-lasting protection in dogs and cats. J Virol 85:8241–8252. 10.1128/JVI.00519-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Amann R, Rohde J, Wulle U, Conlee D, Raue R, Martinon O, Rziha HJ. 2013. A new rabies vaccine based on a recombinant ORF virus (parapoxvirus) expressing the rabies virus glycoprotein. J Virol 87:1618–1630. 10.1128/JVI.02470-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen Z, Zhou M, Gao X, Zhang G, Ren G, Gnanadurai CW, Fu ZF, He B. 2013. A novel rabies vaccine based on a recombinant parainfluenza virus 5 expressing rabies virus glycoprotein. J Virol 87:2986–2993. 10.1128/JVI.02886-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Blancou J, Kieny MP, Lathe R, Lecocq JP, Pastoret PP, Soulebot JP, Desmettre P. 1986. Oral vaccination of the fox against rabies using a live recombinant vaccinia virus. Nature 322:373–375. 10.1038/322373a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tims T, Briggs DJ, Davis RD, Moore SM, Xiang Z, Ertl HC, Fu ZF. 2000. Adult dogs receiving a rabies booster dose with a recombinant adenovirus expressing rabies virus glycoprotein develop high titers of neutralizing antibodies. Vaccine 18:2804–2807. 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.van den Pol AN, Mao G, Chattopadhyay A, Rose JK, Davis JN. 2017. Chikungunya, influenza, Nipah, and Semliki Forest chimeric viruses with vesicular stomatitis virus: actions in the brain. J Virol 91:e02154-16. 10.1128/JVI.02154-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cavanaugh SE, Holmgren AM, Rall GF. 2015. Homeostatic interferon expression in neurons is sufficient for early control of viral infection. J Neuroimmunol 279:11–19. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2014.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chhatbar C, Detje CN, Grabski E, Borst K, Spanier J, Ghita L, Elliott DA, Jordao MJC, Mueller N, Sutton J, Prajeeth CK, Gudi V, Klein MA, Prinz M, Bradke F, Stangel M, Kalinke U. 2018. Type I interferon receptor signaling of neurons and astrocytes regulates microglia activation during viral encephalitis. Cell Rep 25:118–129.e4. 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Paul S, Ricour C, Sommereyns C, Sorgeloos F, Michiels T. 2007. Type I interferon response in the central nervous system. Biochimie 89:770–778. 10.1016/j.biochi.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zegenhagen L, Kurhade C, Koniszewski N, Overby AK, Kroger A. 2016. Brain heterogeneity leads to differential innate immune responses and modulates pathogenesis of viral infections. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 30:95–101. 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2016.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yarovinsky TO, Mason SW, Menon M, Krady MM, Haslip M, Madina BR, Ma X, Moshkani S, Chiale C, Pal AC, Almassian B, Rose JK, Robek MD, Nakaar V. 2019. Virus-like vesicles expressing multiple antigens for immunotherapy of chronic hepatitis B. iScience 21:391–402. 10.1016/j.isci.2019.10.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chiale C, Moshkani S, Rose JK, Robek MD. 2019. Heterologous prime-boost immunization with vesiculovirus-based vectors expressing HBV core antigen induces CD8+ T cell responses in naive and persistently infected mice and protects from challenge. Antiviral Res 168:156–167. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2019.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dietzschold B, Morimoto K, Hooper DC, Smith JS, Rupprecht CE, Koprowski H. 2000. Genotypic and phenotypic diversity of rabies virus variants involved in human rabies: implications for postexposure prophylaxis. J Hum Virol 3:50–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang Z, Li M, Zhou M, Zhang Y, Yang J, Cao Y, Wang K, Cui M, Chen H, Fu ZF, Zhao L. 2017. A novel rabies vaccine expressing CXCL13 enhances humoral immunity by recruiting both T follicular helper and germinal center B cells. J Virol 91:e01956-16. 10.1128/JVI.01956-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang Y, Wu Q, Zhou M, Luo Z, Lv L, Pei J, Wang C, Chai B, Sui B, Huang F, Fu ZF, Zhao L. 2020. Composition of the murine gut microbiome impacts humoral immunity induced by rabies vaccines. Clin Transl Med 10:e161. 10.1002/ctm2.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]