Abstract

Background

Sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors reduce hospitalizations for heart failure and cardiovascular death, although the underlying mechanisms have not been resolved. The SIMPLE trial (The Effects of Empagliflozin on Myocardial Flow Reserve in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus) investigated the effects of empagliflozin on myocardial flow reserve (MFR) reflecting microvascular perfusion, in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus at high cardiovascular disease risk.

Methods and Results

We randomized 90 patients to either empagliflozin 25 mg once daily or placebo for 13 weeks, as add‐on to standard therapy. The primary outcome was change in MFR at week 13, quantified by Rubidium‐82 positron emission tomography/computed tomography. The secondary key outcomes were changes in resting rate‐pressure product adjusted MFR, changes to myocardial flow during rest and stress, and reversible cardiac ischemia. Mean baseline MFR was 2.21 (95% CI, 2.08–2.35). There was no change from baseline in MFR at week 13 in either the empagliflozin: 0.01 (95% CI, −0.18 to 0.21) or placebo groups: 0.06 (95% CI, −0.15 to 0.27), with no treatment effect −0.05 (95% CI, −0.33 to 0.23). No effects on the secondary outcome parameters by Rubidium‐82 positron emission tomography/computed tomography was observed. Treatment with empagliflozin reduced hemoglobin A1c by 0.76% (95% CI, 1.0–0.5; P<0.001) and increased hematocrit by 1.69% (95% CI, 0.7–2.6; P<0.001).

Conclusions

Empagliflozin did not improve MFR among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and high cardiovascular disease risk. The present study does not support that short‐term improvement in MFR explains the reduction in cardiovascular events observed in the outcome trials.

Registration

URL: https://clinicaltrialsregister.eu/; Unique identifier: 2016‐003743‐10.

Keywords: empagliflozin, myocardial perfusion, positron emission tomography, SGLT2 inhibitor, type 2 diabetes mellitus

Subject Categories: Clinical Studies, Mechanisms, Heart Failure, Imaging, Nuclear Cardiology and PET

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- 82Rb

Rubidium‐82 positron emission tomography/computed tomography

- CANVAS

Canagliflozin Cardiovascular Assessment Study

- DECLARE‐TIMI 58

Dapagliflozin Effect on Cardiovascular Events—Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 58

- EMPA‐REG OUTCOME

Empagliflozin Cardiovascular Outcome Event Trial in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients—Removing Excess Glucose

- MFR

myocardial flow reserve

- SGLT2i

sodium‐glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

This is the first trial examining the effect of empagliflozin on myocardial flow reserve in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular risk factors.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

The treatment had no effect on myocardial flow reserve, suggesting that the cardioprotective effect of empagliflozin is unrelated to the cardiac microcirculation.

The landmark EMPA‐REG OUTCOME (Empagliflozin Cardiovascular Outcome Event Trial in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients—Removing Excess Glucose) trial1 demonstrated for the first time that a glucose‐lowering drug, the sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor (SGLT2i) empagliflozin, rapidly and significantly decreased the risk of hospitalization for heart failure and cardiovascular death in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Subsequent SGLT2i outcome trials, like DECLARE‐TIMI 58 (Dapagliflozin Effect on Cardiovascular Events—Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 58) and CANVAS (Canagliflozin Cardiovascular Assessment Study), demonstrated cardiovascular disease (CVD) benefits with SGLT2i in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus with established or high risk of CVD, but the mechanisms underlying these benefits remain to be elucidated.2, 3, 4 A consistent finding across the SGLT2i trials has been a reduction in admission rate for heart failure, and this result has been the focus of several studies.5 In patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, heart failure is the single most frequent and fatal cardiovascular complication, 2 to 4 times more common than myocardial infarction as a first event.6 Emerging evidence suggests that impaired cardiac microcirculation plays a key role in the inherent high risk of heart failure in type 2 diabetes mellitus, specifically heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.7 The chronic proinflammatory state of type 2 diabetes mellitus induces dysfunction of the coronary vascular endothelium, as demonstrated by increased expression of cytokines and adhesion molecules.8, 9 Cardiac microcirculation can be investigated noninvasively by positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) and a suitable radiotracer such as Rubidium‐82 (82Rb). Quantitative cardiac 82Rb‐PET/CT allows for measurement of myocardial blood flow at rest and during pharmacologically induced hyperemic conditions (“stress”). The ratio between rest and stress blood flow, known as myocardial flow reserve (MFR), integrates focal coronary arterial stenosis and diffuse atherosclerosis in the large epicardial arteries and the presence of microvascular dysfunction in the myocardium. MFR is a strong marker of the degree of microvascular dysfunction, and it is reduced in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus.10 Furthermore, MFR is a predictor of hospitalization for heart failure in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.11, 12 In animal studies, treatment with empagliflozin improves myocardial microcirculation by enhancing the vasodilatory response and reversing arterial thickening.13, 14 Additionally, canagliflozin has been shown to improve peripheral perfusion in a mouse model.15 However, MFR was not directly measured in these studies. Recently, treatment with empagliflozin significantly reduced resting myocardial blood flow in a crossover trial of 13 individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus.16 MFR increased nonsignificantly; however, the lack of significance may have been attributable to the relatively small sample size. Based on these findings, it seems plausible that treatment with SGLT2i could lead to improved MFR. We hypothesized that part of the beneficial effects of SGLT2i in the prevention of heart failure in type 2 diabetes mellitus could be mediated by improved MFR. The aim of this double‐blind, randomized placebo‐controlled trial, was to investigate whether treatment with empagliflozin improves MFR, as measured by cardiac 82Rb‐PET/CT in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and high risk of CVD.

Methods

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Trial Design and Participants

The SIMPLE trial (The Effects of Empagliflozin on Myocardial Flow Reserve in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus) was a single‐center, double‐blind, randomized clinical trial assessing the effect of empagliflozin on myocardial flow in high‐risk patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. The design and methods of the SIMPLE trial have been published previously.17 We enrolled 91 participants with known CVD or high CVD risk between April 4, 2017, and May 11, 2020. Participants were recruited from the outpatient diabetes mellitus clinics at University Hospital Herlev‐Gentofte, Glostrup and Rigshospitalet, Denmark. Patients were considered eligible if they had been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus at least 3 months before enrollment, had received stable glucose‐lowering treatment for 1 month, and their hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) was between 6.5% and 10% (48–86 mmol/mol) if they were receiving glucose‐lowering medication, and between 6.5% and 9% (48–75 mmol/mol) if they were drug naive. Participation also required established CVD, defined as a history of myocardial infarction, significant coronary stenosis, unstable angina, ischemic stroke or peripheral artery disease, or the presence of a CVD risk factor defined as albuminuria (urinary albumin–creatinine ratio ≥30 mg/g) or NT‐proBNP (N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide) ≥70 ng/L. Key exclusion criteria were estimated glomerular filtration rate ≤30 mL/min per 1.73 m2, severe bronchospastic disease (eg, asthma), and treatment with any SGLT2i within 1 month before study enrollment. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Capital Region of Denmark and the Danish Data Protection Agency. The trial was registered on EudraCT (2016‐003743‐10) and ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03151343) and carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (1993), as well as with the International Conference on Harmonization Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice. The trial was monitored by the Good Clinical Practice unit of Copenhagen, Denmark. The report of the results followed the Consolidated Statement of Reporting Trials guidelines.

Randomization and Masking

Eligible participants were randomly assigned (1:1) to either empagliflozin 25 mg once daily or a matching placebo for 13 weeks. Randomization was carried out by a central pharmacy (Glostrup Pharmacy, Denmark) using block randomization with a block size of 10. Participants and investigators were blinded to the treatment group for the duration of the study.

Myocardial Flow Reserve 82Rb‐PET/CT

Myocardial perfusion was measured using cardiac 82Rb‐PET/CT, which allows for flow quantification in absolute terms. All measurements were performed on a Siemens Biograph mCT/PET 128‐slice scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions). Measurements were taken at rest and during adenosine‐induced stress. Low‐dose noncontrast CT was acquired for attenuation correction. During the scan at rest, approximately 1100 MBq of 82Rb chloride from a CardioGen‐82 Sr‐82/Rb‐82 generator (Bracco Diagnostics, Inc.) was intravenously infused with a constant flow rate of 50 mL/min. List‐mode 3‐dimensional data acquisition was started with the tracer infusion and continued for 7 minutes. Static images were reconstructed with a 2.5‐minute delay to allow 82Rb to clear from the blood pool. Maximal hyperemia was induced with adenosine, infused at 140 µg/kg per minute for 6 minutes. After 2.5 minutes of adenosine infusion, intravenous 82Rb infusion and list‐mode acquisition was performed, using the same protocol as for rest. Myocardial blood perfusion quantification (milliliters per minute per gram) was performed using Cedars‐Sinai QGS+QPS 2015.6 software (Cedars‐Sinai Medical Center), which is based on a single‐compartment model for 82Rb tracer kinetics.18

Rest flow and, by extension, MFR varies according to cardiac work. Adjustment can be made for the cardiac workload by the rate‐pressure product19: rate‐pressure product–adjusted rest flow=(rest flow×10 000)/(heart rate at rest×systolic blood pressure at rest). To assess baseline risk among included patients, the following delineations of MFR were used: MFR values >2.5 were considered normal, values <2.0 were considered impaired MFR, and values between 2.0 and 2.5 were considered intermediate MFR.20 Additionally, the static images were used to quantify the extent and severity of perfusion abnormalities in the myocardium using Cedars‐Sinai QGS+QPS 2015.6 software (Cedars‐Sinai Medical Center). The difference between the total perfusion deficit at rest and under stress corresponds to the extent of inducible ischemia in the myocardium, a parameter used for deciding optimal management in patients with known or suspected coronary artery disease.21

Study Outcomes

The primary end point was between‐group change in MFR from baseline at week 13. Secondary exploratory endpoints included change in resting rate‐pressure product–adjusted MFR, rest flow, stress flow, and the extent of reversible ischemia.

Statistical Analysis

The sample size was based on a power calculation of the primary end point, MFR measured by 82Rb‐PET/CT. A change in MFR of 0.5 was considered clinically relevant, and a SD of 0.8 was based on recent studies in the PET/CT department.22 At a power of 80% and a 2‐sided significance level of 5%, 41 participants per group were needed. We aimed to include 92 participants to allow for a dropout rate of 10%. Analyses of the primary end point, change in MFR, and all secondary end points were based on the intention‐to‐treat population, that is, all patients with baseline measurements that took at least 1 dose of the trial medication. Variables were tested for normality using histograms and qq‐plots. Variables with skewed distributions were log‐transformed, using the natural logarithm, before statistical analysis. Transformed data are presented on the log scale. We used a constrained linear mixed model to calculate the change from baseline and between‐group difference at week 13 (ie, treatment effect). Baseline adjustment is an inherent feature of the constrained linear mixed model. To account for correlation between repeated measures on the same subject, an unstructured covariance was assumed. Aside from the secondary end points, rate‐pressure product–adjusted MFR, rest flow, stress flow, and reversible ischemia, additional exploratory end points were investigated post hoc.

Missing values were deemed missing at random and imputed implicitly by maximum likelihood estimation. When analyzing the per‐protocol population, that is, participants with both baseline and follow‐up measurements, a constrained linear mixed model was also used. Analysis of change in MFR categories by treatment group was performed using Fisher’s exact test. Exploratory analyses were performed to evaluate for potential effect modification across the following predefined subgroups: established versus not established coronary artery disease, history of myocardial infarction, presence of albuminuria at baseline, baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate <90 mL/min per 1.73 m2, baseline HbA1c >8.5% (69 mmol/mol), duration of diabetes mellitus >10 years, age >65 years, and baseline BMI >30 kg/m2, and sex. The division of subgroups follows recommendations to improve statistical inference.23 Descriptive characteristics are reported as mean and corresponding SD. Change from baseline is reported as mean, a 95% CI, and an unadjusted P value, unless stated otherwise. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses and graphical design were carried out using R version 4.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

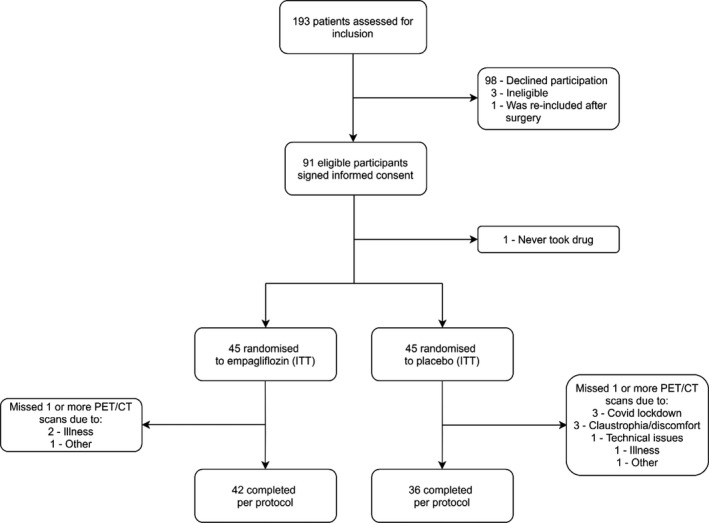

Results

Of 193 patients screened for eligibility, 91 fulfilled criteria and provided informed consent. Ninety patients received at least 1 dose of the study drug and were included in the intention‐to‐treat cohort; 45 patients received empagliflozin, and 45 received placebo. Baseline MFR values were obtained for 44 patients in the empagliflozin group and 43 in the placebo group. Of these, 29 had normal MFR, 22 had MFR in the intermediate range, and 36 had impaired MFR. In total, 78 participants, 36 in the placebo group and 42 in the active group, fulfilled per‐protocol criteria, since baseline and 13‐week 82Rb PET‐CT were available (Figure 1). Participants were predominantly men (80%), with mean (SD) HbA1c of 7.6% (±0.9) (59.5±10.3 mmol/mol), and blood pressure of 139 (±14) systolic and 81 (±10) mm Hg diastolic. A total of 51% had a history of coronary disease, defined as either previous myocardial infarction, significant stenosis of a coronary artery, or coronary artery bypass graft. Eight percent of the participants reported having episodes of chest pain. In addition, 16% had a prescription of long‐ or short‐acting nitrates. Mean (SD) left ventricular ejection fraction assessed by echocardiography was 58%±8%. By 82Rb‐PET/CT imaging, 10 participants had a reversible ischemia extent of ≥10% at baseline, which was equally distributed within the groups. Diabetes mellitus was well managed, with 32% of the participants receiving 1 glucose‐lowering drug, 30% receiving 2, and 33% receiving ≥3. Four percent did not receive any glucose‐lowering medication. The prevalence of cardiovascular prevention therapy among the participants was high, with 93% receiving a statin and 79% receiving either an angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor or an angiotensin II receptor blocker. The patients were balanced at baseline according to treatment groups (Table 1), except for the use of beta blockers (58% for the empagliflozin group versus 31% for the placebo group; P=0.020).

Figure 1. Consolidated Statement of Reporting Trials flow chart of the inclusion process.

CT indicates computed tomography; ITT, intention to treat; and PET, positron emission tomography.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Empagliflozin (n=45) | Placebo (n=45) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | |||

| Age, y | 66±9 | 67±9 | 0.675 |

| Male sex, % | 76 | 84 | 0.492 |

| Known duration of type 2 diabetes mellitus, y | 14 (7.5–19) | 15 (8–18) | 0.500 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 31.9±5.5 | 29.8±5.6 | 0.072 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 139±16 | 140±13 | 0.717 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 81±11 | 81±10 | 0.909 |

| Biochemistry | |||

| eGFR | 79.5±24.0 | 79.3±21.9 | 0.966 |

| HbA1c, mmol/mol | 60.6±10.9 | 58.4±9.6 | 0.338 |

| HbA1c, % | 7.7±1.0 | 7.5±0.9 | 0.338 |

| LDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 1.7±0.5 | 1.7±0.5 | 0,714 |

| HDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 1.0±0.2 | 1.0±0.3 | 0.561 |

| NT‐proBNP, ng/L | 119.5 (70.3, 213.8) | 103 (46.8, 237.5) | 0.813 |

| NT‐proBNP >70 ng/L | 31 (69) | 26 (58) | 0.382 |

| UACR, mg/g | 17 (9, 42) | 25 (11, 82) | 0.547 |

| UACR >30 mg/g | 14 (31) | 16 (36) | 0.823 |

| Hematocrit, % | 40±4 | 40±4 | 0.727 |

| Cardiovascular status n (%) | |||

| History of myocardial infarction | 21 (47) | 15 (33) | 0.282 |

| Coronary stenosis, previous PCI or CABG | 27 (60) | 20 (44) | 0.206 |

| History of stroke | 6 (13) | 6 (13) | 1.000 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 3 (7) | 3 (7) | 1.000 |

| Diabetes mellitus medication | |||

| Metformin | 35 (78) | 39 (87) | 0.408 |

| Insulin | 26 (58) | 26 (58) | 1.000 |

| GLP‐1 RA | 12 (27) | 11 (24) | 1.000 |

| DPP‐IV inhibitor | 6 (13) | 12 (27) | 0.188 |

| Sulfonylurea | 3 (7) | 3 (7) | 1.000 |

| Antihypertensive medication, n (%) | |||

| ACEi/ARB | 38 (84) | 33 (73) | 0.302 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 18 (40) | 20 (44) | 0.831 |

| Beta‐blockers, n (%) | 26 (58) | 14 (31) | 0.020 |

| Lipid lowering medication, n (%) | 41 (91) | 43 (96) | 0.673 |

| 82Rb‐PET/CT | |||

| MFR | 2.17±0.63 | 2.26±0.67 | 0.480 |

| RPP‐adjusted MFR | 1.93±0.64 | 2.01±0.54 | 0.511 |

| Myocardial stress flow, mL/g per min | 2.43±0.87 | 2.47±0.77 | 0.842 |

| Myocardial rest flow, mL/g per min | 1.16±0.36 | 1.17±0.42 | 0.835 |

| Baseline reversible extent (TPD, %) | 3.81±3.10 | 5.52±4.88 | 0.056 |

Values are presented as means±SD, medians (lower quartile–upper quartile) or percentages, as appropriate. 82Rb‐PET/CT indicates Rubidium‐82 positron emission tomography/computed tomography; ACEi, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; DPP‐IV, dipeptidyl peptidase‐4; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; GLP‐1 RA, glucose‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonist; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; LDL, low‐density lipoprotein; MFR, myocardial flow reserve; MI, myocardial infarction; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; RPP, rate‐pressure product; TPD, total perfusion deficit; and UACR, urinary albumin/creatinine ratio.

Myocardial Flow Reserve

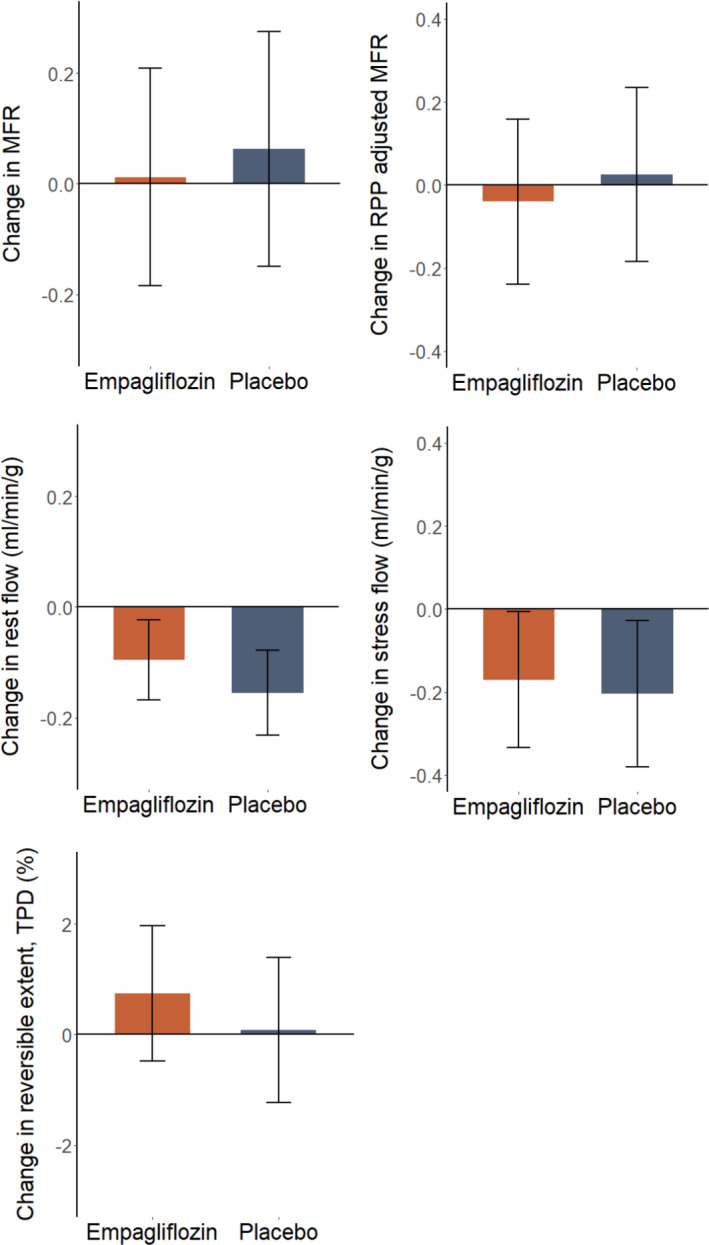

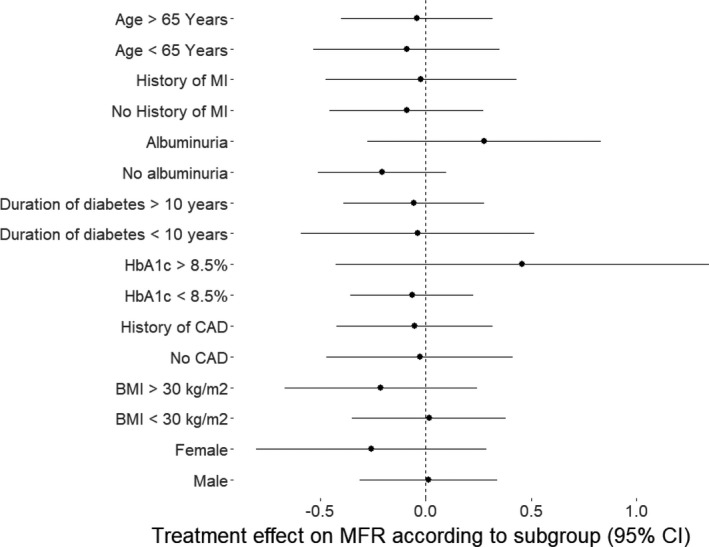

At baseline, mean (SD) MFR was 2.21 (95% CI, 2.08–2.35). The intention‐to‐treat analysis of the primary end point showed no change in MFR at 13 weeks in either group (empagliflozin: 0.01; 95% CI, −0.18 to 0.21; P=0.909 versus placebo: 0.06; 95% CI, −0.15 to 0.27; P=0.559). We did not find any treatment effect (−0.05; 95% CI, −0.33 to 0.23; P=0.716) (Table 2, Figure 2). Analyzing the per‐protocol population did not change the main findings of the primary end point (P=0.764 for treatment effect). Two participants in both treatment groups changed MFR category from intermediate to impaired, and 3 participants changed from normal to impaired (P=1.000). There was no effect modification of empagliflozin on MFR by any of the predefined subgroups or beta‐blocker use (Figure 3). Further, there was no treatment effect of empagliflozin on the primary end point MFR in patients with baseline intermediate or impaired MFR (P=0.835) or in the subgroup (n=43) of participants without established coronary artery disease (P=0.901).

Table 2.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

| Baseline (n=90) | Empagliflozin (n=42) | P Value | Placebo (n=36) | P Value | Group difference | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MFR | 2.21 (2.08 to 2.35) | 0.01 (−0.18 to 0.21) | 0.909 | 0.06 (−0.15 to 0.27) | 0.559 | −0.05 (−0.33 to 0.23) | 0.716 |

| MFR, RPP adjusted | 1.97 (1.84 to 2.09) | −0.04 (−0.23 to 0.16) | 0.694 | 0.03 (0.19 to 0.24) | 0.811 | −0.07 (−0.35 to 0.22) | 0.653 |

| Rest flow, mL/g per min | 1.16 (1.08 to 1.24) | −0.10 (−0.16 to −0.02) | 0.011 | −0.15 (−0.23 to −0.08) | >0.001 | 0.06 (−0.03 to 0.15) | 0.176 |

| Stress flow, mL/g per min | 2.45 (2.28 to 2.62) | −0.17 (−0.34 to −0.01) | 0.044 | −0.20 (−0.38 to −0.03) | 0.025 | −0.03 (−0.19 to 0.26) | 0.769 |

| Reversible extent, TPD, % | 4.66 (3.77 to 5.55) | 0.74 (−0.48 to 1.97) | 0.235 | 0.08 (−1.23 to 1.40) | 0.905 | 0.66 (−1.04 to 0.66) | 0.443 |

| HbA1c, % | 7.63 (7.43 to 7.83) | −0.68 (−0.86 to −0.49) | <0.001 | 0.08 (−0−11 to 0.27) | 0.411 | −0.76 (−1.00 to −0.51) | <0.001 |

| HbA1c, mmol/mol | 59.85 (57.66 to 62.04) | −7.40 (−9.39 to −5.42) | 0.86 (−1.21 to 2.95) | −8.27 (−10.94 to −5.60) | |||

| Hematocrit, % | 40.43 (39.62 to 41.24) | 1.36 (0.67 to 2.04) | <0.001 | −0.33 (−1.04 to 0.38) | 0.357 | 1.69 (0.76 to 2.62) | <0.001 |

| eGFR, mL/min per 1.73 m2 | 79.39 (74.63 to 84.16) | −0.71 (−3.90 to 2.74) | 0.660 | 1.25 (−1.94 to 4.43) | 0.440 | −1.96 (−6.29 to 2.37) | 0.373 |

| NT‐proBNP, log‐ng/L | 4.83 (4.57 to 5.11) | −0.25 (−0.53 to 0.03) | 0.077 | −0.12 (−0.40 to 0.16) | 0.412 | −0.12 (−0.52 to 0.26) | 0.506 |

| Weight, kg | 95.01 (91.14 to 98.88) | −0.14 (−2.78 to 1.99) | 0.893 | 0.86 (−1.30 to 3.03) | 0.432 | −1.01 (−4.04 to 2.02) | 0.512 |

| HR, bpm | 69.16 (66.66 to 71.66) | −0.88 (−3.47 to 1.71) | 0.503 | −0.94 (−3.45 to 1.56) | 0.459 | 0.06 (−3.47 to 3.60 | 0.972 |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 139.55 (136.18 to 142.92) | −5.55 (−10.59 to −0.51) | 0.031 | −2.93 (−7.57 to 1.71) | 0.213 | −2.62 (−9.28 to 4.05) | 0.439 |

Values are presented as means (95% CI)). BP indicates blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HR, heart rate; MFR, myocardial flow reserve; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide; RPP, rate‐pressure product; and TPD, total perfusion deficit.

Figure 2. Mean change in 82Rb‐PET/CT parameters after 13 weeks of treatment; whiskers indicate the 95% CI.

82Rb‐PET/CT indicates Rubidium‐82 positron emission tomography/computed tomography; MFR indicates myocardial flow reserve; RPP, rate‐pressure product; and TPD, total perfusion deficit.

Figure 3. Change in MFR from baseline to 13 weeks according to the pre‐defined subgroups. Dots indicate means, bars indicate 95% CI.

CAD indicates coronary artery disease; MFR, myocardial flow reserve; and MI, myocardial infarction.

Secondary Outcomes

We further adjusted the MFR for the rate‐pressure product to account for baseline workload. However, the adjusted MFR did not change in either the empagliflozin group (P=0.694) or in the placebo group (P=0.811), and no treatment effect (P=0.653) was observed (Table 2, Figure 2).

Myocardial Blood Flow at Rest and During Stress

In the empagliflozin group, between baseline and week 13, myocardial rest flow decreased by −0.10 mL/min per g (95% CI, −0.16 to −0.02; P=0.011) and, in the placebo group, the change was −0.15 mL/min per g (95% CI, −0.23 to −0.08; P<0.001). However, there was no difference between groups: +0.06 mL/min per g (95% CI, −0.03 to 0.15; P=0.176). In the per‐protocol analysis, there was no treatment effect on rest flow (P=0.188). The analysis of stress flow in the intention‐to‐treat population showed a reduction between baseline and week 13 in the empagliflozin group of −0.17 mL/min per g (95% CI, −0.34 to −0.01; P=0.044), as well as in the placebo group: −0.20 mL/min per g (95% CI, −0.38 to −0.03; P=0.025). However, at end of study, there was no treatment effect: −0.03 mL/min per g (95% CI, −0.19 to 0.26;, P=0.769). Additionally, no treatment effect on stress flow in the per‐protocol analysis (P=0.745) was observed.

Reversible Ischemia

In the intention‐to‐treat analysis of reversible ischemia, there was no significant change between baseline and week 13 in either group: empagliflozin: 0.74% (95% CI, −0.48 to 1.97; P=0.235), placebo: 0.08% (95% CI, −1.23 to 1.40; P=0.905), as well as no treatment effect 0.66% (95% CI, −1.04 to 0.66; P=0.443). There was also no significant treatment effect on reversible ischemic extent in the per‐protocol analysis (P=0.515).

Selected Clinical Parameters

Treatment with empagliflozin decreased HbA1c by 0.76% (95% CI, 1.00–0.51; P<0.001) compared with placebo after 13 weeks (Table 2), and increased hematocrit by 1.69% (95% CI, 0.76–2.62; P<0.001) in comparison with the control group at week 13. In contrast, there was no treatment effect on weight (P=0.512), estimated glomerular filtration rate (P=0.373), heart rate (P=0.972), or systolic blood pressure (P=0.439) between groups at week 13 (Table 2).

Safety

The treatment was generally well tolerated. In total, there were 69 reported adverse events. The most common adverse event was polyuria, which was reported by 15 participants, of which 14 belonged to the empagliflozin group. There were 5 serious adverse events in total, 3 in the placebo group and 2 in the empagliflozin group. Only 1 of the serious adverse events in the empagliflozin group, an admission for significant hypotension, was considered related to the treatment. There were no cases of diabetic ketoacidosis. The trial medication was considered an add‐on to best practice guidelines and did not replace the participants’ glucose‐lowering medication. Medication adherence was monitored systematically by adherence queries at scheduled telephone contacts and during a safety visit at the clinic.

Discussion

In the present SIMPLE trial, treatment with the SGLT2i empagliflozin did not change MFR quantified by 82Rb‐PET/CT after 13 weeks in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and high risk of cardiovascular events. Thus, this clinical trial does not support the hypothesis that the cardioprotective effect of empagliflozin, particularly as it relates to heart failure, is attributable to improved cardiac microcirculatory function. The present trial provides novel data on the actual mechanism underlying the heart failure prevention of the SGLT2i by investigating the effects on MFR by state‐of‐the‐art methods. In the EMPA‐REG OUTCOME and DECLARE‐TIMI 58 trials, the significant reduction in hospitalization for heart failure occurred within a few weeks.24 Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain the reduction in heart failure. However, only a few clinical randomized trials have reported on changes in cardiac function and structure with SGLT2i among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, and most of these studies of impact of cardiac function by echocardiography did not find any changes after 12 weeks.23, 25, 26

Impaired cardiac microcirculation has been a general finding in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, wherein their reduced vasodilator capacity is closely linked with myocardial function and with clinical symptoms of heart failure.27 MFR is a strong predictor of outcome in patients assessed for coronary heart disease and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Indeed, MFR measured by PET/CT provides substantial incremental risk stratification and carries independent prognostic value in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus.10 In experimental studies in rodents, treatment with SGLT2i improved coronary microvascular function and improved cardiac contractility in rodents.28 In patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, SGLT2i improves endothelial function, which plays a key role for MFR capacity.29 SGLT2i could thus improve cardiac microcirculation by reducing vascular stiffness and protecting endothelial glycocalyx from sodium overload.30 The potential functional role of cardiac microcirculation in heart failure7, 27 has been further underlined by the close link between impaired MFR and echocardiographic and hemodynamic important functional parameters of the left ventricle.31, 32 Therefore, we hypothesized that improvement of cardiac microcirculation could be part of the actual mechanisms behind the rapid decline in hospitalization for heart failure in the SGLT2i outcome trials. We did not, however, find any change with empagliflozin after 13 weeks, and several explanations could be considered. Nonadherence to the study medication may play a role, although it is contradicted by the finding of an expected decrease in HbA1c and increase in hematocrit among participants who received treatment with empagliflozin. The level of change in these 2 parameters was comparable to that which was reported in other SGLT2i trials. It is therefore unlikely that nonadherence was more significant in our study than it was in other SGLT2i trials. Given the relatively short treatment period of the present trial, it cannot be ruled out that more chronic SGLT2i treatment could improve MFR over a longer term. However, the Kaplan‐Meier curves for hospitalization for heart failure and for cardiovascular death separated within 13 weeks in the EMPA‐REG OUTCOME trial, such that any reasonable contribution from improved microvascular flow should have been detected. Consequently, we do not anticipate that duration of treatment explains the neutral finding regarding MFR in the present trial. The current study population was at high CVD risk and, thus, treated according to guidelines with high prevalence of evidence‐based medicine as statins and renin‐angiotensin system inhibitors, which are well known to affect endothelial function. It might be speculated that the high prevalence of concomitant treatment somewhat blunted the impact of SGLT2i on MFR. The mean MFR of 2.2 at baseline in the current trial suggests that, even though the patients were enrolled on the basis of known or high risk of CVD, their myocardial blood flow reserve was only moderately reduced as compared with previous type 2 diabetes mellitus study populations, wherein median values as low as 1.6 were reported.10, 33 The percentage of patients with previous myocardial infarction and significant coronary stenosis in the study by Murthy et al10, 33 was comparable to the 51% in our trial, and we did not find any effect modification on the presence of coronary heart disease in this trial. Therefore, the higher baseline MFR in the current trial and the fact that many participants had MFR in the normal range may, thus, partially explain the lack of treatment response. The secondary end points did not reveal a potential explanation for SGLT2i benefits, since we did not find any change in myocardial blood flow at rest or during stress per se, and no improvements in reversible myocardial ischemia were observed, which may be in contrast with Baker et al,34 who reported that treatment with canagliflozin improved cardiac stroke volume and work during induced ischemia.

Limitations

This was a single‐center study, with a relatively small number of participants. The study was powered to support the primary end point, and secondary end points must, therefore, be considered exploratory. If patients had been enrolled with impaired MFR as an inclusion criterion, this might have increased the power of the primary end point analysis. Furthermore, the study was powered to detect a treatment effect on MFR of 0.8. Based on our findings, the increase in MFR is probably <0.8, and a larger cohort would be required to observe a hypothetical, more modest effect. A higher‐than‐expected number of the participants did not complete all examinations for other reasons, including a period of the COVID‐19 lockdown in laboratory facilities. Dropouts were unbalanced between the groups: 3 from the empagliflozin group and 9 from the placebo group, which should be considered as a limitation. A high proportion of the participants were White men, and the conclusions of this study may, therefore, not necessarily extend to differently composed populations. In accordance with the study by Lauritsen et al,16 we found that rest myocardial blood flow decreased in the group that received empagliflozin. However, in contrast, we also found this to be the case for the placebo group. Further, stress flow also decreased in both groups. Stress and rest flow decreased with similar magnitudes, and therefore MFR was unchanged. A possible explanation for the observed decrease in flow could be that the second examination was less stressing for the participants because of familiarity with the procedure.

Conclusions

Treatment with empagliflozin for 13 weeks did not improve MFR among high‐risk patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Therefore, the present study does not support that change in MFR explains the immediate reductions in cardiovascular events observed in the SGLT2i outcome trials.

Sources of Funding

This work is supported by the Department of Internal Medicine at Herlev Hospital; the Research Council of Herlev Hospital; The Danish Heart Foundation, grant number 16‐R107‐A6697; The Hartmann Foundation; The Toyota Foundation and by a Steno Collaborative Grant 2018.

Disclosures

Dr Kistorp has served on scientific advisory panels and received speaker fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Merck Shape and Dome, Astra Zeneca, Amgen, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, and Shire. Dr Rossing has received consultancy and/or speaking fees (to his institution) from Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Gilead, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi Aventis; and research grants from AstraZeneca and Novo Nordisk. Dr Inzucchi has received consultancy and speaking fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, Novo Nordisk, Merck, and Esperion. Dr Wolsk has received speaker fees from Orion Pharma, Novartis Healthcare, Boehringer‐Ingelheim, and Merck. The remaining authors have no disclosures to report.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: Dr Jürgens executed the study, contributed to data collection, conducted statistical analyses, and wrote the manuscript. Drs Schou and Gustafsson designed and planned the trial, interpreted the data, and critically revised the manuscript. Dr Hasbak designed the trial, analyzed and interpreted the data, and critically revised the manuscript. Dr Kjær designed the trial, supervised the data, and critically revised the manuscript. Drs Wolsk, Zerahn, Faber, and Rossing planned the trial and critically revised the manuscript. Drs Wiberg, Brandt‐Jacobsen, and Gæde collected data, contributed to patient referrals, and revised the manuscript. Dr Inzucchi planned and consulted the trial, and critically revised the manuscript. Dr Kistorp conceptualized and planned the trial, wrote grant applications, and wrote the manuscript. Dr Kistorp, the guarantor of this work, has access to all the data and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analyses.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10:e020418. DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.120.020418.)

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 9.

References

- 1.Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, Fitchett D, Bluhmki E, Hantel S, Mattheus M, Devins T, Johansen OE, Woerle HJ, et al. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2015;2117–2128. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neal B, Perkovic V, Mahaffey KW, de Zeeuw D, Fulcher G, Erondu N, Shaw W, Law G, Desai M, Matthews DR. Canagliflozin and cardiovascular and renal events in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2017;644–657. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1611925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wiviott SD, Raz I, Bonaca MP, Mosenzon O, Kato ET, Cahn A, Silverman MG, Zelniker TA, Kuder JF, Murphy SA, et al. Dapagliflozin and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2019;347–357. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1812389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verma S, McMurray JJV. SGLT2 inhibitors and mechanisms of cardiovascular benefit: a state‐of‐the‐art review. Diabetologia. 2018;2108–2117. DOI: 10.1007/s00125-018-4670-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee MMY, Petrie MC, McMurray JJV, Sattar N. How Do SGLT2 (sodium‐glucose cotransporter 2) inhibitors and GLP‐1 (glucagon‐like peptide‐1) receptor agonists reduce cardiovascular outcomes?: completed and ongoing mechanistic trials. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2020;506–522. DOI: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.119.311904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Birkeland KI, Bodegard J, Eriksson JW, Norhammar A, Haller H, Linssen GCM, Banerjee A, Thuresson M, Okami S, Garal‐Pantaler E, et al. Heart failure and chronic kidney disease manifestation and mortality risk associations in type 2 diabetes: a large multinational cohort study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020;1607–1618. DOI: 10.1111/dom.14074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paulus WJ, Tschöpe C. A novel paradigm for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: comorbidities drive myocardial dysfunction and remodeling through coronary microvascular endothelial inflammation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;263–271. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.02.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dryer K, Gajjar M, Narang N, Lee M, Paul J, Shah AP, Nathan S, Butler J, Davidson CJ, Fearon WF, et al. Coronary microvascular dysfunction in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Am J Physiol ‐ Heart and Circ Physiol. 2018;H1033–H1042. DOI: 10.1152/ajpheart.00680.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shah SJ, Lam CSP, Svedlund S, Saraste A, Hage C, Tan R‐S, Beussink‐Nelson L, Ljung Faxén U, Fermer ML, Broberg MA, et al. Prevalence and correlates of coronary microvascular dysfunction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: PROMIS‐HFpEF. Eur Heart J. 2018;3439–3450. DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murthy VL, Naya M, Foster CR, Gaber M, Hainer J, Klein J, Dorbala S, Blankstein R, Di Carli MF. Association between coronary vascular dysfunction and cardiac mortality in patients with and without diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2012;1858–1868. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.120402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taqueti VR, Solomon SD, Shah AM, Desai AS, Groarke JD, Osborne MT, Hainer J, Bibbo CF, Dorbala S, Blankstein R, et al. Coronary microvascular dysfunction and future risk of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J. 2018;840–849. DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Indorkar R, Kwong RY, Romano S, White BE, Chia RC, Trybula M, Evans K, Shenoy C, Farzaneh‐Far A. Global coronary flow reserve measured during stress cardiac magnetic resonance imaging is an independent predictor of adverse cardiovascular events. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;1686–1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin B, Koibuchi N, Hasegawa Y, Sueta D, Toyama K, Uekawa K, Ma MJ, Nakagawa T, Kusaka H, Kim‐Mitsuyama S. Glycemic control with empagliflozin, a novel selective SGLT2 inhibitor, ameliorates cardiovascular injury and cognitive dysfunction in obese and type 2 diabetic mice. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2014;d. DOI: 10.1186/s12933-014-0148-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oelze M, Kröller‐Schön S, Welschof P, Jansen T, Hausding M, Mikhed Y, Stamm P, Mader M, Zinßius E, Agdauletova S, et al. The sodium‐glucose co‐transporter 2 inhibitor empagliflozin improves diabetes‐induced vascular dysfunction in the streptozotocin diabetes rat model by interfering with oxidative stress and glucotoxicity. PLoS One. 2014;e112394. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sherman SE, Bell GI, Teoh H, Al‐Omran M, Connelly KA, Bhatt DL, Hess DA, Verma S. Canagliflozin improves the recovery of blood flow in an experimental model of severe limb ischemia. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2018;327–329. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2018.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lauritsen KM, Nielsen BRR, Tolbod LP, Johannsen M, Hansen J, Hansen TK, Wiggers H, Møller N, Gormsen LC, Søndergaard E. SGLT2 inhibition does not affect myocardial fatty acid oxidation or uptake, but reduces myocardial glucose uptake and blood flow in individuals with type 2 diabetes: a randomized double‐blind, placebo‐controlled crossover trial. Diabetes. 2021;800–808. DOI: 10.2337/db20-0921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jürgens M, Schou M, Hasbak P, Kjær A, Wolsk E, Zerahn B, Wiberg M, Brandt NH, Gæde PH, Rossing P, et al. Design of a randomised controlled trial of the effects of empagliflozin on myocardial perfusion, function and metabolism in type 2 diabetes patients at high cardiovascular risk (the SIMPLE trial). BMJ Open. 2019;e029098. DOI: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lortie M, Beanlands RSB, Yoshinaga K, Klein R, DaSilva JN, DeKemp RA. Quantification of myocardial blood flow with 82Rb dynamic PET imaging. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007;1765–1774. DOI: 10.1007/s00259-007-0478-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murthy VL, Bateman TM, Beanlands RS, Berman DS, Borges‐Neto S, Chareonthaitawee P, Cerqueira MD, deKemp RA, DePuey EG, Dilsizian V, et al. Clinical quantification of myocardial blood flow using PET: joint position paper of the SNMMI cardiovascular council and the ASNC. J Nucl Med. 2018;273–293. DOI: 10.2967/jnumed.117.201368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schindler TH, Schelbert HR, Quercioli A, Dilsizian V. Cardiac PET imaging for the detection and monitoring of coronary artery disease and microvascular health. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;623–640. DOI: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hachamovitch R, Rozanski A, Shaw LJ, Stone GW, Thomson LEJ, Friedman JD, Hayes SW, Cohen I, Germano G, Berman DS. Impact of ischaemia and scar on the therapeutic benefit derived from myocardial revascularization vs. medical therapy among patients undergoing stress‐rest myocardial perfusion scintigraphy. Eur Heart J. 2011;1012–1024. DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.von Scholten BJ, Hasbak P, Christensen TE, Ghotbi AA, Kjaer A, Rossing P, Hansen TW. Cardiac 82Rb PET/CT for fast and non‐invasive assessment of microvascular function and structure in asymptomatic patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2016;371–378. DOI: 10.1007/s00125-015-3799-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verma S, Mazer CD, Yan AT, Mason T, Garg V, Teoh H, Zuo F, Quan A, Farkouh ME, Fitchett DH, et al. Effect of empagliflozin on left ventricular mass in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and coronary artery disease: the EMPA‐HEART cardiolink‐6 randomized clinical trial. Circulation. 2019;1693–1702. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.042375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Griffin M, Rao VS, Ivey‐Miranda J, Fleming J, Mahoney D, Maulion C, Suda N, Siwakoti K, Ahmad T, Jacoby D, et al. Empagliflozin in heart failure. Circulation. 2020;1028–1039. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.045691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown AJM, Gandy S, McCrimmon R, Houston JG, Struthers AD, Lang CC. A randomized controlled trial of dapagliflozin on left ventricular hypertrophy in people with type two diabetes: the DAPA‐LVH trial. Eur Heart J. 2020;3421–3432. DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bonora BM, Vigili de Kreutzenberg S, Avogaro A, Fadini GP. Effects of the SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin on cardiac function evaluated by impedance cardiography in patients with type 2 diabetes. Secondary analysis of a randomized placebo‐controlled trial. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2019;1–9. DOI: 10.1186/s12933-019-0910-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Srivaratharajah K, Coutinho T, Dekemp R, Liu P, Haddad H, Stadnick E, Davies RA, Chih S, Dwivedi G, Guo A, et al. Reduced myocardial flow in heart failure patients with preserved ejection fraction. Circulation: Heart Failure. 2016;1–9. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.115.002562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adingupu DD, Göpel SO, Grönros J, Behrendt M, Sotak M, Miliotis T, Dahlqvist U, Gan LM, Jönsson‐Rylander AC. SGLT2 inhibition with empagliflozin improves coronary microvascular function and cardiac contractility in prediabetic ob/ob ‐/‐ mice. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2019;1–15. DOI: 10.1186/s12933-019-0820-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kramer CK, Zinman B. Sodium‐glucose cotransporter‐2 (SGLT‐2) inhibitors and the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Annu Rev Med. 2019;323–334. DOI: 10.1146/annurev-med-042017-094221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muskiet MHA, van Bommel EJM, van Raalte DH. Antihypertensive effects of SGLT2 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016;188–189. DOI: 10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00457-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kawata T, Daimon M, Miyazaki S, Ichikawa R, Maruyama M, Chiang SJ, Ito C, Sato F, Watada H, Daida H. Coronary microvascular function is independently associated with left ventricular filling pressure in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2015;1–8. DOI: 10.1186/s12933-015-0263-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Byrne C, Hasbak P, Kjaer A, Thune JJ, Køber L. Impaired myocardial perfusion is associated with increasing end‐systolic‐ and end‐diastolic volumes in patients with non‐ischemic systolic heart failure: a cross‐sectional study using Rubidium‐82 PET/CT. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2019;1–10. DOI: 10.1186/s12872-019-1047-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sørensen MH, Bojer AS, Pontoppidan JRN, Broadbent DA, Plein S, Madsen PL, Gæde P. Reduced myocardial perfusion reserve in type 2 diabetes is caused by increased perfusion at rest and decreased maximal perfusion during stress. Dia Care. 2020;1285–1292. DOI: 10.2337/dc19-2172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baker HE, Kiel AM, Luebbe ST, Simon BR, Earl CC, Regmi A, Roell WC, Mather KJ, Tune JD, Goodwill AG. Inhibition of sodium–glucose cotransporter‐2 preserves cardiac function during regional myocardial ischemia independent of alterations in myocardial substrate utilization. Basic Res Cardiol. 2019;114. DOI: 10.1007/s00395-019-0733-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]