Abstract

Background

Heart failure might be an important determinant in choosing coronary revascularization modalities. There was no previous study evaluating the effect of heart failure on long‐term clinical outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) relative to coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG).

Methods and Results

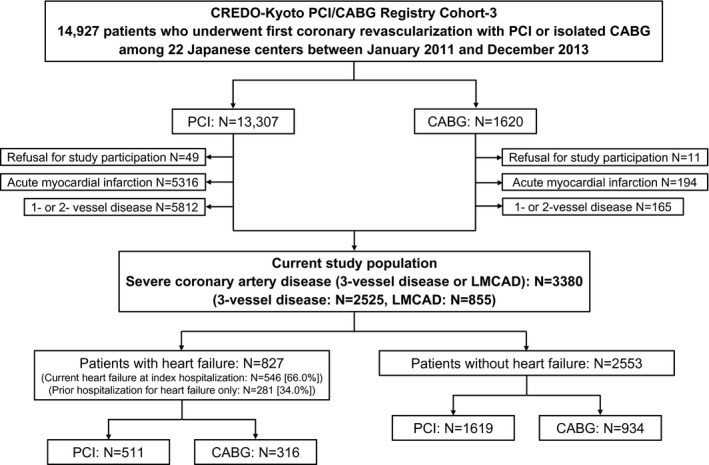

Among 14 867 consecutive patients undergoing first coronary revascularization with PCI or isolated CABG between January 2011 and December 2013 in the CREDO‐Kyoto PCI/CABG registry Cohort‐3, we identified the current study population of 3380 patients with three‐vessel or left main coronary artery disease, and compared clinical outcomes between PCI and CABG stratified by the subgroup based on the status of heart failure. There were 827 patients with heart failure (PCI: N=511, and CABG: N=316), and 2553 patients without heart failure (PCI: N=1619, and CABG: N=934). In patients with heart failure, the PCI group compared with the CABG group more often had advanced age, severe frailty, acute and severe heart failure, and elevated inflammatory markers. During a median 5.9 years of follow‐up, there was a significant interaction between heart failure and the mortality risk of PCI relative to CABG (interaction P=0.009), with excess mortality risk of PCI relative to CABG in patients with heart failure (HR, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.28–2.42; P<0.001) and no excess mortality risk in patients without heart failure (HR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.80–1.34; P=0.77).

Conclusions

There was a significant interaction between heart failure and the mortality risk of PCI relative to CABG with excess risk in patients with heart failure and neutral risk in patients without heart failure.

Keywords: coronary artery bypass grafting, coronary artery disease, heart failure, percutaneous coronary intervention

Subject Categories: Percutaneous Coronary Intervention, Cardiovascular Surgery, Heart Failure

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- 3VD

three‐vessel coronary artery disease

- LMCAD

left main coronary artery disease

- SYNTAX

Synergy between PCI with Taxus and Cardiac Surgery

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

According to a Japanese observational all‐comers registry database of patients who underwent first coronary revascularization for three‐vessel or left main disease, the excess mortality risk of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) relative to coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) was significant in patients with heart failure, whereas it was not significant in patients without heart failure, with significant interaction between heart failure and the mortality risk of PCI relative to CABG.

There were substantial baseline differences between the PCI and CABG groups in patients with heart failure, while those were generally well balanced in patients without heart failure.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Considering the possible presence of selection bias for coronary revascularization modality in patients with heart failure, we should be cautious in interpreting the results from the observational studies suggesting the higher mortality risk of PCI relative to CABG in patients with heart failure.

It was reassuring that the practice pattern in the present study was not associated with an excess long‐term mortality risk of PCI relative to CABG in patients with severe coronary artery disease and without heart failure.

Heart failure is a major public health burden worldwide in rapidly aging societies, and coronary artery disease (CAD) is one of the most common etiologies of heart failure. The STICHES (Surgical Treatment for Ischemic Heart Failure Extension Study) trial showed that coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) compared with medical therapy only was superior in improving survival in patients with systolic dysfunction,1 whereas there are currently no dedicated randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) versus medical therapy in patients with heart failure. The optimal revascularization strategy in CAD patients with heart failure is still controversial, because previous RCTs comparing PCI with CABG have excluded patients with heart failure, or included only a very small proportion of patients with heart failure.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 In the observational studies, there is a report that PCI had comparable long‐term survival outcomes to CABG in patients with multivessel disease and systolic dysfunction,8 while other studies have suggested that CABG had significant survival benefit as compared with PCI in CAD patients with systolic dysfunction and/or heart failure.9, 10, 11 At present, there was no previous study evaluating the effect of heart failure on long‐term clinical outcomes after PCI relative to CABG. Therefore, we sought to evaluate the effect of heart failure on long‐term clinical outcomes after PCI versus CABG in patients with severe CAD such as three‐vessel coronary artery disease (3VD) or left main coronary artery disease (LMCAD) in a large observational database of patients undergoing first coronary revascularization in Japan.

Methods

Study Design

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The CREDO‐Kyoto (Coronary Revascularization Demonstrating Outcome Study in Kyoto) PCI/CABG registry Cohort‐3 is a physician‐initiated, noncompany‐sponsored, multicenter registry enrolling consecutive patients who underwent first coronary revascularization with PCI or isolated CABG without combined noncoronary surgery among 22 Japanese centers between January 2011 and December 2013. Among 14 927 patients enrolled in the registry, we excluded those patients who refused study participation (N=60), acute myocardial infarction (N=5510), and one‐ or two‐vessel disease (N=5977), and the current study population consisted of 3380 patients with severe CAD (3VD: N=2525, and LMCAD: N=855) (Figure 1). In this study, we compared long‐term clinical outcomes between PCI and CABG stratified by the subgroup based on the status of heart failure. Heart failure was defined as having been diagnosed with heart failure at index hospitalization for coronary revascularization, and/or prior hospitalization for heart failure regardless of left ventricular ejection fraction. Heart failure at index hospitalization for coronary revascularization was defined as New York Heart Association (NYHA) class greater than or equal to II.

Figure 1. Study flowchart.

CABG indicates coronary artery bypass grafting; CREDO‐Kyoto PCI/CABG Registry Cohort‐3, Coronary Revascularization Demonstrating Outcome study in Kyoto PCI/CABG Registry Cohort‐3; LMCAD, left main coronary artery disease; and PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

The relevant ethics committees in all the participating centers approved the study protocol. Because of the retrospective enrollment, written informed consents from the patients were waived; however, we excluded those patients who refused participation in the study when contacted for follow‐up. This strategy is concordant with the guidelines of the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measure was all‐cause death. The secondary outcome measures included cardiovascular death, noncardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, stroke, hospitalization for heart failure, major bleeding, and any coronary revascularization. Definitions of the outcome measures were described in Appendix S1.

Data Collection

Clinical, angiographic, and procedural data were collected from hospital charts or hospital databases according to the pre‐specified definitions by the experienced clinical research coordinators belonging to an independent clinical research organization (Research Institute for Production Development, Kyoto, Japan). Follow‐up data were collected from the hospital charts and/or obtained by contacting with patients, their relatives, or referring physicians. The clinical event committee adjudicated those events such as death, myocardial infarction, stroke, and major bleeding. Coronary anatomic complexity was evaluated according to the SYNTAX (Synergy between PCI with Taxus and Cardiac Surgery) score, which was evaluated by the experienced cardiologists (Appendix S1).

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were presented as number and percentage, and compared with the chi‐square test. Continuous variables were expressed as mean±standard deviation or median and interquartile range (IQR). Continuous variables were compared with the Student t test or Wilcoxon rank sum test based on their distributions. Cumulative incidence of the outcome measures was estimated by the Kaplan‐Meier method, and the differences were assessed with the log‐rank test. The effects of PCI relative to CABG for the outcome measures were estimated by the Cox proportional hazard models, and were expressed as hazard ratios (HRs) and their 95% CIs. The adjusted HRs were estimated by the multivariable Cox proportional hazard models adjusting for the 26 clinically relevant factors listed in Table. To avoid overfitting for the outcome measures with <100 patients with event, we constructed the parsimonious models with 7 risk‐adjusting variables (age ≥75 years, men, diabetes mellitus, prior myocardial infarction, prior stroke, estimated glomerular filtration rate <30 mL/min per 1.73 m2 or hemodialysis, and severe frailty). In patients with heart failure, the primary outcome measure was compared between PCI and CABG in the subgroups stratified by heart failure presentation (current heart failure at index hospitalization or prior hospitalization for heart failure only), NYHA classification, and left ventricular ejection fraction. In this analysis, the multivariable analysis was performed with the parsimonious model described above. As a sensitivity analysis, we performed the main analysis after excluding patients with surgical ineligibility. Moreover, as a sensitivity analysis, we performed the adjusted analysis including SYNTAX score as a continuous explanatory variable in the model in 3129 (92.6%) patients whom the SYNTAX score was available. Statistical analyses were performed with JMP 14.0 software (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). All statistical analyses were 2‐tailed, and P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Table .

Baseline Characteristics

| With Heart Failure (N=827) | Without Heart Failure (N=2553) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCI (N=511) | CABG (N=316) | P value | PCI (N=1619) | CABG (N=934) | P value | |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||||

| Age, y | 72.4±11.9 | 69.7±9.9 | 0.001 | 70.3±9.9 | 69.1±9.2 | 0.002 |

| ≥75* | 248 (48.5) | 117 (37.0) | 0.001 | 589 (36.4) | 275 (29.4) | <0.001 |

| Men* | 341 (66.7) | 235 (74.4) | 0.02 | 1225 (75.7) | 743 (79.6) | 0.02 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 23.5±4.2 | 23.4±3.8 | 0.68 | 24.0±3.5 | 23.8±3.4 | 0.22 |

| <25.0* | 356 (69.7) | 222 (70.3) | 0.86 | 1066 (65.8) | 628 (67.2) | 0.47 |

| Unstable angina | 13 (2.5) | 9 (2.8) | 0.79 | 39 (2.4) | 25 (2.7) | 0.68 |

| Blood pressure at index hospitalization, mm Hg | ||||||

| Systolic | 137±28 | 124±23 | <0.001 | 136±20 | 129±19 | <0.001 |

| Diastolic | 77±18 | 68±14 | <0.001 | 74±13 | 70±12 | <0.001 |

| Heart rate at index hospitalization, bpm | 85±21 | 75±16 | <0.001 | 74±14 | 73±13 | 0.14 |

| Hypertension* | 448 (87.7) | 281 (88.9) | 0.59 | 1397 (86.3) | 770 (82.4) | 0.009 |

| Diabetes mellitus* | 295 (57.7) | 204 (64.6) | 0.051 | 756 (46.7) | 450 (48.2) | 0.47 |

| On insulin therapy | 95 (18.6) | 96 (30.4) | <0.001 | 207 (12.8) | 153 (16.4) | 0.01 |

| Current smoking* | 101 (19.8) | 68 (21.5) | 0.54 | 344 (21.2) | 140 (15.0) | <0.001 |

| Prior hospitalization for heart failure | 184 (36.0) | 215 (68.0) | <0.001 | |||

| Current heart failure at index hospitalization | 399 (78.1) | 147 (46.5) | <0.001 | |||

| NYHA II | 198 (38.7) | 114 (36.1) | <0.001 | |||

| NYHA III | 136 (26.6) | 23 (7.3) | ||||

| NYHA IV | 65 (12.7) | 10 (3.2) | ||||

| LVEF | 47.4±15.5 | 48.5±14.5 | 0.31 | 62.4±10.8 | 63.1±11.8 | 0.14 |

| <40% | 161 (34.6) | 91 (30.4) | 0.47 | 43 (3.1) | 40 (4.5) | 0.15 |

| 40–50% | 101 (21.7) | 71 (23.8) | 122 (8.8) | 88 (9.9) | ||

| ≥50% | 203 (43.7) | 137 (45.8) | 1216 (88.1) | 763 (85.6) | ||

| Mitral regurgitation grade ≥3/4 | 86 (18.5) | 42 (14.0) | 0.1 | 55 (3.9) | 42 (4.7) | 0.38 |

| Prior myocardial infarction* | 217 (42.5) | 110 (34.8) | 0.03 | 255 (15.8) | 181 (19.4) | 0.02 |

| Prior stroke* | 99 (19.4) | 60 (19.0) | 0.89 | 269 (16.6) | 158 (16.9) | 0.84 |

| Peripheral vascular disease* | 62 (12.1) | 41 (13.0) | 0.72 | 245 (15.1) | 113 (12.1) | 0.03 |

| eGFR <30 mL/min per 1.73 m2 or hemodialysis | 114 (22.3) | 71 (22.5) | 0.96 | 149 (9.2) | 97 (10.4) | 0.33 |

| eGFR <30 mL/min per 1.73 m2, without hemodialysis* | 53 (10.4) | 39 (12.3) | 0.38 | 51 (3.2) | 32 (3.4) | 0.7 |

| Hemodialysis* | 61 (11.9) | 32 (10.1) | 0.42 | 98 (6.1) | 65 (7.0) | 0.37 |

| Atrial fibrillation* | 87 (17.0) | 43 (13.6) | 0.19 | 105 (6.5) | 49 (5.2) | 0.21 |

| Hemoglobin <11.0 g/dL* | 163 (31.9) | 96 (30.4) | 0.65 | 211 (13.0) | 123 (13.2) | 0.92 |

| Platelet <100×109/L* | 15 (2.9) | 12 (3.8) | 0.5 | 25 (1.5) | 18 (1.9) | 0.47 |

| White blood cell, ×103 cells/μL | 6.8 (5.5–8.7) | 6.0 (5.0–7.3) | <0.001 | 6.0 (5.0–7.3) | 6.0 (5.0–7.1) | 0.62 |

| CRP, mg/dL | 0.43 (0.14–1.60) | 0.20 (0.10–0.68) | <0.001 | 0.12 (0.06–0.3) | 0.13 (0.06–0.33) | 0.21 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease* | 27 (5.3) | 27 (8.5) | 0.07 | 53 (3.3) | 50 (5.4) | 0.01 |

| Liver cirrhosis* | 16 (3.1) | 8 (2.5) | 0.62 | 47 (2.9) | 24 (2.6) | 0.62 |

| Malignancy | 62 (12.1) | 34 (10.8) | 0.55 | 227 (14.0) | 106 (11.3) | 0.053 |

| Active malignancy* | 17 (3.3) | 6 (1.9) | 0.22 | 40 (2.5) | 21 (2.2) | 0.72 |

| Severe frailty* , † | 51 (10.0) | 9 (2.8) | <0.001 | 42 (2.6) | 14 (1.5) | 0.07 |

| Surgical ineligibility‡ | 54 (10.6) | 66 (4.1) | ||||

| Procedural characteristics | ||||||

| Number of target lesions or anastomoses | 2.0±1.0 | 3.4±0.9 | <0.001 | 2.1±1.0 | 3.4±0.9 | <0.001 |

| Target of proximal LAD* | 326 (63.8) | 275 (87.0) | <0.001 | 1045 (64.5) | 816 (87.4) | <0.001 |

| Target of chronic total occlusion* | 124 (24.3) | 139 (44.0) | <0.001 | 311 (19.2) | 355 (38.0) | <0.001 |

| 3‐vessel disease | 410 (80.2) | 203 (64.2) | <0.001 | 1337 (82.6) | 575 (61.6) | <0.001 |

| LMCA disease | 101 (19.8) | 113 (35.8) | <0.001 | 282 (17.4) | 359 (38.4) | <0.001 |

| Isolated LMCA | 7 (1.4) | 0 (0) | <0.001 | 18 (1.1) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| LMCA+1‐vessel disease | 19 (3.7) | 0 (0) | 76 (4.7) | 6 (0.6) | ||

| LMCA+2‐vessel disease | 30 (5.9) | 23 (7.3) | 97 (6.0) | 103 (11.0) | ||

| LMCA+3‐vessel disease | 45 (8.8) | 89 (28.2) | 91 (5.6) | 250 (26.8) | ||

| SYNTAX score | 26 (20–32) | 31 (25–37) | <0.001 | 23 (17–29) | 29 (23–35) | <0.001 |

| Low <23 | 185 (36.5) | 45 (18.0) | <0.001 | 777 (48.5) | 175 (22.8) | <0.001 |

| Intermediate 23–32 | 205 (40.4) | 96 (38.4) | 574 (35.8) | 323 (42.0) | ||

| High ≥33 | 117 (23.1) | 109 (43.6) | 252 (15.7) | 271 (35.2) | ||

| Total number of stents | 2 (2–4) | 3 (2–4) | … | |||

| Total stent length, mm | 54 (33–87) | 56 (31–90) | … | |||

| DES use | 472 (92.4) | 1482 (91.5) | … | |||

| New‐generation DES use | 463 (90.6) | 1460 (90.2) | … | |||

| IVUS or OCT use | 424 (83.0) | 1353 (83.6) | … | |||

| Internal thoracic artery graft use | 309 (97.8) | 911 (97.5) | … | |||

| Off pump surgery | 186 (58.9) | 561 (60.1) | … | |||

| Interval from index hospitalization to procedure, d | 6 (1–14) | 3 (1–5) | <0.001 | 1 (0–3) | 3 (2–5) | <0.001 |

| Baseline medications | ||||||

| Thienopyridine | 510 (99.8) | 76 (24.1) | <0.001 | 1608 (99.3) | 194 (20.8) | <0.001 |

| Aspirin | 507 (99.2) | 310 (98.1) | 0.15 | 1608 (99.3) | 922 (98.7) | 0.12 |

| Statins* | 359 (70.3) | 190 (60.1) | 0.003 | 1214 (75.0) | 600 (64.2) | <0.001 |

| Beta‐blockers* | 275 (53.8) | 171 (54.1) | 0.93 | 501 (30.9) | 493 (52.8) | <0.001 |

| ACE‐I/ARB* | 368 (72.0) | 111 (35.1) | <0.001 | 959 (59.2) | 255 (27.3) | <0.001 |

| Calcium channel blockers* | 190 (37.2) | 104 (32.9) | 0.21 | 883 (54.5) | 365 (39.1) | <0.001 |

| Oral anticoagulants* | 94 (18.4) | 157 (49.7) | <0.001 | 103 (6.4) | 487 (52.1) | <0.001 |

| Proton pump inhibitors or histamine type‐2 receptor blockers* | 406 (79.5) | 298 (94.3) | <0.001 | 1148 (70.9) | 876 (93.8) | <0.001 |

Continuous variables were expressed as mean±standard deviation, or median (interquartile range). Categorical variables were expressed as number (percentage). Values were missing for LVEF in 344 patients, for mitral regurgitation in 319 patients, and for SYNTAX score in 251 patients. ACE‐I indicates angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blockers; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CRP, C‐reactive protein; DES, drug‐eluting stent; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; IVUS, intravascular ultrasound; LAD, left anterior descending coronary artery; LMCA, left main coronary artery; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; OCT, optical coherence tomography; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; and SYNTAX, SYNergy between percutaneous coronary intervention with TAXus and cardiac surgery.

Risk adjusting variables selected for the Cox proportional hazard models.

Severe frailty was regarded as present when the inability to perform usual activities of daily living was documented in the hospital charts.

Surgical ineligibility was regarded as present when the term such as “contraindicated for surgery” or “too high risk for surgery” were documented in hospital charts.

Results

Study Population

In this study population of 3380 patients with severe CAD, there were 827 patients with heart failure (PCI: N=511, and CABG: N=316), and 2553 patients without heart failure (PCI: N=1619, and CABG: N=934) (Figure 1). The proportion of PCI/CABG was similar in patients with and without heart failure. Among 827 patients with heart failure, there were 546 patients with current heart failure at index hospitalization (PCI: N=399, and CABG: N=147), and 281 patients with prior hospitalization for heart failure only (PCI: N=112, and CABG: N=169). PCI was more often chosen in patients with current heart failure at index hospitalization, particularly in patients with severe current heart failure at index hospitalization (NYHA class III or IV) (Table S1).

Baseline Characteristics

Patients with heart failure were older, and more often women, and more often had comorbidities, frailty, surgical ineligibility, and complex coronary anatomy than in those without heart failure (Table S2).

In patients both with and without heart failure, the PCI group were older, and more often women than the CABG group. In patients with heart failure, the PCI group more often had current heart failure at index hospitalization and severe heart failure than the CABG group. The PCI group had higher inflammatory markers, and higher prevalence of frailty than the CABG group in patients with heart failure, but not in patients without heart failure. Interval from hospitalization to index procedure was significantly longer in the PCI group than in the CABG group in patients with heart failure, while it was significantly longer in the CABG group than in the PCI group in patients without heart failure. Regarding angiographic and procedural characteristics, the CABG group compared with the PCI group had greater number of target lesions or anastomoses, and higher coronary anatomic complexity regardless of heart failure (Table).

Baseline characteristics in patients with 3VD and LMCAD were consistent with those in the entire study population (Tables S3 and S4).

Regarding the baseline characteristics stratified by the current heart failure at index hospitalization or prior hospitalization only, the PCI group had higher inflammatory markers, and higher prevalence of advanced age, mitral regurgitation, prior myocardial infarction, and frailty than the CABG group in patients with current heart failure at index hospitalization, but not in patients with prior hospitalization for heart failure only. Interval from hospitalization to index procedure was significantly longer in the PCI group than in the CABG group in patients with current heart failure at index hospitalization, while it was significantly longer in the CABG group than in the PCI group in patients with prior hospitalization for heart failure only (Table S5).

Long‐Term Follow‐Up

Median follow‐up for survivors was 5.9 (IQR: 5.1–6.8) years: (with heart failure: 5.8 [IQR: 4.8–6.6], and without heart failure: 5.9 [IQR: 5.1–6.8]). Complete 1‐, 3‐, and 5‐year follow‐up rates were lower in the CABG group than in the PCI group (with heart failure: 92.1% versus 96.5%, 90.2% versus 93.0%, and 79.4% versus 82.8%, and without heart failure: 92.6% versus 98.1%, 90.5% versus 95.7%, and 81.1% versus 83.6%).

Survival Outcomes

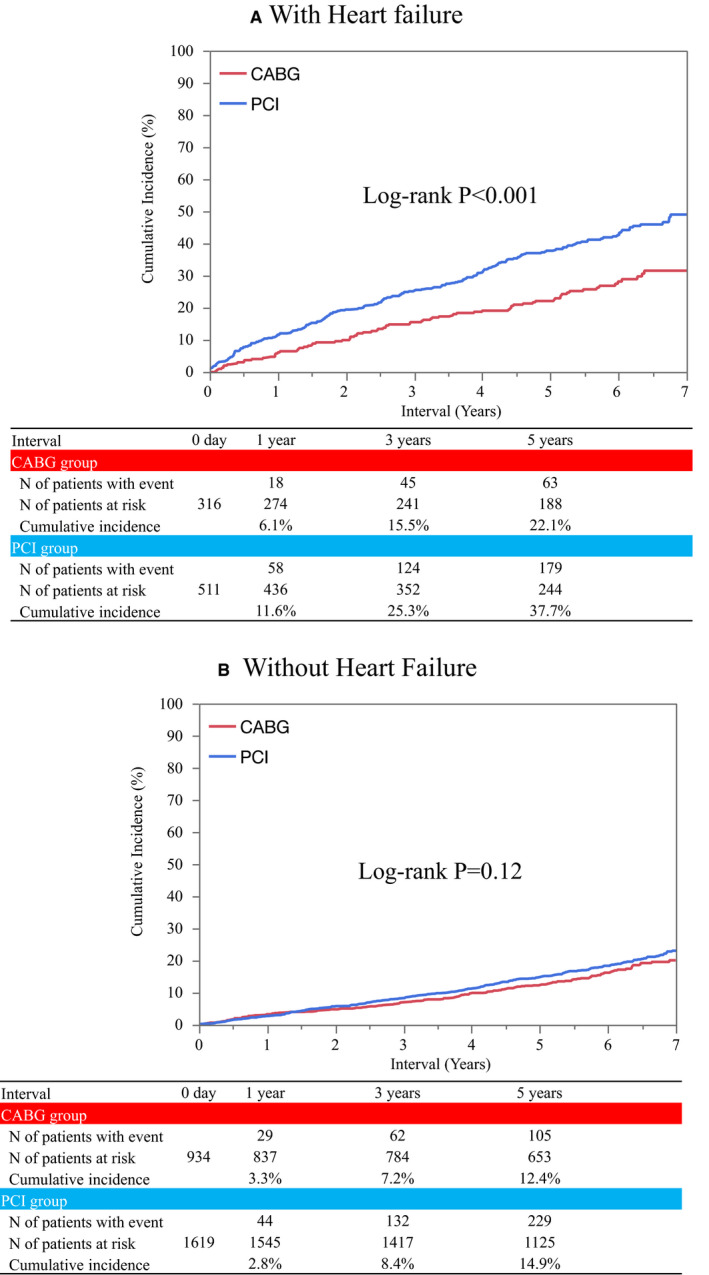

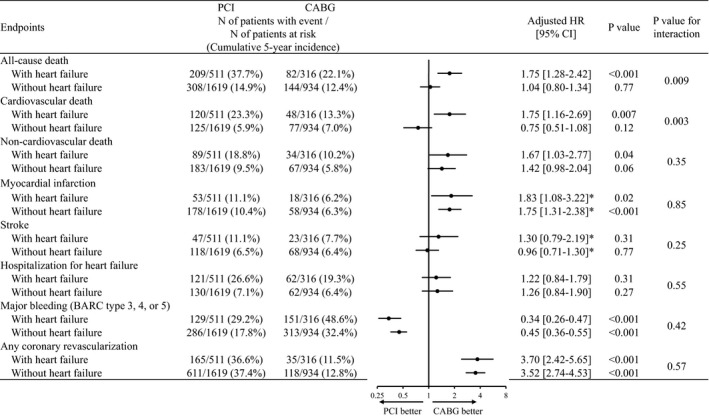

In patients with heart failure, the cumulative 5‐year incidence of all‐cause death was significantly higher in the PCI group than in the CABG group (37.7% versus 22.1%, log‐rank P<0.001) (Figure 2). After adjusting confounders, the excess mortality risk of PCI relative to CABG remained significant (HR, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.28–2.42; P<0.001) (Figure 3). The PCI group compared with the CABG group was associated with higher adjusted risks for both cardiovascular and noncardiovascular death (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Kaplan‐Meier event curves for all‐cause death in patients (A) with heart failure, and (B) without heart failure.

CABG indicates coronary artery bypass grafting; CREDO‐Kyoto PCI/CABG Registry Cohort‐3, Coronary Revascularization Demonstrating Outcome study in Kyoto PCI/CABG Registry Cohort‐3; LMCAD, left main coronary artery disease; and PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Figure 3. Forrest plots for the adjusted hazard ratios of PCI relative to CABG for clinical outcomes.

Number of patients with event was counted throughout the entire follow‐up period, while the cumulative incidence was estimated at 5 years. BARC indicates Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CREDO‐Kyoto PCI/CABG Registry Cohort‐3, Coronary Revascularization Demonstrating Outcome study in Kyoto PCI/CABG Registry Cohort‐3; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HR, hazard ratio; LMCAD, left main coronary artery disease; and PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

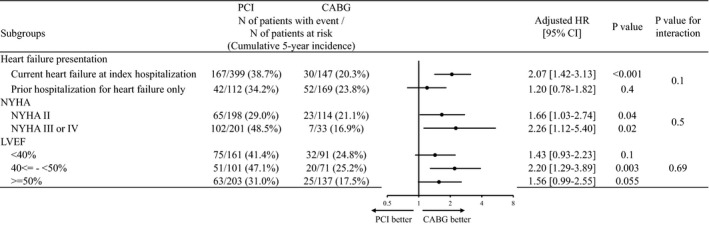

In the subgroup analysis stratified by heart failure presentation, the excess adjusted risk of PCI relative to CABG was significant for all‐cause death in patients with current heart failure at index hospitalization (HR, 2.07; 95% CI, 1.42–3.13; P<0.001), while it was not significant in patients with prior hospitalization for heart failure only (HR, 1.20; 95% CI, 0.78–1.82; P=0.4) (Figure 4 and Figure S1).

Figure 4. Subgroup analysis for all‐cause death in patients with heart failure.

Values were missing for LVEF in 344 patients. Number of patients with event was counted throughout the entire follow‐up period, while the cumulative incidence was estimated at 5 years. BARC indicates Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CREDO‐Kyoto PCI/CABG Registry Cohort‐3, Coronary Revascularization Demonstrating Outcome study in Kyoto PCI/CABG Registry Cohort‐3; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HR, hazard ratio; LMCAD, left main coronary artery disease; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; and PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

In patients without heart failure, the cumulative 5‐year incidence of all‐cause death was not significantly different between the PCI and CABG groups (14.9% versus 12.4%, log‐lank P=0.12) (Figure 2). After adjusting confounders, the risk of PCI relative to CABG remained insignificant for all‐cause death (HR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.80–1.34; P=0.77) (Figure 3). There was significant interaction between heart failure and the effects of PCI relative to CABG for all‐cause death (interaction P=0.009). Excess adjusted risk of PCI relative to CABG also was not significant for both cardiovascular and noncardiovascular death in patients without heart failure (Figure 3).

Survival outcomes in patients with 3VD and LMCAD were consistent with those in the entire study population (Tables S6 and S7). In the sensitivity analysis after excluding patients with surgical indelibility, the results were fully consistent with those in the main analysis (Table S8). In the sensitivity analysis of the model including SYNTAX score as an explanatory variable, the results were fully consistent with those in the main analysis (Table S9). In the subgroup analysis stratified by NYHA classification and left verntricular ejection fraction in patients with heart failure, there were no significant interactions between the subgroup factors and the effect of PCI relative to CABG for all‐cause death (Figure 4 and Figure S2).

Other Clinical Outcomes

In patients both with and without heart failure, the excess adjusted risk of PCI relative to CABG was significant for myocardial infarction, and any coronary revascularization, while it was not significant for stroke, and hospitalization for heart failure. There was a significantly lower risk of PCI relative to CABG for major bleeding in patients both with and without heart failure. There was no significant interaction between heart failure and the effects of PCI relative to CABG for all the outcome measures other than survival outcomes (Figure 3).

Discussion

The main finding of this study comparing PCI with CABG in patients with severe CAD was that there was a significant interaction between heart failure and the mortality risk of PCI relative to CABG with excess risk in patients with heart failure and neutral risk in patients without heart failure.

In this study, PCI compared with CABG was associated with a significant excess mortality risk in patients with heart failure, whereas the mortality risk was neutral in patients without heart failure. One of the reasons for the different mortality risk of PCI relative to CABG might be related to the difference of baseline clinical characteristics between those with and without heart failure. In this study, patients with heart failure more often had systolic dysfunction and high SYNTAX score compared with those without. CABG might be more suitable in patients with heart failure with complex coronary anatomy and/or systolic dysfunction, because in previous reports, CABG was associated with lower mortality risk compared with PCI in patients with systolic dysfunction, or high SYNTAX score.9, 10, 12 However, there were substantial baseline differences between the PCI and CABG groups in patients with heart failure, while those were generally well balanced in patients without heart failure. In patients with heart failure, the PCI group compared with the CABG group had higher prevalence of advanced age, frailty, acute and severe heart failure, and elevated inflammatory markers. The interval from hospitalization to index procedure was longer in the PCI group than in the CABG group, suggesting that there were substantial proportion of patients who could not undergo PCI quickly due to severe hemodynamic or respiratory condition, and/or infection at index hospitalization in the PCI group. In this study, more than 60% of the patients were treated with PCI in the entire cohort, while more than 70% of the patients with acute heart failure, and more than 80% of the patients with severe acute heart failure were treated with PCI as the coronary revascularization modality, even though the current clinical guidelines recommend CABG as the revascularization modality in patients with heart failure.13, 14 Therefore, we cannot rule out the possibility of selection bias toward choosing PCI in sicker patients in this study, although the higher mortality risk of PCI relative to CABG in patients with heart failure was consistent with previous studies.9, 10, 11 The excess adjusted risk of PCI relative to CABG for noncardiovascular death in patients with heart failure might also suggest the presence of selection bias. Indeed, there was no excess mortality risk of PCI relative to CABG in patients with prior hospitalization for heart failure only, whose baseline characteristics were relatively better balanced between the PCI and CABG groups than in those with current heart failure at index hospitalization. Considering the possible presence of selection bias for coronary revascularization modality in patients with heart failure, we should be cautious in interpreting the results from the observational studies suggesting the higher mortality risk of PCI relative to CABG in patients with heart failure.

It is noteworthy that there was no excess mortality risk of PCI relative to CABG in patients without heart failure in this study. In a meta‐analysis of individual patient data from RCTs in patients with multivessel disease, there was no significant mortality risk of PCI relative to CABG in patients with low SYNTAX score, while PCI had higher mortality risk than CABG in patients with intermediate or high SYNTAX score.12 In a meta‐analysis of individual patient data from RCTs in patients with LMCAD, the mortality risk was similar between PCI and CABG, although the mortality risk trended to be higher in PCI than in CABG in those with high SYNTAX score.12 Based on these results, the current clinical guidelines recommend that CABG remains standard revascularization modality for patients with severe CAD, although PCI is recommended as a good alternative to CABG only in patients without diabetes mellitus, with low SYNTAX score in patients with 3VD, and only in patients with low or intermediate SYNTAX score in patients with LMCAD.13, 14 In this study reflecting real clinical practice, PCI was chosen in more than 60% of patients with severe CAD and without heart failure, although patients treated with PCI had less complex coronary anatomy than those treated with CABG. The baseline characteristics were better balanced between the PCI and CABG groups in patients without heart failure than in patients with heart failure, suggesting that selection bias toward sicker patients in the PCI group was less apparent in patients without heart failure than in patients with heart failure. It was reassuring that the practice pattern in the present study was not associated with an excess long‐term mortality risk of PCI relative to CABG in patients with severe CAD and without heart failure.

Study Limitations

There were several important limitations in this study. First, patients were not randomly allocated to each coronary revascularization strategy. Analysis with propensity score might be an option to take into account the differences in baseline characteristics and the potential selection bias. However, even analysis with propensity score could not address unmeasured confounders, and the sample size was limited in the current study population to provide a plausible propensity score, particularly in the subgroup of heart failure. Hence, we conducted some multivariable models as sensitivity analyses. Especially in patients with heart failure, we could not deny the presence of the unmeasured confounders and some ascertainment bias, although we conducted extensive multivariable adjustment for the known confounders. In fact, patients with heart failure more often had surgical ineligibility than in patients without heart failure. The results after excluding patients with surgical ineligibility were consistent with the main results, although the seemingly very low prevalence of inoperable patients would suggest imperfect ascertainment of inoperable status in this retrospective study. In addition, we evaluated severe frailty defined as documentation of the inability to perform usual activities of daily living in the hospital charts. However, we could not deny ascertainment bias for severe frailty, because the prevalence of severe frailty in the present study was lower than those reported in previous studies.15 Furthermore, due to the retrospective study design, we could not assess other important factors such as moderate frailty and cognitive impairment, which might have great influence on the choice between PCI and CABG, as well as on clinical outcomes. In patients without heart failure, patient selection and intervention biases should also be considered as the baseline patient or lesion characteristics were different between PCI and CABG, which could prevent generalization of the results and decision making in daily practice. Second, we might not have adequate statistical power in this subgroup analysis stratified by heart failure. However, we had enough number of patients with all‐cause death to make extensive multivariable adjustment, and found a positive interaction between heart failure and the mortality risk of PCI relative to CABG. Third, the follow‐up rate was suboptimal, and complete follow‐up rate was lower in the CABG group than in the PCI group. The incidences of adverse event might have been underestimated in the CABG group. Fourth, as we excluded acute myocardial infarction patients in this study, the results of this study cannot be applied to those with non‐ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction as well as ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction. Finally, the assessment of lesion‐specific ischemia by fractional flow reserve was performed only in a small proportion of patients in the PCI group, which were different from the current clinical practice. Moreover, it was unknown whether the patients underwent complete or incomplete revascularization as the residual SYNTAX scores were not obtained.

Conclusions

There was a significant interaction between heart failure and the mortality risk of PCI relative to CABG with excess risk in patients with heart failure and neutral risk in patients without heart failure.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by an educational grant from the Research Institute for Production Development (Kyoto, Japan).

Disclosures

Dr Shiomi reports personal fees from Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, and Daiichi Sankyo. Dr Morimoto reports lecturer's fees from Bayer, Daiichi Sankyo, Japan Lifeline, Kyocera, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Novartis, and Toray, and the manuscript fees from Bristol‐Myers Squibb and Kowa, and served advisory boards for Asahi Kasei, Boston Scientific, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, and Sanofi. Dr Furukawa reports personal fees from Bayer, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Kowa, Ono Pharmaceutical, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Sanofi, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, and Takeda Pharmaceutical. Dr Nakagawa reports grant from Abbott Vascular and Boston Scientific, and reports personal fees from Abbott Vascular, Bayer, Boston Scientific, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, and Daiichi Sankyo. Dr Kimura reports personal fees from Abbott Vascular, Abiomed, Astellas, Astellas Amgen Biopharma, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boston Scientific, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Edwards Lifescience, Eisai, Daiichi Sankyo, Interscience, Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, Kowa, Kowa Pharmaceutical, Lifescience, Medical Review, MSD, MSD Life Science Foundation, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Novartis Pharma, Ono Pharmaceutical, OrbusNeich, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency, Philips, Public Health Research Foundation, Sanofi, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Terumo, Toray, Tsumura. The remaining authors have no disclosures to report.

Supporting information

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the support and collaboration of the co‐investigators participating in the CREDO‐Kyoto PCI/CABG Registry Cohort‐3. We are indebted to the clinical research coordinators for data collection.

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 11.

References

- 1.Velazquez EJ, Lee KL, Jones RH, Al‐Khalidi HR, Hill JA, Panza JA, Michler RE, Bonow RO, Doenst T, Petrie MC, et al. Coronary‐artery bypass surgery in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1511–1520. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thuijs DJFM, Kappetein AP, Serruys PW, Mohr F‐W, Morice M‐C, Mack MJ, Holmes DR, Curzen N, Davierwala P, Noack T, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary artery bypass grafting in patients with three‐vessel or left main coronary artery disease: 10‐year follow‐up of the multicentre randomised controlled SYNTAX trial. Lancet. 2019;394:1325–1334. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31997-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farkouh ME, Domanski M, Sleeper LA, Siami FS, Dangas G, Mack M, Yang M, Cohen DJ, Rosenberg Y, Solomon SD, et al. Strategies for multivessel revascularization in patients with diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2375–2384. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park S‐J, Ahn J‐M, Kim Y‐H, Park D‐W, Yun S‐C, Lee J‐Y, Kang S‐J, Lee S‐W, Lee CW, Park S‐W, et al. Trial of everolimus‐eluting stents or bypass surgery for coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1204–1212. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1415447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park D‐W, Ahn J‐M, Park H, Yun S‐C, Kang D‐Y, Lee PH, Kim Y‐H, Lim D‐S, Rha S‐W, Park G‐M, et al. Ten‐year outcomes after drug‐eluting stents versus coronary artery bypass grafting for left main coronary disease: extended follow‐up of the PRECOMBAT trial. Circulation. 2020;141:1437–1446. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.046039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stone GW, Kappetein AP, Sabik JF, Pocock SJ, Morice M‐C, Puskas J, Kandzari DE, Karmpaliotis D, Brown WM, Lembo NJ, et al. Five‐year outcomes after PCI or CABG for left main coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1820–1830. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1909406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holm NR, Mäkikallio T, Lindsay MM, Spence MS, Erglis A, Menown IBA, Trovik T, Kellerth T, Kalinauskas G, Mogensen LJH, et al. Percutaneous coronary angioplasty versus coronary artery bypass grafting in the treatment of unprotected left main stenosis: updated 5‐year outcomes from the randomised, non‐inferiority NOBLE trial. Lancet. 2020;395:191–199. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32972-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bangalore S, Guo Y, Samadashvili Z, Blecker S, Hannan EL. Revascularization in patients with multivessel coronary artery disease and severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction everolimus‐eluting stents versus coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Circulation. 2016;133:2132–2140. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.021168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagendran J, Bozso SJ, Norris CM, McAlister FA, Appoo JJ, Moon MC, Freed DH. Coronary artery bypass surgery improves outcomes in patients with diabetes and left ventricular dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:819–827. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.12.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun LY, Gaudino M, Chen RJ, Bader Eddeen A, Ruel M. Long‐term outcomes in patients with secerely reduced left ventricular ejection fraction undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention vs coronary artery bypass grafting. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:631–641. DOI: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee SE, Lee H‐Y, Cho H‐J, Choe W‐S, Kim H, Choi JO, Jeon E‐S, Kim M‐S, Hwang K‐K, Chae SC, et al. Coronary artery bypass graft versus percutaneous coronary intervention in acute heart failure. Heart. 2020;106:50–57. DOI: 10.1136/heartjnl-2018-313242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Head SJ, Milojevic M, Daemen J, Ahn J‐M, Boersma E, Christiansen EH, Domanski MJ, Farkouh ME, Flather M, Fuster V, et al. Mortality after coronary artery bypass grafting versus percutaneous coronary intervention with stenting for coronary artery disease: a pooled analysis of individual patient data. Lancet. 2018;391:939–948. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30423-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neumann F‐J, Sousa‐Uva M, Ahlsson A, Alfonso F, Banning AP, Benedetto U, Byrne RA, Collet J‐P, Falk V, Head SJ, et al. 2018 ESC/EACTS guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:87–165. DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fihn SD, Blankenship JC, Alexander KP, Bittl JA, Byrne JG, Fletcher BJ, Fonarow GC, Lange RA, Levine GN, Maddox TM, et al. 2014 ACC/AHA/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS focused update of the guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, and the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation. 2014;130:1749–1767. DOI: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh M, Rihal CS, Lennon RJ, Spertus JA, Nair KS, Roger VL. Influence of frailty and health status on outcomes in patients with coronary disease undergoing percutaneous revascularization. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4:496–502. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.961375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cutlip DE, Windecker S, Mehran R, Boam A, Cohen DJ, van Es G‐A, Gabriel Steg P, Morel MA, Mauri L, Vranckx P, et al. Clinical end points in coronary stent trials a case for standardized definitions. Circulation. 2007;115:2344–2351. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.685313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mehran R, Rao SV, Bhatt DL, Gibson CM, Caixeta A, Eikelboom J, Kaul S, Wiviott SD, Menon V, Nikolsky E, et al. Standardized bleeding definitions for cardiovascular clinical trials a consensus report from the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium. Circulation. 2011;123:2736–2747. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.009449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.