Abstract

Background:

Coronary microvascular dysfunction has been described in patients with autoimmune rheumatic disease (ARD). However, it is unknown whether positron emission tomography (PET)-derived myocardial flow reserve (MFR) can predict adverse events in this population.

Methods:

Patients with ARD without coronary artery disease who underwent dynamic rest-stress 82Rubidium PET were retrospectively studied and compared to patients without ARD matched for age, gender and comorbidities. The association between MFR and a composite endpoint of mortality or myocardial infarction (MI) or heart failure (HF) admission was evaluated with time to event and Cox-regression analyses.

Results:

In 101 patients with ARD (88% female, age: 62±10 years), when compared to matched patients without ARD (n=101), global MFR was significantly reduced (median:1.68 [interquartile range, IQR:1.34–2.05] vs. 1.86 [IQR:1.58–2.28]) and reduced MFR (<1.5) was more frequent (40% vs. 22%). MFR did not differ among subtypes of ARDs. In survival analysis, patients with ARD and low MFR (MFR<1.5) had decreased event-free survival for the combined endpoint, when compared to patients with and without ARD and normal MFR (MFR>1.5) and when compared to patients without ARD and low MFR, after adjustment for the non-laboratory-based Framingham risk score, rest left ventricular ejection fraction, severe coronary calcification, and the presence of medium/large perfusion defects. In Cox-regression analysis, ARD diagnosis and reduced MFR were both independent predictors of adverse events along with congestive HF diagnosis and presence of medium/large stress perfusion defects on PET. Further analysis with inclusion of an interaction term between ARD and impaired MFR revealed no significant interaction effects between ARD and impaired MFR.

Conclusions:

In our retrospective cohort analysis, patients with ARD had significantly reduced PET MFR compared to age-, gender- and comorbidity-matched patients without ARD. Reduced PET MFR and ARD diagnosis were both independent predictors of adverse outcomes.

Keywords: microvascular disease; myocardial flow reserve; myocardial blood flow; autoimmune rheumatic disease; positron emission tomography; outcomes; prognosis; rheumatoid arthritis; systemic sclerosis; scleroderma; systemic lupus erythematosus; Sjogren’s Syndrome; survival; microvascular blood flow; microcirculation; arthritis, rheumatoid; scleroderma, systemic; lupus erythematosus, systemic

Introduction

Autoimmune rheumatic diseases (ARD) represent a spectrum of diseases characterized by innate and adaptive immune responses directed against self-antigens. Many ARDs are independent predictors of cardiovascular disease (CVD). The lifetime risk for CVD is substantially higher in patients with ARD compared to the general population.1–3 It is well appreciated that inflammation plays a central role in the pathogenesis of CVD; therefore, systemic inflammation in ARD patients may largely underlie increased CVD risk. In addition, CVD risk may be exacerbated by ARD-associated cardiac involvement, side effects of anti-inflammatory medications, and the sedentary lifestyle commonly observed in ARD patients with arthritis and generalized pain syndromes.

Under normal conditions, coronary vascular resistance is primarily controlled by the microvasculature (pre-arterioles: diameter 100–500 μm and arterioles: diameter <100 μm).4 Coronary microvascular dysfunction (CMVD) refers to a pathological state whereby the abnormal microvasculature is unable to match myocardial blood flow to oxygen demand with resultant myocardial ischemia. Coronary microvascular dysfunction is most often characterized by an impaired microvascular vasodilator response to exercise or pharmacological stress. Historically, the diagnosis of CMVD required invasive coronary angiography linked with thermodilution or Doppler-based coronary flow assessments. However, for the last 30 years, noninvasive myocardial blood flow (MBF) and myocardial flow reserve (MFR) quantification has been possible with positron emission tomography (PET) imaging, which has now emerged as the noninvasive gold standard CMVD assessment.4

The prevalence of CMVD in patients with ARD is not well characterized. Small cohort studies report a high prevalence (29–44%) of CMVD in both asymptomatic ARD patients (n=76 patients)5 and in ARD patients with atypical/typical chest pain (n=20 patients).6 To date, only four studies have utilized PET to determine or assess MFR in patients with ARD.5, 7–9 Results from these studies suggest that ~30–50% of ARD patients demonstrate reduced MFR on PET; however, these studies are limited by the absence of matched control populations and longitudinal outcome data. The present study was undertaken in order to characterize the prevalence of CMVD in patients with ARD compared to patients without ARD matched for age, gender and cardiovascular co-morbidities. In addition, we aimed to investigate the prognostic value of PET MFR quantification in ARD patients.

Methods

Case Control Study

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Patients with ARDs who underwent dynamic rest and stress 82Rubidium (82-Rb) PET between 05/2012 and 05/2019 were included in a single center retrospective study at Yale New Haven Hospital (New Haven, CT). The institutional research ethics board approved the study with a waiver to obtain consent from the study subjects given the retrospective study design (HIC# 2000025019). Cases (patients with ARD) were identified by electronic health record search with subsequent manual chart review to confirm an ARD by a board-certified rheumatologist. In addition, a matched group of 101 patients without ARD, but with risk factors similar to the cases, were identified who had also undergone 82-Rb PET from 05/2017 – 11/2019. Electronic health records of matched patients without ARD were manually reviewed to adjudicate the absence of ARD diagnosis at the time of PET. Matching was performed for age, gender, body mass index (BMI), smoking history and clinical diagnosis of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, heart failure (HF), transient ischemic attack or stroke, peripheral artery disease, history of myocardial infarction (MI), coronary bypass surgery, percutaneous coronary intervention, chronic kidney disease and obstructive sleep apnea. Matching was performed by using a nearest neighbor matching method by using R environment Software (R version 3.4 and R Studio version 1.1.453, MatchIt package version 3.0.4). Non-laboratory-based Framingham risk score was calculated using the patient’s age, gender, resting systolic blood pressure, BMI and the presence of hypertension, smoking or diabetes, as previously reported.10

PET Imaging Protocol

Patients were asked to refrain from caffeine containing products for at least twelve hours prior to PET imaging, whereas regular outpatient medications were continued. Dynamic rest-stress 82-Rb PET myocardial perfusion imaging was performed on a hybrid PET 16-slice CT scanner (Discovery ST, GE Healthcare) or a hybrid PET 64-slice CT scanner (Discovery 690, GE Healthcare) as previously described.11 Briefly, dynamic rest PET images were acquired after intravenous (IV) injection of 82-Rb. After the rest PET scan, the ARD patients underwent pharmacological stress with regadenoson (n=91, bolus of 0.4 mg over 40 seconds), adenosine (n=7, continuous infusion at a rate of 140 μg/kg/min) or dobutamine (n=3, continuous infusion at a maximum rate of 40 μg/kg/min). Patients without ARDs also underwent stress using regadenoson (n=96), adenosine (n=3) or dobutamine (n=2) using similar administration protocols. At peak stress, 82-Rb was administered via peripheral IV and dynamic PET images were acquired. A low dose CT scan was acquired to permit attenuation correction of PET images.

PET Data Analysis

PET images were reconstructed with attenuation correction on system software creating a dynamic series of PET images that were reoriented and processed using Invia Corridor 4DM v2017 (Ann Arbor, MI). Regional and global rest and peak stress MBF were calculated by fitting the 82-Rb time-activity curves to a one-compartment tracer kinetic model as described previously.11 Rest and stress flows were corrected for the rate pressure product (heart rate x systolic blood pressure) as described previously.11 Myocardial flow reserve was calculated as the ratio of stress to rest MBF. Hyperemic coronary vascular resistance was calculated by dividing stress mean arterial pressure by stress MBF. On the study imaging day, one of six expert readers reviewed attenuation CT scans to assess for the presence of coronary calcification.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the combined end point of all-cause mortality or HF admission or MI admission. Information was collected by chart review which included outpatient visits, inpatient encounters and telephone calls for up to four years. Severely reduced MFR was defined as <1.5 based on previously published data.11

Statistical Analyses

Differences between categorical variables were assessed using Fisher’s exact (dichotomous variables) and Chi-square tests (trichotomous variables), respectively. Continuous variables were compared using a 2-tailed T-test for normally distributed data. Non-normally distributed continuous variables were compared with Mann-Whitney test. Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare the difference among more than two groups for non-normally distributed variables. In box and whiskers graphs, the boxes represent the 25th to 75th percentiles, the midlines represent the median values and the whiskers indicate minimal and maximal values. Pearson correlation (BMI, age and time since ARD diagnosis) or Spearman correlation coefficient (erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR], C-reactive protein [CRP]) with 95% confidence interval (CI) were used to evaluate the correlation between dependent variables of interest with MFR. CRP and ESR values obtained within 1 year of PET were considered.

Standard survival analysis strategies were used to determine event-free survival for the combined end point of all-cause mortality or HF admission or MI admission. Unadjusted survival analysis was conducted using the Kaplan-Meier method, and statistical comparisons were assessed using the log-rank test. Adjusted survival analysis was done by using Cox proportional hazards survival analysis controlling for non-laboratory-based Framingham risk score, previously diagnosed congestive HF, rest left ventricular ejection fraction, presence of severe coronary calcification and medium/large perfusion defects. Adjusted and unadjusted survival curves were generated for patients categorized according to established MFR cutoffs.11

To assess the impact of MFR on cardiovascular outcomes, the Cox proportional hazards model was used in the whole patient cohort including ARD patients and matched patients without ARD after controlling for the non-laboratory-based Framingham risk score, presence of medium or large perfusion defects, ejection fraction at rest, heart failure history and severe coronary calcifications. Cox regression modeling with forward selection was performed to determine independent predictors of the combined endpoint. In further analyses, we explored potential interaction effects between the presence of ARD and impaired MFR (cut-off of 1.5) by also including an interaction term between the two variables in our Cox regression models.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 27.0.0.0, Microsoft Inc, College Station, TX), and statistical significance was defined as p <0.05 for all analyses unless otherwise noted.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 101 ARD patients underwent rest and stress 82-Rb PET between 05/2012 and 05/2019. The baseline patient characteristics are reported in Table 1. The most common ARD diagnosis was rheumatoid arthritis (RA, n=45, 45%) followed by systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE, n=26, 26%), systemic sclerosis (SSc, n=15, 15%), Sjogren’s syndrome (n=15, 15%), seronegative inflammatory arthritis (n=10, 10%), polymyositis/dermatomyositis (n=3, 3%) and mixed connective tissue disease (n=1, 1%), 15 patients had more than one ARD diagnosis. Both patients with and without ARD commonly used beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (Table 1). Hemodynamics and stress test characteristics are reported in Table 2. Briefly, ARD patients had lower systolic pressure and higher heart rate at rest when compared to patients without ARD, however the rate pressure product was not significantly different between groups (p=0.53). Patients with ARD had higher baseline and stress left ventricular ejection fraction compared to patients without ARD. The rates of coronary artery calcifications, severe coronary calcifications and perfusion defects (mostly small) were comparable between patients with and without ARD (Table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Baseline characteristics | Patients without ARD n=101 |

Patients with ARD n=101 |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 60 (52–70) | 63 (56–69) | 0.55 |

|

| |||

| Female sex, n (%) | 88 (87%) | 81 (80%) | 1.00 |

|

| |||

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 34 (26–45) | 38 (29–42) | 0.51 |

|

| |||

| Race, n (%) | 0.11 | ||

| Caucasian | 62 (61%) | 73 (72%) | |

| African-American | 30 (30%) | 25 (25%) | |

| Other/unknown | 9 (9%) | 3 (3%) | |

|

| |||

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||

| Congestive heart failure | 8 (8%) | 9 (9%) | 1.00 |

| Hypertension | 71 (70%) | 76 (75%) | 0.53 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 48 (48%) | 52 (51%) | 0.67 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 33 (33%) | 30 (30%) | 0.76 |

| Smoking | 15 (15%) | 16 (16%) | 1.00 |

| Transient ischemic attack/Stroke | 14 (14%) | 14 (14%) | 1.00 |

|

| |||

| Medications, n (%) | |||

| Beta blockers | 48 (48%) | 41 (41%) | 0.40 |

| Calcium channel blocker | 38 (38%) | 30 (30%) | 0.30 |

| Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor | 26 (26%) | 21 (21%) | 0.51 |

| ARB | 21 (21%) | 32 (32%) | 0.11 |

| Diuretic | 28 (28%) | 29 (29%) | 1.00 |

| Nitrate | 1 (1%) | 2 (2%) | 1.00 |

| Aspirin | 49 (49%) | 39 (39%) | 0.20 |

| Statin | 53 (52%) | 43 (43%) | 0.20 |

Continuous variables are expressed as medians (interquartile ranges), categorical variables are expressed as absolute frequencies (percentages). Abbreviations: ARB: Angiotensin receptor blocker, ARD: autoimmune rheumatic disease

Table 2.

Imaging Characteristics

| Imaging characteristics | Patients without ARD n=101 |

Patients with ARD n=101 |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study Indication, n (%) | |||

| Chest Pain | 66 (65%) | 64 (63%) | 0.88 |

| Dyspnea | 25 (25%) | 35 (35%) | 0.17 |

| Palpitations | 6 (6%) | 3 (3%) | 0.50 |

| Other | 21 (21%) | 17 (17%) | 0.59 |

|

| |||

| Hemodynamics | |||

| Rest SBP (mmHg) | 142 (130–157) | 132 (118–144) | <0.001 |

| Rest HR (bpm) | 71 (65–77) | 76 (70–83) | 0.004 |

| Rest RPP (mmHg x bpm x 1,000) | 10.00 (8.89–11.67) | 9.65 (8.79–11.43) | 0.53 |

| Stress SBP (mmHg) | 129 (111–142) | 127 (115–144) | 0.66 |

| Stress HR (bpm) | 100 (91–108) | 96 (88–111) | 0.74 |

| Stress RPP (mmHg x bpm x 1,000) | 12.50 (10.61–14.66) | 12.18 (10.54–14.81) | 0.90 |

|

| |||

| Stressor agent, n (%) | 0.38 | ||

| Regadenoson | 96 (95%) | 91 (90%) | |

| Adenosine | 3 (3%) | 7 (7%) | |

| Dobutamine | 2 (2%) | 3 (3%) | |

|

| |||

| Study results | |||

| Stress perfusion defect, n (%) | 23 (23%) | 19 (19%) | 0.60 |

| Medium/large stress perfusion defect, n (%) | 13 (13%) | 8 (8%) | 0.36 |

| Rest perfusion defect, n (%) | 12 (12%) | 12 (12%) | 1.00 |

| Medium/large rest perfusion defect, n (%) | 7 (7%) | 4 (4%) | 0.54 |

| Coronary calcification, n (%) | 39 (39%) | 51 (50%) | 0.12 |

| Severe coronary calcification, n (%) | 14 (14%) | 13 (13%) | 1.00 |

| Rest LVEF (%) | 58 (52–65) | 64 (57–72) | <0.001 |

| Stress LVEF (%) | 65 (57–69) | 69 (63–75) | <0.001 |

| Left heart catheterization results | |||

| Left heart catheterization, n (%) | 14 (14%) | 10 (10%) | 0.51 |

| Obstructive coronary artery disease, n (%) | 8 (8%) | 4 (4%) | 0.37 |

| Coronary revascularization, n (%) | 5 (5%) | 2 (2%) | 0.44 |

Continuous variables are expressed as medians (interquartile ranges), categorical variables are expressed as absolute frequencies (percentages). Abbreviations: ARD: autoimmune rheumatic disease, SBP: systolic blood pressure, HR: heart rate, RPP: rate pressure product, LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction, PET: positron emission tomography

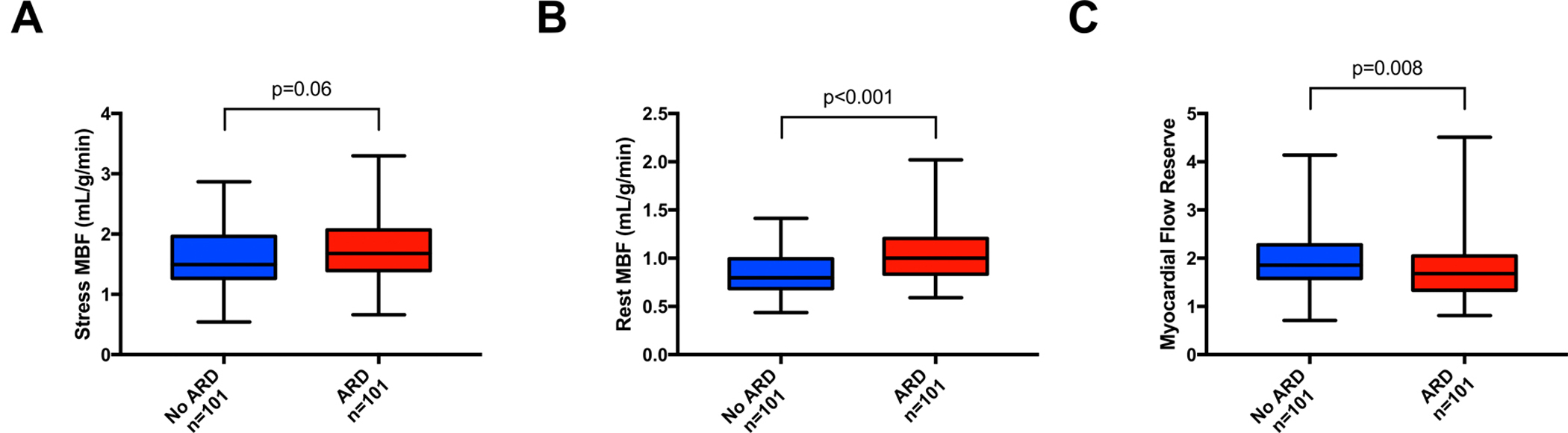

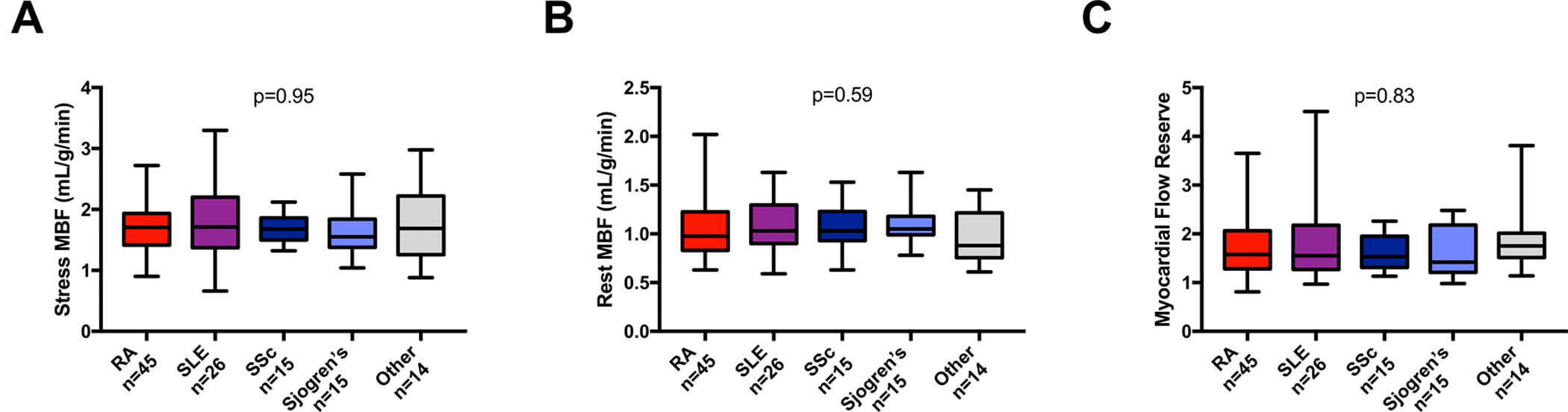

Stress MBF did not significantly differ between patients with ARD (median with interquartile range [IQR], 1.68 [IQR: 1.39 – 2.07]) compared to those without ARD (1.49 [IQR: 1.26 – 1.93]; p=0.06). Conversely, rest MBF was significantly higher in ARD patients (1.00 [IQR: 0.84 – 1.21]) compared to those without an ARD diagnosis (0.80 [IQR: 0.68 – 0.99]; p<0.001). Consequently, MFR was significantly reduced in ARD patients compared to patients without ARD (1.68 [IQR: 1.34 – 2.05] vs. 1.86 [IQR: 1.58 – 2.28]; p=0.008) (Figure 1, Supplemental Table I). Significantly more patients with ARD had severely reduced MFR (n=40, 40%) when compared to patients without ARD (n=22, 22%, p=0.009). There were no differences in rest and stress MBF and MFR among patients with different ARD conditions (Figure 2). In ARD patients, there were no differences in regional MFR for different coronary territories (left anterior descending artery: 1.57 [IQR: 1.27 – 2.02], left circumflex artery: 1.58 [IQR: 1.27 – 2.00], right coronary artery: 1.69 [IQR: 1.37 – 2.18]; p=0.20).

Figure 1. Myocardial blood flow in patients with or without autoimmune rheumatic disease.

A) Stress myocardial blood flow (MBF); B) Rest MBF; C) Myocardial flow reserve. ARD: autoimmune rheumatic disease.

Figure 2. Myocardial blood flow based on patients underlying autoimmune rheumatic disease conditions.

A) Stress myocardial blood flow (MBF); B) Rest MBF; C) Myocardial flow reserve. RA: rheumatoid arthritis, SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus, SSc: systemic sclerosis

In ARD patients, there was a weak but significant correlation between MFR and higher BMI (r=0.21, 95% CI: 0.01 to 0.39, p=0.037) and between MFR and the age at the time of PET (r=−0.27, 95% CI: −0.44 to −0.08, p=0.006), whereas no significant correlation was observed between MFR values and the time interval between PET and time of ARD diagnosis (r=−0.10, 95% CI: −0.29 to 0.10, p=0.32). There was a weak correlation between ESR and MFR (available in n=84 patients, r=−0.24, 95% CI: −0.43 to −0.02, p = 0.03) but no significant correlation was found between CRP and MFR (available in n=75 patients, r =−0.17, 95% CI: −0.38 to 0.05, p = 0.13).

Perfusion defects were present in 19 ARD patients (19%, perfusion defect size: n=11 small, n=6 medium and n=2 large) and in 22 patients without ARD (22%, perfusion defect size: n=9 small, n=7 medium and n=6 large). In the ten ARD patients undergoing left heart catheterization within 1 year or PET, six patients had no detectable coronary artery disease (CAD), whereas four patients had evidence of obstructive CAD (two of these patients underwent coronary revascularization, Table 2). Left heart catheterization was performed in fourteen patients without ARD, of whom eight patients were found to have obstructive CAD including five patients who underwent subsequent revascularization. The frequency of obstructive CAD (p=0.37) and the rate of revascularization (p=0.44) were not statistically different between ARD and non-ARD patients. Global MFR was significantly reduced and rest MBF was significantly increased in ARD patients when compared to matched non-ARD patients, even after excluding patients who were subsequently diagnosed with obstructive CAD (Supplemental Figure I). Out of the 21 patients with medium to large perfusion defects (13 patients without and eight patients with ARD), eight patients were found to have obstructive CAD (five patients without and three patients with ARD), five patients had no obstructive CAD (four patients without and one patient with ARD) and nine patients did not undergo left heart catheterization (four patients without and five patients with ARD) (Supplemental Table II). All patients without left heart catheterization have been evaluated by a board-certified cardiologist (either inpatient or outpatient), and based on the available data it was decided that the low likelihood of obstructive CAD requiring intervention did not warrant invasive assessment. Out of these nine patients, five patients had no coronary calcifications on attenuation CT and/or were asymptomatic and/or image review was more consistent with small size perfusion defect. Two patients had no significant changes in the imaging findings, when compared to prior myocardial perfusion imaging. The remaining two patients had fixed defects in a non-coronary distribution thought to be related to an old myocardial process.

Patient outcomes

During a median follow-up time of 3.8 years in the ARD group, twelve deaths occurred, four patients suffered an MI, and 18 patients had a HF admission (ten patients admitted with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and eight patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction) (Supplemental Table III). The cause of death was attributed to CVD in ten out of the twelve ARD patients. During a median follow-up time of 2.5 years in the matched group without ARD, three deaths occurred, two patients suffered an MI and nine patients had a HF hospitalization.

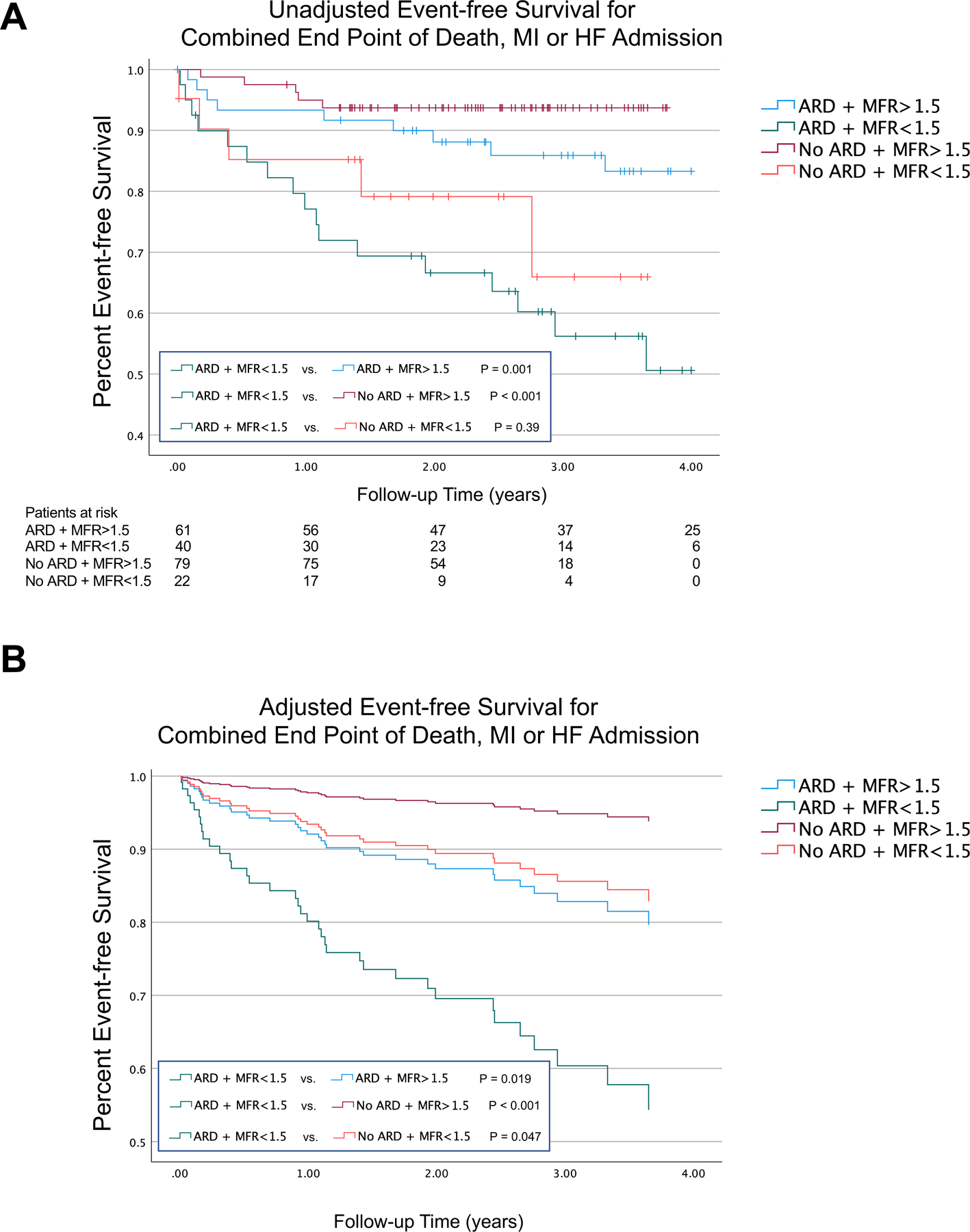

On unadjusted Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, patients with ARD and MFR of <1.5 had worse event free survival for the combined end-point when compared to patients with ARD and MFR >1.5 (p=0.001). Similarly, these patients also had worse event free survival when compared to patients without ARD and MFR >1.5 (p<0.001) (Figure 3A). These correlations remained significant after adjustment for non-laboratory-based Framingham risk score, rest left ventricular ejection fraction, severe coronary calcification on attenuation CT and the presence of medium/large perfusion defects (Figure 3B). There was also a significant difference in event-free survival in patients with or without ARD and MFR <1.5 (p=0.047). Adjusted survival analyses yielded similar results after excluding patients who were subsequently diagnosed with obstructive CAD (Supplemental Figure IIA) or after excluding patients with dobutamine stress (Supplemental Fig IIIA).

Figure 3. Event-free survival based on autoimmune rheumatic disease diagnosis and myocardial flow reserve.

A) Unadjusted event-free survival for the combined end point of death, myocardial infarction (MI) or heart failure (HF) admission; B) Adjusted event-free survival for the combined end point of death, MI or HF admission.

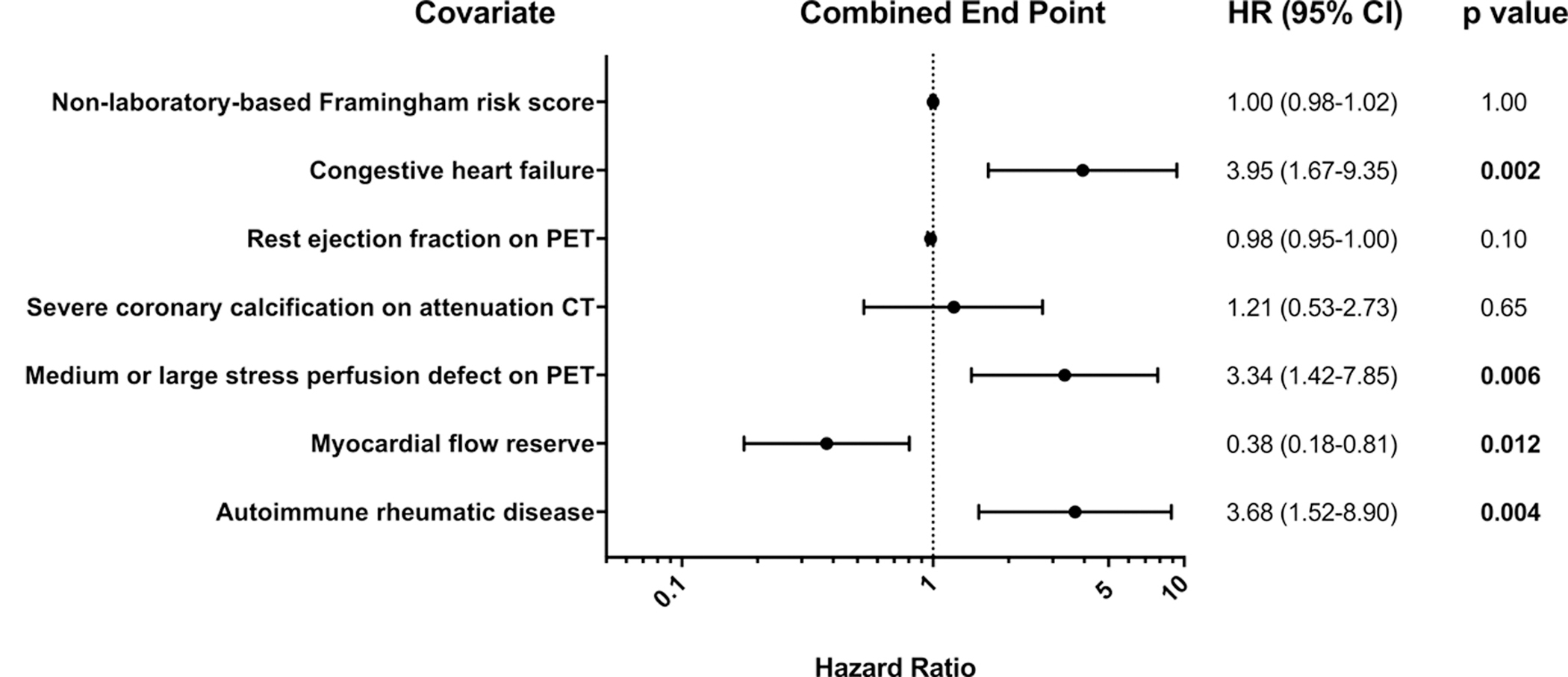

Independent predictors of adverse events

In Cox proportional hazards regression models, a congestive HF diagnosis, medium/large stress perfusion defects on 82-Rb PET, rate pressure product corrected MFR and ARD diagnosis were found to be independent predictors of adverse events (Figure 4). Of note, further analysis with inclusion of an interaction term between ARD and impaired MFR revealed no significant interaction effects between ARD and impaired MFR (P=0.94). Rate pressure product corrected MFR and ARD diagnosis remained independent predictors of adverse events even when excluding patients who were subsequently diagnosed with obstructive CAD (Supplemental Figure IIB) or after excluding patients with dobutamine stress (Supplemental Fig IIIB).

Figure 4. Forest plot of hazard ratios for the combined end point of death, myocardial infarction or heart failure admission in multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models.

HR: hazard ratio, RPP: rate pressure product, MFR: myocardial flow reserve, BMI: body mass index, CT: computed tomography, PET: positron emission tomography

Discussion

In the current study, we provide evidence that MFR is significantly lower in ARD patients when compared to patients without ARD that were appropriately matched for age, gender and comorbidities. In addition, we show that patients with an ARD diagnosis with MFR<1.5 have worse event-free survival for the combined end point of death, MI or HF admission, when compared to patients without an ARD diagnosis with MFR<1.5 and also when compared to ARD patients with MFR>1.5. Furthermore, we demonstrate that both ARD diagnosis and decreased MFR as assessed by dynamic 82-Rb PET independently predict adverse events in this patient sample.

Prior studies – PET myocardial blood flow in ARD patients

To our knowledge our study is the first to report on the predictive value of dynamic rest-stress 82-Rb PET myocardial perfusion imaging in a relatively large number of patients with ARDs. Autoimmune rheumatic disease versus non-ARD patients had significantly higher resting MBF, but stress MBF was not significantly different, thus yielding a lower stress/rest MBF ratio (MFR). Our observation is consistent with findings from prior studies that showed that an increased rest MBF or a trend towards increased rest MBF can contribute substantially to reduced MFR in conditions associated with CMVD other than ARDs.11, 12 A potential explanation for the increased rest MBF in ARD patients is autonomic dysfunction. Impaired parasympathetic activity, increased sympathetic activity and increased catecholamine levels have been reported frequently in autoimmune conditions.13–15 The increased sympathetic activation may lead to increase in MBF due to the increased cardiac metabolism resulting from the tachycardia and augmented contraction.4 This theory is supported by the observed higher resting heart rate in our ARD patients when compared to matched controls. Another potential explanation is that the ARD patients had subclinical HF at the time of PET potentially leading to increased heart rate and subsequent increase in rest MBF. In line with this, ARDs have been associated with increased incidence of HF when compared to controls16 and abnormal diastolic function has been strongly associated with adverse prognosis in patients with ARD.17 The lower resting MBF in the matched group without ARD could represent a higher frequency of patients with MIs, however the percentage of patients with any rest perfusion defects or medium/large rest perfusion defects was not significantly different between patients with or without ARD. It is also possible that elevated resting MBF observed in CMVD patients may also be related to structural changes in the coronary microvascular wall prohibiting proper oxygen transport from the blood to the myocardium or an impairment in cardiac myocytes to extract oxygen effectively.14 In either instance, an increase in resting MBF may represent a compensatory mechanism to maintain adequate oxygen delivery to the myocardium. Indeed, this hypothesis will need to be tested in future studies by correlating biopsy results with MBF estimations. Notably, results of a recent large study of 1,283 patients evaluated by PET at a tertiary center suggested that elevated resting MBF carries prognostic implications similar to reduced stress MBF or MFR in patients undergoing PET myocardial perfusion imaging.12 Interestingly, in our cohort a trend towards elevated stress MBF and elevated hyperemic vascular resistance was also noted in the ARD patients versus controls. This observation would warrant further investigation to examine whether the difference reaches statistical significance in larger patient samples and to uncover the potential mechanisms.

Previously four groups have reported the results of PET MBF imaging in patients with ARD. These studies primarily focused on RA patients and were limited by small samples, the lack of an appropriately matched control cohort and/or the absence of outcomes assessments.5, 7–9 In line with our findings, Recio-Mayoral et al. reported that PET MFR was reduced in 25 patients with SLE or RA when compared to 25 age- and gender-matched controls.7 This study demonstrated a weak inverse correlation between global MFR and ARD duration, whereas we observed no such correlation. A potential explanation for this discrepancy may lie in differences in medication regimens, co-morbidity profiles or the timing of PET assessment. In our study, despite the observed association between ESR and MFR, unlike in prior studies,7, 9 we found no correlation between MFR and CRP. This might be related to the relatively wide temporal window between PET and inflammatory marker sampling, therefore temporal changes in CRP levels related to disease activity and/or changes in anti-inflammatory therapies cannot be excluded. However, in agreement with our findings, the aforementioned studies have documented a high prevalence (29 – 54%) of CMVD in patients with RA undergoing PET MFR measurements.5, 8 Specifically, Amigues et al. documented the presence of reduced MFR (MFR <2.5) in 29% of 76 asymptomatic RA patients undergoing myocardial perfusion imaging with an 13N-ammonia PET study protocol.5 In retrospective analysis of 73 RA patients undergoing MBF assessment by 13N-ammonia PET for clinical indications, Liao et al. reported a high prevalence (54%) of reduced PET MFR (<2.0).8

The predictive value of PET MFR has been described in multiple CMVD associated conditions and has been reviewed extensively elsewhere.4 As a result of these recent invaluable observations, CMVD is now considered a bonafide risk factor for adverse cardiovascular outcomes. With relevance to our study, Liao et al. recently demonstrated that CMVD diagnosed by reduced 13N-ammonia PET MFR was an independent predictor of adverse cardiovascular events in patients with RA.8 In this study, the cardiovascular event rates for patients with RA were comparable to those observed in patients with diabetes mellitus. Weber et al. demonstrated that impaired PET MFR (MFR<1.65) was associated with worse cardiovascular outcomes and all-cause mortality in a patient sample including 198 patients with systemic inflammatory conditions including SLE, RA and psoriasis.9 Our findings extend these observations by showing an increased risk of adverse events in ARD patients when compared to a matched cohort without ARD but with similar co-morbidity and medication profiles. Our results indicate that ARD diagnosis is not only associated with reduced MFR, but also predicts adverse outcomes independently of MFR. We found no interaction between ARD and low MFR This suggests that ARD and low MFR may adversely affect outcomes independently with limitations that our study was not powered to evaluate for an interaction. Additional properly powered studies will be needed to answer this question.

Assessing microvascular dysfunction with other imaging modalities in patients with ARD

Non-nuclear imaging modalities such as echocardiographic and cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) approaches have been used to assess cardiac function in patients with ARDs, but these approaches are not routinely used for absolute MBF quantification and are less extensively validated for CMVD evaluation than radionuclide approaches. Reduced transthoracic echocardiography Doppler coronary flow velocity reserve (CFVR) has been demonstrated in small studies that included multiple ARD conditions, such as RA18 and SSc.19 Importantly, these studies did not report on the prognostic value of the reduced CFVR.

A limited number of studies have demonstrated reduced myocardial perfusion by CMR in patients with ARD.6, 20, 21 Reduced myocardial perfusion reserve index (a quantitative index of myocardial perfusion derived from first pass gadolinium time-intensity curves without quantification of absolute myocardial blood flow) has been described in patients with SLE6 and SSc.20 Gyllenhammar et al. used coronary sinus blood flow measurements by CMR for the evaluation of MBF in response to adenosine in 17 SSc patients and compared them to healthy volunteers and found reduced adenosine-induced myocardial blood flow in patients with SSc.21 Given the small sample size and/or lack of follow-up, the prognostic value of CMR flow assessment in ARD patients remains unclear.

Echocardiographic and CMR techniques represent promising new CMVD assessment strategies that lack ionizing radiation, however each carries some inherent limitations. The technique of Doppler CFVR assessment is operator dependent and can be affected by respiratory motion as well as obesity and parenchymal lung diseases that are common in ARD patients. The evaluation of CMR images can be confounded by imaging artifacts, and gadolinium-based contrast agents are contraindicated in patients with advanced renal disease which may be prevalent in the ARD patient population. Moreover, gadolinium-based CMR approaches are limited by a nonlinear relationship of contrast enhancement and contrast concentration, and also by the relatively complicated post acquisition processing and the relatively higher cost of this imaging modality.4

Study limitations

Despite the fact that this study is one of the largest studies reporting PET MFR results in ARD patients to date, this study was a single center, nonrandomized, retrospective observational study, which carries all the inherent limitations of such a study design. As we have grouped multiple ARD conditions together, despite their common inflammatory background, our ARD patient cohort may be more heterogenous with respect to inflammation burden. In addition, in relation to the study design, we cannot exclude the presence of confounders, despite carefully controlling for numerous co-variables reported to be associated with cardiovascular risk. Because only a subset of our patient sample had undergone invasive epicardial coronary assessment, it is also possible that our results can be confounded by undiagnosed obstructive epicardial disease. However, medium and large sized perfusion defects and severe calcifications were relatively infrequent in our ARD sample, and sensitivity analysis demonstrated that MFR and ARD remained significant predictors of outcomes even after excluding patients with CAD on subsequent cardiac catheterization.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that PET MFR is significantly lower in ARD patients when compared to age-, gender- and comorbidity-matched patients without ARD. We also observe that patients with an ARD diagnosis with MFR<1.5 have worse event-free survival for the combined end point of death, MI or HF admission, when compared to patients without an ARD diagnosis with MFR<1.5 and also when compared to ARD patients with MFR>1.5. Furthermore, we demonstrate that both ARD diagnosis and MFR as assessed by dynamic 82-Rb PET independently predicted adverse events in this patient sample. We have found no interaction between ARD and low MFR, however, our study was not powered to evaluate for an interaction and additional properly powered studies will be needed to answer this question.

Supplementary Material

Clinical perspective.

Patients with autoimmune rheumatic disease (ARD) demonstrate increased cardiovascular risk related to increased systemic inflammation. Coronary microvascular dysfunction has been described in patients with ARD. However, to date, no large studies have evaluated PET-derived myocardial flow reserve (MFR) in ARD patients and it is unknown whether MFR can predict adverse events in this population. In our retrospective study we have evaluated patients with ARD without coronary artery disease who underwent dynamic rest-stress 82Rubidium PET for a clinical indication and compared them to patients without ARD matched for age, gender and comorbidities. We have found that in ARD patients, when compared to matched patients without ARD, global MFR was significantly reduced and reduced MFR (<1.5) was more frequent (40% vs. 22%). In survival analysis, patients with ARD and low MFR had decreased event-free survival for the combined endpoint of mortality or myocardial infarction or heart failure admission, when compared to patients with and without ARD and normal MFR and when compared to patients without ARD and low MFR, after adjustment for age, gender and co-morbidities. In Cox-regression analysis, ARD diagnosis and reduced MFR were both independent predictors of adverse events along with congestive heart failure diagnosis and presence of medium/large stress perfusion defects on PET. Our results suggest that 1) ARD patients may have reduced MFR compared to patients without ARD potentially related coronary microvascular disease 2) myocardial blood flow quantification with 82Rubidium PET may be used for prognostication in patients with ARD.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This study was supported by a National Institutes of Health T32 training grant (HL098069 to Dr. Sinusas) and by a National Institutes of Health / National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases R01 grant (AR073270 to Dr. Hinchcliff).

Abbreviations

- ARD

autoimmune rheumatic disease

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- CMVD

coronary microvascular dysfunction

- MBF

myocardial blood flow

- MFR

myocardial flow reserve

- PET

positron emission tomography

- BMI

body mass index

- HF

heart failure

- 82-Rb

82Rubidium

- IV

intravenous

- ESR

erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- CI

confidence interval

- RA

rheumatoid arthritis

- SLE

systemic lupus erythematosus

- SSc

systemic sclerosis

- IQR

interquartile range

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- CMR

cardiac magnetic resonance

- CFVR

coronary flow velocity reserve

- MI

myocardial infarction

- RPP

rate pressure product

- CT

computed tomography

- SBP

systolic blood pressure

- HR

heart rate

- LVEF

left ventricular ejection fraction

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

None.

References

- 1.Wallberg-Jonsson S, Ohman ML and Dahlqvist SR. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in patients with seropositive rheumatoid arthritis in Northern Sweden. J Rheumatol 1997;24:445–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manzi S, Meilahn EN, Rairie JE, Conte CG, Medsger TA Jr., Jansen-McWilliams L, D’Agostino RB and Kuller LH. Age-specific incidence rates of myocardial infarction and angina in women with systemic lupus erythematosus: comparison with the Framingham Study. Am J Epidemiol 1997;145:408–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cai X, Luo J, Wei T, Qin W, Wang X and Li X. Risk of Cardiovascular Involvement in Patients with Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome: a large-scale cross-sectional cohort study. Acta reumatologica portuguesa 2019;44:71–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feher A and Sinusas AJ. Quantitative Assessment of Coronary Microvascular Function: Dynamic Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography, Positron Emission Tomography, Ultrasound, Computed Tomography, and Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2017;10:e006427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amigues I, Russo C, Giles JT, Tugcu A, Weinberg R, Bokhari S and Bathon JM. Myocardial Microvascular Dysfunction in Rheumatoid ArthritisQuantitation by (13)N-Ammonia Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2019;12:e007495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishimori ML, Martin R, Berman DS, Goykhman P, Shaw LJ, Shufelt C, Slomka PJ, Thomson LE, Schapira J, Yang Y, et al. Myocardial ischemia in the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease in systemic lupus erythematosus. JACC Cardiovasc imaging 2011;4:27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Recio-Mayoral A, Mason JC, Kaski JC, Rubens MB, Harari OA and Camici PG. Chronic inflammation and coronary microvascular dysfunction in patients without risk factors for coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J 2009;30:1837–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liao KP, Huang J, He Z, Cremone G, Lam E, Hainer JM, Morgan V, Bibbo C and Di Carli M. Coronary microvascular dysfunction in rheumatoid arthritis compared to diabetes mellitus and association with all-cause mortality. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2021;73:159–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weber BN, Stevens E, Perez-Chada LM, Brown JM, Divakaran S, Bay C, Bibbo C, Hainer J, Dorbala S, Blankstein R, et al. Impaired Coronary Vasodilator Reserve and Adverse Prognosis in Patients With Systemic Inflammatory Disorders. JACC Cardiovasc imaging 2021; 10.1016/j.jcmg.2020.12.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.D’Agostino RB Sr., Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, Wolf PA, Cobain M, Massaro JM and Kannel WB. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2008;117:743–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feher A, Srivastava A, Quail MA, Boutagy NE, Khanna P, Wilson L, Miller EJ, Liu YH, Lee F and Sinusas AJ. Serial Assessment of Coronary Flow Reserve by Rubidium-82 Positron Emission Tomography Predicts Mortality in Heart Transplant Recipients. JACC Cardiovasc imaging 2020;13:109–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guerraty MA, Rao HS, Anjan VY, Szapary H, Mankoff DA, Pryma DA, Rader DJ and Dubroff JG. The role of resting myocardial blood flow and myocardial blood flow reserve as a predictor of major adverse cardiovascular outcomes. PloS one 2020;15:e0228931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dessein PH, Joffe BI, Metz RM, Millar DL, Lawson M and Stanwix AE. Autonomic dysfunction in systemic sclerosis: sympathetic overactivity and instability. Am J Med 1992;93:143–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh I, Oliveira RKF, Naeije R, Oldham WM, Faria-Urbina M, Waxman AB and Systrom DM. Systemic vascular distensibility relates to exercise capacity in connective tissue disease. Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 2020;60:1429–1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shalimar, Handa R, Deepak KK, Bhatia M, Aggarwal P and Pandey RM. Autonomic dysfunction in systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatol Int 2006;26:837–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim CH, Al-Kindi SG, Jandali B, Askari AD, Zacharias M and Oliveira GH. Incidence and risk of heart failure in systemic lupus erythematosus. Heart 2017;103:227–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hinchcliff M, Desai CS, Varga J and Shah SJ. Prevalence, prognosis, and factors associated with left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2012;30:S30–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ciftci O, Yilmaz S, Topcu S, Caliskan M, Gullu H, Erdogan D, Pamuk BO, Yildirir A and Muderrisoglu H. Impaired coronary microvascular function and increased intima-media thickness in rheumatoid arthritis. Atherosclerosis 2008;198:332–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sulli A, Ghio M, Bezante GP, Deferrari L, Craviotto C, Sebastiani V, Setti M, Barsotti A, Cutolo M and Indiveri F. Blunted coronary flow reserve in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 2004;43:505–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mavrogeni SI, Bratis K, Karabela G, Spiliotis G, Wijk K, Hautemann D, Reiber JH, Koutsogeorgopoulou L, Markousis-Mavrogenis G, Kolovou G, et al. Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Imaging clarifies cardiac pathophysiology in early, asymptomatic diffuse systemic sclerosis. Inflammation & allergy drug targets 2015;14:29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gyllenhammar T, Kanski M, Engblom H, Wuttge DM, Carlsson M, Hesselstrand R and Arheden H. Decreased global myocardial perfusion at adenosine stress as a potential new biomarker for microvascular disease in systemic sclerosis: a magnetic resonance study. BMC cardiovasc disord 2018;18:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.