Abstract

Childhood obesity is a significant public health concern associated with the development of the leading causes of death. Dietary factors largely contribute to childhood obesity, but prevention interventions targeting these factors have reported relatively small effect sizes. One potential explanation for the ineffectiveness of prevention efforts is lack of theoretical grounding. Behavioral economic (BE) theory describes how people choose to allocate their resources and posits that some children place higher value on palatable foods (relative reinforcing value of food) and have difficulty delaying food rewards (delay discounting). These seemingly individual-level decision making processes are influenced by higher-level variables (e.g., environment/policy) as described by the social ecological model. The purpose of this manuscript is to provide a theoretical review of policy-level childhood obesity prevention nutrition initiatives informed by BE. We reviewed two policy-level approaches: (1) incentives-/price manipulation-based policies (e.g., sugary drink tax, SNAP pilot) and (2) healthful choices as defaults (Healthy Hunger Free Kids Act/National School Lunch Program, advertising regulations, default items). We review current literature as well as its limitations and future directions. Exploration of BE theory applications for nutrition policies may help to inform future theoretically grounded policy-level public health interventions.

Keywords: childhood obesity, behavioral economics, social ecological model, nutrition policy, prevention, health policy

Introduction

Childhood obesity is a significant public health concern, placing individuals at risk for the development of heart disease, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and many cancers (Sahoo et al., 2015). This is significant because each year, heart disease accounts for 635,260 deaths, cancer accounts for 598,038 deaths, and diabetes accounts for 80,058 deaths (National Center for Health Statistics, 2018). In addition, the prevalence of childhood obesity in the U.S. increases as children age: 13.9% of 2- to 5-year-olds, 18.4% of 6- to 11-year-olds, and 20.6% of 12- to 19-year-olds currently have obesity (National Center for Health Statistics, 2017).

Although the causes of obesity are complex and multidimensional, the most proximal cause of obesity is persistent energy intake that exceeds energy expenditure (Martinez, 2000; Spiegelman & Flier, 2001). Therefore, dietary behaviors are an important factor to consider in weight gain prevention. Children and adolescents are far from meeting requirements within the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (Banfield et al., 2016). In a large epidemiological study, child dietary quality measured by the Healthy Eating Index (HEI-10) ranged from 43.59 to 52.11 out of 100 with a score of 80 indicating a diet associated with “good health” (Banfield et al., 2016). Dietary habits that are established in childhood tend to persist into adulthood (Lake et al., 2006; Mikkilä et al., 2005), making childhood an important developmental period for early intervention.

Although there are several evidence-based childhood obesity prevention interventions targeting dietary behaviors, the effect sizes of these interventions are relatively small. For example, a recent meta-analysis of childhood obesity interventions involving parents found a small combined effect size after a short-term (within 3 months post-intervention) follow-up (d = .08), and an even smaller combined effect size after a long-term (3 months or more) follow-up (d = .02) (Yavuz et al., 2015). In particular, long-term follow up studies on interventions focusing on eating habits, or dietary behavior, produced the lowest effect size (d = .04; Yavuz et al., 2015).

In a scoping review, Davis et al. (2015) suggest that one potential explanation for the modest effect sizes in health behavior change research may be that health behavior interventions are not always informed by theory. Behavior change theories can help to explain predictors of behavior change as well as predictors of intervention effectiveness (Davis et al., 2015). Another potential limitation to existing obesity prevention interventions is that they focus primarily on individual-level behavior change and largely ignore the greater environmental and policy context (Davis et al., 2015). Applying scientifically supported theories and extending this application to higher systems levels beyond the individual may increase the impact of obesity prevention interventions.

Behavioral Economic Theory Applications to Obesity

Behavioral economic (BE) theory has been applied to health behavior research, including childhood obesity (Epstein & Saelens, 2000; Stojek & MacKillop, 2017). BE describes how people choose to allocate their resources (e.g., time, money, behavior; Hursh, 2000; Madden, 2000) within a system of constraints. Researchers have developed the reinforcer pathology model (Bickel et al., 2011; Carr et al., 2011) to describe the interaction between two key BE constructs: the relative reinforcing value of Food (RRVfood) and delay discounting (DD; Epstein et al., 2010). The reinforcer pathology model posits that RRVfood predicts weight and overconsumption of food and DD strengthens this relationship. Thus, children who highly value palatable foods and have difficulty delaying rewards may be at highest risk for overconsumption. Given the moderating role of DD in the RRVfood/obesity relationship, both of these constructs are important to target in interventions developed for children.

RRVfood

RRVfood describes how hard an individual will work for food compared to either food or nonfood alternatives (Epstein et al., 2007). Dietary restraint can be extremely challenging because palatable food can serve as a potent reinforcer that increases eating behaviors of those foods. There are individual level differences in the amount of resources one is willing to devote to obtaining various commodities (e.g., food, exercise). For example, some may find apples to be a stronger reinforcer than others (e.g., they might be willing to work harder or pay more for apples as compared to others). In addition, some individuals may find certain foods (e.g., cookies) to be a stronger reinforcer as compared to other foods (e.g., apples). This level of reinforcement is typically measured by holding the effort or price value constant for apples at a low value and increasing the effort or cost requirement for cookie. Individuals who are willing to allocate more resources at higher levels of effort for the cookie rather than consuming the lower cost apple may view the cookie as a more powerful reinforcer. Thus, these individuals may have more difficulty reducing consumption of cookies or other highly valued foods. Others may find food to be a stronger reinforcer than alternative, nonfood related commodities or activities (e.g., exercise; Epstein et al., 2018; Temple et al., 2008; Vervoort et al., 2017).

Research on the reinforcing value of food among children ages 8–12 found notable differences in RRVfood between children with a BMI in the overweight range and children of normal weight status (Temple et al., 2008). In particular, children with an overweight BMI found food to be a stronger reinforcer, and had higher rates of energy consumption, compared to their normal BMI counterparts. For children with a BMI in the overweight range, RRVfood was consistently higher compared to nonfood alternatives (e.g.,, handheld video games, word searches, or magazines). On the other hand, children who did not have BMIs in the overweight range found nonfood alternatives to be stronger reinforcers than food. Finally, Temple et al. (2008) reported that RRVfood was highly correlated with energy intake and child BMI z-scores. Similar findings were reported for a sample of preschool-age children (3–5 years old) who were asked to complete an RRVfood task (Rollins et al., 2014). Rollins et al. (2014) identified that children with higher BMI z-scores and reward sensitivity values worked harder (clicked a button faster) to acquire food compared to children with lower BMI z-scores and reward sensitivity values. Further supporting these findings, longitudinal research has demonstrated a marked association between RRVfood and weight status among children (ages 7–10) such that RRVfood at baseline predicted child weight gain (changes in BMI and fat mass index) at a 1-year follow up (Hill et al., 2009).

Delay Discounting (DD)

DD is a behavioral measure of impulsivity and describes the degree to which one can delay larger, later rewards to smaller, more immediate ones (Epstein et al., 2008a; Odum, 2011; Rasmussen et al., 2010; Stojek & MacKillop, 2017; Mischel & Metzner, 1962). Children who are impulsive may consume energy dense foods more frequently compared to children who are able to delay rewards. DD is typically measured by asking individuals to make a series of choices, requiring them to select an immediate monetary or food choice today (e.g., $25 or one cookie today) versus a larger choice at a later date (e.g., $50 or two cookies tomorrow). Several items with a range of delays and a range of prices are assessed to quantify a pattern of choice behavior.

A large prospective longitudinal study, involving over 1,000 children across the United States, demonstrated that poor self-regulation and high levels of DD placed children at risk of excessive weight gain as they aged (Francis & Susman, 2009). In particular, children were asked to complete measures on DD and self-control at ages 3 and 5 and were then weighed at six time points until age 12. Children who scored high on DD and low on self-control gained the most amount of weight over the course of the study. Likewise, a longitudinal study found that children who failed to delay gratification at 4 years old (those unable to wait 7 min for a food reward) were 1.3 times as likely to have overweight at 11 years old compared to children who were able to delay gratification (Seeyave et al., 2009). These findings suggest that high impulsivity in early childhood may place children at risk of developing obesity in adolescence. Past cross-sectional research has also shown that adolescents ages 14–16 who were obese or overweight had significantly steeper DD scores, or were more impulsive, compared to adolescents who were a healthy weight (Fields et al., 2013). Overall, impulsivity appears to play a notable role in weight gain among youth.

In sum, BE theory has been applied widely to health behavior research and explains choice behavior and individual differences in resource allocation. In terms of dietary choices, food can serve as a strong reinforcer and therefore some individuals are likely to dedicate more resources toward obtaining food. RRVfood describes how reinforcing certain food items are for individuals compared to alternatives (e.g., exercise). DD describes the degree to which one is able to delay immediate food rewards. These BE constructs can also be conceptualized and applied at higher systems levels (e.g., environmental, policy), and conceptualizing BE theory applications of obesity prevention at higher systems levels may increase the public health impact of evidence-based interventions grounded in BE.

A Social Ecological Perspective

As previously mentioned, most childhood obesity prevention interventions focus on individual levels and do not consider higher-level influences such as environment and policy context. The social ecological model (SEM; U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2015; Story et al., 2008) as applied to obesity describes factors that influence obesity-related behaviors at multiple levels (e.g., individual, environmental, policy). The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (2010) coined the phrase “Health starts where we live, learn, work, and play.” The SEM emphasizes that individuals do not live in a vacuum; rather, they live in a broader context that influences behavior at the individual level. For example, a child may report high levels of fast food consumption and low levels of fruit and vegetable consumption, but upon assessment of broader context, this child may also live in a food desert and have limited access to fruits and vegetables and other healthful foods. Therefore, for this child, more healthful foods are less available and more difficult to access.

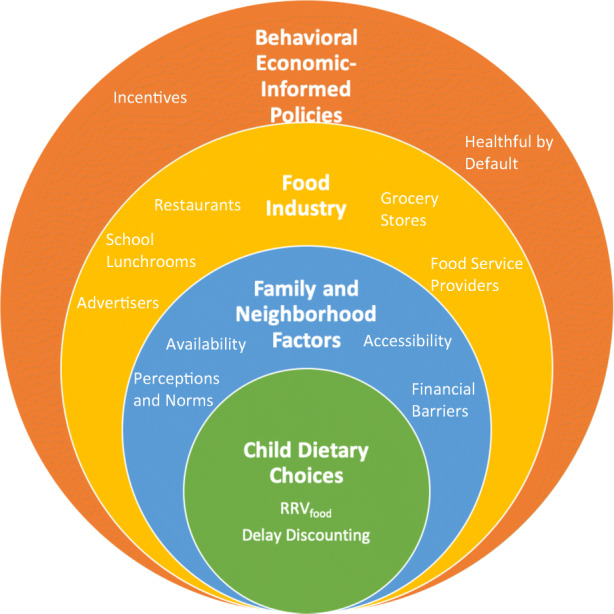

Although the SEM and BE concepts have not before been applied to childhood obesity in an integrated fashion, BE theory can be applied at each level of the SEM (see Fig. 1). In general, SEM describes how an individual makes decisions given constraints and resources in their environment. Likewise, BE posits that, to some degree, food choices are also influenced by the “choice architecture,” or the context in which health decisions are made (Thaler & Sunstein, 2009). As seen in Fig. 1, at the individual level, RRVfood and DD predict dietary choices, but they are couched in a broader context. These individual factors are directly influenced by family/neighborhood factors such as availability and accessibility, which are influenced by higher-level food industry factors. Nutrition policies, such as incentive-based and default approaches, are macrolevel predictors that affect every level nested within the SEM.

Fig. 1.

A Social Ecological Model of Child Nutrition Policies Informed by Behavioral Economics. Behavioral-economic informed policies influence child dietary choices by targeting each level of the social ecological model. These policies affect the foods distributed or marketed by the food industry, altering family and neighborhood access, which affects child dietary choices. Individual-level factors including relative reinforcing value of food and delay discounting are the driving mechanisms that determine the effectiveness of policy at each level of the model, because dietary choices are ultimately decided by sufficient shifts in the environment to increase or decrease reinforcement of healthful foods.

Policy approaches to obesity prevention are underexplored, despite the fact that they may have a greater public health impact on reversing the obesity epidemic (Berge et al., 2017). To date, policies geared toward reducing the rate of childhood obesity have not been rooted in theory and have instead relied on provision of health information as their catalyst for change. Such health-information policies include MyPlate, nutrition labeling, and including nutrition information on menus (Guthrie et al., 2015). In recent research, MyPlate has been found to be both preferred and better at conveying information related to variety and proper proportions of food than MyPyramid, by providing a visual display of portion sizes that actually reflects how a person’s plate should look (as cited in Guthrie et al., 2015). However, previous research has suggested some limitations to MyPlate in its current form including lack of information regarding recommended consumption of sweets, fats, and extra calories (Baker, 2013) and oversimplification of the food group display (e.g., food group portions are depicted as completely separate, when many dishes may have ingredients representative of multiple food groups; Guthrie et al., 2015). Nutrition labeling of packaged foods has been found to be remarkably effective in influencing food decisions among adults, with 77% of U.S. adults in a national survey indicating using labels when buying a food product always, most of the time, or sometimes (Lin et al., 2016). However, nutrition information included on the packaging may be more difficult for children to interpret and could ultimately be misleading. Finally, as mandated by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (Food & Drug Administration, 2014), restaurants are now required to provide nutrition information for each of their menu items. Extant literature on the effectiveness of menu labeling for children is limited, but so far, strong effects have not been reported (Conklin et al., 2005; Hunsberger et al., 2015).

Given the limitations of health-information based policies, policy approaches to obesity prevention may be further enhanced if informed by extensively researched and applicable theoretical approaches such as BE. Previous reviews have described policy approaches to public health problems (Matjasko et al., 2016) and obesity (Downs et al., 2009; Kersh et al., 2011; Nestle & Jacobson, 2000), but few have explored how BE models might be applied at the policy level for children. Likewise, reviews have been published suggesting BE theory applications to obesity conceptualization and policy (Guthrie et al., 2015), but no theoretical review to date has thoroughly investigated existing nutrition policies beyond popular health-information based policies. Liu et al. (2013) and Roberto and Kawachi (2014) review BE informed food policies, but do not focus explicitly on children nor on DD and RRVfood. The purpose of this manuscript is to provide a theoretical review of policy-level childhood obesity prevention nutrition initiatives informed by BE. We provide a review of the current literature as well as limitations of this literature and future directions. Exploration of BE theory applications for nutrition policies may help to inform future theoretically grounded policy-level public health interventions.

Behavioral Economic Application to Policy-Level Childhood Obesity Prevention

The primary nutrition policy approaches informed by BE can be categorized as (1) incentives- or price manipulation-based policies (e.g., sugary drink tax, SNAP pilot, prizes) and (2) policies that make the healthful choice the default which focus on shifting the choice architecture by manipulating the accessibility and appeal of healthful food items (e.g., advertising regulations, Healthy Hunger Free Kids Act/National School Lunch Program, default items).

Incentives/Price Manipulation-Based Policies

According to Fig. 1, incentives/price changes enacted at higher policy levels of the SEM may change consumption behavior based on price change. Nutrition policy efforts have recognized the power of incentives/price manipulation in driving consumer dietary consumption behavior decisions. Because of the individual tendency to weigh risks and benefits of food choices in the moment, immediate rewards or consequences have the potential to impact consumer choice more than consideration of long-term health outcomes. Three primary applications of these types of policies targeting child nutrition are the sugary drink tax (price manipulation-based), the USDA’s Healthy Incentives Pilot (incentive-based), and prize-based (incentive-based) approaches. Incentives can be conceptualized as a type of reinforcer, which increase the probability of a behavior occurring (Jeffery, 2012), whereas price manipulation-based approaches decrease this probability (e.g., deciding not to buy a soda because it will cost more).

Sugary Drink Tax

The sugary drink tax has amassed considerable support and controversy in recent years. BE theory posits that taxes on sugary drinks would decrease demand and therefore, fewer people would buy them. The existing research on sugary drink taxes provides initial evidence in support of this notion. Four months following the implementation of the first city-level tax on sugary drinks in Berkeley, California, sugary drink consumption in low-income neighborhoods in Berkeley dropped by 21% and increased by 4% in comparison cities. Water consumption subsequently rose by 63% in those same neighborhoods compared to a 19% increase in the comparison cities (Falbe et al., 2016). Another study of the sugary drink tax in Mexico showed a decline in the purchase of taxed drinks by 6% and increases in purchases of other beverages such as water by 4% during the first year of implementation. By the end of the first year, sugary drink purchases reached a 12% decline overall, with a 17% decline observed in low-income households in particular (Colchero et al., 2016). These initial results suggest that taxes on certain less healthful products may create enough of a cost to outweigh taste-related benefits and nudge consumers toward a healthier alternative selection.

However, there are some potential limitations to the sugary drink tax. First, it is unclear how much more affordable the healthful options have to be in comparison to less healthful options and how these effects would hold up in the most affluent neighborhoods where price may not be a salient punishment (Finkelstein et al., 2010). Second, there has been significant push back against the sugary drink tax by retailers and the beverage industry following implementation (Muth et al., 2019). In Chicago, for example, a sugary drink tax instituted in August 2017 was quickly repealed fewer than 3 months later as a product of errors in implementation, a series of legal complications, and extensive lobbying by the beverage industry, during which time-limited public approval also became an issue (Dewey, 2017). As another example, in response to pressure from the American Beverage Industry, California lawmakers passed a law in June 2018 prohibiting any new sugary drink taxes until 2031, and other states have passed similar laws (Muth et al., 2019). Although there is evidence that taxes can effectively reduce consumer purchases of sugary drinks, industry backlash presents a serious barrier to the introduction of such taxes in additional U.S. cities.

Healthy Incentives Pilot

The Healthy Incentives Pilot (HIP), conducted in partnership with the USDA, is an incentives-based policy initiative to increase healthful eating. HIP participants included 5,000 households that were credited 30¢ back for every Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) dollar spent on targeted fruits and vegetables (TFVs) between 2011 and 2012 (Bartlett et al., 2014). TFVs were described as “fresh, canned, frozen, and dried fruits and vegetables without added sugars, fats, oils, or salt, but excluded white potatoes and 100% fruit juice” (Bartlett et al., 2014). The study found that HIP participants consumed 26% more TFVs than nonparticipants, and that HIP households spent more on TFVs and had more of those foods in the home compared to both baseline and non-HIP households. It is interesting that participating retailers also reported behavioral change, ordering more shipments of the TFVs, increasing restocking of those items, and increasing shelf space for them (Bartlett et al., 2014). These results provide further evidence that financial incentives may be an effective method of promoting health behavior change in low-income families by altering the cost–benefit relationship between nutrient dense and high calorie foods, thus increasing the RRVfood of purchasing healthful foods. In addition, such interventions may then influence the food environment to further encourage families to make more healthful food decisions, as seen in the response of retailers to increase the visibility and convenience of targeted fruits and vegetables. However, once the financial incentive is removed, families may be less likely to sustain their healthful behavior change over time (Jeffery, 2012).

Prize-Based Incentives

Another incentive-based policy approach that frequently targets children is the pairing of certain food items with prizes. In an experimental study of the effects of behavioral incentive as well as nutrition education on child food consumption, List and Samek (2015) attempted to increase selection of dried fruit relative to cookies either by delivering a message on the healthiness of fruit and showing the MyPyramid visual or by offering small prizes contingent on selecting fruit. At baseline, children chose the fruit about 17% of the time, but following the introduction of the prize incentive, fruit increased as a preference to around 75%. The educational message alone did not have a significant effect, but when presented alongside the behavioral incentive, fruit selection increased to 86%. This interaction was the only intervention effect that continued to affect choice posttreatment, suggesting that children may be best influenced by incentive-based approaches.

Summary

Incentive- and price manipulation-based policies may be utilized to reduce the probability of less healthful behaviors (e.g., purchasing sugary drinks) or increase the probability of healthful behaviors (e.g., purchasing fruits and vegetables). Different strategies of incentives may be more effective for different family members, with caregivers perhaps responding more to financial incentive and children attending to prize-based incentives. Future research should determine which types of incentives/price manipulations are most effective across family members. As incentives provide an immediate reward, these policies may result in more immediate behavior change. However, once an incentive is removed, children and families may lose the motivation to continue with a desired health behavior. If behavioral incentives can be offered consistently over time, they may be a highly effective way of altering families’ motivation and decisions, but otherwise may not be able to produce significant change unless paired with another policy approach. Future research should determine whether the removal of incentives in this context results in return to baseline behaviors. Although findings are promising, it may be important for BE researchers to determine whether these higher-level policy approaches have a short- or long-term influence on consumption behaviors.

Healthful Choice as the Default Policies

Our SEM model posits that policy strategies aiming to increase the accessibility and appeal of healthful food items for children will shift the choice architecture and have a trickle-down effect on food choice (Fig. 1). Children and their caregivers respond to cues such as visual appeal, availability, and implied norms when selecting foods for consumption (Chou et al., 2004; Guthrie et al., 2015). In particular, children may show a status quo bias, such that they will be more likely to select foods that are offered as the norm or default (Liu et al., 2013). From a BE perspective, healthful choice as the default policies essentially restrict the accessibility and availability of less healthful alternatives. If children must work harder to obtain the less healthful item, they may be more likely to select the healthful default item, even if they have a more difficult time delaying rewards. When healthful items are the default and less healthful ones are restricted/harder to obtain, children might be more likely to shift their behavior. Three examples of such policies are advertising that promotes healthful foods, the Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act (HHFKA), and healthy-by-default ordinances.

Advertising Regulations

After the release of policy recommendations by the Institute of Medicine to limit food advertising of calorie-dense foods, the food industry responded by creating the self-regulatory Children’s Food and Beverage Advertising Initiative (CFBAI) in 2009, pledging to limit food advertising to items meeting nutritional standards laid out by each company (e.g., General Mills, Kellogg Company) and to only use licensed characters when marketing nutritious foods (Kunkel et al., 2015). These regulations appear to be promising, as they would manipulate environmental influences to increase the salience and appeal of nutritious food items and shift the attention away from less healthful products. These nutritious foods may also be viewed as more accessible than before, given their increased visibility, and their advertisements may have social influences as well in terms of modeling and perceived preferences of peers. From a BE perspective, one might predict that generating advertisements focused on promoting healthful foods would increase the exposure of alternatives for kids, whereas eliminating advertisements for unhealthful foods would reduce their exposure to highly palatable options. This shift in attention may increase demand and eventual consumption of the nutritious food options. Despite the promising implications of this initiative, a systematic content analysis of food advertisements from 2007 and 2013 (before and after the implementation of CFBAI) indicated that whereas 100% of advertised products by CFBAI participants met their pledged nutritional standards, the majority of these products continued to be nutrient poor according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services nutrition guidelines (Kunkel et al., 2015). Furthermore, there were no significant improvements in the overall nutritional quality of marketed foods since the initiative was adopted (Kunkel et al., 2015), suggesting that a more formal policy in place of industry self-regulation may be needed to properly address less healthful food advertising.

Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act (HHFKA)

One of the widest-reaching examples of an environmental policy approach is the Healthy Hunger Free Kids Act of 2010 (HHFKA), which mandated the National School Lunch and School Breakfast Programs to improve school nutrition quality and to reduce child hunger in schools (Food & Nutrition Service, 2012). Under this act, schools have been required to do the following: “[I] ncrease the availability of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and fat-free and low-fat fluid milk in school meals; reduce the levels of sodium, saturated fat and trans fat in meals; and meet the nutrition needs of school children within their calorie requirements” (Food & Nutrition Service, 2012). Schools have also been expected to restrict serving sizes based on age-based calorie consumption standards and require children to select a fruit or vegetable each day. Preliminary research has shown that from pre- to postimplementation of HHFKA in an urban, low-income community, children increased their selection of fruit by 23% and vegetables by 16.2% (Cohen et al., 2014). Although concerns have emerged in relation to liking of the foods and plate waste (food selected but not consumed), research has found no significant differences in school meal participation or in plate waste before versus after the implementation of the HHFKA (Boehme & Logomarsino, 2017; Cohen et al., 2014; Johnson et al., 2016). BE posits that increasing accessibility of certain food items can increase selection of those foods. In particular, if fruits and vegetables are easier for children to obtain, they will be more likely to increase their intake of those foods as less effort is required to obtain them (Terry-McElrath et al., 2014). Further, restricting serving sizes may promote children to eat the right amount for their age rather than having the difficulty of estimating their own portions and potentially overeating (Roberto & Kawachi, 2014).

Despite evidence that the HHFKA implementation has resulted in more healthful eating among children, some of the initial standards have recently been rolled back. On December 6, 2018, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) announced that schools will now be allowed to serve fewer whole grains, low-fat flavored milks (instead of fat-free only), and foods higher in sodium. Future research should assess whether these rollbacks have any impact on the dietary quality of children in the school environment.

Healthy by Default

In consideration of reducing decision-making between healthful and less healthful options, in September 2018, California passed the “Healthy By Default” Kids’ Meal Beverages Bill, which requires either milk or water to be the default beverages for children’s meals in restaurants (Voices for Healthy Kids Action Center, 2019). This default strategy ties directly to BE theory, as children tend to seek the easiest option and accept the norm, reducing their decision-making burdens by accepting what is offered to them. Although there is not yet sufficient evidence to determine the impact on healthful purchases and consumption, research conducted by Anzman-Frasca et al. (2015) suggests that children may respond to healthful default menu options with more healthful ordering patterns. This study analyzed a total of 352,192 orders before and after implementation of a healthy by default menu, with the original menu offering more healthful and less healthful side dish options as well as choice of beverage (milk, juice, or fountain drink) and the new menu removing the less healthful side dish and fountain drinks as menu options (although children could still request them). Results indicated that children increased orders of default fruit and vegetable side dishes (i.e., strawberries, mixed vegetables, or salad) as well as default milk and juice beverage options, whereas orders of fries and fountain drinks (i.e., soda, lemonade) decreased. These findings are promising as they suggest that status quo bias may have a strong effect on children’s food choices such that if healthful items are presented as the default, children are likely to accept the default and make healthful decisions.

Another study by Peters et al. (2016) assessed kids’ meal purchases at Walt Disney World following the introduction of healthful default sides (grapes, apple slices, unsweetened apple sauce, or baby carrots) and beverages (low-fat milk, water, or 100% juice) in place of the previous defaults of fries and a soft drink. Healthful default sides were displayed on picture boards, but all options were listed on the menu such that children could opt out of the healthful default for fries or a soft drink. Sales data were obtained from 94 quick-service restaurants and 51 table-service restaurants over the course of 3 years following implementation of the healthful defaults, but preintervention data could not be collected as the healthful sides were not available prior to their introduction as the default. On average, children accepted the defaults for quick-service restaurants (49.4% for side, 67.8% for beverage) more often that at table-service restaurants (40.3% for side, 45.6% for beverage), suggesting that children and their caregivers may be accepting of default healthful options. However, families may be more interested in convenience and experience more time pressure when ordering from quick-service restaurants, influencing them to more frequently choose the default (Peters et al., 2016).

Summary

Healthful by default policies suggest that, as nutritious food options are characterized as the standard for consumption, those foods may be seen as more accessible and appealing, and children and their caregivers will be more likely to accept the status quo or default rather than increase their effort to choose a less healthful option. However, in order for these policies to be effective, healthfulness of foods must be determined by more consistent nutritional guidelines, as emphasized by the outcomes of the CFBAI. As mentioned in the above section on incentive- and price manipulation-based approaches, future research may explore whether default policy approaches have a short- or long-term influence on RRVfood and/or DD and subsequent long-term eating habits.

Discussion

The purpose of this article was to provide a theoretical review of policy-level childhood obesity prevention nutrition initiatives informed by BE. We reviewed two primary approaches to childhood obesity prevention nutrition policies: (1) incentives-/price manipulation-based policies (e.g., sugary drink tax, SNAP pilot, prizes), and (2) policies that make healthful choices the default (advertising regulations, Healthy Hunger Free Kids Act/National School Lunch Program, default items). BE theory has largely focused on individual-level predictors or explanations of behavior but applications and interventions at higher levels of the SEM are underexplored. The policies we reviewed in this article certainly have BE linkages, but we argue that it is important that future policies are directly informed by BE concepts and research findings. Just as it is important for our individual-level interventions to be informed by theory, it is important that our policies are informed by theory as well. SEM is a key framework for BE researchers to consider, especially from a public health perspective. Getting this work out of labs and into real world settings, communities, and policies is an essential next step in the field of BE to combat the child obesity epidemic.

Limitations and Future Directions

The current review should be interpreted within the context of its limitations. First, the review focuses solely on BE informed nutrition-related policies. However, future reviews may extend this work to other health behaviors related to obesity such as physical activity or sedentary behavior. Further, although research has identified limitations to the effectiveness of information-based policies, research has not yet examined the relative effectiveness of incentive-based policies versus healthful by default policies. It will be really important to determine whether, as SEM posits, these higher-level policies will have a “trickle down” effect on individual behavior. In addition, research examining child-level effects of nutrition-related policies are lacking. We reviewed the available research, but future studies should examine the direct effects of policy changes on child health outcomes. Although these policies are informed by BE, no research to date has tested whether these policy interventions have any short- or long-term effect on the very BE variables they tend to target. Further, we focused this review on policy-level interventions informed by BE. However, many multilevel interventions have been developed and tested that target several levels of the SEM (e.g., Crespo et al., 2012; Trude et al., 2018; Trude et al., 2019). Future reviews should focus on the efficacy of these interventions. Finally, several of the key research studies supporting environmental BE nutrition promotion for children have recently been retracted from the literature given allegations of p-hacking and other research ethics concerns (Bauchner, 2018; Wansink et al., 2017; Wansink et al., 2018). Given these concerns and evolving health legislation, it is essential that future research replicate previous studies utilizing ethical research designs and analytic approaches to determine the effectiveness of these strategies.

Overall, this theoretical review is the first to our knowledge to conceptualize BE applications to childhood obesity prevention nutrition policies. The development of future childhood obesity prevention policies may benefit from the application of our proposed theoretical model to increase population-wide impact. It is noteworthy that there are several interventions that have been developed and tested extensively at the individual level that may hold promise at the policy level. For example, Epstein’s Traffic Light Diet (Epstein et al., 2008b), which facilitates decision making around the consumption of healthful versus less nutritious foods, and the Food Dudes program (Morrill et al., 2016), which utilizes incentives for healthful eating, may be implemented at higher levels such as school-based policies to affect more children. Future research should consider possible implementation of these and other evidence-based interventions at the policy level.

Appendix

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Anzman-Frasca S, Mueller MP, Sliwa S, Dolan PR, Harelick L, Roberts SB, Washburn K, Economos CD. Changes in children's meal orders following healthy menu modifications at a regional US restaurant chain. Obesity. 2015;23(5):1055–1062. doi: 10.1002/oby.21061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker SD. College students’ perceptions of MyPlate and ChooseMyPlate.gov. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition & Dietetics. 2013;113(Suppl. 3):A-82. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2013.06.288. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Banfield EC, Liu Y, Davis JS, Chang S, Frazier-Wood AC. Poor adherence to US dietary guidelines for children and adolescents in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey population. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition & Dietetics. 2016;116(1):21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, S., Klerman, J., Olsho, L., Logan, C., Blocklin, M., Beauregard, M., Enver, A. & Abt Associates. (2014). Evaluation of the Healthy Incentives Pilot (HIP): Final report. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service. https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/ops/HIP-Final.pdf

- Berge, J. M., Adamek, M., Caspi, C., Loth, K. A., Shanafelt, A., Stovitz, S. D., Trofholz, A., Grannon, K Y., & Nanney, M. S (2017). Healthy Eating and Activity Across the Lifespan (HEAL): A call to action to integrate research, clinical practice, policy, and community resources to address weight-related health disparities. Preventive Medicine, 101, 199–203. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bickel WK, Jarmoloqicz DP, Mueller ET, Gatchalian KM. The behavioral economics and neuroeconomics of reinforcer pathologies: Implications for etiology and treatment of addiction. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2011;13:406–415. doi: 10.1007/s11920-011-0215-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehme JS, Logomarsino JV. Reducing food waste and increasing fruit and vegetable consumption in schools. Health Behavior & Policy Review. 2017;4(3):282–293. doi: 10.14485/HBPR.4.3.9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bauchner H. Notice of retraction: “Consequences of belonging to the ‘Clean Plate Club’” and “Preordering school lunch encourages better food choices by children” by Brian Wansink. JAMA Pediatrics. 2018;172(11):1017. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.3747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr KA, Daniel TO, Lin H, Epstein LH. Reinforcement pathology and obesity. Current Drug Abuse Reviews. 2011;4(3):190–196. doi: 10.2174/1874473711104030190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou SY, Grossman M, Saffer H. An economic analysis of adult obesity: results from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Journal of Health Economics. 2004;23(3):565–587. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JF, Richardson S, Parker E, Catalano PJ, Rimm EB. Impact of the new US Department of Agriculture school meal standards on food selection, consumption, and waste. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2014;46(4):388–394. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colchero MA, Popkin BM, Rivera JA, Ng SW. Beverage purchases from stores in Mexico under the excise tax on sugar sweetened beverages: Observational study. BMJ. 2016;352:h6704. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h6704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conklin MT, Cranage DA, Lambert CU. Nutrition information at point of selection affects food chosen by high school students. Journal of Child Nutrition & Management. 2005;20(2):97–108. [Google Scholar]

- Crespo NC, Elder JP, Ayala GX, Slymen DJ, Campbell NR, Sallis JF, McKenzie TL, Baquero B, Arredondo EM. Results of a multi-level intervention to prevent and control childhood obesity among Latino children: The Aventuras Para Niños Study. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2012;43(1):84–100. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9332-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis R, Campbell R, Hildon Z, Hobbs L, Michie S. Theories of behaviour and behaviour change across the social and behavioural sciences: A scoping review. Health Psychology Review. 2015;9(3):323–344. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2014.941722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, C. (2017). Why Chicago’s soda tax fizzled after two months—and what it means for the anti-soda movement. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2017/10/10/why-chicagos-soda-tax-fizzled-after-two-months-and-what-it-means-for-the-anti-soda-movement/

- Downs JS, Loewenstein G, Wisdom J. Strategies for promoting healthier food choices. American Economic Review. 2009;99(2):159–164. doi: 10.1257/aer.99.2.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein LH, Dearing KK, Temple JL, Cavanaugh MD. Food reinforcement and impulsivity in overweight children and their parents. Eating Behaviors. 2008;9(3):319–327. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein LH, Leddy JJ, Temple JL, Faith MS. Food reinforcement and eating: a multilevel analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133(5):884–906. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.5.884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein LH, Paluch RA, Beecher MD, Roemmich JN. Increasing healthy eating vs. reducing high energy-dense foods to treat pediatric obesity. Obesity. 2008;16(2):318–326. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, L. H., & Saelens, B. E. (2000). Behavioral economics of obesity: Food intake and energy expenditure. In W. K. Bickel & R. E. Vuchinich (Eds.), Reframing health behavior change with behavioral economics (pp. 293–311). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Epstein LH, Salvy SJ, Carr KA, Dearing KK, Bickel WK. Food reinforcement, delay discounting and obesity. Physiology & Behavior. 2010;100:438–445. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein LH, Stein JS, Paluch RA, MacKillop J, Bickel WK. Binary components of food reinforcement: Amplitude and persistence. Appetite. 2018;120:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2017.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falbe J, Thompson HR, Becker CM, Rojas N, McCulloch CE, Madsen KA. Impact of the Berkeley excise tax on sugar-sweetened beverage consumption. American Journal of Public Health. 2016;106(10):1865–1871. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields SA, Sabet M, Reynolds B. Dimensions of impulsive behavior in obese, overweight, and healthy-weight adolescents. Appetite. 2013;70:60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.06.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein EA, Zhen C, Nonnemaker J, Todd JE. Impact of targeted beverage taxes on higher-and lower-income households. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2010;170(22):2028–2034. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food & Drug Administration. (2014). Food labeling; Nutrition labeling of standard menu items in restaurants and similar retail food establishments; Final rule. Federal Register. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2014/12/01/2014-27833/food-labeling-nutrition-labeling-of-standard-menu-items-in-restaurants-and-similar-retail-food [PubMed]

- Food & Nutrition Service. (2012). Nutrition standards in the National School Lunch and School Breakfast Programs; Final rule. Federal Register. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2012-01-26/pdf/2012-1010.pdf [PubMed]

- Francis LA, Susman EJ. Self-regulation and rapid weight gain in children from age 3 to 12 years. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2009;163(4):297–302. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2008.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie J, Mancino L, Lin CTJ. Nudging consumers toward better food choices: policy approaches to changing food consumption behaviors. Psychology & Marketing. 2015;32(5):501–511. doi: 10.1002/mar.20795. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hill C, Saxton J, Webber L, Blundell J, Wardle J. The relative reinforcing value of food predicts weight gain in a longitudinal study of 7–10-y-old children. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2009;90(2):276–281. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunsberger, M., McGinnis, P., Smith, J., Beamer, B. A., & O’Malley, J. (2015). Calorie labeling in a rural middle school influences food selection: Findings from community-based participatory research. Journal of Obesity, 2015, 531690. 10.1155/2015/531690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hursh, S. R. (2000). Behavioral economic concepts and methods for studying health behavior. In W. K. Bickel & R. E. Vuchinich (Eds.), Reframing health behavior change with behavioral economics (pp. 27–60). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Jeffery RW. Financial incentives and weight control. Preventive Medicine. 2012;55:S61–S67. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DB, Podrabsky M, Rocha A, Otten JJ. Effect of the Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act on the nutritional quality of meals selected by students and school lunch participation rates. JAMA Pediatrics. 2016;170(1):e153918–e153918. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.3918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kersh, R., Stroup, D. F., & Taylor, W. C. (2011). Childhood obesity: a framework for policy approaches and ethical considerations. Preventing Chronic Disease, 8(5), A93. http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2011/sep/10_0273.htm. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kunkel DL, Castonguay JS, Filer CR. Evaluating industry self-regulation of food marketing to children. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2015;49(2):181–187. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lake AA, Mathers JC, Rugg-Gunn AJ, Adamson AJ. Longitudinal change in food habits between adolescence (11–12 years) and adulthood (32–33 years): The ASH30 Study. Journal of Public Health. 2006;28(1):10–16. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdi082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C. T. J., Zhang, Y., Carlton, E. D., & Lo, S. C. (2016). 2014 FDA health and diet survey. Center for Food Safety & Applied Nutrition, Food & Drug Administration.https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Food/FoodScienceResearch/ConsumerBehaviorResearch/UCM497251.pdf?source=govdelivery&utm_medium=email&utm_source=govdelivery

- List JA, Samek AS. The behavioralist as nutritionist: Leveraging behavioral economics to improve child food choice and consumption. Journal of Health Economics. 2015;39:135–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu PJ, Wisdom J, Roberto CA, Liu LJ, Ubel PA. Using behavioral economics to design more effective food policies to address obesity. Applied Economic Perspectives & Policy. 2013;36(1):6–24. doi: 10.1093/aepp/ppt027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Madden, G. J. (2000). A behavioral economics primer. In W. K. Bickel & R. E. Vuchinich (Eds.), Reframing health behavior change with behavioral economics (pp. 3–26). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Martinez JA. Body-weight regulation: Causes of obesity. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 2000;59(3):337–345. doi: 10.1017/S0029665100000380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matjasko JL, Cawley JH, Baker-Goering MM, Yokum DV. Applying behavioral economics to public health policy: Illustrative examples and promising directions. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2016;50(5):S13–S19. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikkilä V, Räsänen L, Raitakari OT, Pietinen P, Viikari J. Consistent dietary patterns identified from childhood to adulthood: The cardiovascular risk in Young Finns Study. British Journal of Nutrition. 2005;93(6):923–931. doi: 10.1079/BJN20051418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mischel W, Metzner R. Preference for delayed reward as a function of age, intelligence, and length of delay interval. Journal of Abnormal & Social Psychology. 1962;64(6):425. doi: 10.1037/h0045046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrill BA, Madden GJ, Wengreen HJ, Fargo JD, Aguilar SS. A randomized controlled trial of the Food Dudes Program: tangible rewards are more effective than social rewards for increasing short-and long-term fruit and vegetable consumption. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition & Dietetics. 2016;116(4):618–629. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2015.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muth ND, Dietz WH, Magge SN, Johnson RK. Public policies to reduce sugary drink consumption in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2019;143(4):e20190282. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. (2018). Health, United States, 2017: With special feature on mortality. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/2017/019.pdf [PubMed]

- National Center for Health Statistics (2017). Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015–2016. NCHS data brief, No. 288. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db288.htm [PubMed]

- Nestle M, Jacobson MF. Halting the obesity epidemic: A public health policy approach. Public Health Reports. 2000;115(1):12. doi: 10.1093/phr/115.1.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odum AL. Delay discounting: I'm a k, you're a k. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2011;96(3):427–439. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2011.96-423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters J, Beck J, Lande J, Pan Z, Cardel M, Ayoob K, Hill JO. Using healthy defaults in Walt Disney World restaurants to improve nutritional choices. Journal of the Association for Consumer Research. 2016;1(1):92–103. doi: 10.1086/684364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen EB, Lawyer SR, Reilly W. Percent body fat is related to delay and probability discounting for food in humans. Behavioural Processes. 2010;83(1):23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. (2010). A new way to talk about the social determinants of health. Carger, Christiano, & Westen.http://sph.umd.edu/sites/default/files/files/vpmessagingguidewebinarslides.pdf.

- Roberto CA, Kawachi I. Use of psychology and behavioral economics to promote healthy eating. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2014;47(6):832–837. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollins BY, Loken E, Savage JS, Birch LL. Measurement of food reinforcement in preschool children: Associations with food intake, BMI, and reward sensitivity. Appetite. 2014;72:21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo K, Sahoo B, Choudhury AK, Sofi NY, Kumar R, Bhadoria AS. Childhood obesity: causes and consequences. Journal of Family Medicine & Primary Care. 2015;4(2):187. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.154628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeyave DM, Coleman S, Appugliese D, Corwyn RF, Bradley RH, Davidson NS, Kaciroti N, Lumeng JC. Ability to delay gratification at age 4 years and risk of overweight at age 11 years. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2009;163(4):303–308. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegelman BM, Flier JS. Obesity and the regulation of energy balance. Cell. 2001;104(4):531–543. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00240-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stojek MM, MacKillop J. Relative reinforcing value of food and delayed reward discounting in obesity and disordered eating: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2017;55:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Story M, Kaphingst KM, Robinson-O'Brien R, Glanz K. Creating healthy food and eating environments: Policy and environmental approaches. Annual Review Public Health. 2008;29:253–272. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temple JL, Legierski CM, Giacomelli AM, Salvy SJ, Epstein LH. Overweight children find food more reinforcing and consume more energy than do nonoverweight children. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2008;87(5):1121–1127. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.5.1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry-McElrath YM, O'Malley PM, Johnston LD. Accessibility over availability: Associations between the school food environment and student fruit and green vegetable consumption. Childhood Obesity. 2014;10(3):241–250. doi: 10.1089/chi.2014.0011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaler, R. H., & Sunstein, C. R. (2009). Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. Penguin.

- Trude AC, Surkan PJ, Cheskin LJ, Gittelsohn J. A multilevel, multicomponent childhood obesity prevention group-randomized controlled trial improves healthier food purchasing and reduces sweet-snack consumption among low-income African-American youth. Nutrition Journal. 2018;17(1):96. doi: 10.1186/s12937-018-0406-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trude AC, Surkan PJ, Steeves EA, Porter KP, Gittelsohn J. The impact of a multilevel childhood obesity prevention intervention on healthful food acquisition, preparation, and fruit and vegetable consumption on African-American adult caregivers. Public Health Nutrition. 2019;22(7):1300–1315. doi: 10.1017/S1368980018003038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. (2015). Dietary guidelines for Americans 2015–2020. https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/

- Vervoort L, Clauwaert A, Vandeweghe L, Vangeel J, Van Lippevelde W, Goossens L, Huybregts L, Lachat C, Eggermont S, Beullens K, Braet C, De Cock N. Factors influencing the reinforcing value of fruit and unhealthy snacks. European Journal of Nutrition. 2017;56(8):2589–2598. doi: 10.1007/s00394-016-1294-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voices for Healthy Kids Action Center (2019). California becomes first state to require healthy drinks on kids’ restaurant menus. American Heart Association. https://www.voicesactioncenter.org/california_becomes_first_state_to_require_healthy_drinks_on_kids_restaurant_menus

- Wansink, B., Just, D. R., Payne, C. R. (2017). Notice of retraction: Wansink, B., Just, D. R., Payne, C. R. (2012). Can branding improve school lunches? Archives of Pediatric & Adolescent Medicine 166(10), 967–968. JAMA Pediatrics, 2017;171(12):1230. Online publication. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.3136

- Wansink, B., Just, D. R., Payne, C. R., & Klinger, M. Z. (2018). Notice of retraction: Wansink, B., Just, D. R., Payne, C. R., & Klinger, M. Z. (2012). Attractive names sustain increased vegetable intake in schools. Preventive Medicine, 55(4), 330–332. Preventive Medicine, 2018 May;110:116. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yavuz HM, van Ijzendoorn MH, Mesman J, van der Veek S. Interventions aimed at reducing obesity in early childhood: A meta-analysis of programs that involve parents. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2015;56(6):677–692. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]