Abstract

Protozoan parasites have led to worldwide devastation because of their ability to cause infectious diseases. They have evolved as successful pathogens in part because of their remarkable and sophisticated ways to evade innate host defenses. This holds true for both intracellular and extracellular parasites that deploy multiple strategies to circumvent innate host defenses for their survival. The different strategies protozoan parasites use include hijacking the host cellular signaling pathways and transcription factors. In particular, the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) pathway seems to be an attractive target for different pathogens owing to their central role in regulating prompt innate immune responses in host defense. NF-κB is a ubiquitous transcription factor that plays an indispensable role not only in regulating immediate immune responses against invading pathogens but is also a critical regulator of cell proliferation and survival. The major immunomodulatory components include parasite surface and secreted proteins/enzymes and stimulation of host cells intracellular pathways and inflammatory caspases that directly or indirectly interfere with the NF-κB pathway to thwart immune responses that are directed for containment and/or elimination of the pathogen. To showcase how protozoan parasites exploits the NF-κB signaling pathway, this review highlights recent advances from Entamoeba histolytica and other protozoan parasites in contact with host cells that induce outside-in and inside-out signaling to modulate NF-κB in disease pathogenesis and survival in the host.

Keywords: entamoeba histolytica, macrophage, NF-κB – nuclear factor kappa B, innate immunity, cytokine

Introduction

Protozoan parasites have been a major concern due to their ability to cause considerable mortality and morbidity in both humans and animals worldwide (Dorny et al., 2009; Dixon et al., 2011; Fletcher et al., 2012; Kelly, 2013). They are responsible for affecting more than 500 million people across the globe (Monzote and Siddiq, 2011). Although parasitic infection and death are a major cause of concern in developing countries, they are also responsible for causing significant illness in developed countries (Fletcher et al., 2012). The burden of human protozoan parasitic infections has been aggravated because of the lack of a licensed vaccine against any of the diseases these parasites cause. Moreover, prophylaxis and treatment are dependent on drugs, which are rendered ineffective in many cases due to the emergence of drug resistance warranting the search for replacements (Andrews et al., 2014).

Protozoan parasites are unicellular eukaryotic that either reside extracellularly or intracellularly in host cells. They have evolved as successful pathogens due to their remarkable ability to evade immune responses allowing them to escape adaptive humoral and cellular immunity (Sacks and Sher, 2002). For instance, Toxoplasma gondii (Lima and Lodoen, 2019), Leishmania (Gupta et al., 2013) and Trypanosoma cruzi (Cardoso et al., 2016) evade humoral antibody response by adopting an intracellular lifestyle, while antigenic variations, in the case of extracellular pathogens such as Giardia (Prucca and Lujan, 2009), African trypanosomes (Horn, 2014), and malarial parasites (Kyes et al., 2001) that express their antigens on the surface of red blood cells, help them overcome immune destruction.

Although pathogens deploy different strategies for immune subversion, modulation of the NF-κB pathway critical for generating an immune response seems to be a crucial target (Tato and Hunter, 2002). While the NF-κB pathway is critical for mounting an immune response, pathogens have devised multiple ways to thwart this pathway to their advantage including, bacteria (Le Negrate, 2012), viruses (Santoro et al., 2003), and protozoan parasites (Heussler et al., 2001). Pathogens or their components have a remarkable ability for interfering with the NF-κB pathway at multiple levels which includes, membrane-bound receptors to downstream signaling molecules of the pathway. Host-pathogen interaction can have multiple outcomes, but pathogens that circumvent signaling pathways seem to establish a successful niche for their replication and to cause disease. Both extracellular protozoan parasites via outside-in-signaling and intracellular protozoan parasites via inside-out-signaling have devised unique ways to overcome innate defense barriers by modulating the NF-κB pathway at multiple levels. To understand the complex interaction whereby protozoan parasite interacts with the NF-κB pathway, this review will focus on recent findings on modulation of NF-κB signaling with the extracellular parasite Entamoeba histolytica (Eh) and the intracellular parasite, T. gondii.

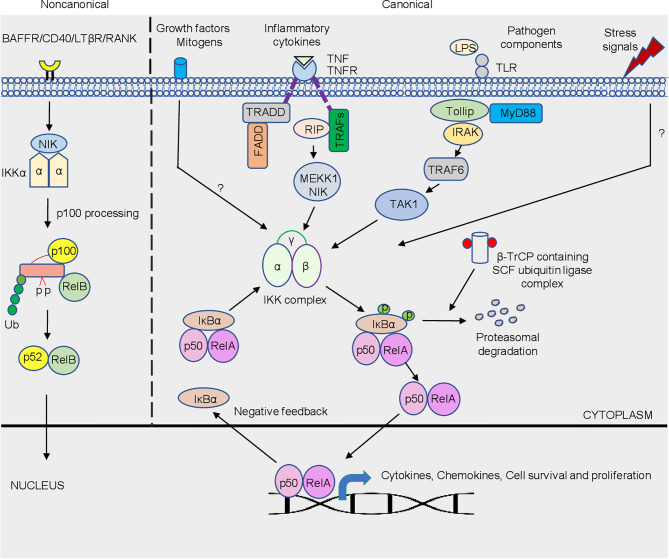

The NF-κB Pathway

NF-κB activation is a rapid event that occurs within minutes upon any trigger or stimulation that regulates a myriad of genes in host cells and does not require protein synthesis which makes this pathway an attractive target for invading pathogens (Santoro et al., 2003). NF-κB regulates diverse cellular function (Figure 1 ) which includes, promoting inflammation, an early response to pathogen that plays an indispensable role in cell survival and proliferation (Karin et al., 2002; Li and Verma, 2002). It comprises of dimeric transcription factors belonging to the Rel family. Five Rel proteins belonging to two different classes have been identified in mammalian cells (Ghosh et al., 1998; Santoro et al., 2003). c-Rel, RelA (p65) and RelB belong to one class, that are synthesized as matured form, and contain an N-terminal Rel homology domain (RHD) responsible for dimerization and DNA binding, and C-terminus that possess transcription modulating domains (Verma et al., 1995; Santoro et al., 2003; Gilmore, 2006). Another class comprise of an N-terminal RHD and a C-terminal ankyrin repeat domain-containing p105 and p100 precursor proteins that require ubiquitin-dependent processing at the C-terminus. Thus, the mature DNA-binding proteins of this class contain N-terminal RHD but lack C-terminus transcription modulating activity (Santoro et al., 2003; Gilmore, 2006). NF-κB, whose predominant form p50 and RelA subunits, remains inactive in the cytoplasm because of its association with inhibitor proteins known as inhibitors of NF-κB (IκBs), including IκBα, IκBβ and IκBϵ (Verma et al., 1995; Ghosh et al., 1998; Santoro et al., 2003). The mechanism of NF-κB activation is tightly regulated. Different stimuli or trigger, including bacterial, viral, and protozoan parasite infections may culminate in phosphorylation of IκB proteins, leading to ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of phosphorylated IκB proteins (Figure 1). The degradation of IκB sets free NF-κB that translocates to the nucleus and binds to DNA to control the transcription of different genes including, cytokines, chemokines, antimicrobial peptides, anti-apoptotic proteins, and stress-response proteins. The NF-κB pathway is activated by signaling through multiple receptors on the cell membrane. Amongst the different sensors, TLRs (Toll-like receptor) are important pathogen recognition receptors (PRR) that bind bacterial products and LPS (lipopolysaccharide) to initiate downstream signaling cascade culminating into NF-κB activation. Binding of bacterial products/LPS to TLRs initiates downstream signaling leading to the recruitment of MyD88 (myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88), a death-domain containing adaptor protein and Toll-interacting protein Tollip (Silverman and Maniatis, 2001). The pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF (tumor necrosis factor)-α signals via the NF-κB pathway. Cognate binding of TNF-α to type 1 TNF-α receptor (TNFR1) recruits the adaptor protein TNFR-associated death domain (TRADD) that acts as a docking site for the receptor interacting protein RIP and TNFR-associated factor TRAF2 that initiates downstream signaling (Chen and Goeddel, 2002). Further, downstream are MAP3K- related kinase which are thought to link receptor-complexes and stimulate an IκB kinase (IKK) complex. TRADD also binds to Fas-associated death domain (FADD) that initiate a protease cascade culminating into apoptosis (Baud and Karin, 2001). Activation of the NF-κB pathway (Figure 1) by different stimuli involves distinct scaffolding or signaling proteins, which, in addition to those mentioned above, include mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase 1(MEKK1), TNFR-associated factors (TRAFs), protein kinase C (PKC), transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)-activated kinase (TAK1), NF-κB-inducing kinase (NIK), interleukin (IL)-1-receptor-associated kinases (IRAKs), double-stranded (ds) RNA-dependent protein kinase (PKR) and several others (Silverman and Maniatis, 2001). Most of the above-mentioned proteins execute its effect by acting on another important downstream protein complex, the IκB kinase (IKK) signalosome complex that plays an indispensable role in NF-κB activation (Israël, 2000).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the canonical and non-canonical NF-κB signaling pathway. The canonical pathway is activated by a plethora of trigger/stimuli that includes different pathogens, stress signals, growth factors and inflammatory cytokine exposure which converges on the IKK complex. Activation of the NF-κB is tightly regulated due to the sequestration of the complex by IκBα in the cytosol. Phosphorylation of IκBα via IKK is a signal for its degradation, which is mediated by β-TrCP containing SCF-ubiquitin ligase complex. Freed dimers subsequently translocate to the nucleus where they bind to κB elements that controls the transcriptions of a variety of genes, which includes genes responsible for cytokine, chemokines, cell survival and proliferation. The non-canonical NF-κB pathway is dependent on the phosphorylation-induced p100 processing triggered by signaling from a subset of TNFR members. This pathway is reliant on NIK and IKKα, but not on the trimeric IKK complex, and mediates the activation of RelB/p52 complex. The detailed pathway is described in text.

The IKK signalosome complex is a multi-subunit complex comprising of three distinctive subunits IKK-α, IKK-β, and IKK-γ (Figure 1). IKK-α and IKK-β form the catalytic center of the complex that exist either as a homo- or heterodimers, and with IKK-γ or NEMO (NF-κB essential modulator) forms the regulatory subunit, that acts as a docking site for the other signaling protein or IKK kinase (Rothwarf et al., 1998; Israël, 2000; Santoro et al., 2003). Integrity of IKK-γ is required for NF-κB activation. The mechanism of NF-κB activation is well orchestrated by serine phosphorylation of IKK-β subunit that is mediated by upstream kinases or through trans autophosphorylation of IKK subunits. Aautophosphorylation of IKK-β at the C-terminal serine cluster prevents prolonged NF-κB activation, thus acting as a negative feedback regulation (Delhase et al., 1999). The phosphorylation of IκB at N-terminal Ser 32 and Ser 36 (Karin and Ben-Neriah, 2000), mediated by IKK, leads to proteasomal degradation of the inhibitory subunit by 26S proteasome, resulting in NF-κB activation. βeta-transducin repeat- containing protein (β-TrCP) containing SCF (Skp1, Cdc53/cullin, and F box protein) ubiquitin ligase mediates the ubiquitination of phosphorylated IκB at Lys21 and Lys22 (Liang et al., 2004). In general, bacterial and viral infections triggered NF-κB activation is mediated by IKK-β. In contrast, a unique regulatory mechanism of the NF-κB pathway via the non-canonical arm predominantly targets activation of RelB/p52 subunit (Senftleben et al., 2001). Unlike the canonical pathway that responds to signals elicited by diverse receptors, the non-canonical pathway is targeted by a specific set of receptors (Sun and Harhaj, 2006). The best-characterized non-canonical NF-κB receptors include a subset of the TNFR superfamily members, including B-cell-activating factor belonging to the TNF family receptor (BAFFR; Claudio et al., 2002), lymphotoxin β-receptor (LTβR; (Dejardin et al., 2002), receptor activator for NF-κB (RANK; (Novack et al., 2003) and CD40 (Coope et al., 2002). In resting cells, RelB associates with NF-κB2 p100 polypeptide in the cytoplasm whose C-terminal ankyrin repeat undergoes degradation upon stimulation, releasing RelB-p52 dimers that translocate to the nucleus (Senftleben et al., 2001; Figure 1). Activation of this process is mediated by the IKK-α subunit, unlike the canonical NF-κB pathway which is primarily mediated by IKK-β. NIK is a central signaling component of the non-canonical pathway, which integrates signals from a subset of TNF receptor family members and activates a downstream kinase, IKKα, for triggering phosphorylation of p100 and its processing (Sun, 2011). Following activation, NF-κB translocates to the nucleus where it binds to DNA consensus sequence 5’-GGGACTTTCC-3’ (κB elements; Figure 1). NF-κB transcriptional activity is greatly enhanced by the phosphorylation of RelA by protein kinase A (PKA) that facilitates its association with the transcriptional coactivator CBP/p300 (Zhong et al., 1998). Importantly, acetylation of NF-κB was described as an additional regulatory mechanism for the activity of NF-κB (Chen et al., 2001).

NF-κB Regulation During Entamoeba histolytica Infection

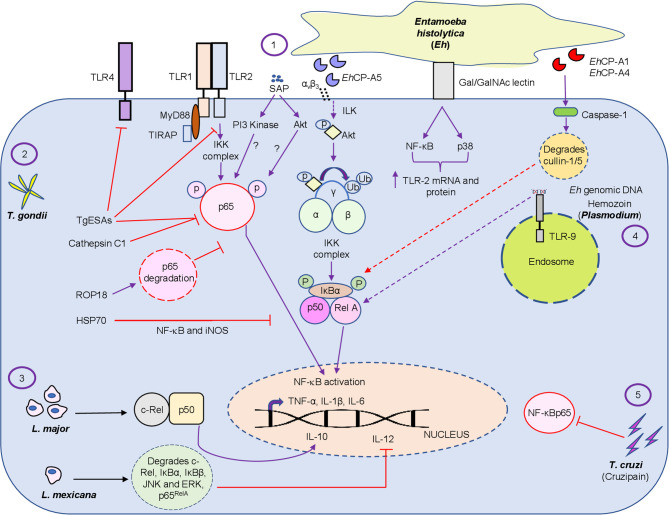

E. histolytica (Eh) is an extracellular protozoan parasite and the causative agent of the disease amebiasis. Eh infects ~10% of the world population leading to 100,000 deaths/year (Stanley Jr, 2003). Though the disease is a concern worldwide, it is more prevalent in developing countries due to poor sanitation and nutrition (Mahmud et al., 2013). Although multiple factors contribute to disease pathogenesis, it is primarily determined by the efficacy and quality of the host immune response. For undetermined reasons, ~10% of Eh infection sporadically breaches innate mucosal barriers and invades the lamina propria. Eh disease pathogenesis is the result of the dynamic interaction of Eh with different components of the immune system and the expression of Eh virulence factors (Faust and Guillen, 2012; Verkerke et al., 2012; Marie and Petri Jr, 2014; Ghosh et al., 2019; Rosales, 2021). When Eh breaches the innate protective mucus barrier (Moncada et al., 2003; Mortimer and Chadee, 2010; Begum et al., 2020a) it comes into direct contact with mucosal epithelial cells and subepithelial macrophages and dendritic cells. Here, NF-κB signaling from epithelial and immune cells plays an indispensable role in shaping the pro-inflammatory landscape during infection (Kammanadiminti and Chadee, 2006; Kammanadiminti et al., 2007; Hou et al., 2010; Begum et al., 2020b). Eh components or live Eh in direct contact with epithelial cells or macrophages can modulate cellular functions. For example, Caco-2 and T84 human colonic epithelial cells cocultured with differentiated THP-1 macrophages for 24h, followed by stimulation with soluble amebic proteins (SAP) augmented Hsp 27 and 72. In this interaction, Hsp27 played an important role in inhibiting the NF-κB pathway because of its association with the IKK complex while Hsp72 inhibited apoptosis (Kammanadiminti and Chadee, 2006). This may in part, explain why colonic inflammation is not robust in the majority of individuals with intestinal amebiasis. This interaction is not unique to Eh as the inhibitory effects of heat shock proteins (Hsp) on NF-κB activation was shown in T-cells (Guzhova et al., 1997). Curiously, the IKK complex seem to be a potential target for Hsp inhibition of the NF-κB pathway (Yoo et al., 2000; Kohn et al., 2002). In another study (Kammanadiminti et al., 2007), Eh secreted proteins and SAP induced the expression of the NF-κB dependent cytokine, monocyte chemotactic protein (MCP) from T84, LS174T and Caco-2 epithelial cells. Mechanistically, SAP-induced the phosphorylation of NF-κB p65 subunit and enhanced transcriptional activity that was dependent on phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3 kinase) ( Figure 2 and Table 1 ). Inhibition of PI3 kinase abrogated the activation of Akt, p65, and MCP-1 mRNA induction. What remains unclear from these studies is whether PI3 kinase or Akt directly phosphorylates the p65 subunit in response to ameba components.

Figure 2.

Diagrammatic representation of the intriguing relationship between protozoan parasite virulence factors and the NF-κB pathway. The figure represents the regulation of the NF-κB pathway by the extracellular protozoan parasite Eh and its virulence factors, which includes SAP, EhCP-A1, EhCP -A4 and Eh genomic DNA (1) and by different intracellular protozoan parasites T. gondii virulence factors, namely, TgESAs, Cathepsin C1, ROP18 and HSP70 (2), L. major/Mexicana live infection (3), Plasmodium pathogenic component hemozoin (4) and T. cruzi secreted lysosomal peptidase cruzipain (5) at different levels by modulating the inflammatory response during host-pathogen interaction. Virulence factors and live infection modulates NF-κB signaling at multiple levels. Both intracellular and extracellular protozoan parasites differentially modulate the NF-κB pathway. Note, purple color arrows indicate activation/promotion while red color arrows depict inhibition. The detailed mechanisms of action of the virulence factors are described in the text.

Table 1.

Differential regulation of the NF-κB pathway by protozoan parasites.

| Parasite (Disease) | Pathogen component | Target | Result/outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. histolytica (Amebiasis) | SAP | IKK Complex | NF-κB inhibition | (Kammanadiminti and Chadee, 2006) |

| Phosphorylation of p65 | MCP-1 cytokine induction | (Kammanadiminti et al., 2007) | ||

| Calpain | Degradation of p65, STAT3/5 | Cell death | (Kim et al., 2014) | |

| Gal/GalNAc-lectin | NF-κB and MAPK activation | TLR-2 m-RNA and protein expression | (Kammanadiminti et al., 2004) | |

| EhCP-A5 | IKK activation and IκB phosphorylation | Enhanced pro-inflammatory response | (Hou et al., 2010) | |

| LPPG | TLR-2 and-4 activation | IL-12p40, TNF-α, IL-10, and IL-8 release | (Maldonado‐Bernal et al., 2005) | |

| Eh genomic DNA | TLR9 | NF-κB and MAPK activation | (Ivory et al., 2008) | |

| Live Eh | Cytoskeletal-associated proteins talin, Pyk2 and paxillin | NLRP3 inflammasome activation | (St-Pierre et al., 2017) | |

| Toxoplasma gondii (Toxoplasmosis) | TgESAs | Inhibits NF-κBp65 and TLR2/4 activation | Up-regulates IL-10 and TGF-β | (Wang et al., 2017) |

| ROP18 | p65 degradation | Aborted NF-κB signaling | (Du et al., 2014) | |

| ROP16 | Inhibits STAT3/6 and NF-κB transcription | down-regulates TLR induced cytokines | (Saeij et al., 2007) | |

| Cathepsin C1 | Inhibits p65 phosphorylation | Decrease TNF-α, IL-12, IL-6, IL-8, IL-1 production | (Liu et al., 2019) | |

| HSP70 | Inhibits iNOS and NF-κB | Decrease host parasiticidal mechanism | (Dobbin et al., 2002) | |

| Plasmodium (Malaria) | GPI | NF-κB/c-rel | iNOS expression | (Tachado et al., 1996) |

| Hemozoin | TLR-9 mediated NF-κB activation | Up-regulates pro-IL-1β and NLRP3 activation | (Coban et al., 2005; Parroche et al., 2007; Baccarella et al., 2013) | |

| Trypanosoma cruzi (Chagas) | GPI | Activates TLR2/MyD88, MAPK and NF-κB | Induction of IL-12, TNF-α, and NO | (Campos et al., 2001) |

| Cruzipain | Interferes NF-κBp65 signaling | Hinders macrophage activation | (Watanabe Costa et al., 2016) | |

| Leishmania (Leishmaniasis) | L. major infection | Selectively translocate c-Rel/p50 | Induces IL-10 expression | (Guizani-Tabbane et al., 2004) |

| gp63 | Cleaves NF-κBp65 RelA into p35RelA | Induces expression of MCP-1, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, MIP-2 | (Gregory et al., 2008) | |

| L. mexicana infection | Degrades entire NF-κB pathway (p65RelA, c-Rel, IκBα, IκBβ, JNK and ERK) | Inhibits IL-12 production | (Cameron et al., 2004) |

In vivo, the NF-κB p50 subunit played a protective role, as Eh challenged C57BL/6 and 129/Sv mice with targeted deletion of the p50 subunit were more susceptible to Eh (Cho et al., 2010). A unique mechanism of epithelial cell death was also explored during Eh infection (Kim et al., 2014). Curiously, calpain, a calcium-dependent cysteine protease, induced protein degradation of pro-survival transcription factors, including, NF-κB p65, STAT3 and STAT5 that promoted cell death in response to Eh (Kim et al., 2014; Table 1). Eh invasion of the colonic mucosa leads to a pro-inflammatory cytokine burst and recruitment of different immune cells, which includes neutrophils and macrophages to the site of infection (Seydel et al., 1997; Mortimer and Chadee, 2010; Nakada-Tsukui and Nozaki, 2016).

Eh deploy an arsenal of virulence factors, which includes amoebapore, galactose/N-acetyl-D-galactosamine (Gal/GalNAc) lectin (Gal-lectin), cysteine proteinases and prostaglandin E2 (Moonah et al., 2013; Marie and Petri Jr, 2014). Eh Gal-lectin is a major surface molecule that mediates the binding of Eh to host cells and to Gal and GalNAc colonic MUC2 mucin glycans (Chadee et al., 1987; Petri et al., 1987). Macrophages are innate immune cells that are instrumental in mounting a robust pro-inflammatory response. Stimulation of macrophages with native Gal-lectin activated NF-κB and MAP kinase signaling pathway that culminated in the induction of TLR-2 mRNA and surface expression (Kammanadiminti et al., 2004; Figure 2 and Table 1). The Eh Gal-lectin, a vaccine candidate for amebiasis, induces dendritic cell (DC) maturation and activation via MAPK and NF-κB pathway leading to Th1 cytokine production (Ivory and Chadee, 2007). Amongst the different virulence factors, cysteine proteinases play a major role in the pathogenicity of amebiasis (Ankri et al., 1999; Tillack et al., 2006; Meléndez-López et al., 2007). EhCP-A1, EhCP-A2 and EhCP-A5 are highly expressed cysteine proteinases in axenically cultured Eh (Bruchhaus et al., 1996; Tillack et al., 2007). The cysteine proteinases repertoire is expressed spatially: EhCP-A1 is confined to intracellular vesicles while EhCP-A5 is expressed on the cell surface, and EhCP-A2 is limited to the inner and outer cell membrane (Jacobs et al., 1998; Que et al., 2002; Meléndez-López et al., 2007). Pro-mature cysteine proteinase 5 (PCP5) is a major virulence factor of Eh that is secreted and/or present on the surface of ameba, binds via its RGD motif to αvβ3 integrins on colonic cells to trigger NF-κB mediated pro-inflammatory responses (Hou et al., 2010). PCP5-RGD binding to αvβ3 integrins activated integrin-linked kinase (ILK) that mediated the phosphorylation of Akt-473 that subsequently bound and induced IKK activation via ubiquitination of NEMO that phosphorylates IκBα triggering pro-inflammatory responses (Hou et al., 2010; Figure 2). The Gal-lectin and EhCP-A5 together also play a central role in contact-dependent activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in macrophages for high output IL-1β secretion (Mortimer et al., 2014; Mortimer et al., 2015). In this interaction, Gal-lectin activates the NF-κB pathway for transcriptional activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome to stimulate TNF-α release (Mortimer et al., 2014). During primary Eh infection, macrophage secreted TNF-α has a detrimental outcome leading to increased diarrheal disease. However, naïve macrophages that are primed with TNF-α and IFN-γ produce high levels of nitric oxide (NO) that kills Eh (Lin et al., 1994; Seguin et al., 1995; Haque et al., 2007). Several Eh components can bind macrophage and epithelial TLR to activate the NF-κB pathway to induce a raging pro-inflammatory response. Mouse macrophages stimulated with Eh genomic DNA signaled via TLR9 to activate NF-κB and MAPK that was dependent on MyD88 (Ivory et al., 2008; Figure 2 and Table 1 ). Lipopeptidophosphoglycan (LPPG), a Eh associated molecular pattern, activated NF-κB via TLR-2 and -4 resulting in the release of IL-12p40, TNF-α, IL-10, and IL-8 from human monocytes (Table 1). Mouse macrophages lacking TLR-2 (TLR-2-/- ) or deficient in TLR-4 (TLR-4d/d ) were unresponsive to LPPG stimulation (Maldonado‐Bernal et al., 2005). Eh induced inflammation is characterized by the infiltration of neutrophils, which have been implicated in host defense against amebiasis. Interestingly, Eh activates neutrophils to induce extracellular traps that was dependent on the NF-κB pathway (Fonseca et al., 2018). This suggests the if Eh can suppress the NF-κB pathway in neutrophils like it does in macrophages, it can ward off potent innate host defenses.

The forgoing discussion elegantly demonstrates that Eh and its components can manipulate the NF-κB pathway to elicit a florid pro-inflammatory response that may play a crucial role in Eh invasion and shape the outcome of disease. While detailed experimentations have uncovered many unanswered questions during Eh-host interaction, there are many questions that still need to be addressed. For instance, which specific NF-κB protein subunits play a regulatory role during Eh pathogenesis and what will be the outcome of NF-κB signaling from different cell types upon contact with Eh. In this regard we recently (Chadha et al., 2021) uncovered a novel role for inflammatory caspase-1 that intersected NF-κB signaling during Eh-macrophage contact. In this interaction, Eh-induced caspase-1 activation rapidly degraded cullin-1/5 proteins, a central scaffolding component of multi-subunit E3s ligase that attenuated NF-κB signaling (Figure 2) inhibiting TNF-α production. Cullin-1/5 degradation was also observed from colonic epithelial cells following live Eh inoculated in proximal colonic loops of mice as a short-term infection model. Cullin-1/5 degradation was dependent on Eh surface cysteine proteinases EhCP-A1 and EhCP-A4, but not on EhCP-A5, based on pharmacological inhibition of the cysteine proteinases and EhCP-A5 deficient parasites. These findings highlight that Eh suppression of NF-κB signaling induces a predominant NLRP3 dependent IL-1β pro-inflammatory response that may contribute to disease pathogenesis. Eh in contact with macrophages is also known to induce the degradation of cytoskeletal-associated proteins talin, Pyk2 and paxillin that activated the NLRP3 inflammasome by an unknown mechanism (St-Pierre et al., 2017; Table 1). These findings suggest that Eh in contact with host cells at the intercellular junction uses several Eh ligands that couples to multiple putative receptors to activate inflammatory caspases and the NF-κB pathway that regulates pro-inflammatory responses. We are now beginning to decipher some of the salient features that regulates Eh-host parasite interaction in epithelial cells, macrophages and neutrophils by teasing out defined pathways that may be beneficial to the host and/or parasite in disease pathogenesis.

NF-κB Pathway Modulation During Toxoplasma gondii Infection

Unlike extracellular Eh, intracellular protozoan parasites have devised unique ways to modulate the innate immune response via inside-out signaling by manipulating the NF-κB pathway. T. gondii, the causative agent of toxoplasmosis, is an obligatory intracellular protozoan parasite that can infect all nucleated cells of warm-blooded animals (Hou et al., 2019; Li et al., 2019; de Faria Junior et al., 2021) including wild, domesticated and companion animals (Dubey et al., 2012). It infects about one-third of the world’s human population (Sasai et al., 2018). Infection in immunocompromised individuals often leads to symptomatic and lethal toxoplasmosis (Tenter et al., 2000). Humans and other animals become infected due to consumption of under-cooked meat of infected animals or by ingesting water or food contaminated with oocysts (Jones et al., 2005; Dubey and Jones, 2008). T. gondii has three infectious stages known as tachyzoite, bradyzoite and sporozoites (within oocysts) (Dubey et al., 1998). Mouse models identified three different strains of T. gondii called type I, type II, and type III with different virulence factors. Amongst the three strains, type I is the most virulent strain, while type II and type III are avirulent (Howe et al., 1996; Mordue et al., 2001).

To counteract the host immune responses, Toxoplasma deploys multiple strategies to subvert the NF-κB signaling pathway. Infection of bone marrow-macrophages with RH tachyzoites (RH strain of T. gondii, which is a type I representative strain) repressed NF-κB activation by inhibiting nuclear localization of p65 or c-Rel, while in-vivo infection activated the NF-κB pathway (Shapira et al., 2002). While the pathogen displays a repertoire of virulence factors, some play a crucial role in establishing the infection via immunomodulation of different immune cells. T. gondii excretory/secretory antigens (TgESAs), a virulence factor, inhibited nuclear translocation of NF-κBp65 and TLR-2 and -4 activation from LPS-stimulated Ana-1 murine macrophage that upregulated the anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10 and TGF-β and downregulated the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β (Wang et al., 2017; Figure 2 and Table 1). One of the strategies used by the parasite to subvert immune responses, is degradation of host proteins and transcription factors essential for regulating the immune response. T. gondii releases its protein into the host from organelles called dense granules and rhoptries (ROPs), thus manipulating host cell and their transcriptional responses (Lima and Lodoen, 2019; Tuladhar et al., 2019). ROP18, an effector of type I strains, is a serine/threonine kinase that modulates the phosphorylation of host proteins to circumvent cell signaling pathways. Surprisingly, ROP18 induced the phosphorylation of p65 at Ser-468 that led to ubiquitin-dependent degradation of p65 culminating in aborted NF-κB signaling, thus conferring a survival advantage (Du et al., 2014; Figure 2 and Table 1). Another protein ROP16, a putative protein kinase, suppressed IL-12 responses in infected macrophages stimulated with TLR agonist (Saeij et al., 2007) and inhibited NF-κB transcriptional activity (Rosowski et al., 2011), possibly due to the activation of STAT3/6 (Saeij et al., 2007) that downregulated TLR-induced cytokine production (Table 1). In contrast, T. gondii strains that express dense granule protein GRA15 directly activates NF-κB through a MyD88-independent mechanism (Melo et al., 2011). Recently (Liu et al., 2019), T. gondii cathepsin C1 (CPC1), a member of the GRA (dense granule) protein family, was shown to inhibit the phosphorylation of p65 subsequently leading to decreased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-12, IL-6, IL-8 and IL-1 (Figure 2 and Table 1). CPC1 inhibited NF-κB activation through positive regulation of HIF (hypoxia-inducible factor)-1α/EPO (erythropoietin) axis (Liu et al., 2019). While several studies have indicated the involvement of the NF-κB pathway during T. gondii infection, it seems to be cell-specific regulation. Heat shock protein 70 (HSP70) of T. gondii inhibited parasiticidal activity by inhibiting iNOS, and NF-κB activation from RAW 264.7 and splenocytes, respectively (Dobbin et al., 2002; Figure 2 and Table 1). Surprisingly, T. gondii infected macrophage up-regulated the phosphorylation and degradation of IκB and blocked the translocation of NF-κB by inhibiting the phosphorylation of p65/RelA (Shapira et al., 2005) leading to aborted pro-inflammatory cytokine production (Butcher et al., 2001; Shapira et al., 2002). While these results are well documented in murine macrophages it is still debatable if a similar mechanism occurs in murine fibroblasts (Shapira et al., 2002; Molestina et al., 2003). LPS induced IL-1β production inhibition from primary human neutrophils following type 1 strain infection was associated with inhibition of NF-κB. Although neutrophils infected with T. gondii aborted NF-κB signaling via reduced IκBα degradation and p65/RelA phosphorylation, it also showed marked reduction in transcripts for NLRP3 inflammasome sensor and IL-1β (Lima et al., 2018). To assess the importance of NF-κB during the infection, mice deficient in specific genes belonging to the NF-κB pathway have been assessed. Mice lacking RelB succumb to acute infection, due to inability to produce IFN-γ indicating an indispensable role of RelB in conferring resistance to T. gondii infection (Caamaño et al., 1999). During chronic infection, NF-κB2 -/- mice have higher mortality when compared to wild-type (WT) mice due to global T-cell loss and apoptosis (Franzoso et al., 1998). Previous studies have shown altered microRNA expression profile by Apicomplexan parasites (Deng et al., 2004; McDonald et al., 2013; Hou et al., 2019) indicating the involvement of microRNA during infections. T. gondii infection perturbed the signaling pathways responsible for generating host defense responses (Hakimi and Ménard, 2010) by modulating the expression of host microRNAs, which contributes to efficient parasite replication (Cong et al., 2017). In agreement with these observations, T. gondii attenuated the NF-κB pathway by inducing miR-146a in the host (Taganov et al., 2006). STAT3 and NF-κB activation in response to T. gondii up-regulated the expression of miRNAs miR-125b-2, miR-30c-1, miR-17-92 and miR-23b-27b-24-1 (Cai et al., 2013). Taken together, these observations suggest that T. gondii exploits the NF-κB pathway for successful replication and to evade cell mediated immunity.

Role of NF-κB in Other Protozoan Parasites

As NF-κB signaling is crucial for mounting an immediate immune response against invading pathogens, its manipulation has been described at multiple levels in response to several protozoan parasites. Plasmodium is the etiologic agent of the disease malaria. According to the WHO report 2015, it infects over 200 million people annually and kills over 500,000 patients a year (World Health Organization (WHO, 2016). Glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) of plasmodium activates macrophages and endothelial cells inducible NO synthase expression that involves NF-κB/c-rel (Tachado et al., 1996; Table 1 ). Hemozoin, a malarial pigment, binds to TLR9 and activates NF-κB and the NLRP3 inflammasome to increase the levels of pro-IL-1β (Coban et al., 2005; Parroche et al., 2007; Baccarella et al., 2013; Figure 2 and Table 1 ). A recent study (Toda et al., 2020) demonstrated a role for plasma-derived extracellular vesicles (EVs) from P. vivax patients (PvEVs) that activated NF-κB translocation from human spleen fibroblasts (hSFs), which up-regulated the levels of ICAM-1 that resulted in specific adhesion properties of reticulocytes (from infected patients) to hSFs (Toda et al., 2020). Trypanosoma cruzi the causative agent of Chagas disease, infects over 5 million people across the globe and kills thousands of people each year (Pérez-Molina and Molina, 2018). Cytokines released by immune cells play a decisive role in disease pathogenesis and invasion by infectious agent. The Y strain of T. cruzi was shown to activate NF-κB via the TNF pathway that increased invasion of non-professional phagocytic epithelial cells demonstrating a negative role for NF-κB activation favoring the parasite (Pinto et al., 2011). T. cruzi GPI, a pathogen-associated molecular pattern, is recognized by TLR-2, which stimulates the TLR-2/Myd88 pathway, MAPK and NF-κB transcription factor activation (Campos et al., 2001; Takeda and Akira, 2005; Table 1). In contrast, cruzipain, a T. cruzi secreted lysosomal peptidase, hindered macrophage activation during the initial stages of infection by interfering with NF-κBp65 mediated signaling (Watanabe Costa et al., 2016; Figure 2 and Table 1). Leishmaniasis, caused by multiple Leishmania species, is responsible for an estimated 12 million infections across the globe and thousands of deaths per year (Lozano et al., 2012; Vos et al., 2016). Different Leishmania species differentially regulate the NF-κB pathway. For instance, L. major infected monocytes (primary and PMA-differentiated U937 cells) inhibited nuclear localization of p65RelA/p50 heterodimers, however, it selectively promoted the translocation of c-Rel/p50 heterodimers, which induced the anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10 (Guizani-Tabbane et al., 2004; Figure 2 and Table 1). Infection of murine-BMDM with L. mexicana amastigotes degraded the entire NF-κB pathway; degradation of p65RelA, c-Rel, the upstream kinases JNK and ERK and the inhibitors IκBα and IκBβ (Cameron et al., 2004; Figure 2 and Table 1). In contrast, another group showed a novel subversion mechanism, wherein Leishmania protease, gp63, in vitro cleaved NF-κB p65RelA that resulted in a fragment p35RelA that dimerized with p50, which induced gene expression of the chemokines MCP-1, MIP-1α, MIP-1β and MIP-2 (Gregory et al., 2008; Table 1). A comprehensive view of the regulation of the NF-κB pathway by protozoan parasites is listed in Table 1 and Figure 2 summarizes the differential regulation of the NF- κB pathway by different protozoan parasites and their virulence factors.

Conclusion and Future Direction

The immune system is armored with multiple receptors, which are recognized by invading pathogens culminating in gene expression associated with the development of an immune response. Parasite interaction with the innate immune response involves coupling though multiple receptors that activates the NF-κB pathway. From an evolution point of view, multiple strategies reflect the selective pressure this pathway has imposed on different pathogens, while in turn evolution of different pathogens have led to the diversification of this pathway (Tato and Hunter, 2002). From the forgoing discussion it is apparent that parasites deploy multiple ways to circumvent signaling via the NF-κB pathway. However, we know very little on the diverse array of parasite molecules and/or downstream signaling involved in NF-κB activation and inhibition by extracellular and intracellular protozoan parasites. NF-κB pathway diversification involves different protein subunits that form different hetero/homodimers (Gilmore, 2006). Intriguingly, different combination and permutation of these dimers have different functional consequence on gene expression responsible for immune activation/inhibition. At present, we still do not know which specific homo/heterodimer subunits are formed during contact and/or invasion by parasites, and what would be the functional consequence. The question that is still baffling and needs attention is, whether NF-κB activation by different parasites favors the host or the pathogen or both. The dichotomy in NF-κB activation and inhibition observed by extracellular and intracellular parasites, in part, may answer why intracellular parasites inhibit this pathway, while extracellular parasites activates it. It is essential to understand which specific NF-κB subunit play an indispensable role during parasitic infection and how different receptor sense these parasites in a cell-type specific manner. Understanding these pathways could provide a better appreciation on the complexity of the disease and thus, help to develop better therapeutic approach for parasitic infections.

Author Contributions

AC and KC conceived the review topic and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was funded by a Discovery Grant (RGPIN-2019-04136) from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and a project grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (PJT-407276) awarded to KC.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Andrews K. T., Fisher G., Skinner-Adams T. S. (2014). Drug Repurposing and Human Parasitic Protozoan Diseases. Int. J. Parasitol: Drugs Drug Resistance 4 (2), 95–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2014.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ankri S., Stolarsky T., Bracha R., Padilla-Vaca F., Mirelman D. (1999). Antisense Inhibition of Expression of Cysteine Proteinases Affects Entamoeba Histolytica-Induced Formation of Liver Abscess in Hamsters. Infection Immun. 67 (1), 421–422. doi: 10.1128/IAI.67.1.421-422.1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baccarella A., Fontana M. F., Chen E. C., Kim C. C. (2013). Toll-Like Receptor 7 Mediates Early Innate Immune Responses to Malaria. Infection Immun. 81 (12), 4431–4442. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00923-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baud V., Karin M. (2001). Signal Transduction by Tumor Necrosis Factor and its Relatives. Trends Cell Biol. 11 (9), 372–377. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(01)02064-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begum S., Gorman H., Chadha A., Chadee K. (2020. a). Role of Inflammasomes in Innate Host Defense Against Entamoeba Histolytica. J. Leukocyte Biol. 108 (3), 801–812. doi: 10.1002/JLB.3MR0420-465R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begum S., Moreau F., Coria A. L., Chadee K. (2020. b). Entamoeba Histolytica Stimulates the Alarmin Molecule HMGB1 From Macrophages to Amplify Innate Host Defenses. Mucosal Immunol. 13 (2), 344–356. doi: 10.1038/s41385-019-0233-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruchhaus I., Jacobs T., Leippe M., Tannich E. (1996). Entamoeba Histolytica and Entamoeba Dispar: Differences in Numbers and Expression of Cysteine Proteinase Genes. Mol. Microbiol. 22 (2), 255–263. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.00111.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher B. A., Kim L., Johnson P. F., Denkers E. Y. (2001). Toxoplasma Gondii Tachyzoites Inhibit Proinflammatory Cytokine Induction in Infected Macrophages by Preventing Nuclear Translocation of the Transcription Factor NF-κb. J. Immunol. 167 (4), 2193–2201. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.4.2193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caamaño J., Alexander J., Craig L., Bravo R., Hunter C. A. (1999). The NF-κb Family Member RelB is Required for Innate and Adaptive Immunity to Toxoplasma gondii. J. Immunol. 163 (8), 4453–4461 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y., Chen H., Jin L., You Y., Shen J. (2013). STAT3-Dependent Transactivation of miRNA Genes Following Toxoplasma Gondii Infection in Macrophage. Parasites Vectors 6 (1), 1–9. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron P., McGachy A., Anderson M., Paul A., Coombs G. H., Mottram J. C., et al. (2004). Inhibition of Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Macrophage IL-12 Production by Leishmania Mexicana Amastigotes: The Role of Cysteine Peptidases and the NF-κb Signaling Pathway. J. Immunol. 173 (5), 3297–3304. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.3297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos M. A., Almeida I. C., Takeuchi O., Akira S., Valente E. P., Procópio D. O., et al. (2001). Activation of Toll-Like Receptor-2 by Glycosylphosphatidylinositol Anchors From a Protozoan Parasite. J. Immunol. 167 (1), 416–423. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.1.416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso M. S., Reis-Cunha J. L., Bartholomeu D. C. (2016). Evasion of the Immune Response by Trypanosoma Cruzi During Acute Infection. Front. Immunol. 6, 659. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadee K., Petri W., Innes D., Ravdin J. (1987). Rat and Human Colonic Mucins Bind to and Inhibit Adherence Lectin of Entamoeba Histolytica. J. Clin. Invest. 80 (5), 1245–1254. doi: 10.1172/JCI113199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadha A., Moreau F., Wang S., Dufour A., Chadee K. (2021). Entamoeba histolytica Activation of Caspase-1 Degrades Cullin That Attenuates NF-κB Dependent Signaling From Macrophages. PLoS Pathogens. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L.-f., Fischle W., Verdin E., Greene W. C. (2001). Duration of Nuclear NF-κb Action Regulated by Reversible Acetylation. Science 293 (5535), 1653–1657. doi: 10.1126/science.1062374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G., Goeddel D. V. (2002). TNF-R1 Signaling: A Beautiful Pathway. Science 296 (5573), 1634–1635. doi: 10.1126/science.1071924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho K.-N., Becker S. M., Houpt E. R. (2010). The NF-κb P50 Subunit is Protective During Intestinal Entamoeba Histolytica Infection of 129 and C57BL/6 Mice. Infection Immun. 78 (4), 1475–1481. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00669-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claudio E., Brown K., Park S., Wang H., Siebenlist U. (2002). BAFF-Induced NEMO-Independent Processing of NF-κB2 in Maturing B Cells. Nat. Immunol. 3 (10), 958–965. doi: 10.1038/ni842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coban C., Ishii K. J., Kawai T., Hemmi H., Sato S., Uematsu S., et al. (2005). Toll-Like Receptor 9 Mediates Innate Immune Activation by the Malaria Pigment Hemozoin. J. Exp. Med. 201 (1), 19–25. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong W., Zhang X.-X., He J.-J., Li F.-C., Elsheikha H. M., Zhu X.-Q. (2017). Global miRNA Expression Profiling of Domestic Cat Livers Following Acute Toxoplasma Gondii Infection. Oncotarget 8 (15), 25599. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coope H., Atkinson P., Huhse B., Belich M., Janzen J., Holman M., et al. (2002). CD40 Regulates the Processing of NF-κb2 P100 to P52. EMBO J. 21 (20), 5375–5385. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Faria Junior G. M., Murata F. H. A., Lorenzi H. A., Castro B. B. P., Assoni L. C. P., Ayo C. M., et al. (2021). The Role of microRNAs in the Infection by T. Gondii in Humans. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 11, 1–11. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.670548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejardin E., Droin N. M., Delhase M., Haas E., Cao Y., Makris C., et al. (2002). The Lymphotoxin-β Receptor Induces Different Patterns of Gene Expression via Two NF-κb Pathways. Immunity 17 (4), 525–535. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(02)00423-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delhase M., Hayakawa M., Chen Y., Karin M. (1999). Positive and Negative Regulation of Iκb Kinase Activity Through Ikkβ Subunit Phosphorylation. Science 284 (5412), 309–313. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5412.309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng M., Lancto C. A., Abrahamsen M. S. (2004). Cryptosporidium Parvum Regulation of Human Epithelial Cell Gene Expression. Int. J. Parasitol. 34 (1), 73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2003.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon B., Parrington L., Cook A., Pintar K., Pollari F., Kelton D., et al. (2011). The Potential for Zoonotic Transmission of Giardia Duodenalis and Cryptosporidium Spp. From Beef and Dairy Cattle in Ontario, Canada. Veterinary Parasitol. 175 (1-2), 20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.09.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbin C. A., Smith N. C., Johnson A. M. (2002). Heat Shock Protein 70 is a Potential Virulence Factor in Murine Toxoplasma Infection via Immunomodulation of Host NF-κb and Nitric Oxide. J. Immunol. 169 (2), 958–965. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.2.958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorny P., Praet N., Deckers N., Gabriël S. (2009). Emerging Food-Borne Parasites. Veterinary Parasitol. 163 (3), 196–206. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.05.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du J., An R., Chen L., Shen Y., Chen Y., Cheng L., et al. (2014). Toxoplasma Gondii Virulence Factor ROP18 Inhibits the Host NF-κb Pathway by Promoting P65 Degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 289 (18), 12578–12592. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.544718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Dubey J., Jones J. (2008). Toxoplasma Gondii Infection in Humans and Animals in the United States. Int. J. Parasitol. 38 (11), 1257–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2008.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubey J., Lindsay D., Speer C. (1998). Structures of Toxoplasma Gondii Tachyzoites, Bradyzoites, and Sporozoites and Biology and Development of Tissue Cysts. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11 (2), 267–299. doi: 10.1128/CMR.11.2.267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubey J., Tiao N., Gebreyes W., Jones J. (2012). A Review of Toxoplasmosis in Humans and Animals in Ethiopia. Epidemiol. Infect. 140 (11), 1935–1938. doi: 10.1017/S0950268812001392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faust D. M., Guillen N. (2012). Virulence and Virulence Factors in Entamoeba Histolytica, the Agent of Human Amoebiasis. Microbes Infect. 14 (15), 1428–1441. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2012.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher S. M., Stark D., Harkness J., Ellis J. (2012). Enteric Protozoa in the Developed World: A Public Health Perspective. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 25 (3), 420–449. doi: 10.1128/CMR.05038-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca Z., Díaz-Godínez C., Mora N., Alemán O. R., Uribe-Querol E., Carrero J. C., et al. (2018). Entamoeba Histolytica Induce Signaling via Raf/MEK/ERK for Neutrophil Extracellular Trap (NET) Formation. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 8:226. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzoso G., Carlson L., Poljak L., Shores E. W., Epstein S., Leonardi A., et al. (1998). Mice Deficient in Nuclear Factor (NF)-κb/P52 Present With Defects in Humoral Responses, Germinal Center Reactions, and Splenic Microarchitecture. J. Exp. Med. 187 (2), 147–159. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.2.147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S., May M. J., Kopp E. B. (1998). NF-κb and Rel Proteins: Evolutionarily Conserved Mediators of Immune Responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 16 (1), 225–260. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S., Padalia J., Moonah S. (2019). Tissue Destruction Caused by Entamoeba Histolytica Parasite: Cell Death, Inflammation, Invasion, and the Gut Microbiome. Curr. Clin. Microbiol. Rep. 6 (1), 51–57. doi: 10.1007/s40588-019-0113-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore T. D. (2006). Introduction to NF-κ B: Players, Pathways, Perspectives. Oncogene 25 (51), 6680–6684. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory D. J., Godbout M., Contreras I., Forget G., Olivier M. (2008). A Novel Form of NF-κb is Induced by Leishmania Infection: Involvement in Macrophage Gene Expression. Eur. J. Immunol. 38 (4), 1071–1081. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guizani-Tabbane L., Ben-Aissa K., Belghith M., Sassi A., Dellagi K. (2004). Leishmania Major Amastigotes Induce P50/C-Rel NF-κβ Transcription Factor in Human Macrophages: Involvement in Cytokine Synthesis. Infect. Immun. 72 (5), 2582–2589. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.5.2582-2589.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta G., Oghumu S., Satoskar A. R. (2013). Mechanisms of Immune Evasion in Leishmaniasis. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 82, 155–184. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-407679-2.00005-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzhova I. V., Darieva Z. A., Melo A. R., Margulis B. A. (1997). Major Stress Protein Hsp70 Interacts With NF-kB Regulatory Complex in Human T-Lymphoma Cells. Cell Stress Chaperones 2 (2), 132. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakimi M.-A., Ménard R. (2010). Do Apicomplexan Parasites Hijack the Host Cell microRNA Pathway for Their Intracellular Development? F1000 Biol. Rep. 2. doi: 10.3410/B2-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haque R., Mondal D., Shu J., Roy S., Kabir M., Davis A. N., et al. (2007). Correlation of Interferon-γ Production by Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells With Childhood Malnutrition and Susceptibility to Amebiasis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hygiene 76 (2), 340–344. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2007.76.340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heussler V. T., Küenzi P., Rottenberg S. (2001). Inhibition of Apoptosis by Intracellular Protozoan Parasites. Int. J. Parasitol. 31 (11), 1166–1176. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(01)00271-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn D. (2014). Antigenic Variation in African Trypanosomes. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol 195 (2), 123–129. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2014.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Z., Liu D., Su S., Wang L., Zhao Z., Ma Y., et al. (2019). Comparison of Splenocyte microRNA Expression Profiles of Pigs During Acute and Chronic Toxoplasmosis. BMC Genomics 20 (1), 1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12864-019-5458-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Y., Mortimer L., Chadee K. (2010). Entamoeba Histolytica Cysteine Proteinase 5 Binds Integrin on Colonic Cells and Stimulates Nfκb-Mediated Pro-Inflammatory Responses. J. Biol. Chem. 285 (46), 35497–35504. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.066035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe D. K., Summers B. C., Sibley L. D. (1996). Acute Virulence in Mice is Associated With Markers on Chromosome VIII in Toxoplasma gondii. Infect. Immun. 64 (12), 5193–5198. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.5193-5198.1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israël A. (2000). The IKK Complex: An Integrator of All Signals That Activate NF-κb? Trends Cell Biol. 10 (4), 129–133. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(00)01729-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivory C. P., Chadee K. (2007). Activation of Dendritic Cells by the Gal-Lectin of Entamoeba Histolytica Drives Th1 Responses In Vitro and In Vivo. Eur. J. Immunol. 37 (2), 385–394. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivory C. P., Prystajecky M., Jobin C., Chadee K. (2008). Toll-Like Receptor 9-Dependent Macrophage Activation by Entamoeba Histolytica DNA. Infection Immun. 76 (1), 289–297. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01217-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs T., Bruchhaus I., Dandekar T., Tannich E., Leippe M. (1998). Isolation and Molecular Characterization of a Surface-Bound Proteinase of Entamoeba Histolytica. Mol. Microbiol. 27 (2), 269–276. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00662.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones J. L., Lopez B., Mury M. A., Wilson M., Klein R., Luby S., et al. (2005). Toxoplasma Gondii Infection in Rural Guatemalan Children. Am. J. Trop. Med. hygiene 72 (3), 295–300. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2005.72.295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kammanadiminti S. J., Chadee K. (2006). Suppression of NF-κb Activation by Entamoeba Histolytica in Intestinal Epithelial Cells is Mediated by Heat Shock Protein 27. J. Biol. Chem. 281 (36), 26112–26120. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601988200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kammanadiminti S. J., Dey I., Chadee K. (2007). Induction of Monocyte Chemotactic Protein 1 in Colonic Epithelial Cells by Entamoeba Histolytica is Mediated via the Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase/P65 Pathway. Infect. Immun. 75 (4), 1765–1770. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01442-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kammanadiminti S. J., Mann B. J., Dutil L., Chadee K. (2004). Regulation of Toll-Like Receptor-2 Expression by the Gal-Lectin of Entamoeba Histolytica. FASEB J. 18 (1), 155–157. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0578fje [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin M., Ben-Neriah Y. (2000). Phosphorylation Meets Ubiquitination: The Control of NF-κb Activity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 18 (1), 621–663. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin M., Cao Y., Greten F. R., Li Z.-W. (2002). NF-κb in Cancer: From Innocent Bystander to Major Culprit. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2 (4), 301–310. doi: 10.1038/nrc780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly P. (2013). Protozoal Gastrointestinal Infections. Medicine 41 (12), 705–708. doi: 10.1016/j.mpmed.2013.09.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K. A., Min A., Lee Y. A., Shin M. H. (2014). Degradation of the Transcription Factors NF-κb, STAT3, and STAT5 is Involved in Entamoeba Histolytica-Induced Cell Death in Caco-2 Colonic Epithelial Cells. Korean J. Parasitol 52 (5), 459. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2014.52.5.459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn G., Wong H. R., Bshesh K., Zhao B., Vasi N., Denenberg A., et al. (2002). Heat Shock Inhibits Tnf-Induced ICAM-1 Expression in Human Endothelial Cells via I Kappa Kinase Inhibition. Shock 17 (2), 91–97. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200202000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyes S., Horrocks P., Newbold C. (2001). Antigenic Variation at the Infected Red Cell Surface in Malaria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 55, 673. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Negrate G. (2012). Subversion of Innate Immune Responses by Bacterial Hindrance of NF-κb Pathway. Cell. Microbiol. 14 (2), 155–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y., Zhou Y., Shen P. (2004). NF-kappaB and its Regulation on the Immune System. Cell Mol. Immunol. 1 (5), 343–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima T. S., Gov L., Lodoen M. B. (2018). Evasion of Human Neutrophil-Mediated Host Defense During Toxoplasma Gondii Infection. MBio 9 (1), e02027–e02017. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02027-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima T. S., Lodoen M. B. (2019). Mechanisms of Human Innate Immune Evasion by Toxoplasma Gondii. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 9:103. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2019.00103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J.-Y., Seguin R., Keller K., Chadee K. (1994). Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha Augments Nitric Oxide-Dependent Macrophage Cytotoxicity Against Entamoeba Histolytica by Enhanced Expression of the Nitric Oxide Synthase Gene. Infect. Immun. 62 (5), 1534–1541. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.5.1534-1541.1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Zou X., Ou M., Ye X., Zhang B., Wu T., et al. (2019). Toxoplasma Gondii Cathepsin C1 Inhibits NF-κb Signalling Through the Positive Regulation of the HIF-1α/EPO Axis. Acta Tropica 195, 35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2019.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Verma I. M. (2002). NF-κb Regulation in the Immune System. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2 (10), 725–734. doi: 10.1038/nri910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Yang J., Wang L., Du F., Zhao J., Fang R. (2019). Expression Profile of microRNAs in Porcine Alveolar Macrophages After Toxoplasma Gondii Infection. Parasites Vectors 12 (1), 1–11. doi: 10.1186/s13071-019-3297-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozano R., Naghavi M., Foreman K., Lim S., Shibuya K., Aboyans V., et al. (2012). Global and Regional Mortality From 235 Causes of Death for 20 Age Groups in 1990 and 2010: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 380 (9859), 2095–2128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmud R., Ibrahim J., Moktar N., Anuar T.-S. (2013). “Entamoeba Histolytica in Southeast Asia,” in Parasites and Their Vectors. Eds. Lim Y., Vythilingam I. (Vienna: Springer; ), 103–129. [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado-Bernal C., Kirschning C., Rosenstein Y., Rocha L., Rios-Sarabia N., Espinosa-Cantellano M., et al. (2005). The Innate Immune Response to Entamoeba Histolytica Lipopeptidophosphoglycan is Mediated by Toll-Like Receptors 2 and 4. Parasite Immunol. 27 (4), 127–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2005.00754.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marie C., Petri J. W. A. (2014). Regulation of Virulence of Entamoeba histolytica. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 68, 493–520. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-091313-103550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald V., Korbel D., Barakat F., Choudhry N., Petry F. (2013). Innate Immune Responses Against Cryptosporidium Parvum Infection. Parasite Immunol. 35 (2), 55–64. doi: 10.1111/pim.12020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meléndez-López S. G., Herdman S., Hirata K., Choi M.-H., Choe Y., Craik C., et al. (2007). Use of Recombinant Entamoeba Histolytica Cysteine Proteinase 1 to Identify a Potent Inhibitor of Amebic Invasion in a Human Colonic Model. Eukaryotic Cell 6 (7), 1130–1136. doi: 10.1128/EC.00094-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo M. B., Jensen K. D., Saeij J. P. (2011). Toxoplasma Gondii Effectors are Master Regulators of the Inflammatory Response. Trends Parasitol. 27 (11), 487–495. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2011.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molestina R. E., Payne T. M., Coppens I., Sinai A. P. (2003). Activation of NF-κb by Toxoplasma Gondii Correlates With Increased Expression of Antiapoptotic Genes and Localization of Phosphorylated Iκb to the Parasitophorous Vacuole Membrane. J. Cell Sci. 116 (21), 4359–4371. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moncada D. M., Kammanadiminti S. J., Chadee K. (2003). Mucin and Toll-Like Receptors in Host Defense Against Intestinal Parasites. Trends Parasitol. 19 (7), 305–311. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4922(03)00122-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monzote L., Siddiq A. (2011). Drug Development to Protozoan Diseases. Open Medicinal Chem. J. 5:1. doi: 10.2174/1874104501105010001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moonah S. N., Jiang N. M., Petri J. W. A. (2013). Host Immune Response to Intestinal Amebiasis. PloS Pathog. 9 (8), e1003489. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mordue D. G., Monroy F., La Regina M., Dinarello C. A., Sibley L. D. (2001). Acute Toxoplasmosis Leads to Lethal Overproduction of Th1 Cytokines. J. Immunol. 167 (8), 4574–4584. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.8.4574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer L., Chadee K. (2010). The Immunopathogenesis of Entamoeba Histolytica. Exp. Parasitol. 126 (3), 366–380. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2010.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer L., Moreau F., Cornick S., Chadee K. (2014). Gal-Lectin-Dependent Contact Activates the Inflammasome by Invasive Entamoeba histolytica. Mucosal Immunol. 4, 829–841. doi: 10.1038/mi.2013.100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer L., Moreau F., Cornick S., Chadee K. (2015). The NLRP3 Inflammasome Is a Pathogen Sensor for Invasive Entamoeba histolytica via Activation of α5β1 Integrin at the Macrophage-Amebae Intercellular Junction. PLoS Pathog. 11 (5), e1004887. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakada-Tsukui K., Nozaki T. (2016). Immune Response of Amebiasis and Immune Evasion by Entamoeba Histolytica. Front. Immunol. 7, 175. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novack D. V., Yin L., Hagen-Stapleton A., Schreiber R. D., Goeddel D. V., Ross F. P., et al. (2003). The Iκb Function of NF-κb2 P100 Controls Stimulated Osteoclastogenesis. J. Exp. Med. 198 (5), 771–781. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parroche P., Lauw F. N., Goutagny N., Latz E., Monks B. G., Visintin A., et al. (2007). Malaria Hemozoin is Immunologically Inert But Radically Enhances Innate Responses by Presenting Malaria DNA to Toll-Like Receptor 9. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 104 (6), 1919–1924. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608745104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Molina J. A., Molina I. (2018). Chagas Disease. Lancet 391 (10115), 82–94. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31612-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petri W. A., Smith R., Schlesinger P., Murphy C., Ravdin J. (1987). Isolation of the Galactose-Binding Lectin That Mediates the In Vitro Adherence of Entamoeba histolytica. J. Clin. Invest. 80 (5), 1238–1244. doi: 10.1172/JCI113198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto A. M., Sales P. C., Camargos E. R., Silva A. M. (2011). Tumour Necrosis Factor (TNF)-Mediated NF-κb Activation Facilitates Cellular Invasion of non-Professional Phagocytic Epithelial Cell Lines by Trypanosoma Cruzi. Cell. Microbiol. 13 (10), 1518–1529. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01636.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prucca C. G., Lujan H. D. (2009). Antigenic Variation in Giardia Lamblia. Cell. Microbiol. 11 (12), 1706–1715. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01367.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Que X., Brinen L. S., Perkins P., Herdman S., Hirata K., Torian B. E., et al. (2002). Cysteine Proteinases From Distinct Cellular Compartments are Recruited to Phagocytic Vesicles by Entamoeba Histolytica. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 119 (1), 23–32. doi: 10.1016/S0166-6851(01)00387-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosales C. (2021). Neutrophils vs. Amoebas: Immunity Against the Protozoan Parasite Entamoeba istolytica . J. Leukocyte Biol. 1–12. doi: 10.1002/JLB.4MR0521-849RR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosowski E. E., Lu D., Julien L., Rodda L., Gaiser R. A., Jensen K. D., et al. (2011). Strain-Specific Activation of the NF-κb Pathway by GRA15, a Novel Toxoplasma Gondii Dense Granule Protein. J. Exp. Med. 208 (1), 195–212. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothwarf D. M., Zandi E., Natoli G., Karin M. (1998). IKK-γ is an Essential Regulatory Subunit of the Iκb Kinase Complex. Nature 395 (6699), 297–300. doi: 10.1038/26261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacks D., Sher A. (2002). Evasion of Innate Immunity by Parasitic Protozoa. Nat. Immunol. 3 (11), 1041–1047. doi: 10.1038/ni1102-1041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeij J., Coller S., Boyle J., Jerome M., White M., Boothroyd J. (2007). Toxoplasma Co-Opts Host Gene Expression by Injection of a Polymorphic Kinase Homologue. Nature 445 (7125), 324–327. doi: 10.1038/nature05395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoro M. G., Rossi A., Amici C. (2003). NF-κb and Virus Infection: Who Controls Whom. EMBO J. 22 (11), 2552–2560. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasai M., Pradipta A., Yamamoto M. (2018). Host Immune Responses to Toxoplasma Gondii. Int. Immunol. 30 (3), 113–119. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxy004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seguin R., Mann B. J., Keller K., Chadee K. (1995). Identification of the Galactose-Adherence Lectin Epitopes of Entamoeba Histolytica That Stimulate Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha Production by Macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 92 (26), 12175–12179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senftleben U., Cao Y., Xiao G., Greten F. R., Krähn G., Bonizzi G., et al. (2001). Activation by Ikkα of a Second, Evolutionary Conserved, NF-κb Signaling Pathway. Science 293 (5534), 1495–1499. doi: 10.1126/science.1062677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seydel K. B., Li E., Swanson P. E., Stanley J. S. L. (1997). Human Intestinal Epithelial Cells Produce Proinflammatory Cytokines in Response to Infection in a SCID Mouse-Human Intestinal Xenograft Model of Amebiasis. Infect. Immun. 65 (5), 1631–1639. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.5.1631-1639.1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapira S., Harb O. S., Margarit J., Matrajt M., Han J., Hoffmann A., et al. (2005). Initiation and Termination of NF-κb Signaling by the Intracellular Protozoan Parasite Toxoplasma Gondii. J. Cell Sci. 118 (15), 3501–3508. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapira S., Speirs K., Gerstein A., Caamano J., Hunter C. (2002). Suppression of NF-κb Activation by Infection With Toxoplasma Gondii . J. Infect. Dis. 185 (Supplement_1), S66–S72. doi: 10.1086/338000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman N., Maniatis T. (2001). NF-κb Signaling Pathways in Mammalian and Insect Innate Immunity. Genes Dev. 15 (18), 2321–2342. doi: 10.1101/gad.909001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley J. S. L. (2003). Amoebiasis. Lancet 361 (9362), 1025–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12830-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St-Pierre J., Moreau F., Cornick S., Quach J., Begum S., Aracely Fernandez L., et al. (2017). The Macrophage Cytoskeleton Acts as a Contact Sensor Upon Interaction With Entamoeba Histolytica to Trigger IL-1β Secretion. PloS Pathog. 13 (8), e1006592. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S. -C. (2011). Non-Canonical NF-κB Signaling Pathway. Cell Res. 21 (1), 71–85. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S. C., Harhaj E. W. (2006). Receptors and Adaptors for NF-κB Signaling, ed. Liou HC. in: NF-κB/Rel Transcription Factor Family. Molecular Biology Intelligence Unit (Boston, MA: Springer; ), 26–40. doi: 10.1007/0-387-33573-0_3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tachado S. D., Gerold P., McConville M. J., Baldwin T., Quilici D., Schwarz R. T., et al. (1996). Glycosylphosphatidylinositol Toxin of Plasmodium Induces Nitric Oxide Synthase Expression in Macrophages and Vascular Endothelial Cells by a Protein Tyrosine Kinase-Dependent and Protein Kinase C-Dependent Signaling Pathway. J. Immunol. 156 (5), 1897–1907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taganov K. D., Boldin M. P., Chang K.-J., Baltimore D. (2006). NF-κb-Dependent Induction of microRNA miR-146, an Inhibitor Targeted to Signaling Proteins of Innate Immune Responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 103 (33), 12481–12486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605298103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda K., Akira S. (2005). Toll-Like Receptors in Innate Immunity. Int. Immunol. 17 (1), 1–14. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tato C., Hunter C. (2002). Host-Pathogen Interactions: Subversion and Utilization of the NF-κb Pathway During Infection. Infection Immun. 70 (7), 3311–3317. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.7.3311-3317.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenter A. M., Heckeroth A. R., Weiss L. M. (2000). Toxoplasma Gondii: From Animals to Humans. Int. J. Parasitol. 30 (12-13), 1217–1258. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(00)00124-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillack M., Biller L., Irmer H., Freitas M., Gomes M. A., Tannich E., et al. (2007). The Entamoeba Histolytica Genome: Primary Structure and Expression of Proteolytic Enzymes. BMC Genomics 8 (1), 1–15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillack M., Nowak N., Lotter H., Bracha R., Mirelman D., Tannich E., et al. (2006). Increased Expression of the Major Cysteine Proteinases by Stable Episomal Transfection Underlines the Important Role of EhCP5 for the Pathogenicity of Entamoeba Histolytica. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 149 (1), 58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2006.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toda H., Diaz-Varela M., Segui-Barber J., Roobsoong W., Baro B., Garcia-Silva S., et al. (2020). Plasma-Derived Extracellular Vesicles From Plasmodium Vivax Patients Signal Spleen Fibroblasts via NF-kB Facilitating Parasite Cytoadherence. Nat. Commun. 11 (1), 1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16337-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuladhar S., Kochanowsky J. A., Bhaskara A., Ghotmi Y., Chandrasekaran S., Koshy A. A. (2019). The ROP16III-Dependent Early Immune Response Determines the Subacute CNS Immune Response and Type III Toxoplasma Gondii Survival. PloS Pathog. 15 (10), e1007856. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkerke H. P., Petri W. A., Marie C. S. (2012). The Dynamic Interdependence of Amebiasis, Innate Immunity, and Undernutrition. Semin. Immunopathol. 34, 771–785. doi: 10.1007/s00281-012-0349-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma I. M., Stevenson J. K., Schwarz E. M., Van Antwerp D., Miyamoto S. (1995). Rel/NF-Kappa B/I Kappa B Family: Intimate Tales of Association and Dissociation. Genes Dev. 9 (22), 2723–2735. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.22.2723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vos T., Allen C., Arora M., Barber R. M., Bhutta Z. A., Brown A., et al. (2016). Global, Regional, and National Incidence, Prevalence, and Years Lived With Disability for 310 Diseases and Injuries 1990–2015: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 388 (10053), 1545–1602. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Zhang Z., Wang Y., Gadahi J. A., Xie Q., Xu L., et al. (2017). Toxoplasma Gondii Excretory/Secretory Antigens (TgESAs) Suppress Pro-Inflammatory Cytokine Secretion by Inhibiting TLR-Induced NF-κb Activation in LPS-Stimulated Murine Macrophages. Oncotarget 8 (51), 88351. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.19362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe Costa R., da Silveira J. F., Bahia D. (2016). Interactions Between Trypanosoma Cruzi Secreted Proteins and Host Cell Signaling Pathways. Front. Microbiol. 7, 388. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2016). World Malaria Report 2015 (Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; ), 1–181. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo C.-G., Lee S., Lee C.-T., Kim Y. W., Han S. K., Shim Y.-S. (2000). Anti-Inflammatory Effect of Heat Shock Protein Induction is Related to Stabilization of Iκbα Through Preventing Iκb Kinase Activation in Respiratory Epithelial Cells. J. Immunol. 164 (10), 5416–5423. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.10.5416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong H., Voll R. E., Ghosh S. (1998). Phosphorylation of NF-κb P65 by PKA Stimulates Transcriptional Activity by Promoting a Novel Bivalent Interaction With the Coactivator CBP/P300. Mol. Cell 1 (5), 661–671. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80066-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]