Abstract

Pancreatic cancer (PC) is a malignant tumor disease, whose molecular mechanism is not fully understood. Sodium channel epithelial 1α subunit (SCNN1A) serves an important role in tumor progression. The current study explored the role of homeobox D9 (HOXD9) and SCNN1A in the progression of PC. The expression of SCNN1A and HOXD9 in PC samples was predicted on online databases and detected in PC cell lines. The association between SCNN1A expression and PC prognosis was examined by the Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis, The Cancer Genome Atlas and Genotype-Tissue Expression databases and by a Kaplan-Meier plotter. Subsequently, the biological effects of SCNN1A on PC cell growth, colony formation, migration and invasion were investigated through RNA interference and cell transfection. Next, the expression of E-cadherin, N-cadherin, Vimentin and Snail was detected by western blotting to discover whether HOXD9 dysregulation mediated PC metastasis. Binding sites of HOXD9 and SCNN1A promoters were predicted on JASPAR. Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR and western blotting were used to detect the expression level of SCNN1A following interference and overexpression of HOXD9. Luciferase assay detected luciferase activity following interference with HOXD9 and the transcriptional activity of SCNN1A following binding site deletion. High expression of SCNN1A and HOXD9 in PC was predicted by online databases, signifying poor prognosis. The present study confirmed the above predictions in PC cell lines. Knockdown of SCNN1A and HOXD9 could effectively inhibit the proliferation, migration, invasion and epithelial-mesenchymal transition of PC cells. Furthermore, HOXD9 activated SCNN1A transcription, forming a feedback regulatory loop. HOXD9 was demonstrated to activate SCNN1A and promote the malignant biological process of PC.

Keywords: sodium channel epithelial 1α subunit, homeobox D9, pancreatic cancer, epithelial-mesenchymal transformation, proliferation, metastasis

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer (PC) is a lethal disease with increasing incidence that causes an estimate number of 227,000 deaths worldwide each year (1). It is listed as the 14th most common cancer and the seventh major cause of cancer death in the world (2). The incidence of PC in the developed world is increasing and its 5-year survival rate is as low as 2% in some nations despite improved surgical techniques, chemotherapy regimens and the introduction of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (3,4). Surgical resection is the mains curative treatment for PC in its early stages and most operations have a low mortality rate (5). However, due to the fact that PC can still metastasize following surgery, metastasis becomes the leading cause of death in patients with PC (6). It is hypothesized that epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) contributes to the early-stage spread of cancer cells and is essential for PC invasion and metastasis (7,8). Hence, identifying novel biomarkers for PC diagnosis and prognosis is of urgent necessity.

Epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) is an amido-sensitive epithelial sodium channel localized to the epithelial apical portion of the distal kidney, distal colon, lung and exocrine gland ducts (9). The channel is composed of a heteromeric complex of three homologous subunits α, β and γ, encoded by the sodium channel epithelial 1α subunit (SCNN1A), SCNN1B and SCNN1G genes respectively (10). There has been evidence that ENaC channels have key roles in cancer cell biology, such as proliferation, migration, invasion and apoptosis and serve a role in tumor development and progression (11,12). Among them, SCNN1A has been relatively well studied in cancer. SCNN1A has been shown to induce osteosarcoma tumor growth in vitro and in vivo (13). In addition, it has been demonstrated that SCNN1A may serve a key role in ovarian cancer cell growth, invasion and migration (14). Nevertheless, the role and biological significance of SCNN1A in PC remains to be elucidated.

Homeobox (HOX) genes are a superfamily of genes involved in embryonic development and cell differentiation (15). Homeobox D9 (HOXD9) is associated with the initiation and evolution of numerous malignant tumors, such as ovarian, glioma and cervical cancers (16–18). HOXD9 can promote the growth, invasion and metastasis of gastric cancer cells by transcriptional activation of RUN and FYVE domain containing 2 (19). Similarity, another study noted that HOXD9 regulates cervical cancer metastasis through transcriptional activation of its downstream gene HMCN1 (20). HOXD9 is a transcription factor for SCNN1A as predicted by the PROMO website. However, the role of HOXD9 in PC has not been reported. Therefore, it was hypothesized whether SCNN1A could produce an effect in PC by regulating HOXD9.

The present study aimed to investigate whether the transcription factor HOXD9 can activate SCNN1A transcription and thus affect the proliferation, invasion and migration of PC cells through the regulation of EMT.

Materials and methods

Online database analysis

Prior to the in vitro experiments, the Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis (GEPIA2, http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn) (21), The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA, http://tcga-data-nci-nih-gov.elib.tcd.ie/tcga/) (22) and Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx, http://gtexportal.org) databases (23) were used to compare the expression levels of SCNN1A and HOXD9 in patients with PC.

The GEPIA, TCGA and GTEx databases and Kaplan-Meier plotter website (http://kmplot.com/analysis/) (24) were next used to investigate the association between SCNN1A expression and the prognosis of PC.

JASPAR website (http://jaspar.binf.ku.dk/) was consulted to predict the binding sites of HOXD9 and SCNN1A promoter sequences. PROMO is freely available for download at http://acgt.cs.tau.ac.il/promo/. The Human Protein Atlas database (www.proteinatlas.org/pathology) was used to check the expression of SCNN1A in PC patient tissues via immunohistochemistry (IHC).

Cell lines and culture conditions

The human PC cell lines (BxPC-3, SW1990, PANC-1, CFPAC-1), together with the human non-cancerous pancreatic ductal epithelium cell line HPDE6c7, were purchased from the Type Culture Collection of the Chinese Academy of Science (Shanghai, China). The cells were grown in DMEM (HyClone) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 mg/ml streptomycin. All cells were then incubated in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C and the medium was replaced every 3 days.

Cell transfection

SW1990 cells (at 1×104 cells/well) were transferred to a 6-well plate and subsequently transfected with small interfering (sh)RNAs [shRNA-negative control (NC), shRNA-SCNN1A and shRNA-HOXD9] and empty pcDNA3.1 vector and HOXD9-overexpressing vector (Oe-HOXD9), which were purchased from Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd. The SCNN1A target sequence was 5′-CCAGAACAAATCGGACTGCTT−3′. The HOXD9 target sequence was 5′-GGACTCGCTTATAGGCCAT-3′. When the cells reached 60–70% confluence, they were transfected with 500 ng transfectants using 2.5 µl Lipofectamine® 3000 (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Following incubation at 37°C for 6 h, the serum-free DMEM was replaced with fresh DMEM containing 10% FBS, and the cells were incubated for 24 h.

RNA extraction and reverse transcription-quantitative (RT-q) PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cells using TRIzol® (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) following the manufacturer's instructions. RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using the PrimeScript RT kit (Qiagen GmbH). RT-qPCR was performed with SYBR Premix Ex Taq (Qiagen GmbH) to quantify the RNA expression. The following thermocycling conditions were used for the qPCR: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 6 min; followed by 40 cycles of initiation at 94°C for 30 sec, annellation at 60°C for 30 sec and elongation at 73°C for 90 sec. The 2−ΔΔCq (25) method was employed to assay relative expression levels. The primers for SCNN1A were: Forward 5′-AGGACTCTAGCCCTCCACAG-3′, reverse 5′-GTGGATGGTGGTGTTGTTGC-3′. The primers for HOXD9 were: Forward 5′-ACGTCCCCAAGCCAGGCTC-3′, reverse 5′-CTATGTAGCTCAGGAATAA-3′. The primers for GAPDH were: Forward 5′-CACCATTGGCAATGAGCGGTTC-3′, reverse 5′-AGGTCTTTGCGGATGTCCACGT-3′.

Western blotting

Total protein was extracted from SW1990 cells with RIPA lysis buffer supplemented with the proteinase inhibitors PMSF and PI (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology), the concentration was determined using a BCA assay protein assay kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Equal amounts (20 µg per lane) of the isolated protein was separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes (EMD Millipore). The membranes were blocked in 5% fat-free milk, and then were probed with the respective primary antibodies: SCNN1A (Abcam; 1:1,000; cat. no. ab272878), E-cadherin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.; 1:1,000; cat. no. sc-8426), N-cadherin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.; 1:1,000; cat. no. sc-59987), Vimentin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.; 1:1,000; cat. no. sc-6260), Snail (Abcam; 1:1,000; cat. no. ab229701), HOXD9 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.; 1:1,000; cat. no. sc-137134) and GAPDH (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.; 1:3,000; cat. no. sc-47724) at 4°C overnight. After washing three times with TBS-0.2% Tween-20, membranes were probed with a goat anti-rabbit HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.; 1:2,000; cat. no. 7074S) or horse anti-mouse HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.; 1:2,000; cat. no. 7076S;) at room temperature for 1 h. Proteins were visualized with an ECL detection system (Applygen Technologies, Inc.) and subsequently semi-quantified using ImageJ software (version 1.52r, National Institutes of Health). The protein expression of the bands was normalized against the gray value of GAPDH.

Cell proliferation assays

To measure the proliferation rate of SW1990 cells, Cell Counting Kit (CCK)-8 was used and a cell counting assay was conducted. Briefly, cells were seeded into 6-well plates and transfected with small RNA oligonucleotides or plasmids. At 24 h post-transfection, cells were reseeded. After 0, 24, 48 and 72 h of incubation, the optical density of each well was measured using a CCK-8 kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology; cat. no. C0038) according to the manufacturers' instructions and the number of cells was counted after incubation 1 h using a Celigo image cytometer (Nexcelom Bioscience LLC) at 450 nm. For cell colony assay, cells were seeded into 6-well plates at 500 cells per well. After 2 weeks, the cells were fixed with 75% ethanol at 37°C for 30 min and then stained with 0.1% crystalline violet at 37°C for 15 min. Finally, the cells were imaged and counted.

Wound-healing assay

The cells were cultured in 6-well plates and allowed to form cell monolayers overnight to full confluence. Then, a 20-µl sterile plastic tip was used to scratch a wound line across the surface of plates. The suspended cells were removed with PBS, while the rest were incubated with serum-free medium. Images were captured at 0 and 24 h after scratching using a 600 Autobiochemical Analyzer (Olympus Corporation), and ImageJ software (version 1.52r, National Institutes of Health) was used to calculate the average distance between cells. The width of wound healing was quantified and compared with baseline values.

Transwell invasion assay

Cells were injected (5×105 cells/well) into the upper chambers of Transwell chambers (8 µm pore size; Corning, Inc.) containing serum-free DMEM, while the lower chambers were supplemented with DMEM containing 10% FBS. The upper surface of the bottom membrane of Transwell chambers was covered with a dilution of Matrigel (BD Biosciences) at a ratio of 1:8 overnight at 37°C with 5% CO2. The chambers were incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Next, cells remaining in the upper chamber were gently removed with a cotton swab, while invading cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature and stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 20 min at 37°C. Invading SW1990 cells were counted using an inverted light microscope (Eclipse Ti2; Nikon Corporation) for cell counts and images were captured, and five areas were randomly selected for counting.

Luciferase assays

Luciferase activity in SW1990 cells was detected by interfering with HOXD9 and two SCNN1A promoter deletion mutants, respectively. The canonical HOXD9 binding motif and PVT1 promoter were constructed into the pGL3 plasmid (Promega Corporation), respectively. Cells were transfected with the pGL3-based reporter construct, and pRL-SV40 was the internal control plasmid. OPTI-MEM (49 µl) was pipetted onto 24-well plates to dilute 1 µl Lipofectamine® 2000 reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and the final volume was 50 µl. After 36 h of transfection, the cells were lysed and assayed via a dual-luciferase reporter assay kit (Promega Corporation) and normalized to that of Renilla luciferase activity.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

The ChIP assay was performed with a commercial kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology; cat. no. P2078) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cells were cross-linked using 1% formaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) in PBS at 25°C for 10 min. Termination of cross-linking was achieved by the addition of glycine (Beijing Solarbio Technology Co., Ltd.) to a final concentration of 125 µM. Then, 1×106 cells were collected via centrifugation at 300 × g for 3 min at 25°C and washed twice with pre-chilled PBS. The cells (1×106) were treated with 2 µg anti-HOXD9 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.; cat. no. sc-137134), anti-SCNN1A (Abcam; cat. no. ab272878) or anti-mouse IgG (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology; cat. no. A7028) antibodies, which were immunoprecipitated against cross-linked 100 µg DNA (using a spectrophotometer at 260 nm)/protein and incubated at 4°C for 2 h. A ChIP DNA purification kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology; cat. no. D0033) was used to purify the immunoprecipitated DNA and it was amplified via qPCR as described above. RT-qPCR was applied to the analysis of the enriched DNA.

Statistical analysis

The association between the pathological stage and SCNN1A expression as well as the relative levels of SCNN1A and HOXD9 in the tissues of patients with PC was analyzed by one-way ANOVA. The Kaplan-Meier test was performed to identify overall survival and disease-free survival-related clinical characteristics of patients with PC. Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation. All experiments were performed at least in triplicate. Unpaired Student's t-test was used to analyze differences between two groups. The differences among the multiple groups were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey's post hoc test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Highly expressed SCNN1A is found in PC tissues and is associated with poor prognosis

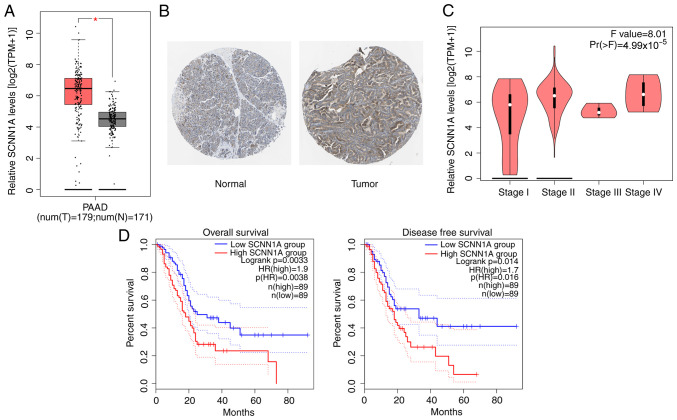

The GEPIA, TCGA and GTEx databases were used to analyze the expression level of SCNN1A in patients with PC. The results showed a high expression of SCNN1A in the tissues of patients with PC (Fig. 1A). This result was confirmed via IHC, which demonstrated more SCNN1A-positive cells in tumor sections of patients with PC compared with the normal tissues from the Human Protein Atlas database (Fig. 1B). The expression of SCNN1A was found to be significantly associated with the pathological stage of tumors in patients with PC (Fig. 1C). Similarly, the combined results of GEPIA, TCGA and GTEx databases revealed that patients with PC with high SCNN1A expression had a low overall survival rate and disease-free survival rate compared with those with low SCNN1A expression (Fig. 1D). These results implied that SCNN1A served a crucial role in PC progression.

Figure 1.

SCNN1A expression is upregulated in PC tissues and associated with prognosis. (A) SCNN1A expression in different disease state (tumor or normal) based on Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis, The Cancer Genome Atlas and Genotype-Tissue Expression databases. Left, num(T)=1,798; Right, num(N)=171. (B) SCNN1A expression in PC tumor sections by immunohistochemical staining from the Human Protein Atlas database (magnification, ×20). (C) Differential expression of SCNN1A in different pathological stage. (D) Kaplan-Meier plotter database was used for overall survival and disease-free survival analysis. Dashed lines represents 95% confidence intervals. *P<0.5 vs. N. SCNN1A, sodium channel epithelial 1α subunit; PC, pancreatic cancer; T, tumor tissues; N, normal tissues; PAAD, pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

SCNN1A promotes PC cell proliferation, invasion, migration and EMT

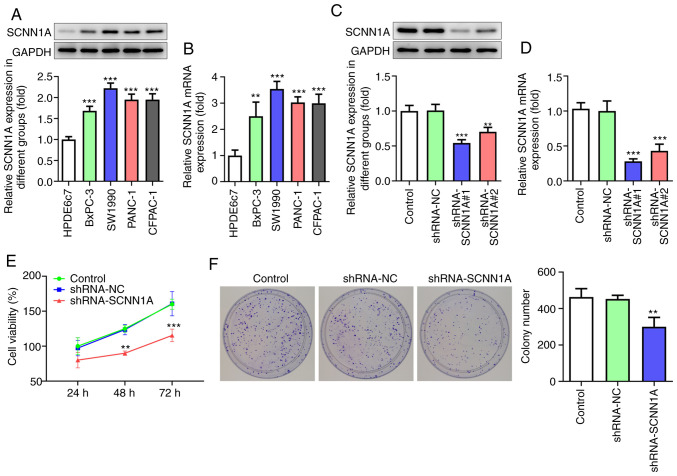

To investigate the role of SCNN1A, qPCR and western blotting were applied to test the mRNA and protein level of SCNN1A in PC cell lines (BxPC-3, SW1990, PANC-1 and CFPAC-1) and human non-cancerous pancreatic ductal epithelium cell line HPDE6c7. The expression level of SCNN1A was found to be significantly higher in all cancer cell lines compared with that in HPDE6c7 cells (Fig. 2A and B). As the expression level of SCNN1A in SW1990 was the highest among all four cancer cell lines, SW1990 cells were selected for the following experiments. SCNN1A shRNA was transfected into SW1990 cells to inhibit SCNN1A expression. It was detected by qPCR and western blotting that shRNA-SCNN1A#1 had improved efficacy compared with shRNA-SCNN1A#2 (Fig. 2C and D) when it came to SCNN1A knockdown. Thus, shRNA-SCNN1A#1 was chosen for the following experiments.

Figure 2.

SCNN1A facilitates PC cell proliferation. (A) SCNN1A protein expression in PC cell lines. (B) SCNN1A mRNA expression in PC cell lines. (C) SCNN1A protein expression following transfection with shRNA. (D) SCNN1A mRNA expression following transfection with shRNA. (E) CCK8 assay. (F) Colony formation assay (magnification, ×100). **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. the Control. SCNN1A, sodium channel epithelial 1α subunit; PC, pancreatic cancer; shRNA, short hairpin RNA.

To investigate the effect of SCNN1A on PC cell proliferation, CCK8 and colony formation assays were performed. According to the results obtained from the CCK8 assay, the shRNA-SCNN1A group showed markedly lower optical density value at 48 and 72 h compared with the Control and shRNA-NC group (Fig. 2E). Fig. 2F shows that following knocking down SCNN1A, the number of colonies was reduced relative to that in the Control and shRNA-NC groups. These results prove that SCNN1A suppression inhibits SW1990 cell proliferation.

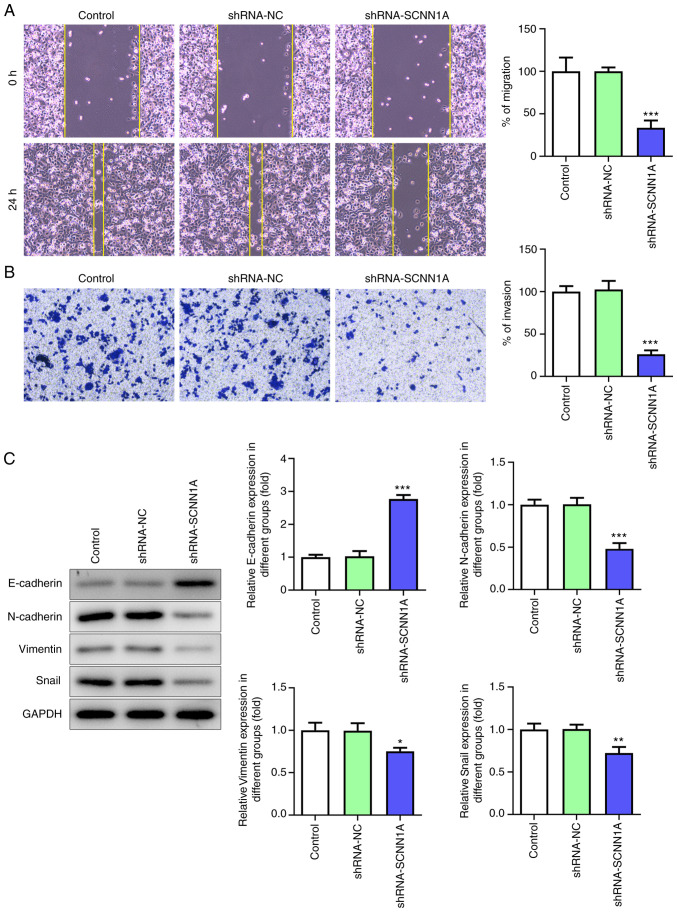

Wound healing assay and Transwell assay were used to determine the function of SCNN1A in the PC cell migration. After SCNN1A knockdown, SW1990 cell migrated much slower than the Control and shRNA-NC group (Fig. 3A). In the Transwell assay, the number of migrant cells in the SCNN1A silencing group was markedly fewer than the control group (Fig. 3B). These results indicated that SCNN1A promotes SW1990 cell migration.

Figure 3.

Silencing SCNN1A diminishes PC cell migration and EMT. (A) Wound healing and (B) Transwell assay (magnification, ×100). (C) Western blot analysis of E-cadherin, N-cadherin, Vimentin and Snail. GAPDH was used as a loading control. *P<0.5, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. the control. SCNN1A, sodium channel epithelial 1α subunit; PC, pancreatic cancer.

To further explore whether SCNN1A regulates EMT in PC cells, the expression levels of EMT-related cell markers were tested via western blotting. As shown in Fig. 3C, knockdown of SCNN1A notably decreased the expression levels of N-cadherin, Vimentin and Snail but increased the expression level of E-cadherin. This suggested that SCNN1A triggers EMT. Overall, these results demonstrated that SCNN1A promotes PC cell proliferation, invasion, migration and EMT.

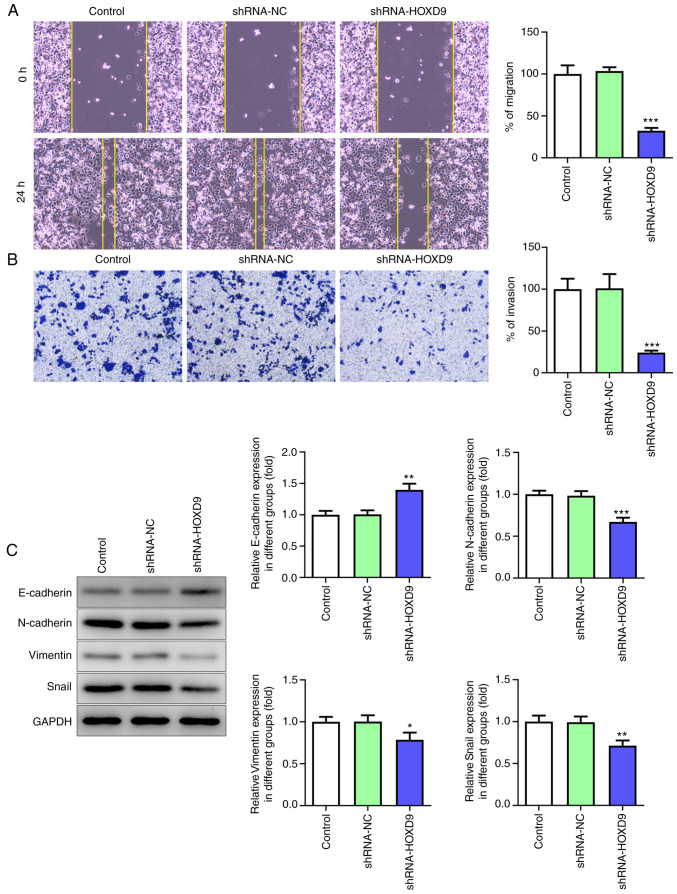

HOXD9 promotes PC cell proliferation, invasion, migration and EMT

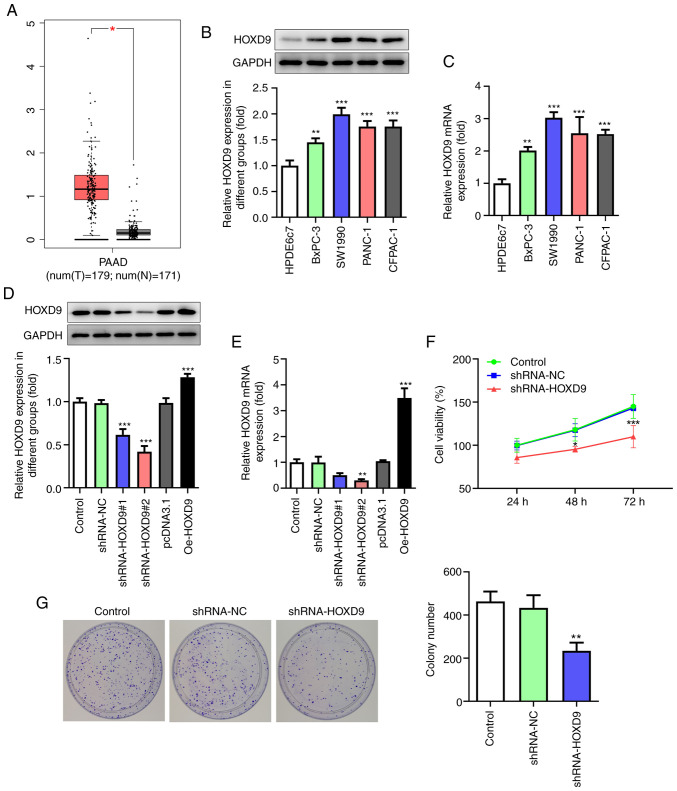

HOXD9 was predicted to be highly expressed in PC tissues by the GEPIA, TCGA and GTEx databases (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, this prediction was confirmed via qPCR and western blotting in PC cell lines (Fig. 4B and C). To investigate the effect of HOXD9 on PC, HOXD9 shRNA and overexpression plasmids Oe-HOXD9 were transfected into SW1990 cells. Fig. 4D and E shows that shRNA-HOXD9#2 was superior to shRNA-HOXD9#1 at reducing the expression level of HOXD9 and that Oe-HOXD9 up-regulated the expression of HOXD9 effectively. Therefore, shRNA-HOXD9#2 and Oe-HOXD9 were selected for the subsequent experiments. The CCK8 results revealed that downregulated HOXD9 reduced cell viability ratio at 48 and 72 h significantly (Fig. 4F). Similarly, the colony formation assay showed that HOXD9 knockdown suppressed PC cell proliferation (Fig. 4G). Additionally, HOXD9 silencing was validated to suppress PC cell migration and invasion (Fig. 5A and B). The protein expression of E-cadherin, N-cadherin, Vimentin and Snail was detected to explore the role of HOXD9 in EMT (Fig. 5C), which supported the hypothesis that HOXD9 promoted EMT in PC cells.

Figure 4.

HOXD9 is highly expressed in PC tissues and cell lines and promotes PC cell proliferation. (A) HOXD9 expression in PC tissues based on Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis, The Cancer Genome Atlas and Genotype-Tissue Expression databases. (B and C) HOXD9 expression in PC cell lines. (D and E) HOXD9 expression following transfection with shRNA and overexpression plasmids. (F) CCK8 assay. (G) Colony formation assay (magnification, ×100). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. the control. HOXD9, homeobox D9; PC, pancreatic cancer; shRNA, short hairpin RNA; PAAD, pancreatic adenocarcinoma; T, tumor tissues; N, normal tissues.

Figure 5.

Low expression of HOXD9 inhibits PC cell invasion, migration and epithelial to mesenchymal transition. (A) Wound healing and (B) Transwell migration and invasion assays (magnification, ×100). (C) Western blot analysis of E-cadherin, N-cadherin, Vimentin and Snail. GAPDH was used as a loading control. *P<0.5, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. the Control. HOXD9, homeobox D9; PC, pancreatic cancer.

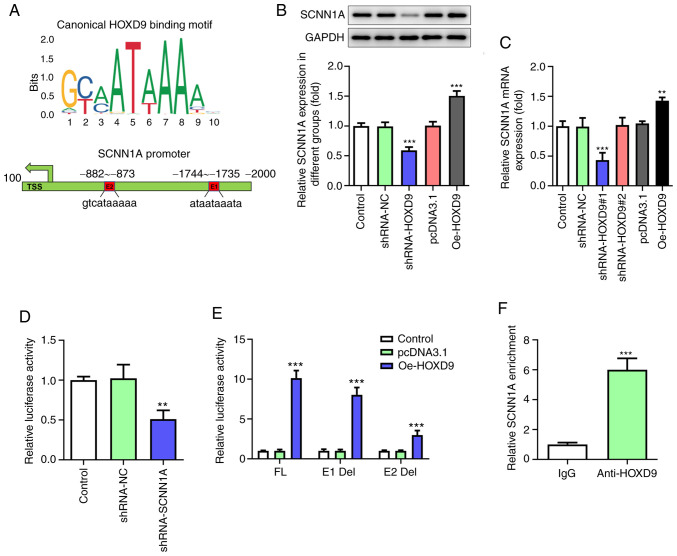

HOXD9 activates SCNN1A transcription to form a feedback regulatory loop

The JASPAR database was consulted to predict the binding of HOXD9 to SCNN1A promotor and two putative HOXD9-binding elements within the SCNN1A promoter region were discovered through bioinformatics analysis (Fig. 6A). Given the vital oncogenic roles of SCNN1A, whether HOXD9 could regulate SCNN1A expression in turn was further investigated. qPCR and western blotting assays proved that HOXD9 silencing decreased the expression of SCNN1A, whereas its overexpression had an opposite effect in SW1990 cells (Fig. 6B and C). This indicated that HOXD9 was positively associated with SCNN1A transcription. Luciferase assay confirmed that the SCNN1A promoter was significantly transactivated by HOXD9 (Fig. 6D). Next, to clarify which element was necessary for HOXD9-mediated SCNN1A expression, the two predicted HOXD9-binding sites were individually deleted, named E1 Del and E2 Del. Of note, both E1 and E2 absence was found to notably downregulate the transcriptional activity of SCNN1A, with E2 having a more pronounced effect (Fig. 6E). To validate this result, ChIP assay was performed with HOXD9 antibody, followed by PCR detection with a specific primer for the E2 element. As shown in Fig. 6F, HOXD9 could associate with SCNN1A promoter, as SCNN1A was enriched within the E2 region (−882-873 bp). These findings suggest that there is a regulatory feedback loop between HOXD9 and SCNN1A, which may continuously activate their oncogenic functions.

Figure 6.

HOXD9 can activate SCNN1A transcription to form feedback regulatory loop. (A) Schematic diagram of canonical HOXD9 binding motif (JASPAR Database) and two potential HOXD9 responsive elements (E1 and E2) in the SCNN1A promoter region. TSS is the transcriptional start site of SCNN1A. (B) SCNN1A protein levels with HOXD9 suppression and overexpression. (C) SCNN1A mRNA levels with HOXD9 suppression and overexpression. (D) Luciferase assay was used to detect SCNN1A promoter transcriptional activity when cells were transfected with shRNA-SCNN1A. (E) Two predicted HOXD9-binding sites of the SCNN1A promoter were individually deleted and termed E1-Del and E2-Del. Luciferase assay was employed to detect transcriptional activities of the two SCNN1A promoter deletion mutants when HOXD9 expression was enforced in SW1990 cells. (F) Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay. IgG served as a negative control. The data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. (n=3); **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. the control or IgG. HOXD9, homeobox D9; SCNN1A, sodium channel epithelial 1α subunit; shRNA, short hairpin RNA.

Discussion

PC is currently one of the most lethal malignancies, with a low 5-year survival rate (26). Therefore, it is important to study the causative factors of its rapid proliferation and aggressive metastasis for early diagnosis and good prognosis of PC and for the development of effective therapeutic agents. The focus of recent research into PC has been on searching for powerful prognostic markers, such as PRMT5, STC2 and Asporin, which are expected to be valuable to cancer classification aimed at adopting appropriate therapies and to an accurate forecast of the survival outcomes (27–29). The present study confirmed the oncogenic effect of SCNN1A and HOXD9 and validated their prognostic value in predicting PC. Through in vitro assays, it was observed that HOXD9 and SCNN1A were highly expressed in PC tissues and cells. Knockdown of HOXD9 and SCNN1A could inhibit cell proliferation, migration and EMT. Furthermore, the expression of HOXD9 and SCNN1A was verified to be positively associated in PC cells. The combination of high levels of HOXD9 and SCNN1A signified a poorer prognosis.

SCNN1A has been reported to be involved in a variety of diseases, such as ovarian cancer, Lam's disease and pseudoaldosteronism type 1 (30,31). Its implication in PC is not yet confirmed. SCNN1A has been validated as exhibiting extremely high sensitivity and specificity in melanoma detection (32). A study showed that miR-95 regulates the cell cycle and apoptosis of osteosarcoma cells by targeting SCNN1A (13). In the present study, the expression of SCNN1A was first predicted by the databases and was found to be significantly high in tissue samples from patients with PC and negatively associated with the prognosis. The role of SCNN1A in PC was examined through an in vitro model. Experiments have proved that SCNN1A silence has an inhibitory effect on ovarian cancer cell growth, migration and invasion (14). The results of the present study yielded the same conclusion that silencing SCNN1A can inhibit PC cell proliferation, migration and EMT. Metastasis is the main feature of cancer and the leading cause of death in ~90% of cancer patients (33). Upregulation of EMT-related transcription factors can suppress tumor cell apoptosis and promote cell lineage tumor invasiveness, leading to angiogenesis, development of chemotherapy resistance and poor prognosis for clinical tumor patients. Thus, SCNN1A may promote PC cell proliferation and migration and may serve as a predictive marker by regulating EMT.

HOXD9 is a transcription factor of SCNN1A according to database prediction. HOXD9 also serves a central role in the development of cancer by regulating the expression of multiple genes and promoting cell proliferation, migration and invasion. It has proven to promote the growth, invasion and metastasis of gastric cancer cells (19). Ectopic expression of HOXD9 has been shown to promote the invasive metastasis of colorectal tumor cells (34). The role of HOXD9 in PC was also explored in the present study. The results indicated that HOXD9 was overexpressed in PC and that HOXD9 silence inhibited PC cell proliferation, migration and EMT.

HOXD9 can interact with the promoter region of Zinc Finger E-Box Binding Homeobox 1 (ZEB1) and promotes ZEB1 expression (35). HOXD9 promotes the expression of HPC16 E6 and E7 through direct binding to the P97 promoter, thereby enhancing the proliferation, migration and metastasis of cervical cancer cells (18). In the present study, the interaction between HOXD9 and SCNN1A was revealed. Activated HOXD9 stimulated SCNN1A expression by directly occupying the −882–873 bp motif of the SCNN1A promoter region. These pieces of evidence supported that SCNN1A can form a positive feedback loop with its binding partner HOXD9, thus continuously enhancing its oncogenic effect and aggravating cancer progression.

The present study also has some limitations. For example, 3-D growth assay would be superior in detecting EMT, which we failed to demonstrate well due to the limited conditions.

In conclusion, the present study elucidated that HOXD9 induced SCNN1A upregulation and promoted PC cell proliferation and migration by regulating EMT, potentially serving as a promising prognostic marker. These results propose a possible role of SCNN1A as a prognostic factor and a candidate therapeutic target for PC. This may provide a research base for early detection and clinical management of PC. However, the present in vitro study does venture conclusions without in vivo data. Therefore, the results will be further validated with animal models as well as clinical samples in future experimental studies.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Research Project of Jiangxi Education Department (grant no. 191405).

Funding

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Research Project of Jiangxi Education Department (grant no. 191405).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

JHC and XTJ designed the present study. XGH, JNN and XHZ performed the experiments, analyzed the data and prepared the figures, and drafted the initial manuscript. JHC reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. JHC and JNN have read and confirm the authenticity of the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Vincent A, Herman J, Schulick R, Hruban RH, Goggins M. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet. 2011;378:607–620. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62307-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGuigan A, Kelly P, Turkington RC, Jones C, Coleman HG, McCain RS. Pancreatic cancer: A review of clinical diagnosis, epidemiology, treatment and outcomes. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:4846–4861. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i43.4846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neoptolemos JP, Kleeff J, Michl P, Costello E, Greenhalf W, Palmer DH. Therapeutic developments in pancreatic cancer: Current and future perspectives. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15:333–348. doi: 10.1038/s41575-018-0005-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zeng S, Pöttler M, Lan B, Grutzmann R, Pilarsky C, Yang H. Chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:4504. doi: 10.3390/ijms20184504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collisson EA, Bailey P, Chang DK, Biankin AV. Molecular subtypes of pancreatic cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:207–220. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0109-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rhim AD, Mirek ET, Aiello NM, Maitra A, Bailey JM, McAllister F, Reichert M, Beatty GL, Rustgi AK, Vonderheide RH, et al. EMT and dissemination precede pancreatic tumor formation. Cell. 2012;148:349–361. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reichert M, Bakir B, Moreira L, Pitarresi JR, Feldmann K, Simon L, Suzuki K, Maddipati R, Rhim AD, Schlitter AM, et al. Regulation of epithelial plasticity determines metastatic organotropism in pancreatic cancer. Dev Cell. 2018;45:696–711.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2018.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Canessa CM, Schild L, Buell G, Thorens B, Gautschi I, Horisberger JD, Rossier BC. Amiloride-sensitive epithelial Na+ channel is made of three homologous subunits. Nature. 1994;367:463–467. doi: 10.1038/367463a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jasti J, Furukawa H, Gonzales EB, Gouaux E. Structure of acid-sensing ion channel 1 at 1.9 A resolution and low pH. Nature. 2007;449:316–323. doi: 10.1038/nature06163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu C, Zhu LL, Xu SG, Ji HL, Li XM. ENaC/DEG in tumor development and progression. J Cancer. 2016;7:1888–1891. doi: 10.7150/jca.15693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu S, Liu C, Ma Y, Ji HL, Li X. Potential roles of amiloride-sensitive sodium channels in cancer development. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:2190216. doi: 10.1155/2016/2190216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geng Y, Zhao S, Jia Y, Xia G, Li H, Fang Z, Zhang Q, Tian R. miR95 promotes osteosarcoma growth by targeting SCNN1A. Oncol Rep. 2020;43:1429–1436. doi: 10.3892/or.2020.7514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu L, Ling ZH, Wang H, Wang XY, Gui J. Upregulation of SCNN1A promotes cell proliferation, migration, and predicts poor prognosis in ovarian cancer through regulating epithelial-mesenchymal transformation. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2019;34:642–649. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2019.2824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jerkovic I, Ibrahim DM, Andrey G, Haas S, Hansen P, Janetzki C, González Navarrete I, Robinson PN, Hecht J, Mundlos S. Genome-wide binding of posterior HOXA/D transcription factors reveals subgrouping and association with CTCF. PLoS Genet. 2017;13:e1006567. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pernía O, Sastre-Perona A, Rodriguez-Antolin C, García-Guede A, Palomares-Bralo M, Rosas R, Sanchez-Cabrero D, Cruz P, Rodriguez C, Diestro M, et al. A novel role for the tumor suppressor gene ITF2 in tumorigenesis and chemotherapy response. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12:786. doi: 10.3390/cancers12040786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li ZG, Xiang WC, Shui SF, Han XW, Guo D, Yan L. 11 Long noncoding RNA UCA1 functions as miR-135a sponge to promote the epithelial to mesenchymal transition in glioma. J Cell Biochem. 2020;121:2447–2457. doi: 10.1002/jcb.29467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirao N, Iwata T, Tanaka K, Nishio H, Nakamura M, Morisada T, Morii K, Maruyama N, Katoh Y, Yaguchi T, et al. Transcription factor homeobox D9 is involved in the malignant phenotype of cervical cancer through direct binding to the human papillomavirus oncogene promoter. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;155:340–348. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2019.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu H, Dai W, Li J, Xiang L, Wu X, Tang W, Chen Y, Yang Q, Liu M, Xiao Y, et al. HOXD9 promotes the growth, invasion and metastasis of gastric cancer cells by transcriptional activation of RUFY3. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2019;38:412. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1399-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wen D, Wang L, Tan S, Tang R, Xie W, Liu S, Tang C, He Y. HOXD9 aggravates the development of cervical cancer by transcriptionally activating HMCN1. Panminerva Med. 2020 May 14; doi: 10.23736/S0031-0808.20.03911-7. doi: 10.23736/S0031-0808.20.03911-7 (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu X, Bing Z, Wu J, Zhang J, Zhou W, Ni M, Meng Z, Liu S, Tian J, Zhang X, et al. Integrative gene expression profiling analysis to investigate potential prognostic biomarkers for colorectal cancer. Med Sci Monit. 2020;26:e918906. doi: 10.12659/MSM.918906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tomczak K, Czerwińska P, Wiznerowicz M. The cancer genome atlas (TCGA): An immeasurable source of knowledge. Contemp Oncol (Pozn) 2015;19:A68–A77. doi: 10.5114/wo.2014.47136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.GTEx Consortium. The genotype-tissue expression (GTEx) project. Nat Genet. 2013;45:580–585. doi: 10.1038/ng.2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lacny S, Wilson T, Clement F, Roberts DJ, Faris P, Ghali WA, Marshall DA. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis overestimates cumulative incidence of health-related events in competing risk settings: A meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;93:25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu L, Faruqu FN, Lim YM, Lim KY, Liam-Or R, Walters AA, Lavender P, Fear D, Wells CM, Tzu-Wen Wang J, Al-Jamal KT. Exosome-mediated RNAi of PAK4 prolongs survival of pancreatic cancer mouse model after loco-regional treatment. Biomaterials. 2021;264:120369. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.120369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin C, Sun L, Huang S, Weng X, Wu Z. STC2 Is a potential prognostic biomarker for pancreatic cancer and promotes migration and invasion by inducing epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:8042489. doi: 10.1155/2019/8042489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ge L, Wang H, Xu X, Zhou Z, He J, Peng W, Du F, Zhang Y, Gong A, Xu M. PRMT5 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition via EGFR-β-catenin axis in pancreatic cancer cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24:1969–1979. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.14894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang L, Wu H, Wang L, Zhang H, Lu J, Liang Z, Liu T. Asporin promotes pancreatic cancer cell invasion and migration by regulating the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) through both autocrine and paracrine mechanisms. Cancer Lett. 2017;398:24–36. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crosby JR, Zhao C, Jiang C, Bai D, Katz M, Greenlee S, Kawabe H, McCaleb M, Rotin D, Guo S, Monia BP. Inhaled ENaC antisense oligonucleotide ameliorates cystic fibrosis-like lung disease in mice. J Cyst Fibros. 2017;16:671–680. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2017.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dirlewanger M, Huser D, Zennaro MC, Girardin E, Schild L, Schwitzgebel VM. A homozygous missense mutation in SCNN1A is responsible for a transient neonatal form of pseudohypoaldosteronism type 1. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;301:E467–E473. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00066.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.D'Arcangelo D, Scatozza F, Giampietri C, Marchetti P, Facchiano F, Facchiano A. Ion channel expression in human melanoma samples: In silico identification and experimental validation of molecular targets. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11:446. doi: 10.3390/cancers11040446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pastushenko I, Blanpain C. EMT transition states during tumor progression and metastasis. Trends Cell Biol. 2019;29:212–226. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2018.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu M, Xiao Y, Tang W, Li J, Hong L, Dai W, Zhang W, Peng Y, Wu X, Wang J, et al. HOXD9 promote epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis in colorectal carcinoma. Cancer Med. 2020;9:3932–3943. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lv X, Li L, Lv L, Qu X, Jin S, Li K, Deng X, Cheng L, He H, Dong L. HOXD9 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer metastasis by ZEB1 regulation in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2015;34:133. doi: 10.1186/s13046-015-0245-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.