Abstract

Spontaneous renal artery dissection is a rare condition with an often non-specific presentation, resulting in a challenging diagnosis for clinicians. This is the case of a 39-year-old man who presented with an acute-onset right flank pain, mild neutrophilia and sterile urine. CT of abdomen and pelvis showed a patchy hypodense area in the right kidney originally thought to represent infection. He was treated as an atypical pyelonephritis with antibiotics and fluids. When his symptoms failed to improve, a diagnosis of renal infarction was considered and CT angiogram of the aorta revealed a spontaneous renal artery dissection. He was managed conservatively with systemic anticoagulation, antihypertensive treatment and analgesia and discharged home with resolution of his symptoms and normal renal function.

Keywords: renal medicine, cardiovascular medicine, radiology, renal intervention, vascular surgery

Background

Spontaneous renal artery dissection (SRAD) is a rare pathology, which if missed, can have serious consequences for the patient. Non-specific symptoms include flank pain, nausea, vomiting, fever and haematuria, a presentation resembling many common genitourinary or gastrointestinal conditions.1 Clinicians must be mindful of the possibility of SRAD in those who present with this common constellation of symptoms, as failure to diagnose SRAD promptly can result in progressive loss of renal function which may be unrecoverable.1 This case demonstrates the necessity to consider SRAD when patients with presumptive genitourinary diagnoses do not respond to treatment and how conservative management may be the optimum course of treatment.

Case presentation

A 39-year-old man was brought to the emergency department with an acute-onset, severe right flank pain. He described driving to work when suddenly he felt a stabbing pain in his right flank, radiating to his umbilicus and groin. The pain was constant and was associated with a single episode of vomiting.

The patient reported feeling well in the days leading up to his presentation. His bowels and bladder had been functioning normally. He had not experienced any haematuria, dysuria or frequency. While in the emergency department, he continued to pass urine normally.

The patient had no history of renal calculi, urinary tract infections or pyelonephritis. His medical history was significant only for gout, for which he took occasional eterocoxib as prescribed by his general practitioner. He did not take any other medications. He had a family history of renal calculi. The patient worked as an accounts manager, described an active lifestyle and drank alcohol infrequently. He was an ex-smoker, having quit 4 months ago, with a 7 pack-year history.

On arrival at the emergency department, the patient was afebrile, with a temperature of 36.2°C, pulse was 77 beats/min and blood pressure of 130/71 mm Hg. On examination, he was in severe discomfort. His abdomen was soft but extremely tender on palpation of the right iliac fossa, extending around to the right renal angle. He did not have peritoneal signs, and the remainder of the physical examination was normal.

Investigations/differential diagnosis

The patient was initially reviewed by the surgical team on-call whose first impression was that of appendicitis. Given his presenting symptoms of flank pain and vomiting, pyelonephritis and nephrolithiasis were also considered within the differential diagnosis. The patient was commenced on intravenous co-amoxiclav, fluids and analgesia while baseline investigations were carried out.

Urinalysis was negative for blood, nitrites or leukocytes, but given the nature of the patient’s presentation the sample was sent for culture. Baseline blood samples revealed a slightly elevated white blood cell 11.6×109 /L with a neutrophilia, normal haemoglobin 156g/L, normal renal function and C reactive protein <1. ECG showed normal sinus rhythm with a rate of 73 beats/min, normal axis and no ST elevation/depression or T-wave inversion.

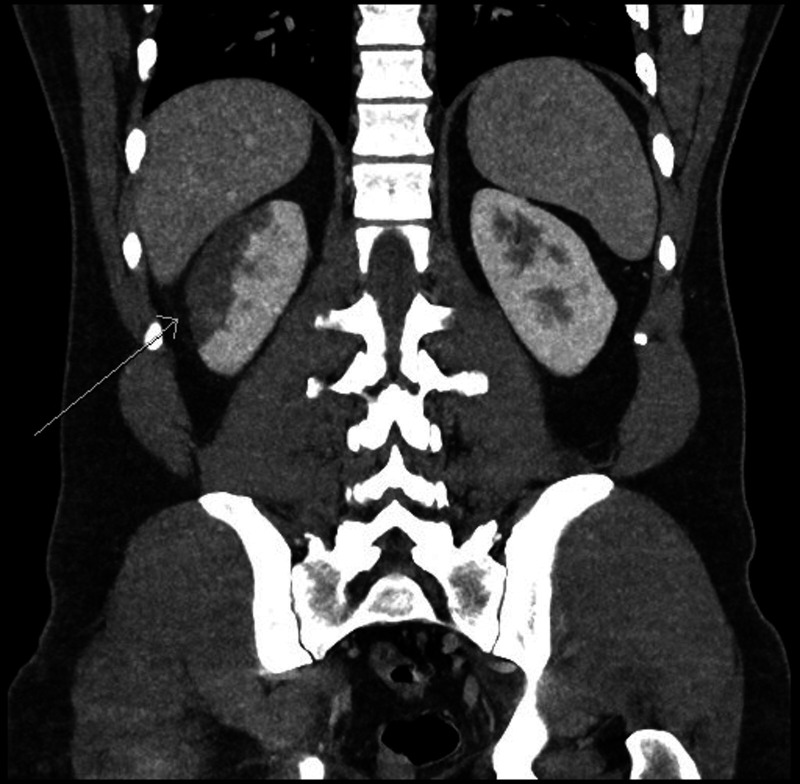

CT abdomen and pelvis (figure 1) was carried out on day 2 of admission using both oral and intravenous contrast. This demonstrated a normal appendix and was negative for any renal calculi. However, an area of patchy hypodensity was seen in the interpolar region of the right kidney spanning up to 5 cm, with a focal wedge-shaped region at the inferior margin. This was reported to most likely represent an area of infection.

Figure 1.

CT abdomen and pelvis, arrow points to a wedge-shaped area of hypoattenuation in the interpolar region of the right kidney, typical of infarction.

After the CT abdomen and pelvis had been performed and the diagnosis of appendicitis could be confidently ruled-out, the surgical team requested that the nephrology team consult on the patient, following which both teams agreed it was appropriate that the patient be transferred under the care of nephrology team for medical workup and management. The patient continued to be treated with antibiotics, however, in the following days his pain was still severe, he remained afebrile and urine cultures were negative for any growth. The patient’s sterile urine and continuously unimpressive inflammatory markers suggested that infection was not the cause of his symptoms.

On day 3 of the patient’s admission, ultrasound scan of the kidneys and bladder was carried out and demonstrated a hyperechoic area of abnormality in the parenchyma of the upper pole and interpolar region of the right kidney. The reporting radiologists stated that this abnormal area could either represent an area of pyelonephritis or infarction, but that given the clinical context, infarction was now more likely. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) measured the previous day was found to be moderately elevated at 427 U/L which would correlate with the diagnosis of infarction. Antibiotics were stopped at this point and the patient was pre-emptively commenced on a therapeutic dose of enoxaparin (100 mg, two times a day) subcutaneously while the suspected diagnosis of infarction was further explored.

Thrombophilia screen was performed prior to commencing enoxaparin to exclude a clotting disorder as a potential cause of infarction, including factor V Leiden mutation, anti-Xa and prothrombin genes. These all returned within normal ranges. Autoantibody screen was sent including antinuclear, double-stranded DNA, extractable nuclear antigen (ENA) profile, anticardiolipin and antineutrophil cytoplasmic including anti-PR3 and myeloperoxidase (MPO) antibodies. IgG4 and ß2 glycoprotein levels were also sent for evaluation. Again, these returned as normal.

Both transthoracic, and transoesophageal echo were carried out in the following days to outrule a cardiac source of emboli causing infarction. Both were negative for any valvular defects, and contrast bubble echo study revealed only a possible small patent foramen ovale, thought unlikely to be of significance. Holter monitoring did not reveal any arrythmia which might promote embolus formation. D-dimer was also found to be within normal range at 0.23 mg/L.

CT angiogram of the aorta (figures 2 and 3) was performed on day 8 of the patient’s admission. Appearances of the right kidney were seen to have progressed and favoured subcapsular infarction. Using image reconstruction techniques, dissection of a branch of the right renal artery was seen. However, at the time of imaging, patent flow was seen in the affected vessel. Having discovered the dissection, we could now confidently assume this event had caused a transient period of ischaemia, leading to the area of infarction.

Figure 2.

CT angiogram of the aorta, arrow points to extension of the area of infarction.

Figure 3.

(A) Coronal and (B) sagittal views on CT angiogram of the aorta, arrow points to a subtle dissection of the right renal artery with true and false lumens visible.

Considering the history of the patient’s presentation, no provoking event for the dissection was identified, and underlying conditions such as Ehlers Danlos syndrome and fibromuscular dysplasia were not suspected. For these reasons, the final diagnosis of SRAD was made.

Treatment

When the diagnosis of a renal infarct was initially suspected, the patient was commenced on therapeutic enoxaparin, and antibiotics were stopped. His pain was treated with analgesia including regular paracetamol and oxycodone and occasional oxynorm and tramadol. He was kept well-hydrated with intravenous fluids, and nausea was treated with intravenous ondansetron.

Following discussion with our colleagues in radiology and vascular surgery concerning the diagnosis of renal artery dissection, the decision was made that the patient would be managed conservatively, rather that with intervention aimed at arterial reconstruction. This was supported by the patient’s imaging, which confirmed that two-thirds of the affected kidney and his entire left kidney were radiologically unaffected. He also continued to have a normal creatinine (104 umol/L on discharge).

In regard to cardiovascular risk, the patient was an ex-smoker, with a body mass index of 30 kg/m2. He did not have a family history of cardiovascular disease or diabetes. Lipid profile revealed elevated low-density lipoprotein (4.3 mmol/L) and total cholesterol (6 mmol/L). Glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1C) was normal. The patient was advised to minimise the cardiovascular risk factors such as he should remain abstinant from cigarettes and lose weight. Having suffered a flare of his gout as an inpatient, he was discharged on febuxostat. He was commenced on rivaroxaban 20 mg, one time a day, and was to continue taking this for 6 months post discharge. He was also commenced on aspirin 75 mg, one time a day, atorvastatin 40 mg, at night and bisoprolol 2.5 mg, one time a day, for their cardioprotective, cholesterol-lowering and antihypertensive effects, respectively.

Outcome and follow-up

At the point of discharge, the patient washealthy and his flank pain had resolved. His renal function was normal, and inflammatory markers were mildly raised (CRP 42) but trending downwards. He returned to the outpatient department for follow-up after 3 months, where dimercapto succinic acid (DMSA)

scan showed stable appearance of the right kidney, with estimated split renal function of 40% on the right and 60% on the left, suggesting loss of function of approximately one-fifth to the right kidney. Follow-up CT angiography 8 months after the acute event showed an irregular but patent segmental right renal artery, and stable appearances of the upper pole scarring. The patient remains healthy with normal renal function.

Discussion

Isolated renal artery dissection is rare, accounting for 1%–2% of all arterial dissections.1 Since the first reported case of renal artery dissection in 1944,2 cases have been sparsely reported in the literature, with only approximately 200 cases reported since.

In the majority of cases no cause is found, which is referred to as SRAD. Where an underlying cause is identified, etiologies may include trauma (blunt or iatrogenic), malignant hypertension, atherosclerosis, connective tissue disorders such as fibromuscular dysplasia, Marfan’s syndrome and Ehlers Danlos syndrome, or cocaine use.1 3 4 It is four times more common in men, with a mean age at presentation of 47.2 years.1 Our patient fits the typical patient profile for SRAD; a middle-aged male, who was generally fit and healthy prior to presentation.

The dissection occurs as a result of intramural haemorrhage from the vasa vasorum or by penetration of blood into the arterial wall through an intimal tear.5 Depending on the severity and extent of the dissection, this can lead to renal ischaemia which may progress to infarction.6 SRAD typically presents acutely, with severe flank pain ipsilateral to the side of the dissection,1 6 as was reported by our patient. Additional non-specific symptoms may include nausea, vomiting, headache and fever.6 The most common sign on presentation is uncontrolled hyertension,1 6 however, unusually our patient was normotensive on initial assessment.

At presentation, patients often have a leucocytosis and elevated serum LDH, indicative of renal parenchymal loss.4 7 Urinalysis may reveal microscopic haematuria but is often negative.7 Where pyelonephritis, nephrolithiasis or appendicitis are considered possible diagnoses, CT abdomen and pelvis is usually performed. As seen in our case, this may demonstrate an area of hypoattenuation representing infarction. The gold standard method of diagnosis of SRAD is angiography, with CT angiogram providing a fast, non-inasive and easily accesible means of identifying the area and extent of dissection.1 6 7

There are two treatment pathways for SRAD: conservative medical management or endovascular intervention. The treatment choice is determined by the duration of renal ischaemia, the degree of renal injury, associated hypertension and the presence of a normal contralateral kidney.5 8 While no specific treatment guidelines exist for this rare condition, the literature suggests that the choice of treatment should take into account the factors listed above to determine the risk–benefit ratio of intervention versus a conservative approach.4 5 7

In a patient who is haemodynamically unstable, with uncontrolled hypertension or extensive renal damage, an interventional approach may be taken. This performed either endovascularly via stenting, coiling or embolisation, or a surgically via total nephrectomy.

Our patient was haemodynamically stable and normotensive. Imaging demonstrated that renal damage was limited to interpolar region of the right kidney. Serum creatinine was within the normal range. Thus, a conservative approach was taken, consisting of systemic anticoagulation, antihypertensive treatment, pain management and optimisation of cardiovascular risk factors.3 7 9

Choice of antihypertensive agent is at the discretion of the treating physician, taking into account local hypertension treatment guidelines. ACE inhibition or angiotensin receptor blockade may be preferable in patients with demonstrated renovascular atherosclerosis in the absence of acute kidney injury.4 5 10 The role of anticoagulation treatment is to prevent thrombosis at the site of the endothelial injury which may occlude the true lumen or result in extension of the dissection.1 The ideal duration of anticoagulation is unclear, however antihypertensive treatment should be lifelong.1 9

Both conservative and interventional methods of treatment have comparable outcomes.1 Conservative management is preferred where possible and in the majority of cases patient outcome is favourable,6 with some instances of spontaneous resolution being noted at follow-up imaging.9

Learning points.

Spontaneous renal artery dissection (SRAD) may present with a constellation of symptoms mimicking pyelonephritis or nephrolithiasis. Sudden onset of symptoms with negative urinalysis and laboratory investigations that do not point towards infection, renal SRAD should be considered.

Angiography is the gold standard for diagnosis of renal artery dissection, and CT angiography offers a widely accesible, fast and non-interventional method of diagnosis.

Conservative management including anticoagulation and tight blood pressure control is the preferred approach in a patient who is haemodynamically stable with preserved renal function. It has lower risk than interventional management and has comparative patient outcomes.

Footnotes

Contributors: CMH, GB and PME were involved in patient care. CMH gathered the information relevant to the case and drafted the case report under the supervision of GB. PME selected radiological images and provided accompanying descriptions. GB reviewed and edited the report. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Obtained.

References

- 1.Jha A, Afari M, Koulouridis I, et al. Isolated renal artery dissection: a systematic review of case reports. Cureus 2020;12:e6960. 10.7759/cureus.6960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bumpus HC. A case of renal hypertension. J Urology 1944;52:295–9. 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)70262-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jeong M-J, Kwon H, Kim A, et al. Clinical outcomes of conservative treatment in patients with symptomatic isolated spontaneous renal artery dissection and comparison with superior mesenteric artery dissection. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2018;56:291–7. 10.1016/j.ejvs.2018.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chamarthi G, Koratala A, Ruchi R. Spontaneous renal artery dissection masquerading as urinary tract infection. BMJ Case Rep 2018;2018. 10.1136/bcr-2018-226230. [Epub ahead of print: 21 Oct 2018]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stawicki SP, Rosenfeld JC, Weger N, et al. Spontaneous renal artery dissection: three cases and clinical algorithms. J Hum Hypertens 2006;20:710–8. 10.1038/sj.jhh.1002045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Afshinnia F, Sundaram B, Rao P, et al. Evaluation of characteristics, associations and clinical course of isolated spontaneous renal artery dissection. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2013;28:2089–98. 10.1093/ndt/gft073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katz-Summercorn AC, Borg CM, Harris PL. Spontaneous renal artery dissection complicated by renal infarction: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Surg Case Rep 2012;3:257–9. 10.1016/j.ijscr.2012.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vitiello GA, Blumberg SN, Sadek M. Endovascular treatment of spontaneous renal artery dissection after failure of medical management. Vasc Endovascular Surg 2017;51:509–12. 10.1177/1538574417723155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Korkut M, Bedel C. Aortic dissection or spontaneous renal artery dissection, a rare diagnosis? CEN Case Rep 2020;9:257–9. 10.1007/s13730-020-00469-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Losito A, Errico R, Santirosi P, et al. Long-term follow-up of atherosclerotic renovascular disease. beneficial effect of ACE inhibition. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2005;20:1604–9. 10.1093/ndt/gfh865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]