Abstract

This study uses toxicology screening data from a health care delivery system to investigate whether rates of cannabis use increased among pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Cannabis use among pregnant women is common and has increased in recent years in the US, from an estimated 3.4% in 2002 to 7.0% in 2017.1 Pregnant women report using cannabis to relieve stress and anxiety,2 and prenatal cannabis use may have risen during the COVID-19 pandemic as pregnant women faced general and pregnancy-specific COVID-related stressors (eg, social isolation, financial and psychosocial distress, increased burden of childcare, changes in prenatal care, and concerns about heightened risks of COVID-19).3,4

Considered an essential business in California, cannabis retailers remained open during the pandemic with record sales in 2020.5 We used data from Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC), a large integrated health care delivery system with universal screening for prenatal cannabis use to test the hypothesis that rates of prenatal cannabis use increased during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

The sample comprised all KPNC pregnant women screened for prenatal cannabis use via a universal urine toxicology test from January 1, 2019, through December 31, 2020, during standard prenatal care (at ≈8 weeks’ gestation). The institutional review board of KPNC approved this study and waived the need for informed consent.

We computed monthly rates of prenatal cannabis use standardized to the year 2020 age and race and ethnicity distribution. We fit interrupted time-series (ITS) models to monthly rate data using negative binomial regression, adjusted for age (<25, 25 to <35, ≥35 years) and self-reported race and ethnicity (Asian/Pacific Islander, Black, Hispanic, non-Hispanic White, or other or unknown), which were included because of the known age and race and ethnicity differences in the prevalence of prenatal cannabis use. The prepandemic period was defined as urine toxicology tests conducted from January 2019 to March 2020 and the pandemic period from April through December 2020 (see Laboratory Methods in the Supplement).

The rate ratio and corresponding 95% CIs are reported herein. We conducted the analyses using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). A 2-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Of 100 005 pregnancies (95 412 women), 26% were Asian or Pacific Islander; 7%, Black; 28%, Hispanic; 34%, non-Hispanic White; and 5%, other, unknown, or multiracial. The patients were a mean age of 31 years (median, 31 years). There were negligible differences in age or race and ethnicity in the 2 periods. During the pandemic, patients completed toxicology testing slightly earlier in their pregnancies (before pandemic mean, 8.51 weeks’ gestation; during pandemic mean, 8.04 weeks’ gestation).

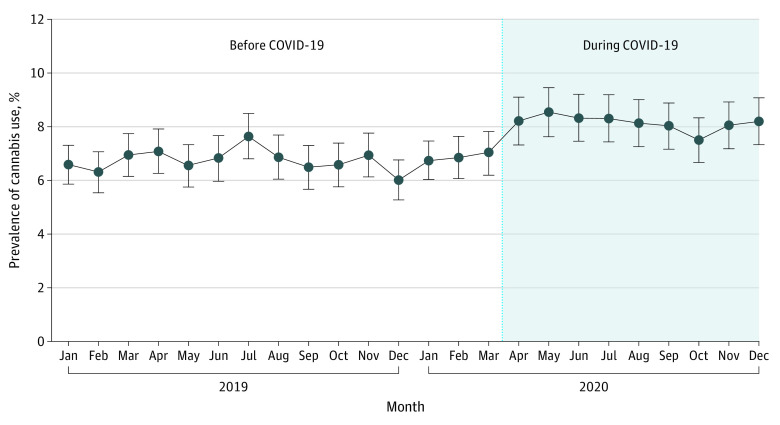

Before the pandemic, the standardized rate of prenatal cannabis use was 6.75% of pregnancies (95% CI, 6.55%-6.95%); that rate increased to 8.14% of pregnancies (95% CI, 7.85%-8.43%) during the pandemic (Figure). In the ITS analysis, we found that prenatal cannabis use increased by 25% (95% CI, 12%-40%; Table) during the pandemic over prenatal cannabis use during the 15 months before the pandemic. The ITS analysis confirmed that these rates before and during the pandemic were stable, with no statistically significant month-to-month trends (Table).

Figure. Monthly Trends in Cannabis Use During Pregnancy Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic (N = 100 005).

Prenatal cannabis use was based on a positive toxicology screening result conducted as part of standard prenatal care (≈8 weeks’ gestation) and includes 1 screening per pregnancy. All positive toxicology test results were confirmed by a laboratory test (see Laboratory Methods in the Supplement). The median monthly sample size in the months before COVID-19 was 4085 (range, 3655-5040), with a mean of 4189. The median monthly sample size in the months during COVID-19 was 4124 (range, 3932-4356), with a mean of 4130. Error bars indicate 95% CIs of the standardized rates.

Table. Change in Percentage of Cannabis Use During Pregnancy After the Start of the Pandemica.

| Interrupted time-series model variables | Rate ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjustedb | |

| Pre–COVID-19 expected trendc | 1.001 (0.994-1.008) | 1.001 (0.993-1.008) |

| COVID-19 shift | 1.268 (1.145-1.405)d | 1.251 (1.120-1.397)d |

| COVID-19 change in trend | 0.989 (0.973-1.006) | 0.992 (0.975-1.010) |

See the Methods section for the prepandemic period definition.

Adjusted for age (<25, 25 to <35, and ≥35 years) and self-reported race and ethnicity from the electronic health record (see the Methods section definition for race and ethnicity).

See Laboratory Methods in the Supplement for determination of prenatal cannabis use.

Significant at P < .05.

Discussion

Rates of biochemically verified prenatal cannabis use increased significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic among pregnant women in Northern California. Results are consistent with the rise in cannabis sales seen in California during the same period.5 When the toll of the COVID-19 pandemic begins to fade and restrictions are lifted, it is unknown whether pandemic-related increases in rates of cannabis use during pregnancy will reverse or remain elevated. Continued monitoring of trends is critical as the pandemic continues to evolve.

This study is limited to pregnant women universally screened in the KPNC system for prenatal cannabis use via urine toxicology testing early in pregnancy (≈8 weeks’ gestation) as part of standard prenatal care, and data do not reflect continued use throughout pregnancy. In some cases, positive toxicology test results may detect prenatal cannabis use that occurred prior to pregnancy recognition. Additional studies that capture pandemic-related changes in frequency of and reasons for cannabis use during pregnancy and among nonpregnant women are also needed.

Prenatal cannabis use is associated with health risks, including low infant birth weight and potential effects on offspring neurodevelopment.6 Clinicians should educate pregnant women about the harms of prenatal cannabis use, support women to quit, and provide resources for stress reduction.

Section Editors: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor; Kristin Walter, MD, Associate Editor.

eAppendix. Laboratory Methods

References

- 1.Volkow ND, Han B, Compton WM, McCance-Katz EF. Self-reported medical and nonmedical cannabis use among pregnant women in the United States. JAMA. 2019;322(2):167-169. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.7982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ko JY, Coy KC, Haight SC, et al. Characteristics of marijuana use during pregnancy—eight states, Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(32):1058-1063. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davenport MH, Meyer S, Meah VL, Strynadka MC, Khurana R. Moms are not OK: COVID-19 and maternal mental health. Front Glob Womens Health. 2020;1:1. doi: 10.3389/fgwh.2020.00001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Basu A, Kim HH, Basaldua R, et al. A cross-national study of factors associated with women’s perinatal mental health and wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One. 2021;16(4):e0249780. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0249780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.California Department of Tax and Fee Administration . Cannabis tax revenues. Accessed July 29, 2021. https://www.cdtfa.ca.gov/dataportal/dataset.htm?url=CannabisTaxRevenues

- 6.Committee on Obstetric Practice . Committee opinion No. 722: marijuana use during pregnancy and lactation. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(4):e205-e209. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. Laboratory Methods