Abstract

BACKGROUND:

To evaluate the feasibility of a protocol using combined magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), clinical data, and electroencephalogram (EEG) to identify neonates with mild neonatal encephalopathy (NE) treated with therapeutic hypothermia (TH) who are eligible for “early exit”.

METHODS:

Retrospective chart review of TH cases at a single Level III NICU over a 5-year period was used to describe the demographic, clinical, and outcome data in neonates that received early exit in contrast to 72 hour TH treatment.

RESULTS:

Two hundred and eight TH cases, including 18 early exit cases (9%) and 9 cases (4%) evaluated for early exit with MRI but continued on 72 hours of TH, were identified. Early exit and 72 hour treatment groups did not differ in demographics or cord gas measures, although early exit neonates had a shorter length of stay (p < 0.05). Consistent with the early exit protocol, no early exit infants had evidence of moderate or severe encephalopathy on EEG or evidence of hypoxic ischemic injury on MRI at 24 hours of life. Neurology follow up between age 1 and 18 months was available for 10 early exit infants, 8 of whom had a normal examination.

CONCLUSIONS:

Early MRI at 24 hours of age, alongside clinical and EEG criteria, is feasible as part of a protocol to identify neonates eligible for early exit from therapeutic hypothermia.

Keywords: Neonatal encephalopathy, hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, therapeutic hypothermia, early exit

1. Introduction

Therapeutic hypothermia (TH) is the standard of care for treating neonatal encephalopathy (NE) [1, 2]. The randomized controlled trials (RCTs) which established the beneficial impact of 72 hours of TH on risk of death and disability were limited to neonates with moderate and severe encephalopathy [3–5]. In contrast, there is a lack of evidence about the benefit of TH for neonates with mild encephalopathy. Historically, these patients were predicted to have good outcomes without treatment, making the potential risks associated with TH unappealing [6, 7]. However, recent studies have shown that up to half of neonates with only mild encephalopathy in the first six hours after birth have abnormalities on neonatal MRI or discharge exam, and are at a higher risk for adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes compared to normal term neonates [8–14].

As hypothermia for NE has been widely adopted and its safety well established, many institutions offering this therapy have broadened their indications to include neonates with milder forms of NE [15]. However, factors such as effects of maternal medications on neonatal arousal state can make the diagnosis of mild encephalopathy in the first six hours after birth challenging. Thus, there is a need for a pathway for ongoing evaluation of these infants with the possibility of early exit from TH if hypoxic ischemic (HI) injury is unlikely.

At our institution, inclusion criteria for TH have been expanded to include patients with less severe evidence of perinatal insult and with mild NE. Some patients with mild NE are started on TH in the presence of equivocal evidence of a perinatal insult. These infants are considered for early rewarming if their neurological examination and EEG normalize during the first 12–24 hours of TH and an MRI at 24 hours demonstrates no evidence of HI injury. We hypothesized that the use of early MRI at 24 hours of age would help identify a subset of neonates that despite an initial exam consistent with mild encephalopathy, did not have evidence of HI cerebral injury. These neonates are likely to have little benefit from TH and may be exposed to additional risks from the 72 hours of TH. To explore the hypothesis that there is a subgroup of infants evaluated for encephalopathy whose EEG and exam quickly normalize and do not exhibit evidence of HI on MRI at 24 hours of age, we retrospectively reviewed the early exit cases from our institution from 2014–2018 to describe their clinical characteristics, hospital course, MRI findings, and short-term outcome.

2. Methods

All neonates admitted to the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Level III NICU who underwent TH between 2014 and 2018 were retrospectively reviewed. This project was approved by the Partners Healthcare System/Brigham and Women’s Hospital IRB and the Boston Children’s Hospital IRB.

The criteria for therapeutic hypothermia in our center are modified center-based criteria, which have been broadened from those used in the RCTs. The adaptations have included: (1) decreasing the gestational age criterion to ≥34 weeks gestation, (2) increasing the inclusion pH from ≤7.0 to ≤7.1; (3) reducing the base excess for inclusion from ≤–16 mEq/L to ≤–10 mEq/L, and (4) providing TH to neonates with mild encephalopathy determined with a scoring system sensitive to subtle changes on clinical examination. This scoring system assesses the severity of encephalopathy utilizing the nine domain scoring system of the Iberoamerican Society of Neonatology (SIBEN) [16]. While the composite score (sum of scores from all domains) ranges from 0–27, a score of 4 is used as a threshold to consider TH.

The criteria used for early exit from TH are: normalization of the neurologic exam, normal or mildly abnormal continuous EEG (cEEG), and MRI without evidence of HI injury at 24 hours of age. cEEG is performed on all neonates undergoing TH and is considered mildly abnormal in the presence of mild excessive discontinuity or multifocal sharp waves. MRI is typically performed after rewarming but is performed at 24 hours in this early exit group if patients fulfil the other two criteria i.e. neurological exam and cEEG. After the MRI exam, early exit is determined by agreement between the Neurology and Neonatology teams that HI injury is unlikely, and that early rewarming should be performed.

Demographic, clinical, and outcome data were extracted from the electronic medical record and entered in the REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at our institution [17]. This database was used to identify all TH cases between 2014 and 2018. Neonates were excluded from the study if they were transferred to another hospital or if the family redirected care to comfort care only prior to 72 hours of age. The database was queried for information related to demographics (gestational age, sex), delivery (birth weight, 1, 5, and 10 min Apgar scores, resuscitation required, and cord gases, when available), and hospital course (hours cooled, reason for discontinuation of hypothermia if <72 hours, length of stay). Age at MRI was collected and used, in combination with other clinical documentation, to identify infants who were considered for early exit, but continued for 72 hours of TH treatment. Additional clinical data (EEG result, MRI result, discharge exam, exam at well child or Neurology Clinic follow up visits) were collected for infants in the early exit group and for infants who were evaluated for early exit, but continued for 72 hours of TH. In the case of missing data in the database, the electronic medical record was reviewed to complete data collection. The early exit group was compared to all patients who received a full course of TH during the same study period (“complete protocol”) as well as the subset of complete protocol infants who were evaluated for early exit with early MRI at 24 hours after birth, but continued on 72 hours of TH (“early exit evaluation only”). All comparisons were made using a two-sided Student t-test for continuous variables or Fisher exact test for categorical variables.

3. Results

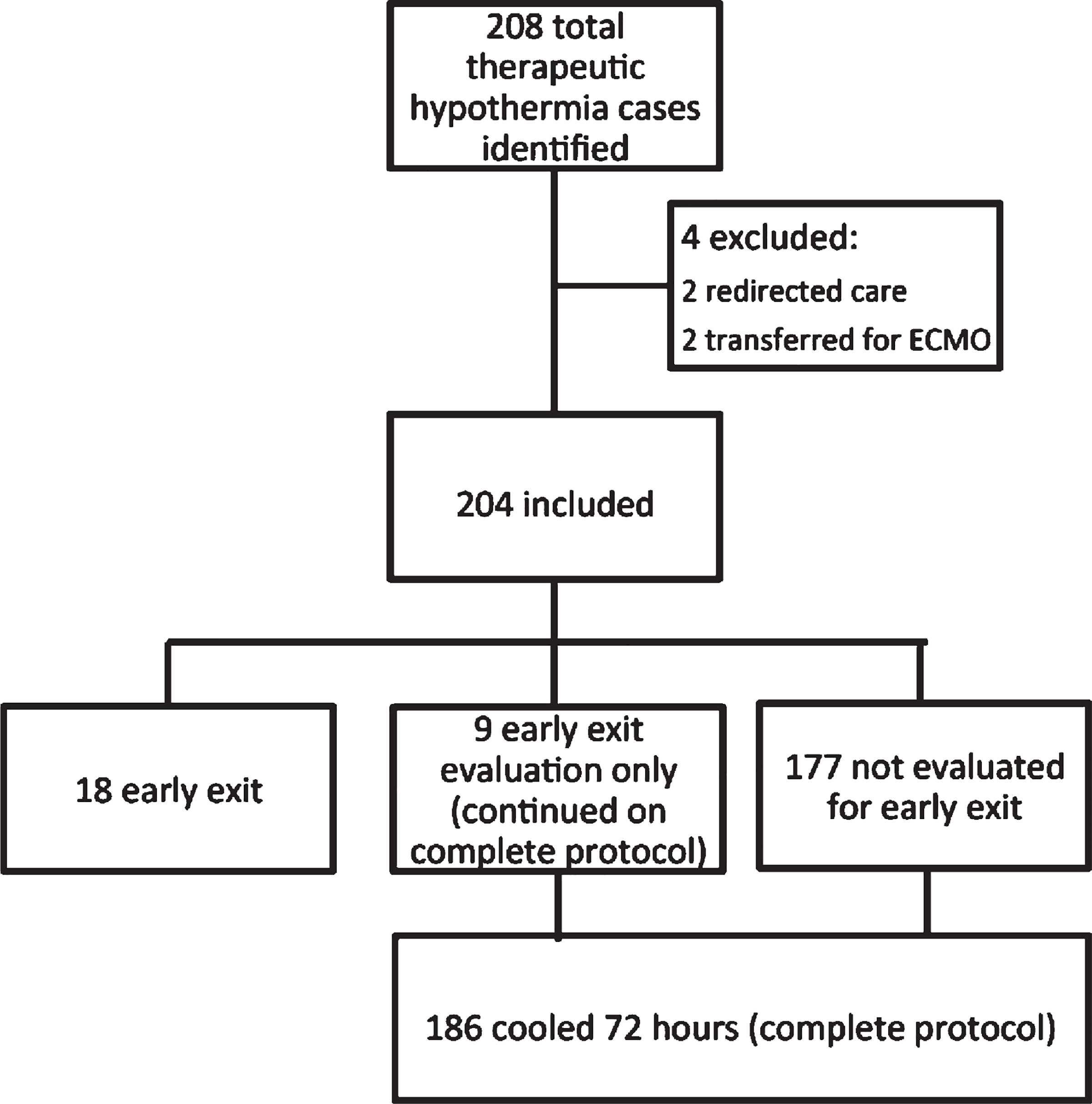

Two hundred and eight TH cases were identified between 2014 and 2018 (Fig. 1). Four cases were excluded from the study due to transfer or redirection of care prior to 72 hours after birth. Of the remaining 204 cases included in the study, 186 neonates (91%) were cooled for 72 hours (referred to as “complete protocol”), 18 neonates (9%) were rewarmed early at 24–48 hours due to the decision to utilize the early exit protocol (referred to as “early exit”). Within the complete protocol group, 9 neonates were evaluated for early exit, but ultimately were continued on 72 hours of TH (4% of total, referred to as “early exit evaluation only”). Thus, in total, 27 neonates (13% of total) were evaluated for early exit from TH (18 who did early exit and nine who did not and completed 72 hours of hypothermia). The mean active cooling duration in the early exit group was 32.4 hours compared to the complete protocol group in which the mean active cooling duration was 72.2 hours (p < 0.0001). The patients in the complete protocol and early exit groups did not have statistically significant differences in gestational age, birth weight, sex, inborn status, or cord gas measures (Table 1). There was a trend towards increased need for positive pressure ventilation (PPV) and intubation as well as lower APGAR scores at all time points in the complete protocol group, although these differences did not reach statistical significance. Seizures were detected in 24% of the complete protocol group, while none of the early exit group had seizures (electrical or clinical). Length of stay was significantly longer in the complete protocol group compared to the early exit group (11.1 vs 6.2 days, p < 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Study population profile.

Table 1.

Study demographics

| Early Exit (n = 18) | Complete protocol (n =186) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Gestational Age (weeks) | 39.5 (1.2) | 38.9(1.7) | 0.18 |

| Birth weight (g) | 3394 (452) | 31762(534) | 0.09 |

| Female | 8(44) | 78 (42) | 1 |

| Inborn | 11(61) | 119(64) | 0.8 |

| 1 min Apgar | 3(2–5) | 2 (1–4) | 0.13 |

| 5 min Apgar | 8 (4–8) | 6 (5–7) | 0.5 |

| 10 min Apgar | 8 (6–9) | 7 (6–8) | 0.28 |

| Resuscitation | |||

| PPV | 12 (67) | 153 (82) | 0.12 |

| Intubation | 2(11) | 51 (27) | 0.16 |

| Chest compressions | 3(17) | 13(7) | 0.15 |

| UA cord gas (n) | 11 | 135 | |

| pH | 7.04 (0.09) | 6.96 (0.85) | 0.76 |

| BE | −11.5(1.9) | −11.6 (4.8) | 0.96 |

| UV cord gas (n) | 14 | 150 | |

| pH | 7.12(0.13) | 7.12(0.15) | 0.6 |

| BE | −9.4 (2.9) | −10.16(4.5) | 0.99 |

| Hours cooled | 32.4 (7.9) | 72.2 (0.9) | <0.0001 |

| Seizure (electric or clinical) | 0(0) | 24 (13) | 0.13 |

| MRI result normal | 14 (78) | 71 (39) | 0.002 |

| Length of stay (days) | 6.2 (3.4) | 11.1 (7.6) | <0.05 |

Data displayed as mean (standard deviation), n (%), or median (IQR). UV, umbilical vein; UA umbilical artery; BE, base excess.

The characteristics of the 18 early exit cases are presented in Table 2. None of the early exit patients had clear evidence of HI injury on MRI, and 78% of MRIs (14/18) were described as normal. Three of the four neonates with abnormal MRI scans had evidence of intracranial hemorrhage, such as subdural hematoma, subarachnoid hemorrhage, intraventricular haemorrhage (IVH), and parenchymal hemorrhage. These neonates had normal coagulation studies. The fourth neonate had a small IVH, and a slightly linear signal abnormality in the left periatrial white matter which was not felt to be a result of HI injury by the radiologist and neurologist involved in the case.

Table 2.

Individual characteristics and early outcomes for “early exit” neonates

| Case | cEEG | MRI Findings | Discharge Exam | Length of Stay | Follow up Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Excess multifocal sharp waves and excess discontinuity consistent with mild encephalopathy | Normal | Normal | 4 | 12 mo neuro visit: normal |

| 2 | Mild excess of sharp multifocal waves consistent with mild encephalopathy | Small right cerebral hemorrhage, mild IVH, diffuse subarachnoid and small subdural hemorrhage | Normal | 5 | 3 mo neuro visit: mild proximal muscle weakness and mild hypertonia |

| 3 | Normal | Normal | Normal | 6 | 14 mo neuro visit: normal |

| 4 | Mild excessive discontinuity for age suggestive of mild dismaturity or mild encephalopathy | Normal | Normal | 6 | 1 mo neuro visit: normal |

| 5 | Excessive multifocal sharp waves suggestive of diffuse encephalopathy | Normal | Normal | 4 | 5 mo neuro visit: normal |

| 6 | No cEEG available. aEEG normal. | Small IVH, slightly linear signal abnormality in the left periatrial white matter | Normal | 8 | 2 mo neuro visit: normal |

| 7 | Rare mild excess discontinuity suggestive of a mild encephalopathy | Subdural hematoma, subarachnoid blood, small IVH, a right temporal lobe hemorrhage, scattered small parenchymal hemorrhages in cerebellum and right frontal lobe | Normal | 5 | 18 mo neuro visit: normal |

| 8 | Normal | Normal | Normal | 4 | None available |

| 9 | Initially mild discontinuity for age, normal during cooling | Normal | Normal | 15 | None available |

| 10 | Normal | Normal | Normal | 6 | None available |

| 11 | DOL 0: Mild excess discontinuity consistent with mild encephalopathy. DOL 1: Normal. | Normal | Hypertonic | 4 | 2 mo neuro visit: mild appendicular spasticity and mild proximal muscle weakness |

| 12 | Excessive multifocal sharp waves for age suggestive of mild encephalopathy | Normal | Normal | 4 | None available |

| 13 | Normal | Normal | Normal | 5 | 3 mo neuro visit: normal |

| 14 | Normal | Normal | Normal | 15 | None available |

| 15 | Normal | Normal | Normal | 7 | 18 mo WCC: No developmental concerns |

| 16 | Normal | Normal | Normal | 5 | None available |

| 17 | No cEEG available. aEEG Normal. | Normal | Mildly increased tone in neck | 4 | Evaluated in Developmental Medicine Clinic for language delay at 23 mo and diagnosed with autism |

| 18 | Excessive multifocal sharp transients and excessive discontinuity in quiet sleep consistent with mild encephalopathy | Two punctate foci of susceptibility within the centrum semiovale likely reflecting microhemorrhage of uncertain etiology. | Normal | 4 | 2 mo neuro visit: normal |

cEEG, continuous electroencephalography; aEEG, amplitude intergrated electroencephalography; IVH, interventricular hemorrhage; mo, month; WCC, well child check.

Two of the early exit neonates had abnormal discharge exams, specifically in the form of hypertonicity. Their exams had been considered normal at the time the decision was made to terminate TH.

Sixteen neonates had full cEEG results available in the electronic medical record. Of these, 44% were interpreted as normal, and 56% as consistent with mild encephalopathy (for example, excessive discontinuity or multifocal sharp waves). No neonates had EEG abnormalities interpreted as consistent with moderate or severe encephalopathy.

Neurology Clinic follow up data were available for ten of the infants (age at follow up 1–18 months), and an additional two infants had other follow up data available (well child exam or Developmental Medicine Clinic). Eight of the ten infants with Neurology Clinic follow up had normal exams at their most recent visit. Of the two infants with abnormal exams, one infant (Case 2) was three months old at the time of the most recent visit and had had multiple intracranial hemorrhages noted on MRI. The other (Case 11) was two months of age at the time of the most recent visit, had had a normal neonatal MRI, but an abnormal NICU discharge exam. These two infants both had mild abnormalities on the neurological exam. One patient (Case 17), who had a normal MRI and amplitude integrated electroencephalography (aEEG), but mildly increased tone at discharge, did not have early follow up in Neurology Clinic. However, this child was evaluated in the Developmental Medicine Clinic for language delay at 23 months of age and diagnosed with autism. An additional infant had well child follow up visits available and had no developmental concerns or neurologic abnormalities noted.

Nine neonates during the study period were evaluated for early exit with MRI at 24 hours of age, due to normalization of the clinical examination and EEG, but ultimately were determined to receive 72 hours of TH (Table 3). Of these nine neonates, seven had evidence of possible HI injury on MRI. MRI findings included areas of T2 hyperintensity in the white matter with or without restricted diffusion (n = 3), areas of restricted diffusion (n = 4), and lactate peak on magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) (n = 1). An eighth neonate had an MRI which was preliminarily read as consistent with HI injury, but on final interpretation was not considered as consistent with HI injury. At the time of the final interpretation, the neonate had already completed 48 hours of TH and was continued for the remainder of the planned 72 hours. The ninth neonate’s MRI did not show HI injury, but there was concern for ongoing abnormalities on serial neurologic exam and the neonate was not exited early. When compared to the early exit neonates, the neonates evaluated for early exit and continued on TH had more abnormalities on discharge exam (p < 0.05). They also had longer lengths of stay (p < 0.05). Of those with available neurology clinic data, 3/6 (50%) of the neonates evaluated for early exit had an abnormal exam at follow up evaluation compared to 2/10 (20%) of the early exit group, but this difference did not reach statistical significance.

Table 3.

Clinical characteristics and early outcomes for “early exit” neonates and neonates evaluated for early exit

| Early exit (n =18) | Evaluated for early exit, completed full protocol (n = 9) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| cEEG mild encephalopathy | 56% (9/16) | 67% (6/9) | 0.69 |

| Discharge exam abnormal | 11% (2/18) | 67% (6/9) | <0.05 |

| Length of stay | 6.2 (3.4) | 9 (3.2) | <0.05 |

| Neurology follow up exam abnormal | 20% (2/10) | 50% (3/6) | 0.29 |

Data displayed as mean (standard deviation), or % (n/total patients data available for). cEEG, continuous electroencephalography; aEEG, amplitude intergrated electroencephalography.

4. Discussion

This analysis of a single institution’s experience with an early exit protocol using the criteria of normalized exam, normal or nearly normal EEG, and MRI without evidence of HI injury, showed that approximately one in ten cooled neonates met criteria for early exit. These neonates were more likely to have a normal neurologic exam at the NICU discharge and shorter length of stay than neonates evaluated for early exit but ultimately continued on TH for 72 hours. As many centers expand their inclusion criteria for TH to include neonates with mild encephalopathy or less definitive evidence of HI insult, it is important to develop optimal criteria to accurately identify and treat neonates who are likely to benefit from this treatment, while minimizing cost and potential harm.

Although there has been little published about outcomes for neonates who were exited early from TH, this practice is not uncommon. A survey of centers in the UK revealed that 75% of hospitals offered cooling to neonates with mild encephalopathy and that 36% of centers would consider discontinuing cooling after less than 72 hours of treatment [18]. This is consistent with a recent Neonatal Neurocritical Care Special Interest Group Survey, which reported that 43% of centers exit some neonates early from TH (www.NNCC-SIG.org). However, in that survey, Brigham and Women’s Hospital was the only institution using MRI prior to rewarming as part of their early exit criteria (as opposed to the combination of exam and EEG alone). A previous study of neonates with mild encephalopathy who were initially cooled, but exited the TH protocol early due to rapid clinical improvement (ten neonates, mean cooling time nine hours) found that 50% of neonates had an abnormal MRI within two weeks and that two of the ten neonates, both of whom had abnormalities on MRI, had abnormal neurodevelopmental testing at two years of age [19]. These data, as well as the known predictive value of MRI for neurodevelopmental outcome when completed at two to six days after birth, suggest that MRI may improve patient selection compared with protocols using physical exam alone [20]. However, it is important to note that early MRI at 24 hours after birth, as in our approach, may be less sensitive than MRI at later time points in identifying HI injury. Undertaking MRI during cooling has been described previously, including the feasibility of maintaining temperatures within the therapeutic range during transport and MRI [21]. Our study supports the feasibility of early MRI during cooling as a routine NICU practice and suggests that the imaging may assist in detecting a cerebral insult or injury that may warrant completing 72 hours of hypothermia therapy. In our cohort, out of the 27 neonates who underwent MRI at 24 hours of life (early exit and early exit evaluation only), nearly one third of them completed the full 72 hours of TH.

This study has a number of limitations. Although the findings suggest that it is feasible to use early MRI during TH as part of an early exit protocol, which also includes exam and EEG, the retrospective nature of this study, limited follow up, young age at follow up, and small cohort size preclude conclusions about the effects of this practice on long term outcomes. In addition, it is important to note that the mean duration of cooling for early exit neonates was not trivial (32 hours), and although our protocol is intended to identify neonates who do not have HI injury and therefore will not benefit from TH, we cannot rule out the possibility that the early exit infants experienced some benefit from the duration of TH they received. However, we report our initially positive experience with an early exit protocol to highlight the need for more studies with longer and more detailed follow up for neurodevelopmental outcome to fully evaluate the safety of early exit from TH. A cost-effectiveness evaluation could be conducted concurrently as we hypothesize that a shorter duration of cooling for select neonates will result in shorter hospitalization stays and decreased costs without an associated increase in neurological disability.

Footnotes

Disclosure statements

Drs. White, Grant, Soul, Inder, and El-Dib have no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures.

References

- [1].Jacobs SE, Berg M, Hunt R, Tarnow-Mordi WO, Inder TE, Davis PG. Cooling for newborns with hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;1:CD003311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Committee on Fetus and Newborn, Papile LA, Baley JE, Benitz W, Cummings J, et al. Hypothermia and neonatal encephalopathy. Pediatrics. 2014;133(6):1146–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Gluckman PD, Wyatt JS, Azzopardi D, Ballard R, Edwards AD, Ferriero DM, et al. Selective head cooling with mild systemic hypothermia after neonatal encephalopathy: multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2005;365(9460):663–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Azzopardi D, Brocklehurst P, Edwards D, Halliday H, Levene M, Thoresen M, et al. The TOBY study. Whole body hypothermia for the treatment of perinatal asphyxial encephalopathy: A randomised controlled trial. BMC Pediatr. 2008;8:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Shankaran S, Laptook AR, Ehrenkranz RA, Tyson JE, McDonald SA, Donovan EF, et al. Whole-body hypothermia for neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(15):1574–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Finer NN, Robertson CM, Peters KL, Coward JH. Factors affecting outcome in hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy in term infants. Am J Dis Child. 1983;137(1):21–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Robertson CM, Finer NN, Grace MG. School performance of survivors of neonatal encephalopathy associated with birth asphyxia at term. J Pediatr. 1989;114(5):753–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Murray DM, O’Connor CM, Ryan CA, Korotchikova I, Boylan GB. Early EEG grade and outcome at 5 years after mild neonatal hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. Pediatrics. 2016;138(4):e20160659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Walsh BH, Neil J, Morey J, Yang E, Silvera MV, Inder TE, et al. The frequency and severity of magnetic resonance imaging abnormalities in infants with mild neonatal encephalopathy. J Pediatr. 2017;187:26–33.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Conway JM, Walsh BH, Boylan GB, Murray DM. Mild hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy and long term neurodevelopmental outcome - A systematic review. Early Hum Dev. 2018;120:80–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Prempunpong C, Chalak LF, Garfinkle J, Shah B, Kalra V, Rollins N, et al. Prospective research on infants with mild encephalopathy: the PRIME study. J Perinatol. 2018;38(1):80–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Chalak LF, Nguyen KA, Prempunpong C, Heyne R, Thayyil S, Shankaran S, et al. Prospective research in infants with mild encephalopathy identified in the first six hours of life: Neurodevelopmental outcomes at 18–22 months. Pediatr Res. 2018;84(6):861–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Finder M, Boylan GB, Twomey D, Ahearne C, Murray DM, Hallberg B. Two-year neurodevelopmental outcomes after mild hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy in the era of therapeutic hypothermia. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(1):48–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Rao R, Trivedi S, Distler A, Liao S, Vesoulis Z, Smyser C, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcomes in neonates with mild hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy treated with therapeutic hypothermia. Am J Perinatol. 2019;36(13):1337–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].El-Dib M, Inder TE, Chalak LF, Massaro AN, Thoresen M, Gunn AJ. Should therapeutic hypothermia be offered to babies with mild neonatal encephalopathy in the first 6 h after birth? Pediatr Res. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Perez JM, Golombek SG, Sola A. Clinical hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy score of the Iberoamerican Society of Neonatology (Siben): A new proposal for diagnosis and management. Revista da Associacao Medica Brasileira (1992). 2017;63(1):64–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)-A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Oliveira V, Singhvi DP, Montaldo P, Lally PJ, Mendoza J, Manerkar S, et al. Therapeutic hypothermia in mild neonatal encephalopathy: A national survey of practice in the UK. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2018;103(4):F388–f90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Lally PJ, Montaldo P, Oliveira V, Swamy RS, Soe A, Shankaran S, et al. Residual brain injury after early discontinuation of cooling therapy in mild neonatal encephalopathy. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2018;103(4):F383–f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Trivedi SB, Vesoulis ZA, Rao R, Liao SM, Shimony JS, McKinstry RC, et al. A validated clinical MRI injury scoring system in neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Pediatr Radiol. 2017;47(11):1491–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Wu TW, McLean C, Friedlich P, Grimm J, Bluml S, Seri I. Maintenance of whole-body therapeutic hypothermia during patient transport and magnetic resonance imaging. Pediatr Radiol. 2014;44(5):613–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]