Abstract

Around the world, one in four children live in a country affected by conflict, political insecurity and disaster. Healthcare in humanitarian and fragile settings is challenging and complex to provide, particularly for children. Furthermore, there is a distinct lack of medical literature from humanitarian settings to guide best practice in such specific and resource-limited contexts. In light of these challenges, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), an international medical humanitarian organisation, created the MSF Paediatric Days with the aim of uniting field staff, policymakers and academia to exchange ideas, align efforts, inspire and share frontline research and experiences to advance humanitarian paediatric and neonatal care. This 2-day event takes place regularly since 2016. The fourth edition of the MSF Paediatric Days in April 2021 covered five main topics: essential newborn care, community-based models of care, paediatric tuberculosis, antimicrobial resistance in neonatal and paediatric care and the collateral damage of COVID-19 on child health. In addition, eight virtual stands from internal MSF initiatives and external MSF collaborating partners were available, and 49 poster communications and five inspiring short talks referred to as ‘PAEDTalks’ were presented. In conclusion, the MSF Paediatric Days serves as a unique forum to advance knowledge on humanitarian paediatrics and creates opportunities for individual and collective learning, as well as networking spaces for interaction and exchange of ideas.

Keywords: neonatology

Key messages.

What is known about the subject?

One in four children worldwide are living in a humanitarian or fragile setting.

There is a distinct lack of medical literature from humanitarian settings to provide guidance on best practice in such specific and resource-limited contexts.

Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) Paediatric Days was born to address paediatric issues of direct humanitarian concern.

What this review adds?

This event unites frontline staff, policymakers and academia to exchange ideas, align efforts, inspire and share frontline research and experiences.

Essential newborn care, community-based models of care, paediatric tuberculosis, antimicrobial resistance and collateral damage of COVID-19 on child health were discussed at the 2021 event.

MSF Paediatric Days is as a unique forum to advance knowledge on humanitarian paediatrics and creates opportunities for individual and collective learning.

Introduction

Around the world, one in four children are living in a country affected by conflict, political insecurity and disaster, and an unprecedented 30–34 million children are displaced from home.1 Children are disproportionately impacted by crises and face the threat of violence, hunger, disease, disability and death. Worldwide, 56 million children under the age of 5 (half of them newborns) are projected to die between 2018 and 2030 in the absence of additional action, with the greatest proportion of this mortality anticipated in humanitarian and fragile settings.2 Tragically, with a historic reversal of progress expected due to the collateral impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, a rising gap between humanitarian needs and funding3 and declining support for child health in many cases, the number of children dying is expected to increase even further.4 In addition to increased mortality, we can expect escalating suffering, lost future potential and increasing inequality.5–7

Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders/MSF) is an international medical humanitarian organisation specialising in responding to humanitarian emergencies such as conflicts, natural disasters and epidemics, acting with independence, neutrality and impartiality. MSF provides essential medical care to millions of children every year who would otherwise be without access to healthcare (see table 1).8

Table 1.

MSF paediatric activities involving children under 5 years old in 20198

| Description | n (rounded to closest whole) |

| Projects providing paediatric care | 270 |

| Children receiving outpatient care | 3.3 million |

| Children receiving inpatient care unrelated to severe malnutrition | 361 000 |

| Children admitted to therapeutic feeding centres | 186 000 |

| Births supported | 300 000 |

MSF, Médecins Sans Frontières.

Healthcare in humanitarian and fragile contexts is challenging and complex to provide, particularly for children. Healthcare staff are scarce, under-resourced and work well over capacity in some of the most insecure and adverse settings. Yet they continue to provide essential and life-saving services to vulnerable populations, rarely receiving the recognition they deserve. In addition, there is a distinct lack of medical literature from humanitarian settings to provide guidance on best practices in such specific and resource-limited contexts. There is a need to further integrate evidence-based practices into humanitarian contexts, and to generate evidence on what works best. We need to shine a brighter light on the experiences, challenges, failures and successes of those working in ‘humanitarian paediatrics’ (box 1) in order to improve care for this growing population of children in the most vulnerable circumstances.

Box 1. Humanitarian paediatrics.

Humanitarian paediatrics refers to the branch of medicine that involves the care of newborns, infants, children and adolescents in humanitarian settings. It takes elements from public and global health, paediatrics, tropical and disaster medicine. It is centred on the child and his family and integrates the specific challenges and barriers related to the humanitarian context and limited resources.

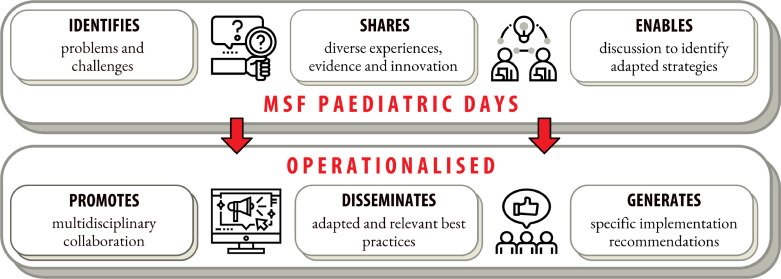

There are not many platforms or venues available to bridge the existing gaps in clinical research and medical literature applicable to paediatric and neonatal care in humanitarian and fragile settings. Therefore, in 2016, the first MSF Paediatric Days was born with the aim of addressing urgent paediatric issues of direct humanitarian concern. Since then, three more editions have taken place at 18-month intervals, successfully uniting frontline staff working in MSF and other organisations with policymakers and academia to exchange ideas, align efforts, inspire and share pertinent research and experiences. This event aims to raise awareness and exchange experiences, and to impact daily paediatric medical activities in humanitarian settings by promoting multidisciplinary collaboration, disseminating relevant best practices and generating specific recommendations (figure 1).

Figure 1.

The MSF Paediatric Days approach to improving paediatric care in humanitarian settings. MSF, Médecins Sans Frontières.

In April 2021, the first virtual edition of the MSF Paediatric Days brought together 1108 people from 95 different countries. MSF staff made up 58% of the attendees, largely frontline health workers, and the remainder came from a range of different organisations including academia, non-governmental organisations, ministries of health and other actors. The event included five main plenary discussions around key topics on humanitarian paediatrics, and eight virtual stands from internal MSF initiatives (MSF eCARE: electronic Decision Support System for paediatric primary care, Telemedicine: online tool for MSF medical frontline staff that provides access to specialised medical advice, point-of-care ultrasound) and external MSF collaborating partners (OPENPediatrics, Save the Children, WHO, Laerdal and the American Academy of Pediatrics, Action Against Hunger, Alliance for International Medical Action and the Société Sénégalaise de Pédiatrie) who shared content and interacted with the participants. Additionally, 49 posters (available on ResearchGate) and 21 video abstracts were displayed, offering evidence directly from hospitals and medical projects in fragile and humanitarian settings. This event provided a unique opportunity for frontline health staff working in such settings to share their experiences, challenges and solutions, in addition to creating networking spaces for interaction and exchange of ideas. Moreover, five inspiring short ‘PAEDTalks’ enriched the content of the event.

During this 2-day event on 15–16 April, five major themes were discussed: essential newborn care, community-based models of care, paediatric tuberculosis (TB), antimicrobial resistance in neonatal and paediatric care, and the collateral damage of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on child health. Replays and full event content can be found on the MSF Paediatric Days web page.

Newborn care: back to basics

Newborns are one of the most vulnerable groups in humanitarian and fragile settings, but they have received limited focus in humanitarian action.9 The first session entitled ‘Neonates - back to basics’ illustrated the challenges that field teams face to implement, maintain, support and promote essential newborn care, with a focus on breastfeeding. Breastfeeding has well-recognised health benefits for mothers and newborns, but is even more crucial in humanitarian settings where breast milk substitutes are particularly dangerous in the absence of adequate water, sanitation and hygiene.10 11 Nevertheless, the life-saving nature of breastfeeding has often been overlooked in humanitarian settings, with a lack of institutionalised guidance on supporting breastfeeding.12 The session identified numerous barriers to successful breastfeeding, such as false assumptions of breastfeeding being easy without need for support, contradictory messaging and failure to maintain mothers and babies together (mother–baby dyad care) due to lack of adequate space, resources and staff knowledge and awareness. Moreover, gender inequity and female disempowerment, which are exacerbated in crises, also negatively influence breastfeeding practices in many of the contexts where MSF intervenes.

There was a common recognition of the need for breastfeeding promotion and awareness raising among health staff, mothers and communities, including the need for professionals with expertise in breastfeeding promotion to support humanitarian responses. Ultimately, breastfeeding support needs to be recognised as an emergency humanitarian intervention. Different solutions and ideas were shared during the panel discussion to overcome some of these current challenges and to achieve this important shift in paradigm. Improving knowledge and skills on breastfeeding for healthcare providers is crucial, and support from lactation specialist should be made available via innovative platforms such as telemedicine. Engagement of all members of the community including traditional birth attendants, family (including male members) and any other key member of the community should be included in the community engagement strategy of the project. Key messages of this session can be found in table 2.

Table 2.

Newborn care: back to basics

| Key messages | Why is it important? | Current challenges | Recommendations |

| Breast feeding (BF) is an intervention that saves lives, improves health and development of newborns, as well as maternal well-being. BF should be universally and practically achieved with dedicated support in all MSF contexts. | Newborn mortality and morbidities remain high across MSF projects. Essential evidence-based interventions shown to decrease newborn mortality such as exclusive and early BF should be supported and scaled up to save lives across MSF. BF is natural, instinctive, ready made and vastly available. However, many women face different challenges to establish and sustain BF. To overcome those challenges, a coordinated and multidisciplinary support should be available for every woman and their baby. |

|

Field

Operations

Headquarters

|

| A family-centred approach, which includes an understanding of the community and the context, is needed to ensure successful BF. | To effectively support mothers, we need to understand the barriers and enablers related to a specific context. The mother–baby dyad is at the centre of the process, but all the family and community need to participate, support, encourage. |

|

Field

Operations

Research

|

BF, Breastfeeding; MSF, Médecins Sans Frontières.

Community-based models of care

The second session of the first day entitled ‘Community-based models of care for neonatal and child health’ provided insight on the current challenges and achievements of the decentralisation of care, and the important role that the community plays in the continuum of care. During the session, discussions highlighted the opportunity and importance of expanding community models of care for both children and newborns. Community health workers are crucial for delivering a range of preventive and curative health services, and for reducing inequities in access to care. It was highlighted that community activities should be built on existing capacity to avoid the implementation of parallel systems.

The integration of community-based models of care in emergency response is possible and most effective if the model is implemented in advance with standardised emergency preparedness strategies according to context, to promote resilience. Field testimonies from an Integrated Community Case Management programme in Niger and community-based nutrition programmes among others reinforced the importance, and the potential, that community models of care have in improving access and the continuum of care in children. See key messages of this session in table 3.

Table 3.

Community-based models of care in paediatrics

| Key messages | Why is it important? | Current challenges | Recommendations |

| Community models of care are effective in delivering a range of preventive, promotive and curative health services for children and neonates, and they can contribute to reducing inequities in access to care. | In humanitarian and fragile settings when access to health facilities is limited, care at community level can bridge important health gaps for mothers, newborns and children. The community-based activities are an essential part of the health system, contributing to build skills and confidence to empower people with knowledge, tools and understanding referral needs. |

|

Field

Operations

Headquarters

|

| Community models of care in emergency response are most effective if the model is implemented in advance with contextual emergency preparedness (EPREP) strategies. | Empowering the community in delivering healthcare increases resilience during crises when access to the health facilities may be further limited. |

|

Field/operations

HQ

|

CHW, Community health workers; EPREP, Emergency preparedness; HQ, Headquarters; M&E, Monitoring and Evaluation.

Paediatric TB

On the second day, three main topics where discussed. The first session, ‘Paediatric tuberculosis’, touched on the challenges of diagnosing TB, the specificities of paediatric TB and the role of contact tracing and preventive treatment.

TB is a major infectious killer in MSF settings and children, especially those under 5 years of age, are at particular risk of severe forms of the disease. Paediatric TB is a ‘silent disease’ frequently underdiagnosed, undertreated and under-reported. TB presents differently in children than in adults, with a higher proportion of extrapulmonary TB. Microbiological confirmation is rarely achievable in children and is especially challenging in humanitarian settings. Therefore, emphasis on clinical diagnosis is imperative to ensure that presumptive treatment is started without delay. Treatment of paediatric TB based on clinical diagnosis alone would decrease TB morbidity in children, thereby minimising preventable deaths from the disease.

Contact tracing of TB cases in the community and subsequent tuberculosis preventive treatment (TPT) is often overlooked and deprioritised in low-resource settings, but this should be pursued more actively. This can now be facilitated with new, shorter TPT regimens, which have already shown promising results in terms of acceptance, efficacy, safety and adherence to treatment within MSF settings. See key messages of the session in table 4.

Table 4.

Paediatric tuberculosis

| Key messages | Why is it important? | Current challenges | Recommendations |

| Underdiagnosis and undertreatment of paediatric tuberculosis (TB) lead to preventable deaths. Microbiological confirmation is rarely available in children, therefore at present, a clinical diagnosis should be used to start presumptive treatment without delay. |

TB remains a major, unrecognised killer in children. MSF has a possibility to make a difference now by increasing the knowledge of field teams who meet children or their caretakers. Presumptive and empirical TB treatment is safe, well tolerated and effective. Starting treatment based on clinical suspicion (not microbiology confirmation) will bridge the gap of underdiagnosis and undertreatment of TB in children in MSF projects. |

|

Field

Operations

Headquarters/research

|

| Tracing the contacts of patients with TB with the offer of tuberculosis preventive treatment (TPT) should be pursued as an effective strategy to save lives in MSF projects. | Contact tracing of patients with TB is an effective way to identify those who have active TB but also those who may be harbouring latent (sleeping) TB. More lives can be saved by improving access to timely treatment or TPT. New shorter drug regimens for TPT are showing promising results on acceptance, effectivity, safety and adherence to treatment. |

|

Field

Operations

HQ/working groups

|

HQ, Headquarters; MSF, Médecins Sans Frontières; TB, Tuberculosis; TPT, Tuberculosis preventive treatment.

Antimicrobial resistance and antimicrobial stewardship in neonatal and paediatric care

The second topic discussed on 16 April was ‘Antimicrobial resistance and antimicrobial stewardship in neonatal and paediatric care’. Antimicrobial resistance is a reality in humanitarian settings13 14 and has been described as a silent tsunami. Vulnerable groups such as newborns and malnourished children face a disproportionate burden and specific challenges. The challenges and consequences of outbreaks in neonatal units in low-resource settings were highlighted, including both experience within MSF and growing evidence based in low-resource settings outside MSF.15 16 In addition, MSF field experiences from Mali and South Sudan underlined the need for a multidisciplinary approach focusing on several transversal pillars including infection prevention and control (IPC), antibiotic stewardship and microbiology (when possible or available). Antibiotic stewardship is particularly challenging for paediatric patients in humanitarian settings. The combination of high mortality and a lack of microbiology testing means that severe illness is often treated with diagnostic uncertainty, leading to an overuse of antibiotics. The challenge of access to microbiology was discussed, including the important role that understanding of local antimicrobial resistance patterns plays in stewardship practices. While extensive data on antimicrobial resistance exist in some settings, there is a complete lack of data in many parts of the world. But even without access to microbiology, there is capacity to improve antibiotic stewardship and IPC, which are essential and feasible in all settings.17 The importance of an interdisciplinary approach was discussed, ensuring involvement of all members of the team, including doctors, nurses, pharmacists and cleaners. Practical tools to support field teams to assess and monitor medical activities from an antimicrobial resistance lens are available within and outside MSF, such as point prevalence surveys on antibiotic use, antibiotic consumption analysis and the stepwise IPC approach. Key messages for this session can be found in table 5.

Table 5.

Antimicrobial resistance and antimicrobial stewardship in neonatal and paediatric care

| Key messages | Why is it important? | Current challenges | Recommendations |

| Patients, and especially newborns and children, are harmed by and even die because of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in MSF projects. The problem is escalating in front of us like an invisible tsunami, with limited visibility on its burden and consequences. It is critical for MSF to systematically implement the available tools to reduce AMR, especially where microbiology is not available: infection prevention and control (IPC) and antibiotic stewardship |

AMR is a reality in humanitarian settings and newborn and children are particularly exposed. Multidrug-resistant bacterial sepsis particularly affects the most fragile patients, as shown by the increase in the reports of outbreaks in neonatal units in low-resource settings. IPC and antibiotic stewardship are crucial and effective strategies against AMR, particularly in contexts where microbiology is unavailable. |

|

Field

Operations

Research/Headquarters

|

AMR, Antimirobial resistance; IPC, Infection prevention and control; MSF, Médecins Sans Frontières.

Collateral damage of COVID-19 on child health

The last session of the event was dedicated to the ‘Collateral damage of COVID-19 on child health’. Children have been disproportionally affected by the pandemic, with low mortality due to COVID-19 itself, but high morbidity and mortality due to the multiple collateral effects of the health crisis. The pandemic has impacted child health through increases in poverty, loss of education, food insecurity and violence, as well as greater strains on health systems and a reduction in access to health services. Preventive services like vaccination and nutrition programmes have been mostly suspended or delayed.18 The indirect effects of the pandemic have been most severe in resource-limited settings where increased child mortality is a major concern, widening the gap of inequity for children. There were field testimonies from frontline health workers outlining the struggle they faced during this unprecedented time. Supporting health systems to maintain preventive and curative services is crucial to attenuate the ongoing impact. Flexibility to adjust health activities is key to face the challenges brought by the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Boosting community healthcare activities within MSF strategies, as an essential part of the continuum of care, is an efficient way of assuring healthcare access. Find in table 6 the key messages of this session.

Table 6.

Collateral damage of COVID-19 on child health

| Key messages | Why is it important? | Current challenges | Recommendations |

| Children have disproportionally been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, with low direct mortality, but high morbidity and mortality due to the multiple collateral effects of the health crisis. This unprecedented crisis offers an opportunity to change our ways of thinking, deploy and maintain our activities, rethink support models and define future preparedness and responses. |

The pandemic has impacted child health through increases in poverty, loss of education, food insecurity, violence as well as increased strain on health systems and reduction in access to health services. These collateral effects of the pandemic have been most striking in resource-limited settings where increase in child mortality is a major concern. Preventive services like vaccination and nutrition programmes have been affected most by suspension or delay. The tremendous detrimental effects of the pandemic on child health are still unfolding and our concern as MSF should be high. |

|

Field

Operations

Headquarters

|

MSF, Médecins Sans Frontières.

Despite the collateral damage already caused, this past year can also be an opportunity to change our ways of thinking, activities, support models and future preparedness and responses. More than ever, now is a crucial time to invest in humanitarian paediatrics, to support children and uphold their rights in the most fragile contexts.

Conclusions

As the world continues to battle the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, focus and funding for child health in humanitarian settings suffer while children’s needs escalate. The future for children in humanitarian settings hangs in the balance, and platforms that raise the profile of humanitarian paediatrics are vital to ensure that these children are not overlooked and remain a priority among funders, decision-makers and stakeholders. The MSF Paediatric Days serves as a unique forum to advance knowledge on humanitarian paediatrics, and to create opportunities for individual and collective learning on this topic. We look forward to the next edition and welcome all suggestions for the next topics of the MSF Paediatric Days.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to our frontline field staff for providing essential and life-saving services to vulnerable populations, despite the enormous challenges posed by the contexts in which they work. We would like to acknowledge their commitment to their patients and the increadible work that they carry out on a daily basis to decrease the inequalities in child health globally.

Footnotes

Contributors: SJ: substantial contributions to the conception, drafting of manuscript, revision, final approval and submission. NR, NM, DM, MT, NL, OO, ED, RP: substantial contributions to the conception, revision and final approval. HR, IC, AG: substantial contributions to the conception and final approval.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data sharing not applicable as no data sets generated and/or analysed for this study.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1.United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs . Global humanitarian overview 2019 [online], 2019. Available: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/GHO2019.pdf

- 2.UNICEF . Levels and trends in child mortality report 2018, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.A.Spencer BW-K& . Reducing the humanitarian financing gap: review of progress since the report of the high-level panel on humanitarian financing, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roberton T, Carter ED, Chou VB, et al. Early estimates of the indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and child mortality in low-income and middle-income countries: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health 2020;8:e901–8. 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30229-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wagner Z, Heft-Neal S, Bhutta ZA, et al. Armed conflict and child mortality in Africa: a geospatial analysis. Lancet 2018;392:857–65. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31437-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shenoda S, Kadir A, Pitterman S, et al. The effects of armed conflict on children. Pediatrics 2018;142:e20182585. 10.1542/peds.2018-2585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pfefferbaum B, Jacobs AK, Van Horn RL, et al. Effects of displacement in children exposed to disasters. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2016;18:1–5. 10.1007/s11920-016-0714-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MSF Paediatric Working Group . Paediatric activities medecins SANS Frontieres, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 9.UNICEF . Save the children WHO. roadmap to accelerate progress for every newborn in humanitarian settings 2020–2025, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jakobsen M, Sodemann M, Nylén G, et al. Breastfeeding status as a predictor of mortality among refugee children in an emergency situation in Guinea-Bissau. Trop Med Int Heal 2003;8:992–6. 10.1046/j.1360-2276.2003.01122.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hipgrave DB, Assefa F, Winoto A, et al. Donated breast milk substitutes and incidence of diarrhoea among infants and young children after the may 2006 earthquake in Yogyakarta and central Java. Public Health Nutr 2012;15:307–15. 10.1017/S1368980010003423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaker-Berbari L, Ghattas H, Symon AG, et al. Infant and young child feeding in emergencies: organisational policies and activities during the refugee crisis in Lebanon. Matern Child Nutr 2018;14:e12576. 10.1111/mcn.12576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanapathipillai R, Malou N, Hopman J, et al. Antibiotic resistance in conflict settings: lessons learned in the Middle East. JAC Antimicrob Resist 2019;1:2–4. 10.1093/jacamr/dlz002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langendorf C, Le Hello S, Moumouni A, et al. Enteric bacterial pathogens in children with diarrhea in niger: diversity and antimicrobial resistance. PLoS One 2015;10:e0120275. 10.1371/journal.pone.0120275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okomo U, Senghore M, Darboe S, et al. Investigation of sequential outbreaks of Burkholderia cepacia and multidrug-resistant extended spectrum β-lactamase producing Klebsiella species in a West African tertiary hospital neonatal unit: a retrospective genomic analysis. The Lancet Microbe 2020;1:e119–29. 10.1016/S2666-5247(20)30061-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lenglet A, Faniyan O, Hopman J. A nosocomial outbreak of clinical sepsis in a neonatal care unit (NCU) in Port-au-Prince Haiti, July 2014 – September 2015. PLoS Curr 2018. 10.1371/currents.outbreaks.58723332ec0de952adefd9a9b6905932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson J, Akinboyo IC, Curless MS, et al. Saving neonatal lives by improving infection prevention in low-resource units: tools are needed. J Glob Health 2019;9:9–11. 10.7189/jogh.09.010319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sidhu S. WHO and UNICEF warn of a decline in vaccinations during COVID-19. World Health Organization, 2020. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable as no data sets generated and/or analysed for this study.