Abstract

Background

The global burden of poor maternal, neonatal, and child health (MNCH) accounts for more than a quarter of healthy years of life lost worldwide. Targeted client communication (TCC) via mobile devices (MD) (TCCMD) may be a useful strategy to improve MNCH.

Objectives

To assess the effects of TCC via MD on health behaviour, service use, health, and well‐being for MNCH.

Search methods

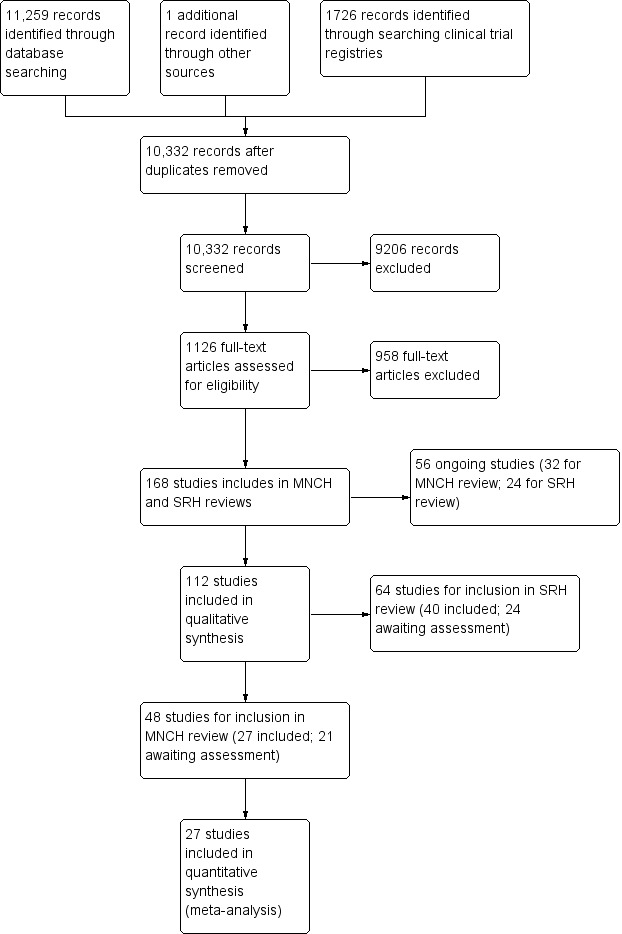

In July/August 2017, we searched five databases including The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, MEDLINE and Embase. We also searched two trial registries. A search update was carried out in July 2019 and potentially relevant studies are awaiting classification.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials that assessed TCC via MD to improve MNCH behaviour, service use, health, and well‐being. Eligible comparators were usual care/no intervention, non‐digital TCC, and digital non‐targeted client communication.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures recommended by Cochrane, although data extraction and risk of bias assessments were carried out by one person only and cross‐checked by a second.

Main results

We included 27 trials (17,463 participants). Trial populations were: pregnant and postpartum women (11 trials conducted in low‐, middle‐ or high‐income countries (LMHIC); pregnant and postpartum women living with HIV (three trials carried out in one lower middle‐income country); and parents of children under the age of five years (13 trials conducted in LMHIC). Most interventions (18) were delivered via text messages alone, one was delivered through voice calls only, and the rest were delivered through combinations of different communication channels, such as multimedia messages and voice calls.

Pregnant and postpartum women

TCCMD versus standard care

For behaviours, TCCMD may increase exclusive breastfeeding in settings where rates of exclusive breastfeeding are less common (risk ratio (RR) 1.30, 95% confidence intervals (CI) 1.06 to 1.59; low‐certainty evidence), but have little or no effect in settings where almost all women breastfeed (low‐certainty evidence). For use of health services, TCCMD may increase antenatal appointment attendance (odds ratio (OR) 1.54, 95% CI 0.80 to 2.96; low‐certainty evidence); however, the CI encompasses both benefit and harm. The intervention may increase skilled attendants at birth in settings where a lack of skilled attendants at birth is common (though this differed by urban/rural residence), but may make no difference in settings where almost all women already have a skilled attendant at birth (OR 1.00, 95% CI 0.34 to 2.94; low‐certainty evidence). There were uncertain effects on maternal and neonatal mortality and morbidity because the certainty of the evidence was assessed as very low.

TCCMD versus non‐digital TCC (e.g. pamphlets)

TCCMD may have little or no effect on exclusive breastfeeding (RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.07; low‐certainty evidence). TCCMD may reduce 'any maternal health problem' (RR 0.19, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.79) and 'any newborn health problem' (RR 0.52, 95% CI 0.25 to 1.06) reported up to 10 days postpartum (low‐certainty evidence), though the CI for the latter includes benefit and harm. The effect on health service use is unknown due to a lack of studies.

TCCMD versus digital non‐targeted communication

No studies reported behavioural, health, or well‐being outcomes for this comparison. For use of health services, there are uncertain effects for the presence of a skilled attendant at birth due to very low‐certainty evidence, and the intervention may make little or no difference to attendance for antenatal influenza vaccination (RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.71 to 1.58), though the CI encompasses both benefit and harm (low‐certainty evidence).

Pregnant and postpartum women living with HIV

TCCMD versus standard care

For behaviours, TCCMD may make little or no difference to maternal and infant adherence to antiretroviral (ARV) therapy (low‐certainty evidence). For health service use, TCC mobile telephone reminders may increase use of antenatal care slightly (mean difference (MD) 1.5, 95% CI –0.36 to 3.36; low‐certainty evidence). The effect on the proportion of births occurring in a health facility is uncertain due to very low‐certainty evidence. For health and well‐being outcomes, there was an uncertain intervention effect on neonatal death or stillbirth, and infant HIV due to very low‐certainty evidence. No studies reported on maternal mortality or morbidity.

TCCMD versus non‐digital TCC

The effect is unknown due to lack of studies reporting this comparison.

TCCMD versus digital non‐targeted communication

TCCMD may increase infant ARV/prevention of mother‐to‐child transmission treatment adherence (RR 1.26, 95% CI 1.07 to 1.48; low‐certainty evidence). The effect on other outcomes is unknown due to lack of studies.

Parents of children aged less than five years

No studies reported on correct treatment, nutritional, or health outcomes.

TCCMD versus standard care

Based on 10 trials, TCCMD may modestly increase health service use (vaccinations and HIV care) (RR 1.21, 95% CI 1.08 to 1.34; low‐certainty evidence); however, the effect estimates varied widely between studies.

TCCMD versus non‐digital TCC

TCCMD may increase attendance for vaccinations (RR 1.13, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.28; low‐certainty evidence), and may make little or no difference to oral hygiene practices (low‐certainty evidence).

TCCMD versus digital non‐targeted communication

TCCMD may reduce attendance for vaccinations, but the CI encompasses both benefit and harm (RR 0.63, 95% CI 0.33 to 1.20; low‐certainty evidence).

No trials in any population reported data on unintended consequences.

Authors' conclusions

The effect of TCCMD for most outcomes is uncertain. There may be improvements for some outcomes using targeted communication but these findings were of low certainty. High‐quality, adequately powered trials and cost‐effectiveness analyses are required to reliably ascertain the effects and relative benefits of TCCMD. Future studies should measure potential unintended consequences, such as partner violence or breaches of confidentiality.

Keywords: Child, Preschool; Female; Humans; Infant; Infant, Newborn; Pregnancy; Breast Feeding; Breast Feeding/statistics & numerical data; Cell Phone; Child Health; Child Health/standards; Child Health/statistics & numerical data; Communication; Delivery, Obstetric; Delivery, Obstetric/standards; Health Behavior; Health Services Needs and Demand; Health Status; HIV Infections; HIV Infections/drug therapy; Infant Health; Infant Health/standards; Infant Health/statistics & numerical data; Maternal Health; Maternal Health/standards; Maternal Health/statistics & numerical data; Medication Adherence; Medication Adherence/statistics & numerical data; Postpartum Period; Prenatal Care; Prenatal Care/statistics & numerical data; Quality Improvement; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Text Messaging

Plain language summary

Communicating to pregnant woman and parents through their mobile devices to improve maternal, neonatal, and child health

Aim of this review

We assessed the effect of sending targeted messages by mobile devices to pregnant women and parents of young children about health and healthcare services.

Key messages

There are gaps in the evidence regarding the effects of targeted messages by mobile devices to pregnant women and parents of young children about health and healthcare services. Some of these messages may improve some people's health and their use of health services, but others may make little or no difference. The existing evidence is mostly of low or very low certainty.

What was studied in the review?

Targeted client communication (TCC) is an intervention in which the health system sends information to particular people, based on their health status or other factors specific to that population group. Common types of TCC are text messages reminding people to attend appointments or that offer healthcare information and support. Our review assessed whether TCC can change pregnant women's and parents' behaviour, health service use, health, and well‐being.

What happens when pregnant women receive targeted messages by mobile device?

Compared to women who get no messages

Women may breastfeed more in settings where exclusive breastfeeding is not common. They may also go to more antenatal care appointments. They may use skilled birth attendants more where this is less common. We do not know if the messages affect women's or babies' health because the certainty of the evidence is very low.

Compared to women who get messages sent in other ways

Women and newborns may have fewer health problems during the first 10 days after birth. The messages may make little or no difference to the number of women who breastfeed. We do not know if they make women use more health services.

Compared to women who get untargeted messages

The messages may make little or no difference to whether women get influenza vaccines during pregnancy. We do not know if the messages affect women's or babies' health or lead women to use skilled birth attendants more because the evidence is lacking or of very low certainty.

What happens when pregnant women living with HIV receive targeted messages by mobile device?

Compared to women who get no messages

Women may go to slightly more antenatal care appointments. We do not know whether the messages lead more women to give birth in a health facility or improve babies' health because the evidence is of very low certainty. The messages may make little or no difference to whether pregnant women and babies follow antiretroviral (ARV) treatment (used to treat HIV) according to plan. We do not know if the messages affect women's health because the evidence is missing.

Compared to women who get messages sent in other ways

We do not know what the effect of these messages is because we lack evidence.

Compared to women who get untargeted messages

More parents may follow their babies' ARV treatment according to plan. We do not know if the messages improve women's or babies' health or their use of services because the evidence is missing.

What happens when parents of young children receive targeted messages by mobile device?

Compared to parents who get no messages

More parents may take their children to healthcare services such as vaccination appointments. But we do not know if the messages improve children's health or their health behaviour because the evidence is missing.

Compared to parents who get messages sent in other ways

Slightly more parents may take their children to vaccination appointments. The messages may make little or no difference to children's toothbrushing habits. We do not know if the messages affect children's health because the evidence is missing.

Compared to parents who get untargeted messages

Fewer parents may take their children to vaccination appointments, but this evidence is mixed. We do not know if the messages affect children's health due to lack of evidence.

How up‐to‐date is this review?

We searched for studies published up to August 2017. We carried out a search update in July 2019 and relevant studies are reported in the 'Characteristics of studies awaiting classification' section.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Digital targeted client communication via mobile devices compared to standard care or no intervention (pregnant and postpartum women) for improving maternal, neonatal, and child health.

| Digital targeted client communication via mobile devices compared to standard care or no intervention (pregnant and postpartum women) for improving maternal, neonatal, and child health | ||||||

| Patient or population: pregnant and postpartum women Setting: community and healthcare settings Intervention: digital targeted client communication via mobile devices Comparison: standard care or no intervention | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with standard care | Risk with digital targeted client communication | |||||

|

Health status and well‐being – maternal mortality and morbidity Follow‐up: up to 3 months |

4 RCTs reported on 5 morbidity outcomes and the CIs for most outcomes encompassed both benefit and harm: severe obstetric complications up to 6 weeks postpartum (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.07); 'any maternal health problem' up to 10 days postpartum (RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.90 to 2.76); breast pain up to 3 months postpartum (RR 0.28, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.80); breast engorgement up to 3 months postpartum (RR 0.58, 95% CI 0.31 to 1.10); number of acute maternal episodes requiring a clinic visit up to 3 months postpartum (MD 0.06, 95% CI –0.19 to 0.31). 1 study also reported on maternal mortality (RR 2.86, 95% CI 0.30 to 27.40), but this study only recorded 5 events. | 3073 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c | We are uncertain of the effect of the intervention on maternal mortality and morbidity because the certainty of the evidence was very low. | ||

|

Health status and well‐being – neonatal mortality and morbidity Follow‐up: up to 3 months |

The results of pooled analysis of 3 RCTs for neonatal morbidity and mortality combined was consistent with no effect but CIs encompassed benefit and harm (OR 1.00, 95% CI 0.61 to 1.64). 1 RCT reported that the intervention reduced number of acute neonatal episodes requiring a clinic visit up to 3 months postpartum (MD –0.53, 95% CI –0.92 to –0.14). | 3005 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c | We are uncertain of the effect of the intervention on neonatal mortality and morbidity because the certainty of the evidence was very low. | ||

|

Health behaviour change: breastfeeding – exclusive breastfeeding Follow‐up: up to 3 months |

Low‐risk setting | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,d | In settings where 100% of women report exclusive breasting, the intervention may make little or no difference to exclusive breastfeeding (though an increase would not be possible). The CI encompasses no effect and harm. The intervention may increase short‐term exclusive breastfeeding in settings where rates of exclusive breastfeeding are lower. |

|||

| 1000 per 1000 | 920 per 1000 (790 to 1000) | RR 0.92 (0.79 to 1.08) | 40 (1 RCT) |

|||

| Moderate‐risk setting | ||||||

| 667 per 1000 | 867 per 1000 (707 to 1000) | RR 1.30 (1.06 to 1.59) | 135 (1 RCT) | |||

|

Service utilisation – attendance at ≥ 4 antenatal care appointments Follow‐up: during antenatal period |

311 per 1000 | 410 per 1000 (265 to 572) | OR 1.54 (0.80 to 2.96) | 2550 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | The intervention may increase attendance for antenatal care appointments, but the CI includes both an increase and a decrease. |

|

Service utilisation: intrapartum care – skilled attendant at birth Follow‐up: at delivery |

Low‐risk setting | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | The intervention may make little or no difference to the proportion of births occurring with skilled attendance in settings where skilled attendance at is common. In settings where skilled attendance at birth is less common, the intervention may increase the proportion of births occurring with skilled attendance in urban areas. The intervention may slightly reduce skilled attendance in rural settings, but the CI encompasses both benefit and harm. |

|||

| 988 per 1000 | 988 per 1000 (978 to 998) | OR 1.00 (0.34 to 2.94) | 1743 (1 RCT) | |||

| High‐risk setting | ||||||

| Results were presented separately for urban and rural populations. The study reported intervention benefit in urban populations (cluster‐adjusted OR 4.45, 95% CI 1.36 to 14.51), but not in rural populations (cluster adjusted OR 0.83, 95% CI 0.36 to 1.92) | 2550 (1 RCT) | |||||

| Unintended consequences | No studies reported this outcome. | — | (0 studies) | — | The effect of the intervention on unintended consequences is unknown as there was no direct evidence identified. | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; OR: odds ratio; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level for risk of bias: all studies had unclear sequence generation or allocation concealment, or both. bDowngraded one level for imprecision: 95% confidence intervals that encompass both harmful and beneficial effects of the intervention. cDowngraded one level due to inconsistency: effect estimates vary in terms of direction and magnitude of effect. dDowngraded one level for imprecision: few events.

Summary of findings 2. Digital targeted client communication via mobile devices compared to non‐digital targeted client communication (pregnant and postpartum women) for improving maternal, neonatal, and child health.

| Digital targeted client communication via mobile devices compared to non‐digital targeted client communication (pregnant and postpartum women) for improving maternal, neonatal, and child health | ||||||

| Patient or population: pregnant and postpartum women Setting: community and healthcare settings Intervention: digital targeted client communication via mobile devices Comparison: non‐digital targeted client communication | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with non‐digital targeted client communication | Risk with digital targeted client communication | |||||

| Health status and well‐being – maternal mortality and morbidity ('any maternal health problem' up to 10 days postpartum) | 333 per 1000 | 63 per 1000 (13 to 263) | RR 0.19 (0.04 to 0.79) | 59 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | The intervention may reduce the proportion of women reporting a maternal health problem up to 10 days after birth. |

| Health status and well‐being – neonatal mortality and morbidity ('any newborn health problem' up to 10 days postpartum) | 481 per 1000 | 250 per 1000 (120 to 510) | RR 0.52 (0.25 to 1.06) | 59 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | The intervention may reduce the proportion of women reporting a newborn health problem up to 10 days after birth. But the CI includes both an increase and a decrease in reporting. |

| Health behaviour change: breastfeeding (exclusive breastfeeding at 9 weeks) | 1000 per 1000 | 920 per 1000 (790 to 1000) | RR 0.92 (0.79 to 1.07) | 42 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | The intervention may make little or no difference to the proportion who breastfeed exclusively (though an increase would not be possible due to 100% breastfeeding in the control arm). The CI encompasses no beneficial effect and harm. It is possible the effect of the intervention may be different in populations with different levels of baseline risk. |

| Service utilisation – attendance antenatal care appointments | No studies reported this outcome. | — | (0 studies) | — | The effect of the intervention on attendance for antenatal care is unknown as there was no direct evidence identified. | |

| Service utilisation: intrapartum care – skilled attendant at birth | No studies reported this outcome. | — | (0 studies) | — | The effect of the intervention on intrapartum care is unknown as there was no direct evidence identified. | |

| Unintended consequences | No studies reported this outcome. | — | (0 studies) | — | The effect of the intervention on unintended consequences is unknown as there was no direct evidence identified. | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level for risk of bias: unclear risk of bias for allocation concealment and incomplete outcome data. bDowngraded one level for imprecision: few events.

Summary of findings 3. Digital targeted client communication via mobile devices compared to digital non‐targeted client communication (pregnant and postpartum women) for improving maternal, neonatal, and child health.

| Digital targeted client communication via mobile devices compared to digital non‐targeted client communication (pregnant and postpartum women) for improving maternal, neonatal, and child health | ||||||

| Patient or population: pregnant and postpartum women Setting: community and healthcare settings Intervention: digital targeted client communication via mobile devices Comparison: digital non‐targeted client communication | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with digital non‐targeted communication | Risk with digital targeted client communication | |||||

| Health status and well‐being – maternal mortality and morbidity | No studies reported this outcome. | — | (0 studies) | — | The effect of the intervention on maternal morbidity and mortality is unknown as there was no direct evidence. | |

| Health status and well‐being – neonatal mortality and morbidity | No studies reported this outcome. | — | (0 studies) | — | The effect of the intervention on neonatal morbidity and mortality is unknown as there was no direct evidence. | |

| Health behaviour change: breastfeeding | No studies reported this outcome. | — | (0 studies) | — | The effect of the intervention on breastfeeding is unknown as there was no direct evidence. | |

| Service utilisation – attendance antenatal care appointments (attendance for antenatal influenza vaccination) | 310 per 1000 | 326 per 100 (220 to 490) | RR 1.05 (0.71 to 1.58) | 204 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | The intervention may make little or no difference to attendance for antenatal influenza vaccination, but the CI includes both an increase and a decrease in attendance. |

|

Service utilisation: intrapartum care – skilled attendant at birth Follow‐up: at delivery |

875 per 1000 | 875 per 1000 (604 to 1000) | RR 1.00 (0.69 to 1.45) | 16 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb,c | We are uncertain of the effect of the intervention on the proportion of women having a skilled attendant at birth because the certainty of the evidence was very low. |

| Unintended consequences | No studies reported this outcome. | — | (0 studies) | — | The effect of the intervention on unintended consequences is unknown as there was no direct evidence. | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level for imprecision: 95% confidence intervals that encompass a potential harmful effect and a potential beneficial effect of the intervention. bDowngraded one level for risk of bias: trial at unclear risk of bias for several domains. cDowngraded two levels for risk of bias: trial at unclear or high risk of bias across all domains.

Summary of findings 4. Digital targeted client communication via mobile devices compared to standard care or no intervention (pregnant and postpartum women with HIV) for improving maternal, neonatal, and child health.

| Digital targeted client communication via mobile devices compared to standard care or no intervention (pregnant and postpartum women with HIV) for improving maternal, neonatal, and child health | ||||||

| Patient or population: pregnant and postpartum women with HIV Setting: community and healthcare settings Intervention: digital targeted client communication via mobile devices Comparison: standard care or no intervention | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with standard care | Risk with digital targeted client communication | |||||

| Health status and well‐being: maternal morbidity and mortality combined | No studies reported this outcome. | — | (0 studies) | — | The effect of the intervention on maternal morbidity and mortality is unknown as there was no direct evidence. | |

|

Health status and well‐being – neonatal morbidity and mortality combined Follow‐up: up to 4 weeks |

32 per 1000 | 36 per 1000 (12 to 105) | RR 1.12 (0.39 to 3.28) | 381 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa |

The intervention may make little or no difference to neonatal mortality and morbidity. However, the CI includes both an increase and a decrease in neonatal mortality and morbidity. |

|

Service utilisation – antenatal care: communications with HCWs Follow‐up: during antenatal period |

Mean number of face‐to‐face or mobile communications with HCW for antenatal care was 6 | Mean number of face‐to‐face or mobile communications with HCW for antenatal care was 7.5 (5.64 to 9.36) | MD 1.50 (–0.36 to 3.36) | 297 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb | The intervention may slightly increase attendance for antenatal care appointments. |

|

Service utilisation – intrapartum care: birth in health facility Follow‐up: at delivery |

600 per 1000 | 510 per 1000 (372to 690) | RR 0.85 (0.62 to 1.15) | 134 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb,c | We are uncertain of the effect of the intervention on the proportion of women giving birth in a health facility because certainty of the evidence was very low. |

|

Health status and well‐being – neonatal health: infant HIV test positive Follow‐up: 8 weeks postpartum |

13 per 1000 | 7 per 1000 (1 to 33) | RR 0.54 (0.11 to 2.56) | 852 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowd,e | We are uncertain of the effect of the intervention on the proportion of infants testing positive for HIV because the certainty of the evidence was very low. |

|

Health behaviour change: adherence to ARV therapy Follow‐up: up to 6–8 weeks postpartum |

1 study reported maternal antenatal ARV usage (RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.19), maternal postnatal ARV usage (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.61 to 1.24), and infant ARV/PMTCT treatment adherence at 6–8 weeks postpartum (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.04). | 503 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb | The intervention may make little or no difference to maternal and infant ARV treatment adherence. However, the CI includes benefit and harm. | ||

| Unintended consequences | No studies reported this outcome. | — | (0 studies) | — | The effect of the intervention on unintended consequences is unknown as there was no direct evidence. | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ARV: antiretroviral; CI: confidence interval; HCW: healthcare worker; MD: mean difference; PMTCT: prevention of mother‐to‐child transmission; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded two levels for imprecision: few events and a 95% confidence intervals that encompass a potential large harmful effect and a potential large beneficial effect of the intervention. bDowngraded two levels for risk of bias: more women were newly diagnosed with HIV in the control arm (55% with intervention versus 66% with control; P = 0.015), randomisation procedures and allocation concealment were not described, lack of blinding of participants, and only per‐protocol analysis reported with unexplained dropouts (Kassaye 2016). cDowngraded one level for imprecision: 95% confidence intervals that encompass a harmful effect and a potential beneficial effect of the intervention. dDowngraded one level for risk of bias: for one trial randomisation procedures and allocation concealment were not described, lack of blinding of participants, and only per‐protocol analysis reported with unexplained dropouts. eDowngraded two levels for imprecision: few events and a 95% confidence intervals that encompass a potential large harmful effects and a potential large beneficial effect of the intervention.

Summary of findings 5. Digital targeted client communication via mobile devices compared to non‐digital targeted client communication (pregnant and postpartum women with HIV) for improving maternal, neonatal, and child health.

| Digital targeted client communication via mobile devices compared to non‐digital targeted client communication (pregnant and postpartum women with HIV) for improving maternal, neonatal, and child health | ||||||

| Patient or population: pregnant and postpartum women with HIV Setting: community and healthcare settings Intervention: digital targeted client communication via mobile devices Comparison: non‐digital targeted client communication | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with non‐digital targeted client communication | Risk with digital targeted client communication | |||||

| Health status and well‐being: maternal morbidity and mortality combined | No studies reported this outcome. | — | (0 studies) | — | The effect of the intervention on maternal morbidity and mortality is unknown as there was no direct evidence. | |

| Health status and well‐being – neonatal morbidity and mortality combined | No studies reported this outcome. | — | (0 studies) | — | The effect of the intervention on neonatal morbidity mortality is unknown as there was no direct evidence. | |

| Service utilisation – antenatal care | No studies reported this outcome. | — | (0 studies) | — | The effect of the intervention on attendance for antenatal care is unknown as there was no direct evidence. | |

| Service utilisation – intrapartum care | No studies reported this outcome. | — | (0 studies) | — | The effect of the intervention on intrapartum care is unknown as there was no direct evidence. | |

| Health status and well‐being – neonatal health: infant HIV status | No studies reported this outcome. | — | (0 studies) | — | The effect of the intervention on the proportion of infants testing positive for HIV is unknown as there was no direct evidence. | |

| Health behaviour change: adherence to ARV therapy | No studies reported this outcome. | — | (0 studies) | — | The effect of the intervention on adherence to ARV therapy is unknown as there was no direct evidence. | |

| Unintended consequences | No studies reported this outcome. | — | (0 studies) | — | The effect of the intervention on unintended consequences is unknown as there was no direct evidence. | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ARV: antiretroviral; CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

Summary of findings 6. Digital targeted client communication via mobile devices compared to digital non‐targeted client communication (pregnant and postpartum women with HIV) for improving maternal, neonatal, and child health.

| Digital targeted client communication via mobile devices compared to digital non‐targeted client communication (pregnant women and postpartum with HIV) for improving maternal, neonatal, and child health | ||||||

| Patient or population: pregnant and postpartum women with HIV Setting: community and healthcare settings Intervention: digital targeted client communication via mobile devices Comparison: digital non‐targeted client communication | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with digital non‐targeted client communication | Risk with digital targeted client communication | |||||

| Health status and well‐being – maternal morbidity and mortality combined | No studies reported this outcome. | — | (0 studies) | — | The effect of the intervention on maternal morbidity and mortality is unknown as there was no direct evidence. | |

| Health status and well‐being – neonatal morbidity and mortality combined | No studies reported this outcome. | — | (0 studies) | — | The effect of the intervention on neonatal morbidity mortality is unknown as there was no direct evidence. | |

| Service utilisation – antenatal care | No studies reported this outcome. | — | (0 studies) | — | The effect of the intervention on attendance for antenatal care is unknown as there was no direct evidence. | |

| Service utilisation – intrapartum care | No studies reported this outcome. | — | (0 studies) | — | The effect of the intervention on intrapartum care is unknown as there was no direct evidence. | |

| Health status and well‐being – neonatal health: infant HIV status | No studies reported this outcome. | — | (0 studies) | — | The effect of the intervention on the proportion of infants testing positive for HIV is unknown as there was no direct evidence. | |

|

Health behaviour change: adherence to ARV therapy Follow‐up: 6 weeks postpartum |

720 per 1000 | 907 per 1000 (770 to 1000) | RR 1.26 (1.07 to 1.48) | 150 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa | The intervention may increase infant ARV adherence. |

| Unintended consequences | No studies reported this outcome. | — | (0 studies) | — | The effect of the intervention on unintended consequences is unknown as there was no direct evidence. | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ARV: antiretroviral; CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded twice for risk of bias: trial at high or unclear risk of bias across all applicable domains.

Summary of findings 7. Digital targeted client communication via mobile devices compared to standard care or no intervention (parents of children aged under five years) for improving maternal, neonatal, and child health.

| Digital targeted client communication via mobile devices compared to standard care or no intervention (parents of children aged < 5 years) for improving maternal, neonatal, and child health | ||||||

| Patient or population: parents of children aged < 5 years Setting: community and healthcare settings Intervention: digital targeted client communication via mobile devices Comparison: standard care or no intervention | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with standard care | Risk with digital targeted client communication | |||||

| Health status and well‐being – child morbidity and mortality combined | No studies reported this outcome. | — | (0 studies) | — | The effect of the intervention on child morbidity and mortality is unknown as there was no direct evidence. | |

| Health status and well‐being – child nutritional status | No studies reported this outcome. | — | (0 studies) | — | The effect of the intervention on child nutritional status is unknown as there was no direct evidence. | |

| Health behaviour change – breastfeeding | No studies reported this outcome. | — | (0 studies) | — | The effect of the intervention on breastfeeding is unknown as there was no direct evidence. | |

|

Service utilisation – attendance for necessary healthcare (attendance for vaccinations at 6–12 months, attendance at HIV medical appointments) Follow‐up: up to 12 months |

642 per 1000 | 777 per 1000 (693 to 860) | RR 1.21 (1.08 to 1.34) | 5660 (10 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | The intervention may increase attendance for necessary healthcare. However, the result varied considerably according to whether the healthcare attendance was for vaccinations at 6 months, vaccinations at 12 months, or an HIV medical appointment, and between studies within each of these outcome categories. |

| Health behaviour change – hygiene practices | No studies reported this outcome. | — | (0 studies) | — | The effect of the intervention on hygiene practices is unknown as there was no direct evidence. | |

| Health behaviour change – correct treatment taken | No studies reported this outcome. | — | (0 studies) | — | The effect of the intervention on taking correct treatment is unknown as there was no direct evidence. | |

| Unintended consequences | No studies reported this outcome. | — | (0 studies) | — | The effect of the intervention on unintended consequences is unknown as there was no direct evidence. | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level for risk of bias: most studies at unclear risk of bias for allocation concealment. bDowngraded one level for inconsistency: high statistical heterogeneity (I2 > 90%).

Summary of findings 8. Digital targeted client communication via mobile devices compared to non‐digital targeted client communication (parents of children aged under five years) for improving maternal, neonatal, and child health.

| Digital targeted client communication via mobile devices compared to non‐digital targeted client communication (parents of children aged < 5 years) for improving maternal, neonatal, and child health | ||||||

| Patient or population: parents of children aged < 5 years Setting: community and healthcare settings Intervention: digital targeted client communication via mobile devices Comparison: non‐digital targeted client communication | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with non‐digital targeted client communication | Risk with digital targeted client communication | |||||

| Health status and well‐being – child morbidity and mortality combined | No studies reported this outcome. | — | (0 studies) | — | The effect of the intervention on child morbidity and mortality is unknown as there was no direct evidence. | |

| Health status and well‐being – child nutritional status | No studies reported this outcome. | — | (0 studies) | — | The effect of the intervention on child nutritional status is unknown as there was no direct evidence. | |

| Health behaviour change – breastfeeding | No studies reported this outcome. | — | (0 studies) | — | The effect of the intervention on breastfeeding is unknown as there was no direct evidence. | |

| Service utilisation – attendance for necessary healthcare (attendance for vaccinations at 14 weeks) | 839 per 1000 | 948 per 1000 (839 to 1000) | RR 1.13 (1.00 to 1.28) | 744 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa | The intervention may slightly increase attendance for vaccinations. However, the CI includes both no increase and a large increase in attendance. |

| Health behaviour change – hygiene practices (oral health in children at 4 weeks, Visible Plaque Index, 0–100%, lower score is better) | Mean score: 35.6 | Mean score: 33.5 (28.06 to 38.94) | MD –2.10 (–7.54 to 3.34) | 143 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb,c | The intervention may make little or no difference to oral hygiene practices. However, the CI includes both benefit and harm. |

| Health behaviour change – correct treatment taken | No studies reported this outcome. | — | (0 studies) | — | The effect of the intervention on taking correct treatment is unknown as there was no direct evidence. | |

| Unintended consequences | No studies reported this outcome. | — | (0 studies) | — | The effect of the intervention on unintended consequences is unknown as there was no direct evidence. | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded two levels for risk of bias: study at unclear or high risk of bias across all but one domain. bDowngraded one level for imprecision: confidence interval encompasses both benefit and harm. cDowngraded one level for risk of bias: study at unclear risk of bias for sequence generation and allocation concealment.

Summary of findings 9. Digital targeted client communication via mobile devices compared to digital non‐targeted client communication (parents of children aged under five years) for improving maternal, neonatal, and child health.

| Digital targeted client communication via mobile devices compared to digital non‐targeted client communication (parents of children aged < 5 years) for improving maternal, neonatal, and child health | ||||||

| Patient or population: parents of children aged < 5 years Setting: community and healthcare settings Intervention: digital targeted client communication via mobile devices Comparison: digital non‐targeted client communication | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with digital non‐targeted client communication | Risk with digital targeted client communication | |||||

| Health status and well‐being – child morbidity and mortality combined | No studies reported this outcome. | — | (0 studies) | — | The effect of the intervention on child morbidity and mortality is unknown as there was no direct evidence. | |

| Health status and well‐being – child nutritional status | No studies reported this outcome. | — | (0 studies) | — | The effect of the intervention on child nutritional status is unknown as there was no direct evidence. | |

| Health behaviour – breastfeeding | No studies reported this outcome. | — | (0 studies) | — | The effect of the intervention on breastfeeding is unknown as there was no direct evidence. | |

|

Service utilisation – attendance for necessary healthcare – attendance for vaccinations at 6 months Follow‐up: 6 months |

652 per 1000 | 411 per 1000 (215 to 782) | RR 0.63 (0.33 to 1.20) | 40 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | The intervention may reduce attendance for vaccinations, but the CI includes both an increase and a decrease in attendance. |

| Health behaviour change – hygiene practices | No studies reported this outcome. | — | (0 studies) | — | The effect of the intervention on hygiene practices is unknown as there was no direct evidence. | |

| Health behaviour change – correct treatment taken | No studies reported this outcome. | — | (0 studies) | — | The effect of the intervention on taking correct treatment is unknown as there was no direct evidence. | |

| Unintended consequences | No studies reported this outcome. | — | (0 studies) | — | The effect of the intervention on unintended consequences is unknown as there was no direct evidence. | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level for risk of bias: unclear risk of bias for allocation concealment, high risk of bias for incomplete outcome reporting and other bias. bDowngraded one level for imprecision: small number of events and confidence interval encompassing potential harmful effect and potential beneficial effect of the intervention.

Background

Description of the condition

The enormous burden of disease due to poor sexual, reproductive, maternal, newborn, child, and adolescent health (SRMNCAH) renders them urgent global health priorities. In 2016, poor maternal and neonatal health, and communicable and nutritional diseases, which particularly adversely affect children, accounted for more than a quarter of healthy years of life lost worldwide (Hay 2016). Neonatal preterm birth complications, HIV/AIDS, neonatal encephalopathy due to birth asphyxia and trauma, lower respiratory infections, and diarrhoeal diseases were among the 10 leading causes of total years of life lost, with the burden heavily concentrated in children under five years of age (Naghavi 2017). Those living in low‐ and middle‐income countries are disproportionately affected by poor SRMNCAH (Black 2016).

In 2015, an estimated 303,000 women died during and following pregnancy and childbirth, and maternal mortality remains a leading cause of death for adolescent women. The vast majority of these deaths occurred in low‐resource settings, and most could have been prevented (Alkema 2016). Almost three‐quarters of maternal deaths are due to direct obstetric causes, such as haemorrhage, hypertensive disorders, sepsis, abortion, embolism, and complications of labour (Say 2014). The majority of indirect causes of maternal deaths are due to the exacerbation of pre‐existing conditions; with HIV accounting for an estimated 5.5% of global maternal deaths (Say 2014). Intrinsically linked to maternal health, 1.7 million stillbirths occurred in 2016 worldwide, with key causes including pregnancy and childbirth complications, lifestyle factors, diabetes and hypertension, maternal infections, preterm birth, and birth defects (Naghavi 2017; WHO 2017). Furthermore, five million children under the age of five years died in 2016, with almost half of these deaths occurring among newborns. The three leading global causes of death in children aged under five years were lower respiratory infections, neonatal preterm birth complications, and neonatal encephalopathy due to birth asphyxia and trauma (Naghavi 2017). Of those who survive, one‐third of children fail to reach their full physical, cognitive, psychological, or socioemotional potential (or a combination of these) as a result of poverty, poor health and nutrition, insufficient care and stimulation, and other risk factors of importance to early childhood development (Every Women Every Child 2015).

Indicative of the continued global commitment to the survival and well‐being of women and children, the UN Secretary General's Global Strategy for Women's and Children's Health was launched in 2010. In 2015, this was recast as the Global Strategy for Women's, Children's and Adolescents' Health aligning its priorities with the ambitious targets relating to the improvement of sexual, reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health which feature in the Sustainable Development Goals (UN 2015). In 2011, the World Health Organization (WHO) published its global review of RMNCAH interventions, Essential Interventions, Commodities and Guidelines for Reproductive, Maternal, New‐born and Child Health, with the aim of developing consensus on the content of packages of interventions to address the main causes of maternal, newborn, and child deaths (PMNCH 2011). The health issues targeted by the recommended interventions span adolescence and prepregnancy health (e.g. prevention and management of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) including HIV, family planning, and preconception care); pregnancy (e.g. provision of safe abortion and postabortion care; appropriate antenatal care (ANC) including screening for maternal illness, preventive dietary supplements, and immunisations; prevention of pre‐eclampsia); childbirth (e.g. medical interventions such caesarean section where indicated); maternal postnatal care (e.g. detection and management of sepsis; family planning); newborn postnatal care (e.g. early initiation of exclusive breastfeeding; kangaroo care (prolonged skin‐to‐skin contact between baby and carer); detection and management of infections); and infancy and childhood (e.g. adequate nutrition; prevention and management of illness). However, despite some progress, the burden of poor sexual, reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health remains substantial. New interventions are urgently needed to support further improvement in SRMNCAH, especially in low‐ and middle‐income countries.

Description of the intervention

Targeted client communication (TCC), also referred to as health promotion messaging or behaviour change communication, is the transmission of targeted health content to a specified population or people within a predefined health or demographic group (WHO 2018). TCC can fall along a continuum of tailored communication, such as individualised or personalised notifications, as well as untailored content which draws on predetermined content developed for the identified population group (Hawkins 2008). In order to define the populations for the TCC, eligible people need to be identified and subscribed into a system that allows the transmission of the health content information. Additionally, the health system initiates the first transmission of information, rather than a client seeking information, as in telemedicine and on‐demand information services. Following this initial communication from the health system to the client, clients may subsequently respond or continue engagement with the health system, also referred to as bidirectional communication. In contrast, non‐targeted client communication (non‐TCC) is the transmission of health promotion content delivered to the general population or an undefined population.

TCC has the potential to improve RMNCAH through targeting knowledge, motivation, and behaviour change in order to increase client demand and utilisation of the essential interventions detailed in the WHO Guidelines for Reproductive, Maternal, New‐born and Child Health described above (PMNCH 2011). For example, for the successful promotion of breastfeeding, TCC may enhance the provision of health system services through the provision of education relating to breastfeeding, providing links to local services, and providing social support.

Mobile devices may be a particularly effective way of delivering TCC. Mobile phone ownership is almost universal in high‐income countries and estimated to have reached over 90% in low‐ and middle‐income countries (ICT 2016). Phones are generally carried wherever people go and can be accessed 24 hours a day. Given their broad reach, mobile devices may provide a cost‐effective mechanism for engaging with target populations and delivering health information relating to SRMNCAH.

How the intervention might work

TCC via mobile devices can be used to target the individual‐level knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours of importance for the prevention and management of health issues, including those relating to the WHO essential interventions for reproductive, maternal, new‐born, and child health (PMNCH 2011). For example, mobile device‐based interventions can (Kaufman 2017):

provide information and education relevant to the health issue being targeted (e.g. information relating to breastfeeding, adequate child nutrition, vaccinations, and the recognition of symptoms of severe childhood infections);

facilitate timely access to health advice and services when required (e.g. by providing details of local healthcare services);

provide reminders (e.g. for HIV medication adherence; for antenatal appointment attendance; for childhood vaccination appointment attendance);

provide social and psychological support for the behaviour change targeted (e.g. through the provision of encouragement and positive reinforcement; and specifically targeting of psychological factors such as lack of motivation and low self‐efficacy).

Why it is important to do this review

Mobile device‐based interventions are of particular interest given their low‐cost and potential for widespread delivery, however, the current evidence base supporting their implementation for the improvement of maternal, newborn, and child health is limited. The most recent reviews concerned with the effectiveness of mobile device‐based interventions for maternal, newborn, or child health have been limited to studies conducted in low/middle‐income countries and have included non‐randomised controlled trials, which are prone to bias (Lee 2016). Broader reviews of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of digital health interventions for healthcare consumers (e.g. Free 2013a) are in need of updating to consider the more recent emerging evidence in this field. Other reviews of relevance, concerned with preventive healthcare, reminders for appointment attendance, and self‐management of long‐term illnesses have focused specifically on SMS (short message service) and MMS (multimedia message service) mobile phone messaging (de Jongh 2012; Gurol‐Urganci 2013; Vodopivec‐Jamsek 2012), thereby excluding other phone‐based delivery mechanisms, such as voice calls, Interactive Voice Response (IVR), and mobile application delivered instant messages.

This review is one of two linked systematic reviews which were carried out to directly inform WHO guidelines on digital interventions for health system strengthening (WHO 2019). This review focuses on the effectiveness of TCC via mobile devices for maternal, newborn, and child health, and the other review examines the effectiveness of TCC via mobile devices for sexual and reproductive health (Palmer in preparation). Although the potential for mobile and digital technologies is acknowledged, there remains considerable demand from ministries of health, donors, and decision‐makers for evidence‐based guidance on the value of digital tools for improving health. In response to this global need for government decision‐makers, the WHO has developed a guideline on digital interventions for health system strengthening to inform government‐led investments. In combination, the current review, and the linked review focusing on sexual and reproductive health (Palmer in preparation) complement a qualitative evidence synthesis on the use of TCC for RMNCAH (Ames 2019); combined, these reviews aim to provide a comprehensive overview of the impact, acceptability, and implementation considerations for formulating guideline recommendations.

Objectives

The overall aim of this review was to assess the effects of TCC via mobile devices on health behaviour, service use, and health and well‐being for maternal, new‐born and child health. This review focuses on RMNCH priorities in LMIC relating to the WHO essential interventions for reproductive, maternal, new‐born and child health (PMNCH 2011).

Our specific objectives relate to three distinct populations and outcomes relevant to these populations. For each population group outlined below, we sought to determine whether targeted client communication via mobile devices can address challenges related to health and well‐being, health behaviour, and service utilization. Interventions and comparisons are the same throughout.

To assess the effects of TCC via mobile devices on behavioural, health/well‐being, and service utilisation outcomes relevant to maternal and new‐born health among pregnant and postpartum women (up to 6 weeks) and their partners or others who support them.

To assess the effects of TCC via mobile devices on behavioural, health/well‐being, and service utilisation outcomes relevant to maternal and new‐born health among pregnant and postpartum women (up to 6 weeks) living with HIV and their partners or others who support them.

To assess the effects of TCC via mobile devices, delivered to parent and caregivers (i.e. legal guardians, not healthcare professionals) of children under the age of 5 years, on behavioural, health/well‐being, and service utilisation outcomes relevant to child health

Secondary objectives

Had there been sufficient studies we planned to assess whether the effects of targeted client communication accessible via mobile devices differ according to:

Purpose of the intervention (e.g. to remind/recall versus to inform/educate or to support);

Income region (by World Bank income group) (World Bank 2017);

Delivery mechanism (e.g. voice, SMS, interactive voice response).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs). We included full‐text studies, conference abstracts, and unpublished data irrespective of their publication status and language of publication.

We excluded small‐scale studies which had randomised fewer than 20 participants.

Types of participants

We included trials with the following participants:

pregnant and postpartum women up to six weeks after birth, and their partners or others who supported them (where pregnancy status had not been disaggregated, studies in which at least 70% of women were pregnant or up to six weeks postpartum);

pregnant and postpartum women up to six weeks after birth living with HIV, and their partners or others who supported them (where HIV status had not been disaggregated, studies in which at least 70% of pregnant and postpartum women were living with HIV);

parents and carers of children aged under five years (where age had not been disaggregated, studies in which at least 70% of children were under five years of age).

Types of interventions

We included trials that assessed TCC delivered via mobile devices, where the content of the communication was intended to improve maternal, new‐born, or child health, or a combination of these.

Targeted client communication

By TCC, we mean the transmission of targeted health content to a specified population or people within a predefined health or demographic group. Unless otherwise stated, we use the terms 'clients', 'patients', and 'consumers' to refer to the individuals whose behaviour, health service use, or health and well‐being were being targeted.

We included all of the following:

studies in which the healthcare consumers were the recipients of the transmitted information;

studies in which health content was transmitted from the health system to the client, also referred to as unidirectional communication;

studies in which health content was transmitted from the client to the health system or a health worker, provided that the first communication was initiated by the health system to the client's mobile device. This can occur as bidirectional communication in which clients may respond or exchange with the health system following an initial communication from the health system to the client.

We excluded:

studies in which the communication between the client and health system was first initiated by the client. Studies in which clients initiated contact with providers were included in a separate review on client‐to‐provider telemedicine (Gonçalves‐Bradley 2018);

studies in which health content was transmitted to the general population or an undefined population group;

studies in which the client used fully automated services, including websites, to self‐care or access clinical information;

studies in which TCC was combined with a health worker tool for tracking client's health status, as this combination was included in a separate review (Agarwal 2018).

Mobile device/multimedia delivery of targeted health communication

By mobile devices, we mean mobile phones of any type (but not analogue landline telephones), as well as tablets and personal digital assistants, which facilitate communication via different multimedia channels including SMS, voice calls, IVR, MMS, and smartphone applications (apps) when used for instant messaging purposes.

We included studies that used the following communication channels:

mobile text messaging (including SMS, and unstructured supplementary service data (USSD));

MMS, including video and audiovisual messages;

IVR;

voice calls and call‐backs;

WhatsApp and other instant messaging services (such as Facebook messenger);

apps, only when they provided an instant messaging function to provide TCC.

We excluded studies that use the following communication channels:

web portals, applications, and websites that did not have a targeted communication component to notify clients (i.e. which did not provide an instant messaging function, and thereby provided passive information which relied on clients to actively access);

emails alone;

social media websites such as Facebook, Baidu, Twitter (unless there was explicit mention of the provision of instant messaging services to individuals to provide target client communication).

Mixed modes of delivery

We included studies in which the intervention delivered to mobile devices was the primary intervention component under evaluation.

When considering interventions delivered by multiple modes, we included interventions involving additional components which could have conceivably been delivered by a mobile device (e.g. an intervention delivered by SMS in combination with email, websites, social media) as all of these delivery mechanisms would allow the entire intervention to be received via a mobile device. Interventions including additional components that could not conceivably be delivered by a mobile device were excluded (e.g. an intervention delivered by SMS in combination with face‐to‐face counselling).

Content and purpose of the targeted client communication

We included TCC dealing with the health issues listed below. We derived the list of health issues from two key resources by the WHO on Essential Interventions for RMNCH:

Partnership for Maternal, Newborn & Child Health. 2011. A Global Review of the Key Interventions Related to Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn and Child Health (RMNCH) (PMNCH 2011); and

WHO, Packages of Interventions for Family Planning, Safe Abortion care, Maternal, Newborn and Child Health (WHO 2010).

For pregnant and postpartum women (up to six weeks), interventions could target:

ANC;

birth preparedness;

skilled attendant at birth;

emergency obstetric care;

postpartum care;

kangaroo mother care;

tetanus immunisation;

anaemia prevention and control;

STI testing and treatment in pregnancy;

sexual violence;

malaria prevention and treatment;

smoking cessation during pregnancy;

antiretroviral (ARV) adherence (for pregnant and postpartum women living with HIV);

early infant diagnosis (for pregnant and postpartum women living with HIV);

retention of mother and infant pairs in elimination of mother‐to‐child transmission (eMTCT) care (for pregnant and postpartum women living with HIV).

Parents and other carers of children under five years of age, interventions could target:

postnatal care;

Immunisation;

breastfeeding;

integrated management of newborn and childhood illnesses (IMNCI);

water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH);

Management of diarrhoeal illnesses, oral rehydration salts (ORS), zinc;

growth monitoring and nutrition;

early infant diagnosis in HIV‐exposed children; ARV therapy for HIV‐exposed and HIV‐infected children;

early childhood development.

Interventions could serve at least one of the following purposes (Kaufman 2017):

to inform and educate identified clients;

to remind and recall identified clients;

to teach skills to identified clients;

to provide support (i.e. for the behaviour change targeted, disease prevention, or health improvement);

facilitate decision‐making;

enable communication.

We have only included health issues that could potentially be addressed through targeted communication to the client, as opposed to those that relate to the provision of clinical care which would be targeted through communication to the healthcare provider. Further details of outcomes that were included can be found below.

Types of comparisons

We included trials with the following comparisons:

targeted communication delivered to the client via mobile device compared with standard care or no intervention;

targeted communication accessible to the client via mobile device compared with targeted, non‐digital communication (e.g. letters, face‐to‐face communication with clients);

targeted communication accessible to the client via mobile devices compared with non‐targeted, digital communication via mobile devices (e.g. digital communications which did not target issues relating to maternal, newborn or child health)

We excluded comparisons of:

one type of targeted communication accessible to the client via mobile devices compared with another type of targeted communication accessible via mobile devices held by the client (e.g. mobile messaging compared with mobile voice);

studies that compare different technical specifications of telecommunication technologies (e.g. different communication channels, software, etc.);

studies comparing TCC via mobile device in addition to another intervention that could not conceivably be delivered by mobile device (e.g. face‐to‐face counselling), compared with TCC via mobile device alone;

studies comparing TCC via mobile device in addition to another intervention that could not conceivably be delivered by mobile device (e.g. face‐to‐face counselling), compared with standard care/no intervention.

Types of outcome measures

The outcome measures extracted were according to the population targeted. Below we present the outcomes relevant for pregnant and postpartum women (up to six weeks) living without HIV and living with HIV and the outcomes extracted for children under the age of five years. We extracted both objectively measured and self‐reported outcomes for all lengths of follow‐up reported.

Where a study reported the same outcome measure for multiple time points, we extracted data for the outcome at the longest follow‐up time point. Where we identified studies that reported multiple outcome measures falling under the same outcome category, we extracted all outcome measures. For example, under the outcome category of 'partner violence', we would have extracted measures of sexual, physical, and emotional violence, to ensure that we were able to reflect different aspects within a single outcome category.

Where we identified studies that reported multiple outcome measures of the same outcome, we applied a set of rules to decide which outcome measure(s) to report in our review in order to avoid over‐representing single trials that reported on multiple measures relating to a single outcome. Where a study reported both dichotomous and continuous measures relating to a single outcome, we applied the following rules to identify one dichotomous outcome measure and one continuous outcome measure to present. The rationale for presenting both a dichotomous and a continuous outcome measure, where available, was because trials may have been underpowered to detect a difference in a clinically important dichotomous outcome (e.g. proportion adherent to medication), but may have power to detect a mean difference (MD) in the equivalent continuous outcome (e.g. MD in number of days covered by medication).

Where objective measurement was possible, we prioritised reporting an objectively measured outcome over a self‐reported outcome measure. For example, had a study included the outcome of STI status, and recorded both biochemically confirmed STI status and self‐reported STI status, we would have reported the biochemically confirmed STI status outcome. For outcomes that had not been directly objectively measured, likely for some health behaviour outcomes, we listed the outcomes of the trial (without considering either effect size or its statistical significance) and two review authors made a decision about which was most 'clinically' important or which was the most appropriate measure of the outcome under focus (or both). For example, in terms in clinical importance, if a study reported the outcome measure of attendance to at least one antenatal appointment and the outcome measure of attendance to all antenatal appointments, we presented the outcome relating to attendance to all antenatal appointments as this likely to have greater clinical impact.

Primary outcomes

Pregnant and postpartum women (living without HIV and living with HIV)

The following outcomes were identified based on the list of health issues that could be targeted by included interventions. As described above, these are based on two key resources by the WHO on Essential Interventions for RMNCH:

the Partnership for Maternal, Newborn & Child Health. 2011. A Global Review of the Key Interventions Related to Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn and Child Health (RMNCH) (PMNCH 2011); and

WHO, Packages of Interventions for Family Planning, Safe Abortion care, Maternal, Newborn and Child Health (WHO 2010).

Health behaviour change

Smoking cessation; b. alcohol consumption; c. adherence to preventive regimens for pre‐eclampsia (calcium, magnesium, low‐dose aspirin); d. adherence to antenatal regimens (e.g. folic acid); e. adherence to preventive/treatment regimens for anaemia (ante‐ and postnatal iron supplements); f. adherence to malaria prevention strategies (insecticide‐treated nets (ITNs), intermittent‐preventive treatment (IPTp) with sulphadoxine‐pyrimethamine (SP)); g. adherence to treatment for treatable infections (e.g. chlamydia, syphilis, mastitis); h. adherence to management strategies for pre‐existing conditions, e.g. diabetes; i. adherence treatment for mental health conditions; j. initiation of kangaroo care; k. initiation of breastfeeding; l. postpartum contraceptive uptake; m. adherence to deworming regimen; n. other lifestyle changes, e.g. exercise, health diet; o. adherence to ARVs (tablet count, prescription data).

Service utilisation

ANC: a. attendance for ANC appointment (e.g. more than one appointment with skilled personnel, more than four appointments with skilled personnel, attendance for vaccinations, attendance for screening, e.g. HIV, syphilis, anaemia, hypertensive disorders, attendance for malaria prevention services e.g. ITNs, IPTp with SP); b. attendance for high‐risk pregnancies (preterm, multiple pregnancies, previous maternal haemorrhage); c. attendance to eMTCT care.

Intrapartum care: a. place of birth (home, hospital); b. skilled attendant at birth.

Postnatal care: a. attendance for postpartum care appointment; b. attendance for information and counselling on nutrition, safe sex, family planning and provision of contraceptive methods; c. attendance to eMTCT care.

Postnatal care (newborn): a. attendance for postpartum care appointment.

Health status and well‐being

Maternal morbidity/mortality (physical): a. STI (any) status; b. HIV status/HIV management (CD4 count, viral load); c. tetanus; d. syphilis; e. anaemia (e.g. haemoglobin, haematocrit, ferritin); d. malaria; e. pre‐eclampsia (blood pressure); f. birth‐related complications (e.g. severe bleeding, receipt of blood transfusion, postdelivery haemoglobin, infection); g. postabortion complications (e.g. incomplete abortion, severe bleeding, infection); h. mastitis; i. maternal mortality (objective and self‐reported measures).

Maternal morbidity (mental): a. depression (validated measure); b. anxiety (validated measure); c. puerperal psychosis.

Neonatal Health: a. gestational age at birth; b. birth weight; c. Apgar score; d. perinatal death; e. neonatal death; d. HIV status.

Partner violence: a. sexual violence; b. physical violence; c. emotional violence (objective, e.g. hospital admissions and self‐report measures).

Well‐being: a. validated measures of health‐related quality of life.

Parents and other carers of children under five years of age

Health behaviour change of parent/carer

Breastfeeding: a. duration of breastfeeding; b. exclusive breastfeeding (among babies under six months of age).

Nutrition: a. introduction of complementary foods (among babies aged six to eight months); b. dietary diversity/adequacy (children aged six to 23 months who received foods from four or more food groups); c. minimum meal frequency; d. consumption of iron‐rich or iron‐fortified foods; e. adherence to vitamin A supplements.