Abstract

Background

Although Helicobacter pylori (Hp) as high risk factor for gastric cancer have been investigated from human trial, present data is inadequate to explain the effect of Hp on the changes of metabolic phenotype of gastric cancer in different stages.

Purpose

Herein, plasma of human superficial gastritis (Hp negative and positive), early gastric cancer and advanced gastric cancer analyzed by UPLC-HDMS metabolomics can not only reveal metabolic phenotype changes in patients with gastric cancer of different degrees (30 Hp negative, 30 Hp positive, 20 early gastric cancer patients, and 10 advanced gastric cancer patients), but also auxiliarily diagnose gastric cancer.

Results

Combined with multivariate statistical analysis, the results represented biomarkers different from Hp negative, Hp positive, and the alterations of metabolic phenotype of gastric cancer patients. Forty-three metabolites are involved in amino acid metabolism, and lipid and fatty acid metabolism pathways in the process of cancer occurrence, especially 2 biomarkers glycerophosphocholine and neopterin, were screened in this study. Neopterin was consistently increased with gastric cancer progression and glycerophosphocholine tended to consistently decrease from Hp negative to advanced gastric cancer.

Conclusion

This method could be used for the development of rapid targeted methods for biomarker identification and a potential diagnosis of gastric cancer.

Keywords: metabolomics, biomarkers, Helicobacter pylori, gastric cancer

Introduction

Gastric cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death worldwide. Prevention and individualized treatment are considered to be the best choice to reduce the mortality of gastric cancer.1 Currently, the evaluation of gastric cancer is mainly based on a gastroscopy or surgical biopsy reviewed by an experienced pathologist. Recently, large-scale studies on molecular subtypes have defined 4 subtypes of gastric cancer at the level of genome, transcriptome, and proteome. However, these subtypes have not had any impact on treatment.2 These clinical practices do not apply to early gastric cancer or Helicobacter pylori (Hp) positive patients.2 Hp is the dominant bacterium in human gastric microbiota, and its colonization causes persistent inflammatory response. Hp infection is a risk factor for gastric cancer3 which even develops into carcinogenesis changes through strain specific bacterial components, host reactions, or specific host microbial interactions.4 So we think Hp as the bacteria and host agents for increasing the risk of gastric cancer have profound implications for earlier detection of early cancer using region-specific and accurate biomarkers.

Metabolomics is the latest system biology technology to understand the complex disease process. A field of its application is to identify the biochemical characteristics related to the pathogenesis of the disease, which can be used for the diagnosis and monitoring of disease progress, as well as the response to treatment and intervention.5 Metabolomics is developing into a standard tool for future epidemiology and translational cancer research such as applications in clinical diagnosis of colorectal cancer, breast cancer, and bladder cancer.6–8 In the past decade, the development of liquid chromatography‐mass spectrometry (LC‐MS) has revolutionized metabolomics analysis, which led to new biomarker discoveries and a better mechanistic understanding of cancer diagnosis.9 Among them, ultra-performance liquid chromatography-quadrupole time-of-flight high-definition mass spectrometry (UPLC-QTOF/HDMS) is one of the most sensitive, selective, and reproducible analytical techniques.10,11

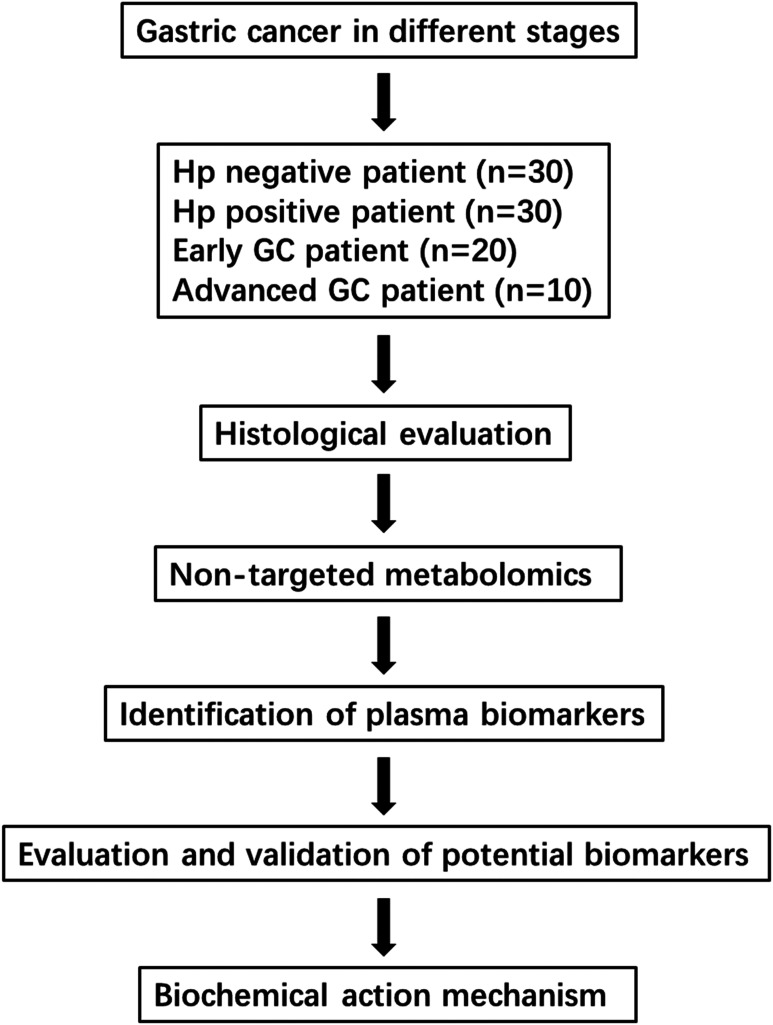

Many metabolomics studies have reported the changes of metabolites in plasma, urine, and renal tissue of gastric cancer patients.12–14 There is a lack of systematic research on simultaneous determination of Hp negative, Hp positive, early gastric cancer, and advanced gastric cancer to establish a mechanism connection. Herein, plasma of human superficial gastritis (Hp negative and positive), early gastric cancer, and advanced gastric cancer was applied to UPLC-HDMS metabolomics to reveal the altered metabolic phenotype of gastric cancer patients (study flowchart in Figure 1). Multivariate statistical analysis was used to screen the biomarkers of each cancer stages (HPP, early GC, and advanced GC) compared with HPN. This method might be an accurate, rapid, and predictive diagnosis of gastric cancer and an alternative to pathogenesis research.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study strategy in this study.

Methods

Overall Participants

The study was conducted using 90 patients containing 30 Hp negative patients (HPN), 30 Hp positive patients (HPP), and 30 gastric cancer patients with Hp positive (GC). Ethical approval was given and adhered to the requirements of the Declaration of Helsinki. This trial is based on the principles of the Helsinki Declaration and the Committee of First Hospital of Lanzhou University (approval number: LDYYLL2019-243). Each participant provided the signature and informed verbal consent of each participant. Patients in the HPN and HPP group were diagnosed as normal or superficial gastritis by gastroscopy, while the difference of these 2 groups is Hp negative or positive. Patients in GC group include 20 patients with early cancer and 10 patients with advanced cancer, which were diagnosed by gastroscopy and biopsy. The study design and clinical data for these patient groups included sample number, tube number, name, gender, age, gastroscopy or pathological diagnosis, and pathological stage (Table S2). Participants were recruited to the study between November 2019 and December 2019. Blood samples were collected at the same time period from First Hospital of Lanzhou University, Lanzhou. Plasma was separated and stored at −80°C until assayed. Data analysis was completed in February 2020.

UPLC-QTOF/HDMS Analysis

100 μL of sample was transferred to a centrifuge tube, and 400 μL extract solution (acetonitrile: methanol = 1: 1, v/v) containing internal standard (L-2- chlorophenylalanine, 2 μg/mL) was added. After 30 s vortex, the samples were exposed to ultrasonic treatment for 10 min at 0°C. Then, the samples were incubated at −40°C for 1 h and centrifuged at 10 000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. 400 μL of supernatant was transferred to a fresh tube and dried in a vacuum concentrator at 37°C. Then, the dried samples were dissolved by 200 μL of 50% acetonitrile by ultrasonic treatment at 0°C for 10 min. The mixture was then centrifuged at 13 000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C, and 75 μL of supernatant was transferred to a fresh glass vial for LC/MS analysis. The quality control (QC) samples were prepared by mixing an equal aliquot of the supernatants from all of the samples.15

The UHPLC separation was carried out using a 1290 Infinity series UHPLC System (Agilent Technologies), equipped with a UPLC BEH Amide column (2.1 * 100 mm, 1.7 μm, Waters). The mobile phase consisted of 25 mmol/L ammonium acetate and 25 ammonia hydroxide in water (pH = 9.75) (A) and acetonitrile (B). The analysis was carried with elution gradient as follows: 0∼0.5 min, 95%B; 0.5∼7.0 min, 95%∼65% B; 7.0∼8.0 min, 65%∼40% B; 8.0∼9.0 min, 40% B; 9.0∼9.1 min, 40%∼95% B; and 9.1∼12.0 min, 95% B. The column temperature was 25°C. The auto-sampler temperature was 4°C and the injection volume was 1 μL (pos) or 1 μL (neg), respectively.

The TripleTOF 6600 mass spectrometry (AB Sciex) was used for its ability to acquire MS/MS spectra on an information-dependent basis (IDA) during an LC/MS experiment. In this mode, the acquisition software (Analyst TF 1.7, AB Sciex) continuously evaluates the full-scan survey MS data as it collects and triggers the acquisition of MS/MS spectra depending on preselected criteria. In each cycle, the most intensive 12 precursor ions with intensity above 100 were chosen for MS/MS at collision energy (CE) of 30 eV. The cycle time was 0.56 s. ESI source conditions were set as following: Gas 1 as 60 lbf/in2, Gas 2 as 60 lbf/in2, Curtain Gas as 35 lbf/in2, Source Temperature as 600°C, Declustering potential as 60 V, and Ion Spray Voltage Floating (ISVF) as 5000 V or −4000 V in positive or negative modes, respectively.16

Data Preprocessing and Annotation

MS raw data (.wiff) files were converted to the mzXML format by ProteoWizard and processed by R package XCMS (version 3.2, https://xcmsonline.scripps.edu). The process includes peak deconvolution, alignment, and integration.17 Minfrac and cut off are set as 0.5 and 0.6, respectively. In-house MS2 database was applied for metabolites identification.

Data Analysis

Principal component analysis (PCA) and orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) were performed to discriminate between different stages using SIMCA software (Version 14.0, Umetrics, Umea, Sweden). The data using both negative and positive ion modes were mean-centered and UV (to find the difference, for PCA) or Pareto (to establish the model, for OPLS-DA) scaled before multivariate statistical analysis. Potential metabolites were identified by variable importance for projection (VIP) values and P values. Student’s t-test and association analysis were performed using IBM SPSS statistics software, and P value < 0.05 is considered statistically significant. Association analysis between the biomarkers and the pathological stages was analyzed based on Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient.

Results

Establishment and Validation of Metabolomics Model

As shown in Supplementary Material Figure S1, the TIC retention time and peak area of QC sample overlap well, indicating that the instrument has good stability. It also can be seen from Supplementary Material Figure S2 that good stability of standards and instruments was shown up by the retention time and peak area of internal standard l-2-chlorophenylalanine, as well as the data acquisition of the instrument is very good. As shown in Supplementary Material Figure S3, compared with the sample, the substance residues in the blank are effectively controlled. The correlation of quality control (QC) samples is close to 1 (at least ≥ 0.7) indicating the high quality and good stability of metabolomics data.

Principal component analysis of plasma in Hp negative and positive, early gastric cancer, and advanced gastric cancer group is shown in Figure 2. Gastric cancer group especially advanced gastric cancer group (C2 group in Figure 2) separated from the Hp negative and positive plasma, which reflected that the metabolites of different groups were significantly different. Parameters of PCA and OPLS-DA model are shown in Table S1. The parameters R2Y and Q2 obtained from 7-fold cross validation (Table S1) and permutation test (Supplementary Material Figure S4) show that the model had good predictability and do not overfit.

Figure 2.

Metabolomic profiling of plasma samples from 4 groups identifies metabolites that distinguish patients with Gastric Cancer: (A) 2D PCA score plot in positive ion mode; (B) 2D PCA score plot in negative ion mode. Abbreviations: PCA, principal component analysis.

Metabolomics Analysis of Plasma During Different Gastric Cancer Stages

Orthogonal partial least squares score plots of UPLC-QTOF/HDMS data were used to identify the potential metabolites (Figure S4). The permutation test was carried out to prevent models overfit (Supplementary Material Figure S5). Supplementary Material Figure S6 shows the volcano plots based on plasma metabolic profiling at the stages of HPN, HPP, early GC, and advanced GC. It was found that 321, 306, and 336 variables (VIP values greater than 1.0, P and Q value less than 0.05) at the stages of HPN, HPP, early GC, and advanced GC, respectively. Subsequently, using a combination of the Student’s t-test, these variables were selected. In addition, xenobiotics, different fragment ions from the same metabolites were excluded. Potential metabolites were identified according to the previously reported method,18 and derived from the comparison of each cancer stages (HPP, early GC, and advanced GC) with HPN. 8, 17, and 18 differential metabolites were identified as potential biomarkers from Hp negative to Hp positive to early stage to advanced stage, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Identification biomarkers of gastropathy detected by UPLC-QTOF/HDMS in the different stages.

| No. | Metabolites | VIP | FC | P value | HMDB | PubChem | KEGG | Metabolic Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hp positive | ||||||||

| 1 | Dihydrouracil | 2.57 | 0.77 | 8.24E-03 | HMDB0000076 | 649 | C00429 | Pyrimidine metabolism |

| 2 | Alpha-ketoisovaleric acid | 2.44 | 0.88 | 1.38E-02 | HMDB0000019 | 49 | C00141 | Amino acid metabolism |

| 3 | Phosphorylcholine | 2.11 | 0.85 | 7.59E-03 | HMDB0001565 | 1014 | C00588 | Lipid metabolism |

| 4 | Caprylic acid | 1.91 | 0.81 | 5.99E-03 | HMDB0000482 | 379 | C06423 | Fatty acid metabolism |

| 5 | Serine | 1.76 | 1.13 | 3.77E-02 | HMDB0000187 | 5951 | C00065 | Amino acid metabolism |

| 6 | Cystine | 1.72 | 0.85 | 1.48E-02 | HMDB0000192 | 67 678 | C00491 | Amino acid metabolism |

| 7 | Glycerophosphocholine | 1.67 | 0.76 | 7.40E-03 | HMDB0000086 | 71 920 | C00670 | Lipid metabolism |

| 8 | Neopterin | 1.53 | 2.43 | 3.66E-02 | HMDB0000845 | 4455 | C05926 | Amino acid metabolism |

| Early cancer | ||||||||

| 1 | Dodecanoic acid | 2.34 | 0.48 | 6.41E-04 | HMDB0000638 | 3893 | C02679 | Fatty acid metabolism |

| 2 | Alpha-linolenic acid | 2.22 | 0.51 | 2.83E-04 | HMDB0001388 | 5 280 934 | C06427 | Fatty acid metabolism |

| 3 | 5-Methyltetrahydrofolic acid | 2.07 | 9.40 | 3.63E-02 | HMDB0001396 | 439 234 | C00440 | Methane metabolism |

| 4 | Lysine | 1.90 | 0.74 | 6.54E-04 | HMDB0000182 | 5962 | C00047 | Amino acid metabolism |

| 5 | Capric acid | 1.83 | 0.71 | 2.35E-02 | HMDB0000511 | 2969 | C01571 | Unknown |

| 6 | Linoleic acid | 1.78 | 0.80 | 3.82E-02 | HMDB0000673 | 5 280 450 | C01595 | Fatty acid metabolism |

| 7 | Isoleucine | 1.69 | 1.47 | 4.72E-03 | HMDB0000172 | 6306 | C00407 | Amino acid metabolism |

| 8 | Neopterin | 1.66 | 2.68 | 3.74E-02 | HMDB0000845 | 4455 | C05926 | Amino acid metabolism |

| 9 | Caprylic acid | 1.63 | 0.73 | 6.41E-03 | HMDB0000482 | 379 | C06423 | Fatty acid metabolism |

| 10 | Arachidonic acid | 1.62 | 0.47 | 1.21E-03 | HMDB0001043 | 444 899 | C00219 | Arachidonic acid metabolism |

| 11 | Uridine | 1.61 | 0.75 | 1.00E-03 | HMDB0000296 | 6029 | C00299 | Pyrimidine metabolism |

| 12 | Alpha-ketoisovaleric acid | 1.54 | 0.71 | 1.42E-03 | HMDB0000019 | 49 | C00141 | Amino acid metabolism |

| 13 | Estradiol | 1.45 | 0.78 | 1.29E-02 | HMDB0000151 | 5757 | C00951 | Steroid hormone biosynthesis |

| 14 | Biotin | 1.44 | 0.74 | 6.32E-04 | HMDB0000030 | 171548 | C00120 | Biotin metabolism |

| 15 | Glycerophosphocholine | 1.37 | 0.82 | 4.03E-03 | HMDB0000086 | 71 920 | C00670 | Lipid metabolism |

| 16 | Glycine | 1.20 | 1.23 | 3.83E-02 | HMDB0000123 | 750 | C00037 | Amino acid metabolism |

| 17 | Cystine | 1.09 | 0.81 | 7.95E-03 | HMDB0000192 | 67 678 | C00491 | Amino acid metabolism |

| Advanced cancer | ||||||||

| 1 | 5-Methyltetrahydrofolic acid | 2.59 | 17.90 | 4.58E-03 | HMDB0001396 | 439 234 | C00440 | Methane metabolism |

| 2 | Uridine | 2.27 | 0.49 | 7.04E-07 | HMDB0000296 | 6029 | C00299 | Pyrimidine metabolism |

| 3 | Glycerophosphocholine | 2.24 | 0.62 | 1.02E-07 | HMDB0000086 | 71 920 | C00670 | Lipid metabolism |

| 4 | Lysine | 2.18 | 0.68 | 1.08E-02 | HMDB0000182 | 5962 | C00047 | Amino acid metabolism |

| 5 | Arginine | 2.12 | 0.60 | 1.23E-05 | HMDB0000517 | 6322 | C00062 | Amino acid metabolism |

| 6 | Phosphorylcholine | 2.11 | 0.54 | 2.15E-05 | HMDB0001565 | 1014 | C00588 | Lipid metabolism |

| 7 | Dodecanoic acid | 2.01 | 0.31 | 5.37E-08 | HMDB0000638 | 3893 | C02679 | Fatty acid metabolism |

| 8 | 5′-methylthioadenosine | 2.01 | 1.79 | 5.03E-03 | HMDB0001173 | 439 176 | C00170 | Amino acid metabolism |

| 9 | Biotin | 1.99 | 0.54 | 1.96E-06 | HMDB0000030 | 171 548 | C00120 | Biotin metabolism |

| 10 | Pseudouridine | 1.95 | 1.45 | 4.62E-03 | HMDB0000767 | 15 047 | C02067 | Pyrimidine metabolism |

| 11 | 4-Pyridoxic acid | 1.93 | 8.16 | 2.99E-02 | HMDB0000017 | 6723 | C00847 | Vitamin B6 metabolism |

| 12 | Histamine | 1.82 | 2.44 | 1.15E-02 | HMDB0000870 | 774 | C00388 | Amino acid metabolism |

| 13 | Alpha-linolenic acid | 1.78 | 0.42 | 1.17E-06 | HMDB0001388 | 5 280 934 | C06427 | Fatty acid metabolism |

| 14 | Neopterin | 1.74 | 3.43 | 2.97E-03 | HMDB0000845 | 4455 | C05926 | Amino acid metabolism |

| 15 | Pyridoxamine | 1.63 | 2.17 | 1.89E-02 | HMDB0001431 | 1052 | C00534 | Vitamin B6 metabolism |

| 16 | Arachidonic acid | 1.61 | 0.42 | 1.22E-03 | HMDB0001043 | 444 899 | C00219 | Arachidonic acid metabolism |

| 17 | Estradiol | 1.57 | 0.64 | 1.02E-03 | HMDB0000151 | 5757 | C00951 | Steroid hormone biosynthesis |

| 18 | N6-acetyl-L-lysine | 1.53 | 1.39 | 8.45E-03 | HMDB0000206 | 92 832 | C02727 | Amino acid metabolism |

Abbreviations: VIP: variable importance for projection; KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes.

Reviewing patients at all stages, we inputted all the potential metabolites summarized in Table 1 to the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway database to get the metabolic pathways information. As a results, they can be classified into 2 major metabolic pathways: the first category is amino acid metabolism involve alpha-ketoisovaleric acid, serine and cystine in HPP, lysine, isoleucine, neopterin, alpha-ketoisovaleric acid, glycine, cystine, and neopterin in early GC, as well as lysine, arginine, 5′-methylthioadenosine, histamin, neopterin, and N6-acetyl-n-lysine in advanced GC; second category is lipid and fatty acid metabolism, including phosphorylcholine, caprylic acid, and glycerophosphocholine in HPP, dodecanoic acid, alpha-linolenic acid, linoleic acid, caprylic acid, arachidonic acid, and glycerophosphocholine in early GC, as well as glycerophosphocholine, phosphorylcholine, dodecanoic acid, alpha-linolenic acid, and arachidonic acid in advanced GC. These 2 categories of potential metabolites account for 70% (30 of total 43) of all differential metabolites. In fact, amino acid and fatty acid metabolic pathways and related metabolites are potential pathways or biomarkers in the process of cancer occurrence, which are often used for early detection of cancer.

Biomarkers of Early Gastric Cancer

Eight metabolites showed response in HPP patients, and seventeen metabolites showed in early GC patients. Most importantly, the decline in alpha-ketoisovaleric acid, caprylic acid, and L-cystine was observed in GC patients prior to detectable changes in conventional chemical markers. The alterations of these metabolites were most dramatic at the HPP and early GC and less pronounced at the advanced GC and as such represent potential biomarkers for the early detection of GC.

Biomarkers of Advanced Gastric Cancer

Seventeen of metabolites showed response in early GC patients, and eighteen of metabolites showed response in advanced GC patients. Among them, 5-methyltetrahydrofolic acid, uridine, L-lysine, dodecanoic acid, biotin, alpha-linolenic acid, arachidonic acid, and estradiol could be used as biomarkers of advanced GC.

Biomarkers of Progressive Gastric Cancer

Glycerophosphocholine and neopterin were significantly altered in early or advanced GC patients. To identify biomarkers of progressive GC from early stage to advanced stage during the course of the GC, the principle applied for selecting identified metabolites was unidirectionally changed across the different GC stages. Metabolites increased in one stage and decreased in another stage were not selected. By applying this selection principle, a subset of 2 metabolites including neopterin was consistently increased with GC progression, whereas glycerophosphocholine tended to consistently decrease with GC progression from Hp negative, Hp positive, early GC to advanced GC (Figure 3). Heatmap shows that GC patients and control group can be clearly separated (Figure 3). Therefore, these metabolites could potentially serve as biomarkers for progressive GC. In addition, we can also find 8 consistent biomarkers in the early and advanced stages as shown in Supplementary Material Figure S7. These 8 biomarkers are dodecanoic acid, alpha-linolenic acid, 5-methyltetrahydrofolic acid, lysine, arachidonic acid, uridine, estradiol, and biotin, respectively.

Figure 3.

Box-and-whisker plot analysis and heatmap analysis based on orthogonal partial least squares-discriminant analysis models of Gastric Cancer patients. (A) Heatmap of 2 significantly altered plasma metabolites (glycerophosphocholine and neopterin); (B) and (C) 2 significantly altered plasma metabolites (glycerophosphocholine and neopterin) in the different stages. The letters of A, B, C1, and C2 represent the Hp negative patients, Hp positive patients, early gastric cancer patients, and advanced gastric cancer patients, respectively. Different lowercase letters show significant differences at p < 0.05. Abbreviations: Hp, Helicobacter pylori.

Biomarkers Validation by Progressive Gastric Cancer Patients

To confirm the usefulness of 2 biomarkers glycerophosphocholine and neopterin of progressive GC, we used these 2 metabolites independently for multivariate analysis in all samples. As shown in Figure 4, the suitability of the identified metabolites for use as biomarkers of progressive gastric cancer was examined by ROC analysis. These 2 biomarkers had an AUC of more than 0.75 for detecting progressive gastric cancer. Furthermore, glycerophosphocholine and neopterin had high predictive performance and had high sensitivity and specificity. Therefore, these 2 metabolites could be used as effective plasma biomarkers for the detection of progressive gastric cancer.

Figure 4.

ROC analysis based on OPLS-DA models of Gastric Cancer patients biomarkers. ROC curve of the diagnostic performance of the significantly altered plasma metabolites (A) glycerophosphocholine and (B) neopterin. (C) The AUC, 95% confidence interval, sensitivity, and specificity for 2 metabolites were mentioned. Abbreviations: AUC: area under curve; OPLS-DA: orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis; ROC, receiver operating characteristic curve.

Discussion

As a fingerprint, plasma mass spectrometry can reflect the different changes of protein, nucleic acid, lipid, and other biological molecules in different organisms and infer the physiological changes of the organism, so as to diagnose the disease. Present research is focus on the effect of Hp on metabolic phenotype in patients with gastric cancer so our all clinical samples are gastric cancer patients with Hp, so the limitations of this study is the patient without Hp, which needs further research. Through this study, we have demonstrated that it is possible to completely separate GC patients with HPN, HPP, early GC, and advanced GC of all 4 major stages from subjects using both unsupervised PCA and supervised OPLS-DA applied to UPLC-QTOF/HDMS spectra of human plasma. Furthermore, using the 2 critical biomarkers glycerophosphocholine and neopterin, it is possible to predict the status of progressive GC patients using a data set composed of only 30 individuals with HPN, 30 individuals with HPP, and 30 individuals with GC. Substantially larger training sets obtained through application of this technique to clinical practice should further improve the diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of the technique.

Although Hp as high risk factor for gastric cancer have been investigated from human trial, present data is inadequate to explain the effect of Hp on the changes of metabolic phenotype of gastric cancer in different stages. At the beginning of this study, about dozens of metabolites was selected as biomarkers (Table 1). After our comparison and selection, 2 biomarkers glycerophosphocholine and neopterin were screened in this study. Neopterin was consistently increased with GC progression, whereas glycerophosphocholine tended to consistently decrease with GC progression from HPN to HPP to early GC to advanced GC. Glycerophosphocholine has the potential to treat and prevent a variety of biochemical diseases. From the viewpoint of biochemistry, glycerophosphocholine could be considered as the products of 1-acyl-lysophosphatidylcholine hydrolyzed by phospholipase B1.19 At the view of metabolomic studies of human gastric cancer, Jayavelu et al found 1-acyl-lysophosphatidylcholine and polyunsaturated fatty acids are the key metabolites in human gastric cancer.20 The biosynthetic and degradation pathways of 1‐acyl‐lysophosphatidylcholines belonging to other lipid metabolism pathways can be used to allow effective targeting of treatments such as modulating the chemosensitivity of gastric cancer to cytotoxic drugs.21–23

Another study compared the difference of plasma neopterin level between normal people and gastric cancer patients and found that the neopterin level of patients was higher than that of the control group,24, which may be caused by the differences of metabolism of amino acids especially in arginine and proline metabolism between normal people and patients with GC. Similar results were also found in the serum of advanced cancers of the digestive tract, indicating that different cancers may have similar changes in amino acids metabolism.25 In terms of the relationship between biological effects and clinical reactions, the increase of neopterin would negatively effect on the therapeutic effect of tumor, which also shows the importance of host biological response in mediating the effect of immunotherapy.26 This finding may be applied to the chemo-immunotherapeutic combination for advanced tumors in the future.27

Reviewing patients at all stages, they can be classified into 2 major metabolic pathways as shown in result: the first category is amino acid metabolism and second category is lipid and fatty acid metabolism. In fact, amino acid and fatty acid metabolic pathways and related metabolites are potential pathways or biomarkers in the process of cancer occurrence, which are often used for early detection of cancer. Recent researches have revealed dramatic changes in the amino acid profile of 5 types of cancer patients and its application for early detection.28,29 The plasma arginine concentrations have been shown to be significantly lower in advanced cancer patients than in healthy subjects.30 Due to the changes of amino acid metabolism in GC patients, tryptophan and kynurenine could be attributed to indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase upregulation in cancer patients leading to tryptophan depletion and kynurenine metabolites generation,31 which is consistent with our results. In fact, alternation of plasma amino acids is mainly due to the changes of amino acid transporters in cancer patients.32 It has been reported that altered plasma amino acids work in concert with fatty acids in exacerbating cancer progression.33 The phospholipid fatty acid metabolites including oleic acid, di-homo-γ-linolenic acid, α-linolenic acid, and the ratio of MUFAs to saturated fatty acids have been observed positive risk associations for gastric cancer.34 Nude mice with human gastric cancer cells have been reported to be delayed by omega-3 fatty acids and medium-chain triglycerides.35 The observed changes in plasma fatty acids may be due to highly expressed fatty acid synthase in different cancer tissues.36 It may reflect the changes of complex diet pattern and fatty acid metabolism, which may be a potential therapeutic target in cancer.37

In conclusion, plasma of human superficial gastritis (Hp negative and positive), early gastric cancer, and advanced gastric cancer applied to UPLC-HDMS metabolomics can not only reveal metabolic phenotype changes in patients with gastric cancer of different degrees, but also auxiliarily diagnose gastric cancer. Application of multivariate statistical analysis visually represented biomarkers different from Hp negative, Hp positive, and the alterations of metabolic phenotype of gastric cancer patients. Forty-three metabolites are involved in amino acid metabolism and lipid and fatty acid metabolism pathways in the process of cancer occurrence, especially 2 biomarkers glycerophosphocholine and neopterin were screened in this study. Neopterin was consistently increased with gastric cancer progression, and glycerophosphocholine tended to consistently decrease from Hp negative to advanced gastric cancer. This method might be an accurate, rapid, and predictive diagnosis of gastric cancer and an alternative to pathogenesis research.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-1-ccx-10.1177_10732748211041881 for Effect of Helicobacter Pylori on Plasma Metabolic Phenotype in Patients With Gastric Cancer by Yan-Ping Wang, Ting Wei, Xiao Ma, Xiao-Liang Zhu, Long-Fei Ren, Lei Zhang, Fang-Hui Ding, Xun Li, Hai-Ping Wang, Zhong-Tian Bai, Ke-Xiang Zhu, Long Miao, Jun Yan, Wen-Ce Zhou, Wen-Bo Meng and Yu-Qin Liu in Cancer Control

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by the Health Industry Research Project of Gansu Province (No. GSWSKY2016-10), the Gansu Province Science Foundation for Distinguished Young Scholars (No. 1606RJDA317), the Key Laboratory of Biotherapy and Regenerative Medicine of Gansu Province (No. zdsyskfkt-201704), the Lanzhou University serves Gansu Province Economic and Social Development Special Research Project (0411181424), and the Foundation of The First Hospital of Lanzhou University (Nos. ldyyyn2017-29;ldyyyn2017-08).

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

ORCID iD

Yan-Ping Wang https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9473-1063

References

- 1.Hartgrink HH, Jansen EP, van Grieken NC, van de Velde CJ. Gastric cancer. The Lancet. 2009;374(9688):477-490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network . Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;513(7517):202-209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forman D, Burley VJ. Gastric cancer: global pattern of the disease and an overview of environmental risk factors. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;20(4):633-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Polk DB, Peek RM, Jr. Helicobacter pylori: gastric cancer and beyond. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10(6):403-414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liesenfeld DB, Habermann N, Owen RW, Scalbert A, Ulrich CM. Review of mass spectrometry-based metabolomics in cancer research. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22(12):2182-2201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang H, Tso VK, Slupsky CM, Fedorak RN. Metabolomics and detection of colorectal cancer in humans: a systematic review. Future Oncol. 2010;6(9):1395-1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhadwal P, Dahiya D, Shinde D, et al. LC-HRMS based approach to identify novel sphingolipid biomarkers in breast cancer patients. Sci Rep. 2020;10:4668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng Y, Yang X, Deng X, et al. Metabolomics in bladder cancer: a systematic review. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(7):11052-11063. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cui L, Haitao Lu, Yie L. Challenges and emergent solutions for lc-ms/ms based untargeted metabolomics in diseases. Mass Spectrom Rev. 201837(6):772-792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fan L, Zhang W, Yin M, et al. Identification of metabolic biomarkers to diagnose epithelial ovarian cancer using a UPLC/QTOF/MS platform. Acta Oncologica. 2012;51(4):473-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoshida M, Hatano N, Nishiumi S, et al. Diagnosis of gastroenterological diseases by metabolome analysis using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Gastroenterol. 2012;47(1):9-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lario S, Ramírez-Lázaro MJ, Sanjuan-Herráez D, et al. Plasma sample based analysis of gastric cancer progression using targeted metabolomics. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):17774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan AW, Mercier P, Schiller D, et al. 1H-NMR urinary metabolomic profiling for diagnosis of gastric cancer. Br J Canc. 2016;114(1):59-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu H, Xue R, Tang Z, et al. Metabolomic investigation of gastric cancer tissue using gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2010;396(4):1385-1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dunn WB, Broadhurst D, Broadhurst D, et al. Procedures for large-scale metabolic profiling of serum and plasma using gas chromatography and liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry. Nat Protoc. 2011;6(7):1060-1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang J, Zhang T, Shen X, et al. Serum metabolomics for early diagnosis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by UHPLC-QTOF/MS. Metabolomics. 2016;12(7):116. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith CA, Want EJ, O'Maille G, Abagyan R, Siuzdak G. XCMS: processing mass spectrometry data for metabolite profiling using nonlinear peak alignment, matching, and identification. Anal Chem. 2006;78(3):779-787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen D-Q, Cao G, Chen H, et al. Identification of serum metabolites associating with chronic kidney disease progression and anti-fibrotic effect of 5-methoxytryptophan. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang X, Yan S-K, Dai W-X, Liu X-R, Zhang W-D, Wang J-J. A metabonomic approach to chemosensitivity prediction of cisplatin plus 5-fluorouracil in a human xenograft model of gastric cancer. Int J Canc. 2010;127(12):2841-2850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jayavelu ND, Bar NS. Metabolomic studies of human gastric cancer: Review. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(25):8092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burke JE, Dennis EA. Phospholipase A2 biochemistry. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2009;23(1):49-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xiao S, Zhou L. Gastric cancer: Metabolic and metabolomics perspectives (Review). Int J Oncol. 2017;51(1):5-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jackson SK, Abate W, Tonks AJ. Lysophospholipid acyltransferases: novel potential regulators of the inflammatory response and target for new drug discovery. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2008;119(1):104-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Unal B, Kocer B, Altun B, et al. Serum neopterin as a prognostic indicator in patients with gastric carcinoma. J Invest Surg. 2009;22(6):419-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lissoni P, Barni S, Tancini G, et al. Immunotherapy with subcutaneous low-dose interleukin-2 and the pineal indole melatonin as a new effective therapy in advanced cancers of the digestive tract. Br J Canc. 1993;67(6):1404-1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rupert P, Bernhard W, et al. Neopterin: a prognostic variable in operations for lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;70(6):1861-1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beutner U, Lorenz U, Illert B, et al. Neoadjuvant therapy of gastric cancer with the human monoclonal IgM antibody SC-1: Impact on the immune system. Oncol Rep. 2008;19(3):761-769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miyagi Y, Higashiyama M, Gochi A, et al. Plasma free amino acid profiling of five types of cancer patients and its application for early detection. PloS One. 2011;6(9):e24143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maeda J, Higashiyama M, Imaizumi A, et al. Possibility of multivariate function composed of plasma amino acid profiles as a novel screening index for non-small cell lung cancer: a case control study. BMC Canc. 2010;10(1):690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vissers YL, Dejong CH, Luiking YC, Fearon KC, von Meyenfeldt MF, Deutz NE. Plasma arginine concentrations are reduced in cancer patients: evidence for arginine deficiency? The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2005;81(5):1142-1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuligowski J, Sanjuan-Herráez D, Vázquez-Sánchez MA, et al. Metabolomic analysis of gastric cancer progression within the correa’s cascade using ultraperformance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Proteome Res. 2016;15(8):2729-2738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fuchs BC, Bode BP. Amino acid transporters ASCT2 and LAT1 in cancer: partners in crime? Seminars in Cancer Biology. 2005;15(4):254-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Z, Zhang H. Reprogramming of glucose, fatty acid and amino acid metabolism for cancer progression. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73(2):377-392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chajès V, Jenab M, Romieu I, et al. Plasma phospholipid fatty acid concentrations and risk of gastric adenocarcinomas in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition (EPIC-EURGAST). The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2011;94(5):1304-1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Otto C, Kaemmerer U, Illert B, et al. Growth of human gastric cancer cells in nude mice is delayed by a ketogenic diet supplemented with omega-3 fatty acids and medium-chain triglycerides. BMC Canc. 2008;8(1):122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kusakabe T, Nashimoto A, Honma K, Suzuki T. Fatty acid synthase is highly expressed in carcinoma, adenoma and in regenerative epithelium and intestinal metaplasia of the stomach. Histopathology. 2002;40(1):71-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Flavin R, Peluso S, Nguyen PL, Loda M. Fatty acid synthase as a potential therapeutic target in cancer. Future Oncol. 2010;6(4):551-562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-1-ccx-10.1177_10732748211041881 for Effect of Helicobacter Pylori on Plasma Metabolic Phenotype in Patients With Gastric Cancer by Yan-Ping Wang, Ting Wei, Xiao Ma, Xiao-Liang Zhu, Long-Fei Ren, Lei Zhang, Fang-Hui Ding, Xun Li, Hai-Ping Wang, Zhong-Tian Bai, Ke-Xiang Zhu, Long Miao, Jun Yan, Wen-Ce Zhou, Wen-Bo Meng and Yu-Qin Liu in Cancer Control