Abstract

Cancer vaccination using tumor antigen-primed dendritic cells (DCs) was introduced in the clinic some 25 years ago, but the overall outcome has not lived up to initial expectations. In addition to the complexity of the immune response, there are many factors that determine the efficacy of DC therapy. These include accurate administration of DCs in the target tissue site without unwanted cell dispersion/backflow, sufficient numbers of tumor antigen-primed DCs homing to lymph nodes (LNs), and proper timing of immunoadjuvant administration. To address these uncertainties, proton (1H) and fluorine (19F) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) tracking of ex vivo pre-labeled DCs can now be used to non-invasively determine the accuracy of therapeutic DC injection, initial DC dispersion, systemic DC distribution, and DC migration to and within LNs. Magnetovaccination is an alternative approach that tracks in vivo labeled DCs that simultaneously capture tumor antigen and MR contrast agent in situ, enabling an accurate quantification of antigen presentation to T cells in LNs. The ultimate clinical premise of MRI DC tracking would be to use changes in LN MRI signal as an early imaging biomarker to predict the efficacy of tumor vaccination and anti-tumor response long before treatment outcome becomes apparent, which may aid clinicians with interim treatment management.

Key words: Dendritic cell, Antigen presentation, Cancer vaccination, Magnetic resonance imaging, Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles, Fluorine emulsions, Cell tracking

Introduction

Dendritic cells (DCs) are professional antigen-presenting cells (APCs) of the myeloid and lymphoid lineage and are one of the first responders of our immune system with an overall versatile controlling role [1]. These lymphoid cells continuously traverse throughout our body, engulfing live and dead cells, with subsequent migration to lymph nodes (LNs) where they present non-self-epitopes (antigens) on their cell surface including those expressed by tumor cells [2]. Discovered in 1973 [3], their name is derived from the Greek word δεηδρον (tree), which refers to their tree-branch cell membrane protrusions leading to a large surface enhancement through which CD4 and CD8 T cells have ample access to bind their antigen-specific receptors to presented antigens in conjunction with recognition of the major histocompatibility complexes (MHC) I and II (Fig. 1). Since cancer cells often escape our adaptive immune system, DCs have garnered much interest as anti-tumor immune boosters through isolating them from peripheral blood and priming them ex vivo with tumor antigens [4] followed by reintroduction with or without immunoadjuvants into the patient, a process known as cancer vaccination [5].

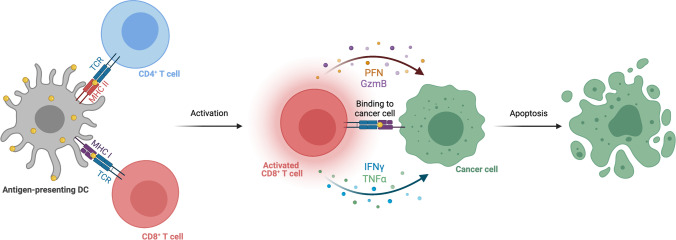

Fig. 1.

Antigen presentation of DCs, activation of cytotoxic T effector cells, and tumor apoptosis. With the help of CD4 + T cells, cytotoxic CD8 + T cells are activated upon tumor antigen and MHC I and II class molecule presentation by DCs but only when both types of T cells carry the proper antigen-recognizing receptor. Following clonal expansion, they recognize the same antigen expressed by tumor cells, following which they induce tumor cell apoptosis through the perforin (PFN)/granzyme B (GzmB) pathway with the help of interferon gamma (IFNγ) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα).

The first clinical trial using DCs as tumor vaccine was reported in 1995 [6]. In 2010, Sipuleucel-T (PROVENGE®) became the first approved dendritic cell cancer vaccine for the treatment of prostate adenocarcinoma [7]. However, since then, no other therapeutic cancer vaccines have been approved, and uncertainties with FDA approval of cancer vaccines remain [8]. Aside from tumor cell intrinsic and local or systemic immunosuppressive (extrinsic) mechanisms responsible for vaccination failure, much remains unknown about the fate of DCs once injected. In particular, for intranodal injection in regional draining LNs, it is in most cases not known if cells are indeed injected correctly, without undesired reverse backflow, and how many LNs are accumulating the injected cells. The same holds true for intradermal or intravenous (systemic) injections, with the best injection route having been debated for some time [9]. For instance, it has been estimated that less than 5% of intradermally administered mature DCs reach the draining LNs [10]. Immunoadjuvants can be administered that activate DCs and drive their migration [11], but the overall effect and best timing of giving these immunostimulators (pre-, co-, or post-injection of DCs) are murky at best.

Hence, non-invasive, whole-body imaging of the entire process of DC injection, migration, and antigen presentation is highly desirable [12]. Given its exquisite soft tissue contrast, high spatial resolution, ubiquitous availability, the existence of clinically approved DC labeling agents, and last but not least, the capability to perform true real-time imaging to guide local cell injection, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of labeled DCs is now considered to be the most comprehensive tool available to further guide cancer vaccine development.

Direct Pre-labeling or Ex Vivo Labeling of DCs with SPIO for 1H MRI

Superparamagnetic iron oxides (SPIOs) are the most widely used cell labeling agents due their relative higher sensitivity of cell detection with clinical 1H MRI compared to clinical 19F MRI, which is in the order of 1.5 × 105 DCs in a human LN [13], whereas ~ 5 × 106 cells are needed for visualization with 19F MRI [14] (see below), both at 3 T. For pre-clinical 1H SPIO MRI and 19F MRI at higher field strengths (> 9.4 T), the detection sensitivity is 100 × higher, reported as ~ 2 × 103 SPIO-labeled cells in mouse LN [15] and ~ 4 × 104 PFC-labeled cells in mouse brain [16]. A general scheme for direct pre-labeling of DCs is shown in Fig. 2. Lymphoid cells including DCs can be labeled with a variety of methods such as antibody-conjugated SPIOs [17–20], SPIO-liposomes [21, 22], poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) nanoparticles [23], iron oxide–zinc oxide core–shell nanoparticles [24], “carbonized” SPIOs [25], polystyrene beads coated with SPIO by means of a layer-by-layer technique [26], SPIO combined with protamine sulfate [15] or poly-L-lysine [27], SPIOs coated with an amphiphilic alkylated low-molecular-weight polyethyleneimine [28], or transfection agent coated and quantum dot (QD)-doped SPIO allowing multimodal MRI/near-infrared imaging [29]. By coating SPIO with an antigen such as ovalbumin, it is possible to simultaneously label and prime DCs with antigen [30, 31].

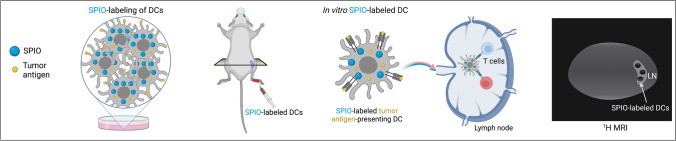

Fig. 2.

Direct pre-labeling or ex vivo labeling of DCs with SPIO for 1H MRI. DCs are first pulsed with tumor antigen (to prevent label dilution) and then labeled with SPIO for 24–48-h incubation. Shown is a pre-clinical example where DCs are injected into the footpad and accumulate in regional LNs (i.e., popliteal LNs) where tumor vaccination takes place. DCs homing to LNs show up as hypointensities on 1H MRI.

An alternative to the use of non-SPIO nanoparticles for 1H MRI is gadolinium-doped gold-Prussian blue nanoparticles, which as bimodal agent also enable visualization on surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopic (SERS) imaging [32]. A radically different approach is to transduce DCs with ferritin [33], which stores excess iron inside their protein cages. While the advantage is continuing production of the protein following cell division, DCs need to be pre-loaded with excess iron, and it is not clear how much free iron is available in vivo to continue forming anti-ferromagnetic iron oxide cores and what the loading factor [34] would be.

In general, no significant adverse effects have been observed following labeling with the appropriate SPIO concentration as far as DC survival, maturation, antigen presentation, and/or surface marker expression is concerned in vitro and in vivo both in small [28, 35–41] and large [42] animal models. However, it was shown that the migration of SPIO-labeled DCs can somewhat be decreased compared to unlabeled cells, in particular when using larger size micron-sized particles of iron oxide (MPIO) [43]. Interestingly, impairment of migration could be partially rescued by magnetic cell separation of labeled and unlabeled cells [44]. It is possible that the magnetic separation resolved some of the cell aggregates, as it has reported that large clusters/high densities of DCs can have an impaired migration [45]. High concentrations of SPIO can enhance immature DC maturation, possibly through an autophagy-related pathway [46].

A historic day was April 26, 2004, when the first cancer patient was injected in the Netherlands with SPIO (Endorem® aka Feridex®)-labeled DCs (Fig. 3) [13]; this day represents the start of the first clinical MRI cell tracking trials in general. SPIO-labeled dendritic cells were primed with synthetic melanoma antigens and injected under ultrasound (US) imaging guidance into the regional draining LNs in patients with advanced stage melanoma. Aside from visualization of DCs migrating to several (up to five) nearby LNs, a major surprise was that cells were mis-injected in 4 out of 8 patients, a result that would preclude any effective form of immunotherapy. It is likely that real-time MRI-guided injections instead of using US for needle placement would improve accuracy, as exemplified for SPIO-labeled mesenchymal stem cells [47, 48] and encapsulated pancreatic islet cells [49]. One can imagine a situation in the interventional MRI scanner procedure room where a less-experienced radiologist (possibly a first-year resident) performs a mis-injection, but this can be immediately identified and corrected on the spot. With half the injected cell population being labeled with SPIO and the other half with 111In-oxine, the detection of LNs that contained migrated DCs was more accurate with MRI compared to SPECT, due to its higher resolution and superior multi-planar imaging nature (Fig. 3). Aside from this, due to its lack of anatomical information and the need for post-image acquisition overlay with CT, SPECT cannot be used for real-time image-guided injections.

Fig. 3.

Clinical 1H MRI cell tracking of DCs using direct/ex vivo pre-labeling. Monocytes are obtained by cytapheresis from stage III melanoma patients and differentiated into mature DCs. Half of this DC population is labeled with SPIO for 48 h in culture and the other half for 15 min with 111In-oxine as SPECT radiotracer. A total of 1.5 × 107 DCs are then injected intranodally into a regional draining LN basin, and their biodistribution is monitored in vivo by 3 T 1H MRI and scintigraphy. After resection, individual LNs are also visualized ex vivo with high-resolution 7 T MRI. The far right panel with actual data is reproduced, with permission, from Ref. [13].

The production of the original clinical SPIO formulations Feridex®(aka Endorem®) and Resovist® has been discontinued for some time now in Europe and the USA, but to the best of our knowledge, Resovist® is still being sold and used in Japan. Feridex®/Endorem® was approved for use as a liver agent by the FDA in 1996, and their patents have since then long expired. A primary reason for discontinuation in terms of cost-effectiveness is that nowadays, the quality of abdominal MRI has advanced in such a manner that these liver contrast agents are no longer needed for an accurate detection of primary and metastatic hepatic tumor lesions. Possible SPIO alternatives that are currently on the market include Feraheme®, Magtrace®, SentiMag®, Sienna®, NanoTherm®, and Ferrotran®, but these formulations consist of ultrasmall SPIO (USPIO) not yet fully optimized for ex vivo cell labeling and MRI.

Aside of the critically important verification of targeted injections, how can we use the information obtained by MRI DC tracking to our advantage to better design clinical trials? One could hypothesize that the decreased LN MR imaging signal intensity may be used as an early imaging biomarker for the efficacy of cancer vaccination [50]. Indeed, in pre-clinical models, it has been shown that the T2*-weighted MRI intensity in LN has a strong correlation of DC trafficking and can be a predictor of a successful anti-tumor response. MRI predicted that “responding” DCs identified 2 days after vaccination had significantly smaller tumors 2 − 5 weeks after treatment and with animals living 73% longer than MRI-predicted “non-responders” [22]. Similarly, there was a correlation between post SPIO-labeled injection T2-weighted SNR decreases in the draining LN 24 h after injection and tumor sizes (R = 0.8) [51]. However, in the latter study, the DC vaccination did not lead to regression of the tumor but merely delayed its growth as compared with tumor growth in unvaccinated control mice.

Direct Pre-labeling or Ex Vivo Labeling of DCs with Fluorinated Emulsions for 19F MRI

The approach for direct pre-labeling is shown in Fig. 4, which essentially follows the same protocol described above but then using perfluorocarbons (PFCs) instead of SPIOs. The first 19F MRI cell tracking study was published in 2005, using PFC emulsion-labeled DCs [52]. There are certain advantages of 19F MRI over 1H MRI cell tracking [53], chief amongst which is the ease of image interpretation, where labeled cells appear as “hot spots” [54] instead of the at times ambiguous 1H MRI hypointense signal, the ability to directly quantify cells in vivo (“in vivo cytometry”) [55] by virtue of the direct detection of the 19F nucleus acting as a tracer agent instead of a contrast agent, and the ability to detect cells in organs that have intrinsic hypointensities on 1H MRI, such as the air-filled lung and colon [56]. On average, labeled DCs contain ~ 0.5–2 × 1013 19F atoms per cell [52, 57]. There has been much activity in developing optimized 19F MRI cell labeling tracers and clinical protocols [58]. Lager perfluoro-15-crown-5-ether (PFCE) particles in the order of 560 nm were shown to have a better DC labeling efficacy with more 19F signal but altered the maturation state and phagocytic activity of DCs [59]. Large 19F nanoparticles can be synthesized using PLGA and customized in terms of content (imaging agent, fluorescent dye, drug), size (200–2000 nm), coating (targeting agent, antibody), and surface charge (40–30 mV) [60]. Similar to the use of SPIO contrast agents, using appropriate labeling protocols, no significant adverse effects have been observed following the internalization of fluorine tracer agents in terms of DC survival, maturation, antigen presentation, and/or surface marker expression in vitro and in vivo [61, 62]. When indocyanine green was entrapped in PFC emulsions, which prevented photobleaching of the dye, as little as 1 × 105 labeled DCs could also be tracked in vivo with photoacoustic imaging [63], as well as ultrasound imaging [64].

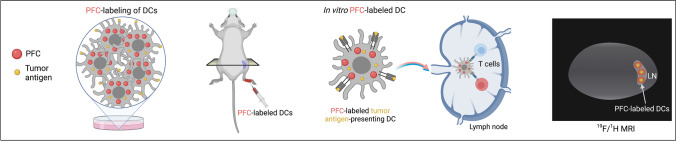

Fig. 4.

Direct pre-labeling or ex vivo labeling of DCs with fluorinated emulsions for 19F MRI. DCs are first pulsed with tumor antigen (to prevent label dilution) and then labeled with PFC for 24-h incubation. Shown is a pre-clinical example where DCs are injected into the footpad and accumulate in regional LNs (i.e., popliteal LNs) where the tumor vaccination takes place. DCs homing to LNs show up as “hot spots” on 19F MRI.

The first clinical 19F MRI cell tracking was published in 2014 [14], and as in the case of SPIO-labeled cells for 1H MRI, it was again with pre-labeled DCs (Fig. 5). Autologous DCs were labeled with the commercial PFC formulation CS-1000, and 10 million cells were injected intradermally in 3 colorectal carcinoma patients. The cell injection site was clearly visualized, with a 50% loss of signal after 24 h due to either cell death followed by PFC clearance or cell migration away from the injection site towards the draining LNs. However, no cells were detected in the LNs within the same field of view. The 19F MRI signal at the injection site for two patients receiving a lower dose of 1 × 106 cells could not be observed. As mentioned earlier above, it has been estimated that less than 5% of intradermally administered mature DCs reach the draining LNs [10], which would be 5 × 105 cells in this specific study. If one assumes that the cell dose disperses within a comparable tissue volume as the higher dose patients, then the current detection limit threshold for clinical scanning at 3 T is between 1 × 106 and 1 × 107 labeled cells. However, future studies could enhance the sensitivity of detection using one or more of the following approaches: (1) using optimized imaging pulse sequences and parameters such as compressed sensing [65] and ultrashort echo-times [66]; (2) incorporation of paramagnetic metals to shorten 19F relaxation times [67, 68]; (3) improved hardware/coils; and [4] imaging at higher clinical field strength (7 T).

Fig. 5.

Clinical 19F MRI cell tracking of DCs using direct/ex vivo pre-labeling. Monocytes are obtained by leukopheresis from stage IV colorectal adenocarcinoma patients. DCs are labeled with PFC for 24 h in culture. A total of 1.0 × 107 DCs are then injected intradermally into the thigh muscle (quadriceps), and their biodistribution is monitored in vivo by 3 T 19F/1H MRI (F, femur; RF, rectus femoris; LN, inguinal lymph node). The bottom far right panel with actual data is reproduced, with permission, from Ref. [14].

Indirect Labeling or In Vivo/In Situ Labeling of DCs for 1H MRI: Magnetovaccination

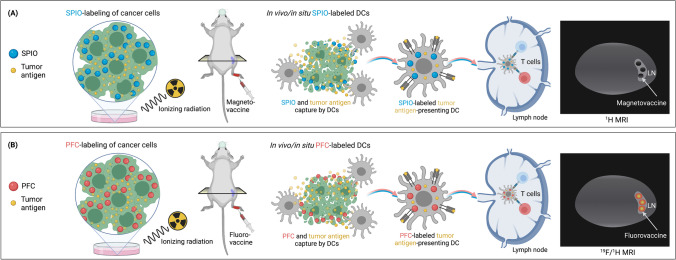

A different approach for cancer vaccination is not to label DCs but instead irradiated tumor cells which die upon injection, followed by in vivo/in situ uptake of tumor cells and their antigen content. Tumor cells engineered to secrete murine granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor, known as the GVAX vaccine, have shown to induce potent, specific, and long-lasting anti-tumor immunity [69]. By pre-labeling GVAX with SPIO, DCs can be indirectly labeled in situ known as a process called magnetovaccination [70, 71] (Fig. 6A). A similar approach can be imagined for using PFC emulsions which would then be termed fluorovaccination (Fig. 6B), but this has not yet been attempted and may be more challenging due to the lower sensitivity of 19F MRI. Importantly, only DCs that captured tumor antigen are simultaneously labeled with SPIO, and hence, one can now monitor trafficking of DC antigen capture and trafficking to LNs. This approach mimics the natural biological process of DC tumor cell interactions, is more specific than labeling DCs ex vivo, and can visualize the subset of true antigen-presenting DCs. However, using ex vivo pre-direct labeling, it has been suggested that it is possible to establish whether an antigen-specific response is initiated by assessing migration of successive rounds of antigen-loaded dendritic cells; in the case of a successfully primed cytotoxic response, the bulk of antigen-loaded cells are eradicated on-route to the LN, whereas cells without antigen can reach the LN unimpaired [72].

Fig. 6.

Indirect labeling or in vivo/in situ labeling of DCs for 1H and 19F MRI: magnetovaccination and fluorovaccination. Instead of direct pre-labeling of DCs, tumor cells are pre-labeled ex vivo with A SPIO or B PFC and irradiated. Following injection, these labeled tumor cells die, and their cell fragments are phagocytosed by DCs in vivo/in situ. When they capture tumor antigen, they will simultaneously take up the SPIO/PFC label. Hence, only antigen-primed DCs can be visualized with their MR signal correlating directly to the degree of antigen presentation in LNs. While proof-of-principle of A magnetovaccination has been demonstrated [70, 71], the feasibility of B fluorovaccination has yet to be shown.

By using artificial intelligence (AI)-mediated analysis of hypointense pixel histograms, it was shown that the number of hypointense pixels in the LN, representing labeled DCs, corresponded to the number of magnetically labeled DCs recovered with magnetic cell separation [70] as well as with the number of SPIO-Evergreen fluorescent dye-labeled cells using flow cytometry [71]. Recovered cells were fully functional and able to present antigen when put back in culture with antigen-specific T cells.

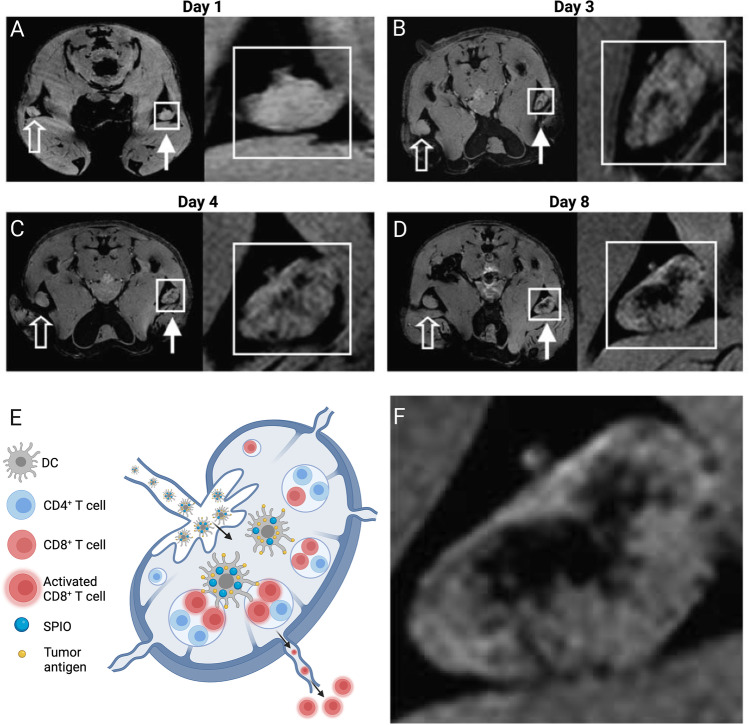

The high resolution of high-field (9.4 T) 1H MRI enabled single pixel counts representing single-labeled DCs, with a tendency of antigen-presenting DCs to migrate over time from the LN cortex to the medulla, where T cell activation takes place in the follicles (Fig. 7). While fluorovaccination does not have single-cell resolution to enable pixel count histograms, when properly calibrated with labeled reference samples, the total 19F signal could still be used to quantify antigen-presenting DCs.

Fig. 7.

Magnetovaccination enables high resolution of single antigen-presenting cells migrating from the popliteal LN cortex to the LN medulla over time. A–D 1H MR images 1, 3, 4, and 8 days post-magnetovaccine injection in the footpad. Open arrows indicate draining LNs of the lateral foot pad site injected unlabeled vaccine; closed arrows indicate the other foot pad site of injected SPIO-labeled (magneto)vaccine. E Schematic drawing of F magnified 1H MR image at day 8 post-magnetovaccination shows accumulation of magnetovaccinated DCs in the medullar area, where the antigen presentation to T cells takes place in the follicles. Panels (A–D, F) are reproduced, with permission, from Ref. [70].

The magnetovaccination strategy has been used to study the timing and dosing of immunoadjuvants. One of the widely used clinically immunoadjuvant is the Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) agonist vaccine adjuvant glucopyranosyl lipid A (GLA), a synthetic glycolipid that stimulates APCs via TLR4, induces a type I immune response, and increases immunogenicity to vaccine antigens [73, 74]. Clinically, it is currently given together with the DC vaccine. It was shown that injection of GLA 24 h prior or simultaneously with the injection of DCs paradoxically decreased the amount of SPIO-labeled DCs homing to LNs, but this could be rescued by injecting GLA 24 h after the injection of DCs [71]. It was postulated that the immunoadjuvant has such a potency that it induces DC LN homing before these cells have sufficient time to capture the tumor antigen and SPIO in situ. Interestingly, the reduced homing of DCs to LNs was accompanied by a massive proliferation of vaccine-primed, antigen-specific luciferase (Luc)-expressing transgenic T cells in the spleen, as visualized using bioluminescent imaging (BLI). This was accompanied by an enhanced tumor therapeutic effect of the vaccine [71]. Needless to say, the clinical implications of these findings are significant.

Future Clinical Outlook and Perspectives

We need non-invasive imaging methods capable to (a) verify that tumor antigen-primed DCs are administered correctly at the targeted injection site; (b) to assure that tumor antigen-primed DCs home in sufficient numbers to the LN follicles where recipient T cells reside and are waiting to be activated; and (c) that homing, tumor antigen-primed DCs indeed carry the required amount of antigen needed for sufficient T cell activation and treatment efficacy. Ideally, the quantification of LN signal changes will serve as an early predictor for the efficacy of cancer vaccination and anti-tumor treatment response. While MRI has become the primary clinical imaging modality for tracking DCs, new emerging techniques such as magnetic particle imaging (MPI) may be combined with MRI to perform tracer-labeled DC quantification and hot spot imaging interpretation [75, 76], similar as can be currently done with 19F MRI. The number of clinical MRI DC tracking studies has been few, which may have its roots in the paucity of available GMP-grade labeling agents, their cost of production and testing, and the need for cumbersome IND approval for their off-label use (unlike the use of radionuclides, where often the microdosing tracer principle applies). Chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) MRI tracking of unlabeled cells would avoid these hurdles but has so far only be applied for mesenchymal stem cells [77]. Finally, it should be noted that there have been recent efforts to develop artificial APCs (aAPCs) based on SPIO nanoparticles [78, 79], where 1H MRI aAPC tracking could be further used to add value to their evaluation in vivo.

Funding

J. W. M. B. is funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health (P41 EB024495, R01 DK106972, R01 EB023647, R01 EB030376, R01 CA257557, UH2 EB028904, and S10 OD026740), the Maryland Stem Cell Research Foundation (MSCRFD-5416), Philips Medical Systems Inc., and NovaDip Biosciences. The figures in this manuscript were created with BioRender software (https://biorender.com).

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

J. W. M. B. is a paid consultant to NovaDip Biosciences SA, NanomediGene LLC, and SuperBranche. These arrangements have been reviewed and approved by the Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies. A. S. -Z has nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Steinman RM. Lasker Basic Medical Research Award. Dendritic cells: versatile controllers of the immune system. Nat Med. 2007;13(10):1155–9. doi: 10.1038/nm1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palucka AK, Ueno H, Fay JW, Banchereau J. Taming cancer by inducing immunity via dendritic cells. Immunol Rev. 2007;220(1):129–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steinman RM, Cohn ZA (1973) Identification of a novel cell type in peripheral lymphoid organs of mice I. Morphology, quantitation, tissue distribution. J Exp Med 137(5):1142–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Tacken PJ, de Vries IJM, Torensma R, Figdor CG. Dendritic-cell immunotherapy: from ex vivo loading to in vivo targeting. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7(10):790–802. doi: 10.1038/nri2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saxena M, van der Burg SH, Melief CJM, Bhardwaj N. Therapeutic cancer vaccines. Nat Rev Cancer. 2021;21(6):360–378. doi: 10.1038/s41568-021-00346-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mukherji B, Chakraborty NG, Yamasaki S, Okino T, Yamase H, Sporn JR et al (1995) Induction of antigen-specific cytolytic T cells in situ in human melanoma by immunization with synthetic peptide-pulsed autologous antigen presenting cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92(17):8078–8082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Kantoff PW, Higano CS, Shore ND, Berger ER, Small EJ, Penson DF, et al. Sipuleucel-T immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(5):411–422. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fox JL. Uncertainty surrounds cancer vaccine review at FDA. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25(8):827–828. doi: 10.1038/nbt0807-827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Figdor CG, de Vries IJ, Lesterhuis WJ, Melief CJ. Dendritic cell immunotherapy: mapping the way. Nat Med. 2004;10(5):475–480. doi: 10.1038/nm1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Vries IJ, Krooshoop DJ, Scharenborg NM, Lesterhuis WJ, Diepstra JH, Van Muijen GN, et al. Effective migration of antigen-pulsed dendritic cells to lymph nodes in melanoma patients is determined by their maturation state. Cancer Res. 2003;63(1):12–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dubensky TW, Jr, Reed SG. Adjuvants for cancer vaccines. Semin Immunol. 2010;22(3):155–161. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bulte JWM, Daldrup-Link HE. Clinical tracking of cell transfer and cell transplantation: trials and tribulations. Radiology. 2018;289(3):604–615. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2018180449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Vries IJ, Lesterhuis WJ, Barentsz JO, Verdijk P, van Krieken JH, Boerman OC, et al. Magnetic resonance tracking of dendritic cells in melanoma patients for monitoring of cellular therapy. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23(11):1407–1413. doi: 10.1038/nbt1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahrens ET, Helfer BM, O'Hanlon CF, Schirda C. Clinical cell therapy imaging using a perfluorocarbon tracer and fluorine-19 MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2014;72(6):1696–1701. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baumjohann D, Hess A, Budinsky L, Brune K, Schuler G, Lutz MB. In vivo magnetic resonance imaging of dendritic cell migration into the draining lymph nodes of mice. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36(9):2544–2555. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruiz-Cabello J, Walczak P, Kedziorek DA, Chacko VP, Schmieder AH, Wickline SA, et al. In vivo "hot spot" MR imaging of neural stem cells using fluorinated nanoparticles. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60(6):1506–1511. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bulte JW, Hoekstra Y, Kamman RL, Magin RL, Webb AG, Briggs RW, et al. Specific MR imaging of human lymphocytes by monoclonal antibody-guided dextran-magnetite particles. Magn Reson Med. 1992;25(1):148–157. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910250115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahrens E, Feili-Hariri M, Xu H, Genove G, Morel P. Receptor-mediated endocytosis of iron-oxide particles provides efficient labeling of dendritic cells for in vivo MR imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2003;49(6):1006–1013. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shapiro EM, Medford-Davis LN, Fahmy TM, Dunbar CE, Koretsky AP. Antibody-mediated cell labeling of peripheral T cells with micron-sized iron oxide particles (MPIOs) allows single cell detection by MRI. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2007;2(3):147–153. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reichardt W, Dürr C, von Elverfeldt D, Jüttner E, Gerlach UV, Yamada M, et al. Impact of mammalian target of rapamycin inhibition on lymphoid homing and tolerogenic function of nanoparticle-labeled dendritic cells following allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Immunol. 2008;181(7):4770–4779. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bulte JW, Ma LD, Magin RL, Kamman RL, Hulstaert CE, Go KG, et al. Selective MR imaging of labeled human peripheral blood mononuclear cells by liposome mediated incorporation of dextran-magnetite particles. Magn Reson Med. 1993;29(1):32–37. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910290108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grippin AJ, Wummer B, Wildes T, Dyson K, Trivedi V, Yang C, et al. Dendritic cell-activating magnetic nanoparticles enable early prediction of antitumor response with magnetic resonance imaging. ACS Nano. 2019;13(12):13884–13898. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.9b05037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim YT, Noh YW, Han JH, Cai QY, Yoon KH, Chung BH. Biocompatible polymer-nanoparticle-based bimodal imaging contrast agents for the labeling and tracking of dendritic cells. Small. 2008;4(10):1640–1645. doi: 10.1002/smll.200800582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cho N-H, Cheong T-C, Min JH, Wu JH, Lee SJ, Kim D, et al. A multifunctional core–shell nanoparticle for dendritic cell-based cancer immunotherapy. Nat Nanotechnol. 2011;6(10):675–682. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2011.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schreiber HA, Prechl J, Jiang H, Zozulya A, Fabry Z, Denes F, et al. Using carbon magnetic nanoparticles to target, track, and manipulate dendritic cells. J Immunol Methods. 2010;356(1–2):47–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Temmerman M-L, Soenen SJ, Symens N, Lucas B, Vandenbroucke RE, Libert C, et al. Magnetic layer-by-layer coated particles for efficient MRI of dendritic cells and mesenchymal stem cells. Nanomedicine. 2014;9(9):1363–1376. doi: 10.2217/nnm.13.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Toki S, Omary RA, Wilson K, Gore JC, Peebles RS, Jr, Pham WA. comprehensive analysis of transfection assisted delivery of iron oxide nanoparticles to dendritic cells. Nanomed Nanotechnol Biol Med. 2013;9(8):1235–44. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2013.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu Y, Wu C, Zhu W, Xia C, Wang D, Zhang H, et al. Superparamagnetic MRI probes for in vivo tracking of dendritic cell migration with a clinical 3 T scanner. Biomaterials. 2015;58:63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mackay PS, Kremers GJ, Kobukai S, Cobb JG, Kuley A, Rosenthal SJ et al (2011) Multimodal imaging of dendritic cells using a novel hybrid magneto-optical nanoprobe. Nanomed: Nanotechnol Biol Med 7(4):489–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Noh Y-W, Jang Y-S, Ahn K-J, Lim YT, Chung BH. Simultaneous in vivo tracking of dendritic cells and priming of an antigen-specific immune response. Biomaterials. 2011;32(26):6254–6263. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dewitte H, Geers B, Liang S, Himmelreich U, Demeester J, De Smedt SC, et al. Design and evaluation of theranostic perfluorocarbon particles for simultaneous antigen-loading and 19F-MRI tracking of dendritic cells. J Control Release. 2013;169(1–2):141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang C, Xu Z, Di H, Zeng E, Jiang Y, Liu D (2020) Gadolinium-doped Au@prussian blue nanoparticles as MR/SERS bimodal agents for dendritic cell activating and tracking. Theranostics 10(13):6061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Kim HS, Woo J, Lee JH, Joo HJ, Choi Y, Kim H et al (2015) In vivo tracking of dendritic cell using MRI reporter gene ferritin. PLoS One 10(5):e0125291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Vymazal J, Zak O, Bulte JW, Aisen P, Brooks RA. T1 and T2 of ferritin solutions: effect of loading factor. Magn Reson Med. 1996;36(1):61–65. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910360111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Briley-Saebo KC, Leboeuf M, Dickson S, Mani V, Fayad ZA, Karolina Palucka A, et al. Longitudinal tracking of human dendritic cells in murine models using magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2010;64(5):1510–1519. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Verdijk P, Scheenen TW, Lesterhuis WJ, Gambarota G, Veltien AA, Walczak P, et al. Sensitivity of magnetic resonance imaging of dendritic cells for in vivo tracking of cellular cancer vaccines. Int J Cancer. 2007;120(5):978–984. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Chickera S, Willert C, Mallet C, Foley R, Foster P, Dekaban GA. Cellular MRI as a suitable, sensitive non-invasive modality for correlating in vivo migratory efficiencies of different dendritic cell populations with subsequent immunological outcomes. Int Immunol. 2012;24(1):29–41. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxr095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dekaban GA, Snir J, Shrum B, de Chickera S, Willert C, Merrill M, et al. Semiquantitation of mouse dendritic cell migration in vivo using cellular MRI. J Immunother. 2009;32(3):240–251. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e318197b2a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tavare R, Sagoo P, Varama G, Tanriver Y, Warely A, Diebold SS et al (2011) Monitoring of in vivo function of superparamagnetic iron oxide labelled murine dendritic cells during anti tumour vaccination. PloS One 6(5):e19662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Martelli C, Borelli M, Ottobrini L, Rainone V, Degrassi A, Russo M, et al. In vivo imaging of lymph node migration of MNP-and 111 In-labeled dendritic cells in a transgenic mouse model of breast cancer (MMTV-Ras) Mol Imag Biol. 2012;14(2):183–196. doi: 10.1007/s11307-011-0496-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang X, de Chickera SN, Willert C, Economopoulos V, Noad J, Rohani R, et al. Cellular magnetic resonance imaging of monocyte-derived dendritic cell migration from healthy donors and cancer patients as assessed in a scid mouse model. Cytotherapy. 2011;13(10):1234–1248. doi: 10.3109/14653249.2011.605349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crisci E, Fraile L, Novellas R, Espada Y, Cabezón R, Martínez J, et al. In vivo tracking and immunological properties of pulsed porcine monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Mol Immunol. 2015;63(2):343–354. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rohani R, de Chickera SN, Willert C, Chen Y, Dekaban GA, Foster PJ (2011) In vivo cellular MRI of dendritic cell migration using micrometer-sized iron oxide (MPIO) particles. Mol Imag Biol 13(4):679–694 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.de Chickera SN, Snir J, Willert C, Rohani R, Foley R, Foster PJ, et al. Labelling dendritic cells with SPIO has implications for their subsequent in vivo migration as assessed with cellular MRI. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2011;6(4):314–327. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bonetto F, Srinivas M, Weigelin B, Cruz L, Heerschap A, Friedl P, et al. A large-scale 19F MRI-based cell migration assay to optimize cell therapy. NMR Biomed. 2012;25(9):1095–1103. doi: 10.1002/nbm.2774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang W, Zhang S, Xu W, Zhang M, Zhou Q, Chen W. The function and magnetic resonance imaging of immature dendritic cells under ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide (USPIO)-labeling. Biotech Lett. 2017;39(7):1079–1089. doi: 10.1007/s10529-017-2332-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kraitchman DL, Heldman AW, Atalar E, Amado LC, Martin BJ, Pittenger MF, et al. In vivo magnetic resonance imaging of mesenchymal stem cells in myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2003;107(18):2290–2293. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000070931.62772.4E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Karmarkar PV, Kraitchman DL, Izbudak I, Hofmann LV, Amado LC, Fritzges D, et al. MR-trackable intramyocardial injection catheter. Magn Reson Med. 2004;51(6):1163–1172. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barnett BP, Arepally A, Karmarkar PV, Qian D, Gilson WD, Walczak P, et al. Magnetic resonance-guided, real-time targeted delivery and imaging of magnetocapsules immunoprotecting pancreatic islet cells. Nat Med. 2007;13(8):986–991. doi: 10.1038/nm1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bulte JW. Science to practice: can decreased lymph node MR imaging signal intensity be used as a biomarker for the efficacy of cancer vaccination? Radiology. 2015;274(1):1–3. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14142331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang Z, Li W, Procissi D, Li K, Sheu AY, Gordon AC, et al. Antigen-loaded dendritic cell migration: MR imaging in a pancreatic carcinoma model. Radiology. 2015;274(1):192–200. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14132172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ahrens ET, Flores R, Xu H, Morel PA. In vivo imaging platform for tracking immunotherapeutic cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23(8):983–987. doi: 10.1038/nbt1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ruiz-Cabello J, Barnett BP, Bottomley PA, Bulte JW. Fluorine (19F) MRS and MRI in biomedicine. NMR Biomed. 2011;24(2):114–129. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bulte JW. Hot spot MRI emerges from the background. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23(8):945–946. doi: 10.1038/nbt0805-945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Srinivas M, Turner MS, Janjic JM, Morel PA, Laidlaw DH, Ahrens ET. In vivo cytometry of antigen-specific t cells using 19F MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2009;62(3):747–753. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shin SH, Kadayakkara DK, Bulte JW. In vivo (19)F MR imaging cell tracking of inflammatory macrophages and site-specific development of colitis-associated dysplasia. Radiology. 2017;282(1):194–201. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016152387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bonetto F, Srinivas M, Heerschap A, Mailliard R, Ahrens ET, Figdor CG, et al. A novel 19F agent for detection and quantification of human dendritic cells using magnetic resonance imaging. Int J Cancer. 2011;129(2):365–373. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rose LC, Kadayakkara DK, Wang G, Bar-Shir A, Helfer BM, O'Hanlon CF, et al. Fluorine-19 labeling of stromal vascular fraction cells for clinical imaging applications. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2015;4(12):1472–1481. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2015-0113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Waiczies H, Lepore S, Janitzek N, Hagen U, Seifert F, Ittermann B et al (2011) Perfluorocarbon particle size influences magnetic resonance signal and immunological properties of dendritic cells. PloS One. 6(7):e21981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Srinivas M, Cruz LJ, Bonetto F, Heerschap A, Figdor CG, De Vries IJM. Customizable, multi-functional fluorocarbon nanoparticles for quantitative in vivo imaging using 19F MRI and optical imaging. Biomaterials. 2010;31(27):7070–7077. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.05.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fink C, Smith M, Gaudet JM, Makela A, Foster PJ, Dekaban GA. Fluorine-19 cellular mri detection of in vivo dendritic cell migration and subsequent induction of tumor antigen-specific immunotherapeutic response. Mol Imaging Biol. 2020;22(3):549–561. doi: 10.1007/s11307-019-01393-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Helfer BM, Balducci A, Nelson AD, Janjic JM, Gil RR, Kalinski P, et al. Functional assessment of human dendritic cells labeled for in vivo 19F magnetic resonance imaging cell tracking. Cytotherapy. 2010;12(2):238–250. doi: 10.3109/14653240903446902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Swider E, Daoudi K, Staal AH, Koshkina O, Van Riessen NK, van Dinther E, et al. Clinically-applicable perfluorocarbon-loaded nanoparticles for in vivo photoacoustic, 19F magnetic resonance and fluorescent imaging. Nanotheranostics. 2018;2(3):258. doi: 10.7150/ntno.26208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Koshkina O, Lajoinie G, Bombelli FB, Swider E, Cruz LJ, White PB, et al. multicore liquid perfluorocarbon-loaded multimodal nanoparticles for stable ultrasound and (19)F MRI applied to in vivo cell tracking. Adv Funct Mater 2019;29(19). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.Zhong J, Mills PH, Hitchens TK, Ahrens ET. Accelerated fluorine-19 MRI cell tracking using compressed sensing. Magn Reson Med. 2013;69(6):1683–1690. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Goette MJ, Keupp J, Rahmer J, Lanza GM, Wickline SA, Caruthers SD. Balanced UTE-SSFP for 19F MR imaging of complex spectra. Magn Reson Med. 2015;74(2):537–543. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kislukhin AA, Xu H, Adams SR, Narsinh KH, Tsien RY, Ahrens ET. Paramagnetic fluorinated nanoemulsions for sensitive cellular fluorine-19 magnetic resonance imaging. Nat Mater. 2016;15(6):662–668. doi: 10.1038/nmat4585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Neubauer AM, Myerson J, Caruthers SD, Hockett FD, Winter PM, Chen J, et al. Gadolinium-modulated 19F signals from perfluorocarbon nanoparticles as a new strategy for molecular imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60(5):1066–1072. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dranoff G, Jaffee E, Lazenby A, Golumbek P, Levitsky H, Brose K, et al. Vaccination with irradiated tumor cells engineered to secrete murine granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor stimulates potent, specific, and long-lasting anti-tumor immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90(8):3539–3543. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Long CM, van Laarhoven HW, Bulte JW, Levitsky HI. Magnetovaccination as a novel method to assess and quantify dendritic cell tumor antigen capture and delivery to lymph nodes. Cancer Res. 2009;69(7):3180–3187. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kadayakkara DK, Korrer MJ, Bulte JW, Levitsky HI. Paradoxical decrease in the capture and lymph node delivery of cancer vaccine antigen induced by a TLR4 agonist as visualized by dual-mode imaging. Cancer Res. 2015;75(1):51–61. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ferguson PM, Slocombe A, Tilley RD, Hermans IF (2013) Using magnetic resonance imaging to evaluate dendritic cell-based vaccination. PLoS One 8(5):e65318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 73.Baldwin SL, Shaverdian N, Goto Y, Duthie MS, Raman VS, Evers T, et al. Enhanced humoral and Type 1 cellular immune responses with Fluzone adjuvanted with a synthetic TLR4 agonist formulated in an emulsion. Vaccine. 2009;27(43):5956–5963. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.07.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Coler RN, Bertholet S, Moutaftsi M, Guderian JA, Windish HP, Baldwin SL et al (2011) Development and characterization of synthetic glucopyranosyl lipid adjuvant system as a vaccine adjuvant. PLoS One 6(1):e16333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 75.Bulte JW, Walczak P, Janowski M, Krishnan KM, Arami H, Halkola A, et al. Quantitative "hot spot" imaging of transplanted stem cells using superparamagnetic tracers and magnetic particle imaging (MPI) Tomography. 2015;1(2):91–97. doi: 10.18383/j.tom.2015.00172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bulte JWM. Superparamagnetic iron oxides as MPI tracers: a primer and review of early applications. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2019;138:293–301. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2018.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yuan Y, Wang C, Kuddannaya S, Zhang J, Arifin DR, Han Z, et al. In vivo tracking of unlabeled mesenchymal stem cells by mannose-weighted chemical exchange saturation transfer MRI. Nat Biomed Eng. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 78.Perica K, De León MA, Durai M, Chiu YL, Bieler JG, Sibener L, et al. Nanoscale artificial antigen presenting cells for T cell immunotherapy. Nanomedicine. 2014;10(1):119–129. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2013.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Perica K, Bieler JG, Schütz C, Varela JC, Douglass J, Skora A, et al. Enrichment and expansion with nanoscale artificial antigen presenting cells for adoptive immunotherapy. ACS Nano. 2015;9(7):6861–6871. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b02829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]