Abstract

Vaginal isolates of Candida albicans from human immunodeficiency virus-positive (HIV+) and HIV− women with or without candidal vaginitis were examined for secretory aspartyl proteinase (Sap) production in vitro and in vivo and for the possible correlation of Sap production with pathology and antimycotic susceptibility in vitro. HIV+ women with candidal vaginitis were infected by strains of C. albicans showing significantly higher levels of Sap, a virulence enzyme, than strains isolated from HIV+, C. albicans carrier subjects and HIV− subjects with vaginitis. The greater production of Sap in vitro was paralleled by greater amounts of Sap in the vaginal fluids of infected subjects. In an estrogen-dependent, rat vaginitis model, a strain of C. albicans producing a high level of Sap that was isolated from an HIV+ woman with vaginitis was more pathogenic than a strain of C. albicans that was isolated primarily from an HIV−, Candida carrier. In the same model, pepstatin A, a strong Sap inhibitor, exerted a strong curative effect on experimental vaginitis. No correlation was found between Sap production and antimycotic susceptibility, as most of the isolates were fully susceptible to fluconazole, itraconazole, and other antimycotics, regardless of their source (subjects infected with strains producing high or low levels of Sap, subjects with vaginitis or carrier subjects, or subjects with or without HIV). Thus, high Sap production is associated with virulence of C. albicans but not with fungal resistance to fluconazole in HIV-infected subjects, and Sap is a potentially new therapeutic target in candidal vaginitis.

Mucosal candidiases are common opportunistic diseases in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patients (20, 25), but their immunopathogenesis is poorly understood. The transition of Candida albicans, the most common agent of mucosal candidiasis (29), from asymptomatic carriage to invasion of mucosal tissues is associated with lowering of the number of CD4+ T lymphocytes, perturbation in the T-helper-type response, and lack of T-cell recognition of immunodominant Candida antigens (31, 35). However, in HIV+ subjects there might be a selection of more virulent C. albicans strains and increasing resistance to antimycotics (6–8, 26, 33, 34, 37), thus contributing to the outbreak of the disease, as well as its easily relapsing nature and treatment failures.

Since the ability to secrete one or more members of the secretory aspartyl proteinase (Sap) family is a Candida virulence trait (11, 21, 32), we have previously assessed Sap secretion by Candida isolates from the oral cavities of subjects at different stages of HIV infection. Strains of C. albicans with particularly high Sap production were much more frequently isolated from the oral cavities of HIV+ than HIV− subjects (13, 15, 30). We also showed that HIV− candidal vaginitis patients harbored in their vaginas C. albicans strains with increased Sap production (1, 10, 12).

In the light of this information, and also because Sap is a potential target of new anticandidal agents, we have now compared, in vitro and in vivo, levels of Sap production in HIV+ and HIV− subjects with or without vaginitis. In addition, we assessed with a rat vaginitis model the pathogenicity of a human vaginal isolate of C. albicans that produces a high level of Sap and the response of this infection to therapeutic treatment with pepstatin A, a Sap inhibitor (21). Finally, because of the reports on the increased resistance to fluconazole of C. albicans strains isolated from HIV+ subjects (2–5, 18, 23), we also evaluated the susceptibility to triazole drugs of Candida isolates by an improved, internationally tested method of antimycotic susceptibility determination (2a, 28).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects.

Eighty-six HIV+, nonpregnant, nondiabetic women attending as outpatients the Clinic of Obstetrics and Gynecology of the “Università La Sapienza” (Rome, Italy) during 1996 were consecutively examined for the presence of vaginal candidiasis. Each case was diagnosed on the basis of fungus isolation, the presence of the physical signs of a typical vaginal discharge (clumpy, cottage-cheese-like appearance), and intense vulvovaginal pruritus, with or without vulvar erythema and dyspareunia (10). HIV+ women with no symptoms or signs of vaginitis but with Candida isolation from the vagina were considered Candida carriers. The criteria for HIV infection and staging were those routinely adopted (2, 13, 15). The CD4+ T-cell means (± standard errors [SE]) were 326 (±52) and 443 (±106) for subjects with vaginitis and asymptomatic subjects, respectively.

The controls were HIV− outpatients, matched for age to the HIV+ women, who were Candida carriers or affected by symptomatic candidal vaginitis. All vaginitis subjects were not under antimycotic therapy or prophylaxis at the moment of fungus isolation.

Yeast isolation and identification.

Vaginal samples were taken with cotton-tipped swabs and kept in sterile physiological saline, before being transferred to the laboratory, where they were streaked on plates of Sabouraud dextrose agar (BBL, Baltimore, Md.) with added chloramphenicol (50 μg/ml) and on plates of Mycosel agar before immersion into enrichment broth. All cultures were incubated for 48 to 72 h at 30°C. All isolates were identified on the basis of their morphologies and profiles with the API 20C system (Biomerieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France). Serological analysis done according to the method of Tsuchiya et al. (36) was also performed as an aid to the final identification of C. albicans.

Vaginal fluid was taken by washing the vaginal cavity with 2.0 ml of sterile saline solution, which was slowly injected into the posterior fornix and then aspirated. The retrieved fluid was immediately stored at −20°C, transported to the laboratory within 2 h, and kept frozen until the Sap assay (see below).

Sap detection in vitro and in vaginal fluids.

All isolates were tested for their ability to grow and produce a clear zone of hydrolysis in bovine serum albumin (BSA) agar (yeast carbon base [Difco], 1.17%; yeast extract [BBL], 0.01%; BSA [BDH], 0.2%), as a measure of Sap activity. The medium was adjusted to pH 5, sterilized by filtration, and added to a stock solution of autoclaved (2%) agar. Sap activity was scored as follows: − when no visible clarification of the agar around the colony was present, 1+ when a visible clear zone (1 to 2 mm in diameter) was observed, and 2+ when agar clarification largely exceeded (by 3 to 5 mm) the margin of colony (see also references 12 and 13).

Sap antigen secretion in BSA broth was also assayed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (12, 13). Briefly, the isolates were cultured in YEPD broth (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% dextrose), the cultures were centrifuged, and the cellular pellet (106 cells in 25 ml of YEPD broth plus 0.2% BSA) was washed and incubated at 30°C with slight agitation. After 40 h of incubation, the samples were centrifuged at 3,400 × g for 10 min and the supernatants were treated with 0.5 ml of 50% trichloroacetic acid, incubated for 30 min in ice, and centrifuged at 3,400 × g for 10 min. The pellets were washed twice with 95% ethanol, dissolved in 1% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate, diluted in 0.2 M sodium carbonate buffer (pH 9.6), and applied to MicroTest plates. Purified rabbit anti-Sap serum (12) was added at a 1:100 dilution and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. The second antibody was phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG; 1:1,000 dilution; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.). The reaction was detected with phosphatase substrate nitrophenol phosphate (Sigma). The Sap amount was calculated from a standard curve (1 to 110 ng) determined with a highly purified Sap preparation (12) as the coating antigen. The optical densities of the plates were read with a Titer K Multiscan (Labsystem, Helsinki, Finland) at 405 nm and blanked against air. The specificity of the ELISA for proteinase detection was confirmed by Western blotting (12).

ELISAs were also used for detection of Sap in the vaginal fluids of vaginitis patients and control women. The vaginal washes were thawed and centrifuged at 6,500 × g for 10 min; supernatants were treated with 0.5 ml of 50% trichloroacetic acid, incubated for 30 min on ice, and centrifuged for 10 min. The resultant pellets were washed twice with 95% ethanol, dissolved in 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, boiled for 3 min, diluted in 0.2 M Na carbonate buffer (pH 9.6), and applied (70 μl) to the microtest plates. The ELISA procedure was the same as that described above.

Antimycotic susceptibility test.

A recently modified, improved method of antimycotic susceptibility assays in vitro, derived from the standardized method of the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (3, 28), was used throughout this study for the determination of Candida isolate susceptibility to fluconazole and itraconazole (2a). Susceptibility to other antimycotics was determined by the ATB fungus method (Biomerieux).

A stock solution of fluconazole (Pfizer Inc., New York, N.Y.) was prepared in sterile distilled water. A stock solution of itraconazole (Janssens Pharmaceutica, Beerse, Belgium) was prepared in polyethylene glycol 400 by heating the solution at 75°C for 45 min.

The yeast isolates were grown on Sabouraud dextrose agar for 48 h at 35°C. The inoculum suspension was prepared by picking five colonies of at least 1 mm in diameter and suspending them in 5 ml of sterile distilled water. The cell density of the suspension was adjusted spectrophotometrically to a final transmission of 85% at 530 nm. The working suspension was made with a 1:50 dilution in sterile distilled water followed by a 1:20 dilution in medium to obtain a 2× final suspension. Inoculum sizes were confirmed by the enumeration of CFU on Sabouraud dextrose agar. The medium for susceptibility testing was RPMI 1640 (American Biorganics, Inc., Niagara Falls, N.J.) to which l-glutamine had been added; this medium was buffered at pH 7.0 with 0.165 M morpholinepropanesulfonic acid. Testing was performed in sterile, flat-bottom 96-well microtiter plates. Drugs were prepared at 10 times the strength of the final concentration, and these mother solutions were diluted 1:5 with RPMI 1640 to obtain two times the final concentrations. Volumes of 50 μl of the 2× drug dilutions were dispensed into wells; two wells of each row served as growth and sterility controls. The microtiter plates were stored at −70°C until use. The day of the test, 50 μl of the yeast suspension was added to each well.

The microtiter plates were incubated at 35°C, and optical densities were read at 24 and 48 h with the aid of a reading mirror after the growth in each well was shaken and compared with that of the growth control (drug-free) well.

A numerical score which ranged from 0 to 4 was given to each well by using the following scale: 0, optically clear; 1, slightly hazy; 2, prominent decrease in turbidity; 3, slight reduction in turbidity; and 4, no reduction in turbidity. The MIC was defined as the lowest drug concentration at which a score of 2 (prominent decrease in turbidity) was observed (2a, 3, 28).

Experimental rat vaginitis and pepstatin A activity.

Oophorectomized, female Wistar rats (80 to 100 g; Charles River Breeding Laboratories, Calco, Italy) were injected subcutaneously with 0.5 mg of estradiol benzoate (Benzatrone; Samil, Rome, Italy). Six days after the first estradiol treatment, the animals were inoculated intravaginally with 107 yeast cells in 0.1 ml of each strain tested. The inoculum was dispensed into the vaginal cavity through a syringe equipped with a multipurpose calibrated tip (Combitip; Pool Bioanalysis International [PBI] Milan, Italy). The inoculated cells had been previously grown in YEDP at 28°C on a gyrotory shaker (200 rpm), harvested by centrifugation (3,000 × g), washed, counted in a hemacytometer, and suspended to the required number in 0.86% NaCl. The fungal cells in the vaginal cavity were counted by culturing 1-μl samples of vaginal fluid (taken from each animal with a calibrated plastic loop [Disponoic; PBI]) on Sabouraud dextrose agar containing chloramphenicol at 28°C for 72 h. One vaginal sample per rat was evaluated, and a rat was considered infected when at least 1 CFU was present, i.e., ≥103 CFU/ml of vaginal fluid were present.

Pepstatin A (P4265; Sigma) was dissolved in 95% ethanol, diluted 1:50 in sterile H2O, and administered intravaginally at a final concentration of 100 μg in 0.1 ml to a group of five estrogen-treated rats which had been infected (1 h before pepstatin administration) with the usual challenge dose of 107 C. albicans cells. Control rats received pepstatin diluent in phosphate-buffered saline only. Treatment with the drug or the diluent was daily for 7 days.

Statistics.

Differences were assessed for statistical significance by Student’s t test, the χ2 method, or Fisher’s exact method, as appropriate. P values of <0.05 (two-tailed) were considered significant.

RESULTS

Prevalence and distribution of Candida species isolated from HIV+ and HIV− women.

Candida spp. were isolated from the vaginas of 28 of 86 and 67 of 136 HIV+ and HIV− women, respectively. Table 1 shows the species distribution and their relative proportions in both vaginitis patients and carriers who were either HIV+ or HIV−. C. albicans accounted for almost all yeast isolations from HIV+ women who either had vaginitis or were carriers. In contrast, many other species of Candida and even Saccharomyces cerevisiae were isolated in remarkable proportions from HIV− women. In particular, the isolation of non-albicans species of Candida was significantly more frequent from HIV− carriers than from symptomatic women, and Candida glabrata was isolated twice as frequently as C. albicans from the vaginas of HIV− subjects. Overall, the prevalence of C. albicans in HIV+ women was 30.2% compared with the 19.8% prevalence in HIV− subjects, and 92.8% of the isolates from HIV+ women compared with 40.2% of the isolates from HIV− women were C. albicans (P < 0.01, χ2 method).

TABLE 1.

Prevalence of fungal species isolated from HIV+ and HIV− women with vaginitis or carrier women

| Subjects (n) | No. (%) of positive isolations | Species isolated (no. of isolates) | % of isolates that were C. albicans |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIV+ women with vaginitis (33) | 21 (63.6) | Candida albicans (20) | 95.2 |

| Candida guillermondii (1) | |||

| HIV+ carriers (53) | 7 (13.2) | Candida albicans (6) | 85.7 |

| Candida glabrata (1) | |||

| HIV− women with vaginitis (40) | 31 (77.5) | Candida albicans (19) | 61.3 |

| Candida parapsilosis (4) | |||

| Candida glabrata (3) | |||

| Candida kefyr (1) | |||

| Candida famata (1) | |||

| Candida tropicalis (1) | |||

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae (2) | |||

| HIV− carriers (96) | 36 (37.5) | Candida glabrata (17) | |

| Candida albicans (8) | 22.2 | ||

| Candida krusei (3) | |||

| Candida parapsilosis (1) | |||

| Candida lipolytica (1) | |||

| Candida famata (1) | |||

| Candida kefyr (1) | |||

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae (4) |

Sap secretion in vitro.

Sap secretion in vitro was assessed by measuring the proteolytic activity on BSA agar and by detecting Sap antigen in supernatants in BSA broth by ELISA (16, 20). Regardless of their source, all isolates of C. albicans expressed an enzymatically active Sap and secreted the relevant antigen in the culture medium (Table 2). However, the isolates from HIV+ women with symptomatic vaginitis produced the greatest amount of enzyme detectable by ELISA and all the tested strains exhibited the highest proteolytic potential on BSA agar. Compared to HIV− subjects with vaginitis, HIV+ women with vaginitis were infected by significantly more proteolytic strains and their Sap antigen production was significantly higher. In contrast, levels of Sap production by isolates from carriers were relatively low and not significantly different between HIV+ and HIV− subjects (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Sap secretion in vitro by C. albicans isolates from HIV+ and HIV− women with vaginitis or carrier women

| Subjects | No. of isolates | No. of isolates growing in BSA with Sap activity score:

|

Mean amt of Sap produced (ng/ml) ± SE as determined by ELISA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2+ | 1+ | |||

| HIV+ women with vaginitis | 20 | 10 | 10a | 201.55 ± 30.85b |

| HIV+ carriers | 6 | 1 | 5 | 47.43 ± 22.3 |

| HIV− women with vaginitis | 19 | 5 | 14 | 92.78 ± 14.7 |

| HIV− carriers | 8 | 2 | 6 | 38.11 ± 9 |

P < 0.05, compared to the Sap enzyme activities of strains from both HIV+ carriers and HIV− vaginitis patients (Fisher’s exact method).

P < 0.05, compared to levels of Sap antigen secretion by strains from both HIV+ carriers and HIV− subjects (both categories) (Fisher’s exact method).

Sap secretion in vivo.

The amounts of Sap in the vaginal fluids of subjects in the various categories were also measured. Sap was present in the vaginal fluids of all HIV+ and HIV− women from whose vaginas C. albicans was isolated, while it was under the detection limit (<2 ng/ml) in all other subjects, from whom either no yeast was isolated or a yeast species other than C. albicans was isolated. The enzyme was more abundant in the vaginal fluids of C. albicans-infected, HIV+ subjects with vaginitis than in those of HIV+ Candida carriers (235.5 ± 40.6 versus 73.2 ± 19.3 ng/ml; P < 0.05). Thus, the higher levels of Sap secretion in the culture supernatants of individual C. albicans isolates correlated with the increased levels of Sap detected in the vaginal fluids. There was also a trend for higher secretion of Sap in the vaginal fluids of HIV+ subjects with vaginitis than in those of their HIV− counterparts, although the difference did not reach statistical significance (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Amounts of Sap in vaginal fluids from HIV+ and HIV− women with vaginitis or carrier women

| Subjects (n) | Mean no. of CD4+ cells ± SE | Mean amt of vaginal Sapa (ng/ml) ± SE |

|---|---|---|

| HIV+ women with vaginitis (20) | 336 ± 52 | 235.5 ± 40.6* |

| HIV+ carriers (6) | 443 ± 106 | 73.2 ± 19.3 |

| HIV− women with vaginitis (19) | 164.3 ± 22.4** | |

| HIV− carriers (8) | 95.4 ± 14 |

As determined by ELISA of the vaginal fluids of subjects from whom Candida spp. were isolated. ∗ P < 0.05, compared to the Sap secretion in HIV+ and HIV− carriers (Student’s t test, two tailed). ∗∗ P < 0.05 compared to the Sap secretion in HIV− carriers (Student’s t test, two tailed).

Experimental rat vaginitis.

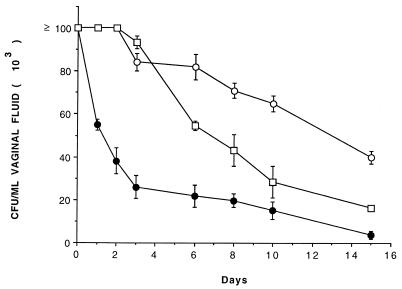

A vaginal isolate of C. albicans from an HIV+ subject (strain CO11) that produced a high level of Sap was assayed for its vaginopathic potential in a rat vaginitis model and compared with a strain that produced a significantly lower level of Sap in vitro, initially isolated from the vagina of an HIV− woman. In these experiments, the effect of pepstatin A, an inhibitor of Sap activity (21, 32), was also tested. As shown in Fig. 1, the high-level-Sap strain CO11 was cleared from the rat vagina significantly more slowly than the low-level-Sap strain. At 3 weeks postinfection, CO11 strain cells were still present in the vagina at a high burden whereas the control strain cells had been substantially eliminated. Pepstatin A greatly accelerated the clearance of the infection by the high-level-Sap strain CO11 (Fig. 1). This experiment was repeated, with totally comparable results.

FIG. 1.

Rat vaginal infection by a high-level-Sap strain (CO11; ○) isolated from the vagina of an HIV+ subject with vaginitis compared to the experimental infection caused by a low-level-Sap strain (SA-40) from a stock culture collection, initially isolated from the vagina of an HIV− subject (□). The ● symbols indicate results with the rats challenged with the CO11 strain and cured with pepstatin A, a Sap inhibitor. Each curve represents the means (± SE) of the Candida CFU of five rats per group. All rats were still infected on day 15, when the experiment was stopped. Usually, the rats clear the infection completely in 1 month (see references 20 and 21). Starting from day 3, there was a statistically significant difference in CFU counts between rats challenged with CO11 and the other two groups of animals. From day 6, the CFU difference between rats infected with CO11 and those infected with SA-40 strains was also significant.

Antimycotic susceptibilities of Candida spp. isolates from the vaginas of HIV+ and HIV− women.

Susceptibilities to antimycotic agents of Candida spp. isolates from the vaginas of HIV+ and HIV− women were also investigated. Nineteen and 18 of the 21 isolates from HIV+ subjects were susceptible to fluconazole and itraconazole, respectively. All isolates were also susceptible to amphothericin B. Four isolates were resistant to flucytosine, 11 were resistant to miconazole, 5 were resistant to econazole, and 4 were resistant to ketoconazole. Only 1 of the 22 isolates from HIV− women was resistant to fluconazole and itraconazole. All isolates were susceptible to amphothericin B. One isolate was resistant to flucytosine, four isolates were resistant to miconazole, and all isolates were susceptible to econazole and ketoconazole. There was no correlation between antimycotic resistance and Sap production (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Although the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy with HIV protease inhibitors has a significant impact upon the incidence of opportunistic infections in HIV+ patients, mucosal candidiases remain a serious problem in these subjects. There is also some debate about selection, in AIDS patients, of more virulent biotypes of C. albicans with increased potential for adaptation to the mucosal environment. As preliminarily shown elsewhere (13, 15), C. albicans, the most pathogenic species of Candida, is almost invariably isolated from patients with AIDS whereas many other less virulent Candida species may colonize the mucosae of healthy subjects (1, 27, 29). Moreover, mucosal candidiasis in AIDS patients is often difficult to treat and recurrences of the infections are frequent even after appropriate antifungal treatments (4, 8), suggesting an increased potential of C. albicans to attack the debilitated host. Thus, it is likely that C. albicans participates actively in determining the nature of mucosal infection with its own virulence factors.

In the above context, Sap production has been indicated as being one of the most relevant factors of Candida virulence in mucosal diseases (10, 11, 32). In particular, experiments with individual SAP gene knockout mutants demonstrated that the SAP2 gene, which codes for the Sap2 protein, abundantly produced in the vaginal cavity, is essential for the expression of the vaginopathic potential of C. albicans (17). We and others (15, 30) have previously shown that the strains of C. albicans isolated from the oral cavities of HIV+ subjects were strong Sap producers. The results of this paper demonstrate that C. albicans strains with particularly high levels of Sap secretion are significantly more likely to be isolated from HIV+ women with symptomatic vaginitis than from asymptomatic HIV+ women. Interestingly, the higher levels of Sap secreted in vitro by C. albicans isolates had a correlate in increased levels of Sap in the vaginal fluids of HIV+ symptomatic subjects compared to levels of the enzyme detected in HIV+, fungal carriers. This result demonstrates that the high potential of the strains to produce Sap was not a mere characteristic of their in vitro growth but likely resulted from selection of strains that produce high levels of Sap in vivo.

These results parallel our previous findings with strains of C. albicans from oral cavities (17). Altogether, these data support the notion that more virulent strains of C. albicans may indeed by isolated from the mucosae of HIV-infected subjects. Enzymes of the Sap family (in particular, Sap2) are well known for their ability to degrade a number of proteins important in host defense, such as Igs, complement, and cytokines (21, 24, 32). Thus, the selection in AIDS patients of strains that produce high levels of Sap might be relevant for the aggressive potential of C. albicans and contribute to the aggravation of host conditions. Recently, Sap production has also been implicated in the enhancement of Candida virulence following HIV gp160 and gp41 binding to the fungus (19).

That Sap production may be relevant to the vaginopathic potential of C. albicans is also supported by our recent studies with an experimental rat vaginitis model, where anti-Sap antibodies of IgA and IgG isotypes, elicited during a primary vaginal infection, were capable of conferring protection to naive, uninfected rats (14, 16). The finding that the particularly high vaginopathic potential of the isolates from the vaginas of HIV+ subjects that produce high levels of Sap can be strongly inhibited by pepstatin A (21) also suggests that inhibitors of Sap synthesis and/or secretion, such as pepstatin A derivatives or analogues, might potentially be useful for vaginitis treatment.

Our antimycotic susceptibility data, obtained by an improved modification of an internationally standardized method of evaluating the triazole sensitivities of clinical isolates of Candida and Cryptococcus species (28), clearly indicated that resistance to efficacious triazole drugs was of low prevalence in our subjects and had no correlation with possible selection of increased proportions of high-level-Sap isolates. It has been shown that fluconazole-resistant cells are present in the infecting C. albicans population and that selective pressure for overgrowth of these clones is conferred upon the fungal cells by prolonged, repeated cycles of antimycotic treatment. However, no virulence correlates were found in the resistant strains (3, 5, 18, 23). A retrospective examination of clinical charts revealed that the great majority of the study subjects had not been treated other than occasionally with fluconazole for their candidiasis recurrences. However, most of them were treated with other azoles (miconazole and ketoconazole), to which several resistant strains were indeed found. In fact the isolation of fluconazole-resistant strains of C. albicans from AIDS patients is a common phenomenon only after prolonged treatment with the drug (3, 5, 18, 23). This fact is consistent with the suggestion that alternating cycles of treatment with different azoles, rather than using a single azole for prolonged periods, might prevent or retard the emergence of isolates resistant to this class of drugs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National AIDS Project, Istituto Superiore di Sanità, contract 940/E.

We are grateful to Anna Botzios and Giuseppina Mandarino for help in the preparation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agatensi L, Franchi F, Mondello F, Bevilacqua R L, Ceddia T, De Bernardis F, Cassone A. Vaginopathic and proteolytic Candida species in outpatients attending a gynecology clinic. J Clin Pathol. 1991;44:826–830. doi: 10.1136/jcp.44.10.826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agresti M G, De Bernardis F, Mondello F, et al. Clinical and mycological evaluation of fluconazole in the secondary prophylaxis of esophageal candidiasis in AIDS patients. Eur J Epidemiol. 1994;10:17–20. doi: 10.1007/BF01717446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2a.Barchiesi, F., et al. Submitted for publication.

- 3.Barchiesi F, Hollis R J, Delpoeta M, McGough D A, Scalise G, Rinaldi M, Pfaller M A. Transmission of fluconazole-resistant Candida albicans between patients with AIDS and oropharyngeal candidiasis documented by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:561–564. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.3.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barchiesi F A, Colombo L, McGough D A, Fothergill A W, Rinaldi M G. In vitro activity of itraconazole against fluconazole-susceptible and -resistant Candida albicans isolates from oral cavities of patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:1530–1533. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.7.1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bart-Delabesse E, Boiron P, Carlotti A, Dupont B. Candida albicans genotyping in studies with patients with AIDS developing resistance to fluconazole. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2933–2937. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.11.2933-2937.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boerlin P, Berlin-Petzold F, Durussel C, Addo M, Pagani J L, Chave J P, Bille J. Cluster of oral atypical Candida albicans isolates in a group of human immunodeficiency virus-positive drug users. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1129–1135. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.5.1129-1135.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brawner D L, Cutler J E. Oral Candida albicans isolates from nonhospitalized normal carriers, immunocompetent hospitalized patients, and immunocompromized patients with or without acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:1335–1341. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.6.1335-1341.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruatto M, Vidotto V, Marinuzzi G, Raiteri R, Sinicco A. Candida albicans biotypes in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected patients with oral candidiasis before and after antifungal therapy. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:726–730. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.4.726-730.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cantorna M T, Balish E. Role of CD4+ lymphocytes in resistance to mucosal candidiasis. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2447–2455. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.7.2447-2455.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cassone A, De Bernardis F, Mondello F, Ceddia T, Agatensi L. Evidence for a correlation between proteinase secretion and vulvovaginal candidiasis. J Infect Dis. 1987;156:777–783. doi: 10.1093/infdis/156.5.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cutler J E. Putative virulence factors of Candida albicans. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1991;45:187–218. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.45.100191.001155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Bernardis F, Agatensi L, Ross I K, Emerson G W, Lorenzini R, Sullivan P A, Cassone A. Evidence for a role for secreted aspartate proteinase of Candida albicans in vulvovaginal candidiasis. J Infect Dis. 1990;161:1276–1283. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.6.1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Bernardis F, Boccanera M, Rainaldi L, Guerra C E, Quinti I, Cassone A. The secretion of aspartyl proteinase, a virulence enzyme, by isolates of Candida albicans from the oral cavity of HIV-infected subjects. Eur J Epidemiol. 1992;8:362–367. doi: 10.1007/BF00158569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Bernardis F, Cassone A, Sturtevant J, Calderone R A. Expression of Candida albicans SAP1 and SAP2 in experimental vaginitis. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1887–1892. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1887-1892.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Bernardis F, Chiani P, Ciccozzi M, Pellegrini G, Ceddia T, D’Offizi G, Quinti I, Sullivan P, Cassone A. Elevated aspartyl proteinase secretion and experimental pathogenicity of Candida albicans isolates from oral cavities of subjects infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Infect Immun. 1996;64:466–471. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.2.466-471.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Bernardis F, Boccanera M, Adriani D, Spreghini E, Santoni G, Cassone A. Protective role of antimannan and anti-aspartyl proteinase antibodies in an experimental model of Candida albicans vaginitis in rats. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3399–3405. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.8.3399-3405.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Bernardis, F., S. Arancia, L. Morelli, B. Hube, D. Sanglard, W. Schäfer, and A. Cassone. Evidence that members of the secretory aspartyl proteinase gene family (SAP), in particular SAP2, are virulence factors for Candida vaginitis. J. Infect. Dis., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Fothergill A W, Rinaldi M G. Variations in fluconazole susceptibility and electrophoretic karyotype among oral isolates of Candida albicans from patients with AIDS and oral candidiasis. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:59–64. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.1.59-64.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gruber A, Lukasser-Volg E, Borg-von Zeplin M, Dierich M P, Wurzner R. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp160 and gp41 binding to Candida albicans selectively enhanced Candida virulence in vitro. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:1057–1063. doi: 10.1086/515231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holmberg K, Meyer R D. Fungal infections in patients with AIDS and AIDS-related complex. Scand J Infect Dis. 1986;18:179–185. doi: 10.3109/00365548609032326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hube B. Candida albicans secreted aspartyl proteinases. Curr Top Med Mycol. 1996;7:55–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iman N, Carpenter C J, Kenneth H M, Fisher A, Stein M, Danforth S B. Hierarchical pattern of mucosal candidal infection in HIV-seropositive women. Am J Med. 1990;89:142–146. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(90)90291-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson M E, Warnok D W, Lukers J, Porter S R, Scully C. Emergence of azole drug resistance in Candida species from HIV-infected patients receiving prolonged fluconazole therapy for oral candidosis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1995;35:103–114. doi: 10.1093/jac/35.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaminishi H, Miyaguchi H, Tamaki T, Suenaga N, Hisamatsu M, Mihashi I, Matsumoto H, Maeda H, Hagihara Y. Degradation of humoral host defense by Candida albicans proteinase. Infect Immun. 1995;63:984–988. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.3.984-988.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klein R S, Harris C A, Butkus Small C, Moll B, Lesser M, Friendland G H. Oral candidiasis in high risk patients as the initial manifestation of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:354–357. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198408093110602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lupetti A, Guzzi G, Paladini A, Swart K, Campa M, Senesi S. Molecular typing of Candida albicans in oral candidiasis: karyotype epidemiology with human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients in comparison with that with healthy carriers. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1238–1248. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.5.1238-1242.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mondello F, Guglielminetti A, Torosantucci A, Ceddia T, Agatensi L, Cassone A. Yeast species isolated from outpatients with vulvovaginal candidosis attending a gynecological center in Rome. IRCS (Int Res Commun Syst) Med Sci. 1986;14:746–747. [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts. Proposed standard M27-T. Vol. 15. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Odds F C. Candida and candidosis. London, United Kingdom: Baillière Tindall; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ollert M W, Wende C, Gorlich M, McMullan-Vogel C G, Borg-Von Zepelin M, Vogel C W, Korting H C. Increased expression of Candida albicans secretory proteinase, a putative virulence factor, in isolates from human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2543–2549. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.10.2543-2549.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quinti I, Palma C, Guerra E C, Gomez M J, Mezzaroma I, Aiuti F, Cassone A. Proliferative and cytotoxic responses to mannoproteins of Candida albicans by peripheral blood lymphocytes of HIV-infected subjects. Clin Exp Immunol. 1991;85:485–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1991.tb05754.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ruchel R, De Bernardis F, Ray T L, Sullivan P A, Cole G T. Candida acid proteinases. J Med Vet Mycol. 1992;29(Suppl.):1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmid J, Odds F C, Wiselka M J, Nicholson G, Soll D R. Genetic similarity and maintenance of Candida albicans strains from a group of AIDS patients, demonstrated by DNA fingerprinting. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:935–941. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.4.935-941.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sullivan D, Bennett D, Henman M, Harwood P, Flint S, Mulcahy F, Shanley D, Coleman D. Oligonucleotide fingerprinting of isolates of Candida species other than C. albicans and of atypical Candida species from human immunodeficiency virus-positive and AIDS patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2124–2133. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.8.2124-2133.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Torosantucci A, Bromuro C, Gomez M J, Ausiello C M, Urbani F, Cassone A. Identification of a 65 kDa mannoprotein constituent as a main target of human cell-mediated immune response to Candida albicans. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:427–435. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.2.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsuchiya T, Taguchi M, Fukazawa Y, Shinoda T. Serological characterization. Methods Microbiol. 1984;16:75–76. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Whelan W L, Kirsch D R, Kwon-Chung K J, Wahl S M, Smith P D. Candida albicans in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: absence of a novel or hypervirulent strain. J Infect Dis. 1990;162:513–518. doi: 10.1093/infdis/162.2.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]