Abstract

Background

Clinical features, treatment, and outcome of opportunistic infections with Rasamsonia spp., a nonpigmented filamentous mold, are not well documented in dogs.

Objectives

Describe clinical, radiographic, pathologic features, and outcome of dogs with disseminated Rasamsonia species complex infections.

Animals

Eight client‐owned dogs.

Methods

Retrospective case series. Medical records were reviewed to describe signalment, history, clinicopathologic and imaging findings, microbiologic and immunologic results, cyto‐ and histopathologic diagnoses, treatment, and outcome.

Results

Presenting complaints were nonspecific with anorexia (n = 5) and back pain (n = 4) most common. Five dogs were German Shepherd dogs. Six dogs had multifocal discospondylitis and 2 had pleural effusion. Six dogs had Rasamsonia piperina and 2 had Rasamsonia argillacea infections with isolates identified using DNA sequencing. Rasamsonia spp. were isolated by urine culture in 5 of 7 dogs. Five of 6 dogs had positive serum Aspergillus galactomannan antigen enzyme immunoassay (EIA) results. Median survival time was 82 days, and 317 days for dogs that survived to discharge. Four died during initial hospitalization (median survival, 6 days). All isolates had low minimum effective concentrations (MECs) to echinocandins with variable minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) for azole antifungal drugs.

Conclusions and Clinical Importance

Rasamsonia spp. infections in dogs are associated with multisystemic disease involving the vertebral column, central nervous system, kidneys, spleen, lymph nodes, lungs, and heart. The infection shares clinical features with other systemic mold infections and can be misidentified when using phenotypical microbiologic methods. Molecular techniques are required to identify the organism and guide appropriate antifungal treatment.

Keywords: canine, discospondylitis, fungal, microbiology, Rasamsonia

Abbreviations

- ABLC

amphotericin B lipid complex

- CLSI

clinical and laboratory standards institute

- CT

computed tomography

- EIA

enzyme immunoassay

- GMI

galactomannan index

- GMS

Gomori's methenamine silver

- H&E

hematoxylin and eosin

- IMA

inhibitory mold agar

- ITS

internal transcribed spacer

- MALDI‐TOF

matrix‐assisted laser desorption time‐of‐flight

- MEC

minimum effective concentration

- MIC

minimum inhibitory concentration; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging

- VMTH

Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital

1. INTRODUCTION

Disseminated mold infections are rare in dogs, but the identification of opportunistic species has been enhanced by the availability of molecular techniques such as DNA sequencing. These infections typically are diagnosed in dogs known or speculated to be immunodeficient.1 Aspergillus terreus, Aspergillus deflectus, and Aspergillus niger each have been reported to result in disseminated infections and German Shepherd dogs appear to be overrepresented, although the disease also has been reported in other dog breeds.2 A variety of other molds, including Penicillium spp., Talaromyces spp., and Paecilomyces spp., also can cause disseminated infections in dogs.3, 4, 5, 6

Accurate identification of an infecting mold species requires PCR‐based techniques, genetic sequencing, or matrix‐associated laser desorption ionization‐time of flight (MALDI‐TOF) mass spectrometry, without which organisms may be misidentified based on their phenotypic morphology in culture alone. Consequently, some isolates from fungal infections previously may have been identified incorrectly, preventing thorough analysis of risk factors and therapeutic success.7

Rasamsonia is a recently described genus of saprobic thermotolerant fungal organisms of the Trichocomaceae family, first described in 2011. Rasamsonia are nonpigmented, filamentous fungi also known as hyalohyphomycetes. The Rasamsonia argillacea species complex includes 4 species that share phenotypic and genetic similarities: R argillacea, Rasamsonia eburnea, Rasamsonia piperina, and Rasamsonia aegroticola. The genus Rasamsonia previously was classified as Talaromyces and Geosmithia, but was reclassified in 2012 based on sequencing of the RPB2, TSR1, and CCT8 genes.8, 9 Rasamsonia spp. are phenotypically similar to Paecilomyces spp. in that they are thermotolerant to thermophilic and have similar morphologic features, making correct species identification reliant upon DNA sequencing.8, 10

Although previously considered to be a rare pathogen of humans and animals, there have been recent reports of immunocompetent and immunocompromised human patients with invasive and disseminated infection. Rasamsonia spp. have been described as pathogens of dogs in 4 case reports.7, 11, 12, 13 Three of the 4 dogs were German Shepherd dogs evaluated for multisystemic clinical signs and were euthanized because of progressive disease and declining quality of life. To draw more broad conclusions about manifestations of disease, diagnostic methodology, treatment, and outcomes, we sought to provide a retrospective description of 8 dogs diagnosed with Rasamsonia infections, confirmed by culture and DNA sequencing.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Criteria for selection of dogs

A search of the electronic medical record system at the William R. Pritchard Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital (VMTH) from 2003 to 2020 was performed using the keywords “Rasamsonia” and “Geosmithia.” Dogs were considered to have mold infections if Rasamsonia was isolated from a typically sterile body location, and were characterized as having disseminated disease if there was evidence of multisystemic involvement or focal disease if the infection was confined to a single organ system.

2.2. Data collection

Data collected on all dogs included signalment, clinical history, physical examination findings at initial presentation to the VMTH, clinical laboratory results (including cytology, immunoassays, microbial culture, and sequencing), diagnostic imaging, biopsy or necropsy results, and clinical outcomes. Only clinicopathologic data analyzed by the VMTH clinical laboratory or submitted to external laboratories by VMTH clinicians were included for analysis.

2.3. Fungal isolation, identification, and susceptibility testing

Fungal isolation and initial morphological testing and identification all were performed at the VMTH Clinical Microbiology Laboratory. Briefly, clinical specimens were inoculated onto inhibitory mold agar (IMA; Hardy Diagnostics, Santa Maria, California) and incubated at 30°C in room atmosphere. Blood culture bottles were incubated at 35°C and subcultured at 3, 5, and 14 days of incubation to IMA and incubated at 30°C. Initial mold growth was subcultured to potato flake agar (Biological Media Services, UC Davis) and microscopic morphology was examined by tape preparations using lactophenol alanine blue staining. Definitive species identification by sequencing of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region, partial β‐tubulin, and calmodulin genes, as well as antifungal susceptibility testing, were performed by the Fungus Testing Laboratory at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio as described previously.9 Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) for amphotericin B and the azoles were determined as the lowest concentration that inhibited growth of the isolates. Minimum effective concentrations (MECs) for the echinocandins were defined as the lowest concentration that resulted in morphologic changes characterized by short, stubby hyphae with abnormal branching.

2.4. Immunologic assays

Aspergillus Platelia galactomannan enzyme immunoassay testing (EIA; Bio‐Rad, Hercules, California) was performed at Mira Vista Diagnostics (Indianapolis, Indiana).

2.5. Diagnostic imaging

All diagnostic imaging and echocardiograms were performed at the VMTH and interpreted either by a board‐certified specialist or resident under direct supervision of a board‐certified radiologist or cardiologist, respectively.

2.6. Histologic examination

Biopsy and necropsy samples were submitted to the VMTH Anatomic Pathology service. Tissues were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin wax, and 5‐μm sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Gomori's methenamine silver (GMS) stain.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Data are presented using descriptive statistics as median (range). Survival analysis was performed using Kaplan‐Meier survival plots and was based on length of survival from the date of initial presentation at our institution or initiation of antifungal medication before referral. Analysis and figures were completed using commercially available software (SAS v. 9.4, Cary, North Carolina).

3. RESULTS

Eight dogs were identified with R argillacea species complex infections. All dogs had disseminated disease and were patients of the VMTH between January 2013 and June 2019 and lived in California. Five of the 8 dogs were German Shepherd dogs, and 6 dogs were spayed females (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Signalment and presenting signs of 8 dogs with disseminated Rasamsonia spp. infections

| Age (years) | 3 (2‐7) |

| Sex | 6 FS, 2 M (1 intact M) |

| Breeds |

German Shepherd Dog (n = 5) Hungarian Vizsla (n = 1) Husky (n = 1) Mixed breed (n = 1) |

| Presenting Signs | |

| Gastrointestinal |

Hyporexia (n = 5) Diarrhea (n = 3) Vomiting (n = 2) |

| Orthopedic |

Apparent back pain (n = 4) Pelvic limb lameness (n = 1) |

| Neurologic |

Ataxia (n = 2) Stargazing and vestibular signs (n = 1) |

| Respiratory |

Tachypnea (n = 1) Cough (n = 1) |

| Other | PU/PD (n = 1) |

Note: Data are presented as median (range) or total number. Site of infection based on ante mortem clinical evidence (n = 8) or necropsy findings (n = 5).

Abbreviations: FS, female spayed; M, male; PU/PD, polyuria/polydipsia.

Seven of 8 dogs were evaluated at the VMTH within 1 month of onset of clinical signs (median, 27 days; range, 7‐160 days). No dog had a previous history of musculoskeletal, neurologic, or invasive fungal disease. One dog had a history of travel to Hawaii, but no travel was reported beyond local areas for the remaining 7 dogs.

The most common historical complaints were poor appetite (n = 5) and apparent back pain (n = 4, Table 1). Two dogs had received extensive diagnostic evaluations by veterinary specialists; advanced imaging confirmed the presence of multifocal discospondylitis, but fungal serologic antibody testing was negative. Fungal etiology still was suspected, and both dogs were treated with voriconazole PO before referral.

3.1. Physical examination

On physical examination at the VMTH, most dogs were alert (n = 3) to quiet (n = 4) and responsive. Two dogs had increased body temperatures, but median body temperature was normal (101.6°F; range, 100.7‐103.3°F). Remaining physical examination findings included: pulse rate 121 beats/min (range, 108‐176/min), respiratory rate 42 breaths/min (range, 28‐62/min), weight 25.9 kg (range, 17.0‐30.8 kg), and body condition score 4/9 (range, 3/9‐5/9). Additional findings included peripheral lymphadenomegaly (n = 3), absent lung sounds bilaterally (n = 1), and tense abdomen on palpation (n = 4). No dogs had palpable organomegaly.

Neurologic examinations were performed by a board‐certified veterinary neurologist on 5 dogs. Four dogs had evidence of back pain with a neuroanatomic diagnosis of cervical (n = 1) and thoracolumbar myelopathy (n = 3). The remaining dog had a neuroanatomic localization of C6‐T2 myelopathy with possible brain involvement; this dog was nonambulatory and tetraparetic, with bilateral Horner's syndrome, absent biceps, triceps, and flexor reflexes in the thoracic limbs bilaterally, and absent cutaneous trunci reflex. Absent nociception in the thoracic limbs bilaterally and marked apparent pain were noted during the examination.

Fundic examinations were performed in 6 dogs and were reported to be normal in 4 dogs. One dog had evidence of chorioretinitis OU and the other had anterior uveitis with a suspected fungal granuloma and focal retinal detachment OD, confirmed by a board‐certified veterinary ophthalmologist.

3.2. Clinicopathologic data

Complete blood count (Table 2), serum biochemistry panels (Table 3), and urinalyses (Table 4) were available for 7 dogs within 1 week of the initial evaluation.

TABLE 2.

Selected hematology results from 7 dogs with disseminated Rasamsonia spp. infections

| Median (range) | Reference interval | |

|---|---|---|

| Hematocrit (%) | 43.9 (29.1‐55.5) | 40‐55 |

| Anemia | 1/7 | N/A |

| MCV (fL) | 67.7 (64.1‐71.5) | 65‐75 |

| Microcytosis | 1/7 | N/A |

| MCHC (g/dL) | 33.7 (32.0‐35.2) | 33‐36 |

| Hypochromsia | 3/7 | N/A |

| WBC count (cells/μL) | 12 940 (10 060‐28 265) | 6000‐13 000 |

| Leukocytosis | 3/7 | N/A |

| Neutrophil count (cells/μL) | 8570 (6172‐23 743) | 3000‐10 500 |

| Neutrophilia | 3/7 | N/A |

| Band count (cells/μL) | 0 (0‐1413) | rare |

| Left shift | 1/7 | N/A |

| Lymphocyte count (cells/μL) | 2193 (1082‐5719) | 1000‐4000 |

| Lymphocytosis | 1/7 | N/A |

| Eosinophil count (cells/μL) | 207 (0‐1136) | 0‐1500 |

| Basophil count (cells/μL) | 19 (0‐34) | 0‐50 |

| Platelet count (cells/μL) | 213 000 (167 000‐363 000) | 150 000‐400 000 |

| MPV (fL) | 11 (8.9‐15.2) | 7‐13 |

Abbreviations: MCHC, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration, MCV, mean corpuscular volume, MPV, mean platelet volume, N/A, not applicable.

TABLE 3.

Selected serum biochemistry panel results from 7 dogs with disseminated Rasamsonia spp. infections

| Median (range) | Reference interval | |

|---|---|---|

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 9.9 (8.8‐11.5) | 9.6‐11.2 |

| Phosphorus (mg/dL) | 4.9 (4.0‐6.3) | 2.6‐5.2 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.8 (0.3‐1.2) | 0.8‐1.5 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 16 (8‐20) | 11‐33 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 2.7 (2.1‐3.7) | 3.4‐4.3 |

| Globulin (g/dL) | 3.2 (2.5‐5.9) | 1.7‐3.1 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 24 (9‐822) | 21‐72 |

| AST (IU/L) | 33 (21‐118) | 20‐49 |

| ALP (IU/L) | 136 (17‐3642) | 14‐91 |

| GGT (IU/L) | 3 (2‐151) | 0‐5 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | <0.2 (0.1‐8.1) | 0.0‐0.2 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 206 (119‐371) | 139‐353 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 112 (66‐124) | 86‐118 |

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine transferase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; AST, aspartate transaminase; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; GGT, gamma‐glutamyl transferase.

TABLE 4.

Selected urinalysis results from 7 dogs with disseminated Rasamsonia spp. infections

| Median (range) | Reference interval | |

|---|---|---|

| Specific gravity | 1.021 (1.005‐1.032) | N/A |

| pH | 6.5 (6.0‐8.0) | N/A |

| Proteinuria (mg/dL) | 0 (0‐75) | Negative |

| Hematuria | 18‐24 ((0‐2)‐(50‐100)) | 0‐2/hpf |

| Pyuria | 0‐3 ((0‐3)‐(4‐10)) | 0‐3/hpf |

| Cylindruria | 0 (0‐0) | None/lpf |

Note: Fungal elements were not identified on sediment examination in any sample.

Abbreviations: hpf, high power field; lpf, low power field; N/A, not applicable.

Hyperglobulinemia and hypoalbuminemia were the most common abnormalities (n = 4). Only 1 dog with hyperglobulinemia had concurrent hypoalbuminemia. In 1 dog, hypercholesterolemia (371 mg/dL; reference range, 150‐300 mg/dL) and hyperbilirubinemia (8.1 mg/dL; reference range, <0.2 mg/dL) accompanied markedly increased alkaline phoshatase (ALP, 3642 IU/L; reference range, 20‐80 IU/L) and gamma‐glutamyl transferase (GGT) activities (151 IU/L; reference range, 0‐5 IU/L). Three dogs had mild increases in ALP activity and although serum bilirubin and cholesterol concentrations were normal in 2 of these dogs, 1 dog had hypocholesterolemia (Table 3).

3.3. Diagnostic imaging

Survey radiography of the thorax and abdominal ultrasonographic examinations were performed on 7 dogs. Thoracic radiographs confirmed the presence of lesions consistent with multifocal discospondylitis in 5 dogs. Both dogs without evidence of discospondylitis had pleural effusion and hilar lymphadenomegaly. Five had moderate to marked multicentric lymphadenomegaly on abdominal ultrasonography. Lymph nodes generally were described as being hypoechoic and rounded. Three dogs had diffuse small (<0.1 cm) hypoechoic splenic nodules; 1 of these dogs had a splenic vein filling defect consistent with a splenic vein thrombus. Three dogs had echocardiograms performed; there was no evidence of valvular lesions consistent with vegetative endocarditis in any dog.

Imaging of the spine was performed in 5 dogs and consisted of a vertebral column radiographic series (n = 4), computed tomography (CT) scan (n = 2), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI; n = 3). Lesions consistent with multifocal discospondylitis were identified in all 5 dogs including cervical (n = 3), thoracic (n = 5), and lumbar (n = 3) vertebrae with lytic and sclerotic lesions identified most often between T6 and T11. Additionally, MRI findings were consistent with regionally extensive empyema and multifocal neuritis resulting in spinal cord compression at C6 and T2 in 1 dog and circumferential paraspinal contrast enhancement around the lumbosacral disc space in another.

3.4. Cytology and histopathology findings

Results of cytologic examination of tissue and fluid aspirates from 4 dogs are summarized in Table S1. Pyogranulomatous inflammation and multinucleated giant macrophages with fungal elements were identified in lymph node specimens (mesenteric, sublumbar, and popliteal) in 3 of 4 dogs and in intervertebral disc aspirates from 1 of 2 dogs. Septate fungal elements measured 2‐4 μm in diameter with mostly parallel walls and variable pink internal staining (Figure 1). Cytologic examination of splenic aspirates from 3 dogs indicated lymphoid hyperplasia, from 2 dogs extramedullary hematopoiesis, and from 1 dog suppurative inflammation, but no evidence of fungal pathogens. Analysis of pleural fluid from 2 dogs disclosed a pyogranulomatous exudate without fungal elements in 1 dog and suppurative and eosinophilic inflammation without fungal elements in the other. One of these dogs also had peritoneal effusion, which consisted of a modified transudate without cytologic evidence of fungal hyphae.

FIGURE 1.

Cytology impression from a mass in the ventral aspect of the vertebral canal, adjacent to the spinal cord that was surgically excised in a Husky infected with Rasamsonia piperina. Septate fungal hyphae are observed in a few large mats and individually, occasionally in association with cell clumps (×600). Image courtesy of (MASKED), DVM, PhD, DACVP (clinical pathology)

Biopsy specimens were collected from 1 dog after surgical decompression of an extradural mass by dorsal hemilaminectomy. Histopathology of this mass disclosed pyogranulomatous inflammation with intralesional fungal hyphae. Occasionally, fungal hyphae formed radiating basophilic mats up to 2 μm in diameter that were surrounded by a rim of epithelioid macrophages. Silver staining confirmed the presence of septate hyphae with a dichotomous to perpendicular branching pattern.

3.5. Microbiologic and immunologic findings

Aspergillus galactomannan EIA was performed on specimens from 6 dogs (1 serum only, 5 serum and urine). Serum was antigen positive in 5/6 dogs with a median index of 7.92 (range, 0.33‐10.5; reference range, <0.5). Urine was antigen positive in 3/5 dogs with a median index of 2.26 (range, 0.07‐6.11; reference range, <0.5). One dog was serum antigen galactomannan index (GMI) positive (8.53) but was urine antigen GMI negative (0.41). The dog with a negative serum GMI (0.33) also had a negative urine test result (0.07; Table S1).

Additional serologic testing included Coccidioides spp. antibody serology (n = 2), latex Cryptococcus spp. antigen test (n = 1), and Brucella spp. rapid slide agglutination test (n = 1); all of which were negative.

3.6. Culture and susceptibility testing

Fungal colonies were isolated from urine specimens in 5 dogs (by fungal culture in 4 dogs and aerobic bacterial culture in 1 dog). Two of these dogs had initial urine fungal cultures that were negative. Urine culture yielded no growth in 2 other dogs (fungal, n = 1; aerobic bacterial, n = 1). Blood cultures yielded fungal growth in 2 of 4 dogs, and from 1 of these 2, fungal colonies also were isolated from pleural fluid. The other dog had multiple urine cultures that yielded no growth and negative serum and urine Aspergillus EIAs. Fungal culture of lymph node aspirates yielded growth in 3 of 4 dogs. Fungal culture of intervertebral disc aspirates yielded fungal growth in 2 of 5 dogs (Table S1).

Isolates from all 8 dogs were identified at the species level using PCR sequencing; 6 dogs were infected with R piperina and 2 dogs were infected with R argillacea. Molecular testing including sequencing of the partial β‐tubulin (n = 7) and calmodulin (n = 3) genes, the D1/D2 region of the large ribosomal subunit (n = 2), and the ITS region (n = 6). Before PCR sequencing, 4 isolates were misidentified using colony and microscopic morphology, 3 as Paecilomyces sp. and 1 as Penicillium sp. Percent identities were >99% for each DNA sequence with reference isolates. GenBank accession numbers and percent matches are provided in Table S2.

Antifungal susceptibility testing was performed on 5 isolates. Although Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) interpretation guidelines are not available for Rasamsonia spp. infections, guidelines used in humans based on Aspergillus fumigatus susceptibility were used to facilitate drug selection. All MECs were low for the echinocandins. Other antifungal drugs that had in vitro activity included amphotericin B, itraconazole, and posaconazole, all with low MICs. In contrast, in vitro activity to fluconazole was not observed in any isolates and was observed only to voriconazole in 1 of 4 isolates (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Antifungal susceptibility results from 5 dogs with disseminated Rasamsonia spp. infections

| Antifungal (# of MICs tested against isolates) | MIC/MEC range (mode) | Published MIC/MEC range (mode) |

|---|---|---|

| Amphotericin B (n = 4) | ≤0.03‐1.0 (1) | 0.125‐8 (0.5) |

| Anidulafungin (n = 4) | ≤0.015 | — |

| Caspofungin (n = 4) | 0.03‐0.125 (0.06) | ≤0.015‐0.125 (0.125) |

| Micafungin (n = 5) | ≤0.015 | — |

| Fluconazole (n = 3) | >64 | — |

| Itraconazole (n = 3) | 0.06‐2.0 (0.125) | ≤0.03‐16 (0.5) |

| Posaconazole (n = 4) | ≤0.03‐1.0 (0.125) | ≤0.03‐1 (0.5) |

| Voriconazole (n = 4) | 0.125 to >16 (>16) | 4 to ≥16 (≥16) |

Note: Range (mode) of minimum inhibitory/effective concentration (MIC/MEC) is represented in μg/mL.

Abbreviations: MEC, minimum effective concentration; MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration.

Source: Published MIC/MEC data adapted from Borman et al.14

3.7. Treatment

Before culture and MEC and MIC results were available, treatment included amphotericin B lipid complex (ABLC; Abelcet, Lediant Biosciences, Gaithersburg, Maryland) IV (n = 2), ABLC IV with itraconazole (Sporanox, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Raritan, New Jersey) PO (n = 1), and voriconazole (Vfend, Pfizer, New York) PO (n = 3). Dogs that received ABLC were given infusions of 3 mg/kg IV over 2 hours on a Monday/Wednesday/Friday schedule. The median PO voriconazole dose was 3.6 mg/kg q12h. The itraconazole dose used was 6.6 mg/kg PO q12h for 1 week and q24h thereafter. Two dogs received no antifungal drug treatment and either died or were euthanized <3 days after presentation.

One dog was maintained on the same drug for the duration of treatment. This dog received PO voriconazole and continued to receive this drug because the MIC appeared to be favorable at 0.125 μg/mL. Disease progressed in this dog, and the owners declined parenteral antifungal treatment. Another dog received voriconazole in hospital but developed cardiopulmonary arrest and died 24 hours after beginning treatment.

After identification of Rasamsonia spp. infection and receipt of susceptibility testing results, antifungal treatment was altered in 4 dogs because of progressive disease manifestations and results that suggested in vitro resistance. Two dogs were prescribed posaconazole: 1 of these dogs received it in conjunction with existing ABLC therapy, the other as a replacement for voriconazole (7 mg/kg q24h and 4.7 mg/kg q48h, respectively). These dogs eventually were transitioned to echinocandins. Two other dogs were immediately transitioned to treatment with echinocandins based on susceptibility testing. Three dogs received micafungin (initially 2 mg/kg IV q24h for 6 weeks; Mycamine, Astellas Pharma, Tokyo, Japan) and 1 dog received caspofungin (1 mg/kg IV q24h for 4 weeks; Cancidas, Merck & Co, Kenilworth, New Jersey). One dog was started on itraconazole (6.5 mg/kg PO q24h) after week 4 of micafungin administration because of progressive clinical signs and radiographic evidence of discospondylitis.

Additionally, all dogs received analgesic medications or anti‐inflammatory medications including gabapentin (Neurontin, Pfizer, New York), tramadol (Ultram, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Raritan, New Jersey), amantadine (Gocovri, Adamas Pharmaceuticals, Emeryville, California), cannabidiol, grapiprant (Galliprant, Elanco, Greenfield, Indiana), or carprofen (Rimadyl, Zoetis, Kalamazoo, Michigan). Two dogs with indwelling IV access received clopidogrel (Plavix, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, New York) because of concern for thromboembolic disease and evidence of thrombus formation associated with the jugular catheter, respectively. An esophagostomy tube was placed because of prolonged hyporexia in 1 dog; this dog also required thoracocentesis every 2‐3 days because of persistent pleural effusion.

3.8. Clinical outcome

Median survival time for all 8 dogs was 82 days. Four dogs died or were euthanized during their initial hospitalization as a result of their disease; median survival in these dogs was 6 days (range, 0‐79 days). Of those, 1 dog died and 1 was euthanized before antifungal treatment, and 3 of these dogs were euthanized or died 8‐30 days before receipt of fungus identification. An additional 4 dogs survived to discharge but eventually died or were euthanized as a result of deterioration in their quality of life. Median survival time for dogs surviving to discharge was 317 days (range, 84‐676 days).

3.9. Necropsy findings

Necropsy was performed in 5 dogs; diagnosis was made at necropsy in 2 dogs and confirmed in 3 dogs. Detailed organ involvement of each dog is listed in Table S1. In summary, disseminated pyogranulomatous inflammation with fungal organisms was identified in lymph nodes (n = 5), spleen (n = 5), kidneys (n = 5), liver (n = 4), lungs (n = 3), myocardium (n = 3), intervertebral disc (n = 3), vertebral bodies (n = 2), brain (n = 2), adrenal glands (n = 2), and in nasal cavity, stomach, pancreas, portal vein, vena cava, humerus, skeletal muscle, eyes, and spinal cord (1 dog each). One dog with fungal myocarditis also had systemic fungal arteritis (Figure 2). Both dogs with brain involvement at necropsy had antemortem evidence of uveitis on initial examination.

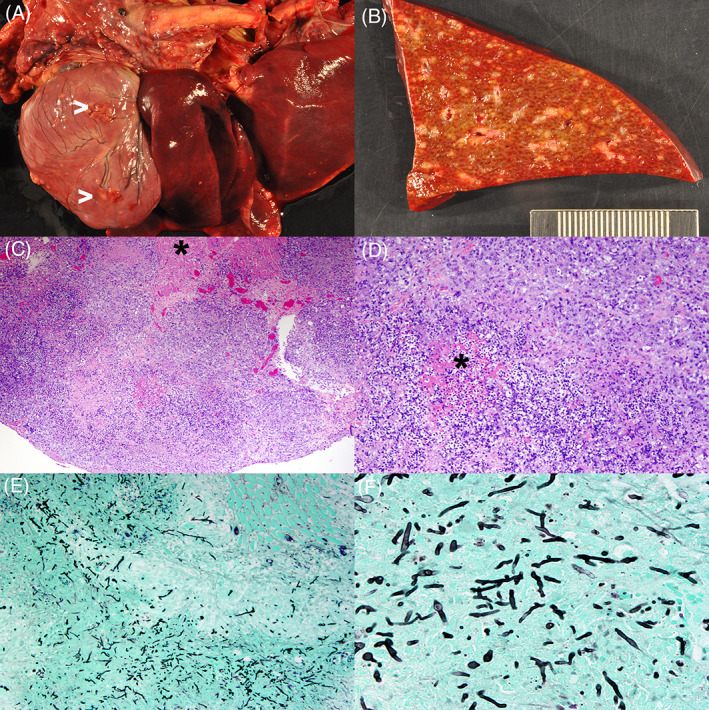

FIGURE 2.

Images from a Hungarian Vizsla infected with Rasamsonia piperina. Gross images revealing multifocal epicardial and myocardial granulomas (>) with inflammation in the mediastinum (A) and a cross‐section through liver parenchyma with disseminated and coalescing granulomas (B). Photomicrographs of tissue stained with H&E showing a large portion of the myocardium effaced by a dense cellular infiltrate with necrosis, sparing a small area of myocardium (*; C, ×40) and a central area of necrosis (*) surrounded by neutrophils, histiocytes as well as plasma cells and lymphocytes (D, ×100). Photomicrographs of tissue stained with GMS showing innumerous fungal hyphae within the inflammatory nodules (E, ×100) and branching septate fungal elements with mostly parallel walls (F, ×400). GMS, Gomori's methenamine silver; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin

Microbial culture from liver (n = 1), lymph node (n = 2), vertebral body (n = 2), or spinal cord (n = 1) specimens collected at necropsy yielded Rasamsonia sp. In addition, Candida albicans was isolated from 1 dog's lymph node.

4. DISCUSSION

Rasamsonia infections in dogs may be associated with multisystemic disease, and German Shepherd dogs account for 5 of 8 dogs in this group. This observation is consistent with previous reports that documented overrepresentation of German Shepherd dogs with Rasamsonia infections as well as other disseminated mold infections such as aspergillosis.2

Consistent with other case reports, clinicopathologic evaluation of these dogs infected with Rasamsonia indicated changes compatible with chronic inflammation. A single dog had marked cholestatic hepatopathy that might have been a consequence of an extrahepatic biliary obstruction, but also might represent hepatic infection with Rasamsonia.

Similar to other systemic mold infections such as aspergillosis, and in agreement with previous case reports of Rasamsonia infections, discospondylitis with or without vertebral osteomyelitis was a common finding in this cohort of dogs.2, 7, 11, 13 Dissemination of Rasamsonia is not typical in human patients and accounted for only 30.4% of infected human patients with widespread disease in a recent study, a finding associated with immunosuppression.10 Typically, Rasamsonia is isolated from airway washes in humans with cystic fibrosis.15 This finding is in contrast with the cases described in our study, where only 3 dogs exhibited granulomatous pulmonary lesions with intralesional fungi but no pre‐existing clinical or pathological evidence of underlying respiratory disease.

Definitive identification of an invasive mold species improves our understanding of the spectrum of fungal infections in dogs. In our study, PCR sequencing was critical to correctly speciate the fungi. Based on morphologic and standard microbiologic testing, several isolates in our study initially were identified as Paecilomyces or Penicillium spp. This finding is similar to reports of invasive Rasamsonia infections in people where 47.8% of isolates initially were misidentified.10 Moreover, 5 of 6 dogs tested in our study were Aspergillus galactomannan EIA positive, emphasizing the potential for cross‐reactivity and misidentification of Rasamsonia species. Previous studies have found similar results, but with GMI typically lower than was measured in our study (i.e., false positives in 1 study reported to have a mean GMI of 3.17 compared to 7.92 in our study).16

No interpretative criteria currently exist for antifungal susceptibility tests in dogs. Therefore, predicting clinical efficacy based on in vitro susceptibility is problematic. However, our MIC and MEC results are consistent with those previously reported in the literature.14, 17 Four of 5 isolates in our study had high MICs to voriconazole, consistent with antifungal susceptibility test results for isolates from both dogs and humans.7, 13, 17, 18, 19 This observation is important, because voriconazole is commonly the initial drug of choice for disseminated aspergillosis in dogs and, with inaccurate identification of the fungus, clinicians might inadvertently select an antifungal drug to which Rasamsonia spp. are generally resistant.20 Interestingly, 1 isolate from a dog that received voriconazole throughout treatment had a low voriconazole MIC (0.125 μg/mL), which is in contrast to the other voriconazole MIC results in our study and what others have reported, where intrinsic voriconazole resistance has been noted.14, 19 The species identification of this isolate and the voriconazole MICs were confirmed by repeat testing.

Susceptibility testing performed on isolates from 5 dogs and MIC and MEC data are similar to previous reports from isolates from humans. All isolates in our study had low MECs to echinocandins, as has been shown for isolates from humans.9, 17 In our study, 3 of 4 isolates (2 R piperina and 1 R argillacea) had low MICs to itraconazole, which contrasts with isolates from humans. It has been reported that variability in itraconazole susceptibility may be the result of cryptic R argillacea complex species.9 Similar to previous reports, all isolates in our study had low amphotericin B MICs. Although determining the best treatment for dogs without species‐specific clinical breakpoints is challenging, in vitro susceptibility testing might be helpful in excluding treatments that are likely to be ineffective. This approach generally would advise against the use of voriconazole for use in dogs with Rasamsonia infections.14 However, correlations between in vitro susceptibility against Rasamsonia spp. and clinical outcomes have not been established.

Both R piperina and C albicans were isolated from necropsy specimens from 1 dog in our study. The clinical relevance of this finding is not known. Although contamination could have occurred during necropsy, this dog also could have been infected with both fungi. If so, immunodeficiency predisposing these dogs to Rasamsonia infections also might predispose them to other disseminated fungal infections, similar to what has been reported in humans with invasive Rasamsonia infections.10

As a consequence of its retrospective design, our study cannot inform treatment guidelines because treatments were neither controlled nor standardized. Although most dogs underwent rigorous and comprehensive clinical evaluations, the diagnostic evaluation received by dogs was at the discretion of the attending clinician. In addition, reliable conclusions regarding differences in survival time between groups cannot be made, but the survival times of dogs in our study were similar to those of dogs in individual case reports.7, 11, 13

In conclusion, Rasamsonia infection is an important differential diagnosis for dogs with disseminated fungal infections, especially German Shepherd dogs. Dogs with disseminated R argillacea species complex infections often share clinical, radiographic, and immunologic testing similarities with dogs with disseminated aspergillosis and standard fungal culture techniques often misidentify the fungus as Paecilomyces spp. Molecular testing is required to ensure accurate organism identification and help guide optimal antifungal treatment. Although prognosis is routinely poor, survival might be prolonged using species identification and medical treatment based on fungal susceptibility testing.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DECLARATION

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

OFF‐LABEL ANTIMICROBIAL DECLARATION

Amphotericin B, caspofungin, itraconazole, micafungin, posaconazole, and voriconazole were used off‐label.

INSTITUTIONAL ANIMAL CARE AND USE COMMITTEE (IACUC) OR OTHER APPROVAL DECLARATION

Authors declare no IACUC or other approval was needed.

HUMAN ETHICS APPROVAL DECLARATION

Authors declare human ethics approval was not needed for this study.

Supporting information

Table S1 Summary of signalment, cytology, histopathology, microbiology, and immunology results and testing in 8 dogs with Rasamsonia spp. infections. R piperina was isolated from dogs marked by * and R argillacea was isolated from dogs marked by #. Any organ with identifiable fungal organisms at necropsy is listed.

Table S2 DNA targets and sequence homology for isolates from 8 dogs with Rasamsonia argillacea species complex infections.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

No funding was received for this study.

Dear JD, Reagan KL, Hulsebosch SE, et al. Disseminated Rasamsonia argillacea species complex infections in 8 dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2021;35(5):2232‐2240. 10.1111/jvim.16244

REFERENCES

- 1.Day MJ, Eger CE, Shaw SE, Penhale WJ. Immunologic study of systemic aspergillosis in German Shepherd dogs. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1985;9:335‐347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schultz RM, Johnson EG, Wisner ER, Brown NA, Byrne BA, Sykes JE. Clinicopathologic and diagnostic imaging characteristics of systemic aspergillosis in 30 dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2008;22:851‐859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Langlois DK, Sutton DA, Swenson CL, et al. Clinical, morphological, and molecular characterization of Penicillium canis sp. nov., isolated from a dog with osteomyelitis. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:2447‐2453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Okada K, Kano R, Hasegawa T, Kagawa Y. Granulomatous polyarthritis caused by Talaromyces georgiensis in a dog. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2020;32:912‐917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whipple KM, Shmalberg JW, Joyce AC, Beatty SS. Cytologic identification of fungal arthritis in a Labrador Retriever with disseminated Talaromyces helicus infection. Vet Clin Pathol. 2019;48:449‐454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tappin SW, Ferrandis I, Jakovljevic S, Villiers E, White RAS. Successful treatment of bilateral Paecilomyces pyelonephritis in a German Shepherd dog. J Small Anim Pract. 2012;53:657‐660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawalilak LT, Chen AV, Roberts GR. Imaging characteristics of disseminated Geosmithia argillacea causing severe diskospondylitis and meningoencephalomyelitis in a dog. Clin Case Rep. 2015;3:901‐906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Houbraken J, Spierenburg H, Frisvad JC. Rasamsonia, a new genus comprising thermotolerant and thermophilic Talaromyces and Geosmithia species. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2012;101:403‐421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Houbraken J, Giraud S, Meijer M, et al. Taxonomy and antifungal susceptibility of clinically important Rasamsonia species. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:22‐30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stemler J, Salmanton‐Garcia J, Seidel D, et al. Risk factors and mortality in invasive Rasamsonia spp. infection: analysis of cases in the FungiScope® registry and from the literature. Mycoses. 2020;63:265‐274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salguero R, Borman AM, Herrtage M, et al. Rasamsonia argillacea mycosis in a dog: first case in Europe. Vet Rec. 2013;172:581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lodzinska J, Cazzini P, Taylor CS, et al. Systemic Rasamsonia piperina infection in a German Shepherd cross dog. JMM Case Rep. 2017;4:e005125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grant DC, Sutton DA, Sandberg CA, et al. Disseminated Geosmithia argillacea infection in a German Shepherd dog. Med Mycol. 2009;47:221‐226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borman AM, Fraser M, Palmer MD, et al. MIC distributions and evaluation of fungicidal activity for amphotericin B, itraconazole, voriconazole, posaconazole and caspofungin and 20 species of pathogenic filamentous fungi determined using the CLSI broth microdilution method. J Fungi (Basel). 2017;3:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giraud S, Pihet M, Razafimandimby B, et al. Geosmithia argillacea: an emerging pathogen in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:2381‐2386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcia RS, Wheat LJ, Cook AK, Kirsch EJ, Sykes JE. Sensitivity and specificity of a blood and urine galactomannan antigen assay for diagnosis of systemic aspergillosis in dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2012;26:911‐919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abdolrasouli A, Bercusson AC, Rhodes JL, et al. Airway persistence by the emerging multi‐azole‐resistant Rasamsonia argillacea complex in cystic fibrosis. Mycoses. 2018;61:665‐673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Houbraken J, Verweij PE, Rijs AJ, et al. Identification of Paecilomyces variotii in clinical samples and settings. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:2754‐2761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barton RC, Borman AM, Johnson EM, et al. Isolation of the fungus Geosmithia argillacea in sputum of people with cystic fibrosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:2615‐2617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoenigl M, Seeber K, Koidl C, et al. Sensitivity of galactomannan enzyme immunoassay for diagnosing breakthrough invasive aspergillosis under antifungal prophylaxis and empirical therapy. Mycoses. 2013;56:471‐476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Summary of signalment, cytology, histopathology, microbiology, and immunology results and testing in 8 dogs with Rasamsonia spp. infections. R piperina was isolated from dogs marked by * and R argillacea was isolated from dogs marked by #. Any organ with identifiable fungal organisms at necropsy is listed.

Table S2 DNA targets and sequence homology for isolates from 8 dogs with Rasamsonia argillacea species complex infections.