Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Keywords: aspirin; clopidogrel; ischemic attack, transient; risk; secondary prevention

Background and Purpose:

Lifelong treatment with antiplatelet drugs is recommended following a transient ischemic attack or ischemic stroke. Bleeding complications may offset the benefit of antiplatelet drugs in patients at increased risk of bleeding and low risk of recurrent ischemic events. We aimed to investigate the net benefit of antiplatelet treatment according to an individuals’ bleeding risk.

Methods:

We pooled individual patient data from 6 randomized clinical trials (CAPRIE [Clopidogrel Versus Aspirin in Patients at Risk of Ischemic Events], ESPS-2 [European Stroke Prevention Study-2], MATCH [Management of Atherothrombosis With Clopidogrel in High-Risk Patients], CHARISMA [Clopidogrel for High Atherothrombotic Risk and Ischemic Stabilization, Management, and Avoidance], ESPRIT [European/Australasian Stroke Prevention in Reversible Ischemia Trial], and PRoFESS [Prevention Regimen for Effectively Avoiding Second Strokes]) investigating antiplatelet therapy in the subacute or chronic phase after noncardioembolic transient ischemic attack or stroke. Patients were stratified into quintiles according to their predicted risk of major bleeding with the S2TOP-BLEED score. The annual risk of major bleeding and recurrent ischemic events was assessed per quintile for 4 scenarios: (1) aspirin monotherapy, (2) aspirin-clopidogrel versus aspirin or clopidogrel monotherapy, (3) aspirin-dipyridamole versus clopidogrel, and (4) aspirin versus clopidogrel. Net benefit was calculated for the second, third, and fourth scenario.

Results:

Thirty seven thousand eighty-seven patients were included in the analyses. Both risk of major bleeding and recurrent ischemic events increased over quintiles of predicted bleeding risk, but risk of ischemic events was consistently higher (eg, from 0.7%/y (bottom quintile) to 3.2%/y (top quintile) for major bleeding on aspirin and from 2.5%/y to 10.2%/y for risk of ischemic events on aspirin). Treatment with aspirin-clopidogrel led to more major bleedings (0.9%–1.7% per year), than reduction in ischemic events (ranging from 0.4% to 0.9/1.0% per year) across all quintiles. There was no clear preference for either aspirin-dipyridamole or clopidogrel according to baseline bleeding risk.

Conclusions:

Among patients with a transient ischemic attack or ischemic stroke included in clinical trials of antiplatelet therapy, the risk of recurrent ischemic events and of major bleeding increase in parallel. Antiplatelet treatment cannot be individualized solely based on bleeding risk assessment.

Life-long treatment with antiplatelet drugs is recommended following a TIA or noncardioembolic ischemic stroke.1 Aspirin, aspirin in combination with dipyridamole, and clopidogrel alone are currently recommended as first-line agents in secondary prevention of noncardioembolic stroke1 and reduce the risk of recurrent ischemic events by about 20% to 25% compared with placebo or no therapy.2,3 Despite treatment, the residual risk of a recurrent ischemic event is substantial, ≈5% per year.4,5 To further reduce the risk of vascular events the benefits of adding an extra antiplatelet drug have been investigated; some trials observed a small reduction in risk of recurrent ischemic events during the use of aspirin-clopidogrel, but at the cost of a significantly increased bleeding risk.6–9

For currently recommended antiplatelet regimens, the reduction in ischemic events is, on average, larger than the increase in major bleeds.3,10 However, for an individual patient, the balance between benefits and risks may differ, due to variations in the underlying absolute risk of a major bleed,11 or recurrent ischemic event.4 Bleeding complications may offset the benefit of antiplatelet drugs in patients at increased risk of bleeding and low risk of recurrent ischemic events.

Prognostic models may be used to stratify trial populations and explore the effect of variation in absolute risk on the benefit and risk from treatment.12,13 In the current study, we aimed to investigate the balance between benefits and risks of long-term antiplatelet treatment according to an individual’s bleeding risk.

Methods

Data Availability Statement

Request for anonymized data will be considered by the Cerebrovascular Antiplatelet Trialists Collaboration.

Study Population

We pooled individual patient data from 6 randomized clinical trials that investigated efficacy and safety of antiplatelet treatment in long-term secondary prevention after a TIA or noncardioembolic ischemic stroke.7,8,14–17 The design of the individual patient data meta-analysis has been described in detail elsewhere.18 Briefly, we performed a literature search to identify trials that randomized antiplatelet therapy in the subacute or chronic phase after a noncardioembolic TIA or stroke. Trials were eligible if they randomized patients with a TIA or noncardioembolic ischemic stroke to aspirin, or to antiplatelet drugs that are recommended as first-line treatment in secondary prevention of stroke as an alternative or in addition to aspirin, and had a duration of at least 1 year. Six trials met the inclusion criteria (CAPRIE [Clopidogrel Versus Aspirin in Patients at Risk of Ischemic Events], ESPS-2 [European Stroke Prevention Study-2], MATCH [Management of Atherothrombosis With Clopidogrel in High-Risk Patients], CHARISMA [Clopidogrel for High Atherothrombotic Risk and Ischemic Stabilization, Management, and Avoidance], ESPRIT [European/Australasian Stroke Prevention in Reversible Ischemia Trial], and PRoFESS [Prevention Regimen for Effectively Avoiding Second Strokes], including 48 023 patients with a TIA or ischemic stroke between 1989 and 2006.18 Details of studies included in the IPD meta-analysis (recruitment period, details of antiplatelet regimens, inclusion criteria, sample size) are presented in Table 1. For the current analysis, we excluded patients with a possible cardioembolic origin of their stroke (patients with a history of atrial fibrillation or TOAST [Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment] classification of cardioembolic stroke) and patients randomized to dipyridamole only or placebo. Patients were followed up at regular intervals according to the trial protocols. Median follow-up ranged from 1.4 to 3.5 years. The trials were approved by the ethics committee or institutional review board at each participating center and all patients gave written informed consent.

Table 1.

Details of 6 Trials Included in the IPD Meta-Analysis

The outcome of interest for benefit of antiplatelet treatment was a recurrent ischemic event, defined as a recurrent ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, or vascular death from nonhemorrhagic cause. For evaluating harms of antiplatelet treatment we focused on major bleeding. Trial specific definitions for major bleeding were used (Table I in the Data Supplement). Major bleeds included bleeds that were fatal, intracranial, significantly disabling, or requiring hospital admission. Hemorrhagic strokes were counted as major bleedings, not as recurrent strokes. Hemorrhagic transformations of ischemic strokes were counted as ischemic strokes.

Statistical Analysis

We calculated predicted risk of major bleeding for each patient with the S2TOP-BLEED score.19 This score comprises ten variables (age, sex, smoking, modified Rankin Scale score, hypertension, diabetes, prior stroke, Asian ethnicity, BMI, and type of antiplatelet treatment; Table II in the Data Supplement) and was derived from the same individual patient data. External validation of the score in a trial cohort and population based cohort confirmed the robustness of the model.19,20 Seven thousand nine hundred thirty-one patients (18%) had missing values on one of the items of the S2TOP-BLEED score, almost entirely due to the fact that 2 variables (modified Rankin Scale score and body mass index) were not measured in one trial each. For the development of the score, multiple imputation was performed. For the current analysis, we used a single imputed dataset. In the present study, we did not assign points for type of antiplatelet treatment as we were interested in the effect of this treatment.

We investigated benefits and risks of antiplatelet treatment for 4 different scenarios that we considered most relevant for clinical practice: (1) aspirin monotherapy, (2) enhanced dual antiplatelet therapy (aspirin-clopidogrel) versus monotherapy to assess if a specific subgroup might benefit from long-term dual therapy, (3) aspirin-dipyridamole versus clopidogrel, and (4) aspirin versus clopidogrel, to assess whether there is a preference for one of these guideline recommended treatments depending on the absolute bleeding risk.

For the first scenario, we pooled data from patients randomized to aspirin (aspirin arm from CAPRIE, ESPS-2, CHARISMA, and ESPRIT trials, n=8127). For the second scenario, we combined data from MATCH and CHARISMA trials (n=11 492). Patients randomized to either aspirin or clopidogrel were pooled in a monotherapy group and compared with the dual therapy group comprising those randomized to aspirin-clopidogrel. For the third scenario, we used data from the PRoFESS trial (n=19 589), comparing aspirin-dipyridamole with clopidogrel. For the last scenario, we studied patients included in the CAPRIE trial (n=6201), comparing aspirin with clopidogrel. All analyses were performed according to the intention-to-treat principle. Patients were censored at the time of a major bleed or recurrent ischemic event (depending on the outcome of interest), death or end of follow-up.

Patients were divided into quintiles according to their predicted risk of major bleeding. For each quintile, the annual rate of major bleeding and recurrent ischemic events was calculated (number of events/person-years at risk×100) per trial and subsequently pooled with random effects meta-analysis. The absolute rate difference was calculated for each treatment contrast. Next, we calculated the net benefit for the second, third and fourth scenario with the following formula: (Risk of ischemic event [with treatment A]−Risk of ischemic event [with treatment B])−(Risk of major bleeding [with treatment B]−Risk of major bleeding [with treatment A]). A positive net benefit indicates that the benefits of treatment B outweigh the risks.

A major bleed may be deemed less severe than a recurrent ischemic stroke; therefore, we performed a sensitivity analysis including only intracranial hemorrhages instead of all major bleedings. Intracranial hemorrhages were assigned a weight of 1.5 to account for their generally worse outcome.

The same analyses were performed stratified for risk of a recurrent ischemic event, for which we used the Essen Stroke Risk Score (ESRS), originally derived from the CAPRIE data.21 The score consists of 9 variables (age, hypertension, diabetes, previous myocardial infarction, other cardiovascular disease, peripheral arterial disease, smoking, prior TIA, or ischemic stroke in addition to qualifying event) and ranges from 0 to 9 points (Table III in the Data Supplement). This score was chosen among other scores predicting recurrent vascular events because all predictors required to calculate the score were available and it showed reasonable performance (Figure I in the Data Supplement). Instead of dividing patients into quintiles we performed the analyses per Essen Stroke Risk Score, combining all patients with a score of 5 or higher. All analyses were performed with R version 3.3.2.

Results

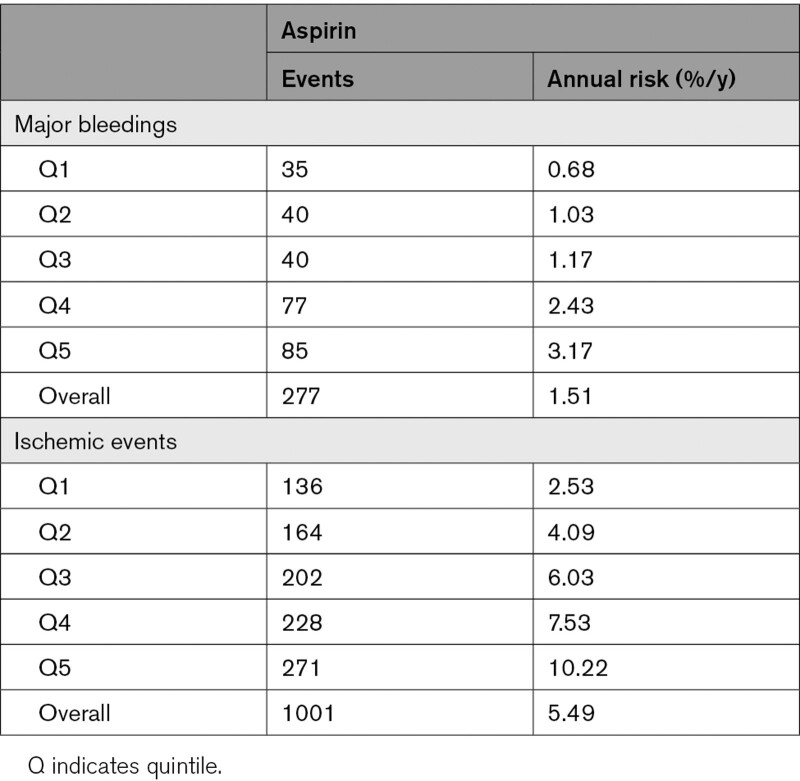

Aspirin

We studied 8127 patients randomized to aspirin. During 17 538 person-years of follow-up, 1001 patients had a recurrent ischemic event and 277 patients had a major bleed. The annual rate of recurrent ischemic events increased across bleeding risk quintiles from 2.5% to 10.2%, as did the annual rate of major bleeding (0.7%–3.2%; Figure 1, Table 2). Across all risk groups, the absolute risk of an ischemic event was higher than the risk of a major bleeding. The benefit of aspirin was more pronounced when only intracranial hemorrhages were taken into account instead of all major bleeds (Figure II in the Data Supplement).

Figure 1.

Risk of major bleeding and recurrent ischemic events on aspirin monotherapy, according to bleeding risk groups. A indicates aspirin.

Table 2.

Absolute Annual Risk of Major Bleeding and Recurrent Ischemic Events on Aspirin According to Bleeding Risk Quintile

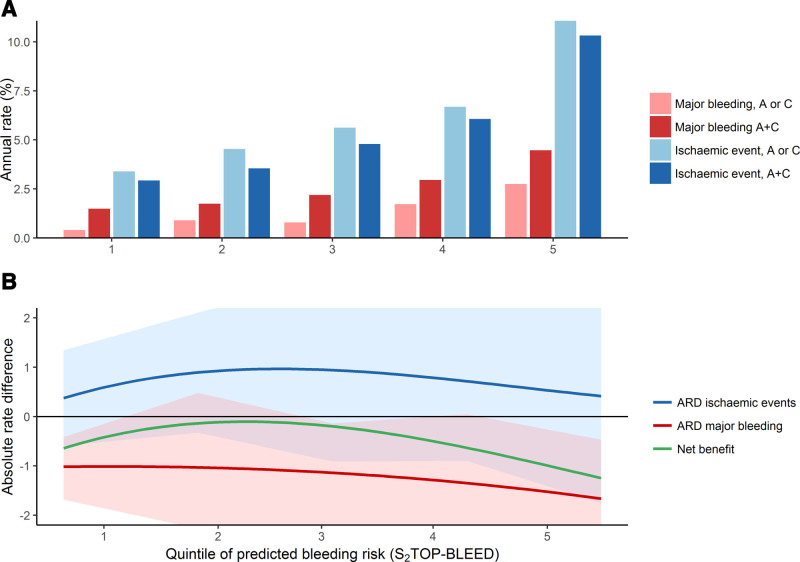

Aspirin-Clopidogrel Versus Monotherapy Aspirin or Clopidogrel

Eleven thousand four hundred ninety-two patients contributed to the analysis comparing aspirin-clopidogrel dual therapy with aspirin or clopidogrel monotherapy. A recurrent ischemic event occurred in 613 patients randomized to monotherapy and in 548 randomized to aspirin-clopidogrel. A major bleed occurred in 126 patients on monotherapy and in 246 patients on aspirin-clopidogrel. The risk of major bleeding and recurrent ischemic events increased simultaneously across the quintiles (Table 3; Figure 2A). The risk reduction of ischemic events with aspirin-clopidogrel (ranging from 0.4% to 0.9/1.0% per year across quintiles) did not outweigh the risk increase of major bleedings in any of the quintiles (0.9%–1.7% per year, Table 3, Figure 2B). The net clinical benefit of aspirin-clopidogrel was positive in the lowest 3 quintiles when only intracranial hemorrhages were taken into account (Figure III in the Data Supplement).

Table 3.

Absolute Annual Risks and Risk Differences for Aspirin+Clopidogrel Versus Aspirin or Clopidogrel Monotherapy

Figure 2.

Net benefit of aspirin-clopidogrel vs aspirin or clopidogrel monotherapy according to bleeding risk group. Shaded areas indicate 95% CI. A indicates aspirin; A+C, aspirin-clopidogrel; ARD, absolute rate difference; and C clopidogrel.

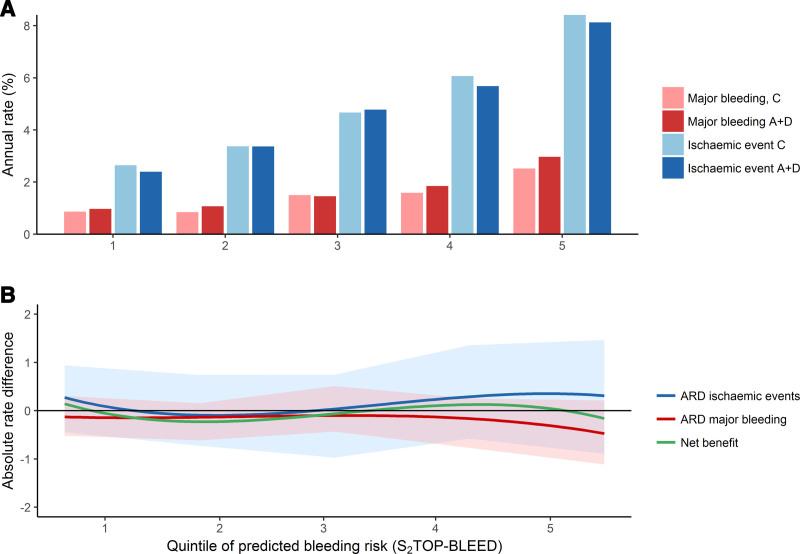

Aspirin-Dipyridamole Versus Clopidogrel

For the analysis comparing aspirin-dipyridamole with clopidogrel, we analyzed data from 19 589 patients included in the PRoFESS trial. Among patients randomized to aspirin-dipyridamole, 1146 had a recurrent ischemic event and 403 had a major bleed. Among patients randomized to clopidogrel, 1173 patients had a recurrent ischemic event and 354 had a major bleed. There was no clear preference for either of the 2 treatments according to bleeding risk group when all major bleeds were taken into account (Figure 3, Table IV in the Data Supplement), or when only intracranial hemorrhages were taken into account (Figure IV in the Data Supplement).

Figure 3.

Net benefit of aspirin-dipyridamole compared with clopidogrel according to bleeding risk group. Shaded areas indicate 95% CI. A+D indicates aspirin-dipyridamole; ARD, absolute rate difference; and C, clopidogrel.

Aspirin Versus Clopidogrel

Six thousand two hundred one patients contributed to the analysis of aspirin versus clopidogrel. Among patients randomized to aspirin 105 had a major bleed and 432 a recurrent ischemic event. Among patients on clopidogrel 81 had a major bleed and 411 a recurrent ischemic event (Table V in the Data Supplement). The annual rate of major bleeding was lower for patients on clopidogrel than aspirin (0.6%–3.1% per year for clopidogrel, and 0.8%–3.2% for aspirin), except for the second quintile (Table V in the Data Supplement). The risk of ischemic events was lower with clopidogrel in the lowest 3 quintiles (3.3%–6.7% versus 4.3%–7.6%) Overall, the net benefit was positive for clopidogrel compared with aspirin in the lowest 4 quintiles (Figure V in the Data Supplement).

Results for all 4 scenarios were largely similar when patients were stratified with the Essen Stroke Risk Score according to their risk of a recurrent ischemic event (Figures VII through X in the Data Supplement). If we excluded patients randomized within 21 days after the index event, results were essentially similar, but estimates became substantially more imprecise.

Discussion

We observed that the risk of major bleeding and the risk of recurrent ischemic events increased in parallel across bleeding risk groups in long-term secondary prevention after a TIA or minor ischemic stroke, among patient populations eligible and included in randomized clinical trials of antiplatelet therapy. The benefits of aspirin monotherapy appeared to outweigh the risks, irrespective of baseline bleeding risk. We demonstrated that the risk of major bleeding associated with aggressive long-term dual antiplatelet therapy was larger than the benefit for all risk groups. No preference was observed for either aspirin-dipyridamole or clopidogrel according to baseline bleeding risk, in a population of trial participants.

Early trials that compared aspirin with placebo suggested that the risk of bleeding on low-dose aspirin was relatively small and that the case fatality was low.22,23 However, a recent population-based study has drawn attention to the substantial risks associated with long-term aspirin use in elderly patients.11 The incidence of major bleeds (mostly gastrointestinal bleeds) increased steeply with age, reaching an annualized rate of 4% in patients over 85 years. Also, the case fatality and disability associated with bleeds increased in elderly patients.11 These findings raised concern about the net benefit of long-term aspirin when the risk of adverse events is substantial. Indeed, in the very elderly patients (>85 years) it was observed that the risk reduction in ischemic events was approximately similar to the increase in major bleeds attributable to aspirin.11 In our study, we did not observe a clear change in benefit with increasing risk of bleeding. Although in absolute terms the harms increased, the benefits also increased due to simultaneously rising risk of ischemic events. A possible explanation for the discrepancy with the previously mentioned study is that patients at highest risk of bleeding were excluded from the trial cohorts, and the very elderly (>85 years) and frail patients in whom the net benefit might change were relatively underrepresented.

Among patients with coronary artery disease, trials found benefit of adding clopidogrel to standard treatment (mainly aspirin), with an acceptable increase in risk of major bleedings.24,25 A similar approach was investigated in patients with stroke but did not yield a comparable benefit without significantly increasing harm when clopidogrel was initiated in the subacute or chronic phase and continued for 1.5 to 2 years.7–9 In the present study, we could not identify a subgroup according to risk of bleeding in whom the benefits of long-term aspirin-clopidogrel would outweigh the risks. The results of the POINT (Platelet-Oriented Inhibition in New TIA and Minor Ischemic Stroke) and CHANCE (Clopidogrel in High-Risk Patients With Acute Nondisabling Cerebrovascular Events) trials suggest that aspirin-clopidogrel is beneficial when initiated early after stroke (within 12 or 6 hours, respectively) and continued for the first 21 to 90 days, among patients with a TIA or minor stroke (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score <4).26,27 In the current study we could not address the balance between benefits and risks in the very early phase, as patients were generally randomized after the acute phase of TIA or stroke (median time from qualifying event to randomization 21 days (interquartile range 9-57 days)).

A network meta-analysis on individual patient data has shown that on average, clopidogrel is slightly more effective than aspirin in preventing serious vascular events (RR, 0.88 [0.78–0.98]) and causes less major bleedings (RR, 0.76 [0.63–0.91]).10 Our study shows that the effect of treatment (aspirin versus clopidogrel) is not altered by bleeding risk group, although the estimates became less precise due to the small number of patients per subgroup. The American Stroke Association guideline states that the choice of antiplatelet treatment should be based on individual characteristics, next to considerations on efficacy, safety, and costs.1 Aspirin-dipyridamole and clopidogrel have comparable efficacy and safety profiles, but our results suggest that it is unlikely that patient characteristics will further guide the choice for either of these 2 treatments. It is difficult to distinguish patients based on their risk of recurrent ischemic events and major bleedings, because the risk factors underlying both major bleedings and recurrent ischemic events are very similar.28 A disadvantage of aspirin-dipyridamole is the high number of patients reporting headache as side effect, as well as the fact that it should be taken twice daily, which may negatively impact on compliance. Our results show that high predicted bleeding risk should not serve as criterion to withhold antiplatelet treatment. Nevertheless, bleeding risk assessment may still be useful to identify modifiable risk factors for bleeding (eg, hypertension) and to identify patients in whom preventive strategies should be implemented. Co-prescription of a proton pump inhibitor may be considered in patients with a high estimated bleeding risk as it substantially reduces risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding.11,29 Age above 75 years has recently been suggested as criterion to start proton pump inhibitors, with a number needed to treat of 23 to prevent 1 major bleeding at 5 years follow-up.11 Age above 75 years would correspond with an annual risk of major bleeding of >2%.

Strengths of our study include the large sample size and the high quality of the data, with thorough follow-up. Also, the outcome events were adjudicated centrally by an independent committee. Some limitations need to be addressed. First, our study population may not be representative of all patients with a TIA or ischemic stroke, as patients with the highest bleeding risk and advanced age have been excluded from the trials. The balance between benefits and risks may differ for frail and very elderly patients, as was suggested in a recent population-based cohort study.11 Second, the S2TOP-BLEED score that was used to stratify patients in risk groups was derived from the same individual patient data. However, previous external validation studies have shown that the score is robust.19,20 Third, there was some heterogeneity in bleeding risk across trials, likely due to differences in inclusion criteria, treatment(dose), and definition of outcome. We accounted for this by performing random effects meta-analyses. Fourth, we could not assign weights to the different types of major bleeding based on the available data, while the severity and consequences of bleeds differ. Fifth, we did not have data on the very early phase following a TIA or stroke and could therefore not address the benefit and risk of short-term aspirin-clopidogrel. Sixth, we could not investigate the influence of stroke subtype (eg, large artery atherosclerosis versus small vessel disease) on the balance between benefits and risks of antiplatelet treatment, as these data were collected in too few patients.

In conclusion, we showed that the risk of recurrent ischemic events and major bleedings increase in parallel in patients with a TIA or ischemic stroke included in clinical trials on antiplatelet treatment. Bleeding risk assessment based on patient characteristics cannot be used as single element to guide decision on long-term antiplatelet treatment for individual patients. To meaningfully inform treatment decisions for antiplatelet treatment, stronger predictors for major bleeding and ischemia need to be identified.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sanofi-Aventis and Bristol-Myers Squibb for giving access to the databases of CAPRIE (Clopidogrel Versus Aspirin in Patients at Risk of Ischemic Events), MATCH (Management of Atherothrombosis With Clopidogrel in High-Risk Patients), and CHARISMA (Clopidogrel for High Atherothrombotic Risk and Ischemic Stabilization, Management, and Avoidance). We thank the ESPRIT (European/Australasian Stroke Prevention in Reversible Ischemia Trial) Steering Committee for providing access to the ESPRIT data. Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc supported this work by providing access to the clinical trial databases of ESPS2 (European Stroke Prevention Study-2) and PRoFESS (Prevention Regimen for Effectively Avoiding Second Strokes).

Sources of Funding

Drs Greving and Hilkens are supported by a grant from the Dutch Heart Foundation (grant number 2013T128). Dr Greving is also supported by a VENI grant from the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw), grant number 916.11.129.

Disclosures

P.M. Bath reports personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim and personal fees from Sanofi during the conduct of the study; personal fees from DiaMedica, personal fees from Moleac, and personal fees from Phagenesis outside the submitted work. Dr Diener received honoraria for participation in clinical trials, contribution to advisory boards, or oral presentations from Abbott, Allergan, AstraZeneca, Bayer Vital, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi-Sankyo, Johnson & Johnson, MSD, Medtronic, Novartis, Pfizer, Portola, Sanofi-Aventis, Servier, St. Jude, and WebMD. Dr Diener has no ownership interest and does not own stocks of any pharmaceutical company. Dr Diener does not own stocks of any pharmaceutical company. Dr Diener received research grants from the German Research Council, German Ministry of Education and Research, European Union, National Institutes of Health, Bertelsmann Foundation and Heinz-Nixdorf Foundation. Dr Leys reports personal fees from Wiley (Editor), grants from European Stroke Organisation, and grants from Pfizer outside the submitted work. Dr Sacco reports grants, personal fees, and other from Boehringer Ingelheim during the conduct of the study; grants from National Institutes of Health and grants from FL DOH outside the submitted work.

Supplemental Materials

Online Tables I–V

Online Figures I–X

Supplementary Material

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- CAPRIE

- Clopidogrel Versus Aspirin in Patients at Risk of Ischemic Events

- CHARISMA

- Clopidogrel for High Atherothrombotic Risk and Ischemic Stabilization, Management, and Avoidance

- ESPRIT

- European/Australasian Stroke Prevention in Reversible Ischemia Trial

- ESPS-2

- European Stroke Prevention Study-2

- ESRS

- Essen Stroke Risk Score

- MATCH

- Management of Atherothrombosis With Clopidogrel in High-Risk Patients

- PRoFESS

- Prevention Regimen for Effectively Avoiding Second Strokes

- TIA

- transient ischemic attack

- TOAST

- Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment

This manuscript was sent to Scott E. Kasner, Guest Editor, for review by expert referees, editorial decision, and final disposition.

The Data Supplement is available with this article at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.031755.

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 3264–3265.

Contributor Information

Nina A. Hilkens, Email: nina.hilkens@radboudumc.nl.

Ale Algra, Email: a.algra@umcutrecht.nl.

Hans Christoph Diener, Email: h.diener@uni-essen.de.

Philip M. Bath, Email: philip.bath@nottingham.ac.uk.

László Csiba, Email: csiba@med.unideb.hu.

Werner Hacke, Email: werner.hacke@med.uni-heidelberg.de.

L. Jaap Kappelle, Email: l.kappelle@umcutrecht.nl.

Peter J. Koudstaal, Email: p.j.koudstaal@erasmusmc.nl.

Didier Leys, Email: didier.leys@univ-lille.fr.

Jean-Louis Mas, Email: jl.mas@ghu-paris.fr.

Ralph L. Sacco, Email: rsacco@med.miami.edu.

References

- 1.Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, Bravata DM, Chimowitz MI, Ezekowitz MD, Fang MC, Fisher M, Furie KL, Heck DV, et al. ; American Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014; 45:2160–2236. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antithrombotic Trialists' Collaboration. Collaborative meta-analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. Bmj. 2002; 324:71–86. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7329.71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baigent C, Blackwell L, Collins R, Emberson J, Godwin J, Peto R, Buring J, Hennekens C, Kearney P, Meade T, et al. Aspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2009; 373:1849–1860. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60503-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Wijk I, Kappelle LJ, van Gijn J, Koudstaal PJ, Franke CL, Vermeulen M, Gorter JW, Algra A; LiLAC Study Group. Long-term survival and vascular event risk after transient ischaemic attack or minor ischaemic stroke: a cohort study. Lancet. 2005; 365:2098–2104. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66734-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amarenco P, Lavallée PC, Labreuche J, Albers GW, Bornstein NM, Canhão P, Caplan LR, Donnan GA, Ferro JM, Hennerici MG, et al. ; TIAregistry.org Investigators. One-year risk of stroke after transient ischemic attack or minor stroke. N Engl J Med. 2016; 374:1533–1542. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bath PM, Woodhouse LJ, Appleton JP, Beridze M, Christensen H, Dineen RA, Duley L, England TJ, Flaherty K, Havard D, et al. ; TARDIS Investigators. Antiplatelet therapy with aspirin, clopidogrel, and dipyridamole versus clopidogrel alone or aspirin and dipyridamole in patients with acute cerebral ischaemia (TARDIS): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 superiority trial. Lancet. 2018; 391:850–859. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32849-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diener HC, Bogousslavsky J, Brass LM, Cimminiello C, Csiba L, Kaste M, Leys D, Matias-Guiu J, Rupprecht HJ; MATCH Investigators. Aspirin and clopidogrel compared with clopidogrel alone after recent ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack in high-risk patients (MATCH): randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004; 364:331–337. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16721-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhatt DL, Fox KA, Hacke W, Berger PB, Black HR, Boden WE, Cacoub P, Cohen EA, Creager MA, Easton JD, et al. ; CHARISMA Investigators. Clopidogrel and aspirin versus aspirin alone for the prevention of atherothrombotic events. N Engl J Med. 2006; 354:1706–1717. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benavente OR, Hart RG, McClure LA, Szychowski JM, Coffey CS, Pearce LA. Effects of clopidogrel added to aspirin in patients with recent lacunar stroke. N Engl J Med. 2012; 367:817–825. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1204133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greving JP, Diener HC, Reitsma JB, Bath PM, Csiba L, Hacke W, Kappelle LJ, Koudstaal PJ, Leys D, Mas JL, et al. Antiplatelet therapy after noncardioembolic stroke. Stroke. 2019; 50:1812–1818. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.024497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li L, Geraghty OC, Mehta Z, Rothwell PM; Oxford Vascular Study. Age-specific risks, severity, time course, and outcome of bleeding on long-term antiplatelet treatment after vascular events: a population-based cohort study. Lancet. 2017; 390:490–499. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30770-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rothwell PM, Mehta Z, Howard SC, Gutnikov SA, Warlow CP. Treating individuals 3: from subgroups to individuals: general principles and the example of carotid endarterectomy. Lancet. 2005; 365:256–265. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17746-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kent DM, Rothwell PM, Ioannidis JP, Altman DG, Hayward RA. Assessing and reporting heterogeneity in treatment effects in clinical trials: a proposal. Trials. 2010; 11:85. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-11-85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caprie steering committee. A randomised, blinded, trial of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients at risk of ischaemic events (caprie). Lancet. 1996; 348:1329–1339. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)09457-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halkes PH, van Gijn J, Kappelle LJ, Koudstaal PJ, Algra A. Aspirin plus dipyridamole versus aspirin alone after cerebral ischaemia of arterial origin (esprit): Randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006; 367:1665–1673. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68734-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diener HC, Cunha L, Forbes C, Sivenius J, Smets P, Lowenthal A. European stroke prevention study. 2. Dipyridamole and acetylsalicylic acid in the secondary prevention of stroke. J Neurol Sci. 1996; 143:1–13. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(96)00308-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sacco RL, Diener HC, Yusuf S, Cotton D, Ounpuu S, Lawton WA, Palesch Y, Martin RH, Albers GW, Bath P, et al. ; PRoFESS Study Group. Aspirin and extended-release dipyridamole versus clopidogrel for recurrent stroke. N Engl J Med. 2008; 359:1238–1251. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greving JP, Diener HC, Csiba L, Hacke W, Kappelle LJ, Koudstaal PJ, Leys D, Mas JL, Sacco RL, Sivenius J, et al. ; Cerebrovascular Antiplatelet Trialists’ Collaborative Group. Individual patient data meta-analysis of antiplatelet regimens after noncardioembolic stroke or TIA: rationale and design. Int J Stroke. 201510 Suppl A100145–150. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hilkens NA, Algra A, Diener HC, Reitsma JB, Bath PM, Csiba L, Hacke W, Kappelle LJ, Koudstaal PJ, Leys D, et al. ; Cerebrovascular Antiplatelet Trialists’ Collaborative Group. Predicting major bleeding in patients with noncardioembolic stroke on antiplatelets: S2TOP-BLEED. Neurology. 2017; 89:936–943. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hilkens NA, Li L, Rothwell PM, Algra A, Greving JP. External validation of risk scores for major bleeding in a population-based cohort of transient ischemic attack and ischemic stroke patients. Stroke. 2018; 49:601–606. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.019259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diener HC, Ringleb PA, Savi P. Clopidogrel for the secondary prevention of stroke. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2005; 6:755–764. doi: 10.1517/14656566.6.5.755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Gijn J, Algra A, Kappelle J, Koudstaal PJ, van Latum A. A comparison of two doses of aspirin (30 mg vs. 283 mg a day) in patients after a transient ischemic attack or minor ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 1991; 325:1261–1266. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110313251801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farrell B, Godwin J, Richards S, Warlow C. The United Kingdom transient ischaemic attack (UK-TIA) aspirin trial: final results. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1991; 54:1044–1054. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.54.12.1044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yusuf S, Zhao F, Mehta SR, Chrolavicius S, Tognoni G, Fox KK; Clopidogrel in Unstable Angina to Prevent Recurrent Events Trial Investigators. Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med. 2001; 345:494–502. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steinhubl SR, Berger PB, Mann JT, 3rd, Fry ET, DeLago A, Wilmer C, Topol EJ; CREDO Investigators. Clopidogrel for the Reduction of Events During Observation. Early and sustained dual oral antiplatelet therapy following percutaneous coronary intervention: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002; 288:2411–2420. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.19.2411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang Y, Wang Y, Zhao X, Liu L, Wang D, Wang C, Wang C, Li H, Meng X, Cui L, et al. ; CHANCE Investigators. Clopidogrel with aspirin in acute minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2013; 369:11–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnston SC, Easton JD, Farrant M, Barsan W, Conwit RA, Elm JJ, Kim AS, Lindblad AS, Palesch YY; Clinical Research Collaboration, Neurological Emergencies Treatment Trials Network, and the POINT Investigators. Clopidogrel and aspirin in acute ischemic stroke and high-risk TIA. N Engl J Med. 2018; 379:215–225. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lemmens R, Smet S, Thijs VN. Clinical scores for predicting recurrence after transient ischemic attack or stroke: how good are they? Stroke. 2013; 44:1198–1203. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.000141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mo C, Sun G, Lu ML, Zhang L, Wang YZ, Sun X, Yang YS. Proton pump inhibitors in prevention of low-dose aspirin-associated upper gastrointestinal injuries. World J Gastroenterol. 2015; 21:5382–5392. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i17.5382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Request for anonymized data will be considered by the Cerebrovascular Antiplatelet Trialists Collaboration.