Abstract

Exposure to hydrogen sulfide (H2S) can cause neurotoxicity and cardiopulmonary arrest. Resuscitating victims of sulfide intoxication is extremely difficult, and survivors often exhibit persistent neurological deficits. However, no specific antidote is available for sulfide intoxication. The objective of this study was to examine whether administration of a sulfonyl azide-based sulfide-specific scavenger, SS20, would rescue mice in models of H2S intoxication: ongoing exposure and post-cardiopulmonary arrest. In the ongoing exposure model, SS20 (1250 µmol/kg) or vehicle was administered to awake CD-1 mice intraperitoneally at 10 min after breathing 790 ppm of H2S followed by another 30 min of H2S inhalation. Effects of SS20 on survival were assessed. In the post-cardiopulmonary arrest model, cardiopulmonary arrest was induced by an intraperitoneal administration of sodium sulfide nonahydrate (125 mg/kg) in anesthetized mice. After 1 min of cardiopulmonary arrest, mice were resuscitated with intravenous administration of SS20 (250 µmol/kg) or vehicle. Effects of SS20 on survival, neurological outcomes, and plasma H2S levels were evaluated. Administration of SS20 during ongoing H2S inhalation improved 24-h survival (6/6 [100%] in SS20 vs 1/6 [17%] in vehicle; p = .0043). Post-arrest administration of SS20 improved 7-day survival (4/10 [40%] in SS20 vs 0/10 [0%] in vehicle; p = .0038) and neurological outcomes after resuscitation. SS20 decreased plasma H2S levels to pre-arrest baseline immediately after reperfusion and shortened the time to return of spontaneous circulation and respiration. These results suggest that SS20 is an effective antidote against lethal H2S intoxication, even when administered after cardiopulmonary arrest.

Keywords: hydrogen sulfide, antidotes, heart arrest, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, mice

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is a highly toxic gas that can cause environmental hazards in sewers and sulfur springs, as well as in the oil and gas, sanitation, fishing, and farming industries (Ng et al., 2019; Reiffenstein et al., 1992). As H2S can be produced from easily available materials, it has been increasingly used for suicide (Anderson, 2016; Kamijo et al., 2013; Reedy et al., 2011). H2S has also been listed as a chemical of concern that could be used in terrorist attacks (Ng et al., 2019). Among toxic gases, H2S is the second leading cause of gas-induced death after carbon monoxide (Guidotti, 2010; Mowry et al., 2016). Because H2S is heavier than air, it accumulates in hazardous amounts in low-lying and enclosed areas (Chiu et al., 2020). The exposure-response curve for lethality is exceptionally steep for H2S (Guidotti, 1996). At concentrations >700 parts per million (ppm), H2S can be lethal and lead to sudden collapse referred to as “knockdown” (Milby and Baselt, 1999). According to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration and the Bureau of Labor Statistics, H2S remains a potential source of intoxication in industries (Fuller and Suruda, 2000; Hendrickson et al., 2004). Industrial plant accidents can result in a mass civilian exposure to H2S (McCabe and Clayton 1952; Yang et al., 2006), as witnessed by a sour-gas well blowout in Kaixian county, China, which caused 243 civilian deaths (Yang et al., 2006).

Toxicity of H2S is presumably related to inhibition of cytochrome c oxidase (mitochondrial complex IV), thereby inhibiting adenosine triphosphate production (Módis et al., 2014; Nicholls et al., 2013; Szabo et al., 2014). Exposure to high levels of H2S can be life-threatening, and its effects include shock, respiratory failure, rapid unconsciousness, and coma. Survivors of acute H2S poisoning often suffer from persistent neurologic deficits and neurodegeneration (Ng et al., 2019; Reiffenstein et al., 1992). Several H2S antidotes have shown to have beneficial effects on outcomes in animal models of sulfide intoxication (Haouzi et al., 2020). It was required, however, that these antidotes be administered either before, during, or immediately after sulfide exposure. For example, pre-treatment, but not post-treatment, with sodium nitrite improved survival in mice intoxicated with H2S (Cronican et al., 2015). Hydroxocobalamin, a non-specific H2S scavenger, decreased mortality in sheep when administered at 1 min after the end of H2S exposure (Haouzi et al., 2015, 2020). However, administration of hydroxocobalamin during cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) failed to rescue a man who attempted suicide using H2S gas (Fujita et al., 2011).

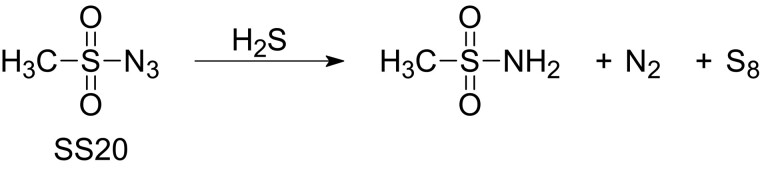

Recently, based on a data-driven approach, we identified several sulfonyl azide-based compounds as H2S-specific scavengers. Among them, SS20, methanesulfonyl azide (MW = 121 g/mol), exhibited high selectivity to and rapid reactivity with H2S, as well as low cellular toxicity and biological activity (Yang et al., 2019, Figure 1). We hypothesized that SS20 would rescue mice exposed to toxic levels of H2S. To address this hypothesis, we sought to determine the effects of SS20 in mice subjected to H2S intoxication in experimental models simulating 2 scenarios: treatment with SS20 during exposure to toxic levels of H2S (ongoing exposure model) and during CPR after cardiopulmonary arrest caused by H2S intoxication (post-cardiopulmonary arrest model). In the ongoing exposure model, SS20 was administered to awake mice exposed to a lethal concentration of H2S to examine whether administration of a H2S scavenger would prolong survival time. As the post-cardiopulmonary arrest model, we developed a mouse model of sulfide intoxication-induced cardiopulmonary arrest and CPR, in which SS20 was administered at the initiation of CPR in anesthetized mice sustaining cardiopulmonary arrest due to H2S poisoning. This experiment would allow us to determine whether post-cardiopulmonary arrest administration of a H2S scavenger improves the success rate of CPR and long-term neurological outcomes.

Figure 1.

Structural formula of SS20, a novel sulfonyl azide-based hydrogen sulfide scavenger, SS20 (Yang et al., 2019). SS20 reacts with hydrogen sulfide to form octasulfur. Abbreviations: H2S, hydrogen sulfide; N2, nitrogen; S8, octasulfur.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

All animal procedures were conducted in accordance with protocols approved by the Massachusetts General Hospital Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and the requirements of the National Research Council’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. We studied 2- to 3-month-old and weight-matched CD-1 male mice (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, Massachusetts). Mice were housed in a temperature-controlled room with a 12-h light/dark cycle and were provided with food and water ab libitum.

Drug Preparation

SS20 was synthesized by the Xian laboratory (Yang et al., 2019, Figure 1).

Ongoing Exposure Model

H2S Inhalation

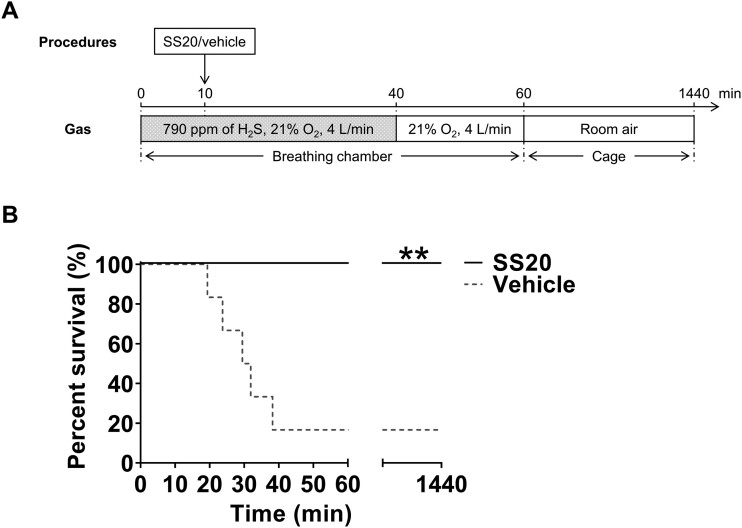

To determine antidotal effects of a novel H2S-specific scavenger during ongoing H2S poisoning, we adopted a lethal H2S exposure experimental protocol described by Jiang et al. (2016) with some modifications (Figure 2A). Mice were exposed to a lethal concentration of H2S (790 ppm in 21% oxygen [O2]) in a breathing chamber (Gas Anesthetizing Box [Cat no.: AB 4]; Braintree Scientific, Inc., Braintree, Massachusetts). To create 790 ppm of H2S gas in 21% O2, we mixed 100% O2 gas (Airgas, Inc., Radnor, Pennsylvania) and 1000 ppm of H2S gas in nitrogen (N2) (Airgas, Inc.). The concentration of H2S and O2 were continuously measured using a gas monitor (iTX Multi-Gas Monitor; Industrial Scientific Corporation, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania). Fresh gas flow was set at 4 l/min throughout the experiment. After 10 min of H2S inhalation, mice were randomly assigned to receive administration of 1250 μmol/kg SS20 or normal saline in a volume of 10 µl/g intraperitoneally. We chose this dose based on our pilot studies. Mice were then returned to the chamber and re-exposed to 790 ppm of H2S gas for another 30 min. After a total of 40-min exposure to H2S, fresh gas was switched to 79% N2 and 21% O2, and mice were allowed to breathe 21% O2 for another 20 min. Subsequently, the mice were returned to cages in room air. Mice with a respiratory rate < 4 breaths/min were deemed to be dead. Mice were monitored for up to 24 h to record the length of survival time during and after H2S poisoning. The primary outcome of the ongoing exposure model was survival rate at 24 h after H2S exposure.

Figure 2.

SS20 rescued mice from ongoing hydrogen sulfide breathing (ongoing exposure model). A, A schematic diagram of the ongoing exposure model. SS20 (1250 µmol/kg) or vehicle was administered to awake mice intraperitoneally at 10 min after breathing 790 ppm of H2S followed by another 30 min of continuous H2S inhalation. B, Percent survival during the first 24 h after H2S inhalation. n = 6 for each group. **p < .01 versus vehicle by log-rank test. Abbreviations: H2S, hydrogen sulfide; O2, oxygen.

Post-cardiopulmonary Arrest Model

Animal Preparation

Mice were anesthetized with 5% isoflurane in 100% O2 and intubated with a 20-gauge catheter (Angiocath; Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey; Figure 3A). Thereafter, mice were mechanically ventilated (MiniVent; Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, Massachusetts) under anesthesia with 2% isoflurane in 21% O2. Tidal volume was set at 8 µl/g, and respiratory rate was set at 110 breaths/min. A temperature probe was inserted into the esophagus. Micro catheters (PE-10; Becton Dickinson) were inserted into the left femoral artery and vein for measurement of arterial blood pressure and drug administration, respectively. Subcutaneous needle electrodes were placed to record an electrocardiogram. Body temperature, arterial blood pressure, and electrocardiogram were recorded and analyzed with the use of a computer-based data acquisition system (LabChart; ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, Colorado).

Figure 3.

A mouse model of sulfide intoxication-induced cardiopulmonary arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (post-cardiopulmonary arrest model). A, A schematic diagram of the post-cardiopulmonary arrest model. Na2S·9H2O (125 mg/kg) was intraperitoneally administered to anesthetized mice to induce cardiopulmonary arrest. After 30 s of cardiopulmonary arrest, SS20 (250 µmol/kg) or vehicle was intravenously administered. To measure plasma H2S levels, blood was taken from mice at 4 time points as follows: baseline, respiratory arrest, 2 min after initiation of CPR, and 24 h after CPR. B, Representative ABP change after sulfide intoxication-induced cardiopulmonary arrest and CPR in vehicle-treated and SS20-treated mouse. Abbreviations: ABP, arterial blood pressure; BT, body temperature; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; ECG, electrocardiogram; Na2S·9H2O, sodium sulfide nonahydrate; O2, oxygen.

Mouse Model of Sulfide Intoxication-Induced Cardiopulmonary Arrest and CPR

To determine the effects of SS20 administered after sulfide-induced cardiopulmonary arrest, we developed a H2S exposure-induced cardiopulmonary arrest model in mice by modifying the mouse model of potassium chloride-induced cardiac arrest, which was established in our laboratory (Hayashida et al., 2019; Ikeda et al., 2016; Kida et al., 2014; Minamishima et al., 2011; Figure 3A). A randomized paired design was used to minimize variability, as previously described (Hayashida et al., 2019). Grouped into pairs based on weight, age, delivery dates, and when possible, holding cages, mice were randomly assigned to different treatments (ie, SS20 or normal saline) within each pair.

Cardiopulmonary arrest was induced by intraperitoneal administration of a lethal dose of sodium sulfide nonahydrate (Na2S·9H2O; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, Missouri; Figs. 3A and 3B). Na2S·9H2O was dissolved in normal saline 1 min before administration and was given intraperitoneally at a dose of 125 mg/kg in a volume of 5 μl/g. We chose this dose based on previous literature (Dulaney and Hume, 1988), as well as our pilot studies. The ventilation circuit was changed to a T-piece circuit immediately after sulfide intoxication to allow mice to breathe spontaneously under isoflurane anesthesia. Isoflurane was discontinued after respiratory arrest was achieved. Cardiac arrest was defined as a systolic blood pressure below 15 mmHg lasting 5 s. After 30 s of cardiac arrest, 250 µmol/kg of SS20 or normal saline in a volume of 2 µl/g was administered via the left femoral vein in a randomized and blinded manner, along with 2.5 μg of epinephrine (25 μg/ml in normal saline). After 1 min of cardiac arrest, mice were resuscitated with chest compression, infusion of 0.6 μg/min of epinephrine (25 μg/ml in normal saline), and mechanical ventilation with 100% O2. Chest compression with a finger was delivered at a rate of 300–350 per minute until a mean arterial pressure >60 mmHg lasting at least 5 s was achieved. Infusion of epinephrine was discontinued when return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) was achieved, which was defined as return of sinus rhythm with a mean arterial pressure >40 mmHg lasting at least 10 s. Core body temperature was maintained at 37°C using a warming lamp throughout the surgical procedure up to 1 h after CPR. One hour after CPR, mice were extubated, with catheters removed, and then returned to cages in room air (ambient temperature about 25°C). The survival time was recorded up to 7 days after CPR. The primary outcomes of the post-cardiopulmonary arrest model were survival rate at 7 days after resuscitation and neurological function at 24 h after resuscitation. The secondary outcomes were the time required until ROSC and return of spontaneous breathing, change in hemodynamics and plasma H2S levels, and brain injury after resuscitation.

Assessment of Neurological Function After Sulfide Intoxication-Induced Cardiopulmonary Arrest and CPR

Using a previously reported scoring system (Hayashida et al., 2019; Ikeda et al., 2016; Kida et al., 2014; Minamishima et al., 2011), neurological function at 24 h after CPR was assessed by an investigator blinded to the experimental group based on the following items: (1) consciousness, (2) corneal reflex, (3) respiration, (4) coordination, and (5) movement and activity, as previously described (Hayashida et al., 2019). Ratings for each item were scored on a 3-point scale with 0 as impaired, 1 as mildly impaired, and 2 as normal. Higher scores were indicative of favorable neurological function.

Measurement of Plasma H2S Levels Before, During, and After Sulfide Intoxication-Induced Cardiopulmonary Arrest and CPR

Mice were sacrificed to measure plasma H2S levels at 4 time points as follows: baseline, respiratory arrest, 2 min after initiation of CPR, and 24 h after CPR (Figure 3A). Blood samples were collected from the inferior vena cava with heparinized syringes. Plasma was prepared by centrifugation for 2 min at 4000 × g using a refrigerated centrifuge, and 15 μl of plasma was snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. To measure plasma H2S levels, we used HSip-1 (synthesized and provided by the Hanaoka laboratory), a H2S-specific fluorescent probe, in the previously described manner with some modifications (Sasakura et al., 2011). In brief, 135 µl of 250 µM HSip-1 was added to 15 µl of the frozen plasma and incubated at room temperature for 20 min, and then 10 µl of the solution was loaded into a 96-well black polystyrene assay plate with clear bottom (Corning, Inc., Kennebunk, Maine), each well containing 90 µl of phosphate-buffered saline. The fluorescence intensities were measured by fluorescence spectroscopy (SpectraMax M5; Molecular Devices, San Jose, California) at the wavelength of λex/λem = 491 nm/516 nm.

Assessment of Histological Neurodegeneration After Sulfide Intoxication-Induced Cardiopulmonary Arrest and CPR

Neuronal degeneration in the cerebral cortex at 24 h after CPR was evaluated with Fluoro-Jade B (Histo-Chem, Inc., Jefferson, AR) and 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich) staining, in the previously described manner with some modifications (Schmued and Hopkins, 2000). In brief, 20-µm frozen brain sections were stained with Fluoro-Jade B and 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride, and then cerebral cortex was observed using an epifluorescence microscope (Nikon Eclipse 80i; Nikon Instruments, Inc., Melville, New York). Four brain sections per mouse brain were examined, from which 8 images of cerebral cortex per brain section were selected (Figure 8A). Totally, 32 images of cerebral cortex were obtained in each mouse, and the number of Fluoro-Jade B positive cells were counted automatically using ImageJ 1.53 g (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland) by an investigator blinded to the identity of samples. Fixed-level binary thresholding was applied to the images with pixel intensities ranging from 50 to 255. The average number of Fluoro-Jade B positive cells per mm2 was calculated in each mouse.

Figure 8.

Histological effects of SS20 on brain injury in mice after sulfide intoxication-induced cardiopulmonary arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (post-cardiopulmonary arrest model). A, A mouse brain atlas with the examined parts of the cerebral cortex. B, The number of Fluoro-Jade B positive cells per mm2 in the cerebral cortex of vehicle-treated or SS20-treated mice at 24 h after sulfide intoxication-induced cardiopulmonary arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation. n = 6 for each group. **p < .01 by independent t test. C and D, Representative photomicrographs of cerebral cortex sections from mice treated with vehicle or SS20 showing Fluoro-Jade B and DAPI positive cells at 24 h after sulfide intoxication-induced cardiopulmonary arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Scale bars: C, 500 µm; and D, 100 µm. Abbreviations: FJB, Fluoro-Jade B; DAPI, 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the study populations. Data are presented as means with standard deviation or medians with interquartile range. Categorical data are presented as counts with frequencies. We used Shapiro-Wilk test and Q-Q plots to assess the normality of the data. Parametric data were analyzed using an independent t test, 2-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test, or 2-way repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. Non-parametric data were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney test. Kaplan–Meier and the Log-rank test were used for survival analysis. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California) with 2-tailed hypothesis testing.

Sample size calculations were carried out using G*Power 3.1 (Heinrich-Heine-Universität, Düsseldorf, Germany, Faul et al., 2009). In the ongoing exposure model, based on our pilot studies, we presumed that the mean survival rate at 24 h after H2S inhalation would be 15% in vehicle-treated mice and 99.5% in SS20-treated mice, respectively. We presumed that 6 mice per group would be required for the survival study (α = 0.05, β = 0.2 [Power = 0.8], 2-sided). In the post-cardiopulmonary arrest model, since the mean survival rate at 7 days after CPR was expected as 0.5% in vehicle-treated mice and 60% in SS20-treated mice, we anticipated that 10 mice per group would be required for the survival study (α = 0.05, β = 0.2 [Power = 0.8], 2-sided).

RESULTS

Ongoing Exposure Model

Administration of SS20 Rescued Mice from Ongoing H2S Breathing

We observed that administration of SS20 during ongoing H2S exposure markedly prolonged survival time compared with vehicle treatment (6/6 [100%] in SS20 vs 1/6 [17%] in vehicle; p = .0043 by log-rank test; Figure 2B). These results suggest antidotal effects of SS20 during ongoing H2S intoxication.

Post-cardiopulmonary Arrest Model

Administration of SS20 Improved Survival and Neurological Function After Sulfide Intoxication-Induced Cardiopulmonary Arrest in Mice

After surgical preparation, we intraperitoneally administered Na2S·9H2O to 25 mice. Cardiac arrest was achieved in 22 of 25 mice; 10 of them were treated with SS20 and the remaining 12 were treated with vehicle. Two of the vehicle-treated mice were not successfully resuscitated after sulfide intoxication-induced cardiopulmonary arrest (Figure 4A). Percent survival during the first 7 days after CPR was significantly higher in SS20-treated mice than in vehicle-treated mice (4/10 [40%] in SS20 vs 0/10 [0%] in vehicle; p = .0038 by log-rank test, Figure 4B). Neurological function score at 24 h after CPR was significantly higher in SS20-treated mice than in vehicle-treated mice (10 [9.75–10.00] in SS20 vs 6.5 [2.75–9.25] in vehicle; n = 10 for each; p = .0060 by Mann-Whitney test; Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

SS20 improved survival and neurological function after sulfide intoxication-induced cardiopulmonary arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (post-cardiopulmonary arrest model). A, Cardiopulmonary arrest was achieved in 22 of 25 mice subjected to sulfide intoxication; 10 were treated with SS20, and 12 were treated with vehicle. ROSC was achieved in 10/10 (100%) of SS20-treated mice and in 10/12 (83%) of vehicle-treated mice. B, Percent survival during the first 7 days after CPR. n = 10 for each group. **p < .01 versus vehicle by log-rank test. C, Neurological function score at 24 h after CPR. n = 10 for each group. ††p < .01 by Mann-Whitney test. Dead mice (rated as zero) were excluded from analysis. Abbreviations: CPA, cardiopulmonary arrest; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; ROSC, return of spontaneous circulation.

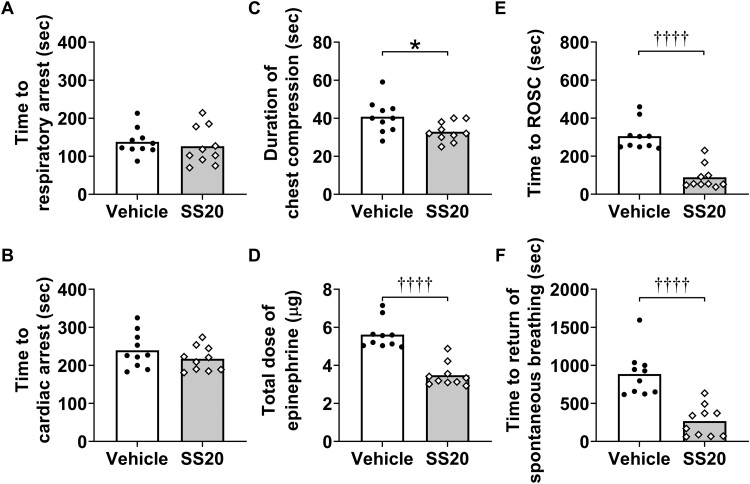

SS20 Shortened the Time Required for CPR and Increased Blood Pressure and Heart Rates After CPR

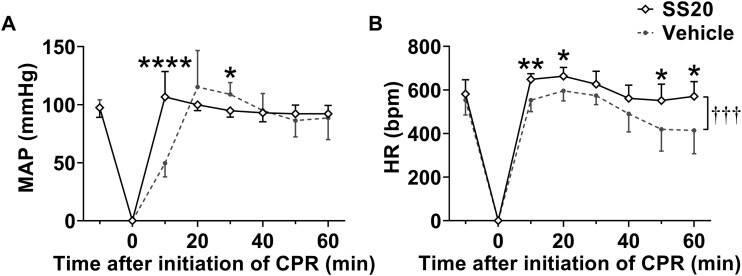

Parameters during H2S-induced cardiac arrest and CPR were summarized in Figure 5. Before treatment, there were no differences between groups in the length of time from administration of Na2S·9H2O to respiratory arrest (Time to respiratory arrest [seconds]; 126 ± 50 in SS20 vs 138 ± 35 in vehicle; n = 10 for each; p = .5539 by independent t test; Figure 5A) and to cardiac arrest (Time to cardiac arrest [seconds]; 217 ± 32 in SS20 vs 240 ± 47 in vehicle; n = 10 for each; p = .2283 by independent t test, Figure 5B). When compared with vehicle, SS20 shortened time to ROSC (seconds) (55 [51–116] in SS20 vs 281 [249–337] in vehicle; n = 10 for each; p < .0001 by Mann-Whitney test; Figure 5E), duration of chest compression (seconds) (33 ± 5 in SS20 vs 41 ± 9 in vehicle; n = 10 for each; p = .0235 by independent t test; Figure 5C), and time to return of spontaneous breathing (seconds) (255 [70–403] in SS20 vs 863 [645–1009] in vehicle; n = 10 for each; p < .0001 by Mann-Whitney test; Figure 5F) and decreased total dose of epinephrine (µg) (3.3 [3.1–3.7] in SS20 vs 5.4 [5.0–5.9] in vehicle; n = 10 for each; p < .0001 by Mann-Whitney test; Figure 5D). We also recorded changes in mean arterial pressure and heart rates from baseline until 1 h after initiation of CPR. The mean arterial pressure at 10 min after initiation of CPR, and heart rates in the first hour after CPR were significantly higher in SS20-treated mice than in vehicle-treated mice (p < .0001 and p = .0004, respectively; n = 10 for each; Figs. 6A and 6B).

Figure 5.

Administration of SS20 shortened the time required for cardiopulmonary resuscitation (post-cardiopulmonary arrest model). A and B, The length of time from sulfide intoxication to each time point. Note that the parameters were obtained before treatment with vehicle or SS20. C and D, Parameters during cardiopulmonary resuscitation in mice treated with vehicle or SS20. E and F, The length of time from the initiation of cardiopulmonary resuscitation to each time point in mice treated with vehicle or SS20. n = 10 for each group. *p < .05 by independent t test. ††††p < .0001 by Mann-Whitney test. Abbreviation: ROSC, return of spontaneous circulation.

Figure 6.

Administration of SS20 increased blood pressure and heart rates after cardiopulmonary resuscitation (post-cardiopulmonary arrest model). A, Changes in mean arterial pressure until 1 h after cardiopulmonary resuscitation. B, Changes in heart rates until 1 h after cardiopulmonary resuscitation. n = 10 for each group. †††p < .001 between groups, *p < .05, **p < .01, ****p < .0001 by 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. The error bars represent SD. Abbreviations: CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; HR, heart rates; MAP, mean arterial pressure.

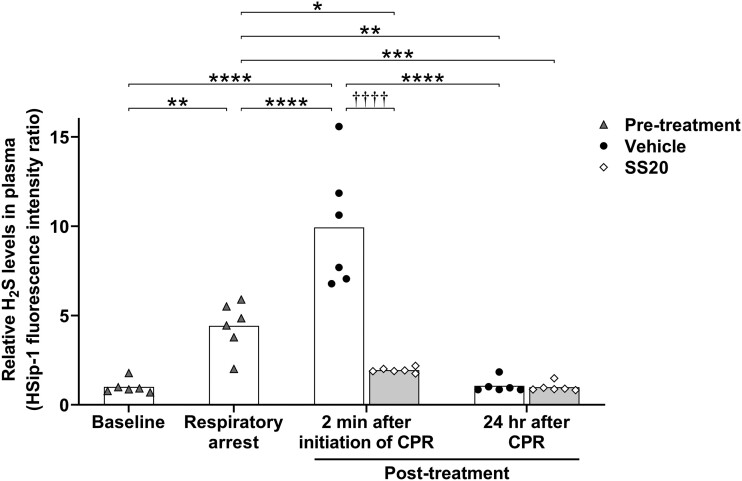

Post-arrest Administration of SS20 Decreased Plasma H2S Levels Immediately After Reperfusion in Sulfide-Intoxicated Mice

As a result of Na2S·9H2O administration, the plasma concentration of H2S was approximately 4 times higher than the baseline value at respiratory arrest (n = 6 for each; p = .0010; Figure 7). At 2 min after the initiation of CPR, plasma H2S levels in vehicle-treated mice were approximately 10 times higher than baseline (n = 6 for each; p < .0001), whereas plasma H2S levels in SS20-treated mice were reduced as low as pre-arrest baseline levels (n = 6 for each; p > .9999) and were significantly lower than in vehicle-treated mice (n = 6 for each; p < .0001). Plasma H2S levels at 24 h after CPR were decreased to baseline levels in both groups (n = 6 for each; p > .9999).

Figure 7.

Post-arrest administration of SS20 decreased plasma hydrogen sulfide levels immediately after reperfusion (post-cardiopulmonary arrest model). Blood samples were collected at the following time points: baseline, respiratory arrest, 2 min after initiation of CPR, and 24 h after CPR. Relative H2S levels in plasma were measured using HSip-1, a highly specific fluoroprobe for detecting H2S. n = 6 for each time point and treatment. ††††p < .0001 between groups, *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001, ****p < .0001 by 2-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test. Abbreviations: CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; H2S, hydrogen sulfide.

Administration of SS20 Prevented Brain Injury After Sulfide Intoxication-Induced Cardiopulmonary Arrest and CPR

At 24 h after CPR, the number of Fluoro-Jade B positive cells in the cerebral cortex was significantly higher in vehicle-treated mice than in SS20-treated mice (140 ± 139 in SS20 vs 1055 ± 621 in vehicle [Fluoro-Jade B positive cells/mm2]; n = 6 for each; p = .0055 by independent t test; Figure 8B).

DISCUSSION

This study revealed that administration of a sulfonyl azide-based H2S scavenger, SS20, markedly prolonged survival time in mice breathing toxic levels of H2S. In addition, administration of SS20 reduced plasma H2S levels, shortened time to the return of spontaneous circulation and breathing, improved survival and neurological function, and attenuated brain injury in mice resuscitated from sulfide intoxication-induced cardiopulmonary arrest. Taken together, these observations indicate that SS20 could be an effective antidote for H2S poisoning.

Although a number of compounds including cobinamide, methylene blue, hydroxocobalamin, sodium nitrite, methemoglobin, midazolam, thiosulfate, dithiothreitol, pyruvate, and 4-dimethylaminophenol have been studied as a possible antidote for H2S intoxication (Anantharam et al., 2018; Chenuel et al., 2015; Dulaney and Hume, 1988; Haouzi et al., 2020; Lindenmann et al., 2010; Ng et al., 2019; Smith et al., 1976; Warenycia et al., 1990), none of them have been approved as an antidote for H2S poisoning (Haouzi et al., 2020). These agents have been administered before, during, or immediately after H2S exposure, while there has been no experimental study testing the effects of a H2S antidote administered after cardiopulmonary arrest resulting from H2S intoxication. It should be also mentioned that the majority of the previously studied agents have a non-specific mechanism of action. In addition to the ability to scavenge H2S, hydroxocobalamin and cobinamide remove nitric oxide, carbon monoxide, and reactive oxygen species (Jiang et al., 2016; Sharma et al., 2003).

Recently, a H2S sensor database was constructed to develop specific H2S scavengers (Yang et al., 2019). Data-driven analysis identified a series of compounds that scavenge H2S. Notably, unlike non-specific H2S scavengers, some compounds with a sulfonyl azide template exhibited high specificity and reactivity with sulfide. Among them, we selected SS20 as a promising H2S scavenger for the current study, given its low cellular and in vivo toxicity (Yang et al., 2019).

In the ongoing exposure model (Figure 2A), administration of SS20 during exposure rescued all 6 awake mice breathing a lethal dose of H2S, whereas 83% (5/6) of vehicle-treated mice died during H2S inhalation. Since inhalation is the major route of H2S exposure for humans, animal models of H2S inhalation have been used to evaluate the effects of antidotes against H2S intoxication (Anantharam et al., 2017b, 2018; Hendry‐Hofer et al., 2020; Jiang et al., 2016; Smith and Gosselin, 1964). The strength of the ongoing exposure model is that a H2S-specific scavenger was administered to awake mice breathing a lethal concentration of H2S. Although the best course of action in the situation of H2S intoxication is to evacuate victims from the red zone as quickly as possible and provide treatment in clean air (Henretig et al., 2019; Kales and Christiani, 2004), accidents can happen where swift evacuation of victims is nearly impossible. For example, fatal toxic gas exposure incidents have occurred in the bilges of a ship and the underground subway stations in Japan where evacuation to clean air undoubtedly takes more than several minutes (Okumura et al., 2005; Ventura Spagnolo et al., 2019). Our results suggest that, under these circumstances, starting treatment with specific H2S scavengers during ongoing exposure may save lives of victims and rescuers.

In the post-cardiopulmonary arrest model (Figure 3A), we observed that plasma H2S levels were significantly higher in vehicle-treated mice at 2 min after CPR than at respiratory arrest. Given that intraperitoneal injection was chosen as the route of Na2S·9H2O administration in the current study, it is possible that plasma H2S levels remained high after CPR due to the absorption of H2S from the peritoneal cavity. Our findings suggest that spontaneous circulation can be restored with effective CPR even when blood sulfide levels are high enough to cause respiratory arrest.

As compared with vehicle-treated mice, the mean arterial pressure at 10 min after CPR and heart rates during the first hour after CPR were higher in SS20-treated mice in the post-cardiopulmonary arrest model. Plasma H2S levels in vehicle-treated mice were increased at 2 min after CPR than at respiratory arrest, whereas administration of SS20 decreased plasma H2S levels to baseline levels immediately after reperfusion. Exposure to H2S has been shown to reduce cardiac output, blood pressure, and heart rates (Haouzi et al., 2019; Judenherc-Haouzi et al., 2016, 2018; Sonobe and Haouzi, 2015, 2016; Swan et al., 2017). Mitochondrial function could be inhibited by a lethal concentration of H2S, resulting in acute cardiac dysfunction (Cooper and Brown, 2008; Khan et al., 1990; Sonobe and Haouzi, 2016). In our experimental model, the difference in the amount of H2S remaining in blood and tissues may explain why blood pressure and heart rates differed after CPR between SS20-treated and vehicle-treated mice. These observations suggest that administration of SS20 decreased systemic H2S levels, thereby stabilizing blood pressure and heart rates.

Increased cardiac output is associated with increased O2 delivery to the peripheral tissues (Hameed et al., 2003), which may accelerate sulfide oxidation (DeLeon et al., 2012; Fukuto et al., 2012; Luther et al., 2011; Olson and Straub, 2016). In addition, gas exchange is improved with increased cardiac output (Wagner, 2015), promoting removal of H2S from the pulmonary circulation. Prolonged hypotension after sulfide intoxication might further exacerbate brain injury (Baldelli et al., 1993). Taken together, it is possible that improved hemodynamics contributed to reduced H2S levels and favorable outcomes in H2S-intoxicated mice that were treated with SS20.

Victims of H2S poisoning can exhibit metabolic and pathological changes in the brain, as well as long-term motor and cognitive dysfunction (Kobayashi and Shiraishi, 2017; Milroy and Parai, 2011; Park et al., 2009; Schneider et al., 1998; Tvedt et al., 1991a, b). Neurological or behavioral deficits and brain injury have been observed in previous animal models of H2S intoxication (Anantharam et al., 2017a; Sonobe et al., 2015). In our experimental model that was designed to simulate H2S poisoning, SS20 improved neurological function and prevented neurodegeneration in the cerebral cortex after H2S-induced cardiopulmonary arrest. It is of note that a H2S scavenger attenuated brain injury even when administered after cardiopulmonary arrest.

We recognize several limitations of the current study. First, when testing the potential of SS20 to rescue mice subjected to sulfide intoxication-induced cardiopulmonary arrest (post-cardiopulmonary arrest model), we used intraperitoneal administration of Na2S·9H2O for the sake of laboratory safety. Although inhalation of toxic levels of H2S and intraperitoneal injection of a H2S donor produced indistinguishable increases in brain sulfide levels (Reiffenstein et al., 1992), it could be likely that inhaled H2S and intraperitoneally injected Na2S·9H2O have different toxicological effects. For example, non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema can be caused by the former, but not by the latter (Lopez et al., 1989; Sonobe et al., 2015). Second, intramuscular injection would be a preferred route for administration of antidotes during mass-casualty events. In the current study, SS20 was administered intraperitoneally or intravenously, as the volume of SS20 exceeded the maximum recommended volume for intramuscular injection in mice (0.05 µl/g per site) because of the small muscle mass of mice (Turner et al., 2011). We chose to give SS20 intraperitoneally in the ongoing exposure model to minimize stress and distress of animals. Intraperitoneal administration provides similar absorption kinetics of injected small molecules, compared with intramuscular administration (Al Shoyaib et al., 2019). Third, histological examination of brain injury was performed at 24 h after CPR (post-cardiopulmonary arrest model). It is possible that further neurodegeneration becomes more apparent at later time points (eg, 72 h post-CPR; Anantharam et al., 2017a; Butler et al., 2002; Duckworth et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2018; Lipton, 1999). Finally, we used only male mice in the current study, based on the finding that male mice were more sensitive to H2S-induced neurotoxicity than female mice (Anantharam et al., 2017a).

In conclusion, our study highlighted the antidotal effects of a sulfonyl azide-based H2S-specific scavenger, SS20, against H2S intoxication. Administration of SS20 was associated with improved outcomes and decreased plasma H2S levels in mice models of H2S intoxication.

FUNDING

National Institutes of Health grant R21NS116671 to Dr Ichinose and Dr Xian.

DECLARATION OF CONFLICTING INTERESTS

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

REFERENCES

- Al Shoyaib A., Archie S. R., Karamyan V. T. (2019). Intraperitoneal route of drug administration: Should it be used in experimental animal studies? Pharm. Res. 37, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anantharam P., Kim D. S., Whitley E. M., Mahama B., Imerman P., Padhi P., Rumbeiha W. K. (2018). Midazolam efficacy against acute hydrogen sulfide-induced mortality and neurotoxicity. J. Med. Toxicol. 14, 79–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anantharam P., Whitley E. M., Mahama B., Kim D. S., Imerman P. M., Shao D., Langley M. R., Kanthasamy A., Rumbeiha W. K. (2017a). Characterizing a mouse model for evaluation of countermeasures against hydrogen sulfide-induced neurotoxicity and neurological sequelae. Ann.N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1400, 46–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anantharam P., Whitley E. M., Mahama B., Kim D. S., Sarkar S., Santana C., Chan A., Kanthasamy A. G., Kanthasamy A., Boss G. R., et al. (2017b). Cobinamide is effective for treatment of hydrogen sulfide-induced neurological sequelae in a mouse model. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1408, 61–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson A. R. (2016). Characterization of chemical suicides in the United States and its adverse impact on responders and bystanders. West J. Emerg. Med. 17, 680–683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldelli R. J., Green F. H., Auer R. N. (1993). Sulfide toxicity: Mechanical ventilation and hypotension determine survival rate and brain necrosis. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 75, 1348–1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler T. L., Kassed C. A., Sanberg P. R., Willing A. E., Pennypacker K. R. (2002). Neurodegeneration in the rat hippocampus and striatum after middle cerebral artery occlusion. Brain Res. 929, 252–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenuel B., Sonobe T., Haouzi P. (2015). Effects of infusion of human methemoglobin solution following hydrogen sulfide poisoning. Clin. Toxicol. 53, 93–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu C. C., Chang Y. M., Wan T. J. (2020). Characteristic analysis of occupational confined space accidents in Taiwan and its prevention strategy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17,1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper C. E., Brown G. C. (2008). The inhibition of mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase by the gases carbon monoxide, nitric oxide, hydrogen cyanide and hydrogen sulfide: Chemical mechanism and physiological significance. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 40, 533–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronican A. A., Frawley K. L., Ahmed H., Pearce L. L., Peterson J. (2015). Antagonism of acute sulfide poisoning in mice by nitrite anion without methemoglobinemia. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 28, 1398–1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLeon E. R., Stoy G. F., Olson K. R. (2012). Passive loss of hydrogen sulfide in biological experiments. Anal. Biochem. 421, 203–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth E. A. M., Butler T. L., De Mesquita D., Collier S. N., Collier L., Pennypacker K. R. (2005). Temporary focal ischemia in the mouse: Technical aspects and patterns of fluoro-jade evident neurodegeneration. Brain Res. 1042, 29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulaney M. Jr.,, Hume A. S. (1988). Pyruvic acid protects against the lethality of sulfide. Res. Commun. Chem. Pathol. Pharmacol. 59, 133–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul F., Erdfelder E., Buchner A., Lang A.-G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 41, 1149–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita Y., Fujino Y., Onodera M., Kikuchi S., Kikkawa T., Inoue Y., Niitsu H., Takahashi K., Endo S. (2011). A fatal case of acute hydrogen sulfide poisoning caused by hydrogen sulfide: Hydroxocobalamin therapy for acute hydrogen sulfide poisoning. J. Anal. Toxicol. 35, 119–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuto J. M., Carrington S. J., Tantillo D. J., Harrison J. G., Ignarro L. J., Freeman B. A., Chen A., Wink D. A. (2012). Small molecule signaling agents: The integrated chemistry and biochemistry of nitrogen oxides, oxides of carbon, dioxygen, hydrogen sulfide, and their derived species. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 25, 769–793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller D. C., Suruda A. J. (2000). Occupationally related hydrogen sulfide deaths in the united states from 1984 to 1994. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 42, 939–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidotti T. L. (1996). Hydrogen sulphide. Occup. Med. (Lond.) 46, 367–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidotti T. L. (2010). Hydrogen sulfide: Advances in understanding human toxicity. Int. J. Toxicol. 29, 569–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hameed S. M., Aird W. C., Cohn S. M. (2003). Oxygen delivery. Crit. Care Med. 31(12 Suppl), S658–S667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haouzi P., Chenuel B., Sonobe T. (2015). High-dose hydroxocobalamin administered after H2S exposure counteracts sulfide-poisoning-induced cardiac depression in sheep. Clin. Toxicol. (Phila.) 53, 28–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haouzi P., Sonobe T., Judenherc-Haouzi A. (2020). Hydrogen sulfide intoxication induced brain injury and methylene blue. Neurobiol. Dis. 133, 104474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haouzi P., Tubbs N., Cheung J., Judenherc-Haouzi A. (2019). Methylene blue administration during and after life-threatening intoxication by hydrogen sulfide: Efficacy studies in adult sheep and mechanisms of action. Toxicol. Sci. 168, 443–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashida K., Bagchi A., Miyazaki Y., Hirai S., Seth D., Silverman M. G., Rezoagli E., Marutani E., Mori N., Magliocca A., et al. (2019). Improvement in outcomes after cardiac arrest and resuscitation by inhibition of s-nitrosoglutathione reductase. Circulation 139, 815–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickson R. G., Chang A., Hamilton R. J. (2004). Co-worker fatalities from hydrogen sulfide. Am. J. Ind. Med. 45, 346–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendry‐Hofer T. B., Ng P. C., Mcgrath A. M., Mukai D., Brenner M., Mahon S., Maddry J. K., Boss G. R., Bebarta V. S. (2020). Intramuscular aminotetrazole cobinamide as a treatment for inhaled hydrogen sulfide poisoning in a large swine model. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1479, 159–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henretig F. M., Kirk M. A., Mckay C. A. (2019). Hazardous chemical emergencies and poisonings. N. Engl. J. Med. 380, 1638–1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda K., Liu X., Kida K., Marutani E., Hirai S., Sakaguchi M., Andersen L. W., Bagchi A., Cocchi M. N., Berg K. M., et al. (2016). Thiamine as a neuroprotective agent after cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 105, 138–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J., Chan A., Ali S., Saha A., Haushalter K. J., Lam W. L., Glasheen M., Parker J., Brenner M., Mahon S. B., et al. (2016). Hydrogen sulfide–mechanisms of toxicity and development of an antidote. Sci. Rep. 6, 20831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judenherc-Haouzi A., Sonobe T., Bebarta V. S., Haouzi P. (2018). On the efficacy of cardio-pulmonary resuscitation and epinephrine following cyanide- and H2S intoxication-induced cardiac asystole. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 18, 436–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judenherc-Haouzi A., Zhang X. Q., Sonobe T., Song J., Rannals M. D., Wang J., Tubbs N., Cheung J. Y., Haouzi P. (2016). Methylene blue counteracts H2S toxicity-induced cardiac depression by restoring l-type ca channel activity. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 310, R1030–1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kales S. N., Christiani D. C. (2004). Acute chemical emergencies. N. Engl. J. Med. 350, 800–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamijo Y., Takai M., Fujita Y., Hirose Y., Iwasaki Y., Ishihara S. (2013). A multicenter retrospective survey on a suicide trend using hydrogen sulfide in Japan. Clin. Toxicol. (Phila.) 51, 425–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan A. A., Schuler M. M., Prior M. G., Yong S., Coppock R. W., Florence L. Z., Lillie L. E. (1990). Effects of hydrogen sulfide exposure on lung mitochondrial respiratory chain enzymes in rats. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 103, 482–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kida K., Shirozu K., Yu B., Mandeville J. B., Bloch K. D., Ichinose F. (2014). Beneficial effects of nitric oxide on outcomes after cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation in hypothermia-treated mice. Anesthesiology 120, 880–889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. S., Anantharam P., Hoffmann A., Meade M. L., Grobe N., Gearhart J. M., Whitley E. M., Mahama B., Rumbeiha W. K. (2018). Broad spectrum proteomics analysis of the inferior colliculus following acute hydrogen sulfide exposure. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 355, 28–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi H., Shiraishi A. (2017). Young adult male in a coma. Ann. Emerg. Med. 70, 430–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindenmann J., Matzi V., Neuboeck N., Ratzenhofer-Komenda B., Maier A., Smolle-Juettner F. M. (2010). Severe hydrogen sulphide poisoning treated with 4-dimethylaminophenol and hyperbaric oxygen. Diving Hyperb. Med. 40, 213–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton P. (1999). Ischemic cell death in brain neurons. Physiol. Rev. 79, 1431–1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez A., Prior M. G., Reiffenstein R. J., Goodwin L. R. (1989). Peracute toxic effects of inhaled hydrogen sulfide and injected sodium hydrosulfide on the lungs of rats. Fundam. Appl. Toxicol. 12, 367–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luther G. W. 3rd, Findlay A. J., Macdonald D. J., Owings S. M., Hanson T. E., Beinart R. A., Girguis P. R. (2011). Thermodynamics and kinetics of sulfide oxidation by oxygen: A look at inorganically controlled reactions and biologically mediated processes in the environment. Front. Microbiol. 2, 62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe L. C., Clayton G. D. (1952). Air pollution by hydrogen sulfide in Poza Rica, Mexico; an evaluation of the incident of Nov. 24, 1950. AMA Arch. Ind. Hyg. Occup. Med. 6, 199–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milby T. H., Baselt R. C. (1999). Hydrogen sulfide poisoning: Clarification of some controversial issues. Am. J. Ind. Med. 35, 192–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milroy C., Parai J. (2011). Hydrogen sulphide discoloration of the brain. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 7, 225–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minamishima S., Kida K., Tokuda K., Wang H., Sips P. Y., Kosugi S., Mandeville J. B., Buys E. S., Brouckaert P., Liu P. K., et al. (2011). Inhaled nitric oxide improves outcomes after successful cardiopulmonary resuscitation in mice. Circulation 124, 1645–1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Módis K., Bos E. M., Calzia E., Van Goor H., Coletta C., Papapetropoulos A., Hellmich M. R., Radermacher P., Bouillaud F., Szabo C. (2014). Regulation of mitochondrial bioenergetic function by hydrogen sulfide. Part ii. Pathophysiological and therapeutic aspects. Br. J. Pharmacol. 171, 2123–2146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mowry J. B., Spyker D. A., Brooks D. E., Zimmerman A., Schauben J. L. (2016). 2015 annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ national poison data system (NPDS): 33rd Annual Report. Clin. Toxicol. 54, 924–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng P. C., Hendry-Hofer T. B., Witeof A. E., Brenner M., Mahon S. B., Boss G. R., Haouzi P., Bebarta V. S. (2019). Hydrogen sulfide toxicity: Mechanism of action, clinical presentation, and countermeasure development. J. Med. Toxicol. 15, 287–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls P., Marshall D. C., Cooper C. E., Wilson M. T. (2013). Sulfide inhibition of and metabolism by cytochrome c oxidase. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 41, 1312–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okumura T., Hisaoka T., Yamada A., Naito T., Isonuma H., Okumura S., Miura K., Sakurada M., Maekawa H., Ishimatsu S., et al. (2005). The Tokyo subway sarin attack–lessons learned. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 207, 471–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson K. R., Straub K. D. (2016). The role of hydrogen sulfide in evolution and the evolution of hydrogen sulfide in metabolism and signaling. Physiology 31, 60–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S. H., Zhang Y., Hwang J. J. (2009). Discolouration of the brain as the only remarkable autopsy finding in hydrogen sulphide poisoning. Forensic Sci. Int. 187, e19-21–e21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reedy S. J., Schwartz M. D., Morgan B. W. (2011). Suicide fads: Frequency and characteristics of hydrogen sulfide suicides in the United States. West J. Emerg. Med. 12, 300–304. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiffenstein R. J., Hulbert W. C., Roth S. H. (1992). Toxicology of hydrogen sulfide. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 32, 109–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasakura K., Hanaoka K., Shibuya N., Mikami Y., Kimura Y., Komatsu T., Ueno T., Terai T., Kimura H., Nagano T. (2011). Development of a highly selective fluorescence probe for hydrogen sulfide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 18003–18005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmued L. C., Hopkins K. J. (2000). Fluoro-Jade B: A high affinity fluorescent marker for the localization of neuronal degeneration. Brain Res. 874, 123–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider J. S., Tobe E. H., Mozley P. D. Jr., Barniskis L., Lidsky T. I. (1998). Persistent cognitive and motor deficits following acute hydrogen sulphide poisoning. Occup. Med. (Lond.) 48, 255–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma V. S., Pilz R. B., Boss G. R., Magde D. (2003). Reactions of nitric oxide with vitamin B12 and its precursor, cobinamide. Biochemistry 42, 8900–8908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R. P., Gosselin R. E. (1964). The influence of methemoglobinemia on the lethality of some toxic anions. II. Sulfide. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 6, 584–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R. P., Kruszyna R., Kruszyna H. (1976). Management of acute sulfide poisoning. Effects of oxygen, thiosulfate, and nitrite. Arch. Environ. Health 31, 166–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonobe T., Chenuel B., Cooper T. K., Haouzi P. (2015). Immediate and long-term outcome of acute H2S intoxication induced coma in unanesthetized rats: Effects of methylene blue. PLoS One 10, e0131340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonobe T., Haouzi P. (2015). H2S induced coma and cardiogenic shock in the rat: Effects of phenothiazinium chromophores. Clin. Toxicol. (Phila.) 53, 525–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonobe T., Haouzi P. (2016). Sulfide intoxication-induced circulatory failure is mediated by a depression in cardiac contractility. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 16, 67–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan K. W., Song B. M., Chen A. L., Chen T. J., Chan R. A., Guidry B. T., Katakam P. V. G., Kerut E. K., Giles T. D., Kadowitz P. J. (2017). Analysis of decreases in systemic arterial pressure and heart rate in response to the hydrogen sulfide donor sodium sulfide. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 313, H732–H743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo C., Ransy C., Módis K., Andriamihaja M., Murghes B., Coletta C., Olah G., Yanagi K., Bouillaud F. (2014). Regulation of mitochondrial bioenergetic function by hydrogen sulfide. Part I. Biochemical and physiological mechanisms. Br. J. Pharmacol. 171, 2099–2122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner P. V., Brabb T., Pekow C., Vasbinder M. A. (2011). Administration of substances to laboratory animals: Routes of administration and factors to consider. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 50, 600–613. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tvedt B., Edland A., Skyberg K., Forberg O. (1991a). Delayed neuropsychiatric sequelae after acute hydrogen sulfide poisoning: Affection of motor function, memory, vision and hearing. Acta Neurol. Scand. 84, 348–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tvedt B., Skyberg K., Aaserud O., Hobbesland A., Mathiesen T. (1991b). Brain damage caused by hydrogen sulfide: A follow-up study of six patients. Am. J. Ind. Med. 20, 91–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura Spagnolo E., Romano G., Zuccarello P., Laudani A., Mondello C., Argo A., Zerbo S., Barbera N. (2019). Toxicological investigations in a fatal and non-fatal accident due to hydrogen sulphide (h(2)s) poisoning. Forensic Sci. Int. 300, e4–e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner P. D. (2015). The physiological basis of pulmonary gas exchange: Implications for clinical interpretation of arterial blood gases. Eur. Respir. J. 45, 227–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warenycia M. W., Goodwin L. R., Francom D. M., Dieken F. P., Kombian S. B., Reiffenstein R. J. (1990). Dithiothreitol liberates non-acid labile sulfide from brain tissue of H2S-poisoned animals. Arch. Toxicol. 64, 650–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C. T., Wang Y., Marutani E., Ida T., Ni X., Xu S., Chen W., Zhang H., Akaike T., Ichinose F., et al. (2019). Data-driven identification of hydrogen sulfide scavengers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 58, 10898–10902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang D., Chen G., Zhang R. (2006). Estimated public health exposure to H2S emissions from a sour gas well blowout in Kaixian county, China. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 6, 430–443. [Google Scholar]