Abstract

Background:

A self-administered tablet app, StaySafe, helps people under community supervision to make better decisions regarding health risk behaviors, especially those linked to HIV, viral hepatitis, and other sexually transmitted infections. The multi-session StaySafe design uses an interactive, analytical schema called WORKIT that guides users through a series of steps, questions, and exercises aimed at promoting critical thinking about health risks associated with substance use and unprotected sex. Repetition of the WORKIT schema is designed to enhance procedural memory that can be rapidly accessed when individuals are faced with making decisions about risky behaviors.

Methods:

A total of 511 participants under community supervision in community and residential treatment settings from three large Texas counties completed consent forms and baseline surveys, followed by randomization to one of two conditions: 12 weekly StaySafe sessions or standard practice (SP). The study also asked participants to complete a follow-up survey three months after baseline. Outcome measures included knowledge, confidence, and motivation (KCM) scales around HIV knowledge, avoiding risky sex, HIV services, and reducing health risks; decision-making; and reports of talking about issues such as making better decisions, avoiding HIV risks, and HIV prevention or treatment with others (probation officers, counselors, trusted friend or advisor, or family members).

Results:

Participants in both community and residential settings voluntarily completed multiple StaySafe sessions, with those in the residential settings completing more sessions. When compared with SP participants, StaySafe participants showed greater improvement in the KCM measures—HIV knowledge, avoiding sex risks, HIV services, and risk reduction skills. In addition, greater improvements in the KCM measures as well as an increased likelihood to discuss issues with others were associated with completing more StaySafe sessions.

Conclusion:

These results suggest that the StaySafe app is a feasible and potentially effective tool for improving health risk reduction decision-making for individuals under community supervision.

Keywords: Technology, Health risk, Decision-making, Community supervision, Substance use

1. Introduction

By the end of 2016, approximately 4.5 million adults in the United States were under community supervision (e.g., on parole or probation; Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2018). People in the criminal justice system often have increased long-term health risks because of substance use, which is associated with needle sharing and risky sexual activities (including sex without condoms, sex with strangers, and sex with multiple partners). Particularly concerning is that methamphetamine, heroin use, and other injection drug use have been linked recently to increases in HIV, sexually transmitted infections, and Hepatitis B and C infections (Kidd et al., 2019), underscoring the importance of providing high-risk populations with evidence-based interventions aimed at reducing these health risks.

Evidence-based HIV education, prevention, and risk reduction interventions for people under community supervision are lacking and those that do exist do not reach many of those most in need of such services. A systematic review of HIV prevention for adults with criminal justice involvement (Underhill, Dumont, & Operario, 2014) identified seven trials conducted entirely in community settings that showed evidence of benefits in terms of self-reported reduction in sex or needle risk behavior or an increase in HIV testing, although no studies showed protective effects for both sex risk and needle risk. Programs included case management, one-on-one or group-based HIV education, integration of HIV prevention with medical checkups, or intimate partner violence intervention.

A systematic review of peer education for HIV prevention among high-risk groups—both criminal justice and non–criminal justice populations—(He et al., 2020) showed up to a 36% reduction in HIV infection rates, increases in HIV testing and condom use, and reduction in equipment sharing and unprotected sex. Another review of HIV prevention for individuals with intravenous and nonintravenous substance use (Elkbuli et al., 2019) showed that interventions used varying approaches, including counseling and education models, the Information-Motivation-Behavioral skills model, motivational interviewing, and peer-based education. Interventions were relatively brief, varying from one to seven sessions of 30 to 60 minutes each, which included individual, group-based, or both. Results of the interventions were mixed, with some studies reporting an increase in risky drug use or sex risk knowledge, as well as in motivational outcomes and for reductions of risky sex behaviors or risky drug use. Meyer et al. (2017) reviewed HIV interventions designed for women in the criminal justice system. Interventions included brief negotiation interviews, HIV education sessions in group or one-on-one formats ranging from single to multiple sessions, and strengths-based case management. Outcomes inlcuded increased HIV awareness, lower HIV sex risk behaviors, and increased seeking of HIV testing.

The reviews cited here report some evidence of effectiveness for a variety of HIV prevention and education programs using different approaches. In addition to these approaches, the use of technology, such as tablet apps, is rapidly emerging as a potentially effective way to address HIV risks among this high-risk population. According to Marsch et al. (2014), mobile technology has seen increasing use in linking people with services and providing some services such as brief interventions, behavior therapy, medication adherence tools, and HIV prevention interventions. Research has used a variety of approaches, including web-based platforms, mobile phones, videoconferencing, and telephone-based interactive voice response. For example, Bonar and colleagues (Bonar et al., 2014) compared three interventions in an emergency department sample of patients with past 3-month drug use. The study randomized participants to a brief intervention assisted by computer (BIAC) delivered by a master’s level therapist, a computerized brief intervention (CBI), and an enhanced usual care (EUC) condition (which included a 3-minute review of health resource brochures). Participants in the BIAC group increased confidence and intentions to cut down or quit using drugs compared to the EUC group. Additionally, participants receiving CBI demonstrated increased need for drug use help. A follow-up showed that the BIAC intervention reduced the number of days of using any drug compared to CBI (Blow et al., 2017), and BIAC with a booster was also associated with significant reductions in sexual risk scores over a 12-month follow-up compared to participants in the EUC group (Bonar et al., 2018).

Marsch, Guarino et al. (2014) found that replacing part of standard treatment with an interactive web-based behavioral intervention, the Therapeutic Education System (TES), increased rates of opioid abstinence for new clients entering a methadone clinic. TES utilizes the community reinforcement approach and cognitive behavioral therapy to establish new patterns of behavior that exclude substance use. The Therapeutic Education System, marketed by Pear Therapeutics as reSET (FDA, 2017), is the first mobile medical application to help treat substance use disorders.

The use of a web-based motivational interviewing tool, MAPIT (Walters et al., 2014), for linking people on probation to substance use treatment, was associated with higher initiation to treatment within two months when compared to the standard probation intake (Lerch et al., 2017). The use of electronic goal reminders is another technique that shows promise as a treatment aide; participants using this tool selected more goals than those who did not want reminders. Selecting reminders and the total number of goals was associated with fewer days of substance use and higher treatment attendance at the two-month follow-up (Spohr et al. 2015).

Many of these HIV education and risk reduction approaches were designed for non-justice-involved populations and require staff resources that are not always available in community supervision settings. Some of the challenges that staff and the individuals involved with the criminal justice system face include competing priorities between work and probation requirements and heavy caseloads among probation officers and case managers. Therefore, when implementing HIV education interventions, it seems important to have a technology-based intervention that will provide important and timely health education to clients without taking up substantial staff time. Additionally, such computerized interventions can offer privacy as well as provide individuals in the justice system with essential knowledge and resources in a confidential manner (Festinger et al., 2016).

For the current study we developed a multi-session, brief tablet app designed to improve decision-making around health risk behaviors that can reach the high-risk population of people with substance use disorders who are under community supervision. StaySafe is an intervention that staff can deliver in community probation waiting rooms while clients are waiting for appointments or in residential settings, requiring little staff time or training. To test the efficacy of StaySafe, we conducted a randomized clinical trial to test post-treatment outcome improvements in decision-making skills associated with reductions in health risk behaviors, especially those involving HIV and Hepatitis B or C (for more detail on StaySafe development and the research protocol, refer to Lehman et al., 2018).

1.1. Decision-making and analytically created schemas

StaySafe is based on cognitive processing models derived from analytically created schemas (ACS) and Texas Christian University (TCU) Mapping Enhanced Counseling (Dansereau, 2005; Dansereau & Simpson, 2009), which include experiential and analytic systems (Kahneman, 2011; Klacynski, 2005). Experiential systems reference previous experiences (Kahneman, 2011; Weber & Johnson, 2009) believed to be used in making decisions about risk behaviors because they are rapid and refer to familiar behaviors, even those with negative outcomes. Alternatively, analytic systems are typically slower because they often require conscious referencing and reinforcement. Schemas using the analytic system are created through repetition and practice.

The ACS approach can be a vehicle for organizing information through a series of steps and exercises that develop analytic thinking. Exhibiting options visually when developing plans and making decisions can contribute to an objective evaluation of available choices (Dansereau et al., 2013). Doing this can help individuals to monitor and control decision-making (metacognition), increase knowledge in specific areas (e.g., substance use, treatment initiation), and improve judgment and behavioral choices (self-regulation). Analytic repetition (similar to practice in athletic training) can develop procedural memory (i.e., skills and tasks that can be stored in long-term memory) that can be accessed rapidly. Individuals can use this process in real-life contexts rather than the more labor-intensive analytic processing. The Therapeutic Education System is a web-based intervention (Marsch, Guarino et al., 2014) and includes aspects of ACS in terms of helping participants establish and maintain new patterns of behavior and develop behaviors that do not involve substance use. When used in conjunction with reduced standard treatment, studies found outcomes to be associated with objective measures of greater rates of opioid abstinence. The Treatment Readiness Induction Program (TRIP) used ACS elements (including the WORKIT schema described in 1.4) in juvenile justice programs, and found increases in premeditation (thinking before committing an act) and improved decision-making in clients compared to a standard procedure group (Knight et al., 2015). Similarly, the goal of the StaySafe intervention is to replace or “override” inaccurate or maladaptive information, expectations, and behavior patterns with accurate health-related information and appropriate attitudes and behavioral choices.

1.2. WaySafe

The ACS-based StaySafe app grew out of WaySafe, a group-based curriculum that used an ACS approach to help people in prison-based substance use treatment make better decisions around health risk behaviors when they return to the community. The highly interactive WaySafe curriculum relies on mapping enhanced counseling to prepare individuals for re-entry by demonstrating interrelationships among constructs, including problem recognition, commitment to change, and strategies for avoiding behavioral health risks—key information for developing plans to address risky situations. Research has shown that, when compared to standard practice (SP), participants randomly assigned to WaySafe groups had greater improvements on knowledge and confidence measures related to HIV information and testing, avoiding risky sex and substance use, and risk reduction skills (Joe et al., 2019; Lehman et al., 2015; Lehman et al., 2019).

1.3. StaySafe

While results for WaySafe were promising, the field needed an intervention for people in the community, where the opportunity to engage in risky behavior is high. Based on the ideas of identifying risks and developing risk reduction plans from WaySafe, we adapted a schema called WORKIT that could be incorporated into a self-administered tablet app (StaySafe, described next) with accompanying health information facts to teach users to make systematic and informed decisions (Lehman et al., 2018). The StaySafe intervention includes 12 weekly sessions for participants to learn the WORKIT ACS through systematic repetition.

1.4. WORKIT

WORKIT, a major component of StaySafe, is a specific ACS schema that teaches a simplified structure for analyzing problems, weighing and rating options to make a decision, and then planning how to carry out that decision—What is the problem; Who is affected by the problem; Who can help with the problem; Options for dealing with the problem; Rating the options; Knowing what to do based on the ratings; Imagining steps to carry out the decision; and then Testing those steps. Several studies using WORKIT have shown improved decision-making, self-awareness, problem recognition, and indicators of treatment engagement (Becan et al., 2015; Knight et al., 2015, 2016).

1.5. Research goals

The current study utilized a randomized clinical trial to address three primary research goals around the StaySafe app: 1) to examine the participation rates of StaySafe sessions; 2) to test the effects of StaySafe on knowledge, confidence, and motivation around health risk behaviors and better decision-making skills; and 3) to assess of the relationship between greater StaySafe participation and greater pre-post change from baseline to postintervention.

2. Methods

2.1. StaySafe intervention

StaySafe includes twelve 10 minute self-administered sessions on a tablet; one session per week. Nine of the sessions involve the WORKIT ACS. The other three sessions, labeled Participant Choice, include several information-based activities around HIV and health risks, described below.

The first StaySafe session presents the participant with an overview of how to navigate through the StaySafe app, followed by a demonstration of a WORKIT exercise. Those sessions featuring WORKIT start with choosing from a list of 11 problem themes related to (1) people (e.g., “Asking a partner about his or her HIV testing”); (2) places (e.g., “Favorite high-risk places to hang out”); or (3) things (e.g., “Practicing safe sex”). The research team designed topics to be relevant for people under community supervision with substance use disorders, incorporating feedback from probation officers, substance use treatment counselors, clients on probation, and recommendations from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health on reducing health risks.

After choosing a topic (What is the problem?), the participant views a vignette showing actors working through a risky situation (vicarious learning), before proceeding through the rest of the WORKIT steps. Some of the WORKIT steps involve selecting from a list of possible responses to questions such as, “Who is affected by the decision?” or “Who can help with the problem?” For the WORKIT step, “Options for dealing with the problem”, participants select from a series of four options that are related to the chosen topic. For example, two of the options for the problem theme, “It’s hard to ask a partner about his or her HIV testing,” are “Don’t ask, but always use condoms,” and “Have unprotected sex just this one time.” Supporting health facts for each option “pop up” on the screen, thus embedding educational information within the decision-making schema. For other WORKIT steps, participants have to think about choices without making an explicit response. Mental practice such as this helps to prepare the participant for using the WORKIT schema in the “real world” and, therefore, provides an effective way to learn (Cooper et al., 2001). The goal is not to have participants solve specific problems during sessions, but to internalize the schema through repeated practice using relevant examples across multiple StaySafe sessions. A final activity in the WORKIT sessions is a “maze” game in which an animated character moves around a maze as participants answer quiz questions designed to reinforce information from the session.

Three Participant Choice sessions provide more in-depth information about HIV and health risks using three different activities (in each session): (1) a Center for Disease Control video giving information about HIV/AIDS, (2) HIV/AIDS facts coupled with a video discussion about HIV medication therapy or someone affected by HIV/AIDS talking about their experiences, and (3) the maze question game with additional HIV-related content. Participants chose one or more of the activities. Each of the Participant Choice sessions followed two WORKIT sessions in the weekly sequence, which provided for variation between tablet sessions.

2.2. Procedures

The study took place at five community supervision and corrections (probation) facilities in three large counties in Texas; these facilities included a community corrections location in one of the counties, a residential treatment center in one of the counties, and a community corrections location with two residential treatment centers in the third county. In the community-based facilities, recruiting materials included fliers, posters, and brief presentations at the beginning or end of orientation or group sessions; additionally, the research team spoke with individuals in waiting rooms about the study. TCU researchers conducted all recruiting. Eligibility criteria included being at least 18 years old, having at least six months of probation supervision remaining so they could complete the study, not being classified as a sex offender or convicted of a violent crime, not having a serious mental illness that could prevent participation in the study, having no pending charges that potentially would result in incarceration during the next six months, and having a sufficient reading level in English (fifth grade or higher) that would allow completion of the study. At the residential facilities, researchers provided a brief overview of the study to groups of new client admissions within a week of their arrival into the substance use treatment program.

Those interested in participating completed TCU IRB-approved informed consent and brief demographic forms. The research team then asked all participants to complete baseline surveys the following week. Community-based site participants also provided contact information for receiving meeting reminders about study data collection appointments. The study randomized participants into study conditions (i.e., StaySafe and SP arms) following completion of the baseline survey packet. The project utilized a permuted block randomization approach, with block size varying randomly among 2, 4, and 6. The study asked all participants to complete a postintervention survey three months after the baseline.

The study compensated participants in the form of payments toward their probation fees. Participants in community settings received $20 toward probation fees for completing the baseline survey and $40 for the postintervention survey. Compensation for the postintervention survey was higher to encourage participants to return for the survey session. The study compensated participants in residential settings $20 each for completing the baseline and postintervention surveys. In both settings, the study compensated participants in the StaySafe arms $10 for each StaySafe session completed.

2.2.1. Data collection.

Sources of data for the project included surveys and tablet data. Participants in both conditions completed surveys, and those in the StaySafe condition also contributed tablet data. In community facilities, researchers coordinated survey administration and tablet sessions with participants on the same day as their required community supervision activities (e.g., treatment groups and meetings with counselor or probation officer [PO]). A subset of individuals in the StaySafe arm, who had completed at least six tablet sessions, was also invited to interview with a senior member of the research team about the StaySafe experience. Qualitative results are reported in Pankow et al. (2019). For those in the community locations, study staff handed participants a scheduling card with the date/time of the next study activity and a contact number for the researcher in case of scheduling conflicts. In residential facilities, the research staff coordinated scheduling with program staff who provided the researcher with a list of available time slots when participants were free to complete study activities.

2.2.2. StaySafe sessions.

The team designed the 12-session StaySafe intervention to be administered one session per week for 12-weeks post consent. In cases where a participant missed a week, study staff administered two sessions in a single week. Participants completed sessions on a hand-held Android tablet, and participants could use headphones to listen as a narrator relayed the content of each tablet screen. Researchers utilized a tracking system (developed for the study) to coordinate data collection and manage the history of completed activities. A study identification number linked participant survey and tablet session data; the study did not record any identifiable information on the data sources. Other than completing the brief, weekly StaySafe sessions, participants followed the same probation schedules as did nonparticipants in both community and residential settings.

2.2.3. Standard practice.

The study asked participants in the SP arm to complete the baseline and postintervention surveys, but the study did not ask them to complete any StaySafe sessions. Other than the surveys, SP participants went about their normal business, attending probation meetings, groups, and other probation activities as normally scheduled. At the residential settings, SP participants followed their normal daily treatment schedule.

2.3. Data collection and measures

Research staff administered paper and pencil surveys at baseline before random assignment and again three months after baseline (postintervention). Outcome measures included the TCU Confidence & Motivation scales, and three decision-making scales—Rational Decision-Making, Dependent Decision-Making, and the TCU Decision-Making scale. The surveys also included demographic and background measures from the TCU Adult Risk Assessment (TCU A-RSK) form (IBR, 2008). Variables included age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, and, in the last six months before entering their current program: employment, public assistance, arrest status, on parole or probation, in jail or prison, and treatment for mental health, alcohol use, substance use, or treatment in an emergency room.

2.3.1. TCU Knowledge, Confidence, and Motivation scales (KCM).

Four scales included HIV Knowledge Confidence, Avoiding Risky Sex, HIV Services & Testing, and Risk Reduction Skills. Each of the scales, except for HIV Services & Testing, included items that assessed how knowledgeable (K) the participant felt about the topic, how confident (C) they were about their knowledge, and how motivated (M) they were to act on the knowledge. HIV Services & Testing included only knowledge and motivation items (Lehman et al., 2015). The study included knowledge, confidence, and motivation components for each scale in an overall score and examined them as separate subscales.

The TCU HIV Knowledge Confidence scale has 13 items (alpha = .93), and sample items include “You know enough to teach others what they should do if they think they have been exposed to HIV” (K), “You feel very confident that you could be a role model for others in helping reduce HIV risks” (C), and “You are totally committed to helping your friends and/or family avoid HIV/AIDS” (M). Coefficient alpha reliabilities for the three subscales ranged from .75 to .88.

The TCU Avoiding Risky Sex scale has 13 items (alpha = .93 and ranged from .81 to .84 for the three subscales) and includes items such as “During the past month, you have learned about what situations might lead you to make a poor decision about risky sex” (K), “During the past month, your confidence in managing emotions in sexual situations in the real world has increased” (C), and “During the past month, you have become more motivated to protect your sexual partner from HIV risk in the real world” (M).

The TCU HIV Services & Testing scale consists of seven items (alpha = .81 for the full scale; .62 to .79 for the knowledge and motivation subscales, respectively). Sample items include “During the past month, you have become more knowledgeable about how to get HIV services in the real world” (K) and “You will get tested for HIV if you think that you might have been exposed” (M).

The TCU Risk Reduction Skills scale comprises 14 items (alpha = .91,ranging from .65 to .82 for the three subscales) and includes items such as “During the past month, you have a better understanding of how your shoulds and wants can conflict in the real world” (K), “During the past month, you have become more confident in balancing your shoulds and wants in the real world” (C), and “During the past month, your motivation to avoid personal HIV risks in the real world has increased” (M).

All items for the TCU Confidence & Motivation scales use a 5-point Likert-type response scale ranging from 1=Disagree Strongly to 5=Agree Strongly. We reflected items worded in the opposite direction from the scale construct by subtracting the score from 6. Study staff then computed scale scores by calculating the average score for items within the scale then multiplying the average score by 10 to obtain a range from 10 to 50. Scores above 30 indicated at least some agreement with the scale construct and scores below 30 indicated at least some disagreement.

2.3.2. Decision-Making (DM) scales.

The study used scales measuring three decision-making styles, including Rational Decision-Making Style (Rational DM), Dependent Decision-Making Style (Dependent DM), and the TCU Client Evaluation of Self and Treatment (CEST) Decision-Making scale (TCU-DM). We adapted both the Rational and Dependent Decision-Making Style scales from Scott & Bruce (1995). The Rational DM scale consists of five items (alpha = .84), including “I make decisions in a logical and systematic way” and “I explore all of my options before making a decision.” This scale is relevant for the “O” in the WORKIT schema and involves exploring options for a problem. Dependent DM scale has five items (alpha = .79) with statements such as, “I often need the assistance of other people when making important decisions” and “I rarely make important decisions without consulting other people.” This scale is relevant for the “W” component of WORKIT (who will be affected and who can help with a problem). The TCU DM scale has nine items (alpha = .79). Representative items include “You plan ahead,” You think about what causes your current problems,” and “You think of several different ways to solve a problem.” This scale represents a more general view of decision-making.

2.3.3. Talk outcomes.

Part of the WORKIT schema is identifying who can help with a problem, which then encourages talking with others about the problem. The study team created talk variables from a series of 12 questions created for this study that asked about whether the individual talked to their probation officer, counselor, friend/trusted advisor, or family member about better decision-making, HIV risks, and HIV prevention/treatment. The dependent variables were dichotomies of whether talk occurred with that person(s) or addressed that subject matter.

2.3.4. Getting tested.

We asked how many times the participant had been tested for HIV, a sexually transmitted infection, or hepatitis B or C in the past year (at baseline) and at postintervention.

2.4. Analytical approach

The study conducted three primary sets of analyses. In the first set, we report characteristics of the research sample and StaySafe participation, in terms of the number of sessions completed by the StaySafe group. The study conducted a second set of analyses comparing the StaySafe and SP groups on baseline and postintervention measures using SAS Proc GLM separately for the community and residential samples. The study first compared the StaySafe and SP groups on demographic and background variables and then on baseline measures of the outcome variables to check for group equivalence using chi-square statistics for dichotomous and categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables. The study conducted attrition analyses by comparing participants who completed baseline and postintervention measures with participants who completed a baseline survey but not a postintervention survey on demographic and background variables using chi-square and t-tests.

The study then compared the StaySafe and SP groups on outcome variables from the postintervention surveys using the appropriate baseline measure as a covariate. Research staff computed effect sizes (Cohen’s d) for each outcome measure by taking the difference between least-square means of the StaySafe and SP groups and then dividing by the standard deviation of the SP group (Cohen, 1988). The study examined the impact of missing data on the analyses by running 100 multiple imputations (MI) using SAS Proc MI for outcomes in which there were significant differences between StaySafe and SP groups. In the MI estimation process, the study designated the fully conditional specification method (FCS) with the discriminant function method used for the imputation method (DISCRIM). Additionally, the study specified the pattern-mixture model approach, assuming the missing data are missing not at random (MNAR), for imputing the missing values.

3. Results

3.1. Sample

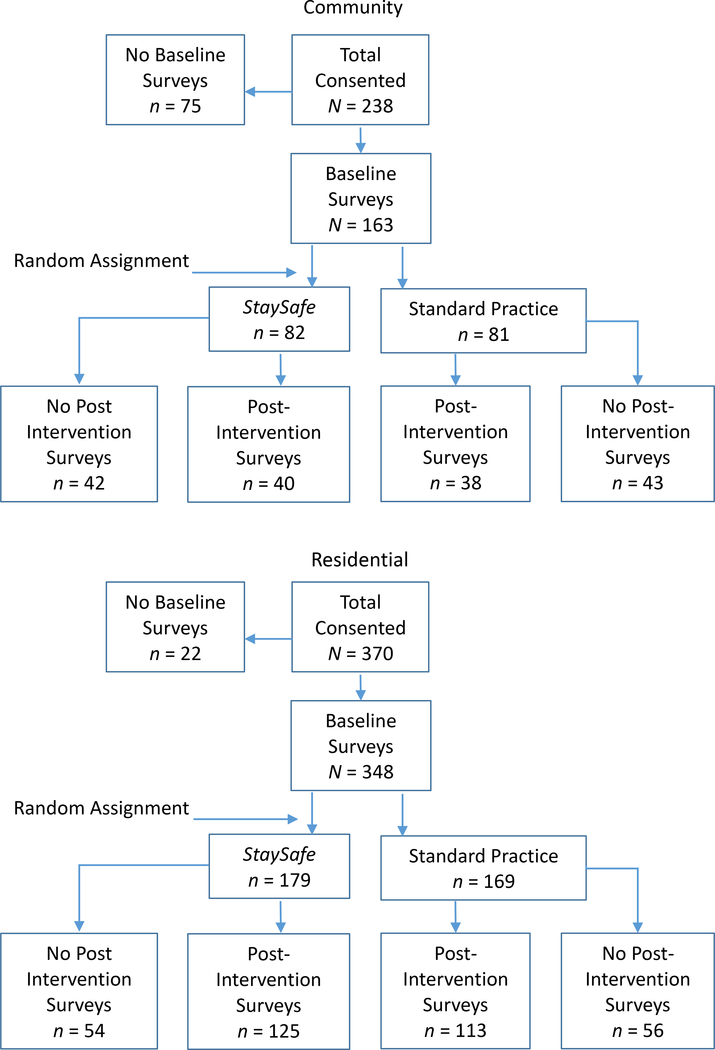

Figure 1 shows a consort diagram. In the two community facilities, 238 participants completed informed consent procedures, and 163 completed baseline surveys. Of these, the study randomly assigned 82 to the StaySafe arm and 81 to the SP arm; 40 StaySafe and 38 SP participants completed a postintervention survey. In the three residential facilities, 370 participants completed informed consent procedures, and 348 completed baseline surveys. Of these, the study randomly assigned 179 to the StaySafe arm and 169 to the SP arm; 125 StaySafe and 113 SP participants completed postintervention surveys.

Figure 1.

Consort diagram.

Table 1 shows sample characteristics. In the community sample, 56% were male and 44% female. About half of the sample (49%) were African American and 40% White; 28% identified as Hispanic. Most participants were between the ages of 21 and 39 (68%). About 78% had a high school (HS) diploma, with 42% having some education past high school (HS). The majority were single (61%). In the six months before entering the current program, 58% were employed full time; 26% were neither employed nor looking for employment; 39% were on public assistance; and more than 60% had been arrested, on parole, or probation, and/or in jail or prison. At least 20% reported treatment for mental health, alcohol or substance use, or treatment in an emergency room.

Table 1:

Sample characteristics.

| Community | Residential | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| SP n = 81 |

StaySafe n = 82 |

Total N = 163 |

SP n = 169 |

StaySafe n = 179 |

Total N = 348 |

|

|

| ||||||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 60.5% | 52.4% | 56.4% | 52.1% | 45.8% | 48.9% |

| Female | 39.5% | 47.6% | 43.6% | 47.9% | 54.2% | 51.1% |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 39.2% | 41.3% | 40.3% | 27.2% | 30.3% | 28.8% |

| African American | 54.4% | 43.8% | 49.1% | 65.1% | 57.9% | 61.4% |

| Other | 6.3% | 15.0% | 10.7% | 7.7% | 11.8% | 9.8% |

| Hispanic | 29.6% | 26.8% | 28.2% | 33.1% | 32.8% | 32.9% |

| Age | ||||||

| 18–20 | 5.0% | 5.2% | 5.1% | 7.8% | 5.3% | 6.5% |

| 21–29 | 38.8% | 29.9% | 34.4% | 34.9% | 32.2% | 33.5% |

| 30–39 | 31.3% | 35.1% | 33.1% | 34.3% | 36.8% | 35.6% |

| 41–49 | 13.8% | 13.0% | 13.4% | 14.5% | 16.4% | 15.4% |

| ≥ 50 | 11.3% | 16.9% | 14.0% | 8.4% | 9.4% | 8.9% |

| Education | ||||||

| < HS diploma | 22.5% | 22.0% | 22.2% | 42.9% | 33.0% | 37.8% |

| HS diploma | 38.8% | 32.9% | 35.8% | 34.5% | 41.3% | 38.0% |

| > HS diploma | 38.8% | 45.1% | 42.0% | 22.6% | 25.7% | 24.2% |

| Marital Status | ||||||

| Single | 65.4% | 56.1% | 60.7% | 56.9% | 54.7% | 55.8% |

| Married | 11.1% | 20.7% | 16.0% | 16.8% | 24.0% | 20.5% |

| Divorced/separated | 23.5% | 23.2% | 23.3% | 26.3% | 21.2% | 23.7% |

| Last six months (% yes)-- | ||||||

| employed full time | 55.7% | 59.3% | 57.5% | 49.4% | 48.6% | 49.0% |

| unemployed/not looking | 24.1% | 27.8% | 25.9% | 33.9% | 39.6% | 36.8% |

| on public assistance | 32.5% | 46.3% | 39.4% | 24.1% | 28.4% | 26.3% |

| arrested | 63.0% | 57.5% | 60.2% | 65.5% | 74.7% | 70.3% |

| parole or probation | 80.2% | 78.8% | 79.5% | 62.7% | 65.1% | 63.9% |

| jail or prison | 64.2% | 63.8% | 64.0% | 59.4% | 71.2% | 65.5%* |

| treated in emergency room | 37.0% | 35.8% | 36.4% | 28.7% | 33.9% | 31.4% |

| treated for mental health | 28.4% | 24.7% | 26.5% | 30.4% | 25.8% | 28.0% |

| treated for alcohol use | 18.5% | 22.2% | 20.4% | 10.7% | 12.4% | 11.6% |

| treated for illegal drug use | 29.6% | 35.8% | 32.7% | 32.7% | 36.5% | 34.7% |

P < .05

In the residential sample, 49% were male and 51% female. More than half of the sample (61%) were African American and 29% White; 33% identified as Hispanic. Most participants were between the ages of 21 and 39 (69%). About 62% had a HS diploma, with 24% having some education past HS. The majority were single (56%). In the six months before entering the current program, 49% were employed full time, and 37% were neither employed nor looking for employment; 26% were on public assistance, and more than 64% had been arrested, on parole, or probation, and/or in jail or prison. At least 28% reported treatment for mental health, substance use, or in an emergency room, and 12% for alcohol use.

3.2. Pre-test comparisons

To check for equivalence of the StaySafe and SP participants, the study compared the two groups on the baseline demographic and background and outcome variables using contingency table analyses for dichotomous and categorical variables (chi-square tests) and t-tests for continuous variables. The only significant difference was in the residential sample, in which the StaySafe arm had a higher percentage of participants who spent time in jail or prison prior to entering the current program (71%) than did the SP arm (59%).

3.3. Attrition analyses

To examine the impact of participant attrition on the final analysis sample (those who completed baseline and postintervention surveys), the study compared participants who had completed baseline and postintervention surveys with those who did not complete a postintervention survey (noncompleters) on the demographic and background variables shown in Table 1 and on the outcome measures at baseline using contingency table analyses and t-tests where appropriate. As described, just over 50% of the community sample did not complete a postintervention survey versus 32% of the residential sample.

In the community sample, participants who did not complete a postintervention survey, compared to those who did, were younger (32 years old vs 38), were more likely to be single (71% vs 50%), and were less likely to have been treated for alcohol use problems in the six months before entering the current program (13% vs 28%). In the residential sample, participants who did not complete a postintervention survey were less likely to have been employed full time in the previous six months (40% vs 53%) and less likely to have been on probation or parole (52% vs 69%). Participants who did not complete a postintervention survey also had lower scores at baseline on most of the outcome measures, including HIV Knowledge Confidence (and the Knowledge and Confidence subscales), the Knowledge subscale for Avoiding Risky Sex, HIV Services & Testing (and the Knowledge and Motivation subscales), Risk Reduction (and the Knowledge, Confidence and Motivation subscales), and on Rational DM and the TCU DM scale.

The study also compared the SP and StaySafe arms among noncompleters to see if there was differential attrition between the two arms. The study found no differences for any variables (demographic and background and outcome measures at baseline) for the community sample. In the residential sample, noncompleters in the StaySafe arm were more likely than those in the SP arm to have had treatment for alcohol problems in the six months before the current program (16% vs 4%).

3.4. StaySafe participation

One of the study’s primary goals was to examine to what extent people under community supervision would complete StaySafe sessions. We provide a summary of StaySafe participation in Table 2, which shows that people in the study were willing to complete multiple sessions. Although StaySafe completion was lower in the community sample than in the residential sample, community participants averaged more than seven completed sessions. Participants in the residential sample averaged more than 10 completed sessions.

Table 2:

StaySafe participation.

| # of Sessions Completed | Community (n = 82) | Residential (n = 179) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| 1 or more (n) | 98% (80) | 94% (168) |

| 6 or more | 65% (53) | 83% (148) |

| 12 | 28% (23) | 50% (90) |

| Average | 7.3 | 10.1 |

3.5. Postintervention comparisons (three months after baseline)

The study compared participants in the StaySafe arm and those in the SP arm on postintervention measures reflecting knowledge, confidence, and motivation around key areas related to the StaySafe content (HIV Knowledge Confidence, Avoiding Risky Sex, HIV Services & Testing, and Risk Reduction Skills), several aspects of decision-making, talk outcomes, and getting tested. The study included the corresponding baseline measure as a covariate in the analysis of that postintervention measure (except for the talk outcomes, which we did not measure at baseline). The research team also computed effect sizes (ES) using Cohen’s D for each postintervention comparison. Table 3 shows the results for the KCM and decision-making scales.

Table 3:

StaySafe postintervention.

| Community | Residential | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| SP n = 38 |

StaySafe n = 40 |

prob | Effect Size | SP n = 113 |

StaySafe n = 125 |

prob | Effect Size | |

|

| ||||||||

| HIV Knowledge Confidence | 39.3 | 42.0 | 0.038 | 0.48 | 41.0 | 43.2 | <.001 | 0.47 |

| Knowledge | 39.7 | 43.4 | 0.021 | 0.53 | 41.4 | 43.8 | 0.002 | 0.41 |

| Confidence | 39.7 | 41.8 | 0.167 | 0.32 | 40.3 | 43.5 | <.001 | 0.60 |

| Motivation | 38.8 | 40.9 | 0.105 | 0.37 | 41.2 | 42.4 | 0.068 | 0.24 |

| Avoiding Risky Sex | 39.8 | 41.9 | 0.139 | 0.34 | 42.0 | 43.4 | 0.021 | 0.30 |

| Knowledge | 39.9 | 42.0 | 0.241 | 0.27 | 42.2 | 44.2 | 0.004 | 0.38 |

| Confidence | 39.0 | 41.4 | 0.131 | 0.35 | 41.2 | 42.1 | 0.176 | 0.18 |

| Motivation | 40.2 | 42.3 | 0.161 | 0.32 | 42.4 | 43.7 | 0.052 | 0.25 |

| HIV Services & Testing | 40.5 | 43.0 | 0.055 | 0.44 | 42.6 | 44.8 | <.001 | 0.50 |

| Knowledge | 37.4 | 42.5 | 0.003 | 0.69 | 41.4 | 44.9 | <.001 | 0.61 |

| Motivation | 42.8 | 43.3 | 0.659 | 0.10 | 43.6 | 44.7 | 0.072 | 0.23 |

| Risk Reduction Skills | 42.3 | 43.4 | 0.375 | 0.20 | 43.2 | 44.6 | 0.009 | 0.34 |

| Knowledge | 42.1 | 43.5 | 0.292 | 0.24 | 43.1 | 44.4 | 0.032 | 0.28 |

| Confidence | 41.1 | 42.7 | 0.182 | 0.30 | 41.9 | 44.1 | <.001 | 0.47 |

| Motivation | 43.6 | 43.8 | 0.908 | 0.03 | 44.3 | 45.2 | 0.145 | 0.19 |

| Decision-Making | ||||||||

| Rational | 4.35 | 4.26 | 0.482 | −0.16 | 4.26 | 4.38 | 0.043 | 0.26 |

| Dependent | 3.38 | 3.11 | 0.168 | −0.31 | 3.55 | 3.69 | 0.158 | 0.18 |

| TCU DM scale | 3.98 | 4.04 | 0.616 | 0.11 | 3.84 | 3.95 | 0.059 | 0.25 |

In the community sample, StaySafe participants had significantly higher scores than did SP participants at postintervention on HIV Knowledge Confidence (M = 42.0 vs 39.3; ES = .48) and on the Knowledge subscale (43.4 vs 39.7; ES = .53). StaySafe participants also had significantly higher scores on the Knowledge subscale for HIV Services & Testing (42.5 vs 37.4; ES = .69). The study also found differences for the full scale for HIV Services & Testing (43.0 vs 40.5; ES = .44), although the probability level was just over the .05 cutoff (p = .055). Even though group differences on other measures did not reach statistical significance, potentially due to low power based on the relatively small sample size (n = 78), the trend on all of the KCM measures showed the StaySafe group having higher postintervention scores on all scales and subscales. Effect sizes for the scales were typically in the small to medium range (.20 to .69), with most of the scales and subscales for HIV knowledge confidence, avoiding risky sex, and hiv services & testing greater than .30. The study did not find any significant group differences on the decision-making scales.

In the residential sample, the study found significant differences for all the KCM scales and most of the subscales. StaySafe participants had significantly higher scores than did SP participants on HIV knowledge confidence (43.2 vs 41.0; ES = .47), avoiding risky sex (43.4 vs 42.0; ES = .30), HIV services & testing (44.8 vs 42.6; ES = .50), and risk reduction skills (44.6 vs 43.2; ES = .34). The knowledge subscales were significant for all four measures (effect sizes ranging from .28 to .61) and the confidence subscale for HIV knowledge confidence and risk reduction skills (effect sizes of .60 and .47, respectively). The StaySafe group also had a significantly higher score on the rational decision-making scale (4.38 vs 4.26; ES = .26) than did the SP group.

3.6. Talk outcomes

The study examined talk outcomes comparing the SP condition with StaySafe participants who completed fewer than the full 12 sessions and those who completed all 12 sessions. Although the study conducted analyses for the community and residential samples, we report only the community samples here, as individuals in the residential sample generally did not have many opportunities to talk with others outside of the residential setting; a likely contributing factor to the lack of significant findings in the residential sample. We show results for the talk variables in Table 4. Post hoc tests of simple effects generally showed that for participants in the StaySafe arm, completing all 12 sessions was associated with a higher likelihood to talk with others about making better decisions, HIV risks, and HIV prevention/treatment than for participants who completed fewer than 12 sessions. However, participants in the SP arm were more likely than people in the StaySafe arm to talk about making better decisions; SP participants and StaySafe participants who did not complete all 12 sessions did not generally differ in their propensity to talk with others about HIV risks and HIV prevention/treatment.

Table 4:

Talk outcomes for the community sample.

| SP (n = 38) LS Mean (SE) |

StaySafe < 12 completed sessions (n = 17) LS Mean (SE) |

StaySafe 12 completed sessions (n = 23) LS Mean (SE) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Talk – Decision-Making Overall test: (F(1,306) = 21.66, p <.0001) |

1.024 (0.035) | 0.783 (0.041) | 0.985 (0.040) |

| Talk – HIV Risks Overall test: (F(1,306) = 2.46, p <.087) |

0.263 (0.079) | 0.235 (0.1180) | 0.522 (0.102) |

| Talk – HIV Prevention/Treatment Overall test= (F(1,306) = 4.70, p <.0098) |

0.237 (0.079) | 0.235 (0.119) | 0.609 (0.102) |

3.7. Getting tested

The study compared questions on getting tested for HIV, sexually transmitted infections, or Hepatitis B or C only in the community sample as those in residential settings did not have sufficient opportunities to get tested. There were not any differences between the StaySafe and SP arms in the community sample on getting tested (potentially due in part to the small sample size in the community sample).

3.8. Multiple imputations for StaySafe significant outcomes

A large amount of missing data represented a validity concern for the results of the study. To address this, the research team did a series of 100 multiple imputations using SAS Proc MI for each of the 14 outcomes for which we found significant results in the previously reported analyses (three for the community-based sample and 11 for the residential-based sample). In these multiple imputations, the team also decided to address possible site differences through the use of a nested model by performing SAS Proc Mixed. The multiple imputations for the 14 outcomes supported the results of those previously noted in the study. For example, for the community sample, the three significant variables were HIV knowledge (overall), HIV knowledge, and HIV services knowledge, and the number of significant multiple imputation tests ranged from 87 to 98 out of 100 tests. For the residential sample, 11 outcomes were significant (see Table 3), and the number of significant multiple imputation tests ranged from 72 to 100 out of 100 tests (between 98 and 100 out of 100 tests for 8 of the outcomes).

3.9. StaySafe participation and change in outcomes

The study’s final research goal was to examine the relationship between the number of StaySafe sessions completed and the amount of pre-post change in the outcome variables (KCM scales, and Decision-Making). These analyses could include only participants in the StaySafe arm and involved correlations of the number of completed StaySafe sessions with pre-post change scores. We show results in Table 5, which generally demonstrate that completing more StaySafe sessions was associated with a greater change from baseline to postintervention.

Table 5:

Correlations of StaySafe sessions completed with change in outcome variables.

| Community (n = 40) |

Residential (n = 125) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corr | prob | Corr | prob | |

|

| ||||

| HIV Knowledge Confidence | 0.194 | 0.231 | 0.193 | 0.032 |

| Knowledge | 0.303 | 0.057 | 0.139 | 0.126 |

| Confidence | 0.052 | 0.752 | 0.177 | 0.050 |

| Motivation | 0.142 | 0.382 | 0.167 | 0.064 |

| Avoiding Risky Sex | 0.332 | 0.036 | 0.162 | 0.073 |

| Knowledge | 0.259 | 0.107 | 0.075 | 0.412 |

| Confidence | 0.402 | 0.010 | 0.169 | 0.061 |

| Motivation | 0.279 | 0.081 | 0.183 | 0.043 |

| HIV Services & Testing | 0.299 | 0.061 | 0.185 | 0.041 |

| Knowledge | 0.308 | 0.053 | 0.154 | 0.090 |

| Motivation | 0.241 | 0.135 | 0.165 | 0.068 |

| Risk Reduction Skills | 0.122 | 0.455 | 0.221 | 0.014 |

| Knowledge | 0.058 | 0.725 | 0.224 | 0.013 |

| Confidence | −0.047 | 0.773 | 0.094 | 0.304 |

| Motivation | 0.241 | 0.134 | 0.245 | 0.006 |

| Decision-Making | ||||

| Rational | −0.008 | 0.962 | 0.229 | 0.011 |

| Dependent | −0.127 | 0.436 | 0.048 | 0.596 |

| TCU DM scale | 0.162 | 0.319 | 0.080 | 0.377 |

In the community sample, 40 participants in the StaySafe arm completed baseline and postintervention surveys. The study found significant correlations (p < .05) for only avoiding risky sex (r = .332) and for the confidence subscale (r = .402). However, due to the small sample size, power for this sample was limited, and the study found other correlations to have p-values of less than .10, including the knowledge subscale of HIV knowledge confidence (r = .303), the motivation subscale of avoiding risky sex (r = .279), HIV services & testing (r = .299) and its knowledge subscale (r = .308).

A greater number of significant correlations existed in the residential sample than in the community sample due in part to the much larger sample size. A total of 125 residential participants in the StaySafe arm completed baseline and postintervention surveys. We should note that all the participants who completed a postintervention survey completed at least six StaySafe sessions. StaySafe participation was significantly correlated with all four of the KCM outcome domains including HIV knowledge confidence (r = .193) and the confidence subscale (r = .177), with the avoiding risky sex motivation subscale (r = .183), with HIV services & testing (r = .185), with risk reduction skills (r = .221) and its knowledge (r = .224) and motivation subscales (r = .245). Also, StaySafe completions positively correlated with changes in rational decision-making (r = .229). The influence of sample size is seen in the avoiding risky sex and HIV services & testing scales, where the correlations in the community sample were larger (nonsignificant) than in the residential sample (significant).

4. Discussion

The study administered a multisession tablet-based intervention to improve decision-making around health risk behaviors, titled StaySafe, in community and residential probation settings in three large counties in Texas. The study team administered StaySafe within agency facilities to determine whether probation settings were an appropriate location to be efficient and administer the multisession intervention when people were waiting for group sessions or individual appointments. The current research study’s goals were first to examine participation levels in an intervention that was designed for 12 brief weekly sessions, and second to assess changes in knowledge, confidence, and motivation as a result of StaySafe participation. Results showed that participants from both community and residential settings who were in the StaySafe research arm were willing to complete multiple StaySafe sessions, and had improved knowledge, confidence, and motivation around avoiding risky health behaviors compared to those in the SP arm. Furthermore, completing a greater number of StaySafe sessions correlated positively with greater improvements in knowledge, confidence, and motivation measures from baseline to follow-up, and completion of all 12 StaySafe sessions was associated with a higher likelihood of talking about decision-making, talking about HIV risks, and talking about HIV prevention/treatment with others (e.g., family, friends, counselors, probation officers).

4.1. Stay Safe participation: Community vs residential

Although participants in both community and residential settings completed multiple StaySafe sessions (average 7.3 and 10.1, respectively), important differences existed between the modalities. The residential treatment programs were typically 6 months and thus participants were generally readily accessible to complete surveys and weekly StaySafe sessions if the sessions did not conflict with scheduled meetings, groups, or other program activities. Missed StaySafe sessions occurred when participants were away from the facility for medical or other appointments, when participants were sent back to jail, or when participants absconded from the facility. The latter reason is important, as one of the two residential programs was an unsecured facility and up to 25% of its residents violated their supervision requirements by walking away.

The community settings raised several different challenges not present in the residential settings. The study team scheduled StaySafe sessions and other project activities around meetings that participants had at the community facility, including group and individual counseling sessions and meetings with supervising officers. The team scheduled StaySafe sessions immediately before or after these meetings. However, participants often did not arrive at the facility early enough to complete sessions or were unable to stay after scheduled meetings due to transportation issues or work schedules. Meeting schedules for community participants changed frequently, and they sometimes transferred to other facilities. The research team addressed absenteeism issues (when possible) with text messages, phone calls, and emails to reschedule missed sessions. However, phone numbers frequently changed or did not work, or participants used phone numbers from family or friends and these messages were not always forwarded. Thus, although participants were willing to complete multiple StaySafe sessions and frequently commented how much they enjoyed the sessions and found them helpful, transportation, scheduling, and communication challenges in the community sample limited participation rates across the time required for StaySafe.

High levels of attrition are common in community supervision populations. A meta-analysis of more than 100 offender treatment attrition studies found an average of 27% attrition and even higher numbers when the study considered preprogram attrition (Olver et al., 2011). Crisante et al. (2014) reported attrition rates of 33% and 52% at 6 and 12 months postbaseline in a sample from police diversion programs with higher attrition rates associated with drug offenses and community supervision. These high rates are not inconsistent with our results given the additional factors in our study related to maintaining contact with participants. For a more detailed discussion of these and other issues related to participation and attrition, please see Muiruri et al. (2021).

Many of the challenges regarding scheduling and communication are specific to the needs of a research project requiring completely voluntary participation, which prevented us from using probation staff to help contact participants so that there was no appearance of coercion. If an intervention like StaySafe were administered as part of a treatment program or by probation personnel, scheduling and communication issues are likely to be minimized, resulting in higher participation rates. The development of a smartphone version of StaySafe that could be completed away from probation offices may also increase participation and fits within the trend during the COVID-19 pandemic of increased use of virtual appointments and services. A smartphone version is planned for future projects.

4.2. Outcomes

Although challenges arose in maintaining the study sample in the community settings, results showed positive changes in knowledge, confidence, and motivation around avoiding health risk behaviors for participants in the StaySafe arm of the study compared to those in the SP arm in both the community and residential settings. Differences between the SP and StaySafe groups were more likely to be statistically significant for the residential than for the community sample. Several factors likely contributed to this. One such factor is the larger sample size and thus greater power for the outcome analyses in the residential sample (n=238) compared to the community sample (n=78). Indeed, effect sizes were generally similar for the two samples. One issue contributing to this size discrepancy was greater levels of missing data in the community sample. To address this, we performed a series of 100 multiple imputations for each significant outcome, and the results of the multiple imputations supported the significance of the outcome analyses.

Another factor might be that participants in the residential sample received higher doses of StaySafe by completing more sessions than did those in the community sample. An important premise behind the WORKIT ACS is that repeated analytical practice helps to create “procedural memory” that individuals can access more rapidly and, thus, use more in real-world settings. The finding that the number of completed StaySafe sessions correlated positively with the level of pre-post change supports the notion that higher dosage and practice opportunities of StaySafe are more effective.

A third factor might be other conflicting priorities. Participants in community settings often have many demands, including multiple meetings at the probation facility for groups or individual meetings with counselors or supervision officers, and often deal with transportation issues, and job and family demands. Although the study staff administered StaySafe during times when participants were faced with many important decisions around their health risk behaviors, the impact of StaySafe may be diminished for some community participants, given the other competing demands on their lives. Alternately, perhaps fewer conflicting demands existed for participants in residential settings other than maintaining a busy schedule of group and individual meetings, although residential clients also have work assignments and must deal with other clients 24/7 who are housed together. StaySafe is consistent with many of the lessons being taught in residential settings, and participants can attend to the StaySafe lessons without many of the conflicting demands of those in the community.

A fourth factor might be the definition of the risk between treatment settings. The meaning of outcome measures including decision-making skills and knowledge, confidence, and motivation around HIV risks may differ between the community and residential settings due to the confined nature of the residential setting. In residential settings, some participants reported that they did not have opportunities to use the lessons learned from StaySafe, and HIV risks may not have been an immediate concern. Thus, the motivation to act on HIV risks while in the residential setting may not appear relevant until the participants are back in the community as evidenced by the low effect sizes for the motivation scales in the residential sample. However, even in residential settings, participants make behavioral decisions on how to interact with other residents or their counselors; these interactions provide opportunities to implement and practice lessons from StaySafe in an environment with few distractions.

In addition to the differences between the community and residential samples, differences existed in statistical significance and effect sizes for both samples between the knowledge, confidence, and motivation measures across the different domains (HIV knowledge, avoiding risky sex, HIV services and testing, and risk reduction), and also between the different domains. That is, the knowledge component was the only subscale significant in the community sample and the knowledge and confidence components in the residential sample. The motivation component was not significant for any of the four domains in either of the samples and tended to have smaller effect sizes. That the knowledge component showed more frequent differences is not surprising. The content in the StaySafe sessions included facts about HIV, prevention, and risk reduction linked to various steps in the WORKIT schema, and linking the knowledge components to the decision-making schema may have made the knowledge more relevant and accessible. Increased awareness was one of two major themes merging from qualitative analyses of follow-up interviews. The WORKIT ACS was then expected to increase confidence in the ability to act on that knowledge due to the structure it provided for making decisions. However, WORKIT did not as directly address the motivation to act on the knowledge.

The study also found differences in effect sizes among the four domains of HIV knowledge, avoiding risky sex, HIV testing and services, and risk reduction. Some of these differences could be a function of the content of the knowledge curriculum within StaySafe that focused on HIV knowledge and getting tested perhaps more so than avoiding specific risky sex behaviors. In addition, getting tested or seeking services is a more concrete outcome than avoiding risky sex or general risk reduction, which involves more complex decisions. To better address these issues, those administering StaySafe can easily adapt the content to emphasize different knowledge areas.

The quantitative results on positive change after StaySafe were supported by a qualitative analysis conducted on semi-structured interviews with 17 participants who had completed at least six StaySafe sessions and reported by Pankow et al. (2018; 2019). Participants answered questions such as their overall feeling about using StaySafe, how they have used WORKIT in their everyday life, if StaySafe has helped them to change some behaviors, plans to use StaySafe in the future, and the top thing learned from StaySafe. Study staff recorded, transcribed, and coded responses using a 2-stage approach. Two major themes from the analyses included StaySafe components that raised awareness and those that related to problem-solving, both of which can lead to behavior regulation (Baumeister & Vonasch, 2015). The most prominent components were related to decision-making strategies and health information. Participants reported increased awareness of HIV information and health risks, increased motivation for HIV testing, thinking about problems more logically, and using WORKIT problem-solving strategies to change their everyday behaviors such as acting less impulsively and interacting with others.

4.3. Implications

StaySafe was developed to help fill in HIV prevention gaps in community supervision populations where education and prevention are often limited or lacking. Existing interventions often require trained staff to provide education services around HIV risks, and allocating sufficient time and staffing resources to participate in required training can be challenging. StaySafe is brief, self-administered, and can be implemented by staff with minimal training and effort. Participants can complete the brief StaySafe sessions while waiting for appointments and the use of role-play videos, interactive curriculum, and some game elements helps with client engagement. Results of this study support this notion, as individuals under supervision in both community and residential settings completed multiple StaySafe sessions and reported high levels of engagement and satisfaction. Results also demonstrated the benefit of completing multiple sessions across several months, providing important repetition of the WORKIT schema, which is a critical part of StaySafe. Furthermore, because StaySafe is self-administered on a tablet, it allowed participants to work through sensitive issues that they may initially be reluctant to discuss directly with counselors or supervising officers. The development of a smartphone version that participants could use and access on their own may be even more helpful for increasing the reach of the intervention and is a goal for future studies.

Content in StaySafe for this study focused on health risk behaviors and information around HIV and getting tested for HIV. However, the StaySafe platform can be readily used for other content areas. For example, a previously developed version focused on women’s reproductive health issues (Pankow & Lehman, 2018). This new version was made possible with the development of a companion program (KeepSafe), which is a text-based module that allows text, audio, graphics, pictures, and videos to be easily changed without the need for reprogramming.

4.4. Limitations

Some limitations could influence the generalizability of the findings from this study. For example, although study sites included both community and residential substance use treatment, the number of each was limited. Furthermore, while many similarities existed between participants in these two settings (e.g., mandated substance use treatment), health risks for those in a residential setting may differ from those faced by individuals completing their supervision in a community setting. As such, measures to gauge motivation for HIV testing may not be equivalent in community and residential samples. Another limitation is the absence of behavioral tests and measures to validate self-reports; thus, future studies should incorporate HIV testing data when interpreting participant motivation and its contribution as a risk reduction strategy.

An additional limitation is that participants in both community and residential settings were compensated $10 toward probation fees for their time completing StaySafe sessions. Paying people to complete sessions is not generally a sustainable model; although, as part of a research project in which participation is completely voluntary, it is often necessary to get adequate participation. However, outside of a research project, other motivations may help to increase participation. Probation officers can require completion of sessions as part of probation activities and treatment programs can include StaySafe as part of the treatment regimen.

4.5. Conclusions

A brief multi-session, tablet-based decision-making app appears to be a useful tool for helping people under community supervision improve their knowledge, confidence, and motivation for making better decisions around health risk behaviors in both residential and community settings. Although completion rates differed between settings (residential participants completed more StaySafe sessions than those in community settings), results show significant potential for StaySafe to be a useful tool in residential and community probation settings.

HIGHLIGHTS.

StaySafe is a tablet app developed to improve health risk decision-making

People under community supervision volunteered to complete multiple, brief StaySafe sessions

StaySafe participants reported improvements in attitudes toward reducing health risks

Completing more StaySafe sessions was associated with greater attitude improvements

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funding for this study was provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health (NIDA/NIH) through a grant to Texas Christian University (R01DA025885; Wayne E. K. Lehman, Principal Investigator). Interpretations and conclusions in this paper are entirely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of NIDA/NIH or the Department of Health and Human Services. This protocol has been registered with clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02777086).

The authors of this paper wish to thank probation officials in the three Texas counties in which this study took place for allowing us to conduct our research at their facilities, for providing staff to assist at the participating facilities in providing space and helping to schedule data sessions, and for the clients who willingly participated in the research.

Footnotes

Declarations of interest: None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Baumeister RF, & Vonasch AJ (2015). Uses of self-regulation to facilitate and restrain addictive behavior. Addictive Behaviors, 44, 3–8. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becan JE, Knight DK, Crawley RD, Joe GW, & Flynn PM (2015). Effectiveness of the Treatment Readiness and Induction Program for increasing adolescent motivation for change. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 50, 38–49. 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blow FC, Walton MA, Bohnert AS, Ignacio RV, Chermack S, Cunningham RM, Booth BM, Ilgen M, Barry KL (2017). A randomized controlled trial of brief interventions to reduce drug use among adults in a low-income urban emergency department: The HealthiER You study. Addiction, 112(8),1395–405. 10.1111/add.13773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonar EE, Walton MA, Cunningham RM, Chermack ST, Bohnert ASB, Barry KL, Booth BM, & Blow FC (2014). Computer-enhanced interventions for drug use and HIV Risk in the emergency room: Preliminary results on psychological precursors of behavior change. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 46(1), 5–14. 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonar EE, Walton MA, Barry KL, Bohnert AS, Chermack ST, Cunningham RM, Massey LS, Ignacio RV, & Blow FC (2018). Sexual HIV risk behavior outcomes of brief interventions for drug use in an inner-city emergency department: Secondary outcomes from a randomized controlled trial. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 183, 217–224. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0376871617305926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2018, April). Probation and Parole in the United States, 2016. https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/ppus16_sum.pdf

- Cohen J (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Earlbam Associates, Hillsdale, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper G, Tindall-Ford S, Chandler P, & Sweller J (2001). Learning by imagining. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 7(1), 68–82. 10.1037/1076-898X.7.1.68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crisante AS, Case BF, & Isakson BL, & Steadman HJ (2014). Understanding study attrition in the evaluation of jail diversion programs for persons with serious mental illness or co-occurring substance use disorders. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 41(6), 772–790. 10.1177/0093854813514580 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dansereau DF (2005). Node-link mapping principles for visualizing knowledge and information. In Tergan SO & Keller T (Eds.), Knowledge Visualization and Information Visualization: Searching for synergies (pp. 61–81). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. 10.1007/11510154_4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dansereau DF, & Simpson DD (2009). A picture is worth a thousand words: The case for graphic representations. Professional Psychology: Research & Practice, 40(1), 104–110. 10.1037/a0011827 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dansereau DF, Knight DK, & Flynn PM (2013). Improving adolescent judgment and decision making. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 44(4), 274–282. 10.1037/a0032495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkbuli A, Polcz V, Dowd B, McKenney M, & Prado G (2019). HIV prevention intervention for substance users: a review of the literature. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 14(1), 1. 10.1186/s13011-018-0189-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festinger DS, Dugosh KL, Kurth AE, & Metzger DS (2016). Examining the efficacy of a computer facilitated HIV prevention tool in drug court. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 162, 44–50. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0376871616001010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J, Wang Y, Du Z, Liao J, He N, & Hao Y (2020). Peer education for HIV prevention among high-risk groups: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infectious Diseases, 20(1), 1–20. 10.1186/s12879-020-05003-9.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Behavioral Research. (2008). TCU Global Risk Assessment (TCU A-RSKForm). Fort Worth: Texas Christian University, Institute of Behavioral Research. https://ibr.tcu.edu/forms/client-health-and-social-risk-forms/ [Google Scholar]

- Joe GW, Lehman WEK, Rowan GA, Knight K, & Flynn PM (2019). Evaluating the impact of a targeted brief HIV intervention on multiple inter-related HIV risk factors of knowledge and attitudes among incarcerated drug users. Journal of HIV/AIDS & Social Services, 18(1), 61–79. 10.1080/15381501.2019.1584140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D (2011). Thinking fast and slow. Macmillan. https://books.google.com/books?id=SHvzzuCnuv8C&lpg=PP2&ots=NTplPC1mJC&dq=Thinking%20fast%20and%20slow&lr&pg=PA15#v=onepage&q=Thinking%20fast%20and%20slow&f=false [Google Scholar]

- Kidd SE, Grey JA, Torrone EA, & Weinstock HS (2019). Increased methamphetamine, injection drug, and heroin use among women and heterosexual men with primary and secondary syphilis — United States, 2013–2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), 68(6), 144–148. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/68/wr/mm6806a4.htm?s_cid=mm6806a4_w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klacynski PA (2005). Metacognition and cognitive variability: A dual-process model of decision making and its development. In Jacobs JE & Klaczynski PA (Eds.), The Development of Judgment and Decision-Making in Children and Adolescents (pp. 39–76). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=4c94AgAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA39&dq=Metacognition+and+cognitive+variability:+A+dualprocess+model+of+decision+making+and+its+development&ots=KeH8CIEgMK&sig=bjHs3SuF0mDpUFf8guSVPnCYmyU#v=onepage&q&f=false [Google Scholar]

- Knight DK, Dansereau DF, Becan JE, Rowan GA, & Flynn PM (2015). Effectiveness of a theoretically-based judgment and decision making intervention for adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44, 1024–1038. 10.1007/s10964-014-0127-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight DK, Joe GW, Crawley RD, Becan JE, Dansereau DF, & Flynn PM (2016). The effectiveness of the Treatment Readiness and Induction Program (TRIP) for improving during-treatment outcomes. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 62, 20–27. 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman WEK, Pankow J, Rowan GA, Gray J, Blue TR, Muiruri R, & Knight K (2018). StaySafe: A self-administered Android tablet application for helping individuals on probation make better decisions pertaining to health risk behaviors. Contemporary Clinical Trials Communications, 10, 86–93. 10.1016/j.conctc.2018.03.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman WEK, Rowan GA, Greener JM, Joe GW, Yang Y, & Knight K (2015). Evaluation of WaySafe: A disease-risk reduction curriculum for substance-abusing offenders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 58, 25–32. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0740547215001312?via%3Dihub [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman WEK, Rowan GA, Pankow J, Joe GW, & Knight K (2019). Gender differences in a disease risk reduction intervention for people in prison-based substance abuse treatment. Federal Probation, 83(2), 27–33. https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/fedpro83&div=16&id=&page= [Google Scholar]

- Lerch J, Walters ST, Tang L, & Taxman FS (2017). Effectiveness of a computerized motivational intervention on treatment initiation and substance use: Results from a randomized trial. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 80, 59–66. 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsch LA, Carroll KM, & Kiluk BD (2014). Technology-based interventions for the treatment and recovery management of substance use disorders: A JSAT special issue. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 46(1), 1–4. 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsch LA, Guarino H, Acosta M, Aponte-Melendez Y, Cleland C, Grabinski M, Brady R, & Edwards J (2014). Web-based behavioral treatment for substance use disorder as a partial replacement of standard methadone maintenance treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 46(1), 43–51. 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.08.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer JP, Muthulingam D, El-Bassel N, & Altice FL (2017). Leveraging the U.S. criminal justice system to access women for HIV interventions. AIDS and Behavior, 21(12), 3527–3548. 10.1007/s10461-017-1778-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muiruri M, Pankow J, Bonnette B, Goldberg G, Knight K, & Lehman WEK (2021). Methodological considerations for conducting research in correctional settings: A field perspective. IBR Technical Report. http://ibr.tcu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/METHODOLOGICAL-CONSIDERATIONS.docx-04_16_2021.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Olver ME, Stockdale KC, & Wormith JS (2011). A meta-analysis of predictors of offender treatment attrition and its relationship to recidivism. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79(1), 6–21. 10.1037/a0022200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pankow J, Johnson A, Muiruri R, Knight K, Flynn P, Joe GW, & Lehman WEK (2018, October). Using StaySafe Decision-making App in Probation Settings: Qualitative Experiences from Study Participants. Poster presented at the Addiction Health Services Research Conference, Savannah, GA. [Google Scholar]

- Pankow J, & Lehman WEK (2018, March). Adapting StaySafe for Women’s Health Pilot Study. Poster presentation at the Academic Health Policy Conference on Correctional Health, Houston, TX. [Google Scholar]