Abstract

The latent viral reservoir formed by HIV-1, mainly in CD4+ T cells, is responsible for the failure of antiretroviral therapy (ART) to achieve a complete elimination of the virus in infected individuals. We previously determined that CD4+ T cells from individuals with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) on treatment with dasatinib are resistant to HIV-1 infection ex vivo. The main mechanism for this antiviral effect is the preservation of SAMHD1 activity. In this study, we aimed to evaluate the impact of dasatinib on the viral reservoir of HIV-infected individuals with CML who were on simultaneous treatment with ART and dasatinib. Due to the low estimated incidence of HIV-1 infection and CML (1:65,000), three male individuals were recruited in Spain and Germany. These individuals had been on treatment with standard ART and dasatinib for median 1.3 years (IQR 1.3-5.3 years). Reservoir size and composition in PBMCs from these individuals was analyzed in comparison with HIV-infected individuals on triple ART regimen and undetectable viremia. The frequency of latently infected cells was reduced more than 5-fold in these individuals. The reactivation of proviruses from these cells was reduced more than 4-fold and, upon activation, SAMHD1 phosphorylation was reduced 40-fold. Plasma levels of the homeostatic cytokine IL-7 and CD4 effector subpopulations TEM and TEMRA in peripheral blood were also reduced. Therefore, treatment of HIV-infected individuals with dasatinib as adjuvant of ART could disturb the reservoir reactivation and reseeding, which might have a beneficial impact to reduce its size.

Keywords: HIV reservoir, CD4+ T cells, SAMHD1, dasatinib, proviral reactivation, HIV functional cure

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Infection by human immunodeficiency type 1 (HIV-1) is currently incurable despite the use of antiretroviral treatment (ART) due to long-lived, highly stable viral reservoir [1–3], mainly formed by a pool of latently infected CD4+ T cell. This reservoir shows variable size among HIV-infected individuals, although it remains relatively stable over time, even in the presence of ART. It has been estimated to be formed by 106-107 latently infected CD4+ T lymphocytes [3, 4] that may reactivate once ART is discontinued, causing viral rebound [5]. Viral rebound usually occurs within 2 weeks after ART discontinuation, reaching similar levels to acute infection [6, 7]. Some individuals who initiated ART very early after infection and had extremely reduced reservoirs may control the residual viral load even after treatment discontinuation [8–13]. They are referred to as post-treatment controllers and the mechanism for this control may involve the HLA-B*35 allele [12] although additional unknown factors are likely to be important as well. Other individuals may exert a long-term control of the infection in which viremia remains undetectable in the absence of ART, as occurs for elite controllers [14–16] and long-term non-progressors (LTNP) [17–19]. This control of residual latently infected cells would mostly rely on the combination of an effective antiviral immune response with low reservoir size. Therefore, strategies aimed at reducing the size of the reservoir as much as possible, such as early initiation of ART, are essential toward gaining control of viral replication once ART is discontinued, paving the road for a potential HIV remission or a functional cure [20, 21].

Although early ART influences the reservoir size and preserves CD4 counts and consequently, the integrity of the immune response, it cannot completely circumvent the establishment of the reservoir, which occurs very early after the infection [22, 23]. The extreme longevity of the latent reservoir has been attributed to the long half-life of the latently infected cells, which has been estimated in 3.7 years [1, 24, 25]. Accordingly, more than 70 years of ART would be necessary to eliminate the reservoir and eradicate the infection or at least, to reduce the reservoir size to a number of cells that could be controlled by the immune response [26]. This long stability is also due to a continuous increase of the latently infected cells mostly by homeostatic proliferation [27] and clonal expansion [28].

Our group described previously that tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) used for the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) such as dasatinib [29, 30] may have an important antiviral activity against HIV-1 replication [31]. This cytostatic drug interferes with TCR-mediated CD4+ T cell activation and therefore, impedes the integration and reactivation of HIV-1 provirus [32]. Moreover, dasatinib preserves the antiviral function of SAMHD1 by impeding its phosphorylation at T592, which is crucial for the restriction of HIV-1 replication in CD4+ T cells [33]. Finally, dasatinib blocks CD4+ T cell proliferation induced by homeostatic cytokines such as IL-2 and IL-7 [34] that are crucial for the stability of the viral reservoir [35]. The worldwide incidence of CML is less than 1 per 100,000 people [36] and CML is not commonly associated with HIV-1 [37]. The CML incidence on HIV-infected individuals is estimated to be 1:65,000 and therefore, few cases have been reported so far [37–48]. No information about the effect of TKIs on the progression of the viral reservoir has been reported to date but it could be essential to evaluate the pertinence of a clinical trial with dasatinib as adjuvant of ART in HIV-infected individuals.

In this study, the effect of dasatinib on the size, composition and reactivation of the reservoir was analyzed in individuals infected with HIV-1 who afterwards developed CML. Individuals on simultaneous treatment with ART and dasatinib showed a small reservoir size as well as a resistance to proviral reactivation in infected peripheral CD4+ T cells. These findings provide supportive evidence to the emerging idea that treatment with dasatinib as an adjuvant to ART may contribute to a welcome smaller frequency of latently infected cells.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Blood samples were obtained from 3 individuals with chronic HIV-1 infection who developed CML and were on treatment with ART and dasatinib, 32 individuals with chronic HIV-1 infection on treatment with ART, and 18 individuals with CML on treatment with dasatinib (Table 1). Eight healthy donors with similar age and gender distribution were recruited as controls. PBMCs were isolated by centrifugation through Ficoll-Hypaque gradient (Pharmacia Corporation, North Peapack, NJ). CD4+ T cells were isolated by direct magnetic labeling using Human CD4 MicroBeads (Miltenyi, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). Plasma and cells were cryopreserved until the moment of analysis. All relevant clinical data from individuals with chronic HIV-1 infection and/or CML are summarized in Table 2.

Table 1.

Summary of the clinical data of individuals who were recruited for this study.

| Individuals on ART+dasatinib | Individuals on ART | Individuals on dasatinib | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individuals, n | 3 | 32 | 18 |

| Male/female, n | 3/0 | 25/7 | 7/11 |

| Median age at HIV diagnosis (years) | 33.0 (IQR 25.0 to 37.0) | 32.0 (IQR 26.5 to 39.0) | N/A |

| Median age at CML diagnosis (years) | 42.0 (IQR 37.0 to 58.0) | N/A | 52.0 (IQR 40.5 to 57.5) |

| Median CD4/CD8 ratio | 0.3 (IQR 0.11 to 1.6) | 0.9 (IQR 0.5 to 1.2) | N/A |

| Median CD4 count (cells/milliliter) | 786.0 (IQR 178 to 1014) | 906 (IQR 601.5 to 1137.4) | N/A |

| ART * (n) | 2 NRTI, 1 INI (2) 1 INI, 1 PI/c (1) |

1/2 NRTI, 1 INI±c (14) 1/2 NRTI, 1 PI±c (6) 2 NRTI, 1 INI/c, 1 PI (1) 2 NRTI, 1 NNRTI (10) 1 PI/c (1) |

N/A |

| Sokal Risk Score, n (L/I/H/UD) ** | 0/1/0/2 | N/A | 11/4/3/0 |

| Response at sampling *** , n | CCyR | N/A | 3 |

| MMR | N/A | 3 | |

| DMR | N/A | 2 |

NRTI: nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; NNRTI: Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; PI: protease inhibitors; INI: integrase inhibitor; c: Cobicistat.

L, Low; I, Intermediate; H, High; UD, undetermined.

CCyR, Complete Cytogenetic Response; MMR, Major Molecular Response; DMR, Deep Molecular Response.

N/A: Not applicable

Table 2.

Detailed clinical data of participants recruited for the study.

| Code | Gender (M/F) | Age at diagnosis of HIV infection (years) | Age at diagnosis of CML (years) | Nadir CD4 | CD4 per milliliter | CD4/CD8 ratio | ART | Sokal risk | Molecular response (log) | Previous exposition to dasatinib (Y/N, which) | Time of treatment with dasatinib (months) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ART | 1 | M | 40 | N/A | 618.8 | 840.1 | 1.2 | 3TC/ABC/DTG | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 2 | M | 40 | N/A | 252.2 | 346.5 | 0.4 | 3TC/ABC/DTG | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 3 | M | UD | N/A | UD | 793.0 | 0.5 | BIC/FTC/TAF | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 4 | M | 39 | N/A | 123.1 | UD | UD | BIC/FTC/TAF | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 5 | M | 47 | N/A | 534.6 | 815.1 | 1.5 | BIC/FTC/TAF | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 6 | M | 42 | N/A | 722.5 | UD | 0.5 | 3TC/DTG | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 7 | M | UD | N/A | 142.8 | 458.5 | 0.5 | DRV/c | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 8 | M | 15 | N/A | 478.2 | 1097.4 | 1.0 | BIC/FTC/TAF | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 9 | M | 25 | N/A | 388.0 | 1250.0 | UD | EVG/FTC/TDF/c | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 10 | M | 22 | N/A | 313.0 | 1108.0 | UD | EVG/FTC/TDF/c | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 11 | M | 47 | N/A | 530.0 | 1462.0 | UD | 3TC/ABC/RPV | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 12 | M | 24 | N/A | 336.0 | 559.0 | UD | 3TC/ABC/DTG/DRV/c | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 13 | M | 31 | N/A | 292.0 | 763.0 | UD | EFV/FTC/TDF | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 14 | F | 24 | N/A | UD | 979.2 | UD | EVG/FTC/TDF/c | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 15 | F | 32 | N/A | 91.0 | 969.0 | UD | FTC/LOP/r | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 16 | F | 37 | N/A | 283.0 | 1240.0 | 1.2 | 3TC/ABC/NVP | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 17 | M | 27 | N/A | 90.0 | 832.0 | 1.3 | DRV/FTC/TDF/c | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 18 | M | 32 | N/A | 144.0 | 669.0 | 0.9 | EVG/FTC/TAF/c | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 19 | F | 29 | N/A | 167.0 | 1098.0 | 1.5 | 3TC/ABC/NVP | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 20 | M | 31 | N/A | UD | 892.0 | 1.1 | 3TC/ABC/DTG | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 21 | M | 43 | N/A | 510.0 | 920.0 | 1.1 | 3TC/ABC/NVP | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 22 | F | 37 | N/A | 363.0 | 2134.0 | 2.4 | 3TC/ABC/DTG | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 23 | M | 35 | N/A | 521.0 | 1081.0 | 0.4 | FTC/RPV/TDF | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 24 | M | 38 | N/A | UD | 1380.0 | 0.6 | 3TC/ABC/DRV/c | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 25 | F | 22 | N/A | UD | 579.0 | 0.4 | DRV/FTC/TDF/c | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 26 | M | 23 | N/A | 268.0 | 609.0 | 0.7 | 3TC/ABC/DTG | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 27 | M | 36 | N/A | 490.0 | 1099.0 | 1.2 | EFV/FTC/TDF | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 28 | M | 28 | N/A | 245.0 | 484.0 | UD | DRV/FTC/TAF/c | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 29 | F | 31 | N/A | UD | 1368.0 | UD | 3TC/ABC/ATV | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 30 | M | 39 | N/A | 209.0 | 1225.6 | UD | 3TC/ABC/RPV | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 31 | M | 37 | N/A | 349.0 | 540.0 | UD | EVG/FTC/TDF/c | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 32 | M | 31 | N/A | 258.0 | 518.0 | UD | FTC/RPV/TDF | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| ART+dasatinib | 33 | M | 33 | 37 | 563.0 | 1014.0 | 1.6 | BIC/FTC/TAF | UD | 5 | Imatinib | 15 |

| 34 | M | 37 | 58 | <200.0 | 786.0 | 0.3 | BIC/FTC/TAF | High | 3 | N | 16 | |

| 35 | M | 25 | 42 | 77.0 | 178.0 | 0.11 | DTG/DRV/c | Interm. | 4.5 | Imatinib | 63 | |

| Dasatinib | 36 | F | N/A | 49 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Low | 4 | Imatinib | 30 |

| 37 | F | N/A | 27 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Low | 4.5 | Imatinib. dasatinib. ponatinib | 10 | |

| 38 | M | N/A | 55 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Low | 3 | Imatinib. bosutinib | 30 | |

| 39 | F | N/A | 41 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Low | N | Imatinib. nilotinib. dasatinib. | 1 | |

| 40 | M | N/A | 24 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Low | 3 | N | 84 | |

| 41 | F | N/A | 57 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Interm. | 3 | Nilotinib | 35 | |

| 42 | F | N/A | 59 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Low | 4 | N | 30 | |

| 43 | F | N/A | 57 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Low | 3 | Imatinib | 72 | |

| 44 | M | N/A | 39 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | High | N | Nilotinib | 1 | |

| 45 | F | N/A | 56 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | High | 5 | N | 48 | |

| 46 | F | N/A | 55 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | High | 5 | N | 4.5 | |

| 47 | M | N/A | 43 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Low | 4.5 | N | 12 | |

| 48 | M | N/A | 44 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Interm. | 4.5 | Imatinib | 84 | |

| 49 | F | N/A | 60 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Interm. | 5 | N | 12 | |

| 50 | F | N/A | 43 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Low | 5 | Imatinib. nilotinib | 42 | |

| 51 | F | N/A | 59 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Interm. | 5 | Dasatinib | 12 | |

| 52 | M | N/A | 72 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Low | 4 | N | 48 | |

| 53 | M | N/A | 26 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Low | 5 | N | 80 |

ART, antiretroviral treatment; F, female; Interm., intermediate; M, male; N, no; N/A, non-applicable; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor; U, undetected; UD, undetermined; Y, yes.

2.2. Study approval

All individuals gave informed written consent to participate. Confidentiality and anonymity were protected by current Spanish and European Data Protection Acts. This study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and it was previously approved by the Ethic Committee of Instituto de Salud Carlos III (IRB IORG0006384), according to protocol with reference CEI PI 46_2018, and by the Ethics Committees of all participating hospitals.

2.3. Quantification of proviral integration

Whole genomic nucleic acid was extracted using QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen Iberia, Madrid, Spain). Proviral integrated DNA was quantified with TaqMan probes conjugated with FAM using a nested Alu-LTR PCR in a QuantStudio 3D Digital PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific España, Madrid, Spain), as previously described [49, 50] with modifications. Briefly, a first conventional PCR was performed using oligonucleotides against Alu sequence and HIV-1 LTR, with the following conditions: 95°C, 8 min; 12 cycles: 95°C, 1 min; 60°C, 1 min; 72°C, 10 min; 1 cycle: 72°C, 15 min. Then, a second dPCR was performed using PrimeTime FAM/ZEN/Iowa Black TaqMan probes (Integrated DNA Technologies, Leuven, Belgium) and QuantStudio Digital PCR Chip kit (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA). CCR5 gene was used as housekeeping gene for measuring the input DNA and normalize data. Therefore, it was quantified in the same chip using TaqMan™ Gene Expression Assay and a VIC-conjugated Taqman probe (Thermo Fisher Scientific). QuantStudio 3D AnalysisSuite Cloud Software was used for analysis (Thermo Fisher Scientific), based on the Poisson-Plus model that showed improved accuracy in the quantification of results of digital PCR experiments [51].

2.4. Flow cytometry analysis

Conjugated antibodies for surface staining CD3-APC and CD4-PercP were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). CD4+ T cell subpopulations were analyzed by staining with CCR7-FITC and CD45RA-PE-Cy7 (BD Biosciences) as follows: naïve (TN) (CD45RA+CCR7+), central memory (TCM) (CD45RA-CCR7+), effector memory (TEM) (CD45RA-CCR7-) and terminally differentiated effector memory (TEMRA) (CD45RA+CCR7-) cells [52]. Antibodies for intracellular staining of HIV-1 core antigens (55, 39, 33 and 24 kDa proteins) (clone kc57) conjugated to FITC and SAMHD1 phosphorylated at Thr592 (pSAMHD1) conjugated with PE were purchased from Beckman Coulter (Beckman Coulter Spain, Barcelona, Spain) and Cell Signaling (Cell Signaling Technology Europe, Leiden, The Netherlands), respectively. Data acquisition was performed in a BD LSRFortessa X-20 flow cytometer using FACS Diva software (BD Biosciences). Data analysis was performed with FlowJo_V10 software (TreeStar, Ashland, OR).

2.5. Proviral reactivation analysis

CD4+ T cells isolated from HIV-infected individuals on ART were incubated ex vivo with Dynabeads human T activator CD3/CD28 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 300 U/ml IL-2 (Chiron, Emeryville, CA) for 7 days, in the presence or absence of dasatinib 75nM (37.9 ng/ml) (Selleckchem, Deltaclon, Madrid, Spain). CD4+ T cells isolated from individuals with HIV infection and CML were incubated ex vivo only with Dynabeads human T activator CD3/CD28 and IL-2 for 7 days and then with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) 25 ng/ml and ionomycin 1.5 μg/ml for 18 hours in the presence of brefeldin A (BD GolgiPlug, BD Biosciences). After fixation and permeabilization with IntraPrep Permeabilization Reagent (Beckman Coulter Spain), cells were stained with an antibody against HIV-1 core antigen (clone kc57) conjugated with FITC and an antibody against pSAMHD1. Phosphorylation of SAMHD1, which correlates with loss of its ability to restrict HIV-1 replication [33], and the synthesis of HIV-1 core proteins were analyzed by flow cytometry, as described above.

2.6. Intact proviral DNA assay (IPDA)

The proportion of intact proviruses was evaluated in total DNA extracted from PBMCs of HIV-infected individuals treated only with ART or with ART and dasatinib. Two replicate wells of up to 1 μg DNA each were combined with ddPCR Supermix for Residual DNA Quantification (Bio-Rad, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Madrid, Spain) and multiplex prime/probe sets targeting the packaging signal and envelope non-hypermutated sequences, as previously described [53]. Normalization by cell number and DNA shearing was based on quantifications in duplicate wells, containing 50 ng DNA each using a multiplex ddPCR targeting two regions of the RPP30 gene [54] and ddPCR Supermix for Probes (no dUTPs, Bio-Rad). All probes were FAM/HEX-ZEN-IowaBlackFQ double-quenched and purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies. Both quantifications were run simultaneously with the following thermal cycling conditions: 10 minutes at 95°C followed by 45 cycles consisting of 30 seconds at 94°C; 60 seconds at 53°C per cycle; final extension of 10 minutes at 98°C and a final hold at 10°C. Droplets were read on a QX100 Droplet Reader (Bio-Rad).

2.7. Luminex assay

A customized Human Magnetic Luminex Assay kit (R&D Systems) was used for the simultaneous detection of homeostatic cytokines in plasma: IL-2, IL-7, IL-15, and IL-21. Instructions provided by the supplier were followed and analysis was performed on a Bio-Plex 200 System (Bio-Rad).

2.8. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Graph Pad Prism 9.0 (Graph Pad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). Statistical significance among groups was calculated using one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Statistical differences among two populations were calculated with Mann–Whitney non-parametric U test. P values (p) < 0.05 were considered statistically significant in all comparisons and were represented as *, **, or *** for p<0.05, p<0.01 and p<0.001, respectively.

3. Results

3.1. Individuals’ characteristics

This is an observational, cross-sectional study in which participated a total of 59 individuals divided in 4 cohorts.

Three individuals infected with HIV-1 who were diagnosed afterwards with CML were recruited at ICH Study Center (Hamburg, Germany) (Participant 33), the University Hospital of Cologne (Cologne, Germany) (Participant 34), and Hospital Universitario Severo Ochoa (Madrid, Spain) (Participant 35) (Tables 1 and 2).

Participant 33 is a 47-year old Caucasian male who was diagnosed with HIV-1 infection when he was 33-year old and with CML when he was 37-year old. He had been on treatment with raltegravir, abacavir and lamivudine for 9 years which was later simplified to bictegravir, emtricitabine and tenofovir (BIC/FTC/TAF). His HIV-RNA was undetectable (< 50 copies/mL) more than 9 years. He had also been on imatinib for 9 years that was changed for dasatinib due to some intolerability (fatigue, polyneuropathy). At the time of last sampling, he had been on treatment with dasatinib for 1 year and 3 months, CD4 count was 1014 cells/μl and CD4/CD8 ratio was 1.6. He maintained CML molecular response of 4.0 (ratio BCR-ABL1/ABL1 ≤ 0.01%) and undetectable viral load.

Participant 34 is a 59-year old Caucasian male who was diagnosed with HIV-1 infection when he was 37-year old and with CML when he was 58-year old (1 year and 4 months ago). He was on treatment with zidovudine, rilpivirine and tenofovir (AZT/RPV+TDF) at CML diagnosis and initiated bictegravir, emtricitabine and tenofovir (BIC/FTC/TAF) after introducing dasatinib 15 months ago to avoid interactions. No other TKI was administered prior to dasatinib. At the time of last sampling, CD4 count was 786 cells/μl, CD4/CD8 ratio was 0.3 and he showed CML molecular response 3.0 (ratio BCR-ABL1/ABL1 ≤ 0.1%) and undetectable viral load.

Participant 35 is a 52-year old Caucasian male who was diagnosed with HIV-1 infection when he was 25-year old and with CML when he was 42-year old (first described in Campillo-Recio et al. [38]). He was on treatment with dolutegravir and darunavir/cobicistat (DTG/DRC/c) and with imatinib for 4 years. Due to poor adherence to both treatments, he experienced recurrent rebounds of plasma viremia, low CD4 count (178 CD4/μl; CD4/CD8 ratio 0.11) and failure to imatinib treatment. As a consequence, dasatinib was introduced and he had been on treatment with it for 5 years and 3 months when the first blood sample was taken. Due to pneumonia, he discontinued treatment with dasatinib for 5 months and then nilotinib was introduced. He maintained CML molecular response of 4.5-5.0 (ratio BCR-ABL1/ABL1 ≤ 0.0032%) since then (2 years). He showed undetectable viral load at the time of sampling.

Thirty-two individuals with chronic HIV-1 infection on ART and undetectable viral load were also recruited for this study (Table 1) and were followed up for 1 year. They were selected according to their age, gender and ART regimen to match the individuals with HIV infection and CML. Median time on ART was similar between HIV-infected individuals treated only with ART and those on ART and dasatinib. Most individuals were male (78%), their median age at HIV-1 diagnose was 32 years (interquartile range (IQR) 27 to 39) and their median age at sampling was 44 years (IQR 37 to 54). Most ART regimens (43.75%) consisted of one or two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) and one integrase inhibitor (INI) with or without cobicistat. Median CD4 count was 906 cells/μl (IQR 601.5 to 1137.4) and median CD4/CD8 ratio was 0.9 (IQR 0.5 to 1.2). Table 2 shows relevant clinical data of these individuals. Due to the limited number of cells isolated per sample, not all the analyses were performed with all the samples.

Eighteen individuals diagnosed with chronic phase CML were also recruited for this study (Table 1). They were all on treatment with dasatinib and on hematological and cytogenic remission. Most individuals were female (61%) and their median age at diagnosis of CML was 52.0 years (IQR 40.5 to 57.5). Sixty-one percent showed low prognostic Sokal risk and 66.7% presented deep molecular response against cancerous cells at the time of sampling (ratio BCR-ABL1/ABL1 ≤ 0.0032%). Median time of treatment with dasatinib was 2.5 years (interquartile range (IQR) 0.5 to 4.0). Table 2 shows relevant clinical characteristics of these individuals.

Eight healthy donors with similar age and gender distribution were recruited as negative controls.

3.2. Quantification of HIV-1 proviral integration

The frequency of HIV-1 infected cells was quantified by dPCR in individuals on treatment only with ART or with ART and dasatinib. The treatment time with ART was similar in both groups of individuals. Proviral integration was 5.7-fold lower on average in individuals treated with dasatinib (p<0.05) (Fig. 1a). A two-year followup of participants on treatment with ART and dasatinib was performed in order to analyze changes in the proviral DNA. No significant changes were found between samples (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1. Treatment with ART and dasatinib reduced the frequency of latently infected cells.

(A) Quantification by dPCR of proviral DNA per million of PBMCs from HIV-infected individuals on treatment with ART (participants 33, 34 and 35) and dasatinib in comparison with individuals only on ART. (B) Followup of the previously indicated participants, highlighting the sample represented in the previous bar graph for participants 33, 34 and 35 (black triangle) or individuals on treatment only with ART (black circle). Each dot corresponds to one sample and lines represent mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical significance was calculated using Mann–Whitney U test. *p < 0.05.

3.3. Effect of dasatinib on provirus reactivation

In order to determine whether the presence of dasatinib was interfering with the in vitro reactivation of the provirus from the reservoir of HIV-infected individuals, CD4+ T cells isolated from PBMCs of these individuals were activated for 7 days with aCD3/CD28/IL-2 in the presence (+) or absence (−) of dasatinib in the culture medium. Reactivation of the provirus was induced by treatment with PMA and ionomycin for 18 hours in the presence of brefeldin A to prevent the release of viral proteins to the culture medium. CD4 purity was determined as 98%. Previous in vitro treatment with dasatinib reduced 4.4-fold on average the production of HIV-1 core antigens from the viral reservoir (p<0.01) (Fig. 2a). SAMHD1 phosphorylation was reduced more than 30-fold on average (p<0.01) in CD4+ T cells when dasatinib was added to the culture medium before the activating stimuli (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2. Treatment with dasatinib interfered efficiently with TCR-mediated reactivation of HIV-1 provirus.

The synthesis of HIV-1 core antigens (A) and the phosphorylation of SAMHD1 (B) were quantified by flow cytometry in CD4+ T cells isolated from PBMCs of HIV-infected individuals only on ART activated for 7 days with antiCD3/CD28/IL-2 in the presence (+) or absence (−) of dasatinib in the culture medium. The synthesis of HIV-1 core antigens (C) and the phosphorylation of SAMHD1 (D) were also quantified by flow cytometry in CD4+ T cells isolated from PBMCs of HIV-infected individuals on treatment only with ART or with ART and dasatinib (Participants 33, 34 and 35), activated for 7 days with antiCD3/CD28/IL-2. Each dot corresponds to one sample and lines represent mean ± SEM. Open symbols stand for undetected values. Statistical significance was calculated using Mann–Whitney U test. ** p < 0.01.

The effect of dasatinib in vivo on the proviral reactivation was analyzed in CD4+ T cells isolated from PBMCs of HIV+CML individuals on ART and dasatinib, and then compared to proviral reactivation from CD4+ T cells isolated from HIV-infected individuals only on ART. The production of HIV-1 core antigens from the viral reservoir was reduced 7.3-fold on average (p<0.01) in CD4+ T cells from individuals treated with ART and dasatinib (Fig. 2c). Treatment in vivo with dasatinib also dramatically impaired SAMHD1 phosphorylation of CD4+ T cells, as it was reduced more than 21-fold on average in individuals on ART and dasatinib (p<0.01) (Fig. 2d).

3.4. Quantification of intact proviruses

We previously described a potent cytostatic effect of dasatinib on CD4+ T cells that cannot be overcome by TCR-mediated stimuli or cytokine-induced homeostatic activation [32, 34]. However, the possibility that dasatinib was also interfering with the fitness of the proviruses in the reservoir should be investigated. Therefore, the proportion of intact proviruses was evaluated by IPDA in individuals 33 and 34 in comparison with those individuals only on ART who presented similar levels of total integrated provirus (as shown in Fig. 1a). This analysis was not performed in participant 35 due to scarcity of the sample. No differences were found between the proportions of intact proviruses in the reservoir of individuals treated with ART and dasatinib in comparison with individuals only treated with ART and similar reservoir size (Fig. 3a). The levels of hypermutated 3’-deleted and 5’-deleted proviruses were slightly increased in participant 33 who had been on treatment with imatinib for more 9 years and then dasatinib for 1.25 years, in comparison with participant 34 who had been on treatment with dasatinib for 1.3 years (Fig. 3b and c).

Fig. 3. Treatment with dasatinib did not change significantly the proportion of intact and defective HIV-1 proviruses in PBMCs from individuals 33 and 34.

The proportion of intact proviruses (A), hypermutated/3’-deleted (B) and 5’-deleted (C) proviruses per million of cells was evaluated by IPDA in PBMCs from individuals 33 and 34 in comparison with HIV-infected individuals treated only with ART. Each dot corresponds to one sample and lines represent mean ± SEM. Open symbols stand for undetected values. Statistical significance was calculated using Mann–Whitney U test.

3.5. Distribution of CD4+ T cell subpopulations

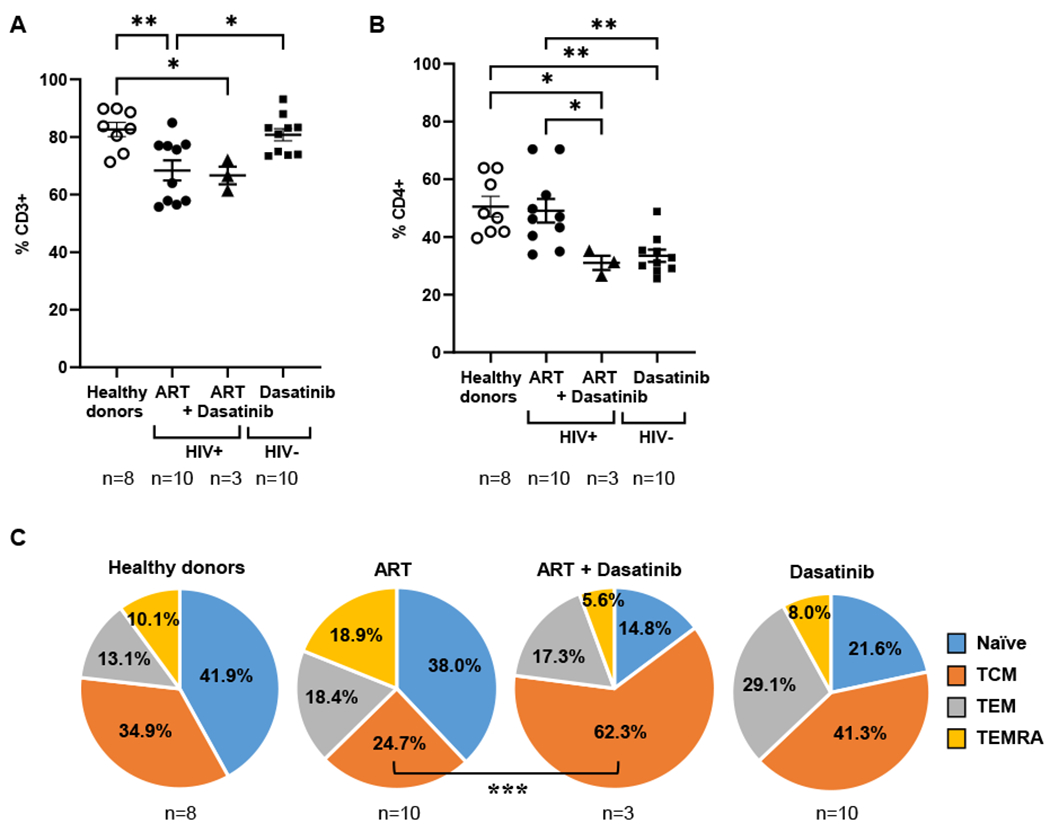

Total levels of CD3+ cells were not significantly affected by treatment with dasatinib in HIV-infected individuals (Fig. 4a), but the level of CD4+ T cells was reduced 1.6-fold on average in individuals treated with dasatinib (p<0.05) (Fig. 4b). This CD4 lymphopenia has been described previously during treatment with dasatinib, and accordingly, we observed the same low CD4 levels in CML individuals treated with dasatinib (p<0.01). Despite the reduction in CD4+ T cell levels, CD3+ cells were increased in individuals with CML in comparison with HIV-infected individuals (p<0.05) (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4. Treatment with dasatinib modified the distribution of CD4+ T cell subpopulations in HIV-infected individuals.

The proportion of CD3+ (A) and CD4+ (B) cells in PBMCs from HIV-infected individuals treated only with ART or treated with ART and dasatinib (individuals 33, 34 and 35) was compared to individuals HIV negative affected with CML on treatment only with dasatinib and with healthy donors. (C) The distribution of CD4+ T cell subpopulations was determined by flow cytometry in PBMCs isolated from these three groups of individuals after staining with antibodies against CCR7 and CD45RA. Each dot corresponds to one sample and lines represent mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was calculated using One-way ANOVA. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Treatment with dasatinib increased the proportion of CD4+ TCM 2.5-fold on average in HIV-infected individuals on ART and dasatinib, in comparison with individuals only treated with ART (p<0.01) (Fig. 4c). Conversely, the levels of effector CD4+ TEMRA cell subpopulation were overall reduced 3.3-fold on average in these individuals. CD4+ T naïve (TN) cells were also reduced 2.5-fold.

3.6. Effect of dasatinib on plasma levels of homeostatic cytokines

HIV-infected individuals on treatment with ART and dasatinib showed levels of IL-7 that were reduced 2.3-fold in comparison with individuals only on ART (Fig. 5a). Plasma levels of IL-21 and IL-15 were reduced 1.7- and 1.6-fold, respectively (Fig. 5b and c), whereas IL-2 levels remained unchanged (Fig. 5d) in both groups of individuals.

Fig. 5. Treatment with dasatinib changed the levels of homeostatic cytokines in plasma of HIV-infected individuals.

Plasma levels of IL-7 (A), IL-21 (B), IL-15 (C) and IL-2 (D) from HIV-infected individuals on ART and dasatinib (Participants 33, 34 and 35) or only with ART were analyzed by Luminex assay and compared to plasma levels of HIV negative individuals with CML on treatment with dasatinib and healthy donors. Each dot corresponds to one sample and lines represent mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was calculated using Mann–Whitney U test.

4. Discussion

The latent reservoir is very dynamic in HIV-infected individuals on ART and the rate of decay for intact provirus is more rapid than defective provirus [55]. Therefore, more than 88% of the proviruses that form the reservoir are supposed to be defective [56]. However, the presence of intact proviruses, even in a very low proportion, is enough to produce the rebound of viremia in the absence of ART [57, 58].

HIV-infected individuals who develop CML and are on ART and TKIs constitute a special cohort of individuals with a very low reservoir size. The viral reservoir in participant 33, who had been on treatment with imatinib for 9 years and with dasatinib for 1.25 years, showed undetectable intact proviruses and higher levels of defective proviruses than participant 34 who had been on treatment with dasatinib as first-line for 1.3 years. During the follow-up, the frequency of latently infected cells in participant 34 decreased to very low levels after 5 months of treatment with dasatinib, whereas the reservoir size in participant 35 increased 1 year after changing dasatinib for nitotinib. Therefore, long-term treatment with TKIs seemed to have a positive effect on the reservoir size, being the combination of imatinib and dasatinib the one that showed better results. Due to the presence of intact proviruses in participant 34, the reactivation of the provirus upon TCR-mediated activation should be possible at least in PBMCs from this individual. However, although the latent reservoir in PBMCs from individuals on treatment with ART and TKIs was detectable, it could not be reactivated in vitro in response to potent TCR-mediated activation. Most likely, this was due to the potent cytostatic activity of dasatinib, as was reflected in the low level of SAMHD1 phosphorylation and the impaired activation of essential transcription factors such as NF-κB [32]. This long-term effect of dasatinib on the inhibition of SAMHD1 phosphorylation in CD4+ T cells was previously described in individuals with CML on chronic treatment with this TKI [59]. The preservation of SAMHD1 antiviral function probably contributes to the protective activity of TKIs against HIV-1 infection, which is supported by the extremely low frequency of latently infected cells in the cohort of HIV-infected individuals with CML.

Other mechanisms are probably involved in the effect of dasatinib on the smaller size of HIV-1 reservoir in these individuals. We previously described that CD4+ T cells from individuals treated with dasatinib are unresponsive to homeostatic cytokines such as IL-7 [34]. This interference with CD4 proliferation did not affect the viability of the cells, but due to the potent antiproliferative effect, it could interfere with the reservoir replenishment and consequently, contribute to the decrease of the reservoir size. Moreover, treatment with dasatinib showed a tendency to reduce the levels of IL-7 in vivo in individuals on ART and dasatinib, although without statistical significance maybe due to data dispersion. It is noteworthy that participant 33 showed the smallest level of IL-7 in correlation with undetectable levels of intact provirus. Dasatinib also affects the distribution of CD4+ T cell subpopulations [60]. Although highly stable CD4+ TCM cells are considered the main component of the reservoir [27], the largest contributors to HIV-1 reservoir maintenance are the effector memory CD4+ T cells, such as TEM and TEMRA [61]. Individuals on ART and dasatinib showed lower levels of CD4+ TEMRA cells that are short-lived, express high levels of activation markers [62] and contain a higher quantity of unstable viral forms [63], thereby contributing more efficiently to the proviral rebound and reservoir replenishment. Besides, CD4+ TN cells, which are considered an important contributor to the latent reservoir [64, 65] and have remarkably long half-lives (1-8 years) [66], were also greatly reduced in individuals on ART and dasatinib. As a consequence, the proportion of TCM was increased in comparison with individuals only on ART. This different distribution of CD4+ T cell subpopulations may suggest a restricted dynamism of the viral reservoir in the presence of dasatinib.

An important limitation of this study, apart from the low incidence of HIV-1 infection and CML that makes very unlikely the recruitment of more individuals with both diseases, is that although CD4+ T cells are the most important reservoir of HIV-1 infection, they are not the only one. Therefore, more analyses are necessary to evaluate the effect of ART and dasatinib not only in blood CD4+ T cells but also in other cell types that form part of the reservoir such as macrophages and in other anatomic sanctuaries such as the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) and the lymph nodes [67]. These sanctuaries may be highly stable due to the inaccessibility for efficient drug distribution, which may be responsible for low drug concentration and low-level replication [68]. However, the apparent volume of distribution of dasatinib has been estimated as 2,505 L, suggesting that it is extensively distributed in the extravascular space [69].

On the other hand, in vitro and ex vivo studies suggest that lower concentrations of dasatinib than the dose usually used to treat CML may be able to develop an efficient antiviral effect [70]. The dose of dasatinib used ex vivo was 75nM (38ng/ml) which correlates with Cmax reached in healthy adults after the administration of 50mg once per day [71], although the recommended dose of dasatinib is 100mg per day [69]. We previously demonstrated that the lowest dose of dasatinib that was effective as antiviral is 16nM (8.26 ng/ml) [32], which means that one-ninth of the recommended dose for the treatment of CML can be used to be adjuvant of ART. We also demonstrated that treatment with dasatinib ex vivo was very safe, with a selectivity index higher than 600 [32], which ruled out the possibility that the absence of proviral reactivation in CD4+ T cells from HIV-1 infected individuals was due to an increased cytotoxicity due to treatment ex vivo. Consequently, the main side effects attributed to dasatinib, which are mainly cytopenia, pleural effusion and infectious complications [69], would probably be infrequent with low doses administered during short periods of time [60, 70]. Nevertheless, these potential adverse effects should be carefully monitored during simultaneous administration of ART and dasatinib due to dasatinib is mostly metabolized by cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) [69, 72] and therefore, potential interactions with some ART regimens should be avoided [70]. In particular, ART regimens containing CYP3A4 inhibitors such as ritonavir or cobicistat should not be used simultaneously with dasatinib to avoid a potential increase in adverse effects [73]. Conversely, CYP3A4 inducers such as non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs), mostly efavirenz, etravirine, and nevirapine [74], would reduce the antiviral effect of dasatinib when administered simultaneously. However, no interactions are expected with current recommended regimens including nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) or integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTIs) such as raltegravir or dolutegravir.

In summary, the low frequency of latently infected cells observed in individuals on ART and dasatinib may be due to several mechanisms: first, the preservation of SAMHD1 antiviral activity exerted by dasatinib that would prevent the infection of new target cells; second, the blockage of reservoir replenishment by homeostatic proliferation mediated by IL-7; third, the potent cytostatic effect of dasatinib on CD4+ T cells that would prevent their activation and the subsequent reactivation of the latent provirus; and finally, changes in the distribution of CD4+ T cell subpopulations that would reduce the levels of effector CD4+ T cells with the ability to reseed the reservoir.

In conclusion, treatment with TKIs such as dasatinib as adjuvant of ART could be considered a potential therapeutic intervention to reduce the size of HIV-1 reservoir and its reactivation from latency. So far, allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) in HIV-infected people with hematological malignancies has been the only clinical intervention that has efficiently reduced the reservoir size [75]. Unfortunately, this approach is not scalable to all people living with HIV. Although short-term treatment with dasatinib might not likely cause so dramatic reduction of the frequency of latently infected cells as HSCT, the intervention would be safer and may be applied to a wider population of HIV-infected individuals. Accordingly, treatment with ART and low-dose dasatinib might have a beneficial impact on the reservoir size to help control the reactivation of residual latently infected CD4+ T cells after ART discontinuation, hopefully improving the possibilities for a functional cure in chronically HIV-1 infected individuals. Our data support the conduct of a pilot clinical trial to test this hypothesis.

Acknowledgements

We greatly appreciate all the individuals for their participation. We thank the excellent secretarial assistance of Mrs Olga Palao. This work was supported by NIH grant R01AI143567; the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (PID2019-110275RB-I00); the Spanish AIDS Research Network RD16CIII/0002/0001 that is included in Acción Estratégica en Salud, Plan Nacional de Investigación Científica, Desarrollo e Innovación Tecnológica 2016-2020, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, European Region Development Fund (ERDF). The work of María Rosa López-Huertas and Sara Rodríguez-Mora is financed by NIH grant R01AI143567. The work of Lorena Vigón is supported by a pre-doctoral grant from Instituto de Salud Carlos III (FIS PI16CIIE00034-ISCIII-FEDER). Jose M. Miró received a personal 80:20 research grant from Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS) (Barcelona, Spain) during 2017–2021.

#. Contributing members of the Multidisciplinary Group of Study of HIV-1 reservoir (MGS-HIVRES) (in alphabetical order):

Magdalena Corona1, María del Mar Díaz-Goizueta2, Elena Knops3, Alejandro Luna de Abia1, Luz Martín-Carbonero4, Pablo Ryan5, Adam Spivak6

1Hematology Service, Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal, Madrid, Spain

2Hematology Service, Hospital Universitario Severo Ochoa, Madrid, Spain

3Institut für Virologie, Clinical University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany

4Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Hospital de la Paz (IdiPAZ), 28046, Madrid, Spain

5Department of Infectious Diseases, Infanta Leonor Hospital, 28031, Madrid, Spain.

6Division of Microbiology and Immunology, Department of Pathology, University of Utah School of Medicine, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- [1].Finzi D, Hermankova M, Pierson T, Carruth LM, Buck C, Chaisson RE, Quinn TC, Chadwick K, Margolick J, Brookmeyer R, Gallant J, Markowitz M, Ho DD, Richman DD, Siliciano RF, Identification of a reservoir for HIV-1 in patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy, Science 278(5341) (1997) 1295–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Wong JK, Hezareh M, Gunthard HF, Havlir DV, Ignacio CC, Spina CA, Richman DD, Recovery of replication-competent HIV despite prolonged suppression of plasma viremia, Science 278(5341) (1997) 1291–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Chun TW, Stuyver L, Mizell SB, Ehler LA, Mican JA, Baseler M, Lloyd AL, Nowak MA, Fauci AS, Presence of an inducible HIV-1 latent reservoir during highly active antiretroviral therapy, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94(24) (1997) 13193–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Rong L, Perelson AS, Modeling latently infected cell activation: viral and latent reservoir persistence, and viral blips in HIV-infected patients on potent therapy, PLoS Comput Biol 5(10) (2009) e1000533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Chun TW, Davey RT Jr., Engel D, Lane HC, Fauci AS, Re-emergence of HIV after stopping therapy, Nature 401(6756) (1999) 874–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Davey RT Jr., Bhat N, Yoder C, Chun TW, Metcalf JA, Dewar R, Natarajan V, Lempicki RA, Adelsberger JW, Miller KD, Kovacs JA, Polis MA, Walker RE, Falloon J, Masur H, Gee D, Baseler M, Dimitrov DS, Fauci AS, Lane HC, HIV-1 and T cell dynamics after interruption of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in patients with a history of sustained viral suppression, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96(26) (1999) 15109–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ruiz L, Martinez-Picado J, Romeu J, Paredes R, Zayat MK, Marfil S, Negredo E, Sirera G, Tural C, Clotet B, Structured treatment interruption in chronically HIV-1 infected patients after long-term viral suppression, AIDS 14(4) (2000) 397–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Archin NM, Vaidya NK, Kuruc JD, Liberty AL, Wiegand A, Kearney MF, Cohen MS, Coffin JM, Bosch RJ, Gay CL, Eron JJ, Margolis DM, Perelson AS, Immediate antiviral therapy appears to restrict resting CD4+ cell HIV-1 infection without accelerating the decay of latent infection, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109(24) (2012) 9523–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Cheret A, Bacchus-Souffan C, Avettand-Fenoel V, Melard A, Nembot G, Blanc C, Samri A, Saez-Cirion A, Hocqueloux L, Lascoux-Combe C, Allavena C, Goujard C, Valantin MA, Leplatois A, Meyer L, Rouzioux C, Autran B, Group OA-S, Combined ART started during acute HIV infection protects central memory CD4+ T cells and can induce remission, J Antimicrob Chemother 70(7) (2015) 2108–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Goujard C, Girault I, Rouzioux C, Lecuroux C, Deveau C, Chaix ML, Jacomet C, Talamali A, Delfraissy JF, Venet A, Meyer L, Sinet M, Group ACPS, HIV-1 control after transient antiretroviral treatment initiated in primary infection: role of patient characteristics and effect of therapy, Antivir Ther 17(6) (2012) 1001–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lodi S, Meyer L, Kelleher AD, Rosinska M, Ghosn J, Sannes M, Porter K, Immunovirologic control 24 months after interruption of antiretroviral therapy initiated close to HIV seroconversion, Arch Intern Med 172(16) (2012) 1252–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Saez-Cirion A, Bacchus C, Hocqueloux L, Avettand-Fenoel V, Girault I, Lecuroux C, Potard V, Versmisse P, Melard A, Prazuck T, Descours B, Guergnon J, Viard JP, Boufassa F, Lambotte O, Goujard C, Meyer L, Costagliola D, Venet A, Pancino G, Autran B, Rouzioux C, Group AVS, Post-treatment HIV-1 controllers with a long-term virological remission after the interruption of early initiated antiretroviral therapy ANRS VISCONTI Study, PLoS Pathog 9(3) (2013) e1003211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Salgado M, Rabi SA, O’Connell KA, Buckheit RW 3rd, Bailey JR, Chaudhry AA, Breaud AR, Marzinke MA, Clarke W, Margolick JB, Siliciano RF, Blankson JN, Prolonged control of replication-competent dual-tropic human immunodeficiency virus-1 following cessation of highly active antiretroviral therapy, Retrovirology 8 (2011) 97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Gonzalo-Gil E, Ikediobi U, Sutton RE, Mechanisms of Virologic Control and Clinical Characteristics of HIV+ Elite/Viremic Controllers, Yale J Biol Med 90(2) (2017) 245–259. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hubert JB, Burgard M, Dussaix E, Tamalet C, Deveau C, Le Chenadec J, Chaix ML, Marchadier E, Vilde JL, Delfraissy JF, Meyer L, Rouzioux, Natural history of serum HIV-1 RNA levels in 330 patients with a known date of infection. The SEROCO Study Group, AIDS 14(2) (2000) 123–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Lambotte O, Boufassa F, Madec Y, Nguyen A, Goujard C, Meyer L, Rouzioux C, Venet A, Delfraissy JF, Group S-HS, HIV controllers: a homogeneous group of HIV-1-infected patients with spontaneous control of viral replication, Clin Infect Dis 41(7) (2005) 1053–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Cao Y, Qin L, Zhang L, Safrit J, Ho DD, Virologic and immunologic characterization of long-term survivors of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection, N Engl J Med 332(4) (1995) 201–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Munoz A, Kirby AJ, He YD, Margolick JB, Visscher BR, Rinaldo CR, Kaslow RA, Phair JP, Long-term survivors with HIV-1 infection: incubation period and longitudinal patterns of CD4+ lymphocytes, J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol 8(5) (1995) 496–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Pantaleo G, Menzo S, Vaccarezza M, Graziosi C, Cohen OJ, Demarest JF, Montefiori D, Orenstein JM, Fox C, Schrager LK, et al. , Studies in subjects with long-term nonprogressive human immunodeficiency virus infection, N Engl J Med 332(4) (1995) 209–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Deng K, Siliciano RF, HIV: Early treatment may not be early enough, Nature 512(7512) (2014) 35–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].A.S.S.W.G.o.H.I.V.C. International, Deeks SG, Autran B, Berkhout B, Benkirane M, Cairns S, Chomont N, Chun TW, Churchill M, Di Mascio M, Katlama C, Lafeuillade A, Landay A, Lederman M, Lewin SR, Maldarelli F, Margolis D, Markowitz M, Martinez-Picado J, Mullins JI, Mellors J, Moreno S, O’Doherty U, Palmer S, Penicaud MC, Peterlin M, Poli G, Routy JP, Rouzioux C, Silvestri G, Stevenson M, Telenti A, Van Lint C, Verdin E, Woolfrey A, Zaia J, Barre-Sinoussi F, Towards an HIV cure: a global scientific strategy, Nat Rev Immunol 12(8) (2012) 607–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ananworanich J, Chomont N, Eller LA, Kroon E, Tovanabutra S, Bose M, Nau M, Fletcher JLK, Tipsuk S, Vandergeeten C, O’Connell RJ, Pinyakorn S, Michael N, Phanuphak N, Robb ML, Rv, R.S.s. groups, HIV DNA Set Point is Rapidly Established in Acute HIV Infection and Dramatically Reduced by Early ART, EBioMedicine 11 (2016) 68–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Whitney JB, Hill AL, Sanisetty S, Penaloza-MacMaster P, Liu J, Shetty M, Parenteau L, Cabral C, Shields J, Blackmore S, Smith JY, Brinkman AL, Peter LE, Mathew SI, Smith KM, Borducchi EN, Rosenbloom DI, Lewis MG, Hattersley J, Li B, Hesselgesser J, Geleziunas R, Robb ML, Kim JH, Michael NL, Barouch DH, Rapid seeding of the viral reservoir prior to SIV viraemia in rhesus monkeys, Nature 512(7512) (2014) 74–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Crooks AM, Bateson R, Cope AB, Dahl NP, Griggs MK, Kuruc JD, Gay CL, Eron JJ, Margolis DM, Bosch RJ, Archin NM, Precise Quantitation of the Latent HIV-1 Reservoir: Implications for Eradication Strategies, J Infect Dis 212(9) (2015) 1361–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Siliciano JD, Kajdas J, Finzi D, Quinn TC, Chadwick K, Margolick JB, Kovacs C, Gange SJ, Siliciano RF, Long-term follow-up studies confirm the stability of the latent reservoir for HIV-1 in resting CD4+ T cells, Nat Med 9(6) (2003) 727–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Hill AL, Mathematical Models of HIV Latency, Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 417 (2018) 131–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Chomont N, El-Far M, Ancuta P, Trautmann L, Procopio FA, Yassine-Diab B, Boucher G, Boulassel MR, Ghattas G, Brenchley JM, Schacker TW, Hill BJ, Douek DC, Routy JP, Haddad EK, Sekaly RP, HIV reservoir size and persistence are driven by T cell survival and homeostatic proliferation, Nat Med 15(8) (2009) 893–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Maldarelli F, Wu X, Su L, Simonetti FR, Shao W, Hill S, Spindler J, Ferris AL, Mellors JW, Kearney MF, Coffin JM, Hughes SH, HIV latency. Specific HIV integration sites are linked to clonal expansion and persistence of infected cells, Science 345(6193) (2014) 179–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].FDA, The FDA approves new leukemia drug; expands use of current drug, FDA Consum 40(6) (2006) 5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Aladag E, Haznedaroglu IC, Current perspectives for the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia, Turk J Med Sci 49(1) (2019) 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Rodriguez-Mora S, Spivak AM, Szaniawski MA, Lopez-Huertas MR, Alcami J, Planelles V, Coiras M, Tyrosine Kinase Inhibition: a New Perspective in the Fight against HIV, Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 16(5) (2019) 414–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Bermejo M, Ambrosioni J, Bautista G, Climent N, Mateos E, Rovira C, Rodriguez-Mora S, Lopez-Huertas MR, Garcia-Gutierrez V, Steegmann JL, Duarte R, Cervantes F, Plana M, Miro JM, Alcami J, Coiras M, Evaluation of resistance to HIV-1 infection ex vivo of PBMCs isolated from patients with chronic myeloid leukemia treated with different tyrosine kinase inhibitors, Biochem Pharmacol 156 (2018) 248–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Cribier A, Descours B, Valadao AL, Laguette N, Benkirane M, Phosphorylation of SAMHD1 by cyclin A2/CDK1 regulates its restriction activity toward HIV-1, Cell Rep 3(4) (2013) 1036–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Coiras M, Bermejo M, Descours B, Mateos E, Garcia-Perez J, Lopez-Huertas MR, Lederman MM, Benkirane M, Alcami J, IL-7 Induces SAMHD1 Phosphorylation in CD4+ T Lymphocytes, Improving Early Steps of HIV-1 Life Cycle, Cell Rep 14(9) (2016) 2100–2107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Freeman ML, Shive CL, Nguyen TP, Younes SA, Panigrahi S, Lederman MM, Cytokines and T-Cell Homeostasis in HIV Infection, J Infect Dis 214Suppl 2 (2016) S51–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Hoffmann VS, Baccarani M, Hasford J, Lindoerfer D, Burgstaller S, Sertic D, Costeas P, Mayer J, Indrak K, Everaus H, Koskenvesa P, Guilhot J, Schubert-Fritschle G, Castagnetti F, Di Raimondo F, Lejniece S, Griskevicius L, Thielen N, Sacha T, Hellmann A, Turkina AG, Zaritskey A, Bogdanovic A, Sninska Z, Zupan I, Steegmann JL, Simonsson B, Clark RE, Covelli A, Guidi G, Hehlmann R, The EUTOS population-based registry: incidence and clinical characteristics of 2904 CML patients in 20 European Countries, Leukemia 29(6) (2015) 1336–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Patel M, Philip V, Fazel F, Lakha A, Vorog A, Ali N, Karstaedt A, Pather S, Human immunodeficiency virus infection and chronic myeloid leukemia, Leuk Res 36(11) (2012) 1334–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Campillo-Recio D, Perez-Rodriguez L, Yebra E, Cervero-Jimenez M, [Chronic myeloid leukemia treatment and human immunodeficiency virus infection], Rev Clin Esp (Barc) 214(4) (2014) 231–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].de la Tribonniere X, Leberre R, Plantier I, Alfandari S, Beuscart C, Jouet JP, Mouton Y, Chronic myelogenous leukemia in an HIV-infected patient, Infection 26(3) (1998) 194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Kest H, Brogly S, McSherry G, Dashefsky B, Oleske J, Seage GR 3rd, Malignancy in perinatally human immunodeficiency virus-infected children in the United States, Pediatr Infect Dis J 24(3) (2005) 237–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Lorand-Metze I, Morais SL, Souza CA, Chronic myeloid leukemia in a homosexual HIV-seropositive man, AIDS 4(9) (1990) 923–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Mahon FX, Nabera CB, Pellegrin JL, Cony-Makhoul P, Leng B, Bernard P, Reiffers J, Improving the cytogenetic response to interferon alpha by zidovudine (AZT) in an HIV-positive chronic myelogenous leukemia patient, Leuk Lymphoma 26(1-2) (1997) 205–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Schlaberg R, Fisher JG, Flamm MJ, Murty VV, Bhagat G, Alobeid B, Chronic myeloid leukemia and HIV-infection, Leuk Lymphoma 49(6) (2008) 1155–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Schlegel P, Beatty P, Halvorsen R, McCune J, Successful allogeneic bone marrow transplant in an HIV-1-positive man with chronic myelogenous leukemia, J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 24(3) (2000) 289–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Setty BA, Hayani KC, Sharon BI, Schmidt ML, Prolonged chronic phase of greater than 10 years of chronic myelogenous leukemia in a patient with congenital human immunodefeciency virus infection, Pediatr Blood Cancer 53(4) (2009) 658–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Tsimberidou AM, Medina J, Cortes J, Rios A, Bonnie G, Faderl S, Kantarjian H, Garcia-Manero G, Chronic myeloid leukemia in a patient with acquired immune deficiency syndrome: complete cytogenetic response with imatinib mesylate: report of a case and review of the literature, Leuk Res 28(6) (2004) 657–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Tuljapurkar VB, Phatak UA, Human immunodeficiency virus Infection in a patient of chronic myelogenous leukemia, Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 34(4) (2013) 323–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Verneris MR, Tuel L, Seibel NL, Pediatric HIV infection and chronic myelogenous leukemia, Pediatr AIDS HIV Infect 6(5) (1995) 292–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Brussel A, Sonigo P, Analysis of early human immunodeficiency virus type 1 DNA synthesis by use of a new sensitive assay for quantifying integrated provirus, J Virol 77(18) (2003) 10119–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Dismuke DJ, Aiken C, Evidence for a functional link between uncoating of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 core and nuclear import of the viral preintegration complex, J Virol 80(8) (2006) 3712–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Majumdar N, Banerjee S, Pallas M, Wessel T, Hegerich P, Poisson Plus Quantification for Digital PCR Systems, Sci Rep 7(1) (2017) 9617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Sallusto F, Lenig D, Forster R, Lipp M, Lanzavecchia A, Two subsets of memory T lymphocytes with distinct homing potentials and effector functions, Nature 401(6754) (1999) 708–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Bruner KM, Wang Z, Simonetti FR, Bender AM, Kwon KJ, Sengupta S, Fray EJ, Beg SA, Antar AAR, Jenike KM, Bertagnolli LN, Capoferri AA, Kufera JT, Timmons A, Nobles C, Gregg J, Wada N, Ho YC, Zhang H, Margolick JB, Blankson JN, Deeks SG, Bushman FD, Siliciano JD, Laird GM, Siliciano RF, A quantitative approach for measuring the reservoir of latent HIV-1 proviruses, Nature 566(7742) (2019) 120–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Kinloch NN, Ren Y, Conce Alberto WD, Dong W, Khadka P, Huang SH, Mota TM, Wilson A, Shahid A, Kirkby D, Harris M, Kovacs C, Benko E, Ostrowski MA, Del Rio Estrada PM, Wimpelberg A, Cannon C, Hardy WD, MacLaren L, Goldstein H, Brumme CJ, Lee GQ, Lynch RM, Brumme ZL, Jones RB, HIV-1 diversity considerations in the application of the Intact Proviral DNA Assay (IPDA), Nat Commun 12(1) (2021) 165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Peluso MJ, Bacchetti P, Ritter KD, Beg S, Lai J, Martin JN, Hunt PW, Henrich TJ, Siliciano JD, Siliciano RF, Laird GM, Deeks SG, Differential decay of intact and defective proviral DNA in HIV-1-infected individuals on suppressive antiretroviral therapy, JCI Insight 5(4) (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Ho YC, Shan L, Hosmane NN, Wang J, Laskey SB, Rosenbloom DI, Lai J, Blankson JN, Siliciano JD, Siliciano RF, Replication-competent noninduced proviruses in the latent reservoir increase barrier to HIV-1 cure, Cell 155(3) (2013) 540–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Henrich TJ, Hanhauser E, Marty FM, Sirignano MN, Keating S, Lee TH, Robles YP, Davis BT, Li JZ, Heisey A, Hill AL, Busch MP, Armand P, Soiffer RJ, Altfeld M, Kuritzkes DR, Antiretroviral-free HIV-1 remission and viral rebound after allogeneic stem cell transplantation: report of 2 cases, Ann Intern Med 161(5) (2014) 319–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Luzuriaga K, Gay H, Ziemniak C, Sanborn KB, Somasundaran M, Rainwater-Lovett K, Mellors JW, Rosenbloom D, Persaud D, Viremic relapse after HIV-1 remission in a perinatally infected child, N Engl J Med 372(8) (2015) 786–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Bermejo M, Lopez-Huertas MR, Garcia-Perez J, Climent N, Descours B, Ambrosioni J, Mateos E, Rodriguez-Mora S, Rus-Bercial L, Benkirane M, Miro JM, Plana M, Alcami J, Coiras M, Dasatinib inhibits HIV-1 replication through the interference of SAMHD1 phosphorylation in CD4+ T cells, Biochem Pharmacol 106 (2016) 30–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Salgado M, Martinez-Picado J, Galvez C, Rodriguez-Mora S, Rivaya B, Urrea V, Mateos E, Alcami J, Coiras M, Dasatinib protects humanized mice from acute HIV-1 infection, Biochem Pharmacol 174 (2020) 113625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Kulpa DA, Talla A, Brehm JH, Ribeiro SP, Yuan S, Bebin-Blackwell AG, Miller M, Barnard R, Deeks SG, Hazuda D, Chomont N, Sekaly RP, Differentiation into an Effector Memory Phenotype Potentiates HIV-1 Latency Reversal in CD4(+) T Cells, J Virol 93(24) (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Benito JM, Lopez M, Lozano S, Gonzalez-Lahoz J, Soriano V, Down-regulation of interleukin-7 receptor (CD127) in HIV infection is associated with T cell activation and is a main factor influencing restoration of CD4(+) cells after antiretroviral therapy, J Infect Dis 198(10) (2008) 1466–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Tremeaux P, Lenfant T, Boufassa F, Essat A, Melard A, Gousset M, Delelis O, Viard JP, Bary M, Goujard C, Rouzioux C, Meyer L, Avettand-Fenoel V, Anrs S, cohorts P, Increasing contribution of integrated forms to total HIV DNA in blood during HIV disease progression from primary infection, EBioMedicine 41 (2019) 455–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Zerbato JM, McMahon DK, Sobolewski MD, Mellors JW, Sluis-Cremer N, Naive CD4+ T Cells Harbor a Large Inducible Reservoir of Latent, Replication-competent Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1, Clin Infect Dis 69(11) (2019) 1919–1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Venanzi Rullo E, Cannon L, Pinzone MR, Ceccarelli M, Nunnari G, O’Doherty U, Genetic Evidence That Naive T Cells Can Contribute Significantly to the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Intact Reservoir: Time to Re-evaluate Their Role, Clin Infect Dis 69(12) (2019) 2236–2237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].De Boer RJ, Perelson AS, Quantifying T lymphocyte turnover, J Theor Biol 327 (2013) 45–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Barton K, Winckelmann A, Palmer S, HIV-1 Reservoirs During Suppressive Therapy, Trends Microbiol 24(5) (2016) 345–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Lorenzo-Redondo R, Fryer HR, Bedford T, Kim EY, Archer J, Pond SLK, Chung YS, Penugonda S, Chipman J, Fletcher CV, Schacker TW, Malim MH, Rambaut A, Haase AT, McLean AR, Wolinsky SM, Persistent HIV-1 replication maintains the tissue reservoir during therapy, Nature 530(7588) (2016) 51–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].EMA, SPRYCEL EPAR Product information. [Google Scholar]

- [70].Ambrosioni J, Coiras M, Alcami J, Miro JM, Potential role of tyrosine kinase inhibitors during primary HIV-1 infection, Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 15(5) (2017) 421–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].EMEA, Sprycel: EPAR - Scientific Discussion, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human (2006).

- [72].Johnson FM, Agrawal S, Burris H, Rosen L, Dhillon N, Hong D, Blackwood-Chirchir A, Luo FR, Sy O, Kaul S, Chiappori AA, Phase 1 pharmacokinetic and drug-interaction study of dasatinib in patients with advanced solid tumors, Cancer 116(6) (2010) 1582–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Nguyen T, McNicholl I, Custodio JM, Szwarcberg J, Piontkowsky D, Drug Interactions with Cobicistat- or Ritonavir-Boosted Elvitegravir, AIDS Rev 18(2) (2016) 101–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Stolbach A, Paziana K, Heverling H, Pham P, A Review of the Toxicity of HIV Medications II: Interactions with Drugs and Complementary and Alternative Medicine Products, J Med Toxicol 11(3) (2015) 326–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Salgado M, Kwon M, Galvez C, Badiola J, Nijhuis M, Bandera A, Balsalobre P, Miralles P, Buno I, Martinez-Laperche C, Vilaplana C, Jurado M, Clotet B, Wensing A, Martinez-Picado J, Diez-Martin JL, IciStem C, Mechanisms That Contribute to a Profound Reduction of the HIV-1 Reservoir After Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplant, Ann Intern Med 169(10) (2018) 674–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]