Abstract

Childhood maltreatment is linked to Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in adulthood. Neural attention network function contributes to resilience against PTSD following maltreatment; oxytocin administration alters functional connectivity differentially among resilient to PTSD groups. The present study examined intrinsic connectivity between ventral and dorsal neural attention networks (VAN and DAN) to clarify the nature of dysfunction versus resilience in the context of maltreatment-related PTSD, and to explore differential dysfunction related to varied aspects of maltreatment. Oxytocin administration was examined as a factor in these relationships. Resting-state functional connectivity data were collected from 39 adults with maltreatment histories, with and without PTSD, who were randomly assigned to receive oxytocin or placebo. We found that PTSD and sexual abuse (SA) were associated with reduced VAN-DAN connectivity. There were no significant effects with regard to physical abuse. Oxytocin was associated with greater VAN-DAN connectivity strength. These preliminary findings suggest dysfunction within attentional systems in PTSD, as well as following SA. Further, oxytocin may help ameliorate attentional neurocircuitry dysfunction in individuals with PTSD and those with maltreatment histories.

Keywords: Childhood maltreatment, Oxytocin, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Ventral attention network, Dorsal attention network, Resting-state functional connectivity

1. Introduction

Childhood trauma, including maltreatment, is strongly linked to Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in adulthood (Goldstein et al., 2016). A substantial proportion of individuals with childhood physical or sexual abuse histories develop PTSD, and maltreatment is one of the most commonly reported trauma exposures among individuals with PTSD (Goldstein et al., 2016; Kessler et al., 2014). Childhood maltreatment is associated with lasting impairment in part because of the vulnerability of the developing brain (Arnow, 2004; Teicher and Samson, 2016; Teicher et al., 2016). Understanding its neural impact and identifying factors that contribute to resilience against PTSD development following maltreatment is necessary to inform intervention efforts. Neural attention network function represents a potential factor contributing to resilience against PTSD following childhood maltreatment.

Altered functional connectivity in brain networks that support attention capacities represents a potential factor differentiating trauma-exposed individuals with and without PTSD (trauma-exposed controls; TEC) (Aupperle et al., 2012; Block and Liberzon, 2016). Attention is a complex phenomenon orchestrated by several large-scale neural networks, and how their interplay differentiates PTSD and TEC individuals is unclear. The ventral and dorsal attention networks (VAN and DAN, respectively) are involved in the orientation and shifting of attention (Corbetta and Shulman, 2002; Petersen and Posner, 2012; Seeley et al., 2007; Vossel et al., 2014). VAN is implicated in the alerting aspect of attention and includes cortical regions in the temporoparietal junction and ventral frontal cortex. DAN is implicated in the orienting aspect of attention—specifically, “voluntary” spatial attention allocation. DAN includes cortical regions in the frontal eye fields (the intersection of middle frontal and precentral gyri) and superior, lateral parietal cortex (e.g., close to the intraparietal sulcus). Studies examining VAN and DAN involvement in PTSD-related attentional dysfunction have yielded mixed findings with regard to directionality of VAN and DAN activity in resiliency against PTSD. Some studies have reported decreased VAN and DAN activation to emotional stimuli in PTSD patients versus TEC and non-trauma-exposed controls (NTC) (Blair et al., 2013). Others have reported increased DAN activation (Fani et al., 2012) and/or increased VAN activation (Thomaes, 2013) to threat cues in PTSD patients versus TEC during cognitive tasks (Fani et al., 2012). Moreover, some prior work suggests greater PTSD symptom severity is associated with greater DAN activity, but decreased VAN activity, to emotional distractors in a cognitive task (Hayes et al., 2009). Other work suggests greater PTSD symptom severity is associated with greater VAN activation to trauma-relevant stimuli (Morey et al., 2008), and greater VAN and DAN activation to emotional stimuli during cognitive tasks (White et al., 2015). Attention system functional differences in resiliency against PTSD are apparent even outside the context of emotional stimuli (Block et al., 2019).

Differences observed in task-related activation studies may be driven in part by task demands and other cognitive factors, highlighting the importance of using intrinsic functional connectivity at rest (resting-state functional connectivity; rsFC) to examine large-scale attention networks. Indeed, rsFC varies as a function of PTSD in brain regions associated with attention. Compared to TEC, individuals with PTSD show decreased VAN and DAN rsFC (Kennis et al., 2016; Yin et al., 2011) but increased rsFC within visual attention regions (Kennis et al., 2016). Regarding connectivity with other attentional systems, relative to TEC, individuals with PTSD show increased rsFC between VAN, DAN, and salience network, another large-scale neural network involved in attention coordination (Block and Liberzon, 2016).

Few studies to date have investigated differential functional connectivity in individuals with PTSD specifically related to childhood maltreatment, compared to TEC. Previous literature suggests the potential for maltreatment to exert lasting deleterious effects on a variety of neural systems, including brain regions involved in attention (Teicher and Samson, 2016). Attentional systems are among the latest to develop in childhood, and therefore may be particularly susceptible to influence from adverse experiences (Rubia, 2013; Shaw et al., 2008). Indeed, reduced DAN activation during response-control tasks has been reported as a function of childhood maltreatment severity (Blair et al., 2019), and individuals with maltreatment histories show lower functional connectivity in VAN and DAN regions compared to individuals without maltreatment histories during sustained attention tasks (Hart et al., 2017; Lim et al., 2016). Further, differential forms of maltreatment—such as different types of abuse—may be associated with varied patterns of attention network dysfunction. For example, reduced cerebral blood flow to DAN regions has been reported among individuals with sexual abuse (SA)-related PTSD compared to TEC with SA histories during response-control tasks (Bremner et al., 2004). Among depressed adults, childhood physical abuse (PA) history was associated with greater VAN-DAN rsFC (Yu et al., 2019). However, rsFC between VAN and DAN as a function of varied aspects of childhood maltreatment (i.e., PA versus SA) has not been examined in the context of susceptibility to PTSD specifically.

Given the interpersonal nature of childhood maltreatment, an important factor to consider is the role of the social and affiliative hormone oxytocin in resilience against PTSD. The oxytocin system is involved in stress response and is subject to alteration following psychosocial trauma (Donadon et al., 2018; Sippel et al., 2017). Intranasal oxytocin has been proposed as a potential PTSD treatment agent and a possible preventive agent following trauma exposure (Yoon and Kim, 2019) given that oxytocin administration is associated with differences in functional connectivity of regions associated with salience and emotional processing (Frijling, 2017; Koch et al., 2016). Previous studies have found that effects of oxytocin administration on fearful face processing and working memory were more pronounced in individuals with PTSD versus TEC (Flanagan et al., 2018; Flanagan et al., 2019). Further examination of differential neural attention network responsiveness to oxytocin between TEC and PTSD individuals is essential to both understanding the role of oxytocin in resilience against psychopathology, and enhancing precision of oxytocin as a potential PTSD treatment agent.

The present study examined rsFC between VAN and DAN as a function of PTSD versus TEC, childhood maltreatment type (PA versus SA), and oxytocin administration (versus placebo). Oxytocin was administered in a randomized, double-blind, between-subjects design. Childhood maltreatment was determined retrospectively. Given that VAN and DAN are thought to work synergistically in a “push-pull” manner to flexibly control attentional processes (Vossel et al., 2014), and that compromised attentional shifting is often reported in PTSD (Block and Liberzon, 2016), we hypothesized that individuals with PTSD would show reduced VAN-DAN rsFC. Given that oxytocin has the potential to ameliorate dysfunctional connectivity associated with PTSD (Flanagan et al., 2018; Frijling, 2017; Koch et al., 2016), we hypothesized that oxytocin administration would ameliorate this reduced connectivity. Further, based on existing literature, we hypothesized that individuals with high childhood SA levels would show reduced VAN-DAN rsFC (Bremner et al., 2004), and that individuals with high childhood PA levels would show increased VAN-DAN rsFC (Yu et al., 2019). We hypothesized that oxytocin administration would reduce connectivity differences between groups with high versus low SA or PA.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants were 39 individuals (59% female) recruited via local media advertisements. Childhood trauma-related inclusion criteria included: (1) scores ranging from moderate-severe (>3) on one or more items in the five trauma domains of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ (Bernstein et al., 2003), and (2) meeting Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV (DSM-IV) Criterion A related to childhood trauma (i.e., exposure to an event prior to age 18 that involved actual or threatened death or serious injury or threat to self or others’ physical integrity, with a response of intense fear, helplessness, and/or horror—as determined by PTSD diagnostic assessments described in Measures). Further, PTSD group participants were required to meet DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for current PTSD (i.e., in the last six months). The Supplement provides detailed exclusion criteria for the overall study, and specific to the TEC group. Eight participants with missing or poor quality structural and/or functional data were excluded from analyses (4 PTSD; 4 TEC). The final sample was comprised of 31 participants, including 15 in the PTSD group and 16 in the TEC group.

2.2. Measures

PTSD diagnosis was assessed using the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS; Blake et al., 1995) or the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale (PTDS; Foa et al., 1997) to reduce participant burden. PTSD diagnostic assessments were linked to a childhood index trauma. In the current sample, 8 participants completed the CAPS (3 PTSD; 5 TEC); the remaining 31 participants completed the PTDS. A physician-administered history and physical examination was conducted to assess safety and eligibility. Psychiatric exclusions and other disorders were assessed using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (Shehan et al., 1998) and Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (First et al., 1994).

The CTQ assessed severity of exposure to childhood maltreatment. In this study, we examined the effect of SA and PA on functional connectivity. High and low SA and PA were defined using a sample median split; high SA was defined as a score of ≥15 on the SA subscale, and high PA a score of ≥12 on the PA subscale.

2.3. Procedures

Participants were randomly assigned in a double-blind manner to receive oxytocin or placebo on study visits 1 and 2 in a counter-balanced fashion. The resting-state fMRI scan (rsfMRI), analyzed in the current study, was only completed during visit 1. Thus, the manipulation of oxytocin versus placebo was between-subjects and cross-sectional for the present analyses. Study procedures are described in depth elsewhere (Flanagan et al., 2019), and in the Supplement. Procedures were approved by the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) Institutional Review Board and conducted in alignment with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to study procedures. The MUSC research pharmacy was responsible for randomization, as well as compounding and dispensing oxytocin nasal spray (24 IU; Spengler et al., 2017) and matching saline placebo. Participants were supervised by research staff while self-administering nasal sprays approximately 45 min prior to scanning.

2.4. fMRI Image Acquisition

Data were acquired on a Siemens Trio 3.0-T scanner using a 12-channel head coil (Siemens Medical, Erlangen, Germany). The Supplement provides detailed acquisition information.

Participants completed one 6-min rsfMRI session during the study visit (an emotion faces task was also completed during the scanning session; results are reported elsewhere (Flanagan et al., 2019)). Participants were instructed to fixate on a centrally-presented crosshair, remain awake and alert, and minimize head movement; no other specific instructions were provided to participants.

2.5. Statistical Methods

2.5.1. fMRI data preprocessing and individual-level analysis.

rsfMRI data were preprocessed using FMRI Expert Analysis Tool (FEAT) Version 5.98, part of FMRIB’s Software Library (FSL 5.0.9; Smith et al., 2004). The Supplement provides detailed information on pre-processing and individual-level analysis.

Following preprocessing, individual-level regression analyses, parcellation, and removal of outliers, twenty nodes of interest were grouped into two conceptual subnetworks (Table 1): VAN and DAN. Although there are varied interpretations of which brain regions comprise VAN and DAN, in the present study, we use the data-driven Power (2011) atlas to define these networks. VAN consisted of nine nodes which included supplemental motor area/superior frontal gyrus, bilateral superior and middle temporal gyrus, and bilateral inferior frontal gyrus. DAN consisted of eleven nodes which included precuneus, occipital cortex, parietal cortices, middle and superior frontal gyri, temporooccipital gyrus, and precentral gyrus. VAN and DAN nodes overlapped with regions consistently activated during tasks involving each of these networks (Corbetta et al., 2008; Fox et al., 2006; Yeo et al., 2011).

Table 1.

Nodes of Interest Comprising VAN and DAN Subnetworks.

| Brain Region | MNI x | MNI y | MNI z | BA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAN | L. Supplemental Motor Area (Superior Frontal Gyrus) | −10 | 11 | 67 | 6 |

| R. Superior Temporal Gyrus | 54 | −43 | 22 | 42 | |

| R. (Posterior) Superior Temporal Gyrus | 52 | −33 | 8 | 22 | |

| L. Superior Temporal Cortex | −55 | −40 | 14 | 42 | |

| R. Middle Temporal Gyrus | 56 | −46 | 11 | 22 | |

| R. (Posterior) Middle Temporal Gyrus | 51 | −29 | −4 | 21 | |

| L. Middle Temporal Gyrus | −56 | −50 | 10 | 21 | |

| R. Inferior Frontal Gyrus | 53 | 33 | 1 | 45 | |

| L. Inferior Frontal Cortex | −49 | 25 | −1 | 47 | |

|

| |||||

| DAN | R. Precuneus | 10 | −62 | 61 | 7 |

| L. Precuneus | −27 | −71 | 37 | 7 | |

| R. Middle Temporal Gyrus | 46 | −59 | 4 | 37 | |

| L. Middle Temporal Cortex | −52 | −63 | 5 | 37 | |

| R. Superior Occipital Cortex | 22 | −65 | 48 | 7 | |

| R. Superior Parietal Cortex | 25 | −58 | 60 | 7 | |

| L. Inferior Parietal Cortex | −33 | −46 | 47 | 40 | |

| L. Middle Frontal Gyrus | −32 | −1 | 54 | 6 | |

| L. Inferior Temporal Gyrus | −42 | −60 | −9 | 37 | |

| L. Superior Frontal Cortex | −17 | −59 | 64 | 5 | |

| R. Precentral Gyrus | 29 | −5 | 54 | 6 | |

Note: BA=Brodmann’s Area, DAN=Dorsal Attention Network, L.=left, MNI=Montreal Neurological Institute template (x, y, z coordinates), R.=right, VAN=Ventral Attention Network.

To account for connectivity between nodes of interest and other nodes in the brain, 294 nodes representing a whole-brain network—the 264 regions from Power et al (2011) with 30 additional subcortical regions (amygdala, hippocampus, striatum)—were used. A 294x294 weighted, signed functional connectivity matrix was computed; this matrix represented a fully connected, undirected graph. Each matrix element, or edge weight, represented the partial correlation between two rsfMRI time series (e.g., between nodes one and two in VAN), controlling for time series in all other nodes. Given that outlier removal procedures reduced the number of time points in each participant’s rsfMRI data, a shrinkage factor was applied to create a covariance matrix (Schäfer and Strimmer, 2005).

Fisher’s r to z transformation (Fisher, 1915) was applied to each subject’s whole-brain, partial correlation matrices. For each subject, each partial z-score represented an edge weight between one node and another, controlling for all other nodes in the whole-brain network. Given our focus on attention network dynamics, between-subnetwork averages were generated to reflect between-subnetwork connectivity. The mean of the edge weights between all nodes in a given subnetwork with all nodes in another subnetwork was used as a measure of the average between-subnetwork connectivity for each subject. Between-subnetwork connectivity was calculated for VAN-DAN subnetworks.

2.5.2. Group-level fMRI data analysis.

We examined effects of diagnostic group, different forms of maltreatment, and oxytocin administration on rsFC. Analyses examined VAN-DAN connectivity as dependent variables; connectivity was defined as the average edge weights associated with VAN-DAN.

Effects of diagnostic group and oxytocin on functional connectivity were examined in a full factorial 2 (PTSD or TEC)-by-2 (Oxytocin or Placebo) ANOVA using SPSS version 25 (IBM Corporation, 2017). Effects of childhood SA and oxytocin on functional connectivity were examined in a full factorial 2 (SA: Low or High)-by-2 (Oxytocin or Placebo) ANOVA. Effects of childhood PA and oxytocin on functional connectivity were examined in a full factorial 2 (PA: Low or High)-by-2 (Oxytocin or Placebo) ANOVA. ANOVAs were followed up with post-hoc t-tests to characterize interactions. Tests conducted were considered significant at p<.05, FDR corrected (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995).

3. Results

Table 2 presents sample demographics. PTSD and TEC groups were matched on age, sex, education, and smoking status (smoker vs. non-smoker), ps=.438-.905. Head motion did not significantly differ between PTSD and TEC groups (p=.319). Five participants in the PTSD group endorsed secondary psychiatric diagnoses, including Alcohol Use Disorder (n=1), Panic Disorder (n=1), Major Depression (n=1), Dysthymia (n=1), and Pre-Menstrual Dysphoric Disorder (n=1). PTSD diagnosis occurred significantly more frequently among individuals with high PA levels (p=.019), but not high SA levels (p=.104). Frequency of PTSD diagnosis, high SA level, and high PA level did not significantly differ by sex (ps=.210-.594).

Table 2.

Sample demographics.

| PTSD (n=15) | TEC (n=16) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age | M(SD)=35.87(9.96) | M(SD)=36.38(13.10) | .90 |

| Sex | 46.67% female | 56.25% female | .59 |

| Highest Education Level | .44 | ||

| College Graduate | 53.33% | 43.75% | |

| Some Graduate School | 0% | 12.5% | |

| Some College | 26.67% | 37.5% | |

| High School Graduate | 13.33% | 6.25% | |

| Some High School | 6.67% | 0% | |

| Smoking Status | 13.33% smokers | 18.75% smokers | .68 |

| High PA Status | 67% PA | 31% PA | .02 |

| High SA Status | 67% SA | 60% SA | .10 |

| Oxytocin Status | 40% OT | 44% OT | .83 |

Note: OT=Oxytocin, PA=Physical Abuse, PTSD=Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, SA=Sexual Abuse, TEC=Trauma-Exposed Controls, p-values are derived from difference tests between PTSD and TEC groups.

3.1. fMRI Results

The following key effects (Table 3) were observed:

Table 3.

Model results predicting average edge weight between Ventral and Dorsal Attention Networks (VAN and DAN).

| Model | Effect | F (1, 27) | p-value | ηp2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTSD | Intercept | 5.948 | .248 | .856 |

| Drug | 340.256 | .034 | .997 | |

| PTSD | 362.898 | .033 | .997 | |

| Drug x PTSD | 0.026 | .872 | .001 | |

|

| ||||

| SA | Intercept | 9.826 | .197 | .908 |

| Drug | 58695.265 | .003 | 1.000 | |

| SA | 29026.871 | .004 | 1.000 | |

| Drug x SA | 0.000 | .989 | .000 | |

|

| ||||

| PA | Intercept | 109.698 | .061 | .991 |

| Drug | 5.074 | .266 | .835 | |

| PA | 0.263 | .698 | .208 | |

| Drug x PA | 1.672 | .207 | .058 | |

Note: PTSD=Posttraumatic Stress Disorder; SA=sexual abuse; PA=physical abuse; ηp2=partial eta squared. Uncorrected p-values are presented; corrected p-values are provided in the Results section.

3.1.1. PTSD-by-drug analysis

3.1.1.1. Main effect of PTSD status:

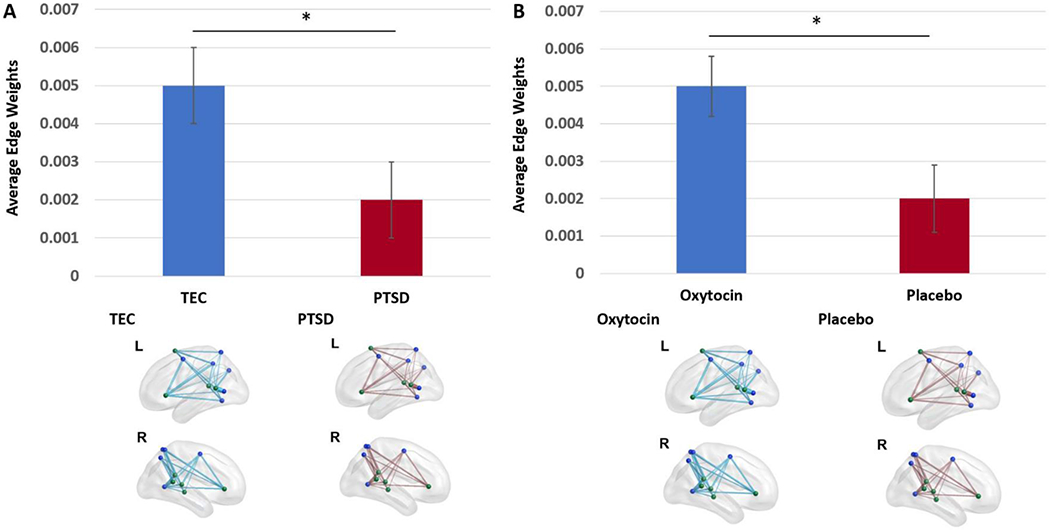

There was a significant main effect of PTSD status on the average edge weight between nodes in VAN and DAN at an uncorrected threshold (F(1,27)=362.90, uncorrected p=.033), but not at a corrected threshold (corrected p=.085). TEC showed stronger average edge weights for VAN-DAN connectivity relative to individuals with PTSD (M(SD)TEC=.005(.003); M(SD)PTSD =.002(.003)). See Figure 1A.

Figure 1. PTSD-by-Drug Analysis: Main Effect of PTSD (A) and Drug (B) on VAN-DAN Connectivity.

Note: TEC=Trauma-Exposed Control; PTSD=Posttraumatic Stress Disorder; *=p<05 uncorrected. These main effects were not significant at a corrected threshold. DAN nodes are shown in blue. VAN nodes are shown in green. For a given group, each edge represents the average edge weight between two nodes for participants belonging to that group. Edge thickness represents connection strength. The lower of the two groups is displayed in red. Plot whiskers represent standard error.

3.1.1.2. Main effect of drug:

There was a significant main effect of oxytocin administration on the average edge weight between nodes in VAN and DAN (F(1,27)=340.26, uncorrected p=.034) but not at a corrected threshold (corrected p=.085). Individuals in the oxytocin group showed stronger average edge weights for VAN-DAN connectivity relative to individuals exposed to placebo (M(SD)Oxytocin=.005(.003); M(SD)Placebo =.002(.003)). See Figure 1B.

3.1.1.3. PTSD-by-drug interaction:

The PTSD-by-drug interaction effect on the average edge weights between nodes in VAN and DAN was not significant.

3.1.2. SA-by-drug analysis

3.1.2.1. Main effect of childhood SA:

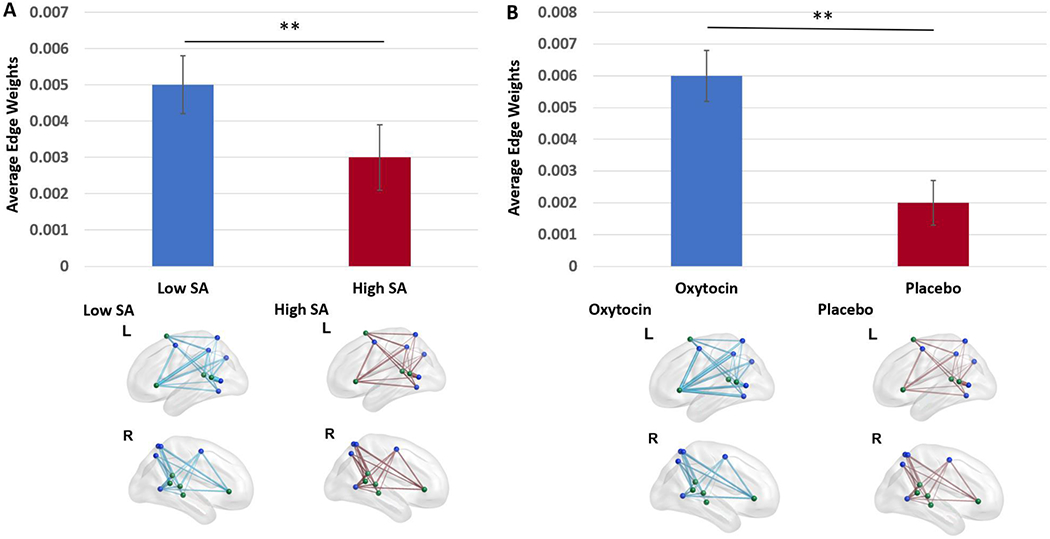

There was a significant main effect of high versus low SA on average edge weights between VAN and DAN (F(1,27)=29026.87, uncorrected p=.004) which survived correction for multiple comparisons (corrected p=.02). High SA levels were associated with reduced average edge weights between VAN-DAN compared to low SA levels (t(30)=2.31, p=029; M(SD)Low SA=004(.003); M(SD)High SA =.003(.003)). See Figure 2A.

Figure 2. Sexual Abuse-by-Drug Analysis: Main Effects of Sexual Abuse (A) and Drug (B) on VAN-DAN connectivity.

Note: SA=Sexual Abuse; **=p<.005 uncorrected. These main effects were significant at a corrected threshold. DAN nodes are shown in blue. VAN nodes are shown in green. For a given group, each edge represents the average edge weight between two nodes for participants belonging to that group. Edge thickness represents connection strength. The lower of the two groups is displayed in red. Plot whiskers represent standard error.

3.1.2.2. Main effect of drug:

There was a significant main effect of oxytocin administration on the average edge weight between nodes in VAN and DAN (F(1,27)=58695.27, uncorrected p=.003) which survived correction for multiple comparisons (corrected p=.02). Individuals in the oxytocin group showed stronger average edge weights for VAN-DAN functional connectivity relative to individuals exposed to placebo (t(30)=3.28, p=.003; M(SD)Oxytocin=.005(.003); M(SD)Placebo =.002(.003)). See Figure 2B.

3.1.2.3. SA-by-drug interaction:

There were no SA-by-oxytocin administration interaction effects on the average edge weights between VAN and DAN.

3.1.3. PA-by-drug analysis

There were no significant main effects of childhood PA or oxytocin administration, and no PA-by-drug interaction effects, on the average edge weights between nodes in VAN and DAN.

4. Discussion

The present study examined rsFC between VAN and DAN as a function of PTSD, childhood maltreatment type, and oxytocin. Overall, PTSD and high childhood SA levels were associated with reduced VAN-DAN connectivity strength. There were no significant effects, however, with regard to PA. Overall, oxytocin administration was associated with greater VAN-DAN connectivity strength.

Analyses examined VAN-DAN connectivity. VAN and DAN are hypothesized to work synergistically to flexibly control attentional processes (Vossel et al., 2014). In line with our hypotheses, PTSD was associated with reduced VAN-DAN connectivity strength. Task-based fMRI work has indicated that individuals with PTSD show reduced activity within top-down attentional networks relative to TEC and NTC (Blair et al., 2013; Fani et al., 2012). Furthermore, rsfMRI data have indicated reduced VAN-DAN connectivity in individuals with PTSD relative to TEC (Kennis et al., 2016; Yin et al., 2011). Overall, the current data add to a growing body of literature indicating dysfunction within attentional networks in individuals with PTSD. Specifically, the current study shows that VAN-DAN connectivity is compromised in PTSD.

In the present study, individuals with high childhood SA levels showed reduced VAN-DAN connectivity compared to individuals with low childhood SA. This finding suggests that a significant SA history is associated with dysfunction in the coordination of systems involved in orientation and shifting of attention. Our findings support and extend existing literature examining VAN-DAN functional connectivity during attention tasks (Hart et al., 2017; Lim et al., 2016). Specifically, one study using an affective Stroop task showed that higher childhood SA level was associated with reduced activity within parietal regions mediating top-down attention in cognitively demanding task conditions (Blair et al., 2019). In the same study, higher childhood SA level was also associated with increased activity within brain regions that mediate attention to emotional stimuli, such as rostromedial prefrontal cortex. In a sample of substance-dependent women, sexual trauma was associated with reduced connectivity between orbitofrontal cortex and regions involved in attentional control, such as middle frontal gyrus, precuneus, and posterior cingulate cortex, during an interoceptive attention task (Poppa et al., 2019). As the present study involves rsfMRI rather than active tasks, further work is needed to explore intrinsic attentional system dynamics.

Notably, however, there were no associations between PA and dysfunctional connectivity involving attentional networks. This is inconsistent with literature indicating dysfunction within attentional networks in individuals with greater PA histories (Blair et al., 2019; Yu et al., 2019). Although prior work has shown childhood PA to be associated with dysfunction in attentional regions, there was a substantially smaller effect size associated with PA relative to SA (Blair et al., 2019). It is possible the absence of such effects within the current study is associated with its smaller sample size and inability to detect smaller effects. Additionally, although one study (Yu et al., 2019) found greater connectivity within attentional networks in individuals with elevated PA levels, it was conducted primarily in depressed individuals. In summary, findings indicate that significant childhood SA levels are associated with dysfunction in attentional network connectivity. We speculate that these findings are associated with dysfunction in the coordination of attention—including systems and regions underlying the coordination of attention towards emotional stimuli (e.g., VAN, DAN)—and that type of trauma exposure differentially impacts dysfunctions across different neurocircuitry.

The present study also examined associations between oxytocin administration and rsFC within this sample of adults with childhood maltreatment histories. Oxytocin administration was associated with greater VAN-DAN connectivity among all individuals,. The first finding aligned with our hypothesis that oxytocin would strengthen VAN-DAN connectivity, as the current data also indicate that PTSD diagnosis is associated with reduced VAN-DAN connectivity. Our findings support a previous study indicating that oxytocin administration results in enhanced connectivity within VAN (Brodmann et al., 2017).

Disrupted attention in the form of reduced VAN-DAN connectivity may interfere with the ability to hold one’s attention or shift attention away from input that would not typically be relevant, particularly perceived trauma- or threat-related input. This attribution maps onto PTSD symptom manifestations at the behavioral level, such as attentional bias toward trauma-related cues, hyperarousal in response to both neutral and trauma-related cues, avoidant behavior, and re-experiencing symptoms such as flashbacks and nightmares. Attention retraining, as well as treatments aimed at improving top-down attentional control, may represent intervention avenues for individuals with both PTSD and high childhood SA levels—which is associated with a similar pattern of dysfunction to PTSD in this sample. Indeed, evidence-supported behavioral treatments aim to target these issues (Goodnight et al., 2019; Sripada et al., 2016; Stojek et al., 2018) but fewer studies have examined specific neural mechanisms of treatment. Findings suggest oxytocin also holds potential for reducing discrepancies in VAN-DAN function between TEC and those who developed PTSD related to childhood maltreatment.

Findings should be interpreted in light of several limitations. The sample was relatively small. Group sizes were further reduced when considering SA and PA subgroups. This may have precluded detection of some hypothesized effects. Replication within a larger sample is necessary. Further, changing PTSD diagnostic assessments during the study may have impacted participant reporting. Both the CAPS and PTDS have excellent psychometric properties and are frequently used in assessing PTSD; however, future work should replicate findings with a consistent design across participants. PTSD diagnosis was also more common among individuals with high PA levels (68.75% versus 25% in high and low PA groups, respectively). This difference may have affected the ability to disentangle effects related to PTSD versus PA (though PA model results were not significant), and highlights the need for further research specifically focused on forms of abuse. In a supplemental analysis, PA (High or Low PA) was included in the PTSD-by-drug model as a between-subjects control variable. PTSD versus TEC differences in VAN-DAN connectivity were significant when controlling for PA; oxytocin versus placebo differences and the PTSD-by-drug interaction were not significant when controlling for PA (see Supplement). Further, oxytocin administration was randomized between subjects, rather than utilizing a cross-over design. Replication efforts should employ a within-subjects design for in-depth probing of hypothesized interaction effects. Relatedly, the oxytocin effects in the present study are main effects of oxytocin, and do not represent differential responses to oxytocin in individuals with PTSD versus TEC. Future work should investigate whether there is a difference in the effects of oxytocin in various trauma-exposed populations versus NTC. TEC may have compensated for the negative effects of maltreatment by engaging attentional or affective systems in unconventional ways compared to NTC. Therefore, a normative comparison would be instrumental in understanding whether oxytocin or other treatments can “normalize” attentional network function in PTSD or if the effects of these treatments induce reorganization and compensation, similar to resilient individuals. Finally, behavioral measures of attention were not collected; future work should assess behavioral indices of attention associated with VAN and DAN to ascertain how rsFC may be related to impairment or resilience in daily life.

In summary, the current study found that (a) PTSD is associated with reduced VAN-DAN connectivity; (b) childhood SA is associated with reduced VAN-DAN connectivity; and (c) oxytocin administration is associated with VAN-DAN connectivity in maltreated individuals without PTSD. These findings may reflect dysfunction within attentional systems in PTSD, particularly with regard to PTSD associated with childhood SA. Furthermore, oxytocin administration should be explored as a way to ameliorate attentional neurocircuitry dysfunction in individuals with PTSD, including patients with childhood maltreatment histories.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

The overall project was supported by a NIMH grant (R21MH099619) to Dr. Moran-Santa Maria (Principal Investigator); Dr. Joseph was also supported by this grant as a Co-Investigator. The following authors’ efforts in the development of this manuscript were supported by grant funding: Dr. Crum (NIMH T32 MH018869-31; NIDA U54DA016511); Dr. Flanagan (NIAAA K23AA023845); Dr. Back (NIDA K02DA039229).

Disclosures:

The authors report no direct biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest in the development of this manuscript. Dr. Moran-Santa Maria is affiliated with Teva Pharmaceuticals. As noted in Acknowledgments, several grants supported the authors involved in this work, and the development of the overall project from which these data were obtained.

References

- Arnow BA, 2004. Relationships between childhood maltreatment, adult health and psychiatric outcomes, and medical utilization. Journal of clinical psychiatry 65, 10–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aupperle RL, Melrose AJ, Stein MB, Paulus MP, 2012. Executive function and PTSD: Disengaging from trauma. Neuropharmacology 62, 686–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y, 1995. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal statistical society: series B (Methodological) 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T, Stokes J, Handelsman L, Medrano M, Desmond D, 2003. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child abuse & neglect 27, 169–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair K, Vythilingam M, Crowe S, McCaffrey D, Ng P, Wu C, Scaramozza M, Mondillo K, Pine D, Charney D, 2013. Cognitive control of attention is differentially affected in trauma-exposed individuals with and without post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychological medicine 43, 85–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair KS, Aloi J, Crum K, Meffert H, White SF, Taylor BK, Leiker EK, Thornton LC, Tyler PM, Shah N, 2019. Association of different types of childhood maltreatment with emotional responding and response control among youths. JAMA network open 2, e194604–e194604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Gusman FD, Charney DS, Keane TM, 1995. The development of a clinician-administered PTSD scale. Journal of traumatic stress 8, 75–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block SR, Liberzon I, 2016. Attentional processes in posttraumatic stress disorder and the associated changes in neural functioning. Experimental neurology 284, 153–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block SRR, Weissman DH, Sripada C, Angstadt M, Duval ER, King AP, Liberzon I, 2019. Neural Mechanisms of Spatial Attention Deficits in Trauma. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JD, Vermetten E, Vythilingam M, Afzal N, Schmahl C, Elzinga B, Charney DS, 2004. Neural correlates of the classic color and emotional stroop in women with abuse-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Biological psychiatry 55, 612–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodmann K, Gruber O, Goya-Maldonado R, 2017. Intranasal oxytocin selectively modulates large-scale brain networks in humans. Brain connectivity 7, 454–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbetta M, Patel G, Shulman GL, 2008. The reorienting system of the human brain: from environment to theory of mind. Neuron 58, 306–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbetta M, Shulman GL, 2002. Control of goal-directed and stimulus-driven attention in the brain. Nature reviews neuroscience 3, 201–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corporation, 2017. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, 25.0 ed. IBM Corp., Armonk, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Donadon MF, Martin-Santos R, Osório F.d.L., 2018. The associations between oxytocin and trauma in humans: a systematic review. Frontiers in pharmacology 9, 154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fani N, Jovanovic T, Ely TD, Bradley B, Gutman D, Tone EB, Ressler KJ, 2012. Neural correlates of attention bias to threat in post-traumatic stress disorder. Biological psychology 90, 134–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J, 1994. Structured clinical interview for Axis I DSM-IV disorders. New York: Biometrics Research. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher RA, 1915. Frequency distribution of the values of the correlation coefficient in samples from an indefinitely large population. Biometrika 10, 507–521. [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan JC, Hand A, Jarnecke AM, Maria M-S, Megan M, Brady KT, Joseph JE, 2018. Effects of oxytocin on working memory and executive control system connectivity in posttraumatic stress disorder. Experimental and clinical psychopharmacology 26, 391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan JC, Sippel LM, Santa Maria MMM, Hartwell KJ, Brady KT, Joseph JE, 2019. Impact of Oxytocin on the neural correlates of fearful face processing in PTSD related to childhood Trauma. European journal of psychotraumatology 10, 1606626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Cashman L, Jaycox L, Perry K, 1997. The validation of a self-report measure of posttraumatic stress disorder: the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale. Psychological assessment 9, 445. [Google Scholar]

- Fox MD, Corbetta M, Snyder AZ, Vincent JL, Raichle ME, 2006. Spontaneous neuronal activity distinguishes human dorsal and ventral attention systems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 103, 10046–10051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frijling JL, 2017. Preventing PTSD with oxytocin: effects of oxytocin administration on fear neurocircuitry and PTSD symptom development in recently trauma-exposed individuals. European journal of psychotraumatology 8, 1302652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein RB, Smith SM, Chou SP, Saha TD, Jung J, Zhang H, Pickering RP, Ruan WJ, Huang B, Grant BF, 2016. The epidemiology of DSM-5 posttraumatic stress disorder in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology 51, 1137–1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodnight JR, Ragsdale KA, Rauch SA, Rothbaum BO, 2019. Psychotherapy for PTSD: An evidence-based guide to a theranostic approach to treatment. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry 88, 418–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart H, Lim L, Mehta MA, Chatzieffraimidou A, Curtis C, Xu X, Breen G, Simmons A, Mirza K, Rubia K, 2017. Reduced functional connectivity of frontoparietal sustained attention networks in severe childhood abuse. PLoS one. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes JP, LaBar KS, Petty CM, McCarthy G, Morey RA, 2009. Alterations in the neural circuitry for emotion and attention associated with posttraumatic stress symptomatology. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging 172, 7–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennis M, Van Rooij S, Van Den Heuvel M, Kahn R, Geuze E, 2016. Functional network topology associated with posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans. NeuroImage: Clinical 10, 302–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Rose S, Koenen KC, Karam EG, Stang PE, Stein DJ, Heeringa SG, Hill ED, Liberzon I, McLaughlin KA, 2014. How well can post-traumatic stress disorder be predicted from pre-trauma risk factors? An exploratory study in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. World Psychiatry 13, 265–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch SB, van Zuiden M, Nawijn L, Frijling JL, Veltman DJ, Olff M, 2016. Intranasal oxytocin normalizes amygdala functional connectivity in posttraumatic stress disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 41, 2041–2051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim L, Hart H, Mehta MA, Simmons A, Mirza K, Rubia K, 2016. Neurofunctional abnormalities during sustained attention in severe childhood abuse. PloS one 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey RA, Petty CM, Cooper DA, LaBar KS, McCarthy G, 2008. Neural systems for executive and emotional processing are modulated by symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in Iraq War veterans. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging 162, 59–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen SE, Posner MI, 2012. The attention system of the human brain: 20 years after. Annual review of neuroscience 35, 73–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poppa T, Droutman V, Amaro H, Black D, Arnaudova I, Monterosso J, 2019. Sexual trauma history is associated with reduced orbitofrontal network strength in substance-dependent women. Neuroimage: clinical 24, 101973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power JD, Cohen AL, Nelson SM, Wig GS, Barnes KA, Church JA, Vogel AC, Laumann TO, Miezin FM, Schlaggar BL, 2011. Functional network organization of the human brain. Neuron 72, 665–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubia K, 2013. Functional brain imaging across development. European child & adolescent psychiatry 22, 719–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schäfer J, Strimmer K, 2005. A shrinkage approach to large-scale covariance matrix estimation and implications for functional genomics. Statistical applications in genetics and molecular biology 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeley WW, Menon V, Schatzberg AF, Keller J, Glover GH, Kenna H, Reiss AL, Greicius MD, 2007. Dissociable intrinsic connectivity networks for salience processing and executive control. Journal of Neuroscience 27, 2349–2356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw P, Kabani NJ, Lerch JP, Eckstrand K, Lenroot R, Gogtay N, Greenstein D, Clasen L, Evans A, Rapoport JL, 2008. Neurodevelopmental trajectories of the human cerebral cortex. Journal of neuroscience 28, 3586–3594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shehan D, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan K, Amorim P, Janvas J, Weiller E, Baker R, Dunbar G, 1998. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): the development and validation of a structered psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry 59, 22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sippel LM, Allington CE, Pietrzak RH, Harpaz-Rotem I, Mayes LC, Olff M, 2017. Oxytocin and stress-related disorders: neurobiological mechanisms and treatment opportunities. Chronic Stress 1, 2470547016687996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Woolrich MW, Beckmann CF, Behrens TEJ, Johansen-Berg H, Bannister PR, De Luca M, Drobnjak I, Flitney DE, Niazy RK, Saunders J, Vickers J, Zhang Y, De Stefano N, Brady JM, Matthews PM, 2004. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. NeuroImage 23, S208–S219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spengler FB, Schultz J, Scheele D, Essel M, Maier W, Heinrichs M, Hurlemann R, 2017. Kinetics and dose dependency of intranasal oxytocin effects on amygdala reactivity. Biological psychiatry 82, 885–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sripada RK, Rauch SA, Liberzon I, 2016. Psychological mechanisms of PTSD and its treatment. Current psychiatry reports 18, 99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stojek MM, McSweeney LB, Rauch SA, 2018. Neuroscience informed prolonged exposure practice: Increasing efficiency and efficacy through mechanisms. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience 12, 281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teicher MH, Samson JA, 2016. Annual research review: enduring neurobiological effects of childhood abuse and neglect. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry 57, 241–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teicher MH, Samson JA, Anderson CM, Ohashi K, 2016. The effects of childhood maltreatment on brain structure, function and connectivity. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 17, 652–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomaes K, 2013. Child abuse and recovery. Brain structure and function in child abuse related Complex posttraumatic stress disorder and effects of treatment. [Google Scholar]

- Yeo BTT, Krienen FM, Sepulcre J, Sabuncu MR, Lashkari D, Hollinshead M, Roffman JL, Smoller JW, Zöllei L, Polimeni JR, 2011. The organization of the human cerebral cortex estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. Journal of neurophysiology 106, 1125–1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vossel S, Geng JJ, Fink GR, 2014. Dorsal and ventral attention systems: distinct neural circuits but collaborative roles. The Neuroscientist 20, 150–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y, Jin C, Hu X, Duan L, Li Z, Song M, Chen H, Feng B, Jiang T, Jin H, 2011. Altered resting-state functional connectivity of thalamus in earthquake-induced posttraumatic stress disorder: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Brain research 1411, 98–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon S, Kim Y-K, 2019. Neuroendocrinological treatment targets for posttraumatic stress disorder. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry 90, 212–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu M, Linn KA, Shinohara RT, Oathes DJ, Cook PA, Duprat R, Moore TM, Oquendo MA, Phillips ML, Mclnnis M, 2019. Childhood trauma history is linked to abnormal brain connectivity in major depression. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116, 8582–8590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.