Abstract

Objective:

Female sex is a known risk factor in most cardiac surgery, including coronary and valve surgery, but unknown in acute type A aortic dissection repair.

Methods:

From 1996 to 2018, 650 patients underwent acute type A aortic dissection repair; 206 (32%) were female, and 444 (68%) were male. Data were collected through the Cardiac Surgery Data Warehouse, medical record review, and National Death Index database.

Results:

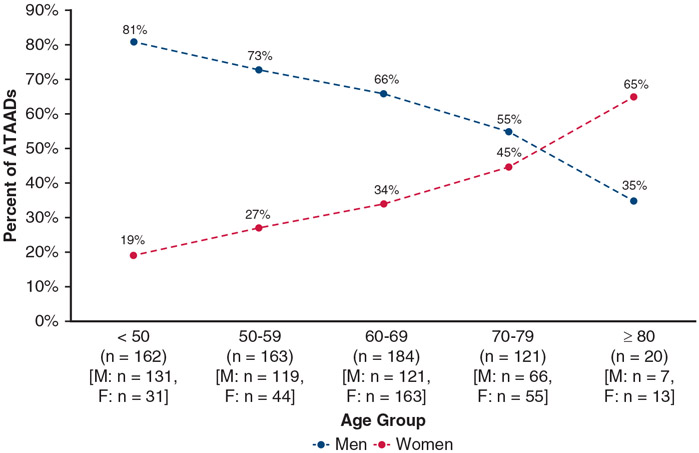

Compared with men, women were significantly older (65 vs 57 years, P < .0001). The proportion of women and men inverted with increasing age, with 23% of patients aged less than 50 years and 65% of patients aged more than 80 years being female. Women had significantly less chronic renal failure (2.0% vs 5.4%, P = .04), acute myocardial infarction (1.0% vs 3.8%, P = .04), and severe aortic insufficiency. Women underwent significantly fewer aortic root replacements with similar aortic arch procedures, shorter cardiopulmonary bypass times (211 vs 229 minutes, P = .0001), and aortic crossclamp times (132 vs 164 minutes, P < .0001), but required more intraoperative blood transfusion (4 vs 3 units) compared with men. Women had significantly lower operative mortality (4.9% vs 9.5%, P = .04), especially in those aged more than 70 years (4.4% vs 16%, P = .02). The significant risk factors for operative mortality were male sex (odds ratio, 2.2), chronic renal failure (odds ratio, 3.4), and cardiogenic shock (odds ratio, 6.8). The 10-year survival was similar between sexes.

Conclusions:

Physicians and women should be cognizant of the risk of acute type A aortic dissection later in life in women. Surgeons should strongly consider operations for acute type A aortic dissection in women, especially in patients aged 70 years or more.

Keywords: acute type A aortic dissection, aorta, outcomes, sex

Operative mortality of ATAAD repair was lower in women than men among all age groups.

Sex-related differences in cardiac surgery have been recognized, particularly in coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG)1-3 and mitral valve surgery,4-6 for which female sex is an independent risk factor for mortality. Chung and colleagues7 reported that women undergoing thoracic aortic surgery had significantly higher mortality and stroke compared with men, with female sex being an independent predictor of mortality (odds ratio [OR], 1.8), with rates of acute aortic dissection similar between men and women.

In contrast to a majority of CABG and mitral valve procedures, operations for an acute type A aortic dissection (ATAAD) are performed on an emergency basis. There are 2000 new ATAAD cases per year in the United States,8 and despite new advances in technology and management, operative mortality remains high (8%-26%).9-11 ATAAD most commonly presents in the sixth through eighth decades of life12 and predominantly affects men.8,13 As with other cardiac operations, Nienaber and colleagues8 found that women have a higher mortality when undergoing ATAAD repair compared with men using the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection. However, other studies have found similar mortalities between men and women undergoing ATAAD repair.14-16

This study aims to determine sex-related differences in preoperative characteristics, surgical techniques, and postoperative outcomes, particularly operative mortality, in patients undergoing ATAAD repair.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Michigan, Michigan Medicine (Ann Arbor, Mich) (HUM00052866), a waiver of consent was obtained, and the study was in compliance with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act regulations.

Study Population

Between August 1996 and December 2018, 650 patients underwent open repair of an ATAAD, of whom 32% (n = 206) were female and 68% (n = 444) were male. Investigators leveraged the Society of Thoracic Surgeons data elements from the University of Michigan Cardiac Surgery Data Warehouse to identify the cohort and determine preoperative, operative, and postoperative characteristics. Electronic medical records were reviewed to supplement data collection. History of stroke was defined as in the Society of Thoracic Surgeon’s database: a patient having an acute episode of focal or global neurologic dysfunction caused by brain, spinal cord, or retinal vascular injury as a result of hemorrhage or infarction, and the neurologic dysfunction lasts more than 24 hours before current hospitalization. Chronic renal failure was defined as chronic renal dysfunction, based on creatinine and glomerular filtration rate with or without dialysis, before aortic dissection. Preoperative acute renal failure was defined as acute renal dysfunction, increasing or elevated from baseline creatinine, since aortic dissection. Postoperative acute renal failure was defined as a patient who had new-onset acute renal failure or worsening renal function after ATAAD repair resulting in (1) an increase in serum creatinine level 3 times greater than baseline or serum creatinine level 4 mg/dL or greater, and the acute increase must be at least 0.5 mg/dL; or (2) a new requirement for dialysis postoperatively. Investigators used the National Death Index database through December 31, 2018,17 medical record review, and phone call survey (including letters and phone calls, January 2018) to obtain long-term survival. Loss of follow-up was treated as censors during the time-to-event analysis. Long-term follow-up was 100% complete until December 31, 2018, and 77% complete after that. The primary outcome was operative mortality.

Surgical Techniques

The operative strategy in patients with ATAAD has been described.9,18-21 Briefly, the indication for aortic root replacement in patients with ATAAD included (1) intimal tear at the aortic root; (2) root diameter 4.5 cm or more; (3) connective tissue disease; and (4) unrepairable aortic valve pathology.9,18 The root procedures include direct repair9 or replacement as inclusion root, Bentall procedure, or David procedure.9,18,22 Indications for zone 1 to 3 arch replacement included an arch aneurysm greater than 4 cm or intimal tear located in the arch when the arch aneurysm or intimal tear could not be resected by a hemiarch replacement or dissection of arch branch vessels with upper-extremity or cerebral malperfusion syndrome.19 In zone 1 arch replacement, the arch is divided between the innominate and left common carotid arteries with reimplantation of the innominate artery to its bifurcation; in zone 2 arch replacement, the arch is divided between the left common carotid and left subclavian arteries with reimplantation of the innominate and left common carotid arteries; and in zone 3 arch replacement (total arch replacement), the arch is divided distal to the left subclavian artery with reimplantation of all arch branch vessels. All arch branch vessels were reimplanted/replaced individually to branch grafts. If needed, a frozen elephant trunk (cTAG 10 cm, WL Gore and Associates Inc, Flagstaff, Ariz) was placed into the true lumen of the descending thoracic aorta distal to the left subclavian artery as we described.19 Malperfusion syndrome, tissue/organ necrosis, and dysfunction due to inadequate blood flow amenable to endovascular reperfusion (visceral and extremities, and without evidence of aortic rupture or cardiac tamponade) were managed with initial endovascular fenestration/stenting and delayed open aortic repair.23 In those with malperfusion syndrome, initial endovascular fenestration/stenting was performed to treat the malperfused vascular territories first; then patients were allowed to recover from the malperfusion syndrome in the intensive care unit and subsequently underwent open aortic repair of the ATAAD after recovery.23

Statistical Analysis

Initial analysis provided descriptive information on the demographic, clinical, and surgical characteristics. Continuous variables were summarized by median (25%, 75%) and categorical variables were reported as n (%) in frequency tables. Univariate comparisons between male and female groups were performed using chi-square tests or Fisher exact tests for categorical data and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for continuous data. Multivariable logistic regression was used to assess risk factors for operative mortality by adjusting sex, age, cardiogenic shock, preoperative chronic renal failure, acute myocardial infarction, and acute paralysis. Crude survival curves since operation were estimated using the nonparametric Kaplan–Meier method. Log-rank test was used to compare the survival between groups. Cox proportional hazard regression was performed to calculate the hazard ratio (HR) for long-term mortality for all patients from date of operation by adjusting sex, age, categorical ejection fraction, creatinine, and acute paralysis using cardiogenic shock as strata due to violation of proportional hazard assumption. The variables for the logistic and Cox models were chosen on the basis of univariate analysis and clinical judgment. Collinearity and proportional hazards were checked. Neither year of surgery nor surgeon was a significant risk factor for operative mortality and did not alter the sex effect. All statistical calculations were performing using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Demographics and Preoperative Data

The median age of the entire cohort was 60 years, and the women were significantly older than the men (65 vs 57 years, P < .0001). The proportion of women and men presenting with ATAAD flips with increasing age, with only 23% of patients aged less than 50 years being female and 65% of patients aged more than 80 years being female (Figure 1). The women had lower body mass index (27.7 vs 28.3 kg/m2), although this was not statistically significant (P = .053). The women also had more hypertension (79% vs 71%, P = .03) and history of stroke (7.3% vs 2.0%, P = .0009) but less chronic renal failure (2.0% vs 5.4%, P = .04), previous cardiac surgery (4.9% vs 10%, P = .02), acute myocardial infarction (1.0% vs 3.8%, P = .04), and severe aortic insufficiency (16% vs 27%, overall P = .04). Women had less extensive dissections, with less DeBakey I dissections than men (84% vs 93%, P = .0009). Women had less malperfusion syndrome (20% vs 26%, P = .11) and underwent less delayed aortic repair (delayed for initial treatment of malperfusion syndrome with endovascular fenestration/stenting) (11% vs 17%, P = .04) (Table 1). Overall, connective tissue disorders (CTDs) were similar between women and men (5.8% vs 4.1%, P = .32), and the incidence of CTD decreased with age in both men and women. Among patients aged less than 50 years, 15% had CTD; among patients aged 50 to 59 years, 1.8% had CTD; among patients aged 60 to 69 years, 0.5% had CTD; and among patients aged more than 69 years, 0% had CTD.

FIGURE 1.

The proportion of women and men in different age groups undergoing ATAAD repair. With increasing age, the proportion of women increases, whereas that of men decreases among ATAAD cases. ATAAD, Acute type A aortic dissection.

TABLE 1.

Demographics and preoperative comorbidities

| Variables | Total (n = 650) | Men (n = 444) | Women (n = 206) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient age (y) | 60 (50, 68) | 57 (48, 65) | 65 (54, 74) | <.0001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.0 (24.8, 32) | 28.2 (25.3, 32.1) | 27.7 (23.8, 31.9) | .053 |

| Preexisting comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension | 476 (73) | 314 (71) | 162 (79) | .03 |

| Diabetes | 43 (6.6) | 26 (5.9) | 17 (8.3) | .25 |

| Smoking status | .17 | |||

| Never | 271 (42) | 177 (40) | 94 (46) | |

| Former | 179 (28) | 121 (27) | 58 (28) | |

| Current | 196 (30) | 144 (33) | 52 (25) | |

| CAD | 120 (19) | 86 (20) | 34 (17) | .42 |

| COPD | 68 (10) | 41 (9.2) | 27 (13) | .13 |

| History of MI | 33 (5.1) | 22 (5.0) | 11 (5.3) | .84 |

| *Chronic renal failure | 28 (4.3) | 24 (5.4) | 4 (2.0) | .04 |

| †History of stroke | 24 (3.7) | 9 (2.0) | 15 (7.3) | .0009 |

| PVD | 102 (16) | 28 (14) | 74 (17) | .32 |

| CTD | 30 (4.6) | 18 (4.1) | 12 (5.8) | .32 |

| Bicuspid aortic valve | 59 (10) | 46 (12) | 13 (7.3) | .10 |

| Previous cardiac intervention | 107 (16) | 74 (17) | 33 (16) | .84 |

| Previous cardiac surgery | 56 (8.6) | 46 (10) | 10 (4.9) | .02 |

| Preoperative AI | .04 | |||

| None | 175 (28) | 115 (27) | 60 (31) | |

| Trace | 66 (11) | 43 (10) | 23 (12) | |

| Mild | 126 (20) | 79 (19) | 47 (24) | |

| Moderate | 105 (17) | 71 (17) | 34 (17) | |

| Severe | 148 (24) | 116 (27) | 32 (16) | |

| Ejection fraction | 55 (51, 60) | 55 (50, 60) | 55 (55, 65) | .0008 |

| Acute stroke | 35 (5.4) | 23 (5.2) | 12 (5.8) | .73 |

| Acute MI | 19 (2.9) | 17 (3.8) | 2 (1.0) | .04 |

| ‡Acute renal failure | 76 (12) | 57 (13) | 19 (9.2) | .18 |

| Acute paralysis | 13 (2.0) | 10 (2.3) | 3 (1.5) | .76 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 56 (8.6) | 38 (8.6) | 18 (8.7) | .94 |

| Preoperative creatinine | 1.0 (0.8, 1.3) | 1.1 (0.9, 1.4) | 0.9 (0.7, 1.1) | <.0001 |

| Malperfusion syndrome | 158 (24) | 116 (26) | 42 (20) | .11 |

| Coronary | 20 (3.1) | 17 (3.8) | 3 (1.5) | .10 |

| Cerebral | 36 (5.5) | 23 (5.2) | 13 (6.3) | .30 |

| Spinal cord | 11 (1.7) | 6 (1.4) | 5 (2.4) | .34 |

| Celiac/hepatic | 10 (1.5) | 9 (2.0) | 1 (0.5) | .14 |

| Mesenteric | 58 (8.9) | 45 (10) | 13 (6.3) | .11 |

| Renal | 50 (7.7) | 35 (7.9) | 15 (7.3) | .79 |

| Lower extremity | 56 (8.6) | 41 (9.2) | 15 (7.3) | .54 |

| Delayed operation | 97 (15) | 75 (17) | 22 (11) | .04 |

| DeBakey Class | .0009 | |||

| I | 586 (90) | 412 (93) | 174 (84) | |

| II | 64 (10) | 32 (7.2) | 32 (16) | |

| Distal extent | .0006 | |||

| Ascending | 64 (9.8) | 32 (7.2) | 32 (16) | .0009 |

| Arch | 94 (14) | 64 (14) | 30 (15) | .96 |

| Descending | 78 (12) | 50 (11) | 28 (14) | .39 |

| Abdominal | 145 (22) | 93 (21) | 52 (25) | .22 |

| Suprarenal | 57 (8.8) | 31 (7.0) | 26 (13) | .049 |

| Infrarenal | 88 (14) | 62 (14) | 26 (13) | .049 |

| Iliac | 269 (41) | 205 (46) | 64 (31) | .0003 |

Data presented as median (25%, 75%) for continuous data and n (%) for categorical data. P value indicates the difference between the men and women. BMI, Body mass index; CAD, coronary artery disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; MI, myocardial infarction; PVD, peripheral vascular disease; CTD, connective tissue disorder; AI, aortic insufficiency.

Chronic renal failure = chronic renal dysfunction, based on creatinine and glomerular filtration rate with or without dialysis, before aortic dissection.

History of stroke = acute episode of focal or global neurologic dysfunction caused by brain, spinal cord, or retinal vascular injury as a result of hemorrhage or infarction, where the neurologic dysfunction lasts for more than 24 h before current hospitalization.

Acute renal failure = acute renal dysfunction, increasing or elevated from baseline creatinine, since aortic dissection.

Operative Data

Women underwent less aortic root replacement and more aortic root repair, but similar extents of arch replacement and similar amounts of concomitant procedures including CABG, mitral valve, and tricuspid valve operations. Women had shorter cardiopulmonary (211 vs 229 minutes, P = .0001) and aortic crossclamp (132 vs 164 minutes, P < .0001) times. Both groups had similar amount of hypothermic circulatory arrest use, with circulatory arrest times being shorter in women (33 vs 36 minutes, P = .03). Women required more intraoperative transfusion of packed red blood cells than men (4 vs 3 units, P = .0075) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Intraoperative data

| Variables | Total (n = 650) | Men (n = 444) | Women (n = 206) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aortic root procedure | .0006 | |||

| None | 54 (8.3) | 38 (8.6) | 16 (7.8) | |

| AVR only | 14 (2.2) | 9 (2.0) | 5 (2.4) | |

| Root replacement | 219 (34) | 172 (39) | 47 (23) | |

| Root repair | 363 (56) | 225 (51) | 138 (67) | |

| Aortic arch replacement | .95 | |||

| None | 36 (5.5) | 24 (5.4) | 12 (5.8) | |

| Hemiarch | 387 (60) | 262 (59) | 125 (61) | |

| Zone 1 | 54 (8.3) | 39 (8.8) | 15 (7.3) | |

| Zone 2 | 124 (19) | 84 (19) | 40 (19) | |

| Zone 3 | 49 (7.5) | 35 (7.9) | 14 (6.8) | |

| Frozen elephant trunk | 67 (10) | 48 (11) | 19 (9.2) | .54 |

| Concomitant procedures | ||||

| CABG | 40 (6.2) | 29 (6.5) | 11 (5.3) | .56 |

| Mitral valve | 5 (0.8) | 4 (0.9) | 1 (0.5) | .57 |

| Tricuspid valve | 8 (1.2) | 5 (2.4) | 3 (0.7) | .12 |

| CPB time (min) | 222 (181, 272) | 229 (189, 279) | 211 (170, 258) | .0001 |

| Crossclamp time (min) | 155 (116, 202) | 164 (123, 213) | 132 (106, 183) | <.0001 |

| HCA | 616 (95) | 421 (95) | 195 (95) | .93 |

| HCA time (min) | 34 (26, 45) | 36 (27, 46) | 33 (24, 44) | .03 |

| Cerebral perfusion | .16 | |||

| None | 37 (5.7) | 25 (5.6) | 12 (5.9) | |

| Antegrade | 252 (39) | 160 (36) | 92 (45) | |

| Retrograde | 213 (33) | 151 (34) | 62 (30) | |

| Both antegrade and retrograde | 147 (23) | 108 (24) | 39 (19) | |

| Lowest temperature (°C) | 18 (17, 22) | 18 (17, 22.1) | 18.2 (17.9, 21.3) | .22 |

| Blood transfusion (PRBCs), units | 4 (1, 7) | 3 (0, 7) | 4 (2, 7) | .0075 |

Data presented as median (25%, 75%) for continuous data and n (%) for categorical data. P value indicates the difference between the men and women. AVR, Aortic valve replacement; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; HCA, hypothermic circulatory arrest; PRBC, packed red blood cells.

Postoperative Outcomes

Overall, there were no significant differences in major postoperative outcomes, except operative mortality, between women and men, including postoperative stroke, myocardial infarction, and new-onset renal failure on dialysis. Women had longer postoperative lengths of stay (11.5 vs 10 days, P = .03) but lower operative mortality (4.9% vs 9.5%, P = .04), including mortality during the hospital stay or within 30 days of ATAAD repair (Table 3). Although likely not achieving statistical significance because of low sample size, operative mortality was lower in women among all age groups. The difference was more pronounced with advanced age, with a significant mortality difference among patients aged more than 70 years (4.4% vs 16%, P = .02) (Figure 2). The significant risk factors for operative mortality were male sex (OR, 2.18, 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.02-4.68, P = .04), preoperative chronic renal failure (OR, 3.44, 95% CI, 1.17-10.12, P = .02), and cardiogenic shock (OR, 6.76, 95% CI, 3.35-13.6, P < .0001) (Table 4).

TABLE 3.

Postoperative outcomes

| Variables | Total (n = 650) | Men (n = 444) | Women (n = 206) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reoperation for bleeding | 52 (8.0) | 35 (7.9) | 17 (8.3) | .87 |

| Tamponade | 11 (1.7) | 10 (2.3) | 1 (0.5) | .19 |

| Deep sternal wound infection | 13 (2.0) | 11 (2.5) | 2 (1.0) | .24 |

| Sepsis | 17 (2.6) | 13 (2.9) | 4 (1.9) | .46 |

| Postoperative MI | 6 (0.9) | 3 (0.7) | 3 (1.5) | .39 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 224 (34) | 156 (35) | 68 (33) | .60 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 46 (7.1) | 30 (6.8) | 16 (7.8) | .64 |

| New-onset paraplegia | 3 (0.5) | 3 (0.7) | 0 (0) | .56 |

| New-onset acute renal failure* | 66 (10) | 49 (11) | 17 (8.3) | .27 |

| Requiring dialysis | 30 (4.6) | 23 (5.2) | 7 (3.4) | .31 |

| Gastrointestinal complications | 57 (8.8) | 41 (9.2) | 16 (7.8) | .54 |

| Pneumonia | 109 (17) | 81 (18) | 28 (14) | .14 |

| Prolonged ventilation (>24 h) | 346 (53) | 229 (52) | 117 (57) | .21 |

| Hours intubated | 41 (22, 95) | 40 (21, 95) | 43 (24, 93) | .30 |

| Reintubation | 44 (6.8) | 28 (6.3) | 16 (7.8) | .48 |

| Tracheostomy | 20 (3.1) | 10 (2.3) | 10 (4.9) | .07 |

| Postoperative LOS (d) | 10 (7, 17) | 10 (7, 16) | 11.5 (7, 19) | .03 |

| Total LOS (d) | 12 (7, 19) | 11 (7, 18.5) | 12 (8, 21) | .09 |

| Intraoperative mortality | 7 (1.1) | 5 (1.1) | 2 (1.0) | 1.0 |

| In-hospital mortality† | 49 (7.5) | 39 (8.8) | 10 (4.9) | .08 |

| 30-d mortality‡ | 40 (6.2) | 32 (7.2) | 8 (3.9) | .10 |

| Operative mortality§ | 52 (8.0) | 42 (9.5) | 10 (4.9) | .04 |

Data presented as median (25%, 75%) for continuous data and n (%) for categorical data. P value indicates the difference between men and women. MI, Myocardial infarction; LOS, length of stay.

New-onset acute renal failure = new-onset acute renal failure or worsening renal function after ATAAD repair resulting in (1) an increase in serum creatinine level 3 times greater than baseline or serum creatinine level 4 mg/dL or greater, and the acute increase must be at least 0.5 mg/dL or (2) a new requirement for dialysis postoperatively.

In-hospital mortality = death within hospitalization during which the operation occurred.

Thirty-day mortality = death within 30 d of the operation.

Operative mortality includes 30-d mortality or in-hospital mortality.

FIGURE 2.

Operative mortality in women and men in different age groups undergoing ATAAD repair. Operative mortality remains disparate between women and men with women having lower operative mortality among all age groups: less than 50 years, 3.2% versus 6.1%, P = .10; 50 to 59 years, 4.5% versus 8.4%, P = .52; 60 to 69 years, 6.4% versus 9.9%, P = .41; 70 to 79 years, 5.5% versus 17%, P = .055; and 80 years or more, 0% versus 14%, P = .35. Operative mortality was significantly lower in women than in men among patients aged more than 70 years (4.4% vs 16%, P = .02).

TABLE 4.

Risk factors for operative and long-term mortality

| Operative mortality | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Female sex | 0.46 (0.21-0.98) | .04 |

| Age | 1.02 (1.00-1.05) | .06 |

| Preoperative chronic renal failure | 3.44 (1.17-10.12) | .02 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 2.88 (0.88-9.47) | .08 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 6.76 (3.35-13.6) | <.0001 |

| Acute paralysis | 3.78 (0.88-16.2) | .07 |

| Long-term mortality | HR (95% CI) | P value |

| Female sex | 0.99 (0.72-1.36) | .95 |

| Age | 1.04 (1.03-1.05) | <.0001 |

| Ejection fraction <40% (vs ≥60%) | 2.34 (1.29-4.23) | .005 |

| Ejection fraction 40%-50% (vs | 2.61 (1.56-4.37) | .0003 |

| ≥60%) | ||

| Ejection fraction 50%-60% (vs | 1.12 (0.77-1.63) | .55 |

| ≥60%) | ||

| Ejection fraction unknown (vs | 1.26 (0.81-1.95) | .31 |

| ≥60%) | ||

| Creatinine | 1.22 (1.11-1.35) | <.0001 |

| Acute paralysis | 2.39 (0.96-5.91) | .06 |

CI, Confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

Long-term Survival

The mean follow-up time was 5.6 ± 5 years. The 10-year survival was similar between women (49%, 95% CI, 30-66) and men (60%, 95% CI, 50-68; P = .29) (Figure 3). The significant risk factors for long-term mortality after operation were age (HR, 1.04, 95% CI, 1.03-1.05, P < .001), ejection fraction less than 40% (HR, 2.34, 95% CI, 1.29-4.23, P = .005), ejection fraction 40% to 50% (HR, 2.61, 95% CI, 1.56-4.37, P = .0003), and preoperative creatinine (HR, 1.22, 95% CI, 1.11-1.35, P < .0001) (Table 4). Sex was not a significant risk factor for long-term mortality (male: HR, 1.01, 95% CI, 0.74-1.38, P = .95).

FIGURE 3.

A, Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of patients undergoing open ATAAD repair. The overall 10-year survival of the entire cohort was 57% and statistically similar between women (49%, 9 5% CI, 30-66) and men (60%, 9 5% CI, 50-68).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we compared the perioperative outcomes and long-term survival of women and men undergoing open aortic repair for an ATAAD and found that women had significantly lower operative mortality compared with men and that male sex was an independent risk factor for operative mortality, whereas women and men had similar long-term survival. This study also underscores many important differences between women and men undergoing ATAAD repair, specifically that women tend to be older at time of ATAAD, to have less DeBakey type I dissection, and to undergo less aortic root replacement with shorter operations overall; however, they require more intraoperative transfusion of packed red blood cells.

ATAAD more commonly affects men, with approximately two-thirds of ATAADs occurring in men,8,24,25 as in our study. However, with increasing age this relationship switches with aortic dissection occurring in women at older ages (Figure 1). In both men and women, aging is associated with arterial dilation and vessel wall thickening and stiffening, particularly of the intima with an increase in collagen types I and III and a decrease in elastin.26 In the media, vascular smooth muscles cells decrease and collagen production increases with collagen with an increase in collagen also seen in the adventitia 26; however, differences between men and women exist. One potential mechanism for aortic dissection in women at older ages is the hormonal effect, particularly the protective effect of estrogen on arteries, including the aorta. Arterial stiffness has been found to be lower in premenopausal women compared with age-matched men; however, after menopause arterial stiffness markedly increases in women compared with men.26-28 A recent study by Samargandy and colleagues29 showed that within 1 year of a woman’s final menstrual period there is an acceleration in arterial stiffening. The median age of menopause is 51 years; in our study, 83% of women presented with an ATAAD at or after the age of 51 years with the median time since menopause being 16 years (interquartile range, 9-23). In addition, these vascular changes can be evidenced by elevation of blood pressure in older individuals, with hypertension being a known risk factor for aortic dissection. In our study, in addition to being older at time of dissection, women also had more hypertension (79% vs 71%). Our findings indicate that women are more vulnerable to acute aortic dissection at older ages than men, which could be due to hormonal effects on arteries; women should be cognizant of ATAAD later in life.

Patients with CTDs such as Marfan and Loeys–Dietz syndromes often present with ATAAD at a younger age due to aortopathy. In our previous study of whole exome sequencing of patients with an aortic dissection, age less than 50 years was a significant risk factor for a pathogenic variant in known causative genes for aortopathy.30 However, genetic aortopathy affects women and men similarly, in agreement with the autosomal dominant inheritance of these CTDs such as Marfan syndrome, as can be seen in this study (women, 5.8% vs men, 4.1%, P = .32). In this study, all patients with a CTD were aged less than 60 years, with a median age of 34.5 years and the incidence of CTD decreased with age. Among patients aged less than 50 years (n = 162), men comprised the majority (81%, n = 131), but CTD was present in only 12% of those patients. In contrast, women comprised the minority of patients aged less than 50 years (19%, n = 31), but CTD was present in 29% of those patients. Among patients aged less than 50 years (n = 162), the presence of CTD was significantly greater in women (29% vs 12%, P = .02). Therefore, although young patients presenting with ATAAD should raise suspicion for a genetic component, a hereditary component should be especially considered in young women presenting with ATAAD.

In the setting of this surgical emergency, the primary goal is to have a live patient leaving the operating room by preventing/treating aortic rupture, resolving end-organ malperfusion, and treating acute heart failure due to acute aortic insufficiency; however, operations vary depending on clinical characteristics, such as extent of dissection. Rylski and colleagues16 showed that men and women have similar involvement of the aortic arch and arch branch vessels, but men have greater extent of dissection into the descending thoracic and abdominal aorta, and men had more spinal, visceral, and renal malperfusion likely as a result. In our study, men had more extensive dissections than women (DeBakey I: 93% vs 84%, P = .0009) (Table 1) and more malperfusion syndrome (26% vs 20%), tissue/organ necrosis, and dysfunction due to inadequate blood flow,23 although not statistically significant (P = .11), with malperfusion syndrome being a predictor for early mortality among all-comers with ATAAD.11,23,31 Women and men have similar involvement of aortic arch branch vessels,8,16 which can be evidenced by similar extents of aortic arch repair,16 which coincides with our study. However, men undergo more aortic root replacement9,15,16 as in our study (39% vs 23%), in which the indications for aortic root replacement were intimal tear at the aortic root, root diameter 4.5 cm or greater, CTD, and unrepairable aortic valve pathology, suggesting that men may have more extensive aortic root pathology. Despite more aggressive root replacement not being an independent risk factor for hospital mortality,24 it does add time to the operation yielding longer cardiopulmonary bypass and aortic crossclamp times, as shown in this study (cardiopulmonary bypass time: 229 vs 211 minutes and aortic crossclamp: 164 vs 132 minutes) in addition to longer hypothermic circulatory arrest times (36 vs 33 minutes). Long cardiopulmonary bypass times and aortic crossclamp times have been associated with increased morbidity and mortality.32-35 Suzuki and colleagues14 found that longer cardiopulmonary bypass time was an independent risk factor for early mortality in patients undergoing ATAAD repair. Women had better ejection fraction, lower creatinine, less chronic renal failure, and less severe aortic insufficiency than men at presentation of ATAAD (Table 1). The better operative mortality in women could be due to better organ function at presentation, less extensive aortic root operation, and less systemic changes from long bypass and crossclamp times. Women had a higher rate of intraoperative blood transfusion, which could be due to older age and lower body mass index among women, predictors for blood transfusion 36; however, female sex was an independent protective factor against operative mortality (Table 4) for the reasons discussed earlier.

Operative mortality was significantly lower in women than men (4.9% vs 9.5%, P = .04), in contrast to other studies from single14,15 and multi-institutions,25 the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection,8 and the German Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection Type A16 in which mortality was similar between women and men. Nienaber and colleagues8 found that despite mortalities being similar overall, women had a higher in-hospital mortality among patients aged 66 to 75 years.8 One limitation of using a registry to study operative outcomes is that there are often many missing data and large variations in operative outcomes among the institutions, such as the study using the German Registry in which 23% of data were missing for 30-day mortality. In our study, we had accurate data of the operative outcomes for every single patient, including operative mortality. The operative mortality was lower in women among all age groups (Figure 2). The difference of operative mortality was significant between women and men among all patients (4.9% vs 9.5%, P = .04) and in the group aged more than 70 years (4.4% vs 16%, P = .02).

Although the median age was 8 years older at the presentation of ATAAD in women, women had similar long-term survival as men (Figure 3). Sex was not a risk factor for long-term mortality with an HR of male being 1.01 (Table 4). With better operative mortality and similar long-term survival, surgeons should strongly consider open aortic repair of ATAAD in women, probably more aggressive in women than men when patients are older than 70 years (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Among all patients undergoing open ATAAD repair, women were older but had lower operative mortality than men. OR, Odds ratio; ATAAD, acute type A aortic dissection.

Study Limitations

This study is limited as a single-center and retrospective experience. At our institution, primarily only aortic surgeons operate on ATAAD and malperfusion syndrome is managed endovascularly before open aortic repair. This also could be a reason for different operative mortality between our study and other studies. Our experience may not apply to all hospitals operating on ATAADs. In addition, this study did not factor in patients dying before hospital presentation with an ATAAD, in which differences in time to seeking medical care may exist between men and women. In addition, the study spans over a 22-year time period, during which practices and techniques evolve, but our strategy of managing malperfusion syndrome remained the same, and surgical era and surgeon had minimal impact on the logistic model for operative mortality.

CONCLUSIONS

Physicians and women need to be cognizant of the potential of ATAAD later in life, particularly after menopause. Women who present with aortic dissection at a young age should raise suspicion for hereditary thoracic aortic disease. Women had significantly better operative mortality compared with men, specifically women aged more than 70 years. Therefore, women, particularly older women, should be given the opportunity with open aortic repair for ATAAD despite an elderly age (Video 1).

Supplementary Material

VIDEO 1. Discussion of the impact of sex on ATAAD presentation and outcomes after open repair. Video available at: https://www.jtcvs.org/article/S0022-5223(21)00559-6/fulltext.

CENTRAL MESSAGE.

Women were older at the time of ATAAD but had lower operative mortality than men, with male sex being an independent risk factor for operative mortality. Long-term survival was similar between sexes.

PERSPECTIVE.

Physicians should be cognizant of the potential of ATAADs later in life, especially in women. Women present at older ages but have lower operative mortality than men; therefore, older women should be given the opportunity for open aortic repair at the time of ATAAD. Sex could be considered in the decision process for ATAAD management.

Acknowledgments

B.Y. is supported by National Institutes of Health K08HL130614, R01HL141891, R01HL151776, Phil Jenkins and Darlene & Stephen J. Szatmari Funds.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- ATAAD

acute type A aortic dissection

- CABG

coronary artery bypass grafting

- CI

confidence interval

- CTD

connective tissue disorder

- HR

hazard ratio

- OR

odds ratio

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

The Journal policy requires editors and reviewers to disclose conflicts of interest and to decline handling or reviewing manuscripts for which they may have a conflict of interest. The editors and reviewers of this article have no conflicts of interest.

Read at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions, November 16-19, 2019, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Date and number of Institutional Review Board approval: 9/27/2016, HUM00119716.

References

- 1.Swaminathan RV, Feldman DN, Pashun RA, Patil RK, Shah T, Geleris JD, et al. Gender differences in in-hospital outcomes after coronary artery bypass grafting. Am J Cardiol. 2016;118:362–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bukkapatnam RN, Yeo KK, Li Z, Amsterdam EA. Operative mortality in women and men undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (from the California Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting Outcomes Reporting Program). Am J Cardiol. 2010; 105:339–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takagi H, Manabe H, Umemoto T. A contemporary meta-analysis of gender differences in mortality after coronary artery bypass grafting. Am J Cardiol. 2010; 106:1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vassileva CM, McNeely C, Mishkel G, Boley T, Markwell S, Hazelrigg S. Gender differences in long-term survival of Medicare beneficiaries undergoing mitral valve operations. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96:1367–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vassileva CM, Stelle LM, Markwell S, Boley T, Hazelrigg S. Sex differences in procedure selection and outcomes of patients undergoing mitral valve surgery. Heart Surg Forum. 2011;14:E276–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song HK, Grab JD, O’Brien SM, Welke KF, Edwards F, Ungerleider RM. Gender differences in mortality after mitral valve operation: evidence for higher mortality in perimenopausal women. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85:2040–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung J, Stevens LM, Ouzounian M, El-Hamamsy I, Bouhout I, Dagenais F, et al. Sex-related differences in patients undergoing thoracic aortic surgery. Circulation. 2019;139:1177–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nienaber CA, Fattori R, Mehta RH, Richartz BM, Evangelista A, Petzsch M, et al. Gender-related differences in acute aortic dissection. Circulation. 2004; 109:3014–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang B, Norton EL, Hobbs R, Farhat L, Wu X, Hornsby WE, et al. Short- and long-term outcomes of aortic root repair and replacement in patients undergoing acute type a aortic dissection repair: 20-year experience. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;157:2125–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cabasa A, Pochettino A. Surgical management and outcomes of type A dissection-the Mayo Clinic experience. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2016;5: 296–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berretta P, Patel HJ, Gleason TG, Sundt TM, Myrmel T, Desai N, et al. IRAD experience on surgical type A acute dissection patients: results and predictors of mortality. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2016;5:346–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trimarchi S, Eagle KA, Nienaber CA, Rampoldi V, Jonker FH, De Vincentiis C, et al. Role of age in acute type A aortic dissection outcome: report from the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD). J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;140:784–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee TC, Kon Z, Cheema FH, Grau-Sepulveda MV, Englum B, Kim S, et al. Contemporary management and outcomes of acute type A aortic dissection: an analysis of the STS adult cardiac surgery database. J Card Surg. 2018;33: 7–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suzuki T, Asai T, Kinoshita T. Clinical differences between men and women undergoing surgery for acute Type A aortic dissection. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2018;26:944–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fukui T, Tabata M, Morita S, Takanashi S. Gender differences in patients undergoing surgery for acute type A aortic dissection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015; 150:581–7.e581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rylski B, Georgieva N, Beyersdorf F, Busch C, Boening A, Haunschild J, et al. Gender-related differences in patients with acute aortic dissection type A. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019. [In press]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National death index. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ndi/index.htm. Accessed December 31, 2018.

- 18.Yang B, Malik A, Waidley V, Kleeman KC, Wu X, Norton EL, et al. Short-term outcomes of a simple and effective approach to aortic root and arch repair in acute type A aortic dissection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018;155: 1360–70.e1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang B, Norton EL, Shih T, Farhat L, Wu X, Hornsby WE, et al. Late outcomes of strategic arch resection in acute type A aortic dissection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;157:1313–21.e1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norton EL, Wu X, Farhat L, Kim KM, Patel HJ, Deeb GM, et al. Dissection of arch branches alone an indication for aggressive arch management in type A dissection? Ann Thorac Surg. 2019;109:487–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Norton EL, Rosati CM, Kim KM, Wu X, Patel HJ, Deeb GM, et al. Is previous cardiac surgery a risk factor for open repair of acute type A aortic dissection? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;160:8–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang B, Patel HJ, Sorek C, Hornsby WE, Wu X, Ward S,et al. Sixteen-year experience of David and Bentall procedures in acute type A aortic dissection. Ann Thorac Surg. 2018;105:779–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang B, Rosati CM, Norton EL, Kim KM, Khaja MS, Dasika N, et al. Endovascular fenestration/stenting first followed by delayed open aortic repair for acute type A aortic dissection with malperfusion syndrome. Circulation. 2018;138: 2091–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Evangelista A, Isselbacher EM, Bossone E, Gleason TG, Eusanio MD, Sechtem U, et al. Insights from the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection: a 20-year experience of collaborative clinical research. Circulation. 2018; 137:1846–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Conway BD, Stamou SC, Kouchoukos NT, Lobdell KW, Hagberg RC. Effects of gender on outcomes and survival following repair of acute type A aortic dissection. Int J Angiol. 2015;24:93–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kane AE, Howlett SE. Differences in cardiovascular aging in men and women. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2018;1065:389–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Merz AA, Cheng S. Sex differences in cardiovascular aging. Heart. 2016;102: 825–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coutinho T Arterial stiffness and its clinical implications in women. Can J Cardiol. 2014;30:756–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Samargandy S, Matthews KA, Brooks MM, Barinas-Mitchell E, Magnani JW, Janssen I, et al. Arterial stiffness accelerates within 1 year of the final menstrual period: the SWAN Heart Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2020;40:1001–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wolford BN, Hornsby WE, Guo D, Zhou W, Lin M, Farhat L, et al. Clinical implications of identifying pathogenic variants in individuals with thoracic aortic dissection. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2019;12:e002476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Norton EL, Khaja MS, Williams DM, Yang B. Type A aortic dissection complicated by malperfusion syndrome. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2019;34:610–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salis S, Mazzanti VV, Merli G, Salvi L, Tedesco CC, Veglia F, et al. Cardiopulmonary bypass duration is an independent predictor of morbidity and mortality after cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2008;22:814–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brown WR, Moody DM, Challa VR, Stump DA, Hammon JW. Longer duration of cardiopulmonary bypass is associated with greater numbers of cerebral microemboli. Stroke. 2000;31:707–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shultz B, Timek T, Davis AT, Heiser J, Murphy E, Willekes C,et al. Outcomes in patients undergoing complex cardiac repairs with cross clamp times over 300 minutes. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2016;11:105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wen M, Han Y, Ye J, Cai G, Zeng W, Liu X, et al. Peri-operative risk factors for in-hospital mortality in acute type A aortic dissection. J Thorac Dis. 2019;11: 3887–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ad N, Holmes SD, Massimiano PS, Spiegelstein D, Shuman DJ, Pritchard G, et al. Operative risk and preoperative hematocrit in bypass graft surgery: role of gender and blood transfusion. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2015;16:397–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

VIDEO 1. Discussion of the impact of sex on ATAAD presentation and outcomes after open repair. Video available at: https://www.jtcvs.org/article/S0022-5223(21)00559-6/fulltext.