Abstract

Clock genes Cry1 and Cry2, inhibitory components of core molecular feedback loop, are regarded as critical molecules for the circadian rhythm generation in mammals. A double knockout of Cry1 and Cry2 abolishes the circadian behavioral rhythm in adult mice under constant darkness. However, robust circadian rhythms in PER2::LUC expression are detected in the cultured suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of Cry1/Cry2 deficient neonatal mice and restored in adult SCN by co-culture with wild-type neonatal SCN. These findings led us to postulate the compensatory molecule(s) for Cry1/Cry2 deficiency in circadian rhythm generation. We examined the roles of Chrono and Dec1/Dec2 proteins, the suppressors of Per(s) transcription similar to CRY(s). Unexpectedly, knockout of Chrono or Dec1/Dec2 in the Cry1/Cry2 deficient mice did not abolish but decoupled the coherent circadian rhythm into three different periodicities or significantly shortened the circadian period in neonatal SCN. DNA microarray analysis for the SCN of Cry1/Cry2 deficient mice revealed substantial increases in Per(s), Chrono and Dec(s) expression, indicating disinhibition of the transactivation by BMAL1/CLOCK. Here, we conclude that Chrono and Dec1/Dec2 do not compensate for absence of CRY1/CRY2 in the circadian rhythm generation but contribute to the coherent circadian rhythm expression in the neonatal mouse SCN most likely through integration of cellular circadian rhythms.

Subject terms: Cellular neuroscience, Circadian rhythms and sleep

Introduction

The circadian rhythm in mammals is regarded as generated by the core molecular auto-feedback loop involving the clock genes, Period (Per1, Per2), Cryptochrome (Cry1, Cry2), Bmal1, and Clock, and their protein products1. In this loop, the heterodimer of BMAL1/CLOCK binds to E-box enhancer elements located on the Per1/Per2 or Cry1/Cry2 promoter and activates transcription of Per(s) and Cry(s). Increased Per1/Per2 and Cry1/Cry2 proteins in turn suppress the transactivation by BMAL1/CLOCK through direct interactions with them2,3. The core molecular loop is interlocked by at least two additional molecular feedback loops, one is the Bmal1 loop which regulates Bmal1 expression4,5 and the other is the Dec loop which suppresses the transcription of Per(s) and Cry(s) through E-box enhancers6.

Double knockout of Cry1 and Cry2 abolishes the behavioral circadian rhythm in adult mice, which occurs immediately on release into constant darkness (DD)7. However, the circadian rhythm in PER2::LUC expression is still detectable in the cultured suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of Cry1/Cry2 deficient neonatal mice, which gradually damps around the period of weaning8,9. In addition, by exposing to continuous light throughout the neonatal and adolescent period, the circadian rhythms appear in behavior under DD and PER2::LUC expression in cultured SCN of Cry1/Cry2 deficient mice10. Furthermore, the SCN of Cry1/Cry2 deficient adult mice restores the circadian PER2::LUC expression rhythm by co-culture with the SCN of wild-type (WT) neonatal mice9. These findings lead us to postulate the existence of compensatory molecule(s) for a lack of CRY1/CRY2 in the coherent expression of circadian rhythm during the early postnatal period11,12.

CHRONO binds to E-box and suppresses transcription of Per1 and Per2. Chrono deficient mice showed robust circadian behavioral rhythms with a slightly but significantly lengthened period13,14. DEC1 and DEC2 are basic helix–loop–helix transcription factors, which have been suggested as additional negative components of the core molecular loop6. They are able to bind to the E-box cis-elements and repress CLOCK/BMAL1-mediated transactivation of Per1 and Per2. The expression of Dec1 and Dec2 is negatively regulated by PER1 and PER2, forming a negative feedback loop interlocked with the core molecular loop15,16. Thus, CHRONO and DEC1/DEC2 show similar functions in the core molecular loop to CRY1/CRY2. However, circadian oscillation continues in Dec1/Dec2 deficient mice with a slight change in circadian period similar to Chrono deficient mice17. Previously, we proposed that CHRONO and DEC1/DEC2 are candidate molecules for the compensation of CRY1/CRY2 function in the core molecular loop11.

Beside the cellular oscillation, the SCN neural networks are critical for the expression of circadian PER2::LUC rhythm in the adult as well as the neonatal SCN in culture. Additional knock-out of the VIP receptor gene, Vipr2, to the Cry1/Cry2 deficient mice abolished the coherent circadian PER2::LUC rhythm in the neonatal SCN and CCD camera based imaging exhibited three clusters of cellar oscillations with different periodicities18. The features were essentially the same as those exhibited in the adult SCN of Cry1/Cry2 deficient mice, in which the circadian PER2::LUC rhythm was abolished at the SCN tissue level, whereas the circadian rhythm persisted at the cellular levels with three clusters of different periods. These findings indicate that the expression of circadian rhythm in the SCN of Cry1/Cry2 deficient mice is regulated also by the SCN neural networks.

In the present study, we examined Chrono and Dec1/Dec2 for their roles in the coherent expression of circadian rhythm in the neonatal SCN of Cry1/Cry2 deficient mice. We found that Chrono and Dec1/Dec2 expression were substantially increased in the SCN of Cry1/Cry2 deficient mice, indicating disinhibition of the transactivation by BMAL1/CLOCK. Unexpectedly, additional knockout of Chrono or Dec1/Dec2 in the Cry1/Cry2 deficient mice (triple-KO of Cry1/Cry2/Chrono or quadruple-KO of Cry1/Cry2/Dec1/Dec2/) did not abolish the circadian PER2::LUC rhythm but modified expression of coherent rhythms in the SCN. The triple-KO uncoupled the coherent circadian rhythm into three components of different periodicities and the quadruple-KO extremely shortened the circadian period. These findings indicate that Chrono and Dec1/Dec2 do not compensate for absence of Cry1/Cry2 in the circadian rhythm generation but contribute to the coherent circadian rhythm expression in the neonatal SCN most likely through the coupling of cellular circadian rhythms.

Results

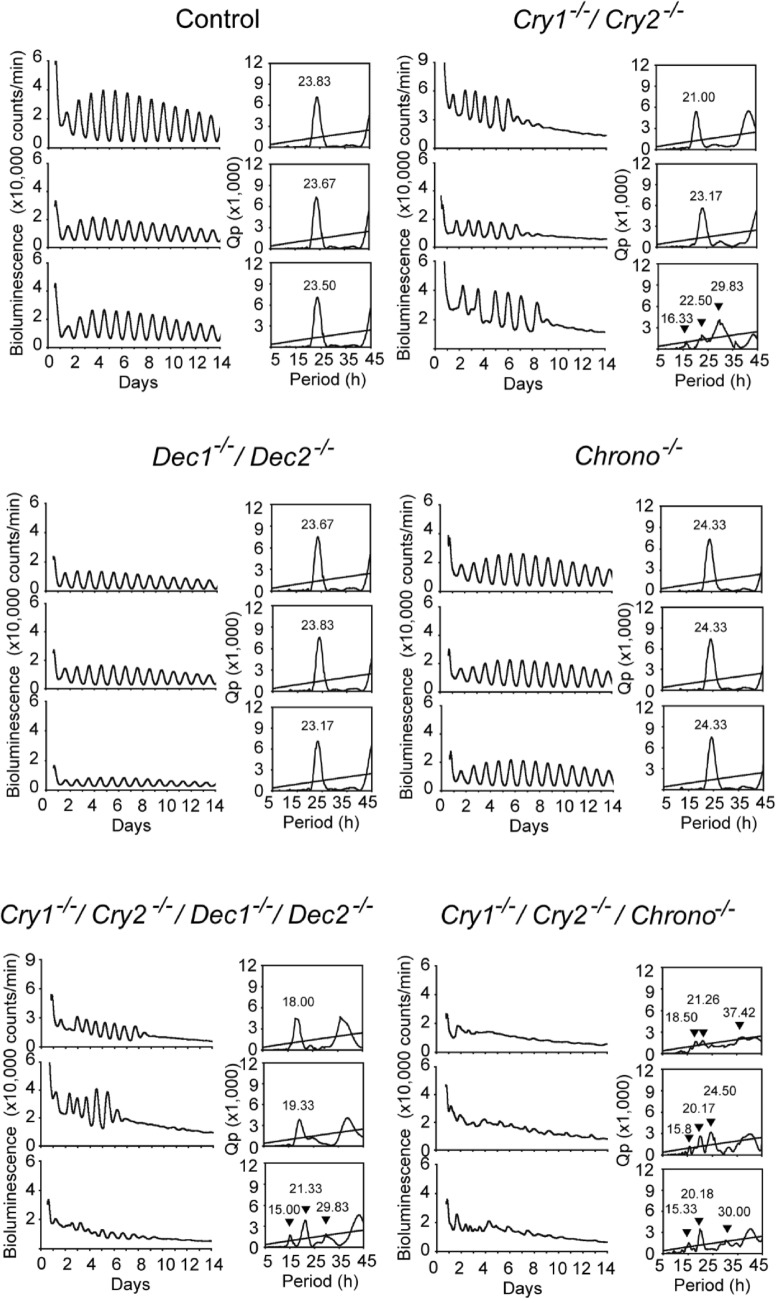

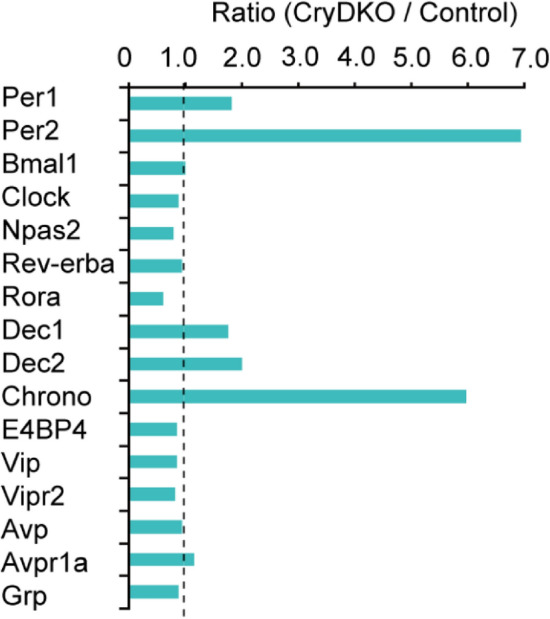

Microarray analysis in the Cry1/Cry2 deficient SCN

To determine how gene expression in the SCN of Cry1/2 deficient mice is altered by the loss of Cry1/2, transcription was measured in the SCN. SCNs were collected from neonatal (postnatal day 7: P7) and adult (2–4 month old) mice at Zeitgeber Time (ZT) 6, where the time of light-on in the light–dark cycle defines ZT 0. DNA microarray analysis revealed that the expression ratio (Cry1/Cry2 deficient vs control) increased significantly in Dec1 (ca. 180%), Dec2 (ca. 200%) and Chrono (ca.600%) in addition to Per1 (ca. 190%) and Per2 (ca. 700%) in the neonatal SCN (Fig. 1). Among 27,296 genes in the DNA microarray chip, 653 genes were upregulated (log2(FC) > 0.5) and 696 genes were downregulated (log2(FC) < 0.5) in Cry1/Cry2 deficient SCN. Interestingly, the expressions were not enhanced in Bmal1, Rev-erbα and Avp which are transcribed though E-box elements, indicating that gene expression through E-box is not always dependent on CRY1 and CRY2. Expression levels of other clock genes and clock-related genes including those involved in phosphorylation of clock gene products were not different between the control and Cry1/Cry2 deficient SCN. Similar results were obtained in the adult SCN of Cry1/Cry2 deficient mice (Supplemental Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Expression of representative genes in neonatal Cry1/Cry2 deficient and control SCN. Relative gene expression in Cry1/Cry2 deficient mice to that in the control is illustrated as a bar graph. Gene expression in Cry1/Cry2-deficient SCN was divided by that in the control SCN (Ratio). Clock genes, several clock related genes, SCN related major neuroendocrine genes, and their receptor genes are demonstrated in the graph.

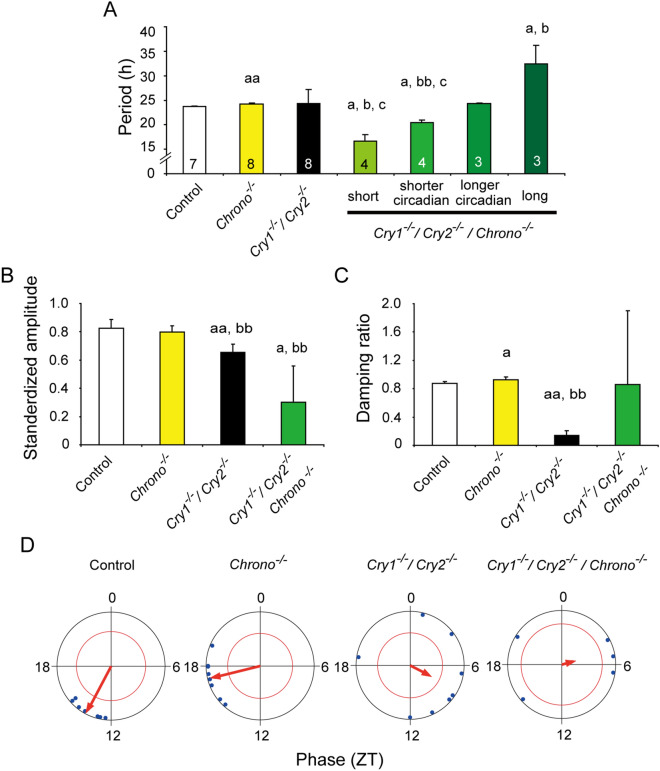

Circadian PER2::LUC rhythms in Cry/Chrono triple-KO and Cry/Dec quadruple-KO mice

To test the roles of Chrono and Dec1/Dec2 in the expression of circadian rhythms in the Cry1/Cry2 deficient neonatal mice, we made Cry1/Cry2/Chrono (Cry/Chrono) triple-KO mice and Cry1/Cry2/Dec1/Dec2 (Cry/Dec) quadruple-KO mice, both carrying a PER2::LUC reporter. We measured PER2::LUC bioluminescence in the neonatal SCN slices in culture using a photomultiplier tube9,18 and analyzed circadian rhythms by Chi-square periodogram. The periods shown are the results of Chi-square periodogram unless otherwise stated.

Robust circadian PER2::LUC rhythms were detected in the neonatal SCN of the control, Cry1/Cry2 deficient, and Dec1/Dec2 deficient mice (Fig. 2), as reported previously10,19. The circadian periods as well as phase in individual Cry1/Cry2 deficient SCN were substantially varied in marked contrast with those in the control and Dec1/Dec2 deficient SCN (Fig. 2). The large phase variation is partly due to different circadian periods of individual SCNs and/or possibly due to a failure of entrainment to a LD cycle and/or to the effects from nursing mother before the time of SCN preparation9. Significant circadian PER2::LUC rhythms were also detected in the neonatal SCN of Chrono deficient mice and Cry/Dec quadruple-KO mice (Fig. 2). The circadian PER2::LUC rhythms in the Chrono deficient SCN were similar to that in the control except for slightly but significantly longer period (24.3 ± 0.1 h vs. 23.7 ± 0.2 h; P < 0.01), whereas the circadian rhythms in Cry/Dec quadruple-KO SCN showed substantial variability in the period as in the case of Cry1/Cry2 deficient SCN (Fig. 2). In contrast to the above five genotypes, Cry/Chrono triple-KO SCN showed circadian PER2::LUC rhythms of relatively low amplitude. Periodogram analysis revealed two other rhythmic components with shorter and longer periods than that near 24 h (Fig. 2). Circadian PER2::LUC rhythms in other SCN were illustrated in Supplemental Fig. 2. To confirm the separate periodicities, the peaks that were larger than the mean level of periodicity (above the zero line of the detrended time series data) were selected and peak-to-peak intervals were calculated. Three-dimensional distribution maps of the intervals indicate the intra- as well as inter-individual differences of rhythmicity (Supplemental Fig. 3b). The intervals were concentrated at around 24 h in control, Chrono KO and Dec1/Dec2 DKO mice, whereas they distributed in a wider range in the Cry1/Cry2/Chrono triple-KO, Cry(s)/Dec(s) quadruple-KO and Cry1/Cry2 KO mice (Supplemental Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

PER2::LUC rhythms of the neonatal SCN slice culture in different genotypes. PER2::LUC rhythms in the neonatal SCN of different genotypes. Three representative rhythms are shown. Genotypes are indicated in each panel. Chi square periodograms for each rhythm in the panel of the left column. The oblique line in the peridogram indicates a significant level of P = 0.01. Triangles and numbers are the peak period of each slice.

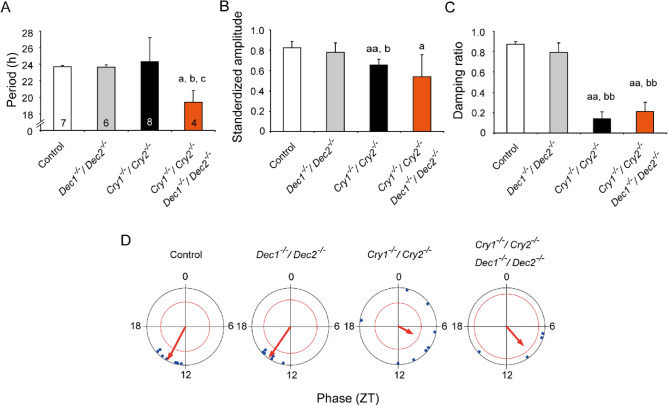

Circadian properties in Cry/Chrono triple-KO mice and Cry/Dec quadruple-KO mice

Effects of Chrono or Dec1/Dec2 deletion on the circadian PER2::LUC rhythms of Cry1/Cry2 deficient SCN were statistically analyzed and summarized in Figs. 3 and 4, respectively. In marked contrast with other genotypes examined, the SCN of the individual Cry/Chrono triple-KO mice showed essentially three major periodicities in Chi-square periodogram, but since in some animals the two distinct periodicities were detected in the near-circadian range, they were separately analyzed [short, 16.6 ± 1.4 h (n = 4); shorter circadian, 20.4 ± 0.6 h (n = 4); longer circadian, 24.3 ± 0.2 h (n = 3); long, 32.5 ± 3.7 h (n = 3)]. Some individuals showed the short, shorter and longer circadian, but others, the shorter, longer circadian and long. By the analysis of peak-to-peak intervals, there detected the corresponding 4 periodicities (short, 15.7 ± 0.8 h; shorter circadian, 20.6 ± 1.0 h; longer circadian, 24.3 ± 0.2 h; long, 31.9 ± 4.9 h) (Figs. 2 and 3A, Supplemental Fig. 2). The variability (SD) of peak-to-peak intervals distributed from 0.9 to 3.7 h in each slice and the mean variability was 2.0 h (SD = 0.9 h). The short, shorter circadian and long period were significantly different from the periods of control (23.7 ± 0.2 h) and Chrono deficient mice (24.3 ± 0.1 h). These periods were also significantly different from those of Cry1/Cry2 deficient mice (24.3 ± 2.9 h) except for the long period (Kruskal–Wallis test with post-hoc Steel-test; P < 0.01 or 0.05). The standardized amplitude was significantly lower in Cry/Chrono triple-KO mice (0.30 ± 0.26) than in the control mice (0.82 ± 0.06; P < 0.05) and Chrono deficient mice (0.80 ± 0.04; P < 0.01), but not in Cry1/Cry2 deficient mice (Fig. 3B). The damping ratio of Chrono deficient mice (0.93 ± 0.04) was significantly larger than that of Cry1/Cry2 deficient mice (0.14 ± 0.07; P < 0.01), and even that of the control mice (0.87 ± 0.03; P < 0.01) (Fig. 3C, Supplemental Fig. 3), indicating that the amplitude was maintained at a relatively constant level throughout this period in Chrono deficient mice. The damping ratio of Cry/Chrono triple-KO mice was not different from those of other genotypes due to a large standard deviation (Fig. 3C, Supplemental Fig. 3). The peak phase of PER2::LUC rhythm on the 1st day of culture was slightly but significantly delayed in Chrono deficient mice (17.1 ± 1.5 h) as compared to the control mice (13.9 ± 1.2 h; P < 0.01, Watson-Williams F-test) (Fig. 3D). The peak phases in Cry1/Cry2 deficient and Cry/Chrono triple-KO mice were variable and did not consolidate as judged from the length of the arrow in the Rayleigh plot (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

Rhythm properties of neonatal SCN in culture from the control, Chrono KO, Cry1/Cry2 deficient, and Cry1/Cry2/Chrono triple-KO mice. (A) Mean periods of PER2::LUC rhythms with standard deviations (SD) calculated by periodogram are shown as columns and vertical lines. A number in each column indicates number of SCN examined. (B) Mean standardized amplitude of PER2::LUC rhythms are expressed in a bar graph (mean ± SD). (C) Damping ratio of PER2::LUC rhythms is also shown in a bar graph (mean ± SD). Statistical comparisons, a; P < 0.05, aa; P < 0.01 vs. control, b; P < 0.05, bb; P < 0.01 vs.Chrono deficient mice, c; P < 0.05, cc; P < 0.01 vs. Cry1/Cry2 deficient mice (Kruskal–Wallis with a post-hoc Steel-test). (D) Peak phase of PER2::LUC rhythms in the 1st day of culture is illustrated as Rayleigh plot. Blue dots indicate the peak times of individual rhythms. Red arrow in each circle indicates the mean circadian phase. A red circle is 95% confidence level. If an arrow extends over the red circle, the distribution of peak phases is regarded as significantly consolidated.

Figure 4.

Rhythm properties of neonatal SCN in culture from the control, Dec1/Dec2 deficient, Cry1/Cry2 deficient, and Cry1/Cry2/ Dec1/Dec2 quadruple-KO mice. (A) Mean periods of PER2::LUC rhythms with standard deviations (SD) calculated by periodogram are shown as columns and vertical lines. A number in each column indicates the number of SCN examined. (B) Standardized amplitude of PER2::LUC rhythms are expressed in bar graph (mean ± SD). (C) Damping ratio of PER2::LUC rhythms is also shown in a bar graph (mean ± SD). Statistical comparisons, a; P < 0.05, aa; P < 0.01 vs. control, b; P < 0.05, bb; P < 0.01 vs. Dec1/Dec2 deficient mice, c; P < 0.05 vs. Cry1/Cry2 deficient mice (one-way ANOVA with a post hock Tukey–Kramer test or Kruskal–Wallis with a post-hoc Steel-test). (D) Peak phase of PER2::LUC rhythms on the 1st day of culture in ZT is illustrated as Rayleigh plot, where ZT 0 indicates the time of light-on in the light–dark cycles. Blue dots indicate the peak phases of individual rhythms. Red arrow in each circle indicates the mean circadian phase of each genotype. A red circle is 95% confidence level. If an arrow extends over the red circle, the distribution of peak phases is regarded as significantly consolidated. Data of the control and Cry1/Cry2-deficient SCN are same as in Fig. 3.

On the other hand, the periods of Cry/Dec quadruple-KO mice were 19.4 ± 1.4 h (n = 4) by Chi-square periodogram which was significantly shorter than those of the control (23.7 ± 0.2 h, n = 7; P < 0.05), Dec1/Dec2 deficient (23.6 ± 0.3 h, n = 6; P < 0.05), and Cry1/Cry2 deficient mice (24.3 ± 2.9 h, n = 8; P < 0.05) (Fig. 4A). The peak-to-peak intervals in Cry/Dec quadruple-KO mice (18.8 ± 0.5 h, n = 4) were also significantly shorter than that of the control (23.7 ± 0.1 h, n = 7). The standardized amplitude of PER2::LUC rhythm was significantly lower in both Cry1/Cry2 deficient mice (0.66 ± 0.06; P < 0.01 v.s. control, P < 0.05 v.s. Dec1/Dec2 deficient mice) and Cry/Dec quadruple-KO mice (0.54 ± 0.22; P < 0.05 v.s. control) as compared with the control mice (0.82 ± 0.06) or Dec1/Dec2 deficient mice (0.78 ± 0.09) (Fig. 4B). The damping ratio was significantly smaller (damping is larger) in Cry1/Cry2 deficient (0.14 ± 0.07; P < 0.01) and Cry/Dec quadruple-KO (0.21 ± 0.09; P < 0.01) mice than in the control (0.87 ± 0.03) or Dec1/Dec2 deficient mice (0.79 ± 0.09) (Fig. 4C, Supplemental Fig. 3). The peak phase of PER2::LUC rhythm on the 1st day of culture was located at around ZT13-14 on average in the control and Dec1/Dec2 deficient mice. They were significantly consolidated as indicated by an arrow extending over the critical red circle (95% confidence level) in the Rayleigh plot (Fig. 4D). However, the peak phases in individual SCNs were not significantly consolidated in Cry1/Cry2 deficient and in Cry/Dec quadruple-KO mice.

Discussion

In the present study, using Cry/Chrono triple-deficient and Cry/Dec quadruple-deficient mice, we demonstrate that Chrono and Dec1/Dec2 play distinct roles in the coherent expression of circadian PER2::LUC rhythm in the neonatal SCN of Cry1/Cry2 deficient mice. Chrono is involved in the integration of cellular circadian rhythms of different periodicities and Dec1/Dec2 is in the lengthening of circadian period at the earliest postnatal period. These genes compensate the expression of coherent circadian rhythm in the SCN of Cry1/Cry2 deficient mice most likely through the networks of cellular oscillation.

The expression of Chrono and Per2 were substantially and of Dec(s) and Per1 moderately increased in the SCN of Cry1/Cry2 deficient mice of both neonates and adults (Fig. 1, Fig. 1S), indicating that a lack of CRY1/CRY2 disinhibits the transcription of these genes and that the core molecular feedback loop unlikely functions in Cry1/Cry2 deficient mice. The circadian PER2::LUC rhythm in the SCN of Cry/Chrono triple-deficient mice was fragmented into three components with different periodicities and showed large cycle-to-cycle variability (Fig. 3). Of great interest, the three periodicities (16.6 ± 1.4 h, 20.4 ± 0.6 h or 24.3 ± 0.2 h, and 32.5 ± 3.7 h) are similar to those detected in the SCN of VIP receptor (Vpac2) and Cry1/Cry2 deficient mice (triple deficient) by CCD camera based imaging, in which three clusters of cellular rhythm with different periodicities (16.9 ± 1.6 h, 21.0 ± 0.4 h, and 28.3 ± 0.4 h) were detected18. Knock-out of Vpac2 abolished the coherent circadian rhythm in the neonatal SCN of Cry1/Cry2 deficient mice. The similar three clusters are also observed in the adult SCN of Cry1/Cry2 deficient mice18. Importantly, coherent circadian rhythms in PER2::LUC were restored in the adult SCN by co-culture with the WT neonatal SCN, which was accompanied by a single cellular cluster. These findings lead us to postulate that the coherent circadian rhythm in the SCN is built-up by the coupling of these three clusters of cellular oscillation. CHRONO is involved in the coupling of cellular oscillations.

The neuropeptides released from the co-cultured WT SCN are involved in the coupling of cellular oscillations through the networks of recipient SCN. The responsible neuropeptide is AVP, since administration of AVP receptor antagonists abolished the restored circadian PER2::LUC rhythm18. The abolishment of circadian rhythms in the adult Cry1/Cry2 deficient mice is likely due to a lack of the circadian release of AVP in the SCN, since Cry1/Cry2 deficiency substantially suppresses AVP gene expression18. By contrast, the role of VIP is different in the neonatal and adult SCN, which may explain why the coherent circadian PER2::LUC rhythm is preserved in the neonatal SCN but not in the adult of Cry1/Cry2 deficiency mice. In the neonatal SCN, VIP is released in a circadian fashion, whereas in the adult VIP release lacks an endogenous nature of circadian rhythm and is stimulated by lights20,21.

Tetrodotoxin (TTX) treatment to the neonatal SCN of Cry1/Cry2 deficient mice abolished the coherent circadian PER2::LUC rhythm in the SCN due to desynchronization of cellular circadian rhythms, the features of which were quite similar to those of TTX untreated adult SCN9. The periods of cellular oscillation in the TTX treated neonatal SCN distributed in a wide range (from13 up to 37 h), which is similar to the period distribution of dispersed cell culture of CRY(s)-deficient SCN. These findings also support the idea that the SCN neural networks are critical in the expression of coherent circadian rhythm in the neonatal SCN of Cry1/Cry2 deficient mice9. Based on these and above mentioned findings, we proposed a model of circadian organization in the SCN of Cry1/Cry2 deficient mice18. The cellular oscillations in the SCN are diverse in periods without mutual synchronization (basal state). The diversity of period suggests that the oscillation is a kind of molecular noise 22. In the presence of functional SCN networks, there appear three clusters of cellular oscillation due to mutual synchronization (cluster state). The oscillations of three cellular clusters are further synchronized in several ways to express the coherent circadian rhythms (coherence state). Chrono and Dec1/Dec2 are differentially involved in synchronization of cell oscillation clusters. CRY1/CRY2 could also play as a synchronizer of cellular oscillation through AVP release18.

Recently, a post-translational model was proposed for the circadian oscillation of Cry1/Cry2 deficient mice23. In this study, in addition to the robust circadian rhythms in PER2::LUC, the temperature compensation and period determination by CK1ε/δ activity were demonstrated in the cultured fibroblasts of Cry1/Cry2 deficient mice. Their findings support our hypothesis that the CRY1/CRY2 are dispensable in the circadian oscillation.

On the other hand, in Cry/Dec quadruple-KO mice the PER2::LUC rhythms in the SCN show a substantially shorter period (19.4 ± 1.4 h) than that of Cry1/Cry2 deficient mice (24.3 ± 2.9 h) (Figs. 2 and 4). In the earliest postnatal period, the SCN of Cry1/Cry2 deficient mice showed a very short period of ca. 16 h, which was gradually lengthened to ca. 24 h in a week. We postulate that in the earliest postnatal period, the integration of cellular oscillations is brought about, so that the oscillations of the shortest period are dominant in the coherent circadian rhythm, and the dominancy is gradually shifted to the oscillations of longer periods. Dec1/Dec2 is possibly involved in this gradual change of integration of cellular oscillations in the early neonatal period. A lack of Dec1/Dec2 may interrupt the cellular coupling in the earliest state of postnatal period. The site of cellular integration could be the neural or humoral networks in the SCN. The molecular core loop is unlikely involved in the change of circadian period, since Per(s) expression is disinhibited and the core molecular loop does not work in Cry1/Cry2 deficient mice. These findings indicate that DEC1 and DEC2 contribute to the lengthening of the circadian period in the earliest postnatal period.

Circadian oscillation could be generated without the core transcription-translation feedback loop (TTFL). Bmal1 is a positive element of molecular feedback loop and Bmal1 deficiency resulted in abolishment of circadian behavioral rhythms in DD24. However, periodicities in the circadian domain were detected in PER2::LUC expression in the Bmal1 deficient SCN slice culture22. The finding was interpreted in such a way that “quasi-circadian” rhythms in the Bmal1 deficient SCN have a stochastic nature produced by intercellular coupling and molecular noise. The general features of the Cry1/Cry2 deficient SCN are similar to those of the Bmal1 deficient SCN. Recently, Bmal1 deficient mice demonstrated circadian transcript rhythms in fibroblasts and liver25. Circadian rhythm was detected without the nucleus in the red blood cells in mammals, and in acetabularia, a single cell algae26,27. A lack of a TTFL of clock genes could be compensated by neural networks and/or other oscillatory mechanisms such as post-translational oscillation23 and a single molecule oscillation28.

In this study, we did not analyze the integration of cellular oscillations in the SCN. It would be interesting to know how the spatio-temporal patterns of PER2::LUC in the SCN were changed in the Cry/Chrono triple-deficient and Cry/Dec quadruple-deficient mice. Furthermore, it would be interesting to know whether the stability of PER2 in Cry/Chrono triple-deficient and Cry/Dec quadruple-deficient SCN is modulated or not, since the stability of PER2 proteins is reported to affect the length of circadian period29.

In conclusion, CHRONO and DEC1/DEC2 do not compensate for absence of CRY1/CRY2 in the circadian rhythm generation but contribute to the expression of coherent circadian rhythms in the neonatal mouse SCN. CHRONO is involved in the integration of clusters of cellular oscillations with different periods. On the other hand, DEC1/DEC2 lengthens the period in the earliest neonatal period of Cry1/Cry2 deficient mice, probably through the integration of cellular rhythms. Despite of the disinhibition of Per1/Per2 expression, the circadian period of PER2::LUC rhythm in the Cry1/Cry2 deficient SCN was comparable to that of the control SCN, suggesting the presence of other oscillatory mechanisms than TTFL in Cry1/Cry2 deficient mice.

Methods

Animals

Cry1/Cry2 KO, Dec1 KO and Chrono KO mice of C57BL/6J background were obtained from Tohoku University30, Hiroshima University31, and Riken14, respectively. Dec2 KO mice were originally established by replacing the 2.7 kb region in exons 1–5 of the Dec2 gene including the entire coding region with Neo cassette as described elsewhere31. Chrono KO mice were made by C57BL/6 background ES cell clone. Dec1 and Dec2 KO mice were backcrossed with C57BL/6J mice, and confirmed the existence of more than 99.5% of C57BL/6J background by using a speed congenic method. For the respective genotypes, only the animals were used in which all corresponding genes were knocked out except for Cry2, and deficiency of Cry2 were confirmed by PCR genotyping. The bioluminescence reporter system was introduced to each of the knockout mice by breeding with PER2::LUC homozygote mice carrying a PER2 fusion luciferase reporter19. We used only PER2::LUC homozygote mice that could be identified by PCR genotyping. Mice were bred and reared in the animal quarter at Hokkaido University Graduate School of Medicine, where environmental conditions were controlled (lights-on 6:00–18:00 h; light intensity approximately 100 lx at the bottom of cage: humidity 60 ± 10%). Both male and female mice were used for the present study. Experiments were conducted in compliance with the rules and regulations established by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Hokkaido University under the ethical permission of the Animal Research Committee of Hokkaido University (Approval No. 08-0279) with the ARRIVE guidelines.

Microarray analysis

Brain tissues of 400 μm thick were made with a microslicer (DTK-1000; Dosaka EM) at ZT6 from neonatal (postnatal day 7: P7) or adult (2–4 month old) wild type or Cry1/Cry2 deficient mice, and only the SCN area was trimmed by a surgical scalpel under a stereo microscope. All animals contained homozygote of PER2::LUC reporter. RNA was extracted using RNeasy micro kit (QIAGEN) from 8–10 mice, then performed microarray analysis (Agilent Technologies).

SCN slice preparation for culture

For the measurement of PER2::LUC bioluminescence, animals were euthanized to harvest SCNs between 8:00 and 16:00 h. Coronal SCN slices of 300 μm thick were made with a tissue chopper (Mcllwain) from neonatal mice (P7). The SCN tissue was dissected at the mid rostrocaudal region and a paired SCN was cultured on a Millicell-CM culture insert (Millipore Corporation). The culture conditions were the same as those described previously9,18. Briefly, the slice was cultured in air at 36.5 °C with 1.2 ml Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10 mM HEPES, 2.74 mM NaHCO3, 0.1 mM D-luciferase K, and 5% supplement solution the composition of which is reported elsewhere32.

Measurement of bioluminescence

Bioluminescence of the SCN tissue level was measured using a PMT (Lumicycle; Actimetrics) at 10 min intervals with an exposure time of 1 min. as described previously10. The intensity of bioluminescence was expressed in relative light units (RLU; counts/min). The measurement was continued at least for 14 days.

Data analysis

Periods of circadian PER2::LUC rhythm in the SCN culture was determined with Chi-square periodogram using bioluminescence data of initial 7 cycles. Bioluminescence records of the first 12 h were not used for rhythm analyses because of an initial high level of bioluminescence. The raw bioluminescence data were smoothed using a five-point moving average method and then detrended using a 24 h running average subtraction method9. The circadian period and its stability were also analyzed by measuring a peak and the following peak. The peaks above the mean level of the rhythmicity in the detrended time series data (the zero-line) were selected and the peak-to-peak intervals were calculated. By this method, some significant peaks in the periodogram were revealed to be harmonics and excluded from the further analyses. The rhythm amplitude was defined as the difference between the peak and trough in a cycle of 4th day in culture and standardized by dividing the amplitude by the peak level as described previously9. The damping ratio was defined as the ratio of the circadian amplitude of 14th and 4th day in culture of PER2::LUC rhythms in the SCN, since a reduction of the circadian amplitude of Cry1/Cry2 deficient SCN were expected around 10th day in culture. The peak phase in the 2nd day of culturing was analyzed as described previously9.

Statistics

A one-way ANOVA with a post-hoc Tukey–Kramer test or Kruskal–Wallis with a post-hoc Steel-test was used to analyze multiple group data (Statview or Statcel 3). A Rayleigh plot was made using the Oriana4 software (Kovach Computing Service).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Experiments were conducted in compliance with the rules and regulations established by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Hokkaido University under the ethical permission of the Animal Research Committee of Hokkaido University (Approval No. 08-0279).

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank J.S. Takahashi for providing PER2::LUC mice and T. Nakatani for animal care.

Abbreviations

- AVP

Arginine vasopressin

- DD

Continuous darkness

- KO

Knockout

- LD

Light–dark cycle

- PER2::LUC

Per2 luciferase

- PMT

Photomultiplier tube

- SCN

Suprachiasmatic nucleus

- TTFL

Transcription-translation feedback loop

- VPAC2

VIP receptor 2

- VIP

Vasoactive intestinal polypeptide

Author contributions

D.O., T.T., S.H. K.H. designed the study. T.K., K.F., and Y.K. established Dec1/2 KO mice. D.O. performed experiments. C.S. analyzed microarray data, D.O. and K.H. analyzed PER2::LUC data. D.O., S.H. K.H. wrote the paper.

Funding

This work was supported in part by The Uehara Memorial Foundation, The Nakajima Foundation, The Futaba Research Grant Program of the Futaba Foundation, Takeda Science Foundation, Kato Memorial Bioscience Foundation, Research Foundation for Opto-Science, DAIKO FOUNDATION, SECOM Science and Technology Foundation, The Project for Developing Innovation Systems of the MEXT, and Creation of Innovation Centers for Advanced Interdisciplinary Research Areas Program, Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) (SCH3362/2–1), and JSPS KAKENHI (Nos. 15H04679, 26860156, 15K12763, 16H06316, 16H06463, 18H02477, 20KK0177).

Data availability

All data generated during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files, and all materials generated during this study are available upon request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ken-ichi Honma, Email: kenhonma@med.hokudai.ac.jp.

Sato Honma, Email: sathonma@med.hokudai.ac.jp.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-98532-5.

References

- 1.Reppert SM, Weaver DR. Coordination of circadian timing in mammals. Nature. 2002;418:935–941. doi: 10.1038/nature00965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gekakis N, et al. Role of the CLOCK protein in the mammalian circadian mechanism. Science (N. Y.) 1998;280:1564–1569. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5369.1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hogenesch JB, Gu YZ, Jain S, Bradfield CA. The basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS orphan MOP3 forms transcriptionally active complexes with circadian and hypoxia factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:5474–5479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Preitner N, et al. The orphan nuclear receptor REV-ERBalpha controls circadian transcription within the positive limb of the mammalian circadian oscillator. Cell. 2002;110:251–260. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00825-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ueda HR, et al. A transcription factor response element for gene expression during circadian night. Nature. 2002;418:534–539. doi: 10.1038/nature00906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Honma S, et al. Dec1 and Dec2 are regulators of the mammalian molecular clock. Nature. 2002;419:841–844. doi: 10.1038/nature01123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van der Horst GT, et al. Mammalian Cry1 and Cry2 are essential for maintenance of circadian rhythms. Nature. 1999;398:627–630. doi: 10.1038/19323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maywood ES, Chesham JE, O'Brien JA, Hastings MH. A diversity of paracrine signals sustains molecular circadian cycling in suprachiasmatic nucleus circuits. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:14306–14311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1101767108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ono D, Honma S, Honma K. Cryptochromes are critical for the development of coherent circadian rhythms in the mouse suprachiasmatic nucleus. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:1666. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ono D, Honma S, Honma K. Postnatal constant light compensates Cryptochrome1 and 2 double deficiency for disruption of circadian behavioral rhythms in mice under constant dark. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e80615. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ono D, Kori H, Honma S, Daan S, Honma K. Cellular Circadian Rhythms in the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus: An Oscillatory or a Stochastic Process? Hokkaido University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tokuda, I., Herzel, H., Ono, D., Honma, S., & Honma, K. Oscillator Network modeling of the suprachiasmatic nucleus in Cry1/Cry2 double deficient mice. 147–161 (2014).

- 13.Anafi RC, et al. Machine learning helps identify CHRONO as a circadian clock component. PLoS Biol. 2014;12:e1001840. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goriki A, et al. A novel protein, CHRONO, functions as a core component of the mammalian circadian clock. PLoS Biol. 2014;12:e1001839. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamaguchi H, et al. Expression of the gene for Dec2, a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor, is regulated by a molecular clock system. Biochem. J. 2004;382:43–50. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawamoto T, et al. A novel autofeedback loop of Dec1 transcription involved in circadian rhythm regulation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;313:117–124. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.11.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rossner MJ, et al. Disturbed clockwork resetting in Sharp-1 and Sharp-2 single and double mutant mice. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2762. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ono D, Honma S, Honma K. Differential roles of AVP and VIP signaling in the postnatal changes of neural networks for coherent circadian rhythms in the SCN. Sci. Adv. 2016;2:e1600960. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1600960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoo SH, et al. PERIOD2::LUCIFERASE real-time reporting of circadian dynamics reveals persistent circadian oscillations in mouse peripheral tissues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:5339–5346. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308709101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ban Y, Shigeyoshi Y, Okamura H. Development of vasoactive intestinal peptide mRNA rhythm in the rat suprachiasmatic nucleus. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:3920–3931. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-10-03920.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shinohara K, Funabashi T, Kimura F. Temporal profiles of vasoactive intestinal polypeptide precursor mRNA and its receptor mRNA in the rat suprachiasmatic nucleus. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 1999;63:262–267. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(98)00289-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ko CH, et al. Emergence of noise-induced oscillations in the central circadian pacemaker. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000513. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Putker M, et al. CRYPTOCHROMES confer robustness, not rhythmicity, to circadian timekeeping. EMBO J. 2021;40:e106745. doi: 10.15252/embj.2020106745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bunger MK, et al. Mop3 is an essential component of the master circadian pacemaker in mammals. Cell. 2000;103:1009–1017. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00205-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ray S, et al. Circadian rhythms in the absence of the clock gene Bmal1. Science. 2020;367:800–806. doi: 10.1126/science.aaw7365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sweeney BM, Haxo FT. Persistence of a photosynthetic rhythm in enucleated acetabularia. Science. 1961;134:1361–1363. doi: 10.1126/science.134.3487.1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woolum JC. A re-examination of the role of the nucleus in generating the circadian rhythm in Acetabularia. J. Biol. Rhythms. 1991;6:129–136. doi: 10.1177/074873049100600203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abe J, et al. Circadian rhythms. Atomic-scale origins of slowness in the cyanobacterial circadian clock. Science. 2015;349:312–316. doi: 10.1126/science.1261040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meng QJ, et al. Entrainment of disrupted circadian behavior through inhibition of casein kinase 1 (CK1) enzymes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:15240–15245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005101107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Honma S, Yasuda T, Yasui A, van der Horst GT, Honma K. Circadian behavioral rhythms in Cry1/Cry2 double-deficient mice induced by methamphetamine. J. Biol. Rhythms. 2008;23:91–94. doi: 10.1177/0748730407311124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakashima A, et al. DEC1 modulates the circadian phase of clock gene expression. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;28:4080–4092. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02168-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Inagaki N, Honma S, Ono D, Tanahashi Y, Honma K. Separate oscillating cell groups in mouse suprachiasmatic nucleus couple photoperiodically to the onset and end of daily activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007;104:7664–7669. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607713104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files, and all materials generated during this study are available upon request.