Abstract

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) DNA loads in paired leukocyte and plasma samples from 199 patient visits by 66 patients with CMV retinitis were determined. Leukocyte CMV load determinations had a greater range of values (mean, 24,587 copies/106 leukocytes; maximum, 539,000) than did plasma CMV load determinations (mean, 10,302 copies/ml; maximum, 386,000), and leukocyte viral loads were detectable in a greater proportion of patients at the time of diagnosis of CMV retinitis prior to initiation of anti-CMV therapy (82%) than were plasma viral loads (64%) (P = 0.0078). Agreement with CMV blood cultures was slightly better for plasma (κ = 0.68) than for leukocytes (κ = 0.53), due to a greater proportion of patients with detectable viral loads in leukocytes having negative blood cultures.

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is an important pathogen in patients with AIDS (6, 10, 11, 16). Although CMV may affect multiple organs, CMV retinitis is the most frequently encountered presentation in patients with AIDS, and it accounts for 75 to 85% of CMV disease in these patients (6, 10).

Quantification of the amount of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) RNA in the plasma (HIV load) has become established as a useful clinical tool for monitoring patients with HIV infection. It predicts the progression of HIV disease and morbidity (14), and suppression of the HIV load by using highly active antiretroviral therapy results in improvement in immune function, reduction in opportunistic infections, and increased survival (7, 8, 15).

In an analogous manner, the amount of CMV DNA in the blood (CMV load) can be quantitated. It has been proposed that the CMV load may be useful for identifying patients at high risk for the development of CMV disease and/or for monitoring patients with CMV disease (2, 3, 17, 19). The detection of circulating CMV DNA in plasma (17) or whole blood (2) predicts the subsequent development of CMV disease in patients with low CD4+-T-cell counts, and the qualitative detection of CMV DNA in the whole blood correlates with new episodes of CMV disease in patients with CMV retinitis (3). Because latent CMV is thought to reside in leukocytes, it is unclear whether quantification of the CMV load in leukocytes or plasma is a better method for identifying and monitoring these patients. Here we report our experience in simultaneously quantifying the amount of CMV DNA from leukocytes and plasma in samples obtained prospectively from a cohort of patients with CMV retinitis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Cytomegalovirus Retinitis and Viral Resistance Study is a prospective epidemiologic study of patients with CMV retinitis and AIDS (5). Eligible patients had newly diagnosed CMV retinitis and were untreated prior to enrollment. The diagnosis of CMV retinitis was made on clinical grounds by indirect ophthalmoscopy through a dilated pupil (5). At the time of enrollment, patients gave a medical history, had an eye examination, and underwent phlebotomy for culture of blood for CMV and assessment of the CMV loads in blood leukocytes and plasma. All baseline determinations were performed on specimens obtained prior to initiation of therapy. Patients were treated according to best medical judgement, and therapy was selected without knowledge of the baseline results. Patients were monitored monthly for clinical outcomes. Blood cultures for CMV and assessment of CMV load were performed at 1 and 3 months after enrollment and every 3 months thereafter.

Culture of blood for CMV.

Blood samples for viral culture were transported to the Virology Laboratory within 60 min of collection. Cultures for CMV were processed in tubes of MRC-5, WI-38, and MRHF fibroblasts. Tubes were read daily for CMV-specific cytopathic effect, and CMV was confirmed by fluorescence microscopy. All uncontaminated negative cultures were held for 6 weeks before being recorded as negative (5, 12, 13).

Quantification of CMV DNA in plasma and leukocytes.

Quantification of CMV DNA (viral load) was performed for plasma and leukocytes by using the COBAS AMPLICOR CMV MONITOR system according to the manufacturer’s instructions (4). Briefly, plasma (200 μl) was added to lysis reagent (600 μl) which contained a quantitation standard. DNA was precipitated with isopropanol (800 μl) and pelleted by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 15 min. The pellet was washed with 70% ethanol and resuspended in specimen diluent (400 μl).

Leukocytes were separated from EDTA-treated blood by sedimentation with 6% (wt/vol) dextran in phosphate-buffered saline. The leukocyte-rich supernatant was centrifuged at 450 × g for 15 min, and the pellet was resuspended in sterile distilled water (5 ml) to lyse erythrocytes. Culture medium (10 ml of minimal essential medium with 10% fetal calf serum) was added, and the sample was again centrifuged at 450 × g for 15 min. Erythrocyte lysis with distilled water was repeated if necessary. Leukocytes were counted, aliquoted into microcentrifuge tubes (2 × 106 cells/tube), and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min. Ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline was added to the cell pellet, and 200 μl containing 8 × 105 cells was transferred to 600 μl of lysis buffer with a quantitation standard. This concentration of leukocytes had been determined previously to give the optimal results (13a). Subsequent specimen preparation steps as described above for plasma were followed.

The extracted sample (50 μl) was added to PCR Master Mix (50 μl) and placed in the COBAS AMPLICOR instrument for automated amplification, detection of CMV DNA, and quantitation. This system amplifies a 365-bp region of the CMV DNA polymerase gene (UL 54). The instrument captures the biotinylated amplification products with magnetic particles coated with specific oligonucleotide probes and detects the bound products calorimetrically. The quantitation standard contains DNA with primer binding sites identical to those of the CMV target and a unique probe binding region that allows it to be distinguished from the CMV amplicon. CMV DNA levels in the test specimen are determined by comparing the absorbance of the specimen to the absorbance obtained for the quantitation standard. The dynamic range for quantitation is approximately 3 log10 units, with 400 copies as the lower limit of detection.

Statistical methods.

Because of the skewed nature of the distribution of the viral load data, these values were transformed to log10 for statistical analyses. The relationship between results for CMV DNA from leukocytes and from plasma was assessed by linear regression, both on the actual scale and on the log scale, and the correlation coefficient was computed. McNemar’s test for paired data was used to determine whether there was any difference in the frequency of positive CMV load measurements between leukocytes and plasma (18). Kappa statistics were computed to estimate the agreement beyond that of chance between positive cultures and detectable CMV load.

RESULTS

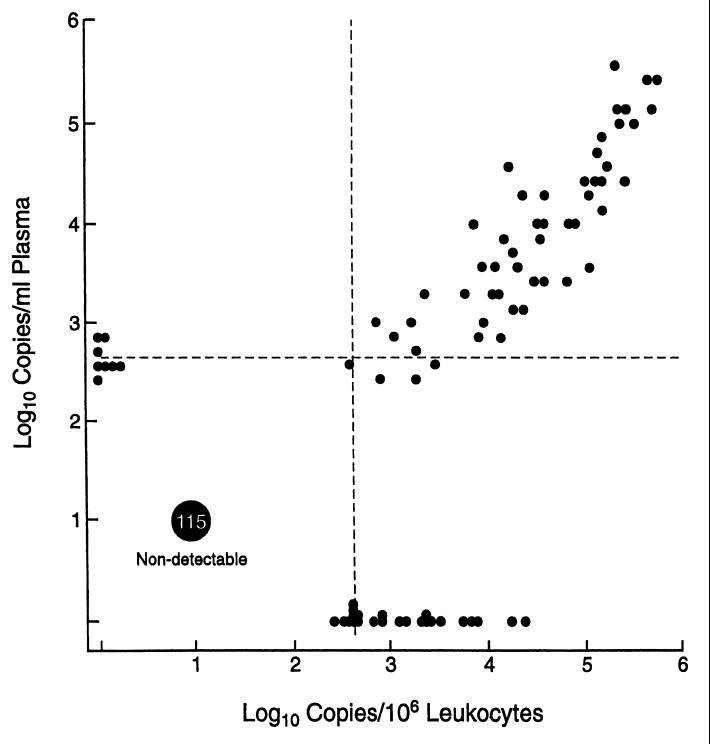

Specimens for comparison of the quantity of CMV DNA in the blood (CMV load) were available from 199 patient visits by 66 patients with CMV retinitis. Of these, 44 patient visits were at the time of diagnosis of CMV retinitis and prior to the initiation of anti-CMV therapy, and 155 visits were follow-up visits, at which time the patients were on treatment for CMV retinitis. Twenty-two patients had only follow-up visits. The comparison of plasma CMV load and leukocyte CMV load is outlined in Table 1. In general, measurements of the CMV load in leukocytes had a greater range of values than did measurements of the CMV load in plasma. A scatter plot comparing leukocyte CMV load and plasma CMV load is presented in Fig. 1. There was a good correlation between leukocyte CMV load and plasma CMV load (r = 0.81; P < 0.0001). Because of the large number of specimens with undetectable CMV loads (<400 copies) from both sources, we also analyzed the correlation between leukocyte CMV load and plasma CMV load for the 84 specimens with a detectable viral load by either technique. In this analysis, there still was a good correlation between leukocyte and plasma CMV loads (r = 0.79; P < 0.0001).

TABLE 1.

CMV loads in plasma and leukocytes in patients with CMV retinitis

| Specimens | Parameter | Value for:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma | Leukocytes | ||

| Alla | No. of specimens | 199 | 199 |

| Mean viral load ± SD | 10,302 ± 43,180 copies/ml | 24,587 ± 76,610 copies/106 leukocytes | |

| Mean log10 viral load ± SD | 1.12 ± 1.77 | 1.54 ± 2.05 | |

| Maximum viral load | 386,000 copies/ml | 539,000 copies/106 leukocytes | |

| Maximum log10 viral load | 5.59 | 5.73 | |

| % Undetectable (<400 copies) | 74 | 65 | |

| Untreated patientsb | No. of specimens | 44 | 44 |

| Mean viral load ± SD | 21,442 ± 52,135 copies/ml | 66,027 ± 123,016 copies/106 leukocytes | |

| Mean log10 viral load ± SD | 2.55 ± 1.96 | 3.57 ± 1.76 | |

| Median viral load | 1,645 copies/ml | 12,500 copies/106 leukocytes | |

| Median log10 viral load | 3.20 | 4.09 | |

| Maximum viral load | 279,000 copies/ml | 539,000 copies/106 leukocytes | |

| Maximum log10 viral load | 5.45 | 5.73 | |

| % Undetectable (<400 copies) | 36 | 18 | |

At diagnosis of CMV retinitis and at follow-up visits.

At diagnosis of CMV retinitis only.

FIG. 1.

Scatter plot of CMV load in plasma versus that in leukocytes in patients with CMV retinitis.

Because most of the specimens came from follow-up visits, when patients were on treatment, a large number of specimens had an undetectable CMV load by either technique. However, the leukocyte CMV load was elevated (detectable) in a greater proportion of patients than was the plasma CMV load; 65% of the CMV load measurements from leukocytes were undetectable, whereas 74% of the measurements from plasma were undetectable (McNemar’s test, P = 0.0009). There was a barely significant difference between the two sources at follow-up visits; 79% of follow-up visit measurements from leukocytes were undetectable, whereas 85% from plasma were undetectable (P = 0.049). Therefore, we analyzed the subgroup of specimens obtained from patients at the time of diagnosis of CMV retinitis, prior to the initiation of anti-CMV therapy, a time when most patients might be expected to have a detectable CMV load. At the time of diagnosis of CMV retinitis, a significantly greater proportion of patients had a detectable CMV load in leukocytes than in plasma; 82% of patients had a detectable CMV load in leukocytes, and 64% had a detectable load in plasma (P = 0.0078). The measurements of CMV loads in leukocytes at the time of diagnosis of CMV retinitis also had a greater range of values than did those of loads in plasma (Table 1).

We evaluated the agreement between CMV load measurements and blood cultures for CMV (Table 2). In general, if a patient had a positive blood culture for CMV, then the CMV load was detectable with either leukocytes (94%) or plasma (91%) as the source, and there were no significant differences between the two sources (P = 1.00). The results were similar both at diagnosis of CMV retinitis (95% for plasma and 100% for leukocytes; P = 1.00) and at follow-up (87% for plasma and 87% for leukocytes; P = 1.00). However, a CMV load was detectable for a greater proportion of patients than was a positive blood culture, whether from plasma (51 specimens) or from leukocytes (68 specimens). A higher proportion of specimens with a detectable viral load in plasma showed a positive blood culture for CMV (63%) than did those with a detectable viral load in leukocytes (49%). Similar results were seen at the time of diagnosis of CMV retinitis and at follow-up visits (Table 2). Overall, the agreement between blood cultures and CMV loads was slightly greater for plasma (κ = 0.68) than for leukocytes (κ = 0.53). The agreement was better for plasma both at the time of diagnosis of CMV retinitis (κ = 0.56 for plasma versus κ = 0.31 for leukocytes) and at follow-up visits (κ = 0.64 for plasma and κ = 0.48 for leukocytes).

TABLE 2.

Comparison of CMV loads in plasma and leukocytes with blood culture results for patients with CMV retinitis

| Specimens (no. of positive CMV blood cultures) | Parameter | Value for:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma | Leukocytes | ||

| Alla (35) | No. of specimens | 197d | 197 |

| % of blood culture-positive patient visits with detectable CMV load | 91 | 94 | |

| No. of patient visits with detectable CMV load | 51 | 68 | |

| % of patient visits with detectable CMV load with positive blood culture | 63 | 49 | |

| Agreement between CMV blood cultures and CMV load (κ) | 0.68 | 0.53 | |

| Untreated patientsb (20) | No. of specimens | 44 | 44 |

| % of blood culture-positive patient visits with detectable CMV load | 95 | 100 | |

| No. of patient visits with detectable CMV load | 28 | 36 | |

| % of patient visits with detectable CMV load with positive blood culture | 68 | 56 | |

| Agreement between CMV blood cultures and CMV load (κ) | 0.56 | 0.31 | |

| Treated patientsc (15) | No. of specimens | 153 | 153 |

| % of blood culture-positive patient visits with detectable CMV load | 87 | 87 | |

| No. of patient visits with detectable CMV load | 23 | 32 | |

| % of patient visits with detectable CMV load with positive blood culture | 57 | 41 | |

| Agreement between CMV blood cultures and CMV load (κ) | 0.64 | 0.48 | |

At diagnosis of CMV retinitis and at follow-up visits.

At diagnosis of CMV retinitis only.

At follow-up visits only.

There were two patient visits for which there was no blood culture result.

DISCUSSION

Assessment of the amount of HIV RNA present in plasma (HIV load) has become an important tool in the clinical management of patients with AIDS, particularly in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy (7, 8). Similarly, it appears that the assessment of the amount of CMV DNA in the blood (CMV load) may become a useful tool for identifying patients at high risk for the development of CMV disease and for monitoring patients with CMV disease on treatment. Zipeto et al. (19) reported that the CMV load was elevated in patients with CMV disease compared to patients without CMV disease, whether the source of CMV DNA was leukocytes or plasma. Both Shinkai et al. (17) and Bowen et al. (2) have reported that qualitative assessment of plasma CMV load correlated with the subsequent development of CMV disease in patients at high risk for CMV disease because of their low CD4+-T-cell counts. Bowen et al. (3) reported that CMV DNA was detectable in blood in patients with CMV retinitis on treatment and that a high proportion of patients with a positive plasma CMV load developed new episodes of CMV disease. These studies all suggested that the assessment of CMV load could be a useful tool in the management of patients.

In our study we used the Roche COBAS AMPLICOR assay for CMV load to compare the results with plasma and leukocytes as the sources of CMV DNA. Measurement of the CMV load in leukocytes detected CMV DNA in the blood in a greater proportion of patients both at the time of diagnosis of CMV retinitis and during follow-up and had a greater range of values than did measurement of the CMV load in plasma. The two sources use different denominators (milliliters of plasma versus 106 leukocytes) and therefore are not directly comparable. However, given the typical number of leukocytes per milliliter of blood (106 to 107), a calculated comparison likely would show an even greater disparity. However, measurements for the two sources were highly correlated, as indicated by the high value of the correlation coefficient.

Viral load measurements can be performed more rapidly than cultures for CMV. Both sources of CMV DNA for measurement of the CMV load were successful in identifying patients who had positive blood cultures for CMV, and there were no significant differences between assays with leukocytes and plasma in the ability to identify patients with a positive blood culture either at diagnosis of CMV retinitis or during follow-up. Conversely, a CMV load from either source was detectable for a greater proportion of patients than was a positive blood culture for CMV, and leukocyte CMV loads were detectable in a greater proportion of blood culture-negative patients than were plasma CMV loads, resulting in better agreement (higher κ’s) between blood cultures and plasma CMV loads than between blood cultures and leukocyte CMV loads. Boivin et al. (1) compared plasma CMV load and leukocyte CMV load in a group of patients with and without CMV disease. They concluded that quantitative leukocyte CMV load was superior to qualitative plasma CMV load for detecting patients with CMV disease, based upon a superior specificity and positive predictive value. However, their quantitative assay used a threshold of detection of 16,000 copies, which is substantially different from ours, and our study evaluated only patients with CMV disease at diagnosis and during follow-up. Whether the greater number of patients detected by leukocyte CMV load will prove to be more clinically useful remains to be determined. Long-term follow-up studies of a greater number of patients might determine whether assessment of the CMV load in plasma or in leukocytes will be better correlated with clinical outcomes, such as progression of retinitis and occurrence of resistant CMV.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grant EY-10268 from the National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health. Roche Molecular Systems, Inc., provided the equipment and reagents.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boivin G, Handfield J, Toma E, Murray G, Lalonde R, Bergeron M G. Comparative evaluation of the cytomegalovirus DNA load in polymorphonuclear leukocytes and plasma of human immunodeficiency virus-infected subjects. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:355–360. doi: 10.1086/514190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bowen E F, Sabin C A, Wilson P, Griffiths P D, Davey C C, Johnson M A, Emery V C. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) viraemia detected by polymerase chain reaction identifies a group of HIV-positive patients at high risk of CMV disease. AIDS. 1997;11:889–893. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199707000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowen E F, Emery V C, Wilson P, Johnson M A, Davey C C, Sabin C A, Farmer D, Griffiths P D. Cytomegalovirus polymerase chain reaction viraemia in patients receiving ganciclovir maintenance therapy for retinitis. AIDS. 1998;12:605–611. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199806000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DiDomenico N, Link H, Knobel R, Caratsch T, Weschler W, Loewy Z G, Rosenstraus M. COBAS AMPLICOR™: fully automated RNA and DNA amplification and detection system for routine diagnostic PCR. Clin Chem. 1996;42:1915–1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Enger C, Jabs D A, Dunn J P, Forman M S, Bressler N M, Margolick J B, Charache P for the CRVR Research Group. Viral resistance and CMV retinitis: design and methods of a prospective study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 1997;4:41–48. doi: 10.3109/09286589709058060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gallant J E, Moore R D, Richman D D, Keruly J, Chaisson R E. Incidence and natural history of cytomegalovirus disease in patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus disease treated with zidovudine. The Zidovudine Epidemiology Group. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:1223–1227. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.6.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gulick R M, Mellors J W, Havlir D, Eron J J, Gonzalez C, McMahon D, Richman D D, Valentine F T, Jonas L, Meibohm A, Emini E A, Chodakewitz J A. Treatment with indinavir, zidovudine, and lamivudine in adults with human immunodeficiency virus infection and prior antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:734–739. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709113371102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hammer S M, Squires K E, Hughes M D, Grimes J M, Demeter L M, Currier J S, Eron J J, Jr, Feinberg J E, Balfour H H, Jr, Deyton L R, Chodakewitz J A, Fischl M A. A controlled trial of two nucleoside analogues plus indinavir in persons with human immunodeficiency virus infection and CD4 cell counts of 200 per cubic millimeter or less. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:725–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709113371101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hiyoshi M, Tagawa S, Takubo T, Tanaka K, Nakao T, Higeno Y, Tamura K, Shimaoka M, Fujii A, Higashihata M, Yasui Y, Kim T, Hiraoka A, Tatsumi N. Evaluation of the AMPLICOR CMV test for direct detection of cytomegalovirus in plasma specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2692–2694. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.10.2692-2694.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoover D R, Peng Y, Saah A, Semba R, Detels R R, Rinaldo C R, Jr, Phair J P. Occurrence of cytomegalovirus retinitis after human immunodeficiency virus immunosuppression. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996;114:821–827. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1996.01100140035004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jabs D A. Ocular manifestations of HIV infection. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1995;93:623–683. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jabs D A, Dunn J P, Enger C, Forman M S, Bressler N, Charache P for the CMV Retinitis and Viral Resistance Study Group. Cytomegalovirus retinitis and viral resistance. 2. Prevalence of resistance at diagnosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996;114:809–814. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1996.01100140023002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jabs D A, Enger C L, Dunn J P, Forman M S for the CMV Retinitis and Viral Resistance Study Group. Cytomegalovirus retinitis and viral resistance. 4. Ganciclovir resistance. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:770–773. doi: 10.1086/514249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13a.Kao, S. Y. Personal communication.

- 14.Mellors J W, Rinaldo G P, Jr, White R M, Todd J A, Kingsley L A. Prognosis in HIV-1 infection predicted by the quantity of virus in plasma. Science. 1996;272:1167–1170. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5265.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palella F J, Jr, Delaney K M, Moorman A C, Loveless M O, Fuhrer J, Satten G A, Aschman D J, Holmberg S D The HIV Outpatients Study Investigators. Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:853–860. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803263381301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peter P, Hirschtick R E, Phair J, Chmiel J S, Poggensee L, Murphy R. Risk of developing cytomegalovirus in persons infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. J Acquired Immune Defic Syndr. 1992;5:1069–1074. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shinkai M, Bozzette S A, Powderly W, Frame P, Spector S A. Utility of urine and leukocyte cultures and plasma DNA polymerase chain reaction for identification of AIDS patients at risk for developing human cytomegalovirus disease. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:302–308. doi: 10.1093/infdis/175.2.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siegel S. The McNemar test for the significance of changes. In: Harlow H, editor. Nonparametric statistics for the behavioral sciences. New York, N.Y: McGraw-Hill Book Company; 1956. pp. 63–67. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zipeto D, Morris S, Hong C, Dowling A, Wolitz R, Merigan T C, Rasmussen L. Human cytomegalovirus (CMV) DNA in plasma reflects quantity of CMV DNA present in leukocytes. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2607–2611. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.10.2607-2611.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]