Abstract

BACKGROUND

The outcomes of Hodgkin´s lymphoma (HL) in México have not been widely reported. Simplified and affordable treatments have been adopted in middle-income countries.

AIM

The aim was to evaluate long-used therapies for HL in México in a long-term basis.

METHODS

In a 34-year time period, 88 patients with HL were treated at a single institution in México. Patients were treated with adriamycin bleomycin vinblastine and dacarbazine (ABVD) or mechlorethamine, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone (MOPP). Relapsed or refractory patients were given ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide (ICE) followed by autologous or allogeneic stem cell transplants.

RESULTS

Thirty-seven women and 51 men were included; the median age was 29 years. Patients were followed for a mean of 128 mo. The 310-mo overall survival (OS) was 83% for patients treated with MOPP and 88% for those treated with ABVD. The OS of patients who received autologous stem cell transplantation was 76% (330 mo) vs 93% (402 mo) in those who did not.

CONCLUSION

HL may be less aggressive in Mexican population than in Caucasians. Combined chemotherapy renders acceptable results, regardless of clinical stage.

Keywords: Hodgkin, Lymphoma, Treatment, ABVD chemotherapy

Core Tip: In a retrospective, observational long-term study, our group found that the treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma in a resource-constrained background may still rely on the use of the traditional adriamycin bleomycin vinblastine and dacarbazine treatment regimen in order to achieve acceptable outcomes. The observations were consistent across different stages of disease and may serve to propose new studies focusing on the comparison of newly approved therapies in contexts where there are some healthcare limitations.

INTRODUCTION

Hodgkin´s lymphoma (HL) is the model of curative care, with radiation therapy, combination chemotherapy, staging approaches, peripheral blood-stem cell transplantation, and immunotherapy[1]. Following the initial demonstration that radiotherapy could eradicate limited-stage disease, multiagent chemotherapy regimens proved to be curative in a large proportion of patients with advanced disease[1]. In the 40 years since De Vita and colleagues developed the mechlorethamine, vincristine, procarbazine, prednisone (MOPP) chemotherapy regimen, much has been learned about risk stratification to minimize treatment-related toxicity[2]. Doxorubicin (i.e. adriamycin), bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine (ABVD), the most commonly used regimen for both early and advanced stage HL, was developed in the mid-70s[2] and continues to be a standard of care in HL[3]. In recent years, there have been advances, with the introduction of novel therapies and changes in the management algorithms[1]. However, the performance of newer therapies remains unclear in real-world conditions, especially for overall survival (OS) and quality of life of persons with malignant diseases[4]. We analyze here the results of the treatment of a group of 88 patients with HD over a 34-year period at a single institution, treated with combined chemotherapy in a resource-constrained setting of a single institution.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

All consecutive patients seeking medical care for HL at our institution after 1986 and followed for at least 3 mo were entered into the study. A diagnosis of HL was based on the histological study of a pathology specimen, mainly a lymph node; the same pathologist analyzed all the specimens and defined the histological subtype[5]. The clinical stage was defined according to the Ann Arbor classification[5]. Bone marrow biopsies were done only in patients with clinical stages III or IV[6]. Computed tomography (CT) scans were done in all cases prior to starting treatment. Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) scans have been performed since 2002. The study was approved by the institutional review board, and all participants signed an informed consent.

Treatment

Between 1986 and 1997, patients were treated with MOPP, i.e. nitrogen mustard (6 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8 of the cycle), vincristine (1.4 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8), procarbazine (100 mg/m2 on days 1 through 14) and prednisone (40 mg/m2 during cycles 1 and 4 for 14 d)[7]. After 1997, patients were treated with ABVD, i.e. doxorubicin (25 mg/m2), vinblastine (6 mg/m2), dacarbazine (375 mg/m2) and bleomycin (10000 units/m2) on days 1 and 15 of every 4 wk[8] as frontline therapy. Per local protocol, stages I and II, were treated with four cycles of chemotherapy and the response was assessed by a CT scan. If disease activity persisted at that time, four additional cycles were given, whereas two additional cycles were given if the CT scan was negative. For stages III and IV, the CT scans were performed after six cycles, and two or four more cycles were delivered depending on the results, as described above. Bleomycin was administered only in the first three courses and the doxorubicin dose was adjusted to avoid delivering more than 450 mg/m2. FDG-PET scans have been performed at the end of treatment since 2002. Scans were not performed between cycles. Only patients with disease activity at the end of treatment received radiotherapy. Patients showing activity after treatment were considered as refractory and treated with four courses of ifosfamide, carboplatin and etoposide (ICE)[9]. Autologous or allogeneic peripheral blood hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) were given to refractory patients after achieving complete remission. High-dose melphalan (200 mg/m2) was used in autologous transplants; cyclophosphamide, fludarabine, and busulfan were used in allogeneic transplants, which were all from HLA-identical siblings[10]. After the completion of treatment, patients were follow-up every 2 mo for 1 year and every 4 mo from then on. No FDG-PET scans were done during follow-up, unless clinically indicated.

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome measure was OS, defined as the time elapsed between the diagnosis of HL and death from any cause, with censoring of patients who were alive on the last follow-up date. Differences were assessed with Fisher’s exact test. OS was estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences between groups were compared with the log-rank test[11]. Two-sided P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The statistical analysis was carried preformed with Prism 8 (GraphPad Inc. San Diego, CA, United States).

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

Of the 91 patients with HL identified between 1986 and 2020, 88 were followed for 3 mo or more and were included in the analysis. There were 37 women and 51 men. The median age was 29 years (range: 5-73 years). There were 62 patients with nodular sclerosing HL (70%), 19 with mixed cellularity HL, two with lymphocyte depleted HL, and one with lymphocyte predominant HL. In four cases, the histologic variant could not be defined. According to the Ann Arbor classification[5], five patients were stage I, 48 were stage II, 19 were stage III, and 16 were stage IV. Ten patients presented with a mediastinal mass larger than 10 cm in the chest X-ray film. Three cases presented with relapsed disease (Table 1).

Table 1.

Salient features of 88 patients with Hodgkin´s lymphoma

| Sex | Women | 37 (42) |

| Men | 51 (57.9) | |

| Age, yr | Median 29 (range: 5-73) | |

| Type | Nodular sclerosing | 62 (70) |

| Mixed cellularity | 19 (21.5) | |

| Lymphocyte depleted | 2 (2.2) | |

| Lymphocyte predominant | 1 (1.1) | |

| Stage | Stage I | 5 (5.6) |

| Stage II | 48 (54.5) | |

| Stage III | 19 (1.5) | |

| Stage IV | 16 (18.1) | |

Data are n (%)

Treatment patterns

As frontline therapy, all patients were offered chemotherapy (ChT). Twelve received MOPP and 70 received ABVD; three were treated with initial radiotherapy (RT): two refused ChT, and one was referred after receiving RT. Relapsed or refractory patients were treated with ICE and a subsequent autologous or allogeneic HSCT.

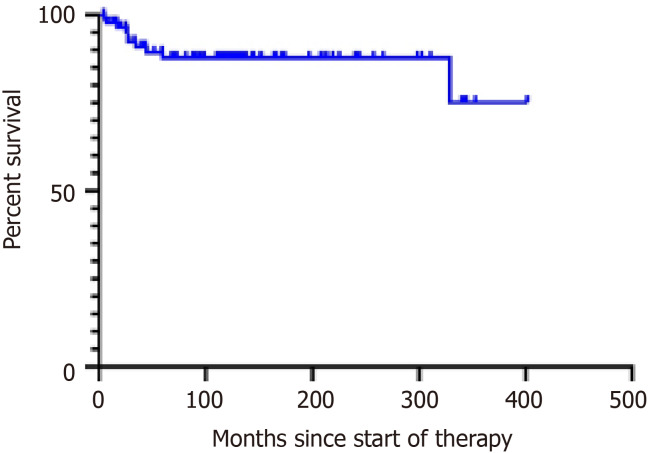

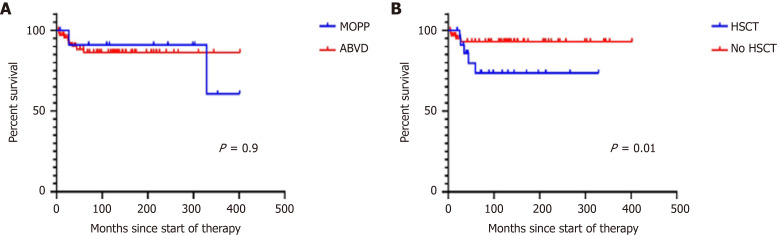

Responses

Patients were followed for a median of 114 mo (range: 4-402). Forty-four are alive, ten have died, and 34 were lost to follow-up. Median OS for all patients has not been reached, and is more than 402 mo. OS was 88% 310 mo and 77% 402 mo (Figure 1). Median OS has not been reached and is 94 mo for stage I, 109 mo for stage II, 90 mo for stage III, and 98 for stage IV (P = 0.2). The 310-mo OS was 83% for patients treated with MOPP and 88% for those treated with ABVD [hazard ratio (HR): 0.76, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.2-2.8, P = 0.6; Figure 2]. Sixteen patients (18%) were refractory to treatment and nine (10%) relapsed. They were treated with ICE followed by HSCT, autologous in 15 patients and allogeneic in ten patients. Patients who underwent autologous HSCT had a median survival of 329 mo and an OS of 92%. Those given allogeneic HSCT had a median survival of 59 mo and an OS of 46% (HR: 0.2, 95%CI: 0.04–1.3, P = 0.057). The OS of patients given and HSCT was 73% at 266 mo and was 93% at 404 mo in those not given HSCT (HR: 4.09, 95%CI: 1.0–16.6, P = 0.01) (Figure 2B). The OS was similar (Figure 2). The causes of death were breast carcinoma in two cases, liver carcinoma in one, and uncontrolled lymphoma activity in the remaining patients.

Figure 1.

Overall survival of 88 patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Figure 2.

Overall survival of 88 patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma treated with either MOPP or ABVD (A) and treated either with or without hematopoietic stem cell transplants (B). ABVD: adriamycin bleomycin vinblastine and dacarbazine; HSCT: Hematopoietic stem cell transplant; MOPP: mechlorethamine, Oncovin, procarbazine, and prednisone.

Long-term toxicity

Twelve patients developed peripheral neuropathy. There were no reported cases of pulmonary, fertility, or cardiovascular toxicity. Five patients developed a secondary neoplasia 18-150 mo after completing treatment; four had received chemotherapy (three ABVD and one MOPP); one had received radiotherapy alone. The salient features of the patients are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Salient features of patients who developed a secondary malignancy after the treatment of lymphoma

|

Neoplasm

|

Age

|

Sex

|

Type

|

Stage

|

Treatment

|

HSCT

|

Time1, mo

|

|

| 1 | Tongue epidermoid carcinoma | 32 | M | Nodular sclerosing | I | Radiotherapy | No | 58 |

| 2 | Liver adenocarcinoma | 22 | F | Nodularsclerosing | III | MOPP | No | 97 |

| 3 | Breast cancer | 38 | F | Mixed cellularity | III | ABVD | No | 150 |

| 4 | NK/T-cell lymphoma | 15 | M | Nodular sclerosing | IV | ABVD | Autologous | 18 |

| 5 | Breast cancer | 23 | F | Nodular sclerosing | III | AVBD | Autologous | 59 |

Time in months elapsed between the diagnosis of Hodgkin’s lymphoma and the diagnosis of the secondary neoplasia.

HSCT: Hematopoietic stem cell transplant; M: Male; F: Female.

DISCUSSION

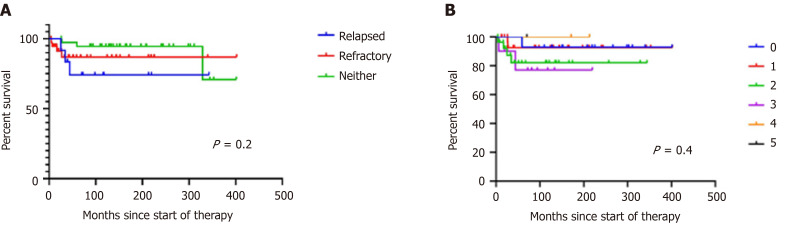

The outcomes of HL in México have not been fully analyzed or reported. We have previously shown that some malignancies in México have different behaviors in the population of Mexican mestizos compared with other populations. For example, multiple myeloma in México is less frequent[12,13] and less aggressive than in Caucasians or African-Americans[12], and chronic lymphocytic leukemia is also less frequent and less aggressive in Mexican mestizos than in other populations[14-16], but promyelocytic leukemia is substantially more frequent in México than in Caucasian populations[14,17]. In the case of HL in México, there is not enough information about its prevalence and clinical behavior. Preliminary data indicate that the prevalence of HL in México is similar to that reported in other populations[17,18]. The data presented here suggest that the clinical picture of the disease may be less aggressive in México, as without employing novel and sophisticated drugs, the OS of this group of patients was 88% at 310 mo, including all stages of the disease, relapsed, and refractory patients (Figure 1). There were no significant differences between patients treated with MOPP or ABVD. The OS of relapsed or refractory patients who were given an HSCT was significantly lower than those who did not require it (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Overall survival of 88 patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma with or without relapsed or refractory disease (A), and overall survival of the patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma classified as described by Diefenbach et al (B).

Radiation therapy is included in treatment strategies. We have previously suggested that in México, and probably in other underprivileged circumstances where RT facilities are suboptimal, patients with early stages of HL should be treated with ChT alone. The message being “conventional ChT is better than a poor RT”[19,21-24]. The results that we present here support the previous observations. Additionally, patients with relapsed/refractory disease were successfully rescued with ICE followed by HSCT. Figure 3 shows the OS of the patients classified by the prognostic score described by Hayden et al[24].

The main observations of treatment which we present here are (1) ABVD was offered to all patients regardless of their clinical stage. (2) Four cycles were administered to patients with stages I and II and six cycles to those with stages III and IV. (3) Two additional cycles were given to all patients after a negative CT scan after receiving 4-6 cycles. (4) No interim FDG-PET scans were done, reserving them for the end of treatment. And (5) Relapsed or refractory patients were given ICE followed by an HSCT. The limitations of this study include a relatively small and heterogeneous sample, the potential of referral bias, a high proportion of patients lost to follow-up, and socioeconomic factors.

This simplified approach to the treatment of patients with HL demonstrates adequate results with an OS of 88% at 26 years regardless of the clinical stage or relapsed/refractory disease. Additional data are needed to confirm the observations, which may be useful in circumstances of a restrained economy. The use of novel and expensive drugs such as pembrolizumab, nivolumab, panabinostat, idelalisib, mocetinostat, brentuximab vedotin and others[4,24] should be reserved for multi-relapsed cases and does not appear to be essential as frontline therapy.

CONCLUSION

HL may be less aggressive in the Mexican than in Caucasian populations. Combined chemotherapy without radiotherapy achieves acceptable results. In our context with healthcare limited-resources, chemotherapy alone with ABVD continues to be the treatment of choice in patients with HL.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Hodgkin´s lymphoma (HL) can be treated with different alternatives, the performance of newer and older chemotherapy schemes are unknown in some circumstances.

Research motivation

The motivation was to describe the performance of treatment of HL in a middle-income country.

Research objectives

The objective was to determine performance of classic therapies for HL.

Research methods

This was a comparative study of therapies for HL in a single center over a long-term period.

Research results

HL may be less aggressive in the Mexican population. In addition, the classical ABVD regimen achieved long-term survival in a significant proportion of patients.

Research conclusions

Combined chemotherapy has acceptable efficacy in patients with HL. Our results suggest that classical treatment schemes continue to be an effective alternative. More studies should be conducted.

Research perspectives

Classic therapies for HL may still be preferable over novel therapies in middle-income countries. The use of ABVD combined with other immunomodulatory agents could be a potential solution for patients not experiencing favorable outcomes.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: This study was approved by the Centro de Hematología y Medicina Interna, Clínica Ruiz Institutional Review Board.

Informed consent statement: Informed consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no conflicting interests.

STROBE statement: The authors have read the STROBE Statement, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the STROBE Statement.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Peer-review started: January 4, 2021

First decision: May 4, 2021

Article in press: August 9, 2021

Specialty type: Hematology

Country/Territory of origin: Mexico

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Dou AX S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Xing YX

Contributor Information

Luisa Fernanda Sánchez-Valledor, Escuela de Medicina, Universidad de las Américas Puebla, Cholula 72810, Puebla, Mexico.

Thomas M Habermann, Department of Medicine, Division of Hematology, Mayo Clinical and Mayo Foundation, Rochester, MN 55905, United States.

Iván Murrieta-Alvarez, Centro de Hematología y Medicina Interna, Clínica Ruiz, Puebla 72530, Mexico.

Alejandra Carmina Córdova-Ramírez, Escuela de Medicina, Universidad Popular Autónoma del Estado de Puebla, Puebla 72410, Mexico.

Montserrat Rivera-Álvarez, Escuela de Medicina, Universidad Popular Autónoma del Estado de Puebla, Puebla 72410, Mexico.

Andrés León-Peña, Centro de Hematología y Medicina Interna, Clínica Ruiz, Puebla 72530, Mexico.

Yahveth Cantero-Fortiz, Centro de Hematología y Medicina Interna, Clínica Ruiz, Puebla 72530, Mexico.

Juan Carlos Olivares-Gazca, Centro de Hematología y Medicina Interna, Clínica Ruiz, Puebla 72530, Mexico.

Guillermo José Ruiz-Delgado, Centro de Hematología y Medicina Interna, Clínica Ruiz, Puebla 72530, Mexico.

Guillermo José Ruiz-Argüelles, Centro de Hematología y Medicina Interna, Clínica Ruiz, Puebla 72530, Mexico. gruiz1@hsctmexico.com.

Data sharing statement

Data are available upon request.

References

- 1.Sehn LH. Introduction to a review series on Hodgkin lymphoma: change is here. Blood. 2018;131:1629–1630. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-02-824045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trendowski M, Fondy TP. Targeting the plasma membrane of neoplastic cells through alkylation: a novel approach to cancer chemotherapy. Invest New Drugs. 2015;33:992–1001. doi: 10.1007/s10637-015-0263-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Advani RH, Hong F, Fisher RI, Bartlett NL, Robinson KS, Gascoyne RD, Wagner H Jr, Stiff PJ, Cheson BD, Stewart DA, Gordon LI, Kahl BS, Friedberg JW, Blum KA, Habermann TM, Tuscano JM, Hoppe RT, Horning SJ. Randomized Phase III Trial Comparing ABVD Plus Radiotherapy With the Stanford V Regimen in Patients With Stages I or II Locally Extensive, Bulky Mediastinal Hodgkin Lymphoma: A Subset Analysis of the North American Intergroup E2496 Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1936–1942. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.8138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis C, Naci H, Gurpinar E, Poplavska E, Pinto A, Aggarwal A. Availability of evidence of benefits on overall survival and quality of life of cancer drugs approved by European Medicines Agency: retrospective cohort study of drug approvals 2009-13. BMJ. 2017;359:j4530. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ansell SM. Hodgkin lymphoma: 2016 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:434–442. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aguado-Vázquez TM, Olivas-Martínez A, Cancino-Ramos U, Zúñiga-Tamayo DA, Lome-Maldonado MDCA, Rivas-Vera S, García-Pérez FO, Candelaria-Hernández MG. 18f-Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography Versus Bone Marrow Biopsy for the Evaluation of Bone Marrow Infiltration in Newly Diagnosed Lymphoma Patients. Rev Invest Clin. 2020;73 doi: 10.24875/RIC.20000239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilad Y, Gellerman G, Lonard DM, O'Malley BW. Drug Combination in Cancer Treatment-From Cocktails to Conjugated Combinations. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13 doi: 10.3390/cancers13040669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tarnasky AM, Troy JD, LeBlanc TW. The patient experience of ABVD treatment in Hodgkin lymphoma: a retrospective cohort study of patient-reported distress. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29:4987–4996. doi: 10.1007/s00520-021-06044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mi M, Zhang C, Liu Z, Wang Y, Li J, Zhang L. Gemcitabine, cisplatin, and dexamethasone and ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide regimens have similar efficacy as salvage treatment for relapsed/refractory aggressive lymphoma: A retrospectively comparative study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99:e23412. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000023412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang J, Duan X, Yang L, Liu X, Hao C, Dong H, Gu H, Tang H, Dong B, Zhang T, Gao G, Liang R. Comparison of Survival Between Autologous and Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation in Patients with Relapsed or Refractory B-Cell Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma: A Meta-Analysis. Cell Transplant. 2020;29:963689720975397. doi: 10.1177/0963689720975397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goel MK, Khanna P, Kishore J. Understanding survival analysis: Kaplan-Meier estimate. Int J Ayurveda Res. 2010;1:274–278. doi: 10.4103/0974-7788.76794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tietsche de Moraes Hungria V, Chiattone C, Pavlovsky M, Abenoza LM, Agreda GP, Armenta J, Arrais C, Avendaño Flores O, Barroso F, Basquiera AL, Cao C, Cugliari MS, Enrico A, Foggliatto LM, Galvez KM, Gomez D, Gomez A, de Iracema D, Farias D, Lopez L, Mantilla WA, Martínez D, Mela MJ, Miguel CE, Ovilla R, Palmer L, Pavlovsky C, Ramos C, Remaggi G, Santucci R, Schusterschitz S, Sossa CL, Tuna-Aguilar E, Vela J, Santos T, de la Mora O, Machnicki G, Fernandez M, Barreyro P. Epidemiology of Hematologic Malignancies in Real-World Settings: Findings From the Hemato-Oncology Latin America Observational Registry Study. J Glob Oncol. 2019;5:1–19. doi: 10.1200/JGO.19.00025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murrieta-Álvarez I, Steensma DP, Olivares-Gazca JC, Olivares-Gazca M, León-Peña A, Cantero-Fortiz Y, García-Navarrete YI, Cruz-Mora A, Ruiz-Argüelles A, Ruiz-Delgado GJ, Ruiz-Argüelles GJ. Treatment of Persons with Multiple Myeloma in Underprivileged Circumstances: Real-World Data from a Single Institution. Acta Haematol. 2020;143:552–558. doi: 10.1159/000505606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chiattone C, Gomez-Almaguer D, Pavlovsky C, Tuna-Aguilar EJ, Basquiera AL, Palmer L, de Farias DLC, da Silva Araujo SS, Galvez-Cardenas KM, Gomez Diaz A, Lin JH, Chen YW, Machnicki G, Mahler M, Parisi L, Barreyro P. Real-world analysis of treatment patterns and clinical outcomes in patients with newly diagnosed chronic lymphocytic leukemia from seven Latin American countries. Hematology. 2020;25:366–371. doi: 10.1080/16078454.2020.1833504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruiz-Argüelles GJ. Advances in the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic leukemia in Mexico. Salud Publica Mex. 2016;58:291–295. doi: 10.21149/spm.v58i2.7799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cruz-Mora A, Murrieta-Alvarez I, Olivares-Gazca JC, León-Peña A, Cantero-Fortiz Y, García-Navarrete YI, Sánchez-Valledor LF, Khalaf D, Ruiz-Delgado GJ, Ruiz-Argüelles GJ. Up to half of patients diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukemia in México may not require treatment. Hematology. 2020;25:156–159. doi: 10.1080/16078454.2020.1749473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Colunga-Pedraza PR, Gomez-Cruz GB, Colunga-Pedraza JE, Ruiz-Argüelles GJ. Geographic Hematology: Some Observations in Mexico. Acta Haematol. 2018;140:114–120. doi: 10.1159/000491989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carballo-Zarate A, Garcia-Horton A, Palma-Berre L, Ramos-Salazar P, Sanchez-Verin-Lucio R, Valenzuela-Tamariz J, Molinar-Horcasitas L, Lazo-Langner A, Zarate-Osorno A. Distribution of lymphomas in Mexico: A multicenter descriptive study. J Hematopathol. 2018;11:99–105. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bates JE, Parikh RR, Mendenhall NP, Morris CG, Hoppe RT, Constine LS, Hoppe BS. Long-Term Outcomes in 10-Year Survivors of Early-Stage Hodgkin Lymphoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020;107:522–529. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.02.642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mou E, Advani RH, von Eyben R, Rosenberg SA, Hoppe RT. Long-Term Outcomes of Patients With Early Stage Nonbulky Hodgkin Lymphoma Treated With Combined Modality Therapy in the Stanford V Trials (the G4 and G5 Studies) Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2021;110:444–451. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jaime-Pérez JC, Gamboa-Alonso CM, Padilla-Medina JR, Jiménez-Castillo RA, Olguín-Ramírez LA, Gutiérrez-Aguirre CH, Cantú-Rodríguez OG, Gómez-Almaguer D. High frequency of primary refractory disease and low progression-free survival rate of Hodgkin's lymphoma: a decade of experience in a Latin American center. Rev Bras Hematol Hemoter. 2017;39:325–330. doi: 10.1016/j.bjhh.2017.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Momotow J, Borchmann S, Eichenauer DA, Engert A, Sasse S. Hodgkin Lymphoma-Review on Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, Current and Future Treatment Approaches for Adult Patients. J Clin Med. 2021;10 doi: 10.3390/jcm10051125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson P, Federico M, Kirkwood A, Fosså A, Berkahn L, Carella A, d'Amore F, Enblad G, Franceschetto A, Fulham M, Luminari S, O'Doherty M, Patrick P, Roberts T, Sidra G, Stevens L, Smith P, Trotman J, Viney Z, Radford J, Barrington S. Adapted Treatment Guided by Interim PET-CT Scan in Advanced Hodgkin's Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2419–2429. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayden AR, Lee DG, Villa D, Gerrie AS, Scott DW, Slack GW, Sehn LH, Connors JM, Savage KJ. Validation of a simplified international prognostic score (IPS-3) in patients with advanced-stage classic Hodgkin lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2020;189:122–127. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request.