Highlights

-

•

A strain of Pseudoxanthomonas indica was used in this study.

-

•

Optimal fermentation conditions of P. indica H32 was found for first time.

-

•

DCW of P. indica H32 was increased 1.36 after optimizing with respect to the non-optimized conditions.

Keywords: Bioproducts, Fermentation conditions, Optimization, Pseudoxanthomonas indica, Response surface methodology (RMS)

Abstract

Pseudoxanthomonas indica H32, constitutes the active component of a promising bioproduct candidate with biopesticide and biofertilizing activities. However, suitable fermentation conditions should be established to manufacture this product. Accordingly, the aim of this study was to optimize the fermentation conditions of bacterium Pseudoxanthomonas indica H32 in a 3 L bioreactor. The relevant parameters for strain growth, temperature (25–40 °C) and pH (6–9), were optimized using the response surface methodology (RSM). Additionally, the influence of air flow (0.5–1.5 vvm) and impeller stirrer speed (4.17–14.17 s − 1) in the volumetric oxygen transfer coefficient (KLa) were evaluated and then, in the P. indica H32 growth. The response variables were dry cell weight (DCW) and specific growth rate (µ). The results showed that P. indica H32 growth was significantly affected by the culture medium pH (p < 0.005). The optimum pH and temperature values were found at 7.4 and 34 °C, respectively. The conditions that increased KLa, were 12.17 s − 1 and 1.5 vvm, with a KLa value of 0.104 s − 1. This conditions ensured optimum strain growth of 5.496 g/L of DCW (5.E1010 CFU/mL), whereas µ was 0.403 h − 1. The findings of this study are a step forward in the development of P. indica H32 as biopesticide and biofertilizer.

1. Introduction

Generally, conventional chemical pesticides used in agriculture for pest management and control are harmful to human health and the environment [1, 6, 11, 12]. As bioproducts have become efficient and environmentally-friendly alternatives, global efforts are increasingly being made to eliminate chemicals or, at least, limit their application, [12]. HeberNem®, whose active principle is bacterium Brevibacterium celere C924, is one of the bioproducts currently used in Cuba to control nematodes and promote growth. Additionally, a new promising bioproduct candidate based on bacterium Pseudoxanthomonas indica H32 is being developed. In previous unpublished studies, P. indica H32 demonstrated high effectiveness to control nematodes and phytoparasitic fungi, as well as a capacity to promote plant growth [15]. Besides, viable cells of P. indica H32 have shown comparable effects when used in the same concentration as Brevibacterium celere C924. Previous studies in Erlenmeyer flasks have shown that bacterium P. indica H32 has a high specific growth rate [17]. This feature could contribute to reductions in manufacturing costs, since it can favor higher productivity and shorter fermentation time. However, implementing production depends on the design of the major stages of the process.

Recently, a culture medium was designed for optimal growth of the bacterium Pseudoxanthomonas indica H32 allowing its production as biopesticide and biofertilizer [17]. The outcome of these studies meant a significant step forward in the development of this new bioproduct candidate. Nevertheless, the fermentation conditions must be further studied, since fermentation accounts for 25–40% of manufacturing investments in biotechnological production using living organisms [16]. Because of the high economic impact, the obtaining of optimum fermentation conditions, particularly those related to the physical and chemical parameters, is a major step in the design of biological processes [9]. Oxygen transference capacity is an important parameter; different variables, such as shaking speed and aeration, and the rheological and physico-chemical properties of the medium have a significant influence on the volumetric oxygen transfer coefficient (KLa). It is an essential parameter for process design and scale-up [13]. The dynamic method is one of the most commonly used techniques to determine KLa [8, 10].

Furthermore, quite a few methods of statistical experimental design have been implemented to optimize processes. Among them, the response surface methodology (RSM) is one of the most suitable procedures to determine the effect of independent variables. It is also used to conduct efficient searches of optimum conditions for a multivariable system [3].

Therefore, the aim of this study is to establish the optimum fermentation conditions of bacterium Pseudoxanthomonas indica H32 in 3 L bioreactors, through RSM.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Bacterial strain

Bacterium Pseudoxanthomonas indica, strain H32 (Culture Collection of Microorganisms, Center of Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (CCCIEB), Cuba, 771) stored at −70 °C in 20% (v/v) glycerol was used in this study.

2.2. Culture medium

Tryptone soy agar (Conda-Pronadisa, Spain) was used for plate culturing. Medium H [17], containing 10 g/L of sucrose, 5 g/L of yeast extract, and 100 mL/L of phosphate solution (47.8 g/L Na2HPO4 and 30 g/L KH2PO4, adjusted to pH 7.2 by addition of NaOH) was utilized for culturing in Erlenmeyer flasks. Also, the medium H was employed for the fermentation with 1 mL/L Glanapon (Bussetty, Austria) to control foaming.

2.3. Culture conditions

Plate culture: some culture stored at −70 °C in 20% (v/v) glycerol was streaked on the plate using a standard inoculation loop. It was incubated at 37 °C, for 48 h.

Culture in 250 mL Erlenmeyer flasks: a colony isolated from the plate culture was inoculated into 30 mL of the culture medium. Then it was incubated at 37 °C and 250 rpm, in thermostat shaker (New Brunswick G 25, USA), during 18–20 h. Optical density (OD) was determined at the end of the culture, before inoculating into 1 L Erlenmeyer flasks.

Culture in 1 L Erlenmeyer flasks: based on the Volumetric Analysis, from the OD of the culture in 250 mL Erlenmeyer flasks, the volume required for inoculating 300 mL of the medium (in 1 L Erlenmeyer flasks) was calculated at an initial OD of 0.1. It was incubated at 37 °C and 250 rpm, in thermostat shaker (New Brunswick G 25, USA), during 18–20 h.

Fermentation: it was made in 3 L bioreactors (Marubishi, Japan). The amounts of culture medium components were calculated for 3 L, but the final volume of the medium was adjusted to 2.7 L. To start fermentation, 300 mL of the culture in 1 L Erlenmeyer flasks were used as inoculum . The temperature, pH, shaking speed, and air flow were controlled according to the experimental designs. Fermentation time was set to 30 h, based on the results of previous studies done at an Erlenmeyer flasks scale [17]. The growth kinetics of P. indica H32 was determined during that period by quantifying dry cell weight (DCW) and specific growth rate (µ), every two hours. Moreover, the colony forming units per milliliter (CFU/mL) were determined at the 24 h.

2.4. Experimental designs

RSM was performed to determine the optimum fermentation conditions for P. indica H32. In the first experiment, a 32 factorial design was used to study the combined effect of the main parameters affecting growth [low, mid, high]: temperature in °C (25, 32.5, 40), and the pH (6, 7, 8), whereas the air flow (Qg/V), and impellent stirrer speed (Ni) were constant: 1.5 vvm and 4.17 s − 1, respectively. Furthermore, other points were added to strengthen the experimental design data, three of them with pH 9. The response variables were DCW and µ. In the second experiment, a design created by the researcher was used to study the influence of aeration [low, mid, high level] in vvm (0.5, 1, 1.5), and impellent stirrer speed [categorically], in s − 1 (4.17, 5.83, 7.50, 9.17, 10.83, 12.50, 14.17) on KLa. Temperature and pH were adjusted to the optimum values determined in the first experiment. KLa was determined through the dynamic method [8]. Dissolved oxygen (DO) was measured using a Mettler Toledo InPro 6000 polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) membrane. Then, the optimum conditions of oxygen transference were evaluated according to P. indica H32 growth, in order to check if the amount of oxygen supplied to the system could meet the requirements of P. indica H32.

Design-Expert 11.1.2 was used to build the experimental designs, ANOVA of the experimental results (α = 0.05), regression analysis, goodness of fit evaluation, determination of precision equation of the model predicted, determination of R2, adjusted R2 and predicted R2, for the optimization, and confirmation of the predicted optimum of response variables with 95% confidence.

2.5. Numerical optimization and validation of optimum conditions predicted

Numerical optimization was based on models to determine the optimum combination of the parameters in the process, which allow for maximum DCW, µ and KLa. Three fermentations were made to validate the optimum value predicted in the first experiment. The validation of the optimum value predicted in the second experiment required three repetitions, in all of which KLa was determined. At the end of the experiments, three fermentations were performed using the general optimum fermentation conditions determined for P. indica H32. Growth was monitored as described in item 2.3, and DO was quantified in the medium during the fermentation, by sensor measurement.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Optimization of fermentation conditions of P. indica H32 in 3 L bioreactors

Optimum fermentation conditions of P. indica H32 for their production as biopesticide and biofertilizer are required; however, these conditions have not been found in the literature to present. The pH of the medium is one of the most important environmental factors causing a marked effect on the activity of enzymes that catalyze metabolic reactions. Likewise, the pH has a significant influence on complex physiological phenomena, such as membrane permeability and cell morphology. Furthermore, production and growth of bioactive metabolites are influenced by temperature [5]. Studies in Erlenmeyer flasks demonstrated that the bacterium grow satisfactorily at 37 °C, pH 7.2 [17]. Therefore, to study the combined effect of temperature and pH on P. indica H32 growth in 3 L bioreactors, the levels of the experimental factors were fixed taking into account the results from Erlenmeyer flasks studies, and the reports made by Thierry et al. [19], Kumari et al. [14] and Nayaka et al. [18]. Furthermore, if the optimum conditions of oxygen transference into a bioreactor are determined, the microorganism can grow without inhibition by absence of oxygen, and therefore, satisfactory growth can be achieved in the conditions used during the fermentation. The study of the effects of aeration and shaking on KLa is critical in this respect [13]. The design points and the experimental results of this study are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Experimental design with the corresponding values observed by studying the combined effect of temperature (T) and the pH on P. indica H32 growth.

| Design points | Experimental factors | Responses | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T (°C) | pH | DCW (g/L) | µ (h−1) | |

| 1 | 25 | 7 | 2.918 | 0.064 |

| 2 | 32.5 | 8 | 5.232 | 0.466 |

| 3 | 25 | 8 | 5.736 | 0.172 |

| 4 | 25 | 6 | 1.012 | 0.060 |

| 5 | 32.5 | 6 | 2.878 | 0.074 |

| 6 | 32.5 | 7 | 5.467 | 0.194 |

| 7 | 40 | 6 | 2.278 | 0.115 |

| 8 | 25 | 9 | 0 | 0.000 |

| 9 | 33 | 8 | 5.105 | 0.445 |

| 10 | 40 | 7 | 4.472 | 0.320 |

| 11 | 25 | 9 | 0 | 0.000 |

| 12 | 40 | 8 | 6.075 | 0.158 |

| 13 | 25 | 9 | 0 | 0.000 |

| 14 | 32.5 | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| 15 | 40 | 9 | 0 | 0.000 |

| 16 | 33 | 8 | 4.169 | 0.478 |

| 17 | 33 | 8 | 5.323 | 0.470 |

Table 2.

Experimental design with the corresponding values observed when studying the influence of air flow per volume unit (Qg/V), and impeller stirrer speed (Ni) on KLa.

| Design points | Experimental factors | Response | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qg/V (vvm) | Ni (s − 1) | KLa (s − 1) | |

| 1 | 0.5 | 7.5 | 0.0592 |

| 2 | 1.5 | 14.17 | 0.1240 |

| 3 | 1 | 4.17 | 0.0263 |

| 4 | 1 | 7.5 | 0.0661 |

| 5 | 0.5 | 5.83 | 0.0430 |

| 6 | 1.5 | 14.17 | 0.0811 |

| 7 | 0.5 | 10.83 | 0.0657 |

| 8 | 1.5 | 10.83 | 0.0976 |

| 9 | 1.5 | 12.5 | 0.0984 |

| 10 | 0.5 | 14.17 | 0.0380 |

| 11 | 1 | 7.5 | 0.0694 |

| 12 | 1 | 9.17 | 0.1036 |

| 13 | 1 | 10.83 | 0.0667 |

| 14 | 1.5 | 4.17 | 0.0287 |

| 15 | 1 | 5.83 | 0.0562 |

| 16 | 1 | 5.83 | 0.0472 |

| 17 | 0.5 | 12.5 | 0.0438 |

| 18 | 1 | 12.5 | 0.0880 |

| 19 | 1.5 | 9.17 | 0.0859 |

| 20 | 0.5 | 14.17 | 0.0351 |

| 21 | 1.5 | 5.83 | 0.0606 |

| 22 | 0.5 | 9.17 | 0.0682 |

| 23 | 1 | 4.17 | 0.0288 |

| 24 | 0.5 | 4.17 | 0.0170 |

| 25 | 1 | 7.5 | 0.0615 |

3.1.1. Combined effect of temperature and pH

The first results observed in the study of the combined effect of temperature and pH on P. indica H32 growth evidenced maximum strain growth in the temperature range studied, but not in the pH range studied (Fig. 1a and 1b) where growth tended to increase with the high pH level. Hence, it was necessary to broaden the design space to pH 9. However, P. indica H32 growth was insignificant with this pH value, and the culture medium became translucid in the course of fermentation time, probably due to the occurrence of cell lysis, according to Bundale et al. [5]. Upon broadening the design space, response surface analysis (Fig. 1c and 1d) showed a maximum increase between 32 and 37 °C, with pH 7.3–7.7, approximately. The experimental results were adjusted to a quadratic model for the response variables DCW (R2 = 0.8964, adjusted R2 = 0.8493 and predicted R2 = 0.7558), and µ (R2 = 0.7540, adjusted R2 = 0.6422 and predicted R2 = 0.2846). ANOVAs of response variables DCW and µ are shown in Tables 3 and 4. The P values of the models were 0.0001 and 0.0042, respectively, indicating that the models can be used to describe the behavior of both response variables (95% confidence). The significance of each parameter coefficient was determined by the P value. Regarding DCW, only the pH, and the quadratic effect of pH (P= 0.0011 and P < 0.0001, respectively) had a significant influence. A similar behavior was observed in µ (P= 0.0188 and P= 0.0021, respectively), in which the quadratic effect of temperature (T2) was too significant (P= 0.0340).

Fig. 1.

Responses surface graphic of P. indica H32 DCW and µ, as to temperature (T) and pH factors. a, b P. indica H32 DCW and µ values achieved from the initial experimental design, up to pH 8; c, d P. indica H32 DCW and µ values and predicted optimal, obtained after broadening the design space to pH 9. The flags indicate the optimum DCW and µ predicted values by the models. Red points indicate the design points above the model. Pink points indicate the design points below the model.

Table 3.

ANOVA of the Quadratic model for response 1: DCW.

| Source | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F-value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 81.45 | 5 | 16.29 | 19.03 | < 0.0001 |

| A-T | 1.84 | 1 | 1.84 | 2.15 | 0.1702 |

| B-pH | 16.22 | 1 | 16.22 | 18.95 | 0.0011 |

| AB | 0.6922 | 1 | 0.6922 | 0.8086 | 0.3878 |

| A² | 0.8749 | 1 | 0.8749 | 1.02 | 0.3338 |

| B² | 55.85 | 1 | 55.85 | 65.25 | < 0.0001 |

| Residual | 9.42 | 11 | 0.8561 | ||

| Lack of Fit | 8.66 | 7 | 1.24 | 6.58 | 0.0439 |

| Pure Error | 0.7523 | 4 | 0.1881 | ||

| Cor Total | 90.87 | 16 | |||

| R2 | 0.8964 | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.8493 | ||||

| Predicted R2 | 0.7558 |

Table 4.

ANOVA of the quadratic model for response 2: µ.

| Source | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F-value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 0.4150 | 5 | 0.0830 | 6.74 | 0.0042 |

| A-T | 0.0161 | 1 | 0.0161 | 1.31 | 0.2770 |

| B-pH | 0.0933 | 1 | 0.0933 | 7.58 | 0.0188 |

| AB | 0.0072 | 1 | 0.0072 | 0.5808 | 0.4620 |

| A² | 0.0721 | 1 | 0.0721 | 5.86 | 0.0340 |

| B² | 0.1968 | 1 | 0.1968 | 15.98 | 0.0021 |

| Residual | 0.1354 | 11 | 0.0123 | ||

| Lack of Fit | 0.1348 | 7 | 0.0193 | 130.00 | 0.0001 |

| Pure Error | 0.0006 | 4 | 0.0001 | ||

| Cor Total | 0.5505 | 16 | |||

| R2 | 0.7540 | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.6422 | ||||

| Predicted R2 | 0.2846 |

The models equations obtained can be used to make predictions about the response for given levels of each factor in terms of actual factors:

3.1.2. Influence of aeration and impeller stirrer speed on KLa

This study showed that KLa increased directly proportional to air flow (Qg/V). Similar results were reported by Aroniada et al. [2] and Bun et al. [4]. Furthermore, an increase in Ni content below the typical operation conditions of fermentation improves the KLa value [8, 20], as shown in Fig. 2. However, KLa underwent a slight decrease from 12.17 s − 1 (730 rpm). Similar results were found by Doi et al. [7]. They reported that the KLa in a bioreactor is dependent on the size of the bubble from the sparger, residence time of the bubble, molecular weight of the species of interest and sparging volume. According to raise by Doi et al. [7], when the shaking speed was higher than 12.17 s − 1, probably due to an increase of gas solubility in the liquid, a rupturing tendency of the gas bubbles was existed, which brought about a reduction in the residence time of the bubble in the medium, and consequently, a reduction of the KLa value.

Fig. 2.

Response surface graphic of KLa, as to air flow (Qg/V) and impeller stirrer speed (Ni). The flag indicates the optimum value of KLa predicted by the model. Red points indicate the design points above the model. Pink points indicate the design points below the model.

The experimental results were fit to a quadratic model (R2 = 0.8693, adjusted R2 = 0.8349, and predicted R2 = 0.7526. The ANOVA of KLa is shown in Table 5. The P value of the model was < 0.0001, indicated high significance (95% confidence). Besides, all the coefficients of the equation to determine KLa were significant (P≤ 0.05), except the quadratic effect of Qg/V (P= 0.5413). The model equation obtained can be used to make predictions about the response for given levels of each factor in terms of actual factors (Qg/V and Ni):

Table 5.

ANOVA for the quadratic model of response: KLa.

| Source | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F-value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 0.0154 | 5 | 0.0031 | 25.27 | < 0.0001 |

| A-Qg/V | 0.0036 | 1 | 0.0036 | 29.72 | < 0.0001 |

| B-Ni | 0.0049 | 1 | 0.0049 | 39.87 | < 0.0001 |

| AB | 0.0016 | 1 | 0.0016 | 12.94 | 0.0019 |

| A² | 0.0000 | 1 | 0.0000 | 0.3870 | 0.5413 |

| B² | 0.0035 | 1 | 0.0035 | 28.88 | < 0.0001 |

| Residual | 0.0023 | 19 | 0.0001 | ||

| Lack of Fit | 0.0013 | 13 | 0.0001 | 0.6059 | 0.7892 |

| Pure Error | 0.0010 | 6 | 0.0002 | ||

| Cor Total | 0.0177 | 24 | |||

| R2 | 0.8693 | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.8349 | ||||

| Predicted R2 | 0.7526 |

3.1.3. Numerical optimization and experimental validation

The objective function of the numerical optimization on the first experiment was maximize DCW and µ, keeping the temperature and pH of the medium within the limits studied. The optimum temperature and pH values for the fermentation of P. indica H32 were 33.97 °C and 7.40, respectively. In these conditions, the predicted responses were 5.823 g/L DCW, and 0.401 h − 1 µ (Fig. 1c and 1d). Thierry et al. [19] refer that most species of this genus are mesophiles, with optimum temperatures of 30–37 °C, and optimum pH 7–8, preferably around 8. The optimum fermentation conditions found for P. indica H32 coincide with the findings of Thierry et al. [19]. However, they differ from the observations of Nayaka et al. [18], which may have been caused by the fact that isolated Pseudoxanthomonas indica strains have specific characteristics that make them different. The experimental DCW and µ means were 5.496 g/L and 0.403 h − 1, respectively. P. indica H32 DCW improved 1.36-fold following optimization of fermentation conditions, compared to the non-optimized conditions. At the 24 h, DCW obtained during evaluation was equivalent to 5.E1010 CFU/mL (VC < 5%).

In the second experiment, the objective was to maximize KLa, keeping Qg/V and Ni within the values studied. The optimum conditions that permitted greater oxygen transference in the system studied (81.00% desirability) were determined at 1.5 vvm and 12.17 s − 1, for a KLa of 0.104 s − 1 (Fig. 2). However, the physical characteristics of the fermentation system did not favor an increase of air flow above the range studied; hence, these conditions might vary in other systems, since KLa increase is proportional to air flow increase. The results of this experiment were similar to the ones achieved by González et al. [10].

Table 6 shows the optimum values predicted, and the values observed in the response variables of the two experiments with n= 3. The mean of the experimental values was found between the limits of the intervals predicted (95% confidence), which demonstrated the reliability of the results using RSM.

Table 6.

Experimental validation of the optimum value predicted by the models as to DCW, µ and KLa responses.

| Response | Predicted Mean | Standard deviation | n | 95% low PI | Data Mean | 95% high PI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

DCW (g/L) µ (h − 1) |

5.823 0.401 |

0.925 0.111 |

3 3 |

4.480 0.240 |

5.496 0.403 |

7.166 0.562 |

| KLa (1/s) | 0.104 | 0.011 | 3 | 0.087 | 0.104 | 0.120 |

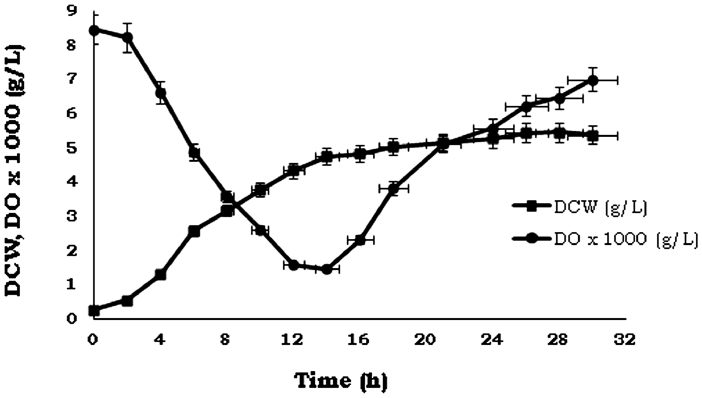

Finally, in the experimental validation of the global optimum conditions, the parameters were set at T= 34 °C, pH 7.4, Qg/V= 1.5 vvm, and Ni = 12.17 s − 1. Thus, it was check that the growth of P. indica H32 it was not limited by the absence of oxygen during the fermentation after optimization (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Growth kinetics and oxygen uptake of bacterium P. indica H32 in 3 L bioreactors under optimized culturing conditions.

4. Conclusions

The determination of optimum conditions for the fermentation of P. indica H32 in 3 L bioreactors using RSM was a significant step forward in the development of a technology for the production of a new bioproduct candidate with biopesticidal and biofertilizing activities, as an alternative to conventional chemical pesticides. The optimum fermentation conditions for P. indica H32 found in 3 L bioreactors were T = 34 °C, pH = 7.4, Ni = 12.17 s − 1, and Qg/V = 1.5 vvm. These conditions contributed to optimum DCW of 5.496 g/L and µ of 0.403 h − 1. The experimental results were within the interval range predicted (95% confidence), which demonstrated the reliability of the methodology used.

CRediT author statement

Dayana Morales-Borrell: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Validation, Visualization. Nemecio González-Fernández: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing, Visualization. Rutdali Segura Silva: Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing, Visualizationa, Eladio Salazar Gómez Investigation, Validation

Formatting of funding sources

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Dayana Morales-Borrell: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Validation, Visualization. Nemecio González-Fernández: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. Rutdali Segura Silva: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. Eladio Salazar Gómez: Investigation, Validation.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all the persons that contributed to the results of this paper, in one way or another.

Reference

- 1.Alfonso E.T., Padrón J.R., Peraza T.T., Armas M.M.D.d. Respuesta del cultivo de la habichuela (Phaseolus vulgaris L. var. Verlili.) a la aplicación de diferentes bioproductos. Cultivos Tropicales. 2013;34(3):5–10. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aroniada M., Maina S., Koutinas A., Kookos I.K. Estimation of volumetric mass transfer coefficient (KLa)-Reviewof classical approaches and contribution of a novel methodology. Biochem. Eng. J. 2020;155 doi: 10.1016/j.bej.2019.107458. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bandaru V.V.R., Somalanka S.R., Menduc D.R., Madicherla N.R., Chityala A. Optimization of fermentation conditions for the production of ethanol from sago starch by co-immobilized amyloglucosidase and cells of Zymomonas mobilis using response surface methodology. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2006;38:209–214. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2005.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bun S., Chawaloesphonsiya N., Ham P., Wongwailikhit K., Chaiwiwatworakul P., Painmanakul P. Experimental and empirical investigation of mass transfer enhancement in multi-scale modified airlift reactors. Multiscale and Multidiscip. Model. Exp. and Des. 2019;3:89–101. doi: 10.1007/s41939-019-00063-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bundale S., Begde D., Nashikkar N., Kadam T., Upadhyay A. Optimization of culture conditions for production of bioactive metabolites by Streptomyces spp. Isolated from soil. Adv. Microbiol. 2015;5:441–451. doi: 10.4236/aim.2015.56045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campos, J.M., Vázquez, E.P., Polo, E.S., Fajardo, L.M., Barreras, L.L., Hernández, A.T., Wong, I., and Castillo, A.d. (2020). Generalización del bionematicida HeberNem en Cuba y su relación con los contenidos de materia orgánica en el suelo. Retrieved 17 February 2020, from https://www.academia.edu/18096231/GENERALIZACI%C3%93N_DEL_BIONEMATICIDA_HEBERNEM_EN_CUBA_Y_SU_RELACI%C3%93N_CON_LOS_CONTENIDOS_DE_MATERIA_ORG%C3%81NICA_EN_EL_SUELO_GENERALIZATION_OF_THE_BIONEMATOCIDE_HEBERNEM_IN_CUBA_AND_ITS_RELATIONSHIP_WITH_THE_CONTENT_OF_ORGANIC_MATTER_IN_SOIL.

- 7.Doi T., Kajihara H., Chuman Y., Kuwae S., Kaminagayoshi T., Omasa T. Development of a scale-up strategy for Chinese hamster ovary cell culture processes using the kLa ratio as a direct indicator of gas stripping conditions. Biotechnol. Progress. 2020;36(5) doi: 10.1002/btpr.3000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doran P.M. Elsevier Science & Technology Books; 1995. Bioprocess Engineering Principles. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duta F.P., França F.P.d., Lopes L.M.d.A. Optimization of culture conditions for exopolysaccharides production in Rhizobium sp. using the response surface method. J. Biotechnol. 2006;9:391–399. doi: 10.2225/vol9-issue4-fulltext-7. July 15, 2006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.González N., Zamora J., Ramos L., Pérez E., Pérez C., Salazar E. Transferencia y consumo de oxígeno en el cultivo de alta densidad del microorganismo con actividad bionematicida Tsukamurella paurometabola, C-924. Tecnología Química. 2009;29(3):162–168. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hossain L., Rahman R., Khan M.S. In: Pesticide Residue in Foods: Sources, Management, and Control. Khan M.S., Rahman R., editors. Springer; 2017. Alternatives of pesticides; pp. 147–165. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang X.Q., Zhao J., Zhou X., Han Y.S., Zhang J.B., Cai Z.C. How green alternatives to chemical pesticides are environmentally friendly and more efficient. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2019;70(3):518–529. doi: 10.1111/ejss.12755. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Juárez P., Orejas J. Oxygen transfer in a stirred reactor in laboratory scale. Lat. Am. Appl. Res. 2001;31:433–439. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumari K., Sharma P., Tyagi K., Lal R. Pseudoxanthomonas indica sp. nov., isolated from a hexachlorocyclohexane dumpsite. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2011;61:2107–2111. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.017624-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lugo, I.A., Ortiz, I.S., Padilla, I.W., Sánches, D.S., Valdivia, R.M., and Betartez, L.G. (2019). BIOPESTICIDE AND BIOFERTILISER COMPOSITION (Cuba Patent No. 2019-0071).

- 16.Meyer H.-.P., WolfgangMinas, Schmidhalter D. In: Industrial Biotechnology: Products and Processes. 1st Edition ed. Wittmann C., Liao J.C., editors. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA; 2017. Industrial-scale fermentation; pp. 3–53. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morales-Borrell D., González-Fernández N., Mora-González N., Pérez-Heredia C., Campal-Espinosa A., Bover-Fuentes E., Salazar-Gómez E., Morales-Espinosa Y. Design of a culture medium for optimal growth of the bacterium Pseudoxanthomonas indica H32 allowing its production as biopesticide and biofertilizer. AMB Expr. 2020;10:190. doi: 10.1186/s13568-020-01127-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nayaka S., Chakraborty B., Swamy P.S., Bhat M.P., Airodagi D., Basavarajappa D.S., Rudrappa M., Hiremath H., Nagaraja S.K., Madhappa C. Isolation, characterization, and functional groups analysis of Pseudoxanthomonas indica RSA-23 from rhizosphere soil. J. Appl. Pharm. 2019;9(11):101–106. doi: 10.7324/JAPS.2019.91113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thierry S., Macarie H., Iizuka T., Geißdörfer W., Assih E.A., Spanevello M., Verhe F., Thomas P., Fudou R., Monroy O., Labat M., Ouattara A.S. Pseudoxanthomonas mexicana sp. nov. and Pseudoxanthomonas japonensis sp. nov., isolated from diverse environments, and emended descriptions of the genus Pseudoxanthomonas Finkmann et al. 2000 and of its type species. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2004;54:2245–2255. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02810-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zazueta-Álvarez D.E., Martínez-Prado M.A., Rosas-Flores W., Carmona-Jasso J.G., Moreno-Medina C.U., Rojas-Contreras J.A. Response surface methodology analysis of the effect of the addition of silicone oil on the kLa coefficient in the bioleaching of mine tailings. Water. Air. Soil. Pollut. 2020;231(5):2–11. doi: 10.1007/s11270-020-04573-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]