Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to investigate the panoramic imaging features of cleidocranial dysplasia (CCD) with a relatively large sample.

Materials and Methods

The panoramic radiographs of 40 CCD patients who visited Seoul National University Dental Hospital between 2004 and 2018 were analyzed. Imaging features were recorded based on the consensus of 2 radiologists according to the following criteria: the number of supernumerary teeth and impacted teeth; the shape of the ascending ramus, condyle, coronoid process, sigmoid notch, antegonial notch, and hard palate; the mandibular midline suture; and the gonial angle.

Results

The mean number of supernumerary teeth and impacted teeth were 6.1 and 8.3, respectively, and the supernumerary teeth and impacted teeth were concentrated in the anterior and premolar regions. Ramus parallelism was dominant (32 patients, 80.0%) and 5 patients (12.5%) showed a mandibular midline suture. The majority of mandibular condyles showed a rounded shape (61.2%), and most coronoid processes were triangular (43.8%) or round (37.5%). The mean gonial angle measured on panoramic radiographs was 122.6°.

Conclusion

Panoramic radiographs were valuable for identifying the features of CCD and confirming the diagnosis. The presence of numerous supernumerary teeth and impacted teeth, especially in the anterior and premolar regions, and the characteristic shapes of the ramus, condyle, and coronoid process on panoramic radiographs may help to diagnose CCD.

Keywords: Cleidocranial Dysplasia, Panoramic Radiography, Mandible, Maxilla, Tooth

Introduction

Cleidocranial dysplasia (CCD) is a rare, autosomal dominant form of skeletal dysplasia characterized by abnormalities of the clavicles, skull, and jaws; delayed closure of the fontanelles; and moderately short stature.1,2 The worldwide prevalence of CCD is generally regarded as being about 1 per million.3 It has been revealed that mutation of the runt-related transcriptional factor 2 (RUNX2) gene is a major cause of CCD.4

Hypoplasia or aplasia of the clavicle and delayed or incomplete closure of the calvarial suture have been thought to be key diagnostic features of CCD. Recent detailed clinical investigations have shown that CCD is a generalized form of skeletal dysplasia affecting not only the clavicles and the skull, but the entire skeleton. Therefore, regardless of whether changes in the clavicle or calvarium are observed, CCD can be suspected based on changes in other regions (especially jaw manifestations).

There are several characteristics of the oral manifestations of CCD, including supernumerary teeth and delayed teeth eruption; however, the imaging features of CCD in the dentomaxillofacial region have been reported in case reports or reviews of cases. Few articles have analyzed the imaging features of CCD systemically using panoramic radiography. Since the early diagnosis of CCD is essential for initiating appropriate treatment,5 dentists should be aware of the characteristic features of CCD. In addition, panoramic radiography is the most commonly used type of radiography in dentistry; therefore, it is necessary to determine the characteristic imaging features of CCD seen on panoramic radiographs.

The aim of this study was to investigate the imaging features of CCD on panoramic radiographs with a relatively large sample.

Materials and Methods

Board (IRB) of Seoul National University Dental Hospital (ERI18001). This study was a retrospective, cross-sectional study of patients diagnosed with CCD who visited Seoul National University Dental Hospital between 2004 and 2018.

Patients who received postoperative or postorthodontic treatment and patients with poor-quality panoramic images were excluded. In total, 40 patients were selected from 43 patients with CCD. Demographic information such as age, sex, and surgical history was gathered using electronic dental records. Panoramic radiographs were collected after removing identifiable patient information using a picture archiving and communications system (PACS, G3, Infinitt Healthcare Co., Seoul, Korea). If multiple panoramic radiographs were taken for a single patient, the first radiograph was included in the present study.

Panoramic radiographs were analyzed and the imaging features were recorded by consensus of 2 oral and maxillofacial radiologists with over 10 years of experience. The following characteristics in each image were assessed.

Number of supernumerary teeth and impacted teeth

The total number of supernumerary teeth in each patient was recorded. The numbers in the anterior, premolar, and molar regions of the maxilla and mandible were also recorded. Third molars were excluded from the enumeration of teeth in this study.

Impacted teeth were considered only in the normal dentition, including primary and permanent teeth; that is, impacted supernumerary teeth were not included in the data. A tooth was judged to be impacted if it did not erupt past the following reference times: over 10 years for central and lateral incisors, over 14 years for canines and premolars, over 9 years for first molars, over 14 years for second molars. The total number of impacted teeth in all patients was counted, and analyzed according to sex, age group, and region.

Shape of the ascending ramus, condyle, coronoid process, and sigmoid notch

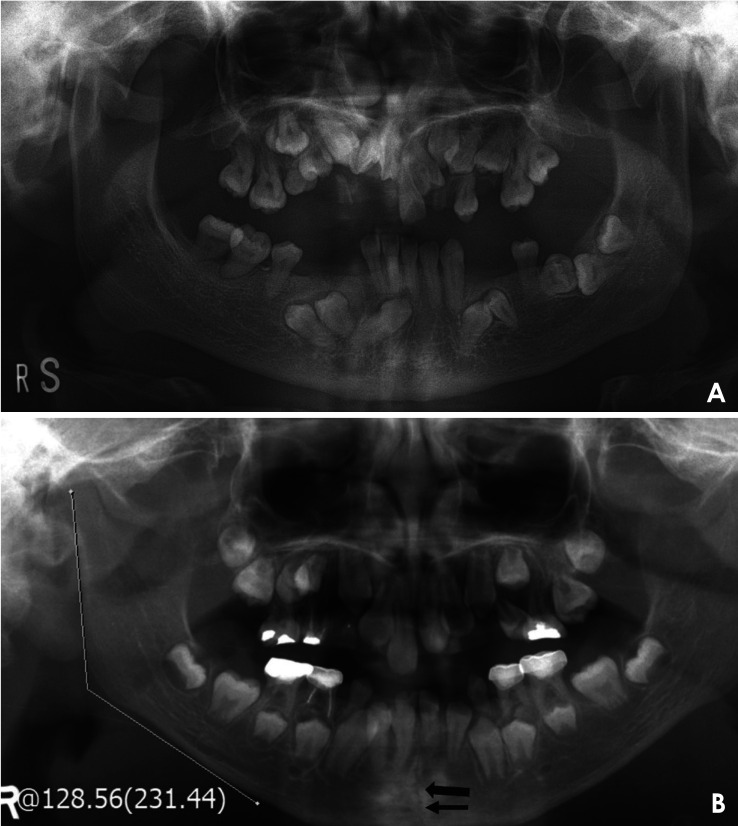

The shape of the ascending ramus was classified as parallel or normal. A parallel shape was defined as the anterior and posterior border of the ramus showing almost parallel borders (Fig. 1A), whereas a normal ramus had a posterior slope and a depression in the middle of the posterior border.

Fig. 1. Typical panoramic radiographs of cleidocranial dysplasia patients. A. Note that the anterior and posterior ascending ramus are parallel. B. This image shows the mandibular midline suture (black arrow) and the method of measuring the gonial angle on panoramic radiographs.

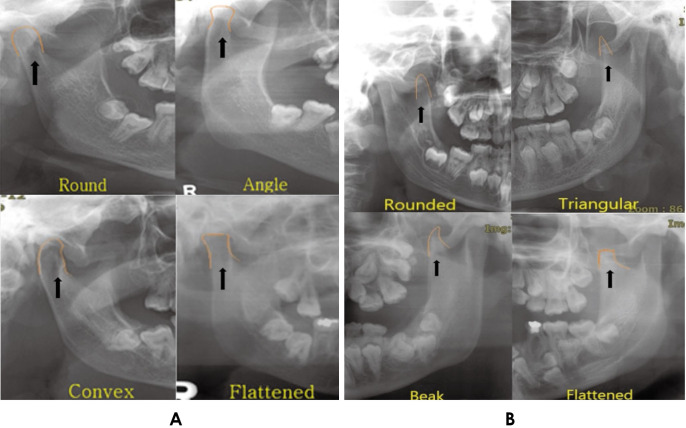

The shape of the mandibular condyle was classified into 4 types (round, angle, convex, and flattened) according to the study of Nagaraj et al. (Fig. 2A).6

Fig. 2. Classification of the shape of the mandibular condyle and coronoid process. A. The shape of the mandibular condyle is divided into round, angle, convex, and flattened. B. The shape of the coronoid process is divided into rounded, triangular, beak, and flattened.

The shape of the coronoid process was classified into 4 types (rounded, triangular, beak, and flattened) according to the study of Furuuchi et al. (Fig. 2B).7

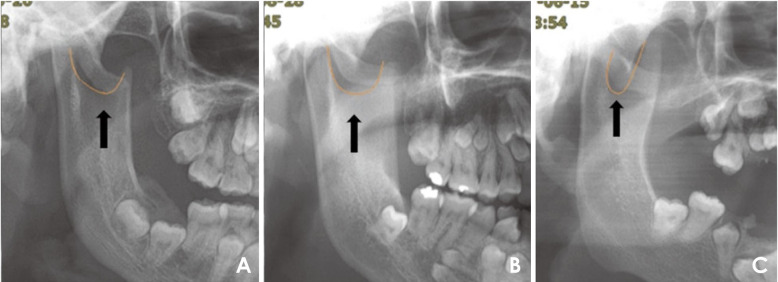

The shape of the sigmoid notch was classified into 3 types (round, sloping, and wide) according to the study of Shakya et al. (Fig. 3).8

Fig. 3. Classification of the shape of the sigmoid notch on panoramic radiographs. A. Rounded, B. Wide, C. Sloped.

Mandibular gonial angle and shape of the antegonial notch

The mandibular gonial angle was measured using protractor in PACS (Fig. 1B).

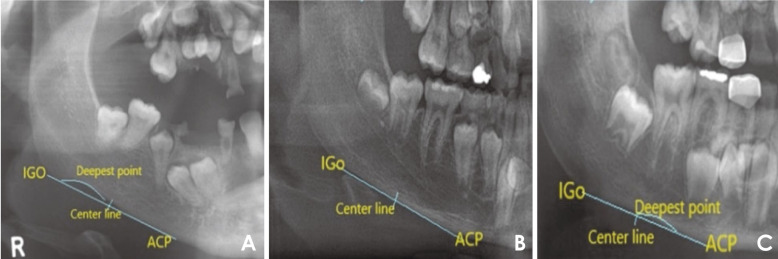

The shape of the antegonial notch was divided into 3 types (asymmetrical posterior, symmetrical, and asymmetrical anterior) according to the study of Dutra et al. (Fig. 4).9

Fig. 4. Classification of the antegonial notch. A. Asymmetrical posterior notch. B. Symmetrical. C. Asymmetrical anterior notch.

Presence or absence of the mandibular midline suture

When the mandibular midline suture was found, it was considered to be present; if not, it was considered absent (Fig. 1B).

Shape of the hard palate

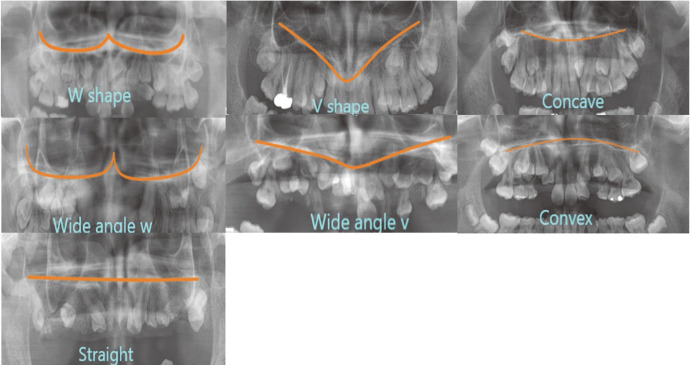

The shape of the hard palate was classified into 7 types (W shape, wide-angle W shape, V shape, wide-angle V shape, concave shape, convex shape, and straight shape) according to the study of Damante et al. (Fig. 5).10

Fig. 5. Classification of the hard palate line on panoramic radiographs. The shape of the hard palate is divided into a W shape, V shape, concave shape, wide-angle W shape, wide-angle V shape, convex shape, and straight shape.

The first step of the data analysis was to calculate descriptive statistics, focusing on the frequency of each variable. Then the data were examined analytically to test for statistically significant differences according to sex, age group, and categorical variables. The statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS version 25 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

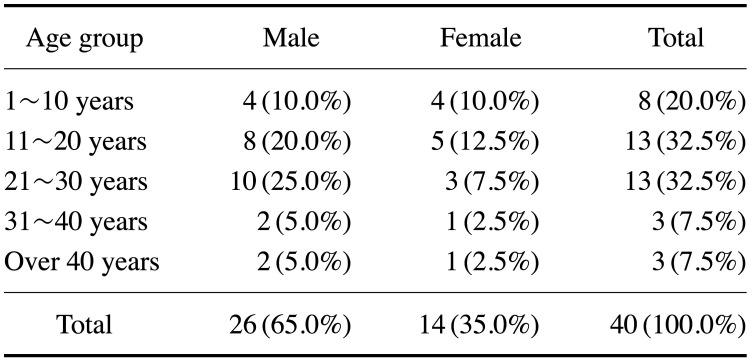

The mean age of the 40 CCD patients in this study was 21.3 years, and their ages ranged from 5 to 59 years. Table 1 shows the distribution of patients with CCD by age group and sex.

Table 1. Distribution of patients with cleidocranial dysplasia according to sex and age group.

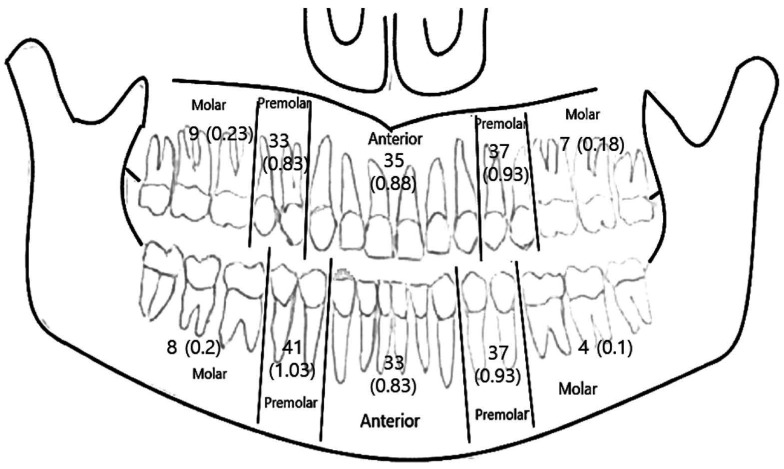

Number of supernumerary teeth and impacted teeth

The mean number of supernumerary teeth per person was 6.1, ranging from 0 to 17. The number of supernumerary teeth was slightly higher in male patients (6.4) than in female patients (5.5); however, the difference was not statistically significant. There was no difference in the number of supernumerary teeth between the maxilla and mandible, and there were significantly fewer supernumerary teeth in the molar region than in the anterior and premolar region (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. The number of supernumerary teeth according to the region on panoramic radiographs. Most of the supernumerary teeth are found in the anterior and premolar regions.

The number of impacted teeth per patient was 0 to 19, with a mean of 8.3 impacted teeth. The mean number of impacted teeth in male and female patients was 9.6 and 5.8, respectively. There was no difference in the number of impacted teeth between the maxilla and mandible, however the impacted teeth were concentrated in the anterior and premolar regions.

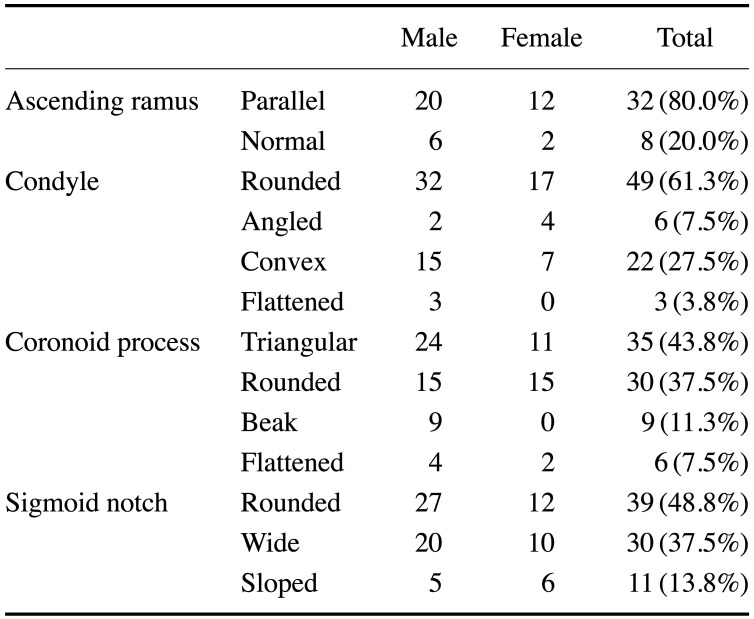

Shape of the ascending ramus, condyle, coronoid process, and sigmoid notch

Thirty-two (80.0%) patients showed a parallel ascending ramus (Table 2). However, there was no statistically significant difference between the sexes or among age groups (P>0.05).

Table 2. Number of patients according to the shape of the ascending ramus, condyle, coronoid process, and sigmoid notch.

The greatest number of mandibular condyles showed a rounded shape (61.2%), followed by a convex shape (18.8%), an angle shape (7.5%), and a flattened shape (3.8%) (Table 2).

Overall, the coronoid process was predominated by triangular (43.8%) and round (37.5%) shapes, followed by beak (11.3%) and flattened (7.5%) shapes; however, a majority of female patients had a rounded shape (53.6%), and none had a beak shape.

The shape of the sigmoid notch was rounded in almost half of the patients (48.8%), followed by the wide (37.5%), and sloping (13.8%) shapes (Table 2). There were no statistically significant differences according to sex or age group (P>0.05).

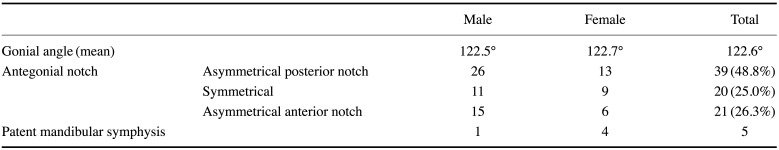

Gonial angle and shape of the antegonial notch

The mean gonial angle measured on panoramic radiographs was 122.6°, and there was no significant difference between male (122.5°) and female (122.7°) patients. The most common shape of the antegonial notch was an asymmetrical posterior notch (Table 3), and there were no statistically significant differences between the sexes or between the sides.

Table 3. Mean gonial angle measurements on panoramic radiographs, and the number of patients according to the shape of the antegonial notch and mandibular symphysis.

Presence or absence of the mandibular midline suture

Only 5 patients (12.5%) showed a mandibular midline suture (Table 3). Among them, 3 patients were under the age of 10, and 1 patient was 34 years old.

Shape of the hard palate

The most frequent shape of the hard palate was a W shape (27.5%), followed by the wide-angle W shape (22.5%), straight shape (15%), convex shape (12.5%), V shape (10%) and wide-angle V shape (10%). The concave shape was found in only 1 case (2.5%).

Discussion

This study investigated the features of panoramic radiographs in a relatively large sample of patients with CCD. The most significant feature observed on panoramic radiographs was a large number of supernumerary teeth and impacted teeth. The mean number of supernumerary teeth was 6.1, and the distribution of supernumerary tooth was concentrated in the anterior and premolar regions. Only 5 patients (12.5%) had no supernumerary teeth. Similar results have been reported previously. Richardson et al. reported that there were 63 supernumerary teeth in 13 subjects, mostly in the mandibular premolar and maxillary incisor regions, and only 2 CCD patients had no supernumerary teeth.1 McNamara et al.,11 and Bufalino et al.12 reported 1 to 20 supernumerary teeth per patient with CCD. The number of impacted teeth was 0 to 19 per patient, with a mean of 8.3 impacted teeth. No previous report presented the number of impacted teeth; however, most articles reported that eruption failure of the permanent dentition was found in most cases.11,13 A large number of supernumerary teeth (hyperdontia) and the impaction of permanent teeth (eruption failure) seem to be closely related. The lack of eruption space due to hyperdontia may result in tooth impaction. Although several hypotheses have been proposed regarding hyperdontia and eruption failure in CCD patients,14,15,16,17,18 there is still no broadly accepted explanation for this phenomenon. However, it seems clear that orthodontic treatment, including the extraction of supernumerary teeth, is essential for the improvement of occlusion and facial morphology.2,5 For the proper treatment timing, an early diagnosis of CCD patients using panoramic radiography is crucial.

In this study, most CCD patients had a parallel ramus shape (80%), round condyle shape (61.2%), a triangular (43.8%) or round (37.5%) coronoid process, and a rounded (48.8%) or wide (37.5%) sigmoid notch. The shape of the ramus in CCD patients has been reported in some articles; among them, McNamara et al.11 summarized the findings clearly as an abnormal shape of the ascending ramus with parallel borders, a U-shaped sigmoid notch, and a slender pointed coronoid process directed upwards and posteriorly. The morphological descriptions of ramus, condyle, and coronoid shapes are similar; therefore, an attempt was made in the present study to divide them more specifically. These shapes seem different from the normal anatomy of the ramus. It is common that the ascending ramus has a slight depression on the anterior and posterior surfaces, and the condyle and round coronoid process make a rather divergent form at the top. However, CCD patients have a rather slender coronoid process and a somewhat convergent form, as well as parallelism of the anterior and posterior ramus on the whole. A previous paper explained these abnormal shapes in CCD patients as resulting from hyperactivity of the temporalis muscle and hypoplasia of the masseter muscle.7 Nonetheless, an overall explanation and understanding of abnormal musculoskeletal development in CCD patients are still lacking.

Although this has not been specifically mentioned in previous reports, the authors observed cases where the angle from the inferior border of mandible to the posterior ramus was somewhat vertical, and thought that the gonial angle might be different from normal. However, the mean gonial angle was 122.6°, which is not meaningfully different from the normal gonial angle measured on panoramic radiographs.19 The hypothesized morphologic impression that the gonial angle would be closer to vertical is probably derived from the morphological characteristics of the posterior ramus without concavity, and this issue should be clarified through further research on the concave form of the anterior and posterior ramus shape between normal and CCD patients. In further studies, the shape of ramus should be compared to panoramic radiographs of healthy, normal participants, and the presence and extent of the antegonial notch should be analyzed.

According to this study, 5 out of 40 CCD patients (12.5%) showed a mandibular midline suture, which is a lower proportion than in other reports.11 Although not all the patients had a patent mandibular symphysis, it is a very important imaging finding that triggers suspicion for CCD, because the suture normally closes before 1 year of age; therefore, it is not usually observed on panoramic radiographs.

This study has some limitations. First of all, there was no control group; therefore, the analyzed imaging features cannot be compared with panoramic imaging of normal, healthy individuals. Furthermore, this study did not evaluate the diagnostic ability of these specific imaging features. In further research, it will be necessary to extract pathognomonic imaging features using logistic regression and conduct an accuracy test for the diagnosis of CCD. Nonetheless, this study is meaningful in that it analyzed several imaging features with a relatively large number of CCD patients' panoramic radiographs and extracted features that may be helpful for diagnosis. The key to CCD management is early diagnosis, because dental and maxillofacial treatment strategies depend on the patient's age and an early diagnosis can help ensure that physicians do not miss the most suitable time for treatment given the patient's trajectory of development and growth. Although not all of the features in this study were significantly helpful, it is expected that further research will identify ways to improve diagnostic accuracy by combining imaging patterns based on the imaging features analyzed in this study.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None

References

- 1.Richardson A, Deussen FF. Facial and dental anomalies in cleidocranial dysplasia: a study of 17 cases. Int J Paediatr Dent. 1994;4:225–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263x.1994.tb00139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farrow E, Nicot R, Wiss A, Laborde A, Ferri J. Cleidocranial dysplasia: a review of clinical, radiological, genetic implications and a guidelines proposal. J Craniofac Surg. 2018;29:382–389. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000004200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roberts T, Stephen L, Beighton P. Cleidocranial dysplasia: a review of the dental, historical, and practical implications with an overview of the South African experience. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2013;115:46–55. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2012.07.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang YW, Yasui N, Ito K, Huang G, Fujii M, Hanai J, et al. A RUNX2/PEBP2αA/CBFA1 mutation displaying impaired transactivation and Smad interaction in cleidocranial dysplasia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:10549–10554. doi: 10.1073/pnas.180309597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yeom HG, Park WJ, Choi EJ, Kang KH, Lee BD. Case series of cleidocranial dysplasia: radiographic follow-up study of delayed eruption of impacted permanent teeth. Imaging Sci Dent. 2019;49:307–315. doi: 10.5624/isd.2019.49.4.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nagaraj T, Nigam H, Santosh HN, Gogula S, Sumana CK, Sahu P. Morphological variations of the coronoid process, condyle and sigmoid notch as an adjunct in personal identification. J Med Radiol Pathol Surg. 2017;4:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Furuuchi T, Kochi S, Sasano T, Iikubo M, Komai S, Igari K. Morphologic characteristics of masseter muscle in cleidocranial dysplasia: a report of 3 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;99:185–190. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shakya S, Ongole R, Nagraj SK. Morphology of coronoid process and sigmoid notch in orthopantomograms of south Indian population. World J Dent. 2013;4:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dutra V, Yang J, Devlin H, Susin C. Mandibular bone remodelling in adults: evaluation of panoramic radiographs. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2004;33:323–328. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/17685970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Damante JH, Filho LI, Silva MA. Radiographic image of the hard palate and nasal fossa floor in panoramic radiography. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998;85:479–484. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(98)90078-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McNamara CM, O'Riordan BC, Blake M, Sandy JR. Cleidocranial dysplasia: radiological appearances on dental panoramic radiography. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 1999;28:89–97. doi: 10.1038/sj/dmfr/4600417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bufalino A, Paranaíba LM, Gouvêa AF, Gueiros LA, Martelli-Júnior H, Junior JJ, et al. Cleidocranial dysplasia: oral features and genetic analysis of 11 patients. Oral Dis. 2012;18:184–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2011.01862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Golan I, Baumert U, Hrala BP, Müssig D. Dentomaxillofacial variability of cleidocranial dysplasia: clinicoradiological presentation and systematic review. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2003;32:347–354. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/63490079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Counts AL, Rohrer MD, Prasad H, Bolen P. An assessment of root cementum in cleidocranial dysplasia. Angle Orthod. 2001;71:293–298. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2001)071<0293:AAORCI>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lossdörfer S, Abou Jamra B, Rath-Deschner B, Götz W, Abou Jamra R, Braumann B, et al. The role of periodontal ligament cells in delayed tooth eruption in patients with cleidocranial dysostosis. J Orofac Orthop. 2009;70:495–510. doi: 10.1007/s00056-009-9934-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manjunath K, Kavitha B, Saraswathi TR, Sivapathasundharam B, Manikandhan R. Cementum analysis in cleidocranial dysos2021-08-11osis. Indian J Dent Res. 2008;19:253–256. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.42960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lukinmaa PL, Jensen BL, Thesleff I, Andreasen JO, Kreiborg S. Histological observations of teeth and peridental tissues in cleidocranial dysplasia imply increased activity of odontogenic epithelium and abnormal bone remodeling. J Craniofac Genet Dev Biol. 1995;15:212–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suda N, Hamada T, Hattori M, Torii C, Kosaki K, Moriyama K. Diversity of supernumerary tooth formation in siblings with cleidocranial dysplasia having identical mutation in RUNX2: possible involvement of non-genetic or epigenetic regulation. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2007;10:222–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-6343.2007.00404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Radhakrishnan PD, Sapna Varma NK, Ajith VV. Dilemma of gonial angle measurement: panoramic radiograph or lateral cephalogram. Imaging Sci Dent. 2017;47:93–97. doi: 10.5624/isd.2017.47.2.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]