Abstract

The current COVID-19 outbreak has duly influenced tourists' psychology and subsequently their behavior and decision making to participate in outdoor activities. The purpose of this paper is to illuminate tourists' motivations, perceived constraints, and negotiation strategies to participate in outdoor recreation trips, within the current COVID-19 context. To explore and categorize motivating factors, constraints, and negotiation strategies, we employed a qualitative approach via semi-structured online focus group discussion with 16 tourists (mostly residents of Utah, United States) during late summer 2020. First, COVID-19 related restrictions and fewer opportunities to go outdoors were found to encourage outdoor recreation, for novelty-seeking and experiencing normalcy. Through content analysis, we found that tourists experience a blend of personal, social, practical, and ethical constraints. Additionally, we identified how tourists negotiate their constraints through different ways: by extensive planning and information searching, avoiding crowds, and changing leisure aspirations. Finally, we discuss theoretical and managerial implications of the study, followed by recommendations for future research.

Management implications

Understanding of tourists' motivations, constraints, and negotiation strategies—relevant to outdoor recreation trips—provides several managerial implications to destination managers and marketers, as outlined below:

-

•

Lack of centralized and reliable information was frequently cited as a constraint in the focus group discussions. In order to provide adequate and timely information to potential participations, we proposed a novel website template including details about information to be presented.

-

•

As our study sheds light on tourists' companionship preferences, activity choice, and evaluation of a destination's COVID-related operational practices, we propose several advertising strategies and destination operational guidelines to attract tourists.

Keywords: Constraints, Negotiation, Motivations, Information search, COVID-19, Tourism, Outdoor recreation

1. Introduction

In 2020, the novel coronavirus COVID-19, transmitted by respiratory droplets (human interaction) (Wilder-Smith & Freedman, 2020), expanded shortly to the whole world after first being identified in Wuhan, China, in December 2019. In response, most countries (including the US) initiated nonpharmaceutical interventions (Gössling et al., 2020) to curb the transmission rate by deploying various measures such as lockdowns (stay-at-home orders, regulatory quarantine), physical distancing, closures of facilities (restaurants, schools/universities, nonessential businesses), bans on larger public gatherings, and cancellations or postponements of events (such as concerts, conferences, sports).

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in the hospitality and tourism industry is unprecedented. In 2020 alone, travel spending in the United States recorded a staggering loss of $492 billion compared to 2019, representing a 42% decline. International and business travel suffered a significant decline of more than 70%, whereas leisure and domestic travel spending fell by 27% and 26% respectively (Tourism Economics, 2021). The effect of COVID-19 was observed all over the US with 18 states experiencing more than a 40% downfall in travel spending (Tourism Economics, 2021). Additionally, the rate of hotel occupancy also decreased more than 44% in 2020, resulting in a loss of more than 7 million jobs (Tourism Economics, 2021). As the tourism industry contributes to about 3% of the gross domestic product of the US (in 2019) (Bureau of Economic Analysis, 2021), along with generating employment for millions, it is of prominence to understand how the pandemic has shaped tourist behaviors and decision making processes (Kock, Nørfelt, Josiassen, Assaf, & Tsionas, 2020, Zenker and Kock, 2020), to aid tourism recovery in the US. Along this line, this study takes a primitive step in understanding tourists' psyches during the initial timeline of pandemic emergence.

The COVID-19 pandemic in general and specific COVID-19 related restrictions are likely to affect tourists' outdoor recreation behavior. More specifically, the coronavirus pandemic could have profound psychological impacts in tourists' thinking, feeling, and emotions, and thereby modify tourists' outdoor decision-making processes. Tourists' outdoor recreation behaviors could be shaped by subjective evaluations of safety and hygiene considerations, social-peer pressure and responsibility, destination image, uncertainty, and behaviors of local communities (Kock et al., 2019a, 2019b; Baloglu, 2000). Destination related factors such as the closure of facilities, limited opportunities for food, lodging, and accommodation, plus lack of socialization could further hinder outdoor recreation participation. Furthermore, changes in time use patterns initiated by working remotely or being unemployed could also provide additional incentives for people to travel outdoors.

One way to examine tourists' behaviors is well-documented in leisure literature as the study of motivations, constraints and negotiations. Interaction between these factors are found to influence outdoor (or leisure) participation (Crawford et al., 1991; Crawford & Godbey, 1987; Godbey et al., 2010). This study adopts a qualitative approach via focus groups to illuminate these three key dimensions of tourists' behaviors during the current pandemic situation. The study particularly focuses on an outdoor recreation trip, which is defined as a “journey involving at least one overnight stay away from home, and where the purpose is to engage in recreational activities in an outdoor or natural environment.” The rationale for attention to overnight trips in an outdoor environment in the current context is because of the complexity in decision making to participate on such trips; tourists' social, personal, and ethical constraints, and tourists' direct involvement with multiple facets of the tourism industry.

The paper is structured as follows. First, a brief review of the leisure constraint-negotiation process and learnings of tourists' behavior from past disasters is presented. Then, research questions are proposed for the study. The following data section describes the sample and details the data collection process. Then, findings from the data analysis are displayed in the results section. Finally, a discussion of results as well as theoretical and managerial implications along with limitations and a direction for future research are outlined.

2. Relevant literature

There are scant studies focused on outdoor recreation in post-disaster and crisis contexts (Kono, 2018). In the following section, an overview of leisure research in terms of theoretical frameworks (constraints, negotiation, and motivations) is first provided. Second, the literature on tourists' behavior post-disasters is reviewed, focusing on behavioral changes and coping mechanisms that affects tourists' outdoor recreation behaviors. Finally, research gaps are noted and the study's specific research questions are specified.

2.1. Leisure constraints, negotiations, and motivations

Over the last four decades, leisure constraints and related concepts have been used extensively to examine leisure behaviors, in general or for a particular leisure activity, such as hunting (e.g. Metcalf et al., 2015), fishing (e.g. Lyu & Oh, 2014), and outdoor recreation (White, 2008). First, Crawford and Godbey (1987) posited that participation in leisure-related activities could be inhibited by three types of constraints: intrapersonal, interpersonal, and structural constraints. Intrapersonal constraints such as fear, anxiety, and attitudes are individual-level psychological attributes that affect preference for an activity. These types of constraints are relatively unstable and constantly evolving depending upon contextual and environmental factors (Godbye et al., 2010). Interpersonal constraints such as the unavailability of companions or partners for participation in a leisure activity might interact with both preference and participation. These constraints depend upon life cycle stage, marital status, or activity type (Crawford & Godbey, 1987). Structural constraints are intervening factors affecting both leisure preference and participation, such as time and cost, information, weather, etc. (Godbye et al., 2010). The leisure constraint model also suggests that these three constraints are encountered hierarchically, with intrapersonal constraints being the most proximal and structural constraints the most distant (Crawford et al., 1991).

As the leisure constraint research matured, the concept of the negotiation of constraints emerged (Jackson et al., 1993), which suggests that constraints do not necessarily cause non-participation, but rather that people find ways to reduce the impacts of these constraints in their preferred leisure activities (Hubbard & Mannell, 2001; Godbey et al., 2010). Negotiation strategies could include changes in leisure, such as timing and schedule, and changes to non-leisure aspects of life, such as the rearrangement of work schedules and the reduction of other expenses, in order to facilitate leisure participation (Lyu & Oh, 2014).

The other important attribute in the conceptualization of leisure constraints, negotiation, and participation is motivation. Motivation can be thought of as comprising the “push factors” which determine why people engage in a particular leisure activity (Manfredo et al., 1996). The motivation to participate in a leisure activity might stem from psychological or sociological pursuits of an individual. Some of the reasons to participate in leisure activities are achievement (gaining self-confidence), enjoying nature, escaping from the routine environment, and socialization. The outcomes of the negotiation process depend upon the relative strengths of constraints and motivations for participation, hence the relationship between constraints and motivation is assumed to be inversely related (see Hubbard & Mannell, 2001; Son et al., 2008; White, 2008).

In summary, a lot of quantitative as well as qualitative studies have explored different dimensions of constraints and how people overcome constraints to ensure continuing participation in leisure activities. In this study, we attempt to add to the theoretical dimension by first exploring a constraint item pool and the relationships with subsequent negotiation process during a novel contextual setting of the COVID-19 pandemic.

2.2. Post-disaster tourists' behavior

The tourism industry has been compromised by past disasters and crises throughout history, and a review of post-disaster behaviors can shed light onto how a pandemic (or pathogen threat) shapes tourists' behaviors in different ways. Although not exactly described in the literature as “constraints,” the issues that disasters introduce can be thought of as representing the same idea: i.e., factors that hinder tourism or outdoor recreation participation. Similarly, the coping strategies formed by tourists to participate in their preferred activity can be thought of as negotiation strategies. In the following section, we discuss relevant constraints and negotiation strategies that are initiated by diseases and pathogen threats.

First, research shows that a vital constraint to tourism participation is crowdedness; i.e., the threat of disease transmission can shift tourists' behaviors in such a way that results in the avoidance of overcrowded destinations in favor of wilderness areas and less populated destinations (Wang & Ackerman, 2019). Another constraining factor can be termed xenophobia (Faulkner et al., 2004): fear of strange things and uncertainty. Kock et al. (2019a) suggests that influenza or pathogen threats could result in a disinclination towards foreign travel and trying foreign food, plus a preference for group travel as well as getting vaccinations and travel insurance. The idea that people develop collective responsibility towards a disease threat (Cashdan & Steele, 2013), and try to support their local economy by selecting nearby or domestic destinations, is referred to as tourism ethnocentrism (Kock et al., 2019a).

Now, we look back at the impacts of SARS—a similar pathogen outbreak which emerged in China in 2003—on tourists' behaviors, as it shares considerable similarities with the current pandemic due to the nature of the virus as well as the nature of imposed restrictions. A study of SARS' impact on tourist psychology by Liu (2003) pointed out that a possible blowout of demand post-SARS would be due to several factors, including stimulus-seeking, sentience-depriving, expectation positive contract, release of tension, and account separation. Jiachen (2003) postulated that there would occur certain changes in companionship preferences, with most people likely to tour with people they know including family and relatives. The authors suggested that activities that result in less contact with people and demand for natural and eco-tourism would be more popular, with people changing their leisure preferences: length of stay, travel mode, etc. Interestingly, the SARS outbreak had Chinese travelers thinking more about hygiene and safety while traveling (Wen et al., 2005), and the perceived impacts of SARS on travel intention, behavior, and patterns was different from people with different demographic profiles. The impact of SARS on tourists' life, attitudes, and safety and hygiene considerations was found to vary depending upon age (younger people had a stronger preference for outdoor activities), income and education (high income and educated people had greater safety concerns), and job type (medical workers and relatives were more conservative about the virus) (Wen et al., 2005). Other disasters such as Ebola, the bird flu, and influenza pandemics (Cahyanto et al., 2016; Page et al., 2006; Zeng et al., 2005) show similar impacts on tourists' behaviors as mentioned above.

In cases of natural disasters that damaged tourist destinations (such as earthquakes, volcanos, and tsunamis), the initial period was usually characterized by a decrease in tourist arrivals (Peters & Pikkemaat, 2006; Huang & Min, 2002; Park & Reisinger, 2010). Tourists' perceptions of natural disasters and travel risks were influenced to a greater extent by their familiarity with the destination and knowledge of the local culture at the destination (Milman & Pizam, 1995; Han, 2005; Reisinger & Mavondo, 2006). Similar to a pathogen threat, tourists generally preferred to travel with family or friends in their immediate circle, in the aftermath of natural disasters (Weber & Hsee, 1998). Like the cases of pathogen threat, tourists' experiences of constraints regarding risks posed by natural disasters also varied across socio-demographic characteristics such as gender (Brug et al., 2004; Kozak et al., 2007), education (Sönmez & Graefe, 1998), and age (Gibson & Yiannakis, 2002).

Additionally, manmade disasters such as 9/11, the war in Iraq, and Middle East chaos have been observed to influence tourists' perceptions on air travel, safety, destination image, and willingness to participate (e.g., Floyd et al., 2004). In short, both natural and manmade disasters, within their context, have been shown to have both comparable and unique impacts on tourists' behaviors. As tourists' perceptions of constraints, motivations, and negotiation strategies evolve dynamically with situational and environmental contexts, we add to this literature through a detailed exploration of these concepts within the current COVID-19 pandemic.

2.3. Research gaps

An emerging body of research is dedicated to elucidating tourists' perceptions and behavioral responses to the COVID-19 threat. Early pandemic research focused on identifying the dimensions of risk posed by COVID-19 (e.g. Xu et al., 2021) and investigating the effects of risk perception on behavioral intentions (revisitation and recommendation intentions to travel in the future) (Bae & Chang, 2021, Neuburger & Egger, 2021, Zhu & Deng, 2020). Another line of research was centered around the financial and social costs of COVID-19 on tourism (Qiu, Park, Li, & Song, 2020, Khalid, Okafor, & Burzynska, 2021) and recommendations for tourism recovery strategies and policies (Qiu et al., 2020). Other studies explain future intentions for leisure participation using traditional variables such as attitudes, motives, and self-efficacy, along with COVID-19 induced attributes such as perceived COVID-19 infect-ability, risk awareness, and information acquisition, through extending past models such as the Theory of Planned Behavior (Das & Tiwari, 2021, Kock, Nørfelt, Josiassen, Assaf, & Tsionas, 2020, Sánchez-Cañizares, Cabeza-Ramírez, Muñoz-Fernández, & Fuentes-García, 2021, Seong & Hong, 2021). All of these studies aim to provide empirical evidence of relationships between variables, but they fail to provide a complete picture of what tourists consider or what strategies they develop for leisure participation. Hence, what is lacking in the current COVID-19 research is a detailed assessment of tourists' decision-making processes considering a broad array of individual, social, and ethical barriers to outdoor recreation participation. There is also a need to evaluate the consequences of government restrictions and regulations on tourist behaviors. In an attempt to fill this literature gap and provide a complete picture of tourists' decision-making processes, this study captures tourists' first-hand perceptions of constraints, negotiations, and motivations for outdoor recreation participation during the COVID event through a focus group setting. In other words, the objective of this study is to find answers to the following research questions:

-

•

What motivates tourists to participate in outdoor recreation trips during the current COVID-19 pandemic?

-

•

What types of constraints on outdoor recreation do tourists experience during the pandemic?

-

•

What negotiation strategies do tourists apply to overcome these constraints?

3. Data

A qualitative methodology was used to explore a small sample of tourists' perceptions, motivations, constraints, and negotiation strategies during decision-making and while participating on an outdoor recreation trip. The use of qualitative methods is more suitable than quantitative methods because of their ability to entice a rich description of people's perceptions and opinions (Neuman, 2006) regarding making outdoor recreation trips during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data were collected through focus group sessions with 16 adult tourists in the US, conducted online through the video meeting platform Zoom. Participants were primarily recruited through social media (LinkedIn, Twitter, Nextdoor, Meetup, etc.). To participate in the study, participants were first required to sign up via an initial survey, which asked about their demographics, past frequency of participation in outdoor recreational trips, and a ranking question about constraints. Further, participants were provided with options to choose a particular focus group session, based on their availability. Once participants completed the initial survey, they were provided with a Zoom link for the focus group session. To reduce the drop-off in attendance, participants were reminded via email of the focus group session one day before with a message to notify researcher if they were unable to attend the session. Additionally, participants were provided with a $10 online gift card as an incentive, once they completed the initial survey and attended a focus group session.

The sample consisted of participants of varied age, income, gender, and employment attributes. Most of the respondent were Utah residents, except 2 participants who resided in the District of Columbia and California. Moreover, the sample was somewhat non-representative in the case of race (with more white participants) and education (all participants had at least a bachelor's degree), compared to the US population. See Table 1 for details.

Table 1.

Sample demographics (N = 16).

| Variable | # | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 18-24 | 3 | 18.8 |

| 25-34 | 5 | 31.3 |

| 35-44 | 1 | 6.3 |

| 45-54 | 5 | 31.3 |

| 55-64 | 2 | 12.5 |

| Household Size | ||

| 1 | 5 | 31.2 |

| 2+ | 11 | 68.8 |

| Education | ||

| Bachelors or undergraduate degree | 10 | 62.5 |

| Graduate or professional degree | 6 | 37.5 |

| Employment | ||

| Full time | 8 | 50.0 |

| Part time | 6 | 37.5 |

| Unemployed | 2 | 12.5 |

| Retired | 0 | 0.0 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 9 | 56.3 |

| Female | 7 | 43.8 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Asian | 3 | 18.8 |

| White | 11 | 68.8 |

| Latino or Spanish origin | 2 | 12.5 |

| Past Participation Frequency | ||

| 0 | 3 | 18.8 |

| 1 | 3 | 18.8 |

| 2 | 3 | 18.8 |

| 3 | 1 | 6.3 |

| 4 | 1 | 6.3 |

| 5+ | 5 | 31.3 |

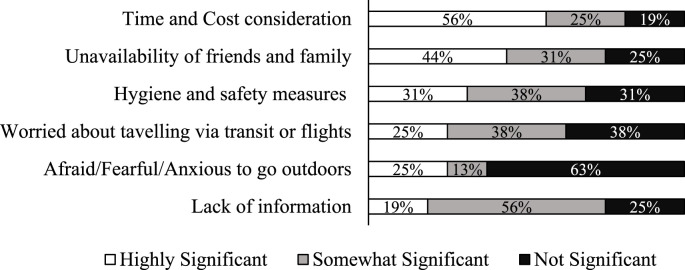

In the initial survey, respondents were asked to rate six constraints according to their significance (1 was Least Significant, 6 was Most Significant) in decision-making for going on an outdoor recreation trip. As shown in Fig. 1 , most respondents (>50%) indicated time and cost considerations as their most significant constraint, followed by unavailability of friends and family (44%) and hygiene and safety measures during travel and at destinations (31%). Additionally, respondents did not seem to be fearful or anxious to go outdoors due to COVID-19, as that particular factor was perceived to be the least significant (63% respondents had ranked it as lowest). Furthermore, respondents also did not seem to be much concerned about information about facilities and services at destinations and traveling via transit or flights.

Fig. 1.

Ranking of constraints (N = 16).

3.1. Focus group proceedings

Five online focus group sessions were conducted with 2, 3, 4, 3, and 4 participants respectively in each session. Each session was about 45–60 min long. All of the focus group sessions took place during August and September 2020, before the availability of COVID-19 vaccines. Focus group sessions were scheduled during the morning and evening on weekdays and during mid-day on the weekend. The focus group sessions followed a semi-structured approach beginning with a probing question about each participant's recent outdoor recreation trip (the definition of an outdoor recreation trip was provided at the start of the session), and moving on to more specific questions about their motivations, constraints, and negotiation strategies. These specific questions were derived from previous qualitative studies related to motivations, constraints, and negotiation (Koca, Henderson, Asci, & Bulgu, 2009, Fendt and Wilson, 2012). Sample focus group questions are included in Table 2 . The audio for each session was recorded on the moderator's (first author's) local computer and then transcribed manually. No personal names are employed in the paper to protect the privacy of the participants. These research procedures were reviewed and approved by the [university] Institutional Review Board, Protocol #11318.

Table 2.

Sample focus group questions.

| When was your recent outdoor recreation trip and how was the experience? |

| What motivates you or what experiences do you seek when going on an outdoor recreation trip? |

| Does COVID-19 related restrictions drive you more to go on outdoor recreation trip? |

| What are the factors that affect your decision about going on an outdoor recreation trip? |

| What are the difficulties that have been raised for your participation in outdoor recreation trip? In other words, think of ways that this pandemic has caused any inconveniences. |

| What are some of the ways that you could tackle or overcome those inconveniences/obstacles when planning or during your outdoor recreation trip? In other words, how will you prepare yourself? |

3.2. Data analysis

The data analysis followed a directed content analysis approach, where existing theory guides the initial coding scheme or relationship between codes (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). First, the audio of the focus group recordings was transcribed manually. Then, each item was coded under the separate categories of motivations, constraints, and negotiation strategies. Codes which were similar and described a certain theme were grouped together, as described in the previous studies. For instance, “unable to find friends to travel with” or “don't feel safe traveling with friends” were kept under the category of interpersonal constraints as suggested by Crawford and Godbey (1987). Any new codes found were kept in a different category and were grouped together into a new theme according to the commonalities and differences. The new codes collected were constantly compared to their fit with already existing themes. In this way, data were broken down into more meaningful units and subthemes, and hence processes and relationships could be identified.

The concept of saturation was used to determine the adequacy of the sample size. Saturation refers to the stage in data collection where similar ideas and issues begin to be repeated and further data collection becomes redundant (Hennink et al., 2019). For this purpose, the author compared codes of previous focus group discussions with the new ones. When going through the focus group transcripts, only two new codes were identified during the fifth focus group discussion, which suggested that almost all key ideas were covered by the focus groups and that saturation was reached.

4. Findings

4.1. Motivations

Using the directed content approach and thematic analysis, 27 motivating items for outdoor recreation participation was found. These items pertaining to motivations were then grouped under seven themes (domains) listed in the Recreation Experience Preference Scale (Manfredo et al., 1996); a new COVID-built motivation theme was also identified. As expected, most of the motivations mentioned by participants during the focus group were similar to items used in previous quantitative studies (Hubbard & Mannell, 2001; Son et al., 2008; White, 2008) for constraint-negotiation models, as well as findings from previous qualitative studies (e.g., Fendt & Wilson, 2012).

As many people were mostly confined within the four walls of their homes due to changes in work environments (working remotely) or fewer opportunities to go outside, due to COVID related restrictions, novelty experience (seeing new destinations) and exploration remained the most repeated themes in the focus group sessions. As shown in Table 3 , COVID-19 related restrictions and the environment was one of the driving factors behind people participating in an outdoor recreation trip. Interestingly, most tourists perceived the outdoors as being safe from COVID and regarded outdoor recreation trips as a way to get away from toxic news in the environment.

May be for most part, going outdoors is very safe, unless you are in sustained contact with any person passing in trail.

I don't have a fear being outside and catching COVID. I know it can happen, I have not looked at statistics, but I feel very safe when I am outside, especially when I practice social distancing.

For me, a big driver is to get away from my phone and toxic news in my environment and it works pretty well. So I seek out places where there are no cell service and can't use my phone.

Table 3.

Tourists' motivations for outdoor recreation trips.

| Themes | Motivations | Number of referencesb |

|---|---|---|

| Enjoy Nature | To view scenery/beautiful destinations | 10 |

| To be closer to nature | ||

| To enjoy smells and sound of nature |

||

| Autonomy | To be alone | 5 |

| To detach from other things |

||

| Physical fitness | To get exercise | 6 |

| To be physically fit |

||

| Rest | To relax and rest | 4 |

| To reenergize and be in peace |

||

| Escape personal-social-physical pressure | To experience peace and tranquility | 9 |

| To be on my own | ||

| To break norm | ||

| To be away from people and civilization | ||

| To be away from technology | ||

| To be away from cars |

||

| Family and friends | To enjoy with friends | 5 |

| To do things with people who enjoy same things | ||

| To bond with family and friends | ||

| To have family time |

||

| Novelty experience | To see things you've never seen before | 14 |

| To explore tourist places you've never been before | ||

| To experience a new city | ||

| To have new experiences |

||

| COVID-built motivationsa | To be away from toxic news in the environment | 8 |

| To set yourself free from having to stay at home | ||

| To experience normalcy | ||

| To feel safe in an outdoor environment |

New themes emerged due to COVID.

The numbers in this column do not equal 16 as each participant stated several motivating factors.

Some participants also cited that going on these trips and connecting with nature would allow them to relive some sort of normalcy like before the COVID-19 outbreak. Additionally, some participants felt that a lack of other people's participation in outdoor recreation trips has provided opportunities to visit destinations that would generally be crowded.

If I were to take a recreation trip that would be overnights, a big draw for me would be to get back to normalcy in some aspects, such as without wearing marks, or all other things that I have to worry about when going to a grocery store. Getting back to normalcy before pandemic settings like that.

I am climbing a wall in Yosemite this fall, because of lack of people in Yosemite right now, and that's been inspiring me like now's the time, because usually these walls are difficult to get on and not be stacked up with other people.

One of the advantages of being outdoors since mid-March, there seems to be not nearly people taking advantage of opportunities of exploring national parks or other beautiful places. Most people are fearful of leaving homes. It's been really easy to access these areas than it has ever been.

4.2. Constraints

As described above, 36 different constraints could be identified, and using the directed content approach, they were then grouped broadly into 10 different themes, including intrapersonal constraints, interpersonal constraints, and others (Crawford & Godbey, 1987), in an effort to elucidate the factors that limited tourists' participation in outdoor recreation trips. The structural constraint was not used as a grouping theme, as previous studies have suggested the possibility of multiple sub-dimensions within the structural context such as time and cost (e.g. Hawkins & Joanne Peng, 1999; Nyaupane & Andereck, 2008; Nyaupane et al., 2004). The constraints that these 16 participants faced align with previous concepts of leisure constraints proposed by Crawford and Godbey (1987), along with new constraints added due to the COVID-19 outbreak and restrictions that followed with it.

As seen in Table 4 , tourists felt predominantly limited by interpersonal constraints, particularly being unable to find people to go on a recreation trip with, as well as added complications that come with going outdoors with others. Responses were coherent in a sense that most participants perceived traveling with family and roommates as being safe. However, people having high-risk family members, such as older people, were more reluctant to go on outdoor trips, fearing of COVID transmission.

Right now, it's only family first for things. Even if we drive in separate cars, to the same destination with friends, you have to think about maintaining social distancing and how close you are when hiking and it is sort of annoying and it's a mental burden. No one is reaching out to anyone anymore and doing things.

I have family in Southern Utah, and I typically stay 2–3 weeks in a year there. But this year, I have a grandpa who is a high risk. And I don't want to put her in danger.

Table 4.

Tourists constraints to outdoor recreation.

| Themes | Constraints | Number of referencesb |

|---|---|---|

| Intrapersonal | Fear of being exposed to COVIDa | 5 |

| Fear of being a carriera | ||

| Anxious when going to gas stations and grocery stores at destinationa | ||

| Don't know what to do if I feel sick at destinationa | ||

| Interpersonal | Friends little hesitant to go | 16 |

| Don't know if my friends have been quarantining or practicing social-distancinga | ||

| Don't feel safe traveling with friendsa | ||

| Putting someone at my family on risk (older people)a | ||

| Traveling with family is the only optiona | ||

| Traveling with people you don't knowa | ||

| People having different perceptions of COVIDa | ||

| Lack of partners/friends to go with | ||

| Safety and Hygiene | Inadequate sanitization measures at destination or nearby services at gas stationsa | 8 |

| Lack of public restrooms and ventilation (air circulation)a | ||

| Lack of health facility/hospitals at/near the destinationa | ||

| Crowd | Too much crowds make it scarya | 12 |

| Unable to practice social distancing when it is overcrowdeda | ||

| Facilities | Closure of facilities at the destinationa | 12 |

| Closure of restaurants/Only pick-upa | ||

| Fewer options for fooda | ||

| Not getting the full outdoor experience, due to COVIDa | ||

| Finding accommodation to stay before/after outdoor experience | ||

| Time and Cost | Destination too far away to drive/bike | 8 |

| School and family schedules | ||

| Personal, family and schedules of friends mixed and matched | ||

| Travel | Driving is the only option | 9 |

| It's not safe/comfortable to travel via flightsa | ||

| It's about getting to and from the destination | ||

| Cannot go to very far or remote tourist places because of added complicationsa | ||

| Weather |

Weather not favorable |

4 |

| Information | Lack of central information about state and county-specific COVID-19 lawsa | 11 |

| Lack of credible information sources about state and county specific COVID-19 lawsa | ||

| Varying laws in different statesa | ||

| Don't know where to go or whom to contact if I feel sick during travel or during the tripa | ||

| Lack of preventive measures at destination or during travela | ||

| Local Community Perceptions | People being more hostile towards touristsa | 5 |

| Environment not being friendly-everyone thinks others are a threata | ||

| Local people not receptive to touristsa |

New items emerged due to COVID.

The numbers in this column do not equal 16 as each participant stated several constraints.

Similarly, participants also acknowledged that people have varied perceptions about COVID: some are conservative while others are liberal regarding following regulations and overall about COVID. Such varied perceptions and practices that people follow make it difficult to plan for and go on an outdoor trip.

However, it was interesting just the other day, I went climbing with my friend, and she was pretty COVID-wary and she was like “Are you guys using the toilet when you camp?” and I said Yes, and she said “We don't use toilet.” It's interesting people's different perspectives and different factors that might be inhibiting them in travel or camping.

Also everyone has their own perceptions of risk. Some think that this is overblown and some I have not seen over months. A big part of recreation trip is enjoying with family and friends. Some of the friends go to trips by themselves or family. Their comfort level I don't think that it would change for those people in the next year as well. My pool of people that I would go with has severely decreased.

Regarding intrapersonal constraints, participants were fearful and anxious to go on outdoor recreation trips, because of possibility of exposing themselves as well as being a carrier of COVID and transmitting it to others.

Other prevalent constraints that were raised during the discussion included the presence of crowds and the unavailability of facilities in and around the destination. Additionally, a lack of and unreliability of information about facilities around the destination plus COVID-19 related information and state/county specific regulation was cited frequently in the focus group sessions as being a barrier.

For sure, unclear messaging has not helped. It's like hard to figure out what is the right activity to do or like the health experts are telling us to do. Because there is no centralized message about and it's hard to trust too. Because the message of COVID has been very political like out of public health perspective and political. Do I follow what state of Utah says or what CDC says, or who do I listen to? Do I Listen to what NY times is saying? So that's definitely the hardest part.

For me, it's been confusion. I don't know what's open, like national parks might be open but trails might be closed. Are restaurants open? In California, things are open, closed don't know. Like to me, 20 minutes' beach would be open and you could go another beach that would be closed. No reason, because its different county. What are you allowed to do, or not?

Some participants also were wary of sanitization practices at destinations, unavailability of public restrooms, and a lack of health facilities in and around the destination. Other additional obstacles to outdoor recreation participation included time availability, cost of travel and lodging, and accessibility to destinations. Many focus group participants agreed that fear of traveling on flights plus inadequate sanitization measures and high occupancy of flights has constrained their outdoor participation.

And I am also thinking about the risk of danger like on these trips, which I would have not thought about previously. Like what's going to happen if I get hurt on a trail, what resources I am going to be stressing as a result of being hurt in the trail and could I be exposed to COVID because of going to deal with the healthcare system in this new place.

COVID-19 has impacted not only tourists' personal space, but also communities in and around the destination. A few focus group participants argued that the destination communities were not welcoming of tourists during the first few months of pandemic, which hindered their willingness to travel. Additionally, people were wary that they could not get the full outdoor experience, because everyone perceived others to be threat during the time, and socializing with other people would be extremely difficult.

People are more hostile, towards others. There's not like friendly smiley hikes. Everyone is a threat. That's been really interesting and weird shift.

Finally, constraints of time, cost and weather seemed to be universal, taking up a larger part in planning and decision making to make outdoor recreation trips.

4.3. Negotiation of constraints

From the content analysis of focus group discussions, 30 negotiation strategies were identified. In the current sample of focus group participants, 11 participants went on outdoor trips after the start of the pandemic (i.e., after March 2020), whereas 5 others did not take part. Hence, the following strategies reflect actions of successful outdoor participants as well as potential participants (who had not participated). During the thematic analysis, negotiation strategies were categorized in such a way that they mitigate a particular constraint. For instance, as crowding was one of the constraints, a way to negotiate the constraint is to try to go to destination on weekdays, when there is less crowding.

A predominant negotiation strategy, which all participants agreed upon, was to go to outdoor trips in locations with fewer crowds, avoid holidays, and try to go to wilderness areas. These strategies would allow them to conveniently maintain social distancing with people and get the full outdoor experience.

I think you can really take advantage going places. It's smart to travel with at least another person. Focus on destination that you know there would not be more people. It's not smart to go on 4thof July on popular areas, when so many people in US were outside. It's all about timing. If you go on weekdays, then you're going to encounter fewer people in state parks or popular areas or Bear Lake on weekends.

Specially, for now, you could go to places that are not visited. I think Basin is more favorable than Moab, right now. Or go to places where there are no people, and pack everything you need and food. Like a backpacking in wilderness, is more safe than going to Zion camping.

To mitigate interpersonal constraints, several approaches were outlined by focus group participants such as finding people with similar perceptions about COVID, people with good health, and to go on recreation trips with people who would properly follow social distancing and other sanitization measures.

But, it's kind of you have to suppose find people who have similar thoughts about the virus as you do. You can be very conservative or very liberal about the virus. Either way, you have to find people who are similar minded. Some people just want to be depressed and don't want to travel; others might feel great. It also benefits having people with similar standards of health.

Furthermore, most respondents also hinted at going to familiar tourist places nearby within driving distance by car, and trying to avoid flights and out-of-country travel, to mitigate the logistics, uncertainty, and mental burden that comes up with long-distance trips.

At least half of respondents argued that the decision to go on an outdoor overnight trip requires more research and extensive planning than it did before the COVID-19 outbreak. To add to the planning strategy, respondents also recommended to look for information about COVID-spread or state/county regulations, information about facilities in and around destinations, and information about health facilities around the destination. Most people felt that state or destination website information might not be reliable, so they had to dig deeper into online reviews and ask their peers and relatives about a particular destination, in order to get the accurate information.

I just think it takes a lot of time to plan in advance, however long it takes to. Some people like to travel in a whim, and kind of figure out when you get there. Others like to do advance planning. So I would think you cannot travel on a whim anymore or spur of the moment. You should have to do some kind of advance planning to make sure you can get to your destination or if they are allowing in.

I also look at COVID spread at the county, when I plan a trip. Because, initially around Feb/March, Moab had high cases and then around April/June it had low cases. That is the thing I look which I did not use to before. Definitely restaurants, see if there are good restaurants around. And if I am going for camping, look at the hiking trips there. I seek out somebody who has already been there and to seek a more personal view rather than reading on the sites.

Some respondents also mentioned various action plans to minimize their impacts on the local community such as bringing your own food (if possible) and minimizing the number of stops at the destination (see Table 5 for more strategies). Camping and backpacking trips were considered by the majority of respondents as safe and pleasurable activities during outdoor trips.

So, something I really think about, as living in a rural community here in Idaho, when I am outdoors and visiting other communities is that how can I minimize the impacts in rural community that I am going. So, think about masks in the gas station, we are not going to stop and do groceries, we make sure that we have everything with us, because that's what I would want people coming through my town to do.

Table 5.

Negotiation strategies.

| Themes | Negotiation Strategies | Number of references# |

|---|---|---|

| Interpersonal | Try to go with people you know | 10 |

| Try to find people with similar perceptions about COVID | ||

| Try to find people with similar health standards | ||

| Try to convince people to apply social distancing and safety measures during the recreation trip | ||

| Avoid Crowding/Timing | Try to go on weekdays, with less crowd | 16 |

| Try to go on destination that you know there would not be more people | ||

| Try to maintain social distancing with people, and travel with groups less than four | ||

| Try to avoid traveling on holidays like 4th of July or Thanksgiving | ||

| Try to wear masks | ||

| Try to interact with crowds less often | ||

| Try to go to wilderness areas | ||

| Planning and Preparing | Try to spend lot of time planning (cannot travel on a whim anymore) | 8 |

| Try to plan ahead of time | ||

| Try to notify companions and family members in advance | ||

| Try to book hotels and campground well in advance | ||

| Information Search | Collect information about facilities and activities at destination | 3 |

| Search for COVID-19 related county/state policies | ||

| Search for COVID-19 related spread | ||

| Seek information about health facilities/hospitals in and around the destination | ||

| Changing Leisure Aspirations | Try to go to tourist places that are accessible by car | 12 |

| Try to travel within state and within country | ||

| Try to go to familiar destinations | ||

| Try to avoid flying, until necessary | ||

| Food and logistics | Try to get your own food | 5 |

| Try to bring your own tent | ||

| Try to prepare checklist of things needed | ||

| Try to bring extra food | ||

| Try to minimize the number of stops during travel | ||

| Destination related | Try to go to destinations with limited occupancy | 3 |

| Try to find destinations with adequate health and hygiene measures adopted |

Finally, some of the participants also discussed about finding a destination which had adopted adequate sanitization measures and had limited occupancy, in order to have a safer and productive outdoor experience.

5. Discussion

First, from our focus group discussion, we were able to discern tourists' perceived motivations, constraints, and negotiation strategies. These findings provide a theoretical foundation of how a pandemic (COVID-19) affects tourists' psychology, interpersonal relations, and overall decision-making. In other words, the decision to go on an outdoor recreation trip entails a complex interaction of an individual's and their peers' perceptions and beliefs of COVID, plus an individual's perception of the effect on local communities. Although fear and anxiety of transmission and being a carrier of COVID was one of the issues hindering tourists' outdoor experiences, an inability to find suitable companions and a lack of socialization opportunities were more of a concern. Crowdedness as a constraining factor offers support to previous research (e.g., Wang & Ackerman, 2019) which suggests that negative perceptions of crowding are amplified during events of pathogen threat.

Furthermore, the sense of “guilt” while going on outdoor recreation trips was evident when some respondents outlined the effects on local tourism communities; i.e. people's empathy towards local communities (social factors) have a bigger role to play in the current pandemic condition than otherwise (Godbey et al., 2010; Crawford & Stodolska, 2008). However, findings of our study also imply that constraints such as time and cost, closure of facilities, weather, and a lack of information are still persistent and are dominant factors in people's decision-making processes as well as during participation in outdoor recreation trips. An incentive for the tourism industry is that individuals are still finding a number of ways to negotiate through their perceived constraints to participate in outdoor recreation (11 of the 16 focus group respondents took an outdoor recreation trip since the start of the COVID outbreak in March 2020). Our findings offer support to the social cognitive theory (Maddux, 1993), which is suggestive of the idea that people either alter their situational and environmental conditions, instead of passively accepting unfavorable states. As one participant answered when asked about inconveniences in outdoor recreation participation:

I would say there are more inconveniences than obstacles. I think everything is manageable. I don't have a fear being outside and catching COVID.

In the absence of vaccines for COVID, and when transmission through physical contact is possible, people are modifying outdoor recreation behaviors in such a way that they can get an outdoor experience as well as remain safe while doing so. Modification in leisure-related behavioral strategies include avoiding crowds, changing leisure aspirations, and finding similarly-minded people. This is in line with previous research on disasters, and supports the idea of tourists' xenophobia and ethnocentrism (Faulkner et al., 2004; Kock, Josiassen, Assaf, Karpen, & Farrelly, 2019). Alternatively, rearrangement of work schedules, managing finances, and a preference for family trips fall into non-leisure behavioral strategies. Specifically, collection of large amounts of information, and from various information sources, plus extensive planning beforehand are some of the strategies tourists apply in order to reduce psychological discomfort and to enhance confidence when going on outdoor recreation trips.

In the study context, we find that people have desires to substitute outdoor overnight (and long-distance) trips with day-trips and trips to familiar and nearby outdoor locations. This finding complements the theory of substitutability proposed by Iso-Ahola (1986), and research by Hall and Shelby (2000) who suggested that individuals can substitute place (nearby instead of long-distance trips) and timing (like going in weekdays instead of weekdays, to avoid crowds) when performing an activity (outdoor recreation trips) if the experience is likely to be accomplished elsewhere with more convenience and safety.

5.1. Managerial implications

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to negatively impact the tourism sector. In the absence of vaccines, the tourism sector must continue to evolve and find ways to attract tourists through extensive preparation and novel strategies. By gaining an understanding of tourists' perceived constraints and their negotiation strategies, this study paves the way for some actions that can attenuate COVID-19 impacts and simultaneously attract tourists.

5.1.1. Centralized information

Leisure literature contains a plethora of research examining the influence of information availability, information search behavior, and destination image on tourists' behaviors (e.g., Gursoy & McCleary, 2004; Baloglu, 2000). Visitation intention has been found to be influenced by destination image (perceptual/cognitive reflection), the amount of information, and the type of information source (Baloglu, 2000). As findings of our study underline the importance of information search during planning and decision-making processes, it is crucial for destinations to provide accurate, reliable, and timely information to tourists. Online sources are the most used information sources currently; so, we propose a website template for destinations, incorporating our findings; see Fig. 2 .

Fig. 2.

Proposed website template for destination.

Adding the date of publication reduces doubts about the unreliability and timeliness of information. Information about COVID-related spread and policies/regulations helps tourists to prepare themselves accordingly for travel and follow regulations during visitation. Similarly, information about facilities and activities around the destination, including closures of facilities and food/lodging options, will certainly aid planning and decision-making. As focus group participants advocated for personal recommendations, recent photos of the destination and recent user reviews will reinstate tourists' trust in the information and encourage visitation.

5.1.2. Advertising strategies

Primarily, our study sheds light on tourists' preferences for outdoor trips with family or people you know/live with. Hence, destination marketers and managers should focus on planning for and marketing of family tour packages, with appropriate physical distancing measures. For example, a 2-/3-day family tour with visitation around the destination, and adequate options for food and lodging, may be popular.

Furthermore, tourists were more inclined to participate in backpacking and camping trips, and to wilderness areas, in order to avoid crowds and increase the convenience of maintaining physical distancing. This certainly provides incentives for tourism marketers to promote longer hiking trails, campsites, and wilderness areas through multi-channel strategies such as short promotional videos, brochures, or direct mailing options. The effect of crowds could be even more pronounced in destinations with confined spaces (such as cities or beaches), which calls for proper implementation of social distancing and other COVID-19 regulations to increase tourists' confidence and safety.

Additionally, tourists were found to be concerned about safety and hygiene measures at the destination. It is imperative for destination managers and marketers to promote the operational practices applied at the destination—such as the placement of sanitizers, signage around the destination, and availability and state of public restrooms—to remove such concerns. As online information search behavior is trending in the current world, tourism marketers can look to target avid travelers, e.g., young people with a low risk of COVID, through targeted social media ads (Twitter, Facebook, etc.). Additionally, advertising strategies could focus on a unique segment of population: “crisis-resistant” tourists, who continue to travel in such events (Hajibaba et al., 2015).

5.1.3. Operational practices at destinations

COVID-related operational practices at destinations might affect how tourists evaluate destination satisfaction or overall satisfaction with their outdoor recreation trips, which impacts their re-visitation or recommendation intentions (Um et al., 2006a; Abdullah & Lui, 2018). Hence, destination managers should look to apply adequate provisions for allowing a full outdoor experience. Tourists' perceived constraints and negotiation strategies mentioned above provide recommendations on types of practices that can be applied at destinations (COVID-19 Perceptions of Risk Travel Survey, 2020), such as:

-

•

Signage placed to encourage people staying six feet apart from one another in crowded areas

-

•

Efforts to enforce social distancing and use masks/face coverings

-

•

Staff efforts to regularly wipe down surfaces

-

•

Advising visitors with flu-like symptoms to stay home

-

•

Provision of station touchless hand sanitizers

-

•

Providing employees with personal protective equipment (e.g. gloves, masks)

-

•

Well-ventilated and clean restrooms

-

•

Providing limited occupancy on crowded areas

6. Conclusion, limitations, and future research

Although a rising amount of empirical research on the impacts of COVID-19 on outdoor recreation demand can be observed recently, virtually no studies have examined tourists' perceptions regarding outdoor recreation in relation to the pandemic. We have attempted to fill this research gap in this study. First, tourists are found to be constrained in their outdoor recreation participation by the COVID threat as well as some broader psycho-social interactions and uncertainties bought about by the combination of COVID and government-issued restrictions and regulations. Specifically, looking at types of constraints and negotiation strategies from this focus group study, several commonalities and some differences with past disaster research could be detected. The carryover of perceptions post-pandemic will certainly affect tourists' behaviors in terms of destination choice, companionship preferences, and leisure activity preferences.

The implications of this study to existing literature are threefold. This study is one of the first efforts to offer deeper insights into tourists' decision-making processes during COVID-19 (initial phase) through a qualitative study. In doing so, we explored and categorized perceptions of constraints, motivations, and negotiation strategies in the COVID-affected tourism system. Second, we provide a number of tourism demand recovery strategies through managerial implications: emphasizing the provision of centralized information, advertising strategies to attract demand, and COVID-19 management at the destination. The third implication of this research is academic: implying that the dimensions of constraints, negotiations, and motivations (especially the COVID-19 related ones) found in this study could be used in future tourism research for developing new theoretical models or strengthening the past models (e.g., Kock et al., 2020).

There are certain limitations to this study, specifically the sample size and distribution. Although saturation of key ideas was achieved with a low sample size (which is found in many other focus group studies as well, see Hennink et al., 2019), future research could look to capture such nuances utilizing qualitative approaches in a larger, broader, and representative size. Specifically, perceptions of high-risk populations (older adults) and lower-income communities could differ, due to the nature of lifestyle constraints that they encounter in their daily lives. For example, lower-income families are financially constrained to greater degree and they may be more liable to forego long-distance trips in favor of trips to local destinations. Additionally, research to understand perceptions of local communities might be vital in preparing and planning for a swift recovery in tourism participation.

Another limitation of our study is the lack of cross-national generalizability. It is pertinent to acknowledge that populations across different cultures and countries perceive risks differently (Fuchs & Reichel, 2006; Kozak et al., 2007; Reisinger & Mavondo, 2006). For example, tourists from Singapore, China, and Malaysia were found to perceive higher risks (than Westerners) during events of natural disaster, pathogen threat, and terrorist attacks (Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005; Kozak et al., 2007). Similarly, US, Australian, and Hong Kong tourists perceived higher levels of travel risks than Greek and Canadian tourists (Reisinger & Mavondo, 2006). While we believe that many items of constraints, negotiations, and motivations found in our study (such as the use of sanitizers, or adequate preparation before making a trip) will be common across tourists in any area, there might be differences in tourists' perceptions due to diverse cultural backgrounds (Reisinger & Mavondo, 2006) and government responses to COVID-19. Hence, it generates a promising area of future research to compare the nature of constraints, motivations, and negotiations across different geographies.

Constraints are activity-specific: i.e. different constraints are encountered in the pursuit of different leisure activities. While we consider a general definition of outdoor recreation in our study (as any trip undertaken for any recreation purpose), future research could benefit from the exploration of these concepts for specific recreational activities such as skiing, rock climbing, beaches, mountain destinations, etc. Furthermore, the findings of this study could be used to conduct a larger quantitative survey to illuminate and extend the leisure constraint-negotiation model (such as Hubbard & Mannell, 2001), unique to this pandemic context. The interrelationships between motivations, constraints, and negotiations on tourists' intentions to participate in outdoor recreation require further empirical inquiry, and such studies could help to provide recommendations for tourism recovery in the post-pandemic context.

Finally, the data collected here represent perceptions of tourists at one point in time. As people learn more about pathogen threats (such as COVID-19), perceptions of risk could change, and tourists could prepare adequately for their trips, which would affect the variables in the study. The availability of vaccines would help negotiate constraints related to fear of COVID-19 transmission and ethical dilemmas during traveling to enhance outdoor recreation experiences. Hence, a longitudinal study to understand tourists' perceptions through different time periods such as the first three months of a novel pathogen threat, the stability period (when there is adequate information), the period after the introduction of vaccines, and the period after the adequate distribution of vaccines, might be more relevant. This would be helpful for destination managers to tailor different action plans to different phases to attract tourists if there is another pathogen threat issue in the future.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Prasanna Humagain: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Data Collection, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Patrick A. Singleton: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- Abdullah S.I.N.W., Lui E. Satisfaction drivers and revisit intention of international tourists in Malayisia. Journal of Tourism, Hospitality and Environment Management. 2018;3(9):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Bae S.Y., Chang P.-J. The effect of coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) risk perception on behavioural intention towards ‘untact’ tourism in South Korea during the first wave of the pandemic (March 2020) Current Issues in Tourism. 2021;24(7):1017–1035. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2020.1798895. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baloglu S. A path analytic model of visitation intention involving information sources, socio-psychological motivations, and destination image. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing. 2000;8(3):81–90. doi: 10.1300/J073v08n03_05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brug J., Aro A.R., Oenema A., De Zwart O., Richardus J.H., Bishop G.D. SARS risk perception, knowledge, precautions, and information sources, The Netherlands. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2004;10(8):1486. doi: 10.3201/eid1008.040283. https://10.3201/eid1008.040283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Economic Analysis Travel and tourism. 2021. https://www.bea.gov/data/special-topics/travel-and-tourism

- Cahyanto I., Wiblishauser M., Pennington-Gray L., Schroeder A. The dynamics of travel avoidance: The case of Ebola in the. U.S. Tourism Management Perspectives. 2016;20:195–203. doi: 10.1016/j.tmp.2016.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cashdan E., Steele M. Pathogen prevalence, group bias, and collectivism in the standard cross-cultural sample. Human Nature. 2013;24(1):59–75. doi: 10.1007/s12110-012-9159-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H., Deng F. How to Influence Rural Tourism Intention by Risk Knowledge during COVID-19 Containment in China: Mediating Role of Risk Perception and Attitude. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(10):3514. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17103514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19 perceptions of risk travel survey. 2020, October. https://tcmi.hhp.ufl.edu/covid-19-travel-survey Retrieved from.

- Crawford D.W., Godbey G. Reconceptualizing barriers to family leisure. Leisure Sciences. 1987;9(2):119–127. doi: 10.1080/01490408709512151. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford D.W., Jackson E.L., Godbey G. A hierarchical model of leisure constraints. Leisure Sciences. 1991;13(4):309–320. doi: 10.1080/01490409109513147. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford J.L., Stodolska M. Constraints experienced by elite athletes with disabilities in Kenya, with implications for the development of a new hierarchical model of constraints at the societal level. Journal of Leisure Research. 2008;40(1):128–155. [Google Scholar]

- Das S.S., Tiwari A.K. Understanding international and domestic travel intention of Indian travellers during COVID-19 using a Bayesian approach. Tourism Recreation Research. 2021;46(2):228–244. [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner J., Schaller M., Park J.H., Duncan L.A. Evolved disease-avoidance mechanisms and contemporary xenophobic attitudes. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations. 2004;7(4):333–353. doi: 10.1177/1368430204046142. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fendt L.S., Wilson E. ‘I just push through the barriers because I live for surfing’: How women negotiate their constraints to surf tourism. Annals of Leisure Research. 2012;15(1):4–18. doi: 10.1080/11745398.2012.670960. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd M.F., Gibson H., Pennington-Gray L., Thapa B. The effect of risk perceptions on intentions to travel in the aftermath of september 11, 2001. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing. 2004;15(2–3):19–38. doi: 10.1300/J073v15n02_02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs G., Reichel A. Tourist destination risk perception: The case of Israel. Journal of Hospitality & Leisure Marketing. 2006;14(2):83–108. doi: 10.1300/J150v14n02_06. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson H., Yiannakis A. Tourist roles: Needs and the lifecourse. Annals of Tourism Research. 2002;29(2):358–383. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(01)00037-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Godbey G., Crawford D.W., Shen X.S. Assessing hierarchical leisure constraints theory after two decades. Journal of Leisure Research. 2010;42(1):111–134. doi: 10.1080/00222216.2010.11950197. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gössling S., Scott D., Hall C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 2020:1–20. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2020.1758708. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gursoy D., McCleary K.W. Travelers' prior knowledge and its impact on their information search behavior. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research. 2004;28(1):66–94. doi: 10.1177/1096348003261218. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hajibaba H., Gretzel U., Leisch F., Dolnicar S. Crisis-resistant tourists. Annals of Tourism Research. 2015;53:46–60. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2015.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hall T., Shelby B. Temporal and spatial displacement: Evidence from A high-use reservoir and alternate sites. Journal of Leisure Research. 2000;32(4):435–456. doi: 10.1080/00222216.2000.11949926. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han J.Y. Department of Hospitality and Tourism Management, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University; 2005. The relationships of perceived risk to personal factors, knowledge of destination, and travel purchase decisions in international leisure travel. PhD dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins B.A., Joanne Peng C. Leisure constraints: A replication and extension of construct development. Leisure Sciences. 1999;21(3):179–192. doi: 10.1080/014904099273066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hennink M.M., Kaiser B.N., Weber M.B. What influences saturation? Estimating sample sizes in focus group research. Qualitative Health Research. 2019;29(10):1483–1496. doi: 10.1177/1049732318821692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede G., Hofstede G. 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill; New York: 2005. Cultures and Organizations; Software of the Mind. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh H.-F., Shannon S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J.H., Min J.C. Earthquake devastation and recovery in tourism: The Taiwan case. Tourism Management. 2002;23(2):145–154. doi: 10.1016/S0261-5177(01)00051-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard J., Mannell R.C. Testing competing models of the leisure constraint negotiation process in a corporate employee recreation setting. Leisure Sciences. 2001;23(3):145–163. doi: 10.1080/014904001316896846. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iso‐Ahola S.E. A theory of substitutability of leisure behavior. Leisure Sciences. 1986;8(4):367–389. doi: 10.1080/01490408609513081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson E.L., Crawford D.W., Godbey G. Negotiation of leisure constraints. Leisure Sciences. 1993;15(1):1–11. doi: 10.1080/01490409309513182. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiachen C. Pay attention to the influences of SARS on the psychological changes of tourists. China Tourism News. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- Khalid U., Okafor L.E., Burzynska K. Does the size of the tourism sector influence the economic policy response to the COVID-19 pandemic? Current Issues in Tourism. 2021:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Koca C., Henderson K.A., Asci F.H., Bulgu N. Constraints to leisure-time physical activity and negotiation strategies in Turkish women. Journal of Leisure Research. 2009;41(2):225–251. [Google Scholar]

- Kock F., Josiassen A., Assaf A.G. The xenophobic tourist. Annals of Tourism Research. 2019;74:155–166. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2018.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kock F., Josiassen A., Assaf A.G., Karpen I., Farrelly F. Tourism ethnocentrism and its effects on tourist and resident behavior. Journal of Travel Research. 2019;58(3):427–439. doi: 10.1177/0047287518755504. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kock F., Nørfelt A., Josiassen A., Assaf A.G., Tsionas M.G. Understanding the COVID-19 tourist psyche: The evolutionary tourism paradigm. Annals of tourism research. 2020;85:103053. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2020.103053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kono S. Constraining, negotiating, and facilitating leisure after disaster: A case of the great East Japan earthquake and tsunami. International Journal of the Sociology of Leisure. 2018;1(2):171–195. doi: 10.1007/s41978-018-0011-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kozak M., Crotts J.C., Law R. The impact of the perception of risk on international travellers. International Journal of Tourism Research. 2007;9(4):233–242. doi: 10.1002/jtr.607. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F. National Report; 2003. Analysis and Solutions of the impact of SARS on China's tourism industry, special Issues on SARS 11. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu S.O., Oh C.-O. Recreationists' constraints negotiation process for continual leisure engagement. Leisure Sciences. 2014;36(5):479–497. doi: 10.1080/01490400.2014.920702. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maddux J.E. Social cognitive models of health and exercise behavior: An introduction and review of conceptual issues. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology. 1993;5(2):116–140. doi: 10.1080/10413209308411310. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manfredo M.J., Driver B.L., Tarrant M.A. Measuring leisure motivation: A Meta-analysis of the recreation experience preference scales. Journal of Leisure Research. 1996;28(3):188–213. doi: 10.1080/00222216.1996.11949770. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalf E.C., Graefe A.R., Trauntvein N.E., Burns R.C. Understanding hunting constraints and negotiation strategies: A typology of female hunters. Human Dimensions of Wildlife. 2015;20(1):30–46. doi: 10.1080/10871209.2015.957366. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Milman A., Pizam A. The role of awareness and familiarity with a destination: The central Florida case. Journal of Travel Research. 1995;33(3):21–27. doi: 10.1177/004728759503300304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neuburger L., Egger R. Travel risk perception and travel behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic 2020: A case study of the DACH region. Current Issues in Tourism. 2021;24(7):1003–1016. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2020.1803807. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neuman W.L. 6th ed. 2006. Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Boston, MA: Pearson Allyn and Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Nyaupane G.P., Andereck K.L. Understanding travel constraints: Application and extension of a leisure constraints model. Journal of Travel Research. 2008;46(4):433–439. doi: 10.1177/0047287507308325. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nyaupane G.P., Morais D.B., Graefe A.R. Nature tourism constraints. Annals of Tourism Research. 2004;31(3):540–555. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2004.01.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Page S., Yeoman I., Munro C., Connell J., Walker L. A case study of best practice—visit Scotland's prepared response to an influenza pandemic. Tourism Management. 2006;27(3):361–393. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2006.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park K., Reisinger Y. Differences in the perceived influence of natural disasters and travel risk on international travel. Tourism Geographies. 2010;12(1):1–24. doi: 10.1080/14616680903493621. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peters M., Pikkemaat B. Crisis management in Alpine winter sports resorts—the 1999 avalanche disaster in Tyrol. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing. 2006;19(2–3):9–20. doi: 10.1300/J073v19n02_02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reisinger Y., Mavondo F. Cultural differences in travel risk perception. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing. 2006;20(1):13–31. doi: 10.1300/J073v20n01_02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sönmez S.F., Graefe A.R. Influence of terrorism risk on foreign tourism decisions. Annals of Tourism Research. 1998;25(1):112–144. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Cañizares S.M., Cabeza-Ramírez L.J., Muñoz-Fernández G., Fuentes-García F.J. Impact of the perceived risk from Covid-19 on intention to travel. Current Issues in Tourism. 2021;24(7):970–984. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2020.1829571. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seong B.H., Hong C.Y. Does Risk Awareness of COVID-19 Affect Visits to National Parks? Analyzing the Tourist Decision-Making Process Using the Theory of Planned Behavior. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(10):5081. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18105081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son J.S., Mowen A.J., Kerstetter D.L. Testing alternative leisure constraint negotiation models: An extension of Hubbard and Mannell's study. Leisure Sciences. 2008;30(3):198–216. doi: 10.1080/01490400802017308. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tourism Economics Weekly Coronavirus impact on travel expenditures in the U.S. 2021. https://www.ustravel.org/sites/default/files/media_root/document/TE_Coronavirus_WeeklyImpacts_01.22.21.pdf Retrieved from.

- Um S., Chon K., Ro Y. Antecedents of revisit intention. Annals of Tourism Research. 2006;33(4):1141–1158. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2006.06.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang I.M., Ackerman J.M. The infectiousness of crowds: Crowding experiences are amplified by pathogen threats. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2019;45(1):120–132. doi: 10.1177/0146167218780735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber E.U., Hsee C. Cross-cultural differences in risk perception, but cross-cultural similarities in attitudes towards perceived risk. Management Science. 1998;44(9):1205–1217. [Google Scholar]

- Wen Z., Huimin G., Kavanaugh R.R. The impacts of SARS on the consumer behaviour of Chinese domestic tourists. Current Issues in Tourism. 2005;8(1):22–38. doi: 10.1080/13683500508668203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- White D.D. A structural model of leisure constraints negotiation in outdoor recreation. Leisure Sciences. 2008;30(4):342–359. doi: 10.1080/01490400802165131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilder-Smith A., Freedman D.O. Isolation, quarantine, social distancing and community containment: pivotal role for old-style public health measures in the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak. Journal of travel medicine. 2020;27(2) doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W., Youn H.-J., Lee C.-K. Role of Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions for COVID-19 in Cruise Tourists’ Decision-Making Process: An Extended Model of Goal-Directed Behavior. Sustainability. 2021;13(10):5552. doi: 10.3390/su13105552. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng B., Carter R.W., De Lacy T. Short-term perturbations and tourism effects: The case of SARS in China. Current Issues in Tourism. 2005;8(4):306–322. doi: 10.1080/13683500508668220. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zenker S., Kock F. The coronavirus pandemic – a critical discussion of a tourism research agenda. Tourism Management. 2020;4 doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, R. T., Park, J., Li, S., & Song, H. (2020). Social costs of tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic. Annals of Tourism Research, 84, 102994.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]